?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Do parental caregivers bear the entire cost of caregiving? Standard cooperative models of the household suggest the welfare burden of care would be distributed across household members (for example, husband and wife). This study develops a simple collective model of intrahousehold bargaining to analyze the time and resource allocation decisions associated with providing unpaid care to an elderly parent. The study argues that if bargaining power is endogenously determined or labor markets are rigid, the welfare cost of caregiving can fall disproportionately on the woman partner, resulting in a “triple burden” of market work, home production, and caregiving, in addition to higher levels of unmet care needs. The study provides a numerical example using cross-country European data to demonstrate how a decrease in an adult daughter's bargaining power relative to her partner can increase her share of the welfare burden and the unmet care needs of her parent.

HIGHLIGHTS

Intrahousehold bargaining determines the welfare costs of unpaid caregiving.

Labor market rigidities have nuanced effects on the division of the welfare burden.

Flexible hours/leave policies could provide relief to both caregivers and recipients.

Lower wage gaps and shifting social norms may promote a more equitable division of care.

INTRODUCTION

A growing concern in many countries is an aging population and an increase in the elderly in need of long-term care (Shrestha Citation2000; Agree and Glaser Citation2009; de Meijer et al. Citation2013; Kudo, Mutisya, and Nagao Citation2015). However, the economic and welfare implications of elderly care provision remain relatively understudied. One of the primary factors that complicates welfare analysis is that a majority of elderly care is provided informally by family members, with adult children (disproportionately daughters) often comprising the largest share of care providers (Norton Citation2000; Agree and Glaser Citation2009; Bettio and Verashchagina Citation2010). The pervasiveness of unpaid care due to culture or family ties has even limited the development of long-term care insurance in economically advanced regions like Europe (Costa-Font Citation2010). However, while children may provide an informal safety net, parental caregiving is a time-intensive task and must be met by adjustments along leisure or work margins on the part of the care provider. Hence, to understand the full macroeconomic and gender equity implications of growing elderly care needs and the appropriate policy response, it is imperative to understand how households cope with these caregiving needs (Doepke and Tertilt Citation2016).

We develop a simple collective bargaining model to explore how unpaid parental caregiving can affect the allocation of time and resources across partners under different household power structures. As parental caregiving falls disproportionately on daughters, we consider a benchmark collective model in which a woman's parent may need time-intensive care. While the level of care needed is exogenous to the household, the provision of care is determined endogenously as a bargained outcome between the couple. This allows for some care needs to remain unmet, which is consistent with empirical findings in a variety of contexts (Bień Citation2013; Herr et al. Citation2013). We show in the model how power dynamics and labor markets impact gender equity and the unmet care needs of care recipients. We then use our theory with cross-country data from Europe to illustrate concepts and examine welfare with some numerical exercises.

Importantly, we model bargaining power as endogenous and dependent on the decisions of the household. Specifically, we assume bargaining position is tied to relative earnings.Footnote1 A decline in labor earnings in response to unpaid caregiving can potentially weaken the caregiver's bargaining position and affect the distribution of resources within the couple. For example, if a daughter cuts back on her paid work hours to take care of her ailing mother, there is a reduction in her wage earnings and consequently her bargaining position within her household. The shift of power toward her male partner could subsequently shift the household's spending toward goods preferred by the man. Thus, we argue that care provision may have additional implications for gender inequality if we consider the effect on power dynamics within the household.

We compare theoretical and numerical results under two alternate modeling assumptions: (1) fully flexible labor markets and (2) fixed labor supply due to labor market rigidities. In the presence of labor market rigidities, any adjustments on the labor supply margin can be very costly. Under such circumstances, caregiving needs must be met by adjustments solely along the leisure or home production margins. Returning to our previous example, if the daughter is unable to reduce her work hours to care for her mother, she must either give up additional leisure time, reduce her home production (cooking, home repairs, and so on), or provide less hours of care.

We calibrate our theoretical model using cross-country data from the Survey of Health, Ageing, and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). Several points about our numerical exercises warrant clarification at the outset. First, our reported welfare measure is based on consumption-equivalent variation. It is akin to asking by what percentage market consumption must be decreased to make an individual indifferent to their household providing unpaid care. Second, given the simplicity of our model, our numerical results should not be viewed as precise quantitative empirical estimates. Instead, they help illustrate key concepts of the model and provide qualitative insights with both theoretical and policy relevance.

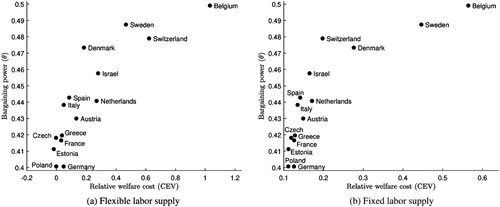

In our numerical exercise with flexible labor supply, we find that for a dual-earning couple in our benchmark country (France), 20 hours a week of care-needs from the woman's parent results in a 41 percent welfare decline for the woman and only 1 percent for the man. In other words, the welfare burden of unpaid caregiving to the man is about 3 percent that of their partner – a very skewed burden. The higher welfare cost to the woman stems from three sources: (1) relatively fewer hours of leisure due to her provision of unpaid care; (2) declines in her labor supply reducing her bargaining power; and (3) the utility cost of leaving her parent with some level of unmet care needs. Comparing countries with higher levels of calibrated bargaining power for women, the welfare burden of unpaid caregiving can be more evenly split across partners. In Sweden, for example, the welfare cost to the man is close to 50 percent of the woman. Moreover, countries with higher bargaining power for women have lower levels of unmet care needs, suggesting power dynamics could have important implications for care recipients as well.

Removing labor market flexibility also results in significant welfare differentials within a household. For instance, when both men and women are unable to adjust work hours, the relative welfare cost to the man in France is 13 percent of that of the woman in our numerical exercise. However, for a more equal country like Sweden, the relative welfare cost to the man is 45 percent. Moreover, only in the most equal countries in our sample do the partners split caregiving responsibilities. In most countries, the woman continues to provide the entire amount of unpaid care, even when adjustments on the formal labor supply margin are eliminated. Introducing labor market rigidities also yields a higher level of unmet care needs. For example, unmet care needs increase almost 50 percent compared to the benchmark case with flexible labor markets in France.

Overall, our theoretical and numerical results show that ignoring bargaining power differentials can misrepresent the welfare effect of unpaid caregiving by not considering the uneven distributional consequences. Specifically, our results suggest that with higher bargaining power for women, the welfare burden of caregiving can be more evenly distributed across household partners and unmet care needs of the elderly parent can be minimized.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Mainstream economic models of elderly care have focused almost exclusively on inter-generational bargaining between parents and children or bargaining among siblings (Pezzin and Schone Citation1999; Engers and Stern Citation2002; Byrne et al. Citation2009; Barczyk and Kredler Citation2018). However, little attention has been paid to the influence of care demands on the power dynamics between partners within a household (for example, husband and wife) despite evidence that caregiving falls disproportionately on women (Barusch and Spaid Citation1989; Agree and Glaser Citation2009; Bettio and Verashchagina Citation2010; Bianchi et al. Citation2012) and that some caregivers respond to increased parental care needs by reducing work hours, taking more flexible jobs, or by quitting paid work entirely (Lilly, Laporte, and Coyte Citation2007; Kotsadam Citation2011; Bauer and Sousa-Poza Citation2015). Moreover, caregiving may have spillover effects on the caregiver's spouse or partner. For example, a spouse may work longer hours or reduce their spending to cope with fewer hours of paid work by the caregiver. So, it is unclear to what extent partners reallocate their time and resources and share the welfare burden of parental care needs when they arise.

In the standard “unitary model” pioneered by Gary S. Becker (Citation1981), a household behaves as if it were a single unit. Feminist economists have long criticized the unitary approach for ignoring power relations within households (Folbre Citation1986, Citation1997; Katz 1997; Kabeer Citation1998; Agarwal Citation1994, Citation1997). Moreover, the pooling of resources across the household implied by the unitary model has been consistently rejected empirically (Fortin and Lacroix Citation1997; Lundberg, Pollak, and Wales Citation1997).Footnote2 In this study, we build a simple collective bargaining model of intrahousehold time and resource allocation in the spirit of Pierre-André Chiappori (Citation1992). This approach views partners as individuals with conflicting preferences but who operate as a cooperative decision-making unit. While the collective bargaining approach has clear limitations in terms of analyzing dynamic social norms and gender roles (Agarwal Citation1997; Katz Citation1997), it is a useful starting point given its generality in characterizing efficient allocations and easy connection to the data.

While household bargaining models have commonly been used to analyze time use in the presence of childcare needs (Doepke and Tertilt Citation2016), less attention has been given to time-intensive parental care. In practice, the decision to provide parental care can be both intrinsically and extrinsically motivated (see England, Folbre, and Leana [Citation2012] for an excellent review). For example, children may have altruistic concern for their parent's well-being (intrinsic) or may expect reciprocal payments/bequests (extrinsic). Gender differences also seem to exist, with women generally showing stronger motivation for care provision. The reason for these gender differences has been hypothesized to include both biological and the social construction of norms and values (England, Folbre, and Leana Citation2012; Braunstein Citation2015). This may partially explain why parental caregiving disproportionately falls on daughters as opposed to sons (Bond Citation1999; Agree and Glaser Citation2009; Bettio and Verashchagina Citation2010; Bianchi et al. Citation2012; Grigoryeva Citation2014; Haberkern, Schmid, and Szydlik Citation2015).

Gender differences in altruism could also yield larger effective bargaining gaps for women across household partners. For example, social norms could condition women to be more altruistic toward their partners than men (Braunstein Citation2015). This is roughly consistent with feminist arguments that care providers wield comparatively low bargaining power (Folbre Citation2017). More broadly, bargaining power is likely influenced by cultural norms, prevailing earnings potential of women, local institutions, and a variety of other external factors. It is plausible that bargaining power could also endogenously evolve depending on the internal decisions of the household. In particular, theoretical and empirical research suggests that one's relative earnings within the household may play an important role (Mencher Citation1988; Blumberg and Coleman Citation1989; Desai and Jain Citation1994; Lundberg, Pollak, and Wales Citation1997; Riley Citation1997; Attanasio and Lechene Citation2002; Bonke and Browning Citation2009). Extending this line of reasoning, we argue that the provision of unpaid care has the potential to further lower bargaining power of women by reducing caregiver earnings in paid employment.

We illustrate this mechanism in some numerical examples by focusing on a subset of European countries that differ in gender power dynamics and eldercare systems. For example, there are generally higher levels of gender parity in Nordic states that may reflect a more equal bargaining position across genders. There is also some evidence that the decision-making power of women in Nordic states is higher than Southern European countries (Mader and Schneebaum Citation2013). At the same time, there is a strong North–South gradient in the likelihood of European women providing care to a parent in ill health (Crespo and Mira Citation2014). Nordic states also tend to have more developed and utilized formal eldercare systems. These systems use a universalist approach with public care available based on need and funded through general taxes (Kotsadam Citation2011). This contrasts with the more family-based eldercare system of Southern, and to some extent Central, Europe. These systems feature higher reliance on unpaid care with public provisions of formal care generally tied to social and economic need. Perhaps not coincidentally, there is also some evidence that there are more unmet care needs among older individuals in southern countries like Greece and Italy than in Sweden or the United Kingdom (Bień Citation2013). Our theory and numerical exercises will further examine how unmet care needs may interact with gender power dynamics within the household.

MODEL

Consider a household consisting of two working adults. For expositional convenience, we refer to household partners as a woman and a man. Each member has their own utility function designating preferences over own consumption of market goods , domestically produced goods

, and leisure

. Utility is separable and given by

where

and

. Each member is endowed with a unit of time that is split between work in the formal labor market

, hours devoted to domestic home production

, and leisure

:

(1)

(1)

The household budget constraint is given by:

(2)

(2)

where the man's wage rate in terms of the market good is set to one and

denotes the wage rate of the woman relative to the man.Footnote3 Partners combine home production hours to produce domestic goods using a constant elasticity of substitution technology:

(3)

(3)

with the man's home production share

and substitutability parameter

. Note that we assume there are no caring responsibilities in the household, including toward children or each other.

Bargaining power

Following the collective bargaining approach of Pierre-André Chiappori (Citation1992), Pareto-efficient allocations of time and resources are derived by maximizing the weighted sum of partner utilities. Specifically, the partners maximize the household welfare function:

subject to constraints (1)–(3). Here,

measures the relative bargaining power of the woman in the household. Note that with equal bargaining weights (a parameter value

), the collective bargaining allocation reduces to that of the standard unitary model.

We model as dependent on the endogenous distribution of income within the household. Specifically, we consider bargaining power defined by

, where

is the woman to man earnings ratios. We assume

so that bargaining power is increasing in relative earnings. For a given value of

, the household maximizes their previously defined welfare function. However, this may in turn cause

to change, resulting in further desired adjustments. Following the idea of Kaushik Basu (Citation1999, Citation2006), we consider the stationary point of this process as the equilibrium of interest. Denoting the solution to the household maximization problem given

as

, the equilibrium of this adjustment process can be defined as follows:

Definition.

A household equilibrium with endogenous bargaining power is a vector of outcomes and a power index

, such that

, and

, where

is the earnings ratio arising from outcome vector

.

The optimal household consumption allocations follow a “sharing rule” as is typical in this type of collective bargaining model and stated in the following proposition:

Proposition 1.

Each partner consumes a fraction of household income and domestic production equal to their bargaining weight:

(4)

(4)

(5)

(5)

Proof.

See Supplemental Online Appendix.

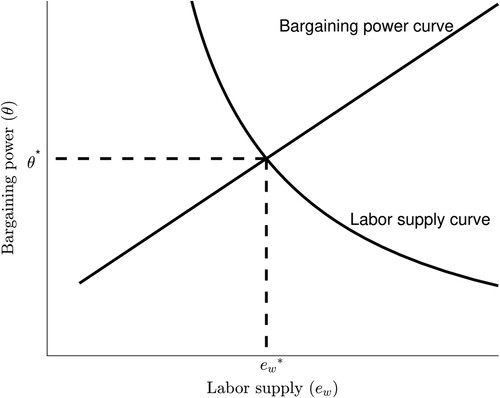

As an illustrative example of the woman's labor supply decision, plots a hypothetical endogenous “bargaining power curve” – holding the man's labor supply constant. The bargaining power curve is upward sloping in the woman's labor supply as more market work increases her relative earnings. Moreover, given bargaining power

, the relevant first-order condition for the woman's labor supply is given by

(6)

(6)

The household equates the marginal benefit of the woman's labor to the weighted marginal cost. also provides a graphical representation of Equation (6), holding the woman's home production hours and the man's labor supply constant. We will refer to this curve as the “labor supply curve.” The curve is downward sloping, reflecting the fact that lower bargaining power increases the woman's labor supply.Footnote4 The equilibrium labor supply and bargaining weight is given by the intersection of the two curves.

As is clear from the figure, as bargaining power for the woman rises, her formal labor supply decreases.Footnote5 The inverse is true for the man – increases in the woman's bargaining weight increases his labor supply. These results are more generally stated in the following proposition:

Proposition 2.

Comparative statics for labor supply response to exogenous changes in bargaining power are given by

Proof.

See Supplemental Online Appendix.

While bargaining power has clear implications for relative labor supplied across partners, this is not the case for hours devoted to domestic production. Combining household optimality conditions yields the following rule for relative allocation of home production hours across partners:

(7)

(7)

This implies the man's home production hours will be lower than the woman's whenever

. Intuitively, when the woman's market returns

are small relative to her home production share

, she will spend more time at home relative to her partner. Note also that relative home production does not depend on bargaining power weight

, but only on the relative productivity of home versus market work.

Finally, we can summarize the relative time burden of home and market work across partners through the following leisure condition:

(8)

(8)

This shows that the man will enjoy more leisure than the woman whenever

. Conversely, if the woman's market return

is low relative to her bargaining weight

, she will enjoy more leisure than her partner.

Parental caregiving

Next, we consider the household equilibrium response to the realization of parental care needs. Clearly there are plausible arguments for treating the provision of unpaid care as a complex, endogenous decision involving cultural norms, bargaining between caregiver and care recipient, and/or bargaining between potential caregiving households (for example, siblings). However, as our focus is on time allocation decisions within households of actual caregivers, we abstract from such consideration and simply treat total care “needs” as exogenous to the household . Unpaid care may be provided by the man

or woman

partner.

While the level of care needed is exogenous to the household, the provision of care is determined endogenously as a bargained outcome between the couple. This allows for some care needs to remain unmet. We define unmet parental care needs as the shortfall in care time supplied below the care time “needed.” This definition most closely aligns with unmet “social care” needs as opposed to professional medical care. Social care generally relates to time-intensive assistance with day-to-day living (for example, dressing, moving around, transportation, taking medication, finances, etc.). Let unmet parental care needs be denoted by .

There are several additional assumptions implicit in our treatment of parental care needs that warrant discussion. First, we specify no characteristics of the parent other than their level of care needs. For example, we ignore the parent's gender, financial resources, and age. Second, we exclude any financial/resource transfers between the care recipient and the household. For example, we ignore market expenditures on care (such as food, medicine, etc.) that could be required of the household and instead focus only on time provided by the caregiver(s). We likewise exclude transfers from the parent to the household, which could clearly alter the welfare burden of providing time-intensive care. Third, we do not explicitly model any transfers from the state. This includes transfers to the parent such as public provision of long-term care, financial resources, or medical care. Alternatively, our time need requirement could be viewed as the remaining need after any transfers of time/resources from the state to the care recipient. We also assume there are no renumerations from the state for care provided by the household. However, later we will discuss the implications of implementing such a renumeration policy.

Consistent with an intrinsic motivational difference across genders and the provision of parental care disproportionately falling on daughters, we assume in our benchmark model it is the woman's parent in need of care and a utility penalty on the woman partner for any unmet care needs of her parent. Specifically, we introduce the following modified household welfare function:

where

and

. The function

provides the woman's disutility from her parent's unmet care needs, which is weighted by her relative bargaining power. With unpaid care, the modified time constraint for each partner and feasibility requirements on caregiving are given by

Note that we assume hours spent in unpaid care are perfect substitutes across partners. In this case, it is optimal for the partner with lower market return to provide all unpaid care:

Proposition 3.

If and

, the woman partner will provide all the unpaid care in the household:

and

. If

and

, the man partner will provide all the unpaid care in the household:

and

.

Proof.

See Supplemental Online Appendix.

If the woman earns less for market work than her partner, it is optimal for her to specialize in parental care. Moreover, this specialization comes at the cost of both forgone market work and home production:

Proposition 4.

If , interior comparative statics for labor supply and home production response to (exogenous) changes in unpaid caregiving are given by

Proof.

See Supplemental Online Appendix.

In contrast to the woman, the man increases market work in response to increasing unpaid care by the woman. However, the man lowers his home production in the same fashion as the woman. This is due to the assumption that home inputs are less than perfect substitutes across partners. Therefore, lower home production of the woman decreases the marginal return to home production of the man. Thus, the man substitutes some hours out of home production and into market labor. Moreover, condition (7) continues to hold in the presence of increasing unpaid care. So not only does home production of the man and woman move in the same direction, it remains in the same proportions.

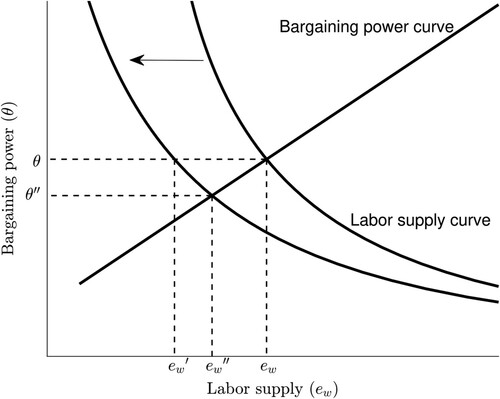

Continuing our illustrative example, plots the woman's labor supply curve with and without unpaid caregiving. Introducing unpaid care shifts the labor supply curve to the left. Consider starting in the equilibrium of the non-caregiving household . In the case of fixed bargaining power, the caregiving requirement results in new equilibrium

. In contrast, the new endogenous bargaining power equilibrium occurs at point

, where the new labor supply curve intersects the power curve. Given the upward slope of the power curve, it is clear that

and

. The woman's labor supply response to unpaid caregiving is weaker with endogenous bargaining power. The magnitude of this difference will depend on the shape and slope of the power curve.

A weak labor supply response is generally consistent with empirical evidence from North America and Europe that suggests there is a negative but often relatively small effect of caregiving on hours worked (Bauer and Sousa-Poza Citation2015). Several mechanisms have been proposed as potential explanations for the small labor response. These include a countervailing wealth effect due to either increased expenses associated with providing unpaid care (for example, food, medicine, etc.) or wage declines due to less work flexibility (Twigg and Atkin Citation1994; Heitmueller and Inglis Citation2007). A “respite effect” has also been proposed where unpaid caregivers prefer work in order to get away from their caregiving responsibilities (Twigg and Atkin Citation1994). Here we are considering a complementary mechanism that operates through the distribution of bargaining power in the household.

Lastly, we can examine the relationship between care provision, unmet care needs, and bargaining power through the interior first-order condition for women's unpaid care:

Recall women's labor supply

is decreasing in bargaining power

(Proposition 2) while the relationship between home production

and

is ambiguous. Consider the case in which the woman weakly lowers her home production (or does not increase it too much) with increasing bargaining power. Then an increase in her bargaining power will also increase the provision of care

given that

is increasing in

and

and

is decreasing in

. In other words, an increase in the woman's bargaining power increases the provision of unpaid care and consequently lowers the equilibrium level of unmet care needs.

Fixed labor supply

Our model has so far assumed fully divisible labor and frictionless labor markets. This allows partners to freely allocate hours between market work, home production, and leisure. If women could only operate on the extensive margin, they may be unable to optimally lower their labor supply in the presence of parental care needs. Likewise, the desired increase in men's labor hours may be infeasible if additional overtime or shifts are unavailable. Moreover, if there are re-employment costs and unpaid caregiving is unlikely to persist for an extended period of time, women may be unwilling to lower labor supply to the same extent as the frictionless model predicts. This may be why becoming a caregiver reduces labor force participation but leaving the caregiver role has no effect on the probability of re-entry into the labor market (Spiess and Schneider Citation2003; Wakabayashi and Donato Citation2005; Van Houtven, Coe, and Skira Citation2013). In this section, we examine the theoretical implications of assuming fixed labor supply in our model.

An important implication of fixed labor supply is that unpaid caregiving no longer always falls entirely to the woman. Given the optimal allocation of home production with fixed labor supply, the relevant first-order condition for unpaid care allocation is given by:

(9)

(9)

Partners divide caregiving time to equalize their marginal cost of lost leisure, weighted by relative bargaining power. With large enough care need

, it is possible that this interior solution is reached, and partners share caregiving responsibilities. This contrasts the model with flexible labor supply, where the woman always provides all the unpaid care (under the conditions of Proposition 3).

At an interior solution where both partners provide some care, home production allocation is determined by the modified condition

(10)

(10)

Comparing to the analogous condition with endogenous labor (7), the optimal distribution of home production is still independent of bargaining weights. However, this allocation no longer depends on relative market wage rate

, as the labor supply margin is eliminated. Instead, the distribution is entirely determined by home production technology parameters.

If parental care needs are small enough, caregiving will continue to fall on a single partner and Equation (9) need no longer hold. In this case, the home production allocation condition becomes

(11)

(11)

Relative home production now depends on bargaining power with the man's hours increasing in

. Intuitively, as home hours are imperfect substitutes, it is optimal to use bargaining power to adjust time along other more substitutable dimensions (that is, work or caregiving). However, with fixed labor supply and the man's care provision already at zero, the only margin left to utilize one's bargaining weight is home production.

NUMERICAL EXAMPLE

In order to illustrate the mechanisms of our theoretical model, we provide a simple, numerical exercise where we calibrate parameters and simulate the influence of parental care needs on consumption and time allocations within a household. Specifically, we compare a baseline of no care needs to an equilibrium with 20 h of care needs per week

.Footnote6 We compare results under our two alternate modeling assumptions: (1) fully flexible labor markets; (2) fixed labor supply due to labor market rigidities. The baseline with no care needs will be identical across the two modeling assumptions; however, predictions will differ once parental care needs are introduced. We begin with a more detailed analysis of a dual-earning household from a single country (France) before conducting a more general European cross-country comparison.

France

Calibration

In order to numerically calibrate our model, we use data primarily from the Survey of Health, Ageing, and Retirement in Europe (SHARE), a longitudinal study of individuals age 50 or older and their partners covering twenty-seven European countries and Israel. SHARE data contains information on socioeconomic-status and social and family networks, including labor market outcomes and time spent in unpaid caregiving. There are currently six waves of SHARE available, collected biennially between 2004 and 2017. We use SHARE data on gender, age, country of residence, weekly hours worked, earnings, and caregiving.

As our framework incorporates only limited heterogeneity, we restrict the SHARE sample to as homogeneous a population as feasible for our baseline exercise. After pooling across all survey waves, we retain observations for individuals ages 40–59 who live with a partner. This age range captures a substantial share of parental caregivers while limiting cases of care provision to one's partner. Limiting the sample to those under 60 also lessens concerns over simultaneous retirement and caregiving decisions. We define an unpaid caregiver as anyone who reported giving personal care or practical household help “about daily” to someone in the previous twelve months.Footnote7 We calibrate parameters using wage and hours worked SHARE data from couples in which both partners are non-caregivers working at least 20 hours a week and neither partner requires care themselves. In other words, we calibrate the model to a household with no caregiving and in which both partners are substantially attached to the labor market. In extensions presented in the Online Appendix, we also examine single women and households with a single market earner.

summarizes the baseline calibration for France. We first set relative earnings potential to equal the aggregate wage ratio of women to men in France from our SHARE sample.Footnote8 We then define standard preferences over leisure given by

where

is a constant Frisch elasticity of labor supply (the elasticity of labor supply with respect to wage, holding the marginal utility of consumption fixed). Empirical studies of the Frisch elasticity vary considerably, with estimates ranging from 0.5 to nearly 2 (Hall Citation2009; Chetty Citation2012). We choose a value of

. Given this form, Equation (8) can be written:

(12)

(12)

Plugging this equation for

into condition (6) yields the following expression for the utility weight on leisure:

(13)

(13)

For home production technology, we assume

, implying partners are equally productive in the production of home goods. Condition (7) may then be written:

(14)

(14)

Finally, combining household first-order conditions for labor supply and home production yields the following equation for utility weight on home consumption:

(15)

(15)

Equations (12)–(15) express four parameters

as functions of four equilibrium moments

. We obtain our calibrated parameter values by estimating these moments from the data and plugging them into the equations. We estimate an average labor supply for men (women) of 42.5 (37.1) hours per week for France from our SHARE sample. As SHARE lacks detailed data on time use outside of the formal labor market, we estimate home production hours with data on hours spent on “unpaid domestic work” from the Multinational Time Use Study (MTUS), a harmonized collection of time diary data. We use data collected in 2009–10 for France and limit the sample to those ages 40–59 in which the individual and their partner work full-time to best approximate our sample used from SHARE. We estimate average home production for men (women) of 11.9 (20.5) hours a week from the MTUS for France.

Table 1 Calibration for France

We additionally need to parameterize the bargaining power function . When introducing parental care, the functional form of

plays a crucial role in the model's predictions when bargaining power is endogenous. As is clear from , any decrease in women's labor supply due to parental care can be rationalized in the model by selecting the appropriate change in bargaining power. Moreover, unlike preference parameters, there is no standard approach or directly applicable research to help credibly pin down the bargaining power function. As such, we choose a simple linear functional form:

(16)

(16)

This form implies

, or that equal earnings yield equal bargaining power. Denoting the baseline equilibrium earnings ratio

, it must that

. As the baseline

is pinned down by Equation (12), we estimate

from our SHARE sample and obtain

.

This leaves only the disutility of unmet care needs to be calibrated. We assume preferences over unmet care needs are given by

where

is the disutility weight on any parental care needs that are not provided by the household. Empirical estimates of unmet care needs can vary significantly depending on definition and data source. The estimated share of elderly with unmet care in France has ranged from 23 to 51 percent of those with a need for care (Gannon and Davin Citation2010; Herr et al. Citation2013). Shortfall in hours of care below the optimal is even more difficult to empirically pin down. For simplicity, we calibrate a care gap of 25 percent, or 5 hours, for our benchmark case in France.Footnote9 This results in

, which is held fixed across modeling assumptions (that is, flexible or fixed labor supply). This seems a plausible starting point and, more importantly, allows for comparison of predicted unmet care needs across differing countries and model assumptions.

Welfare

In addition to examining differences in consumption and time allocation patterns across partners, we are also interested in the distribution of welfare costs. We use a consumption-equivalent variation (CEV) measure to quantify the difference in welfare effects of unpaid caregiving across partners. Our welfare measure is akin to asking by what percentage market consumption must be decreased (holding leisure and home consumption constant) to make an individual indifferent to the household providing unpaid care. Formally, the man's welfare is defined by the condition:

where

superscripts denote equilibrium outcomes associated with household level of care need

. Under the assumed log preferences, the welfare condition may be explicitly written:

For example, a

implies the man would be indifferent between giving up 10 percent of his baseline market consumption or the household equilibrium outcomes associated with care need

.

Women's welfare is given by the modified condition:

The only difference with men's welfare is that the woman directly values caregiving and is increasingly hurt by higher levels of unmet care needs. To be clear, while we will sometimes refer to our welfare results as the cost of caregiving, there is also an included welfare cost for the woman due to any care needs of her parent that are left unmet.

Results

We next compare equilibrium allocations with and without parental care needs. Specifically, we compare the baseline of no care needs to an equilibrium with 20 hours of care needs per week

. A summary of equilibrium results is provided in . Let us first focus on results under flexible labor markets. Recall that by Proposition 3, it is optimal for the woman to provide all 15 hours of unpaid care.Footnote10 As a result, her labor supply is 6.0 hours (16.3 percent) lower and home production 1.1 hours (5.3 percent) lower with unpaid caregiving. The remaining 7.8 hours devoted to care comes at the expense of her leisure time. While the man in the caregiving household does not provide any care, he increases his labor supply 2.1 percent (0.8 hours per week) and reduces home production the same proportion as the woman (in accordance with Proposition 4 and condition [7]). The lower labor supply of the woman (and higher for the man) results in a lower earnings ratio and bargaining weight in the care providing household –

compared to 0.42 in the no care baseline.

Table 2 Equilibrium with and without parental care (France)

Net declines in market and home production lead to lower consumption levels with unpaid care. As the bargaining weight directly determines the household sharing rule, market and home consumption is significantly lower (11.9 percent) for the caregiving woman but only slightly lower (0.5 percent) for her partner. Unmet care combined with substantially less leisure time and lower consumption levels for the caregiving woman results in a welfare measure . The non-caregiving woman would give up to 41 percent of her market consumption to avoid the equilibrium outcomes of the caregiving woman. In contrast, the man would only give up 1 percent of his market consumption to avoid the unpaid care equilibrium. In other words, the welfare burden of unpaid caregiving to the man is only 3 percent that of the woman.

The final columns in show the equilibrium for France with 20 hours of care needs but holding men's and women's labor supply fixed at the baseline (no care) level. Note that with fixed labor supply, bargaining power remains constant. In France, the non-negativity constraint on the man's caregiving binds, and the woman provides all unpaid care. To allow for this care without changing labor supply, she reduces home production by 3.8 hours and leisure by 9.0 hours. In this case, the French woman in the no care equilibrium is willing to give 39 percent of her market consumption to avoid the caregiving equilibrium. Note that this welfare burden is less than under flexible labor markets, highlighting that flexibility does not unequivocally improve outcomes for women.

In lieu of increasing labor supply, the French man increases home production in the presence of parental care needs. This results in a small 1.1 percent decline in leisure. He also suffers from lower consumption of the domestic good due to lower home production hours of the woman. On net, the welfare cost of caregiving to the French man is 5 percent of baseline market consumption, or about 13 percent of the welfare loss of the woman. Thus, the welfare burden is somewhat more equitably shared with fixed labor supply. However, unmet care needs reach 7.2 hours, or about 44 percent higher than with flexible labor markets. Thus, there is also an implied shift in the welfare cost toward the care recipient, though explicitly quantifying this welfare cost is outside the scope of the current model. Nonetheless, this highlights the potential spillover value of flexible labor markets on care recipients.

Cross-country

We turn now to a cross-country comparison of dual-earning couples in European countries with available data in SHARE. The primary objective of this comparison is to highlight how differences in bargaining power structures influence the distribution of welfare when parental care needs are introduced.Footnote11

Calibration

Parameters governing preferences and home production are assumed to be common across all countries and are left at the values calibrated for France.Footnote12 However, we allow two parameters to vary across countries in our numerical exercise. First, we change relative market wage rate to the aggregate wage ratio between women and men reported in our SHARE sample for dual-earning couples in each country. Second, we calibrate baseline bargaining power

to match the ratio of women to men hours worked for each country (Proposition 2 ensures identification of this moment).Footnote13 Similar to France, for

to be an equilibrium with endogenous bargaining power in country

, it must be that

, where

is the baseline equilibrium earnings ratio in the country. This pins down parameter

and implies the power earnings function will differ across countries through

.Footnote14 Differences in

across countries reflects differences in relative altruism of women, institutions, culture, laws, and other factors that map relative earnings into bargaining power.

We assume households in all countries realize the same level care needs (20 hours per week) and do not explicitly model differences in public policy or social norms regarding care provision across countries. In practice, such differences could impact our welfare comparisons. For example, a country like Germany, with relatively low calibrated bargaining power of women compared to Spain, might have a smaller welfare burden for women given similar parental health due to the universal coverage of long-term care insurance and lower reliance on family care.

Baseline features

The first four columns in provide a comparison of average hours worked in the baseline model (no parental care needs) and the data for each country. Average labor supply of women in our SHARE sample ranged from 30.0 hours a week in the Netherlands to 42.9 hours in Poland. There was less variation in labor supply of men, ranging from 40.8 hours in the Netherlands to 48.3 in Israel. The gender gap in labor supply ranged from 2.5 hours a week in Estonia to 13.3 hours in Switzerland. Recall our baseline was calibrated to match relative labor supply between genders within each country. Overall, the baseline model also gives a reasonable approximation of average labor supply levels for men and women across countries (correlation coefficient of 0.82 for women's labor supply and 0.12 for men).

Table 3 Cross-county calibration

The last five columns in provide some additional features of the baseline calibration. Gender wage ratios (estimated directly from SHARE data) ranged from 0.71 in Germany to 0.91 in Sweden and Belgium. As expected, higher wage ratios are associated with higher bargaining weights for women

(correlation coefficient of 0.9). Women in a country with a large estimated gender wage gap generally have lower bargaining power than in countries with small wage gaps (for example,

in Poland compared to

in Sweden). However, even countries with similar wage ratios can differ in calibrated bargaining weights based on observed labor supply gaps. Take the case of Switzerland and Italy. Both countries have the same gender wage ratio:

. However, the targeted labor supply ratio is 0.89 in Italy compared to 0.71 in Switzerland. In order to rationalize this difference within the structure of the current model, it must be that the baseline equilibrium bargaining weight is lower in Italy than in Switzerland. This lower

results in more hours supplied by women in Italy and hence, rationalizes the observed higher labor supply ratio.

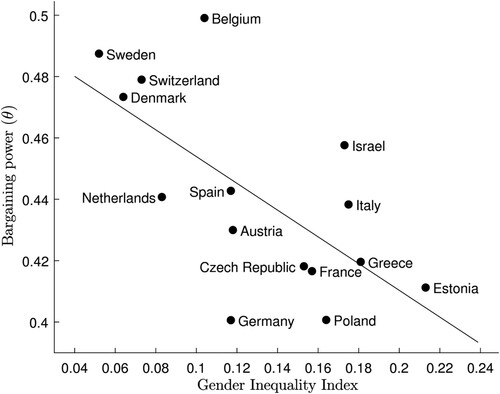

As an external comparison, plots our estimated bargaining weights against the United Nations Development Programme's Gender Inequality Index (GII). The GII is a composite measure that incorporates gender inequality on dimensions related to reproductive health, political and educational empowerment, and labor market participation. Notably, the GII suggests the calibrated bargaining weight may be somewhat too high in Belgium and Israel and too low in Germany and Poland. However, overall bargaining power maps reasonably well to the GII (correlation coefficient of ).

Across all countries, our model predicts that the woman partner supplies more hours to home production than the man – ranging from 20 percent more in Sweden to nearly double in Germany. In Switzerland, where bargaining power of women is high but the wage ratio is about average, the woman enjoys 12 percent higher leisure than the man. In contrast, low bargaining power in Poland and Estonia results in a woman's leisure time equal to only 91 percent of her partner.

Results

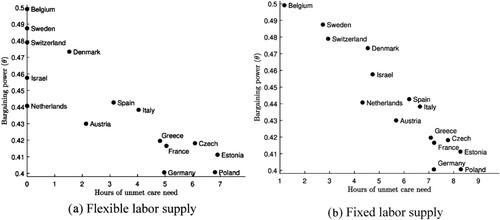

plots the relative welfare costs of 20 hours of care needs against each countries’ baseline bargaining weight. Results are provided for flexible and fixed labor supply. In both cases, the welfare burden of unpaid care shifts toward the man as increases. Recall the relative welfare cost to the man in France was estimated at 3 percent of the woman with flexible labor markets

. This estimate for France is included in panel (a) of the figure. As shown in panel (a), in a few countries (for example, Estonia), men's welfare is slightly higher in the unpaid care equilibrium due to increased bargaining weight (that is, the relative welfare cost is negative). In contrast, the relative burden is about half as high for men in Sweden and Switzerland and fully shared between genders in Belgium.

Figure 4 Relative welfare cost of 20 hours of care needs . (a) Flexible labor supply, (b) Fixed labor supply

Panel (b) of plots welfare costs holding labor supply fixed at the baseline (no care) level. Consider Sweden as a complementary case to the French results previously discussed. In Sweden, bargaining power of women is high enough that caregiving is divided between partners – 12.9 hours provided by the woman and 4.4 hours by the man. As the unpaid care equilibrium is an interior solution for Sweden, condition (10) holds and home production is equal across partners.Footnote15 Compared to France, the leisure cost of unpaid care is more evenly divided between partners as well – 15.6 percent loss for the woman and 6.7 percent for the man. These allocations lead to a shift in the welfare cost of care from the woman toward the man, with a welfare ratio of 45 percent for Sweden (compared to 13 percent for France). Unlike France, bargaining power of women is also high enough in Sweden that the woman's welfare is higher under flexible compared to fixed labor supply.

The comparison between France and Sweden highlights the importance of bargaining power in driving the relative welfare burden across partners. Only in three countries with relatively high welfare ratios – Belgium, Sweden, and Denmark – are caregiving hours divided between partners. In all other countries, care continues to fall entirely on the woman. Finally, when the labor supply margin of adjustment is eliminated, the welfare ratio is more condensed across countries – ranging from 11 percent in Poland to 56 percent in Belgium.

Turning to the provision of care, plots hours of unmet care needs for each country across modeling assumptions. In both cases, hours of unmet care needs generally falls with increases in the bargaining weight of women. For example, with flexible labor markets, there are no unmet needs in Belgium but almost seven hours in Poland (recall unmet care needs were calibrated to equal five hours in France in this case). Results are generally consistent with the estimates of Barbara Bień et al. (Citation2013), who find more unmet needs among southern-eastern European countries compared to northern-western European countries. As with France, unmet care needs in all countries are considerably higher when labor supply is held fixed.

DISCUSSION

With the aid of a simple collective model of intrahousehold bargaining, we analyzed the time and consumption allocation decisions and welfare costs associated with unpaid parental caregiving. In our model, a decrease in bargaining power increases an adult daughter's share of the welfare burden and the unmet care needs of her parent. If bargaining power is endogenously determined by relative earnings, the welfare cost of caregiving can fall disproportionately on the woman partner, resulting in a “triple burden” of market work, home production, and caregiving. Under this scenario, public policies compensating or providing allowances for unpaid long-term care could decrease the welfare gap within a household by providing financial relief and improving the bargaining position of the caregiver. This could further result in reduced levels of unmet care needs and improved welfare of elderly care recipients.

However, gender-neutral policies that directly or indirectly compensate unpaid care run the risk of reinforcing or promoting specialization in care by women. Specialization could further weaken individual or collective bargaining power of women, perpetuate gender stereotypes, and stagnate progress toward equality (Folbre Citation2017). A more socially advantageous long-term goal would include the elimination of the gender wage gap and promotion of social norms to encourage a more equitable division of care across genders. For example, policies such as paid paternal leave in many Nordic countries could be adapted to include gender-aware eldercare leave policies. This would increase the incentive to share the provision of care across partners and lead to a more equitable distribution of bargaining power.

Another policy direction would be to subsidize paid parental care. For instance, in the US, premium paid on long-term care insurance (LTCi) for the taxpayer and/or their dependents is tax deductible. However, these deductions are somewhat limited and are dependent on the age and income level of the taxpayer. Increasing the generosity of these deductions could potentially encourage more families to purchase LTCi for their dependents, which would subsequently reduce the burden of unpaid care provided by family members.

An additional policy insight of our analysis is that flexible labor markets do not unequivocally result in a more gender-equitable burden of care. On one side, policies that promote flexibility in number of working hours, such as caregiver leave or part-time options, could provide substantial relief to care recipients and time-constrained caregivers. On the other hand, our model highlights that such policies may allow men to exert their power over intrinsically motivated women to further reduce women's labor supply, bargaining power, and welfare. This may be of particular concern in areas with relatively low bargaining power of women to begin with, such as Southern Europe.

While our simple model demonstrates the potential quantitative influence of bargaining power within a household, other considerations are warranted if robust counterfactual policy experiments are desired. Note that we have limited our analysis to labor market rigidities that restrict the ability of partners to adjust their number of hours worked. Other types of rigidities could also have welfare implication by limiting the ability to freely allocate time across the day or week. For example, a fixed 9–5 work schedule may limit the ability to provide care at certain times of day. In this case, policies that promote the ability to adjust work schedules, such as flexible shifts or flextime, could alter outcomes for care recipients and caregivers even if they choose to keep total hours worked unchanged. Empirical evidence also suggests unpaid caregiving lowers labor supply on both the extensive and intensive margins in some contexts. Incorporating partially indivisible labor supply and additional heterogeneities across households could yield additional insights.

While our modelling scenarios consider an endogenous change in bargaining power in response to caregiving, additional dynamic considerations could also play an important role. In particular, a less tractable model could consider how current decisions influence future care needs or bargaining positions. For example, leaving sizable unmet care needs could yield further declines in parental health. Or, if there are re-employment costs, women may be less willing to lower labor supply, as this would imply giving up current as well as future bargaining power. While this possibility partially motivated our fixed labor supply scenario, it would be insightful to analyze how this plays out in a more fully developed intertemporal model. We hypothesize this could further skew the care burden across genders.

It is also important to highlight that total welfare costs may be underestimated in our model if caregiving is accompanied by additional market expenses (for example, food, medicine, and so on) or if some elder caregivers are simultaneously providing childcare. Negative effects on caregiver health have also been well documented (Bauer and Sousa-Poza Citation2015), suggesting the welfare burden may be further skewed toward those actually providing care. While most existing empirical research has focused on labor market outcomes, our results also suggest that future work should examine the empirical link between caregiving and total time allocation patterns, including other forms of home production. Finally, while unpaid care continues to play a vital role in most countries, increased reliance on formal care markets is an important additional margin for consideration in future work.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (615.5 KB)ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank James Heintz and seminar participants at the International Association for Feminist Economics Annual Conference for their helpful comments and suggestions on the analysis.

SUPPLEMENTAL DATA

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2021.1975793https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2021.1975793.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ray Miller

Ray Miller is Assistant Professor of Economics at Colorado State University.

Neha Bairoliya

Neha Bairoliya is Assistant Professor of Finance and Business Economics in the Marshall School of Business at the University of Southern California.

Notes

1 In an extension presented in the Supplemental Online Appendix, we also consider a threat point model in which bargaining power is tied to each partner's best outside option.

2 A unitary model would also be at odds with widely documented gender inequality both within a household and at the workplace (Berg and Ferber Citation1983; Blau and Ferber Citation1987; Vogler and Pahl Citation1994).

3 Given that we use log preferences, scaling both partners’ labor time by a common wage rate does not change time allocation or welfare results. Any uniform increase in wage only scales up consumption of the market good.

4 One could also envision an alternate case where a woman's labor supply increases with bargaining power if the man has a strong preference for her to limit market work. This may be the case in some societies. We focus on the case with downward sloping women's labor supply curve. In our benchmark numerical exercise, we focus on European couples where both partners have strong labor force attachment, where the downward sloping curve is likely to hold.

5 As noted above, the figure exogenously holds other time allocations constant (for example, home production). However, Proposition 2 shows that the relationship between bargaining power and labor supply holds even when allowing adjustments on other time margins.

6 We convert all weekly hours to our model by assuming a time endowment of 16 hours a day, 365 days a year, and 50 weeks of work/care. For example, 20 hours a week yields .

7 This includes reportedly helping others outside or inside the household.

8 Hourly wage calculated as reported annual earnings divided by reported weekly hours worked times 52.

9 This implies 15 hours of care a week, which qualifies as “high intensity” caregiving as often defined using a threshold of 10–20 hours a week (Heitmueller and Inglis Citation2007; Lilly, Laporte, and Coyte Citation2010; King and Pickard Citation2013).

10 This is roughly consistent with data from our SHARE sample where more than 80 percent of caregiving households reported only one daily caregiver.

11 An alternate option would be to exogenously change parameters for France and examine results. However, we think a cross-country comparison more directly grounds the analysis in data and allows more intuitive interpretation of results.

12 Given that we use log preferences, scaling productivity across countries in market or home production does not change our results. Any increase in productivity only scales up consumption of that good while welfare results and allocations of time are unaffected.

13 We are unable to use Equation (12) to directly pin down for each country because we do not have hours of home production.

14 Specifically, we have .

15 In our numerical exercise , so condition (10) simplifies to

.

References

- Agarwal, Bina. 1994. A Field of One’s Own: Gender and Land Rights in South Asia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Agarwal, Bina.. 1997. “‘Bargaining’ and Gender Relations: Within and Beyond the Household.” Feminist Economics 3(1): 1–51.

- Agree, Emily M. and Karen Glaser. 2009. “Demography of Informal Caregiving.” In International Handbook of Population Aging, edited by Peter Uhlenberg, 647–68. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Attanasio, Orazio and Valerie Lechene. 2002. “Tests of Income Pooling in Household Decisions.” Review of Economic Dynamics 5(4): 720–48.

- Barczyk, Daniel and Matthias Kredler. 2018. “Evaluating Long-Term-Care Policy Options, Taking the Family Seriously.” Review of Economic Studies 85(2): 766–809.

- Barusch, Amanda S. and Wanda M. Spaid. 1989. “Gender Differences in Caregiving: Why Do Wives Report Greater Burden?” Gerontologist 29(5): 667–76.

- Basu, Kaushik. 1999. “Child Labor: Cause, Consequence, and Cure, with Remarks on International Labor Standards.” Journal of Economic Literature 37(3): 1083–119.

- Basu, Kaushik.. 2006. “Gender and Say: A Model of Household Behaviour with Endogenously Determined Balance of Power.” Economic Journal 116(511): 558–80.

- Bauer, Jan Michael and Alfonso Sousa-Poza. 2015. “Impacts of Informal Caregiving on Caregiver Employment, Health, and Family.” Journal of Population Ageing 8: 113–45.

- Becker, Gary S. 1981. A Treatise on the Family. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Bettio, Francesca and Alina Verashchagina. 2010. “Long-term Care for the Elderly: Provisions and Providers in 33 European Countries.” European Commission. doi:10.2838/87307.

- Berg, Helen M. and Marianne A. Ferber. 1983. “Men and Women Graduate Students: Who Succeeds and Why?” Journal of Higher Education 54(6): 629–48.

- Bianchi, Suzanne, Nancy Folbre, and Douglas Wolf. 2012. “Unpaid Care Work.” In For Love or Money: Care Provision in the United States, edited by Nancy Folbre, 40–64. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Bień, Barbara, Kevin J. McKee, Hanneli Döhner, Judith Triantafillou, Giovanni Lamura, Halina Doroszkiewicz, Barbro Krevers, and Christopher Kofahl. 2013. “Disabled Older Peoples use of Health and Social Care Services and Their Unmet Care Needs in six European Countries.” European Journal of Public Health 23(6): 1032–8.

- Blau, Francine D. and Marianne A. Ferber. 1987. “Discrimination: Empirical Evidence From the United States.” American Economic Review 77(2): 316–20.

- Blumberg, Rae Lesser and Marion Tolbert Coleman. 1989. “A Theoretical Look at the Gender Balance of Power in the American Couple.” Journal of Family Issues 10(2): 225–50.

- Bond, John, Graham Farrow, Barbara A. Gregson, Claire Bamford, Deborah Buck, Paul McNamee, and Ken Wright 1999. “Informal Caregiving for Frail Older People at Home and in Long-Term Care Institutions: who are the key Supporters?” Health & Social Care in the Community 7(6): 434–44.

- Bonke, Jens and Martin Browning. 2009. “The Distribution of Financial Well-Being and Income Within the Household.” Review of Economics of the Household 7: 31–42.

- Braunstein, Elissa. 2015. “Economic Growth and Social Reproduction: Gender Inequality as Cause and Consequence.” UN Women Dicussion Paper Series No. 5. UN Women, New York.

- Byrne, David, Michelle S. Goeree, Bridget Hiedemann, and Steven Stern. 2009. “Formal Home Health Care, Informal Care, and Family Decision Making.” International Economic Review 50(4): 1205–42.

- Chetty, Raj. 2012. “Bounds on Elasticities with Optimization Frictions: A Synthesis of Micro and Macro Evidence on Labor Supply.” Econometrica 80(3): 969–1018.

- Chiappori, Pierre-André. 1992. “Collective Labor Supply and Welfare.” Journal of Political Economy 100: 437–67.

- Costa-Font, Joan. 2010. “Family Ties and the Crowding out of Long-Term Care Insurance.” Oxford Review of Economic Policy 26(4): 691–712.

- Crespo, Laura and Pedro Mira. 2014. “Caregiving to Elderly Parents and Employment Status of European Mature Women.” Review of Economics and Statistics 96(4): 693–709.

- de Meijer, Claudine, Bram Wouterse, Johan Polder, and Marc Koopmanschap. 2013. “The Effect of Population Aging on Health Expenditure Growth: a Critical Review.” European Journal of Ageing 10: 353–61.

- Desai, Sonalde and Devaki Jain. 1994. “Maternal Employment and Changes in Family Dynamics: The Social Context of Women’s Work in Rural South India.” Population and Development Review 20(1) 115–36.

- Doepke, Matthias and Michèle Tertilt. 2016. “Families in Macroeconomics.” In Handbook of Macroeconomics Vol. 2, edited by John B. Taylor and Harald Uhlig, 1789–891. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- Engers, Maxim and Steven Stern. 2002. “Long-term Care and Family Bargaining.” International Economic Review 43(1): 73–114.

- England, Paula, Nancy Folbre, and Carrie Leana. 2012. “Motivating Care.” In For Love or Money: Care Provision in the United States, edited by Nancy Folbre, 21–39. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Folbre, Nancy. 1986. “Hearts and Spades: Paradigms of Household Economics.” World Development 14(2): 245–55.

- Folbre, Nancy. 1997. “Gender Coalitions: Extrafamily Influences on Intrafamily Inequality.” In Intrahousehold Resource Allocation in Developing Countries, edited by Lawrence Haddad, John Hoddinott, and Harold Alderman, 263–74. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Folbre, Nancy. 2017. “The Care Penalty and Gender Inequality.” In The Oxford Handbook of Women and the Economy, edited by Susan L. Averett, Laura M. Argys, and Saul D. Hoffman, 749–66. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Fortin, Bernard and Guy Lacroix. 1997. “A Test of the Unitary and Collective Models of Household Labour Supply.” Economic Journal 107(443): 933–55.

- Gannon, Brenda and Bérengère Davin. 2010. “Use of Formal and Informal Care Services among Older People in Ireland and France.” European Journal of Health Economics 11(5): 499–511.

- Grigoryeva, Angelina. 2014. “When Gender Trumps Everything: The Division of Parent Care Among Siblings.” Working Paper 9. Center for the Study of Social Organization, Princeton, NJ.

- Haberkern, Klaus, Tina Schmid, and Marc Szydlik. 2015. “Gender Differences in Intergenerational Care in European Welfare States.” Ageing & Society 35(2): 298–320.

- Hall, Robert E. 2009. “Reconciling Cyclical Movements in the Marginal Value of Time and the Marginal Product of Labor.” Journal of Political Economy 117(2): 281–323.

- Heitmueller, Axel and Kirsty Inglis. 2007. “The Earnings of Informal Carers: Wage Differentials and Opportunity Costs.” Journal of Health Economics 26(4): 821–41.

- Herr, Marie, Jean-Jacques Arvieu, Philippe Aegerter, Jean-Marie Robine, and Joel Ankri. 2013. “Unmet Health Care Needs of Older People: Prevalence and Predictors in a French Cross-Sectional Survey.” European Journal of Public Health 24(5): 808–13.

- Kabeer, Naila. 1998. “Jumping to Conclusions: Struggles Over Meaning and Method in the Study of Household Economics.” In Feminist Views of Development: Gender, Analysis and Policy, edited by Cecile Jackson and Ruth Pearson, 91–107. New York: Routledge.

- Katz, Elizabeth. 1997. “The Intra-household Economics of Voice and Exit.” Feminist Economics 3(3): 25–46.

- King, Derek and Linda Pickard. 2013. “When is a Carers Employment at Risk? Longitudinal Analysis of Unpaid Care and Employment in Midlife in England.” Health & Social Care in the Community 21(3): 303–14.

- Kotsadam, Andreas. 2011. “Does Informal Eldercare Impede Women’s Employment? The Case of European Welfare States.” Feminist Economics 17(2): 121–44.

- Kudo, Shogo, Emmanuel Mutisya, and Masafumi Nagao. 2015. “Population Aging: An Emerging Research Agenda for Sustainable Development.” Social Sciences 4(4): 940–66.

- Lilly, Meredith B., Audrey Laporte, and Peter C. Coyte. 2007. “Labor Market Work and Home Care’s Unpaid Caregivers: A Systematic Review of Labor Force Participation Rates, Predictors of Labor Market Withdrawal, and Hours of Work.” Milbank Quarterly 85(4): 641–90.

- Lilly, Meredith B., Audrey Laporte, and Peter C. Coyte. 2010. “Do They Care Too Much to Work? The Influence of Caregiving Intensity on the Labour Force Participation of Unpaid Caregivers in Canada.” Journal of Health Economics 29(6): 895–903.

- Lundberg, Shelly J., Robert A. Pollak, and Terence J. Wales. 1997. “Do Husbands and Wives Pool Their Resources? Evidence from the United Kingdom Child Benefit.” Journal of Human Resources 32(3): 463–80.

- Mader, Katharina and Alyssa Schneebaum. 2013. “The Gendered Nature of Intra-household Decision Making In and Across Europe.” Working Paper No. 157. Department of Economics, Vienna University of Economics and Business.

- Mencher, Joan. 1988. “Women’s Work and Poverty: Women’s Contribution to Household Maintenance in South India.” In A Home Divided: Women and Income in the Third World, edited by Daisy Dwyer and Judith Bruce, 99–119. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Norton, Edward C. 2000. “Long-term Care.” In Handbook of Health Economics 1B, edited by Anthony J. Culyer and Joseph P. Newhouse, 955–94. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- Pezzin, Liliana E. and Barbara Steinberg Schone. 1999. “Intergenerational Household Formation, Female Labor Supply and Informal Caregiving.” Journal of Human Resources 34(3): 475–503.

- Riley, Nancy E. 1997. “Gender Power and Population Change.” Population Bulletin 52(1): 1–46.

- Shrestha, Laura B. 2000. “Population Aging In Developing Countries.” Health Affairs 19(3): 204–12.

- Spiess, C. Katharina and A. Ulrike Schneider. 2003. “Interactions Between Care-Giving and Paid Work Hours among European Midlife Women, 1994 to 1996.” Ageing & Society 23(1): 41–68.

- Twigg, Julia and Karl Atkin. 1994. Carers Perceived: Policy and Practice in Informal Care. Maidenhead, UK: McGraw-Hill Education.

- Van Houtven, Courtney Harold, Norma B. Coe, and Meghan M. Skira. 2013. “The Effect of Informal Care on Work and Wages.” Journal of Health Economics 32(1): 240–52.

- Vogler, Carolyn and Jan Pahl. 1994. “Money, Power and Inequality Within Marriage.” Sociological Review 42(2): 263–88.

- Wakabayashi, Chizuko and Katharine M. Donato. 2005. “The Consequences of Caregiving: Effects on Women’s Employment and Earnings.” Population Research and Policy Review 24(5): 467–88.