ABSTRACT

Drawing on a qualitative case study of a New Zealand primary school, this paper provides an audit of commercialisation and outsourcing across the curriculum. Interviews were also conducted with teachers of specific Key Learning Areas (KLAs) to better understand their decision-making process in bringing externally provided products and services into their classrooms. Findings demonstrate that the procurement of external products and services is common across the curriculum. Teacher decision-making to commercialise and outsource curriculum is based on a multiplicity of personal, distributed and situational factors. We suggest that teachers are aware of and seeking to balance autonomy and responsibility in their decision-making, but there is room to improve how teachers understand and engage with ethical considerations of commercial procurement, supplier quality and systemic issues of equity and access to these services by all schools and teachers.

Introduction

This paper is about commercialisation and outsourcing in schooling, and the decision-making process teachers engage in to bring externally provided products and services into their classrooms. We present an audit of one New Zealand (NZ) primary school’s engagement in commercialisation and outsourcing across all eight ‘Key Learning Areas’ (KLAs) of the curriculum. To date much research has focused on outsourcing in single curriculum areas, such as HPE (see Sperka & Enright, Citation2018), or generic concerns about how commercialisation changes teaching and learning practices, particularly through the advancements of educational technology (Selwyn et al., Citation2020) . We were unable to find any studies that have attempted to map external provision across the entirety of a school’s curriculum. Our paper’s empirical contribution starts this work, and we argue that while external provision is common across the curriculum, teachers of different KLAs tend to have different rationales—including specialised needs within their KLA—to justify their procurement of externally provided resources.

In what follows, we first detail the rise of commercialisation and outsourcing across the NZ curriculum, arguing that the decentralisation of schooling has, in part, increased opportunities for private ‘solutions’ to curriculum ‘problems’. Second, we carefully define commercialisation and outsourcing and how we are using these terms in this paper. This is important because although these terms are often used synonymously, they explain distinct processes of external provision within public schooling. Third, we introduce ideas around teacher decision-making, and how externally provided resources could be conceived as useful tools for teaching and learning. We then present our curriculum audit and interview data from different KLA teachers to better understand their decision-making processes. We argue that despite the dangers that might accompany externally provided products and services, the teachers within this school perceive them as necessary pedagogical tools. They cite a range of pragmatic issues, as well as the need to ‘save’ time and enhance student outcomes as part of their justifications. Finally, we argue that the participants in this study perceive externally provided products and services as necessary tools for teaching and learning and suggest that further guidelines supporting ethical procurement would help to better inform teacher decision-making about commercialisation and outsourcing. This is necessary to ensure that external resources remain as tools for teachers, and never an avenue to undermine or replace teachers.

Privatisation, commercialisation and outsourcing in New Zealand schooling

In the 1980s, NZ embarked on an education reform agenda, marked by ‘Tomorrow’s Schools’ legislation. Essentially, this policy was couched in a range of neoliberal tenets, including market-based notions of efficiency, effectiveness, accountability, and competition (Powell, Citation2019). As with most Anglophone school systems around the world at this time, school decentralisation and an increase in autonomy for self-management and local decision-making was seen as the most effective way to drive improved system outcomes (Codd, Citation2005; Thrupp et al., Citation2021). While schools were still fully supported with government funding—through the Ministry of Education (MoE) Operational Grant—schools had more control over how they spent their budgets on day-to-day operations. Over time, this enabled opportunities for the growth of external providers (EPs). For instance, Thrupp et al. (Citation2021, p. 34) observed that individual schools make decisions to enrich curriculum, particularly by ‘bringing in private actors for teaching health and physical education, art, dance, drama and the like’. Similarly, other researchers have looked at the rise of commercial student management systems in NZ schools through the likes of ETap, Musac and Schoology (Cowan et al., Citation2022) and the delivery of commercial professional development of teachers through ‘Core Education’ (O’Neill, Citation2017). The need for these services, rather obviously, increases the number of EPs offering these services, and importantly, the state simultaneously reduces their capacity to offer these services—by restructuring and downsizing. Thus, the state enables and promotes quasi-marketisation and the rise of externally provided services for schools.

Privatisation, and in particular, Ball and Youdell’s (Citation2008) terms of exogenous and endogenous privatisation are often used to explain private sector interests in schooling. In this paper, we are taking care to more carefully define what is happening in schools by employing the terms ‘commercialisation’ and ‘outsourcing’. Commercialisation is the creation, marketing and sale of education goods and services to schools by EPs and/or the sale of commercial goods by schools to the public (Holloway & Keddie, Citation2019). This includes, for instance, schools buying commercial SMS programmes or professional development services listed above, or schools hiring out their facilities to the public for fundraising purposes (Yoon et al., Citation2020). Outsourcing, on the other hand, ‘is a practice that involves establishing a relationship with an external entity with the intention for that entity to either extend, substitute, or replace internal capabilities’ (Enright et al., Citation2020, p. 275). This speaks to the practices of bringing EPs in to deliver KLA curriculum, particularly in Health and Physical Education (HPE), art, dance and drama. Both commercialisation and outsourcing constitute external provision; however, our argument is that these might produce different effects within the delivery of curriculum, e.g. a commercial resource might be used by the classroom teacher, whereas an outsourced programme might be delivered by someone external to the school—often with no, or limited, educational training.

Concerns have been raised about how commercial products might undermine local curriculum processes, by simply being based on generic global material most often constructed for the U.S. or UK education systems (Verger et al., Citation2016). Similarly, outsourcing has been critiqued as displacing teacher expertise—particularly in matters of pedagogy, assessment and student behaviour—for some sort of specialist expertise. A common concern for education is that products and services offered by EPs have become normalised within the daily practice of schools and are largely employed uncritically by teachers (Powell, Citation2015).

Teacher decision making

A considerable amount of research has sought to understand the constraints within which teachers work and how they make decisions. These include macro analyses of the changing conditions of teachers’ work, and how they are often blamed for failing to adapt curriculum in innovative ways or prepare students for the changing needs of industry (Mockler, Citation2020). Others focus on the complex interplay of institutional factors that limit their ability to act, such as, class size, student composition, classroom ecology, overcrowded curriculum, assessment demands, accountability structures, collegial interaction, pupil expectations, parental demands, and so on (Woods et al., Citation2019). Alongside the complexity of teachers’ work, the importance of teachers as human beings, as social actors with their own problems and perspectives cannot not be overlooked. Much research has examined how teacher background, motivation, experience (often focusing on the first phase or five-years of the teaching career) and career progression strategies influence teacher professionalism (Haw et al., Citation2023). There are many rich interpersonal accounts of decision-making and how these interact with systems of power, culture and ideology. For instance, some research has observed the ways in which teachers struggle to uphold their personal ideals and worldviews within marketised education systems, where often they struggle just to ‘survive’ rather than ideologically ‘thrive’ (see, for instance, Hogan et al., Citation2022). Even 30 years ago, Ball and Goodson (Citation1985) noted the bureaucratisation and proletarianisation of teaching—the form filling, the record keeping, the dehumanising of pupil interaction—all worked to make teacher decision-making increasingly rational and more impersonal.

Many researchers have referred to this shift in decision-making as an effect of the rise of managerialism in schools. Codd (Citation2005), discussing the NZ context, argued that ‘neoliberal policies have eroded fundamental democratic values of collective responsibility, cooperation, social justice and trust … to a form of managerial control which aims to render the work of teachers visible through reporting systems and managerial procedures’ (p. 204). Lundahl et al. (Citation2013) investigate how these managerial aspects—specifically documentation and evaluation—impact on teachers’ perceived autonomy and daily work. They argue that teachers’ have shifted from autonomous professionals to service-oriented workers in a quasi-business environment. In this system, marketing and benchmarking consumes time and energy at the expense of the core activities of teaching—increasing workload and intensifying work. Indeed, there are various examples in the literature highlighting the changing priority of teachers’ work tasks, where applying professional judgement becomes less important than satisfying and retaining clientele. The point here, as Zembylas argues, is that there is a ‘dichotomy of the self’, between a ‘teacher’ and ‘themself’. Indeed, some see teacher identity—their sense of self, and their ability to make decisions—as always in tension with, or at least existing within, the context of a particular institution with its own ideological structure and micropolitics (Buchanan, Citation2015).

In this paper, we understand teacher decision-making as complex. Specifically, we understand the factors influencing decision-making as situational (responding to specific contexts and ‘risks’ within each (KLA) (Williams & Macdonald, Citation2015)), distributed (influenced by broader practices within the school, particularly budget constraints (Hollands et al., Citation2019)), and personal (teacher’s own beliefs, attitudes, experience, and intuition (Vanlommel et al., Citation2017)). Vanlommel et al. (Citation2017), for instance, argue that teachers rely more on ‘intuition’ than data in decision-making processes. Similarly, Hedges (Citation2012) observes that teachers’ ‘informal knowledge’, often gained from life experience, is almost always prioritised by them over any theories they might know about ‘useful’ pedagogical decision-making guidelines or frameworks. This combination of teacher intuition and pragmatism (i.e. the limitations of context and budget) is always dealt with agentically (Biesta et al., Citation2015). Importantly, Biesta et al. (Citation2015) argue that teachers are always having to make decisions about their practice in ways that seek to balance ‘autonomy’ and ‘responsibility’. Thus, while they might have the autonomy—as individuals and professionals—to make decisions about their pedagogical practices, this comes with the responsibility of making morally and ethically sound choices while considering the wellbeing and educational development of their students.

Method

This paper emerges out of a broader case study of Mornington School (pseudonym), a large primary school in a metropolitan area in the South Island of NZ. The school has a diverse student population and sits in a community of average socioeconomic status. Data for this paper were collected through informal conversation, school website auditing, financial records, and semi-structured interviews with five teachers and one school leader. All five teachers had leadership responsibilities for a particular age group within the school, and therefore, had oversight over the decisions their group made to commercialise or outsource aspects of curriculum, particularly through budget spending. Semi-structured interviews included questions about KLA budgets, how these were spent on externally provided curriculum materials, programmes and/or services, and the justifications or decision-making processes that teachers had in bringing these into their classrooms. Participant perspectives allowed us to generate insight into the particularity and complexity (Stake, Citation2003) of their decision-making. It was not our intention in this paper to suggest that external provision of curriculum is good or bad. Instead, we sought to better understand what these teachers perceived as the most important factors influencing their ‘informed and ethical’ decision-making in an era of ongoing educational marketisation.

Initial analysis of interview data was conducted by the lead author using an inductive approach to examine the broader dataset looking for, and coding, instances of decision-making related to commercialisation and/or outsourcing of curriculum. This generated a set of 15 codes (e.g. evidence-based, cost-related, time saving, innovation). The research team then drew on their collective knowledge and understanding of literature on teacher decision-making to organise these codes into three overlapping but interdependent themes; situated, distributed and personal types of decision-making. In doing this, the research team generated themes via Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2019, p. 39) reflexive approach to analysis, where ‘reflexive approaches involve later theme development, with themes developed from codes, and conceputalised as patterns of shared meaning underpinned by a central organising concept’ (i.e. teacher decision-making). This brings together inductive (data-driven) and deductive (theory-driven) orientations to producing meaning. In the reporting of results, teachers are referred to as T1–5, and the senior leader is referred to as SL.

Audit of commercialisation and outsourcing across the curriculum

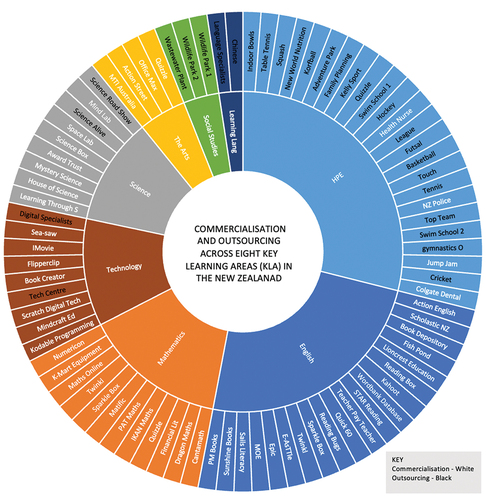

Our audit of commercial products and services across the KLAs of Mornington allowed us to visualise what a ‘typical’ school’s engagement with the private sector might now look like (see ).

HPE, the Arts, Learning Languages and the Social Sciences appear to be more outsourced than other KLAs. This finding aligns with other research that identifies the prevalence of outsourcing in what has been labelled ‘non-core’ subjects (Thrupp et al., Citation2021). In HPE, for instance, there is clear evidence of many specialist providers coming in to deliver programmes (such as, indoor bowls, squash, table tennis, korfball, hockey, league, futsal, touch and tennis). There is also evidence of outsourcing in science at Mornington, with references made to Science Alive and Science Roadshow; both commercial programmes that provide science ‘experts’ to deliver specialised science programmes within schools. This aligns with research that questions the confidence classroom generalists have in teaching particular curriculum areas and/or the access teachers have to specialised resources and facilities (Russo et al., Citation2022).

Similarly, Mornington displays the increasingly common practice of taking students ‘off campus’ to access specialised facilities and/or instruction for activities perceived to be of higher risk (see, Olstad et al., Citation2021). For example, Mornington students regularly travel to a local swimming pool and gymnastics centre for HPE lessons and also attend a Technology Centre at the local Intermediate School weekly to access specialist technology and resources (i.e. design, visual communication and food technology). These regular activities are complemented by a range of excursions. In the Social Sciences KLA, for example, annual trips are conducted to Wildlife Parks and the Sewage Treatment Plant. School camps and student ‘team building’ activities are also hosted at commercial venues.

Through the audit, we can also identify the evolving nature of curriculum delivery taking place inside school boundaries. This is not a new aspect of school commercialisation. Even in the 1990s, researchers were identifying the proliferation of the commercial textbook (Kenway et al., Citation1993). As mentioned above, Burch (Citation2009) similarly investigated the rise of commercial testing services alongside the rise of standardised testing. At Mornington, we see the use of progressive achievement tests (i.e. ACER’s Progressive Achievement Tests and IKAN Maths) as well as user-created quizzes, like Quizzle. However, now, the increasing digitalisation of education has given rise to an incredibly diverse portfolio of resources across the curriculum (Ideland et al., Citation2020; Jòber, Citation2024). We see how Mornington, particularly in the KLAs of English, Maths, Technology and Science, is buying a diverse range of commercial curriculum resources. In English, for instance, levelled and decodable readers are recognised as essential resources in helping students learn to read. In maths and technology, there is more of a trend towards accessing online learning programmes (such as, Matific, Dragon Maths and Minecraft Ed) and specialised software packages (such as, iMovie, Bookcreator and Flipperclip). Maths and Science also buy physical ‘resource kits’, including those provided by Numicon, Learning through Science, House of Science, Mystery Science and Science Box. These are all marketed as providing all the equipment necessary to engage in ‘hands on’ learning. As Hensley and Huddle (Citation2021) have argued, access to curricular resources is both beneficial to teachers’ retention (lessening stress of curriculum planning) and supportive of teachers’ ability to make effective pedagogical decisions.

Beyond these ready-made packages, we also see how teachers search for one-off online resources for complimenting their broader units of work, often through ‘official’ hubs like Mind Lab and Space Lab. But we are also seeing evidence of the uptake of school-based subscriptions to ‘grass roots’ platforms like Twinkl, Sparkle Box and Teachers Pay Teacher (TpT) at Mornington. These platforms allow teachers to buy and sell curriculum resources. Emerging research on these platforms has cited numerous concerns around resource quality, often citing poor alignment with curriculum standards (Shelton et al., Citation2022). Yet, despite these concerns, Shelton and colleagues have argued these platforms are increasingly used by teachers and are working to extract significant value from schools.

Through this audit, we have been able to illustrate the expansion of private actors across all aspects of curriculum. Indeed, the extent and intensity of commercialisation across the curriculum lead to questions about equity and access to commercial resources, as well as the quality and accountability of these resources in improving teaching and learning practices. As other researchers have cautioned, the risk in commercialising the curriculum is that education is commodified, where private interests and profit making come at the expense of educational integrity (see O’Neill & Powell, Citation2020). This has implications for the social and democratic functions of schooling and can undermine the idea of education as a public good. However, in raising these concerns it is important not to fall into the, commercialisation is ‘bad’ trope without first understanding why teachers choose to commercialise and/or outsource aspects of their practice. We turn our attention to teacher decision-making about commercialisation and outsourcing in the following section.

Teacher decision-making about outsourcing and commercialisation

In what follows, we present interview data from the six participants about their decisions to outsource and/or access commercial resources within their KLA. The three categories of decision we constructed from the data were situational (i.e. responding to immediate contextual issues), distributed (i.e. collaborative and collective decisions made amongst the team of educators) and/or personal (i.e. focused on individual perceptions about best practice). While these types of decisions co-exist and are not easy to separate, in the discussion that follows we try to highlight the multiplicity of factors that influence teacher decision-making when procuring products and services from external providers.

Situational decisions

The general consensus from Mornington teacher participants was that their school could not run effectively without aspects of commercialisation and outsourcing. For example, teachers made situational decisions to outsource aspects of curriculum that involved the need for more specialised facilities or were considered higher risk activities in need of specialised instruction. In relation to HPE, a common description from participants about EPs such as Olympia Gymnastics was that it was a ‘one-stop-shop’ including an appropriate facility, equipment and specialised instruction for students. As Porsanger and Sandseter (Citation2021) argue, it is not uncommon for teachers to experience risk anxiety. Thus, it seems useful, even practical, to outsource certain activities to providers with specialised expertise. However, this ‘obvious’ decision came with the important caveat that teachers needed to ‘be wise in what we choose’ to commercialise and/or outsource (T2). Indeed, there was evidence that teachers were taking their time to make considered and deliberate decisions about the potential effectiveness of the programmes and/or products offered by EPs. For example, T3 discussed the need for an externally provided resource to align closely with their class programme,

I don’t like doing something because it’s available. I like to make sure it fits in with what we’re doing … [I’m] not really an opportunist … it’s definitely got to be curriculum-linked [and] relevant to the kids.

Similarly, T5 highlighted that outsourcing opportunities needed to work to ‘enhance student learning … and benefit the children’s experience within what we’re teaching, that we, ourselves, can’t create and produce at that level’. T5 makes the point here that EPs are value adding to curriculum delivery, often via a sense that their products and resources are more innovative or that their specialised expertise is more engaging for students (see, Deng et al., Citation2023). As justified by T3, engaging in commercialisation and outsourcing is not a decision based on being ‘lazy’, but one that can be ‘built on and contextualised afterwards’ in their usual teaching and learning practices. Indeed, T3 spoke about the role incursions (such as the travelling Science roadshows) and excursions (such as the field trip to the Sewage plant in the Social Sciences) play in deepening student engagement in learning.

Teachers also discussed the necessity of commercial resources in their standard, day-to-day practice. In English, for example, levelled and decodable readers were seen as essential resources for students learning to read. At the time of interviewing, the English KLA had received an additional $25,000 to invest in a series of updated readers. Teachers also noted that they were starting to invest in digital reading platforms like Quick60 and Epic. These were seen to enhance student access to more resources and allowed some automation of teacher decisions surrounding the learning to read process,

Once you have clicked on a name you can see the child’s [reading] level and the platform selects a range of reading material targeted at the level and area of interest [from over 40,000 books] … so if he loved dinosaurs or cars, he gets all these books … then you can read the book or listen to it … the kids just adore it. (T5)

A similar rationale was present within the Maths KLA and the shift towards the use of digital resources. These products are constantly updated by the commercial entity, and therefore, teachers were more confident that they were appropriately aligned to the objectives of the current curriculum. As T2 observes, ‘textbooks become out of date … so we stopped using hard copies and moved to the digital platform’. In fact, this need for curriculum alignment was also used as a rationalisation to say no to some EPs offering their services to Mornington. Participants argued that a number of EPs—particularly sporting organisations providing government funded programmes—did not understand the complexity of school timetabling, and the detrimental impact that their ‘free opportunity’ would have on teachers’ ability to achieve formal curriculum learning in HPE.

Essentially, situational decisions were made by teachers without them needing to engage in extensive discussion or debate within their KLA areas; quite simply, it had to be done. These decisions to outsource and/or commercialise—on the basis of specialised facilities and expertise, value-added learning opportunities, and enhanced curriculum connection—were seen as a necessary and obvious response to delivering the school curriculum in the best way possible. Here, we see that teachers are effectively choosing to engage in education marketisation to bring efficiency to their work practices.

Distributed decisions

Distributive decision-making focuses on how decisions are made collaboratively within a KLA. Mornington teachers suggested they would actually engage further in the commercialisation and outsourcing of curriculum if they had the funding available to do so. This aligns with previous research identifying the limitations of school budgets when purchasing products and services from EPs (Williams & Macdonald, Citation2015). Indeed, Mornington teachers emphasised how they made cost-saving decisions within their KLA teams, by ‘shopping around’ before committing to buy a particular resource (T1). T1 observed that ‘Kmart [often] has the exact same product but for a quarter of the price’ of what’s offered by a speciality education supplier. Teachers were encouraged to buy curriculum resources this way rather than go through ‘official supply chains’ by ‘bringing in their receipts, [and] doing a reimbursement form, and then that cost will come out of the team budget’ (T1). This same thriftiness was applied to books, where often local book suppliers were trumped by much cheaper international warehouses (such as, Book Depository) or even second-hand options (such as, the local Eco store). The SL also spoke of the opportunity to share resources with other local schools to bring down costs, ‘Sometimes it’s about shoulder-tapping your cluster schools to see whether they can jump on board and help share the costs, if you’re all identifying a common need’.

It also became evident that Mornington was doubling up on some commercial curriculum costs, particularly in relation to subscription-based resources, such as Twinkl, Sparkle Box and Teachers Pay Teachers (TpT). Some teachers had individual subscriptions to these platforms, some KLAs paid for them without realising other KLAs were using them, and then eventually, there was a decision to sign up for a ‘whole school’ subscription to each of these platforms given how useful all KLA teachers found them,

We’ve used them for our inquiries, reading, writing, maths; everything … There are just so many resources, and once you’ve paid for it, you get to download [the resources] … If you’re teaching something, and you just type it in, it gives you resource after resource. (T5)

Essentially, participants viewed the cost of subscriptions to resource platforms as ‘money well spent’ given their perception that these work to ease workload, or at least, lesson planning and preparation time.

Collaborative decisions moved beyond budget efficiencies to also understand the evidence-base of the products and services KLA teams were procuring from EPs. This included anecdotal conversations or word of mouth reviews within the teaching community (T3). For instance, T5 knew a teacher from another school who was using a reading programme that they then introduced to Mornington. The SL also reflected on similar conversations with other local school leaders, particularly in procuring data management software and student learning systems (SMS). They also spoke of the value of information collected through discussion within the local school community, particularly through parent and student surveys. As the SL recalled,

About three years ago we did a science survey and we got data and information that our students didn’t really feel science was being done, or if it was, they didn’t know they were doing science.

Findings from this survey revealed that teachers needed more support and better resourcing to teach science effectively. As T3 explained, this prompted Mornington’s procurement of commercial science kits and further engagement with science roadshows. Teachers reflected on how these products and services work to positively influence student learning through more innovative lessons and experiences.

Mornington staff also problematised their perception that commercialised and outsourced services were always educationally valuable. As T2 observed,

The biggest concern with EPs is whether they are truly educationally valuable… Probably the greatest challenge now is that filter process; so much of it is superficial. Some companies are really good with the whiz-bang presentation, and when you actually get to it, you go, oh there’s not a lot of substance to this.

T2 further reflected that teachers really needed to understand ‘what does and doesn’t have an impact on learning’ and that is ‘a big challenge we’re still attempting to grapple with’. Indeed, T2 highlights the role of teachers as critical consumers and that often, as previous research has argued, there is a need for further targeted professional development opportunities in helping teachers critically assess the broader implications of commercial products and services (Ni Chroinin, Citation2019; Wilkenson & Penney, Citation2016). These implications have included concerns about the increasing standardisation of curriculum across the globe (silencing important vernacular contexts, knowledge and culture) (Lingard, Citation2019), too much time or reliance on educational technology (Cohen, Citation2022), or too much money spent by the school for ‘new and shiny’ resources that are actually of low educational quality and lack the insight and pedagogical expertise of teachers employed at the school (Lingard et al., Citation2017).

Ultimately, distributed decision-making at Mornington involved staff making collaborative decisions that attempted to balance autonomy and responsibility. Their decision-making processes included informal discussion with colleagues and more formalised mechanisms for gaining new information (like the community survey). They highlighted that they are engaged in ethical decision-making about how products and services sourced from EPs would enhance the learning experiences of their students, and equally, pointed to potential dangers about being wrapped up in the ‘whizz bang’ and the need to pay more careful attention to the quality and efficacy of these services.

Personal decisions

Finally, it was useful to consider the personal decisions or individual rationales that influenced teacher decision-making about commercialisation and outsourcing of curriculum. Previous research has consistently evidenced that teachers are time poor (Lundahl et al., Citation2013; Stacey et al., Citation2022) and this was reflected by teachers at Mornington. As previously mentioned, a number of teachers had decided to invest in personal subscriptions to commercial resource platforms (before the school purchased ‘whole school’ accounts). Teachers indicated that online commercial subscription platforms such as Twinkl, TpT and Sparkle Box were not just saving them time but in their words were a ‘game changer’. As T1 observes,

It’s just easier, because you know it’s there; you can search whatever, and it’ll come up with games, PowerPoints … It’s easier because time is limited … I don’t have the time to create things myself.

T1 further observed that it was important for teachers not to have to ‘reinvent the wheel’ and that easy access to commercial resources was helping with that. Indeed, the proliferation of resource banks of ‘ready-made’ resources is increasingly being touted as a policy solution for education systems attempting to address concerns about teacher workload. However, as Carpenter and Shelton (Citation2024) argue in their study of 1500 teachers using TpT, while most of their participants valued TpT in saving them time, that time in reality shifted to them searching for materials, selecting materials and then modifying those materials for their individual classroom contexts. Thus, we note, the claim that online resource platforms save time is worthy of future study.

Interestingly, this same feeling of time pressure explained why Mornington staff sometimes let EPs into the school, even if there was not a clear link to the curriculum or inherent benefit to student learning. As explained by T4, ‘we had [an EP] the other day who wanted to do cricket, and in the end, I did say yes to them, but it didn’t link to anything we were doing’. T4 explained they felt worn down by continued requests from this provider and that it was easier to say yes and allow them to ‘tick their box, sell their product’ and be done with it. HPE, in particular, seemed to be the KLA suffering the brunt of these requests. This is likely given the fact that sports organisations in NZ are supported by government funding to deliver sports programmes in schools. Sporting clubs use these opportunities to market their sport and increase membership within their local clubs (Dyson et al., Citation2016). Other KLA teachers did note that there was a general proliferation of EPs marketing products and services to schools and that this ‘barrage of emails’ (T2) was increasing the administrative workload of teachers. Thus, Mornington staff were making decisions based on their own individual rationales and what they understood as being helpful in delivering curriculum and saving time.

Implications: making informed and ethical decisions

This audit evidences that commercialisation is widespread across the school curriculum at Mornington. While findings from this exploratory case study are not generalisable to all schools—as every school has its own unique demographics, organisational structures, and cultural nuances—it is useful for both practitioners and researchers to consider how deeply ingrained practices of commercialisation and outsourcing now are in everyday curriculum activities. Insights gleaned from this study suggest that teachers are working in complex environments. This includes the delivery of what they perceive as ‘risky’ activities or at least those that require specialist expertise (such as HPE, science, and the Arts). Equally, they are compelled to deliver innovative, student-focused activities and are continually balancing this need against the time they have available to plan and prepare for this. As our six Mornington participants observe, commercial products and services are now necessary to work effectively as a teacher. They are making situational, distributed and personal decisions in an attempt to simplify their work and bring a higher quality of curriculum engagement to their students.

As identified in earlier work (Hogan et al., Citation2018), teachers are not being seduced by commercialisation and outsourcing, but are showing that they are (mostly) discerning consumers within the educational marketplace. However, there are some useful nuances between the different types of decisions teachers are engaging with when choosing to commercialise and/or outsource aspects of the curriculum. We suggest that situational decisions are simply a matter of necessity in responding to the immediate context or in this case, mandated curriculum objectives and requirements (i.e. the perceived need for specialist instruction and equipment for the safe delivery of the gymnastics programme). These decisions are made regardless of cost and/or in/convenience to the school. Distributed decisions are those that require more collective discussion and debate, where teachers’ balance their ‘wish list’ against budget constraints and the available evidence about the quality or efficacy of the product/s their KLA team wish to purchase. Personal decisions seem to reflect how an individual teacher is attempting to best manage their own curriculum delivery expectations, be that innovation, student engagement, or simply, an attempt to manage their own workload better. What we find most interesting, and worthy of further investigation, is the way that teachers will spend their own money on buying resources or subscriptions to commercial platforms, such as TpT. While Mornington has taken this cost back from teachers with their ‘whole school’ subscription to these services, we suggest that the idea that commercial services can ‘save time’ is one that requires further in-depth exploration. Our concern is that generic resources, often designed for the U.S. market, require significant modification to align with vernacular contexts, particularly in terms of cultural appropriateness and curriculum alignment (see Shelton et al., Citation2022).

Returning to Biesta et al. (Citation2015), we suggest that teachers are attempting to balance their professional judgement, autonomy and responsibility in making decisions about curriculum resources. It is clear from our sample of participants from Mornington that teachers are exercising their professional judgement in considering the quality of commercial opportunities alongside their alignment with contextual factors, curriculum objectives, their own pedagogical beliefs and student needs. However, their autonomy to choose is, as our participants reflected, constrained by budget. Moreover, as T2 highlights in their interview, the staff at Mornington are still working towards understanding how they critically reflect on the educational value of commercial products and services. And as T4 further problematises, sometimes it is easier to let an external provider in, then to deal with their ongoing badgering for access to students. These examples point to the need to further invest in the ethical considerations of commercialisation and outsourcing. As Biesta et al. (Citation2015) argue, ethical responsibilities are not only based on professional knowledge but a deep understanding of the broader purpose of education and that critically navigating these complexities is difficult. Often, the need to simplify work, or allow an EP into the school, is a more immediate concern for teachers than the more abstract concept of ethics.

Ethical decision-making is in itself complex. Ethics is more than just adhering to rules; it is about confidently navigating moral grey areas. We suggest there are a number of ethical considerations that teachers need to better integrate into their decision-making. One of these is the idea of ethical procurement processes. This means that the acquisition of commercial resources—or the opening up of classrooms to external providers—is not just performed with ‘value for money’ at the fore, but a deeper evaluation of the entity supplying these services. This ensures, for instance, that EPs are meeting curriculum standards and objectives, are adhering to regulations around student data privacy and data sharing and that their products are evidenced to be contributing to quality educational outcomes (not just profit making or growing membership numbers). Indeed, there is now a plethora of research that delves into concerns of uninhibited commercialisation and outsourcing in schooling. These range from the impact of commercial entities on education policies and reform agendas, including what curriculum is important and what gets left out, or condensed (Ball, Citation2018), the type of pedagogies employed to enact the curriculum, particularly through ‘nudging’ schools to invest in (expensive) EdTech (Ideland, Citation2021), and how these decisions, taken away from the teacher, can leave them feeling de-professionalised (Stacey et al., Citation2022). Also, as our participants observed, there is a risk of becoming overwhelmed by predatory commercial behaviour (such as, the barrage of emails and advertising of services).

Already in NZ, the Ministry of Education has provided some useful steps in ensuring EPs are working ethically. One example is the accreditation of commercial entities selling student management systems (SMS) to schools. Schools using an accredited vendor are assured that this commercial entity will meet national data inferencing requirements and uphold data sharing regulations. Currently, there are six accredited SMS providers in NZ. This process of strict government oversight is unlikely to be feasible across the plethora of commercial products and services available across the curriculum. Instead, schools and/or KLA areas need to invest in this work themselves. For instance, the peak body for HPE teachers, ‘Physical Education New Zealand’ (PENZ), released a position paper in 2021 with recommendations for how HPE teachers should engage in outsourcing. In particular, the paper ends with a series of three questions that teachers should ask themselves before procuring an EP in HPE, including:

Where do the activities offered by the EP fit within our school’s physical education programme?

How will this EP add quality experiences, knowledge and understanding to our tamariki [children] and the physical education programme? and

Will the EP help us meet our teaching goals for physical education or is their involvement unnecessary?

While these questions are straightforward, PENZ (Citation2021) makes the useful suggestion that even a simple framework or checklist is often enough to ensure that the educative value of HPE is not disrupted in favour of an ‘exciting sports star’ (p. 2), or what T2 referred to in their KLA as a ‘whiz-bang presentation’. It seems useful for teachers to collectively consider the types of questions their KLA might ask to ensure they’re balancing autonomy and responsibility in making informed and ethical decisions.

Our final thought is one based on the ideology of publicness, and the systemic effects that these high levels of curriculum commercialisation and outsourcing in schools might bring. While beyond the scope of data collected in this paper, we wonder how the intensity of commercialisation is exasperating existing disparities or stratification between schools. We imagine that economically advantaged schools can procure superior products and services, whilst those schools who are already grappling with the financing of basic educational needs are further marginalised. Indeed, if teachers see value in commercial resources in reducing their workload, there is an emergent danger of the further loss of teachers from already ‘hard to staff’ schools (to those that are better resourced, and better connected to EPs). We argue that there is a need for ongoing robust conversation about the ethics of commercialisation and outsourcing, and how these principles develop from a teacher’s own personal responsibility to make ethical decisions to broader distributed and situational decisions that need to better incorporate concerns of equity, the sustainability of educational practices offered by EPs, and the need for schools and teachers to maintain control over the critical aspects of curriculum. While commercialisation and outsourcing are clearly important aspects of curriculum delivery, these should never be considered as a substitute or replacement to expert classroom teachers.

Ethics declaration

This study has been cleared in accordance with the ethical review guidelines and processes of the University of Queensland, ID JC03263.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the teachers and school leaders from our case school for their time and contributions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jackie Cowan

Jackie Cowan is Senior Lecturer in Physical Education and Sport Coaching at the University of Canterbury, Aotearoa, New Zealand. Her research interests broadly focus on the areas of Health and Physical Education and Sport Coaching policy and practice. Her current research interests focus on coach development, and pedagogy and outsourcing of HPE in primary school contexts.

Leigh Sperka

Leigh Sperka is a lecturer in the School of Human Movement and Nutrition Sciences at the University of Queensland. Her research focuses on the outsourcing of education. This includes investigating decision-making around the practice, how outsourcing impacts curriculum, pedagogy, and assessment, and student perspectives on outsourced lessons.

Anna Hogan

Anna Hogan is an Associate Professor in the School of Teacher Education and Leadership at the Queensland University of Technology. Her research interests broadly focus on education policy and practice. She currently works on a number of research projects, including philanthropy in Australian public schooling, teacher work intensification and the role of commercial ‘time saving’ devices.

Eimear Enright

Eimear Enright is an Honorary Associate Professor and educational researcher in the School of Human Movement and Nutrition Sciences at the University of Queensland.

References

- Ball, S. J. (2018). The tragedy of state education in England: Reluctance, compromise and muddle–a system in disarray. Journal of the British Academy, 6(1), 207–238. https://doi.org/10.5871/jba/006.207

- Ball, S. J., & Goodson, I. F. (1985). Understanding teachers: Concepts and contexts. Teachers’ Lives and Careers, 1, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203139523

- Ball, S. J., & Youdell, D. (2008). Hidden privatisation in public education.

- Biesta, G., Priestley, M., & Robinson, S. (2015). The role of beliefs in teacher agency. Teachers & Teaching, 21(6), 624–640. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2015.1044325

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Buchanan, R. (2015). Teacher identity and agency in an era of accountability. Teachers & Teaching, 21(6), 700–719. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2015.1044329

- Burch, P. (2009). Hidden markets: The new education privatization. Routledge.

- Carpenter, J. P., & Shelton, C. C. (2024). Educators’ perspectives on and motivations for using TeachersPayTeachers. com. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 56(2), 218–232.

- Codd, J. (2005). Teachers as ‘managed professionals’ in the global education industry: The New Zealand experience. Educational Review, 57(2), 193–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/0013191042000308369

- Cohen, D. (2022). Any time, any place, any way, any pace: Markets, EdTech, and the spaces of schooling. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 56(1), 270–287. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X221084708

- Cowan, J., Hogan, A., & Enright, E. (2022). The commercialisation of school administration: One school’s enactment of a student management system in Aotearoa New Zealand. Journal of Educational Administration and History, 54(2), 193–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220620.2021.1988524

- Deng, C., Philpot, R. A., Legge, M., Ovens, A., & Smith, W. (2023). Should primary school PE be outsourced? An analysis of students’ perspectives. Curriculum Studies in Health and Physical Education, 14(3), 357–374. https://doi.org/10.1080/25742981.2022.2140594

- Dyson, B., Gordon, B., Cowan, J., & McKenzie, A. (2016). External providers and their impact on primary physical education in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Asia-Pacific Journal of Health, Sport and Physical Education, 7(1), 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/18377122.2016.1145426

- Enright, E., Kirk, D., & Macdonald, D. (2020). Expertise, neoliberal governmentality and the outsourcing of health and physical education. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 41(2), 206–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2020.1722424

- Haw, J. Y., Nalipay, M. J. N., & King, R. B. (2023). Perceived relatedness-support matters most for teacher well-being: A self-determination theory perspective. Teachers & Teaching, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2023.2263736

- Hedges, H. (2012). Teachers’ funds of knowledge: A challenge to evidence-based practice. Teachers & Teaching, 18(1), 7–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2011.622548

- Hensley, K. K., & Huddle, S. M. (2021). Know what you need: A special educator’s guide to locating and asking for classroom curricular resources. Teaching Exceptional Children, 53(3), 226–233. https://doi.org/10.1177/0040059920983238

- Hogan, A., Enright, E., Stylianou, M., & McCuaig, L. (2018). Nuancing the critique of commercialisation in schools: Recognising teacher agency. Journal of Education Policy, 33(5), 617–631. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2017.1394500

- Hogan, A., Thompson, G., & Mockler, N. (2022). Romancing the public school: Attachment, publicness and privatisation. Comparative Education, 58(2), 164–186. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2021.1958995

- Hollands, F., Pan, Y., & Escueta, M. (2019). What is the potential for applying cost-utility analysis to facilitate evidence-based decision-making in schools? Educational Researcher, 48(5), 287–295. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X19852101

- Holloway, J., & Keddie, A. (2019). ‘Make money, get money’: How two autonomous schools have commercialised their services. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 40(6), 889–901. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2018.1451305

- Ideland, M. (2020, August 18). Google and the end of the teacher? How a figuration of the teacher is produced through an ed-tech discourse. Learning, Media and Technology. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2020.1809452

- Ideland, M. (2021). Google and the end of the teacher? How a figuration of the teacher is produced through an ed-tech discourse. Learning, Media and Technology, 46(1), 33–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2020.1809452

- Jobér, A. (2024). Private actors in policy processes. entrepreneurs, edupreneurs and policyneurs. Journal of Education Policy, 39(1), 20–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2023.2166128

- Kenway, J., Bigum, C., & Fitzclarence, L. (1993). Marketing education in the postmodern age. Journal of Education Policy, 8(2), 105–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/0268093930080201

- Lingard, B. (2019). The Global Education Industry, Data Infrastructures, and the Restructuring of Government School Systems. In M. Parreira do Amaral, G. Steiner-Khamsi, & C. Thompson (Eds.), Researching the Global Education Industry (pp. 135–155). Springer International Publishing.

- Lingard, B., Sellar, S., & Lewis, S. (2017, July 27). Accountabilities in schools and school systems. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education. Retrieved May 13, 2024, from https://oxfordre.com/education/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.001.0001/acrefore-9780190264093-e-74

- Lundahl, L., Arreman, I. E., Holm, A., & Lundström, U. (2013). Educational marketization the Swedish way. Education Inquiry, 4(3), 497–517. https://doi.org/10.3402/edui.v4i3.22620

- Mockler, N. (2020). Discourses of teacher quality in the Australian print media 2014–2017: A corpus-assisted analysis. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 41(6), 854–870. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2018.1553849

- Ní Chróinín, D., & O’Brien, N. (2019). Primary school teachers’ experiences of external providers in Ireland: Learning lessons from physical education. Irish Educational Studies, 38(3), 327–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2019.1606725

- Olstad, B. H., Berg, P. R., & Kjendlie, P. L. (2021). Outsourcing swimming education—Experiences and challenges. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18010006

- O’Neill, J. (2017). Contesting PLD services: The case of CORE Education. Open Review of Educational Research, 4(1), 192–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/23265507.2017.1394799

- O’Neill, J., & Powell, D. (2020). Charities and state schooling privatizations in Aotearoa New Zealand. Privatisation and Commercialisation in Public Education: How the Public Nature of Schooling Is Changing, 36–51. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9780429330025-4/charities-state-schooling-privatisations-aotearoa-new-zealand-john-neill-darren-powell

- Physical Education New Zealand. (2021). External providers and teaching quality physical education [Postion statement]. https://penz.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/External-Providers-position-paper.pdf

- Porsanger, L., & Sandseter, E. B. H. (2021). Risk and safety management in physical education: Teachers’ perceptions. Education Sciences, 11(7), 321. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11070321

- Powell, D. (2015). Assembling the privatisation of physical education and the ‘inexpert’ teacher. Sport, Education and Society, 20(1), 73–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2014.941796

- Powell, D. (2019). Schools, corporations, and the war on childhood obesity: How corporate philanthropy shapes public health and education. Routledge.

- Russo, J., Corovic, E., Hubbard, J., Bobis, J., Downton, A., Livy, S., & Sullivan, P. (2022). Generalist primary school teachers’ preferences for becoming subject matter specialists. Australian Journal of Teacher Education (Online), 47(7), 38–57. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2022v47n7.3

- Selwyn, N., Hillman, T., Eynon, R., Ferreira, G., Knox, J., Macgilchrist, F., & Sancho-Gil, J. M. (2020). What’s next for ed-tech? Critical hopes and concerns for the 2020s. Learning, Media and Technology, 45(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2020.1694945

- Shelton, C. C., Koehler, M. J., Greenhalgh, S. P., & Carpenter, J. P. (2022). Lifting the veil on TeachersPayTeachers. com: An investigation of educational marketplace offerings and downloads. Learning, Media and Technology, 47(2), 268–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2021.1961148

- Stacey, M., Wilson, R., & McGrath-Champ, S. (2022). Triage in teaching: The nature and impact of workload in schools. Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 42(4), 772–785. https://doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2020.1777938

- Stake, R. (2003). Case studies. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Strategies of qualitative inquiry (2nd ed. pp. 134–164). Sage.

- Thrupp, M., Powell, D., O’Neill, J., Chernoff, S., & Seppänen, P. (2021). Private actors in New Zealand schooling: Towards an account of enablers and constraints since the 1980s. New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, 56(1), 23–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40841-021-00194-4

- Vanlommel, K., Van Gasse, R., Vanhoof, J., & Van Petegem, P. (2017). Teachers’ decision-making: Data based or intuition driven? International Journal of Educational Research, 83, 75–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2017.02.013

- Verger, A., Lubienski, C., & Steiner-Khamsi, G. (Eds.). (2016). The emergence and structuring of the global education industry: Towards an analytical framework. In World yearbook of education 2016 (pp. 23–44). Routledge.

- Wilkinson, S. D., & Penney, D. (2016). The involvement of external agencies in extra-curricular physical education: Reinforcing or challenging gender and ability inequities?. Sport, Education & Society, 21(5), 741–758. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2014.956714

- Williams, B. J., & Macdonald, D. (2015). Explaining outsourcing in health, sport and physical education. Sport, Education and Society, 20(1), 57–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2014.914902

- Woods, P., Jeffrey, B., Troman, G., & Boyle, M. (2019). Restructuring schools, reconstructing teachers: Responding to change in the primary school. Routledge.

- Yoon, E. S., Young, J., & Livingston, E. (2020). From bake sales to million-dollar school fundraising campaigns: The new inequity. Journal of Educational Administration and History, 52(1), 25–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220620.2019.1685473