?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This study shows that occupations in South Africa are segregated and stratified by gender. While some women (mostly Black and “Coloured”) overwhelmingly fill low-paying jobs, others (mostly White and Indian/Asian, but also Coloured) tend to fill higher-paying professional positions. This paper finds evidence of a long-term reduction in gender segregation and stratification, with women and men entering occupations previously dominated by the other gender, although this trend is sensitive to several data considerations. Most recent evidence, however, points to stagnation in this process. Distinct worker characteristics by gender – including education, location, or age – cannot explain the existing segregation or women's overrepresentation in low-paying jobs, compared with men's representation. They do partially explain the overrepresentation of women in some higher-paying positions and the declining stratification of the labor market by gender. Education is the primary driver for upward mobility for women and gender equality in the South African labor market. Note: This study follows the current South African government’s usage of the racial category “Coloured,” with the caveat that the term is not in acceptable use outside South Africa.

HIGHLIGHTS

Gendered occupations and pay gaps in South Africa have not been adequately studied.

Black women suffer double labor segregation in South Africa, by gender and by race.

Post-apartheid progress in reducing labor segregation has been faster by gender than by race.

Improved education offers women a route to better-paid professional occupations

Although women now access better jobs, managerial positions remain disproportionately male.

JEL:

INTRODUCTION

South Africa stands out for having a dysfunctional labor market. Employment rates are especially low among women and the Black/African population, falling below the average level in OECD countries and in other developing countries, including Brazil, India, and China (Arnal and Förster Citation2011). The apartheid regime left South Africa with large racial inequalities in labor market outcomes, such as employment rates and wages (Rospabé Citation2002), occupational attainment (Treiman, McKeever, and Fodor Citation1996), and segregation (Gradín Citation2019), as well as in poverty (Gradín Citation2013a). The system segmented the entire South African society according to race, granting unequal access to land, public services, education, and skilled jobs, among many other life spheres. The different racial categories included the most privileged group of people of European ancestry (“White”) on one extreme, and the majority and most unprivileged group (“Black/African”), comprised of different Bantu peoples, such as Zulu, Xhosa, or Tswana, on the other. In the middle rung were two groups: people of Indian/Asian ancestry, mostly descendants of indentured laborers; and people of mixed race, including descendants of the Khoi-San aboriginal population or former Malay slaves (“Coloured”). In post-apartheid South Africa, the national statistical agency (Statistics South Africa) continues to use these four racial categories in the national data it gathers and publishes, including the census. (A fifth category, “other,” is also included.) As this analysis is based primarily on South African census data, its terminology and racial categories reflect those used in the source data.

Apartheid had dramatic effects in the domain of gender equality, too. Its migrant labor system forced Black men to temporarily leave their villages to work in cities or in the mining industry, while women and children were left in the rural areas, which helps to explain higher poverty among female-headed households driven by their higher concentration in rural areas and fewer working-age adults (Gelb Citation2004). Because of this disruption of family life, many women had to fulfill the roles of both breadwinner and caregiver in the challenging circumstances of high unemployment and HIV/AIDS prevalence, with very limited economic opportunities (Budlender and Lund Citation2011).

Several factors, such as lower marriage rates, increasing access to higher education, and the implementation of nondiscriminatory legislation after the end of apartheid (for example, the Employment Equity Act 1998), produced a growing feminization of the labor force that, however, also led to an increase in women's unemployment and self-employment in the informal sector (Casale and Posel Citation2002; Posel Citation2014). Compared with men, South African women still face lower employment rates (Leibbrandt et al. Citation2010) and receive lower wages (Burger and Yu Citation2007; Wittenberg Citation2014), neither of which is fully explained by their different endowments. Not surprisingly, the situation of women in the labor market varies widely along racial lines.

The literature on gender inequalities in post-apartheid South Africa has so far analyzed in detail the extent, patterns, and drivers of the employment and wage gaps (Winter Citation1999; Hinks Citation2002; Grün Citation2004; Oosthuizen Citation2006; Ntuli Citation2007; Shepherd Citation2008; Casale and Posel Citation2010; Bhorat and Goga Citation2013; Kimani Citation2015). At this stage, however, we know much less about the changes in the distribution of occupations by gender, especially in the long run. A couple of analyses of occupational attainment (Rospabé Citation2001) and of occupational segregation (Parashar Citation2008) for the initial post-apartheid years and using aggregate occupational classifications are exceptions.

The aim of this paper is, precisely, to analyze the post-apartheid trends in the distribution of occupations by gender in South Africa, focusing on two key aspects (segregation and stratification), following a similar approach that Carlos Gradín (Citation2019) previously applied to the racial dimension. Gender segregation indicates the extent to which women and men tend to work in different occupations, regardless of the characteristics of jobs filled in by each gender. Gender stratification indicates the extent to which jobs are stratified in earnings by gender, for example, with women systematically working in jobs with lower pay. In the absence of discrimination against women, one would expect to find similar proportions of women and men across occupations, and whenever differences exist (for example, induced by differences in preferences given prevalent social norms), there is no reason to expect systematically lower pay for women, especially after controlling for differences in characteristics (for example, education) that women and men bring to the labor market.

I will show that gender segregation and stratification across occupations were quite high immediately following the apartheid era but seem to have been substantially reduced from1996 to 2007, although the intensity of the decline from 2001 to 2007 is sensitive to some data considerations. Both trends have, however, stagnated in more recent years. Gender segregation and stratification cannot be generally explained by differences in education or other relevant characteristics of men and women workers. Also, I do not find evidence supporting that this declining trend followed the various policy reforms aimed at increasing equality in the labor market. Education turns out to be the most important factor that helps women to mitigate their segmentation into low-paying jobs and its relevance has grown over time. Furthermore, I will discuss the interplay between gender and race in configuring the South African labor market. By comparing women and men within each population group, I will show the distinctive over-representation of Black women in low-paying jobs, as opposed to the higher presence of White and Indian/Asian women in professional occupations, with Coloured women found between both extremes. In summary, these results indicate that women in post-apartheid South Africa continue to be disadvantaged in terms of access to better paying jobs, with some women partially compensating for this disadvantage by outperforming men in terms of education.

GENDER AND LABOR MARKET OUTCOMES IN SOUTH AFRICA

Earlier studies done after apartheid ended in South Africa, including those by Carolyn Winter (Citation1999) or Sandrine Rospabé (Citation2001), showed substantial gender inequalities in labor market outcomes such as employment, occupational attainment, and wages. These inequalities could barely be explained by gender differences in endowments of productive characteristics and exhibited different patterns across population groups. Regarding inequalities in employment, Morné Oosthuizen (Citation2006) found a decreasing role of gender in explaining the probability of employment from 1995 to 2004 (while the same result did not apply to race) consistently with higher feminization of the labor force. But, a gender gap remains in employment rates. In this line, Esther Kimani (Citation2015) has recently shown, using survival analysis, that the probability of exiting unemployment is lower for women than for men if the exit is into employment, but higher when exiting into economic inactivity. Furthermore, higher education increases the hazard rate of women into employment more than for men, as earlier studies had already pointed out.

Some studies also reported lower earnings among women than among men, the differential being only partially explained by endowments, using the first post-apartheid labor force surveys (Winter [Citation1999] and Hinks [Citation2002], using the South Africa October Household Survey [OHS] 1994 and 1995, respectively). The gender gaps in earnings increased between 1995 and 1999 (Ntuli Citation2007). Debra Shepherd (Citation2008) showed that the gender wage gap declined after 1999, largely driven by the increasing number of White women entering higher-skilled occupations and industries. Different patterns by race were identified. For example, White women were more affected by direct wage discrimination, whereas Black women were found to increasingly suffer from discrimination at the hiring stage (Grün Citation2004). The gender wage gap tends to be higher at the bottom of the wage distribution – evidence of a sticky floor, especially for Black women (Ntuli Citation2007; Shepherd Citation2008; Bhorat and Goga Citation2013). Paradoxically, the gap also tends to be higher in the union sector, after controlling for sorting by gender in union and nonunion employment (Casale and Posel Citation2010).

The occupational distribution by sex has been identified as an important driver of changes in the gender wage gap in many other countries (Groshen Citation1991; Bayard et al. Citation2003; Amuedo-Dorantes and de la Rica Citation2006; Brynin and Perales Citation2015). This has led to an important branch of research interested in examining the unequal distribution of men and women across occupations over time (for example, Blau, Brummund, and Liu [Citation2013] for the US, or international comparisons in Anker [Citation1998], or Anker, Melkas, and Korten [Citation2003]). Despite its relevance, research on this topic has been very limited in South Africa in terms of scope and time span. Sandrine Rospabé (Citation2001) used a multinomial logit model to estimate the gender gap in occupational attainment, meaning the probability of working in a high-skilled, skilled, or semi-skilled/unskilled occupation (based on the 1-digit classification of occupations) with the 1999 October Household Survey. Women were found to be overrepresented in the two extreme categories. While their larger presence at the top was fully explained by their individual characteristics, their overrepresentation in the lowest category remained entirely unexplained in the early post-apartheid years. Sangeeta Parashar (Citation2008) provided the only (to my knowledge) quantification of occupational segregation by gender in South Africa. Using the 2001 census, she measured the dissimilarity index to be 0.437 (2-digit classification). Unlike the situation in the US, this level was lower than in the case of race (0.572 between Blacks and Whites).

METHODOLOGY: MEASURING SEGREGATION AND STRATIFICATION

Occupational gender segregation means that men and women work in different occupations. The unequal distribution of occupations is aggravated by stratification when one gender, typically women, generally works in low-paying occupations (women's low-pay segregation).

Let and

indicate the number of women and men in the workforce, and

and

the corresponding numbers working in occupation

, where occupations have been sorted in ascending proportion of men,

, or equivalently by

. If

,

is the relative frequency of each gender (proportion of all male or female workers in occupation

), then

, is the corresponding cumulative value for the

occupations with the largest overrepresentation of women. When occupations are, instead, indexed by their average earnings (

), the relative and cumulative frequencies are labeled as

and

. In measuring these gender inequalities in the South African labor market, I use two distinct types of tools following Carlos Gradín (Citation2019, Citation2020).

On one hand, the segregation and concentration (or low-pay segregation) curves plot the cumulative proportions of women (horizontal axis) and men (vertical axis) when occupations are indexed by the proportion of males (segregation) and by average earnings (concentration), respectively. That is, the segregation curve maps for each

, while the concentration curve maps

for each

. These curves play the same role as the Lorenz and concentration curves in the measurement of income inequality. In the case of absence of segregation, when men and women work in the same proportion across all occupations, both curves correspond with the line of equality (the diagonal).

The segregation curve falls between the diagonal and the horizontal axis, the latter indicating the case of maximum segregation: there are only workers of one gender in each occupation. If two segregation curves do not cross each other, this indicates that the one below unambiguously shows higher segregation (for a large set of segregation indices consistent with a small set of value judgements).

The concentration curve can fall between the segregation curve and its mirror image above the diagonal. In the range in which it falls below the diagonal, it indicates that women tend to be segregated into low-paying occupations compared with men below any low-pay threshold in that range, meaning there is (restricted) first-order stochastic dominance in the occupational distributions by gender. If it falls above the diagonal, however, it indicates the contrary: high-pay segregation of women. The further this curve is from the diagonal (the closer to the segregation curve or its mirror image), the more stratified the distribution of occupations by gender. Non-crossing curves reveal the highest level of low-pay/high-pay segregation in the one furthest from the diagonal.

On the other hand, I use the dissimilarity and Gini segregation and concentration (low-pay segregation) indices to quantify these phenomena and assess the trends over time even if the corresponding curves cross. The Gini indices of segregation and concentration are measured as twice the area between the line of equality and the segregation and concentration curves, respectively. It is the average (among women) of all the vertical distances between the diagonal and the segregation curve: , where the hat indicates the midpoint between two adjacent occupations:

. Similarly, the Gini index of concentration measures women's low-pay segregation as the average distance between the diagonal and the concentration curve, adding the area below and subtracting the area above the diagonal,

.

The dissimilarity index of segregation measures the proportion of women that should shift from female- to male-dominated occupations to eliminate segregation and can also be defined as the maximum possible distance between and

:

. This maximum value is reached at the last occupation for which women are overrepresented. The corresponding concentration (or low-pay segregation index) indicates the proportion of women that should shift from their current occupation to another with higher average earnings to eliminate women's segregation into low-paying jobs (for any possible threshold defining low pay),

. Therefore, the two dissimilarity indices represent the maximum (absolute) vertical distance between the diagonal and the segregation and concentration curves, respectively.

Dissimilarity and Gini indices are very strongly related. The dissimilarity index of segregation is the Gini index in the simplified situation in which all occupations are aggregated into two groups: those dominated by men and those dominated by women. The Gini segregation index thus deviates from the dissimilarity index because it also considers inequality in the distribution of occupations by gender within the sets of male- and female-dominated occupations (not only between the two types of occupations).

All these indices range in absolute terms between 0 and 1, with higher values indicating more segregation or stratification. While the segregation indices are always non-negative, the sign of the concentration indices indicates whether stratification of women is into low-pay (positive) or high-pay (negative), with their absolute values bounded from above by the corresponding segregation indices. The concentration ratios measure the proportion of segregation that is low-pay by dividing each concentration index by its maximum (the segregation index): ,

.

I will measure the observed level of (low-pay) segregation (that is, unconditional) but also the conditional level that remains after equalizing the observed characteristics (education, age, etc.) of men and women, by giving one gender the characteristics of the other. The level of (low-pay) segregation that goes away after this equalization is the aggregate compositional effect, that is, the level that can be explained by men and women having distinct characteristics. For that, I follow Carlos Gradín (Citation2013b) and estimate a counterfactual distribution in which I reweight the sample of women to reproduce the distribution of characteristics of men (and the other way around) based on their propensity score. In line with John DiNardo, Nicole M. Fortin, and Thomas Lemieux (Citation1996), the reweighting factors are obtained by estimating with a logit model the probability of being male based on individual characteristics described in the data section. Then, sample weights of women with a higher probability of “being male” (given their characteristics) will be increased relative to women with a lower probability.

The contribution of each set of characteristics can be obtained in a second stage. I start with all logit coefficients set to zero. I then estimate a sequence of reweighting factors in which the coefficients associated with each factor are progressively switched on (changed from zero to their estimated values). The change in (low-pay) segregation before and after the corresponding coefficients are switched on indicates the contribution of that factor. Because this contribution depends on the order in which factors are introduced (path-dependency problem), I compute the average overall possible sequences, known as the Shapley decomposition (Chantreuil and Trannoy Citation2013; Shorrocks Citation2013).

Finally, a similar exercise is used to decompose changes in (low-pay) segregation over time into changes in characteristics of each gender and changes in their respective conditional employment distributions.

DATA

The analysis uses the 1996 and 2001 South Africa censuses and the 2007 Community Survey (Statistics South Africa) from IPUMS (Minnesota Population Center Citation2015). Other previous censuses lack reliability, and the 2011 census did not codify occupation. The universe refers to the working population not living in group quarters, 15–65 years old, employed, and not in the armed forces (1,727,981 observations). Separate analysis is made by population group, following the apartheid-based classification that had long-lasting consequences: Black/African (69 percent of workers in 2007), White (16 percent), Coloured (11 percent), and Indian/Asian (4 percent). The occupational IPUMS classification is based on the 3-digit ISCO88, with 125 categories, including one for workers with unknown occupation (16 percent in 2007, 7 percent in censuses). The analysis is complemented by using labor force surveys (LFS) compiled in The South Africa Post Apartheid Labour Market Series, 1994–2015 (PALMS v3.1; Kerr, Lam, and Wittenberg Citation2016). The online appendix discusses some relevant issues regarding the codification of jobs. In general, the LFS tend to underrepresent the share of domestic helpers compared with the censuses.

The ranking of occupations in IPUMS is obtained using contemporary average annual income (interval midpoints). In PALMS, I used median real earnings after some adjustments and imputations (Gradín Citation2019). These monetary variables have a large number of zeros, but the rankings of occupations (the relevant information in this approach) are highly correlated among data sources and with the one ranking occupations by worker skill composition. Thus, stratification can be interpreted to be either into low-paying or into low-skilled jobs indistinctly. Conditional segregation using IPUMS is estimated controlling for location (area of residence and province), educational attainment, immigration (status and years residing in current dwelling), marital status, and other demographic variables (race, age, and disability). The analysis with PALMS omits immigration and disability due to the lack of information.

OCCUPATIONS AND GENDER

Gender patterns in the distribution of occupations

I first briefly describe key features of the distribution of occupations by gender and how they changed over time, considering that during the analyzed period there was an increasing feminization of employment (See Figure A1 in the online appendix, under the Supplemental Materials tab), from 38 percent of women in 1994 to 45 percent in 2015, according to LFS. This increase was more moderate according to the census, from 42 percent in 1996 to 44 percent in 2007. The evolution in occupations with the largest misrepresentation of women is reported in Tables A1–3 in the online appendix. Using a detailed classification of occupations, we can still recognize the gender pattern that was already identified in earliest years using more aggregated occupational groups in 1999 (Rospabé Citation2001). Figures A2 and A3 in the online appendix draw the trends for the main occupational groups by race.

South African women tend to be largely overrepresented among elementary, low-paying occupations, especially as domestic helpers and cleaners, street vendors, or housekeepers (all with an average income below 50 percent of the 2007 median). However, women are also overrepresented at the middle of the occupational distribution (50–150 percent of the median), in clerk occupations (for example, tellers, office, or client information clerks), and at the top (above 150 percent of the median) in occupations such as professionals or technicians (teachers, nurses, etc.). Conversely, the largest underrepresentation of women occurs among mid-paying jobs, such as driving, building, protective services, and mining, at the top of the earnings distribution in managerial positions, and among physicists and engineers. Some of these gender gaps seem to be quite persistent over time, although, as explained below, there was a substantial reduction in the gender gap in the proportion of domestic workers (based on the census). This picture hides large racial inequalities interplaying with gender, though.

There is no doubt that race is even more important than gender when it comes to determining representation in these occupations. White and Indian/Asian women have a much higher representation in skilled occupations (managers and professionals), while Coloured women and, especially, Black women tend to be overrepresented at the bottom of the skills distribution (elementary occupations). When compared with men of the same race, Black women clearly tend to be more overrepresented in elementary occupations than women of any other race, while the same is true for White women as professionals, which helped to reduce the gender wage gap (Shepherd Citation2008), although White women are still underrepresented as managers. In all cases, these gender gaps seem to have been reduced over time.

A relevant fact that most certainly and critically affects the results in segregation analysis is the large discrepancy between census and LFS data regarding the evolution of women in the massively woman-dominated occupation: 913 Domestic service (Figure A4 in the appendix). Although both data sources give us similar figures for the total and by main population groups in 2007 (19 percent census versus 21 percent LFS; 27 percent versus 26 percent for Blacks), censuses show higher figures in 1996 (29 percent versus 23 percent LFS; 43 percent versus 34 percent Blacks) and 2001 (25 percent versus 21 percent LFS; 36 percent Blacks versus 27 percent). Therefore, there is a sharp reduction of the gender gap in this important occupation in the census, but a much smaller one in the LFS. Both datasets exhibit problematic issues here. The reduction observed with census data between 2001 and 2007 may be overestimated, given the larger share of workers with unknown occupations in 2007 (17 and 15 percent of women and men respectively, Table A5). The LFS might be underestimating this important occupation with respect to the census and have large discontinuities in the series (for example, in 1995 or between 1999 and 2000). For these reasons, I primarily rely on the census data to assess the long-term trend, while running some sensitivity analysis on how to deal with the unknown category, but I keep using the LFS, primarily to describe the most recent trend, in which I expect data to be more comparable over time.

Changes after major policy reforms

With the aim of investigating whether there was a significant change in the proportion of (Black) women in top occupations (managers and professionals) after years of major policy reforms (the 1998 Employment Equity Act, the 2003 Black Economic Empowerment Act, and the 2007 Codes of Good Conduct), provides a difference-in-difference linear model. The results do not support the existence of any improvement if other worker characteristics are controlled for. In fact, there is a small negative and statistically significant effect (increasing gap after the reform) when Black women are compared with Black men before and after 2003 or 2007. These effects are slightly larger when we compare women and men of any race and are robust to the removal of the problematic earlier observations (before 2000). Only if other worker characteristics are not considered and only if observations after 2000 are used is there a small positive effect for all women and no effect for Black women. The effects are also negative and even larger for 1998, but in this case the data issues might be more relevant. These results indicate that, conditional on worker characteristics, the gender gap in the access to top occupations tends to increase rather than decrease after the different reforms. This is consistent with the analysis in the following sections pointing at women's attained education as the main driver of gender equality in the South African labor market.

Table 1. Difference-in-difference model: proportion of women in managerial/professional occupations

TRENDS IN GENDER OCCUPATIONAL SEGREGATION

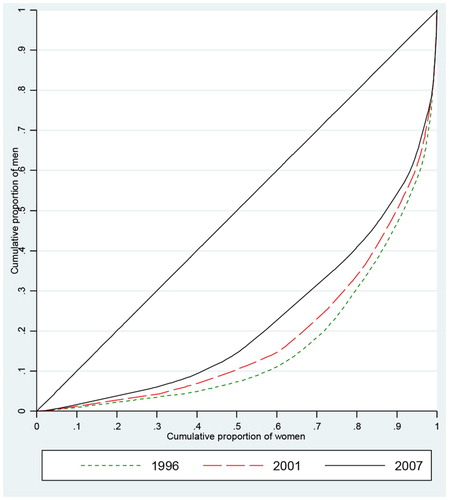

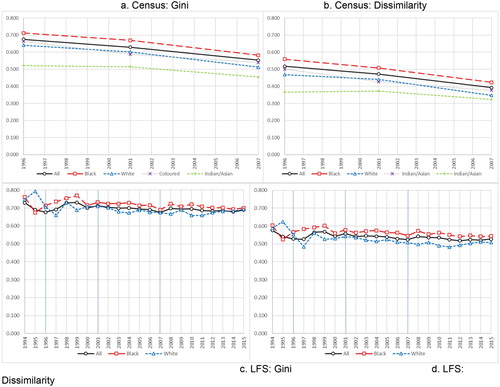

Gender segregation across occupations declined between 1996 and 2007 based on census data (a, 1b), with an 18 percent reduction with Gini, 24 percent with the dissimilarity index. The higher reduction with the latter reveals an intense desegregation between female- and male-dominated occupations ( indicates the level of segregation between these two sets of occupations). Indeed, there was a substantial increase in the proportion of women and men entering occupations that were initially dominated by the other gender (the unknown category excluded) between 1996 and 2001: from 22.7 percent to 25.6 percent (women) and from 19.7 percent to 23.8 percent (men). Between 2001 and 2007 there was a modest increase for women (to 26.5 percent) and decline for men (20.8 percent), but these figures are clearly underestimated given the larger share of the unknown category.Footnote1 On the contrary, there was no reduction over time in the Gini within the sets of occupations dominated by one gender (that is, the difference between Gini and dissimilarity:

). Gender segregation declined with similar intensity across all population groups if women are compared with men of their own race, except for a smaller reduction among Indians/Asians (12–13 percent).

Figure 1. Gender occupational segregation indices.

Source: Own construction based on IPUMS and PALMS.

This general trend contrasts with the smaller decline in racial segregation (Black versus White) estimated over the same period (Gradín Citation2019): about 11 percent, with an increase between 1996–2001 and a decline between 2001–2007. In fact, the levels of gender and racial segregation were very similar in 1996 with Gini, but the former became 8 percent smaller than the latter in 2007. Similarly, gender segregation was about 4 percent higher than racial segregation in 1996 with the dissimilarity index, but 11 percent smaller in 2007, consistent with Sangeeta Parashar (Citation2008) using the 2-digit classification in 2001. The level of gender segregation in 2007 was still high, however, with a Gini of 0.553 and a dissimilarity index of 0.393, higher among Blacks than among any other group (0.582, compared with 0.540 for the Coloured group, 0.512 for Whites, and 0.454 for Indians/Asians). This hierarchy in gender segregation among population groups was nearly constant over time (except that segregation for Whites was slightly above that of Coloured people in 2001).

The decline in gender segregation in the census is robust to the choice of indices because it is corroborated by the segregation curves getting closer to the diagonal over time (). This implies that most known segregation indices would point in the same direction. These gender segregation curves over time (Figure A5) do not overlap for Blacks either, but there is some overlapping at the bottom for Whites between 2001 and 2007, which indicates no robust improvement in that case because indices more sensitive to occupations in which men are more strongly underrepresented could point at an increase in gender segregation. There is also a crossing in the curves for Coloured people between 2001 and 2007, in this case at the top, while there are several crossings in the curves for Indians/Asians.

A note of caution is, however, needed when assessing these trends due to the large and variable proportions of workers with unknown occupations over time. Different assumptions about the actual occupations of these workers may have a substantial impact on the segregation trend. For that reason, I now consider four possible scenarios as alternatives to the one considered previously, in which the unknown category was treated as if it were only one occupation. In the first of these scenarios, I entirely remove workers with unknown occupations from the sample, which is equivalent to assuming that their distribution across occupations is the same as for the rest of the sample, conditional on gender. In an intermediate second scenario, I fix the proportion of unknown workers of each gender as in 1996 (and treated as one occupation), with the increase/decrease in 2001 and 2007 redistributed across the other occupations, conditional on gender. In a third and last alternative, I split workers with unknown occupations into two completely segregated occupational categories, one entirely made up of men and another with only women in it, thus assuming the worst-case scenario in terms of dissimilarity. In the last scenario, I implicitly impute the occupation of these workers based on their observed characteristics, using a similar reweighting procedure as the one used to estimate conditional segregation.Footnote2

The robustness results (Table A20) show that the decline in segregation between 1996 and 2001 or 2007 is quite robust to the different assumptions about the occupations of those in the unknown category. The decline between 2001 and 2007, however, would be substantially smaller if the distribution of occupations in the unknown category or its changes over time did not differ much from the rest. If these occupations or changes over time are highly segregated instead, it could be that segregation was constant or even increased between 2001 and 2007. Interestingly, implicitly imputing occupation based on observed characteristics (through reweighting, alternative four) produces results almost identical to the case in which workers with unknown occupations are assumed to have the same occupational distribution as the other workers (by removing them from the sample, alternative one).

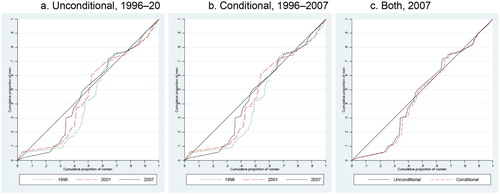

The LFS data point to a much higher persistence of gender segregation in the long term than the census data (c–d), something that can be partially explained by the data issues discussed in the previous section, especially the underestimation of domestic helpers in the initial years. We only observe about 1 percent reduction with both indices either for the 1996–2007 period covered by the census or for the entire 1994–2015 period. The largest reduction between the highest and lowest pick years is still below 10 percent. Other classifications show similar trends (see Tables A6–7).

Looking at the entire LFS trend, we see that after a short decline in the mid-1990s, segregation appears to fluctuate around its average values of near 0.700 for Gini or 0.540 for dissimilarity. This trend suggests a high persistence of gender segregation in the most recent years, when the series should be more reliable and comparable over time. With LFS, we also find that segregation tends to be smaller by gender than by race (about 6–7 percent on average), and higher among Blacks than among Whites, although the gap tends to be much smaller than was found with census data and seems to have narrowed in most recent years. The trends for all groups are reported in Tables A8–15.

Working women and men differ to some extent in their characteristics (Table A4). For example, according to the 2007 Community Survey, working women tend to be less likely than men to be married (49 percent versus 61 percent), Indian/Asian, or Black, and generally have attained higher education (42 percent with secondary school and 9 percent with a university degree, compared with 38 and 7 percent of men). More working women are in middle-aged groups and live in rural areas or in Eastern and Western Cape or KwaZulu-Natal (and a lower proportion in Gauteng or North West). Table A16 shows gender differences in education by population group. Table A17 reports the logit regressions using census data. These differences result from the combination of gender differences in the working-age population and a strong sorting of women into employment. I will estimate segregation conditional on gender differences in these observable characteristics, but, unlike some of the traditional wage gap decompositions, the available methodology (based on reweighting) does not allow to control for potential selection bias caused by unobservable traits, especially among women who have the lowest employment rates. My analysis is thus conditional on men and women having a job.Footnote3

Altogether, differences in observable characteristics by gender explain virtually nothing of their occupational segregation in any year and population group, however. Only between 0 and 2 percent of Gini or dissimilarity segregation goes away after equalizing the characteristics of both genders (that is, women are given the distribution of characteristics of men), while keeping their conditional occupational distributions in South Africa according to census data. This applies to all population groups and is not much different with the dissimilarity index (Table 3). The proportion of segregation explained is only slightly higher (2.1 percent) if, instead, I give women the male conditional distribution across occupations (while keeping their own distribution of characteristics). I reweight the male sample to reproduce women's characteristics.

The explained proportions are even smaller in the case of LFS (Table A19).Footnote4 This (smaller) percentage of segregation explained by characteristics might be slightly underestimated as a result of not considering the different field of degree of college workers of each gender, as done in the case of the US (Gradín Citation2020, where the total Gini segregation explained rose from 1.7 to 7.1 percent after including that variable, using a similar approach). But it seems that gender segregation in every year has little or nothing to do with worker-distinct characteristics by gender. In contrast, about 29 percent of Gini racial segregation in 2007 in South Africa was directly associated with differences in observed characteristics between Blacks and Whites (Gradín Citation2019).

A different issue is to what extent changes in characteristics of men and women over time may have contributed to the declining trend in gender segregation. There was a general improvement in attained education over time, as well as an increase in the proportion of Black men and women, as well as unmarried or older women, for example. The evolution in the explained component (difference between unconditional and conditional terms, Table 3) indicates that characteristics might have played a very limited role. However, this trend is influenced by changes in the distribution of male characteristics and changes in the conditional employment distributions of both genders. In order to evaluate a pure compositional effect (with constant conditional employment distributions), I use a similar decomposition exercise (Table 4). First, I estimate the counterfactual segregation in 2001 when each gender keeps the initial distribution of their characteristics in 1996. The difference between segregation in 2001 and in the counterfactual provides an estimate of the impact of the change in characteristics on segregation, evaluated using the conditional employment distributions of both genders in the final year. A similar exercise can be done keeping constant the final characteristics instead (evaluating the change with the initial conditional distribution), and the same applies for the change between 2001 and 2007. The results confirm a small overall compositional effect over times: only between 4.5 and 13.7 percent between 1996–2001, and between 7.4 and 11.1 percent between 2001–2007, depending on what characteristics are kept constant. However, this reflects an important contribution to the decline by changes in education (0.014–0.015 or about 19 and 30 percent of the decline in the first and second period, respectively), more than offset by changes in the distribution of other characteristics (especially, race and age) (Tables and ).

Table 2. Gender segregation indices, decomposition

Table 3. Decline in gender Gini segregation index over time, decomposition

OCCUPATIONAL STRATIFICATION BY GENDER

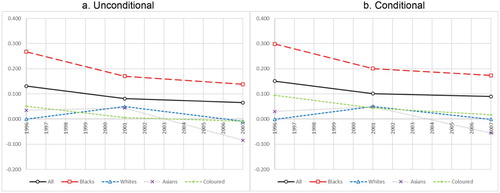

The previous section demonstrated that the labor market in South Africa is segregated along gender lines, but this does not consider the quality of the occupations that women and men hold. The concentration curve crossing the diagonal from below in 2007 () reflects the large overrepresentation of women at the bottom of the earnings occupational distribution, but also in occupations at intermediate positions. This is consistent with previous findings for 1999 highlighted by Sandrine Rospabé (Citation2001) using a much more detailed classification of occupations and different years. The cumulative proportion of women in the least-paying occupations is larger than that of men up to the level in which both groups accumulate about 44 percent of workers (when the concentration curve crosses the diagonal, indicating restricted stochastic dominance up to that point).

It is in the nature of gender segregation that we find more striking differences across population groups. Black women, and, to a lesser extent, Coloured women, are clearly overrepresented in the lowest-paying occupations in 2007 compared with men of their own races (their concentration curves fall below the diagonal at the bottom of the distribution: see Figure A6a–b in the appendix). This is the result of the importance of (low-paying) female domestic helpers in these two groups, 26 and 15 percent respectively, compared with only around 1 percent of White and Indian/Asian women discussed above. On the contrary, it is men who are overrepresented at the bottom of the occupational earnings distribution in the case of Whites and, especially, Indians/Asians. The concentration curves for women of these groups fall above the diagonal at the bottom (Figures A6c–d in the appendix). However, the bottom has a different meaning for these two groups in terms of average income; it is equivalent to the set of occupations at the middle range of income for the other groups. There are only marginal proportions of Whites and Indians/Asians of any gender in occupations with average incomes below 50 percent of the median.

The concentration curves of the different years overlap, but there is some reduction in the stratification of women (and of Blacks) at the very bottom of the distribution between 1996 and 2001 at the country level, but an increase between that year and 2007.Footnote5 For the rest of the distribution of occupations, however, the concentration curve gets close to the equality line. Therefore, to draw a conclusion on the overall trends, we must rely on the indices of concentration that aggregate these contradictory changes.

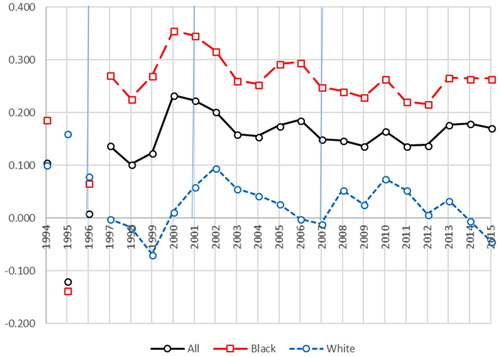

The Gini measure of concentration exhibits positive values, indicating that, overall, if we consider any possible low-pay threshold, there is stratification by gender, with women segregated into relatively low-paying occupations, but with a clear downward trend over time (around 50 percent reduction with Gini; see a in the appendix). However, due to the changes in the concentration curves above, had we relied on indices more sensitive to the very bottom of the distribution, stratification would have increased between 1996 and 2007 (for example, computing the Gini for a restricted range of low-paying occupations).

Figure 4. Gini concentration index (census).

Source: Own construction based on IPUMS. Women compared with men of the same population group.

Thus, the labor market is not only less segregated by gender, but also the remaining segregation implies less stratification (except for the bottom): the low-pay segregation Gini ratio decreased from 19 percent in 1996 to 12 percent in 2007 (in contrast with the increase from 90 to 95 percent over the same period in the case of race reported in Gradín [Citation2019]).Footnote6,Footnote7 The reduction in stratification between 1996 and either 2001 or 2007 is robust to different alternative ways of dealing with workers with unknown occupations (Table A21). However, this is not the case in the reduction between 2001 and 2007, which is not robust to the removal from the sample of the category of workers with unknown occupation. In the case in which the occupation of these workers is implicitly imputed by reweighting based on their characteristics, both concentration indices actually increased.

The analysis of stratification by population groups (women compared with men of the same population group) reveals interesting facts. Overall, the distribution of occupations seems to be only strongly stratified by gender in the case of Blacks; it is roughly neutral for the Coloured and White groups (the concentration Gini index is around zero), while Indian/Asian women tend to be more clearly segregated into high-paying occupations (the low-pay index is negative). The areas between the concentration curve and the diagonal falling above and below the latter cancel out for the White and Coloured categories, but their situation is different (as revealed in Figures A6b–c). While Coloured women tend to be overrepresented at the bottom, this is compensated for by a higher overrepresentation in the middle. In the case of Whites, it is men who are overrepresented at the bottom (equivalent to the middle for Coloured or Black people), but this is compensated for by their overrepresentation in occupations with higher earnings. This means that Coloured women along with Black women are segregated in low-paying occupations if we restrict the measure to the bottom 30 percent of women in the worst-paying occupations. The value of Gini would be positive (0.041), although still below the corresponding value for Blacks (0.066) and in contrast with the negative levels obtained for Whites (−0.030) and Indians/Asians (−0.039) in that case.

The trends over time of these population groups also differ. Black and Coloured women improved their situation over time, especially between 1996 and 2001. For example, the concentration Gini ratios for Black women decreased from 38 percent of segregation in 1996 to 24 percent in 2007, and for Coloured women from 8 to 2 percent. Between 1996 and 2001, White women exhibited an increase in their low-pay segregation (from nearly zero), and Indians/Asians a smaller increase. Between 2001 and 2007 these two groups reduced their low-pay segregation, with Indians/Asians becoming more clearly segregated into high-paying jobs (about 19 percent of segregation is of this type).

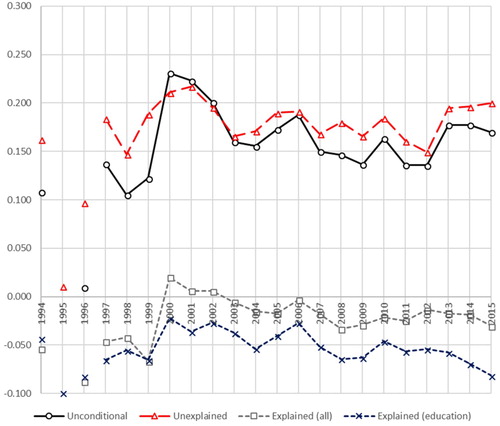

The trend with LFS () shows an increase of women's Gini low-pay segregation between 1994 and 2000 (excluding the outlier 1995 observation displaying negative values), which might be explained by the data issues in the LFS during the first years discussed above. It also shows an (oscillating) decline since 2000 (consistent with the 2001–07 reduction observed in the census). This generally reflects the trend for Blacks, but not for Whites. The latter exhibited a decline in low-pay segregation until 1999, followed by an increase until 2002, and another decline afterwards, becoming negative in the last two years (which implies high-pay segregation). In the case of the dissimilarity index, low-pay segregation also shows a long-term decline (2000–09) followed by stagnation in most recent years.

Differences in characteristics taken together do not explain why South African women tend to be overrepresented in low-paying occupations. In fact, with similar characteristics by gender, we would expect to observe a level of stratification about 37 percent higher with the Gini index in the case of the 2007 Community Survey (compared with 16 and 25 percent in the previous years).Footnote8 Table 6 reports the detailed decomposition for Gini (see Table A18 for dissimilarity). This proportion is smaller in the LFS (12 percent in 2007, 18 percent in 2015, ). c suggests that there are only minor changes in the concentration curves after conditioning on characteristics. The area below the diagonal increases, while the area above decreases. That is, only part of the overrepresentation of women in middle-/high-paying occupations can be explained by their characteristics, but neither their large overrepresentation at the bottom nor their underrepresentation in some top occupations.

Figure 6. Gini concentration index (LFS): unconditional and conditional.

Source: Own construction based on PALMS.

The different distribution of men and women by marital status (with a lower proportion of married women compared with men) increasingly explains significant proportions of women's low-pay segregation (Gini index: 16 percent in 1996, 36 percent in 2007). An additional 8 percent can be explained in 2007 by the larger proportion of women living in rural areas (as opposed to a negative contribution in the other years, when the proportion of working women living in urban areas was higher than for men). But these effects are more than compensated for by a much stronger and increasing negative impact of education (−21 percent in 1996, −83 percent in 2007), which prevents women from being even more segregated into low-pay occupations. The LFS show an increasing (negative) contribution of education over time since 2000 (Figure 9; detailed decomposition in Table A19).

This is also the situation of Black women. Their characteristics in 2007 prevented low-pay segregation from being higher (−26 percent), especially due to education (−42 percent), more than compensating for the positive effects of marital status (10 percent), age (5 percent), or area of residence (2 percent). All the high-pay segregation of White and Coloured people, and one-third of that of Indian/Asian people can be explained by the women's distinct characteristics, education being the most important. Coloured women would be segregated into low-paying occupations if they had men's characteristics. These facts indicate that education has become an effective way for women of all population groups to scale up in the pay distribution, compensating for their disadvantaged situation with respect to men.Footnote9 This effect has been intensified over time.

Another way of assessing the relevance of characteristics is to again measure their contribution to the trend in stratification using a constant conditional employment distribution (Table 7). Indeed, most of the reduction in stratification is the result of changes in the composition of characteristics of each gender over time, especially due to education, with a larger contribution than in the case of segregation. As in the case of segregation, though, the effect of education is partially offset by changes in the composition by other characteristics (race and age in both periods, marital status in the first one, and area of residence in the second one). This is especially true between 2001 and 2007 (85–91 percent of the decline is accounted for by changes in characteristics). The compositional effect accounts for 36–70 percent of the decline between 1996 and 2001 as well (Tables and ).

Table 4. Gini concentration index, decomposition

Table 5. Decline in gender Gini concentration index over time, decomposition

HETEROGENEITY IN SEGREGATION AND SEGMENTATION BY GENDER

The above analysis demonstrates that the South African labor market is segmented by gender, and that the extent and trend of this segmentation varies with race. Now I analyze other potential sources of heterogeneity. In all cases, women are compared with men of the same group.

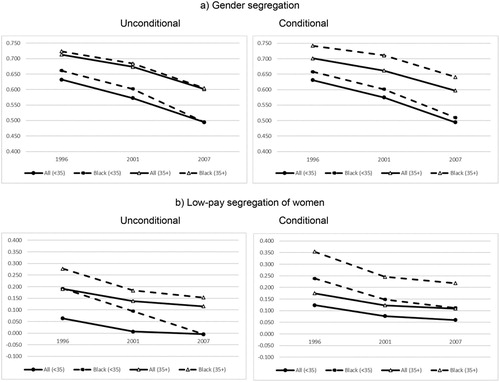

Figures a–b show segregation and stratification trends by age (below or above 35 years old) using the census data to assess whether younger cohorts face a less segmented labor market. The graphs on the left side show the observed (unconditional) levels; the graphs on the right show the levels conditional on characteristics, that is, after equalizing the characteristics of men and women within each age group.

The results for workers of any race confirm that gender segregation is lower and declined faster for younger women. The lower segregation of younger women remains even after equalizing characteristics among men and women in their corresponding age group, indicating that this is not due to their different composition by education or marital status. In the case of stratification, the difference by age is larger. The segregation of young women into low-paying jobs was already small in 1996 and vanished in 2007 (slightly negative values). Older women are more strongly segregated into low-paying jobs, with a substantial reduction over time, but this segmentation did not vanish. The differences by age, in this case, are much smaller after equalizing characteristics by gender in each age group (conditional case). This indicates that education does make younger women less overrepresented in low-paying jobs, changing the nature of their segregation.

Figures a–b also show that a similar age pattern (with generally higher values) is found for Black women, although the decline in low-pay segregation for the younger women seems to be more pronounced than in the case of the overall population, especially in the last period. Furthermore, the age gap in low-pay segregation seems to be larger even after controlling for other characteristics (meaning the reduction in the age gap due to education is smaller than for other racial groups).

Similarly, I explore the presence of heterogeneity in the levels and determinants of gender stratification of the labor market by area of residence, marital status, and age group in 2007 (). Unconditional segmentation of women in low-paying jobs is largest among rural and divorced or widowed women and increases with age. Conditional on characteristics, segmentation is largest among middle-aged (aged 45–54), widowed, and rural women, though. The results also indicate that the mitigation of low-pay segmentation through education is largest, as one could expect, among urban, single, and younger women (when compared with men of the same characteristics) ().

Table 6. Gini concentration index by characteristics, 2007, decomposition

CONCLUDING REMARKS

In this paper, I analyzed gender inequalities in the distribution of occupations in post-apartheid South Africa, making the most of the limited and often problematic available data sources: the census and a series linking different labor force surveys. Although South Africa is a very special case due to its complexity in terms of history and demographics, this analysis also contributes to the understanding of segregation in developing countries, for which the research is much scarcer.

The analysis primarily relied on census data to assess the long-term trend and found a substantial decline in the level of segregation of occupations by gender. This went along with a reduction in the level of stratification between 1996 and 2001, with the change between 2001 and 2007 being not robust to data considerations due to the large presence of workers with unknown occupations. Gender segregation has, however, been shown to be more persistent in recent years, and, to a lesser extent, also stratification, using the LFS. This trend contrasts with a relative lack of progress in terms of racial segregation/stratification over the same period highlighted by the literature. Race and gender, however, interplay in determining the composition of employment, with the consequences of apartheid being especially noticeable among Black women. Stratification by gender implies that some women (especially Black and Coloured women) persistently hold lower-paying jobs, like domestic helpers or cleaners, while other women (especially Indian/Asian, White, and Coloured women) increasingly fill higher-paying positions, especially in professional jobs, but are less successful in reaching managerial positions.

I have found no evidence that this segregation and stratification by gender, now or in the past, was the result of the distinctive characteristics of men and women workers, especially attained education. Hardly any segregation can be justified on these terms, and only the overrepresentation of women in some higher-paying professional positions may partially be justified by their higher education and other attributes. But this is not the case with their overrepresentation at the bottom of the pay scale or their underrepresentation in managerial jobs, which remains after controlling for differences in characteristics by gender. That is, men and women with similar characteristics still tend to work in different occupations, with a tendency for some (Black and Coloured) women to work in lower-paying jobs compared to men with similar human capital. Outperforming men in education, however, is revealed to be women's most effective way out of being trapped in low-paying jobs, especially for White and Indian/Asian women, but also for Coloured women, allowing them to achieve professional occupations even if they are kept out of jobs with the highest responsibilities. This has been the main driver of gender equality in the South African Labor market, especially in terms of women's access to better jobs.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (1.6 MB)SUPPLEMENTAL DATA

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2021.1906439

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Carlos Gradín

Carlos M. Gradín is Research Fellow at UNU-WIDER, Finland, and Professor of Applied Economics (leave of absence) at University of Vigo, Spain. He holds a PhD in Economics (Autonomous University of Barcelona), and his main research interests are the study of poverty, inequality, and discrimination in developed and developing countries, with a special interest in inequalities between population groups (that is, by gender, race, or ethnicity). His research has been published in specialized journals including The Journal of Economic Inequality, Review of Income and Wealth, Feminist Economics, Review of Household Economics, Journal of Development Studies, Regional Studies, Journal of African Economies, and Industrial Relations.

Notes

1 If workers in the unknown category are completely removed from the sample or that category is treated as a male-dominated occupation in 1996, the increase would be larger in the case of women (24.1, 27.5, 31.8 percent in the first case; 28.6, 32.6, 43.3 percent in the second one), while there would be little difference for men (21.5, 25.45, 24.4 percent; the same as above in the second case).

2 I created two samples for each gender and year, one with workers with a known occupation, the other one with all workers. In a first stage, I estimated the probability of a worker belonging to the latter sample based on characteristics using a logit model. Then, I constructed new weights based on their predicted probabilities. Finally, segregation was computed using the sample with workers with known occupation, reweighted to reproduce the distribution of characteristics of the entire sample.

3 Conditional segregation compares men and women with the same characteristics. It is the potentially unequal correlation between unobservable and observable characteristics by gender that might be more problematic.

4 Except in 1995 (5 percent with Gini and 9 percent with dissimilarity, due to the misrepresentation of some groups already mentioned).

5 This is, however, the result of a slight change. The worst-paying occupation with a sizeable number of workers in 2001 was a male-dominated one, 921 (agricultural, fishery and related laborers). It was followed by two largely female-dominated occupations: 913 (domestic and related helpers, cleaners, and launderers), and 911 (street vendors and related workers) – with an integrated one, 614 (forestry and related workers), in the middle. In 2007, the worst-paying significant occupations were all female-dominated, such as 621 (subsistence agricultural and fishery workers), and the above-mentioned 913 and 921 (men are overrepresented in 912 [shoe cleaning and other street services], but much smaller).

6 The dissimilarity ratio, instead, was rather constant: 44 percent in 1996, 41 percent in 2001, and 44 percent again in 2007. This results from the fact that the main improvement in terms of stratification did not occur at the bottom of the earnings distribution where the largest gap between both cumulative distributions (meaning, the dissimilarity index) was obtained.

7 If we disregard comparability issues, this means that occupations are more segregated and to a larger degree stratified in the US than in South Africa (Gradín Citation2020), although the figures are much closer if we restrict the analysis to Black South Africans. In 2007 segregation in the US was 0.682 (Gini) and 0.512 (dissimilarity); the concentration was 0.204 (Gini) and 0.200 (dissimilarity), that is, respectively 30 and 39 percent.

8 Stratification would be about 28 percent higher with the alternative counterfactual in which I give women the male conditional distribution across occupations.

9 The effect of education might be overestimated given the lack of information about field of college degree, as women tend to specialize in fields with lower average earnings (see Gradín Citation2020). However, the impact would be smaller in South Africa, as only 9 percent of women and 7 percent of men had a university degree in 2007. The advantage of women is larger in secondary education (42 percent versus 38 percent).

REFERENCES

- Amuedo-Dorantes, Catalina, and Sara de la Rica. 2006. “The Role of Segregation and Pay Structure on the Gender Wage Gap: Evidence from Matched Employer-Employee Data for Spain.” The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis and Policy 5 (1): 1–34. doi: 10.1515/1538-0645.1498

- Anker, Richard. 1998. Gender and Jobs: Sex Segregation of Occupations in the World. Geneva: International Labour Organization.

- Anker, Richard, Helinä Melkas, and Aailsa Korten. 2003. “Gender and Jobs: Gender-Based Occupational Segregation in the 1990s.” Working Paper 16, InFocus Programme on Promoting the Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work, International Labour Office.

- Arnal, Elena, and Michael Förster. 2011. “Growth, Employment and Inequality in Brazil, China, India and South Africa: An Overview.” In Tackling Inequalities in Brazil, China, India and South Africa: The Role of Labour Market and Social Policies, edited by Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, 13–55. Paris: OECD.

- Bayard, Kimberly, Judith Hellerstein, David Neumark, and Kenneth Troske. 2003. “New Evidence on Sex Segregation and Sex Differences in Wages from Matched Employee-Employer Data.” Journal of Labor Economics 21 (4): 886–922. doi: 10.1086/377026

- Bhorat, Haroon, and Sumayya Goga. 2013. “The Gender Wage Gap in Post-Apartheid South Africa: A Re-Examination.” Journal of African Economies 22 (5): 827–848. doi: 10.1093/jae/ejt008

- Blau, Francine D., Peter Brummund, and Albert Yung-Hsu Liu. 2013. “Trends in Occupational Segregation by Gender 1970–2009: Adjusting for the Impact of Changes in the Occupational Coding System.” Demography 50 (2): 471–492. doi: 10.1007/s13524-012-0151-7

- Brynin, Malcolm, and Francisco Perales. 2015. “Gender Wage Inequality: The De-Gendering of the Occupational Structure.” European Sociological Review 32 (1): 1–13.

- Budlender, Debbie, and Francie Lund. 2011. “South Africa: A Legacy of Family Disruption.” Development and Change 42 (4): 925–946. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7660.2011.01715.x

- Burger, Rulof, and Derek Yu. 2007. “Wage Trends in Post-Apartheid South Africa: Constructing an Earnings Series from Household Survey Data.” DPRU Working Paper 07117, Development Policy Research Unit, University of Cape Town.

- Casale, Daniela, and Dorrit Posel. 2002. “The Continued Feminisation of the Labour Force in South Africa: An Analysis of Recent Data and Trends.” The South African Journal of Economics 70 (1): 156–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1813-6982.2002.tb00042.x

- Casale, Daniela, and Dorrit Posel. 2010. “Unions and the Gender Wage Gap in South Africa.” Journal of African Economies 20 (1): 27–59. doi: 10.1093/jae/ejq029

- Chantreuil, Frédérick, and Alain Trannoy. 2013. “Inequality Decomposition Values: The Trade-Off Between Marginality and Consistency.” Journal of Economic Inequality 11 (1): 83–98. doi: 10.1007/s10888-011-9207-y

- DiNardo, John, Nicole M. Fortin, and Thomas Lemieux. 1996. “Labor Market Institutions and the Distribution of Wages, 1973–1992: A Semiparametric Approach.” Econometrica 64: 1001–1044. doi: 10.2307/2171954

- Gelb, Stephen. 2004. “Inequality in South Africa: Nature, Causes and Responses.” Forum Paper, African Development and Poverty Reduction: The Macro-Micro Linkage. Somerset West, South Africa.

- Gradín, Carlos. 2013a. “Race, Poverty, and Deprivation in South Africa.” Journal of African Economies 22 (2): 187–238. doi: 10.1093/jae/ejs019

- Gradín, Carlos. 2013b. “Conditional Occupational Segregation of Minorities in the U.S.” Journal of Economic Inequality 11 (4): 473–493. doi: 10.1007/s10888-012-9229-0

- Gradín, Carlos. 2019. “Occupational Segregation by Race in South Africa After Apartheid.” Review of Development Economics 23 (2): 553–576. doi: 10.1111/rode.12551

- Gradín, Carlos. 2020. “Segregation of Women into Low-Paying Occupations in the United States.” Applied Economics 52 (17): 1905–1920. doi: 10.1080/00036846.2019.1682113

- Groshen, Erica L. 1991. “The Structure of the Female/Male Wage Differential: Is It Who You Are, What You Do, or Where You Work?” The Journal of Human Resources 26 (3): 457–472. doi: 10.2307/146021

- Grün, Carola. 2004. “Direct and Indirect Gender Discrimination in the South African Labour Market.” International Journal of Manpower 5 (3/4): 321–342. doi: 10.1108/01437720410541425

- Hinks, Timothy. 2002. “Gender Wage Differentials and Discrimination in the New South Africa.” Applied Economics 34 (16): 2043–2052. doi: 10.1080/00036840210124991

- Kerr, Andrew, David Lam, and Martin Wittenberg. 2016. “Post-Apartheid Labour Market Series [dataset], Version 3.1.” Cape Town: DataFirst [producer and distributor].

- Kimani, Esther M. 2015. “Education and Labor Market Outcomes in South Africa: Evidence from the National Income Dynamics Study.” PhD Diss., Cape Town: University of Cape Town.

- Leibbrandt, Murray, Ingrid Woolard, Hayley McEwen, and Charlotte Koep. 2010. “Employment and Inequality Outcomes in South Africa.” Southern Africa Labour and Development Research Unit and School of Economics, University of Cape Town.

- Minnesota Population Center. 2015. “Integrated Public Use Microdata Series, International: Version 6.4 [Machine-readable database].” Minneapolis: University of Minnesota.

- Ntuli, Miracle. 2007. “Exploring Gender Wage Discrimination in South Africa, 1995-2004: A Quantile Regression Approach.” IPC Working Paper Series 56, International Policy Center, Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy, University of Michigan.

- Oosthuizen, Morné. 2006. “The Post-Apartheid Labour Market: 1995–2004.” Working Paper 06/103, Development Policy Research Unit, University of Cape Town.

- Parashar, Sangeeta. 2008. “Marginalized by Race and Place: Occupational Sex Segregation in Post-Apartheid South Africa.” PhD Diss., University of Maryland.

- Posel, Dorrit. 2014. “Gender Inequality.” In Oxford Companion to the Economics of South Africa, edited by Haroon Bhorat, Alan Hirsch, Ravi Kanbur, and Mthuli Ncube, 303–310. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Rospabé, Sandrine. 2001. “An Empirical Evaluation of Gender Discrimination in Employment, Occupation Attainment and Wage in South Africa in the Late 1990s.” Mimeographed. Cape Town: University of Cape Town.

- Rospabé, Sandrine. 2002. “How Did Labour Market Racial Discrimination Evolve After the End of Apartheid?” South African Journal of Economics 70 (1): 185–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1813-6982.2002.tb00043.x

- Shepherd, Debra. 2008. “Post-Apartheid Trends in Gender Discrimination in South Africa: Analysis Through Decomposition Techniques.” Stellenbosch Economic Working Papers: 06/08, Stellenbosch University.

- Shorrocks, Anthony F. 2013. “Decomposition Procedures for Distributional Analysis: A Unified Framework Based on the Shapley Value.” Journal of Economic Inequality 11 (1): 99–126. doi: 10.1007/s10888-011-9214-z

- Treiman, Donald J., Matthew McKeever, and Eva Fodor. 1996. “Racial Differences in Occupational Status and Income in South Africa, 1980 and 1991.” Demography 33 (1): 111–132. doi: 10.2307/2061717

- Winter, Carolyn. 1999. “Women Workers in South Africa: Participation, Pay and Prejudice in the Formal Labour Market.” African Region Country Department, Washington D.C.: World Bank.

- Wittenberg, Martin. 2014. “Analysis of Employment, Real Wage, and Productivity Trends in South Africa Since 1994.” Conditions of Work and Employment Series 45. Geneva: International Labour Office.