ABSTRACT

Resourcefulness, a community’s capacity to engage with their local resource base, is essential in contributing to resilience, the potential to adapt to external challenges and shocks. Resourcefulness and social innovation have some overlapping qualities, however, the academic connection between the two concepts is yet to be explored. Social innovations include new practices, ideas, and initiatives that meet societal needs and contribute to social change and empowerment. Through in-depth interviews and participant observation, this study researches conditions and processes of resourcefulness in facilitating social innovation in rural, peri-urban, and urban community gardens in the North of the Netherlands. Comparing differing contexts, five main enablers for altering social relations and community empowerment have been identified: (1) clear goals and motivations; (2) diversity in garden resources; (3) experimental knowledge processes; (4) strong internal support and recognition; and (5) place-based practices. Above all, this research stresses the importance of defining resourcefulness as a process and foregrounding the place-based contextual nature of innovative collective food system practices.

1. Introduction

The past decades have seen rapidly changing rural and urban environments, due to processes of urbanisation and globalisation. In the midst of global changes, many Western European contexts are increasingly focusing on local citizen initiatives, which attempt to reconfigure the built environment and take up social responsibilities, to meet community needs (Boonstra Citation2015; Meijer Citation2018). These grassroots activities, initiated by citizens, entrepreneurs, or other local stakeholders, have been framed as forms of community-led planning, contrasting government-led spatial planning and characterised by place-based, informal practices (Meijer Citation2018).

Local citizen action could be viewed through the lens of social innovations, which is defined as community action that constructs new rules and social relations to meet societal needs and leads to social change and empowerment (Bock Citation2012; Moulaert et al. Citation2005). Social innovations’ focus on changing relationships redefines the potential role of citizens in society, as well as their capacity to improve their living environment based on local needs. International institutions, such as the OECD (Citation2017) and the European Commission (Citation2013) further endorse the benefits of social innovation, in supporting adaptability to changing societal contexts and trends. While social innovation is relevant to both urban (Moulaert et al. Citation2005) and rural (Neumeier Citation2012) contexts, the social issues addressed and accompanying means of community action and organisation, differ, and must be taken into account. Bock (Citation2016) stresses the need to understand these specific contexts and conditions that stimulate local action for social innovation.

Theories on resourcefulness provide a pioneering perspective to investigate practices that enable social innovation. Resourcefulness has been defined as a community’s capacity to engage with their local resource base as a means to address the unequal distribution of resources (Franklin Citation2018). Moreover, resourcefulness privileges civic engagement and traditional knowledge exchange, and, similar to social innovation, attempts to empower local communities (MacKinnon and Derickson Citation2012). Identifying assorted conditions and processes in which resourcefulness operates would greatly benefit planning and policy research. Furthermore, despite their overlapping qualities and socially relevant potential, the academic connection between social innovation and resourcefulness has not yet been made.

Through characteristics described above, community gardens have the potential to act as social innovations and provide insight into aspects and conditions of resourcefulness. Namely, citizen collectives that typically initiate community gardens attempt to create new rules and social relations around food system practices and the roles of citizens, involving and educating their local community in food production, while also providing access to fresh and healthy food (Ilieva Citation2016). Community gardens themselves contribute environmental, social, economic, and health benefits, for example enhancing the health of participants, supplying ecosystems services, boosting community food security, and enriching community cohesion (Artmann and Sartison Citation2018; Porter Citation2018; Santo, Palmer, and Kim Citation2016). More than meeting this range of needs, such gardens are unique in that they provide a nexus of different functions in one venue, also bringing together citizens with different motivations, thus being a place for a range relationship building (Veen Citation2015). Such gardens are also a collectively cultivated space (of municipal officials, policy-makers, and citizens), necessitating the pooling of local resources, knowledge, and community support for their survival. Community gardens, however, are not without critique, whether they are argued to be tools by the state to pass on responsibilities to civil society (Rosol Citation2012), or operating within both radical and neoliberal spheres (McClintock Citation2014). On a more local level, community gardens have been controversial in unintentionally leading to social exclusion, for example, when non-residents lead projects in other low-income or primarily Black/Latino neighbourhoods (Kato Citation2013; Poulsen Citation2017). Furthermore, while gardens are a meeting place, it is often for those with similar values and interests, thus communities within the space tend to work along one another without forming a cohesive community (Veen Citation2015). These examples highlight the power hierarchies and internal divisions that can exist in such spaces, which must also be examined critically (Tornaghi Citation2014).

Through shaping the built environment, community gardens are praised as a tool for community empowerment, in terms of providing opportunities as a social gathering place (Glover Citation2004; Kingsley and Townsend Citation2006) and strengthening community cohesion (Firth, Maye, and Pearson Citation2011), therefore provide the ideal venue to explore the connections between theories of social innovation and resourcefulness. Additionally, most studies examine community gardens in an urban context, potentially due to the prevalence of accessibility of resources and organisational capacity (Armstrong Citation2000). However, this research includes both rural and peri-urban agriculture. A broader focus of community gardens potentially introduces creative strategies and relations to fit the needs of society, at different social and spatial scales.

Exploring social innovations in community gardens, not only highlights their potential role in empowering communities, but also how changing relations between community actors could result in developing a place-based, socially and environmentally equitable food system; we refer here to the rapidly increasing literature on this topic (see: Carolan Citation2017; Firth, Maye, and Pearson Citation2011; Kneafsey et al. Citation2017; Opitz et al. Citation2015; Poulsen Citation2017; Pudup Citation2007; Tornaghi Citation2017; Veen Citation2015).

This research aims to identify conditions and processes of resourcefulness used to facilitate social innovation in urban, peri-urban, and rural community gardens. Gardens provide a physical venue to explore these theories empirically, providing insight into the differentiated social and environmental capacities and how communities access them. By an explorative comparison of three gardens in various settings in the North of the Netherlands, contextual differences will be highlighted, which will result in place-based recommendations grounded in contextualised community practices.

This paper will, firstly, elaborate on theories of social innovation and resourcefulness, and the added value of connecting the two. Secondly, this paper will give a short overview of each of the three cases and the methods used to research them. Thirdly, the results will be explained, of each case in-depth. Lastly, this paper will discuss the results in the context of debates on place-based social innovation and end with conclusions and recommendations for further research.

2. Theoretical framework

2.1. Social innovation

Social innovation is a broad term that refers to ideas and initiatives that, not only, highlight opportunities for social change, but also novel methods of altering small and potentially large-scale relations. Historically, social innovation was envisioned as a venue of collective action, ultimately transforming top-down structures into participatory configurations (Moulaert, MacCallum, and Hillier Citation2013, citing Chambon et al. 1982). Furthermore, social innovation has been approached from a multi-dimensional and multi-sector perspective, through its appearance in fields of business and economics, in terms of strategic behaviour, as well as fine arts, in regards to the creativity potential in the topic (Moulaert et al. Citation2005). This paper will, however, align with the integrated approach proposed by Moulaert et al. (Citation2005), which emphasises how the “social change potential of new institutions and practices promote responsible and sustainable development of communities” (p. 1976).

Bock (Citation2012) identifies three main qualities of social innovation: firstly social innovation occurs in a distinct social context, thus, must somehow interact with that context; secondly because innovations are based on social circumstances, they promote socially responsible behaviour that is relevant to their societal context through some sort of participatory means; and finally, social innovation is pertinent to community development and has potential to result in empowered communities through inclusive collective action (Bock Citation2012). Similar to the definition proposed by Bock (Citation2012), Moulaert et al. (Citation2005) discuss three main dimensions of the concept: 1) meeting basic needs that are otherwise not addressed; 2) reconstructing social relations; and 3) empowering community, giving them capacity to meet said needs and potentiating social change. Social innovation can be further divided into micro (relations between individuals), meso, and macro (relations between social class and groups) levels, where, “opportunity spaces at micro scales may make creative strategies possible at macro scales”, thus all scales are necessary in social innovations (Baker and Mehmood Citation2015; Moulaert, MacCallum, and Hillier Citation2013, 17).

While these are the broader conditions or components of social innovation, Baker and Mehmood (Citation2015) identify two specific catalysts: meeting societal needs and times of crises. When faced with the spatial-material impact, as a result of a crisis, local communities are motivated to act and contribute to social change in their direct environment, further highlighting the contextual importance for motivating action (Baker and Mehmood Citation2015; Bock Citation2012).

The place-based material relevance of social innovation could play a significant role in promoting social and ecological objectives in sustainable development (Mehmood and Parra Citation2013). In comparison to more top-down approaches, social innovations, or “grassroots innovations” operate on a community level, work towards environmental sustainability solutions for civil society as well as deliver intrinsic benefits to initiate more systemic change (Seygang and Smith Citation2007). Collaboration with (national level) top-down institutions is also emphasised, in order for social innovations to achieve greater impact and possible replications across various spatial scales (Baker and Mehmood Citation2012; Seyfang and Haxeltine Citation2012). However, scaling size does not necessarily translate to scaling impact, and, in a development context, scaling up could result in for-profit organisations exploiting vulnerable communities, thus does not apply to all social innovations (Matthews Citation2017). Furthermore, for many, social innovation has become a “buzzword” that has lost its value in facilitating change, and thus, also its legitimacy (Bock Citation2012; Pol and Ville Citation2009). If the term remains abstract and disconnected from practice, it not only weakens the concept, but could have potentially detrimental impacts on the vulnerable groups it is meant to assist (Grimm et al. Citation2013). Grimm et al. (Citation2013), however, highlight the importance of the local context and multi-level governance for overcoming these challenges, which will be further addressed in this article.

Prioritising place-based projects, social innovation provides opportunities for fostering sustainable development on a local and global level, for example, by addressing environmental and social concerns through food system developments (Kirwan et al. Citation2013; Maye and Duncan Citation2017). Community gardens, thus, are a relevant representation through their capacity to stimulate social cohesion (Firth, Maye, and Pearson Citation2011), improve rainwater drainage (Wortman and Lovell Citation2013), filter air pollution (Taylor and Lovell Citation2014), provide fresh food access (Corrigan Citation2011; Kortright and Wakefield Citation2011), and support workforce training opportunities (Pudup Citation2007; Vitiello and Wolf-Powers Citation2014). Furthermore, positioning community gardens in planning theory and disciplines adds a place-based applicability for such bottom-up projects.

2.2. Resourcefulness

In order to withstand social, economic, or environmental obstacles, a degree of resourcefulness is needed by communities. Resourcefulness refers to communities’ capacities to access material and non-material resources (MacKinnon and Derickson Citation2012).

Resourcefulness, a relatively new and promising concept, has gained attention through its relationship with resilience, which has been defined as the quality of being able to adapt to challenges or “stability of a system against interference” (Lang Citation2010, 16). Despite its rising popularity, resilience remains a contested concept with multiple meanings. In tracing the origin of the term resilience, Walker and Cooper (Citation2011) critique its more recent use in complex systems theory. While resilience was seen as a logical step towards adaptive capacities in ecological domains (Holling Citation2001), complex adaptive systems do not necessarily have the same flexibility when applied to market logics, and could potentially result in neoliberal operations (Walker and Cooper Citation2011). Weichselgartner and Kelman (Citation2015) further criticise the term in its technical-reductionist application. Meaning, when administered by scientists and policy-makers, resilience often fails to incorporate the differing geographical and socio-cultural contexts, in terms of the local knowledge that exists (Weichselgartner and Kelman Citation2015). Furthermore, resilience focuses greatly more on adaptation instead of transformations necessary to combat large-scale global issues, such as climate change (Kenis and Lievens Citation2014). In order to overcome these risks, the authors recommend a focus on bottom-up processes and knowledge co-production (Weichselgartner and Kelman Citation2015). MacKinnon and Derickson (Citation2012) echo similar concerns about the externally defined, top-down nature of resilience. Resilience is often imposed onto supposedly vulnerable communities “from outside” usually without much preference to the community members’ ideas and priorities or without making use of their lived experiences (van der Vaart, van Hoven, and Huigen Citation2017, cited in Trell et al. Citation2017). Other scholars have responded to the critique by using the term “evolutionary resilience” suggesting that it is not about a return to normality, but about the ability of complex social-ecological systems to change, adapt, and crucially, transform in response to stresses and strains (Davoudi Citation2012, 302). Authors focusing on community resilience (e.g. Brice and Fernandez Arconada Citation2017; Forrest, Trell, and Woltjer Citation2017; van der Vaart, van Hoven, and Huigen Citation2017), have emphasised the need for trust and exchange between professionals/policy-makers (and their expert knowledge) and point to the relevance of capacities present at the local level.

MacKinnon and Derickson (Citation2012) have suggested resourcefulness as an alternative concept for resilience. In this context, resourcefulness underscores local knowledge exchange in communities and seeks to address unequal resource distribution, while empowering communities’ capacity to confront these issues through democratic means (MacKinnon and Derickson Citation2012). In contrast to resilience, resourcefulness concentrates on the community level, reflects a process instead of an inherent quality, and expresses an unabashedly normative dimension in addressing issues of inequality, through the focusing on redistributing materials and recognition of self-worth (MacKinnon and Derickson Citation2012). MacKinnon and Derickson (Citation2012) propose that resourcefulness consists of four specific aspects: resources, skill sets and technical knowledge, indigenous and “folk” knowledge, and recognition. While the local context is prioritised in this definition, resourcefulness acknowledges that global factors are intertwined with the local, and, thus, also play a role.

Ganz (Citation2000) views resourcefulness analogous to ideas of strategic capacity, where ample resourcefulness could potentially offset an organisation’s lack of resources. Analysed through social movements, Ganz (Citation2000) operationalises strategic capacity by analysing three influences within the dimensions of an organisation’s leadership and organisational structure: salient knowledge and the use of the local environment, heuristic processes and creative thinking, and motivation (Ganz Citation2000). Within these three elements, the effectiveness of strategic capacity hinges on the role of the local environment in leadership and organisational structures. Highlighting knowledge transfer within these elements is therefore essential in determining the resourcefulness of an organisation.

Resourcefulness could, arguably, be compared with a number of terms, such as civic engagement (Adler and Goggin Citation2005), collective efficacy (Sampson, Raudenbush, and Earls Citation1997), or social cohesion (Forrest and Kearns Citation2001). Similar to Norris et al.’s (Citation2008) interpretation of community resilience, resourcefulness is a broad, umbrella term, relating different community adaptive capacities. Furthermore, there is a risk of the word being too vague or losing meaning due to the current gap in empirical research of the concept or lack of a compelling definition, as also seen with resilience (Walker and Cooper Citation2011). Resourcefulness, however, differentiates itself by foregrounding the material dimension, linking actors to place-based material resources and knowledge. Thus, a discussion on resourcefulness, opens up a connection to resources, beyond simply social connections.

It has been suggested that resourcefulness is a novel practice and place-based approach and that place-based practices of resourceful communities can potentially result in social innovation (Horlings Citation2017). The concept is also essential when considering solutions to climate change. Franklin (Citation2018) stresses the importance of situating resourcefulness processes in a physical space, as the concept endorses a place-based nature. Investigating resourcefulness in terms of community environmental practices drives a context-specific dialogue. What is lacking from such a discourse, however, is empirical work documenting resourcefulness processes, and how the concept is materialised in differing contexts – a gap this research will address.

2.3. Operationalisation: conditions and processes towards social innovation

Social innovation and resourcefulness overlap on several points – their commitment to novel developments, environmentally and socially sustainable futures, and empowered communities. While both are seen as processes, there is often an associated end-result – such as an empowered community or equal distribution of resources (Baker and Mehmood Citation2015; MacKinnon and Derickson Citation2012; Moulaert et al. Citation2005). Despite the gap in the literature linking social innovation and resourcefulness, previous enablers of social innovation have been identified, such as having a diverse set of resources (Baker and Mehmood Citation2015), organisational capacity (Lang Citation2010), and the temporal and spatial character of acquiring and distributing resources (Walker and McCarthy Citation2010).

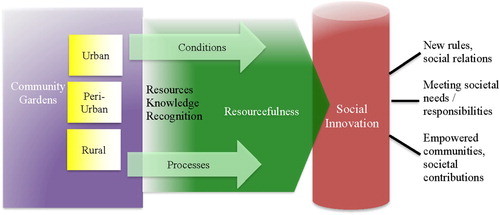

Resourcefulness is operationalised here as a condition and a process – inspired by MacKinnon and Derickson (Citation2012) and Ganz (Citation2000) – and includes material and non-material resources, knowledge transfer, and recognition that exist in the respective gardens (see ). While knowledge could also be considered a resource, including it as its own separate component further emphasises its importance. The dimension of resources highlights the core emphasis on the unequal distribution of goods, but also includes non-material qualities, such as social relations, and, more specifically, “organizing capacity, spare time and social capital” (MacKinnon and Derickson Citation2012). Furthermore, the authors highlight the necessity of technical skills, as a basis for communication, and local knowledge, in order to properly develop context-specific solutions (MacKinnon and Derickson Citation2012). Resources studied include material resources, such as land and gardening tools, and non-material resources, such as formal and informal networks, social relations, spare time, and organising capacity.

Knowledge transfer includes making use of local as well as institutional knowledge and skills. Moreover, this study focuses on knowledge backgrounds of garden participants, as well as knowledge networks, emphasising learning processes that occur at the gardens and how knowledge is exchanged – not only technical skills, but also local, context-specific knowledge. This includes how knowledge, both general and food/agriculture-specific, is shared amongst participants in the initiatives, as well as to the outside community.

In this sense, knowledge is relational, or fluidly constructed through place-based social relations (Horlings, Collinge, and Gibney Citation2017). Exchanging knowledge across disciplines in a non-hierarchical manner is expected to foster creativity in social innovations (Horlings, Collinge, and Gibney Citation2017). Local knowledge, a key component of resourcefulness is also expected to take centre stage in social innovations, which can function as a “site of social learning” (Baker and Mehmood Citation2015, 327).

In line with MacKinnon and Derickson (Citation2012), this research examines the “recognition” that exists in the garden, defined as “a sense of confidence, self-worth, and self-community-affirmation” (p. 265). This draws on theories of Honneth, as interpreted by Buchholz (Citation2016). Through investigating processes of recognition, this research seeks to understand techniques used by the organisation to create a shared understanding of self-worth (in and out of the initiative), while additionally exploring how the garden is perceived and recognised by the community and government.

Social innovation is operationalised in this paper by using a hybrid of Bock’s (Citation2016) and Moulaert et al.’s (Citation2005) perspectives – as initiatives that include new rules and social relations, meet societal needs and responsibilities, and result in empowered communities and societal changes and contributions. The focus on new rules and social relations will investigate innovative ideas, thus, how resources, knowledge, and recognition present new and different mechanisms within organisations. Societal needs and responsibilities will explore how the garden organisations interact with larger communities, but also methods used by initiatives to meet the needs of their members. Lastly, empowerment is essential in evaluating the impact of community gardens, but, at the same time, is the most difficult to operationalise. This research will evaluate this component by asking participants about changes in their own lives or communities, potentially resulting from the garden. The resourcefulness component of recognition is expected to be vital in determining community empowerment as participants’ mobilising capacity is a determining factor in contributing to greater societal change.

Social innovation and resourcefulness are both stressed as operating in a specific context and embedding a place-based nature (Baker and Mehmood Citation2015; Bock Citation2012; MacKinnon and Derickson Citation2012). Thus, investigating social innovation through resourcefulness conditions and processes further applies a place-based focus to social innovation, linking it to practices and a physical space.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research context

All three cases investigated are located in the North of the Netherlands (see ). The Netherlands and Europe are currently seeing a push for “active citizenship” and the creation of a “participatory society” through citizen-driven initiatives, which are believed to promote a sense of civic responsibility and involvement in aspects of governance, creating new relations, and ultimately resulting in a more cohesive society (Boonstra Citation2015). Relations between government institutions and civil society play an important facilitating role in social innovation, whether it’s through embracing interaction with local actors in order to expand initiatives into greater society (Seyfang and Haxeltine Citation2012), or seeing new forms of governance as a tool for up-scaling initiatives (Baker and Mehmood Citation2015). In order to explore differences across social and spatial scales, cases were chosen in rural, peri-urban, and urban contexts.

In a rural context, this study investigates a community garden located in the village of Eenrum, one of the northern most municipalities of De Marne, in the province of Groningen. This garden, the Pluk en Moestuin (“Pick and Vegetable Garden”), is run by a group of five to ten people, mostly middle-aged women from the area. Diverting from perhaps more “traditional” rural allotment style gardens, the Pluk en Moestuin cultivates a collective plot of land using permaculture methods. Produce from the garden is also shared among its members, often eaten in a together. Entering its fifth season (2017), the garden and its collective volunteers branched out by beginning a school garden in the village the previous year (2016). Once a week the group leads a class of school children, teaching them about cycles and processes of growing food. The garden’s interaction with the community, through the school, as well as its use of “novel” practices, such as permaculture techniques and sharing produce amongst participants, makes the space ideal for investigating social innovation and resourcefulness.

The second garden, Doarpstun Snakkerburen, is situated in the former town of Snakkerburen, a town that has since been integrated into the fringe of the city of Leeuwarden, thus representing a peri-urban community garden. Starting in 2001 and boasting about 70 volunteers, the garden is the largest and oldest of the three researched (Kennisnetwerk krimp Noord-Nederland Citation2015). All of the produce is grown using organic methods and sold at a volunteer-run garden shop at prices that rival those of conventional supermarkets (Veen Citation2015). The Doarpstun further broadens its impact by engaging adults and children in community activities, such as festivals, concerts, educational projects, and an annual summer musical (Kennisnetwerk krimp Noord-Nederland Citation2015). The garden’s location, scale, and history contrasts that of the Pluk en Moestuin (and, as will be described, Toentje), rendering it an attractive case for comparison.

Thirdly, Toentje, the urban garden, is a collaboration between the Municipality of Groningen and the local food bank. This initiative not only attempts to address issues of fresh food access through a volunteer-based garden, but also emphasises a circular economy approach through “climate-friendly” techniques, such as using renewable energy (Toentje Citation2017). Through the project’s bottom-up attempts to tackle issues of food access and environmental sustainability, Toentje could be categorised as a social innovation. The collaboration with the municipality is relevant to the “hands-off” approach taken by the municipality of Groningen, which attempts to play a facilitating role in citizen projects, emphasised throughout the city food vision, Groningen Groeit Gezond (Groningen Gemeente Citation2013). While the vision’s main goal is to create a more sustainable urban food system, it acknowledges this must be done by making room for initiatives, cooperating with citizens and consumers (Groningen Gemeente Citation2013), aspects also seen in previous literature on social innovation (Baker and Mehmood Citation2015).

3.2. Methods

This study utilised a combination of participant observation and in-depth interviews to investigate conditions and processes of resourcefulness in community gardens. Additionally, this research used a multiple case study approach, to gain an in-depth understanding through various data sources (Yin Citation1994). The differing contexts provide insights into how rural, urban, and semi-urban gardens and communities differ, and what is shared in terms of elements of resourcefulness and social innovation.

Engaging in participant observation was used to gain a broad understanding of the organisation of the community gardens and its members, as well as understanding specific gardening practices, beliefs, and values. The author conducted participant observation by volunteering in each garden four to five times in a period of two months in the late spring of 2017. This method provided the optimal opportunity to understand day-to-day gardening practices and speak with other volunteers. Participants often spoke candidly of their personal life, motivations for volunteering, and benefits their garden work brought them. Such conversations aided the understanding of the operation of individual gardens and broadened this research’s perspective of how the initiative contributes to the communities, also as an example of a social innovation. Participant observation also functioned to validate information and build a context for the interviews.

Interviews provided a more in-depth understanding of inner logistics of each gardening project. For each case, two to three interviews were conducted (eight overall) – with the initiator, a volunteer in an organising role, and, if necessary, a third volunteer in the garden. Interviews focused on relevant backgrounds and motivations of participants, especially experiences that led to garden participation or initiation. These different perspectives provided the researcher an understanding of how participants accessed resources in their environments applied previous (personal and professional) backgrounds to the, gardens, and how these were received by the community. All interviewee names listed in this paper are pseudonyms to protect the identity of the participants.

Observations and interviews were transcribed and coded based on the operationalisation of resourcefulness and social innovation discussed above, see for an overview of the themes and sub-themes investigated. Specifically, interviews with initiators were useful for understanding pre-existing resourcefulness conditions used to help form the garden, such as accessing the land and navigating grant proposals, while interviews and conversations (during observations) with volunteers provided insight into garden processes, such as knowledge exchange, social connections made in the garden, and broader contributions of the garden in the lives of participants.

Table 1. Themes and sub-themes of resourcefulness and social innovation, guiding the data analysis.

4. Results

4.1. Pluk en Moestuin, Eenrum: using permaculture practices for community building

The Pluk en Moestuin is a collective of approximately eight women from Eenrum, and the surrounding villages. Eenrum, a village of about 1300 inhabitants, has its own school, sports clubs, and general practitioner, thus, more services than most in this depopulating region, according to respondents. While the village is considered quite active, none of the activities suited Brenda, the initiator of the garden. As an attempt to gain more connections in her immediate environment, Brenda submitted an advertisement in the local paper and began recruiting interested community members for a community garden.

Conditions of resourcefulness were specifically seen through gardening and organising knowledge backgrounds of garden participants. When each participant contributed based on his or her strengths, the collective was able to organise the garden to suit their goals. For example, Emma, also an organising member, drew from her informal background in agriculture and permaculture methods, while Brenda capitalised on her networks in the village and previous experience organising social projects and coaching citizens to start their own.

Brenda, Emma, and the gardening collective located a plot in Eenrum that technically belonged to the municipality, but was being neglected by its current caretakers. The municipality agreed to pay the rent, as long as the group took care of the land. A community organisation in the village granted the collective further finances for accessing building materials, and, once the garden was more established and laid out their clear goals, they were able to become a stichting, or foundation, permitting them rights from the municipality and opportunities to access more funding. Brenda’s background in collaborating with governmental organisations was vital throughout this communication and establishing the garden.

Unlike more rural traditions of allotment or home gardens, this project experiments with permaculture methods. In addition to creatively reworking natural systems to build productive and permanent structures, permaculture gardening also integrates a social aspect. Brenda notes how this method practice, unique to the rural community, encourages more social interaction in that:

Permaculture is more than only gardening. Permaculture is also a community and sharing. It’s about sharing and doing it together.

While the village and municipal governments willingly fund the project, not all feedback for the Pluk en Moestuin is positive. For example, the gardening collective had previously received negative feedback from neighbours in the community, due to the “strange” permaculture methods.

The project’s perception of being “different” did contribute to difficulties in recruiting more participants and potentially up-scaling to involve the entire village, a disappointing realisation for the initiators. However, expanding was not the main objective of the garden and, focusing on social cohesion among involved participants was a more attainable goal. Conversely, events, such as open days, helped communicate the garden to the community, opening social networks, as well as defining it as a space for exchanging gardening knowledge.

In addition to the permaculture garden, the collective at the Pluk en Moestuin began a garden at the neighbouring school the previous year (2016). Through weekly classes, the collective teaches 11–12-year-old students about food and gardening, beginning with seeding and planting, and hosting a cooking lesson towards the end of the growing season. In these classes, volunteers provide students with a hands-on learning experience, and, indirectly, also boost their confidence. Brenda explains how one parent confided in her:

“What you did to my girl, was great. It made her stand and she was so insecure and now she is there.” She has changed so much in a year! […] So it brings a lot for the children.

In sum, the garden collective at the Pluk en Moestuin exhibits resourcefulness through utilising formal trainings (such as group facilitation), as well as more informal backgrounds (in agriculture, for example). While the initiative draws resources from government organisations (with grants and land), they have learned to be quite autonomous and, as Emma states, “we’ve done quite a lot ourselves, actually”. Social innovation is manifested in the Pluk en Moestuin through addressing social responsibilities, such as educating youth and contributing to social cohesion among its members. Even though the garden received negative feedback from the community, their strong internal network supported their efforts and gave members the motivation to continue to experiment with the gardening and the school garden. Beginning a relationship with the school, the collective provides students with an education, alternative to what they would receive in the classroom, learning about natural processes, and, in the process, gaining confidence in other aspects of their lives.

4.2. Doarpstun, Snakkerburen: culturally embedded organic gardening

In the province of Friesland, just north of the city of Leeuwarden, is the Doarpstun. This garden began in 2001 when a group of villagers from Snakkerburen wanted to transform a neglected plant nursery into a communal green oasis. The initial collective had four main goals: to use organic methods, sell produce at low prices, host educational and cultural activities, and expand the gardening area. While only one of the original initiators is still involved, the garden has grown to about 70 volunteers, with workers also coming from Leeuwarden and neighbouring villages, and hosts a play and cultural activities on the grounds every year.

The current volume of volunteer support could be attributed to the Doarpstun’s collaboration with WellZo, an organisation that matches potential volunteers with organisations seeking workers. Previously in 2008, many garden participants lost interest, resulting in a lack of volunteers. Subsequently, the garden partnered with WellZo as a way to maintain a sufficient help and now receives 20 of its 70 participants through the organisation. Connections with such operations are an example of resourcefulness processes in the garden.

The collaboration between WellZo and the Doarpstun is especially useful for those not otherwise able to hold a steady job, but still seek structure and connections in their lives. Glenda describes that there is:

[…] a group of volunteers who need a bit of ondersteuning [support], a bit of structure, that’s good for them, and a place where not that much is asked of them. We have Robert, he is making our coffee and tea, and that is it. And for him, that’s okay. He’s using a lot of medicines, he’s depressive, psychosis, but he’s coming here before 8 o’clock in the morning. Before we come, the coffee is ready! And he’s doing the washing up and he’s doing this and great! We’re glad Robert is here.

When somebody new comes here, there is a lot of investing in this person, not only trying to learn (sic) him / her the skill needed in the garden, planting techniques, how you hoe, how you do this, how you do that, but also look at this person and what his or her needs are.

In addition to running the garden, the Doarpstun also invests in cultural activities, for example, a theatre production every summer. Through these activities the garden becomes a venue of interaction for the villagers and socially embedded in the community, attracting residents from Leeuwarden and beyond. The culturally intertwined nature of the play ultimately aids the garden’s resourcefulness, by opening up social spaces for participation, illustrating the Doarpstun’s social and cultural impact.

The influence of the garden is not limited to the play and development of its volunteers, but also to other community and food system developments. For example, a former garden volunteer acquired his own plot in the city of Leeuwarden to begin a permaculture garden. During the course of this research, he and the Doarpstun initiator met to explore potential collaborations between the two. Thus, while the garden has reached its limits of physical expansion, the knowledge and skills acquired by volunteers continues to extend beyond its boundaries.

The collective at the Doarpstun exhibits resourcefulness through maximising community and governmental programmes, building on the knowledge and skills of its volunteer base, and expanding social networks through cultural productions. While the garden has had issues in the past (recruiting volunteers and receiving noise complaints), these issues are solvable through negotiating with community institutions and stakeholders. Social innovations are also seen in the Doarpstun through connecting villagers in Snakkerburen, contributing to the social cohesion of the village, addressing developmental needs of volunteers, as well as healthy food access of the customers, and empowering participants to have the capacity to continue to address the goals of the garden and community.

4.3. Toentje, Groningen: community and institutional collaborations for fresh food access

Toentje, located in the city of Groningen, is the brainchild of Jesse. After leaving the local supermarket one day, he was struck by the magnitude of processed food that filled the carts of other shoppers and thought “why don’t people choose healthy food on a tight budget?” After some contemplation, Jesse drafted a business plan for a garden that grows vegetables for the foodbank and presented it to the municipality. Coincidentally, the municipality had recently finalised a new Armoedebeleid, or Poverty Policy, which also included the idea to create a garden for the foodbank. This fortuitous match led to fruitful collaboration between the municipality, Jesse, and the foodbank.

The initial collaboration with the municipality greatly benefitted Toentje in opening access to other networks, aiding the garden’s resourcefulness. Not only did the municipality provide the organisation with initial funding, but they also collaborated in finding a suitable piece of land to cultivate. Jesse mentions the success of the project was partially due to “the synchronicity of all of this” and specifically that “the municipality has a vision on these kinds of subjects and on local food and on city farming, and the combination of city farming and health care”. Manon, the volunteer coordinator, elaborates by saying:

The Groningen city […] gives us room to experiment. If you work in a smaller village town, they might be more conservative … [here] people know about innovation. There’s room to experiment.

While expanding, Toentje continues to build off of their initial connections as well as create new networks in the community, as an attempt to become more autonomous. Currently, 95% of their funding comes from the municipal government, which the organisation strives to lower to 50% through diversifying their income streams. Meeting this goal takes a certain degree of creativity and willingness to experiment. Jesse discusses his approach:

I just search for the people who know it and just start to collaborate […]. So if I don’t know anything about a certain subject, I just look for, “hey who in my environment knows a bit about this stuff?”

These boundaries are further extended as Toentje looks to potential collaborators for expanding to small villages in the province. Coincidentally, the municipal foodbank director also manages those in the rest of the North of the Netherlands, giving Toentje this opportunity. Through trial-and-error Jesse has continued to contact other potential collaborators, including the Dutch health insurance company Menzis, and the University of Groningen. Working with these institutions contributes an international component, where the garden is not only a venue for local knowledge exchange, but also creates new institutional relations among a range of local and global actors, for example via exchanging knowledge.

Similar to the previous two gardens, Toentje is supported by a team of 30–35 volunteers that also work in the garden. Jesse notes that:

The people who work at Toentje range from “ex-homeless” to “ex-pat” so that’s the balance we have, and that’s our power as well, that’s our strength. We don’t have “one type” of volunteer from one place in society […] and that’s what makes us different.

To sum up, Toentje exhibits characteristics of resourcefulness through creating broad and diverse social networks, with formal as well as more informal institutions. While these partnerships are not always successful at first, learning from their mistakes aids the initiative in developing new, creative relationships. Through these collaborations, the garden generates innovative relations between governmental bodies and citizen initiatives, in order to meet the social needs of fresh food access for food bank recipients. Similar to the Dorpstun, Toentje also prepares garden volunteers for the workforce by providing structure and training. The garden is further building upon these relations and expanding to other communities in the province, thus, potentially out-scaling and addressing food access in other localities. See for a more detailed overview of resourcefulness and social innovation in all three gardens.

Table 2. Results of resourcefulness and social innovation in community gardens.

5. Discussion

5.1. Conditions of resourcefulness to support social innovation

Through identifying conditions and processes, this research has identified five enablers of resourcefulness to stimulate social innovation in community gardens.

5.1.1. Directive power and motivation

While conditions varied greatly among the gardens, all collectives exhibited a clear motivation and directive power, defining clear goals. In most cases, there were only one or two main initiators, which, perhaps, made defining the organisation’s objective more manageable. This also points to the importance of place-based leadership, for initiating new activities, supporting knowledge transfer, and motivating and aligning people around a joint goal (Horlings Citation2010; Roep, Wellbrock, and Horlings Citation2015).

Community gardens can potentially serve a variety of needs, however, when initiators narrowed their goal to a specific contribution, the collectives gained a clearer direction for goal-setting. This finding aligns with that of Seyfang and Haxeltine (Citation2012), who emphasise the importance of developing short-term and achievable expectations in grassroots initiatives, especially in the out-scaling of these projects, towards more long-term goals. Furthermore, the garden initiatives’ motivations prioritised local environmental needs, a scale that perhaps gives them the capacity to embed themselves in their direct community. Such positioning appeared to be vital, prior to attempts of expanding or up-scaling. Effectively, a clear, locally relevant motivation prioritises accessing resources available in the direct environment, and, through this interaction, identifies potential routes to contribute to social needs, a key component of social innovations.

5.1.2. Using diversity in garden resources

Organisational diversity in resourcefulness processes was also found to be valuable in contributing to the social innovation of the initiatives. This was seen in processes, including through funding sources, initiative participants, and other ventures of the garden collectives.

While all three cases utilised government finances and support (including grants and land access), each also pursued other funding sources. This includes, for example, organising a rommelmarkt (garage sale) at the Doarpstun or starting a community-run restaurant at Toentje. While Walker and McCarthy (Citation2010) illustrate that governmental grants do not necessarily increase the success rate of an initiative, the authors recommend that organisations develop locally based funding sources, as this not only contributes to the long-term resilience of the initiative, but also works to gain support and nestle it in the community, a notion realised in the gardens researched (Toentje, for example, aims to become more autonomous from municipal financing). Through various funding sources, these initiatives become more independent, but also transfer power from the government to the citizens, empowering the community to address social needs through collective action, aligning with aspects of social innovation (Bock Citation2012; Moulaert et al. Citation2005).

In addition to diversifying their funding, all three gardens emphasised the importance of a diverse set of volunteers, either with differing professional and personal backgrounds, skills and capacities, or individual interests. By diversifying the participant pool, the gardens match individuals to a variety of roles, skills, and needs of the organisation. Furthermore, by engaging a diverse public, the organisations expand their own social networks, contributing to the gardens’ potential expansion and further integrating them in the community. This component also highlights a unique quality of community gardens as spaces that have potential to bring together participants of a range of backgrounds, also the reciprocal advantages of building new relationships and social capital in these communities – for the participants as well as the organisations (Firth, Maye, and Pearson Citation2011).

As a strategy to diversify funding and volunteer pools, the gardens also diversified their ventures by engaging in non-garden activities and projects, thus becoming further embedded in the community fabric. Walker and McCarthy (Citation2010) see similar results, when “an organization’s embeddedness in the local institutional environment supports [its] survival” (330). Thus, by experimenting with other methods of reproducing the space, the garden collectives engage with the community to spatially transform their built environment, based on their contextual needs. As a result of diversifying funding sources, garden participants, and projects in the garden space, the initiatives were able to expand their networks, creating new, and perhaps more effective connections and impacts.

While the diversity of funding sources and knowledge greatly benefitted gardens studied, arguably a baseline of knowledge and skills were necessary across the board. For example, if communities did not have the capacity to navigate the bureaucracy of applying for and receiving grants, such initiatives would not have come to fruition. This also begs the question, what relevant aspects does resourcefulness entail and what are fundamental knowledge or skills?

5.1.3. Experimental knowledge processes

Key to social innovations are the “innovative” and creative processes that they promote. In relation to resourcefulness, these practices were greatly materialised in the knowledge processes in the gardens.

In all cases, few participants had agricultural backgrounds, rather, most learned how to work the earth from others. This finding does not necessarily discount the value of local traditional knowledge, emphasised by Calvet-Mir et al. (Citation2016). Rather, it recognises that community gardens’ use of other kinds of knowledge, organisational skills, and capacities to learn, could potentially offset the importance for previous agricultural knowledge.

Experimental and reflexive techniques were visible throughout participants’ actual work in the garden as well as in their planning and collaborations (ex. altering lessons at the school garden based on the previous year or making changes to the annual plant and seed plan). Regularly reflecting on organisational and learning processes illustrates processes of innovation as well as processes of resourcefulness. This finding aligns with Beers and van Mierlo (Citation2017), who illustrate the importance of reflexivity in contributing to innovation, emphasising the importance of knowledge processes.

While experimentation in the garden is invaluable in its contribution as a social innovation, this characteristic contains the risk of reinforcing the concept as a “buzz word” and highlighting the “pro-innovation bias” (Bock Citation2012; Sveiby, Gripenberg, and Segercrantz Citation2012) Thus, it is an appropriate reminder to consider the more nuanced contributing factors, but also consequences of social innovation.

5.1.4. Strong internal support and recognition

Resourcefulness highlights the importance of recognition in organisations, through support from the greater community, as well as support within the organisation. Strong internal support, especially emphasised among garden volunteers, potentially relieved pressures of out-scaling, leaving room to address the initiative’s initial needs and, furthermore compensated against negative external feedback.

Nevertheless, community recognition and support in the garden spaces should not be discounted. Backing from the community has strong implications for social innovation in the space, as when a community supports the garden, it can also reap the benefits, through the garden’s physical space, or the social networks embedded in it. For example, after relocating Toentje realised a few of their new neighbours were originally opposed to the garden due to their unmet concerns of a playground in disrepair. Initiating a dialogue with the community helped Toentje influence the municipality to fix the playground, gaining neighbourhood support in the process. In this way, community support benefits both parties, and recognition processes could potentially prevent exclusionary processes of such collectives.

5.1.5. Place-based practices

The gardens illustrate the place-based or contextually dependent nature of resourcefulness. Each garden exhibited disparities that could be attributed to their specific rural, peri-urban, and urban differences. For example, the rural (and peri-urban) gardens struggled more in recruiting volunteers than the urban garden, possibly because those in smaller villages had space to maintain home gardens, as suggested by participants. Rural contexts also resisted more against unfamiliar gardening practices, such as the permaculture garden, which, perhaps, also clashed with rural gardening traditions. Additionally, the urban garden also had more difficulty maintaining a permanent location than the other two. Land tenure is a common issue for urban community gardens, with evidence that gardens themselves can even increase property values, resulting in detrimental effects for their own longevity (Voicu and Been Citation2008).

The gardens illustrate the relationality of practices beyond geographical boundaries. For example, Toentje taps into more international and national institutions, such as the University of Groningen and Menzis, perhaps due to their connections in the urban environment. While the Pluk en Moestuin also maximises their network, the small scope, perhaps, initiates collaborations more on a regional or municipal level. That being said, the networks in Eenrum are also closely knit, where, for example, children of garden participants attend school in the village and also work in the school garden. These diverse scales further highlight the range of social innovations, and the importance of considering the local context with such initiatives. While there is a greatly “growth-based” bias of social innovations (Sveiby, Gripenberg, and Segercrantz Citation2012), the place-based emphasis re-focuses the impact of small-scale initiatives, like the Pluk en Moestuin, for their local community. Resourcefulness, thus, potentially brings attention to community-based change instead of that at a more abstract level.

Highlighting the place-based elements of social innovation and resourcefulness further stresses the importance of a context-dependent approach, not only to determine specific community needs, but also how to utilise the local environment to address these needs.

6. Conclusions

This research explored the connection between social innovation and resourcefulness through empirical evidence based on rural, peri-urban, and urban community gardens. While often social innovation is disconnected from practice, we have aimed to reroute this argument by determining five aspects essential in facilitating social innovation through conditions and processes of resourcefulness, including: (1) defining a clear motivation and directive power of the initiative; (2) utilising a diverse resource base (multiple funding streams, a heterogeneous group of volunteers and knowledge, and alternative community ventures), to further embed the initiative into the community; (3) creative knowledge processes and the capacity to experiment; (4) internal support and recognition within the collective and (5) place-based (context-dependent) practices. Through these results, this research found that resourcefulness, in contributing to social innovation, should be stressed as a process and as place-based.

Processes of resourcefulness show how a community can be resourceful and how they learn, instead of maintaining pre-existing community characteristics. These processes have the potential to redistribute agency to communities, who have the opportunity to become more or less resourceful, and increase their capacity for social innovation. Furthermore, conceptualising resourcefulness as practices exercised by communities, strengthens capacities for social innovation, empowering communities to address local needs. However, the ways in which social innovations materialise are not exclusively positive, thus, it is important to heed to the unintended consequences of such projects (Sveiby, Gripenberg, and Segercrantz Citation2012). For example, this could include urban community gardens contributing to an increase in property values and gentrification, potentially reinforcing inequalities they intended to counteract (Arnold and Rogé Citation2018; Checker Citation2011; Voicu and Been Citation2008).

Proposing resourcefulness as a process is also relevant for discussions on resilience. While resourcefulness, unlike resilience, more explicitly privileges civic engagement and traditional knowledge exchange, when stressed as a process, its use is even more valuable as an alternative to resilience, in empowering local communities (MacKinnon and Derickson Citation2012). Resourcefulness, however, is but one aspect that contributes to resilience, and empirically analysing other aspects would be a valuable contribution for future research.

Another potential for future resourcefulness research would be to explore the connection between bonding and bridging social capital. While Robinson and Carson (Citation2016) provide a comprehensive overview of connections between various community capitals and resilience, this has yet to be investigated in terms of resourcefulness. Specifically, this research saw bonding and bridging social capital not only as a resource the gardens accessed, but also tied to internal community recognition (Putnam Citation2000).

This research has illustrated that resourcefulness is not only a process, stemming from the immediate community, but these processes also hinge on the physical space in which they are based. This result supports Baker and Mehmood’s (Citation2015) assertion that “social processes occur through and are shaped by material forms that constitute and are constituted in place-specific settings” (327). What this research also stresses, however, is how the place-based nature of resourcefulness can be used to focus social innovation on a local scale. Resourcefulness processes in the gardens also determined the direction in which the spaces developed, whether that means by, for example, expanding physically (as seen at the Doarpstun), or broadening institutional ties (seen at Toentje). While much research focuses on social processes in community gardens, whether it is social capital or social cohesion, this research further connects these spaces to the material conditions in which they take place. Operating in different contexts, the gardens made use of differing resource bases and spatial and social environments, resulting in a range of societal contributions. Comparing diverging urban, rural, and peri-urban sites demonstrated that there is no “one-size-fits-all” equation for enabling social innovations through resourcefulness. Rather, the richness lies in the diversity of surrounding and interacting environments.

While community gardens may seem to be small and, perhaps, insignificant to some, their value is enhanced when framed as social innovations. This perspective not only stresses the creative planning that goes into community gardens, but also the nexus of functions that one space contributes to community life. At the core of social innovation is the idea that “new” practices and relationships facilitate potentials for “bettering” society. When such experimental practices expand, they have the potential to strengthen their societal impact. This research has highlighted, in several initiatives, attempts to up and out scale practices in community gardens, including physically extending the garden property, branching out to create satellite gardens in other locations or reaching different populations through community and school educational programmes. Given these examples, we expect that further research on social innovation and resourcefulness will provide a fruitful avenue to increase our insight and contribute to debates on food planning and community initiatives.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Adler, R. P., and J. Goggin. 2005. “What Do We Mean By “Civic Engagement”?” Journal of Transformative Education 3 (3): 236–253. doi: 10.1177/1541344605276792

- Armstrong, D. 2000. “A Survey of Community Gardens in Upstate New York; Implications for Health Promotion and Community Development.” Health & Place 6 (4): 319–327. doi: 10.1016/S1353-8292(00)00013-7

- Arnold, J., and P. Rogé. 2018. “Indicators of Land Insecurity for Urban Farms: Institutional Affiliation, Investment, and Location.” Sustainability 10 (6): 1–9. doi: 10.3390/su10061963

- Artman, M., and K. Sartison. 2018. “The Role Urban Agriculture as a Nature-Based Solution: A Review for Developing a Systemic Assessment Framework.” Sustainability 10 (6): 1937–1969. doi: 10.3390/su10061937

- Baker, S., and A. Mehmood. 2015. “Social Innovation and the Governance of Sustainable Places.” Local Environment 20 (3): 321–334. doi: 10.1080/13549839.2013.842964

- Beers, P., and B. van Mierlo. 2017. “Reflexivity and Learning in System Innovation Processes.” Sociologia Ruralis 57 (3): 415–436. doi: 10.1111/soru.12179

- Bock, B. 2012. “Social Innovation and Sustainability; How to Disentangle the Buzzword and Its Application in the Field of Agriculture and Rural Development.” Studies in Agricultural Economics 114: 57–63. doi: 10.7896/j.1209

- Bock, B. 2016. “Rural Marginalisation and the Role of Social Innovation; a Turn Towards Nexogenous Development and Rural Reconnection.” Sociologia Ruralis 56 (4): 552–573. doi: 10.1111/soru.12119

- Boonstra, B. 2015. “Planning Strategies in an Age of Active Citizenship.” PhD diss., PhD Series InPlanning: Groningen.

- Brice, S., and S. Fernandez Arconada. 2017. “Riding the Tide: Socially-engaged art and Resilience in an Uncertain Future.” In Governing for Resilience in Vulnerable Places, edited by E. M. Trell, B. Restemeyer, M. M. Bakema, and B. Van Hoven, 224–243. London: Routledge, Taylor and Francis group.

- Buchholz, T. 2016. “Struggling for Recognition and Affordable Housing in Amsterdam and Hamburg.” PhD thesis. University of Groningen.

- Calvet-Mir, L., C. Riu-Bosoms, M. González-Puente, I. Ruiz-Mallén, V. Reyes-García, and J. Luis Molina. 2016. “The Transmission of Home Garden Knowledge: Safeguarding Biocultural Diversity and Enhancing Social-ecological Resilience.” Society and Natural Resources 29 (5): 556–571. doi: 10.1080/08941920.2015.1094711

- Carolan, M. 2017. “More-than-active Food Citizens: A Longitudinal and Comparative Study of Alternative and Conventional Eaters.” Rural Sociology 82 (2): 197–225. doi: 10.1111/ruso.12120

- Checker, M. 2011. “Wiped out by the “Greenwave”: Environmental Gentrification and the Paradoxical Politics of Urban Sustainability.” City and Society 23 (2): 210–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1548-744X.2011.01063.x

- Corrigan, M. P. 2011. “Growing What You Eat: Developing Community Gardens in Baltimore, Maryland.” Applied Geography 31 (4): 1232–1241. doi: 10.1016/j.apgeog.2011.01.017

- European Commission. 2013. Guide to Social Innovation. Brussels: European Commission.

- Davoudi, S. 2012. “Resilience: A Bridging Concept or a Dead End?” Planning Theory and Practice 13 (2): 299–307. doi: 10.1080/14649357.2012.677124

- Firth, C., D. Maye, and D. Pearson. 2011. “Developing “Community” in Community Gardens.” Local Environment 16 (6): 555–568. doi: 10.1080/13549839.2011.586025

- Forrest, R., and A. Kearns. 2001. “Social Cohesion, Social Capital and the Neighbourhood.” Urban Studies 38 (12): 2125–2143. doi: 10.1080/00420980120087081

- Forrest, S., E. M. Trell, and J. Woltjer. 2017. “Flood Groups Ion England: Governance Arrangements and Contribution to Flood Resilience.” In Governing for Resilience in Vulnerable Places, edited by E. M. Trell, B. Restemeyer, M. M. Bakema, and B. Van Hoven, 92–115. London: Routledge, Taylor and Francis group.

- Franklin, A. 2018. “Spacing Natures: Sustainable Place-making and Adaptation.” In Handbook of Nature, edited by T. K. Marsden. London: Sage.

- Ganz, M. 2000. “Resources and Resourcefulness: Strategic Capacity in the Unionization of California Agriculture, 1959–1966.” American Journal of Sociology 105 (4): 1003–1062. doi: 10.1086/210398

- Glover, T. D. 2004. “Social Capital in the Lived Experiences of Community Gardeners.” Leisure Sciences 26 (2): 143–162. doi: 10.1080/01490400490432064

- Grimm, R., C. Fox, S. Baines, and K. Albertson. 2013. “Social Innovation, an Answer to Contemporary Societal Challenges? Locating the Concept in Theory and Practice.” Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research 26 (4): 436–455.

- Groningen Gemeente. 2013. Groningen Groeit Gezond: Uitvoeringsprogramma Voedselbeleid. Groningen: Groningen Gemeente.

- Holling, C. S. 2001. “Understanding the Complexity of Economic, Ecological, and Social Systems.” Ecosystems 4 (5): 390–405. doi: 10.1007/s10021-001-0101-5

- Horlings, I. 2010. “Vitality and Values: The Role of Leaders of Change in Regional Development.” In Vital Coalitions, Vital Regions: Partnerships for Regional Sustainable Development, edited by I. Horlings, 97–126. Wageningen: Academic Publishers.

- Horlings, L. G. 2017. Transformative Socio-spatial Planning; Enabling Resourceful Communities. http://www.inplanning.eu/categories/1/articles/200?menu_id=14§ion_title_for_article=Nieuwe±publicaties.

- Horlings, L., C. Collinge, and J. Gibney. 2017. “Relational Knowledge Leadership and Local Economic Development.” Local Economy 32 (2): 95–109. doi: 10.1177/0269094217693555

- Ilieva, R. 2016. Urban Food Planning: Seeds of Transition in the Global North. 1st ed. London: Routledge.

- Kato, Y. 2013. “Not Just the Price of Food: Challenges of an Urban Agriculture Organization in Engaging Local Residents.” Sociological Inquiry 83 (3): 369–391. doi: 10.1111/soin.12008

- Kenis, A., and M. Lievens. 2016. “Greening the Economy or Economizing the Green Project? When Environmental Concerns are Turned Into a Means to Save the Market.” Review of Radical Political Economies 48 (2): 217–234. doi: 10.1177/0486613415591803

- Kennisnetwerk Krimp Noord-Nederland. 2015. Bewoners aan zet. Kennisnetwerk Krimp Noord-Nederland. ISBN/EAN: 978-90-819356-8-5.

- Kingsley, J., and M. Townsend. 2006. “‘Dig in’ to Social Capital: Community Gardens as Mechanisms for Growing Urban Social Connectedness.” Urban Policy and Research 24 (4): 525–537. doi: 10.1080/08111140601035200

- Kirwan, J., B. Ilbery, D. Maye, and J. Carey. 2013. “Grassroots Social Innovations and Food Localisation: An Investigation of the Local Food Programme in England.” Global Environmental Change 23 (5): 830–837. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2012.12.004

- Kneafsey, M., L. Owen, E. Bos, K. Broughton, and M. Lennartsson. 2017. “Capacity Building for Food Justice in England: The Contribution of Charity-led Community Food Initiatives.” Local Environment 22 (5): 621–634. doi: 10.1080/13549839.2016.1245717

- Kortright, R., and S. Wakefield. 2011. “Edible Backyards: A Qualitative Study of House- Hold Food Growing and Its Contributions to Food Security.” Agriculture and Human Values 28 (1): 39–53. doi: 10.1007/s10460-009-9254-1

- Lang, T. 2010. “Urban Resilience and New Institutional Theory: A Happy Couple for Urban and Regional Studies.” In German Annual of Spatial Research and Policy 2010, edited by B. Muller, 15–24. Berlin: Springer.

- MacKinnon, D., and K. D. Derickson. 2012. “From Resilience to Resourcefulness: A Critique of Resilience Policy and Activism.” Progress in Human Geography 37 (2): 253–270. doi: 10.1177/0309132512454775

- Matthews, J. 2017. “Understanding Indigenous Innovation in Rural West Africa: Challenges to Diffusion of Innovations Theory and Current Social Innovation Practice.” Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 18 (2): 223–238. doi: 10.1080/19452829.2016.1270917

- Maye, D., and J. Duncan. 2017. “Understanding Sustainable Food System Transitions: Practice, Assessment and Governance.” Sociologia Ruralis 57 (3): 267–273. doi: 10.1111/soru.12177

- McClintock, N. 2014. “Radical, Reformist, and Garden-variety Neoliberal: Coming to Terms with Urban Agriculture's Contradictions.” Local Environment 19 (2): 147–171. doi: 10.1080/13549839.2012.752797

- Mehmood, A., and C. Parra. 2013. “Social Innovation in an Unsustainable World.” In The International Handbook on Social Innovation, edited by F. Moulaert, D. MacCallum, A. Mehmood, and A. Hamdouch, 53–66. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Meijer, M. 2018. “Community-led, Government-fed and Informal: Exploring Planning from Below in Depopulating Regions Across Europe.” PhD thesis, Radboud University Nijmegen.

- Moulaert, F., D. MacCallum, and J. Hillier. 2013. “Social Innovation: Intuition, Precept, Concept, Theory and Practice.” In The International Handbook on Social Innovation, edited by F. Moulaert, D. MacCallum, A. Mehmood, and A. Hamdouch, 13–24. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Moulaert, F., F. Martinelli, E. Swyngedouw, and S. Gonzalez. 2005. “Towards Alternative Model(s) of Local Innovation.” Urban Studies 42 (11): 1969–1990. doi: 10.1080/00420980500279893

- Neumeier, S. 2012. “Why Do Social Innovations in Rural Development Matter and Should They be Considered More Seriously in Rural Development Research? – Proposal for a Stronger Focus on Social Innovations in Rural Development Research.” Sociologia Ruralis 52 (1): 48–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9523.2011.00553.x

- Norris, F. H., S. P. Stevens, B. Pfefferbaum, K. F. Wyche, and R. L. Pfefferbaum. 2008. “Community Resilience as a Metaphor, Theory, Set of Capacities, and Strategy for Disaster Readiness.” American Journal of Community Psychology 41 (1-2): 127–150. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9156-6

- OECD. 2017. Stimulating Social Entrepreneurship and Social Innovation. http://www.oecd.org/cfe/leed/social-entrepreneurship-pow2015-16.htm.

- Opitz, I., R. Berges, A. Piorr, and T. Krikser. 2015. “Contributing to Food Security in Urban Areas: Differences Between Urban Agriculture and Peri-Urban Agriculture in the Global North.” Agriculture and Human Values 33 (2): 341–358. doi: 10.1007/s10460-015-9610-2

- Pol, E., and S. Ville. 2009. “Social Innovation: Buzz Word or Enduring Term?” Journal of Socio-Economics 38 (6): 878–885. doi: 10.1016/j.socec.2009.02.011

- Porter, C. 2018. “What Gardens Grow: Outcomes from Home and Community Gardens Supported by Community-Based Food Justice Organizations.” Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development 8 (Supplement 1): 187–205. doi: 10.5304/jafscd.2018.08A.002

- Poulsen, M. 2017. “Cultivating Citizenship, Equity, and Social Inclusion? Putting Civic Agriculture into Practice Through Urban Farming.” Agriculture and Human Values 34 (1): 135–148. doi: 10.1007/s10460-016-9699-y

- Pudup, M. B. 2007. “It Takes a Garden: Cultivating Citizen-subjects in Organized Garden Projects.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 39: 1228–1240.

- Putnam, R. 2000. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Robinson, G., and D. Carson. 2016. “Resilient Communities: Transitions, Pathways, and Resourcefulness.” The Geographical Journal 182 (2): 114–122. doi: 10.1111/geoj.12144

- Roep, D., W. Wellbrock, and L. G. Horlings. 2015. “Raising Self-efficacy and Resilience: Collaborative Leadership in the Westerkwartier.” In Globalization and Europe's Rural Regions, edited by M. Woods, B. Nienaber, and J. McDonagh, 41–58. Farnham: Ashgate , in print.

- Rosol, M. 2012. “Community Volunteering as Neoliberal Strategy? Green Space Production in Berlin.” Antipode 44 (1): 239–257. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8330.2011.00861.x

- Sampson, R. J., S. W. Raudenbush, and F. Earls. 1997. “Neighborhoods and Violent Crime: A Multilevel Study of Collective Efficacy.” Science 277: 918–924. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.918

- Santo, R., A. Palmer, and B. Kim. 2016. Vacant Lots to Vibrant Plots: A Review of the Benefits and Limitations of Urban Agriculture. John Hopkins University. https://www.jhsph.edu/research/centers-and-institutes/johns-hopkins-center-for-a-livable-future/_pdf/research/clf_reports/urban-ag-literature-review.pdf.

- Seyfang, G., and A. Haxeltine. 2012. “Growing Grassroots Innovations: Exploring the Role of Community-based Initiatives in Governing Sustainable Energy Transitions.” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 30: 381–400. doi: 10.1068/c10222

- Seygang, G., and A. Smith. 2007. “Grassroots Innovations for Sustainable Development: Towards a New Research and Policy Agenda.” Environmental Politics 16 (4): 584–603. doi: 10.1080/09644010701419121

- Sveiby, K. E., P. Gripenberg, and B. Segercrantz, eds. 2012. Challenging the Innovation Paradigm. New York: Routledge.

- Taylor, J. R., and S. T. Lovell. 2014. “Urban Home Food Gardens in the Global North: Research Traditions and Future Directions.” Agriculture and Human Values 31 (2): 285–305. doi: 10.1007/s10460-013-9475-1

- Toentje. 2017. Over Toentje. Accessed March 30, 2017. http://www.toentje.nl/over-toentje.

- Tornaghi, C. 2014. “Critical Geography of Urban Agriculture.” Progress in Human Geography 38 (4): 551–567. doi: 10.1177/0309132513512542

- Tornaghi, C. 2017. “Urban Agriculture in the Food-disabling City: (Re)defining Urban Food Justice, Reimagining a Politics of Empowerment.” Antipode 49 (3): 781–801. doi: 10.1111/anti.12291

- Trell, E. M., B. Restmeyer, M. M. Bakema, and B. Van Hoven. 2017. Governing for Resilience in Vulnerable Places. London/New York: Routledge/Taylor and Francis group.

- van der Vaart, G., B. van Hoven, and P. P. P. Huigen. 2017. “The Value of Participatory Community Arts for Community Resilience.” In Governing for Resilience in Vulnerable Places, edited by E. M. Trell, B. Restmeyer, M. M. Bakema, and B. van Hoven, 186–204. London: Routledge/Taylor and Francis group.

- Veen, E. 2015. “Community Gardens in Urban Areas.” PhD thesis. Wageningen University, Wageningen.

- Vitiello, D., and L. Wolf-Powers. 2014. “Growing Food to Grow Cities? The Potential of Agriculture for Economic and Community Development in the Urban United States.” Community Development Journal 49 (4): 508–523. doi: 10.1093/cdj/bst087

- Voicu, I., and V. Been. 2008. “The Effect of Community Gardens on Neighboring Property Values.” Real Estate Economics 36 (2): 241–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6229.2008.00213.x

- Walker, J., and M. Cooper. 2011. “Genealogies of Resilience: From Systems Ecology to the Political Economy of Crisis Adaption.” Security Dialogue 42 (2): 143–160. doi: 10.1177/0967010611399616

- Walker, E., and J. McCarthy. 2010. “Legitimacy, Strategy, and Resources in the Survival of Community-based Organizations.” Social Problems 57 (3): 315–340. doi: 10.1525/sp.2010.57.3.315

- Weichselgartner, J., and I. Kelman. 2015. “Geographies of Resilience: Challenges and Opportunities of a Descriptive Concept.” Progress in Human Geography 39 (3): 249–267. doi: 10.1177/0309132513518834

- Wortman, S. E., and S. T. Lovell. 2013. “Environmental Challenges Threatening the Growth of Urban Agriculture in the United States.” Journal of Environmental Quality 42 (5): 1283–1294. doi: 10.2134/jeq2013.01.0031

- Yin, R. 1994. Case Study Research, Design and Methods. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.