?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The aim of this study is to develop a feminist Post-Keynesian/Post-Kaleckian model to theoretically analyze the effects of labor market and fiscal policies on growth and employment. The study develops a three-sector gendered macroeconomic model with physical and social sectors (health, social care, education, childcare) in the public and private market economy, and an unpaid reproductive sector providing domestic care. It provides a theoretical analysis of the effects on GDP, productivity, and employment of men and women in both the short and long run, as a consequence of (1) fiscal policies, in particular public spending on social infrastructure, and (2) decreasing gender wage gaps, particularly within the social sector dominated by women. This theoretical analysis provides a basis to further analyze the impacts of an upward convergence in wages, other types of fiscal spending, and taxes.

HIGHLIGHTS

The study develops a feminist Post-Keynesian model to aid policy analysis and gender-responsive budgeting.

Public social expenditure decreases gender inequality by reducing women’s unpaid work burden.

Social spending creates more employment for women than physical infrastructure and closes gender gaps in employment.

Social spending can increase productivity, partially moderating the employment impact of spending.

If the economy is wage-led, more progressive taxes increase output.

INTRODUCTION

The aim of this paper is to develop a feminist Post-Keynesian/Post-Kaleckian model to theoretically analyze the effects of labor market and fiscal policies on output, productivity, employment of men and women, and public sector budget balance. The model aims to support empirical analysis of gender macroeconomic policies in developing countries and explore the conditions for a broader concept of development including gender-equitable human development.

We synthesize and extend the gendered macroeconomic models by Elissa Braunstein, Irene van Staveren, and Daniele Tavani (Citation2011) and Stephanie Seguino (Citation2010, Citation2012), who incorporate both demand and supply-side effects of gender equality in structuralist, Post-Keynesian/Post-Kaleckian models.

The importance of Post-Keynesian/Kaleckian macroeconomic models for our purposes is that it puts inequality at the heart of the determination of demand and output, as they integrate the dual role of wages as cost and as source of demand. These models accept the direct positive effects of higher profits on private investment and net exports as emphasized in mainstream models, contrasting these positive effects with the negative effects on consumption. Demand plays a central role in determining output and employment, and the distribution of income between workers and capitalists (wages and profits) has a crucial effect on demand. An increasing wage share in national income or higher gender equality can have both positive and negative effects on output. These models allow for involuntary unemployment, underemployment, and excess capacity (Onaran Citation2016). This approach is different from the neoclassical macroeconomic models based on microeconomic decisions of optimizing agents. Components of aggregate demand are determined by behavioral equations. Wages are an outcome of a bargaining process between employers and workers as opposed to the neoclassical theory, where they are determined by the marginal product of labor. Furthermore, from a feminist political economy approach, the gender wage gap is determined by the relative bargaining power of men and women vis-a-vis capital, which for the purpose of this article is considered as exogenously determined. Similarly, social norms may lead to a lower probability of women completing secondary and/or tertiary education in many countries around the world, which also creates a systemic disadvantage for them in the labor market. Moreover, social norms lead to women doing a higher share of unpaid care work and less market work. Neoclassical labor supply is based on the choice between leisure and consumption. The difference between the demand-led models of output and employment is that unemployment is involuntary. Labor supply is inelastic, and employment is demand-constrained, not supply-determined.

Neoclassical macroeconomic models on the effects of gender inequality focus on the supply side, in particular, the effects of intrahousehold bargaining on fertility, savings, and human capital (Agenor and Agenor Citation2014; Doepke and Tertilt Citation2016; Fukui, Nakamura, and Steinsson Citation2019); however, they do not analyze the demand-side effects and ignore how demand constraints may lead to involuntary unemployment if an increase in gender equality in education or a decline in labor market imperfections, such as wage discrimination and occupational segregation, lead to higher women’s labor force participation (WLFP). They also do not analyze the effects of higher WLFP squeezing unpaid care in the absence of public provision of social infrastructure. On the contrary, a rise in public spending in social infrastructure may lead to even negative effects on output as neoclassical models would not allow for high multiplier effects of public spending; investment is determined simply by savings rather than a behavioral model, and higher government spending leads to higher public borrowing and may even lead to lower private investment. Lower gender pay gap in the public sector leading to higher deficit may lead to similar negative effects in a neoclassical model.

Among the feminist structuralist, Post-Keynesian/Post-Kaleckian models, Seguino (Citation2012) explicitly incorporates the public sector, the effect of public investment in physical and social infrastructure on private investment. Seguino (Citation2010, Citation2012) presents both a short- and long-run analysis incorporating endogenous technological change including the effects of gender equality, demand, and public spending on productivity. Braunstein, van Staveren, and Tavani (Citation2011) incorporate the effects of unpaid work and care as a gendered input into the market output, but they do not explicitly model the public sector or endogenous technological change, although the effects of care input on productivity is implicitly discussed. All three papers recognize the structural features of an economy that relies on human services or traditional sectors that primarily employ women, but essentially the analysis is at an aggregate level without explicit modeling of sectoral output or employment of different sectors. Modeling and analysis of paid employment at a sectoral level is also not detailed; in particular, the separate and opposite effects of an increase in output and productivity on employment is not analyzed. While Seguino (Citation2012) and Braunstein, van Staveren, and Tavani (Citation2011) focus on the closed economy, Seguino (Citation2010) details the effects of gender equality on the balance of payments, furthering earlier work by Robert A. Blecker and Stephanie Seguino (Citation2002) and Korkut Ertürk and Nilüfer Çağatay (Citation1995).

Synthesizing and extending these three feminist structuralist, post-Keynesian/post-Kaleckian macroeconomic models, we develop a three-sector gendered open economy model with physical and social sectors (health, social care, education, childcare) in the public and private market economy, and an unpaid reproductive sector providing domestic care. The production in the market economy is performed by men’s and women’s paid labor and capital.

On the demand-side, we model behavioral equations for household consumption in physical and social sectors, private investment, net exports, taxes, and government investment in physical and social infrastructure and current government spending.

An explicit modeling of consumption in different sectors has important consequences for gendering macroeconomic analysis. Higher gender equality in wages or employment could change the composition of consumption. By modeling consumption in two different market sectors explicitly, we allow for a formal analysis of the effects of different behavior by women and men in terms of marginal propensity to consume (MPC) out of their income on different types of goods and services. While there is macro-econometric evidence that the MPC out of wages are higher than that out of profits (see Onaran and Galanis [Citation2014] for a review), micro-level evidence shows that the propensity to save is higher for women than men, and women tend to devote a larger share of their income to satisfy the needs of the household or on social expenditures like education and healthcare compared to men (Blumberg Citation1991; Pahl Citation2000; Seguino and Floro Citation2003; Stotsky Citation2006; Morrison, Raju, and Sinha Citation2007; Antonopoulos et al. Citation2010). In developing countries, women are also more likely to consume domestically produced goods, while men are more likely to consume a higher proportion of luxury and/or imported goods, such as cell phones, automobiles, and televisions (Kabeer Citation1997; Seguino Citation2010, Citation2012).

The analysis of the government sector, in particular, the disaggregated modeling of social versus physical infrastructure is also crucial for a gendered macroeconomic analysis. The development of the social sector in the market economy with services provided by paid labor will have profound effects on women as well as on aggregate macroeconomic outcomes (Folbre Citation1995; Onaran Citation2016). First, on the supply side, this will reduce the need for unpaid labor to provide care, education, and health, and improve the chances of women to participate in the paid economy. Second, on the demand side, given the current rates of occupational segregation, the new jobs generated in the social sector will be jobs traditionally held by women and thereby increase the employment chances of women. Third, both the public supply of social services and increased paid employment opportunities could transform gender norms concerning division of labor (Folbre and Nelson Citation2000). Furthermore, public investment in times of underemployment/unemployment can compensate for the lack of effective demand in the economy. On the supply side, productivity in the physical sector is exogenous in the short run and endogenously changes in the long run, and is a function of public physical and social infrastructure, household spending in the social sector, unpaid domestic care labor, wages of men and women, and growth.

We explicitly model paid employment of women and men in separate sectors and not just output. Employment (in hours) is determined by output in different sectors and endogenously changing labor productivity.

Demand influences output both in the short and long run, as the model builds on realistic structural features of a capitalist market economy operating with excess capacity and involuntary unemployment. Gendered structural features regarding both the paid and reproductive unpaid labor such as gendered sectoral composition of employment, occupational segregation, institutions, and social norms regarding gendered consumption behavior, as well as the distribution of unpaid domestic care labor affect output, productivity and, employment. The model considers the role of unpaid domestic work, in particular, its positive effects on labor productivity in the long run. Through its effect on productivity, unpaid care work also affects output in the long run.

We provide a theoretical analysis of the effects on Gross Domestic Product (GDP), productivity (GDP per employee), and employment of men and women in both the short and long run as a consequence of (1) fiscal policies, in particular public spending in social infrastructure, and (2) decreasing gender wage gaps, in particular in the social sector, which tends to be dominated by women. This theoretical analysis provides a basis to further analyze the impacts of (1) particular paths to closing gender wage gaps, for example, via an upward convergence in wages, that is, an increase in both men’s and women’s wages with a faster increase in the latter; (2) other types of fiscal spending, and (3) taxes on labor and capital income.

We examine the impact of labor market and fiscal policies on each component of aggregate output, which helps to identify the mechanisms of the effects. The model examines both short- and long-run effects and presents the difference between them. Crucially, a change in gender pay gap or the functional distribution of income between wages and profits or public spending in social versus physical infrastructure have both demand-side effects in the short- and long run and supply-side effects in the long run and affect output, productivity, and the employment and income of men and women. For example, we expect public investment in social infrastructure to reduce women’s unpaid domestic care work and increase their employment. The model anticipates that aggregate demand is stimulated both in the short and the long run. Due to sectoral and occupational segregation, public spending in social infrastructure is expected to create more employment for women compared to physical infrastructure. In the long run, government spending and higher women’s income is expected to increase productivity, which may partially moderate the positive impact of fiscal spending on employment; hence there are opposite effects of output and productivity on employment. The long-run impact on productivity also depends on how much of the rise in paid employment decreases unpaid care labor and whether public spending in social infrastructure can more than offset the effects of the decline in unpaid domestic care labor.

As each variable corresponds to concrete variables available in national accounts or labor force statistics, the behavioral equations in the theoretical model can be econometrically estimated and the analytical solutions in the appendices can be used to calculate the effects of different policies.

A FEMINIST POST-KALECKIAN THEORETICAL MODEL

In the following, we develop the model with two types of workers, women and men, which are respectively denoted by scripts F and M. The profits are earned by the capitalists, which are genderless for simplicity.

The model has three sectors: public social sector, which consists of the expenditures of the government in education, childcare, healthcare, and social care (denoted with script H) the rest of the economy (denoted with script N); and the unpaid care sector.Footnote1 The public spending in this social sector is defined as investment in social infrastructure in line with the feminist economics literature (Women’s Budget Group Citation2015; Elson Citation2016, Citation2017). We also introduce household’s spending in marketized social services. Both public and household’s social expenditures have short-run demand effects and influence labor productivity in the long run. Supplemental Online Appendix 1 presents list of the variables in the model.

Aggregate output () is the sum of men’s and women’s wage bill (

and

) and profits (

).

(1)

(1)

The total wage bill for women workers (

) is a function of women’s wages in the social sector (

), women’s employment in the social sector (

), women’s wages in the rest of the economy (

), and women’s employment in the rest of the economy (

):

(2)

(2)

Similarly, the total wage bill for men workers () is a function of men’s wages in the social sector (

), men’s employment in the social sector (

), men’s wages in the rest of the economy (

), and men’s employment in the rest of the economy (

):

(3)

(3)

The data for selected emerging economies in show that average hourly men’s wages in the social sector are higher than average hourly women’s wages for most of the developing economies with an exception of three (out of thirty-eight) countries. Moreover, in thirty-one out of thirty-eight countries average hourly men’s wages in the rest of the economy are higher than average hourly women’s wages. There is also significant occupational/sectoral segregation with women constituting the majority in the social sector and are substantially underrepresented in the rest of the economy.

Table 1 The women’s employment share and average hourly men’s wage/women’s wage ratio in selected emerging economies

We define gender wage gaps () for wages in H and N as below:

(4)

(4)

Following we consider that

is more likely for the majority of the developing economies and

condition applies to most of the developing economies. The aggregate output in the market economy (GDP) is

(5)

(5)

where

is households’ social expenditures,Footnote2

is consumption in the rest of the economy,

is private investment expenditures,

. is government’s social infrastructure expenditures,

is government’s consumption expenditures,

is public investments other than investments in the social sector,Footnote3

is exports of goods and services, and

is imports of goods and services. The public social expenditures are a fiscal policy decision targeted as a share of aggregate output (

) and constitute the public social sector output (

).Footnote4 The rest of the GDP is the market output in the rest of economy (

):

(6)

(6)

(7)

(7)

The share of government’s consumption expenditures (

) and public investments other than social infrastructure investment in the social sector (

) are also determined by the government as a share of aggregate output and are respectively

and

:

(8)

(8)

(9)

(9)

The employment in N is output over labor productivity in N

:

(10)

(10)

The share of women’s employment in N is exogenous and institutionally and socially determined by occupational segregation and is denoted by . The men workers in N constitute

of the sector:

(11)

(11)

(12)

(12)

shows that the number of men workers is greater than the number of women workers in N for all the emerging economies reported. Hence, is a likely outcome for an emerging economy.

We assume that the wage bill paid to men and women workers in the social sector constitutes the public social expenditures and the social sector is not making profits. Any non-labor inputs used constitute part of government consumption (). The public social expenditure can be written as a function of employment (

), average women’s wage (

), average men’s wage (

), women’s employment share (

), and men’s employment share

in the social sector.

(13)

(13)

Using Equations 13 and 4, we can write the total employment (

), women’s employment (

), and men’s employment (

) in the social sector as a function of public social expenditures and women’s wages in the social sector.

(14)

(14)

(15a,b)

(15a,b)

In , we observe that the share of women workers in H is larger than the share of women workers in N for all countries. Moreover, in 80 percent of emerging economies in , the share of women workers in H are over 50 percent. Therefore, a rise in the share of H in aggregate output would also increase the share of women workers in total employment in the majority of the cases.

We model the unpaid domestic care labor () within the households as

(16)

(16)

For a given demographic structure defining care needs of a society

, the higher men’s and women’s paid employment is expected to have some negative impact on the supply of unpaid labor, since it would decrease the time that could be allocated for care (

). Higher government expenditures in H are also expected to reduce the need for domestic care; therefore, it would lead to lower unpaid labor (

). We specify the equation in logs, since the impact of employment in N and public social expenditures on the time spent on unpaid domestic care might be non-linear (the negative impact might be decreasing in absolute values as it gets increasingly more difficult to decrease unpaid care at lower levels of unpaid care).

Next, we define the profits (R) in N. The profits are earned by the capitalists and are their income in N after wage payments.

(17)

(17)

The profit share in N is the share of profits in the output in N. Therefore, the profit share could also be written as a function of women’s wages and labor productivity in N:

(18)

(18)

The next set of equations presents the behavioral equations defining the demand-side of the model. Consumption of households in goods and services other than social expenditures is a function of total wage income of women and men workers in H and N and profit income of capitalists after taxes. is the rate of tax on wages and

is the rate of tax on profits. Following previous empirical literature (Hein and Vogel Citation2009; Onaran and Galanis Citation2014; Molero-Simarro Citation2015; Onaran and Obst Citation2016) in the post-Kaleckian literature that estimates the relationship between consumption, wages, and profits in logarithms, we define the logarithm of non-social consumption as functions of logarithms of after tax profits, and women’s and men’s wage bills in H and N. The non-linearities in the relationship between sources of incomes and consumption might be an outcome of changing propensities to consume with changing incomes.

(19)

(19)

The marginal propensity to consume in N is assumed to be different for men and women workers in N, reflecting the gender pay gaps as well as differences in behavior.

The households’ social expenditures () is also a function of after-tax profits and wage bills of female and male workers in N and H, and governments’ social expenditures:

(20)

(20)

The marginal propensity to consume social goods is different for men and women workers in N. We assume that the marginal propensity to consume social goods is the same for men and women workers working in the social sector in an attempt to simplify the model.Footnote5 Following this assumption, governments’ social expenditures (

) can (i) increase households’ social expenditures by providing wage income in H, and (ii) decrease households’ social expenditures by reducing the need for these expenditures. We assume that the demand for

is provided by the private sector in the market economy as part of the output in N, as mentioned above.

Next, private investment () is

(21)

(21)

where

is public debt. The private investment is expected to increase as a result of higher aggregate output

is the after-tax share of disposable profits in N. Following Amit Bhaduri and Stephen Marglin (Citation1990), we expect the profit share to have a positive direct impact on private investment (

). Last, we use the ratio of public debt to GDP,

to consider the possible negative crowding out effects of rising public debt on the interest rate and thereby, private investment (

), as in Thomas Obst, Özlem Onaran, and Maria Nikolaidi (Citation2020).

The public debt at time t () is the public debt accumulated from the public debt in the previous period (

) with an interest rate of

, plus the total government expenditures at t, minus the taxes collected from profits and wages at time t.

(22)

(22)

Exports are shown by

:

(23)

(23)

The income of the trading partners () and the real deprecation in currency (

) increases the exports (

). A rise in the profit share is equivalent to a fall in real unit labor costs and, hence, would increase the export competitiveness and, hence, exports of an economy (

). Imports are shown by

:

(24)

(24)

Higher domestic demand in N would stimulate the demand on imported goods and services (

) and the real deprecation in currency (

) reduces the imports (

). A rise in the profit share would decrease imports because it would increase the competitiveness of domestic goods against imported products.

This is a reduced form modeling of the relative price effects on exports and imports. Domestic prices and export prices are functions of nominal unit labor costs, based on a mark-up pricing model in an imperfectly competitive economy. Exports are a function of relative prices of exports to imports, and imports are a function of domestic prices relative to import prices. As nominal unit labor costs are real unit labor costs multiplied by domestic prices, and the wage share is identical to real unit labor costs, a fall in the wage share, that is, a rise in the profit share, leads to a fall in relative prices and improves net exports, depending on the labor intensity of exports, that pass through from labor costs to export prices and domestic prices and the price elasticity of exports and imports. To simplify the model, we do not present the price equations and relative price effects on net exports.

Our claim on the impact of profit share on net exports is also supported by the previous empirical literature. For seven large emerging economies (Turkey, South Korea, Mexico, China, India, Argentina, and South Africa), Özlem Onaran and Giorgos Galanis (Citation2014) find that an increase in profit share increases net exports. Similarly, Ensar Yılmaz (Citation2015) and Bruno Jetin and Ozan Ekin Kurt (Citation2016) also respectively find a strong positive impact of profit shares on net exports in Turkey and Thailand. Germán Alarco (Citation2016) finds a negative impact of wage share on net exports in sixteen Latin American countries, although the impact for some of the countries is insignificant.

Finally, on the supply-side of the model, labor productivity is constant in the short run and changes endogenously in the long run in the rest of the economy, as we assume technological change or adoption of new techniques take time. We assume productivity in H is given and simply equal to output per hour of employment in both the short and the long run.Footnote6 Labor productivity in N () is

(25)

(25)

In the long run, the labor productivity is likely to be positively influenced by lagged values of government’s social infrastructure investment as well as government’s consumption expenditures and other public investment (

,

). We also expect households’ consumption expenditures in marketized social services (CH) and domestic unpaid care laborFootnote7 to affect labor productivity positively (

,

). Nevertheless, we expect the effects of these to be realized over the long run, namely in the next period. The higher output would also lead to higher labor productivity due to Verdoorn effect (Naastepad Citation2006; Hein and Tarassow Citation2010), as greater scale can lead to more efficient allocation of sources (

). Moreover, following Karl Marx (Citation1867) and later the theoretical contributions and empirical findings of C.W.M. (Ro) Naastepad (Citation2006) and Hein and Tarassow (Citation2010), we consider that higher women’s and men’s wages in N leads to capitalists’ preference toward labor-saving technologies, which would increase labor productivity (

). This is also consistent with the new Keynesian efficiency wage theories (Shapiro and Stiglitz Citation1984). Higher output and higher wages have also a lagged effect, since the change in technology and/or techniques pushed by these factors would require time. Last, the labor productivity in the previous period is also positively related with the productivity in the current period, since part of the technology from the last period would be transferred to the following period (

). The next period is a sufficiently long time period for these effects to be realized, for example, five years or more; furthermore, the time required for these different factors to affect productivity is an empirical question. For example, the impact of public investment in childcare may take longer than the impact of other types of government spending or higher wages. In the theoretical model, we abstract from differences in the lag structure of the effects.

Unpaid domestic care labor, U is shared between women (UF) and men (UM), where βd is the share of UF in U, and is exogenous and institutionally and socially determined:

(26)

(26)

(27)

(27)

In case of extreme gender inequality

In our model for simplicity, we do not model the impact of higher public social infrastructure on labor supply, fertility, and migration. Again, for simplicity we ignore the feedback effects of changes in labor supply and consequently unemployment on wages in the long run. Similarly, a rise in wages in a particular sector, for example, H as an outcome of higher public social infrastructure, or a faster increase in wages in the social sector compared to wages in the rest of the economy is likely to lead to higher labor supply of both men and women, leading also to changes in the sectoral segregation ratios in the social sector and the rest of the economy, as well as a change in social gender norms and the distribution of unpaid domestic labor, . The latter may lead to a further change in occupational segregation, for example, a decline in

or an increase in

and lower gender pay gaps in both sectors. While these are interesting extensions, they are outside the scope of this theoretical model, where our primary aim is to analyze the impact of public spending and exogenous changes in wages and gender pay gap on employment of women and men.

THE EFFECTS OF THE PUBLIC SOCIAL EXPENDITURES WITH EMPLOYMENT GENERATION IN THE SOCIAL SECTOR

In the following, we examine the short-run and long-run effects of an increase in the share of social expenditures in GDP on aggregate output, employment, and public debt/GDP. In this section, we analyze the case where public social expenditure increases through new public sector employment in the social sector, that is, hiring more public sector employees in the social sector without changing their hourly wage rate ().

We first examine the effect of social expenditures on aggregate output through direct stimulus by rising government expenditures and employment. Next, we will examine the impact of public social investment in the long run, which will in turn effect labor productivity and public debt/GDP. We will also discuss the overall impact on women’s and men’s employment and public debt/GDP.

The short-run effect of a change in the share of public social infrastructure investment in GDP

We start our analysis with the short-run effect of an increase in the share of public social infrastructure investment in GDP () on output. The overall impact (

) is the sum of the direct impact on GDP and the partial effect on each component of demand multiplied by the multiplier term. These effects are shown in detail in the Appendix.

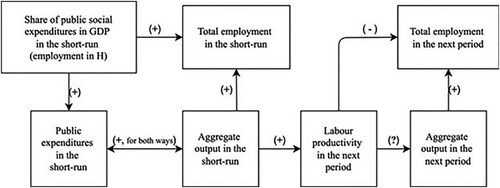

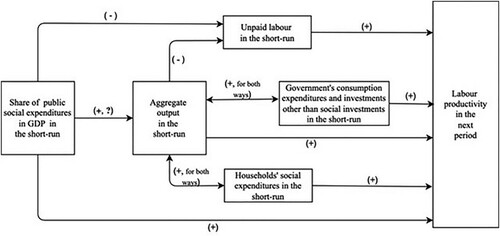

As summarized in , higher public social expenditures will stimulate the consumption in N, since it will generate new employment and income in H. Hence, the short-run effects on consumption in N (apart from the multiplier effects) are due to the partial effect of public social expenditures on women’s and men’s employment. The magnitude of the effect on consumption in N depends on the marginal propensities to consume in H for the women and men workers.

Figure 1 The short-run impact of an increase in the share of public social expenditure in GDP on total output. Notes: *Based on , the positive partial impact of public expenditures is expected to be relatively larger for women’s employment compared to the partial impact from expenditures in N.

The partial effect of the public social expenditures on women’s and men’s employment is positive in the short run as it generates new employment in the social sector and pushes total output to an upper level. Based on the women’s employment shares in and as in the literature (İlkkaracan, Kim, and Kaya Citation2015), we expect the partial impact of public social expenditures on women’s employment relative to men’s employment in the social sector to be larger than the partial effects of all shocks in N (for example, share of government’s consumption expenditures in GDP (), share of public investments other than social infrastructure investment in GDP (

), or autonomous private investment (

)). The partial (pre-multiplier) effect of public social expenditures on women’s and men’s employment in N is zero, as the impact of social expenditures on productivity will be realized only in the next period.

The short-run impact of public social expenditures on consumption in H is ambiguous, but it is likely to be negative. This is because a rise in public social expenditures could reduce the households’ need for social expenditures, although it generates new employment, hence income in the social sector.

For a constant output in N, the short-run partial effect of public social expenditures on private investment is due to higher aggregate output because of increasing public social expenditures as well as higher public debt (

). Higher aggregate output stimulates investment. However, the increase in public social expenditures may lead to an increase in public debt/GDP, which in turn may have a negative effect on private investment (

) in the short run due to the crowding out effect, depending on the effect on the interest rate and interest elasticity of investment. However, the negative effect on public debt/GDP may be moderated as tax revenues as well as GDP increase. The rest of the effects on private investment are due to the multiplier effects of a change in

.

Higher aggregate output stimulates investment. The short-run effect of public social expenditures on the profit share is zero for a constant output in the rest of economy since public social expenditures do not affect labor productivity in the short run. The short run partial effects of public social expenditures on exports and imports are zero for a constant output in N, because its partial effect on the profit share is zero in the short run. Finally, an increase in the public social expenditures/GDP has a positive effect on other types of public investment.

The effect of a change in the share of public social infrastructure investment in GDP in the next period

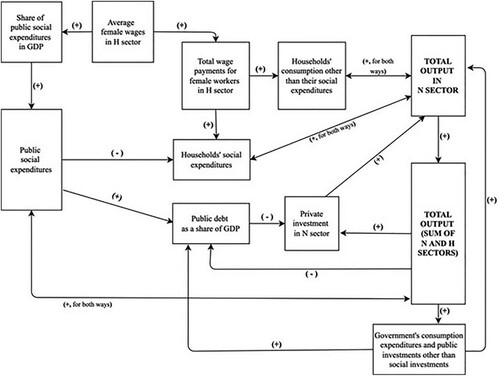

The effect of a rising share of social expenditures in GDP on aggregate output in the next period is the sum of its partial impact on each component of GDP multiplied by the multiplier term. The long-run impact of public social expenditures are summarized in (also in the Appendix). The effect in the next period is due to changes in labor productivity and public debt.

Figure 2 The long-run impact of an increase in the share of public social expenditure in GDP on total output. Notes: All variables without time represent the current period. *The impact of total output on imports is positive, and the impact of imports on total output is negative.

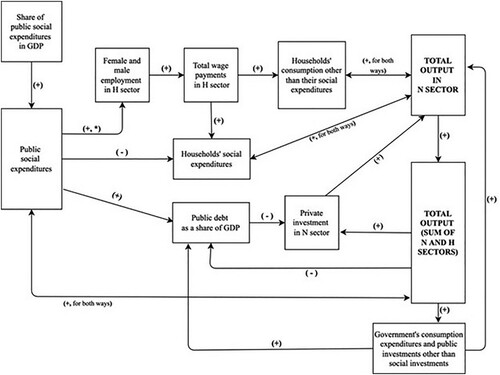

summarizes these effects of an increase in social expenditures/GDP on labor productivity in the next period. First, higher public social investment has a direct positive impact on labor productivity in the next period through better education, childcare, health, and social care. However, the positive effects of public social investment may be slightly reduced due to a decrease in both household consumption in the social sector and unpaid care labor, because public social expenditures reduce households’ need for social expenditures funded by their own income and unpaid care labor within the household, but we expect these effects to be small and non-linear. First, without significant privatization in the social sector, an increase in public social expenditures is very unlikely to lead to a large decrease in households’ social expenditures that would reverse the positive effects of higher public social expenditures on labor productivity. Second, while the unpaid care work is expected to decrease due to higher social expenditures, it is unlikely to be large enough to offset the positive effects of public social expenditures on labor productivity. Therefore, we expect the overall effect of these three components on labor productivity to be positive. Additionally, higher public social expenditures is likely to lead to an increase in output in the short run, which also influences labor productivity in the next period through the Verdoorn effects as well as the increase in the other public expenditures, which increase together with aggregate output. Last, unpaid labor and households’ social expenditures also change along with aggregate output because higher GDP leads to an increase in employment, which reduces the time available for unpaid care but increases household expenditure in the social sector due to higher income.

Figure 3 The impact of the share of public social expenditures in GDP on labor productivity in the next period

Next, we demonstrate the partial long-run impact of public social investment on each component of aggregate demand. First, higher public social investment changes wage income of women and men and profits due to changes in employment, which in turn affects households’ consumption in the social sector and the rest of the economy. For a constant output in N, the partial impact of public social investment on women’s and men’s employment in N is likely to be negative, since higher public social investment is likely to increase labor productivity as discussed above. This changes income distribution in favor of profits and (for a constant output in N) has a negative partial impact on the consumption of women and men workers in N and H and a positive partial impact on the consumption of the capitalists. If public social expenditures also have a positive effect on GDP in the next period, the overall effects on women’s and men’s employment could also be positive as will be discussed further.

The share of public social expenditures affects private investment through the effects on the profit share and public debt/GDP in the long run. The public social expenditures affect labor productivity in the next period, which changes the denominator of public debt/GDP ratio. Moreover, public social expenditures change the distribution between wages and profits, which in turn affect public debt as the tax rates on different types of income are different. Higher public social expenditure is likely to increase the profit share due to higher productivity in the next period and stimulate private investment. Finally, higher public social expenditure has a further positive effect on private investment through the multiplier effects if it leads to greater output in the rest of the economy in the long run. Higher profit share also has a partial positive effect on exports and a negative effect on imports.

In summary, the sign of the effect of public social expenditures on aggregate output in the next period depends on its effects on labor productivity, which in turn affects the profit share and the public debt/GDP and the magnitude of the consequent crowding out effects.

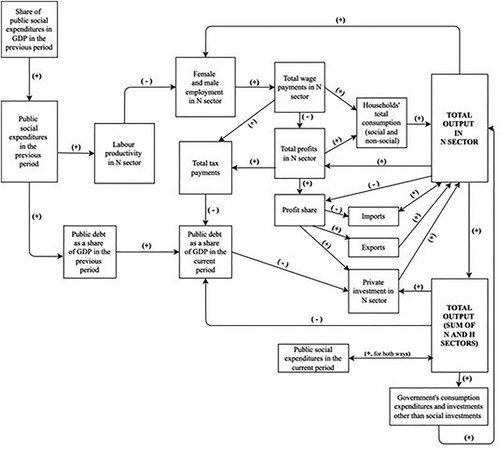

The cumulative effects on employment

A higher share of public social expenditure in GDP affects total women’s and men’s employment in the short run due to higher aggregate output in addition to directly creating employment in the social sector. Higher aggregate output generates further employment both in the social sector and in the rest of the economy. shows that the share of women in hours of employment is greater than 0.5 in 80 percent of the selected emerging countries. Based on this, we expect that the direct impact of an increase in public social expenditures on women’s employment is likely to be larger than its effect on men’s employment in most developing economies.

summarizes the impact of an increase in public social expenditures on employment. We expect an increase in women’s and men’s employment in the short run. In the next period, the effect depends on the relative magnitude of the effects on output and productivity. While higher output increases employment, higher productivity leads to lower labor demand for a given output. If the impact of higher public social expenditures on aggregate output in the next period is positive and large enough to offset the negative effect of higher labor productivity on employment, women’s and men’s employment also increases in the long run. In the unlikely case where the long-run effect of public social expenditures on aggregate output is negative or too small that the negative effect of higher labor productivity dominates, women’s and men’s employment can decline in the next period. The cumulative effect depends on the sum of the short-run and long-run effects. From a Keynesian feminist point of view, we expect relatively strong multiplier effects of government social spending on output and despite substantial labor productivity effects, it is highly likely that cumulative long-run employment, in particular for women, increases in response to an increase in public social infrastructure spending. However, in the unlikely case where productivity effects more than offset the output effects, either other types of public spending or shortening of the working hours with hourly wage compensation could mitigate the negative cumulative effects on employment.

THE IMPACT OF CLOSING THE GENDER WAGE GAP IN THE SOCIAL SECTOR ON OUTPUT, EMPLOYMENT, AND PUBLIC DEBT

In the following, we examine the case in which the share of public social expenditure in GDP increases through closing the gender pay gap in the social sector without a direct increase in employment, that is, without hiring new public sector employees in the social sector (H) at the beginning. Hence, the gender wage ratio,

decreases with a rise in the women’s wage rate in H with a constant men’s wage rate (

). The employment in H is constant (

) prior to the multiplier effects.

The implications of this case are very similar to the case in which public social expenditure increases with hiring new employees in the public social sector. The main difference between the two cases is through the effects on consumption in the rest of the economy (N). In the short run, an increase in only women’s wages in H would have a partial effect on consumption in the rest of the economy solely due to higher consumption out of women’s wage income. For the same amount of increase in , whether the impact on consumption in the rest of the economy is larger in the case of “new hiring in H” or the case of “closing the gender wage gap in H” depends on the marginal propensities to consume for women and men workers in H. If the marginal propensity to consume is larger for women workers in H, the impact of closing the gender wage gap in H will be stronger, and if the marginal propensity to consume is larger for men workers the effect through higher employment in H will be stronger.

For the same amount of increase in , the short run effect of closing the gender pay gap in H on households’ social expenditures is the same as in the case of new hiring in H, as for simplicity in our model we did not distinguish the marginal propensity to consume in the social sector out of women’s and men’s wages in H.

Similarly, closing the gender pay gap in H increases the share of public social expenditures in GDP, and thereby affects private investment, all other types of public spending as well in the short run.

The short-run impact of closing the gender pay gap in H on total output is summarized in and the detailed effects are derived in the Online Appendix 6.

In the next period, the impact of the closing gender pay gap in H on the components of aggregate demand is due to the effects on labor productivity. For a constant men’s wage rate, an increase in the women’s wage rate in H affects labor productivity due to an increase in public social expenditures. Hence, we expect effects similar to the case in which public social expenditures increase due to new hiring in H as shown in detail in the Online Appendix 6. The main difference arises because, for the same amount of change in the share of public social expenditures in GDP, the short-run effects of increasing women’s wages in H on output is different. This is because changes in output have both a direct and an indirect effect on labor productivity due to changes in unpaid labor, other public expenditures, and households’ social expenditures, as shown in .

The short-run effect of an increase in women’s wages in H on total employment is solely through its effect on total output. Higher women’s wages affect total output in N, which leads to changes in employment in N. Moreover, the changes in total output also affect public social expenditures through the multiplier effects which would further affect employment in H.

The effect of higher women’s wages in H on employment in the next period is determined by the relative magnitude of the effects on total output and labor productivity in the next period. These effects are further analyzed in the Online Appendix 6. If closing the gender pay gap in H leads to an increase in aggregate output high enough to offset the negative effects of a possible increase in labor productivity on labor demand, employment increases in the next period.

Finally, an increase in women’s wages in H has both a direct impact on public debt/GDP as public social expenditures increase as well as an indirect impact due to changes in aggregate output (Online Appendix 6).

In summary, the effects of closing the gender pay gap in the social sector will be similar to the case of hiring more people in the social sector with constant wage rates, except that the effects on output in the short run are solely due to the effects of higher women’s wages in the social sector (apart from the multiplier effects), and compared to the first case, we expect a lower effect on aggregate output and employment in the economy.

CONCLUSION AND POLICY IMPLICATIONS

This article develops a Post-Keynesian/Post-Kaleckian feminist model to theoretically analyze the effects of labor market and fiscal policies on growth and employment. We present a three-sector gendered macroeconomic model with physical and social sectors (health, social care, education, childcare) in the public and private market economy, and an unpaid domestic care sector. This theoretical model can form the basis for the empirical analysis of gender equality and fiscal policy on output and employment of men and women and serve as a tool for policy analysis and gender-responsive budgeting.

The policy implications of the model can be discussed in the context of the stylized facts of a developing economy with a significant unpaid reproductive economy, high gender pay and/or employment gaps, low women’s labor force participation rate, and high occupational segregation. In particular, we can analyze the impact of a policy mix of upward convergence via a simultaneous increase in both women’s and men’s wages with closing gender pay gaps (faster increase in women’s wages than men’s wages) and a rise in public spending in social versus physical investment, and discuss possible alternative outcomes based on alternative parameters of the model.

The effects of government spending in the other sectors or changes in the tax rates are further potential applications of the model. As the analytical solutions are symmetrical, we do not present them in the article.

Four important policy implications flow from our analysis. First, regarding fiscal policy, we expect public investment in social infrastructure to reduce women’s unpaid domestic care work, while increasing their labor supply and enabling them to spend more time in paid work. Aggregate demand is stimulated both in the short and the long run. Due to sectoral and occupational segregation, public spending in social infrastructure is expected to create more employment for women compared to physical infrastructure. In the long run, government spending and higher women’s income are expected to increase productivity, which may partially moderate the positive impact of fiscal spending on employment.

Second, if the short- and long-term multiplier and the productivity effects of public investment in social infrastructure are stronger than those of public investment in physical infrastructure, and given the labor-intensive and domestic demand-oriented nature of social infrastructure and occupational segregation, such investment is expected to lead to very strong increases in employment of women as well as creating substantial amount of jobs for men in all sectors of the economy due to spillover effects of demand from the social sector to the rest of the economy. This policy thereby also contributes to closing the gender gaps in employment. According to empirical research based on input–output tables (Antonopoulos and Kim Citation2008; Antonopoulos et al. Citation2010; İlkkaracan, Kim, and Kaya Citation2015; De Henau et al. Citation2016; İlkkaracan and Kim Citation2019), public investment in physical infrastructure creates fewer jobs, and most new jobs are jobs predominantly held by men; however, this research does not consider the long-term effects on productivity. An empirical analysis of our model can further shed light on the gendered policy implications. Similar differences in the impact of wages in different sectors follow. As H is more labor intensive than N, the impact of a wage increase in H on output is expected to be substantially higher.

Third, with respect to tax policies, if the economy is wage-led, increasing the progressivity of the tax regime via increasing taxes on capital and decreasing taxes on labor leads to a stronger positive impact on output. Conversely, if the economy is profit-led, increasing the progressivity of the tax system leads to further negative effects on output and employment.

Finally, policy mix scenarios can be analyzed by combining the impact of increasing public spending and wages. This latter is particularly important in the long run in a wage-led economy where employment may decrease in N despite an increase in output, if the output effects are small, but productivity effects are large. In this case fiscal spending can ensure equality-led growth is combined with employment expansion for both women and men.

In this paper, we modeled the impact of closing gender gaps only for the case of rising women’s wages with constant men’s wages. The impact of the case of an alternative scenario of closing gender gaps via an upward convergence can be derived from the model. The impact of increasing wages and/or upward convergence in both sectors can be derived by summing up the effects in both N and H.

One limitation of the model is that it focuses on the real economy and does not include the financial sector and is not useful to analyze monetary policy. However, we model the effect of interest rate on investment via the effects of public debt on the interest rate, although from a Keynesian perspective the effect of changes in the interest rate on investment is likely to be small.

Overall, the model can be utilized to empirically analyze a specific economy and develop an appropriate policy mix to achieve a gender-equitable development given the behavioral parameters of the components of aggregate demand and the structural features of the economy. The model is generalizable to low-income countries that lack physical or social infrastructure, or high-income countries, but depending on the level of economic development or gender relations, the relevant parameters and values of sectoral shares, occupational segregation, and pay gaps will differ; hence the effects of policies are an empirical question depending on these parameters and structural features.

To illustrate empirical application, Onaran, Oyvat, and Fotopoulou (Citation2019) and Cem Oyvat and Özlem Onaran (Citation2020) present an econometric estimation of the model for the UK and South Korea, respectively. They find positive effects of public social infrastructure on output and women’s and men’s employment not just in the short run but also in the long run, despite strong productivity effects, as the multiplier effects are relatively strong. As expected, women’s employment effects are much stronger. A policy combination of hiring more nursery teachers, care workers, nurses, and teachers and paying them higher wages in the public sector leads to both greater equality and higher employment for both women and men and higher productivity.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (688.6 KB)ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Elissa Braunstein, Robert Blecker, Ramaa Vasudevan, Ipek Ilkkaracan, Sue Himmelweit, Diane Elson, and Jerome De Henau for helpful comments on earlier versions of the research. This article received funding from the Care Work and the Economy initiative of the Program in Gender Analysis in Economics (PGAE) in the Department of Economics at American University. The usual disclaimers apply.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2022.2033294.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Özlem Onaran

Özlem Onaran is Professor of Economics at the University of Greenwich and the co-director of the Institute of Political Economy, Governance, Finance and Accountability. She is a member of the Scientific Committee of the Foundation of European Progressive Studies, the Scientific Advisory Board of the Hans Boeckler Foundation, the Policy Advisory Group of the Women’s Budget Group, and the Coordinating Committee of the Research Network Macroeconomics and Macroeconomic Policies. She has more than seventy articles in books and leading peer-reviewed journals on issues of inequality, wage-led growth, employment, fiscal policy, and gender.

Cem Oyvat

Cem Oyvat is Lecturer in Economics at the University of Greenwich. He received his PhD in Economics from University of Massachusetts – Amherst in 2014 with dissertation titled “Essays on the Evolution of Inequality.” His research interests include development economics, macroeconomics, international economics, income distribution, and political economy.

Eurydice Fotopoulou

Eurydice Fotopoulou is Lecturer at Goldsmiths, University of London. Eurydice’s research focuses on gender, macroeconomics, labor market, and fiscal policies. Her research is interdisciplinary, drawing from economics, sociology, and gender studies. Eurydice has a PhD in Economics by the University of Greenwich, an MSc in the Political Economy of Development, and a BSc in Development Economics from SOAS, University of London.

Notes

1 H refers to the sector producing “human capabilities” as defined by Braunstein, van Staveren, and Tavani (Citation2011). N refers to the rest of the economy producing goods and services outside this sector, or simply “non-human capabilities” sectors.

2 We preserved the term “consumption” for this category consistent with the definitions in national accounts.

3 Government’s social infrastructure expenditures are classified as current spending on labor services in the national accounts. The physical infrastructure associated with providing social infrastructure such as schools and hospitals are counted as physical infrastructure. Hence part of also contributes to social infrastructure. However, our classification is important for a gendered analysis of the employment impact of different fiscal policy decisions, as

dominated by women’s labor, while construction, just as most other parts of

, is dominated by men’s labor.

4 For simplicity, we assume that H only consists of the public social sector. The employment and supply in this sector are entirely financed by public social expenditures and funded by either taxation or borrowing, and the households do not pay for these in-kind publicly provided services. The households’ private social consumption (see Equation 21) is supplied by the private market output in the rest of economy (). Hence, private social consumption does not directly contribute to the generation of employment in H sector; however, they affect labor productivity in the next period positively as discussed below.

5 If we allow for the MPC of women and men working in H also to differ, the positive effects of gender equality or public social spending on output and productivity would be amplified, if women have a higher MPC in H as indicated by the micro-econometric evidence.

6 Output in H is simply equal to the wage bill in H, as there is no profit in H.

7 If there are satellite accounts for time use, the effect of unpaid labor on productivity can be empirically estimated.

REFERENCES

- Agenor, Pierre R. and Madina Agenor. 2014. “Infrastructure, Women’s Time Allocation, and Economic Development.” Journal of Economics 113: 1–30.

- Alarco, Germán. 2016. “Distribución factorial del ingreso y regímenes de crecimiento en América Latina, 1950–2012” [Factorial distribution of income and growth regimes in Latin America, 1950–2012]. Revista Internacional del Trabajo 135(1): 79–103.

- Antonopoulos, Rania and Kijong Kim. 2008. Scaling Up South Africa’s Expanded Public Works Programme: A Social Sector Intervention Proposal. New York: Levy Economics Institute.

- Antonopoulos, Rania, Kijong Kim, Thomas Masterson, and Ajit Zacharias. 2010. “Investing in Care: A Strategy for Effective and Equitable Job Creation.” Working Paper No. 610, Levy Economics Institute.

- Bhaduri, Amit and Stephen Marglin. 1990. “Unemployment and the Real Wage: The Economic Basis for Contesting Political Ideologies.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 14(4): 375–93.

- Blecker, Robert A. and Stephanie Seguino. 2002. “Macroeconomic Effects of Reducing Gender Wage Inequality in an Export-Oriented, Semi-Industrialized Economy.” Review of Development Economics 6(1): 103–19.

- Blumberg, Rae Lesser. 1991. “Income Under Female Versus Male Control: Hypotheses from a Theory of Gender Stratification and Data from the Third World.” Journal of Family Issues 9(1): 51–84.

- Braunstein, Elissa, Irene van Staveren, and Daniele Tavani. 2011. “Embedding Care and Unpaid Work in Macroeconomic Modelling: A Structuralist Approach.” Feminist Economics 17(4): 5–31.

- De Henau, Jerome, Susan Himmelweit, Zofia Łapniewska, and Diane Perrons. 2016. “Investing in the Care Economy: A Gender Analysis of Employment Stimulus in Seven OECD countries.” Report by the UK Women’s Budget Group for the International Trade Union Confederation, Brussels. https://wbg.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/De_Henau_Perrons_WBG_CareEconomy_ITUC_briefing_final.pdf.

- Doepke, Matthias and Michele Tertilt. 2016. “Families in Macroeconomics.” In Handbook of Macroeconomics, Volume 2, edited by J. B. Taylor and U. Harald, 1789–891. Amsterdam: North Holland.

- Elson, Diane. 2016. “Gender Budgeting and Macroeconomic Policy.” In Feminist Economics and Public Policy: Reflections on the Work and Impact of Ailsa Mckay, edited by Morag Gillespie, 25–35. Oxon: Taylor Francis Limited.

- Elson, Diane.. 2017. “A Gender-Equitable Macroeconomic Framework for Europe.” In Economics and Austerity in Europe: Gendered Impacts and Sustainable Alternatives, edited by Hannah Bargawi, Giovanni Cozzi, and Susan Himmelweit, 15–26. London: Routledge.

- Ertürk, Korkut and Nilüfer Çağatay. 1995. “Macroeconomic Consequences of Cyclical and Secular Changes in Feminization: An Experiment at Gendered Macromodelling.” World Development 23(11): 1969–77.

- Folbre, Nancy. 1995. “‘Holding Hands at Midnight’: The Paradox of Caring Labor.” Feminist Economics 1(1): 73–92.

- Folbre, Nancy and Julie Nelson. 2000. “For Love or Money – Or Both?” Journal of Economic Perspectives 14(4): 123–40.

- Fukui, Masao, Emi Nakamura, and Jón Steinsson. 2019. “Women, Wealth Effects, and Slow Recoveries.” NBER Working Paper No. 25311, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA.

- Hein, Eckhart and Artur Tarassow. 2010. “Distribution, Aggregate Demand and Productivity Growth: Theory and Empirical Results for Six OECD Countries Based on a Post-Kaleckian Model.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 34(4): 727–54.

- Hein, Eckhart and Lena Vogel. 2009. “Distribution and Growth in France and Germany: Single Equation Estimations and Model Simulations Based on the Bhaduri/Marglin Model.” Review of Political Economy 21(2): 245–72.

- İlkkaracan, İpek and Kijong Kim. 2019. The Employment Generation Impact of Meeting SDG Targets in Early Childhood Care, Education, Health and Long-Term Care in 45 Countries. Geneva: ILO.

- İlkkaracan, İpek, Kijong Kim, and Tolga Kaya. 2015. “The Impact of Public Investment in Social Care Services on Employment, Gender Equality, and Poverty: The Turkish Case.” Research Project Report, Istanbul Technical University Women’s Studies Center in Science, Engineering and Technology and the Levy Economics Institute, in partnership with ILO and UNDP Turkey, and the UNDP and UN Women Regional Offices for Europe and Central Asia.

- Jetin, Bruno and Ozan Ekin Kurt. 2016. “Functional Income Distribution and Growth in Thailand: A Post Keynesian Econometric Analysis.” Journal of Post Keynesian Economics 39(3): 334–60.

- Kabeer, Naila. 1997. “Women, Wages and Intra-Household Power Relations in Urban Bangladesh.” Development and Change 28(2): 261–302.

- Marx, Karl. 1867. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy: Volume 1 - The Production Process of Capital. New York: International Publishers.

- Molero-Simarro, Ricardo. 2015. “Functional Distribution of Income, Aggregate Demand, and Economic Growth in the Chinese Economy, 1978–2007.” International Review of Applied Economics 29(4): 435–54.

- Morrison, Andrew, Dhushyanth Raju, and Nistha Sinha. 2007. “Gender Equality, Poverty and Economic Growth.” Policy Research Working Paper 4349, World Bank.

- Naastepad, (Ro) C. W. M. 2006. “Technology, Demand and Distribution: A Cumulative Growth Model with an Application to the Dutch Productivity Growth Slowdown.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 30(3): 403–34.

- Obst, Thomas, Özlem Onaran, and Maria Nikolaidi. 2020. “A Post-Kaleckian Analysis of the Effect of Income Distribution, Public Spending and Taxes on Demand, Investment and Budget Balance: The Case of Europe.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 44(6): 1221–43.

- Onaran, Özlem. 2016. “The Role of Gender Equality in an Equality-Led Sustainable Development Strategy.” In Lives After Austerity: Gendered Impacts and Sustainable Alternatives for Europe, edited by Hannah Bargawi, Giovanni Cozzi, and Susan Himmelweit, 62–78. London: Routledge.

- Onaran, Özlem and Giorgos Galanis. 2014. “Income Distribution and Growth: A Global Model.” Environment and Planning A 46(10): 2489–513.

- Onaran, Özlem and Thomas Obst. 2016. “Wage-Led Growth in the EU15 Member-States: The Effects of Income Distribution on Growth, Investment, Trade Balance and Inflation.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 40(6): 1517–51.

- Onaran, Özlem, Cem Oyvat, and Eurydice Fotopoulou. 2019. “The Effects of Income, Gender and Wealth Inequality and Economic Policies on Macroeconomic Performance in the UK.” Greenwich Papers in Political Economy No. 71, University of Greenwich.

- Oyvat, Cem and Özlem Onaran. 2020. “The Effect of Gender Equality and Fiscal Policy on Growth and Employment: The Case of South Korea.” CWE-GAM Working Paper.

- Pahl, Jan. 2000. “The Gendering of Spending Within Households.” Radical Statistics 75: 38–48.

- Seguino, Stephanie. 2010. “Gender, Distribution, and Balance of Payments Constrained Growth in Developing Countries.” Review of Political Economy 22(3): 373–404.

- Seguino, Stephanie. 2012. “Macroeconomics, Human Development, and Distribution.” Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 13(1): 59–81.

- Seguino, Stephanie and Maria Floro. 2003. “Does Gender Have Any Effect on Aggregate Saving? An Empirical Analysis.” International Review of Applied Economics 17(2): 147–66.

- Shapiro, Carl and Joseph E. Stiglitz. 1984. “Equilibrium Unemployment as a Worker Discipline Device.” American Economic Review 74(3): 433–44.

- Stotsky, Janet G. 2006. “Gender and its Relevance to Macroeconomic Policy: A Survey.” IMF Working Paper WP/06/233, IMF.

- Women’s Budget Group UK and Scottish Women’s Budget Group (WBG). 2015. “Plan F. A Feminist Economic Strategy for a Caring and Sustainable Economy.” http://wbg.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/PLAN-F-2015.pdf.

- Yılmaz, Ensar. 2015. “Wage or Profit-Led Growth? The Case of Turkey.” Journal of Economic Issues 49(3): 814–34.

APPENDIX

THE EFFECTS OF A CHANGE IN THE SHARE OF PUBLIC SOCIAL INFRASTRUCTURE INVESTMENT IN GDP

The short-run effects

The short-run effects of higher share of public social expenditures are shown in Equation A1

(A1)

(A1)

where

(A2)

(A2)

The multiplier term for N is which is derived in Online Appendix 2.

The short run partial impact of public social expenditures () on consumption in N is below for a given level of output in N (

=

) prior to the multiplier effects.

(A3)

(A3)

The short run partial impact of public social expenditure () on consumption in H is

(A4)

(A4)

As discussed above, the sign for Equation A4 is ambiguous, but it is likely to be negative.

The partial effect of public social expenditures () on private investment is

(A5)

(A5)

where the partial impact on the profit share is zero for a constant output in N.

(A6)

(A6)

For a constant output in N, the impact of rising public debt/GDP on investment is likely to be negative () in the short run; however, the rise in public debt/GDP can be reduced due to rising tax revenues as well as increasing GDP (See Online Appendix 3).

The short-run partial impact of higher public social expenditure/GDP on exports and imports is zero, since the partial impact on the profit share is zero, as shown below:

(A7)

(A7)

(A8)

(A8)

Finally, the positive impact of higher public social expenditures on different types of government expenditures is shown below:

(A9)

(A9)

(A10)

(A10)

(A11)

(A11)

The next period

The long-run effect of a rising share of social expenditures in GDP on aggregate output is shown in Equation A12:

(A12)

(A12)

where

is the multiplier.

To derive the partial effect of on each component of GDP, we first exhibit its influence on labor productivity as the public social investments affect the profit share and employment in the next period through labor productivity in Equation A13.

(A13)

(A13)

Next, the partial impact of public social investment on consumption in N and H in the next period are respectively shown in Equations A14 and A15:

(A14)

(A14)

(A15)

(A15)

where

and

are respectively the partial effect of the share of public social expenditures in GDP on female and male employment in N in the next period. The partial impact of

on employment in N due to changes in labor productivity is shown in more detail in Online Appendix 3.

A16 demonstrates the share of public social expenditures effect on private investment.

(A16)

(A16)

where

is the partial effect of rising public social expenditures on public debt/GDP. The sign of

is ambiguous (See Online Appendix 4).

The sign of the effect on the profit share, , depends on the effect of higher public social expenditures on labor productivity as shown below; however, we expect it to be positive as

is more likely to be positive.

(A17)

(A17)

Finally, for a constant output in N, the partial effect of public social expenditures on exports and imports are expected to be positive and negative respectively as it is more likely that

and hence

.

(A18)

(A18)

(A19)

(A19)

The effects on employment and public debt, A20 and A21, show the effects of a higher share of public social expenditure in GDP on female and male employment, respectively, in the short run.

A higher share of public social expenditure in GDP affects total female employment due to increasing aggregate output and its direct impact on employment in the social sector:

(A20)

(A20)

(A21)

(A21)

Overall, the effect of increasing share of public social expenditures in GDP on employment is:

(A22)

(A22)

The effects of increasing public social expenditures on total female and male employment in the next period are respectively shown in Equations A23 and A24:

(A23)

(A23)

(A24)

(A24)

Last, the total effect of increasing public social expenditures on total employment in the long run is given in Equation A25.

(A25)

(A25)

Finally, the impact of rising public expenditures on public debt/Y in the short run and the next period are as below:

(A26)

(A26)

(A27)

(A27)