ABSTRACT

Urban gardens are important sources of sustenance for communities with limited access to food. Hence, this study focuses on food production in gardens in the Toledo metropolitan area in Northwest Ohio. We administered surveys to 150 garden managers from November 2014 to February 2015 in our attempt to better understand how neighbourhood racial composition and poverty levels are related to staffing and voluntarism, food production and distribution, the development of infrastructure, and the adoption of sustainability practices in urban gardens. The results from 30 gardens are presented in this paper. We used Geographic Information Systems to map the gardens and overlay the map with 2010 census data so that we could conduct demographic analyses of the neighbourhoods in which the gardens were located. Though the gardens were small – two acres or less – up to 46 varieties of food were grown in a single garden. Gardens also operated on small budgets. Food from the gardens was gifted or shared with friends, family, and neighbourhood residents. Gardens in predominantly minority neighbourhoods tended to have fewer institutional partners, less garden infrastructure, and had adopted fewer sustainable practices than gardens in predominantly White neighbourhoods. Nonetheless, residents of predominantly minority and high-poverty neighbourhoods participated in garden activities and influenced garden operations. Volunteering and staffing were racialised and gendered.

1. Introduction

In recent decades, much attention has been focused on access to healthy foods in the U.S. This is of growing concern because about 15.8 million households or 12.7% of the U.S. population were classified as food insecure. Food insecurity has been shown to be more prevalent in large cities and rural areas than in the suburbs (Coleman-Jensen et al. Citation2016).Footnote1 In many cities across the country, urban residents respond to rising food insecurity by cultivating urban gardens. This paper examines how neighbourhood racial composition and poverty levels were related to staffing and voluntarism, food production and distribution, the development of infrastructure, and the adoption of sustainability practices in urban gardens in metropolitan Toledo, Ohio.

1.1. Traditional focus of food access studies

There is a robust body of literature on racial and class disparities in access to healthy foods in urban areas. However, many of these studies focus on access to supermarkets (Zenk et al. Citation2005, Bodor et al. Citation2007, Short et al. Citation2007, Raja et al. Citation2008, Ekert Citation2010, Eckert and Shetty Citation2011, Kumar et al. Citation2011, Rose Citation2011, Young et al. Citation2011, LeDoux and Vojnovic Citation2013). Researchers focus on supermarkets and grocery stores as they were significant sources of food (Rose et al. Citation2009, Ver Ploeg Citation2010a, Citation2010b).

Despite the growth in research on food access, studies of where people obtain food outside of commonly examined food outlets are still relatively few. Moreover, subsistence activities such as farming and gardening are often ignored. Consequently, analyses of the roles of urban farming and gardening in providing food for community residents are not widely studied (Taylor and Ard Citation2015). Alkon et al. (Citation2013) would concur. They found that poor urban dwellers in Oakland and Chicago utilised a variety of strategies to obtain food; many of these are understudied in the food access literature.

Increasingly, researchers are expanding the realm of food access studies and are employing a variety of conceptual frameworks to explore the topic. Two such concepts are food justice and food sovereignty. These are narrative frames that occupy critical spaces in the discourses about food production and sustainability. Food justice and food sovereignty discourses combine interest in sustainability and consumption of healthy foods with concerns about social justice, equitable access to healthy foods, and control over the production and distribution of said food. Minority-led food justice and food sovereignty movements are often rooted in environmental justice principles.Footnote2 Hence, they address inequalities in the food system by blending demands for human rights and sovereignty with the quest for social justice. Food sovereignty advocates believe that control of the means of food production, distribution, and consumption are critical elements to the empowerment and survival of Blacks and other disadvantaged groups (White Citation2010, Citation2011, Alkon and Agyeman Citation2011, Alkon and McCullen Citation2011, Passidomo Citation2013, Yakini Citation2013, Citation2010, Agyeman and McEntee Citation2014, Lindemann Citation2014, Taylor Citation2014, Citation2000, Ramírez Citation2015, Taylor and Ard Citation2015).

1.2. Urban gardens: an overlooked dimension of food access

Individuals in urban environments may experience high levels of food insecurity. Moreover, Black and Hispanic households experience greater food insecurity than White or Asian households. Families living below the poverty level are also more food insecure than those above it (Thompson Citation2005, Coleman-Jensen et al. Citation2016). Consequently, urban gardens can be important sources of locally grown, healthy foods for city and suburban residents (Taylor and Ard Citation2015).

Historically, urban gardens emerge as viable food sources during periods of economic stress, such as recessions and periods of War (Cotton Citation2009). The movement began in Detroit in 1894 when Detroit’s mayor, Hazen Pingree, unveiled a plan to allow residents to farm on 430 acres of the city’s vacant land free of cost, as a means of alleviating the food shortage. Three thousand families applied for plots, but only 945 half-acre plots were assigned. The number of families farming increased to 1546 in 1895 and 1701 in 1896. The programme, which lasted till 1901, was replicated in New York, Boston, Chicago, Minneapolis, Seattle, Duluth, and Denver (Holli Citation1969, Detroit Historical Society Citation1980, Taylor and Ard Citation2015).

During World War I, Liberty and Victory gardens were promoted as mechanisms to boost production to ensure that people had enough to eat and that a steady supply of food reached the troops (Pack Citation1919, Hynes Citation1996). To support war efforts, Toledo’s mayor, Cornell Schreiber, created a Victory Garden commission to encourage the city’s residents to grow food. The Division of Parks oversaw the programme; contests were held for the best backyard and vacant lot gardens, as well as for the best gardens planted by Boy Scout and Girl Scout troops (The Toledo City Journal Citation1919).

Interest in urban gardening waned after World War II. However, there was a resurgence of interest in gardening during the 1970s as the environmental movement grew in popularity. In recent decades, urban gardens have been used to increase the green infrastructure of cities while providing increased educational, entrepreneurial, social, and recreational spaces for residents (Saldivar-Tanaka and Krasny Citation2004). Gardens can also help cities educate the populace about sustainability and put sustainable techniques into practice (Gittleman et al. Citation2010, Otudor Citation2013).

Because of deindustrialisation, depopulation, and foreclosures, many rustbelt cities have ample vacant land that can be used for urban agricultural initiatives (Goldstein Citation2009, Lindemann Citation2014, Taylor and Ard Citation2015). Detroit, for instance, has 66,832 vacant parcels (Detroit Land Bank Authority Citation2016) and Cleveland has about 3300 acres of vacant land within its confines (Goldstein Citation2009). Toledo, too, has many vacant lots. A 2015 land survey found 14,614 vacant lots in the city (Lucas County Land Bank Citation2015). Toledo, a city in which more than a quarter of the population lives below the poverty level, has experienced an increased demand for food assistance. This has prompted lawmakers such as Congresswoman Marcy Kaptur to suggest that the city’s residents grow their own food. Invoking World I and II rhetoric, in 2009, Kaptur declared that she wanted to see 1000 Victory Gardens planted in Toledo. At the time, there were around 80 community gardens in the city (Goldstein Citation2009, Ryan Citation2009).

Today, post-industrial cities across the Midwest are transforming their urban landscapes by including urban agriculture and gardening into city planning. In Toledo, the city has included urban farms and vacant property remediation on its list of strategic economic steps (Our City in a Garden Citation2010). The city encourages the development of urban gardens as a strategy to increase the number of food outlets, and to also minimise maintenance costs of city-owned vacant lots. Urban gardens reduce the time and money local governments spend on mowing, weeding, and maintaining vacant or abandoned properties. The Lucas County Land Bank is also in support of urban gardening initiatives; consequently, it encourages residents to purchase vacant lots for a hundred dollars (Lucas County Land Bank Citation2015).

1.3. Other benefits of urban gardens

The benefits of urban gardens are well documented. They can enhance individual, household, and community food security (Corrigan Citation2011). Urban community gardens have also been shown to help residents organise neighbourhoods, strengthen social networks, exercise informal social control, reduce crime, engage youth and adults in constructive activities, develop interpersonal skills, enhance neighbourhood aesthetics, improve access to fresh produce, and increase the consumption of healthy foods (Schmelzkopf Citation1995, Allen et al. Citation2008, Krasny and Tridball Citation2009, Alaimo et al. Citation2010, Ghose and Pettygrove Citation2014). Community gardens can also be an important source of culturally desired ethnic foods. In addition, Latino gardens in New York host a variety of social, educational, religious, and cultural events. They are also the sites of voter registration drives and other civic events (Saldivar-Tanaka and Krasny Citation2004). Glover et al. (Citation2005) found that participation in community gardens facilitated civic engagement and political citizenship.

Community gardens can produce significant economic benefits, hence, scholars have examined their impact on real-estate values. In Milwaukee, the values of properties located within 250 feet of a community garden rose by $24.77 per foot. On average, each garden added about $9000 to the city’s tax revenue stream (Bremer et al. Citation2003). A similar study was conducted in New York City. Voicu and Been (Citation2008) studied the impact of 636 community gardens established between 1977 and 2000 on neighbourhoods in New York and found that they had significant positive impacts on residential property values located within 1000 feet of the gardens. This was particularly true in the poorest neighbourhoods. They estimated that the net tax benefit for the city over a 20-year period would be about $503 million or about $512,000 per garden.

Urban gardens also enhance environmental quality because they can be a source of ecosystem services. Urban gardens can help to reduce storm water runoff by decreasing the amount of impervious surface within the urban environment, and they can buffer the impacts of urban heat island effect. In addition, urban gardens provide floral and nesting resources for pollinators, facilitate seed dispersal, and serve as reservoirs of pollinators, and a refuge of ecological biodiversity for a variety of insect communities (Cotton Citation2009, Barthel et al. Citation2010, Uno et al. Citation2010, Gardiner et al. Citation2013). Studies have found that urban gardens can maintain diverse assemblages of bees and hoverflies – even though the diversity is lower than that found in rural areas (Matteson et al. Citation2008, Bates et al. Citation2011).

1.4. Potential challenges of urban gardening

However, urban gardening is not a panacea; it is one mechanism for increasing access to food, and it is a response that comes with challenges of its own. Researchers have pointed to the issue of scale of local production and food activism and the dangers of believing that thinking and acting locally is always best and most appropriate. Scholars also warn against making assumptions that local initiatives and decision-making is more rooted in social justice and ecological sustainability (Winter Citation2003, Purcell and Brown Citation2005, Born and Purcell Citation2006, Purcell Citation2006, Sonnino Citation2010, Reynolds Citation2015). For instance, in the case of urban gardening and agriculture, activists have to confront the question, how effective can urban food production be if growers are unable to increase the scale of their operations and move beyond a local focus?

Though Macias (Citation2008) contends that community-based organisations can enhance equity and justice in the food system, food justice activists and critical geographers contend that urban agricultural initiatives can reinforce class and racial privileges, deepen social inequalities, and contribute to structural racism, settler colonialism, exclusion, and other kinds of oppression (White Citation2010, Citation2011, Yakini Citation2013, Citation2010, Lyson Citation2014, Safransky Citation2014, Tornaghi Citation2014, Ramírez Citation2015, Reynolds Citation2015, Taylor and Ard Citation2015, Horst et al. Citation2017). For example, Hoover (Citation2013) found that Blacks in Philadelphia were alienated from urban gardens developed in their neighbourhoods; Ramírez (Citation2015) made a similar finding in Seattle. Researchers also argue that urban gardens and farms may be associated with gentrification and displacement (caused by rising land and housing prices) that can result in inequitable outcomes for low-income residents (Ramírez Citation2015, Horst et al. Citation2017, McClintock Citation2017).

2. Study description

This study examines the structure and operation of Toledo’s urban gardens. We do this by examining how neighbourhood racial composition and poverty levels are related to staffing and community engagement, food production and distribution, the development of institutional and agricultural infrastructure, and the adoption of sustainability practices in urban gardens. The paper will analyse differences in gardens located in predominantly White and predominantly minority neighbourhoods as well as those located in low-poverty and high-poverty neighbourhoods.

2.1. The Toledo context

This study focuses on urban gardens in and around Toledo, a city in northwest Ohio that also abuts the southern border of Michigan and the southwest corner of Lake Erie. Toledo is the fourth largest city in Ohio. The population of the 80.7 square-mile city continues to decline, going from 287,208 residents in 2010 to 279,789 in 2015. This is a 2.6% reduction in the population size. In comparison, the state of Ohio experienced a population increase of 0.7% over the same time period. Whites comprise 64.8% of the city’s population, Blacks 27.2%, Hispanics 7.4%, Asians, 1.1%, and Native Americans 0.4%. Toledo has a larger percentage of racial minorities in its population than the state as a whole. Overall, 82.7% of Ohio’s population is White, 12.7% is Black, 3.6% is Hispanic, 2.1% is Asian, and 0.1% is Native American (U.S. Census Citation2015).

Between 2011 and 2015, 85.2% of the city’s residents had at least a high school diploma and 17.4% had a bachelor’s degree or higher. The median household income in 2015 dollars was $33,687 and 27.8% of residents lived below the poverty level. Toledo residents had lower educational attainment, lower income, and a higher poverty rate than the median level for the state; 89.1% of the state’s residents had a high school diploma or higher and 26.1% had a bachelor’s degree or higher. The state’s median household income was $49,429 and the poverty rate was 14.8%. Overall, Toledo’s median household income is far below the national median and the city has a poverty rate that is more than double that of the national median. The national median household income was $53,889 and the poverty rate was 13.5% (U.S. Census Citation2015).

3. Methods

3.1. Survey methods

In 2014, Toledo had roughly 150 urban gardens. These gardens were organised and run through the Toledo Botanical Garden, a nonprofit organisation that provides resources to help develop gardening projects in the metropolitan area. The Toledo Botanical Garden collaborates with food banks, food pantries, churches, schools, nonprofits, and businesses to promote local food production through gardening (Toledo Botanical Garden Citation2016). Faith-based gardens were linked to MultiFaith GROWs which collaborates with churches and religious institutions to promote gardening for individuals of different religious backgrounds. These gardens were typically found on properties owned by religious institutions or their members (MultiFaith GROWs Citation2016). We collaborated with these two organisations to help us administer surveys to the garden managers.

We created an online survey using the Qualtrics platform. This allowed the respondent to remain anonymous and prevented them from answering the survey more than once. Qualtrics also allows the researcher to insert skip patterns, etc. needed in a survey of this sort. The survey was administered between 19 November 2014 and the end of February 2015 to 150 garden managers. The survey asked for information on the 2014 growing season. Statistical analyses were conducted in SPSS 24. This approach builds on the work of Saldivar-Tanaka and Krasny (Citation2004), Voicu and Been (Citation2008), Allen et al. (Citation2008), Alaimo et al. (Citation2010), Glover et al. (Citation2005), and Corrigan (Citation2011) who conducted garden surveys to assess the contributions of urban gardens to the well-being of city residents.

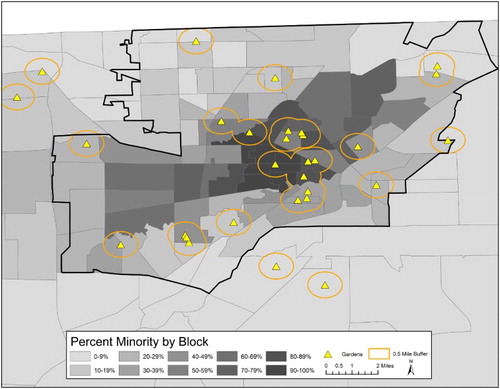

3.2. Spatial analysis

We used spatial analysis to complement survey data gathering. We used ArcGIS 10.1 to plot the locations of gardens from which we obtained survey responses. We recorded the census tracts in which each garden was located and used the latitude and longitude parameters to geocode each garden location. We created a half-mile circular buffer around each garden and calculated the number residents who were White, Black, Hispanic, Asian, and Native American in each buffer. We used the half-mile buffer to demarcate areas around each garden that neighbourhood residents could comfortably walk, bike, or drive to participate in garden activities. We overlaid the buffers with census data to show the racial characteristics of host neighbourhoods as well as the poverty levels within the buffers. For the purposes of this study, “neighbourhood” or “host neighbourhood” refers to who or what is within the half-mile buffers around the gardens.

We used the buffer technique because analysis based solely on host census tract is aspatial and assumes that people do not cross census tract boundaries to do everyday activities such as acquiring food. Researchers argue that neighbourhood boundaries are elastic and are not aligned with the contours of census tracts. This is particularly true in our data set, as several of the gardens are located on the edge of a given tract and most likely draw participants from around the garden rather than from only within one census tract (Lee et al. Citation2008, Taylor Citation2014). Researchers such as Mohai and Saha (Citation2007), Lee et al. (Citation2008), and Farrell (Citation2008) use this approach in their work.

4. Results

4.1. Garden description

A total of 45 garden managers responded to the survey, but only 31 completed enough of the instrument for them to be usable in this study. The 31 responses represent about 21% of the gardens we attempted to collect data on. This paper will analyse data from 30 urban gardens located in and around Toledo (). One garden was dropped from the sample because it was too far away from Toledo to be included in this analysis.

Figure 1. Map of Metropolitan Toledo showing location of gardens and the racial composition of the blocks around the gardens.

Twenty-six of the gardens in the sample were in the city of Toledo while four were in neighbouring suburbs. These suburban gardens were included in the analysis because they were close to the city and were affiliated the Toledo Botanical Gardens and the MultiFaith GROWs programmes. In addition, the neighbourhoods the suburban gardens were located in mirrored the racial and economic characteristics of Toledo. While three of the gardens were in neighbourhoods where the minority population was under 12% and the poverty level was less than 15%, one of the gardens was in a neighbourhood that was 72.8% minority and had a poverty level of 32.7%.

Overall, 12 (46.2%) of the city’s gardens were in predominantly minority neighbourhoods while 16 (61.5%) were in high-poverty neighbourhoods (). We grouped the gardens into four types, hence the sample consisted of 12 faith-based gardens (40%) and 18 (60%) non-faith-based gardens. Among the non-faith-based gardens, managers described nine as community gardens, five as school gardens, and four as gardens located at senior centres. While only one of the gardens at senior centres was located in a predominantly minority neighbourhood, three of the five school-yard gardens were in such neighbourhoods.

Table 1. Description of Metropolitan Toledo gardens.

The gardens were typically small; none exceed two acres. The mean garden size was 0.17 acre. Only six gardens were larger than a quarter acre; these were equally distributed between predominantly White and predominantly minority neighbourhoods. However, five of the six gardens that were more than a fourth of an acre were located in high-poverty neighbourhoods.

All the gardens in the sample collaborated with between one and seven institutions. Together, garden managers identified 58 unique institutional arrangements that resulted from collaborative ties between gardens and local organisations. As shows, half of the gardens had only one institutional partner, however, eight (26.7%) had two partners, and seven (23.3%) had three or more partners. As the number of institutional partners increased, the percentage of gardens in predominantly minority neighbourhoods having multiple partners decreased. So, while 53.3% of the gardens in predominantly minority neighbourhoods had one institutional collaborator, only 14.3% of gardens in these neighbourhoods had three or more institutional partners. The poverty level of the neighbourhood does not have the same impact on institutional partnerships. Hence, 60% of the gardens in high-poverty neighbourhoods had one institutional partner while 57.1% of them had three or more institutional collaborators.

Twenty-four of the gardens had partnerships with Toledo GROWs, eight were partners with Toledo public schools, seven collaborated with religious institutions, six were affiliated with food banks, and five were partners with MultiFaith GROWs. Other gardens had formed partnerships with a community development corporation, community centres, a university, and the public library.

The gardens operated on meagre budgets. Twenty-two garden managers said what their operational funds were for 2013. These ranged from $100 to $1100. Funds were acquired through grants, community organisations, from donations, government programmes, and from tithes and offerings. The mean operational funds were $231.36 (). The city gardens had larger budgets than the suburban gardens ($244.50 and $100, respectively). The school gardens averaged $350 in operational funds while the faith-based gardens operated on a mean budget of $131.25. The gardens in high-minority and high-poverty neighbourhoods had mean operating funds that were almost twice as large as the gardens in low-minority and low-poverty neighbourhoods. Larger gardens also had mean operational funds that were greater than smaller gardens. There was not an obvious relationship between budgets and number of institutional partners. The gardens with three or more institutional partners had mean operating budgets of $328.57 while those with only one institutional partner had operating budgets that average $236.25. It should be noted that the gardens with two institutional partners had the smallest mean budget ($128.57).

Table 2. Operational funds for Metropolitan Toledo gardens.

The gardens play important roles in repurposing urban land. Together, the 30 gardens occupied 5.02 acres of land. Fifteen (51.6%) of the gardens were created from yard space, seven (23.3%) were developed on vacant lots, five (16.7%) were now located where abandoned buildings once stood, two (6.7%) occupy a former tree lot, one was on an old farm, and another was on the grounds of a library. The land on which the gardens were developed were most likely to be owned by religious institutions. This was the case for 10 of the gardens. Thus, a third of the gardens was on land owned by faith-based institutions, four (13.3%) were owned privately, three (10%) were owned by the Department of Education, and three (10%) by the city. The state of Ohio, a land trust, catholic club, and community organisation each owned the land which gardens operate.

4.2. Race, poverty, gender, and neighbourhood differences in garden participation

The percentages of minorities living within a half-mile of the gardens ranged from 6.3% to 94.6% (see ). For the purposes of this study, host neighbourhoods wherein less than 50% of the residents were minorities were defined as having a low concentration of minorities and were referred to as predominantly White. Host neighbourhoods in which 50% or more of the residents were minorities were considered to have a high concentration of minorities and were referred to as predominantly minority. As shows, when all the garden neighbourhoods in the sample were compared, the mean percentage of minorities living within the half-mile buffers was 44.4%. However, this percentage varied quite significantly in the two types of host neighbourhoods studied. In the 17 garden neighbourhoods where minorities comprised less than half the population, on average minorities constituted 24% of the population of those neighbourhoods. But, in garden neighbourhoods where minorities made up 50% or more of the population, the average minority population in those host neighbourhoods was 71%.

Table 3. Racial composition and poverty levels in garden neighbourhoods.

The study area was also one of stark economic contrasts. The poverty levels in the neighbourhoods around the gardens ranged from 5.5% to 63.1%. We defined a low-poverty neighbourhood as one in which less than 20% of the residents live below the poverty level. A high-poverty neighbourhood was one in which 20% or more of the residents lived below the poverty level. shows that the mean poverty level in all the garden neighbourhoods was 27.5% and the difference between the poverty levels in low- and high-poverty neighbourhoods was very significant. Most of the gardens were in the poorest neighbourhoods. Seventeen of the gardens were in neighbourhoods where the average poverty level was 39.2%. The 13 gardens in low-poverty neighbourhoods were in locations where the average poverty rate was 12.2%.

There was a strong correlation between race and poverty. An average of 19.3% of the residents in low-poverty host neighbourhoods were minorities. In contrast, an average of 63.6% of the residents living in high-poverty host neighbourhoods were minorities. This was very significant (f = 62.511, p = .000).

Managers of 18 gardens provided information on the racial and gender composition of their staff; they were asked to say what percentage of their staff were from each racial group. Most of the staff in the gardens studied were White. Whites comprised a mean of 50.9% of the staff while on average Blacks comprised about 15% of garden staff (). Thirteen of the gardens had White staff and five had none. In addition, all of the staff were White in four of the gardens. Two-thirds of the gardens had no Black staff; that means only six gardens had Blacks on staff. Three of the gardens had Hispanic staff, one had Native American staff, and one had Asian staff. also shows that White staff were more likely to be found working in gardens in predominantly White neighbourhoods and Black staff in gardens in predominantly minority neighbourhoods. Hispanic and Native American staff worked in gardens in predominantly White neighbourhoods. Most of the minority staff worked in gardens in high-poverty neighbourhoods. Whites comprised the largest percentage of the staff in both low- and high-poverty neighbourhoods.

Table 4. Garden participants.

Managers also said what percentage of their staff were male or female. Overall, females comprised about 40% of the staff in the gardens and males about 32.2%. However, females were much more likely to work in gardens in predominantly minority neighbourhoods – on average females made up 49.4% and males 13.1% of the staff of such gardens. The pattern was similar in gardens in high-poverty neighbourhoods. About half the staff in these gardens were female and about 20% were male.

Garden managers also reported on the percentage of their volunteers who were from different racial and gender groups. Twenty managers described their volunteers. Only two garden managers reported that they had no White volunteers in their gardens. Whites comprised an average of 56.7% of the volunteers in the gardens, Blacks an average of 25.9%, and Hispanics made up an average of 2.8% of the volunteers. Less than 1% of the volunteers were Asians and Native Americans. Blacks volunteered in 15 gardens and Hispanics in five. While less than 10% of the volunteers in gardens in predominantly White neighbourhoods were Black, Blacks comprised about half of the volunteers in gardens in predominantly minority neighbourhoods and about 44.3% of those in gardens in high-poverty neighbourhoods. A higher percentage of Hispanics also volunteered in gardens in predominantly minority, high-poverty neighbourhoods. Only one garden manager reported having Native American volunteers and one reported having Asian volunteers.

Garden volunteering was also gendered. Managers reported that about 55.4% of their volunteers were female and about 25.6% were male. While similar percentages of females volunteered in gardens in predominantly White and predominantly minority neighbourhoods as well as in gardens in low- and high-poverty neighbourhoods, males were much more likely to volunteer in gardens in predominantly minority neighbourhoods as well as in gardens in high-poverty neighbourhoods.

Garden managers identified six different types of volunteers: the most common – community members – volunteered in 12 (40%) of the gardens. They were equally likely to volunteer in gardens in low- and high-poverty neighbourhoods. A higher percentage of gardens in predominantly White neighbourhoods reported having volunteers who were community members. Church members volunteered in 10 (33.3%) of the gardens. However, 80% of the gardens that church members volunteered in were in predominantly White neighbourhoods and 70% of those gardens were also in low-poverty neighbourhoods. Students volunteered in eight (26.7%) of the gardens. Half of the gardens that students volunteered in were in predominantly White neighbourhoods and the other half were located in predominantly minority neighbourhoods. However, 62.5% of the gardens that students volunteered in were in high-poverty neighbourhoods. Four gardens had volunteers who were friends and family, four also had volunteers from local organisations, and one had volunteers who were teachers.

More than half of the gardens (16) required participants to do general maintenance work in the gardens. This was particularly true in gardens in high-poverty neighbourhoods – 68.8% of the gardens with this requirement were located in such neighbourhoods. On the other hand, three-quarters of the gardens wherein participants tended their own plots were located in low-poverty and predominantly White neighbourhoods. Most of the gardens where participants harvest and weigh produce were also located in low-poverty and predominantly White neighbourhoods. Three of the four gardens in which participants were asked to volunteer for a specific number of hours were located in predominantly minority and high-poverty neighbourhoods.

No participation fees were required in 17 (56.7%) of the gardens. However, volunteering was expected in 11 (36.7%) of the gardens and participants were expected to donate produce in 4 (13.3%) of the gardens. All of the gardens that expected donation of produce were in predominantly White and low-poverty neighbourhoods. One of the gardens that collected annual dues was located in a neighbourhood that was 68% minority and has a 27% poverty rate. The other garden that collected annual dues was in a predominantly White neighbourhood with only 12% minority residents and had an 11% poverty rate. One garden charged fees based on the number of beds planted. This garden was in a neighbourhood where 77% of the residents were minority and 30% lived in poverty.

4.3. Neighbourhood differences in food production and distribution

Garden participants can grow a wide variety of food items in urban gardens so how did those in our study decide on what they should grow? Garden managers were asked to rank nine factors and say how important each factor was in deciding what crops to grow. If a factor was ranked 1, it was given a score of 9, 2 = 8, 3 = 7, 4 = 6, 5 = 5, 6 = 4, 7 = 3, 8 = 2, 9 = 1. Scores were tabulated to give a coaggregate score for each factor. The highest possible score was 180 and the highest possible mean was 9. shows that the most important factor taken into consideration was the cultural desirability of the crop. This factor had a total score of 121 and a mean of 6.05. The second most important factor was seeking input from community residents. This had a total score of 119 and mean of 5.95. The means for these two factors were higher in gardens in predominantly minority neighbourhoods. Gardens in high-poverty neighbourhoods also had a higher mean for seeking community input than those in low-poverty neighbourhoods.

Table 5. Deciding on what to grow in the gardens.

Customer demand was more salient in gardens in predominantly White and low-poverty neighbourhoods than it was in predominantly minority or high-poverty neighbourhoods. On the contrary, the cost of seeds was more salient in gardens in predominantly minority and high-poverty neighbourhoods than in predominantly White and low-poverty neighbourhoods.

Despite the small size of the gardens, space was the least significant factor considered when thinking about what to grow.

Garden managers for 29 of the 30 gardens reported on the types of fruits, vegetables, greens, herbs, and spices grown in their gardens. One manager reported that a variety of foods were grown without providing any further details. Sixty-six different types of crops were grown in the gardens. The number of crops grown in the gardens ranged from one crop to 46 different crops. The mean was 17.6 crops per garden. The most commonly grown food was tomato; 96.6% of the gardens grew this fruit (see ).

Table 6. Fruits, vegetables, greens, and spices grown in gardens.

Summer squash, cucumbers, and sweet pepper were also popular – 79.3% of the gardens grew these foods. Sixty-nine per cent of the gardens grew cabbage and lettuce, while 65.5% of them grew jalapeno pepper and eggplant. More than half of the gardens also grew beans, onions, broccoli, radishes, carrots, and kale.

shows how the 19 most popular garden items – crops grown in more than 40% of the gardens – varied by the different garden types. While summer squash was grown in most gardens, it was grown in 84% of Toledo’s gardens and in only half of the suburban gardens. Summer squash was also much more likely to be grown in gardens in host neighbourhoods with a low percentage of minority residents and a low percentage of residents who live below the poverty level. Eggplant, beans, carrot, and kale were also much more likely to be grown in gardens in predominantly White, low-poverty neighbourhoods. The reverse was true for collard – this crop was two to three times more likely to be grown in gardens in predominantly minority, high-poverty neighbourhoods than other gardens.

Table 7. Differences in the percentage of gardens growing fruits, vegetables, greens, and spices.

Why grow such a wide array of crops? Growing a large number of crops requires growers to utilise complex techniques to manage the high levels of diversity generated in spaces as small as the gardens in this study. Our study did not include a count of flowering plants that were grown for aesthetic, medicinal, and pest control purposes, so the overall diversity of plants in the gardens could be higher than we report if these three additional categories were taken into consideration.

The urban gardeners in metropolitan Toledo grow many crops because they are aware of the significance of biodiversity to the health of urban landscapes and they try to foster it in their gardens. They are strategic about planting crops at different times throughout the growing season so that there are plants in bloom throughout the season. This attracts a constant stream of pollinators and provides continual pollination services for both the urban gardens and the surrounding community. It also demonstrates another way in which gardens provide ecosystem services for urban areas. The desire to facilitate the pollination process helps to explain why the gardeners grow such a large variety of crops in the gardens.

Foods grown in the gardens were put to a variety of uses (see ). Food gifting and sharing was an important dimension of gardening that was practiced in the gardens studied. In most instances, crops grown were consumed by gardeners or were given to neighbourhood residents; almost two-thirds of the gardens distributed their produce this way. The practices of donating food to neighbourhood residents and sharing food with family and friends were more prevalent in gardens located in predominantly minority and high-poverty neighbourhoods than in other gardens.

Table 8. Uses for the food grown in the gardens.

Food from the gardens was reaching the most vulnerable and food insecure residents. Fourteen garden managers (46.7%) said they donated food to food banks, pantries, shelters, and soup kitchens. Only a small percentage of the gardens (10%) sell their produce. One garden manager reported that food from the garden was stolen. This garden was located in a predominantly White neighbourhood with a high poverty rate.

4.4. Garden infrastructure and sustainability practices

We asked garden managers to say what kinds of structural enhancements were in their gardens (). Fourteen (46.7%) gardens had raised beds. Nine gardens (30%) had seating areas, eight (26.7%) had toolsheds and pathways, seven (23.3%) had tables, five (16.7%) had sculptures, and four (13.3%) had grills and playgrounds. Two gardens had murals, hoop houses, and chicken coops and one had educational signage.

Table 9. Garden infrastructure and sustainability practices.

Further analysis of the distribution of these garden amenities found that gardens in predominantly minority neighbourhoods had fewer of these amenities than gardens in predominantly White neighbourhoods. Hence, all the gardens with educational signs, chicken coops, and hoop houses; 87.5% of those with toolsheds; 85.7% of those with tables; 80% of those with sculptures; three-quarters of those with grills and playgrounds; two-thirds of those with seating areas; 64.3% of the gardens with raised beds; and 62.5% of those with pathways were in predominantly White neighbourhoods.

Gardens in high-poverty neighbourhoods had more structural enhancements in them than gardens in predominantly minority neighbourhoods. Still, for five of the amenities studied, more than half of them were in low-poverty neighbourhoods. Thus, 80% of the gardens with sculptures, 62.5% of those with tool sheds and pathways, 57.1% of the ones with tables, and 55.6% of the gardens with seating areas were in neighbourhoods in which less than 20% of the residents were living below the poverty level. Three-quarters of the gardens with grills and 57.1% of the ones with raised beds were in high-poverty host neighbourhoods.

We also analysed the sustainability practices that gardens have adopted (). The most common practice reported was crop rotation; this was practiced in 12 (40%) of the gardens. Eleven (36.7%) of the gardens compost while nine (30%) had rainwater harvesting systems. Four gardens (13.3%) practice seed saving and held cooking demonstrations, while three (10%) practiced season-extension activities and had bee hives.

With the exception of cooking demonstrations, two-thirds or more of the gardens that had instituted sustainability practices were in predominantly White host neighbourhoods. Though 55.6% of the gardens with rainwater harvesting systems and half of those practicing seed saving were in low-poverty neighbourhoods, more than half of gardens engaged in the remaining sustainability practices were located in high-poverty neighbourhoods.

5. Discussion

Our study supports the findings of scholars who argue that urban gardens can improve access to fresh and healthy foods, enhance community infrastructure, and foster civic engagement among residents (Schmelzkopf Citation1995, Saldivar-Tanaka and Krasny Citation2004, Glover et al. Citation2005, Allen et al. Citation2008, Alaimo et al. Citation2010, Corrigan Citation2011, Ghose and Pettygrove Citation2014, Taylor and Ard Citation2015). It shows that food-producing gardens play vital roles in urban landscapes like Toledo. The gardens in our study occupy 5.02 acres and those operating on lands formerly occupied by abandoned buildings and vacant lots cover 1.24 acres.

In addition to reclaiming and reusing derelict land, the gardens helped to enhance the institutional infrastructure of the neighbourhoods in which they were located as they were the result of collaborations between residents, garden activists, religious institutions, schools, and community centres. Consequently, one can argue that developing urban gardens is one way of helping to rebuild part of the urban infrastructure lost to deindustrialisation (Goldstein Citation2009, Lindemann Citation2014, Taylor and Ard Citation2015).

Toledo’s urban gardening programmes was not engaging only affluent White residents, they were reaching minority and low-income residents also. Thirteen of the gardens were in neighbourhoods where 50% or more of the residents were minorities and 17 gardens were in neighbourhoods where 20% or more of the residents lived below the poverty level. Residents of all the host neighbourhoods play active roles in the operations of the gardens. They volunteered, some were on the staff of the gardens studied, neighbourhood residents also had a say in what is grown in the gardens, how the food grown was distributed, and how the gardens were operated.

This level of involvement is in accordance with the food justice model practiced in places like Detroit (White Citation2011, Taylor and Ard Citation2015), Seattle (Ramírez Citation2015), and Syracuse (Lindemann Citation2014) wherein minority and low-income residents were intimately involved with food production and distribution, consume healthy foods grown in their gardens, and were taking steps to enhance community access to fresh, healthy produce. However, Toledo’s garden programming and narratives stop short of the food sovereignty discourses evident in places like Chicago, and Detroit or espoused at events such as the Black Urban Growers conferences (White Citation2010, Citation2011, Michigan Public Radio Citation2012, Yakini Citation2013, Citation2010, Blount-Dorn Citation2014, Taylor and Ard Citation2015). This might be the case because of the strong ties to the Toledo Botanical Garden and MultiFaith GROWs; neither organisation articulate frames of black sovereignty and economic empowerment in the food system.

Our findings point to the need for scholars who study food access to focus on more than supermarkets, groceries, and convenience stores (Zenk et al. Citation2005, Citation2009, Short et al. Citation2007, Rose et al. Citation2009, Eckert and Shetty Citation2011), purchasing behaviour (Andreyeva et al. Citation2008, Citation2010, Rose Citation2011, Young et al. Citation2011, Green et al. Citation2013, LeDoux and Vojnovic Citation2013, Wang et al. Citation2007), or consumption patterns (Morland et al. Citation2006, Zenk et al. Citation2009, Budzynska et al. Citation2013).

Our research shows that urban gardeners produce, distribute, and consume food that is not driven by monetary exchanges. Studies show that individuals who participate in gardening and related educational programming were more likely to consume fruits and vegetables than those who do not (McAlesse and Rankin Citation2007). Yet, the impact of the gardens in producing healthy foods go unaccounted for in the afore-mentioned studies and may lead to an underestimation of the access to healthy foods in minority and low-income neighbourhoods (the urban neighbourhoods most often described as being underserved by full-line supermarkets and grocery stores). Ignoring the contributions of urban gardens to food access can also lead researchers to make the erroneous assumption that residents who do not have supermarkets and grocery stores in their neighbourhoods resort to eating unhealthy foods. Our study suggests that this is not always the case. It points to the agency and resilience of low-income and minority residents of Toledo who participate in neighbourhood gardens that grow about 66 varieties of foods to supplement their diets regardless of whether they have grocery stores or supermarkets in their neighbourhoods.

Our study did not assess the volume of food produced in the gardens. During preliminary information gathering sessions, managers informed us that did not have this information. However, future research on this topic should track this aspect of production to help assess how much food is being grown and distributed.

Despite the strides made in metropolitan Toledo to develop gardens in minority neighbourhoods, the gardens were racialised. White volunteers and staff predominated in most of the gardens studied. However, Blacks tended to volunteer in and staff gardens in predominantly minority neighbourhoods with high poverty rates. Hispanic volunteers and staff were most likely found in the faith-based gardens as well as in suburban gardens. The study identified areas where greater minority participation should be encouraged in the gardens. Minority participation is important because when minorities were actively engaged in gardens they help to frame the narrative, make decisions about garden operations, establish connections to neighbourhoods, and can help facilitate the goals of the gardens.

Some scholars have criticised farmers’ markets and community gardens for being White spaces – i.e. spaces that were organised, developed, and managed by Whites, and in some instances used primarily by Whites. They argue that such spaces – even when they are developed in minority neighbourhoods – are not always inviting to minorities (Alkon and McCullen Citation2011, Guthman Citation2011, Slocum Citation2011, Hoover Citation2013, Ramírez Citation2015). Hoover’s (Citation2013) study of Philadelphia identified Blacks who were alienated from the gardens being developed in their neighbourhoods. Ramírez (Citation2015) uncovered a similar dynamic in Seattle. Researchers also contend that attempts to adopt a food justice approach challenge traditional food movement approaches where White activists develop and manage food projects for minority and low-income residents. However, a food justice approach wherein minorities and low-income residents determine what will be grown, who grows the food, the uses to which food is put, and the management of neighbourhood gardens disrupts traditional food movement approaches and introduces concepts such as justice, equity, power dynamics, culture, and historical experiences into the conversation (White Citation2011, Ramírez Citation2015, Taylor and Ard Citation2015). As seen in Seattle (Ramírez Citation2015) and Detroit (White Citation2011, Taylor and Ard Citation2015), the introduction of the food justice narrative into local food movement discourses can expose tensions among food activists because some food producers are not comfortable with discussions of racism, discrimination, equity, and food sovereignty for minorities within the discussion of alternative food production.

Though there are attempts to include neighbourhood residents in garden operations and decision-making, we still suggest that more research should be conducted on Toledo’s gardens to find out more about how residents in neighbourhoods around gardens feel about the development and operation of the gardens. Moreover, work should be done to assess the extent to which predominantly White institutions like the Toledo Botanical Gardens (which partners with most of the gardens) influenced the operation of the gardens and the impact that has on residents’ perceptions of the gardens. The Toledo Botanical Garden provides an obvious benefit to the gardens. Because it supports gardens around the region, it is an umbrella organisation that can help gardens transcend a purely local focus. This can help gardens avoid the local trap that researchers warn about (Winter Citation2003, Purcell and Brown Citation2005, Born and Purcell Citation2006, Purcell Citation2006, Sonnino Citation2010, Reynolds Citation2015).

The regional focus is evident in some of the events that the Botanical Garden organises with the gardens. As mentioned before, Toledo’s gardeners cultivate a large variety crops in their gardens. The high levels of crop diversity in the gardens are facilitated through collaboration between gardeners and their institutional partners. Each year Toledo GROWs (the Toledo Botanical Garden) promote seed swap events. At the annual swap, gardeners and farmers from around the region gather before the growing season begins to exchange seeds with each other. This allows each gardener to obtain a wide variety of organic seeds. The event also provides gardeners with growing tips and tools. Through their involvement in these networks, gardeners in our survey obtain knowledge and resources to improve their gardens. This includes maximising crop variety to enhance pollination and provide other ecosystem services. Our results support the findings of other researchers who report that urban gardens increase biodiversity and are reservoirs of pollinators (Matteson et al. Citation2008, Cotton Citation2009, Barthel et al. Citation2010, Uno et al. Citation2010, Bates et al. Citation2011, Gardiner et al. Citation2013).

The garden spaces were gendered. Females were more likely to volunteer in the gardens than males. Females were also more likely to be on the staff of the gardens than males. Greater effort should be made to understand if there were barriers to male participation and what can be done to overcome them.

Across the board, the gardens were operating on shoe-string budgets. Though three gardens were engaged in season-extension activities, and nine gardens had instituted sustainability practices, the limited budgets constrain the activities the gardens can engage in. Such activities could include value-added initiatives (that could generate cash) such as processing, packaging, canning, bottling, and pickling of foods grown in the gardens. Though seven gardens conducted garden tours, four held workshops and harvest festivals, three hosted private social events, two gardens hosted farmers’ markets and cultural events, and one showed movies, it is unclear how much revenue these activities generate for the gardens.

6. Conclusions

Metropolitan Toledo’s gardening programme has the support of politicians, the Toledo Botanical Garden, and influential church groups. Gardens were being established in minority and low-income neighbourhoods but the gardens in predominantly minority neighbourhoods lack the infrastructure found in gardens in predominantly White neighbourhoods. Volunteering and staffing was racialised and gendered. Our findings suggest that greater efforts should be made to understand if and how more minorities and males can be incorporated into garden activities.

More funds are needed to help the gardens achieve their goals. Additional funding will also be needed for gardens to expand in size and offer a greater range of services. Land tenure will be an issue that the gardens will need to confront in the future. Few of the gardeners in our study own the land on which they currently garden. For the long-term stability of the gardens, it might behove gardeners to explore more stable land tenure arrangements such as purchasing land from the land bank.

More work needs to be done to understand the power dynamics inherent in the institutional partnerships that buttress the city and suburban gardening programme. Given the concerns expressed in other cities about the development and operation of gardens in minority and low-income communities, it would helpful to examine how the partnerships function and the impact they have on residents’ participation in and connectedness to garden activities.

This analysis of metropolitan Toledo’s gardens highlights the need to document more fully the ways in which neighbourhood demographic characteristics are related to garden operations, resources, and infrastructure. There is also a need to understand more fully the production in the gardens, the extent to which the gardens reduce food insecurity, and general contributions that gardens make to activities such as the repurposing of derelict land, the institution of sustainability practices, and the enhancement of biodiversity and other ecosystem services. The analysis also points to the need to view urban gardens as critical components of the food system.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Toledo Botanical Garden and MultiFaith GROWs for distributing our survey and connecting us with gardens across the Toledo metropolitan area. We would also like to thank Brad Kasberg in SEAS’ Environmental Spatial Analysis lab for helping to create the map.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Dorceta E. Taylor http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2847-0779

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) identifies two dimensions of food insecurity. That is, food insecurity occurs when there is a reduction in the quality, variety, or desirability of meals consumed. Food insecurity also arises when there are disruptions in eating patterns and food intake is reduced (USDA Economic Research Service Citation2016).

2 Environmental justice identifies, describes, and analyses racist and discriminatory acts that result in racial inequities in the environmental realm. Proponents of the environmental justice thesis assert that blacks and other people of colour are subject to racist and discriminatory acts, policies, practices, and decision-making that result in racial inequities. Hence, environmental justice seeks redress for perceived unfair acts (Taylor Citation2000, Citation2014).

References

- Agyeman, J. and McEntee, J., 2014. Moving the field of food justice forward through the lens of urban political ecology. Geography Compass, 8 (3), 211–220. doi: 10.1111/gec3.12122

- Alaimo, K., Reischl, T.M., and Allen, J.O., 2010. Community gardening, neighborhood meetings, and social capital. Journal of Community Psychology, 38, 1–18.

- Alkon, A.H. and Agyeman, J., 2011. Cultivating food justice: race, class, and sustainability. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Alkon, A.H. and McCullen, C.G., 2011. Whiteness and farmers markets: performances, perpetuations … contestations?. Antipode, 43 (4), 937–959. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8330.2010.00818.x

- Alkon, A.H., Block, D., Moore, K., Gillis, C., DiNuccio, N., and Chavez, N., 2013. Foodways of the urban poor. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 48, 126–135.

- Allen, J.O., Alaimo, K., Elam, D., and Perry, E., 2008. Growing vegetables and values: benefits of neighborhood based community gardens for youth development and nutrition. Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition, 3 (4), 418–430. doi: 10.1080/19320240802529169

- Andreyeva, T., Blumenthal, D.M., Schwartz, M.B., Long, M.W., and Brownwell, K.D., 2008. Availability and prices of foods across stores and neighborhoods: the case of New Haven, Connecticut. Health Affairs, 27 (5), 1381–1388. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.5.1381

- Andreyeva, T., Long, M.W., and Brownwell, K.D., 2010. The impact of food prices on consumption: a systematic review of research on the price elasticity of demand for food. American Journal of Public Health, 100 (2), 216–222. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.151415

- Barthel, S., Folke, C., and Colding, J., 2010. Social-ecological memory in urban gardens—retaining the capacity for management of ecosystem services. Global Environmental Change, 20 (2), 255–265. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2010.01.001

- Bates, A.J., Sadler, J.P., Fairbrass, A.J., Falk, S.J., Hale, J.D., Matthews, T.J., 2011. Changing bee and hoverfly pollinator assemblages along an urban-rural gradient. PLOS One. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0023459 [Accessed 5 Dec 2016].

- Blount-Dorn, Kibibi, 2014. Black farmers and urban growers promote power and sovereignty. Michigan Citizen. 12 October. p. 8.

- Bodor, N., Rose, D., Farley, T., Swalm, C., and Scott, S., 2007. Neighborhood fruit and vegetable availability and consumption: the role of small food stores in an urban environment. Public Health Nutrition, 11 (4), 413–420.

- Born, B. and Purcell, M., 2006. Avoiding the local trap: scale and food systems in planning research. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 26 (2), 195–207. doi: 10.1177/0739456X06291389

- Bremer, A., Jenkins, K., and Kanter, D., 2003. Community gardens in Milwaukee: procedures for their long-term stability & their import to the city. Milwaukee: University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. Department of Urban Planning.

- Budzynska, K., West, P., Savoy-Moore, R.T., Lindsey, D., Winter, M., and Newby, P.K., 2013. A food desert in Detroit: associations with food shopping and eating behaviours, dietary intakes, and obesity. Public Health Nutrition, 16 (12), 2114–2123. doi: 10.1017/S1368980013000967

- Coleman-Jensen, A., Rabbit, M.P., Gregory, C.A., and Singh, A., 2016. Household food security in the United States in 2015. Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service . Available from: https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/err215/err-215.pdf [Accessed 11 Dec 2016].

- Corrigan, M., 2011. Growing what you eat: developing community gardens in Baltimore, Maryland. Applied Geography, 31, 1232–1241. doi: 10.1016/j.apgeog.2011.01.017

- Cotton, J.A., 2009. A study of beetle biodiversity in the forests, gardens, and vacant lots of Detroit. MS Thesis. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, School of Natural Resources and Environment.

- Detroit Historical Society, 1980. Pingree “s potato patches: a study of self-help during the depression of the 1890”s. Detroit in Perspective, 4 (2), 219–227.

- Detroit Land Bank Authority, 2016. Building Detroit: Inventory Department. October. Detroit: Detroit Land Bank Authority. Available from: http://www.buildingdetroit.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/10.15.16-CCQReport.pdf [Accessed 4 Dec 2016].

- Eckert, J., 2010. Food systems, planning and quantifying access: how urban planning can strengthen Toledo’s local food system. Master’s Thesis. University of Toledo, Department of Geography.

- Eckert, J. and Shetty, S., 2011. Food systems, planning and quantifying access. Using GIS to plan for food retail. Applied Geography, 31 (4), 1216–1223. doi: 10.1016/j.apgeog.2011.01.011

- Farrell, C.R., 2008. Bifurcation, fragmentation or integration? The racial and geographical structure of U.S. metropolitan segregation, 1990-2000. Urban Studies Journal, 45 (3), 467–499. doi: 10.1177/0042098007087332

- Gardiner, M.M., Burkman, C.E., and Prajzner, S.P., 2013. The value of urban vacant land to support arthropod biodiversity and ecosystem services. Environmental Entomology, 42 (6), 1123–1136. doi: 10.1603/EN12275

- Ghose, R. and Pettygrove, M., 2014. Actors and networks in urban community garden development. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 53 (May), 93–103.

- Gittleman, M., Librizzi, L., and Stone, E., 2010. Community garden survey. New York City. Results 2009/2010. Grow New York. New York. Available from: http://www.grownyc.org/files/GrowNYC_CommunityGardenReport.pdf [Accessed 10 Oct 2017].

- Glover, T., Shinew, K., and Parry, C., 2005. Association, sociability, and civic culture: the democratic effect of community gardening. Leisure Sciences, 27 (1), 75–92. doi: 10.1080/01490400590886060

- Goldstein, N., 2009. Vacant lots sprout urban farms. BioCycle (October). Available from: http://www.biocycle.net/images/art/0910/bc0910_24_30.pdf [Accessed 4 Dec 2016].

- Green, R., Cornelsen, L., Dangour, A.D., Turner, R., Shankar, B., Mazzocchi, M., and Smith, R.D., 2013. The effect of rising food prices on food consumption: systematic review with meta-regression. BMJ. 346. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f3703 [Accessed 10 May 2017].

- Guthman, J., 2011. “If they only knew”: the unbearable whiteness of alternative food. In: A. Alkon and J. Agyeman, eds. Cultivating food justice: race, class, and sustainability. Cambridge: MIT Press, 263–281.

- Holli, M.G., 1969. Reform in Detroit – Hazen S. Pingree and urban politics. New York: Oxford University Press, 70–73.

- Hoover, B., 2013. White spaces in Black and Latino places: urban agriculture and food sovereignty. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development, 3 (4). ISSN: 2152-0801 online. Available from: https://doi.org/10.5304/jafscd.2013.034.014 [Accessed 27 Dec 2016].

- Horst, M., McClintock, N., and Hoey, L., 2017. The intersection of planning, urban agriculture, and food justice: a review of the literature. Journal of the American Planning Association, 83 (3), 277–295. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/01944363.2017.1322914 [Accessed 9 Oct 2017].

- Hynes, H.P., 1996. A patch of Eden: America’s inner-city gardeners. Vermont: Chelsea Green Publishing Company.

- Krasny, M.E. and Tridball, K.G., 2009. Community gardens as contexts for science, stewardship, and civic action learning. Cities and the Environment, 2 (1), Article 8. 18pp. Available from: http://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1037&context=cate [Accessed 10 June 2017]. doi: 10.15365/cate.2182009

- Kumar, S., Quinn, S.C., Kriska, A.M., and Thomas, S.B., 2011. “Food is directed to the area”: African Americans’ perceptions of the neighborhood nutrition environment in Pittsburgh. Health and Place, 17, 370–378. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.11.017

- LeDoux, T.F. and Vojnovic, I., 2013. Going outside the neighborhood: the shopping patterns and adaptations of disadvantaged consumers living in the lower eastside neighborhoods of Detroit, Michigan. Health & Place, 19, 1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.09.010

- Lee, B.A., Reardon, S.F., Firebaugh, G., Farrell, C.R., Matthews, S.A., and O’Sullivan, D., 2008. Beyond the census tract: patterns and determinants of racial segregation at multiple geographic scales. American Sociological Review, 73 (October), 766–791. doi: 10.1177/000312240807300504

- Lindemann, J. (2014). The intersection of race and food in the rust belt: how food justice challenges the urban planning paradigm. Master of Science Thesis. Ithaca: Cornell University, Department of Sociology.

- Lucas County Land Bank, 2015. The Toledo survey: community progress report. Toledo: Lucas County Land Bank. Available from: http://co.lucas.oh.us/DocumentCenter/View/54858 [Accessed 4 Dec 2016].

- Lyson, H.C., 2014. Social structural location and vocabularies of participation: fostering a collective identity in urban agriculture activism. Rural Sociology, 79 (3, September), 310–335. doi: 10.1111/ruso.12041

- Macias, T., 2008. Working toward a just, equitable, and local food system: The social impact of community-based agriculture. Social Science Quarterly, 89 (5), 1086–1011. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6237.2008.00566.x

- Matteson, J.S., Ascher, J.S., and Langellotto, G.A., 2008. Bee richness and abundance in New York city urban gardens. Annals of the Entomological Society of America, 101 (1), 140–150. doi: 10.1603/0013-8746(2008)101[140:BRAAIN]2.0.CO;2

- McAleese, J.D. and Rankin, L.L., 2007. Garden-based nutrition education affects fruit and vegetable consumption in sixth-grade adolescents. Journal of the American Diabetic Association, 107 (4), 662–665. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.01.015

- McClintock, N., 2017. Cultivating (a) sustainability capital: urban agriculture, eco-gentrification, and the uneven valorization of social reproduction. Urban Studies and Planning Faculty Publications and Presentations. 168. Available from: http://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/usp_fac/168 [Accessed 5 Oct 2017].

- Michigan Public Radio. 2012. Black farming power. MichiganNow.org. Available from: http://www.michigannow.org/2012/05/15/black-farming-power/ [Accessed 15 Oct 2017].

- Mohai, P. and Saha, R., 2007. Racial inequality in the distribution of hazardous waste: a national-level assessment. Social Problems, 54 (3), 343–370. doi: 10.1525/sp.2007.54.3.343

- Morland, K., Diez Roux, A.V., and Wing, S., 2006. Supermarkets, other food stores, and obesity: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. American Journal of Preventative Medicine, 30 (4), 333–339. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.11.003

- MultiFaith GROWs, 2016. MultiFaith GROWs. Available from: http://gardens.multifaithjourneys.org/ [Accessed 27 Dec 2016].

- Otudor, I., 2013. Sustainable techniques in community gardens and urban farms. In: Examining disparities in food access and enhancing the food security of underserved populations in Michigan. University of Michigan, School of Natural Resources and Environment, pp. 266–297. Available from: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015089709342;view=1up;seq=1 [Accessed 13 Oct 2017].

- Our City in a Garden, 2010. Growing produce, harvesting rewards. Toledo, OH: Our City in a Garden. 43 pp.

- Pack, C.L., 1919. Victory gardens feed the hungry: the needs of peace demand the increased production of food in America’s victory gardens. Washington, DC: National War Garden Commission. 32 pp.

- Passidomo, C.M., 2013. Right to (feed) the city: race, food sovereignty, and food justice activism in post-Hurricane Katrina New Orleans. Ph.D. dissertation. Athens, GA: University of Georgia.

- Purcell, M., 2006. Urban democracy and the local trap. Urban Studies, 43 (11, October), 1921–1941. doi: 10.1080/00420980600897826

- Purcell, M. and Brown, J.C., 2005. Against the local trap: scale and the study of environment and development. Progress in Development Studies, 5 (4), 279–297. doi: 10.1191/1464993405ps122oa

- Raja, S., Ma, C., and Yadav, P., 2008. Beyond food deserts: measuring and mapping racial disparities in neighborhood food environments. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 27 (4), 469–482. doi: 10.1177/0739456X08317461

- Ramírez, M.M., 2015. The elusive inclusive: black food geographies and racialized food spaces. Antipode, 47 (3), 748-769. doi: 10.1111/anti.12131

- Reynolds, K., 2015. Disparity despite diversity: social injustice in New York city’s urban agriculture system. Antipode, 47 (1), 240–259. doi: 10.1111/anti.12098

- Rose, D.J., 2011. Captive audience? Strategies for acquiring food in two Detroit neighborhoods. Qualitative Health Research, 21 (5), 642–651. doi: 10.1177/1049732310387159

- Rose, D.D., Bodor, J.N., Swalm, C.M., Rice, J.C., Farley, T.A., Hutchinson, P.L., 2009. Food deserts in New Orleans? Illustrations of urban food access and implications for policy. Paper prepared for the University of Michigan National Poverty Center and the USDA Economic Research Service Research, Ann Arbor, MI.

- Ryan, C., 2009. Kaptur cultivates Victory Garden for donation to Toledo area food banks. The Toledo Blade. 10 May. Available from: http://www.toledoblade.com/local/2009/05/10/Kaptur-cultivates-Victory-Garden-for-donations-to-Toledo-area-food-banks.html [Accessed 4 Dec 2016].

- Safransky, S., 2014. Greening the urban frontier: race, property, and resettlement in Detroit. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 56, 237–248.

- Saldivar-Tanaka, L. and Krasny, M.L., 2004. Culturing community development, neighborhood open space, and civic agriculture: the case of Latino community gardens in New York city. Agriculture and Human Values, 21, 399–412. doi: 10.1023/B:AHUM.0000047207.57128.a5

- Schmelzkopf, K., 1995. Urban community gardens as contested space. Geographical Review, 85 (3), 364–381. doi: 10.2307/215279

- Short, A., Guthman, J., and Raskin, S., 2007. Food deserts, oases, or mirages? Journal of Planning Education and Research, 26, 352–364. doi: 10.1177/0739456X06297795

- Slocum, R., 2011. Race in the study of food. Progress in Human Geography, 35 (3), 303–327. doi: 10.1177/0309132510378335

- Sonnino, R., 2010. Escaping the local trap: insights on re-localization from school food reform. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 12 (1): 23–40. doi: 10.1080/15239080903220120

- Taylor, D.E., 2000. The rise of the environmental justice paradigm: injustice framing and the social construction of environmental discourses. American Behavioral Scientist, 43 (4), 508–580.

- Taylor, D.E., 2014. Toxic communities: environmental racism, industrial pollution, and residential mobility. New York: New York University Press, 41–43.

- Taylor, D.E. and Ard, K.J., 2015. Food availability and the food desert frame in Detroit: an overview of the city’s food system. Environmental Practice, 17, 102–133. doi: 10.1017/S1466046614000544

- Thompson T.G., 2005. Dietary guidelines for Americans, 2005. 6th ed. Darby, PA: Diane Publishing Co.

- Toledo Botanical Garden, 2016. Toledo GROWs. Available from: http://www.toledogarden.org/toledogrows/ [Accessed 27 Dec 2016].

- The Toledo City Journal, 1919. More lots needed for Victory Gardens. The Toledo City Journal. 4 (April): 285.

- Tornaghi, C., 2014. Critical geography of urban agriculture. Progress in Human Geography, 38 (4), 551–567. doi: 10.1177/0309132513512542

- Uno, S., Cotton, J. and Philpott, S.M., 2010. Diversity, abundance, and species composition of ants in urban green spaces. Urban Ecosystems, 13, 425–441. doi: 10.1007/s11252-010-0136-5

- U.S. Census, 2015. Welcome to QuickFacts: Toledo city, Ohio. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Commerce. Census Bureau. Available from: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/table/PST045215/3977000/accessible [Accessed 11 Dec 2016].

- U.S. Department of Agriculture Economic Resource Service, 2016. Definitions of food security. Available from: https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/definitions-of-food-security.aspx [Accessed 11 Dec 2016].

- Ver Ploeg, M., 2010a. Access to affordable, nutritious food is limited in “food deserts”. Amber Waves 8(March 1). Available from: http://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2010-march/access-to-affordable,-nutritious-foodis-limited-in-%E2%80%9Cfood-deserts%E2%80%9D.aspx#.Usf9nGeA2Uk [Accessed 2 Dec 2016].

- Ver Ploeg, M., 2010b. Food environment, food store access, consumer behavior, and diet. Choices Magazine. Available from: http://www.choicesmagazine.org/magazine/article.php?article=137 [Accessed 2 Dec 2016].

- Voicu, I. and Been, V., 2008. The effect of community gardens on neighboring property values. Real Estate Economics, 36 (2), 241–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6229.2008.00213.x

- Wang, M.C., MacLeod, K.E., Steadman, C., Williams, L., Bowie, S.L., Herd, D., Luluquisen, M., and Woo, M., 2007. Is the opening of a neighborhood full-service grocery store followed by a change in the food behavior of residents?. Journal of Hunger and Environmental Nutrition, 2, 3–18. doi: 10.1080/19320240802077789

- White, M.M., 2010. Shouldering responsibility for the delivery of human rights: a case study of the D-Town farmers of Detroit. Race/Ethnicity, 3 (2), 189–211.

- White, M.M., 2011. D-Town farm: how African American resistance to food insecurity is transforming Detroit. Environmental Practice, 30 (4), 406–417. doi: 10.1017/S1466046611000408

- Winter, M., 2003. Embeddedness, the new food economy and defensive localism. Journal of Rural Studies, 19 (1), 23–32. doi: 10.1016/S0743-0167(02)00053-0

- Yakini, M., 2010. Undoing racism in the Detroit food system. Michigan Citizen. 2 November.

- Yakini, M., 2013. Support DBCFSN co-op grocery store. Michigan Citizen. 30 June. p. A10.

- Young, C., Karpyn, A., Uy, N., Wich, K., and Glyn, J., 2011. Farmers’ markets in low income communities: impact of community environment, food programs and public policy. Community Development, 42 (2), 208–220. doi: 10.1080/15575330.2010.551663

- Zenk, S.N., Lachance, L.L, Schultz, A.J., Mentz, G., Kannan, S., and Ridella, W., 2009. Neighborhood retail food environment and fruit and vegetable intake in multiethnic urban adults. American Journal of Health Promotion, 23, 255–264. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.071204127

- Zenk, S.N., Schultz, A.J., Israel, B.A., James, S.A., Bao, S., and Wilson, M.L., 2005. Neighborhood racial composition, neighborhood poverty, and the spatial accessibility of supermarkets in metropolitan Detroit. American Journal of Public Health, 95 (4), 660–667. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.042150