ABSTRACT

In this study, we explore the lived experiences of communities at the frontier of shale gas extraction in the United Kingdom. We ask: How do local people experience shale gas development? What narratives and reasoning do individuals use to explain their support, opposition or ambivalence to unconventional hydrocarbon developments? How do they understand their lived experiences changing over time, and what sorts of coping strategies do they rely upon? To do so, we draw insights from semi-structured interviews with 31 individuals in Lancashire, England, living or working near the only active shale gas extraction operation in the UK until the government moratorium was announced in December of 2019. Through these data, we identify several themes of negative experiences, including “horrendous” participation, community “abuse,” disillusionment and “disgust,” and earthquakes with the potential to “ruin” lives. We also identify themes of positive experiences emphasizing togetherness and community “gelling”, environmental “awareness,” everyday energy security with gas as a “bridging fuel,” and local employment with “high quality jobs.” Finally, we identify themes of ambivalent and temporally dynamic experiences with shale gas that move from neutral to negative regarding vehicle traffic, and neutral to positive regarding disgust with protesting behaviour and the diversion of community resources. Our study offers context to high level policy concerns and also humanizes community and resident experiences close to fracking sites.

1. Introduction

In this study, we explore the lived experience of communities at the frontier of shale gas extraction in the United Kingdom, including hydraulic fracturing or “fracking”. We ask: How do people in local areas experience shale gas development? What narratives and reasoning do individuals use to explain their support, opposition or shifting neutrality toward unconventional hydrocarbon developments? How do they understand their lived experiences changing over time, and what sorts of coping strategies do they rely upon?

So far, lively debate has occurred concerning shale gas development at the national (UK) policy level with research documenting prominent policy frames (Williams and Sovacool Citation2019; Nyberg, Wright, and Kirk Citation2018a, Citation2018b; Cotton, Rattle, and Van Alstine Citation2017; Bomberg Citation2017), the tumultuous history of policy and regulation (Priestley Citation2018; Whitton et al. Citation2017), and the framing and rhetorical devices used by media (Cotton et al. Citation2019). Within these debates, shale gas, and natural gas more broadly, remains contested by diverse publics who question its ability to deliver carbon emissions reductions (McGlade et al. Citation2018), enhanced energy security (Bradshaw Citation2018), jobs and community development (Szolucha Citation2019). Much work has also examined social attitudes, preferences, and beliefs about fracking, using case studies, media analysis, public inquiries, interviews with key policy actors and deliberative workshops (Evensen Citation2017; Neville et al. Citation2017; Williams et al. Citation2017; Howell Citation2018; Evensen Citation2018; Thomas et al. Citation2017). Looking at the international literature, research on citizen or social acceptance of fracking has typically focused on quantitative assessment, using large sample surveys (Boudet et al. Citation2016; Sherren et al. Citation2019; Lachapelle, Kiss, and Montpetit Citation2018; Brunner and Axsen Citation2020).

However, relatively less attention has examined in-depth the experiences of individuals living and working near unconventional hydrocarbon development sites. There are numerous exceptions that focus on the community responses to the early stages of shale gas development in the UK, often employing ethnographic approaches to do so (Beebeejaun Citation2017; Szolucha Citation2018a; Short and Szolucha Citation2019; Aryee et al. Citation2020). Collectively, these studies link many of the negative experiences of largely anti-development community members to the stresses and demands of participation in the planning system. Yet, community acceptance of shale gas remains the less examined of the three components of social acceptance of energy proposed by Wüstenhagen, Wolsink, and Bürer (Citation2007) – sociopolitical, community and market – with sociopolitical acceptance having received the most attention for shale gas to date (see especially Bomberg Citation2017; Cotton, Rattle, and Van Alstine Citation2017; Nyberg, Wright, and Kirk Citation2018a, Citation2018b; Williams and Sovacool Citation2019; Williams and Sovacool Citation2020).

This is a striking omission given Bradshaw and Waite’s (Citation2017, 35) assertion that local and community opposition to shale gas development “will continue to challenge the pace of exploration and will constrain the eventual level of production.” As Szolucha (Citation2018a) suggests, community attitudes, experiences, preferences, and identity could definitively shape the scope, scale, and desirability of fracking in the UK. With this in mind, and based on original community interviews near existing fracking sites in the UK, we explore negative, positive, and shifting neutral experiences with shale gas. Although our study adds support to many of the insights contained within existing literature regarding the negative experiences of anti-shale gas community members, we contribute new understanding of the more ambivalent and positive experiences related to shale gas development among community members in Lancashire. This region hosted the most active operational fracking site in the UK until a moratorium was announced in 2019.

Our primary contribution is to reveal the complex lived experiences in what has been an important frontier for shale gas development in Europe: Lancashire, UK. We contend that an emphasis on lived experiences has three advantages. First, it can help generate locally grounded and perceived depictions of community acceptance by capturing everyday encounters with shale gas infrastructure as felt by individuals in the most affected communities. Second, it can empower communities by presenting ideas and thoughts in their own words. Lastly, a lived experience focus shows the dynamism of views including how they change over time as well as how individuals can simultaneously hold seemingly contradictory viewpoints.

By attending to the lived experiences of shale gas development among Lancashire residents, our research sheds light on local concerns and also humanizes community and resident experiences close to fracking sites. This aspect of “humanizing” local experiences with energy systems and new innovations such as fracking specifically connects with recent calls to make energy studies research more receptive to the emotional, ethical, and moral dimensions to sociotechnical change (Jenkins, Sovacool, and McCauley Citation2018). In simpler terms, it is increasingly imperative to give more attention to the human experiences affected by the pursuit of certain technological pathways or technoeconomic paradigms. In the UK, state actors including those involved in environmental regulation, industrial policy and climate change have sought to promote UK shale development as an international “gold standard” for the industry, demonstrating that fracking can be done in an environmentally benign, community advantageous manner via processes of regulatory excellence (Williams and Sovacool Citation2019). In addition, both the UK industry body’s “Community Engagement Charter” (UKOOG Citation2013) and the government’s Shale Wealth Fund (HM Treasury Citation2017) aimed to ensure the benefits of shale gas reach local communities by sharing a proportion of tax revenues directly with local residents, royalty-sharing payments to councils and the local community (Neville et al. Citation2017), and £100,000 in community benefits per well-site where exploratory fracking takes place (Priestley Citation2018).

Given these and other efforts to make shale development palatable to host communities, examining the lived experiences of fracking in the North West of England (and beyond) considers host communities as an important domain in which government assertions about the risks and benefits of shale gas development are interpreted and given meaning, and it privileges the agency of individuals within that community.

2. Background and context

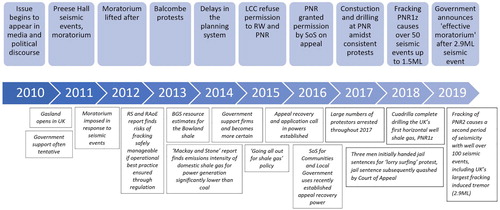

Shale gas development started to emerge as a public policy issue in UK media and political discourse after 2010 (Mazur Citation2016) and quickly gained a degree of public notoriety over the following year (see ). First, the Josh Fox film Gasland (Fox Citation2010) opened in the UK in January 2011. Outside of the US, a link to a copy or excerpt of the film Gasland on a video sharing platform was often among the first posts of nascent anti-fracking group websites (Wood Citation2012). This was followed by the company Cuadrilla causing a number of small seismic events whilst hydraulically fracturing at their Preese Hall exploration site in April and May of the same year. This seismicity at Preston New Road forced what was then the UK’s Department for Energy and Climate Change (DECC) to suspend hydraulic fracturing operations nationally. In September 2011, an example of early tentative Government support came from Minster of State for Energy and Climate Change Charles Hendry, who argued that “[t]he potential for unconventional gas is worth exploring because of the additional security of supply it could provide” (Hendry Citation2011).

Figure 1. A timeline of shale gas in the United Kingdom, 2010–2019. Source: Authors. LCC = Lancashire County Council. RS = Royal Society. RAoE = Royal Academy of Engineering. BGS = British Geological Survey. RW = Roseacre Wood. SoS = Secretary of State. ML = Local magnitude. PNR = Preston New Road. UK = United Kingdom.

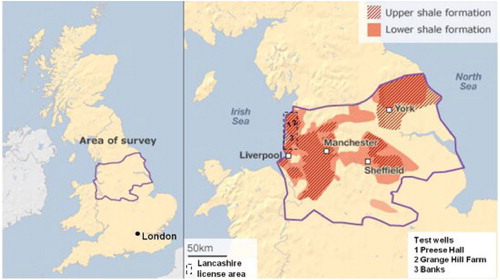

Much of the controversy over shale development in the UK has centred on fracking-induced seismic events, global climate impacts and community-level impacts. Following the government suspension on Cuadrilla’s drilling at its Preese Hall site, numerous studies investigating the risks of hydraulic fracturing in 2012 concluded the risks to be manageable (Green, Styles, and Baptie Citation2012; The Royal Society & Royal Academy of Engineering Citation2012), leading the government to lift its suspension in 2012 (DECC Citation2012). In 2013, the British Geological Survey (BGS) released a large resource estimate for the Bowland shale gas play (Andrews Citation2013), and the Mackay and Stone report found that electricity produced from domestic shale gas was likely to have an emissions intensity significantly lower than coal and comparable to conventional gas and imported LNG (Mackay and Stone Citation2013). shows the exploratory fracking site at Preston New Road, and where this site sits within the overall Bowland gas play.

Figure 3. Bowland Shale Gas “Play” In the United Kingdom with the Preese Hall Test Well (case study location) in the upper left box. Source: Cai and Ofterdinger (Citation2014). “Area of survey” refers to the demarcations of the shale gas play.

Over the summer of 2013, protests broke out over Cuadrilla’s shale oil exploration site in the Sussex village of Balcombe. These protests were instrumental in increasing public awareness over the shale development issue (Mazur Citation2016), and arguably turning the British public against shale development (O’Hara et al. Citation2016). Around this time Government rhetoric on shale development strengthened, best crystallized in Prime Minister David Cameron’s 2014 declaration that “we’re going all out for shale gas” (Watt Citation2014).

To jump-start UK shale developments slowed down by the planning system, the Government pursued a number of reforms. A new wave of shale exploration project applications, including Cuadrilla’s proposed sites at Preston New Road and Roseacre Wood, were held up by what the Government considered to be “disappointingly slow” decision making at the local level (BEIS Citation2018), with some questioning the viability of a UK industry without reform to the planning system (Pöyry Citation2014). To compound matters, Lancaster County Council refused permission to Cuadrilla for their sites in the summer of 2015. It was in this context that the Government pursued a number of planning reforms in order to speed-up the planning process for shale (DECC Citation2012; BEIS Citation2018). Furthermore, it was through these new powers that Preston New Road was eventually granted planning permission in 2016, with the Communities Secretary Sajid Javid overturning Lancaster County Council’s initial refusal on appeal.

Despite these efforts, UK unconventional hydrocarbon development continues to stall. In November, 2019, before a General Election in December, a moratorium was announced due to persistent seismicity at the company Cuadrilla’s Preston New Road shale gas exploratory site (BEIS and Oil and Gas Authority Citation2019).

3. Research design: “Lived experiences” in Fylde communities

Over the course of the above events, successive government surveys have documented declining public support for shale gas in the UK since 2014 alongside steady increases those who oppose shale gas development (BEIS Citation2019). Media attention has largely focused on protest events in the areas targeted for development, specifically mobilization against Cuadrilla’s operations in the Fylde region of Lancashire, often portraying community members and protestors monolithically opposed to shale gas. A “lived experiences approach” can shed light on how those who live and work in the communities directly impacted by shale gas development actually experience, interpret and make sense of events taking place where they live and work. In this section, we explain our conceptual framework for documenting and analysing “lived experiences,” before justifying our site selection and explaining our research methods.

3.1. Conceptualizing “lived experiences”

Lived experiences scholarship has its roots in various social science traditions, including sociological research, feminist studies and anthropology and is growing in psychology, medicine, public health and various policy-focused disciplines. Across these fields, a focus on lived experiences aims to better capture individual identities, narratives, and reasoning, recognizing the “ethnographically particular” nature of each person and offering an analytical lens that features the “experiential knowledge” of individuals and small groups (Rice et al. Citation2015). Like researchers of public attitudes towards emerging technologies who turn to narrative accounts as opposed to surveys to understand public reasoning about science and technology as practices ground in the “dialogic process of sense-making” (Macnaghten et al. Citation2019), the study of lived experiences is premised on the (particularly Western) assumption that individual experiences – no matter how contradictory – inherently have authenticity and therefore are a solid knowledge base (McIntosh and Wright Citation2019).

By grappling with multiple subjects’ accounts of their lives, “lived experiences” approaches offer researchers a window into the subjective experiences, identities, behaviours, norms and values that potentially give shape to collective experience. Moreover, as demonstrated in recent policy-focused studies, foregrounding lived experiences enables analysts to contrast the experience-based knowledge claims of members of community with the accuracy of larger top-down discourses and policy narratives targeting the community (see McIntosh and Wright Citation2019). The concept is akin to the emotional qualities of “sensemaking” from organizational sociology – the process through which people assign meaning to their collective experiences (Weick Citation1995; Maitlis et al. Citation2013) – but is applied at the community-level rather than the organizational. Lived experiences approaches also presume that there are multiple ways of knowing and that people may hold competing or contradictory positions about particular events or phenomenon.

Thus, the “lived experiences” approach provides an opportunity to build thick descriptions, empathize with the people affected by policy making and empower their experiences by making their concerns and emotions legible to decision-makers. Giving attention to the non-rational elements of behaviour often ignored by other modes of inquiry – such as those relying on quantitative methods to study public perceptions, support and opposition (Sovacool et al. Citation2018)–avoids reducing the public to the “tyranny of reason” or offering an artificial sense of objectivity. Experience is always something received through a person’s unique consciousness and mediated by various historical and cultural forces (Bruner Citation1986), including the “voice” of the interviewer (Macnagthen Citation1995). This makes experience something never completely knowable and shaped by interaction. For this reason, research must be firmly rooted in ethnographic approaches that demand the researchers examine their own subjectivity as physically, politically and historically conditioned (Ellis and Flaherty Citation1992; Finlay Citation2009).

The “lived experience” approach has been used sparingly in energy studies in a number of contexts, for example to examine fuel poverty among vulnerable groups (Middlemiss and Gillard Citation2015) or social housing tenants (Longhurst and Hargreaves Citation2019), energy poverty in Nepal (Herington and Malakar Citation2016), cobalt mining in the Congo (Sovacool Citation2019), energy-related mining in Wyoming (Rolston Citation2013a, Citation2013b) and the impacts of climate change (Harris Citation2017). We extend the concept to shale gas in the United Kingdom in order to generate insights into how individuals living and working near shale gas development sites make sense of government and industry actions, events and rhetoric.

3.2. Case study selection of Lancashire

We explore the lived experiences of a purposive sample of individuals in the Fylde region of Lancashire through qualitative semi-structured interviews conducted over the course of 2019. Some of these research participants constitute “campaigning publics” in the sense that they identify as participants in an organized collective that mobilizes around a shared view on a particular issue (see Mohr et al. Citation2013). Such collectives consider themselves to have a committed view on shale gas development and their members actively take part in various activities such as research, lobbying government and raising awareness amongst the broader public. Other interviewees have been less directly involved in local shale gas politics.

Our focus on the Fylde region of Lancashire reflects the area’s status as an “extreme case” (Flyvbjerg Citation2006), in the sense of being a rich source of information due to the area being the most active site of exploratory onshore unconventional hydrocarbon development in the UK. The company Cuadrilla has been actively exploring for unconventional hydrocarbons in the region for around a decade; in 2011 they conducted the first high-volume hydraulic fracturing operation in the UK at their Preese Hall site in the region. Their Preston New Road site remains the most ambitious exploratory shale gas site in the UK. Through these projects, communities in the Fylde have around 10 years’ experience of living with Cuadrilla’s pursuit of shale development, and campaigning and participating in decision-making processes through the planning system. As such, studying this region provides the best opportunity in the UK to assess local experiences related to shale development. Lancashire serves as “ground truth” for “academic research and opinion polls that describe the reasons for growing opposition to shale” (Bradshaw and Waite Citation2017: 34). Others have argued that the region serves as a barometer for shale gas development across all of Europe (Szolucha Citation2018a, Citation2018b), given that it was – for a time – the only location in Europe where new commercial exploration was underway (Bradshaw and Waite Citation2017).

3.3. Research methods

To collect original data, we relied on community interviews in the middle of 2019, which had the benefit of capturing experiences during exploratory fracking efforts at a time before the government announced a moratorium on November 4, 2019. We identified participants through snowball or chain recruitment, first inviting existing contacts in the area as well as individuals who had visibly campaigned on the issue (e.g. through speaking at planning events or writing letters to local newspapers) before broadening recruitment through referrals to additional potential interviewees. We attempted to ensure a balance of geographical locations and attitudes, although recruiting pro shale development participants proved more of a challenge. As can be seen in , this strategy resulted in a purposive or targeted sample of 31 interviewees, 22 of which identified themselves as anti shale development, 6 of which as pro shale development, and 3 of which as ambivalent.

Table 1. Community and regional interview sample.

As demonstrated in we intentionally sought balance across geographical zones – “rural Fylde”, “coastal Fylde”, and the “wider region”. Rural Fylde includes participants residing in the more rural, inland Fylde, including the parishes where the Preston New Road site is located and where the Roseacre site was proposed. Coastal Fylde is relatively urbanized, including the settlements of Lytham, Lytham St Annes and Blackpool. The rationale for including this zone was the suspicion, often raised by advocates of shale development, that shale development is viewed more favourably in these areas –especially in Blackpool. The presumed reasoning is that such regions are a bit further away from current sites and because promises of job opportunities and investment may resonate more strongly here than the more affluent rural areas with large numbers of retirees.

Our original data collection cuts across two different local authority areas. On the one hand, the Fylde district is one of the most affluent local authority areas in Lancashire, helped by the presence of high paying manufacturing jobs in the aerospace industry. The area also has the highest rate of second homes in Lancashire. Employment rates and average earnings are above the national average, life expectancy is similar to the national average and crime rates are the second lowest in Lancashire (see Lancashire County Council (LCC) Citation2020a). Households in the Fylde fall just below average for fuel poverty in England (approximately 10.2%). In contrast, Blackpool was ranked as the most deprived area in England by multiple measures in 2019, with 17.5% of households estimated to be in fuel poverty in 2017 (the highest rate in Lancashire and the 4th worst in England), a crime rate well in excess of the Lancashire average, and life expectancy lower than national averages. Indicators of income inequality reveal low rates of gross disposable household income and average earnings, with high levels of welfare dependency amongst the working age population compared to regional and national averages (see Lancashire County Council Citation2020b).

We cast a wider net in our recruitment by including participants from the region in and around Preston. Our rationale here reflects the “all affected principle” (see Goodin Citation2007) – an attempt within democratic theory to identify those whose views ought to be taken into account on the basis of whether they will be affected by the particular issues under consideration. Therefore, we also conducted interviews with people from areas reported to have felt seismicity from Preston New Road.

Our semi-structured interview protocol included questions about attitudes to and general perceptions of shale development; beliefs about impacts (local, national and global; actual and potential); views on governance, regulation and energy policy; and reactions to archetypal positions put forward in the shale development policy debate. In order to aid this final section we produced prompt materials. The prompts were designed to capture the essence and key claims of nine archetypal arguments for and against shale development, which previous research identifies as prominent within UK policy debates over shale development (Williams and Sovacool Citation2019). These prompts took the form of either direct quotes of government actors as reported in mainstream media or previous research, or a paraphrased summary of an archetypal position. Images from mainstream media reports were sometimes provided to support discussion. Participants were asked to familiarize themselves with each prompt and then asked whether they found the perspective expressed by the prompt compelling and why. Researchers audio recorded interviews with participants’ consent, transcribed and stored transcriptions in Nvivo 12 for analysis. These were subsequently analysed inductively in terms of the positive, negative and ambivalent qualities of participants’ lived experiences, in an effort to investigate the personal views and narratives underlying the “support”, “oppose” and “undecided” positions typically captured by survey data on public attitudes towards shale gas (e.g. the UK’s Public Attitude Tracker).

4. Results: the lived experiences of shale gas development in Lancashire

Researchers analysed interview data inductively to identify thematic patterns. The analysis revealed ten lived experience themes (), which are presented in three groups of generally positive, negative, and ambivalent sensibilities towards shale gas development. The category of dynamic ambivalence captures the shifting neutrality of participants who considered themselves to be neither wholly for or against and expressed more moderate feelings towards shale gas experiences. Many experiences expressed by these research subjects reflected an ambiguous and ambivalent middle ground, with some of these participants sometimes offering contradictory critiques that suggested more complex positionings.

Table 2. Summary of the Lived Experiences of Shale Gas in the United Kingdom.

Three complexities deserve to be mentioned when framing these results in . The first is that a distinction does exist between those that oppose shale gas in general, and those that oppose a particular site (e.g. because traffic route for construction and then operation was proposed to go past their house). The second is a distinction between real impacts, such as traffic impacts, induced seismicity, the need for police protection or feeling community tension in a pub; and potential or anticipated impacts, such as future jobs, and national energy security. The third is that many participants held mixed views and themselves oscillated between positive, negative, and neutral experiences. Put another way, even a single household or individual could have multiple and at times diverging lived experiences.

4.1. Negative lived experiences of horrendous participation, community divisions, disillusionment and vulnerability

This first collection of lived experiences all emphasize the downsides to fracking, including the material costs of participation in the planning process, impacts on families, feelings of despair, and the trauma of earthquakes.

4.1.1. “Horrendous” inquiries and collective trauma

Many participants expressed rather bitter experiences from attempting to oppose or support shale gas development by protesting or participating in the planning process. As Participant 14 (wider region, pro) claimed: “[Giving evidence at the public shale gas inquiry] was horrendous, absolutely horrendous” and “the worst thing I've ever endured … .” In some cases, participation led to a great deal of stress caused by financing legal fees and other work involved in organizing opposition through the planning system, with participants emphasizing material inequalities between various parties who participate in the planning system. As one person (Participant 4, Rural Fylde, anti) put it:

The effort to keep it [objecting to proposed sites through the planning system] going, [it requires far] more effort than you would think. I had a reasonably responsible job - putting things together for a public inquiry is as demanding as anything I've ever done. At that time we would perhaps have 100 emails unanswered each day at the height of it, 100 more that we'd skimmed through and actually needed. We were lucky that we had some bright people to put together some of these documents … Cuadrilla are paying I don't know hundreds of thousands of pounds, I'm sure it's literally hundreds of thousands to produce their documentation. If you go to a public inquiry you are expected to produce that type and that level of documentation to actually compete with them … I've fallen out with my wife and daughter about the amount of time that I've put in. Fighting a public inquiry is horrendous … So, the planning system is good but it's not, you know, for Joe Public to do it.

We had to engage experts to speak on our behalf [at the public inquiry] … [The] documentation was massive, because you've got to get all … witness - not witness statements, - proofs of evidence and all that. We had expert witnesses, we had a barrister who sort of spoke on our behalf. I mean getting all the documentation to Bristol [location of the Planning Inspectorate] you know was a big task for a little group because you had so many copies of all of the documents. So I think at one point I had 30 Lever Arch files full of documentation that we had to get from here to Bristol. It was a big ask. … When the outcome went against us we decided we'd go to judicial review. So again we engaged a legal team and went to judicial review. So went through that whole sort of getting the pieces of evidence, getting all the documentation. That went in March 2017 but we lost the judicial review. But we decided we'd appeal, so again we went to the Royal Courts of Justice with all the legal team, all the documentation. But we lost that as well.

I think it's hard for residents’ groups to actually take part in it properly because it takes quite a lot of getting your head round it. Our group of people aren't - we're not stupid … But I think it's not an easy process - if you haven't got the right people with the right skills it's quite hard. And also working out what the process is. I mean, we'd not been involved in a planning process before, so getting our head round whole the process, what happens next, what do you have to have submitted for when, you know, what are the deadlines. All that. It's quite hard if you've not been involved in it before, quite stressful. Especially when it comes to judicial reviews - you know, you suddenly think ‘well, we're taking the government to court’.

Participants also experienced personal emotional and psychological stress through participation. For instance, Participant 10 (rural Fylde, anti) likened their experience with the shale gas planning process as an “emotional rollercoaster” that has “impacted my role as a mother and a wife,” going on to say:

It completely took my life over yeah, and I was stressy [sic] and it's completely affected me. You know when they started fracking and when there's been big decisions made against us and even for us, it's like an emotional rollercoaster. No one will understand how much it's affected us. It's been horrible.

4.1.2. Community divisions, “abuse” and “threats”

Some participants reported experiences of physical risk and intimidation when attending planning hearings and inquiries, in some cases even needing police protection. One person (Participant 14, Wider region, pro) stated that they were shoved, pushed, and bullied by fellow community members for their views on shale gas after giving evidence at a public shale gas inquiry:

All I did was give evidence from … [a] business perspective and I came out and the police said you need protection. I said I don't need protection I've lived in Lancashire all my life, nobody's gonna harm me here … And then of course they all started coming over and pushing me and shoving me and bullying me, and I'm like I wouldn't do that to you about this, do you know what, if you've got your beliefs you're entitled to them, but why are you starting to want to change my beliefs.

Even with a private escort taking us into the county court, people came up to [me] - and it's frightening - and I don't frighten easy. People come right into your face hurling abuse at you and you can't touch them and neither can the security man with you.

I don't often go out but in the pub down the road from where I live there's - yeah, you can tell there's a split. You know, people don't know anything about it and then they'll say ‘you're not an anti-fracker?’. And I say well why - why do you like fracking? And they give all that rubbish you know about getting loads of gas off Russia.

There's no having a discussion with them [anti-frackers] - they are completely blinkered [English term for having a limited outlook] and they are aggressive. I mean I've had, I can't tell you how many abusive and threatening emails I've had … There's no discussion to be had at all and that's a shame because it needed to be discussed but when there is objectors doing what they're doing. You know, rushing in, shouting and bawling, screaming, being abusive, being offensive, being aggressive, that ends any proper serious discussion which is such a shame.

So the farmer who agreed to let the frackers on the field is sort of ostracized. So in some ways it's split families because there's like one farmer who has a brother or sister, so half of the family is against it and giving evidence at the inspector’s inquiry and the other half are for it because they're going to make some money out of it … it's caused a lot of stress in the community, a lot.

And this northern powerhouse thing. I just think it’s just another reason, another ball thrown in the park for us to be doing it. It’s cynical as well. ‘If you don’t vote for this, then you’re not supporting the communities that you live in.’ It’s starting to play a divisive tap tap tap [knocking on the table]: ‘maybe we should be doing that, maybe they’re right.’

You've got people constantly complaining about the protestors and what is the point, they're all just dirty scumbags, you know, hippies, and they all ought to go home and they're never gonna stop this sort of thing.

4.1.3. Disillusionment, disenfranchisement and “disgust”

Interviewees shared feelings of disillusionment and political disenfranchisement not only with the planning process but with democratic decision-making and the notion of scientific truth more broadly. The participants’ remarks in this section point to the internalization of negative emotions about shale gas and the planning process in ways that re-shaped their world views, with one person noting their shale gas experience had changed their faith in democracy. Much of this relates specifically to the central government’s overturning of the Lancaster Council’s refusal to grant planning permission to Cuadrilla for its Preston New Road site. As Participant 10 (rural Fylde, anti) shared, “I think it's disgusting what the central government has done [overturning the Council’s decision],” and went on to describe an experience of disenfranchisement:

It's changed me completely as a person … It's completely changed my whole outlook on everything. The way [the government has] treated the Fylde is terrible … What's the point? What's the point of all the time and effort that everyone's put in?

Oh we’re going to bridge this gap, is the rhetoric that, we talk about Russia, and obviously energy security in any form or fashion, but there are other ways you can look at energy security. It’s being sold. It kind of reminds me of Petro chemical and cigarette companies. I had that feeling. That’s how I absorb the positive spin in term of what they do on shale gas. That makes me uneasy.

I don’t see why these applications to relax some of the regulation around tremors, when they keep having to stop drilling, I’ve heard on the news a few times that they’ve stopped drilling a lot, where the government overrode the council, and there’s people at Caudrilla complaining and lobbying for the rules and the regulations to be relaxed. Well, if it’s as great as you said, then why do we then have to move the goalposts [to change seismicity regulations]?

One of the difficulties now is that there's no chance of finding any truth out there now. The “antis” are over everything and I'm sure - as I say some of what they say is true - but there's a lot of misrepresentation and downright lies I have to say … I think now if somebody became interested in this area now, just as a layman, finding any sort of true information is so difficult, so difficult.

4.1.4. New vulnerabilities, earthquakes and “ruining” lives

A final set of participants framed their shale gas experience in fearful terms, as issues of health and safety risks or economic loss, with some even considering to leave the community and never return. One person (Participant 10, rural Fylde, anti) described their home and surrounding areas as becoming unlivable due to perception of increased levels of risk from shale gas development:

There's so many licenses up for sale across swathes of the country that it's not just gonna be my family affected, there's people gonna be getting ill. And it's proven this is, it's not scaremongering. It's happened, I've researched it, I've spent hours and hours researching it. And people a certain radius away from the well site get ill, that's fact. So, yeah, I don't agree with it in any way. We were gonna move. Do you know when the first day that they started fracking, I pulled my [child] out of college … we were gonna move and then the earthquakes started and I thought I'm just gonna leave it for a bit and see what happens … So we didn't move. It was horrible, I was in a right mess. No one understands how much stress you're going through. It's completely, it's ruined my life for quite a few years, that's all that's been on my mind. It's got better now because there's nothing on site, but you know if there's a bang or something I think oh my god and I always look at my chandelier to see if it's shakes or whatever, I think is it an earthquake. It's affected me, it's definitely affected me.

I felt the earthquake at Preese Hall, yeah. … It's absolutely not acceptable. Cuadrilla helped them set that limit and Francis Egan [chief executive of Cuadrilla] said there wouldn't be any above 0.5 [local magnitude]. They don't know what they're doing, they're incompetent in my opinion. Nothing will make me feel safe about this, I don't want it here full stop.

Not long after they started protesting the motorway was shut because there was a big accident on the motorway which meant all the traffic was diverted down past the fracking site but then that road was closed because the anti-frackers were in the road and it resulted in … I think a number of people couldn't get to hospital. I think a gentleman had a heart attack, another lady gave birth on the side of the road down a side lane. The havoc it caused, and I think that almost bought it to a head really in terms of not supporting the … protestors because the level of disruption they were causing to local people was just massive.

People’s nerves have been frayed because it would just affect their lifestyle so much. For instance, one of my [children] lives quite close to the proposed fracking site at Roseacre. [They] would have had to move for the sake of the kids and [their] own health and would have moved. So that would have meant they were bankrupt because nobody would have bought the house they’d have had to walk away. So they spent the last I think 4 years just worried, really worried, fighting it. With everybody telling us oh we’d get nowhere, it’ll still go ahead because government were in favor of it and it was big business.

According to this collection of experiences, the introduction of shale gas has introduced new compelling vulnerabilities such as earthquakes and concerns over safety and health that even have some community members pulling children out of school or contemplating leaving the area and selling their homes.

4.2. Positive lived experiences of selective cohesion, enhanced environmental awareness, everyday energy security and local labour landscapes

Alongside the above negative experiences, some participants recalled lived experiences of shale gas development that entailed feeling a stronger sense of community and developing greater environmental awareness, the potential for energy security and new economic opportunities.

4.2.1. Social cohesion and “gelling” together community factions

Many participants indicated a collective lived experience in which some community members built social cohesion (Maxwell Citation1996) by affirming shared values and interpretations of shale gas development. The simultaneous sense of division described earlier reinforces this view, as it underscores that those working together toward the same aim (i.e. to support or oppose shale development) forged stronger bonds.

As one person (Participant 3, Rural Fylde, anti) explained, “I think it’s [shale gas] gelled the community together.” Another (Participant 7, Fylde coast, anti) likened their experience to finding a new family and a stronger sense of community:

So getting to know all the people, networking with all the people … So it almost creates a large … extra family [that helps to] not feel quite so isolated … For some people you get to a point where you go ‘well I have to protest’. I've got to that point where you know I'm still emailing, still signing petitions, still writing, still doing all those sorts of things. It [protesting] may be really small and seem quite meaningless to a lot of people but yeah it's that coming together with people … I'm thankful almost that this industry's woke me up to the fact that you can create strong communities within those things.

4.2.3. Enhanced environmental “awareness”

This collection of lived experiences centres on the increased environmental and social awareness that living near shale gas precipitated for some. As one participant (Participant 11, Rural Fylde, anti) put it, this awareness generated a new appreciation for both local and global dimensions of climate change:

The thing that's changed dramatically would be the climate change, with the growing awareness of climate change and it's made us more aware about fossil fuel extraction. So that to me is where perceptions [have] changed a bit. So it's moved more from local issues affecting communities directly to issues that are affecting the planet. So it's the wider issues, I would say, that we're more conscious of, more aware of the environment and then all the issues [are part of] the whole package really.

In terms of potential benefits, has it created some community cohesion in terms of its getting bits of Fylde and bits of international Green party, and bits of Blackpool bothered and interested in the environment? Then yes potentially, so there might be some positives from it as well.

4.2.3. Everyday energy security and gas as a “bridging fuel”

Whilst energy security is often considered a rather abstract, distant issue for people “on the ground” to take interest in, it is worth noting than some participants who supported shale gas development translated the narrative of anticipated energy security benefits into a local and personal experience. As one person (Participant 20, Fylde coast, pro) noted, shale gas figured into a larger need to keep the incumbent gas infrastructure flowing in a region where old housing stock and fuel poverty could make for miserable winters:

Now as long as this can be done responsibly and with as little detrimental impact on the environment as possible, my view was that we've at least got to investigate our options and I'm also a realist. You know, we are very greedy - we live in a very greedy society and as much as there is all this talk about climate change - which we absolutely have to address and all those kinds of things - people are not gonna turn their central heating off in the winter.

I think most people misunderstand the people that support this industry in the sense that they think they're sort of diehard hydrocarbon users but I think … there's probably got to be a half-way house leading towards something that's probably more environmentally friendly but you have to get there don't you, it's a journey, you can't switch off the lights overnight can you. You know, England's not going to survive on wind and solar power tomorrow morning when we all wake up.

My view is for 20 years or so gas will be the bridging fuel - I know plastics got a bad name but you need it for plastics and a lot of chemical production as well. The sheer logistics - how many homes in the UK are heated or cook by gas? You can't change that overnight. And even if you just relied on what gas we produce you wouldn't be able to bridge that gap without importing in the short term.

4.2.4. Economic anxieties and grounded expectations for “high quality jobs”

Many participants shared their experience-based expectations for how the economic dividends of a future shale gas boom would spread within local communities. In discussing future potential economic benefits promised by government officials and industry leaders, participants often qualified job creation claims targeting Lancashire communities as needing to be substantiated by local knowledge of the region’s broader labour landscape. As one person (Participant 24, Fylde coast, pro) reflected, the majority of new economic opportunities would likely fall in the service and regulatory compliance sector, despite the attention to job creation in the oil and gas sector:

For somewhere like this area, if we had 1,500 jobs related to an industry, it's not about, it wouldn't really be about the exploitation of the gas – that would be specialists largely – but about the management of it, the sales, the brokering, the administration, the health and safety checks, the environmental monitoring, that number of higher quality jobs in this area would make a vast impact [on the area].

We walk a double-edged sword. Half of the time we are ‘Blackpool is absolutely fabulous, it's the best place on earth, come for your holidays, have a great time, all is wonderful.’ And we have to do that because the biggest employment is tourism. So, we need the tourists to come to keep the jobs going, keep our people in employment. But then … we have some of the worst statistics in the country. Child poverty is 42%, which shames me to say, in one ward in Blackpool. So, we have real serious deprivation and issues. So, take that on board. Then take on board that we have lost … I think it’s about 15,000 full time quality jobs in the public sector … We've lost our department of works and pensions, we've lost our land registry and we've lost NSI [NS&I - National Savings and Investments, a state-owned savings bank] … We've lost all those quality full time jobs. And unfortunately with tourism, the downside of that is a lot of those jobs are seasonal and a lot are mid- to low-income. So, we need jobs, it's that simple, we need jobs for me.

When I talk about jobs I'm fully aware that there aren't that many full time jobs on the well site but already - have you got the figures of how much Cuadrilla have spent in the local area? … They have spent quite a few million in this area, so they’ve got offices so obviously they've got quite a few staff in there, but they've also got cleaners, and any site needs fences, signage, sand. And they've promised that they will use local suppliers.

But more than that, a big part of this for me again was that if we could be the first - we've now opened up in the last year a new energy college on the enterprise zone area there, on the airport area, which is not just gonna be about this, it's gonna be about all sorts of energy onshore, offshore, wind, all those kinds of things. So, it is about becoming a center of excellence if you will. So that people could come in and learn.

4.3. Dynamic ambivalence in the lived experiences of anti-fracking protests

Participants who initially characterized their position as ambivalent went on to share more variable positionings that do not suggest confusion or lack of understanding of the situation at hand, but rather indicate the complexity involved in grappling with how shale gas development contributes to, or conflicts with, their culturally embedded aspirations.

4.3.1. Living with contingency, seeking out science and “selling by fear”

As previously indicated, for many research participants, shale gas development promised tangible benefits, the value of which remained contingent on how shale gas development would play out. For instance, Participant 26 (rural Fylde, ambivalent) commended the opportunities tied to the new energy college as an overwhelmingly positive development. Yet, they also implicitly questioned whether new shale gas wealth would flow where it was most needed: in support of local safety nets for socially deprived populations who endure the cumulative burdens of adverse health risks, poverty and poor access to energy and energy efficiency retrofits, all of which can worsen in colder months:

So, what I would like to see is if some of that resource goes into gaps that we have to make houses on the Fylde coast and particularly Blackpool carbon-neutral, or basically not leaking energy. Our housing stock is some of the worst in the country. It’s very expensive to retrofit to make warm. […] So, what I would like to see is some of that money be reinvested to reducing energy costs to our the most vulnerable households.

In other instances, participants who firmly identified as “anti-” early on in the interview later expressed ambivalence from not feeling not wholly aligned with all facets of anti-shale gas advocacy due to a perceived lack of conclusive scientific backing by those opposed to shale gas development. As illustrated in , anti-fracking signs placed at the Cuadrilla site and throughout the community by protestors provided constant visual reminders about the risks of fracking, with some signs going so far as to present copies of scientific papers on the environmental and public health effects of fracking in the US.

Figure 4. Anti-fracking signs at the junction of the A583 and Moss House Lane, near Cuadrilla’s Preston New Road site, April 2019.

Yet some interviewees questioned the substance of protestors’ arguments, revealing that even those who opposed shale gas questioned the validity of some of protestors’ critiques of shale gas development. This was largely due to the perception that key arguments lacked conclusive scientific evidence on certain environmental risks. Participant 27 (rural Fylde, anti) expressed disappointment and resignation about the deep-seated divisions that had emerged around issues for which there appeared to be no clear authoritative answers from experts, concluding, “I don’t think anybody knows if we should be doing this or not, whether it’s a good thing or not, how long the gas will be there or not.” Another participant (28, rural Fylde, anti) believed that a lack of scientific certainty pertaining to the risks of fracking had led anti-shale gas voices to succumb to a disingenuous strategy of “selling by fear” in which they inappropriately extrapolated scientific findings from the US to the UK, downplaying industry rebuttal to promote anti-shale gas views, which led this participant to call for more “balanced” claims:

If we’re so different [than the US], then some of these certainties against how it’s done in America, there’s obviously going to be a difference. I would say, although it’s the side I believe in, it’s selling by fear for the side that I agree with. That’s all happened somewhere else. It might happen here. But I think that could be worded … in a more balanced way. […] Because … the other side’s saying, well you’ve watched a video on YouTube from 15 years ago and they say in America they’ve been doing it for 25 years and that was the only time flames came out the water tap.

The first reaction [I had to shale gas] was probably positive because it felt like it was going to increase local employment, investment. Then some of the negative press was coming out. So I suppose I was probably a bit sceptical then about the impact. But in honesty, as more of the argument for the negative protesting got louder, I was less convinced by the protestors if I’m honest with you because it felt like it had been overtaken by almost professional campaigners and I felt as though it was just an agenda. They were just anti-fracking without necessarily putting out a lot of evidence to support it … I probably felt actually, as long as there's safeguards and monitoring in place then actually, is it likely to lead to something that's gonna cause the long term problems that we were talking about?

4.3.2 Weighing protest disturbances and “diverted” community resources

For some participants, positions changed over time, as new experiences related to the protestors at Cuadrilla’s proposed fracking sites shifted interpretation, leading to more nuanced stances. For instance, two participants explained they were first ambivalent about shale gas and later turned against a proposed site once they realized it would route traffic near their house creating congestion. As Participant 17 (rural Fylde, ambivalent) explained:

We were quite neutral [to shale gas] because we lived in [town], which is a bit further away, until last year so we only moved into the area last year. And I suppose really last year we probably had a more negative view because the route for the traffic was planning to come down the road which would’ve come past the house that we bought … So we probably changed [our view].

Yeah, [for me it was] slightly more to do with the vehicles going past the house, as I say the lorries, and whether you wanted the volume of traffic as opposed to whether or not fracking is harmful to the environment … The first time I remember being somewhat inconvenienced by it was when the road kept getting shut with the protestors and it was just causing a nightmare getting to work, that was probably the main memory I've got of it.

For some ambivalent participants, more positive reactions to shale development formed in relation to frustrations with the anti-fracking protest movement on the grounds that protestors were “wasting” community resources. At various points, Participant 26 (rural Fylde, ambivalent) asserted the presence of protestors was not only inconvenient but also a burden on public resources:

The cost of providing police support with all the protest, the inconvenience of the protester people traveling around Blackpool is massive. [The] traffic and the 20 miles per hour zone [have negatively] impacted normal daily living around Blackpool. And the schools in Blackpool as well, because a lot of the protesters are not from Blackpool but bring children into the school system.

The protestors have created a lot of negativity on themselves and the kind of disruption they've caused, if I'm honest. I don't think there's many people that talk positively and support … what they do. Because I think the inconvenience that they cause tend to be on the local people as opposed to the fracking industry itself. You know, I think the cost of the policing, which central governments weren't happy to kind of contribute towards and things like that has caused quite a lot of ill feeling …

The police costs were significant and we [know some police officers] and the amount that they were being pulled away from policing the local community just felt ridiculous you know. Which wasn't either Cuadrilla or the protestor's fault necessarily, maybe that was central government should have stepped in but that probably left an anti-protest feel to it as though, well ok you're arguing about the inconvenience this would cause to the community but you're actually imposing such an inconvenience now …

These ambivalent yet dynamic experiences underscore the diversity of interpretations of aggressive campaigning tactics, from harming the credibility of “anti-shale” protestors, to raising concerns over community membership, to inspiring solidarity from otherwise shale-sympathetic actors. More broadly, our observations mirror the findings of energy transitions research which similarly shows that there are multiple mechanisms at work when people construct ambivalent attitudes towards energy or new technologies (Scheer et al. Citation2017). Furthermore, as Macnaghten (Citation1995) argues in a case study of the attitudes of residents in Lancashire towards competing policy proposals, what initially appears to be contradiction or confusion may be, upon closer inspection, signposts of a “moral geography” rooted in historical conflicts that is often intangible to policymakers and regulators. The shifting views towards protestors and shale gas developers described in this final collection of experiences reflects how perceptions are built from multi-faceted collective anxieties about local representation in both local government and the protest movement, about waning control over local public resources and the quality of one’s own local experience, as well as about the failure of scientific experts to resolve the debates fuelling divisions over shale gas.

5. Conclusion and policy implications

This article’s examination of the lived experiences of shale gas development in the United Kingdom – at a site once poised to shape the industry’s future across Europe – reveals a community laden with myopic, partial, emotional, considered, contrasting, convergent, and dynamic perspectives. Many participants offered positions and opinions about shale gas development that were rooted in their feelings towards events and people, their ethics, and their historical experience of material and somatic impacts, without recourse to definitive scientific evidence. In examining the emotional aspects of lived experiences as well as the many non-economic or non-rational logics at play in shaping individual perspectives in Lancashire, we offer a set of highly personal perspectives. Read together, this collection of lived experiences points to numerous potential patterns in collective experience that can inform future research and policy.

Negative lived experiences related to participation in the planning process reinforces our awareness of the high price of entry and participation for many households interested in participating in energy democracy, as well as the cynicism left in the wake of shale gas pursuits. Those who experienced planning processes for shale gas as “horrendous” relayed the great personal or economic costs sustained in participating in public inquiries, the painful and frustrating divisions within Fylde communities resulting from the engagement in planning and protests, and deep disenfranchisement and disillusionment with democratic process, government officials and industry actors and scientific truths. In addition, people concerned about earthquakes and the potentially long-lasting impacts on community health reported experiencing significant fear, stress, and anxiety, and for some this was cause enough to take action towards voluntary relocation.

Our findings also suggest there is less pronounced but equally insightful set of positive lived experiences concerning the (largely anticipated) benefits of shale gas development. Both pro- and anti-shale gas research participants spoke of a sense of social cohesion emerging within their respective campaigning communities. Moreover, the enhanced awareness of national energy or environmental issues, and the potential for local investment and job creation in a region perceived to be “left behind” suggests that local lived experiences of shale gas development in Lancashire have produced new networked relations. Both of these sets of experiences underscore the potential for community divisions to generate new coalitions that may exercise influence over future energy policy decisions.

Furthermore, our findings speak to the broader set of tools and approaches that social science researchers draw upon to study communities in energy politics, especially when government and industry agendas are strongly contested by local residents. Research tools used to gauge public knowledge, attitudes or preferences such as surveys or other stated preference techniques, often assume research subjects’ positions can be “known” beforehand. The neutral and mixed viewpoints that this research highlights reminds us that opinions are not static and people are capable of holding seemingly contradictory viewpoints at the same time. Some shale gas preferences must be discovered through a process of experience, rather than known or predetermined in advance.

An additional contribution is that the study illuminates how energy transitions, in this case manifested through the potential community impacts of adopting shale gas, have not only material impacts on infrastructure (e.g. roads, traffic, earthquakes) and social impacts on communities (awareness, community tension), but emotional impacts. These include feelings of trauma, abuse, fear, vulnerability, cohesion, security, and ambivalence, and they remind us about some of the less tangible logics that shape community-level responses to decisions about energy systems. Some of these feelings – especially those emerging from negative experiences of trauma and abuse as well as the dynamic ambivalence people experience towards both shale developers and protestors – offer a potentially stark harbinger of the costs of community participation in energy decision-making fora like the planning system that has relevance for other conflicts on the horizon concerning local control of land, resources and infrastructure siting.

Finally, attending to lived experiences in shale gas social science research – in the UK and beyond – requires deeper exploration into how and why people come to hold the beliefs and preferences they do. Lived experiences offers a framework for comprehending how and why communities respond to controversial energy developments that can be integrated with other methods. Revealing the human motivations, trauma, stress, anxieties, fears and satisfactions of people living on the front line of shale gas development can help to empower overlooked voices and perspectives. Making diverse lived experiences accessible to decision-makers as well as other stakeholders – including local residents, advocacy groups and industry actors – helps ensure shale gas policies and planning respond to motivations as diverse as wanting to participate in public processes without feeling victimized, living through the trauma and stress of seismic events, coping with social divisions, becoming more conscious and aware of environmental or sustainability concerns, and fusing government promises for a better economic future with local expectations and desires. Policy and research efforts that fail to appreciate these dynamic perspectives risk reducing the public – especially host communities – to passive rational actors whose reasoning rests on the receipt of information, rather than potent feelings and experiences rooted in local cultural distinctiveness.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank our interviewees for their generosity and valuable contributions, as well as Professor Andy Stirling from the University of Sussex and Professor Nick Pidgeon from Cardiff University for helpful comments on earlier drafts.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Andrews, I. J. 2013. The Carboniferous Bowland Shale Gas Study: Geology and Resource Estimation. London: British Geological Survey for Department of Energy and Climate Change.

- Aryee, Feizel, Anna Szolucha, Paul B. Stretesky, Damien Short, Michael A. Long, Liesel A. Ritchie, and Duane A. Gill. 2020. “Shale Gas Development and Community Distress: Evidence from England.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17 (14): 5069. doi:10.3390/ijerph17145069.

- Beebeejaun, Y. 2017. “Exploring the Intersections Between Local Knowledge and Environmental Regulation: A Study of Shale Gas Extraction in Texas and Lancashire.” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 35 (3): 417–433. doi:10.1177/0263774X16664905.

- BEIS. 2018. Energy Policy: Written Statement - HCWS690. London: BEIS.

- BEIS. 2019. Public Attitudes Tracker, March 2019, Wave 29. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/800429/BEIS_Public_Attitudes_Tracker_-_Wave_29_-_key_findings.pdf.

- Bomberg, Elizabeth. 2017. “Shale We Drill? Discourse Dynamics in UK Fracking Debates.” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 19 (1): 72–88. doi:10.1080/1523908X.2015.1053111.

- Boudet, H., D. Bugden, C. Zanocco, and E. Maibach. 2016. “The Effect of Industry Activities on Public Support for ‘Fracking’.” Environmental Politics 25 (4): 593–612.

- Bradshaw, Michael. 2018. Future UK Gas Security: A Position Paper. Warwick Business School and UKERC.

- Bradshaw, Michael J., and Catherine Waite. 2017. “Learning from Lancashire: Exploring the Contours of the Shale Gas Conflict in England.” Global Environmental Change 47: 28–36.

- Bruner, E. M. 1986. “Experience and its Expressions.” In The Anthropology of Experience, edited by V. Turner and E. M. Bruner, 50–77. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

- Brunner, Todd, and Jonn Axsen. 2020. “Oil Sands, Pipelines and Fracking: Citizen Acceptance of Unconventional Fossil Fuel Development and Infrastructure in Canada.” Energy Research & Social Science 67: 101511. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2020.101511.

- Cai, Zuansi, and Ulrich Ofterdinger. 2014. “Numerical Assessment of Potential Impacts of Hydraulically Fractured Bowland Shale on Overlying Aquifers.” Water Resources Research 50 (7): 6236–6259. doi:10.1002/2013WR014943.

- Cotton, Matthew, Imogen Rattle, and James Van Alstine. 2017. “Shale gas Policy in the United Kingdom: An Argumentative Discourse Analysis.” Energy Policy 73: 427–438.

- Cotton, Matthew, Ralf Barkemeyer, Barbara Renzi, and Giulio Napolitano. 2019. “Fracking and Metaphor: Analysing Newspaper Discourse in the USA, Australia and the United Kingdom.” Ecological Economics 166: 106426. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2019.106426.

- DECC. 2012. Written Ministerial Statement by Edward Davey: Exploration for Shale Gas. London: DECC.

- de Rijke, Kim. 2013. “The Agri-Gas Fields of Australia: Black Soil, Food, and Unconventional Gas.” Culture, Agriculture, Food and Environment 35 (1): 41–53. doi:10.1111/cuag.12004.

- Ellis, Carolyn, and Michael G. Flaherty. 1992. “An Agenda for the Interpretation of Lived Experience.” In Investigating Subjectivity: Research on Lived Experiences, edited by Carolyn Ellis and Michael G. Flaherty, 1–13. London: Sage.

- Evensen, Darrick, Richard Stedman, Sarah O’Hara, Mathew Humphrey, and Jessica Andersson-Hudson. 2017. “Variation in Beliefs About ‘Fracking’ between the UK and US.” Environmental Research Letters 12: 124004.

- Evensen, Darrick. 2018. “Review of Shale Gas Social Science in the United Kingdom, 2013–2018.” The Extractive Industries and Society 5 (4): 691–698.

- Finlay, Linda. 2009. “Exploring Lived Experience: Principles and Practice of Phenomenological Research.” International Journal of Therapy and Rehabilitation 16 (9): 474–481. doi:10.12968/ijtr.2009.16.9.43765.

- Flyvbjerg, B. 2006. “Five Misunderstandings About Case-Study Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 12 (2): 219–245.

- Fox, Josh. 2010. Gasland. New York: New Video Group.

- Goodin, Robert E. 2007. “Enfranchising All Affected Interests, and Its Alternatives.” Philosophy and Public Affairs 35 (1): 40–68.

- Green, Christopher, Peter Styles, and Brian Baptie. 2012. “Preese Hall Shale Gas Fracturing: Review and Recomendations for Induced Seismic Mitigation.” https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/48330/5055-preese-hall-shale-gas-fracturing-review-and-recomm.pdf.

- Grubert, Emily, and Whiteny Skinner. 2017. “A Town Divided: Community Values and Attitudes Towards Coal Seam Gas Development in Gloucester, Australia.” Energy Research & Social Science 30: 43–52.

- Harris, Dylan M. September 2017. “Telling the Story of Climate Change: Geologic Imagination, Praxis, and Policy.” Energy Research & Social Science 31: 179–183.

- Hendry, Charles. 2011. “The Potential for Shale Gas Is Worth Exploration.” The Guardian, September 22. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2011/sep/22/shale-gas-exploration.

- Herington, M. J., and Y. Malakar. November 2016. “Who is Energy Poor? Revisiting Energy (in)Security in the Case of Nepal.” Energy Research & Social Science 21: 49–53.

- HM Treasury. 2017. Shale Wealth Fund: Response to the Consultation. London: HM Treasury. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/658793/shale_wealth_fund_response_web.pdf.

- Howell, R. A. 2018. “UK Public Beliefs About Fracking and Effects of Knowledge on Beliefs and Support: A Problem for Shale Gas Policy.” Energy Policy 113: 721–730.

- Jenkins, Kirsten, Benjamin K. Sovacool, and Darren McCauley. 2018. “Humanizing Sociotechnical Transitions Through Energy Justice: An Ethical Framework for Global Transformative Change.” Energy Policy 117: 66–74.

- Lachapelle, E., S. Kiss, and É. Montpetit. 2018. “Public Perceptions of Hydraulic Fracturing (Fracking) in Canada: Economic Nationalism, Issue Familiarity, and Cultural Bias.” The Extractive Industries and Society 5 (4): 634–647.

- LCC. 2020a. “Fylde District.” https://www.lancashire.gov.uk/lancashire-insight/area-profiles/local-authority-profiles/fylde-district/

- LCC. 2020b. “Blackpool Unitary.” https://www.lancashire.gov.uk/lancashire-insight/area-profiles/local-authority-profiles/blackpool-uni.

- Longhurst, Noel, and Tom Hargreaves. 2019. “Emotions and Fuel Poverty: The Lived Experience of Social Housing Tenants in the United Kingdom.” Energy Research & Social Science 56: 101207. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2019.05.017.

- Mackay, David, and Timothy Stone. 2013. Potential Greenhouse Gas Emission Associated with Shale Gas Extraction and Use. London: Department of Energy & Climate Change.

- MacNaghten, Phil. 1995. “Public Attitudes to Countryside Leisure: A Case Study on Ambivalence.” Journal of Rural Studies 11 (2): 135–147.

- Macnaghten, Phil, Sarah R. Davies, and Matthew Kearnes. 2019. “Understanding Public Responses to Emerging Technologies: A Narrative Approach.” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 21 (5): 504–518. doi:10.1080/1523908X.2015.1053110.

- Macnaghten, Phil, Robin Grove-White, Michael Jacobs, and Brian Wynne. 1995. Public Perceptions and Sustainability in Lancashire: Indicators, Institutions and Participation. Center for the Study of Environmental Change, Lancaster University, commissioned by Lancashire County Council.

- Maitlis, S., T. J. Vogus, and T. B. Lawrence. 2013. “Sensemaking and Emotion in Organizations.” Organizational Psychology Review 3 (3): 222–247.

- Maxwell, Judith. 1996. Social Dimensions of Economic Growth. Department of Economics, University of Alberta: The Eric John Hanson Memorial Lecture Series, Volume VIII, January.

- Mazur, Allan. 2016. “How Did the Fracking Controversy Emerge in the Period 2010-2012?.” Public Understanding of Science 25 (2): 207–222.

- McGlade, Christopher, Steve Pye, Paul Ekins, Michael Bradshaw, and Jim Watson. 2018. “The Future Role of Natural Gas in the UK: A Bridge to Nowhere?” Energy Policy 113: 454–465.

- McIntosh, I., and S. Wright. 2019. “Exploring What the Notion of Lived Experience Might Offer for Social Policy Analysis.” Journal of Social Policy 48 (3): 449–467.

- Middlemiss, Lucie, and Ross Gillard. March 2015. “Fuel Poverty from the Bottom-up: Characterising Household Energy Vulnerability Through the Lived Experience of the Fuel Poor.” Energy Research & Social Science 6: 146–154.

- Mohr, A., S. Raman, and B. Gibbs. 2013. Which publics? When? Exploring The Policy Potential Of Involving Different Publics In Dialogue Around Science And Technology. Didcot: Sciencewise.

- Morrone, Michele, Amy E. Chadwich, and Natalie Kruse. 2015. “A Community Divided: Hydraulic Fracturing in Rural Appalachia.” Journal of Appalachian Studies 21 (2) (Fall 2015): 207–228.

- Neville, K. J., J. Baka, S. Gamper-Rabindran, K. Bakker, S. Andreasson, A. Vengosh, A. Lin, J. N. Singh, and E. Weinthal. October 17, 2017. “Debating Unconventional Energy: Social, Political, and Economic Implications.” Annual Review of Environment and Resources 42 (1): 241–266.

- Nyberg, D., C. Wright, and J. Kirk. 2018a. “Fracking the Future: The Temporal Portability of Frames in Political Contests.” Organization Studies 41 (2): 175–196. doi:10.1177/0170840618814568.

- Nyberg, D., C. Wright, and J. Kirk. 2018b. “Dash for Gas: Climate Change, Hegemony and the Scalar Politics of Fracking in the UK.” British Journal of Management 29: 235–251. doi:10.1111/1467-8551.12291.

- O’Hara, Sarah, Mathew Humphrey, Jessica Andersson-Hudson, and Wil Knight. 2016. Public Perception of Shale Gas Extraction in the UK: From Positive to Negative. Nottingham: University of Nottingham.

- Priestley, Sara. 2018. Shale Gas and Fracking. House of Commons Library. Briefing Paper Number CBP 6073, 8 October 2018.

- Pöyry. 2014. UK Shale Gas - Where Are We Now? Helsinki: Pöyry.

- Rice, J. L., B. J. Burke, and N. Heynen. 2015. “Knowing Climate Change, Embodying Climate Praxis: Experiential Knowledge in Southern Appalachia.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 105 (2): 253–262.

- Rolston, J. S. 2013a. “The Politics of Pits and the Materiality of Mine Labor: Making Natural Resources in the American West.” American Anthropologist 115 (4): 582–594.

- Rolston, J. S. 2013b. “Specters of Syndromes and the Everyday Lives of Wyoming Energy Workers.” In Cultures of Energy: Power, Practices, Technologies, edited by S. Strauss, S. Rupp, and T. Love, 582–594. San Francisco, CA: Left Coast Press.

- Scheer, D., W. Konrad, and S. Wassermann. 2017. “The Good, the Bad, and the Ambivalent: A Qualitative Study of Public Perceptions Towards Energy Technologies and Portfolios in Germany.” Energy Policy 100: 89–100.

- Sherren, K., J. R. Parkins, T. Owen, and M. Terashima. 2019. “Does Noticing Energy Infrastructure Influence Public Support for Energy Development? Evidence from a National Survey in Canada.” Energy Research & Social Science 51: 176–186.

- Short, Damien, and Anna Szolucha. 2019. “Fracking Lancashire: The Planning Process, Social Harm and Collective Trauma.” Geoforum 98: 264–276. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.03.001.

- Sovacool, B. K., J. Axsen, and S. Sorrell. November, 2018. “Promoting Novelty, Rigor, and Style in Energy Social Science: Towards Codes of Practice for Appropriate Methods and Research Design.” Energy Research & Social Science 45: 12–42.

- Sovacool, B. K. July, 2019. “The Precarious Political Economy of Cobalt: Balancing Prosperity, Poverty, and Brutality in Artisanal and Industrial Mining in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.” Extractive Industries & Society 6 (3): 915–939.

- Stirling, A. 2011. “Intolerance: Retain Healthy Scepticism.” Nature 471: 305. doi:10.1038/471305a.

- Szolucha, Anna. 2018a. “Anticipating Fracking: Shale Gas Developments and the Politics of Time in Lancashire, UK.” The Extractive Industries and Society 5: 348–355.

- Szolucha, A. 2018b. “Community Understanding of Risk from Fracking in the UK and Poland: How Democracy-Based and Justice-Based Concerns Amplify Risk Perceptions.” Chap. 16 in Governing Shale Gas: Development, Citizen Participation and Decision Making in the US, Canada, Australia and Europe, edited by J. Whitton, M. Cotton, I. Charnley-Parry, and K. Brasier. London: Routledge.

- Szolucha, Anna. 2019. “A Social Take on Unconventional Resources: Materiality, Alienation and the Making of Shale Gas in Poland and the United Kingdom.” Energy Research & Social Science 57: 2214–6296, 101254. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2019.101254.

- The Royal Society & Royal Academy of Engineering. 2012. Shale Gas Extraction in the UK: A Review of Hydraulic Fracturing. London: The Royal Society & Royal Academy of Engineering.

- Thomas, Merryn, Tristan Partridge, Barbara Herr Harthorn, and Nick Pidgeon. 2017. “Deliberating the Perceived Risks, Benefits, and Societal Implications of Shale Gas and Oil Extraction by Hydraulic Fracturing in the US and UK.” Nature Energy 2: 17054. doi:10.1038/nenergy.2017.54.

- UKOOG. 2013. Community Engagement Charter Oil and Gas from Unconventional Reservoirs. London: UKOOG. http://www.ukoog.org.uk/images/ukoog/pdfs/communityengagementcharterversion6.pdf.

- Watt, Nicholas. 2014. “Fracking in the UK: ‘We’re Going All out for Shale,’ Admits Cameron.” The Guardian, January 13, 2014. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2014/jan/13/shale-gas-fracking-cameron-all-out.

- Weick, K. E. 1995. Sensemaking in Organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Welsh, Ian, and Brian Wynne. 2013. “Science, Scientism and Imaginaries of Publics in the UK: Passive Objects, Incipient Threats.” Science as Culture 22 (4): 540–566. doi:10.1080/14636778.2013.764072.

- Whitton, John, Kathryn Brasier, Ioan Charnley-Parry, and Matthew Cotton. April 2017. “Shale Gas Governance in the United Kingdom and the United States: Opportunities for Public Participation and the Implications for Social Justice.” Energy Research & Social Science 26: 11–22.

- Williams, L., P. Macnaghten, R. Davies, and S. Curtis. 2017. “Framing ‘Fracking’: Exploring Public Perceptions of Hydraulic Fracturing in the United Kingdom.” Public Understanding of Science 26 (1): 89–104.

- Williams, L., and B. K. Sovacool. 2019. “The Discursive Politics of ‘Fracking’: Frames, Storylines, and the Anticipatory Contestation of Shale Gas Development in the United Kingdom.” Global Environmental Change 58: 101935. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2019.101935.

- Williams, L., and B. K. Sovacool. 2020. “Energy Democracy, Dissent and Discourse in the Party Politics of Shale Gas in the United Kingdom.” Environmental Politics 29 (7): 1239–1263 . doi:10.1080/09644016.2020.1740555.