ABSTRACT

This paper analyses recent shifts in urban sustainability discourse and practice through a critical review of the historical development of the concept from the 1970s through to the global economic crisis in the 2007 and its fragmentation into the 2010s. Using this periodisation, the paper shows how the content of urban sustainability discourse has changed. First, it illustrates that the dominant assumption of sustainable cities’ discourse was to utilise economic growth to ecologically modernise urban environments. Second, it examines how the global economic crisis has intensified this fix and led to a new, even narrower emphasis on the techno-economic value of those aspects of urban environment that have economic and market potential. Third, it analyses the fragmenting of sustainable cities’ discourse into a set of competing logics that reflect this narrower agenda. This paper argues that the sustainable city has been absorbed into these new logics that are much more narrowly techno-economically focused and are squeezing out traditional concerns with social justice and equity.

1. Introduction

During the 2000s, critical accounts of sustainable cities’ debates highlighted the rhetorical power of the term and the view that the “present organization of cities is not sustainable but can be made so if the correct measures are taken” (Brand Citation2007, pp. 623–624, original emphasis). Yet, this view was built on an assumption of continued economic growth underpinning the management of urban environments and social concerns (Hajer Citation1995). But what happens when there is limited or no growth? Much of the economic and financial basis underpinning the multi-level governance and institutionalisation of sustainable cities (Bulkeley and Betsill Citation2003) was built on a model of global economic organisation that had liberal financial flows with unsustainable relationships of lending and debt at its core. A combination of financialisation, neoliberal ideology, globalisation, and state-driven welfare and austerity programmes have underpinned systemic inequalities and driven concerns about the city and social justice (Peck Citation2012, Fainstein Citation2016).

Since the global economic crisis of 2007, “conventional” sustainable cities’ discourse has been challenged (Flint and Raco Citation2012) and has become fragmented. There has been an apparent unbundling into a more fragmented landscape of multiple and competing conceptions of the relations between cities and ecology, characterised as: urban resilience (Newman et al. Citation2009, Gleeson Citation2014), urban carbon regulation (While et al. Citation2010) and low carbon transitions (Bulkeley et al. Citation2011), sustainable growth for cities, smart urbanism (Hollands Citation2008, Kitchin Citation2014, Marvin et al. Citation2015), urban securitisation (Hodson and Marvin Citation2009, Citation2010, Davis Citation2010) and experimental cities as test-beds (Karvonen and Van Heur Citation2014) (this issue). The unbundling of sustainable cities’ discourse into a set of competing environmental logics is being promoted through an epistemic politics (Andersen and Atkinson Citation2013) built on particular coalitions of international agencies, research funders and donors, academic research centres and professional groupings. In both the global north and south, multiple cities are now being enrolled into new international urban networks based on themes that include resilience, smart, climate change, low carbon and so on that have an ambiguous relationship to the conventional sustainable cities’ discourse (Acuto Citation2016, Davidson and Gleeson Citation2015) (this issue). The sustainable city appears to be weakening as the dominant policy or research discourse of the future of the urban environments.

This paper is concerned with trying to understand the reasons for the fragmentation of the remarkably stable and long-standing concept of the sustainable city and the wider urban consequences of the multiple logics that appear to have developed in its wake. The central question the paper asks is whether these new logics represent the intensification or the transformation of sustainable cities’ debates. The issue here is a struggle between whether responses are becoming even more focused on the economic dimensions of sustainable priorities, a sort of neoliberal redux (Peck et al. Citation2013), thereby squeezing out what were wider concerns about social control and environmental justice or whether, instead, there is a move to open up the agenda and consider wider priorities about the value of economic growth, different forms of economic activity or even de-growth (Jackson Citation2009, Schneider et al. Citation2010) by re-prioritising ecological, social justice or quality of life issues. Has the sustainable city been neutralised as a concept and seamlessly absorbed into new urban economic development logics? In asking this question, we draw upon a range of different types of evidence some from over the last 40 years of sustainable cities’ policy, debate and research as well as others from outside on the global economic crisis. In doing this, we synthesise a range of academic literatures but particularly from urban studies and urban geography. Funding from Mistra Urban Futures’ GAPS project enabled a review of the literature and an assessment of the current state of play of sustainable cities’ discourse in case-study cities (this issue).

The motivation for this particular paper, in this wider project, was to ask questions about the fragmentation of sustainable cities’ discourse that appear to be taken for granted and naturalised rather than opened up and looked at critically as being shaped by important changes in the wider societal context. In doing this, we are also aware that the paper is primarily – but not solely – based on evidence from the global north, although we do include evidence from international agencies and programmes concerned with the urban environment in multiple urban contexts.

In order to address this question, the argument in the rest of the paper is structured into five sections. First, we briefly examine the development of the first phase of sustainable cities’ discourse and the way in which the urban environmental project largely moved from radical roots until it sought reform within an ecological modernisation paradigm. Second, we review the new pressures that emerge when continued economic growth is brought into question and ask whether this latest phase has the potential to intensify or transform conventional sustainable cities’ discourse. Third, we provide a (selective) review of the emergence of new environmental logics examining their relationships with conventional sustainable cities’ discourse. Fourth, we discuss whether we are seeing the death of the “sustainable city”. Finally, the paper concludes by arguing that within the discourse and practice of sustainable cities, there has been a refocusing on the techno-economic value and potential of urban environments placing traditional concerns with social justice and equity under significant pressure. Consequently, there is a need to expose the hidden assumptions of these new logics and develop a more critical view of what has been lost and what could be reincorporated from sustainable cities’ debates.

2. The environmental fix of sustainable cities

In order to understand the sustainable cities’ agenda at the start of the twenty-first century, we need to place contemporary debates in a wider developmental context. This is necessary in order to identify the changing dynamics of the debate over time. Contemporary sustainable cities’ debates can be understood as emerging out of the multiple crises – economic, ecological, of industrial capitalism and urbanism – particularly as they were perceived by Western nation states in the late 1960s and 1970s. Environmental politics as an urban concern resonated with questioning the role of cities in industrial capitalism and with processes of urbanisation and the environmental consequences of this, particularly issues of pollution and quality of urban life (Meadows et al. Citation1972). Environmental questions of the cities of the north were also increasingly pertinent to the global south given the rapid growth of cities in the south (1972 United Nations Conference on the Human Environment in Stockholm; 1976 United Nations Habitat Conference on Human Settlements in Vancouver).

An emerging view in the 1970s was of a developing ecological crisis, the role of industrial capitalism and urbanisation in producing this and the need for radical responses. This was more specifically framed through seeing the problem to be addressed as one of pollution and the need to regulate at the national level for environmental protection. This was important in framing a role for cities as producers of environmental problems and it also laid the foundations for thinking about how cities could be viewed not only through the relationship of economy to ecology but also how this relationship could be reworked.

Intellectually, underneath this coherent narrative were fundamental struggles over what appropriate relationships between economic development and ecological consequences looked like and how they could be understood. In the 1970s, the context of crisis in the world capitalist system (Wallerstein Citation1974, O’Connor Citation1987) saw the articulation of an argument about planetary limits to growth. Based on computerised forecasting, developmental trends suggested that limits to growth would be reached within a century (Meadows et al. Citation1972). The Ecologist magazine produced its Blueprint for Survival issue, which was later published as a best-selling book and whose response was to promote a new relationship between economy and ecology built on small, decentralised community responses that promoted social cohesion and well-being, controls on population, low-impact technologies and sustainable resource management (Goldsmith and Allen Citation1972). Efforts to rethink relationships between economy and ecology were mediated through concepts such as steady-state economy (Daly Citation1973) and socially useful production (Smith Citation2014). These were efforts to construct responses to the crisis of capitalism where solutions were fundamentally based in addressing ecological concerns.

Rather than environmental challenges being seen as “naturally” occurring, ecological views saw environmental degradation as rooted in societal-nature configurations. The issue became not one of thinking narrowly about environmental challenges but how these were embedded in the wider organisation of capitalist economic systems and raising moral, ethical, political and institutional concerns and profound concerns for relationships between the human and non-human world. How to reconfigure relationships between economy and ecology required thinking about what kind of ecology and who were the agents of such change. This brought various hybrids and fusions of existing (socialist, liberal, conservative, feminist and communitarian) political ideologies with attempts to understand unfolding ecological challenges (Dobson and Eckersley Citation2006).

Attempts to reconfigure relationships between economy and ecology were linked to political mobilisations. This resulted, for example, in intellectual and political efforts to build alliances between red and green politics. In writings of some foresight, Andre Gorz suggested that the agents of such reconfiguration were not the industrial working class, privileged in Marxist analysis, but new social movements. Anticipating the shifts in economic globalisation of the coming decades, Gorz suggested profound changes in the nature of work and promoted collaboration between workers movements and ecological movements in a red–green alliance (Citation1979, Citation1982). Politically, there were attempts to enact such alliance, particularly in Germany, but where there were often tensions between dark and light forms of green activity and between revolutionary and reformist approaches. Beyond these attempts to build and institutionalise red–green alliances and new forms of eco-socialism, there were also alternative visions from the left including those, such as Bookchin (Citation1982), who promoted an ecological position based on a libertarian-socialist, anarchist tradition of direct action.

Within these wider debates, cities were being positioned as sites where the relationships between economic organisation, ecological consequences, responses and social organisation could be rethought and the critical question was whether the change that followed from this could be managed within the parameters of the capitalist system or whether it required revolutionary transformation. This raised numerous fundamental issues about conceptualisations of sustainability and about what was meant by the term. What was being sustained, why, how, when, for whom, by whom and how would we know? It also made the forms of social organisation of response key (this issue).

The struggle over whether a revolutionary or a reformist approach was needed was strongly conditioned by wider global economic, ideological and political shifts through the 1970s and 1980s (Held et al. Citation1999, Hirst et al. Citation2009). The energy infusing this struggle weakened and began to dissipate following the collapse of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the collapse of a counter-hegemonic politics to the neoliberalism that was ascendant in the West and claims of the triumph of Western liberal democracy (Fukuyama Citation1992).

Within these circumstances, there was something of a shift from the debate being predicated on various forms of eco-socialism to the dominance of arguments around eco-capitalism; the dichotomy that was constructed between these two approaches was criticised (Sarkar Citation1999, Rogers Citation2010). The greening of capitalism became the means through which sustainability concerns were communicated and governed. This view did not see capitalism as the problem of sustainability but as its dynamic solution. This led to policy proposals that market-based instruments could simultaneously shape sustainability and development – the market was the mechanism through which environmental problems could be addressed (Mol Citation2002).

By the late 1980s, the radical forms of response that were being raised in the 1970s, and which necessitated rethinking capitalism, had undergone a process of being replaced by the view that ecological crisis could be solved through an agenda developed and enacted through society’s existing institutions. This view was most notably made by the 1987 World Commission on Environment and Development (Brundtland Report), Our Common Future. The Brundtland Report set out the (still) commonly used definition of sustainable development as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (Brundtland Commission Citation1987). The Brundtland report pointed out that it was “careful to base our recommendations on the realities of present institutions, on what can and must be accomplished today” (Brundtland Commission Citation1987). In doing this, Brundtland was critical in framing the need for a response to the ecological crisis that could be attractive and also incorporated into the agendas of large international agenda-setting organisations such as the World Bank and IMF. This approach to sustainable development, that was acceptable to global economic organisations, also meant that Brundtland, for radical critics, developed sustainable development as a concept that is “a rhetorical ploy which conceals a strategy for sustaining development rather than addressing the causes of the ecological crisis” (Hajer Citation1995, p. 12) and that accepts notions of continued growth.

The key issue from the point of view of sustainable cities’ debates is that the global institutional architecture – UN, World Bank, IMF and OECD – was increasingly being reconfigured around a view of sustainable development that was based on a broadly shared approach and set of concepts. These were international institutions that, particularly in the case of the IMF and the World Bank, through the 1970s and 1980s, were being reconfigured from their original purpose under the Bretton Woods System and in support of the developing neoliberal agenda (Hirst et al. Citation2009). The significant implication of this was that, rather than episodic responses, a broadly shared approach was incorporated into a suite of existing international institutions. What followed from this was the need for national and sub-national action on sustainable development as the agenda cascaded down from institutions as part of a new multi-level governance of sustainable development (Bulkeley Citation2005).

Agenda 21 was the non-binding, largely process-based action plan on sustainable development that was developed at the Rio summit in 1992. Local Agenda 21 came out of the Agenda 21 process: “Because so many of the problems and solutions being addressed by Agenda 21 have their roots in local activities, the participation and cooperation of local authorities will be a determining factor in fulfilling its objectives” (28.1). What this meant was that local authorities should be engaged in picking and mixing policy measures in context – in relation to different prescribed elements of an overall sustainable urban development or sustainable cities’ agenda. This picking and mixing usually involved sustainable architecture and buildings, transport, energy, sustainable space, social and environmental justice and economic development. Through Local Agenda 21, sustainability became enshrined in urban plans and policy where cities were central to the problematic of global ecological “crisis” and sustainability and through local plans and new forms of local partnerships and interrelationships constituted a response. Local authorities were encouraged to build a Local Agenda 21 plan through dialogue and creating consensus between local citizens, local organisations and private business (Local Agenda 21 Citation1992). Partnerships should also be built with international organisations such as UNDP, UNEP, Habitat and others to build local capacity and to build networks and exchange with other cities in both the global north and south. This emphasis on shifting the terms of the debate from the “problem” of cities to the potential of cities as contexts of response was also central to the 1996 Istanbul United Nations Conference on Human Settlements (also known as Habitat II).

Brundtland and particularly the Rio Summit were important in seeing cities not only as problems but also as sites of response and thus in setting expectations about the role of local authorities. It shifted the focus from diagnosis to action while at the same time sealing off any fundamental consideration of the nature of the problem. It developed a framework of institutional and policy initiatives for reorienting economic and social practices in favour of more environment-friendly strategies of production and consumption (Brand and Thomas Citation2005, p. 6).

This view brings a practice of sustainable cities where the management of social and environmental concerns is predicated on the proceeds of economic growth. The dominance of this view through the 1990s and into the 2000s within national governments, city authorities and other agencies was apparent in the EU, North America and other areas of the world. This was a consensual view of the management – or an accommodation – between notions of economic competitiveness, social justice and environmental protection that was thin on conflict in what has been characterised as an era of post-politics (Swyngedouw Citation2009).

This has produced a “win-win” view of the relationship between economy and ecology that is based on a

policy discourse of ecological modernization [that] recognizes the ecological crisis as evidence of a fundamental omission in the workings of the institutions of modern society. Yet, unlike the radical environmental movements of the 1970s, it suggests that environmental problems can be solved in accordance with the workings of the main institutional arrangements of society. (Hajer Citation1995, p. 3)

Running concurrently to the economic, ecological and urbanisation crises of the 1970s was a challenge to post-Second World War forms of governing and the rise of public institutions (Jessop Citation2002). They were challenged at the level of economic organisation, with their regulatory roles in supporting Fordist–Keynesian modes of economic activity, and also through the 1980s and 1990s through increasingly experimental organisation of forms of governing that encompassed private interests and that by-passed established governing structures (Brenner Citation2004). By the 1990s, a new urban politics that promoted an entrepreneurial and managerial role for city governing had become visible and this rested on a view of the city as outward facing in terms of attracting investment and tourism and also as a basis for comparison of urban success vis-à-vis other cities (Harvey Citation1989). This emergence of managerialism and audit cultures in urban economies was fused with debates around sustainable cities. The threefold city relationships, encouraged through Agenda 21, with global institutions and national governments, internal capacities and partnerships, and horizontal networks combined to produce different degrees of capability to act in urban settings. In an era of economic liberalism and globalisation, cities were frequently being exhorted to be entrepreneurial, to position themselves to attract inward investment and, in organising economic activity in this way the management of environmental protection and social justice became caught up in particular searches for sustainability fixes (While et al. Citation2004). Urban boosterism and the search for growth incorporated environmental and social justice concerns as part of a process of constituting an externally facing place-based identity. This ongoing process of urban management was built on league tables, performance metrics and the perceptions of others.

Yet, the effects of this in terms of sustainability have been limited. This has been produced by architectures of governing at a distance that involve complex networks where decision-making is not constituted through struggle but through the redistribution of power to selective agents usually of business. In the balance between transformation and the status quo, the advantage lies with the latter. The result being that “into the new millennium, enthusiasm seems to have waned and hopes faded. It is already common to find academic commentators and dispirited professionals bemoaning the meagre results of years of urban environmental management” (Brand and Thomas Citation2005, p. 2).

3. Intensifying or transforming sustainable cities?

Moving into the 2000s, sustainable cities’ discourse was confronted by a wide range of additional economic and ecological issues that began to question the assumptions and basis of existing debates (Flint and Raco Citation2012). Critical accounts of sustainable cities’ debates highlighted the rhetorical power of the term and the view that

it is constructed around a loose assemblage of problems, analytic fields and data (on resources, energy flows, production and consumption patterns, waste and pollution, lifestyles, and so on) which purport to demonstrate that the present organisation of cities is not sustainable but can be made so if the correct measures are taken. (Brand Citation2007, pp. 623–624, original emphasis)

Yet, as we have discussed above, this is built on a view of economic growth underpinning the management of urban environments and social concerns. But what happens when there is limited or no growth? What has followed in policy terms has been the pre-eminence of a form of austerity governance as response (Peck Citation2012) with a secondary response of new forms of sustainable stimulus measures as an alternative (Luke Citation2008). Again, following the global financial crisis in 2008, as with the 1970s, we are seeing debates that question the very sustainability of a growth-based economic paradigm (Jackson Citation2009). Furthermore, austerity and its implications for “good governance” and the role of cities are under-explored. The weakening of public spending power and the promotion of a cuts agenda open up the possibilities for new private sector involvement in urban governance (Peck Citation2012). It also creates a space for alternatives and local, voluntary and charity sector responses to be given oxygen (Seyfang and Smith Citation2007, Hodson et al. Citation2016).

Sustainable cities’ debates have long been a site of struggle. Yet, the discursive mediation of this struggle was governed within parameters set by the post-Brundtland sustainable cities’ agenda and which, now, is fragmenting. This means that not only is the realisation of sustainable cities a site of limited struggle – as the post-political perspective suggests (Swyngedouw Citation2009) and where “leading” cities exemplify sustainability practices (Beatley Citation2000) – but struggle now stretches to the discursive basis through which “sustainable cities” are envisaged. The fundamental struggle is how relationships between economy, ecology and the social are understood, but also the scale at which they are organised and the capacities that inform this. The struggle through which the intensification or the transformation of sustainable cities’ discourse is being fought is underpinned by five elements.

First, sustainable development, post-Brundtland, and its manifestation in the dominant sustainable cities’ debate was based on both the view that capitalism was the answer to environmental problems rather than their cause and that economic growth would provide the resources for managing urban sustainability. There is significant pressure from the ideology of austerity governance for how sustainable cities’ issues are seen and that is reshaping the context in which debates about sustainable cities’ are currently being undertaken. This raises issues for whether the post-Rio dominant view of sustainable cities can be achieved and if so how “conventional” or “sustainable” the modes of growth are envisaged. Or, alternatively, whether the crisis in the social, political and institutional organisation of the dominant mode of economic growth creates a more fruitful space for experimentation with alternative modes of economic organisation that are underpinned by alternative modes of social and ecological organisation. The economic and financial crisis of 2007/2008 made visible that global, neoliberal growth was built on a logic of financialisation that was predicated on systemic social injustice and was unsustainable (Fainstein Citation2016). Global growth has remained tepid in the years since. There are undoubtedly efforts to get the growth machine (Logan and Molotch Citation1987) going again, through state-spatial strategies and governance restructuring, to get the urban neoliberal show back on the road (Peck et al. Citation2013). Yet, in a context of low growth, long-muted debates around steady-state economies (Kerschner Citation2010) and the desirability of de-growth strategies (Schneider et al. Citation2010) have started to become heard again. This struggle, in many ways, can be seen as a contemporary twist on debates between eco-capitalists and eco-socialists.

Second, these debates about the type of economic organisation that is desirable infuse how environmental issues are seen. In particular, pressure relates to the ways in which human-induced processes are producing anthropogenic global ecological change – best exemplified by climate change – that is reshaping the very ecological context within which cities are attempting to ensure their reproduction. The struggle here is the long-standing one of whether sustainability concerns – from CO2 emissions reduction to air pollution – can be achieved through capitalist structures. Debates around natural resource management, for example, have seen struggle about whether there needs to be relative decoupling between resource use and economic growth or absolute decoupling (Hodson et al. Citation2012). The first of these, broadly speaking, supports an eco-capitalist view that improving resource efficiencies through intensification of the capitalist system does not require systemic transformation. An absolute view of decoupling would suggest the opposite and would be closely aligned with strategies of de-growth or steady-state economies and planetary boundaries. The issue is whether the organisation of economies and, in this example, resource flows, is on the basis of growth and principles of efficiency or no or low growth and the principle of sufficiency (Princen Citation2005). To take a different example, dominant policy responses to air pollution in urban areas through market-based responses, in the context of the U.K., for example, are largely seen to have failed. Much richer understandings of the political ecology of urban air are needed that recognises linkages between urban pollution, global warming, urban heat-island effects, spatial movements of polluted air, the morphology of the built environment, the development of air conditioning technology and so on (Graham Citation2015).

Third, social justice and cohesion agendas under sustainable cities’ discourse necessitated economic growth and redistribution of its proceeds. This view was underpinned by promoting work-based employment. This agenda has opened up again as growth has stalled. Not only has growth stalled but work-based employment has become increasingly precarious and is likely to be more so in the face of increasing societal automation (Mason Citation2015) and the growth of smart forms of urbanism (Marvin et al. Citation2015). This has seen renewed life breathed into debates that seek to understand issues of social justice beyond the metrics of GDP (Stiglitz et al. Citation2009), debates about well-being (Edwards et al. Citation2016) and the provision of universal basic income to counteract a precarious future world of work (Scnricek and Williams Citation2015).

Fourth, the scalar context at which economy, environmental and social are most “appropriately” organised is also a site of struggle. Elite decision-makers seeking to promote new forms of eco-capitalism often highlight the need for urban agglomerations, city-regions and pan-urban collaborations, with new forms of governance that by-pass existing forms of governance to get growth moving (Brenner and Schmid Citation2015). By contrast, in a context where neoliberal urban growth is seen not to be working, grassroots movements have been engaged in a wide range of neighbourhood and networked forms of DiY urbanism, tactical forms of urbanism and horizontal urbanism (Tonkiss Citation2013, Ferreri Citation2015). The issue is to what extent are multi-level governance frameworks re-enforcing the dominant strand of sustainable cities’ debates of the last three decades or are possibilities for alternatives likely to flourish? This is an issue of governing and what forms of governing are possible and become visible. It may be that there are numerous forms of fundamentally different response ranging from intensified hyper-liberal development, to new forms of localisation or municipal pragmatism that recognises that it is not possible to balance economic, environmental and social in all instances (Whitehead Citation2012).

Fifth, what these different elements of economy, environment, social and scale speak to is a struggle to define whose knowledge counts in constituting the capability to act and to define what the future shape of “sustainable cities” discourse looks like (Flint and Raco Citation2012, Andersen and Atkinson Citation2013). This is a question of not only how ecologies are constructed but also according to what logics. This is the struggle. This means understanding the interrelationships between economic modes of organisation, ecological modes of organisation and social modes of organisation and the rationalities and philosophies informing them.

This being the case, there are numerous forms of potentially, fundamentally different forms of response. It also means recognising that there are many potential contributions to the emerging shape of sustainable cities’ debates both within the context of actually existing cities and also in more generic terms in respect of debates about sustainable cities. This paper contributes substantively to the latter of these issues through examining the emergence of new logics of sustainable cities. In examining, we seek to understand whether what these responses add up to are a set of logics that re-prioritise and re-intensify the economic, technical and security dimensions of sustainable cities at the expense of wider questions of social equity and the social control of infrastructure and critical resources. The issue here is whether the range of social interests involved in shaping priorities are exclusive or inclusive coalitions and whether there is less focus on priorities linked with social justice and the social control of resources. In the next section, we see how these wider issues are being translated into, and exemplified by, newly emerging logics.

4. Beyond sustainable cities – emerging logics

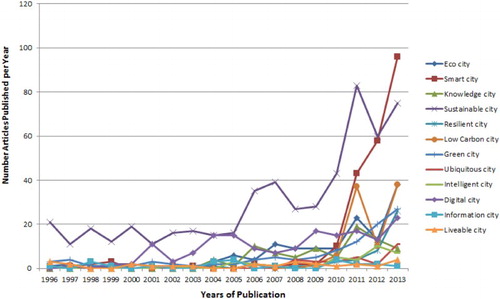

Given this changed socio-economic context, the challenge is to critically examine in a programmatic and comparative manner the emerging dynamics of the contemporary sustainable cities’ agenda. There have clearly been significant shifts in the “state of play” of sustainable city policy and research logics over the last decade (see reviews in Raco and Flint Citation2012, Whitehead Citation2012, Hodson and Marvin Citation2014). More recent work on the emergence of new city categories graphically – see – charts the evolution of new city categories in the period between 1996 and 2013 in the academic domain (see de Jong et al. Citation2015).

Figure 1. Emerging urban logics. Source: de Jong et al. (Citation2015).

While the sustainable city continues to be a widely used concept, what is significant about this bibliometric analysis is how new urban concepts have emerged, particularly in the period after the economic crisis of 2007/2008. Critically, this shows that the “‘low carbon city’ and ‘resilient city’ have both emerged strongly since 2009, (and the) use of ‘smart city’ has also exponentially increased since 2009, to the extent that by 2012 it has even managed to eclipse ‘sustainable city’” (de Jong et al. Citation2015, p. 5). The emergence of low carbon and resilience is linked directly to the acceleration, extension and roll-out of urban responses to the global climate debate in terms of mitigation and adaptation (see Bulkeley et al. Citation2011). However, what is also of interest is the extent to which the global financial crisis, as well as global climate change, may have reshaped the context of sustainable cities’ discourse and contributed to new city categories emerging. We are seeking to understand whether these emerging responses seek to re-prioritise and re-intensify the economic, technical and security dimensions of sustainable cities’ discourse at the expense of wider questions of social equity and the social control of resources.

The issue is whether the coalitions of social interests involved in shaping priorities is exclusive or inclusive and whether there is a reduced focus on priorities linked with social justice and the social control of resources. Although space presents us from discussing these in detail (for recent reviews, see Flint and Raco Citation2012, Hodson and Marvin Citation2014, de Jong et al. Citation2015) what is apparent is that these new logics have a more selective focus on particular urban ecologies and do not seek to develop the comprehensive and holistic view of the urban environment contained in sustainable cities’ discourse. We argue that these new logics have a narrower technical, economic and security focus than the wider commitments to justice and equity contained in sustainable cities’ discourse and are explicitly designed to transcend ecological limits. We consider each of these points in turn below.

4.1. Fragmentation – multiple urban environments

The new urban logics each have a selective environmental focus. They are no longer explicitly attempting to construct a broad holistic view of the urban environment that was assumed in Agenda 21 and the sustainable cities’ discourse. Instead, each new logic exemplifies a much more focused view of the ecologies and resource flows that are potentially valuable. A comprehensive view of the urban environment is unbundled and selectively reassembled in particular configurations, mediated through the frameworks and techniques of each approach. We can characterise these as parallel processes of fragmentation in how urban ecology is viewed, underpinning intensification of the logic of ecological modernisation, refocusing on economically valuable ecologies. Each logic works through particular configurations of knowledge and expertise that incorporate techniques and practices that frame how an urban environment is viewed and understood. Low carbon cities’ approaches, for example, use accounting and monitoring systems to build complex models of the circulation of carbon through urban environments (While et al. Citation2010). Such techniques then place a premium on understanding the carbon component of multiple resource flows (energy, mobility and food, etc.). Urban resilience refocuses on those aspects of environment and resource flows that are critical to sustaining the urban life and economic reproduction in a particular context (Hodson and Marvin Citation2009, Davoudi Citation2012a). While smart technologies place a premium on digital control and datafication, the claim is that existing ecologies can be better understood through monitoring and made operationally more efficient through smart girds and mobilities (Marvin et al. Citation2015). The emergence of multiple approaches has to led to parallel processes of unbundling of a holistic approach to the urban environment and the selective reassembling and re-bundling of those aspects of the urban environment that meet the priorities of the different approaches.

4.2. Intensification – overcoming limits to urban growth

As the different approaches focus selectively on particular aspects of the urban environment, these processes have a tendency to reinforce and intensify two particular dimensions of sustainable cities’ practice and weaken a third.

First, they further reinforce the importance of the “economic” value of selected ecologies. While the “urban sustainability fix” has continued to develop responses that attempt to incorporate ecological and environmental conditions into economic urban responses through ecological modernisation (see While et al. Citation2004, Citation2010) we argue that these processes have been subject to new forms of intensification. The emerging logics are more explicitly focused on developing selected aspects of urban ecology as a basis for new rounds of economic growth. Social interests in particular urban contexts can seek to gain first mover status or competitive advantage through the development of low carbon or green technologies as a basis for new forms of economic growth and specialisation. An extension of this is the way that smart technologies might be able to accelerate the growth of new opportunities in environmental sensing or new services that improve the operational efficiency of infrastructure flows (see, Marvin et al. Citation2015). There are increased pressures to find monetary values to assess the effectiveness and efficiency of investments in green infrastructures – the ability to improve public health or provide buffering to climate variability. There is intensification of the ways in which ecology is seen as an asset, justified on economic grounds for both new growth and more efficiency through austerity governance.

Second, there are increased attempts to make connections between national state security and resource security and the rescaling of these issues to the urban context (Hodson and Marvin Citation2009, Davoudi Citation2012b). Rather than being about becoming self-sufficient in order to meet limits to growth, this strategy is more about the extent to which an urban context can secure the resources and provide the capacity and resources to ensure its economic and ecological reproduction under conditions of economic and ecological uncertainty and turbulence. A combination of approaches, including digital and resilience, is increasing focus on developing more proactive strategies to ensure continued urban reproduction. We argue that this is consistent with self-sufficiency and circulatory aspects of the sustainable city but that this is underpinned by different types of drivers; rather than working within limits, this is about working to ensure that limits to continue urban growth under conditions of uncertainty can be transcended.

What, we argue, this adds up to is a different logic of sustainable cities. Rather than using economic growth as a basis for ecological modernisation of urban economies, a new set of issues are becoming prominent. In particular, there is an emphasis on how the urban environment, or different dimensions of the urban environment, can in itself either provide a focus for economic growth (new services, products, efficiencies and transitions); how ecology can be organised to pursue strategies of preparedness and protection required to try to ensure continued economic reproduction under conditions of turbulence (e.g. extreme weather, energy and water stress). This has placed a premium on economic and technological responses and reshaped some of the commitments in conventional sustainable cities’ discourse.

The third issue is the extent to which emerging approaches, because of their techno-economic focus, weaken the conventional commitment of sustainable cities’ discourse to social justice and intergenerational equity. Despite the difficulties of operationalising this commitment and translating it into practice, the sustainable cities’ discourse did contain this commitment to consider wider social issues involved in environmental priorities. Our concern with the newly emerging approaches is that this commitment to social justice issues is either absent or weakened when compared with sustainable cities’ discourse. Consequently, it is not surprising that a number of the critiques of smart urbanism and urban resilience have raised wider issues about the dominance of economic and security priorities and a subsequent weakening of the social justice dimensions of these policy responses. The point is that these dimensions can no longer be taken for granted and work to try to reinsert social justice arguments is key.

4.3. Urban experimentation

Within academic discourse, there is a continued commitment to sustainable cities’ discourses and a parallel process of fragmentation in urban logics. This leaves the issue of what is happening in the policy domain. Our argument helps us to understand how the new logics can be held together, to some extent, with an intensified logic of ecological modernisation, where techno-economic dimensions have become prioritised and where social questions are less significant. But what are the socio-material consequences of fragmentation? There appear to be three things happening here that are important.

First, a key theme that potentially cuts across all the emerging logics discussed so far is the degree to which the myriad responses can be regarded as forms of sustainable experimentation (Evans Citation2011, Hoffman Citation2011, Bulkeley and Castan Broto Citation2013). In response to the intensification of economic and ecological challenges, the urban responses required have to address increasingly “systemic” issues about the social and technical organisation of cities. Within a framework where urban capacity to develop systemic responses has in a number of contexts been increasingly limited by a combination of economic austerity, reductions in public expenditure and continued privatisation and liberalisation of infrastructure more experimental responses have had to be developed in the absence of national and international agreements. Yet, what characterises these responses in a particular urban context can be extremely diverse with multiple forms of experimentation that can include: networked responses through organisations such as ICLEI, C40, and Transitions Towns; localised and community responses and low budget forms of urbanism; and private, corporate responses.

Second, these responses are likely to only be loosely connected to the formal international and national policy priorities that underpinned the multi-level framework of sustainable cities’ responses. Through these experiments, we can see how new coalitions of cities, citizen groups, universities and research organisations, and corporations are seeking to address the causes and symptoms of global economic crisis and ecological change (Karvonen and Van Heur Citation2014). This pushes the centre of gravity from multilateral treaty-making processes to a more diverse set of activities. These forms of experimentation need to be understood through the ways in which urban authority is being restructured and how the potential for strategic responses is structured through urban political economies (While et al. Citation2010). This means that analysis would expect to find differences in the style of experimentation emerging in different kinds of cities, global regions and where varying urban dynamics – of growth, politics, social change and so on – are taking place.

Third, each of the different urban imaginaries is associated with particular networks, techniques and league tables. What is critical to understand is that new social interests and expertise have been brought into the urban context from disaster management, corporate forms of smart and software, and new forms of ecological understanding from industrial ecology. These are not conventional sources of urban planning. Associated with each logic are visions of changed ecology and infrastructure that resonate to a greater and lesser extent with different urban contexts. Who mediates between these logics and existing urban contexts, how and with what effects, becomes a critical issue.

5. Conclusion

In this paper, we set out how the sustainable city has become fragmented and the way in which a series of emerging logics pose series challenges to the dominant sustainable cities’ discourse. Our central concern is that although there may be increasing diversity in the institutional and organisational diversity of these responses, they can also significantly intensify the focus on the techno-economic and security dimensions of ecological responses while squeezing out concerns about social justice and equity. Yet, debates about what is happening to the sustainable cities’ agenda have some distance yet to run. This paper contributes to this ongoing debate. There is, however, a need to see these emerging issues and logics not solely in isolation but to think in an integrated way about what these logics add up to. There is a critical need to examine in a systemic and comparative way across different urban contexts a range of questions and issues that are raised by these emerging logics.

5.1. The slow death of the sustainable city?

outlines the processual and longer term development of sustainable cities’ discourse since the 1960s. This highlights, on the one hand, the remarkable consistency and continuity in sustainable cities’ debates but also the ways in which there have been ruptures and change associated with wider societal context – especially the importance of economic crisis and ecological change in reshaping the contours of the debate. We have argued in the paper that there are three broad phases in the debates recognising that these periods overlap and are contested.

Table 1. Periodisation of sustainable cities’ discourse.

Initially, in the 1960s–1970s, in response to global economic and ecological pressures, there was a period of experimentation with energy and ecologies in order to attempt to overcome limits to growth with alternative technologies and modes of social control of ecology. During this period, cities were largely seen as contributing to the problematic and were often viewed as sites of experimentation with alternative technologies and forms of social organisation. Rather than providing an alternative development trajectory, state institutions, and to more limited extent, the market, took up the more efficiency and economy-orientated parts of the alternative critique in order improve the performance of urban infrastructure.

In the 1980s–1990s, these more efficiency-focused arguments were taken up and cascaded through the governance structure of international institutions. Cities were seen not only as problems but also as sites where the potential of new technologies could help improve the performance of urban infrastructures, stimulate innovation and economic growth and potentially produce more justice and equitable urban environments. Here, the comprehensive view of sustainable cities’ discourse emerged in the network and programmes of Agenda 21.

Finally, in the mid-2000s, this position came under increasing pressure as responses to the global financial crisis squeezed many (but not all) urban budgets and the recognition of increasing climate change raised questions about the effectiveness of urban responses to ecological change. In response, sustainable cities’ discourse became increasingly fragmented as multiple ecological logics emerged, each produced through particular coalitions of academics, policy-makers and networks of cities. Sustainable cities’ thinking was apparently unproblematically absorbed within these logics but there was increasing focus on the economic and security potential of those ecological and environmental services which were viewed as having economic potential in a period of no or low growth and as essential to urban reproduction. This led to increasing focus on strategically important environmental resources and assets and the weakening of the commitment to comprehensive approaches and concerns with social justice and equity.

5.2. Future urban research

There are three sets of issues that need further more comparative research across different urban contexts. First, it is important that there is further work to understand what the relevance of these emerging logics is in different urban contexts and whether (and if so how) they reshape sustainable cities’ discourse. To do this, further empirical and theoretical work is required to assess what evidence there is of these logics emerging in the local context and if so which logics dominate, in what ways are they configured in different contexts of the global north and south and why (this issue). It is also necessary to address the spatial politics of this through understanding whether these logics are external priorities “dropping in” to cities or whether those representing cities able to develop their own view of sustainable futures. How do they interact and become stabilised in particular socio-material configurations?

Second, central to this is understanding how these logics suggest a changing relationship between economy, society and ecology. The issue of whether visions of sustainable futures for cities and whether they prioritise economic over ecological and social justice priorities or vice versa needs to be addressed in relation to these emerging logics; in particular, whether these logics contribute to a fundamental rethinking of this relationship or a continuation and the kinds of issues that may illustrate that, from, for example, whether GDP is mobilised as a primary justification for low carbon futures or, to take another example, whether security of resource flows and growth are dominant features of visions of sustainable futures.

Finally, the wider issue is whether the emerging logics contribute to a politics of transformation or continuity. This speaks to longer term and systemic implications of the forms of experimentation that are associated with these logics. It also suggests a need to understand what learning is and is not taking place from these logics and experiments and how knowledge from such processes reshapes priorities and investment. In short, what are the socio-material consequences of strategies associated with these logics, do they seek to transform networks or strengthen existing relationships and inequalities? Do they build divisible or collective planetary security?

These are issues and questions that need to be engaged with to illuminate and assess whether we are seeing the demise of sustainable cities’ debates, their narrowing or efforts to rethink and reassert them in ways which effectively engage with integrated ecological, economic and social justice concerns.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Acuto, M., 2016. Retrofitting global environmental politics. Networking and climate action in the C40. In: M. Hodson and S. Marvin, eds. Retrofitting cities: priorities, governance and experimentation. Abingdon: Routledge, 107–118.

- Andersen, H.T. and Atkinson, R., eds., 2013. The production and use of urban knowledge: European experiences. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Beatley, T., 2000. Green urbanism: learning from European cities. Washington, DC: Island Press.

- Bookchin, M., 1982. The ecology of freedom: the emergence and dissolution of hierarchy. Palo Alto, CA: Cheshire Books.

- Brand, P., 2007. Green subjection: the politics of neoliberal urban environmental management. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 31 (3), 616–632. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2427.2007.00748.x

- Brand, P. and Thomas, M.J., 2005. Urban environmentalism: global change and the mediation of local conflict. London: Routledge.

- Brenner, N., 2004. New state spaces: urban governance and the rescaling of statehood. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Brenner, N. and Schmid, C., 2015. Towards a new epistemology of the urban? City, 19 (2–3), 151–182. doi: 10.1080/13604813.2015.1014712

- Brundtland Commission. 1987. Our common future, report of the world commission on environment and development. New York: UN.

- Bulkeley, H., 2005. Reconfiguring environmental governance: towards a politics of scales and networks. Political Geography, 24, 875–902. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2005.07.002

- Bulkeley, H. and Betsill, M.M., 2003. Cities and climate change: urban sustainability and global environmental governance. New York: Routledge.

- Bulkeley, H. and Castán Broto, V., 2013. Government by experiment? Global cities and the governing of climate change. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 38, 361–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-5661.2012.00535.x

- Bulkeley, H., et al., eds., 2011. Cities and low carbon transitions. London: Routledge.

- Daly, H., 1973. Toward a steady-state economy. San Francisco, CA: W.H. Freeman.

- Davidson, K. and Gleeson, B., 2015. Interrogating urban climate leadership: toward a political ecology of the c40 network. Global Environmental Politics, 15 (4), 21–38. doi: 10.1162/GLEP_a_00321

- Davis, M., 2010. Who will build the ark? New Left Review, January/February, 29–46.

- Davoudi, S., 2012a. Resilience: a bridging concept or dead end? Planning Theory and Practice, 13 (2), 299–333. doi: 10.1080/14649357.2012.677124

- Davoudi, S., 2012b. Climate risk and security: new meanings of “the environment” in the English planning system. European Planning Studies, 20 (1), 49–69. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2011.638491

- Dobson, A. and Eckersley, R., eds., 2006. Political theory and the ecological challenge. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Edwards, G., Reid, L., and Hunter, C., 2016. Environmental justice, capabilities, and the theorization of well-being. Progress in Human Geography, 40 (6), 754–769. doi: 10.1177/0309132515620850

- Evans, J., 2011. Resilience, ecology and adaptation in the experimental city. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 36 (2), 223–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-5661.2010.00420.x

- Fainstein, S., 2016. Financialisation and justice in the city: a commentary. Urban Studies, 53 (7), 1503–1508. doi: 10.1177/0042098016630488

- Ferreri, M., 2015. The seductions of temporary urbanism. Ephemera, 15 (1), 181–191.

- Flint, J. and Raco, M., eds., 2012. The future of sustainable cities: critical reflections. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Fukuyama, F., 1992. The end of history and the last man. New York: Free Press.

- Gleeson, B., 2014. Disasters, vulnerability and resilience of cities. In: M. Hodson and S. Marvin, eds. After sustainable cities? Abingdon: Routledge, 10–23.

- Goldsmith, E., and Allen, R., 1972. A blueprint for survival. London: Ecosystems Ltd.

- Gorz, A., 1979. Ecology as politics. London: Pluto Press.

- Gorz, A., 1982. Farewell to the working class. London: Pluto Press.

- Graham, S., 2015. Life support: The political ecology of urban air. City, 19 (2–3), 192–215. doi: 10.1080/13604813.2015.1014710

- Hajer, M.A., 1995. The politics of environmental discourse: ecological modernization and the policy process. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Harvey, D., 1989. From managerialism to entrepreneurialism: the transformation in urban governance in late capitalism. Geografiska Annaler. Series B, Human Geography, 71, 3–17. doi: 10.2307/490503

- Held, D., et al., 1999. Global transformations. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Hirst, P., Thompson, G., and Bromley, S., 2009. Globalization in question. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Hodson, M. and Marvin, S., 2009. ‘Urban ecological security’: a new urban paradigm? International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 33, 193–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2427.2009.00832.x

- Hodson, M., and Marvin, S., 2010. World cities and climate change: producing urban ecological security. Maidenhead: McGraw Hill.

- Hodson, M. and Marvin, S., eds. 2014. After sustainable cities. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Hodson, M., et al., 2012. Reshaping urban infrastructure: material flow analysis and transitions analysis in an urban context. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 16 (6), 789–800. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-9290.2012.00559.x

- Hodson, M., Burrai, E., and Barlow, C., 2016. Remaking the material fabric of the city: low carbon spaces of transformation or continuity? Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 18, 128–146. doi: 10.1016/j.eist.2015.06.001

- Hoffman, M.J., 2011. Climate governance at the crossroads: experimenting with a global response after Kyoto. Oxford: OUP.

- Hollands, R.G., 2008. Will the real smart city please stand up? City, 12 (3), 303–320. doi: 10.1080/13604810802479126

- Jackson, T., 2009. Prosperity without growth: economics for a finite planet. London: Earthscan.

- Jessop, B., 2002. The future of the capitalist state. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- de Jong, M., et al., 2015. Sustainable–smart–resilient–low carbon–eco–knowledge cities; making sense of a multitude of concepts promoting sustainable urbanization. Journal of Cleaner Production, 109, 25–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.02.004

- Karvonen, A. and Van Heur, B., 2014. Urban laboratories: experiments in reworking cities. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38 (2), 379–392. doi: 10.1111/1468-2427.12075

- Kerschner, C., 2010. Economic de-growth vs. steady-state economy. Journal of Cleaner Production, 18, 544–551. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2009.10.019

- Kitchin, R., 2014. The real-time city? Big data and smart urbanism. GeoJournal, 79 (1), 1–14. doi: 10.1007/s10708-013-9516-8

- Local Agenda 21. 1992. Local agenda 21, the UN programme of action. New York: UNCED, United Nations.

- Logan, J. and Molotch, H., 1987. Urban fortunes: the political economy of place. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Luke, T., 2008. A green new deal: why green, how new, and what is the deal? Critical Policy Studies, 3 (1), 14–28. doi: 10.1080/19460170903158065

- Marvin, S., Luque-Ayala, A., and McFarlane, C., eds., 2015. Smart urbanism: utopian vision or false dawn? Abingdon: Routledge.

- Mason, P., 2015. Postcapitalism: a guide to our future. London: Penguin.

- Meadows, D.H., et al., 1972. The limits to growth: a report for the club of Rome’s project on the predicament of mankind. New York: Universe Books.

- Mol, A.P.J., 2002. Ecological modernization and the global economy. Global Environmental Politics, 2 (2), 92–115. doi: 10.1162/15263800260047844

- Newman, P., Beatley, T., and Boyer, H., 2009. Resilient cities: responding to peak oil and climate change. London: Island Press.

- O’Connor, J., 1987. The meaning of crisis. New York: Blackwell.

- Peck, J., 2012. Austerity urbanism: American cities under extreme economy. City, 16 (6), 626–655. doi: 10.1080/13604813.2012.734071

- Peck, J., Theodore, N., and Brenner, N., 2013. Neoliberal urbanism redux? International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 37 (3), 1091–1099. doi: 10.1111/1468-2427.12066

- Princen, T., 2005. The logic of sufficiency. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Raco, M. and Flint, J., 2012. Introduction: characterising the ‘new’ politics of sustainability: from managing growth to coping with crisis. In: J. Flint and M. Raco, eds. The future of sustainable cities: critical reflections. Bristol: Policy Press, 3–28.

- Rees, W.E., 1997. Is ‘sustainable city’ an oxymoron? Local Environment, 2 (2–3), 303–310. doi: 10.1080/13549839708725535

- Rogers, H., 2010. Green gone wrong: dispatches from the frontline of eco-capitalism. London: Verso.

- Sarkar, S., 1999. Eco-socialism or eco-capitalism? A critical analysis of humanity’s fundamental choices. London: Zed Books.

- Schneider, F., Kallis, G., and Martinez-Alier, J., 2010. Crisis or opportunity? Economic degrowth for social equity and ecological sustainability. Introduction to this special issue. Journal of Cleaner Production, 18, 511–518. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2010.01.014

- Scnricek, N. and Williams, A., 2015. Inventing the future. London: Verso.

- Seyfang, G. and Smith, A., 2007. Grassroots innovations for sustainable development: towards a new research and policy agenda. Environmental Politics, 16, 584–603. doi: 10.1080/09644010701419121

- Smith, A., 2014. Socially-useful production, STEPS working paper 58. Available from: http://steps-centre.org/wp-content/uploads/Socially-Useful-Production.pdf.

- Stiglitz, J., Sen, A., and Fitoussi, J-P., 2009. Report by the commission on the measurement of economic performance and social progress. Available from: http://www.insee.fr/fr/publications-et-services/dossiers_web/stiglitz/doc-commission/RAPPORT_anglais.pdf.

- Swyngedouw, E., 2009. The antinomies of the postpolitical city: in search of a democratic politics of environmental production. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 33 (3), 601–620. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2427.2009.00859.x

- Tonkiss, F., 2013. Austerity urbanism and the makeshift city. City, 17 (3), 312–324. doi: 10.1080/13604813.2013.795332

- Wallerstein, I., 1974. The modern world-system. New York: Academic Press.

- While, A., Jonas, A.E.G., and Gibbs, D.C., 2004. The environment and the entrepreneurial city: searching for the urban ‘sustainability fix’ in Leeds and Manchester. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 28 (3), 549–569. doi: 10.1111/j.0309-1317.2004.00535.x

- While, A., Jonas, A., and Gibbs, D., 2010. From sustainable development to carbon control: eco-state restructuring and the politics of regional development. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 35, 76–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-5661.2009.00362.x

- Whitehead, M., 2012. The sustainable city: an obituary? On the future form and prospect of sustainable urbanism. In: J. Flint and M. Raco, eds. Sustaining success: the new politics of sustainable urban planning. Bristol: Policy Press, 29–46.