?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This study examines the role of occupational classes in the Gender Wealth Gap (GWG). Despite rising interest in gender differences in wealth, the central role of occupations in restricting and enabling its accumulation has been neglected thus far. Drawing on the German Socio-Economic Panel, this study employs quantile regressions and decomposition techniques. It finds explanatory power of occupational classes for the gender wealth gap, which exists despite accounting for other labor-market-relevant parameters, such as income, tenure, and full-time work experience at different points of the wealth distribution. Wealth gaps by gender vary between and within occupational classes. Particularly, women’s underrepresentation among the self-employed and overrepresentation among sociocultural professions explain the GWG in Germany. The study thus adds another dimension of stratification – occupational class – to the discussion on the gendered distribution of wealth.

HIGHLIGHTS

Women’s lower full-time work experience and income drive the overall gender wealth gap.

Occupational classes explain more of the gender wealth gap than family or workplace characteristics.

Gender wealth differences are largest among self-employed and managerial classes.

The gap exists even among female-dominated sociocultural professions.

INTRODUCTION

The gendered nature of economic inequality is a persistent phenomenon in many countries. Despite extensive research on gender differences in income and pay, the Gender Wealth Gap (GWG) only recently gained more scrutiny from social scientists across various disciplines (Deere and Doss Citation2006; Sierminska, Frick, and Grabka Citation2010; Ruel and Hauser Citation2013; Grabka, Marcus, and Sierminska Citation2015; Lersch, Jacob, and Hank Citation2017; Schneebaum et al. Citation2018).

Wealth, however, is a central dimension of inequality as it captures current inequalities in income, property, and inheritance, as well as past inequalities over the life-course and across generations. Wealth can further predict future inequalities as today’s levels of wealth or investments into housing or private pensions can impact future life and generations (Cowell, Karagiannaki, and McNight Citation2012; Piketty Citation2014; Pfeffer and Killewald Citation2017). Therefore, inequalities in wealth add another layer to the gendered nature of economic inequalities in contemporary societies (Ruel and Hauser Citation2013).

Rising interest in the GWG has led to a dynamic interdisciplinary field of research. Studies find that women’s lower levels of wealth are mostly attributable to lower lifetime earnings, discontinuous labor trajectories, and family obligations (Sierminska, Frick, and Grabka Citation2010; Lersch Citation2017). Our study expands existing research by arguing that next to these well-established determinants, women work in occupations that further restrict them from wealth accumulation.

Previous research on the gender pay gap has shown that women cluster in precarious, low prestige, and low-income occupations with high shares of part-time employment, which contributes to a rise in wage inequalities between men and women (Blau and Kahn Citation2017; Minkus Citation2019). Given that the lion’s share of wealth is the result of savings from income (Killewald, Pfeffer, and Schachner Citation2017), we reason that women’s position in the occupational class structure does not only exacerbate gender wage differentials but also restricts women from wealth accumulation. Hence, the aim of our paper is to pursue an integrative approach studying three dimensions of inequality – gender, wealth, and occupational class – together. We assume that the association between these three dimensions varies along the wealth distribution – given the strong concentration of wealth at the top and the crucial role of gendered occupational segregation in wage dispersion. Therefore, we investigate gender differences in wealth and their association with occupational classes among the working population at different points of the wealth distribution in Germany.Footnote1

GENDER DIFFERENCES IN WEALTH

Wealth is usually measured at the household level, therefore most papers investigating the GWG compare female-headed households to male-headed households (Ruel and Hauser Citation2013; Schneebaum et al. Citation2018; see also Deere and Doss [Citation2006]), as individual-level data are only available for Australia and Germany.

Existing studies on the GWG follow two overlapping lines of research. The first is concerned with family demographics. Studies pursuing this strand of research show that married women are wealthier than non-married women (Ruel and Hauser Citation2013) but accumulate less wealth than married men (Lersch Citation2017; Lersch, Jacob, and Hank Citation2017) and face stronger disruptions when marriages dissolve (Warren, Rowlingson, and Whyley Citation2001; Addo and Lichter Citation2013). The timing and number of children further influences the GWG (Yamokoski and Keister Citation2006; Lersch, Jacob, and Hank Citation2017; Ravazzini and Kuhn Citation2018).

The second line of research points out that women’s lower endowment with human capital explains most of the GWG on the individual level (Sierminska, Frick, and Grabka Citation2010; Sierminska, Piazzalunga, and Grabka Citation2019) as well as on the household level (Ruel and Hauser Citation2013; Schneebaum et al. Citation2018). Discontinuous employment trajectories and lower (lifetime) earnings translate into lower wealth levels (Warren, Rowlingson, and Whyley Citation2001; Sierminska, Frick, and Grabka Citation2010; Ruel and Hauser Citation2013; Lersch, Jacob, and Hank Citation2017; Sierminska, Piazzalunga, and Grabka Citation2019) but also education and asset ownership impact the GWG (Ravazzini and Chesters Citation2018; Schneebaum et al. Citation2018).

However, research on the gender wage gap suggests that both mechanisms are intertwined, such that parenthood and care lead to employment breaks (Ehrlich, Möhring, and Drobnič Citation2020) that result in lower lifetime earnings (Boll Citation2011; Ehrlich, Minkus, and Hess Citation2020), as well as lower saving rates and pensions entitlements (Sunden and Surette Citation1998; Warren, Rowlingson, and Whyley Citation2001; Conley and Ryvicker Citation2004).

According to the permanent income hypothesis (Bewley Citation1977), individuals compensate for economic fluctuations by saving and dissaving wealth. Hence, wealth inequality between different groups is the result of differences in individual’s possibility to self-insure against earning shocks (De Nardi and Fella Citation2017).Footnote2 We believe that occupational classes could be one missing link to explain these gender differences in saving wealth because recent work on the gender wage differential suggests that pay differences between men and women are also the result of rising occupational segregation (Blau and Kahn Citation2017; Minkus Citation2019; Minkus and Busch-Heizmann Citation2020). Therefore, by integrating occupations into the analysis of wealth inequality, we propose an approach beyond contemporary research on the GWG.

We argue that occupations aggregate toward something more than single labor market-related components such as skill level, average job tenure, work experience, or income and significantly influence earnings net of job characteristics or human capital (Blau and Kahn Citation2017). Occupations capture past as well as future employment and income trajectories as well as associated risks that are not fully accounted for by measures for current levels of income and employment status (Blau and Kahn Citation2017).Footnote3 Further, occupations differ in power resources that are not directly observable. Latent dimensions such as overall job security, unionization, or strong lobby groups impact gender wealth differences just as much as they influence wage gaps.Footnote4 Occupations where women constitute the majority tend to have lower power resources to secure these latent dimensions, illustrated by, for example, lower levels of unionization (Minkus Citation2019) or lower additional allowances such as capital-forming benefits (Mohan and Ruggiero Citation2003) that in turn enable and restrict women to save and/or make long term-investment decisions into, for example, housing or stocks.

OCCUPATIONS AND WEALTH

There is tentative evidence that occupational positions are important for the gendered accumulation of wealth (Warren Citation2006; Sierminska, Piazzalunga, and Grabka Citation2019). A quantitative study by Tracey Warren (Citation2006) shows for the UK that gender, class, and ethnic differences in pension wealth exist and overlap – making a case for how different dimensions of stratification work together. Qualitative work shows that sons of elite classes inherit predominantly businesses equity whereas daughters are left with real estate of lower value (Bessière Citation2019), resulting in different starting levels for wealth accumulation among men and women heirs (though quantitative studies cannot map such gender difference in wealth, see Szydlik [Citation2004]). There is further evidence by Eva Sierminska, Daniela Piazzalunga, and Markus Grabka (Citation2019) that returns to occupational position explain part of the wealth gap and women’s increasing participation in white collar work has led to a slight attenuation of the GWG over time.

While occupational positions are merely control variables in most studies, we add to the literature by putting occupational class at the forefront of the analysis of gender wealth differences. For example, it is a well-established fact that self-employment is positively associated with wealth levels for both men and women (Sierminska, Frick, and Grabka Citation2010), although self-employment comes with large income risks. However, men are more likely to be self-employed and own a business, and – conditional on self-employment – the gender gap in wealth is especially large with regards to business assets (Edlund and Kopczuk Citation2009). This is because women are less likely to own and run large companies compared to men (Bertrand and Hallock Citation2001; Budig Citation2006; Austen, Jefferson, and Ong Citation2014) and use self-employment to substitute for part-time work and its better reconciliation capacities with family work (Georgellis and Wall Citation2005; Lechmann and Schnabel Citation2012). Therefore, women face lower power resource when self-employed.

Lower levels of and returns to self-employment have been explained by differences in risk-taking, however, empirical evidence is inconsistent at best (Schubert et al. Citation1999). Julie A. Nelson (Citation2016), for example, has shown in a reexamination of existing studies that the risk distributions of men and women largely overlap (Nelson Citation2015).

Next to gender wealth differences in self-employment, wealth gaps might exist in other occupational classes: women have entered higher professions in large numbers (Crompton Citation1987) but mainly occupy those in the sociocultural sector and are less found in technical professions like engineers, that are usually higher paid (Oesch Citation2006: 275). Evidence from Sweden further suggests that women oftentimes cluster in dead-end occupations with lower career prospects (Bihagen and Ohls Citation2007) and henceforth face restrictions when taking out (secure) mortgages (Baker Citation2014). Further research has shown that managerial women report lower wages, are less likely to be paid in stock options, and their bonuses are smaller (Mohan and Ruggiero Citation2003; Kulich et al. Citation2011), which directly affects their capital income and wealth accumulation. In contrast, there might be occupational classes where restrictions to accumulate wealth are less pronounced for both men and women, for example, among the working classes with very low levels of wealth (Waitkus and Groh-Samberg Citation2018). While it seems straightforward that the lack of power resources (for example, a higher probability to become unemployed, lower wages) correlates negatively with wealth levels, it could alternatively be the case that – conditional on income – women with lower power resources save at higher rates while expecting future income losses (Bewley Citation1977; De Nardi and Fella Citation2017), although women’s capacities for saving are much more restricted due to their lower levels of income. We want to know whether occupational classes help us to understand why wealth gaps still exist after controlling for differences in income, labor market experiences, and family obligations. We take the occupational structure at large into account and investigate the GWG across occupational classes among the working population at different points of the wealth distribution using an occupational class scheme.

THE OESCH CLASS SCHEME

In order to assess the importance of specific occupations for the gender wealth gap, the occupational class scheme chosen must meet two criteria: First, it must differentiate the occupational class structure at the top thoroughly, as wealth accumulation is mostly restricted to upper-middle classes in Germany (Waitkus and Groh-Samberg Citation2018). Additionally, wage differentials in leadership positions are particularly high (Calanca et al. Citation2019; Minkus and Busch-Heizmann Citation2020), which in turn lead to discrepancies regarding saving wealth from income between men and women. Second, the occupational class scheme must capture gender differences that have arisen through the increasing feminization of labor markets (Crompton Citation1987, Citation1999) and consequently occupational segregation between men and women.

To the best of our knowledge, the Oesch (Citation2006) class scheme is well-suited to account for the rising feminization of the labor force and therefore captures those gender differences. What is more, its systematic differentiation of the top of the employment structure enables us to capture wealth differences by differentiating the broader higher professional groups into managerial occupations, technical experts, and sociocultural professionals (Oesch Citation2006).

The resulting class scheme () differentiates the self-employed from the employed groups to account for the well-acknowledged and persistently shown employer-employee divide (for a discussion of the role of self-employment in the GWG see paragraph above). Vertically, classes are further differentiated according to the skill levels these jobs require. Horizontally, classes are differentiated according to work logics and the individual role in in the division of labor (Kriesi Citation1989; Oesch Citation2006). Following differences in work logics and skill levels between classes, we argue that incumbents of the different classes also face different capabilities to save. Exact mechanisms are laid out in the following.

Oesch (Citation2006: 61ff) argues that managers are much more loyal toward their organization as their job directly depends on the success of the organization they are employed with, resulting in a personal interest in profit maximation. Hence, we would expect managers to be more open toward private wealth accumulation since part of their remuneration may come as capital.

In contrast, sociocultural professionals (such as [university] teachers, journalists, or medical doctors and nurses) rely more on their skills, knowledge, and specialized training applied in a variety of contexts, which makes this group less reliant on a specific employer. Instead, sociocultural professionals’ orientation is toward their professional group and the autonomy of their discipline (Oesch Citation2006: 61; see also Kriesi [Citation1989]). Therefore, we argue that sociocultural professionals might be less prone to private wealth accumulation and profit maximization and instead rely more on their income-generating skills.Footnote5

Technical experts (such as engineers and computer professionals) could be in an intermediate position between managers and sociocultural professionals regarding levels of wealth.

Given that women occupy different occupational groups compared to men (they are overrepresented among sociocultural professions und underrepresented among technical experts) that come with different power resources, payment, and orientations toward wealth accumulation (Crompton Citation1987; Oesch Citation2006), we suspect between-class inequalities to moderate the GWG.

Wealth differences between occupational classes could be further stratified by gender differences within occupational classes: as mentioned, women managers are paid less often in stock options (Mohan and Ruggiero Citation2003), leading to their overall lower levels of wealth compared to men managers. Though women are overrepresented among sociocultural professions, they might cluster just in these in dead-end occupations with lower career prospects (Bihagen and Ohls Citation2007), which keep women back from long-term investments such as taking out (secure) mortgages (Baker Citation2014). In contrast, male sociocultural professionals might have higher wealth levels than their female counterparts, as they occupy the best-paid positions within this group (Bertrand and Hallock Citation2001).

The role of occupational class in the GWG is therefore twofold: First, women and men are horizontally allocated within different occupational classes that differ in their inclination to accumulate wealth. Second, gender inequalities exist within occupational classes, for example, when women managers are less likely to be paid in stock options than men managers.

While the Oesch scheme captures differences in gender composition across classes (Tables and in the Appendix include an overview) and explains differences in income and earnings, pension system integration and political orientations (Oesch Citation2006, Citation2008; Gingrich and Häusermann Citation2015) its capacity to explain wealth differences is yet to be explored (Lambert and Bihagen Citation2014; see Waitkus and Groh-Samberg [Citation2018] for descriptive evidence). In what follows, we will test to what extent Oesch classes are associated with the GWG. As we suspect the association to vary across the wealth distribution, we will test the association at different wealth quantiles.

ANALYTICAL APPROACH

We test the association between gender, wealth, and occupational class using Germany as our case study. Germany remains a crucial case in wealth research as levels of inequality are higher than in any other Eurozone country (Grabka and Westermeier Citation2014; Pfeffer and Waitkus Citation2021), due to low average levels of wealth resulting from historically low home ownership rates (Kurz Citation2004). Additionally, a comparatively encompassing social insurance system renders wealth accumulation less necessary for old-age security than in other welfare states (Pfeffer Citation2011).

Data

We employ data from the Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP). The SOEP was initiated in 1984 in West Germany and expanded to East Germany in 1990. All household members 17 years and older are interviewed on a yearly basis. The survey covers more than 30,000 individuals in over 15,000 households (Goebel et al. Citation2019), including information on socioeconomic resources and different components of wealth. A detailed wealth module permits an in-depth analysis of individual (and household) wealth (Frick, Grabka, and Marcus 2010).Footnote6 The wealth module includes high-quality data on net wealth and other assets. Individual wealth is provided in five replicates, following extensive and demanding imputation by the SOEP team to account for item non-response and underreporting (Frick, Grabka, and Marcus 2010). To account for the five replicates and their repeated observations, we employ Rubin’s rule (Citation1996) for estimating standard errors using the stata command mi estimate and average coefficients across the imputed samples.

Sample

We use all available wealth data and pool the respective years (2002, 2007, 2012, and 2017) as levels of wealth inequality have been persistently high (Grabka and Halbmeier Citation2019). We restrict our sample to the working population between 20 and 64 years old, living in private households. Since our central independent variable is occupational class, we restrict our sample to those who do not have missing information on the class measure. Our final sample size consists of 20,462 observations for women (N = 12,442) and 20,620 for men (N = 12,220) men.

Variables

Our central dependent variable is individual net wealth, defined as the sum of all financial and real assets minus liabilities. Given that net wealth can be negative or zero, we apply the inverse hyperbolic sine transformation to our wealth measures (Pence Citation2006). This transformation allows for the inclusion of zero and negative values (Gale and Pence Citation2006; Schneebaum et al. Citation2018). Wealth data are top and bottom-coded at the 0.1 and 99.9 percentile and inflation adjusted to constant 2015€.

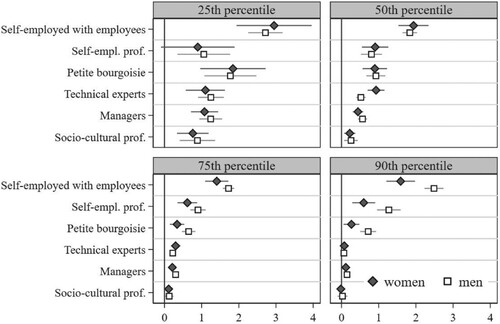

Our central independent measure is occupational class, operationalized as a collapsed version of the Oesch class scheme (Oesch Citation2006). While Oesch’s version includes eight occupational classes (), we further collapse the working classes into one group for our main analysis, due to the low levels of net wealth among them (). The main model includes six occupational classes, that is, self-employed, technical professionals, managers, sociocultural professionals, and workers (Table ). To account for heterogeneity within self-employed groups (Müller and Arum Citation2004), we run an additional robust check with a class scheme that differentiates the self-employed into large employers, self-employed professionals, and the petite bourgeoisie (see ). However, numbers of observations are very low (see ), which is why our main analysis refrains from such a differentiation.

While occupational class is our central concern, we further control for economic indicators that correlate with gender differences in wealth, such as human capital indicators and household characteristics. We control for individual income by including inflation-adjusted (2015€) monthly and ihs-transformed individual income from work, income from pensions (which includes all kinds of occupational and private pensions), and income from transfers (which includes all kinds of social security benefits like child allowances, housing support, or disability allowance). We account for years of full- and part-time work experience and tenure (years), as well as weekly hours worked. We also include unemployment experience and education in years.

Furthermore, we account for workplace characteristics, such as sectoral structure, working in the public sector, and firm size.Footnote7 Moreover, we account for inheritance by including a dummy for having received an inheritance or gift.Footnote8

We further account for partner’s occupational class (measured as self-employed, professionals, skilled and unskilled workers, non-working partner, no information for partner). Additionally, we introduce variables indicating family traits. Marital status is categorized into being married and cohabiting, married and separated, non-married, divorced, and widowed. We further add the number of children living in the respondent’s household, the number of siblings, as well as the highest parental education to account for the social background (Pfeffer and Killewald Citation2017).

We control for migration background to account for migrants’ lower wealth accumulation and we implement a dummy for the region as there is still a considerable economic gap between East and West Germany (Minkus and Busch-Heizmann Citation2020). Age is included in categories (20–34, 35–49, 50–64 years). Since we work with a pooled sample, we add yearly dummies to control for yearly confounders. Lastly, we control for the wealth imputation using a flag variable. See Table for an overview.

Table 1 Descriptive statistics

Methods

We employ pooled unconditional quantile regressions and decompositions at the 25th percentile, the median, the 75th percentile, and the 90th percentile. Following Sergio Firpo, Nicole Fortin, and Thomas Lemieux (Citation2009), unconditional quantile regression assesses the explanatory variable’s – here occupational class and gender – association with the quantile of the unconditional marginal distribution of net wealth. In unconditional quantile models, the Recentred Influence Function (RIF) is applied (Firpo, Fortin, and Lemieux Citation2009: 954; Fortin, Lemieux, and Firpo Citation2011: 74 ff), which is defined as:

(1)

(1)

With τ indicating a quantile of the marginal distribution of wealth and q is the value of wealth at quantile τ. Hence, the coefficient τ estimates how fy reacts to changes in the independent variables. To account for heteroscedasticity, we calculate robust standard errors.

To investigate in how far different compositions as opposed to different point estimates for different coefficients to these characteristics between men and women drive the GWG, we employ Kitagawa-Oaxaca–Blinder decomposition at different points of the unconditional wealth distribution (Kitagawa Citation1955; Blinder Citation1973; Oaxaca Citation1973; Jann Citation2008). Equation 2 displays the decomposition that includes two components:

Where

refers to the average (RIF) wealth difference between men and women. This wealth difference is decomposed into the “explained” [

] and “unexplained” term

. The explained term refers to the part of the gender wealth gap that is relegated to different endowments between men and women (that is, if self-employment is associated with a wealth penalty and women are less often self-employed than men; how does this difference affect the GWG?). The unexplained term refers to differences in coefficients between men and women (that is, if self-employment poses higher wealth penalties for women compared to men, how does that affect the wealth gap?). Since coefficients of the unexplained part contain all sorts of unmeasured attributes and henceforth might reflect spurious effects due to the omitted variable bias (Blau and Kahn Citation2017), we are predominantly interested in the explained part of the decomposition. Men’s coefficients serve as the benchmark for the decomposition. We also run robustness checks to test if our results hold when women are the reference for the decomposition ().

Although a decomposition across the wealth distribution largely resembles the logic of a regular decomposition, there is one peculiarity: for the estimation, the same descriptive differences are used across the wealth distribution. This means if, for instance, on average men are more often self-employed in our sample than women, the decomposition will use this difference to estimate the explained part of the decomposition across all the points of the wealth distribution. Hence, it does not consider that the difference in self-employment might be diverging across the wealth distribution. Thus, differences in the explained part of the decomposition are driven by diverging coefficients form the pooled benchmark model at different parts of the wealth distribution. Additionally, we account for the fact that categorical coefficients depend on the choice of the reference group, by using the categorical option provided by the oaxaca stata command (Jann Citation2008). We normalize coefficients by estimating them in terms of deviation from the grand-mean rather than deviations from the omitted base category and can thereby circumvent the problem of the omitted base category.

RESULTS

Descriptive results

We start with simple descriptive results. Table shows that median wealth is higher for men than for women across the occupational class structure, and these differences are significant in all occupational classes.

Table 2 Wealth gap within classes

However, there are important differences in size: While the wealth gap amounts to 85,000€ among the self-employed, the gap is smaller in other occupational groups and is only around 3,500€ among workers. The second-largest gap is found among managers, where women report less than half of the levels of wealth than men – although more than half of all managers are women. In contrast, among technical professionals the wealth gap is comparably low (13,000€). Hence, those few women who are technical experts report median levels of wealth that are not too distant from men’s median levels of wealth – at least compared to other occupational classes. The picture is very different among sociocultural professionals: while women mark the large majority in this occupational class (74 percent) their median levels are close to 23,000€ lower compared to men within the same occupational group.

While these descriptive results suggest that gender wealth differences exist across all occupational classes, these insights do not reliably tell us whether these differences persist when we control for human capital indicators, family structure, and other confounders. We run unconditional quantile regression to understand if occupational class is associated with the wealth distribution for men and women, net of relevant controls.

Unconditional quantile regression

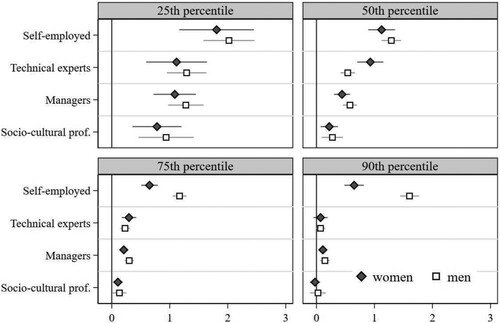

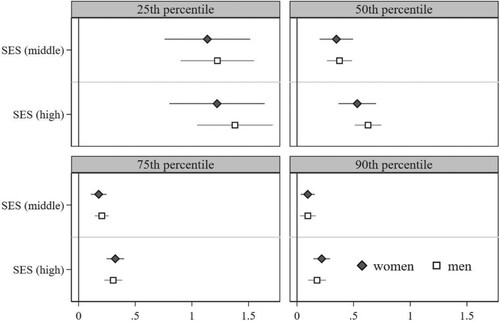

Unconditional quantile regressions are displayed in Figure (full regression results in ) describing the association between occupational class with the unconditional wealth distribution at the 25th percentile, the median, the 75th, and the 90th percentile for men and women.Footnote9

Figure 1 Results from unconditional quantile regressions (only occupational classes) Notes: SOEP.v35 2002, 2007, 2012, 2017 (cf. ). Not weighted.

Figure illustrates a clear positive association between self-employment and wealth for women and men at all points of the wealth distribution (reference is workers).Footnote10 The figure also illustrates that men seem to profit slightly more from being self-employed than women do. Still, gender differences are only statistically different at the 75th and 90th percentile (see respective confidence intervals). In contrast, gender differences are not significantly different at the bottom and middle of the distribution (25th and 50th percentile, as indicated by overlapping confidence intervals).Footnote11

Investigating other occupational classes, we observe a significant positive association between being a technical expert and wealth for women and men at the 25th percentile, the median, and the 75th percentile of the wealth distribution. Only at the median, however, the association for women technical professionals is statistically different from the coefficient for men, indicating that being a technical expert is more positively associated with wealth for women compared to men.

Being a manager is positively associated with wealth across the entire wealth distribution for men and women alike. Coefficients, however, do not significantly differ for men and women, therefore, men and women seem to profit equally from being a manager compared to the reference group (workers) at all points of the wealth distribution.

Lastly, sociocultural professionals yield significant positive associations with the unconditional wealth distribution – compared to workers – in all but the 90th percentile. Overall, men and women seem to profit equally in terms of wealth from being a sociocultural professional compared to being a worker.

Investigating the control variables (we only discuss results at the median, see ), regression results reveal that partner’s class is associated with the wealth distribution for women and men. We also find that women experience wealth losses when they have a partner who is not in employment, for men this association is not significant. These results thus indicate the lasting importance of the male breadwinner model, that is, men working full time and women being the secondary earner or homemaker.

Inheritance is also positively associated with wealth at the median for both men and women. Labor income and full-time work experience, education, and job tenure are positively associated with men’s and women’s wealth accumulation. In contrast, compared to working in the banking and insurance sector, working in health, retail, and hospitality sector or other services is negatively associated with wealth while manufacturing is positively associated with the wealth distribution for men and women. Having children is positively associated with wealth for men and women alike, whereas, compared to being married and cohabiting, being divorced or not married is detrimental for women’s and men’s wealth. A higher number of siblings negatively influences wealth accumulation for men and women. Parents not having any degree is negatively associated with wealth levels, and so is being from East Germany and having a migration background, while being older than 20–34 years and wealth are positively associated.

Decompositions

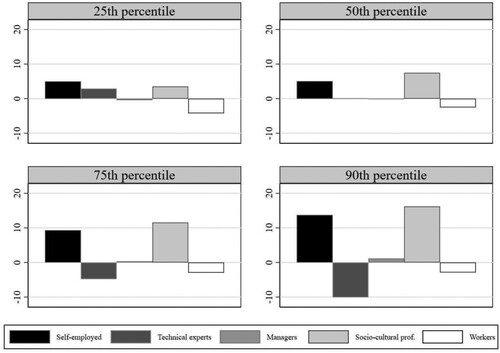

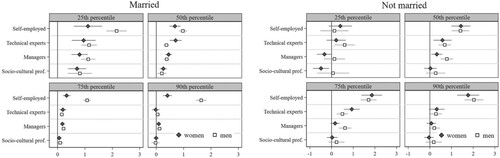

Turning to the decomposition analysis, we see that the explanatory capacity of our occupational class covariates varies across the distribution (Figure and Table ). However, occupational classes add to explaining the GWG at all points of the wealth distribution, though with different sizes and in different directions.

Figure 2 Explained part of the decomposition, only Oesch classes and explained percentages depicted Notes: SOEP V35 2002, 2007, 2012, 2017 (see Table ). Not weighted.

Table 3 Kitagawa-Oaxaca-Blinder-Decompositions

Figure depicts the explained part of the decomposition for occupational classes. Overall, occupational classes explain between 7 and 18 percent of the wealth gap, depending on the percentile of the distribution in the explained part of the decomposition investigated. Different occupational class coefficients for men and women explain between 5 and −45 percent of the overall GWG (unexplained part of the decomposition; see ).

We first turn to the explained part of the decomposition. We find that the explanatory capacity of self-employment is largest at the top of the wealth distribution. In fact, the gendered composition of self-employment explains about 14 percent of the GWG between men and women at the 90th percentile and about 9 percent at the 75th percentile.

In contrast, the composition of technical experts does not significantly influence the GWG at the 25th and 50th percentile, while at the 75th and the 90th percentile this occupational class attenuates the GWG by about 5 and 10 percent, respectively. Men are more often employed as technical experts than women, which depresses the GWG since the association between wealth and being a technical expert turn negative at the upper two points of the wealth distribution investigated (results not shown, obtained using the categorical option of the oaxaca command; Jann Citation2008).Footnote12 Hence, if women were as often technical experts than men, the gap would be larger at the upper-middle and top of the distribution.

The explanatory capacity of managerial occupations is limited: only at the 90th percentile being a manager significantly explains as little as 1.2 percent of the GWG. This is not surprising given that women and men are equally often managers (Table ), and the association with the wealth distribution does not differ significantly (Figure ).

Working in sociocultural professions exacerbates the GWG across the distribution but particularly at the top by as much as 16 percent and even at the 75th percentile about 12 percent. Thus, working in a sociocultural profession does not only include penalties to wealth accumulation (that is, the benchmark coefficient in the decomposition), but the overrepresentation of women significantly widens the gender gap in wealth at the top of the wealth distribution. In contrast, low-wealth occupational classes such as workers seem to – slightly – attenuate the GWG, indicating that the association between wealth and being a worker is negative. This gives marginally underrepresented women a slight advantage in wealth accumulation in this group.

Overall, occupational class does add to explaining the GWG: Particularly, the underrepresentation of women among the self-employed and their overrepresentation among sociocultural professions add to explaining the GWG. In contrast, the gendered composition of technical experts attenuates the GWG, whereas managers do not add much explanatory power for the GWG.

Briefly investigating the unexplained part of the decomposition (Table ) shows that the association between wealth and occupational classes is further stratified: self-employment seems to be particularly beneficiary at the top of the unconditional wealth distribution for men. Hence, if women would profit equally, the gap would be smaller. For sociocultural professionals, we see the negative association for women depresses the GWG. In fact, women’s penalties are not as high as men’s, which is leading toward closing the GWG. This could reflect a general devaluation of sociocultural professions. With regard to technical experts, we find that women have lower penalties compared to men, as the unexplained coefficient is negative and significant at the 25th, the median, and the 90th percentile. The same holds true for being a worker.

Overall, class adds to explaining the overall GWG. Investigating other confounders, however, illustrates that the explanatory capacity of class is smaller than the pooled human capital variables (that is, income from work, transfers, pensions, unemployment, full-time and part-time work experience, weekly working hours, education, inheritance/gifts, and tenure; see Table ). Nonetheless, Table shows that at the 75th percentile, gender composition of occupational classes accounts for about 13 percent of the explained GWG, which is more than workplace characteristics (10 percent; that is, firm size, public sector, and sectoral structure), partner’s class (−5 percent) and family traits (9 percent; that is, marital status, parental education, number of siblings, children). What is more, at the top of the wealth distribution, occupational classes explain even 18 percent of the GWG.

Given that occupational class further correlates with human capital indicators, some of the explanatory power of occupational class is already taken up by other control variables emphasizing the additional role of occupational classes in the GWG, irrespective of human capital indicators.

Robustness checks

To test the robustness of our results, we ran four additional estimations. First, we excluded business equity from the dependent variable to check whether this alters the results, that is, we analyze the importance of portfolio structure on the gender wealth gap (). Except for the 25th percentile, results are similar. However, there is one important finding: The association with self-employment for men drops sharply in the 90th percentile and attenuates a bit for women as well, meaning that self-employed men tend to accumulate more wealth through business equity compared to women.

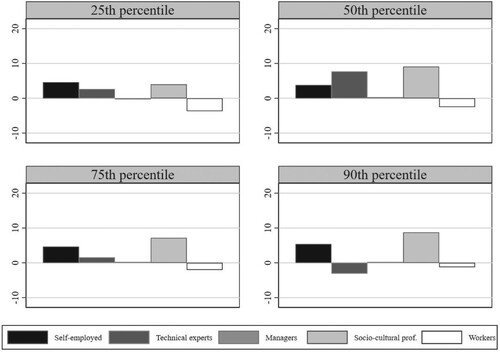

Second, we checked whether socioeconomic status (SES) could serve as an informative proxy for occupation. SES is a measure for occupational status that varies between 16 (for example, cleaners) and 90 (judges; Ganzeboom, De Graaf, and Treiman Citation1992) and is usually divided into three equally sized groups (high, middle, and low SES). further illustrates that SES is not a useful proxy, as results are not significantly different for men and women. Hence, SES measures mask important differences in the association between gender, wealth, and occupations.

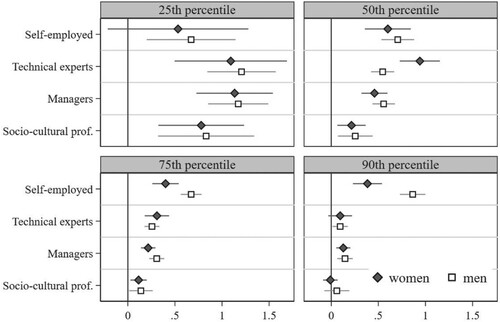

Third, we checked whether our results hold for non-married men and women compared to married individuals (). We find that the positive association of self-employment and wealth at the 75th and 90th percentile is not statistically different for unmarried individuals, while it is for married individuals.

Fourth, to account for the fact that we chose men’s benchmark coefficients in the decomposition, we ran another decomposition in which we used women’s coefficients as the reference (). Not surprisingly, we find that the association between self-employment and sociocultural professionals with wealth at the 75th and 90th percentile is smaller compared to our main model (Figure ).

SUMMARY AND DISCUSSION

The aim of this paper was to investigate the Gender Wealth Gap taking occupational class into account. The results illustrate that integrating a class perspective in the study of gendered wealth inequalities yields interesting insights, and we show that classes explain more of the GWG at different points of the wealth distribution, than, for example, family attributes or workplace characteristics.

We conclude with two main takeaways. First, the GWG varies substantially across occupational groups and is largest among the self-employed and managers. We hypothesize that women run smaller companies and are making less wealth from this, indicating lower power resources in self-employment compared to men. Further, although women are equally often managers, they tend to occupy lower wealth-generating positions. However, even in female-dominated occupational classes such as sociocultural professions the gap is large and profound. In sum, particularly women’s underrepresentation among the self-employed and overrepresentation among the less wealthy sociocultural professions add to explain the GWG in Germany.

Second, despite this additional explanatory capacity of occupational class, the largest impact on the GWG still comes from income and work experience. The decomposition analysis revealed that lower full-time work experience and income are the main drivers of the overall GWG, results that are well in line with previous research (Sierminska, Frick, and Grabka Citation2010; Ruel and Hauser Citation2013). This is not surprising, given that income becomes wealth when it is saved (Killewald, Pfeffer, and Schachner Citation2017), and we assume that part of the association between wealth and occupational class is already taken up by our control variables, as occupational classes differ and are constituted by, for example, income, education, or tenure.

Clearly, our analysis comes with some limitations. We follow the big-class tradition, and we cannot account for intra-class differences. Additional analysis using occupations might show how specific occupations drive the GWG. This could particularly pertain to sociocultural professionals, where a diverse set of occupations are grouped together that vary in power resources toward their employer. However, we leave this to future research.

Further, given the cross-sectional character of this study, we cannot state anything about the association’s direction between occupational class and wealth accumulation. More specifically, selection into self-employment could be the result of previous levels of wealth (Fairlie and Krashinsky Citation2012). Future research should further tackle the gendered nature of self-employment and the devaluation of women’s occupations such as sociocultural professions. Women are less likely to become self-employed in the first place, and when they are, businesses are smaller, and wealth levels are lower (Georgellis and Wall Citation2005; Austen, Jefferson, and Ong Citation2014).

What is more, women’s lower levels of wealth are further the result of the systematic devaluation of women’s occupations, restricting women from accumulating as much wealth as men do. Though women are oftentimes key workers – as currently exemplified in the COVID-19 pandemic – the systematic devaluation and lack of power resources restrict women from keeping up with male levels of income and wealth. When gender differences in labor markets and pay are overcome, we are one significant step closer to ending gender differences in wealth.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Olaf Groh-Samberg, Jean-Yves Gerlitz, the RC28 community (Seoul, 2018), participants of the ECSR-Workshop (2020), the BIGSSS doctoral colloquium, and members of the International Political Economy Workshop at the University of Bremen (2020) for helpful comments on previous versions of this paper. We also thank the editors and three excellent anonymous reviewers for their comments and thorough critique of previous drafts of this paper. All remaining errors are our own.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Nora Waitkus

Nora Waitkus is Postdoctoral Researcher at the International Inequalities Institute at the London School of Economics. Her research deals with wealth and class inequalities across countries. Previously, she has worked at the University of Bremen and was a visiting PhD student at the University of Michigan (USA).

Lara Minkus

Lara Minkus is Postdoctoral Researcher at the University of Bremen, studying gendered inequalities on labor markets. She has worked at the University of Magdeburg and was a visiting PhD student at Cornell University, Ithaca (USA).

Notes

1 Note that we understand occupational classes as families or individuals who share the same economic position and have latent or manifest interests resulting from this position (Kocka Citation1980; Oesch Citation2006). We are not engaging with social classes that further share collective identities through the formation of organizations, class consciousness, and solidarity (Kocka Citation1980).

2 Next to earnings dynamics, differences in saving and therefore wealth inequality are the results result of intergenerational transmission of bequests and human capital, differences in preferences, rates of returns, entrepreneurship, and medical expense risk (De Nardi and Fella Citation2017: 281).

3 We thank an anonymous reviewer for this argument.

4 By job security we mean all kinds of job characteristics that are particularly prevalent among precarious or atypical work arrangements, such as low-wage employment, temporary employment, part-time or marginal employment. In all these categories women constitute the majority in Germany, as the male-breadwinner model and tax breaks incentivize them to take up this kind of work. Hence, we conclude that women have lower job security than men (Palier and Thelen Citation2010; Hipp, Bernhardt, and Allmendinger Citation2015; OECD Citation2017). Whether women trade job security for lower wages has been debunked by recent comparative research (Yu Citation2017).

5 Although the lower reliance on a specific employer could also result in more power resources for women (and thereby lowering their income risk), the opposite seems more likely as illustrated by indicators such as lower average earnings and pension integration (Oesch Citation2006).

6 The SOEP oversamples migrant households, low-income households, high income households, households with children, and East German households (Goebel et al. Citation2019).

7 To take the sectoral structure into account, we introduce industry categories. We differentiate between typically male industries (manufacturing sector), mixed industries (banking and insurance sector), female industries (health, care, retail, and hospitality sector), and other sectors (Minkus and Busch-Heizmann Citation2020).

8 The SOEP does not ask for inheritance in 2017. Therefore, people who entered the survey after 2012 were coded as “not applicable.” If we had earlier information on inheritance and gifts, we imputed that information from earlier years to 2017.

9 It is particularly noteworthy that confidence intervals and standard errors at the 25th percentile are large compared to the other points of the wealth distribution, indicating that coefficients are not estimated as efficiently as in the other percentiles. Therefore, we interpret our findings for the 25th percentile with caution throughout the rest of the paper.

10 The covariate at quantile τth indicates a marginal effect of a small location shift in the distribution of covariates, keeping everything else constant (Borah and Basu Citation2013).

11 Differentiating the self-employed into those who own large companies, self-employed professionals, and the petite bourgeoisie (for example, small shop owners; Appendix ), reveals that wealth gap exists for employers with employees, the self-employed professionals, as well as the petite bourgeoisie. But only at the 90th percentile are these differences statistically significant for men and women across different forms of self-employment.

12 To circumvent problem of the omitted base category, we transformed categorical variables in the decomposition in order to interpret them with reference to their grand mean and not to the base category “workers.” Thus, corresponding rif-coefficients of men’s point estimates from still serve as the benchmark but need to be transformed when calculating results of the decomposition for categorical variables. For example, with regard to self-employed in the 50th quantile, men’s rif-coefficient (1.3024404) needs to be subtracted from the grand mean of the Oesch rif-coefficients ([1.3024404+0.54480372+0.58540863+0.27858174+0]/5=0.5422469). Therefore, the coefficients of self-employed in the 50th quantile serving as benchmark in the decomposition amounts to 0.7601935 (1.3024404-0.5422469). Correspondingly we calculate the decomposition estimate depicted in the explained part in Table at the 50th percentile by carrying out the following estimation: (0.0872939-0.0525364)x(0.7601935) = 0.02642243.

REFERENCES

- Addo, Fenaba R. and Daniel T. Lichter. 2013. “Marriage, Marital History, and Black–White Wealth Differentials among Older Women.” Journal of Marriage and Family 75(2): 342–62.

- Austen, Siobhan, Therese Jefferson, and Rachel Ong. 2014. “The Gender Gap in Financial Security: What We Know and Don't Know About Australian Households.” Feminist Economics 20(3): 25–52.

- Baker, Amy Castro. 2014. “Eroding the Wealth of Women: Gender and the Subprime Foreclosure Crisis.” Social Service Review 88(1): 59–91.

- Bertrand, Marianne and Kevin F. Hallock. 2001. “The Gender Gap in Top Corporate Jobs.” ILR Review 55(1): 3–21.

- Bessière, Céline. 2019. “Reversed Accounting: Legal Professionals, Families and the Gender Wealth Gap in France.” Socio-Economic Review. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwz036.

- Bewley, Truman. 1977. “The Permanent Income Hypothesis: A Theoretical Formulation.” Journal of Economic Theory 16(2): 252–92.

- Bihagen, Erik and Marita Ohls. 2007. “Are Women Over-Represented in Dead-End Jobs? A Swedish Study Using Empirically Derived Measures of Dead-End Jobs.” Social Indicators Research 84(2): 159–77.

- Blau, Francine D. and Lawrence M. Kahn. 2017. “The Gender Wage Gap: Extent, Trends, and Explanations.” Journal of Economic Literature 55(3): 789–865.

- Blinder, Alan S. 1973. “Wage Discrimination: Reduced Form and Structural Estimates.” The Journal of Human Resources 8(4): 436–55.

- Boll, Christina. 2011. “Mind the Gap—German Motherhood Risks in Figures and Game Theory Issues.” International Economics and Economic Policy 8(4): 363–82.

- Borah, Bijan J, and Anirban Basu. 2013. “Highlighting Differences Between Conditional and Unconditional Quantile Regression Approaches Through an Application to Assess Medication Adherence.” Health Economics 22(9): 1052–70.

- Budig, Michelle J. 2006. “Intersections on the Road to Self-Employment: Gender, Family and Occupational Class.” Social Forces 84(4): 2223–39.

- Calanca, Federica, Luiza Sayfullina, Lara Minkus, Claudia Wagner, and Eric Malmi. 2019. “Responsible Team Players Wanted: an Analysis of Soft Skill Requirements in job Advertisements.” EPJ Data Science 8(1): 1–20.

- Conley, Dalton and Miriam Ryvicker. 2004. “The Price of Female Headship: Gender, Inheritance, and Wealth Accumulation in the United States.” Journal of Income Distribution 13(3/4): 41–56.

- Cowell, Frank, Eleni Karagiannaki, and Abigail McNight. 2012. “Mapping and Measuring the Distribution of Household Wealth: A Cross-Country Analysis.” LWS Working Paper Series 12, LIS Cross-National Data Center, Luxembourg.

- Crompton, Rosemary. 1987. “Gender, Status and Professionalism.” Sociology 21(3): 413–28.

- Crompton, Rosemary.. 1999. “The Gendered Restructuring of the Middle Classes: Employment and Caring.” Sociological Review 47(2): 165–83.

- De Nardi, Mariacristina and Giulio Fella. 2017. “Saving and Wealth Inequality.” Review of Economic Dynamics 26: 280–300.

- Deere, Carmen Diana and Cheryl R. Doss. 2006. “The Gender Asset Gap: What Do We Know and Why Does it Matter?” Feminist Economics 12(1-2): 1–50.

- Edlund, Lena and Wojciech Kopczuk. 2009. “Women, Wealth, and Mobility.” American Economic Review 99(1): 146–78.

- Ehrlich, Ulrike, Lara Minkus, and Moritz Hess. 2020. “Einkommensrisiko Pflege? Der Zusammenhang von Familiärer Pflege und Lohn” [Income-risk caring? The association between family care and wages]. Zeitschrift für Gerontologie und Geriatrie 53(1): 22–28.

- Ehrlich, Ulrike, Katja Möhring, and Sonja Drobnič. 2020. “What Comes After Caring? The Impact of Family Care on Women’s Employment.” Journal of Family Issues 41(9): 1387–419.

- Fairlie, Robert W. and Harry A. Krashinsky. 2012. “Liquidity Constraints, Household Wealth, and Entrepreneurship Revisited.” Review of Income and Wealth 58(2): 279–306.

- Firpo, Sergio, Nicole M. Fortin, and Thomas Lemieux. 2009. “Unconditional Quantile Regression.” Econometrica 77(3): 953–73.

- Fortin, Nicole, Thomas Lemieux, and Sergio Firpo. 2011. “Decomposition Methods in Economics.” In Handbook of Labor Economics, Volume 4, Part A, edited by Orley Ashenfelter and David Card, 1–102. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- Gale, William G. and Karen M. Pence. 2006. “Are Successive Generations Getting Wealthier, and If So, Why? Evidence from the 1990s.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 1: 155–234.

- Ganzeboom, Harry B. G., Paul M. De Graaf, and Donald J. Treiman. 1992. “A Standard International Socio-Economic Index of Occupational Status.” Social Science Research 21(1): 1–56.

- Georgellis, Yannis and Howard J. Wall. 2005. “Gender Differences in Self-Employment.” International Review of Applied Economics 19(3): 321–42.

- Gingrich, Jane and Silja Häusermann. 2015. “The Decline of the Working-Class Vote, the Reconfiguration of the Welfare Support Coalition and the Consequences for the Welfare State.” Journal of European Social Policy 25(1): 50–75.

- Goebel, Jan, Markus M. Grabka, Stefan Liebig, Martin Kroh, David Richter, Carsten Schröder, and Jürgen Schupp. 2019. “The German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP).” Jahrbücher für Nationalökonomie und Statistik 239(2): 345–60.

- Grabka, Markus M. and Christoph Halbmeier. 2019. “Vermögensungleichheit in Deutschland Bleibt Trotz Deutlich Steigender Nettovermögen Anhaltend Hoch” [Wealth inequality remains high in Germany despite a significant rise in net wealth levels]. DIW Wochenbericht 86(40): 735–45.

- Grabka, Markus M., Jan Marcus, and Eva Sierminska. 2015. “Wealth Distribution Within Couples.” Review of Economics of the Household 13(3): 459–86.

- Grabka, Markus M. and Christian Westermeier. 2014. “Persistently High Wealth Inequality in Germany.” DIW Economic Bulletin 4(6): 3–15.

- Grabka, Markus M. and Christian Westermeier. 2015. “Editing and Multiple Imputation of Item Non-Response in the Wealth Module of the German Socio-Economic Panel.” SOEP Survey Papers No. 272.

- Hipp, Lena, Janine Bernhardt, and Jutta Allmendinger. 2015. “Institutions and the Prevalence of Nonstandard Employment.” Socio-Economic Review 13(2): 351–77.

- Jann, Ben. 2008. “The Blinder–Oaxaca Decomposition for Linear Regression Models.” Stata Journal 8(4): 453–79.

- Killewald, Alexandra, Fabian T. Pfeffer, and Jared N. Schachner. 2017. “Wealth Inequality and Accumulation.” Annual Review of Sociology 43: 379–404.

- Kitagawa, Evelyn M. 1955. “Components of a Difference Between Two Rates.” Journal of the American Statistical Association 50(272): 1168–94.

- Kocka, Jürgen. 1980. “The Study of Social Mobility and the Formation of the Working Class in the 19th Century.” Le Mouvement Social 111: 97–117.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter. 1989. “New Social Movements and the New Class in the Netherlands.” American Journal of Sociology 94(5): 1078–116.

- Kulich, Clara, Grzegorz Trojanowski, Michelle K. Ryan, S. Alexander Haslam, and Luc D. R. Renneboog. 2011. “Who Gets the Carrot and who Gets the Stick? Evidence of Gender Disparities in Executive Remuneration.” Strategic Management Journal 32(3): 301–21.

- Kurz, Karin. 2004. “Home Ownership and Social Inequality in West Germany.” In Home Ownership and Social Inequality in Comparative Perspective, edited by Karin Kurz and Hans-Peter Blossfeld, 21–60. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Lambert, Paul S. and Erik Bihagen. 2014. “Using Occupation-Based Social Classifications.” Work, Employment and Society 28(3): 481–94.

- Lechmann, Daniel S. J. and Claus Schnabel. 2012. “Why is There a Gender Earnings Gap in Self-Employment? A Decomposition Analysis with German Data.” IZA Journal of European Labor Studies 1(6): 1–25.

- Lersch, Philipp M. 2017. “The Marriage Wealth Premium Revisited.” Demography 54(3): 961–83.

- Lersch, Philipp M., Marita Jacob, and Karsten Hank. 2017. “Parenthood, Gender, and Personal Wealth.” European Sociological Review 33(3): 410–22.

- Minkus, Lara. 2019. “Labor Market Closure and the Stalling of the Gender Pay Gap.” SOEPpapers on Multidisciplinary Panel Data Research No. 1049.

- Minkus, Lara and Anne Busch-Heizmann. 2020. “Gender Wage Inequalities Between Historical Heritage and Structural Adjustments: A German–German Comparison Over Time.” Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society 27(1): 156–86.

- Mohan, Nancy and John Ruggiero. 2003. “Compensation Differences Between Male and Female CEOs for Publicly Traded Firms: a Nonparametric Analysis.” Journal of the Operational Research Society 54(12): 1242–48.

- Müller, Walter and Richard Arum. 2004. “Self-employment Dynamics in Advanced Economies.” In The Reemergence of Self-Employment: A Comparative Study of Self- Employment Dynamics and Social Inequality, edited by Richard Arum and Walter Müller, 1–35. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Nelson, Julie A. 2015. “Are Women Really More Risk-Averse Than men? A Re-Analysis of the Literature Using Expanded Methods.” Journal of Economic Surveys 29(3): 566–85.

- Nelson, Julie A.. 2016. “Not-So-Strong Evidence for Gender Differences in Risk Taking.” Feminist Economics 22(2): 114–42.

- Oaxaca, Ronald. 1973. “Male-Female Wage Differentials in Urban Labor Markets.” International Economic Review 14(3): 693–709.

- OECD. 2017. The Pursuit of Gender Equality-An Uphill Battle. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- Oesch, Daniel. 2006. Redrawing the Class Map. Stratification and Institutions in Britain, Germany, Sweden and Switzerland. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Oesch, Daniel.. 2008. “The Changing Shape of Class Voting. An Individual-Level Analysis of Party Support in Britain, Germany and Switzerland.” European Societies 10(3): 329–55.

- Palier, Bruno and Kathleen Thelen. 2010. “Institutionalizing Dualism: Complementarities and Change in France and Germany.” Politics & Society 38(1): 119–48.

- Pence, Karen M. 2006. “The Role of Wealth Transformations: An Application to Estimating the Effect of Tax Incentives on Saving.” Contributions to Economic Analysis & Policy 5(1): 1–24.

- Pfeffer, Fabian T. 2011. “Status Attainment and Wealth in the United States and Germany.” In Persistence, Privilege and Parenting. The Comparative Study of Intergenerational Mobility, edited by Timothy M. Smeeding, Robert Erikson, and Markus Jäntti, 109–37. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Pfeffer, Fabian T. and Alexandra Killewald. 2017. “Generations of Advantage. Multigenerational Correlations in Family Wealth.” Social Forces 96(4): 1411–42.

- Pfeffer, Fabian T. and Nora Waitkus. 2021. “The Wealth Inequality of Nations.” American Journal of Sociology 86(4): 567–606.

- Piketty, Thomas. 2014. Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Ravazzini, Laura and Jenny Chesters. 2018. “Inequality and Wealth: Comparing the Gender Wealth gap in Switzerland and Australia.” Feminist Economics 24(4): 83–107.

- Ravazzini, Laura and Ursina Kuhn. 2018. “Wealth, Savings and Children Among Swiss, German and Australian Families.” In Social Dynamics in Swiss Society: Empirical Studies Based on the Swiss Household Panel, edited by Robin Tillmann, Marieke Voorpostel, and Peter Farago, 161–74. Springer Open.

- Rubin, Donald B. 1996. “Multiple Imputation After 18+ Years.” Journal of the American Statistical Association 91(434): 473–89.

- Ruel, Erin and Robert M. Hauser. 2013. “Explaining the Gender Wealth Gap.” Demography 50(4): 1155–76.

- Schneebaum, Alyssa, Miriam Rehm, Katharina Mader, and Katarina Hollan. 2018. “The Gender Wealth gap Across European Countries.” Review of Income and Wealth 64(2): 295–331.

- Schubert, Renate, Martin Brown, Matthias Gysler, and Hans Wolfgang Brachinger. 1999. “Financial Decision-Making: are Women Really More Risk-Averse?” American Economic Review 89(2): 381–85.

- Sierminska, Eva M., Joachim R. Frick, and Markus M. Grabka. 2010. “Examining the Gender Wealth gap.” Oxford Economic Papers 62(4): 669–90.

- Sierminska, Eva, Daniela Piazzalunga, and Markus Grabka. 2019. “Transitioning Towards More Equality? Wealth Gender Differences and the Changing Role of Explanatory Factors Over Time.” SOEPpapers on Multidisciplinary Panel Data Research, 1050.

- Sunden, Annika E. and Brian J. Surette. 1998. “Gender Differences in the Allocation of Assets in Retirement Savings Plans.” American Economic Review 88(2): 207–11.

- Szydlik, Marc. 2004. “Inheritance and Inequality: Theoretical Reasoning and Empirical Evidence.” European Sociological Review 20(1): 31–45.

- Waitkus, Nora and Olaf Groh-Samberg. 2018. “Beyond Meritocracy. Wealth Accumulation in the German Upper Classes.” In New Directions in Elite Studies, edited by Olav Korsnes, Johs Hjellbrekke, Johan Heilbron, Felix Bühlmann, and Mike Savage, 198–220. London: Routledge.

- Warren, Tracey. 2006. “Moving Beyond the Gender Wealth gap: On Gender, Class, Ethnicity, and Wealth Inequalities in the United Kingdom.” Feminist Economics 12(1-2): 195–219.

- Warren, Tracey, Karen Rowlingson, and Claire Whyley. 2001. “Female Finances: Gender Wage Gaps and Gender Assets Gaps.” Work, Employment and Society 15(3): 465–88.

- Yamokoski, Alexis and Lisa A Keister. 2006. “The Wealth of Single Women: Marital Status and Parenthood in the Asset Accumulation of Young Baby Boomers in the United States.” Feminist Economics 12(1-2): 167–94.

- Yu, Wei-hsin. 2017. “Tradeoff or Winner Take All? Relationships Between Job Security and Earnings in 32 Countries.” Sociological Perspectives 60(2): 269–92.

Appendix

Figure A.1: Unconditional quantile regression with different self-employed groups Notes: SOEP.v35 2002, 2007, 2012, 2017. Reference is workers. Not weighted.

Figure A.2: Unconditional quantile regression excluding business equity from net wealth measure Notes: SOEP.v35 2002, 2007, 2012, 2017. Reference is workers. Not weighted.

Figure A.3: Unconditional quantile regression with SES instead of Oesch classes Notes: SOEP.v35 2002, 2007, 2012, 2017. Reference is low SES. Not weighted.

Figure A.4: Unconditional quantile regression, married vs. non-married individuals Notes: SOEP.v35 2002, 2007, 2012, 2017. Reference is workers. Not weighted.

Figure A.5: Explained part of the decomposition, only Oesch classes and explained percentages depicted (women as benchmark coefficients) Notes: SOEP.v35 2002, 2007, 2012, 2017. Categorical option employed (grand-mean over occupational class categories). Not weighted.

Table A.1: Oesch 8-Class Scheme with example occupations

Table A.2: Wealth Gap within detailed Oesch classes

Table A.3. Results from unconditional quantile regressions