ABSTRACT

For social enterprise to matter to racialized people, it must be purposefully embedded in the community. This study examines three nonprofit organizations led by women engaged in community economic development work – Firgrove Learning and Innovation Community Centre, Warden Woods Community Centre, and Elspeth Heyworth Centre for Women – in Toronto, one of the largest cities in North America. This study explores the work of these anti-racist feminist leaders who lack the certainty of funding from federal sources, yet understand that the key to making ethical community economies is to advance politicized economic solidarity and not to legitimize the corporatization of the social economy. This research also draws on the ethical coordinates of J.K Gibson-Graham to provoke a radical shift in the accepted understanding of social innovation in the enterprising development sector.

HIGHLIGHTS

Mainstream definitions of social enterprise exclude businesses led by marginalized peoples.

Three racialized women in Toronto lead social enterprises with ethics and politicized action.

These enterprises benefit their communities and fight racism in the capitalist economy.

The study makes visible racialized peoples’ social-enterprise economy.

Social enterprises must promote politicized economic solidarity and anti-racist feminism.

INTRODUCTION

Understanding, promoting, and protecting the rights of racial minorities in the economy is more urgent than ever before. Blatant forms of right-wing, xenophobic, and racist politics have permeated the world, and the recent COVID-19 pandemic has shown how vulnerable non-white minorities are in a predominantly white society. In Canada, we find examples of racial bias, hatred and violence, and anti-immigrant sentiments. From the killings of Muslims at the Islamic Cultural Centre in a suburb of Quebec City in 2017 (Cherney and Vieira Citation2017), to the brutal attack of teenager Dafonte Miller by an off-duty policeman and his brother in Whitby, Ontario, who then tried to conceal it (Rizza Citation2017), these are stories we hear over and over again. Montreal-based academic David Austin (Citation2013) reminds us that a deeply embedded racism is part of Canada’s history. There is racial tension, even in areas deemed culturally diverse, and leaders are working on socially innovative programs to help those affected by racism in business and society.

Cambridge Professor Ha-Joon Chang, in a video titled “Learn the Language of Power,” (Institute for New Economic Thinking Citation2019) makes it abundantly clear that ordinary people need to know economics in order to appreciate the experience of what it means not to have things. But too many experts have duped the public into believing that economics is too complex. In this study, three racialized women know better. They lead social enterprises as a form of development, organizing their enterprises as politicized economic solidarity to fight against misogyny and racism in the market. In other words, if mainstream businesses are structured in such a way to exploit Black and racialized people, then the women in this study reveal how they can combat racial capitalism through an ethical approach to social enterprises.Footnote1

A recent report, “Working Poor in the Toronto Region” (Citation2019) by the Metcalf Foundation, repeats what is known in the city: Black and non-white diaspora tend to be the poorest, in spite of their full-time employment (Monsebraaten Citation2019). Yet, the report fails to adequately explain why racialized women earn far less than men. The women leaders in this study are acutely aware of these biases, and thus they initiate innovation through a deliberate program of politicized action to turn social enterprises into entities that push against inequities.

For social enterprises to work for racialized people, these socially inclined businesses must be purposefully embedded in the community; otherwise they are only masquerading as agents of social change (Pearce Citation2009). In this paper, I examine the cases of three social enterprises led by anti-racist, racialized feminists engaged in community economic development work through nonprofit organizations in Toronto. The leaders in these cases conscientiously use business as a tool to politicize what they do for social good in a way that can upset the inequality within society. Timo Korstenbroek and Peer Smets (Citation2019), in their work in Amsterdam, find that there are social entrepreneurs who are “antagonistic organizers” who refuse to be tied down to complacent systems and try to create new systems. My sense is that the women in this study are activists, and they are not alone in turning social enterprises into ethical businesses that are fighting against racism. This research also draws on the ethical coordinates of J.K. Gibson-Graham and Black feminists’ concept of lived experience to provoke a radical shift in our understanding of how resource allocations counteract exclusion.

DEFINING THE SOCIAL ECONOMY FOR RACIAL MINORITIES

In the Greater Toronto Area (GTA), with a population of 5.6 million people of which 50 percent are foreign-born (Toronto Foundation Citation2017), notable women of color lead community projects. Few of these women-led enterprises, however, are analyzed or taught in institutions of higher learning (Hossein Citation2017a). In a large-scale study across the Netherlands, Irene van Staveren and Zahid Pervaiz (Citation2017) found that when there is no bolstering of community cohesion, the risks and costs of discrimination and the politics of exclusion shift to those who are racialized members in a society. For example, Canadian scholar Joseph Mensah (Citation2010) in Black Canadians: History, Experience, Social Conditions, demonstrates that Somali and Haitian Canadians have endured racial discrimination in employment, education, and housing since emigrating to Ontario and Quebec.

Yet the Haas Institute’s annual report Inclusivity Index: Measuring Global Inclusion and Marginality gave Canada a high score of 70.38, indicating that citizens have access to services and that legal infringement of human rights are minimal (World Bank Citation2017; Menendian, Elsheikh, and Gambhir Citation2018). While Canada may score high in terms of formal inclusion compared to other countries, it still experiences serious racial tensions, as noted in academic research, national newspapers, and projects, and there are efforts to disaggregate data in as many fields as possible (Galabuzi Citation2006).Footnote2 Facing such exclusion, groups that feel alienated will seek refuge in the social economy (Hossein Citation2018).

In English Canada, “social economy” has been defined as one that “bridges many different types of self-governing organizations that are guided by their social objectives in the goods and services that they offer” (Quarter, Mook, and Armstrong Citation2018: 6). The social economy sector is distinct from both the public sector (the government) and the private sector (corporations and for-profit businesses). A recent book by Jack Quarter, Sherida Ryan, and Andrea Chan (Citation2015) on social purpose enterprises in Toronto observes organizations (such as Good Food Markets and Sistering) that involve racialized people, but very few cases described are actually led by people of color. My work in The Black Social Economy (Citation2018) focuses on how excluded groups, driven by the intense forms of racism in the dominant economy, find refuge in the social economy and try to remake it in a way that it goes beyond interacting but antagonizing exclusionary aspects within the economy.

Canada’s social economy has been important to the lives of racialized minorities, and the stories about it need to be diversified. One of the earliest forms of social and economic cooperation was the Underground Railroad in which hundreds of Black Africans from the US migrated to southern Canada fleeing slavery in the mid-1800s, but this is seldom the starting point of public histories on economic and social solidarity. Canadians usually hear about Quebec’s economie social, and the movement Desjardins, with its caisses populaires, which addressed the business exclusion of a Catholic and French-speaking minority in Levis, Quebec in the early 1900s (Rudin Citation1990; Shragge and Fontan Citation2000; Mendell Citation2009). The Antigonish Movement in Nova Scotia in the 1920s – led by two Catholic priests, Moses Coady and Jimmy Tompkins – improved the economic lives of white fisher-folk through cooperatives and adult pedagogy in a system called “kitchen tables,” which inspired a new way of doing business (Alexander Citation1997). Another impressive story of doing business differently is that of businesswoman Viola Desmond (who now appears on the Canadian ten-dollar bill), who trained young Black women in cosmetology and to foster financial independence in Halifax, Nova Scotia (Reynolds Citation2016). In 1946, she exposed Canada’s deep-seated racism when she was arrested for refusing to conform to the segregation policy at Roseland Theatre, and because of her business knowledge and security, she stood up to an unequal economic system. Yet, she is never regarded as a social entrepreneur in the social economy. Thousands of mutual aid groups and rotating savings and credit associations (ROSCAs) organized by Black and racialized women are active in Canada, but they too are largely ignored as making significant cooperative contributions to Canada’s social economy.

SOCIAL ENTERPRISE AS AN ANTI-RACIST FEMINIST TOOL

Businesses with a social mission are commonly known as “social enterprises,” and they are not new. David Bornstein (Citation2004) refers to social entrepreneurs as “restless” people who are fed up with the slowness of corporations’ and government responses to improve conditions, so everyday people are driving a citizen’s sector. This idea of businesses with a purpose has long existed for women of color, especially in the form of mutual aid groups, money pooling, and cooperatives.

For a long time, people have engaged in double-bottom-line businesses (businesses that consider both social and economic objectives) because they were committed to a cause and wanted to see a change in society (Hart, Laville, and Cattani Citation2010). Ash Amin (Citation2009) defines organizations that are part of the social economy as those rooted in community and that prioritize development over profit. In Canada, social enterprises have also been defined as part of the third sector or social economy because they “bridge” private and public sector values (Quarter, Mook, and Armstrong Citation2018). The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) defines social enterprise as

any private activity conducted in the public interest, organized with an entrepreneurial strategy for whose main purpose is not the maximization of profit but attainment of certain economic and social goals, and which has a capacity for bringing innovative solutions to the problems of social exclusion and unemployment. (Citation1999, 10)

In my own meetings with activists in Canada, US, and India, I find that there is a rhetoric of “innovation” in the social and solidarity economies by leaders who claim to be “socially innovative” and all knowing. These self-declared “innovators” do not know what being poor or being excluded is like; yet they peddle and choose groups who are “socially innovative.” Being socially innovative appears to have become analytically empty because the very people leading innovation have no lived experience. What is evident time and time again is that donors (read: white) will endow resources in less-qualified people who do not have the experience of the racialized women. The women in this study, however, have managed projects with ethics for decades, and they are able to speak to ways to address the deficits in human development unlike those who are merely seizing buzzwords.Footnote3

INVOKING GIBSON-GRAHAM’S DIVERSE ECONOMIES

The diverse economies (DE) literature of J.K. Gibson-Graham (Citation1996, Citation2006; Gibson et al. Citation2018) by feminist economic geographers Katherine Gibson and the late Julie Graham have influenced this study. The work on community economies has been around for about two decades, first initiated by The End of Capitalism (As We Knew It): A Feminist Critique of Political Economy (Citation1996) and Postcapitalist Politics (Citation2006), and they are relevant to the study of social enterprises with a moral purpose. The DE literature recognizes that other countries have knowledge on how to make economies inclusive, and the Capitalism versus Marxism narrative is stuck in binaries. DE diverges from this narrative because it refuses to play into ideological debates and moves this binary along by shifting our understanding of the economy to inventorying the different ways people interact and engage in business in society (Gibson-Graham Citation2006; Gibson et al. Citation2018). Take Back the Economy (Gibson-Graham, Cameron, and Healy Citation2013) provides a “how to” guide on ethical economies that put people first.

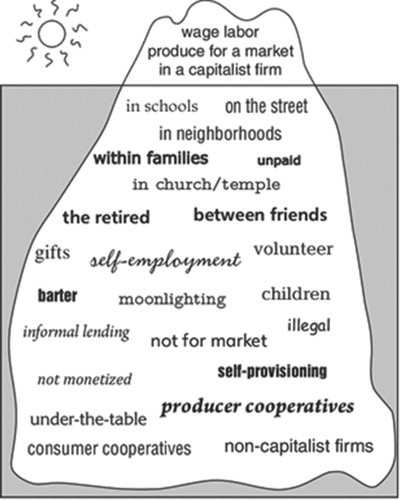

As feminists who acknowledge other economies, Gibson-Graham explain the world’s economy using the “iceberg analogy.” The visible part of the iceberg on the surface represents the formal capitalist economy; but this exposed part is also compared to the submerged part of the iceberg – the largest part. The big part of the iceberg is not visible to the eye, but it is where most of the economy takes place (see Figure ). The DE literature is aware that the economies of women and minorities are hidden from plain view.

Figure 1 The Iceberg by J.K Gibson-Graham Notes: This drawing was originally done by Ken Byrne. The diagram has been used in a number of publishing venues, but I draw on it from Gibson-Graham, Cameron, and Healy (Citation2013).

Southern peoples, in the Global South and diaspora, have always engaged in business ethics as a way to push against an exclusionary economic system. Take the community-building work of Jamaican-born Marcus Garvey, founder of the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), who immigrated to New York City only to encounter intense forms of racial discrimination. He made it is his life’s work to campaign for human rights, racial justice, and self-love among the Black diaspora and did this through Black-owned cooperatives (Martin Citation1976; Stein Citation1986; Lewis Citation1987). Members of this movement, called Garveyites, were creating “social enterprises” long before they were named so (K’nife, Bernard, and Dixon Citation2011; Hossein Citation2017b).

Within DE there are a set of ethical coordinates to guide community economies because these forms of businesses have a different nature than raw capitalist enterprises (Gibson-Graham Citation2006; Gibson-Graham, Cameron, and Healy Citation2013). I draw on the following ethical coordinates: (1) recognize the needs of people by an array of economies, not one model; (2) distribute the surplus goods and services in ways to help ourselves and others; (3) use goods in ways that are thoughtful about the planet; and (4) activate the “commons” so that people share more with each other.Footnote4 These ethical coordinates are vital for feminists of color concerned about equitable economies. However, the coordinates are missing the politicized aspect of remaking enterprises in ways that are cognizant of the exclusion and racism embedded in societies, even ones that are well intentioned.

Crowd-funding is another concept that seems like the internet birthed, but like social enterprises, it is not new. Black, racialized people, and newcomers have purposefully engaged in pooling of funds and crowd-funding from kin to support goals such as education, travel, and funerals. Bridgett Davis (Citation2019) documents self-help among African-American families in Detroit in hard financial times. I also remember my Guyanese-born father doing people’s income taxes every spring; our house buzzed with workers doing small repairs, yard work, or getting a leg of lamb as a way to repay my father for his services. Bartering, trading services, and crowd-funding are all very much part of the community economies (see Gibson-Graham’s iceberg above). For racialized people, these economic ways are rooted in norms of trust and reciprocity that are sustenance for groups stigmatized in the places they live.

CONCEPTUALIZING SOCIAL ENTERPRISES WITHIN THE REALM OF INNOVATION

How are terms like “social innovation” and “social enterprise” defined? Who gets to decide the definition? It seems there is no straightforward answer to this question; social innovation and social enterprise have become buzzwords and have subjective definitions (Pol and Ville Citation2009; Young Foundation Citation2012). The term “entrepreneur” is clear-cut and comes from the French word entreprendre, to undertake a challenging activity (Peredo and MacLean Citation2006). Adding the word “social” to entrepreneurship is often viewed as innovative because it involves using business principles while dealing with complex human needs in an era of diminishing public funds (Thompson and Doherty Citation2006; Quarter, Mook, and Armstrong Citation2018).

The term social enterprise can be understood on a continuum: on one end, we find many organizations are heavily vested in a cause and use business solutions to solve a problem. These enterprises are led by social entrepreneurs who care about society. Founded by Mohammed Yunus, Grameen Bank is an example of a social enterprise with a mission: it is a community bank that assists women with financial access and education. Yunus (Citation2010) coined the term “social business,” meaning self-sustaining businesses that take in profits but channel the funds back to nonprofit activities, such as the Grameen phone. On the opposite end of the continuum are organizations aligned with the private sector goal of making profits while inserting social objectives as minimally as possible. Anna Maria Peredo and Murdith MacLean (Citation2006) argue that a dark side emerges within this social enterprise sector because these businesses seemingly care about making money akin to corporations. Mission drift is an issue occurring in social enterprises that are unable to evenly manage their social and economic objectives.

These varying definitions of social enterprise are not considerate of the systemic bias in certain contexts that makes social enterprises a necessity for marginalized people. In feminist economics there is an understanding that the entanglement between politics and economics needs to be politicized. Definitions for “innovation” and “social enterprise” are void of any consideration of racism occurring in society and fail to explain why non-white people take up social enterprises (Taylor Citation1970; Elson and Hall Citation2012; Bouchard Citation2013; Brouard, McMurtry, and Vieta Citation2015; Nicholls, Simon, and Gabriel Citation2015; Bittencourt et al. Citation2016; Ontario Innovation Agenda Citationn.d.). Business professor Kunle Akingbola, in his case study of A-Way Express Courier, uses this idea of social enterprise to think about identities and defines employment social enterprise (formally known as social-purpose enterprise) as “a market-based entity founded and supported by a non-profit organization for the purposes of economically and socially benefiting persons on the social margins who are employed in or trained through the enterprise” (Citation2015: 52).

Canadian scholar Frances Westley (Citation2013) defines social innovation as any initiative (product, process, program, policy, project, or platform) that challenges deeply rooted forms of exclusion to contribute to changing the defining routines, resource, and authority flows or beliefs of the broader social system to make society liveable and cohesive for all people.Footnote5 This definition is useful because it underlines the importance of racial equality and the equitable distribution of investments to ensure social cohesion. I would add that social innovation should also consider people who do impressive work with limited resources.

Community economies work not only advances ethical economies, but anti-racist feminists ensure that within the social enterprise sector there is politicized economic solidarity. Anything less than this is peddling a walking horse of capitalism. For a social enterprise to be meaningful to diverse groups, politicized economic solidarity should be at its core so that oppressed people can intentionally carve out spaces in business for excluded groups. In other words, social enterprise is business that ensures social cohesion, resilient societies, inclusive growth, equity, diversity, and inclusion.

METHODS AND APPROACHES

This study undertook ethnographic and semi-structured interviews with the three executive directors, and all human ethics protocols were completed over the years.Footnote6 All three institutions under discussion are nonprofits serving largely low-income, racialized communities in the east and west ends of the GTA. The exchange and learning has thus been a two-way street, and the learning was carried out on what Sandra Harding (Citation1987) has called a critical plane of them sharing knowledge of what was going on in the social enterprise sector. I have also engaged with some of the women in joint partnerships at conferences and academic events; for example, I organize workshops and a Black History month event in conjunction with Warden Woods Community Centre (WWCC).

Over the course of six years (2013–19), I followed each executive director by assigning students to work with them as part of a placement course. Since 2014, all three institutions have been part of a practicum course in which undergraduate university students intern at these organizations for course credit. In 2016, the local Member of Parliament, at the time, Judy Sgro awarded the students assigned to Firgrove Learning and Innovation Community Centre (FLICC) for their dedication in assisting to set up the organization’s first-ever social enterprise and for their work in drafting a business plan. The story was in the Yfile (Citation2017), York University’s community news. I remember that the first cohort of students were troubled by the fact that these institutions were not the “brand name” nonprofits they knew, such as CARE or United Way. This was precisely the reason why they were chosen as partner institutions for the course – because these leaders quietly carried out work in low-income communities for decades without fanfare. Some of the material describing the institutions in this paper comes out of the practicum reports carried out by students mapping the organizations’ role in Canada’s social economy.

Student research on these institutions has been useful, as many social enterprise hubs (such as the Toronto Enterprise Fund or the Canadian Community Economic Development Network [CCEDNet]) lacked information about feminist organizations using enterprise as a way to resist exclusion. Over the years, my practicum students reviewed these websites as they developed case studies on minorities who ran social enterprise activities in their organizations and found many were absent on major network sites. Eduardo Pol and Simon Ville (Citation2009) have critiqued the over-usage of terms such as “innovation” and “social enterprise”; these buzzwords existed in the sector but were absent from the three organizations’ websites.

I noted with interest that these women leaders did not receive funding for their social enterprises. It was through this ongoing research project to understand the concept of innovation in a Canadian context for minorities that I first saw this difference. These women in different parts of the city were carrying out social enterprise projects, as was clear from my interviews, but they were doing so with an intention of ethics. There was a major disconnect between what they were doing and what donors knew about them, but it was evident that society could learn from them. In February 2020, two racialized women leaders in Toronto and Montreal and I were able to share with a room of federal policymakers how to make economic development politicized in a way that was ethical and race-conscious for minorities.Footnote7

The women leaders were not viewed as innovating in the social enterprise field, as women are normally viewed as carrying out social work. A Black feminist framework helped to pull out their lived experience as women in this sector and to understand why they approached economic development through politicized action. After much discussion, it was decided that it would be a good idea to spotlight these three GTA organizations as case studies for university students to better understand social enterprises among people of color using an intersectional feminist approach with the additional side-effect of educating policymakers on the value of these institutions in the innovation sector. As part of a provincially funded grant – the 2017 Early Researcher Award, “Social Innovations in Ontario” – the leaders of each organization were contacted to “freshen up” the data through telephone interviews by a doctoral research assistant to understand the social enterprises within these institutions, and human ethics clearance was approved.

THE CONTEXT OF INNOVATION IN THE ENTERPRISE SECTOR

People of color in the GTA have much to share about doing business differently, as depicted in the TVO documentary by Nina Beveridge (Citation2017), Village of Dreams. The film features Toronto’s Little India, a subset of Indian diaspora who organize their businesses much like a social enterprise. The term “social innovation” is generally defined as a retooling of how things are traditionally done to meet the needs of society. Sometimes the term becomes the exclusive use of technology firms and the STEM field. Hardly ever does the idea of social innovation center its analysis on race and racism (Bornstein Citation2004; Quarter, Mook, and Armstrong Citation2009; Bouchard Citation2013). This means that those socially conscious business owners focused on inclusivity in business and society are left out of the social innovation field (Cukier and Gagnon Citation2017a). The social economy field has defined what institutions count as a third sector organization. Are these family-run Indian businesses seen solely as small businesses and “for-profit”? Yet nonprofit organizations with an in-house business or community enterprises are eligible for social enterprise funding even if they fail to address equity issues in the society.

In November 2018, the Canadian federal government stated it would invest $800M into a social finance fund to stimulate innovation in the economy, and it is at the planning stage at the time of writing (see more at: https://sisfs.ca), however, this has been slow moving forward due to COVID-19 delays. Moreover, it is not clear who will access these resources. In 2015, the Provincial government in Ontario, Canada’s largest province, set up an initial fund valued at 4 million CAD for the Social Enterprise Development Fund (SEDF; Newsroom Ontario Citation2015; Ontario Innovation Agenda Citationn.d.).Footnote8 However, many of the recipient organizations in rounds one and two were entities that had close ties to well-positioned elites (Hossein Citation2017a).Footnote9 The list made obvious that the leaders receiving the funding were not the fire-brand “consciousness-raising” kind, nor were they themselves rooted in the most vulnerable communities because those engaged in radical work – and that involve for-profit businesses with a moral purpose – do not count as “socially enterprising.”

These preliminary findings are unsettling. It seems that non-white people in Toronto are not receiving these pockets of funding for social enterprise development. A 2017 report titled Immigrant Entrepreneurs supports the point that systemic barriers hold back racialized immigrant creativity in business, indicating the need to support their innovations. Growing bodies of work show that racialized innovators and entrepreneurs are increasing, yet much of the work they do is unknown, and this is a loss for the GTA (Cukier and Gagnon Citation2017a, Citation2017b).

A social innovation leader, a Canadian woman (who shall remain nameless) in Toronto’s west end Parkdale neighborhood, confided that she is blatantly undermined by funders because they want to use the funds to “train” her in how to introduce innovation to her own community despite her qualifications. Such testimonials are not rare in the white-led social services sector. The Ontario Nonprofit Network and the Mowat Centre (now defunct) in a report (Citation2013) highlighted the lack of racialized nonprofit directors. This data aligns with my empirical research that finds that Black Canadian nonprofit leaders are routinely ignored by donors and told that their work lies outside of the field of innovation (Hossein Citation2017a). In the summer of 2018, I interviewed a Black social entrepreneur from Downsview (Toronto’s west end) who was asked to submit criminal records before applying for any social enterprise grant, and he felt that he was negatively targeted (Interview, July 2018). Preliminary work suggests that there are gatekeepers who decide who counts as innovative in the enterprise sector.

FINDINGS: ETHICAL AND POLITICIZED ACTION FOR SOCIAL ENTERPRISES IN NONPROFIT ORGANIZATIONS

Over the years my work has shown that racialized people who create social enterprises, often with few resources, are overlooked, and their work is not considered social enterprise. In the following, I briefly describe the three social enterprises to give context to their work, to show how feminists are using social enterprises to fight inequity.Footnote10 The summaries of the organizations are themselves significant findings, necessitating one-on-one interviews, follow-up telephone interviews, and intense reviews of unpublished institutional materials and websites. Students in the placements shared ideas and mapped out details about the organizations, which are captured here. My research goal was to raise the profile of and to diversify the knowledge on social innovation and social enterprises. Thus the following leaders and organizations were selected: Lorraine Anderson, Executive Director of the Firgrove Learning and Innovation Community Centre (FLICC); Ginelle Skerritt, Executive Director of the Warden Woods Community Centre (WWCC); and Sunder Singh, former Executive Director of the Elspeth Heyworth Centre for Women (EHCW). All three institutions are registered as nonprofit organizations, and the executive directors are women of color who are accountable to a board. Social enterprise activities are part of the programming of all three organizations, and they were chosen because they attach an ethical approach to the way they carry out social enterprises.Footnote11

Lorraine Anderson and the FLICC

Formally established in 2008, FLICC was initiated in 2003–04 by a group of immigrant women who lived in the Jane and Finch community, a low-income area in the west end of Toronto (Ahmadi Citation2018). The women would gather at the center to socialize and to sew. With time, the informal group grew into a cooperative where many newcomers, single mothers, and low-income earners would meet to discuss sensitive topics around housing, jobs, and education (FLICC Citationn.d.a). As tenant representative at the time, Lorraine Anderson played a lead role in the group’s development and assisted them to push for improved living conditions. She was able to network with residents and allot resources from the Tenant Association budget to community-led initiatives (Interview, December 2017).

The FLICC mission was developed by the women, who defined it as “a safe, inclusive and holistic community space.”Footnote12 The Executive Director, single mother Anderson, is a long-time community member. She has the lived experience and expertise of being Black in a difficult economic environment. Her understanding of how to politically organize the women enabled her to recruit volunteers, since funds were limited for full-time staff persons. Under the leadership of Anderson and with the participation of residents, FLICC provides numerous programs, including after-school and daycare, library programs, sports and recreation for youth, youth camps, and meeting space for residents (Hossein Citation2017a).Footnote13 The women behind FLICC’s activities are able to mobilize resources and work with little public funding.

The Jane and Finch area has been the subject of disproportionately negative media stories, which focus exclusively on criminal activities (Do Citation2012). But Anderson and the cooperative group of like-minded women who wanted to see social changes operated together through FLICC to overturn biases against their community. She states,

Firgrove, it’s like a model of change we wish to see, and there can be hope … We are … important like anybody else in Toronto … I don’t know what other people think about Firgrove. But I know that we strive to do the best, and to showcase … the community as a positive place. (Interview, December 2017)

Ginelle Skerritt and the WWCC

WWCC is a nonprofit organization that adheres to the mission statement: “We exist to build caring, compassionate, just, and interdependent communities in southwest Scarborough” (WWCC Citationn.d.). WWCC’s Executive Director is a Black feminist, Ginelle Skerritt, who describes southwest Scarborough as a “microcosm of everything you can find in society” because there are people from all corners of the world encountering exclusion because of various identities (Interview, December 2017). In other words, the Warden Woods area has a wide range of income levels, significant ethnic diversity, and a mixture of newcomers and families who have resided in Canada for multiple generations. WWCC is committed to poverty reduction, and the center caters primarily to those who face income insecurities (WWCC Citationn.d.). For vulnerable groups, WWCC offers more than fifty services spread across nine offices in the east end of the city and reaches about 6,000 clients annually (WWCC Citationn.d.).

WWCC was founded by Mennonites in the 1970s. Its model was originally charity-based, as the institution relied on subsidies and grants to cover all of its operations and programming and treated the direct users as beneficiaries. Skerritt, hired as Executive Director in 2005, moved to a more business-like model, shifting the focus from a supplier-driven one to one motivated by the demands of residents in the community. She knew that constant cutbacks and the need to create radical programming would not attract donor funds, so she set out to find ways of making her nonprofit engage in several social enterprises.

She also read her community correctly: people who value certain services are willing to pay for them. Shifting away from a charity model,Footnote15 social enterprise appreciates the talents, skills, and voice of the people for whom these services are being created. When people pay, they are vested in the project, changing its power dynamics. Nonprofits no longer just “supply” goods but really have to think about the market demand and people’s wants. Singh, the director of EHCW, argues that social enterprise is about more than just making money and paying bills: “Social enterprise engages people. People have a sense of ownership” (Interview, November 2017). This focus affirms clients’ contributions and dignity. People are more likely to support projects that they have been brought into from day one, than those driven by an external party that tells them what to do. As Skerritt notes,

I thought that this [business approach] was the one thing that we needed to take on … because it would be a way of respecting the dignity and the contribution that people bring, and building on their strength, as opposed to assessing people according to what they didn’t have or couldn’t do, and needed to be fixed about them.Footnote16

The business model in many nonprofits have moved toward user fees, and many leaders like Skerritt have figured out ways to ensure fees remain low for the various clubs and the programs they value, such as Meals on Wheels. IRIE, a women’s collective group made of elderly West Indian grandmothers, did not receive government funding due to systemic issues. The women members of IRIE, with WWCC, made a conscious decision to raise funds and to sustain their activities. For example, the elders in the program organized a big fundraising gala with the support of WWCC staff, which boosted the program for a while (Skerritt, email discussion, November 28, 2019). This politicized action away from subsidies has made the group effective in supporting each other during complex times and also creating small revenue-making enterprises through baking and crafts so that they do not rely on any power structure. Today, IRIE receives provincial funding support from the Elderly Person’s Centre because Skerritt insisted and made it recognized as a program requiring such assistance.

The elders in IRIE continue to contribute by making a sorrel beverage, a tasty West Indian black cake, and crafts year-round to sell to the community at Christmas. This approach to business, one in which women are financially independent, is embedded in the culture of WWCC. In 2017, WWCC raised a total of $94,057 CAD through user fees and space rentals, and these funds help maintain provision of services and allow residents to contribute to the center’s programming, have a say in the quality of services, and encourage civic engagement (Skerritt, Interview, December 2017). The 2016–17 financial year saw $223,859 CAD generated through user fees (WWCC 2017). Implementing user fees tied to subsidies is thus an innovative way the organization has assured that its services have value for people; and people are willing to pay for it. The organization can also engage in activities that may be risky to donors to fund because it has its own resources to do so.

Sunder Singh and the EHCW

EHCW is a nonprofit organization that was established in Toronto in 1992. It is named after Elspeth Heyworth, a York University professor who led research in the community for poor women of color. EHCW’s head office is located on Finch Avenue, in Downsview (Toronto’s west end) community, with a satellite, the Blue Willow Activity Centre, in Vaughan, a suburb north of Toronto (EHCW Citationn.d.). The organization primarily serves newcomer and immigrant populations, with various services and programs catering to seniors, women, and youth. These include initiatives to address violence against women, reduce senior isolation, facilitate newcomer integration, and facilitate healthy development among youth (EHCW Citationn.d.). In addition, the center offers financial literacy training, job-search supports, and employment opportunities. Initially, EHCW focused on serving South Asian immigrants and residents; however, it has shifted over the years toward inclusive programming. According to the center’s Executive Director, Sunder Singh, “The organization is a very inclusive place. At Blue Willow, we have about sixteen to eighteen diverse communities participating … Every culture comes together” (Interview, November 2017).

The concept of social enterprise is in EHCW’s mission; and events are framed in terms of cost recovery and relevance to community needs. While EHCW accesses grants from various donors, diversifying revenue is one of the organization’s priorities, whether through fundraising, individual donations, or earned income from RivInt, a service that provides interpretation and translation services to a wide range of clients in the public and private sectors. Singh created RivInt after witnessing precarious funding issues and refusing to fall prey to them. . The money earned at the end of March 2017 totaled $320,300 CAD, with most of this coming from RivInt services (EHCW Citation2017). The profits of the social enterprise enable the organization to invest in new programming when there are no funding subsidies to do so.

EHCW’s social enterprise not only diversifies revenue, ensuring that the nonprofit is not left without resources, but it also carves out a space for autonomy for the community to experiment with new programming to better society and provides its mostly women translators paid employment. The freedom from being fully tied to government funding also ensures that the institution, made up of many feminists, has the resources to make provocative changes around unpopular social issues without having to adhere to government parameters. More importantly, the people who work for and depend on the organization’s services can be assured that, because they raise their own revenue, these services are focused on the people – that is, the needs of community members – as opposed to donors. Self-funding the project builds confidence and pride, and provides control over decision making in the community that is priceless to people who have experienced racial bias in the economy.

THE IMPORTANCE OF LIVED EXPERIENCE IN THE SOCIAL ECONOMY

Knowing as racialized women that white people hold power in their city, Anderson, Skerritt, and Singh viewed social enterprises as an important alternative for those otherwise excluded from economic development opportunities.Footnote18 I saw what these women leaders were doing clearly because Black feminist thought informed this analysis to show that Black women’s work, whether in the home or the economy, has always been political and focused on making resources accessible. And the project of making enterprise ethically-minded and in the interest of community is nothing new. In the past, people of color seeking funding for community projects but lacking contacts figured out ways to commercialize the work they did. For each of the women leaders described above, the commitment to entrepreneurial activities and cooperatives is rooted in their lived experience as racialized immigrant women. They bring a new lens to social enterprise development, as they know firsthand what it means to be “ethnic,” an “outcast,” a “minority,” and a “woman of color” in the business world. Through this sense of who they are and how they lived their lives, they are sensitive to the racial bias in business and society. They thus try experiments that shift away from negativity and trauma toward places of inclusion and goodness.

Anderson was born in Jamaica and migrated to Toronto in 1989. As a single mother of five children, she knew firsthand what struggle meant. She would participate in partner banks (informal banks) undertaken by Jamaicans in her community to help her access the money she needed, helping her buy her first car and house and pay her daughter’s tuition fees (Hossein Citation2017a). Anderson’s lived experience in Firgrove, her membership in the Action for Neighborhood Change, and her work as a board member of Jane-Finch’s Caring Village and a member of the Firgrove Tenant Association have all informed her approach to social enterprise development (FLICC Citationn.d.a; Anderson, interview, December 2017). Anderson chooses a community business model where it can make a difference:

I guess my motivation is giving back. I lived in the community and raised my children for over twelve years. I’ve seen some of the challenges, [and] some of the needs in the community that I can relate to as a past resident and also as a parent. (Interview, December 2017)

[I learned] from my own upbringing and the examples of people in my life who have been particularly entrepreneurial, like my grandmother … who raised me was a widow in her fifties. She raised five kids and had about three different businesses … She was a seamstress … She also ran a roti shop … and she was also a boarder … [W]hen we moved to Canada [from Trinidad and Tobago], she was doing homecare for kids … She helped a lot of young immigrant families at the time with childcare, and … in addition to reliable childcare, they got a home atmosphere, family. She was like their mother figure to the parents, and a grandmother to a lot of kids … I think that these lives have been very inspirational (for me). (Interview, December 2017; Hossein and Skerritt Citation2018)

Sunder Singh, who migrated to Canada from India in 1971, also brings lived experience as an immigrant woman. Early on, she learned that to survive in life one must be self-reliant:

What I had also learned through my life is not to depend on anyone. Anything that needs to be done, it has to be done by yourself … This is a lot of the values and beliefs that women bring from other countries. It’s a determination to succeed and do it without relying on others. My motivation was just that. (Interview, November 2017)

KNOWING THE LIMITS OF SOCIAL ENTERPRISE

Many scholars and practitioners have questioned the authenticity of social enterprise, arguing that it seems to mean different things to different people. The debate on social enterprise is often polarized between the left and the right. To many leftist people who support social enterprise, it is about co-opting resources to help those excluded from the mainstream market; to many of those on the right, social enterprise helps people engage in businesses that can eventually graduate into commercial markets. Some skeptics refuse to accept there is anything good about social enterprise development because of its association with the private sector. Others who refuse to accept social enterprise join the chorus for boot-strap development – where the poorest people must pay for services and the state will do less and less – because they see social enterprise putting the onus on these people. These are all valid critiques in considering whether some social enterprises benefit racialized people or not. Social enterprises clearly overlap with the private sector but there is no understanding what this means for non-white racialized people (Quarter, Mook, and Armstrong Citation2018).

One criticism that deserves attention refers to the seeming individualism or “guru-type figure” who is passionate about a cause rather than the social enterprises. Peredo and MacLean (Citation2006) make the compelling argument that individualized social enterprise is not neat and tidy and can be open to corruption if it is too aligned with one person’s ideas. What about those social enterprises that are owned by individuals? Not all social enterprises are individualized (Hart, Laville, and Cattani Citation2010; Quarter, Mook, and Armstrong Citation2018). For example, many cooperatives and credit unions (such as Meridian Credit Union or Desjardins’ caisses populaires) can be viewed as social enterprises, and these institutions are collectively owned by members.

The women leading these three very different organizations – Anderson, Skerritt, and Singh – are familiar with the various debates around social enterprise and they know the limits. They have used their own knowledge of community and lived experience to upset business systems, to draw upon what folks have always been doing, and make business caring. This is what squarely roots them in the DE literature and the ethical coordinates. They show the multiple dimensions of social enterprise, especially among people from faraway places, and bring a different set of norms and values, privileging not the mighty dollar, but social relations. What is important to note here as well is that the social enterprises in the organizations in this study focus on collective and community engagement. Social enterprises benefit people of color when they are group-oriented and embedded in the community.

ON OUR TERMS: MAKING SOCIAL ENTERPRISES RELEVANT

Many of the social enterprises developed by FLICC, WWCC, and EHCW serve newcomer and immigrant populations and other racialized groups. Their use of social enterprise is further enhanced because of the lived experience brought by the women who lead these organizations. They know that money, people’s voices, and resources affect societal change, addressing the wrath of exclusion politics among racialized people. In leading social enterprise projects within these institutions, each director takes an entrepreneurial approach to ensure the work is relevant to the communities they serve.

Firgrove residents have created several social enterprises over the years. The first attempt was the sewing and crafts cooperative group that nurtured friendship and provided a place where women could discuss politics, labor issues, tenant rights, childcare, and employment (Hossein Citation2017a). The women members also brainstormed ways to utilize their skills: through sewing, cooking, and cleaning. How could the women use the skills they have to earn money and at the same time reinvest in the community center? They carried out events and did fundraising through catering for the local community. As Anderson notes,

From the onset the whole idea (of Firgrove centre) was to create the sewing group as … a gathering for women. But the cooperative aspect of the group was the sustainable piece, because it helped them to think through how they could make money. (Interview, December 2017)

Another social enterprise that has proved successful for FLICC is the café. A café is not only a place where people can enjoy snacks and coffee but is a meeting spot for members. The women who are part of FLICC earn money while learning about self-reliance and comradery, as the group’s goal is to use business to uplift excluded people. The café provides nutritious and affordable meals, health education, and a space for residents to socialize. As the café develops and generates more revenue, it will reduce the funding dependency on donors and increase people’s own self-reliance. Anderson sees embedding a social enterprise as fundamental to the sustainability and care of people in the community:

Firgrove is to become self-sustaining. When I leave in the next couple years, it will be up to the residents to step in and continue on to be leaders and decision makers, and parents for the community … We don’t need a big corporation to do that. Just to give people the tools so that they can learn for themselves, to be self-sustained through their own ideas of innovation. (Interview, December 2017)

The whole point was to just get these women trained with skills … The hope was that they could go back to school if they wanted to do culinary skills, they could start their own business, or they could work in a business place. (Interview, December 2017)

Vesta Catering enterprise at Warden Woods is an initiative that emerged from women talking together, and they eventually came up with a business idea that would allow them to socialize and do something they knew they were good at: cooking. This grass-roots cooperation is reflected in the ethical coordinate of well-being of others. Skerritt reflects on the start-up of the Vesta Catering:

I think it was about 2009, and we had a group of women in the community who were … needing to talk about their lives. They had had marriages and relationships that didn’t work out, and so they were single moms [and] in some cases grandmas looking after grandchildren … They were meeting regularly, and … they started to think about ways that they could improve their situation … they wanted to look into was starting a business. So, they started brain-storming on what that business could be, and they thought, well, we … cook, so let’s start a catering business. (Interview, December 2017)

Another successful social enterprise, RivInt Interpretation and Translation Services (formerly Riverdale Interpreters), was started in 2000 as an initiative by the Ministry of Citizenship and Immigration, in partnership with the South Riverdale Community Health Centre, to help people start their own businesses. The idea of RivInt actually came from local people who lacked seed capital. Community members complained about language issues and finding suitable translators; Singh witnessed these struggles faced by non-English speaking persons, especially those speaking languages that are little-known in Canadian society, such as Punjabi, Hindi, Bengali, Swahili, Vietnamese, Mandarin, Tamil, Arabic, Persian, and African French. Consistent with EHCW’s aims, RivInt is a social enterprise developed by racialized women to assist newly arrived non-white immigrants. This social enterprise reduces isolation and promotes newcomer access and integration when they hire immigrant women to do the translation services.Footnote22

RivInt currently has over 900 interpreters and translators working in 112 different languages and dialects (EHCW Citationn.d.). The staff offer transcription, translation, and interpretation services on-site as well as over the phone to businesses and the nonprofit sector and are especially active in the healthcare sector in the GTA (EHCW Citationn.d.). As Singh shares,

Our basis of success was that we engaged the people … . The training we provided … had a special component, and that was customer service. Wherever the interpreters went, they had to provide the best service because they were representing RivInt. (Interview, November 2017)

POLITICIZE SOCIAL BUSINESS TO MAKE BUSINESS ETHICAL

Ethical coordinates are intuitively used by the racialized women leaders because they are concerned about equity and making just economies, and they bring added value to the community economies theory when they politicize what they do by refusing to conform to the corporatization of bankers who are deciding what social enterprise development should look like. These three women leaders have been transforming their communities through social innovations for decades, and they have shifted operations from a charity-based model into a social enterprise model to make the work they do sustainable and long-lasting.Footnote23 Staying accountable and mindful of the impact business is having on the people who live in these communities is at the very core of ethical societies (Gibson-Graham Citation2003). A politicized aspect in ethical economies is needed because it means not only creating social enterprises that will cover costs, be sustainable, and do good in the world but inserting a consciousness around racial equity – and this eye on racial equality is what is needed to make the economic possibility of Gibson-Graham’s work (Citation1996, Citation2006) matter in diaspora communities.

By and large, the social enterprise literature does not draw on theorizing to deal with racism and exclusion, and this reason is why racialized people experiment with new models (INCITE Citation2009; Hossein Citation2017a). This is why these cases matter; they show the setbacks faced by racialized people, especially women, and explain how a social enterprise can equalize business in society. This study documents social enterprises co-opting and politicizing business for racially excluded groups, and this should be the way to think about social enterprising work rather than the corporatization of the sector. These three nonprofits in the GTA are innovating in terms of making economies equitable through social enterprises, and this idea has not yet defined social enterprises.

CONCLUSION

Three anti-racist feminist community leaders face the routine challenge of securing funds to support and expand their services and programming as well as encountering the added stress of being a woman and racialized. For each of them, creating social enterprise means doing this work ethically but also politicizing the debate to ensure social enterprises are not run-of-the-mill businesses but actually uplift and change social dynamics for the better for racialized people. They, in quiet ways, subvert resources in ways to engage community economies, and they politicize the social economy in ways that we do not see within the social enterprise development sector. A feminist and race-conscious approach to co-opt resources for a politicized solidarity among racialized people is not new for these women and many racialized leaders in the solidarity economy. However, it is not known by those experts (read: white) defining social enterprise and making decisions on what counts as innovative. Social enterprise drawing on an anti-racist feminist approach to diverse community economies is a way to accumulate resources and to build new economies that are just and conscientious about people’s well-being.

Each of the women analyzed experiment with programs around controversial issues that they know are best for their community (ahead of the donors) because they are grounded in what community needs are (and not what donors want). The role that these feminists take on is what Korstenbroek and Smets (Citation2019) call antagonistic organizers, as they defy the rules to stay true to their activism. Having a social enterprise approach rooted in ethics and politicized action is part and parcel of running their nonprofits but also pushing for a more equitable society. Operating with a business-like approach challenges the presumption that racialized communities are passive recipients of support. Social enterprises also give the women the means to politicize issues that subsidies will not support but that they know is work that is needed to bring change. The members in each of these communities decide what businesses with a mission will look like on their own terms. They are the agents of their own development.

In Toronto, Firgrove café, Vesta Catering, and RivInt are three social enterprises that grew out of the needs of racialized people, many of them women, who wanted to engage in self-help projects together. These three women leaders shine a new light on what social enterprise looks like for racialized people because they are pushing for lived experience and equity to stay at the forefront of social and economic programs and refuse to be side swept by commercialized views of social enterprises. Social enterprise for racialized people is about doing business knowing full well that prejudice and bias exist in society and knowing that politicized economic solidarity to commercialize what they are doing while ensuring it is equitable and just also gives them added resources to do programming that matters to the people they serve.

For social enterprises to truly develop civic society and to bring value to society, they need an anti-racist feminist take on how to redo social enterprise programming. The diverse economies literature should make space for race and business exclusion and ensure that blindness to the work of racialized women in the field limits what we mean by rethinking community economies. Diverse community economies is limited if it does not push for racial equity, and social enterprise programs that do not incorporate an anti-racist feminism approach will perpetuate economic development that conforms to the status quo.

Racialized feminists engaged in the social economy are envisioning socially conscious businesses that are addressing racism in business.Footnote24 While there is important criticism of social enterprise on a broad level, social enterprises from the ground-up are innovating in business and have always been part of the lives of people of color who have relied on them from informal places. It is how they cope with alienation and exclusion from economics by the dominant society.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Sincere gratitude goes to Ginelle Skerritt, Lorraine Andersen, and Sunder Singh for the work they do building a new socially conscious form of social enterprises in Toronto. My York University students in the Business and Society program provided much assistance with these partners during their work placements. Research assistants Reena Shadaan and Semhar Berhe assigned to the Early Researcher Award titled Social Innovations in Ontario carried out interviews and drew up these case studies. This article was fortunate to have a review by Katherine Gibson of Western Sydney University. Many thanks to Paul Chamberlain of the Toronto Enterprise Fund who gave me a practitioner view on the employment social enterprise sector. Kunle Akingbola of Lakehead University was kind to discuss these issues with me during our luncheons on The Danny. I am thankful for the funds from the Early Researcher Award that made this research possible. Three anonymous reviewers went beyond the call of duty as reviewers to give me the courage I needed to articulate my feminist theorizing in the social enterprise sector.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Caroline Shenaz Hossein

Caroline Shenaz Hossein is Associate Professor of Business and Society in the Department of Social Science, Faculty of Liberal Arts and Professional Studies at York University, Toronto, Canada and founder of the Diverse Solidarity Economies Collective (DiSE Collective).

Notes

1 American political scientist Cedric Robinson (Citation1983) used the term “racial capitalism” given the evidence of racism against African Americans in business because capitalism is not “neutral” but there to benefit white privilege.

2 See more about the projects at Environics examining social exclusion in society at https://www.environicsresearch.com/insights/environics-research-survey-finds-emerging-leaders-experiencing-racism-andor-discrimination-past-year/.

3 I emphasize the work of the women for decades because junior racialized people who are seemingly better connected politically will access resources over these qualified racialized women; the resources are squandered and misused because of inexperience.

4 I paraphrase and pare down the ethical coordinates to four key ones.

5 Adapted from Westley’s (Citation2013) definition of Si. See also The Young Foundation TEPSIE report (2012) that considers identities and resilience as part of social enterprise work.

6 I confirm that all personal information that would allow the identification of any person(s) described in the article has been removed. In the instances where the person(s) is identified, they have given permission for personal information to be published in Feminist Economics.

7 Ginelle Skerritt of Warden Woods Community Centre and Indu Krishnamurty of Microcredit Montreal led a training with me to federal policymakers on February 6, 2020 on how to rethink feminist approaches to community economic development.

8 Senior Manager at MaRS, interview, March 18, 2015; Senior officer, SEDF, Toronto, interview, April 7, 2015.

9 Scarborough-based nonprofit, interview, February 4, 2015; Jane/Finch Family Community Centre, interview, February 27, 2015.

10 The FLICC and WWCC cases are described in detail in Hossein (Citation2017a).

11 The findings and description are focused on these programs rather than on the entirety of what the organizations do (although a synopsis is given for context).

12 See “About” section of FLICC website.

13 A series of ongoing discussions over a long period (2013–19; Anderson, interview, December 2017).

14 Donors include: Painters and Allied Trades Union, the Geoffrey H. Wood Foundation, the Hospital for Sick Children, the City of Toronto, the Toronto Community Housing Corporation, Frontier College, York University, the Toronto Public Library, York Woods Library, Northwood Neighbourhood Services, the United Church Jane-Finch Community Ministry, and the Kingsview Women’s Group

15 For more on this, see Yunus (Citation2010).

16 Skerritt, interview, December 2017.

17 See United Way Toronto and York Region website, unitedwaytyr.com/list-of-agencies.

18 See Hossein (Citation2017a) for details on the directors at FLICC and WWCC.

19 Skerritt in conversation with the author for many years on this point.

20 See “Vesta Caterers Menu” on WWWC website.

21 “Community Impact Report Card,” unpublished document.

22 RivInt Interpretation and Translation Services. See https://www.seontario.org/stories/rivint-interpretation-and-translation-services/.

23 At the time of final revisions of this paper it was learned that FLICC’s building was destroyed by a fire in March 2020, and the community was considering how to fundraise to rebuild.

24 See the development of Diverse Solidarities Economies (DiSE) Collective out of Toronto in Canada and Trivandrum, Kerala in south India.

References

- Ahmadi, Donya. 2018. “Diversity and Social Cohesion: The Case of Jane-Finch, a Highly Diverse Lower-Income Toronto Neighbourhood.” Urban Research and Practice 11(2): 139–58. doi: 10.1080/17535069.2017.1312509

- Akingbola, Kunle. 2015. “When the Business is People: The Impact of A-Way Express Courier.” In Social Purpose Enterprises: Case Studies for Social Change, edited by Jack Quarter, Sherida Ryan, and Andrea Chan, 52–74. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Alexander, Anne. 1997. The Antigonish Movement: Moses Coady and Adult Education Today. Toronto: Thompson Educational.

- Amin, Ash. 2009. The Social Economy: International Perspectives on Economic Solidarity. London: Zed Books.

- Austin, David. 2013. Fear of a Black Nation: Race, Sex and Security in Sixties Montreal. Toronto: Between the Lines.

- Beveridge, Nina, dir. 2017. Little India: Village of Dreams. Beevision and Hive Productions: TVO, Toronto.

- Bittencourt, Claudia, Diego Antonio Bittencourt Marconatto, Luciano Barin Cruz, and Emmanual Raufflet, ed. 2016. “Introduction to Special Edition Social Innovation: Researching, Defining and Theorizing Social Innovation.” Mackenzie Management Review 17(6): 14–9. doi: 10.1590/1678-69712016/administracao.v17n6p14-19

- Bornstein, David. 2004. How to Change the World: Social Entrepreneurs and the Power of New Ideas. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Bouchard, Marie J, ed. 2013. Innovation and the Social Economy: The Quebec Experience. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Brouard, Francois, J. J. McMurtry, and Marcelo Vieta. 2015. “Social Enterprises Models in Canada: Ontario.” Canadian Journal of Nonprofit and Social Economy Research 6(1): 63–82.

- Cherney, Elena and Paul Vieira. 2017. “Police Charge Suspect for Murder in Quebec Mosque Attack.” Wall Street Journal, January 30.

- Community Meets Opportunity. 2017. “Annual Report, 2016–17.” Private Report of Warden Woods Community Center, Scarborough, Ontario. https://wardenwoods.com/en/.

- Cukier, Wendy and Suzanne Gagnon. 2017a. “Social Innovation: Shaping Canada’s Future.” Report for SSHRC. Diversity Institute, Ryerson University.

- Cukier, Wendy, and Suzanne Gagnon. 2017b. Immigrant Entrepreneurs: Barrier and Facilitators to Growth. Report for the Ontario Government. Toronto: Ted Rogers School of Management’s Diversity Institute, Ryerson University.

- Davis, Bridgett M. 2019. The World According to Fannie Davis: My Mother’s Life in the Detroit Numbers. New York, NY: Little, Brown and Company.

- Do, Eric Mark. 2012. “Crime, Coverage and Stereotypes: Toronto’s Jane and Finch Neighbourhood.” JSource: The Canadian Journalism Project.

- Elson, Peter and Peter Hall. 2012. “Canadian Social Enterprises: Taking Stock.” Social Enterprise Journal 8(3): 216–36. doi: 10.1108/17508611211280764

- Elspeth Heyworth Centre for Women (EHCW). 2017. “Annual Reports and Financial Statements, Annual Report, 2016–17.” https://ehcw.ca/what-we-do/ehcw.ca/who-we-are/annual-reports-and-financial-statements/.

- Elspeth Heyworth Centre for Women (EHCW). n.d. “What We Do.” https://ehcw.ca/what-we-do/ (accessed February 2020).

- Firgrove Learning and Innovation Centre (FLICC). n.d.a. “Home.” https://firgroveflicc.wordpress.com/ (accessed February 2019).

- Firgrove Learning and Innovation Centre (FLICC). n.d.b. “Takes a Village.” Brochure, Private Library Documents of FLICC. https://firgroveflicc.wordpress.com/ (accessed February 2019).

- Galabuzi, Grace-Edward. 2006. Canada’s Economic Apartheid: The Social Exclusion of Racialized Groups in the New Century. Toronto: Canadian Scholars Press, Inc.

- Gibson, Katherine, Rini Astuti, Michelle Carnegie, Alanya Chalernphon, Kelly Dombroski, Agnes Ririn Haryani, Ann Hill, et al. 2018. “Community Economies in Monsoon Asia: Keywords and Key Reflections.” Asia Pacific Viewpoint 59(1): 3–16. doi: 10.1111/apv.12186

- Gibson-Graham, J. K. 1996. The End of Capitalism (As We Knew It): A Feminist Critique of Political Economy. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

- Gibson-Graham, J. K.. 2003. “Enabling Ethical Economies: Cooperativism and Class.” Critical Sociology 29(2): 123–61. doi: 10.1163/156916303769155788

- Gibson-Graham, J. K.?>. 2006. A Postcapitalist Politics. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Gibson-Graham, J. K., Jenny Cameron, and Stephen Healy. 2013. Take Back the Economy: An Ethical Guide for Transforming Our Communities. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Harding, Sandra. 1987. “Introduction: Is There a Feminist Method?” In Feminism and Methodology: Social Science Issues, edited by Sandra Harding, 1–13. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Hart, Keith, Jean-Louis Laville, and Antonio David Cattani. 2010. The Human Economy. Cambridge: Policy Press.

- Hossein, Caroline Shenaz. 2017a. “A Black Perspective on Canada’s Third Sector: Case Studies on Women Leaders in the Social Economy.” Journal of Canadian Studies 51(3): 749–81. doi: 10.3138/jcs.2017-0040.r2

- Hossein, Caroline Shenaz.. 2017b. “A Case Study of the Influence of Garveyism on the African Diaspora.” Social Economic Studies Journal 66(3/4): 151–74.

- Hossein, Caroline Shenaz?>, ed. 2018. The Black Social Economy: Exploring Diverse Community-Based Markets. New York City: Palgrave Macmillan Press.

- Hossein, Caroline Shenaz and Ginelle Skerritt. 2018. “Drawing on the Lived Experience of African Canadians: Using Money Pools to Combat Social and Business Exclusion.” In The Black Social Economy in the Americas: Exploring Diverse Community-Based Markets, edited by Caroline Shenaz Hossein, 41–58. New York City: Palgrave Macmillan.

- INCITE! Women of Colour Against Violence. 2009. This Revolution Will Not Be Funded: Beyond the Non-Profit Industrial Complex. Boston: South End Press.

- Institute for New Economic Thinking. 2019. “Learn the Language of Power.” Narrated by Ha-Joon Chang. https://www.ineteconomics.org/perspectives/videos/learn-the-language-of-power.

- K’nife, K’adamwe, Allan Bernard, and Edward Dixon. 2011. “Marcus Garvey the Entrepreneur? Insights for Stimulating Entrepreneurship in Developing Nations.” King Street: Journal of Liberty Hall 76(2): 37–59.

- Korstenbroek, Timo and Peer Smets. 2019. “Developing the Potential for Change: Challenging Power Through Social Entrepreneurship in the Netherlands.” VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 30(1): 475–86. doi: 10.1007/s11266-019-00107-6

- Lewis, Rupert. 1987. Marcus Garvey: Anti-Colonial Champion. Kent: Karia Press.

- Martin, Tony. 1976. Race First: The Ideological and Organizational Struggles of Marcus Garvey and the Universal Negro Improvement Association. Dover, MA: Majority Press.

- Mendell, Marguerite. 2009. “The Three Pillars of the Social Economy: The Quebec Experience.” In The Social Economy: Alternative Ways of Thinking About Capitalism and Welfare, edited by Ash Amin, 176–209. London: Zed Books.

- Menendian, Stephen, Elsadig Elsheikh, and Samir Gambhir. 2018. “Inclusivity Index: Measuring Global Inclusion and Marginality.” Annual Report, Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society, University of California, Berkeley.

- Mensah, Joseph. 2010. Black Canadians: History, Experience, Social Conditions. 2nd ed. Halifax: Fernwood Publishing.

- Monsebraaten, Laurie. 2019. “Those Who Toil in Low-Wage Jobs in the GTA More Likely to be Visible Minorities.” Toronto Star, November 26.

- Nicholls, Alex, Julie Simon, and Madeleine Gabriel, eds. 2015. New Frontiers in Social Innovation Research. Hampshire, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Government of Ontario. 2015. “Ontario Investing $4 Million to Help Social Enterprises Grow.” Newsroom, Government of Ontario. https://news.ontario.ca/opo/en/2015/02/ontario-investing-4-million-to-help-social-enterprises-grow.html.

- Ontario. n.d. “Seizing Global Opportunities: Ontario’s Innovation Agenda.” Ministry of Research and Innovation, Government of Ontario. http://docs.files.ontario.ca/documents/334/ontario-innovation-agenda.pdf.

- Ontario Nonprofit Network. 2013. “Shaping the Future: Leadership in Ontario’s Labour Force.” Report, The Mowat Centre, University of Toronto. http://theonn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/ONN-Mowat-Shaping-the-Future-Final-Report.October2013.pdf.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). 1999. Social Enterprises. Policy Document. Paris: OECD.

- Pearce, John. 2009. “Social Economy: Engaging as a Third System?” In The Social Economy: International Perspectives on Economic Solidarity, edited by Ash Amin, 22–33. London: Zed Books.

- Peredo, Anna Maria and Murdith MacLean. 2006. “Social Entrepreneurship: A Critical Review of The Concept.” Journal of World Business 41(1): 56–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jwb.2005.10.007

- Pol, Eduardo and Simon Ville. 2009. “Social Innovation: Buzz Word or Enduring Term?” Journal of Socio-Economics 38(6): 878–85. doi: 10.1016/j.socec.2009.02.011

- Quarter, Jack, Laurie Mook, and Ann Armstrong. 2009. Understanding the Social Economy: A Canadian Perspective. 1st ed. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Quarter, Jack, Laurie Mook, and Ann Armstrong. 2018. Understanding the Social Economy: A Canadian Perspective. 2nd ed. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Quarter, Jack, Sherida Ryan, and Andrea Chan. 2015. Social Purpose Enterprises: Case Studies for Social Change. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Reynolds, Graham. 2016. Viola Desmond’s Canada: A History of Blacks and Racial Segregation in the Promised Land. Toronto: Fernwood Publishing.

- Rizza, Alanna. 2017. “Father of Toronto Cop Charged in Dafonte Miller Case Removed from Professional Standards Unit.” Toronto Star, December 19.

- Robinson, Cedric J. 1983. Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition. 2nd ed. London: Zed Press.

- Rudin, Ronald. 1990. In Whose Interest? Quebec’s Caisses Populaires, 1900–1945. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- Shragge, Eric and Jean-Marc Fontan. 2000. Social Economy: International Debates and Perspectives. Montreal: Black Rose Books.

- Stapleton, John. 2019. The Working Poor in the Toronto Region: A Closer Look at the Increasing Numbers. Report. Toronto: Metcalf Foundation.

- Stein, Judith. 1986. The World of Marcus Garvey: Race and Class in Modern Society. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

- Taylor, James B. 1970. “Introducing Social Innovation.” Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 6(1): 69–77. doi: 10.1177/002188637000600104

- Thompson, John and Bob Doherty. 2006. “The Diverse World of Social Enterprise: A Collection of Social Enterprise Stories.” International Journal of Social Economics 33(5/6): 361–75. doi: 10.1108/03068290610660643

- Toronto Foundation. 2017. “Toronto’s Vital Signs.” Report 2017/18, Toronto Foundation. https://torontofoundation.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/TF-VS-web-FINAL-4MB.pdf.

- van Staveren, Irene and Zahid Pervaiz. 2017. “Is It Ethnic Fractionalization or Social Exclusion, Which Affects Social Cohesion?” Social Indicators Research 130: 711–31. doi: 10.1007/s11205-015-1205-1

- Warden Woods Community Centre (WWCC). n.d. “Warden Woods Community Centre: Where Community Meets Opportunity.” https://wardenwoods.com/en/ (accessed February 2020).

- Westley, Frances. 2013. “Social Innovations and Resilience: How One Enhances the Other.” Stanford Social Innovation Review: Informing and Inspiring Leaders of Social Change 11(3): 6–8. https://ssir.org/articles/entry/social_innovation_and_resilience_how_one_enhances_the_other.

- World Bank. 2017. “Population.” https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL.

- YFile. 2017. “Member of Parliament Awards Business & Society Students Enrolled in Experiential Education Class.” YFile, York University’s News, March 28. https://yfile.news.yorku.ca/2017/03/28/member-of-parliament-awards-business-society-students-enrolled-in-experiential-education-class/.

- Young Foundation. 2012. “Social Innovation Overview: A Deliverable of the Project: The Theoretical, Empirical and Policy Foundations for Building Social Innovation in Europe.” TEPSIE, European Commission, 7th Framework Programme, Brussels.

- Yunus, Muhammad. 2010. Building Social Businesses: The New Kind of Capitalism That Serves Humanity’s Most Pressing Needs. New York City: PublicAffairs.