?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Introduction: Although delusions in Parkinson’s disease (PD) are rare, when they occur they frequently take the form of “Othello syndrome”: the irrational belief that a spouse or partner is being unfaithful. Hitherto dismissed as either a by-product of dopamine therapy or cognitive impairment, there are still no convincing theoretical accounts to explain why only some patients fall prey to this delusion, or why it persists despite clear disconfirmatory evidence.

Methods: We discuss the limitations of existing explanations of this delusion, namely hyperdopaminergia-induced anomalous perceptual experiences and cognitive impairment, before describing how Bayesian predictive processing accounts can provide a more comprehensive explanation by foregrounding the importance of prior experience and its impact upon computation of probability. We illustrate this new conceptualisation with three case vignettes.

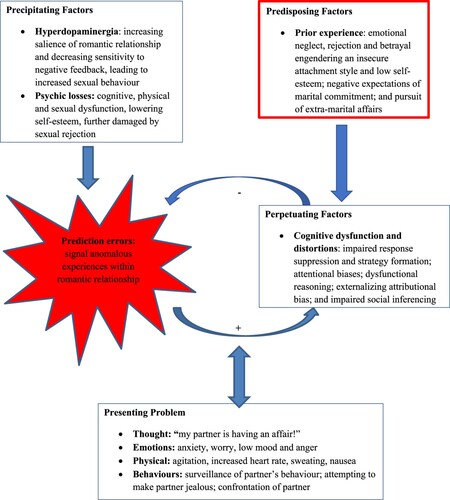

Results: We suggest that in those with prior experience of romantic betrayal, hyperdominergic-induced aberrant prediction errors enable anomalous perceptual experiences to accrue greater prominence, which is then maintained through Bayes-optimal inferencing to confirm cognitive distortions, eliciting and shaping this dangerous delusion.

Conclusions: We propose the first comprehensive mechanistic account of Othello syndrome in PD and discuss implications for clinical interventions.

Introduction

“ … trifles light as air

Are to the jealous, confirmations strong

As proofs of holy writ.”

Othello, 3.3, 323-5.

Othello syndrome

Although delusions in PD are rare, affecting only 1 of 100 consecutive patients (Holroyd et al., Citation2001), when present, they are usually paranoid in nature, frequently manifesting as delusional jealousy or “Othello syndrome” (Graff-Radford et al., Citation2012). First coined by Todd and Dewhurst in Citation1955, Othello syndrome is the preoccupation with the belief that a romantic partner is being unfaithful. Associated with high levels of distress and anxiety, it often results in violent and aggressive behaviour, usually directed towards the partner.

Theoretical accounts of Othello syndrome in PD

Side-effect of dopamine therapy

There have been few attempts to explain why Othello syndrome occurs in PD. Mostly, it has been described as a side-effect of dopamine therapy. Of the several case reports in PD (e.g., Graff-Radford et al., Citation2010), all describe its onset following the introduction of dopamine therapy, particularly dopamine agonists. All also report remission following reduction of dopamine therapy, albeit often with the addition of a neuroleptic, such as quetiapine or clozapine.

It is now well recognised that alongside the anticipated improvements in motor control, dopamine therapy can also lead to changes in behaviour. There is a greatly increased risk of impulse control disorder, with relatively high rates of hypersexuality, gambling, overspending and binge eating, as well as compulsive behaviours of hobbyism, punding and dopamine dysregulation (Weintraub & Mamikonyan, Citation2019). It is suggested that these behavioural symptoms reflect the uneven pattern of dopaminergic loss in the striatum and desensitisation of dopamine D2 autoreceptors, whereby dopamine therapy leads to an “overdose” of dopamine in the ventral striatum and connected limbic areas (Cools, Citation2006). As these areas are important in reward and reinforcement learning, particularly of natural rewards such as sex, hyperdopaminergia can result in increased salience of reward-related stimuli and intense reward-seeking (Berridge, Citation2007). Dopamine agonists may also interfere with learning by preventing decreases in dopaminergic transmission that occur with negative feedback (Pizzagalli et al., Citation2008), thereby allowing reward-seeking to persist. Thus, sex may become an overpowering and preoccupying activity, leading to more impulsive and appetitive sexual behaviour, which persists despite potential negative consequences, such as relationship strain. It is assumed that these relationship tensions, alongside increased and anomalous salience of sexual relationships, lead some to develop the erroneous belief that their partner is being unfaithful. Such a conclusion may be thought of as a normal response to abnormal perceptual experiences (Maher, Citation1974).

This account certainly provides a convincing framework for understanding how dopamine therapy comes to be the “wind of the psychotic fire” (Laruelle & Abi-Dargham, Citation1999). Yet, fails to explain why so few patients on dopamine therapy fall prey to these symptoms or why they can persist despite clear disconfirmatory evidence. This suggests that for Othello syndrome to occur other factors must also be involved.

By-product of cognitive impairment

Othello syndrome in PD has also been understood as a by-product of cognitive impairment. Cannas et al. (Citation2009) reported an incidence peak occurring in advanced PD, in the presence of severe cognitive deterioration. They suggest that cognitive impairment interacts with dopamine therapy to elicit the delusion. Cognitive impairment has been similarly implicated in the development and maintenance of other delusional beliefs. Coltheart and colleagues (Citation2010) argued that Capgras delusion, the belief that a close relative has been replaced by an impostor, is contingent upon not only anomalous experience of reduced autonomic responsivity to familiar faces, but also additional cognitive impairments that fail to suppress implausible responses to the perceptual deficit.

Although there are reports that PD Othello syndrome can occur in intact cognition, closer inspection reveals that this usually refers to preserved performance on the MMSE only (e.g., Cannas et al., Citation2009). As a brief screen of cognitive function, the MMSE is subject to a ceiling effect, and does not assess frontal attentional and executive functioning, giving it a low detection rate for PD cognitive impairment (Foley et al., Citation2022). Rather, we have shown that PD patients with Othello syndrome do demonstrate cognitive deficits, evident on tests of frontal attentional and executive functioning, particularly those that require response suppression and strategy formation (Foley et al., Citation2017). These deficits can occur in otherwise normal cognitive performance and likely reflect frontal lobe hypometabolism (Liepelt et al., Citation2009).

Non-PD Othello syndrome has also been associated with dysfunction of the frontal cortex, particularly the right frontal lobe (Graff-Radford et al., Citation2012). Similarly, delusions in general have been associated with underactivity in right frontal areas (Papageorgiou et al., Citation2004). Thus, the integrity of particularly the right frontal cortex, and its associated cognitive processes, may be an important determinant in the development and maintenance of delusional beliefs.

In addition to frank cognitive impairments, previous research has shown that specific cognitive distortions accompany the development and maintenance of delusional beliefs. These include: (1) attentional biases of selectively focusing on threat-related information, giving more weight to, and enhancing recall of confirmatory evidence (Bentall et al., Citation1995); (2) reasoning relying upon internal emotional states to drive data-gathering and jumping-to-conclusions (Garety et al., Citation1991); (3) attributional biases externalising blame (Bortolotti, Citation2015); and (4) poor social cognition (Phalen et al., Citation2017). When such distortions occur upon a backdrop of social isolation, with little exposure to disconfirmatory feedback, delusions seem most likely to ensue (Freeman, Citation2007).

Some of these cognitive distortions have already been documented in PD. Frontal attentional and executive dysfunction reduces attentional flexibility and leads to greater difficulty overcoming learned attentional biases (Fallon et al., Citation2016). There is distorted reasoning, with more jumping-to-conclusions, particularly in those with impulse control disorders (Djamshidian et al., Citation2012). There are also deficits in social inferencing (Foley et al., Citation2019). Thus, a high proportion of PD patients will demonstrate deficits in frontal attentional and executive function, as well as the cognitive distortions that accompany delusional beliefs, in addition to being treated with dopamine therapy. Despite this, only a small sample will develop Othello syndrome. This suggests that there must be yet another factor involved.

Bayesian predictive processing

Early formulations cast delusions as incomprehensible: “true delusions are distinguishable from ‘delusional-like ideas’ because they often occur suddenly and are ‘ununderstandable’ in the sense that they cannot be understood in terms of the individual’s background experiences and personality” (Jaspers, Citation1963). More recent research has in fact shown delusions in general to be preceded by severe disruptions of early attachment relationships (MacBeth et al., Citation2008), with delusional content furnished by personal context. For example, religious delusions can reflect an intermingling of religious background and guilt (Drinnan & Lavender, Citation2006) and Capgras can occur upon a backdrop of long-standing conflicted feelings about the “impostor” (McKay et al., Citation2005).

Previously, we noted the striking finding that all five of our PD Othello patients had suffered early in life from infidelities and jealousy (Foley et al., Citation2017). This mirrors similar findings in non-neurological populations, in which Othello syndrome patients have described previous experience of infidelity in the behaviour of their partner, themselves, and/or their parent(s) (Todd & Dewhurst, Citation1955). Previous experience of betrayal within early and important relationships may engender negative expectations of marital commitment, and shape anxious and insecure attachment styles in subsequent romantic relationships (Owen et al., Citation2012). Certainly, in non-neurological populations, those with insecure attachment styles demonstrate greater relationship jealousy and perceive rivals as more threatening than those with secure attachment styles (Marazziti et al., Citation2010). Therefore, in contrast to Jaspers’ conceptualisation, background experiences and personality appear to be of great importance when seeking to understand the development of delusions. In PD Othello syndrome, we suggest that when faced with dopamine-induced increased and anomalous salience of sexual relationships, prior experience of betrayal is drawn upon to make sense of this experience, thereby opening the door to the delusional belief (Kapur, Citation2003). But in order to understand how and why this belief can then persist, we now turn to predictive processing and Bayes-optimal inferencing theories.

Predictive processing accounts have been combined with Bayesian theory to offer a hierarchical system of belief updating, which adapts von Helmholtz’s (Citation1971) theories of perception as unconscious inference. At a neural level, the brain is thought to make predictions about the world. When there is a mismatch between what is expected and what is experienced, a prediction error occurs. In order to optimise its model of the world, the brain seeks to minimise such prediction errors; if prediction errors are sufficiently reliable, the expectation is updated. However, if the expectation is sufficiently reliable, prediction error is ignored (Friston, Citation2009). Importantly, the weighting of prediction errors, particularly of rewards, is regulated by various neuromodulatory systems, including dopamine (Pessiglione et al., Citation2006). Bayesian theory can then be used to apply this at a behavioural level (Knill & Pouget, Citation2004). Bayes’s theorem states:

in which the probability p of a hypothesis h given the evidence e is proportional to its likelihood p (e/h) weighted by its prior probability p(h). Thus, this hierarchical system of belief updating again emphasises the role of prior experience (or predictions) in the shaping of expectations.

This theory has been used to understand the development of delusional beliefs in both psychiatric and organic disorders. It is suggested that when neuromodulatory systems are disrupted, by hyperdopaminergia for example, prediction errors can become abnormally strong, disturbing the weighting of likelihood and prior probability estimates. This can result in the abandonment of top-down predictions and adoption of seemingly implausible beliefs. Furthermore, the dominating effect of this updated belief, alongside undervalued and unchallenging current evidence, results in a Bayes-optimal “rational bias” (Fennell & Baddeley, Citation2012). This limits any further belief updating, but rather enables erroneous beliefs to become fixed delusions. This belief is then protected further by reduced generation of alternative explanations (Gershman, Citation2019) and overfitting of the explanation to accommodate and explain away any contradictory sensory data (Erdmann & Mathys, Citation2022). Moreover, experience is further shaped by the updated belief; through subsequent reality-testing and distortion of incoming sensory data, through attentional, reasoning and attributional biases. Biased sensory data strengthen the new belief and gradually untether the individual from reality, allowing them to spiral into a fixed delusional belief. Thus, Bayes-optimal inferencing can be used to understand how delusions become entrenched and apparently impervious to contradiction (Corlett, Citation2015).

This interconnection between experience and expectation is supported by basic neuroscience, with evidence of higher-level expectation sculpting lower-level sensory experience (e.g., Kok et al., Citation2012).

Neural circuitry underlying this iterative learning process is thought to involve the striatum and prefrontal cortex. Increased striatal dopamine activity has been associated with greater severity of psychotic symptoms and reductions in prefrontal cortex function (Howes et al., Citation2009).

Furthermore, the association between faulty predictive processing and delusional beliefs has been demonstrated in a number of studies with patient and healthy populations. Poorer monitoring of sensory predictions has been evidenced in patients with schizophrenia and delusions and hallucinations than in those without and/or healthy controls (Blakemore et al., Citation2000; Shergill et al., Citation2005), and imprecision in internal predictions is correlated with severity of delusions (Synofzik et al., Citation2010). Dysfunctional predictive processing is found in those more vulnerable to psychosis, as evidenced by slower electro-cortical habituation to sensory stimuli (Vernon et al., Citation2005) and attenuated right prefrontal cortex responses to violation of learned expectancies (Corlett et al., Citation2007). Aberrant predictive processing has also been associated with ketamine-induced delusional beliefs in healthy individuals (Corlett et al., Citation2006), and experimental manipulations of prediction errors can elicit false beliefs in healthy individuals (e.g., Brown et al., Citation2013).

We now propose extending this theory to offer an explanation for the development of PD Othello syndrome. We propose that prior experience of betrayal results in increased vigilance to anomalous experiences pertaining to romantic relationships, so that fewer dopamine-induced prediction errors are required before the expectation is updated to the erroneous belief that “my partner must be having an affair”. Moreover, the intense negative affect associated with previous betrayal likely balloons its probability as a causal explanation. The inherent unprovability of fidelity provides the necessary ambiguous sense data to allow this explanation to take hold and dominate, altering subsequent estimations of probability. This, alongside cognitive distortions and dysfunction, limits further belief updating and maintains the seemingly bizarre belief.

The mediating role of self-esteem and negative emotions

The legacy of prior betrayal can also include low self-esteem and feelings of inadequacy (Buunk, Citation1995). Previous studies have reported self-esteem to be an important mediating factor in the expression of jealousy, with jealousy representing a response to threatened loss of psychic resources (Ellis & Weinstein, Citation1986).

In PD, there are a number of psychological losses, affecting physical, cognitive, occupational, social and sexual domains, likely reducing self-esteem further. In addition, many undergo changes to self-perception because of stigmatising beliefs and experiences (Salazar et al., Citation2019). Accumulation of such losses and negative self-perceptions may trigger negative schemata of self and others, increasing vulnerability to low mood, anxiety and psychosis (Smith et al., Citation2006).

Othello syndrome is often contextualised by low mood and anxiety (Marazziti et al., Citation2013). Jealousy has been linked to anxious worrying, with some even describing jealousy as a form of worry (Leahy & Tirch, Citation2008). Worry has previously been associated with persecutory delusions (Startup et al., Citation2016) and is implicated in the manifestation of Othello syndrome in PD (Todd et al., Citation2010).

Furthermore, a common precipitating factor for Othello syndrome is sexual refusal (Freeman, Citation1990), often occurring when there is a sudden disparity in desire for sex. This disparity may be caused by a number of reasons, including increased frequency of sexual demands following dopamine therapy. Repeated sexual refusal may be experienced as rejection, reducing self-esteem even further.

Threatened with a catastrophic loss of self-esteem, formation of certain delusions may be considered adaptive (Lancellotta & Bortolotti, Citation2019), externalising the cause of the distress. By functioning as a “doxastic shear pin” (McKay & Dennett, Citation2009), they may provide a more acceptable form of reality and allow the individual to continue to function, albeit at a diminished level.

Here, we can consider Butler’s (Citation2000) description of “reverse-Othello syndrome”. Following severe right-sided brain injury and subsequent physical and cognitive disability, the patient’s romantic relationship broke down. A year after the injury, he remained an inpatient and confined to a wheelchair. Despite this, he developed delusional beliefs that he had married his ex-partner, whom he believed had remained faithful to him. The delusion served as a means of directing attention away from the tragic reality and was more compatible with his unfulfilled wishes.

Summary

We suggest that early experience of betrayal can result in insecure attachment and fragile expectations of fidelity, predisposing individuals to low self-esteem, low mood and anxiety. Faced with the cataract of losses in PD, and repeated sexual rejection, a total loss of self-esteem is threatened. When hyperdopaminergia-induced frontostriatal aberrant prediction errors signal anomalous experiences within a romantic relationship, prior experiences of betrayal are used to update expectations, resulting in the new, distressing belief that a romantic partner is being unfaithful. This updated expectation then shapes experience through a Bayes-optimal rational bias, and cognitive distortions exacerbated by impairments in response suppression and social inferencing. Biased and distorted sensory data then strengthen the new belief and gradually untether the individual from reality, allowing them to spiral into a fixed delusional belief. By identifying infidelity as the reason for their sexual rejection, self-esteem may be sheltered from further losses. We can now understand how “to the jealous” mere “trifles” can become “confirmations strong as proofs of holy writ”. This predictive processing account of PD Othello syndrome is depicted in .

Now, we illustrate this formulation of PD Othello syndrome, with vignettes of three patients who confirmed consent to publish.

Case vignette 1

The first patient was first described by Foley et al. (Citation2017). This patient was diagnosed with PD at the age of 51 years. A month after starting ropinirole, he developed hypersexuality. He also had hallucinations, reporting patterns on the walls that looked like animals, and became delusional, suspecting his wife as having sex with other men, including their son. He became convinced that she had hired a private detective and had installed microphones at home. He drilled holes in walls and took up floorboards searching for these. Subsequently, ropinirole was reduced, but psychotic symptoms remained until stopped completely. Neuropsychological assessment revealed a deficit in frontal executive functioning, with impaired performance on the Stroop and phonemic fluency. He also endorsed moderate anxiety and depression.

Four years later, he developed psychotic symptoms again. He was having visual hallucinations, seeing shapes and numbers on the ceiling, and auditory hallucinations, feeling like he was “in a movie”. He was convinced that his wife was having sex with their son, and his son was sneaking girls in for sex. Amantadine was stopped and quetiapine commenced. The intensity of psychotic symptoms lessened, but motor symptoms worsened. He was then switched to clozapine. Physical symptoms deteriorated further, but with a greater reduction in hallucinations and delusions. Repeat neuropsychological assessment revealed further cognitive decline, with greater deficits in frontal executive function (Stroop, phonemic fluency), and now impaired performance on measures of visual perception (Object Decision subtest from the Visual Object Space Perception battery) and semantic fluency, suggestive of an evolving PD dementia. He also described low mood and apathy. He stated that he is less concerned about his wife’s behaviour and described the experience as “like a bad dream”.

When discussing his early life and relationships, a notable theme of a lack of emotional intimacy emerged; he was not particularly close to anyone, even his family. His first important romantic relationship was ended by his girlfriend, who had found another partner. He found this very upsetting, and developed a tendency towards low mood from around this time. He described his relationship with his wife as involving not only a lack of emotional intimacy, but also a lack of physical intimacy, owing to a long-standing disparity in their desire for sex. He stated that his desire for sex was always greater than his wife’s, but that her desire reduced further after the birth of their first child: his son. After this, he sought sexual contact outside of their marriage, which was never explicitly disclosed to his wife. When describing his current family situation, he noted that his wife gets on well with their son, but he feels ridiculed by his children.

He described diagnosis with PD as a life-changing event. Around this time, he also experienced the onset of erectile dysfunction. Following commencement on ropinirole, his level of sexual interest increased, but his wife refused his sexual advances. He stated that this was very difficult, and reminded him of being rejected by his first girlfriend. He then found himself becoming suspicious about his wife, believing that if she was not having sex with him, she must be having sex with others, including their son.

Case vignette 2

The second patient was diagnosed with PD at the age of 38 years. He was commenced on co-beneldopa, which was gradually increased. One year after diagnosis, he developed hypersexuality. He also joined a casino, and bought a car and laptop on a whim. After a few years, he started believing his wife was having an affair with a work colleague. He began repeatedly telephoning her during working hours and questioning where she was and who she was with. As they worked together, this led to arguments both at home and in the workplace, and eventually him losing his job. Neuropsychological assessment revealed a relative deficit in frontal executive functioning, with impaired performance on the Hayling Sentence Completion Test. He also endorsed severe anxiety and moderate depression. In order to reduce dopamine therapy, he underwent deep brain stimulation, with resolution of the Othello syndrome.

Further enquiry revealed difficult early life experiences and relationships. He described physical and emotional abuse: he was told that he was “a mistake” by his father and that he was adopted by his siblings. His father drank heavily and his mother was an avid gambler, and the patient witnessed physical violence between them. His mother was later diagnosed with PD.

He was bullied at school and performed poorly in exams. In his teens, he shaved his head for a bet, but his hair never grew back, negatively affecting his self-esteem. He developed a tendency to low mood and alcohol misuse. At work, he adopted a confident persona. He described his attitude as “narcissistic” and “sociopathic”, admitting that he would “step over anyone to get what (he) wanted”, and sold customers worthless merchandise in order to advance his career. He acknowledged that this was an attempt to seek the approval of his parents and siblings. Yet even after exceeding all of their expectations, he never felt he received anything but criticism. Following his mother’s death, he described being rejected by the family and excluded from the will for not visiting her before her death. He explained that he could not face seeing how her PD had deteriorated. Two years later, his father died and he was not invited to the funeral.

When asked about romantic relationships, there were notable examples of infidelity. Twenty years previously, he caught his now-wife kissing someone else. Four years ago, he had an extra-marital affair, which he feels his wife has still not forgiven. After his PD diagnosis, his sexual advances towards his wife were spurned. He eventually gave up trying to have sex with her “out of embarrassment” and flirted with others in order to “shame a reaction out of her”.

Case vignette 3

The third patient was diagnosed with PD at the age of 58 years. Soon after treatment with ropinirole, he developed hypersexuality and jealousy. He also experienced visual illusions and extracampine passage phenomena. Neuropsychological assessment revealed a deficit in frontal executive functioning, with impaired performance on the Hayling Sentence Completion Test. He also endorsed mild anxiety. Ropinirole was lowered, which reduced his delusional jealousy, and he was referred for psychological therapy.

He explained that after commencing ropinirole, his libido had become disproportionately excessive compared to his partner’s and his sexual advances frequently rejected. He stated that although this had created some suspicions, the critical moment came when his wife called him by the name of an old boyfriend. This echoed an earlier event from his childhood, when his father’s infidelity was discovered by his mother in exactly the same way: calling her by the name of another. The patient was present when this happened and witnessed the ensuing argument.

The patient stated that after his wife’s slip, he sought confirmatory evidence for her infidelity. He vacillated between suspecting his wife and telling himself that it must be the medication making him think this way; he searched her belongings, but then felt “wretched and dishonest” for doing so. This behaviour was out of character for him, but he justified his behaviour by blaming his wife and dismissing her explanations.

He also had a history of infidelity. His first marriage broke down, at least in part, by his own infidelity. He explained that, in order to maintain his extra-marital affair, he had had to combine truth with deceit. Therefore, when his current partner gave reasonable reasons for having to work late, he would discount these and come to the erroneous conclusion that she must be having an affair with someone at work.

When asked about early life experiences and relationships, he described his father as absent both as a father and husband. It was in his early teens that his father’s affair was discovered and his parent’s marriage broke down. His father left the family home at this time.

Discussion

These case vignettes illustrate the interaction of factors, which we suggest combine to elicit and maintain PD Othello syndrome. First, we note the role of hyperdopaminergia: all three cases developed Othello syndrome soon after starting dopaminergic treatment. All three reported reductions in jealousy following its discontinuation or reduction. We note, however, that after discontinuation of the medication, Case 1 is “less concerned”. This hints that the belief has not disappeared, but retreated to a more manageable level.

Second, we note the cognitive factors. All three demonstrated a deficit in frontal executive functions, with impaired performance on the Stroop or Hayling Sentence Completion tests of response suppression. Further, we witness cognitive distortions of: seeking confirmatory evidence and dismissing inconsistent evidence; using internal states rather than logic when jumping to conclusions; and externalising blame for their sexual rejection. Although we did not assess social cognition formally, we note that all three committed social transgressions; Case 1 accused his wife of an incestuous relationship with their son, Case 2 harassed his wife at their workplace and Case 3 searched his wife’s belongings for evidence.

Last, we witness the dominating role of prior experience. All three reported previous relationship breakdown because of infidelity, all had been unfaithful themselves and one had witnessed the devastating effects of infidelity in his parents. All three also reported adverse early attachment experiences and a paucity of emotional intimacy. These experiences appear to be associated with low self-esteem, negative emotions, and maladaptive and defensive coping strategies, including pursuit of extra-marital affairs (Cases 1 and 2), excessive alcohol intake (Case 2), narcissistic behaviour (Case 2) and/or overworking (Case 2). All also described the pivotal role of sexual refusal. Although these were in the context of increased sexual demand, our patients experienced them as rejection, reactivating prior experiences.

Clinical implications

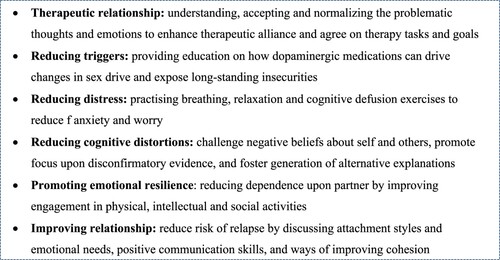

Treatment for Othello syndrome in PD is reduction of dopamine therapy. However, this may not be possible because of inadequate motor control and/or the delusional belief may not rescind. In these cases, neuroleptics, such as quetiapine or clozapine, may be used. In addition, the cognitive and emotional factors identified here suggest that psychological therapy may also be useful. We now consider how psychological approaches for managing delusions in general may be adapted for PD Othello syndrome, as summarised in .

Psychological therapies for delusions emphasise the importance of establishing a therapeutic working alliance (Dunn et al., Citation2006) before challenging beliefs. By gently enquiring about the patient’s recent concerns, the therapist can demonstrate willingness to engage in open discussion, and show that they recognise and understand their concerns.

It will be important to discuss the role of dopaminergic medications and early experiences. Rarely are patients given explanations of why jealousy has manifested. Although many will have been warned about hypersexuality, few will have been warned about Othello syndrome. By explaining that it is a recognised and treatable side-effect of dopamine therapy, and more common in people with early experience of betrayal, the patient may begin to consider alternative explanations for their concerns.

Improving management of threat-related distress will be important, particularly for those who have been rendered more parkinsonian by medication reduction or have been formally admitted, suffering even greater psychic losses. Cognitive defusion exercises from acceptance and commitment therapy have proven useful in delusions (Pankey & Hayes, Citation2003). These focus on distancing the patient from distressing thoughts, allowing them to reflect upon them as relational processes situated both historically and contextually.

It will also be important to improve management of anxiety and worry in general. Cognitive behavioural therapy strategies that focus on the processes involved in maintaining preoccupation and distress related to the delusion, rather than challenging its content, have been found useful (Freeman et al., Citation2015). These include increasing awareness of triggers of worry; designated worry time; planning activity at times of worry; and learning to let go of worry.

It may then be possible to challenge the cognitive distortions underpinning the delusional beliefs. By helping the patient to critically evaluate their beliefs and develop an alternative model of experience, the strength of confirmatory sensory data may gradually diminish, allowing the dominance of prior beliefs to subside. For PD Othello patients, this may involve examining important antecedents, such as the role of prior experiences, as well as highlighting perpetuating cognitive distortions. Metacognitive techniques that test the reality of the delusion and raise awareness of cognitive biases have been useful (Andreou et al., Citation2017).

Existing psychological therapies also focus upon relapse prevention. In PD Othello syndrome, this might involve bolstering self-esteem. This may be achieved by examining and challenging underlying negative beliefs about themselves and others (Turkington & Siddle, Citation1998), and helping them improve engagement in rewarding activities. Of course, the delusion has often vitiated the relationship and this is more likely in those with more fragile attachments to start with. Therefore, it may also be useful to examine the systemic factors that have contributed to and maintained the delusion. By working with both patient and partner, it may be useful to enhance communication skills, in order to help strengthen their relationship. This may be particularly important where there may have been considerable role changes, which may change further with increasing disability.

Conclusion

We have drawn upon three vignettes to propose a Bayesian predictive processing account of PD Othello syndrome. We have illustrated the different factors that we suggest are important in the development and maintenance of this delusion, and suggested therapeutic strategies to aid its dissolution.

Of course, it is important to note that we have drawn upon three cases only. This reflects the relative rarity of this delusion. However, its effects can be grave and therefore it is important to recognise its precipitating factors to improve provision of timely interventions and reduce costly unplanned admissions. Moreover, the factors highlighted in our three cases are consistent with those identified in earlier reports with neurological and non-neurological populations. Empirical testing of the proposed treatment strategies in this study is now required.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author [JAF]. The data are not publicly available because of privacy restrictions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aarsland, D., Larsen, J. P., Cummings, J. L., & Laake, K. (1999). Prevalence and clinical correlates of psychotic symptoms in Parkinson disease: A community-based study. Archives of Neurology, 56(5), 595–601. https://doi.org/10.1001/archneur.56.5.595

- Andreou, C., Wittekind, C. E., Fieker, M., Heitz, U., Veckenstedt, R., Bohn, F., & Moritz, S. (2017). Individualized metacognitive therapy for delusions: A randomized controlled rater-blind study. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 56, 144–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2016.11.013

- Bentall, R. P., Kaney, S., & Bowen-Jones, K. (1995). Persecutory delusions and recall of threat-related, depression-related, and neutral words. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 19(4), 445–457. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02230411

- Berridge, K. C. (2007). The debate over dopamine’s role in reward: The case for incentive salience. Psychopharmacology, 191(3), 391–431. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-006-0578-x

- Blakemore, S. J., Smith, J., Steel, R., Johnstone, E. C., & Frith, C. D. (2000). The perception of self-produced sensory stimuli in patients with auditory hallucinations and passivity experiences: Evidence for a breakdown in self-monitoring. Psychological Medicine, 30(5), 1131–1139. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291799002676

- Bortolotti, L. (2015). The epistemic innocence of motivated delusions. Consciousness and Cognition, 33, 490–499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2014.10.005

- Brown, H., Adams, R. A., Parees, I., Edwards, M., & Friston, K. (2013). Active inference, sensory attenuation and illusions. Cognitive Processing, 14(4), 411–427. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10339-013-0571-3

- Butler, P. V. (2000). Reverse othello syndrome subsequent to traumatic brain injury. Psychiatry, 63(1), 85–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/00332747.2000.11024897

- Buunk, B. P. (1995). Sex, self-esteem, dependency and extradyadic sexual experience as related to jealousy responses. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 12(1), 147–153. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407595121011

- Cannas, A., Solla, P., Floris, G., Tacconi, P., Marrosu, F., & Marrosu, M. G. (2009). Othello syndrome in Parkinson disease patients without dementia. The Neurologist, 15(1), 34–36. https://doi.org/10.1097/NRL.0b013e3181883dd4

- Coltheart, M. (2010). The neuropsychology of delusions. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1191(1), 16–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05496.x

- Cools, R. (2006). Dopaminergic modulation of cognitive function-implications for L-DOPA treatment in Parkinson's disease. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 30(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.03.024

- Corlett, P. R. (2015). Answering some phenomenal challenges to the prediction error model of delusions. World Psychiatry, 14(2), 181–183. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20211

- Corlett, P. R., Honey, G. D., Aitken, M. R., Dickinson, A., Shanks, D. R., Absalom, A. R., Lee, M., Pomarol-Clotet, E., Murray, G. K., McKenna, P. J., & Robbins, T. W. (2006). Frontal responses during learning predict vulnerability to the psychotogenic effects of ketamine: Linking cognition, brain activity, and psychosis. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63(6), 611–621. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.63.6.611

- Corlett, P. R., Murray, G. K., Honey, G. D., Aitken, M. R., Shanks, D. R., Robbins, T. W., Bullmore, E. T., Dickinson, A., & Fletcher, P. C. (2007). Disrupted prediction-error signal in psychosis: Evidence for an associative account of delusions. Brain, 130(9), 2387–2400. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awm173

- Diederich, N. J., Fénelon, G., Stebbins, G., & Goetz, C. G. (2009). Hallucinations in Parkinson disease. Nature Reviews Neurology, 5(6), 331–342. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2009.62

- Djamshidian, A., O'Sullivan, S. S., Sanotsky, Y., Sharman, S., Matviyenko, Y., Foltynie, T., Michalczuk, R., Aviles-Olmos, I., Fedoryshyn, L., Doherty, K. M., & Filts, Y. (2012). Decision making, impulsivity, and addictions: Do Parkinson's disease patients jump to conclusions? Movement Disorders, 27(9), 1137–1145. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.25105

- Drinnan, A., & Lavender, T. (2006). Deconstructing delusions: A qualitative study examining the relationship between religious beliefs and religious delusions. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 9(4), 317–331. https://doi.org/10.1080/13694670500071711

- Dunn, H., Morrison, A. P., & Bentall, R. P. (2006). The relationship between patient suitability, therapeutic alliance, homework compliance and outcome in cognitive therapy for psychosis. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy: An International Journal of Theory & Practice, 13(3), 145–152. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.481

- Ellis, C., & Weinstein, E. (1986). Jealousy and the social psychology of emotional experience. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 3(3), 337–357. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407586033006

- Erdmann, T., & Mathys, C. (2022). A generative framework for the study of delusions. Schizophrenia Research, 245, 42–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2020.11.048

- Fallon, S. J., Hampshire, A., Barker, R. A., & Owen, A. M. (2016). Learning to be inflexible: Enhanced attentional biases in Parkinson's disease. Cortex, 82, 24–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2016.05.005

- Fennell, J., & Baddeley, R. (2012). Uncertainty plus prior equals rational bias: An intuitive Bayesian probability weighting function. Psychological Review, 119(4), 878–887. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029346

- Foley, J. A., Dore, C., & Cipolotti, L. (2022). Correspondence between MMSE and detailed neuropsychological testing in Parkinson’s disease. The Neuropsychologist, 1(13), 9–14. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpsneur.2022.1.13.9

- Foley, J. A., Lancaster, C., Poznyak, E., Borejko, O., Niven, E., Foltynie, T., Abrahams, S., & Cipolotti, L. (2019). Impairment in theory of mind in Parkinson’s disease is explained by deficits in inhibition. Parkinson’s Disease, 2019, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/5480913

- Foley, J., Warner, T. T., & Cipolotti, L. (2017). The neuropsychological profile of Othello syndrome in Parkinson's disease. Cortex, 96, 158–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2017.08.009

- Freeman, D. (2007). Suspicious minds: The psychology of persecutory delusions. Clinical Psychology Review, 27(4), 425–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2006.10.004

- Freeman, D., Dunn, G., Startup, H., Pugh, K., Cordwell, J., Mander, H., Černis, E., Wingham, G., Shirvell, K., & Kingdon, D. (2015). Effects of cognitive behaviour therapy for worry on persecutory delusions in patients with psychosis (WIT): a parallel, single-blind, randomised controlled trial with a mediation analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 2(4), 305–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00039-5

- Freeman, T. (1990). Psychoanalytical aspects of morbid jealousy in women. British Journal of Psychiatry, 156(1), 68–72. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.156.1.68

- Friston, K. (2009). The free-energy principle: A rough guide to the brain? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 13(7), 293–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2009.04.005

- Garety, P. A., Hemsley, D. R., & Wessely, S. (1991). Reasoning in deluded schizophrenic and paranoid patients. Biases in performance on a probabilistic inference task. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 179(4), 194–201. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005053-199104000-00003

- Gershman, S. J. (2019). How to never be wrong. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 26(1), 13–28. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-018-1488-8

- Graff-Radford, J., Ahlskog, J. E., Bower, J. H., & Josephs, K. A. (2010). Dopamine agonists and Othello’s syndrome. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders, 16(10), 680–682. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parkreldis.2010.08.007

- Graff-Radford, J., Whitwell, J. L., Geda, Y. E., & Josephs, K. A. (2012). Clinical and imaging features of Othello’s syndrome. European Journal of Neurology, 19(1), 38–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-1331.2011.03412.x

- Holroyd, S., Currie, L., & Wooten, G. F. (2001). Prospective study of hallucinations and delusions in Parkinson's disease. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 70(6), 734–738. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.70.6.734

- Howes, O. D., Montgomery, A. J., Asselin, M. C., Murray, R. M., Valli, I., Tabraham, P., Bramon-Bosch, E., Valmaggia, L., Johns, L., Broome, M., & McGuire, P. K. (2009). Elevated striatal dopamine function linked to prodromal signs of schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry, 66(1), 13–20. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.514

- Jaspers, K. (1963). General psychopathology (J. Hoenig & M. W. Hamilton, Trans.). Manchester University Press.

- Kapur, S. (2003). Psychosis as a state of aberrant salience: A framework linking biology, phenomenology, and pharmacology in schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160(1), 13–23. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.160.1.13

- Knill, D. C., & Pouget, A. (2004). The Bayesian brain: The role of uncertainty in neural coding and computation. Trends in Neurosciences, 27(12), 712–719. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2004.10.007

- Kok, P., Jehee, J. F., & De Lange, F. P. (2012). Less is more: Expectation sharpens representations in the primary visual cortex. Neuron, 75(2), 265–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2012.04.034

- Lancellotta, E., & Bortolotti, L. (2019). Are clinical delusions adaptive? Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews. Cognitive Science, 10(5), e1502. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcs.1502

- Laruelle, M., & Abi-Dargham, A. (1999). Dopamine as the wind of the psychotic fire: New evidence from brain imaging studies. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 13(4), 358–371. https://doi.org/10.1177/026988119901300405

- Leahy, R. L., & Tirch, D. D. (2008). Cognitive behavioral therapy for jealousy. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 1(1), 18–32. https://doi.org/10.1521/ijct.2008.1.1.18

- Liepelt, I., Reimold, M., Maetzler, W., Godau, J., Reischl, G., Gaenslen, A., Herbst, H., & Berg, D. (2009). Cortical hypometabolism assessed by a metabolic ratio in Parkinson's disease primarily reflects cognitive deterioration—[18F] FDG-PET. Movement Disorders, 24(10), 1504–1511. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.22662

- MacBeth, A., Schwannauer, M., & Gumley, A. (2008). The association between attachment style, social mentalities, and paranoid ideation: An analogue study. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 81(1), 79–93. https://doi.org/10.1348/147608307X246156

- Maher, B. A. (1974). Delusional thinking and perceptual disorder. Journal of Individual Psychology, 30, 98–113.

- Marazziti, D., Consoli, G., Albanese, F., Laquidara, E., Baroni, S., & Catena Dell'osso, M. (2010). Romantic attachment and subtypes/dimensions of jealousy. Clinical Practice & Epidemiology in Mental Health, 6(1), 53–58. https://doi.org/10.2174/1745017901006010053

- Marazziti, D., Poletti, M., Dell'Osso, L., Baroni, S., & Bonuccelli, U. (2013). Prefrontal cortex, dopamine, and jealousy endophenotype. CNS Spectrums, 18(1), 6–14. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1092852912000740

- McKay, R., Langdon, R., & Coltheart, M. (2005). “Sleights of mind”: delusions, defences, and self-deception. Cognitive Neuropsychiatry, 10(4), 305–326. https://doi.org/10.1080/13546800444000074

- McKay, R. T., & Dennett, D. C. (2009). The evolution of misbelief. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 32(6), 493–510. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X09990975

- Owen, J., Quirk, K., & Manthos, M. (2012). I get no respect: The relationship between betrayal trauma and romantic relationship functioning. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 13(2), 175–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2012.642760

- Pankey, J., & Hayes, S. C. (2003). Acceptance and commitment therapy for psychosis. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy, 3, 311–328.

- Papageorgiou, C. C., Alevizos, B., Ventouras, E., Kontopantelis, E., Uzunoglu, N., & Christodoulou, G. (2004). Psychophysiological correlates of patients with delusional misidentification syndromes and psychotic major depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 81(2), 147–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-0327(03)00136-8

- Pessiglione, M., Seymour, B., Flandin, G., Dolan, R. J., & Frith, C. D. (2006). Dopamine-dependent prediction errors underpin reward-seeking behaviour in humans. Nature, 442(7106), 1042–1045. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature05051

- Phalen, P. L., Dimaggio, G., Popolo, R., & Lysaker, P. H. (2017). Aspects of Theory of Mind that attenuate the relationship between persecutory delusions and social functioning in schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 56, 65–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2016.07.008

- Pizzagalli, D. A., Evins, A. E., Schetter, E. C., Frank, M. J., Pajtas, P. E., Santesso, D. L., & Culhane, M. (2008). Single dose of a dopamine agonist impairs reinforcement learning in humans: Behavioral evidence from a laboratory-based measure of reward responsiveness. Psychopharmacology, 196(2), 221–232. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-007-0957-y

- Salazar, R. D., Weizenbaum, E., Ellis, T. D., Earhart, G. M., Ford, M. P., Dibble, L. E., & Cronin-Golomb, A. (2019). Predictors of self-perceived stigma in Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders, 60, 76–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parkreldis.2018.09.028

- Shergill, S. S., Samson, G., Bays, P. M., Frith, C. D., & Wolpert, D. M. (2005). Evidence for sensory prediction deficits in schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(12), 2384–2386. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.162.12.2384

- Smith, B., Fowler, D. G., Freeman, D., Bebbington, P., Bashforth, H., Garety, P., Dunn, G., & Kuipers, E. (2006). Emotion and psychosis: Links between depression, self-esteem, negative schematic beliefs and delusions and hallucinations. Schizophrenia Research, 86(1-3), 181–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2006.06.018

- Startup, H., Pugh, K., Dunn, G., Cordwell, J., Mander, H., Černis, E., Wingham, G., Shirvell, K., Kingdon, D., & Freeman, D. (2016). Worry processes in patients with persecutory delusions. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 55(4), 387–400. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12109

- Synofzik, M., Thier, P., Leube, D. T., Schlotterbeck, P., & Lindner, A. (2010). Misattributions of agency in schizophrenia are based on imprecise predictions about the sensory consequences of one's actions. Brain, 133(1), 262–271. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awp291

- Todd, D., Simpson, J., & Murray, C. (2010). An interpretative phenomenological analysis of delusions in people with Parkinson's disease. Disability and Rehabilitation, 32(15), 1291–1299. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638280903514705

- Todd, J., & Dewhurst, K. (1955). The Othello syndrome: A study in the psychopathology of sexual jealousy. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 122(4), 367–374. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005053-195510000-00008

- Turkington, D., & Siddle, R. (1998). Cognitive therapy for the treatment of delusions. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 4(4), 235–241. https://doi.org/10.1192/apt.4.4.235

- Vernon, D., Haenschel, C., Dwivedi, P., & Gruzelier, J. (2005). Slow habituation of induced gamma and beta oscillations in association with unreality experiences in schizotypy. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 56(1), 15–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2004.09.012

- Von Helmholtz, H. (1978/1971). The facts of perception. In R. Kahn (Ed.), Selected writings of Hermann von Helmholtz. Wesleyan University Press.

- Weintraub, D., & Mamikonyan, E. (2019). The neuropsychiatry of Parkinson disease: A perfect storm. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 27(9), 998–1018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2019.03.002