?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

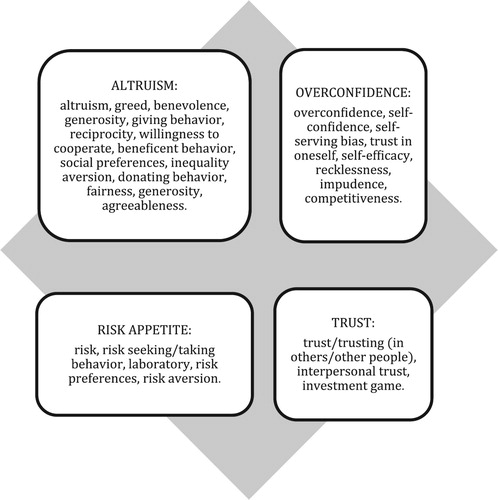

This study provides a critical review of the behavioral economics literature on gender differences using key feminist concepts, including roles, stereotypes, identities, beliefs, context factors, and the interaction of men’s and women’s behaviors in mixed-gender settings. It assesses both statistical significance and economic significance of the reported behavioral differences. The analysis focuses on agentic behavioral attitudes (risk appetite and overconfidence; often stereotyped as masculine) and communal behavioral attitudes (altruism and trust; commonly stereotyped as feminine). The study shows that the empirical results of size effects are mixed and that in addition to gender differences, large intra-gender differences (differences among men and differences among women) exist. The paper finds that few studies report statistically significant as well as sizeable differences – often, but not always, with gender differences in the expected direction. Many studies have not sufficiently taken account of various social, cultural, and ideological drivers behind gender differences in behavior.

INTRODUCTION

Behavioral economics and its focus on the interrelations between economics and psychology is attracting increasing attention (Sent Citation2004). Many dimensions of behavior in economic and noneconomic settings are being explored, often examining how “pure rationality” does not sufficiently explain behavior. Some behavioral economics investigations are of gender differences. The 2007–08 financial crisis has raised interest in such studies, for example, in relation to the Lehman Sisters Hypothesis, which proposes that the financial crisis could have been avoided had women been in charge of the financial sector (van Staveren Citation2014). This review article provides a critical overview of 208 recent contributions to the behavioral economics literature, examining the reported gender differences in behavior from a feminist perspective.

As we will show, results on gender differences in communal behaviors (often stereotyped as feminine) and agentic behaviors (often stereotyped as masculine) are mixed and vary considerably in different social contexts and with various framing effects. Furthermore, gender differences in behavior do not necessarily reflect innate differences but may instead be due to a third variable, for example, societal pressure to conform to prescribed gender roles or to a position in a social power hierarchy (Nelson Citation2014). Such variables are often not accounted for in experimental studies.

Many experimental studies do not report statistically significant gender differences. When statistically significant gender differences are found, there is often little explanation of the differences, despite an increasing recognition of contextual variables in behavioral economics. It may not be clear what the substantive significance of the gender difference is (is the size effect big enough to have an economic impact?) and what possible policy implications would be (if the average behavior puts women or men at a disadvantage, what could be done about it?). Answers to policy-relevant questions could be enhanced by feminist interpretations of the results, and, more fundamentally, experimental designs informed by feminist economics. Because only when a study is designed to allow for measuring size effects does an answer to the first question become possible. And only when a study is designed to disentangle possible causes of gender differences will an answer to the second question come within reach. We will focus on feminist interpretations of results, while also referring to oft-neglected, but crucial, experimental design effects. We were able to calculate size effects on gender differences for eighty-one studies from the 208 articles that provided sufficient statistical information to calculate size effects. We found that many of these studies are weak in interpreting size effects, limited in explaining the causes contributing to the results, and lacking in convincing suggestions for policy measures to address differences that matter in economic life.

Although we recognize an increasing awareness of context in such studies, these weaknesses are problematic for two reasons, as Julie A. Nelson (Citation2014) has explained. First, reporting gender differences has become interesting in itself, and simple reporting without adequate statistical assessment of both statistical significance and size effects leads to confirmation bias and publication bias in behavioral research (Croson and Gneezy Citation2009; Nelson Citation2014, Citation2015, Citation2016). That is, journals are possibly more likely to publish articles that find significant differences between the sexes than articles that find no differences. As a result, researchers are possibly more likely to try to find gender differences than similarities. This is closely connected to a reporting bias, according to Paolo Crosetto, Antonio Filippin, and Janna Heider (Citation2013). Second, lack of attention to size effects, context, causal mechanisms, and interaction effects between male and female subjects gives way to essentialist interpretations of the gender differences found, reinforcing gender stereotypes rather than questioning them. Essentialism in the behavioral literature either takes an explicit form (“women are found to be … ”) or an implicit form (through assuming that men and women make free choices based on their respective innate characteristics). From her analysis of behavioral studies on gender and risk, Nelson concludes:

The economics literature on gender and risk aversion reveals considerable evidence of “essentialist” prior beliefs, stereotyping, publication bias, and confirmation bias. The claims made about gender and risk have gone far beyond what can be justified by the actual quantitative magnitudes of detectable differences and similarities that appear in the data. (2014: 227)

These four dimensions may overlap. Since it is not the intention of this paper to provide unambiguous descriptions of each dimension, they are not narrowly defined and consequently may have some common characteristics. Instead, each dimension is discussed in the context of the available literature, thereby retaining its complexities.

Gender differences in risk appetite are examined in the behavioral economics literature using field data, surveys, and experiments.Footnote2 It is not always clear in empirical studies whether risk appetite refers to a situation of probabilities (risk) or to a situation of the unknowable (uncertainty). Overconfidence is an unwarranted belief in the correctness of one’s answers and can result from a tendency to neglect contradicting evidence (Koriat, Lichtenstein, and Fischhoff Citation1980). Related is a concept called “self-serving bias” (Babcock and Loewenstein Citation1997), which is a difference in views on what is considered “fair” in, for example, a bargaining situation. Overconfidence is furthermore related to a biased attribution of failures to one’s surroundings or coincidence and the attribution of successes to one’s own competence. Ultimately, overconfidence pertains to one’s perception relative to the actual situation. Altruism is a social attitude that is modeled by including the utility of others in an individual’s own utility function, or as a commitment to a social value. In the behavioral economics literature, altruism is mainly inferred from giving behavior in dictator games. Trust, as an other-regarding social attitude that defines the willingness to make oneself dependent on – or believe in – the capabilities or cooperation of an (unknown) other person, constitutes both a social component of a general orientation toward others and a component of calculated risk taking. As a consequence, trust is not only related to risk preferences but also to trustworthiness.

REVIEW OF RELEVANT LITERATURE

Feminist economics has developed a rich critique of the standard behavioral assumptions in mainstream economics. Feminist economics and behavioral economics both reject the assumption that economic agency is fully driven by Rational Economic Man. But whereas the behavioral literature relies on psychology for its theorization, feminist economics combines a wider set of interdisciplinary sources for its critique and for developing an expanded model of economic agency. Feminist economists reject the dichotomous conceptualization of rationality as excluding emotion, as situated in the public spheres of markets and governance structures, and as individualistic and self-interested (Ferber and Nelson Citation1993, Citation2003; Nelson Citation1996; Folbre Citation2001; van Staveren Citation2001). Instead, agency is recognized as having a wide variety of conscious and unconscious motivations, being a mix between self-oriented and other-oriented, and having both calculative and emotional drives. More importantly, agency is regarded as not entirely separate from the context in which decisions are being made. Feminist economists, therefore, pay much attention to social structures such as power relations and institutions, as well as dominant discourses and specific social settings in relation to resources, exchange, and redistribution (see Figart and Warnecke [Citation2013]).

Feminist economic research acknowledges the role of asymmetric institutions that work out differently for men as a group as compared to women as a group, recognizing that such gendered institutions tend, on average, to benefit men (Folbre Citation1994; van Staveren Citation2013). Men’s agency is likely to include not only an individual benefit from gendered institutions that favor men over women, but also actions that protect and sustain gendered institutions that work to their benefit. Such institutions interact with agency through the internalization of gender norms through men’s and women’s respective socialization. A concept such as preferences cannot be regarded in economic analysis as exogenous but as, at least partly, socially constructed. The points of gravity of such socialization in the case of men and women as a group are the two stereotypical gender roles of agentic and communal behavior. In other words, gendered institutions are not only constraints on behavior but also affect agency itself through attitudes and decisions in a stereotypical way, affirming communal behavior by women and agentic behavior by men. This has economic impacts on the access to and control over resources, the number and quality of options to choose from, the hours worked for pay and rewards gained from labor and assets, and, finally, the level of well-being for individual women and men and their dependents. Therefore, the economic behavior of men and women cannot be interpreted in terms of a rational choice based on given preferences.

Moreover, following John Maynard Keynes (Citation1936), feminist economists recognize the role of expectations in behavior. Expectations about the behavior of one’s future self and of other economic agents may suffer from gender biases (Eckel and Grossman Citation2002). Such gender beliefs may affect self-esteem, confidence, trust, risk-taking, and cooperation. Gender beliefs therefore may color the choices that men and women make when interacting in single-sex settings – as in all-male company boards or in many childcare practices – as well as when interacting in mixed-sex settings – such as in the bargaining behavior in heterosexual households or in hiring and promotions in labor markets.

Feminist economics research on behavior adds two insights to psychology: (1) the relatedness of agency and economic context, through the socialization effect of institutions and endogenous preferences, and (2) attention to expectations about behavior that may be gender biased, through gender beliefs. Our starting-point is the analytical framework developed by two social psychologists and management scholars, Alice Eagly and Wendy Wood. We will take their biosocial constructionist framework (for an extended version, see Wood and Eagly [Citation2012]), and we will integrate feminist economics insights to provide a more complete feminist analytical framework for the analysis of behavioral economic literature on gender differences. The behavioral economic literature is almost exclusively carried out in developed countries, with a bias toward the United States – an important context variable to be taken into account in our review.

The biosocial constructionist framework starts with the important distinction between vertical and horizontal gendered processes. The vertical dynamic explains the globally common, but varied, gender division of labor from biological differences that historically mattered: men’s strength and women’s reproduction. The influence they asserted on a gender division of labor became important as soon as agriculture and individual property emerged (Dyble et al. Citation2015). This led to clear distinctions between a public and a private sphere, between production and consumption, and between owners and those dependent upon the resources of owners. This gender division of labor has varied over time, between societies, and in relation to the natural environment.

The horizontal dynamic is more relevant for understanding behavioral differences between men and women today. It starts from the gender division of labor that resulted from the vertical dynamic and the gender roles that followed. Gender roles are “the shared beliefs that members of a society hold about women and men” (Wood and Eagly Citation2012: 70). In feminist economics, however, gender roles and gender beliefs are not the same. Roles concern behavior, both descriptively (what men and women do) and normatively (what men should do and what women should do). Beliefs, however, are expectations about the behavior of one’s own sex and the other sex, that is, the extent to which we believe that “real men” or “real women” (should) behave in certain ways. This distinction is important for economic analysis because expectations influence economic decisions. In an experimental study, we tested for gender beliefs in a cooperation game (Vyrastekova, Sent, and van Staveren Citation2015). We found that, on average, men believe women to be more cooperative than men, which led them to contribute statistically significantly, as well as substantially, more when playing against women. To the contrary, we did not find any statistically significant or sizeable difference in the average gender beliefs held by women. Our distinction between gender beliefs (expectations about cooperation by men and women) and actual cooperative behavior in the game (amount of money contributed to the common pot by men and women) allowed us to interpret our findings of the, on average, more cooperative behavior of women as driven by men’s asymmetric gender beliefs and not by naturally more generous behavior of women.

Gender roles include stereotypes. Women are generally valued for their communal tasks in patriarchal societies, reinforced by symbols linking communion and femininity, for example, around the family. This positive valuation becomes a system-justifying force, where women receive moral rewards for their communal roles. Importantly, agentic and communal behavior are not dichotomous categories when it comes to the actual behavior of men and women. Carothers and Reis (Citation2013) have examined whether the latent structure of constructs of psychological gender differences is “dimensional” (that is, a matter of degree; continuous) or “taxonic” (that is, sorted into distinct categories; categorical). They did so by looking at variables such as science inclination and fear of success. Almost all psychological variables are continuous dimensions rather than taxonic, whereas anthropomorphic variables (weight, height) are generally taxonic variables. As a consequence, essentialist interpretations of gender differences are likely to be inappropriate and not representing rigorous science.

The next element in the biosocial constructionist framework is gender identity, or the internalization of gender roles. “People therefore do gender as they recurrently produce social behaviors stereotypical of their sex” (Wood and Eagly Citation2012: 77). Feminist economists have analyzed this phenomenon in the context of household bargaining. A key study uses data from the United States and Australia and finds that women reduce their share of housework only until they earn as much as their male partners (Hochschild and Machung Citation1989). As soon as they earn more, they begin to do more housework. “As things move to greater male economic dependency where men are not enacting masculinity through providing money, women pick up more of the housework – as if to neutralize the man’s deviance” (Bittman et al. Citation2003: 203). Without research into the link between resources and stereotypical gender roles, such findings could lead to essentialist interpretations, such as a natural inclination to help men in housework when women feel economically empowered.

Although the biosocial constructionist framework recognizes doing gender (Wood and Eagly Citation2012), it misses the nonlinear relationship with resources and an explicit account of the structural support of gender roles through asymmetric institutions, which generally benefit men over women. In economics, it is crucial to take gendered institutions into account because they affect access to and control over resources, the distribution of costs and benefits of activities and money, and decision-making power.

The final element in the biosocial constructionist framework is the two-way relationship between behavior and biological processes (Wood and Eagly Citation2012). This is not in terms of an evolutionary view of “hard-wired brains” of men as hunters and women as caregivers, but rather the flexible biological processes that interact with cognitive and emotional states. These biological processes concern hormones, neural systems, and cardiovascular responses. Agentic behavior is often seen as related to testosterone and cortisol, which, on average, are more present (testosterone) or stay longer at higher levels (cortisol) in men’s bodies. Communal behavior is seen to be related to oxytocin and estrogen, which are found in higher quantities or are released faster in women’s bodies. But the relationship between stereotypical gender roles and hormones are not straightforward. For example, communal roles can be stressful, while agentic roles can be in a social setting with shared feelings of affection. Research indicates that the connections made in studies between hormones and men or women reflect the very stereotypes of masculinity and femininity that should be questioned in rigorous behavioral studies (Fine Citation2017).

Finally, the relationship of hormones with behavior is two-directional, as Wood and Eagly (Citation2012) emphasize. First, gender roles tend to affect hormonal levels. For example, nurturing has been found to reduce testosterone levels in both men and women (Booth et al. Citation2006). Financial trading in highly volatile markets has been found to increase levels of cortisol in male traders (Coates and Herbert Citation2008). Second, hormones affect behavior. For example, administering testosterone to women influences outcomes in bargaining games (Eisenegger et al. Citation2010; van Honk et al. Citation2012) and administering oxytocin to men influences outcomes in public good games (Israel et al. Citation2012). However, much of the research on testosterone and economic behavior (in particular, risk-taking) shows mixed results, which vary depending on birth-levels of testosterone, endogenous or administered testosterone, adaptation to context, and interaction with other hormonal processes (Apicella, Carré, and Dreber Citation2015).

Flexible biological processes, such as hormone levels, do not imply hard-wired differences between men and women, but rather help us to understand how, under certain conditions, social and biological processes may reinforce men’s agentic behavior and women’s communal behavior. Hence, we must be very careful with essentialist interpretations:

By this confluence of biological and social processes, the sexes organize behavior into patterns that are tailored to the conditions that vary across time, cultures, and situations. Thus, humans evolved a psychology that on the one hand allows considerable flexibility in behavior between societies but on the other hand stably structures culturally shared beliefs to make the typical activities of men and women within a society seem natural and inevitable. (Eagly and Wood Citation2011: 765)

METHODOLOGY

Research strategy

For this study, we used keywords to find published articles with Google Scholar, Research Papers in Economics (RePEc), and ScienceDirect for the years 2004–13. In addition, we browsed scholarly databases (such as IDEAS and RePEc) for working papers from 2009 to 2013, and we browsed recent publications in relevant journals for the period 2004–13. Finally, we read articles to find important contributions that would otherwise be missed (these include oft-quoted articles published before 2004). Figure shows the keywords we used in our search strategy.

Our methodology assumes that the authors of the studies have a minimally shared understanding of each behavioral attitude, its features, and how it is best measured. This is an optimistic assumption, but since many studies are not explicit, we have used the four general categories. This implies, for example, that some studies that refer to risk may use it in a narrow sense, limited to financial risk, whereas others studies that refer to trust may use it in a broad sense, such as trust in people in general. Moreover, we have tried to do our best to capture key publications, but we might have missed some. Finally, there may not always be a shared understanding among readers as to what is a more economic study as compared to a more sociological, psychological, or other type of behavioral study. These methodological weaknesses, and any others, need to be taken into account.

Technical details of substantive differences tests

Cohen’s d is one of the most common ways to measure effect size. It describes how different two groups are on average, scaled to interpret a given nominal difference as “smaller” when there is a lot of variation among people in the full population. For example, the age of first marriage varies far more than the age of losing the first baby tooth, so a one-month between-group difference in the former is “smaller” as measured by Cohen’s d. The Index of Similarity (IS) is an easily computable and understandable measure of the degree of overlap between two distributions.

Cohen’s d

Consider an experiment that is split for two groups of participants: group 1 has sample size , observed mean

, and observed standard deviation

; and, similarly, group 2 has sample size

, observed mean

, and observed standard deviation

.

The Cohen’s d effect size is formally defined by Jacob Cohen (Citation1988) as the fraction:

Where

is the mean of group

, and

is the pooled standard deviation, calculated as:

By definition, the pooled standard deviation is the square root of the weighted average of the variances of the two groups (as the pooled variance is the weighted average of the variances of the two groups) By dividing the difference between the means of the two groups by the pooled standard deviation, the computed standardized measure provides the possibility to compare results across studies. Since the pooled standard deviation is always strictly positive

– unless the two groups consist of participants all making the exact same decisions, which practically does not occur – the resulting

-statistic can easily be interpreted by its sign: For

, the average of group 1 exceeds the average of group 2 (since

). For

, the average of group 2 exceeds the average of group 1 (since

). For

, the averages of the two groups coincide perfectly

.

The absolute size of Cohen’s d indicates the substantiveness of the difference between the means of the two groups in the context of the corresponding experiment: as , increases, the substantiveness of the difference increases. This logically means that an increase in the size of the difference of the sample means

or an increase in the clustering of results for each group closer to their respective means

leads to a more substantive difference between the means of the groups. The Cohen’s d effect size purely describes the standardized difference between the means of the groups: a Cohen’s d equal to 0 does not imply that the two groups are exactly equal in distribution, but merely that their means coincide. Unless the

effect size blows up in size, one can expect that the two experimental groups have some degree of overlap in their distributions. Consistently differing means (in a certain direction) would point to two groups actually differing on average, whereas inconsistent results would give us reason to believe outliers or context-related reasons cause the observed results of certain studies.

As Cohen’s is in essence an effect size, the “significance” we mention for our results throughout the article refers to how substantial the difference between the measured means is and thus does not fully equate to statistical significance. An article might report that the results indicate an insignificant difference between men and women, yet this does not imply that

(it rather implies that

will be in the neighborhood of 0).

In the rest of the article, group 1 refers to the group of men , and group 2 refers to the group of women

.

Index of similarity

Where Cohen’s serves as an indicator for the significance of the difference between the means of two groups (and would provide a theoretical indication of overlap of probability distributions in the absence of skewness and kurtosis, which is practically often not the case), the actually observed difference of the distribution of values between the two groups is not captured by this statistic. To counter this, wherever applicable, the Index of Similarity (IS) is computed complementary to the Cohen’s d, quantifying the degree of overlap of the two groups’ distributions of values. Assuming that the distribution of values is discrete (noncontinuous), the IS looks at the distribution of the values of group 1 over the different categories relative to the distribution of the values of group 2 (Nelson Citation2015).

Formally, the IS is calculated as:

With

number of categories subjects can be placed into,

the sample size of group

, and

the number of people from group

falling into category

. The IS is much like the Dissimilarity Index (White Citation1986). Mathematically, their relation is:

It factually looks at the ratio of subjects from group 1 falling into a category, minus the percentage of subjects from group 2 falling into that same category (in absolute values, summed over the categories). To avoid counting these values twice, as the sum of differences does by definition (counting subjects falling in a certain category, as well as the subjects not falling in this category), the sum is divided by two.

When , not a single subject of group 1 falls into the same category as any of the subjects from group 2 (their distributions are disjoint), and when

, the distributions of group 1 and group 2 are exactly the same. The IS provides a favorable indication of actual detailed differences between groups, but requires more information than the computation of Cohen’s d does, as the distribution of values for both groups needs to be precisely known or given by the researcher (which is not often the case for the articles included in our collection).

REVIEW OF BEHAVIORAL ECONOMIC STUDIES OF GENDER DIFFERENCES

We have reviewed 208 behavioral studies of risk appetite, overconfidence, altruism, and trust. In the Supplemental Online Appendix, for each study, we indicate the empirical method used, the kind of gender difference analyzed, and whether the stereotypical gender difference was found. The Supplemental Online Appendix also provides information about the games used in the experiments in our study.

In Tables –, we show a subset for each behavioral dimension for which we were able to calculate the size effect of the gender differences found in the studies. We have attempted to calculate both the Cohen’s d effect size and the IS for each article and for each in-article study. To assess the economic significance of gender differences, we follow commonly used cutoff points. In the literature, a of

or larger indicates a difference of medium size (Cohen Citation1988), which we will follow. Under the assumption that there is no difference between the sexes in the underlying population, the D tends to 0. As Michael R. Ransom (Citation2000) found, the variance of the D decreases rapidly when the sample size increases, with the mean value equal to 0. Since the IS is directly related to the D by

, the structure of the sampling distribution of IS can be taken equal to D, with mean value of 1 and the distribution mirrored about 0.5. Following Ransom, we take the cutoff value of the IS to be 0.75.

Table 1 Risk appetite

Table 2 Overconfidence

Table 3 Altruism

Table 4 Trust

As the number of in-article studies and experiments can be high (up to sixteen in a single article), the tables show the range of effect sizes or statistics. This fits within the conclusion of variability that we draw and fits in the presentation of this paper. We understand that information can be lost this way, so we offer a complete table in the Supplemental Online Appendix.

Risk appetite

Differences in attitudes toward risk or behavior under risk are the most widely studied of the four behavioral dimensions. Most studies include monetary incentives so that participants are probably more inclined to reveal behavior that accurately reflects true preferences under risk or risk valuations (see, for example, Fehr-Duda et al. [Citation2011]). The overall findings of risk-taking behavior of men and women are mixed (Nelson Citation2015; Filippin and Crosetto Citation2016). Nevertheless, the general belief is that women are more risk averse than men. Only one study finds women to be less risk averse than men in a particular context but does not provide the statistics to calculate effect sizes and therefore does not appear in our table (Charness and Genicot Citation2009).

A widely used approach to measuring attitudes toward risk is to ask participants to provide a selling price for a specific gamble (the “HL method”; Becker, Degroot, and Marschak Citation1964). This involves a lottery game with actual winnings wherein participants can choose either a riskier or safer lottery ticket. When payoffs increase in variance, risk attitudes of participants change (Holt and Laury Citation2002). Antonio Filippin and Paolo Crosetto (Citation2016) collected micro data of sixty-two HL-method studies. They conclude that “significant gender differences [are] the exception rather than the rule” (Filippin and Crosetto Citation2016: 19). Moreover, they increased the statistical power by combining comparable data and conclude that the results are statistically significant but economically irrelevant. The gender gap correlates with features of the risk elicitation method (the availability of a safe option and/or fixed probabilities), and it reflects the method used to elicit preferences rather than differences in underlying risk attitudes of subjects.

Most studies on risk behavior and attitudes in the economic literature focus on financial decision making. There are also studies that use survey data to examine whether financial literacy influences risk taking (Beckmann and Menkhoff Citation2008; Wang Citation2009) or field data on investments in retirement plans (Sundén and Surette Citation1998; Agnew, Balduzzi, and Sundén Citation2003).

With regard to biological influences of behavior, one study finds a positive correlation between testosterone levels and risk taking in an investment game (Apicella et al. Citation2008). Furthermore, associations with masculinity revealed by scores on Bem’s sex role inventory are found to be positively correlated to risk-taking behavior (Bem Citation1974; Meier-Pesti and Penz Citation2008). Risk attitudes are dependent on changes in payoff variances (Holt and Laury Citation2002). Hence, risk attitudes cannot be regarded as a stable personality trait. Cadsby and Maynes (Citation2005) find women tend to follow the behavior of other group members, making risk attitudes dependent on the attitudes and behavior of other people. Helga Fehr-Duda et al. (Citation2011) find that preexisting moods have more impact on the probability weighting of risky prospects for women than for men. Several studies conclude that contextual differences and familiarity with the subject have a significant impact on risk behavior (Powell and Ansic Citation1997; Schubert et al. Citation1999; Agnew et al. Citation2008; Eckel and Grossman Citation2008; Carr and Steele Citation2010).

Nelson (Citation2015) has computed Cohen’s d and the IS for thirty-five articles that examine risk-taking behavior and gender.Footnote3 She found that, overall, gender differences in risk aversion in the thirty-five articles are small, and the overlap between the distribution of men and women is considerable, exceeding 80 percent.

Table shows the statistics for the size effects for gender differences in risk appetite for twenty studies. In thirteen studies, women are found to show, on average, more risk aversion, and in seven studies, the results are mixed or not statistically significant. Out of these twenty cases, six articles return a size effect or range of size effects for Cohen’s d fully above 0.5, implying that for 30 percent of the articles, the men’s mean for risk appetite lies considerably higher than the women’s mean. The IS could be calculated for only three articles, and in two of these cases we found the distribution for men and women to differ significantly. Many articles returned a considerable range of Cohen’s d statistics, such as Meier-Pesti and Penz (Citation2008) with -effect sizes ranging from 0.09 to 0.85, Carr and Steele (Citation2010) with effect sizes ranging from −0.13 to 0.95, and Schubert et al. (Citation1999) returning statistics from −0.52 to 0.47. Other articles returned only very small effect sizes, near and on both sides of 0.

Overconfidence

Results concerning overconfidence are mixed, as some studies find that men are more overconfident than women, while others find no gender difference. The experiments measure overconfidence in different settings. Hence, the mixed results imply that men are more overconfident only in some situations, although there could still be significant economic consequences. None of the studies finds evidence for larger overconfidence, on average, among women. Since it can reasonably be assumed that (over)confident people are more likely to engage in competition than less (over)confident people, shying away from competition might give an indication of low confidence in one’s own performance. Overconfidence is revealed by the choice for a specific reward style in which an element of competition is or is not present (Datta Gupta, Poulsen, and Villeval Citation2005; Niederle and Vesterlund Citation2007; Vandegrift and Yavas Citation2009). There is not a clear distinction in the literature between (over)confidence and competitiveness, though there is a link between the two in the sense that (over)confidence tends to lead to high expectations of winning in a competitive setting. This is influenced by gender norms, gender-based discrimination in access to and control over resources, and gender beliefs on proper attitudes toward competition.Footnote4

Some researchers have examined the role of socialization in gender differences in competition. For instance, Uri Gneezy, Kenneth L. Leonard, and John A. List (Citation2009) compare subjects from a patriarchal society (Maasai in Tanzania) and a matrilineal society (Khasi in India). While women from the patriarchal society show, on average, less competitive behavior than men, on average, the effect is reversed in the matrilineal society. Moreover, in both societies, there is no gender difference in risk preference. The results seem to indicate that socialization affects competitive behavior.

Experiments concerning overconfidence include financial trading activity (Barber and Odean Citation2001) and the valuation of one’s performance on an exam (Lundeberg, Fox, and Punćcohaŕ Citation1994; Bengtsson, Persson, and Willenhag Citation2005; Dahlbom et al. Citation2011) and in quizzes (Beyer Citation1990; Pulford and Colman Citation1997). Some studies analyze surveys on behaviors toward risk and dealing with risk (Beckmann and Menkhoff Citation2008) and others use field data. Lena Nekby Peter Skogman Thoursie, and Lars Vahtrik (Citation2008), for example, use data from a running match in which people self-select into start groups based on individual assessments of running times. These indicate an expectation of performance that the authors consequently compare with actual performance.

There is no single dominating experimental design, and there are different manifestations of overconfidence (better-than-average effect, illusion of control, and miscalibration), which are not necessarily correlated (Beckmann and Menkhoff Citation2008). In this article, there is not enough space to discuss these different measures. Furthermore, as already stressed by Croson and Gneezy (Citation2009), experimental design may affect men’s behavior and women’s behavior in different ways.

Table shows the size effects of gender differences in overconfidence. Of the twenty-eight cases, only Donald Vandegrift and Abdullah Yavas (Citation2009) and Uri Gneezy, Muriel Niederle, and Aldo Rustichini (Citation2003) return effect sizes indicating a sizeable difference, namely and

, respectively. Some of the articles, such as Alison L. Booth and Patrick Nolen (Citation2012) and Mary A. Lundeberg, Paul W. Fox, and Judith Punćcohaŕ (Citation1994), return ranges that might indicate a difference, but most studies return either very mixed results or only small gender differences. We do find the

statistic more often than not to be larger than 0, indicating that men might (on average) be slightly more inclined to show overconfident behavior than women. For thirteen of the twenty-eight articles, the IS could be calculated. Of these thirteen articles, only four return a (set of) statistic(s) indicating a significant difference between the distribution of men and women.

Altruism

Prosocial attitudes are reflected by the positive valuation of others for one’s well-being or values. In the economics literature, altruism is often related to pure altruism, envy, aversion to inequality, and reciprocity (Croson and Gneezy Citation2009). In experimental contexts, altruism is revealed mainly by giving behavior in games or real-life contexts such as blood donation. The dictator game is the most used experimental design in the studies examined below.

Various researchers have analyzed the sensitivity of the findings concerning altruism to the experimental design. For instance, Colin F. Camerer (Citation2011) suggests that behavior in dictator games is not always due to pure altruism, but the result of the willingness to conform to a specific social norm (for example, to share unearned income appropriately; also see Bolton, Katok, and Zwick [Citation1998]). Feminist economists are also interested in self-signaling and social image concern. James Andreoni and B. Douglas Bernheim (Citation2009) find that previously unexplained behavioral patterns in altruistic behavior are due to people wanting to be perceived as fair (also see Ariely, Bracha, and Meier [Citation2009]; DellaVigna, List, and Malmendier [Citation2012]).

Yet, according to Rachel Croson and Uri Gneezy (Citation2009) the design of dictator games allows for a better isolation of altruistic motives than the design of ultimatum games. In ultimatum games, risk aversion might also play a role. Other experiments include public goods games (Cadsby et al. Citation2007) and surveys in which people indicate their willingness to donate (Straume and Odèen Citation2010). Although results are mixed, there is some consensus that women, on average, seem more inclined to behave out of altruistic motives than men, on average. For example, one study found that the amount of blood donated by women is negatively correlated with the monetary reward for such a donation, while men’s blood donations were, on average, not affected by monetary rewards (Mellström and Johannesson Citation2008). This might suggest that women, on average, donate blood out of intrinsic motivations more than men, but this could be due to socialization of women into communal roles and identities. Conversely, other studies find that men tend to behave, on average, more altruistically than women do, on average. These results are limited, however, to specific experiment designs (for example, Ben-Ner, Kong, and Putterman [Citation2004]) or sample sizes (for example, Anderson, DiTraglia, and Gerlach [Citation2011]) and generally do not take context such as stereotype gender roles and gendered identities into account.

James Andreoni and Lise Vesterlund (Citation2001) find that altruistic behavior is affected by the costs of altruism in terms of the relation of one’s own payoff to the other’s payoff. When altruism comes at low costs, men are found, on average, to behave more altruistically than women, on average. At high costs however, women are observed, on average, to behave more altruistically than men on average. In their overview of gender differences in preferences, Croson and Gneezy (Citation2009) stress that differences in experiment design can have a different impact on men and women. The finding of Andreoni and Vesterlund (Citation2001) indicates that the experiment design (in this case, the specification of the costs of altruism) actually affects the average outcomes for men and women. Hence, differences in access to and control over resources – a key insight from feminist economics – matter.

The overall results on gender differences in altruistic behavior are mixed. Some studies find no gender differences (Albert et al. Citation2007), while others point at large intra-gender differences (that is, differences among men on the one hand and differences among women on the other hand; Castillo and Cross Citation2008; DellaVigna et al. Citation2013). Finally, Linda Kamas, Anne Preston, and Sandy Baum (Citation2008) examine decision making in groups. While they find that individually women give more than men, in paired settings, mixed groups give the most (followed by all-women and all-men groups). This suggests that the presence of women in male-dominated environments can result in more average altruistic group behavior, pointing at interaction effects between men and women based on gender beliefs held by each sex.

Table shows the statistics for the size effects of the twenty-two studies of gender differences in altruism. None of the articles returns a significant Cohen’s d, or range of , in either direction, implying that the difference in men’s and women’s means is rather small. Many articles show ranges passing the 0 border, implying that whatever difference there might be, it can be in both directions. The IS could be calculated for eleven of the twenty-two articles, and indicated a sizeable difference in male and female distributions in five cases. Again, we find the results to vary greatly, leading us to believe that men and women tend to exhibit altruism at similar levels.

Trust

Several studies associate trust with institutional efficiency and economic growth (see Bonein and Serra [2009] for an overview). Experiments studying trust oftentimes use a so-called BDM design (Berg, Dickhaut, and McCabe Citation1995), in which a trustor decides how much of her/his initial endowment is sent to an anonymous trustee. The experiment organizer then triples the amount given to the trustee. The trustee subsequently decides how much money to send back to the trustor and how much to keep.

Trusting another (unknown) person can be thought of as placing a risky bet on that person’s trustworthiness. Trusting therefore has an element of calculated risk taking (Eckel and Wilson Citation2004), but it can also be regarded as a social virtue (see Fukuyama [Citation1995]; Chaudhuri and Gangadharan [Citation2007]). Although the overall results are mixed, in most of the studies, men are found, on average, to show more trusting behavior than women, on average. Only one recent study finds women, on average, to show more trusting behavior (Etang, Fielding, and Knowles Citation2011).

The unique Nash equilibrium of the BDM game is a corner solution: the trustor sends nothing. However, in many experiments both players do send money, indicating expressions of trust and trustworthiness. Sending money can be explained by the presence of positive affections, such as goodwill (Scharlemann et al. Citation2001), social distance between the trustor and trustee (Glaeser et al. Citation2000), positive social history in trust situations (Berg, Dickhaut, and McCabe Citation1995), and individual personality traits (Evans and Revelle Citation2008).

Many studies on trust behavior conduct a modified BDM experiment. Andreas Ortmann, John Fitzgerald, and Carl Boeing (Citation2000) modify the way participants receive information on the amount sent by previous players. They conclude that the findings of the original BDM game are robust. Other modifications are, for example, ensuring that participants are not anonymous (Bonein and Serra Citation2009), enabling the possibility of partner selection (Slonim and Guillen Citation2010), and examining the effect of differences in social distance (Buchan, Johnson, and Croson Citation2006).

Trust behavior can also be measured by online surveys on the propensity to trust (Evans and Revelle Citation2008). Mary Rigdon (Citation2009) examines how the body responds to a signal of distrust. When a signal of distrust is received, men – but not women – show, on average, an increased level of a testosterone-like hormone.

Laura Schechter (Citation2007) finds that players’ behavior in traditional trust games is related to risk preferences. This complicates the identification of gender differences in trust behavior as risk aversion plays an important role in behavior in the traditional BDM trust game. A gender difference in trusting behavior may therefore be due to differences in risk aversion. James C. Cox (Citation2004) suggests using multi-game designs to better isolate trust from other-regarding preferences. Furthermore, it is important to differentiate trust that others will return the money you sent from trust in the capabilities of others. Christiane Schwieren and Matthias Sutter (Citation2008) find strong gender differences for trust in ability; on average, men place more trust in the abilities of other people (especially of women) than women do. Andreoni and Vesterlund (Citation2001) find that, on average, men’s behavior in bargaining games is more sensitive to the costs of altruism than women’s behavior. In their conclusion, Schwieren and Sutter (Citation2008) note that the relation between gender and trust is not straightforward and perhaps too complex to be analyzed by means of the BDM game alone.

Table shows the statistics for the size effects of the studies that pertain to gender differences in trust. Many of the statistics are positive, indicating a somewhat higher mean level of trust for men. But out of the eleven studies looking into gender differences in trust games, none returns a Cohen’s d effect size, or range, that lies purely in the medium- or higher-sized range. We could calculate the IS for only one of the twelve articles, namely Ananish Chaudhuri and Lata Gangadharan (Citation2007), with , indicating a substantive difference in the distributions of men and women. However, one article can hardly represent the other twelve, and considering the mixed or low-valued Cohen’s d effect sizes, we note that there is seemingly no substantive average gender difference when it comes to trust behavior.

Comparison of results

After a reexamination of experiments that measure the risk appetite of men and women, gender differences seem to be small compared to the intra-gender differences, and a large overlap in distributions exist. Studies have large differences in contextual framing, making findings only partially comparable. In addition, Eckel and Grossman (Citation2008) find that laboratory experiments in contextual settings show less consistent results than more abstract experimental studies. This may point to the influence of gendered context factors such as socialization, beliefs, institutions, and stereotypes. Other studies find that large intra-gender differences and familiarity with the subject have a large impact on the outcomes of experiments (for example, Agnew et al. [Citation2008]).

Results on gender differences in overconfidence are also mixed, but a review of the literature reveals that the suggestion that women show, on average, less overconfident behavior than men do, on average, is more pronounced. Some studies relate women’s lower levels of overconfidence to a “shying away from competition” effect. Men, on average, seem more likely to select reward styles in which they have to compete for their earnings than women who, on average, seem more likely to follow piece-rate compensation strategies (see Datta Gupta, Poulsen, and Villeval [Citation2005]; Niederle and Vesterlund [Citation2007]; Vandegrift and Yavas [Citation2009]). But without controlling for socialization in a patriarchal context, such interpretations are unreliable.

Overall, results on altruism are mixed and results point both ways. In addition, some studies point out that there are large intra-gender differences and therefore it is not possible, and in fact not acceptable, to generalize altruism in behavior based on gender. Altruistic behavior is affected by the costs of altruism, and this may hold more, on average, for men than for women (Andreoni and Vesterlund Citation2001). These results may be important for research around unpaid caring and the worldwide unequal distribution of care work between women and men – a theme well researched in feminist economics. It also points at possible differences in financial versus nonfinancial altruism and at a universal context of women earning, on average, lower incomes than men. Without such gendered context variables, any interpretation of gender differences in altruistic behavior is rather meaningless.

Finally, behavioral economics findings on gender differences in trust behavior are also mixed, and there is seemingly no substantive gender difference when it comes to trust. Moreover, in some cases, the same experiment has led to contrasting findings (see Croson and Buchan [Citation1999]; Buchan, Croson, and Solnick [Citation2008]). Contextual framing and the relative costs of trust may impact both sexes differently (Andreoni and Vesterlund Citation2001; Croson and Gneezy Citation2009; Ellingsen et al. Citation2012). Such differential impacts are likely to arise from underlying gender relations, beliefs, and stereotypes and should, therefore, be accounted for in the interpretation of results.

In sum, the results of the studies are mixed and cross-sex average differences are, when found, small. At the same time, we often found relatively large differences among men and among women. The results vary per article, and even per in-article experiment and are highly dependent on context. We found that many context variables that matter for the interpretation of possible gender differences are often not taken into account. Overall, we find some small traces of behavior pointing in the direction of gender stereotypes in line with agentic behavior and communal behavior, but only in the direction of the effect sizes and statistics, not in statistical significance and size effects. We cannot establish consistent average gender differences in any of the four behavioral attitudes that we analyzed. Various authors recognize that it is not wise to generalize findings since gender is in most cases not a dominating factor of behavior (Beckmann and Menkhoff Citation2008) and average differences do not necessarily imply systematic gender differences. Janet Shibley Hyde (Citation2005, Citation2007) has calculated Cohen’s d in a meta-analysis of forty-six studies that examine gender differences in a variety of behaviors and finds that 78 percent of the effect sizes are small or close to 0. In other words, the variability within one sex is much larger than the variability between men and women (Hyde Citation2007). This led her to formulate the gender similarities hypothesis, which holds that “males and females are similar on most, but not all, psychological variables. That is, men and women, as well as boys and girls, are more alike than they are different” (Hyde Citation2005: 581). Our review of two stereotyped masculine behaviors and two stereotyped feminine behaviors confirms her hypothesis.

DISCUSSION FROM A FEMINIST ECONOMICS PERSPECTIVE

Experimental designs vary widely, making it difficult to compare outcomes of studies. Researchers must account for multiple factors that can influence participants’ behavior. A variety of concerns about the generalizability of studies in behavioral economics exist. First, there are “ordinary” concerns, such as selection biases – where respondents seem to differ in their preferences, values, or attitudes from the population they are extracted from (Slonim et al. Citation2013) – and external validity, since results of lab experiments cannot be generalized (Camerer Citation2011). Second, men and women may differ in their reaction to variations in context or framing (Croson and Gneezy Citation2009). Third, differences in cross-cultural beliefs about gender exist (Nelson Citation2015), which may influence both the experimental setup and the subjects. Fourth, to achieve a balanced view, studies ought to publish both gender differences and gender similarities (Hyde Citation2007), since the way researchers communicate their results is important for preventing deleterious stereotypes (Nelson Citation2015). Moreover, this would help prevent the reporting bias discussed in the introduction. Fifth, Andreoni and Vesterlund (Citation2001) point out that men are more sensitive to the relative costs of altruistic behavior. This suggests that motives for decision making are not constant, but depend on opportunity costs. Sixth, there seems to be an implicit bias in the way researchers interpret and communicate their results. To illustrate, a statistically significant mean difference demonstrates a difference in aggregates of the groups in the population from which the sample is taken. However, it is invalid to draw general conclusions from these findings about the nature of every subject. In other words, there may be large overlaps between the two groups.

In addition to the above six points, payment in experiments and geographic location also tend to influence results. A major difference between experiments conducted by psychologists and behavioral economists is that the latter tend to incentivize their participants with monetary payoffs, arguing that this improves the external validity of their experiments. However, this introduces a potential selection bias (Abeler and Nosenzo Citation2013). Geography is another potential cause of selection bias because results from a particular participant pool might not generalize to the entire human population (Nelson Citation2015). At the same time, some studies on sex differences do focus on the role of cross-cultural differences (Gneezy, Leonard, and List Citation2009; Andersen et al. Citation2013).

A few scholars who apply a feminist approach to behavioral research have conducted careful analyses of gender differences in relation to gender beliefs, gender roles, stereotypes, and gender identities as well as gender inequalities in resources and institutions in societies. An interesting finding of these studies is that men tend, on average, to have stronger gender beliefs than women (Baber and Tucker Citation2006; Smiler and Gelman Citation2008; Vyrastekova, Sent, and van Staveren Citation2015). Other studies have indicated that women show weaker identification with roles stereotyped as masculine, such as leadership roles (Killeen, López-Zafra, and Eagly Citation2006; Koenig et al. Citation2011). And men tend to hold on more strongly to agentic roles than women tend to do to communal roles, for example, in leadership styles (Zenger and Folkman Citation2012). An interesting method to test for the effect of gender stereotypes on behavior is priming. This alerts participants in an experiment to either role-/identity-/belief-conforming attitudes or to opposing attitudes. Results of such experimental studies indicate that women tend to be more influenced than men by priming in some settings, whereas men seem to be more influenced by priming in other settings (Boschini, Muren, and Persson Citation2012). These findings indicate how important it is to disentangle gender roles, gender beliefs, and gender identification with stereotype or opposite roles in experimental settings.

Our analysis points to the need to be careful in the design and interpretation of behavioral research regarding gender differences. Statistically significant gender differences are merely a starting-point for feminist behavioral economic analysis, not necessarily a meaningful result in itself.

CONCLUSION

Our review of behavioral gender differences has led to several insights from a feminist economics perspective. First, the results for each of the four behavioral dimensions are mixed when it comes to gender differences. Second, only a handful of the eighty-one studies for which we were able to calculate size effects and statistics show substantive significant differences. Third, many studies are not gender-aware in their interpretations of the findings. They do not inquire into gendered causal mechanisms of gender roles, gender identities, stereotypes, gender beliefs, social interaction effects between individuals and at the group level, and social-biological interactions at the individual level. This inadequacy leads to biased interpretations of statistically significant results, even when they show substantive size effects. This leaves much space for often unintended but clearly unjustified essentialist explanations of gender differences in economic behavior. Moreover, in the presence of publication bias, the gender differences found in the literature tend to overstate the true differential. Overall, this situation provides not only opportunities for feminist economic research in the area of experimental economics but also points to a responsibility of experimental economists in general to report statistics on size effects and to provide explanations of gender differences in relation to a variety of gender-laden contexts in the experimental design. In other words, unless carefully designed experiments control for gendered contexts through socialization, gender norms, gender beliefs, priming effects, interaction effects of men and women based on stereotypes of each other, and reactions to expected punishments for behavior that transgresses dominant gender norms, experimental results showing substantive, statistically significant gender differences cannot provide meaningful evidence for average natural or essential differences in the behavior of men and women.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (156.3 KB)SUPPLEMENTAL DATA

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2018.1532595.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Esther-Mirjam Sent

Esther-Mirjam Sent is Professor of Economic Theory and Policy at Radboud University Nijmegen and Senator for the Labour Party.

Irene van Staveren

Irene van Staveren is Professor of Pluralist Development Economics at the International Institute of Social Studies of Erasmus University Rotterdam.

Notes

1 In the presence of strong tendencies to gender stereotype, Nelson (Citation2014) suggests different, tougher guidelines for communicating whether a difference is large, medium, or small.

2 The Supplemental Online Appendix includes an explanation of the different experimental settings.

3 There is an overlap of seven studies between Nelson’s (Citation2015) selection of thirty-five studies (20 percent) and our selection of twenty studies for risk behavior (35 percent). For all four behavioral dimensions, we used the same selection criteria as described earlier, so that the two groups of risk studies (Nelson’s and ours) are not the same, although they overlap to a minor extent.

4 Gender awareness in experimental settings is important. For example, many men do not take kindly to losing to women, and many confident women have learned to hold themselves back to avoid an expected backlash. Indeed, it is exactly the highest achievers who are most affected by stereotype threat. Hence, it is plausible that it is the most competent/confident women who are most likely to feel threatened by a situation in which they would be put into competition against men. (The women who expect to lose do not have to be concerned about harming men’s egos!)

REFERENCES

- Abeler, Johannes and Daniele Nosenzo. 2013. “Self-Selection into Economics Experiments Is Driven by Monetary Rewards.” IZA Discussion Paper 7374, Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA).

- Agnew, Julie R., Lisa R. Anderson, Jeffrey R. Gerlach, and Lisa R. Szykman. 2008. “Who Chooses Annuities? An Experimental Investigation of the Role of Gender, Framing, and Defaults.” American Economic Review 98(2): 418–22. doi: 10.1257/aer.98.2.418

- Agnew, Julie, Pierluigi Balduzzi, and Annika Sundén. 2003. “Portfolio Choice and Trading in a Large 401(k) Plan.” American Economic Review 93(1): 193–215. doi: 10.1257/000282803321455223

- Albert, Max, Werner Güth, Erich Kirchler, and Boris Maciejovsky. 2007. “Are We Nice(r) to Nice(r) People? An Experimental Analysis.” Experimental Economics 10(1): 53–69. doi: 10.1007/s10683-006-9131-3

- Andersen, Steffen, Seda Ertac, Uri Gneezy, John A. List, and Sandra Maximiano. 2013. “Gender, Competitiveness, and Socialization at a Young Age: Evidence from a Matrilineal and a Patriarchal Society.” Review of Economics and Statistics 95(4): 1438–43. doi: 10.1162/REST_a_00312

- Anderson, Lisa R., Francis J. DiTraglia, and Jeffrey R. Gerlach. 2011. “Measuring Altruism in a Public Goods Experiment: A Comparison of U.S. and Czech Subjects.” Experimental Economics 14(3): 426–37. doi: 10.1007/s10683-011-9274-8

- Andreoni, James and B. Douglas Bernheim. 2009. “Social Image and the 50–50 Norm: A Theoretical and Experimental Analysis of Audience Effects.” Econometrica 77(5): 1607–36. doi: 10.3982/ECTA7384

- Andreoni, James and Lise Vesterlund. 2001. “Which is the Fair Sex? Gender Differences in Altruism.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 116(1): 293–312. doi: 10.1162/003355301556419

- Apicella, Coren L., Justin M. Carré, and Anna Dreber. 2015. “Testosterone and Economic Risk Taking: A Review.” Adaptive Human Behavior and Physiology 1(3): 358–85. doi: 10.1007/s40750-014-0020-2

- Apicella, Coren L., Anna Dreber, Benjamin Campbell, Peter B. Gray, Moshe Hoffman, and Anthony C. Little. 2008. “Testosterone and Financial Risk Preferences.” Evolution and Human Behavior 29(6): 384–90. doi: 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2008.07.001

- Ariely, Dan, Anat Bracha, and Stephan Meier. 2009. “Doing Good or Doing Well? Image Motivation and Monetary Incentives in Behaving Prosocially.” American Economic Review 99(1): 544–55. doi: 10.1257/aer.99.1.544

- Babcock, Linda and George Loewenstein. 1997. “Explaining Bargaining Impasse: The Role of Self-Serving Biases.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 11(1): 109–26. doi: 10.1257/jep.11.1.109

- Baber, Kristine and Corinna Tucker. 2006. “The Social Roles Questionnaire: A New Approach to Measuring Attitudes Toward Gender.” Sex Roles 54(7/8): 459–67. doi: 10.1007/s11199-006-9018-y

- Balafoutas, Loukas, Rudolf Kerschbamer, and Matthias Sutter. 2012. “Distributional Preferences and Competitive Behavior.” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 83(1): 125–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2011.06.018

- Balafoutas, Loukas and Matthias Sutter. 2012. “Affirmative Action Policies Promote Women and Do Not Harm Efficiency in the Laboratory.” Science 335(6068): 579–82. doi: 10.1126/science.1211180

- Barber, Brad M. and Terrance Odean. 2001. “Boys Will Be Boys: Gender, Overconfidence, and Common Stock Investment.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 116(1): 261–92. doi: 10.1162/003355301556400

- Becker, Gordon M., Morris H. Degroot, and Jacob Marschak. 1964. “Measuring Utility by a Single-Response Sequential Method.” Behavioral Science 9(3): 226–32. doi: 10.1002/bs.3830090304

- Beckmann, Daniela and Lukas Menkhoff. 2008. “Will Women Be Women? Analyzing the Gender Difference among Financial Experts.” Kyklos 61(3): 364–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6435.2008.00406.x

- Bem, Sandra L. 1974. “The Measurement of Psychological Androgyny.” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 42(2): 155–62. doi: 10.1037/h0036215

- Ben-Ner, Avner, Fanmin Kong, and Louis Putterman. 2004. “Share and Share Alike? Gender-Pairing, Personality, and Cognitive Ability as Determinants of Giving.” Journal of Economic Psychology 25(5): 581–9. doi: 10.1016/S0167-4870(03)00065-5

- Ben-Ner, Avner, Louis Putterman, Fanmin Kong, and Dan Magan. 2004. “Reciprocity in a Two-Part Dictator Game.” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 53(3): 333–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2002.12.001

- Bengtsson, Claes, Mats Persson, and Peter Willenhag. 2005. “Gender and Over-confidence.” Economics Letters 86(2): 199–203. doi: 10.1016/j.econlet.2004.07.012

- Berg, Joyce, John Dickhaut, and Kevin McCabe. 1995. “Trust, Reciprocity, and Social History.” Games and Economic Behavior 10(1): 122–42. doi: 10.1006/game.1995.1027

- Beyer, Sylvia. 1990. “Gender Differences in the Accuracy of Self-Evaluations of Performance.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 59(5): 960–70. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.59.5.960

- Bhandari, Gokul and Richard Deaves. 2006. “The Demographics of Overconfidence.” Journal of Behavioral Finance 7(1): 5–11. doi: 10.1207/s15427579jpfm0701_2

- Bittman, Michael, Paula England, Nancy Folbre, Liana Sayer, and George Matheson. 2003. “When Does Gender Trump Money? Bargaining and Time in Household Work.” American Journal of Sociology 109(1): 186–214. doi: 10.1086/378341

- Bolton, Gary E. and Elena Katok. 1995. “An Experimental Test for Gender Differences in Beneficent Behavior.” Economics Letters 48(3/4): 287–92. doi: 10.1016/0165-1765(94)00621-8

- Bolton, Gary E., Elena Katok, and Rami Zwick. 1998. “Dictator Game Giving: Rules of Fairness versus Acts of Kindness.” International Journal of Game Theory 27(2): 269–99. doi: 10.1007/s001820050072

- Bonein, Aurélie and Daniel Serra. 2009. “Gender Pairing Bias in Trustworthiness.” Journal of Socio-Economics 38(5): 779–89. doi: 10.1016/j.socec.2009.03.003

- Booij, Adam S., Bernard M. S. Van Praag, and Gijs van de Kuilen. 2010. “A Parametric Analysis of Prospect Theory’s Functionals for the General Population.” Theory and Decision 68(1/2): 115–48.

- Booth, Alan, Douglas A. Granger, Allan Mazur, and Katie T. Kivlighan. 2006. “Testosterone and Social Behavior.” Social Forces 85(1): 167–91. doi: 10.1353/sof.2006.0116

- Booth, Alison L. and Patrick Nolen. 2012. “Choosing to Compete: How Different Are Girls and Boys?” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 81(2): 542–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2011.07.018

- Borghans, Lex, James J. Heckman, Bart H. H. Golsteyn, and Huub Meijers. 2009. “Gender Differences in Risk Aversion and Ambiguity Aversion.” Journal of the European Economic Association 7(2/3): 649–58. doi: 10.1162/JEEA.2009.7.2-3.649

- Boschini, Anne, Astri Muren, and Mats Persson. 2012. “Constructing Gender Differences in the Economics Lab.” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 84(3): 741–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2012.09.024

- Buchan, Nancy R., Rachel T. A. Croson, and Sara Solnick. 2008. “Trust and Gender: An Examination of Behavior and Beliefs in the Investment Game.” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 68(3/4): 466–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2007.10.006

- Buchan, Nancy R., Eric J. Johnson, and Rachel T. A. Croson. 2006. “Let’s Get Personal: An International Examination of the Influence of Communication, Culture and Social Distance on Other Regarding Preferences.” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 60(3): 373–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2004.03.017

- Cadsby, C. Bram, Yasuyo Hamaguchi, Toshiji Kawagoe, Elizabeth Maynes, and Fei Song. 2007. “Cross-National Gender Differences in Behavior in a Threshold Public Goods Game: Japan versus Canada.” Journal of Economic Psychology 28(2): 242–60. doi: 10.1016/j.joep.2006.06.009

- Cadsby, C. Bram and Elizabeth Maynes. 2005. “Gender, Risk Aversion, and the Drawing Power of Equilibrium in an Experimental Corporate Takeover Game.” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 56(1): 39–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2003.03.001

- Cadsby, C. Bram, Maroš Servátka, and Fei Song. 2010. “Gender and Generosity: Does Degree of Anonymity or Group Gender Composition Matter?” Experimental Economics 13(3): 299–308. doi: 10.1007/s10683-010-9242-8

- Camerer, Colin F. 2011. “The Promise and Success of Lab-Field Generalizability in Experimental Economics: A Critical Reply to Levitt and List.” Working Paper, California Institute of Technology.

- Carothers, Bobbi J. and Harry T. Reis. 2013. “Men and Women Are from Earth: Examining the Latent Structure of Gender.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 104(2): 385–407. doi: 10.1037/a0030437

- Carr, Priyanka B. and Claude M. Steele. 2010. “Stereotype Threat Affects Financial Decision Making.” Psychological Science 21(10): 1411–6. doi: 10.1177/0956797610384146

- Castillo, Marco E. and Philip J. Cross. 2008. “Of Mice and Men: Within Gender Variation in Strategic Behavior.” Games and Economic Behavior 64(2): 421–32. doi: 10.1016/j.geb.2008.01.009

- Cesarini, David, Örjan Sandewall, and Magnus Johannesson. 2006. “Confidence Interval Estimation Tasks and the Economics of Overconfidence.” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 61(3): 453–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2004.10.010

- Charness, Gary and Garance Genicot. 2009. “Informal Risk Sharing in an Infinite-Horizon Experiment.” Economic Journal 119(537): 796–825. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0297.2009.02248.x

- Charness, Gary and Uri Gneezy. 2012. “Strong Evidence for Gender Differences in Risk Taking.” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 83(1): 50–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2011.06.007

- Charness, Gary and Aldo Rustichini. 2011. “Gender Differences in Cooperation with Group Membership.” Games and Economic Behavior 72(1): 77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.geb.2010.07.006

- Chaudhuri, Ananish and Lata Gangadharan. 2007. “An Experimental Analysis of Trust and Trustworthiness.” Southern Economic Journal 73(4): 959–85.

- Chaudhuri, Ananish, Tirnud Paichayontvijit, and Lifeng Shen. 2013. “Gender Differences in Trust and Trustworthiness: Individuals, Single Sex and Mixed Sex Groups.” Journal of Economic Psychology 34: 181–94. doi: 10.1016/j.joep.2012.09.013

- Coates, J. M. and J. Herbert. 2008. “Endogenous Steroids and Financial Risk Taking on a London Trading Floor.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 105(16): 6167–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704025105

- Cohen, Jacob. 1988. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd Ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Conlin, Michael, Michael Lynn, and Ted O’Donoghue. 2003. “The Norm of Restaurant Tipping.” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 52(3): 297–321. doi: 10.1016/S0167-2681(03)00030-1

- Correll, Shelley J. 2001. “Gender and the Career Choice Process: The Role of Biased Self-Assessments.” American Journal of Sociology 106(6): 1691–730. doi: 10.1086/321299

- Cox, James C. 2004. “How to Identify Trust and Reciprocity.” Games and Economic Behavior 46(2): 260–81. doi: 10.1016/S0899-8256(03)00119-2

- Crosetto, Paolo, Antonio Filippin, and Janna Heider. 2013. “A Study of Outcome Reporting Bias Using Gender Differences in Risk Attitudes.” CESifo Working Paper 4466, Center for Economic Studies and Ifo Institute (CESifo).

- Croson, Rachel and Nancy Buchan. 1999. “Gender and Culture: International Experimental Evidence from Trust Games.” American Economic Review 89(2): 386–91. doi: 10.1257/aer.89.2.386

- Croson, Rachel, and Uri Gneezy. 2009. “Gender Differences in Preferences.” Journal of Economic Literature 47(2): 448–74. doi: 10.1257/jel.47.2.448

- Dahlbom, L., A. Jakobsson, N. Jakobsson, and A. Kotsadam. 2011. “Gender and Overconfidence: Are Girls Really Overconfident?” Applied Economics Letters 18(4): 325–7. doi: 10.1080/13504851003670668

- Datta Gupta, Nabanita, Anders Poulsen, and Marie-Claire Villeval. 2005. “Male and Female Competitive Behavior: Experimental Evidence.” GATE Working Paper No. W.P. 05-12, GATE Groupe d’Analyse et de Théorie Économique.

- Datta Gupta, Nabanita, Anders Poulsen, and Marie-Claire Villeval. 2013. “Gender Matching and Competitiveness: Experimental Evidence.” Economic Inquiry 51(1): 816–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-7295.2011.00378.x

- Deaves, Richard, Erik Lüders, and Guo Ying Luo. 2009. “An Experimental Test of the Impact of Overconfidence and Gender on Trading Activity.” Review of Finance 13(3): 555–75. doi: 10.1093/rof/rfn023

- DellaVigna, Stefano, John A. List, and Ulrike Malmendier. 2012. “Testing for Altruism and Social Pressure in Charitable Giving.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 127(1): 1–56. doi: 10.1093/qje/qjr050

- DellaVigna, Stefano, John A. List, Ulrike Malmendier, and Gautam Rao. 2013. “The Importance of Being Marginal: Gender Differences in Generosity.” American Economic Review 103(3): 586–90. doi: 10.1257/aer.103.3.586

- Dreber, Anna, Emma von Essen, and Eva Ranehill. 2014. “Gender and Competition in Adolescence: Task Matters.” Experimental Economics 17(1): 154–72. doi: 10.1007/s10683-013-9361-0

- Dyble, M., G. D. Salali, N. Chaudhary, A. Page, D. Smith, J. Thompson, L. Vinicius, R. Mace, and A. B. Migliano. 2015. “Sex Equality Can Explain the Unique Social Structure of Hunter-Gatherer Bands.” Science 348(6236): 796–8. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa5139

- Eagly, Alice and Wendy Wood. 2011. “Feminism and the Evolution of Sex Differences and Similarities.” Sex Roles 64(9/10): 758–67. doi: 10.1007/s11199-011-9949-9

- Eckel, Catherine C. and Philip J. Grossman. 1996. “The Relative Price of Fairness: Gender Differences in a Punishment Game.” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 30(2): 143–58. doi: 10.1016/S0167-2681(96)00854-2

- Eckel, Catherine C. and Philip J. Grossman. 1998. “Are Women Less Selfish than Men? Evidence from Dictator Experiments.” Economic Journal 108(448): 726–35. doi: 10.1111/1468-0297.00311

- Eckel, Catherine C. and Philip J. Grossman. 2001. “Chivalry and Solidarity in Ultimatum Games.” Economic Inquiry 39(2): 171–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-7295.2001.tb00059.x

- Eckel, Catherine C. and Philip J. Grossman. 2002. “Sex Differences and Statistical Stereotyping in Attitudes toward Financial Risk.” Evolution and Human Behavior 23(4): 281–95. doi: 10.1016/S1090-5138(02)00097-1

- Eckel, Catherine C. and Philip J. Grossman. 2008. “Men, Women and Risk Aversion: Experimental Evidence.” In Handbook of Experimental Economics Results, Vol. 1, edited by Charles R. Plott and Vernon L. Smith, 1061–73. Amsterdam: North Holland.

- Eckel, Catherine C. and Rick K. Wilson. 2004. “Is Trust a Risky Decision?” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 55(4): 447–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2003.11.003

- Eisenegger, C., M. Naef, R. Snozzi, M. Heinrichs, and E. Fehr. 2010. “Prejudice and Truth about the Effect of Testosterone on Human Bargaining Behaviour.” Nature 463(7279): 356–9. doi: 10.1038/nature08711

- Ellingsen, Tore, Magnus Johannesson, Johanna Mollerstrom, and Sara Munkhammar. 2012. “Social Framing Effects: Preferences or Beliefs?” Games and Economic Behavior 76(1): 117–30. doi: 10.1016/j.geb.2012.05.007

- Endres, Megan. 2006. “The Effectiveness of Assigned Goals in Complex Financial Decision Making and the Importance of Gender.” Theory and Decision 61(2): 129–57. doi: 10.1007/s11238-006-0006-z

- Ertac, Seda and Mehmet Y. Gurdal. 2012. “Deciding to Decide: Gender, Leadership and Risk-Taking in Groups.” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 83(1): 24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2011.06.009

- Ertac, Seda and Balazs Szentes. 2011. “The Effect of Information on Gender Differences in Competitiveness: Experimental Evidence.” Koç University-TUSIAD Economic Research Forum Working Paper 1104.

- Etang, Alvin, David Fielding, and Stephen Knowles. 2011. “Does Trust Extend Beyond the Village? Experimental Trust and Social Distance in Cameroon.” Experimental Economics 14(1): 15–35. doi: 10.1007/s10683-010-9255-3

- Evans, Anthony M. and William Revelle. 2008. “Survey and Behavioral Measurements of Interpersonal Trust.” Journal of Research in Personality 42(6): 1585–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2008.07.011

- Fehr-Duda, Helga, Thomas Epper, Adrian Bruhin, and Renate Schubert. 2011. “Risk and Rationality: The Effects of Mood and Decision Rules on Probability Weighting.” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 78(1/2): 14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2010.12.004

- Ferber, Marianne A. and Julie A. Nelson, eds. 1993. Beyond Economic Man: Feminist Theory and Economics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.