ABSTRACT

Introduction

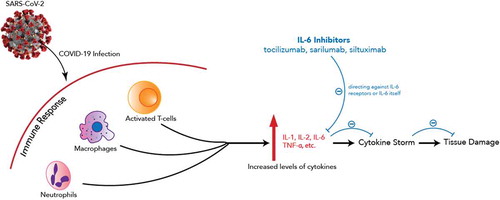

A novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19) has caused significant life loss and healthcare burden globally. COVID-19 is known to cause a cytokine release syndrome (CRS) like response, and interleukin-6 (IL-6) is one of the cytokines involved. Clinicians are using IL-6 inhibitors to CRS, and researchers are investigating the use of IL-6 inhibitors, namely tocilizumab, sarilumab, siltuximab, in COVID-19 management.

Areas covered

In this article, we will discuss the pharmacology of these three inhibitors and summarize available clinical data via literature search on PubMed with keywords of tocilizumab, sarilumab, siltuximab, and COVID-19. While awaiting more data from randomized clinical trials on these drugs, observational studies and clinical reports have demonstrated IL-6 inhibitors showed some benefits in improving clinical outcome and a well-tolerated safety profile.

Expert opinion

There is a role for suppressing the immune response with IL-6 inhibitors that will continue to require investigation. These agents are available and have demonstrated a mild safety profile. There may be advantages to a targeted approach to suppressing the hyperinflammatory state of the disease. Timing, the long-term effects, and what cocktail of medications demonstrates the strongest outcomes are all important considerations as IL-6 inhibitors continue to be evaluated in this global pandemic.

1. Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), was first identified in Wuhan, China in December 2019. Since then, the disease has spread globally and resulted in an unprecedented ongoing global pandemic. By the end of September 2020, over 35 million COVID-19 cases and over 1 million deaths have been reported globally [Citation1].

While public health interventions such as hand washing, social distancing, and quarantine are being adopted worldwide, there is a lack of targeted medical treatment or vaccine for COVID-19. Several pharmaceutical agents have been proposed as candidates for COVID-19 treatment based on their previously observed antiviral activities or to treat the hyperinflammatory phase. Over 400 clinical studies are registered on clinicaltrials.gov and recruiting to study various potential therapies. Yet, there are limited data to date to support the use of these agents [Citation2].

To address the hyperinflammatory phase of COVID-19, Interleukin 6 (IL-6) antagonists are among the drug candidates. COVID-19 cytometry analysis found an increase in Th17 cells, a type of helper T cells stimulated by proinflammatory cytokines including IL-6, which contributes to the immunological defense during infection [Citation3]. However, the excessive upregulation of proinflammatory cytokines observed in COVID-19 patients has raised awareness of early intervention to prevent the life-threatening cytokine release syndrome (CRS)-like phase of the disease [Citation4]. describes the mechanism of action of IL-6 inhibitors in managing COVID-19 infection. A recent study of 40 COVID-19 patients observed increases in proinflammatory cytokines including IL-6 among severe cases compared to mild cases, highlighting the association between COVID-19 severity and cytokine storm [Citation5]. IL-6 antagonists such as tocilizumab, sarilumab, and siltuximab are being considered to address the unmet need in COVID-19 treatment and resultant CRS. Yale School of Medicine and Yale-New Haven Hospital recommend clinicians to consider one 8 mg/kg dose of tocilizumab not exceeding 800 mg in severe COVID-19 cases showing no clinical improvement within 24–48 hours of steroid therapy [Citation6]. With the same total dose allowance, the Brigham and Women’s Hospital recommends 4–8 mg/kg intravenous dose and allows a second dose in cases of inadequate response to the first one in the context of a clinical trial [Citation7]. Brigham also lists siltuximab 11 mg/kg single intravenous dose as an alternative IL-6 antagonist. Sarilumab was only available as a part of a clinical trial (NCT04315298), but this trial has been stopped in the United States [Citation8].

Given the potential role of IL-6 antagonists and emerging data from clinical trials, the purpose of this review is to discuss relevant clinic data regarding IL-6 antagonists and share opinions on their roles in COVID-19 management.

2. The market

2.1. Overview of the market

COVID-19 treatment at this time is focused on use of antivirals and immunosuppression. For antiviral therapy, remdesivir as an investigational drug is available under an Emergency Use Authorization (EAU). Systematic inflammatory mitigation with dexamethasone has been reported to lower the 28-day mortality in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 receiving invasive mechanical ventilation or oxygen support [Citation9]. Targeted immunosuppression with IL-6 antagonists is believed to prevent disease progression and CRS via IL-6 inhibition and blockage of the inflammatory pathway. With a similar mechanism, three IL-1 antagonists – anakinra, canakinumab, and rilonacept – are also currently being evaluated. This review focuses specifically on the three potential IL-6 antagonists: tocilizumab, sarilumab, and siltuximab. summarizes major studies in the discussion can be found at the end of this section.

Table 1. Major trials included in the discussion

2.2. Tocilizumab

2.2.1. Clinical pharmacology

Tocilizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody that inhibits IL-6-mediated signaling through binding to IL-6 receptors. Tocilizumab is approved by the FDA to be used for rheumatoid arthritis, giant cell arteritis, polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis, systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis, as well as chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell-induced CRS [Citation10]. A population analysis of 1,793 patients with rheumatoid arthritis found that the maximum concentration increased proportionally with the dose and doses above 800 mg per infusion resulted in a significantly higher trough and peak concentration than the population averages [Citation11]. The median time to reach maximum concentration post weekly intravenous administration of tocilizumab is 2.8 days [Citation8]. In a clinical study on CRS, pharmacodynamic changes after one or two doses of tocilizumab resulted in defervescence [Citation12].

2.2.2. Clinical efficacy

Tocilizumab has established clinical data on its efficacy in managing CAR T-cell induced CRS. Tocilizumab reduced fever and severe CRS symptoms within one to 3 days among 16 patients receiving CAR T-cell therapy [Citation13]. In another study, four patients with CAR T-cell induced CRS showed rapid defervescence blood pressure stabilization, and biomedical normalization after receiving tocilizumab [Citation14]. Tocilizumab was also shown to be effective in the treatment of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis due to T-cell receptor-engaging antibody blinatumomab [Citation15]. In one severe CRS case study, tocilizumab treated hypotension and hypoxia caused by CRS as well as neurotoxicity manifested as dysgraphia, confusion, and disorientation [Citation16].

Data on tocilizumab in COVID-19 are mostly from case reports and observation studies thus remain inconclusive at the moment. Preliminary data from a non-peer-reviewed study from China showed that body temperature of all 21 patients returned to normal on the same day of tocilizumab administration, followed by rapid oxygen saturation improvement [Citation17]. In this study, tocilizumab was given as a single intravenous dose of 400 mg, and three patients required one additional dose of 400 mg within 12 hours due to fever. Additionally, in a retrospective study, 10 out of 15 moderate to severe COVID-19 patients achieved rapid improvement and clinical stabilization after receiving 80 to 600 mg tocilizumab doses [Citation18]. In this study, 3 out of 4 critically ill patients only received a single dose of tocilizumab (480 mg, 600 mg, and 320 mg, respectively) and subsequently decreased. Karolinska University Hospital in Sweden reported an association of tocilizumab with a shorter duration on mechanical ventilation and hospital stay in a retrospective cohort study, although tocilizumab failed to reduce all-cause mortality [Citation19]. A study from Yale involving 239 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 found that patients who received tocilizumab exhibited improved oxygenation status after 3 days, inflammatory biomarker profiles, and expected survival with few adverse events [Citation20]. The clinical course timeframe is in accordance with pharmacology data of tocilizumab where the maximal concentration was reached 2.8 days post-administration. A retrospective observational study at 13 hospitals in the United States found among 210 patients who received tocilizumab, tocilizumab was associated with hospital mortality reduction [Citation21]. As tocilizumab is also available in subcutaneous dosage form, a study of 12 patients in Italy showed improvement in lung manifestations, normalization of oxygen status, and no incidence of grade 4 CRS in all patients after the administration of subcutaneous tocilizumab [Citation22]. Another retrospective study of 10 patients offered an additional perspective on the potential benefit of subcutaneous tocilizumab [Citation23]. However, the randomized controlled COVACTA trial of tocilizumab among hospitalized patients with COVID-19 sponsored by Roche revealed a disappointing result as Roche reported that tocilizumab failed to meet primary endpoints [Citation24]. In COVACTA trial, there were no significant differences on clinical improvement or mortality between 294 patients on tocilizumab 8 mg/kg and 144 patients on placebo, although the tocilizumab group had a shorter median time to hospital discharge and ICU stay than the placebo group [Citation25]. Ongoing clinical trials are examining the benefits of tocilizumab on time to discharge and duration of ICU stay.

2.3. Sarilumab

2.3.1. Clinical pharmacology

Sarilumab is a human monoclonal antibody that antagonizes IL-6 receptors. Sarilumab is approved by the FDA to treat moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis unresponsive to one or more disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs [Citation26]. A population pharmacokinetic study of sarilumab found that it took 2 to 4 days to reach peak concentration and steady-state exposure doubled when the dose increased from 150 mg subcutaneous every 2 weeks to 200 mg subcutaneous every 2 weeks [Citation27]. Single-dose subcutaneous sarilumab is shown to reduce C-reactive protein and absolute neutrophil counts to nadir [Citation26]. Comparative pharmacodynamic studies noted common adverse reactions to sarilumab included neutropenia, nasopharyngitis, and injection-site erythema, but the efficacy and safety profiles of sarilumab were similar to those of tocilizumab [Citation28,Citation29].

2.3.2. Clinical efficacy

Although sarilumab is also an IL-6 inhibitor, its efficacy has only been evaluated in rheumatoid arthritis. Unlike tocilizumab, sarilumab is not being utilized in the management of CRS [Citation30]. With the exhaustion of tocilizumab, sarilumab was proposed as an alternative. A report of eight patients’ clinical course described early administration of sarilumab to be beneficial in reducing the echo score and improving clinical outcomes [Citation31]. Yet, another observational study of patients without invasive mechanical ventilation found that sarilumab resulted in faster recovery only in specific patient groups with minor pulmonary consolidation [Citation32]. A recent report of 53 patients on sarilumab showed short-term clinical improvement and safety, indicating a potential use of this agent to manage COVID-19 [Citation33]. There is one current registered clinical trial by the manufacturers to evaluate the efficacy and safety of sarilumab in hospitalized patients with severe COVID-19 [Citation8]. However, the most recent update from the manufacturers has indicated that sarilumab failed to meet the endpoint of improved clinical status among hospitalized patients requiring mechanical ventilation [Citation34]. Subsequently, the U.S.-based trial of sarilumab has been terminated. Sanofi maintained the trial outside the U.S., and further details on the clinical efficacy and safety of sarilumab may be available once the result is available.

2.4. Siltuximab

2.4.1. Clinical pharmacology

Siltuximab is a chimeric monoclonal antibody that prevents IL-6 from binding to its receptor. Siltuximab is approved by the FDA to treat multicentric Castleman’s disease (MCD) in HIV and HHV-8 negative patients [Citation35]. A population pharmacokinetic study modeled that siltuximab 11 mg/kg was associated with half-lives of approximately 21 days [Citation36]. Steady state is achieved by the sixth infusion with the dosing regimen of every 3 weeks, and time to peak concentration after a single dose is unknown [Citation35].

2.4.2. Clinical efficacy

An observational cohort study in Italy compared supportive care and siltuximab in COVID-19 patients requiring ventilation. In this study, 30 patients received an 11 mg/kg dose of siltuximab while 188 patients received supportive care. The findings showed a significant reduction in inflammation and 30-day mortality in the siltuximab group, and siltuximab was well tolerated [Citation37]. No additional data are available currently for assessing the efficacy and safety of siltuximab.

3. Conclusion

As COVID-19 continues posing a great threat to the health of people worldwide, there is an urgent need to explore and evaluate the effectiveness of clinical options. Biomedical and pathology data indicate the association between COVID-19 clinical outcome and inflammatory cytokines. Patients with severe COVID-19 require intensive and urgent care to prevent life-threatening CRS. IL-6 antagonists may be important therapy options to achieve this need. However, there are insufficient data currently to establish the efficacy and safety of tocilizumab, sarilumab, or siltuximab in COVID-19 management. Although data from several preliminary reports suggests benefit with tocilizumab, results of the randomized controlled clinical trials are needed to establish further recommendations of these drugs in patients with severe COVID-19.

4. Expert opinion

In our expert opinion, there is a role for a targeted approach to addressing the hyperinflammatory phase of COVID-19 disease. These agents are available and have demonstrated a mild safety profile. From the pharmacy supply perspective, the system has yet experienced any drug shortage issues of these three agents in the United States but continuous monitoring should be established globally to assess drug availability in clinical use [Citation39]. Clinically, these agents have mild safety profiles established from clinical trials for other indications. Reports so far of tocilizumab and siltuximab have not been shown to exhibit side effects that have been observed in other COVID-19 drug candidates [Citation40,Citation41]. However, caution is advised for infection, cytomegalovirus viremia in particular, and some rare serious adverse events including bowel perforation. Some of the preliminary data on tocilizumab report increased infections while others show similar rates of infections [Citation22,Citation42].

Through a pharmacoeconomics and public health lens, even if these drugs are found to be effective and safe in COVID-19 management, they are expensive drugs that might not be accessible at all in countries where access to medication is a preexisting public health problem [Citation43]. In the United States and most countries in Europe, IL-6 inhibitors are supplied with respective drug manufacturers. However, other countries where clinical trials are not available, IL-6 inhibitors might be surprisingly costly, in high demand, and even black-marketed. Various capacity of healthcare systems, access to medications, and patients’ inability to pay for expensive drugs should encourage us to explore ways to ensure access and continue evaluating other more cost-effective and readily available drugs in managing CRS and COVID-19. At the moment, it is unclear the extent to which IL-6 inhibitors increase the quality of life and clinical improvement versus other therapies as no head-to-head comparisons have been done. While there are cheaper alternatives to broadly address the hyperinflammatory phase of the disease, the side effects including hyperglycemia and infection are present with glucocorticosteroid use. Therefore, clinicians should always consider using the right medications at the right timing in the right people when making therapeutic plans in managing COVID-19.

Through the clinical lens, there may be advantages to a targeted approach to suppressing the hyperinflammatory state of the disease. Timing, the long-term effects, and what cocktail of medications demonstrates the strongest outcomes are all important considerations as IL-6 inhibitors continue to be evaluated in this global pandemic. Moving upstream in the inflammatory response, there are other studies targeting other immunomodulatory therapy such as IL-1 blockade or GM-CSF blockade to assess their roles in COVID-19 treatment [Citation35,Citation44]. It is currently unknown whether an upstream IL-1 blockade would result in more benefits due to a lack of studies on anakinra, an IL-1 inhibitor, and head-to-head comparisons between IL-1 and IL-6 inhibitors. Overall, to tackle COVID-19, treatment strategies will likely require a combination of therapies as the immune response requires a balanced approach to preserve the immune system’s ability to clear the virus. In our opinion, we need to await IL-6 trials to gain further insights on the most appropriate patient populations to receive IL-6 inhibitors, the right timing of and route of administration, and other necessary combination therapies.

Although there is disappointing news released regarding the Phase-3 data of tocilizumab and sarilumab, real-world experience of IL-6 antagonists and other immunosuppressants continues to accrue. Despite the COVACTA (NCT04320615) result from Roche, the company has REMDACTA (NCT04409262), EMPACTA (NCT04372186), and MARIPOSA (NCT04363736) trials to evaluate intravenous tocilizumab in COVID-19 management. Besides COVACTA trial discussed previously, Roche recently reported that tocilizumab was shown to reduce the need for mechanical ventilation in COVID-19 patients in the EMPACTA trial [Citation45]. As indicated previously, subcutaneous administration of tocilizumab may provide an additional role. Observational and preliminary data for tocilizumab is showing some benefit in severe COVID-19 patients. Therefore, additional data are required to further assess the role of tocilizumab based on the route of administration, dosing, timing, and long-term safety profile. The same principle applies to other IL-6 inhibitors and additional immunomodulatory agents. Vaccine development is ongoing, but there remains a great time gap until vaccines are available to the public. While we continue evaluating potential options and collaborating our research efforts, it remains important for the public to combat this global health crisis by practicing non-pharmacologic interventions pursuant to recommendations from national health agencies in respective countries.

Article highlights

Patients with COVID-19 pneumonitis may experience an excessive amount of circulating proinflammatory cytokines that can cause cytokine release syndrome (CRS). Interleukin (IL)-6 is a type of proinflammatory cytokine, and strategies to reduce the amount of IL-6 have been considered as a method to manage patients with COVID-19.

Three IL-6 inhibitors, tocilizumab, sarilumab, siltuximab, are being researched to investigate their roles in managing COVID-19. Sarilumab and tocilizumab are indicated for rheumatoid arthritis, while tocilizumab has additional indications for other immunological diseases. Siltuximab is indicated for multicentric Castleman’s disease. The ability of these agents to reduce immune reactions prompts their trials in COVID-19.

Observational studies of sarilumab also indicated some benefits of this drug in COVID-19 management. However, the only randomized controlled trial based in the United States has been terminated after a failure of meeting the primary endpoint of the trial. The drug manufacturer continues its trial outside of the United States. We currently do have not adequate report for siltuximab. Only observational studies are currently available, and data are not adequate enough to draw conclusions regarding the efficacy and safety of siltuximab.

To manage COVID-19, further data are necessary to guide clinicians to determine the benefits of monotherapy vs. combination therapy in the most appropriate subset of patients. Additionally, more studies are needed to determine the timing of administration, the route of administration, as well as short-term and long-term adverse drug reactions.This box summarizes the key points contained in the article.

Declaration of interest

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Reviewer disclosures

One peer reviewer has received a travel grant from Kiniksa Pharmaceuticals Ltd. to attend the 2019 AHA Scientific Sessions. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no other relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Johns Hopkins University & Medicine. COVID-19 map. [ cited 2020 Aug 26]. Available from: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html

- Sanders JM, Monogue ML, Jodlowski TZ, et al. Pharmacologic treatments for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a review. JAMA. Published2020:323(18);1824-1836.

- Chen G, Wu D, Guo W, et al. Clinical and immunological features of severe and moderate coronavirus disease 2019. J Clin Investig. 2020;130(5):2620–2629.

- Picchianti Diamanti A, Rosado MM, Pioli C, et al. Cytokine release syndrome in COVID-19 patients, A new scenario for an old concern: the fragile balance between infections and autoimmunity. IJMS. 2020;21(9):3330.

- Liu J, Li S, Liu J, et al. Longitudinal characteristics of lymphocyte responses and cytokine profiles in the peripheral blood of SARS-CoV-2 infected patients. EBioMedicine. 2020;55:102763.

- Yale School of Medicine. COVID-19 treatment adult algorithm. [ Published 2020 Apr 27; cited 2020 May 17]. Available from: https://files-profile.medicine.yale.edu/documents/e91b4e5c-ae56-4bf1-8d5f-e674b6450847

- Bridgham and Women’s Hospital. Brigham and women’s hospital COVID-19 clinical guidelines. [cited 2020 May 17]. Available from: https://covidprotocols.org/

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of sarilumab in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. [ Published 2020 Apr 6; cited 2020 May 17]. Available from https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04315298

- The RECOVERY Collaborative Group. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19 — preliminary report. N Engl J Med. Published online 2020 July 17:NEJMoa2021436.

- Actemra® (tocilizumab). Published online 2017.

- Frey N, Grange S, Woodworth T. Population pharmacokinetic analysis of tocilizumab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;50(7):754–766.

- Fitzgerald JC, Weiss SL, Maude SL, et al. Cytokine release syndrome after chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(2):e124–e131.

- Davila ML, Riviere I, Wang X, et al. Efficacy and toxicity management of 19-28z CAR T cell therapy in B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(224):224ra25–224ra25.

- Porter DL, Hwang W-T, Frey NV, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells persist and induce sustained remissions in relapsed refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(303):303ra139–303ra139.

- Teachey DT, Rheingold SR, Maude SL, et al. Cytokine release syndrome after blinatumomab treatment related to abnormal macrophage activation and ameliorated with cytokine-directed therapy. Blood. 2013;121(26):5154–5157.

- Neelapu SS, Tummala S, Kebriaei P, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy — assessment and management of toxicities. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15(1):47–62.

- Xu X, Han M, Li T, et al. Effective treatment of severe COVID-19 patients with tocilizumab. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117(20):10970–10975.

- Luo P, Liu Y, Qiu L, et al. Tocilizumab treatment in COVID‐19: A single center experience. J Med Virol. 2020;92(7):814–818.

- Eimer J, Vesterbacka J, Svensson A-K, et al. Tocilizumab shortens time on mechanical ventilation and length of hospital stay in patients with severe COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study. J Intern Med. Published online 2020 Aug 3.

- Price CC, Altice FL, Shyr Y, et al. Tocilizumab treatment for cytokine release syndrome in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Chest. 2020 Oct;158(4)1397-1408.

- Biran N, Ip A, Ahn J, et al. Tocilizumab among patients with COVID-19 in the intensive care unit: a multicentre observational study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020;2(10):e603–e612.

- Guaraldi G, Meschiari M, Cozzi-Lepri A, et al. Tocilizumab in patients with severe COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020 Aug; 2(8):e474-e484.

- Potere N, Di Nisio M, Rizzo G, et al. Low-dose subcutaneous tocilizumab to prevent disease progression in patients with moderate COVID-19 pneumonia and hyperinflammation. Int J Infect Dis. Published online 2020 Aug 5;100:421–424.

- Roche. Roche provides an update on the phase III COVACTA trial of Actemra/RoActemra in hospitalised patients with severe COVID-19 associated pneumonia. [cited 2020 Jul 29]. Available from: https://www.roche.com/investors/updates/inv-update-2020-07-29.htm

- Rosas I, Bräu N, Waters M, et al. Tocilizumab in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. medRxiv. Published online 2020 Jan 1.

- Kevzara® (sarilumab). Published online 2017.

- Xu C, Su Y, Paccaly A, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of sarilumab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2019;58(11):1455–1467.

- Emery P, Rondon J, Parrino J, et al. Safety and tolerability of subcutaneous sarilumab and intravenous tocilizumab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology. 2019;58(5):849–858.

- Ishii T, Sato Y, Munakata Y, et al. AB0472 Pharmacodynamic effect and safety of single-dose sarilumab sc or tocilizumab iv or sc in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). In Rheumatoid arthritis – biological DMARDs BMJ Publishing Group Ltd and European League Against Rheumatism; 2018. p 1397–1398.

- Riegler LL, Jones GP, Lee DW. Current approaches in the grading and management of cytokine release syndrome after chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy. TCRM. 2019;15:323–335.

- Benucci M, Giannasi G, Cecchini P, et al. COVID‐19 pneumonia treated with Sarilumab: A clinical series of eight patients. J Med Virol. Published online 2020 June 16;jmv.26062.

- Della-Torre E, Campochiaro C, Cavalli G, et al. Interleukin-6 blockade with sarilumab in severe COVID-19 pneumonia with systemic hyperinflammation: an open-label cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;;79:1277-1285.

- Gremese E, Cingolani A, Bosello SL, et al. Sarilumab use in severe SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia. EClinicalMedicine. Published online 2020 Oct;100553.

- Sanofi, Regeneron. Sanofi and Regeneron provide update on Kevzara® (sarilumab) Phase 3 U.S. trial in COVID-19 patients. [cited 2020 Aug 26]. Available from: https://www.sanofi.com/en/media-room/press-releases/2020/2020-07-02-22-30-00

- Sylvant® (siltuximab). Published online 2019.

- Nikanjam M, Yang J, Capparelli EV. Population pharmacokinetics of siltuximab: impact of disease state. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2019;84(5):993–1001.

- Gritti G, Raimondi F, Ripamonti D, et al. IL-6 signalling pathway inactivation with siltuximab in patients with COVID-19 respiratory failure: an observational cohort study. medRxiv. Published online 2020 Jan 1.

- Perrone F, Piccirillo MC, Ascierto PA, et al. Tocilizumab for patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. The single-arm TOCIVID-19 prospective trial. J Transl Med.2020 Oct 21;18(1):405

- American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Drug shortages list. [cited 2020 May 18]. Available from: https://www.ashp.org/Drug-Shortages/Current-Shortages/Drug-Shortages-List?page=CurrentShortages&loginreturnUrl=SSOCheckOnly

- Thomas SK, Suvorov A, Noens L, et al. Evaluation of the QTc prolongation potential of a monoclonal antibody, siltuximab, in patients with monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance, smoldering multiple myeloma, or low-volume multiple myeloma. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2014;73(1):35–42.

- Grange S, Schmitt C, Banken L, et al. Thorough QT/QTc study of tocilizumab after single-dose administration at therapeutic and supratherapeutic doses in healthy subjects. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;49(11):648–655.

- Kewan T, Covut F, Al–Jaghbeer MJ, et al. Tocilizumab for treatment of patients with severe COVID–19: A retrospective cohort study. EClinicalMedicine. Published online 2020 June;24:100418.

- Cavalli G, De Luca G, Campochiaro C, et al. Interleukin-1 blockade with high-dose anakinra in patients with COVID-19, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and hyperinflammation: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020;2(6):e325–e331.

- De Luca G, Cavalli G, Campochiaro C, et al. GM-CSF blockade with mavrilimumab in severe COVID-19 pneumonia and systemic hyperinflammation: a single-centre, prospective cohort study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020;2(8):e465–e473.

- Roche. Roche’s phase III EMPACTA study showed Actemra/RoActemra reduced the likelihood of needing mechanical ventilation in hospitalised patients with COVID-19 associated pneumonia. [ Published 2020 Sep 18; cited 2020 Oct 7]. Available from: https://www.roche.com/media/releases/med-cor-2020-09-18.htm