ABSTRACT

Migration from the Global South to Global North is a major feature of contemporary population movements, and provides a lived experiment of the implications of moving from less resource-intensive modes of living towards more resource-intensive ones. Pre-migration practices come together in complex ways post-migration with established norms and infrastructures in destination countries. Here we examine the barriers to and enablers of sustainable practices, synthesising in-depth research from nine different studies in south-eastern Australia in relation to household water use, food growing and transport. The total sample includes 323 migrants from 33 countries. The main barriers include infrastructure and broader patterns of work and society. The main enablers are cultural norms of frugality and preferences for public transport. Barriers and enablers interact in diverse ways. We show that migrants are important contributors to inadvertent sustainabilities, but their contributions may be weakened by infrastructural, structural and cultural barriers. Addressing the diverse capacities of migrants would enhance system change for everyone.

Introduction

The cultural dimensions of sustainability issues and climate change responses are now well recognised (Adger et al. Citation2013; Crate Citation2011; Hackmann, Moser, and Clair Citation2014; Head et al. Citation2016). Migration has been an important dimension of cultural change throughout human history, as people discover and engage with new environments and find ways of living in them. An estimated 272 million people now live in a country other than their country of birth (McAuliffe and Khadria Citation2019). Half of all international migrants reside in ten high-income countries, many having moved from the Global South (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Citation2017, Citation2019). The influence of ethnicity and migration, particularly from Global South to Global North, is increasingly recognised as an important dimension of contemporary environmental cultures (Agyeman et al. Citation2016; Carter, Silva, and Guzmán Citation2013; de Guttry, Döring, and Ratter Citation2016; Head, Klocker, and Aguirre-Bielschowsky Citation2019a; Klocker and Head Citation2013). Effective environmental management in the Global North needs to take account of increasing ethnic diversity.

Research focused on the connections between migration and the environment has commonly focused on either environmental drivers of migration (Black et al. Citation2011; Hugo Citation1996; Kibreab Citation1997; McLeman Citation2014; Piguet, Kaenzig, and Guélat Citation2018) or, to a lesser extent, the negative impacts of migrants on the environment in their destinations (National Research Council Citation2005; Klocker and Head Citation2013; Oglethorpe et al. Citation2007). In this paper we examine the barriers to and enablers of (Adger et al. Citation2013; Hackmann, Moser, and Clair Citation2014) sustainability practices in the migration process, based on evidence from 323 migrants in south-eastern Australia from 33 different countries collected in nine separate sub-studies under the broader umbrella of the “Sustainability and climate change adaptation: unlocking the potential of ethnic diversity” project. By bringing together evidence from nine different sub-studies, which have been analysed separately, it is possible to identify common threads in the migration experience. This paper is not a secondary analysis of the primary data collected under each of the nine sub-studies. Instead, we bring the findings from the separate sub-studies together in conversation with each other. This approach benefits from the detailed insights of careful case study research and the rigour added by cumulative participant numbers.

Migration from the Global South to Global North provides a lived experiment of the implications of moving from less resource-intensive modes of living towards more resource-intensive ones. It throws particular light on processes of change and transition; how pre-migration practices come together, post-migration, with established norms and infrastructures in the migrant’s country of destination (Maller and Strengers Citation2013). Processes of acculturation have disruptive or solidifying potential for environmental knowledge and practices. Environmental practices are far more complex than simple questions of individual behaviour, but are bound up in the places, materials, meanings and infrastructures that comprise the routines of everyday life (Shove Citation2003). In this paper we examine practices around household water use, food growing and transport.

Australia is an exemplar place to explore this issue because of its high level of ethnic diversity. A varied Anglo-European majority exists alongside a diverse Indigenous population and significant numbers of migrants from countries in Asia, the Middle East and the Pacific. At the last Census 28% of Australia’s population was born overseas; and 49% of people were either born overseas themselves or had one or both parents born overseas (Australian Bureau of Statistics Citation2017). Sydney and Melbourne are two of the top five global cities in which international migrants make up at least one third of the total city population (International Organisation for Migration and Global Migration Data Analysis Centre Citation2017).

Ethnicity has been framed diversely in environmental studies of migration and in our own sub-studies. Here we use the term ethnicity to capture diverse aspects of identity: ancestry, heritage, nationality, culture and faith. Ethnicity and country of origin may (or may not) overlap, and so ethnicity can also be linked to experiences with particular modes of living, environments and infrastructures. We do not support interpretations of ethnicity as an innate or biological attribute that pre-disposes people to act or think in particular ways.

Existing research on acculturation and environmental knowledge and behaviour, in the international migration process (from Global South to Global North), shows mixed findings. Some researchers have concluded that ethnic background plays a more important role than acculturation, and thus that certain environmental norms are retained across migrant generations (Deng, Walker, and Swinnerton Citation2006; Lovelock et al. Citation2013). Others argue that migrants acculturate to resource-intensive norms post-migration to the Global North, in part because their socio-economic position improves (Adeola Citation2007; Hunter Citation2000; Macias Citation2016). Processes of behaviour change in the context of international migration can go in multiple directions, for better or worse with respect to sustainable practices.

There are two key methodological challenges in furthering these debates; scaling up the findings from qualitative research, and broadening the ways environment and sustainability are framed. Quantitative surveys, which can capture large numbers of research participants, tend to measure acculturation via time spent in the destination country (Johnson, Bowker, and Cordell Citation2004; Leung and Rice Citation2002). In-depth qualitative research, including ethnography and in-depth interviewing, that most effectively investigates environmental cultures, is necessarily conducted at small scales to provide rich, contextual understandings of everyday life. Qualitative research such as presented here can provide a more thorough understanding of the multiple influences on migrant acculturation, rather than solely length of time in the destination country. An ongoing issue is how to develop rigorous comparison of case study research without compromising the depth and detail which are its key strengths (Adger et al. Citation2013; Head et al. Citation2016; Liverman Citation2008). In this paper we seek to identify shared trends across a number of case studies of international migrants in Australia, all conducted by the authors. We do not attempt to do justice to the depth and nuance in each case.

As to the second challenge, it is important to recognise that commonly used indicators of environmental knowledge and behaviour are not universally applicable but specific to affluent western contexts and high levels of consumerism. Key examples include purchasing green electricity, green apparel products and energy-efficient cars (Head et al. Citation2018). Broadening our framing involves looking beyond intentional environmental behaviour to actual environmental outcomes that may occur for non-environmental reasons (e.g. cycling for health, installing insulation to save money on electricity bills, frugality because of poverty, catching the train due to a dislike of driving) (Gibson et al. Citation2013; Hitchings, Collins, and Day Citation2015; Krueger and Agyeman Citation2005).

Methods

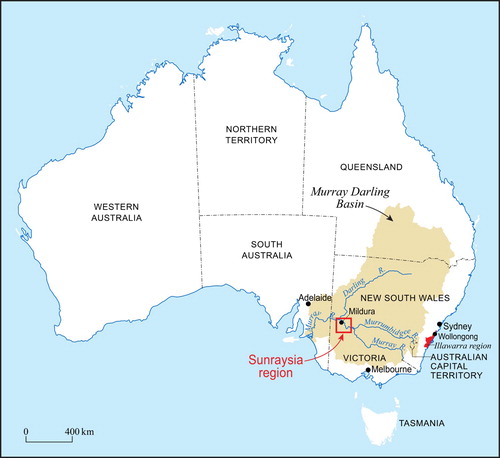

Our data come from in-depth research with international migrants in both urban and rural areas of south-eastern Australia (in the Sydney metropolitan region, Illawarra region and Sunraysia region; see ) collected as individual sub-studies as part of an overarching study about sustainability and climate change adaptation. Our primary aim was to conduct research with migrants in Australia, regardless of their socio-economic situation or class in their country of origin or Australia, to enable an openness to the diversity of ways in which migrants’ sustainability practices might emerge or be hindered. Our sub-studies focused on how migrants’ faith, cultural norms, embodied habits, preferences and values shape sustainability practices. This is not to argue that socio-economic status is irrelevant, but one of our sub-studies (Klocker et al. Citation2015) demonstrated statistically significant differences in practices between migrants and other groups, while controlling for demographic and income factors.

Eight of the sub-studies took an in-depth qualitative approach to exploring environmental topics by either choosing a specific location and investigating the topic across participants from multiple ethnic backgrounds or by choosing a particular ethnic group and exploring that topic with them (and in multiple locations if necessary). One sub-study was quantitative, using a survey instrument to gather insights on the transport behaviours of Sydney and Wollongong residents of diverse ethnic backgrounds. This fed into a subsequent in-depth qualitative study on the same topic. The total qualitative study sample relied on in this article comprises 231 participants from 33 different countries (including Australia). Of these, 205 participants (89%) were first generation migrants and 26 (11%) were second generation migrants. The quantitative sub-study incorporated 578 respondents, but only those of North East Asian ancestry (n = 92) were included here as they matched with one of the qualitative studies. Those of Anglo-Australian ancestry (n = 180) were included only for comparative purposes.

Household surveys, semi-structured interviews, focus group discussions, oral history, archival research, participant observation, and “go-alongs” (e.g. walking tours and home insights) (Carpiano Citation2009) were used variously in each sub-study to elicit research participants’ views on sustainability and climate change as well as to gain an understanding of their environmental and agricultural knowledges and practices. Questions included discussion of pre-migration knowledge and practices, the context of migration, and changes in knowledge and practices after settling in Australia.

Depending on the context and size of the sub-study, bilingual community co-researchers and cultural liaisons/research assistants were variously engaged for translating information given to participants as part of research ethics protocols, recruiting participants, interpreting during interviews, translating research transcripts and reflecting on/contextualising findings together with lead research investigators. Specific details about the year of data collection, number and ethnicity of research participants, and involvement of bilingual community researchers for each sub-study are summarised in according to the research topic investigated and study site region. Each of the qualitative sub-studies produced audio transcripts of interviews which were coded thematically, using a narrative analysis approach or analysed in discussion with bilingual community co-researchers. Logistic and ordinal regression were used on the quantitative survey dataset to assess the relationship between migrant status and transport behaviours.

Table 1. Summary details of sub-studies regarding ethnicity, migration and the environment.

Table 1. Continued

Table 1. Continued

The synthetic analysis involved coding of synthesised notes and outputs of individual sub-studies as opposed to coding anew the original transcripts produced by each sub-study. When coding, we identified which environmental practices the participants had brought with them; which of those practices they had retained; and the barriers and enablers as to why they had retained some practices but lost or adapted others (the complexity and richness of each in-depth analysis is included in other publications (Dun et al. Citation2018; Dun, Klocker, and Head Citation2018; Head et al. Citation2019; Head et al. Citation2018; Kerr, Klocker, and Waitt Citation2016; Kerr, Klocker, and Waitt Citation2018; Klocker et al. Citation2020; Klocker et al. Citation2018; Nowroozipour Citation2017; Spaven Citation2016; Waitt Citation2018; Waitt, Kerr, and Klocker Citation2016; Waitt and Nowroozipour Citation2018; Waitt and Welland Citation2019; Welland Citation2015)). We focus on the sustainability topics of household water use, food growing and transport in this paper because they allow us to scale up multiple sub-studies. Barriers and enablers for these three topics were compared across the final results of all sub-studies and grouped according to their socio-material configurations. Synthesising multiple qualitative analyses in this way allowed us to observe trends across many participants and diverse ethnic groups, while preserving the themes, interests and concerns that emerged from the participants themselves. Our analysis has parallels with meta-ethnography, in that that it “does not conceptually dismiss single case studies as locally bound”, but rather “compels us to acknowledge the importance of not only the uniqueness of individual cases, but also the uniqueness of collectives” (Doyle Citation2003, 340). We have not used a strict meta-ethnography method (Noblit and Hare Citation1988) as the original researchers were themselves involved in the synthesis and could comment on its resonance with their study.

Household water use

Household water use was explored through four separate sub-studies conducted in the Sydney metropolitan and Illawarra regions (). Two smaller studies focused on domestic water use and interactions with water among BurmeseFootnote1 and Iranian households. A larger study focused on water conservation, wastage and purity in domestic and recreational spaces among Sydney residents of Muslim faith from Jordan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan. A final sub-study focused on climate change adaptation in culturally diverse households and incorporated first-generation migrants from a diverse range of countries.

The sub-study about domestic water use among Burmese households (n = 16) in the Illawarra region gathered data in relation to participants’ pre-migration lives in Burma, participants’ migration history, and making a home in Australia. Information regarding household water practices linked to drinking water, washing up dishes, laundry use, showering/bathing, toilets and gardening was also collected.

The sub-study about domestic water use cultures of Iranian households (n = 15) in Sydney and the Illawarra region gathered information about participants’ migration history, family background and understanding of water from childhood to the present time. It also focused on household water practices linked to drinking water, washing up dishes, laundry use, showering/bathing and toilet use. Information about household room usage, layout and modifications in relation to water use considerations was also gathered.

The sub-study on relationships with urban water in domestic, recreational and religious spaces among Sydney residents of Muslim faith and Jordanian (n = 6), Bangladeshi (n = 10) or Hazara (n = 14) ethnicity took place in western and south western Sydney, areas of low to moderate income by Australian standards. It focused on understanding how participants’ environmental beliefs, knowledge and practices (particularly relating to water) in their country of origin were shaped by overarching Islamic principles and/or local custom. Information was also elicited about how participants’ experiences encountered during migration have affected these beliefs and practices, as well as how participants believed their environmental practices had changed since their initial arrival in Australia. Additionally, participants were asked to reflect on how their children’s water use practices might have been shaped by growing up in Australia as well as by their visits to their parents’ countries of origin.

The sub-study on climate change adaptation in first-generation migrant households incorporated 20 participants of 9 different ethnicities (). It gathered information on participants’ experiences of day-to-day weather and major weather events in Australia and overseas; their climate change attitudes and concerns; experiences of climate change discourse in Australia and overseas; and relationships (if any) between their ethnic backgrounds and climate change attitudes. Participants were asked to assess their own vulnerability to climate change and to evaluate this against the broader population. They were questioned about their understandings of climate change adaptation, and practices that they considered would be adaptive in relation to specific impacts predicted for south-eastern Australia. Experiences of and responses to water scarcity, and patterns of domestic water use, emerged as a key point of discussion in these interviews.

Food growing

Research about food growing, foraging and crop production took place in both the suburban Illawarra region and the rural Sunraysia region. In the Illawarra region, the focus was on food growing and foraging in suburban landscapes by migrants of KarenniFootnote2 (n = 21) and Portuguese (n = 15) ethnicity.Footnote3 This sub-study focussed on the small-scale farming and food foraging practices of each group; how their knowledge and practices adapted to local, social and environmental conditions; their engagements with local public spaces via food foraging; their experiences of low-chemical input farming via the integration of animals as soil fertility improvers; their reflections on agricultural practices brought from home countries and (where relevant) refugee camps; and opportunities for cross-cultural agricultural learning.

The Sunraysia region is a major horticultural production region of Australia straddling a section of the lower Murray River in south-western New South Wales and north-western Victoria. The fruit, vegetables and nuts grown in this region rely heavily on irrigation water supplied by the Murray River and on the labour of seasonal workers, many of whom are migrants of diverse ethnic origins. Research here focused on participants’ family migration stories and settlement experiences (n = 100, from 15 countries); experiences of agriculture and/or food growing in countries of origin and/or in the Sunraysia region; engagements with the local environment in the Sunraysia region and understandings of climate change and its implications; reflections on agricultural practices brought from countries of origin; and examples of cross-cultural agricultural learning, collaboration and/or conflict in the Sunraysia region.

Transport practices

The topic of transport was explored through a household sustainability questionnaire distributed to households in Sydney and Wollongong in 2012, and follow-up qualitative research conducted in 2014 in the Sydney Metropolitan Area with 14 first generation migrants from China and affiliated territories. The transport-related component of the questionnaire asked about respondents’ transport behaviours and values, including car ownership and use, mode/s of transport used for various everyday purposes (work, study, leisure, shopping), weekly petrol expenditure and frequency of/preference for public transport use. The methods used in the qualitative sub-study sought to gain insight into participants’ migration histories, transport choices and experiences for different travel purposes (i.e. work, shopping, social), ideas and experiences associated with certain modes of transport (i.e. car, bus, train), and links between participants’ multiple identities, cultural background/pre-migration life histories and their subsequent mobility choices. Travel diaries provided insights into participants’ weekly travel patterns, rhythms, routes and interruptions.

Results and discussion

The socio-material configurations we identify as constituting barriers to and enablers of sustainable practices comprise different combinations of the following: Australian weather conditions and environments, cultural expectations or preferences (at the broader societal level and individual/household level), faith, infrastructure (within and beyond the household), social structures of work, economic constraints and well-being motivations. To demonstrate how diverse environmental outcomes arise through these different socio-material configurations, we trace the three common sustainability themes discussed above: household water use, food growing and transport practices. We highlight the most influential barriers and enablers in each situation.

Household water use

Key enablers of migrants’ judicious domestic water use were experiences with water scarcity, diverse weather patterns and irregular supply in countries of origin (). Many participants in these four sub-studies had come from a situation of irregular domestic water supply and accessibility in their countries of origin. In different contexts this was due to the need for manual collection from wells or streams, unreliable (poorly or partly built, or not well maintained) mains infrastructure, government rationing, a dry climate and war. Irregularity of water supply instilled water saving behaviours pre-migration e.g. constant attentiveness to the sacredness and preciousness of water, capturing water used to wash food for subsequent use in gardens, and foregoing clothes washing to preserve scarce water during summer.

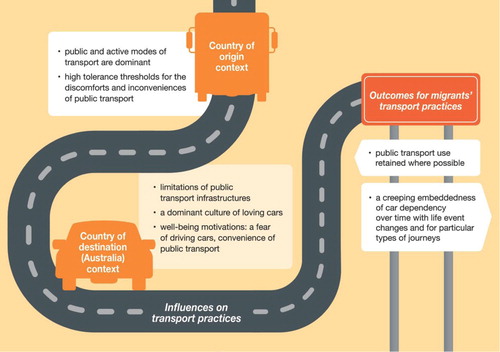

Figure 2. Country of origin context, country of destination context, and outcomes for migrants’ water use practices. White arrows show drivers to increased (top) and reduced (lower) water consumption.

Additional enablers of migrants’ frugal water use were religious faith and cultural norms from home countries. In regard to the former, faith had an important influence on water perception and usage for both Muslim and Buddhist participants that extended into their post-migration lives. Muslims of diverse backgrounds referred to two key teachings about water; first a prohibition on wastage, and second a need to conserve water because of responsibility to other people in the community. Participants of both faiths referred to the cleansing of the inner person and use of water in different everyday rituals. Turning to the latter, Burmese participants described in detail the practice of bathing with a scoop and bucket of water as not only cleansing, but as refreshing and meditative. Water was understood as a resource to be conserved. However, some Burmese participants came to shower on a daily basis in Australia. They attributed this to changed ideas about the practice of washing bodies, based on the ability to shower not only as a means to relax but as a transitioning tool between wakefulness and sleep or work and leisure activities. Conforming to the Australian norm of daily showering is underpinned by values of cleanliness. These shifts parallel increased showering in other migrant groups influenced by “Australian” cultures of showering, including a warm shower as relaxing after work, and dealing with more humid conditions than people were used to (e.g. Sydney vs Jordan).

In addition to the gradual adoption of Australian cultural norms, the key barrier to continuing frugal water use patterns post-migration is that the infrastructure providing reliable high-quality mains-supplied water in Australia creates an illusion of endless supply (Sofoulis Citation2005) and more readily and easily enables water consumption increase. (We say illusion because south-eastern Australia is regularly beset by severe drought.) Many migrants recounted the relaxation of their more frugal (pre-migration) water use habits as this seemingly abundant supply interacted with the demands of changed everyday lives. One particular theme related to teenagers, with a number of migrant parents expressing alarm that their children had adopted a profligate attitude to water usage due to the ready availability of tap water in Australia. This raised particular concerns for Jordanians and other Muslim parents in all migrant groups, including on visits to home countries where such habits were noted. Some referred to internet interactions with friends and relatives at “home”, particularly those experiencing water scarcity, as being important in maintaining their faith-based approach to moderation and social responsibility in water use. However, these same Jordanian parents and most young adult interviewees from all three Sydney Muslim participant groups gave accounts of re-establishing more frugal water use habits as they grew older. Parents put this down to their children maturing in their religious faith. The younger interviewees may have agreed, but pointed out as well that they were now paying their own household water bills.

The religious connotation of water overlapped with a strong preference common among Muslims, Hindus and others across the Middle East, South Asia and possibly South East Asia to use water for anal cleansing after defaecation. While this may use additional water, it avoided the recent (apparently rising) use of non-biodegradable moist toilet wipes among the wider population. The barrier to this practice in Australia was the low income of most recent immigrants, necessitating rented accommodation, where fixed bathroom technologies did not allow accessible water. Our interviewees had frequently reverted to traditional technologies (e.g. a spouted pot [lota or bodna] placed with a jug of water and dipper beside the flush toilet). The enabler for restoration of wider use of water for anal cleansing was rising income, allowing interviewees to purchase their own home and install preferred technologies which allowed water accessible to the toilet.

These diverse responses raise questions about whether “acculturation” is inevitably in one direction (towards more or less sustainable practices), or is instead moderated over time by factors like economic considerations or cultural expectations and community cohesion, making it multidimensional and variable in direction (Erten, van den Berg, and Weissing Citation2018; Schwartz et al. Citation2010). This variability also emerged in the sub-study on household climate change adaptation. Some first-generation migrants reported that their careful pre-migration domestic water use practices (developed for reasons already outlined: cultural norms, scarcity and/or inaccessibility) resurfaced in their Australian lives when needed, such as during periods of drought-induced domestic water use restrictions. Their water saving skills were not always in use in their Australian lives, because they were deemed unnecessary, but these migrants felt reassured that they were well-equipped to cope with future periods of water shortage.

In summary, there are diverse environmental outcomes for migrants’ practices regarding water use once in Australia, influenced by both their country of origin and destination context and experiences (). While enablers to the continuation of sustainable domestic water practices post-migration exist, they appear to weaken over time. Trends in the other direction include the generational shift in frugal practices discussed above and migrants’ capacity to fall back on pre-migration practices when confronted by water scarcity in their new home country.

Food growing

Most of these participants had in common that, at the point they arrived in Australia, they had come from countries or contexts where growing one’s own food for subsistence or small-scale commercial ventures, typically organically, was a cultural norm. They had a deep desire to continue to grow food in Australia, for four main reasons: saving money, taste, cultural identity and preference for not using artificial chemicals.

A key barrier for migrants to continue their preferred practice of growing food for their own consumption without the use of artificial chemicals is a lack of access to the fundamental infrastructure of land in Australia (). Infrastructure here is understood as both the actual presence of land (e.g. in a domestic or community garden or farm), and the tenure arrangements that constrain activities (e.g. legal requirements for insurance or stable water supply). Those interested in farming at a larger-scale were unable to afford to purchase or rent land. Where possible, interviewees attempted to grow food in every available space around their homes, at times replacing pre-existing ornamental plants and trees that did not produce edible fruit with those that did, or creating shallow ponds to grow herbs. Driven by the preference to grow food organically, participants integrated chickens into their garden growing practices or distributed scraps in such a way to attract wild birds to come and fertilize their gardens. However, for those who rented houses with garden spaces, rental regulations often prevented them from changing the pre-existing vegetation in the garden space and instead food was grown in pots and containers.

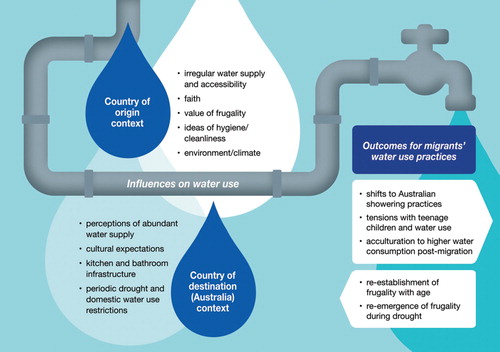

Figure 3. Country of origin context, country of destination context, and outcomes for migrants’ food growing practices. White arrows show drivers to less (top) and more (lower) sustainable practices.

Two further barriers to the maintenance of sustainable food growing practices were cultural expectations and social structures of work, linked to an economic and societal structure that dictates how food is grown and supplied in Australia and the safety standards and level of formalised skills expected alongside that. Growing most of one’s own food for consumption is not a cultural norm in Australia. Rather, the majority of food is supplied to customers via supermarkets. As an industrialised country, service and industry sector occupations prevail as the dominant sectors in which people work, leaving limited time for growing one’s own food.

The barriers mentioned above mean that migrants’ food growing capacities, skill and knowledge remain largely hidden (as does their important potential contribution to addressing sustainability, crop diversity and climate change adaptation challenges confronting Australian horticulture) until they have been able to find a way to grow food on larger plots of land that are visible to others (Klocker et al. Citation2018). Aside from the long term efforts of migrants’ own hard work to build themselves to a stage where they can afford to purchase and farm their own land in Australia (as has been the case for Italian migrants we interviewed), or the generosity of another farmer willing to share some of their land, a core enabler for more quickly supporting the continuation of migrants’ food growing practices is facilitation of access to land infrastructure by community-based organisations, local institutions and governments willing to support the well-being motivations of migrants. In our research, community gardens or farms became important sites for migrants to continue some of their sustainable food growing practices on small garden beds. In the Sunraysia region, a newly established initiative (Food Next Door Co-operative) involving a network of locally-based volunteers that matches newly arrived landless migrant farmers with donated underutilised farmland, proved to be a crucial mechanism for allowing Burundian refugees’ organic food growing practices to continue in Australia (Dun et al. Citation2018). In the Illawarra, community-based organisations (Green Connect, SCARF) have supported Karenni migrants to grow food in communal gardens or farms providing access to land infrastructure, tools, resources and public liability insurance (Murphy Citation2017; Sinclair Citation2017). Karenni farmers reported that farming collectively – rather than individually in backyards – was a more culturally appropriate way of farming.

In both of the sub-studies focused on migrants’ food growing practices, pre-migration farming techniques that do not rely on artificial chemicals were continued on available land. These migrants did not acculturate to the chemical intensive farming methods that are more common in Australia. Outcomes were diverse, though, with regard to their capacity to continue growing food at all, and the scale at which they were able to do so. Many, then, were forced to buy (rather than grow) a significant proportion of their households’ food supplies (a negative outcome for sustainability implications given Australia’s industrial farming norms and associated food miles) ().

Transport practices

Research in Sydney demonstrated that Chinese migrants’ transport patterns in Australia were shaped by transport norms and infrastructures in their countries of origin. Migrants from China and affiliated territories (Taiwan and Hong Kong) came from contexts where public and active modes of transport remain dominant (He et al. Citation2005). Past experiences and transport practices in participants’ countries of origin appeared to foster different expectations of mobility and higher tolerance thresholds for the discomforts and inconveniences of public transport that continued post-migration.

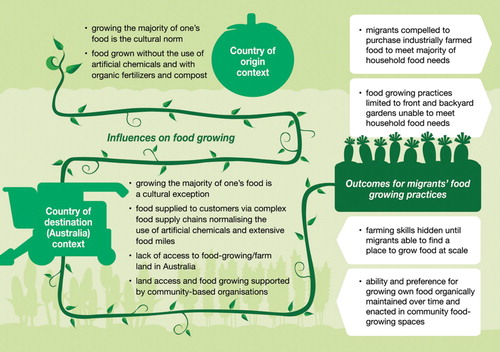

In contrast to the “love affair” many Anglo-European Australians have with their cars (Waitt and Harada Citation2012), the Chinese migrants’ emotional responses towards cars and driving ranged from pragmatism and ambivalence to fear and hostility. While most of the participants owned and used cars in Australia, they did not see them as essential for all trips and voiced a preference for using public transport whenever possible. Notably, the findings of this qualitative sub-study help to explain the results of an earlier quantitative sub-study that found evidence of significantly lower rates of car ownership and use amongst North-East Asian Australians (n = 92) vis-à-vis Anglo-Australians (n = 180) (Klocker et al. Citation2015). This cultural preference for public transport is an enabler that led participants in the qualitative sub-study to orient their lives around places that facilitate its use, i.e. they chose to live in close proximity to railway lines or bus routes primarily because they feared car driving and/or felt public transport was more convenient (in terms of not having to constantly worry about crashing or where one is going) (). Despite a preference to continue these transport behaviours post-migration, participants felt that it was difficult to rely solely on public transport in Sydney, especially for grocery shopping or after major life changes such as having a child. Car use was also perceived as desirable for social and recreational trips. Thus, even the most committed public transport users (and fearful drivers) felt compelled to purchase and drive cars for some trips. The barriers to maintaining sustainable transport practices post-migration were twofold. First, Sydney’s poor public transport infrastructures embed car dependency, even among those with a preference not to drive. Second, the interactions between public transport infrastructure and the social structures of work and society make it extremely difficult to perform journeys with multiple tasks on public transport. The barriers presented by post-migration transport infrastructures and transport cultures both, then, prompt a degree of acculturation by working against the maintenance of migrants’ lower-carbon mobilities over the longer-term. There are diverse environmental outcomes for migrants’ practices regarding transport practices once in Australia, influenced by both their country of origin and destination contexts and experiences ().

Conclusions

In this paper we have synthesised common themes from a number of detailed sub-studies, strengthening the contribution of the individual studies by identifying shared barriers and enablers. The main barriers include infrastructure, including of water supply and transport, and broader patterns of work and society. The main enablers are cultural norms of frugality and preferences for public transport. Migrants are not a blank slate; they bring pre-migration experiences influenced by a combination of faith, cultural norms, embodied habits, preferences and values. We have shown that, far from being environmentally problematic, migrants from the Global South are potentially important contributors to inadvertent sustainabilities. However, their contributions are weakened by the presence of infrastructural, structural and cultural barriers in their post-migration contexts.

In most of our sub-studies, barriers seem to be over-powering culturally-informed enablers. Current sustainability policy rarely takes this cultural complexity and diversity into account, but it needs to in order to support enablers that facilitate the continuation of environmentally-beneficial practices and address the barriers that ultimately push many migrants to acculturate to less sustainable norms. Support for migrants to continue their prior practices in a new setting would also address newcomers’ desire to socialise, belong and create a sense of “home” in their new countries. The barriers for migrants’ environmental practices are also barriers for the broader population, and the resource of diverse ideas contributed by migrants can engender much-needed systemic change. Detailed, qualitative case studies shed light on opportunities for newcomers to act as circuit-breakers for established practices and logics that are unsustainable. For this to occur, there needs to be an openness to acculturation in the other direction, that is, for culturally dominant populations in the Global North to learn from their newer members.

Acknowledgements

The study was funded by the Australian Research Council (DP 140101165). This type of research would not be possible without the skills and effort of multiple community-based bilingual co-researchers and the support of institutions and community organisations that provide diverse support to migrants and refugees. We gratefully acknowledge the support provided by Louisa Welland, Min Si Thu Khin (Burmese co-researcher), Kais Al Momani (PhD, Arabic-speaking community researcher), Wafa Zaim (Arabic-speaking community researcher), Sumaya Afrin Eku (Bengali-speaking community researcher), Latifa Hekmat (Hazaragi-speaking community researcher), Eh Moo (Karenni co-researcher), Patricia Laranjeira (Portuguese interpreter), Trang Le (Vietnamese-speaking co-researcher), Kato Holani (Tongan-speaking co-researcher), Joel Sindayigaya (Swahili/Kirundi-speaking co-researcher), Zia Ibrahimi (Hazaragi-speaking co-researcher) and Paul Mbenna (Swahili speaking research assistant).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In 1989, the military government of the Union of Burma changed the official name to the Union of Myanmar to better reflect the country’s ethnic diversity and sever from the British colonial past. The United Nations accepted the name change, although those opposed to the military government questioned the imposed changes. Mindful that the act of naming is always political, this paper reflects the participants’ use of the terms “Burmese” and “Burma”.

2 Karenni people are ethnically and linguistically closely related to Karen people and are also known as Kayah, Kayin, Kayinni or Karenni which means “red Karen” and refers to traditional clothing. Most participants speak a variant of Karenni (Eastern and Western) and identify as Karenni though their ancestry is mixed with those who identify as Karen. Karenni and Karen people are often classified as “Burmese” in the Australian census, but this is likely an oversight. Participants referred to ethnic Bamar people, who are the ethno-linguistic majority in Burma/Myanmar, as Burmese. Due to ongoing historical conflict and persecution, using the term “Burmese” to refer to Karenni people is problematic.

3 At the time of migration, in the 1970s, Portugal was considered part of the Global South.

References

- ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics). 2017. “Cultural Diversity in Australia, 2016: 2016 Census Article. 2071. 0 Census of Population and Housing: Reflecting Australia – Stories from the Census, 2016.” https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/Lookup/by%20Subject/2071.0~2016~Main%20Features~Cultural%20Diversity%20Article~60.

- Adeola, F. O. 2007. “Nativity and Environmental Risk Perception: An Empirical Study of Native-Born and Foreign-Born Residents of the USA.” Human Ecology Review 14 (1): 13–25.

- Adger, W. N., J. Barnett, K. Brown, N. Marshall, and K. O’brien. 2013. “Cultural Dimensions of Climate Change Impacts and Adaptation.” Nature Climate Change 3 (2): 112–117.

- Agyeman, J., D. Schlosberg, L. Craven, and C. Matthews. 2016. “Trends and Directions in Environmental Justice: From Inequity to Everyday Life, Community, and Just Sustainabilities.” Annual Review of Environment and Resources 41: 321–340.

- Black, R., W. N. Adger, N. W. Arnell, S. Dercon, A. Geddes, and D. Thomas. 2011. “The Effect of Environmental Change on Human Migration.” Global Environmental Change 21: S3–S11.

- Carpiano, R. M. 2009. “Come Take a Walk with me: the “Go-Along” Interview as a Novel Method for Studying the Implications of Place for Health and Well-Being.” Health & Place 15 (1): 263–272.

- Carter, E. D., B. Silva, and G. Guzmán. 2013. “Migration, Mcculturation, and Environmental Values: The Case of Mexican Immigrants in Central Iowa.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 103 (1): 129–147.

- Crate, S. A. 2011. “Climate and Culture: Anthropology in the Era of Contemporary Climate Change.” Annual Review of Anthropology 40: 175–194.

- de Guttry, C., M. Döring, and B. Ratter. 2016. “Challenging the Current ClimateCchange–Migration Nexus: Exploring Migrants’ Perceptions of Climate Change in the Hosting Country.” DIE ERDE–Journal of the Geographical Society of Berlin 147 (2): 109–118.

- Deng, J., G. J. Walker, and G. Swinnerton. 2006. “A Comparison of Environmental Values and Attitudes between Chinese in Canada and Anglo-Canadians.” Environment and Behavior 38 (1): 22–47.

- Doyle, L. H. 2003. “Synthesis through Meta-Ethnography: Paradoxes, Enhancements, and Possibilities.” Qualitative Research 3: 321–344.

- Dun, O., D. Bogenhuber, L. Head, J. Kadahari, N. Klocker, J. Niyera, and J. Sindayigaya. 2018. “Bringing Together Landless Farmers and Unused Farmland: The Sunraysia Burundian Garden and Food Next Door Initiative.” In Reclaiming the Urban Commons: The Past, Present and Future of Food Growing in Australian Towns and Cities, edited by N. Rose, and A. Gaynor, 39–52. Crawley: University of Western Australia.

- Dun, O., N. Klocker, and L. Head. 2018. “Recognising Knowledge Transfers in ‘Unskilled’ and ‘Low-Skilled’ International Migration: Insights from Pacific Island Seasonal Workers in Rural Australia.” Asia Pacific Viewpoint 59 (3): 276–292.

- Erten, E. Y., P. van den Berg, and F. J. Weissing. 2018. “Acculturation Orientations Affect the Evolution of a Multicultural Society.” Nature Communications 9 (1): 1–8.

- Gibson, C., C. Farbotko, N. Gill, L. Head, and G. Waitt. 2013. Household Sustainability: Challenges and Dilemmas in Everyday Life. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Hackmann, H., S. C. Moser, and A. L. S. Clair. 2014. “The Social Heart of Global Environmental Change.” Nature Climate Change 4 (8): 653–655.

- He, K., H. Huo, Q. Zhang, D. He, F. An, M. Wang, and M. P. Walsh. 2005. “Oil Consumption and CO2 Emissions in China's Road Transport: Current Status, Future Trends, and Policy Implications.” Energy Policy 33 (12): 1499–1507.

- Head, L., C. Gibson, N. Gill, C. Carr, and G. Waitt. 2016. “A Meta-Ethnography to Synthesise Household Cultural Research for Climate Change Response.” Local Environment 21 (12): 1467–1481.

- Head, L., N. Klocker, and I. Aguirre-Bielschowsky. 2019. “Environmental Values, Knowledge and Behaviour: Contributions of an Emergent Literature on the Role of Ethnicity and Migration.” Progress in Human Geography 43 (3): 397–415.

- Head, L., N. Klocker, O. Dun, and I. Aguirre-Bielschowsky. 2019. “Cultivating Engagements: Ethnic Minority Migrants, Agriculture, and Environment in the Murray-Darling Basin, Australia.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 109 (6): 1903–1921.

- Head, L., N. Klocker, O. Dun, and T. Spaven. 2018. “Irrigator Relations with Water in the Sunraysia Region, Northwestern Victoria.” Geographical Research 56 (1): 92–106.

- Hitchings, R., R. Collins, and R. Day. 2015. “Inadvertent Environmentalism and the Action–Value Opportunity: Reflections from Studies at Both Ends of the Generational Spectrum.” Local Environment 20 (3): 369–385.

- Hugo, G. 1996. “Environmental Concerns and International Migration.” International Migration Review 30 (1): 105–131.

- Hunter, L. M. 2000. “A Comparison of the Environmental Attitudes, Concern, and Behaviors of Native-Born and Foreign-Born U.S. Residents.” Population and Environment 21 (6): 565–580.

- International Organisation for Migration and Global Migration Data Analysis Centre (IOM and GMDAC). 2017. Global Migration Trends Factsheet. Berlin: IOM GMDAC.

- Johnson, C. Y., J. M. Bowker, and H. K. Cordell. 2004. “Ethnic Variation in Environmental Belief and Behavior: An Examination of the New Ecological Paradigm in a Social Psychological Context.” Environment and Behavior 36 (2): 157–186.

- Kerr, S., N. Klocker, and G. Waitt. 2016. “Low-Carbon Transport Communities, In a Car Dependent Nation.” In Low Carbon Mobility Transitions, edited by D. Hopkins, and J. Higham, 77–82. Oxford: Goodfellow.

- Kerr, S., N. Klocker, and G. Waitt. 2018. “Diverse Driving Emotions: Exploring Chinese Migrants’ Mobilities in a Cardependent City.” Transfers 8 (2): 23–43.

- Kibreab, G. 1997. “Environmental Causes and Impact of Refugee Movements: A Critique of the Current Debate.” Disasters 21 (1): 20–38.

- Klocker, N., O. Dun, L. Head, and A. Gopal. 2020. “Exploring Migrants’ Knowledge and Skill in Seasonal Farm Work: More Than Labouring Bodies.” Agriculture and Human Values, 37:463–478.

- Klocker, N., and L. Head. 2013. “Diversifying Ethnicity in Australia's Population and Environment Debates.” Australian Geographer 44 (1): 41–62.

- Klocker, N., L. Head, O. Dun, and T. Spaven. 2018. “Experimenting with Agricultural Diversity: Migrant Knowledge as a Resource for Climate Change Adaptation.” Journal of Rural Studies 57: 13–24.

- Klocker, N., S. Toole, A. Tindale, and S. M. Kerr. 2015. “Ethnically Diverse Transport Behaviours: An Australian Perspective.” Geographical Research 53 (4): 393–405.

- Krueger, R., and J. Agyeman. 2005. “Sustainability Schizophrenia or ‘Actually Existing Sustainabilities?’ Toward a Broader Understanding of the Politics and Promise of Local Sustainability in the US.” Geoforum 36 (4): 410–417.

- Leung, C., and J. Rice. 2002. “Comparison of Chinese-Australian and Anglo-Australian Environmental Attitudes and Behavior.” Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal 30 (3): 251–262.

- Liverman, D. 2008. “Assessing Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability: Reflections on the Working Group II Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.” Global Environmental Change 18 (1): 4–7.

- Lovelock, B., C. Jellum, A. Thompson, and K. Lovelock. 2013. “Could Immigrants Care Less About the Environment? A Comparison of the Environmental Values of Immigrant and Native-Born New Zealanders.” Society & Natural Resources 26 (4): 402–419.

- Macias, T. 2016. “Ecological Assimilation: Race, Ethnicity, and the Inverted Gap of Environmental Concern.” Society & Natural Resources 29 (1): 3–19.

- Maller, C., and Y. Strengers. 2013. “The Global Migration of Everyday Life: Investigating the Practice Memories of Australian Migrants.” Geoforum 44: 243–252.

- McAuliffe, M., and B. Khadria, eds. 2019. World Migration Report 2020. Geneva: International Organization for Migration, United Nations.

- McLeman, R. A. 2014. Climate and Human Migration: Past Experiences, Future Challenges. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Murphy, S. 2017. “Australia’s Karenni Refugees Cultivate Community through Wollongong Farming Initiative.” Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) News. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-08-26/karenni-refugees-cultivate-a-community-in-wollongong/8839216.

- National Research Council. 2005. Population, Land Use, and Environment: Research Directions. Washington: The National Academies.

- Noblit, G. W., and R. D. Hare. 1988. Meta-Ethnography: Synthesizing Qualitative Studies. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Qualitative Research Methods.

- Nowroozipour, F. 2017. “Domestic Water Cultures of Iranian Migrant Households Living in the Sydney Metropolitan Region.” Master diss. University of Wollongong.

- Oglethorpe, J., J. Ericson, R. E. Bilsborrow, and J. Edmond. 2007. “People on the Move: Reducing the Impacts of Human Migration on Biodiversity.” World Wildlife Fund and Conservation International Foundation. https://www.worldwildlife.org/publications/people-on-the-move-reducing-the-impacts-of-human-migration-on-biodiversity.

- Piguet, E., R. Kaenzig, and J. Guélat. 2018. “The Uneven Geography of Research on ‘Environmental Migration’.” Population and Environment 39 (4): 357–383.

- Schwartz, S. J., J. B. Unger, B. L. Zamboanga, and J. Szapocznik. 2010. “Rethinking the Concept of Acculturation: Implications for Theory and Research.” American Psychologist 65 (4): 237–251.

- Shove, E. 2003. Comfort, Cleanliness and Convenience: The Social Organization of Normality. London: Berg.

- Sinclair, H. 2017. “The Burmese Refugees Putting Down Roots in Wollongong.” Special Broadcasting Service (SBS) News. https://www.sbs.com.au/news/the-burmese-refugees-putting-down-roots-in-wollongong.

- Sofoulis, Z. 2005. “Big Water, Everyday Water: A Sociotechnical Perspective.” Continuum 19 (4): 445–463.

- Spaven, T. 2016. “Exploring Migrants’ Contributions to Agriculture: The Story of Italians in the Sunraysia Region” Honours diss., University of Wollongong.

- UNDESA (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs). 2017. International Migration Report 2017: Highlights (ST/ESA/SER.A/404). New York: UNDESA Population Division.

- UNDESA (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs). 2019. International Migrant Stock 2019: Graphs - Twenty Countries or Areas Hosting the Largest Numbers of International Migrants (Millions). New York: UNDESA Population Division.

- Waitt, G. 2018. “Ethnic Diversity, Scarcity and Drinking Water: A Provocation to Rethink Provisioning Metropolitan Mains Water.” Australian Geographer 49 (2): 273–290.

- Waitt, G., and T. Harada. 2012. “Driving, Cities and Changing Climates.” Urban Studies 49 (15): 3307–3325.

- Waitt, G., S. Kerr, and N. Klocker. 2016. “Gender, Ethnicity and Sustainable Mobility: A Governmentality Analysis of Migrant Chinese Women’s Daily Trips in Sydney.” Applied Mobilities 1 (1): 68–84.

- Waitt, G., and F. Nowroozipour. 2018. “Embodied Geographies of Domesticated Water: Transcorporeality, Translocality and Moral Terrains.” Social & Cultural Geography, 1–19. doi:10.1080/14649365.2018.1550582.

- Waitt, G., and L. Welland. 2019. “Water, Skin and Touch: Migrant Bathing Assemblages.” Social & Cultural Geography 20 (1): 24–42.

- Welland, L. 2015. “Cultures of Water: Exploring the Role of Water as a Home-Making Practice of Burmese Migrant Households in Metropolitan NSW.” Honours diss., University of Wollongong.