ABSTRACT

Extinction Rebellion (XR) has rapidly risen to prominence in the last two years, but in part because of the group’s meteoric rise, there are relatively few academic analyses of it. This paper draws on collective-action framing theory to examine the engagement of one XR group – XR Norwich – with notions of climate justice. Drawing on ten in-depth interviews conducted in mid-2019, it argues that despite general concern for the global South, XR Norwich members mostly framed climate change in terms more reminiscent of mainstream environmental policy makers, rather than the radical climate justice movement. This raises questions about the extent to which XR Norwich engages their members on climate justice concerns, whether XR Norwich is more concerned with generating appeal instead of offering radical solutions, and whether such a strategy might lead to factionalism within the broader XR movement.

Introduction

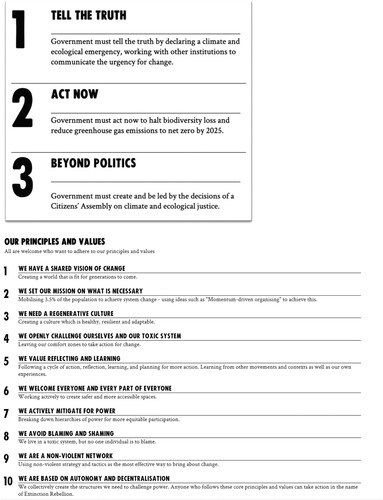

Extinction Rebellion (XR) may be one of the most important environmental protest movements to emerge in the UK in the last few decades, alongside international groups such as Fridays for the Future and the Sunrise Movement (Martiskainen et al. Citation2020; Fisher Citation2019). Formed in October 2018, the group staged three major protests in London during 2019, with its first International Rebellion in April 2019, so called due to the involvement of XR groups established in approximately 30 countries, dramatically increasing its public profile (Edie Citation2019) and leading the UK government to declare a “climate emergency” (BBC News Citation2019b). XR was founded in the context of what co-founder Roger Hallam described as the “climate inaction” of the UK Government (Zand Citation2019, 1). It was designed as a civil disobedience movement which uses nonviolent direct-action tactics, most notably arrestable disruption (XR Citation2020d). The group is organised as a holacracy, wherein any actor can self-organise around XR’s three demands and ten principles () to form a local XR group or participate in actions under the banner of XR (XR Citation2019c).

Figure 1. XR’s Demands and Principles. Reproduced from XR (Citation2020d).

XR has attracted criticism from across the political spectrum. The right-leaning broadsheet The Telegraph branded XR as radical environmentalists (see Welsh Citation2019), while the more centrist online newspaper The Independent criticised XR for not acknowledging the work of climate justice (CJ) activists (especially people of colour and indigenous groups) and for its advocacy of arrestable disruption as this ignores the history of police aggression against marginalised people (Josette Citation2019; see also Cowan Citation2019; Gayle Citation2019; Shand-Baptiste Citation2019). CJ activist groups have also criticised XR, the most prominent being the grassroots collective Wretched of the Earth, which admonished XR for being silent on the particular impacts of climate change on disadvantaged groups in the global North and South and the “root causes of climate change – capitalism, extractivism, racism, sexism, classism, ableism and other systems of oppression” (Wretched of the Earth Citation2019, 3).

Given that its engagement with CJ (or lack thereof) has been a key criticism of XR, and that its holocratic structure means it is inherently difficult to draw generalisations across constituent groups, this paper focusses on just one XR group – XR Norwich – adopting a social movement framing perspective to examine how it frames its demands, focussing particularly on its engagement with CJ. One of hundreds of sub-groups established since XR’s founding (XR Norwich Citation2020), studying XR Norwich is productive both because, as Snow (Citation2004) argues, the views of “rank-and-file” members within a movement can reflect and/or shape those movements, and because XR Norwich has gained a profile within XR, achieving coverage in both the national and local media (see BBC News Citation2019a; Johnson Citation2019; Hannant Citation2019). Our findings suggest that despite the efforts of some individual members, XR Norwich does not consistently mobilise CJ frames in its framing processes, focussing on apoliticism and individual responsibility instead. We call for further research in this area, arguing that this opens up several critical inferences about XR useful to future studies and the group(s) themselves.

The paper starts by explaining social movement framing theory and applying it to explore the emergence of two main social movement frames within the climate movement: a mainstream climate action frame and a more radical climate justice frame. The paper then turns its attention to the collective framing processes of XR Norwich. Examining the diagnostic, prognostic and motivational frames deployed by the group, it argues that they correspond more closely with the mainstream “climate action” frame than the CJ frame, though there are some synergies with CJ and some individual activists align themselves with this frame. This analysis contributes both to developing frame theory – since only a few contributors have attempted bottom-up approaches to frame analysis (Ketelaars, Walgrave, and Wouters Citation2017) – and to a better understanding of XR’s framing processes and their implications for climate justice.

Framing, collective action, climate justice and XR

Understanding framing and collective action

The prevailing consensus among social movement scholars is that three factors shape the mobilisation potential of social movements: political opportunity, mobilising structures and framing processes (McAdam Citation2017). Snow and Benford (Citation1992, 137) define frames as “schemata of interpretation” used by individuals to simplify and give meaning to “the world out there”. Cognitive science and behavioural studies have demonstrated that frames are ubiquitous in human decision-making and understanding of the world, particularly in how we understand the environment (Lakoff Citation2010). For example, Lockwood (Citation2011) discovered support for the expansion of renewable energy increased significantly amongst his study participants when it was framed as increasing energy independence rather than as a method of climate change adaptation. Thus, an understanding of the content of frames and what they leave out or supress is vital to analyse social behaviour (Futrell Citation2003).

Framing theory assumes that socio-political actors use frames to assume control of and assert the legitimacy of issues on behalf of certain interests and groups (della Porta and Diani Citation2009). Frames often emerge in the context of cycles in public attention on an issue (Giugni and Grasso Citation2015). For example, initial interest in climate change was sparked by a change of framing by the then-declining environmental movements of the 1970s and 1980s (Jamison Citation2010). Framing, therefore, is an active and dynamic process of the production and maintenance of meaning (Snow, Tan, and Owens Citation2013). It has both individual and collective aspects, such that collective action frames are always dependent on the framing processes of individual supporters (Snow Citation2004). Scholars posit that the most powerful mobilising frames connect individual and collective identities to an issue, such as in the American civil rights movement (McAdam Citation2017).

In their seminal 1988 paper, Snow and Benford (Citation1988) argue that social movements consciously engage in “collective action framing” to mobilise supporters and demoralise their opponents. This is done in three ways: (1) focusing attention; (2) combining events, situations and social facts to convey an intended meaning; and (3) transforming how an object of attention is seen or understood as relating to another object or actor (Lindekilde Citation2014). Given its deliberative nature and the importance of framing in shaping opinion, the use of frames by social movements can be regarded by as a central dynamic in understanding their character and course (Benford and Snow Citation2000). Benford and Snow (Citation2000) therefore proposed collective action framing theory as a way to capture the process by which adherents of social movements attribute meaning. They argue framing can be divided into three tasks: diagnostic framing (identifying a problem and attributing it), prognostic framing (proposing a solution to identified problems), and motivational framing (generating a rationale for acting). Additionally, they identify three processes in frame construction and maintenance: discursive (acts of writing and speech), contested (changes made to a frame due to its contestation), and strategic (deliberative efforts to link frames to mobilise new supporters). Strategic framing processes can be broken further into frame bridging (tying two separate frames together), frame amplification (the invigoration of existing values or beliefs), frame extension (incorporating new views into a frame), and frame transformation (when frames are transformed radically to reflect new views).

Framing processes in the climate movement

Such framing processes are readily observable within the climate movement. Ever since the Rio Earth Summit in 1992, NGOs working at the international level had tended to organise under the auspices of the Climate Action Network (CAN), a coalition of environmental and development organisations based almost exclusively in Europe and North America. CAN was and remains a consensus-based umbrella group, but as the debate on climate change progressed two key groups became increasingly apparent within the climate movement. The key cleavage within the movement concerned how to frame the climate change challenge.

Northern groups have predominantly framed climate change as an environmental problem, with the effect that they have argued for incremental change within existing political and technology constraints, and focussed their campaigning on mitigation action (Gach Citation2019). Their framing on the climate challenge tends see climate change as solvable within current socio-economic systems, promote market, individual, and/or technological solutions, and present climate change as an apolitical issue where everyone has a role to play. We refer to this as the “climate action” frame in this paper, and observe that it is largely consistent with the explanations and expectations of the mainstream policymaking community (e.g IPCC Citation2018), if more radical in the specific actions it prescribes.

Southern social movement groups and their allies, by contrast, have predominantly framed climate change as a social problem. Following on from radical development theory, they have argued that inequitable structures associated with neoliberal capitalism are the root causes of both climate change and social inequity (Bäckstrand and Lövbrand Citation2016). Their framing of the climate challenge tends to see rapid, transformative change as necessary to protect the global South from the effects of climate change, including addressing fundamental questions of power imbalances in the climate negotiations. Focussed on local-level impacts and experiences, inequitable vulnerabilities on multiple-scales, they argue for grassroots direct-action, community voice and sovereignty, and tend to be deeply sceptical of attempts to depoliticise climate action (Schlosberg and Collins Citation2014). In this paper, we refer to this as the “CJ” frame. It became particularly visible in the lead up to COP15 in Copenhagen in 2009, where climate justice arguably surpassed climate action as the dominant social movement frame (Chatterton, Featherstone, and Routledge Citation2013; della Porta and Parks Citation2014; Hadden Citation2015). More recently, Northern social movements such as Fridays for the Future have increasingly mobilised around the CJ frame (Fisher Citation2019; Martiskainen et al. Citation2020). summarises commonly identified diagnostic, prognostic and motivational elements of the CJ frame.

Table 1. Elements of the climate justice frame (Adapted from Chatterton, Featherstone, and Routledge Citation2013; Schlosberg and Collins Citation2014; della Porta and Parks Citation2014; Bäckstrand and Lövbrand Citation2016; Gach Citation2019).

The development of the CJ frame was the result of social movement groups who explicitly connected local social and environmental justice struggles together to create a network of global solidarity to challenge the climate regime (Chatterton, Featherstone, and Routledge Citation2013; Claeys and Delgado Pugley Citation2017). As such, scholars generally locate the CJ frame within a broader EJ frame (Mohai, Pellow, and Roberts Citation2009; Chatterton, Featherstone, and Routledge Citation2013), just as the CJ movement is understood as positioned within an EJ movement and the climate movement within a broader environmental movement (Dorsey Citation2007; Baer Citation2011; Schlosberg and Collins Citation2014; della Porta and Parks Citation2014; Schlosberg, Collins, and Niemeyer Citation2017). “Environmental justice” was itself one of a handful of early collective action frames Benford and Snow (Citation2000) argued were so significant they termed them “master frames”. So just as the EJ movement is characterised by frame bridging strategies which tie together social and environmental struggles by recognising them as rooted in the same structures of inequality (Schlosberg Citation2013), CJ activists often associate with social justice movements (Grosse Citation2019). Moreover, though for analytical purposes we have separated “climate action” and “CJ” as frames, this separation is frequently challenged by frame bridging and frame extension processes in reality.

Theorising climate justice

It is important to remember, however, that in addition to the social movement framing of “climate justice” discussed above, the entire architecture of international climate action is predicated on the idea that the climate challenge must be addressed according to principles of justice. This is clearly established in Article 3, Principle 1 of the United Nationals Framework Convention on Climate Change, which states that

The Parties should protect the climate system for the benefit of present and future generations of humankind, on the basis of equity and in accordance with their common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities. (UNFCCC Citation1992)

A corresponding academic literature seeks to unpack and give substance to this principle, focussing on the distribution of the burdens and benefits of climate change mitigation and adaptation (Edwards Citation2021). This literature focusses on climate policymaking: who benefits from greenhouse gas emissions and how should they bear responsibility for mitigation and adaptation, how can we recognise the vast divergence in vulnerabilities and capabilities to respond, and how can we ensure representative and equitable procedural decision-making (Goodman Citation2009; Roberts and Parks Citation2006; Bulkeley, Edwards, and Fuller Citation2014). This literature establishes the basic proposition that climate justice is a fundamental element of addressing the climate challenge. Many of these ethical discussions about “climate justice” are reflected in the “climate action” social movement frame. For further discussion of the relationship between climate justice as an ethical principle and political project, see Edwards (Citation2021).

Studying XR’s framing processes and their engagement with climate justice

Due to its recent and rapid rise to prominence, there is very limited literature on XR itself, let alone on its framing processes or engagement with the CJ frame (though for some recent interventions, see Axon Citation2019; Gunningham Citation2019; Berglund and Schmidt Citation2020; Matthews Citation2020; Saunders, Doherty, and Hayes Citation2020; Slaven and Heydon Citation2020). XR’s own literature promotes itself as actively concerned with global justice and international solidarity, and the group has taken several actions displaying this. For instance, the boats brought to protests have been named after assassinated global South activists (Harrison and Tobin Citation2019), XR has an international solidarity working group (XR Citation2019a, 3), and XR has held events seeking to raise awareness of CJ concerns (see XR Citation2019b; XR Citation2019c; XR Citation2020c). Furthermore, there are clear parallels between XR’s holacratic structure and focus on grassroots collective action and the demands for popular sovereignty and focus on grassroots action which are usually associated with the CJ frame (Bäckstrand and Lövbrand Citation2016). The sub-group XR Bristol, for instance, has made statements recognising criticisms regarding the underrepresentation of BAME communities and lack of focus on global justice issues within it (see XR Bristol Citation2019). XR has also committed to widening the diversity of its membership and to engaging with a wider variety of movements as part of its 2020 strategy (XR Citation2020a, Citation2020b), although progress on this remains unclear due to a lack of publicly available information.

In other ways, though, XR’s self-appointed leadership and spokespeople past and present appear ambivalent to or even opposed to demands central to the CJ frame. In a training session for XR coordinators, co-founder Roger Hallam – who has since split from XR and founded a breakaway movement – was recorded being dismissive of leftist groups as alienating to the public (Morningstar Citation2019) and he separately argued on the podcast Politics Theory Other that a focus on the global South and/or identity politics would risk the movement’s popular appeal (Doherty Citation2019; cited in Kinniburgh Citation2020). Rupert Read, a senior spokesperson for the group, previously wrote of the “need to reign in immigration”, although he has since stressed XR should “make very clear that climate refugees are welcome here” (Kinniburgh Citation2020). Finally, despite the fact that an XR group in the USA, XR US, incorporated a fourth demand in April 2019 claiming the US Government should pay reparations to marginalised communities in the US and global South (XR US Citation2020), XR more broadly has yet to implement something similar. Global Justice Rebellion, an explicitly anticapitalist and antiracist offshoot of XR, claims this is to avoid alienating potential centre and right leaning allies (Poulter Citation2020). Given this apparent tension within XR and between various XR groups and XR’s leadership, it is important to further examine how the framing processes employed engage with the CJ frame (). In the next section, we attempt such an analysis, focussing on the diagnostic, prognostic and motivational frames of XR Norwich.

Examining the framing processes of XR Norwich

Our choice of XR Norwich was informed by practicality: we only had a short available time to conduct the empirical phase of the research during 2019, when the movement was rapidly growing in prominence, and we had access to this XR group through a gatekeeper member, who provided the initial contact. Snowball sampling was used to recruit further participants. After conducting two pilot interviews to refine interview technique (Kim Citation2011), in-depth interviews were conducted with 12 participants from XR Norwich between July and August 2019. Analytically, we adopted Benford and Snow’s (Citation2000) typology of collective action framing theory to understand the framing processes being employed. Interviews were designed to reveal diagnostic, prognostic, and motivational framing processes and participants’ views on CJ concerns. This was supplemented with inductive coding to overcome the problems with identifying group and individual variation identified by Lindekilde (Citation2014). Because of the focus of our study on how XR engages with CJ in its framing, we performed an initial grouping the participants according to their awareness and engagement with CJ (). Participants mainly identified as white and half described the group as mostly middle-class, and they fit into three main groups:

Group 1: these three participants (3, 4, & 6) were sympathetic towards several parts of the CJ frame (particularly its diagnostic elements), but felt XR shouldn’t engage with some of the issues and solutions the frame raises;

Group 2: these five participants (5, 7, 9, 10, 11) did not think XR should associate itself with most, if any, of the concerns raised by CJ; and

Group 3: two participants (1 & 2) who were highly engaged with CJ.Footnote1

Because Groups 1 and 2 account for the majority of participants, our framing analysis focusses on their action frames. Together, they represent the collective position of XR Norwich, though we use bold text to highlight differences between their framing in the analysis tables, and reflect on them in the text. We contextualise this discussion with reference to the more CJ-engaged Group 3.

The diagnostic, prognostic and motivational frames of XR Norwich

XR Norwich employed five main diagnostic frames (), and we can identify three themes: XR Norwich are clearly influenced and motivated by XR’s 8th Principle that no-one individual (and by extension, group) is to blame, assign individual responsibility rather than structural or elite responsibility, and see industrialised nations as responsible for climate change. Group 2 argued it was counter-productive to place blame on elites, and instead claimed it was the fault of “the system”. Despite this, though, these participants also expressed a strong belief that capitalism wasn’t incompatible with finding solutions to climate change, and finding alternatives within it was the best course of action (see Berglund and Schmidt Citation2020). Degrowth was the most commonly identified alternative. When subsequently asked explicitly, Group 1 placed responsibility for climate change on capitalism and, although hesitant to cast full blame, elite actors due to their dominant role within it.

Table 2. The diagnostic frames of XR Norwich.

Unlike in the CJ frame, XR Norwich did not see climate change as wholly a structural issue (; Roberts and Parks Citation2009). Instead, participants mostly identified greed and consumerism as the drivers of climate change and blamed a lack of awareness and “systems” for these. Participant 6 captured the group’s dominant diagnostic framing:

I think we need radical lifestyle changes and that needs to be driven by consumer power but also things like our food system need to change to make it easier for us. (Participant 6)

This combination of rational choice and systems thinking was held by many of the participants, and reflects the findings of the sustainable consumption literature that people do not engage in sustainable activities because they both are unaware of the damages of climate change but also bound to the systems they are in (O’Rourke and Lollo Citation2015; Middlemiss Citation2018).

Let us now consider the prognostic frames of XR Norwich (). The first observation is that technological innovation and individual action were dominant, aligning XR Norwich with the climate action frame, rather than the CJ frame (Gach Citation2019). Indeed, XR Norwich departed most strongly from the CJ frame on the issue of whether reparations should be offered to developing countries. Participants thought that there was limited appetite for reparations amongst the broader public and government, despite some sympathy towards the idea in theory. Again, Participant 6 captured the dominant view:

I’m hugely sympathetic towards the idea, but we have to stick to [XR’s] demands for the moment. Maybe when the UK government is on board we can bring them in and discuss it. (Participant 6)

Table 3. The prognostic frames of XR Norwich.

The most divisive issue within XR Norwich was whether XR should engage with other movements. The smaller Group 1 thought that XR should contact appropriate groups and discuss collaboration and reciprocal support (e.g. mutual attendance at protests) whereas the larger Group 2 thought engagement should be limited to pulling groups into XR’s sphere where interests align. This latter view – which was expressed by half the participants – suggests a disregard for the struggles of others and a lack of willingness to engage with their issues as linked to the same root causes. Our findings here correspond to those of Berglund and Schmidt (Citation2020), who argue that it makes for easier initial mobilisation but does not augur well for XR in the longer term.

Finally, let us consider the motivational frames of XR Norwich (). The primary motivational frame expressed by participants was that climate change was likely to affect everyone but nothing was being done to stop it. Moreover, they identified XR’s apolitical stance and its growing success as drivers of recent membership.

Table 4. The motivational frames of XR Norwich.

These frames clearly resonate and are consistent with XR’s broader framing processes. For instance, taking a strongly political stance would likely alienate supporters whose framing did not align with XR’s. However, these motivational frames do imply a dependence on the assumption that awareness of climate change and support for XR would be considered sensible to all educated individuals. This seems problematic given what we know about the relationship between political bias and belief in climate change (see Unsworth and Fielding Citation2014) and the strong incentive of some powerful corporate and political groups to stop climate action (Zhang et al., Citation2017). Arguably, this has repercussions for the group’s outreach policies, as presenting climate change as an apolitical or “post-political” issue both overlooks what others have argued are intrinsic issues of justice (Swyngedouw Citation2010), and could alienate potential supporters who are concerned with these issues (see our subsequent discussion of the CJ-aware members). Taking a more political stance would likely present barriers when talking to groups such as the UK government or NGOs (Bäckstrand and Lövbrand Citation2016), but on a local level it would make sense for XR to encourage discussions of these issues.

Participants argued that the group’s support networks (e.g. counselling services and support personnel at events) were core to internal mobilisation. The philosophy was the same for external mobilisation, with members emphasising XR Norwich as a group for likeminded and/or concerned people when meeting the public. The motivational frames employed suggest that XR Norwich thinks individuals are generally concerned with climate change and prioritises group harmony over political purity. This may prove to be an effective mobilising strategy for some people, and could be enough to reach the 3.5% population threshold that XR believes will lead to “system change” (see XR Citation2020d; , for a critique of the 3.5% aspiration, see Matthews Citation2020), but as will be discussed, it places XR Norwich outside the CJ frame.

Discussion

XR: a movement to halt climate change or promote climate justice?

Taken together, the core diagnostic, prognostic and motivational frames of XR Norwich align more strongly with the mainstream “climate action” frame associated with traditional, liberal environmental protest groups (see della Porta and Parks Citation2014) rather than the CJ frame (). Like these groups, XR Norwich is also socially homogenous. Seven participants said that XR Norwich was primarily white and six identified the group as mostly middle-class. These features, together with XR Norwich’s support networks and the holacratic structure of XR appear to explain XR Norwich’s remarkable unity compared with other environmental protest groups. Participant 4 summed up the feelings of seven participants in saying:

I’ve been involved with a few groups before, and XR is by far the most harmonious and unified. (Participant 4)

There was a strong sense from our study that this internal group cohesion was more important to XR Norwich members than ideological purity. The group’s members – who its framing processes are designed to mobilise (Snow Citation2004) – tend to be mobilised primarily by the environmental demands of XR. Seven participants went as far as to say that XR shouldn’t openly discuss social inequality as this would risk diluting its environmental message, even though it was apparent that conversations about inequality within the UK were occurring within the group. As the two most CJ-engaged participants (Group 3) put it:

… we’ve got two groups – lefties and liberals. Lefties are all about revolution and food security and stuff, whilst the liberals talk about love and plastic. (Participant 2)

To have incorporated more social justice stuff in the beginning would have been incredible, but what’s done is done. I think it’s more important to get the message out that (climate change inaction) is not ok. (Participant 1)

So even the most CJ-engaged participants prioritised group cohesiveness over ideological purity. The way the group does use the CJ frame supports this finding. Revisiting the group’s diagnostic, prognostic and motivational frames reveals that participants tended to incorporate CJ into their framing as an international rather than intranational concern, with the effect that the dominant understanding of CJ within XR Norwich was as “a concern for the impacts of climate change on the global South” (Participant 6). This is possibly because viewing CJ as a matter of international equity assuages the equity concerns of activists whilst avoiding more difficult topics concerning responsibility and inequality nearer to home (see Harvey Citation2018; Josette Citation2019). It is also consistent with the fact that eight participants said the term was frequently used during protests, but they themselves were often sceptical about the depth of engagement:

I don’t think most of them who chant climate justice (at XR Norwich protests) know what it means. It’s just a catchy chant for them. (Participant 5)

But eight participants did think XR Norwich was engaged with CJ, reporting that their involved with XR had deepened their understanding of CJ, and for Participants 1 and 2 (Group 3), CJ was a core motivator for their climate change activism. Those with prior knowledge of CJ believed their involvement with XR had deepened their understanding of it, but at the same time participants with greater awareness of CJ tended to report that they had learnt about it outside of XR, recognised that engagement with CJ by XR was currently limited, and indicated CJ was not a reason they were members.

This selective and partial engagement with CJ was reflected in XR Norwich’s solidarity connections to other related social movements. For instance, participants noted they had an information stall at Norwich Pride and were arranging a joint protest with Norwich teachers’ unions, but at the same time four participants reflected that a local environmental justice group was being criticised within XR Norwich for being too political by protesting migration policies. A similar pattern emerged in discussions about recruitment, which participants observed did not seek to engage a diversity of potential members. As one participant put it:

People are coming to us, so we aren’t really targeting groups. (Participant 9)

These incidences could be seen as examples of XR leveraging the legitimacy of other groups without engaging with their struggles. This view is problematic as the incorporation of diverse viewpoints and lived experiences have been key in making the Global Justice Movement’s claims regarding repeated injustice so potent (Fominaya Citation2010).

Although XR more broadly presents itself as highly engaged with CJ issues, it has faced criticism from the CJ movement for its lack of focus on structural causes and its limited engagement with marginalised communities. Our study of XR Norwich suggests that these criticisms have merit, since the group does display a lack of attention to diversity and the dominant framing of climate change is as an apolitical issue. For example, XR Norwich members had seen representatives from indigenous groups speaking at XR’s First International Rebellion Protest in April 2019 and were aware that XR Norwich had tweeted articles concerning indigenous struggles. Yet most were reluctant to include the demands of such groups within XR’s collective action frames. It appears that they were content, as Roosvall and Tegelberg (Citation2013) argue, to use such activists to represent the immediacy of climate change, whilst ignoring their political demands (e.g. for representation within the international climate regime), in the manner that the media often does. On the one hand, XR is engaging with indigenous issues and has highlighted some of the social elements of these in press releases (see XR Citation2019d), yet our findings suggest that XR Norwich still has a way to go engaging its membership with climate justice issues, embedding the political concerns of marginalised groups into its framing processes and engaging with external movements on equal terms.

The challenge of post-politics for XR

Our results show that participants from XR Norwich are deeply committed to an apolitical and individual-centred framing of the climate change problématique – traits which align it with the mainstream climate action frame. This is entirely consistent with XR’s emphasis on avoiding antagonisms (i.e. “blaming and shaming” – see ). Framing climate change as a physical problem and one requiring urgent scientific solutions often disregards the developmental needs of vulnerable communities, particularly those in the global South, in favour of fast mitigation technology such as carbon offset forestry (Forsyth Citation2014). By not fully committing to a socio-environmental narrative, XR's framing may further perceptions of climate change as a purely physical phenomenon which just happens to hit vulnerable communities hardest, rather than raising questions about why differentiated vulnerability develops to begin with. In this sense, XR Norwich’s framing processes appear to be subject to the false-consensus building criticism Swyngedouw (Citation2010) argues characterises “post-political” approaches to environmental governance. This framing is problematic because it hides corporate complicity in prolonging climate inaction and presents solutions that cast climate change as a physical phenomena which is solvable within market solutions (Dorsey Citation2007; Berglund and Schmidt Citation2020). The fact that XR has engaged with corporate sponsors and backers (Morningstar Citation2019) lends credence to this suggestion, since it opens it up to charges of promoting or at least being ambivalent to the prioritisation of a pro-business agenda over a social equity agenda.

Of course, the attachment of XR Norwich members to apolitical frames and the fact that it does not provide a critique of systemic issues may also reveal something about current political opportunity structures. Within the social movement literature, political opportunity structures refer to “the insight that the political context in which a movement emerges influences its development and potential impact” (Meyer Citation2004, 1). Political opportunities for social movements often arise during periods of social upheaval such as regime changes (McAdam Citation2017) or the 2008 Global Financial Crisis which birthed a raft of anti-austerity movements (della Porta Citation2015). In the US context, McAdam finds that the bipartisan dominance of neoliberal thinking combined with bitterly partisan politics has had the effect of limiting political opportunities for climate change-focused social movements, a finding which could be extended to the contemporary UK context (Lockwood Citation2013). This means that movements like XR have increasingly attempted to mobilise their own political opportunities. For XR, the notion of a “climate emergency” has fulfilled this purpose, just as pro-environment actors in other contexts have sought to create political opportunities by finding synergies between environmental demands and other demands focussed on the maintenance of rural livelihoods (Piggot Citation2018). Perhaps what XR has demonstrated is that there is an appetite for mass-mobilisation on climate change amongst the broader public, but not one which sees a critique of capitalism as an essential element of climate action. However, if – as its handbook suggests – XR sees itself as actively engaged with CJ and uses the terminology of the CJ movement (see Knight Citation2019), it cannot ignore critiques of capitalism without risking perpetuating global injustices, allowing for co-option by elite actors, and ultimately alienating a significant potential constituency (see Berglund and Schmidt Citation2020). Further research in this area is vital.

Towards a more nuanced analysis of frames within XR

Our results also point to some innovations required within framing theory. Collective action framing theory has often assumed a top-down focus on social movements, with analysis focussing on the frames of lead actors (Snow Citation2004). However, empirical studies of the frame alignment of protest groups indicate that the frames of rank-and-file protestors often vary extensively from their movement’s overarching frames (Ketelaars, Walgrave, and Wouters Citation2014). Wahlström, Wennerhag, and Rootes (Citation2013), for instance, found that the prognostic frame(s) of protestors at three COP15 protests aligned more with the mainstream climate action frame than the CJ frame of the organisers. Building on this, scholars have argued that this variance can be explained by an individual’s willingness to accept a frame due to their predisposition (Brewer Citation2003), their exposure to alternative information, and the salience of a political issue (Ketelaars, Walgrave, and Wouters Citation2017). Recognising this, Ketelaars, Walgrave, and Wouters (Citation2017) argue the literature should more closely study these sub-frame interactions.

Our results support this call for more attention to the framing processes of rank-and-file members of XR and other protest groups. Whilst our study is focussed on just one XR sub-group and did not seek to comprehensively analyse the views of XR’s leadership, it raises the question of whether the reluctance of XR Norwich members to engage with the CJ frame is because XR’s leadership has not adequately conveyed CJ concerns to its members. Where XR does engage with CJ, it does so in a rather tokenistic manner such as employing slogans of international solidarity in its public actions. Further research is necessary to understand whether this is a deliberate framing strategy or an unintended outcome of XR’s mobilisation model. Regardless, however, XR will not be able to sidestep conversations about CJ for long, and CJ could emerge as a point of cleavage within the movement as XR supporters become increasingly exposed to alternative frames and criticisms of the group, leading to a greater variation in frame resonance amongst grassroots members (Ketelaars, Walgrave, and Wouters Citation2017). This has already happened to some extent in the case of Global Justice Rebellion (see also Berglund and Schmidt Citation2020). Nearly half the participants in our study (Groups 1 & 3) were already aware of many of the criticisms of XR and showed they were engaged with literature outside of the XR mainstream. Though our results suggest participants were unlikely to leave XR Norwich over these, some participants hinted at the rise of factions within XR Norwich such as the left/liberal split previously noted. Schlembach (Citation2011) found in his study of Climate Camp UK that internal dynamics and disagreements shaped the frames and policies of the group as they shifted to reconcile differences or remove opposition, reflecting the theory of frame disputes developed by Benford and Snow (Citation2000). Such disputes can lead to positive developments in framing, but can also lead to persistent schisms which destroy the cohesion and mobilising potential of a social movement (Halvorsen Citation2015). In this context, a larger longitudinal study of select XR sub-groups and XR’s leadership would be valuable to better understand their character(s) and course(s) and to develop the emerging understanding of sub-frame interactions (Ketelaars, Walgrave, and Wouters Citation2017).

Conclusion

Given its rapid rise in the public consciousness, XR is ripe for analysis. This paper has analysed the diagnostic, prognostic and motivational frames of XR Norwich to examine the engagement of that group with climate justice. Though participants mobilised a variety of frames, XR Norwich generally framed climate change in an apolitical way, focussing on individual responsibility for climate action rather than structural drivers of climate inaction. The homogeneity and unity-focus of XR Norwich proved useful in explaining the rather under-developed engagement with CJ as a collective action frame, as did the need for the group to create its own political opportunity structures (and its success in doing so). Whilst we have confidence in our findings with regard to XR Norwich, the group’s holacratic structure makes it difficult to conclude that this study is representative of XR more broadly. Despite this, our findings do point to a clear need for further research with XR sub-groups and for comparative research with the XR leadership to establish how the framing processes of sub-groups reflect and interact with the meta-frames mobilised by XR leaders. A longitudinal study of these actors and groups would also be useful for exploring the factionalism we identified and would allow for further theoretical insight into the interactions of sub-frames within social movements. XR – along with Fridays for the Future – is one of the most dynamic environmental social movements to emerge in recent years. The extent to which XR internalises CJ and the CJ frames it develops will likely be significant in shaping the direction of the climate movement in the near future. Further research is critically needed to understand both the potential and pitfalls of XRs framing processes for a just and sustainable settlement to the climate crisis.

Acknowledgements

The study on which this paper was based was conducted as part of an MSc degree at the University of East Anglia. Thanks to those who agreed to be interviewed as part of this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 A further two participants (8 & 12) were interviewed, but did not give permission to include their results in publications arising from the study, hence the discontinuous numbering.

References

- Axon, S. 2019. “Warning: Extinction Ahead! Theorizing the Spatial Disruption and Place Contestation of Climate Justice Activism.” Environment, Space, Place 11 (2): 1–26.

- Bäckstrand, K., and E. Lövbrand. 2016. “The Road to Paris: Contending Climate Governance Discourses in the Post-Copenhagen era.” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 21: 1–19.

- Baer, H. A. 2011. “The International Climate Justice Movement: A comparison with the Australian climate movement.” The Australian Journal of Anthropology 22 (2): 256–260.

- BBC News. 2019a. Norwich Road Protesters Removed from Council Meeting. Accessed 29 August 2019. https://www.bbc.com/news/amp/uk-england-norfolk-47201406.

- BBC News. 2019b. UK Parliament Declares Climate Change Emergency. Accessed 29 August 2019. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-48126677.

- Benford, R. D., and D. A. Snow. 2000. “Framing Processes and Social Movements: An Overview and Assessment.” Annual Review of Sociology 26 (1): 611–639.

- Berglund, O., and D. Schmidt. 2020. Extinction Rebellion and Climate Change Activism: Breaking the Law to Change the World. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Brewer, P. R. 2003. “Values, Political Knowledge, and Public Opinion About gay Rights: A Framing-Based Account.” Public Opinion Quarterly 67 (2): 173–201.

- Bulkeley, H., G. A. S. Edwards, and S. Fuller. 2014. “Contesting Climate Justice in the City: Examining Politics and Practice in Urban Climate Change Experiments.” Global Environmental Change 25: 31–40.

- Chatterton, P., D. Featherstone, and P. Routledge. 2013. “Articulating Climate Justice in Copenhagen: Antagonism, the Commons, and Solidarity.” Antipode 45 (3): 602–620.

- Claeys, P., and D. Delgado Pugley. 2017. “Peasant and Indigenous Transnational Social Movements Engaging with Climate Justice.” Canadian Journal of Development Studies/Revue Canadienne D’études du Développement 38 (3): 325–340.

- Cowan, L. 2019. Are Extinction Rebellion Whitewashing Climate Justice?. Accessed 29 August 2019. http://gal-dem.com/extinction-rebellion-risk-trampling-climate-justice-movement/.

- della Porta, D. 2015. Social Movements in Times of Austerity: Bringing Capitalism Back Into Protest Analysis. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

- della Porta, D., and M. Diani. 2009. Social Movements: An Introduction. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

- della Porta, D., and L. Parks. 2014. “Framing Processes in the Climate Movement: From Climate Change to Climate Justice’.” In Routledge Handbook of the Climate Change Movement, edited by M. Dietz, and H. Garrelts, 19–30. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Doherty, A. 2019. Roger Hallam on Extinction Rebellion. Politics Theory Other. Accessed 09 May 2020. https://soundcloud.com/poltheoryother/49-roger-hallam-on-extinction-rebellion.

- Dorsey, M. K. 2007. “Climate Knowledge and Power: Tales of Skeptic Tanks, Weather Gods, and Sagas for Climate (in) Justice.” Capitalism Nature Socialism 18 (2): 7–21.

- Edie. 2019. Extinction Rebellion: Role of Business in Society Is Being Defined by Climate Change. Accessed 29 August 2019. https://www.edie.net/news/9/Extinction-Rebellion–Role-of-business-in-society-being-defined-by-climate-change/.

- Edwards, G. A. S. 2021. “Climate Justice.” In Environmental Justice: Key Issues, edited by B. Coolsaet. London: Routledge.

- Fisher, D. R. 2019. “The Broader Importance of #FridaysForFuture.” Nature Climate Change 9 (6): 430–431.

- Fominaya, C. F. 2010. “Creating Cohesion from Diversity: The Challenge of Collective Identity Formation in the Global Justice Movement.” Sociological Inquiry 80 (3): 377–404.

- Forsyth, T. 2014. “Climate Justice is not Just ice.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 54: 230–232.

- Futrell, R. 2003. “Framing Processes, Cognitive Liberation, and NIMBY Protest in the US Chemical-Weapons Disposal Conflict.” Sociological Inquiry 73 (3): 359–386.

- Gach, E. 2019. “Normative Shifts in the Global Conception of Climate Change: The Growth of Climate Justice.” Social Sciences 8 (1): 24.

- Gayle, D. 2019. Does Extinction Rebellion have a Race Problem?. Accessed 09 May 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/oct/04/extinction-rebellion-race-climate-crisis-inequality.

- Giugni, M., and M. T. Grasso. 2015. “Environmental Movements in Advanced Industrial Democracies: Heterogeneity, Transformation, and Institutionalization.” Annual Review of Environment and Resources 40: 337–361.

- Goodman, J. 2009. “From Global Justice to Climate Justice? Justice Ecologism in an era of Global Warming.” New Political Science 31 (4): 499–514.

- Grosse, C. 2019. “Climate Justice Movement Building: Values and Cultures of Creation in Santa Barbara, California.” Social Sciences 8 (3): 79.

- Gunningham, N. 2019. “Averting Climate Catastrophe: Environmental Activism, Extinction Rebellion and Coalitions of Influence.” King’s Law Journal 30 (2): 194–202.

- Hadden, J. 2015. Networks in Contention. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Halvorsen, S. 2015. “Taking Space: Moments of Rupture and Everyday Life in Occupy London.” Antipode 47 (2): 401–417.

- Hannant, D. 2019. ‘The Best Example of People Power’ - Meet Some of the Faces Behind Extinction Rebellion Norwich’. Accessed 29 August 2019. https://www.edp24.co.uk/news/environment/meet-some-of-the-faces-of-xr-norwich-1-6150563.

- Harrison, S., and S. Tobin. 2019. XR Summer Rebellion Begins. Accessed 29 August 2019. https://theecologist.org/2019/jul/15/xr-summer-rebellion-begins.

- Harvey, F. 2018. Climate Change Aid to Poor Nations Lags Behind Paris Pledges. Accessed 29 August 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2018/may/03/climate-change-aid-poor-nations-paris-cop21-oxfam.

- IPCC. 2018. Global Warming of 1.5C: Summary for Policymakers. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. http://www.ipcc.ch/report/sr15/ (accessed 24 October 2018).

- Jamison, A. 2010. “Climate Change Knowledge and Social Movement Theory.” Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 1 (6): 811–823.

- Johnson, S. 2019. Cyclists hit Norwich Streets to Disrupt Traffic. Accessed 29 August 2019. https://www.eveningnews24.co.uk/news/extinction-rebellion-activists-critical-mass-bike-ride-norwich-rebel-riders-climate-change-1-6107839.

- Josette, N. 2019. People of Colour Are the Most Impacted by Climate Change, Yet Extinction Rebellion Is Erasing Them from the Conversation. Accessed 29 August 2019. https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/extinction-rebellion-arrests-london-protests-climate-change-people-of-colour-global-south-a8879846.html.

- Ketelaars, P., S. Walgrave, and R. Wouters. 2014. “Degrees of Frame Alignment: Comparing Organisers’ and Participants’ Frames in 29 Demonstrations in Three Countries.” International Sociology 29 (6): 504–524.

- Ketelaars, P., S. Walgrave, and R. Wouters. 2017. “Protesters on Message? Explaining Demonstrators’ Differential Degrees of Frame Alignment.” Social Movement Studies 16 (3): 340–354.

- Kim, Y. 2011. “The Pilot Study in Qualitative Inquiry: Identifying Issues and Learning Lessons for Culturally Competent Research.” Qualitative Social Work 10 (2): 190–206.

- Kinniburgh, C. 2020. “Can Extinction Rebellion Survive?” Dissent 67 (1): 125–133.

- Knight, S. 2019. “Introduction: The Story So Far.” In This Is Not A Drill: An Extinction Rebellion Handbook, edited by C. Farrell, A. Green, S. Knight, and W. Skeaping, 9–21. Milton Keynes: Penguin Random House UK.

- Lakoff, G. 2010. “Why it Matters how we Frame the Environment.” Environmental Communication 4 (1): 70–81.

- Lindekilde, L. 2014. “Discourse and Frame Analysis.” In Methodological Practices in Social Movement Research, edited by D. della Porta, 201–236. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lockwood, M. 2011. “Does the Framing of Climate Policies Make a Difference to Public Support? Evidence from UK Marginal Constituencies.” Climate Policy 11 (4): 1097–1112.

- Lockwood, M. 2013. “The Political Sustainability of Climate Policy: The Case of the UK Climate Change Act.” Global Environmental Change 23 (5): 1339–1348.

- Martiskainen, M., S. Axon, B. K. Sovacool, S. Sareen, D. Furszyfer Del Rio, and K. Axon. 2020. “Contextualizing Climate Justice Activism: Knowledge, Emotions, Motivations, and Actions among Climate Strikers in six Cities.” Global Environmental Change 65: 102180.

- Matthews, K. 2020. “Social Movements and the (mis)use of Research: Extinction Rebellion and the 3.5% Rule.” Interface: A Journal for and About Social Movements 12 (1): 591–615.

- McAdam, D. 2017. “Social Movement Theory and the Prospects for Climate Change Activism in the United States.” Annual Review of Political Science 20: 189–208.

- Meyer, D. S. 2004. “Protest and Political Opportunities.” Annual Review of Sociology 30: 125–145.

- Middlemiss, L. 2018. Sustainable Consumption: key Issues. Addington: Routledge.

- Mohai, P., D. N. Pellow, and J. T. Roberts. 2009. “Environmental Justice.” Annual Review of Environment and Resources 34: 405–430.

- Morningstar, C. 2019. Extinction Rebellion Training, or How to Control Radical Resistance from the Obstructive Left. Accessed 29 August 2019. http://www.wrongkindofgreen.org/category/non-profit-industrial-complex-organizations/organizations/amnesty-international/.

- O’Rourke, D., and N. Lollo. 2015. “Transforming Consumption: From Decoupling, to Behavior Change, to System Changes for Sustainable Consumption.” Annual Review of Environment and Resources 40 (1): 233–259.

- Piggot, G. 2018. “The Influence of Social Movements on Policies That Constrain Fossil Fuel Supply.” Climate Policy 18 (7): 942–954.

- Poulter, J. 2020. Extinction Rebellion’s Tube Protest Isn’t the Last of Its Problems. Accessed 09 May 2020. https://www.vice.com/en_uk/article/59nq3b/extinction-rebellion-tube-disruption-criticism.

- Roberts, J. T., and B. Parks. 2006. A Climate of Injustice: Global Inequality, North-South Politics, and Climate Policy. Cambridge: MIT press.

- Roberts, J. T., and B. C. Parks. 2009. “Ecologically Unequal Exchange, Ecological Debt, and Climate Justice: The History and Implications of Three Related Ideas for a new Social Movement.” International Journal of Comparative Sociology 50 (3-4): 385–409.

- Roosvall, A., and M. Tegelberg. 2013. “Framing Climate Change and Indigenous Peoples: Intermediaries of Urgency, Spirituality and de-Nationalization.” International Communication Gazette 75 (4): 392–409.

- Saunders, C., B. Doherty, and G. Hayes. 2020. A New Climate Movement? Extinction Rebellion’s Activists in Profile. Guildford: Centre for the Understanding of Sustainable Prosperity: CUSP Working Paper No. 25.

- Schlembach, R. 2011. “How do Radical Climate Movements Negotiate Their Environmental and Their Social Agendas? A Study of Debates Within the Camp for Climate Action (UK).” Critical Social Policy 31 (2): 194–215.

- Schlosberg, D. 2013. “Theorising Environmental Justice: the Expanding Sphere of a Discourse.” Environmental Politics 22 (1): 37–55.

- Schlosberg, D., and L. B. Collins. 2014. “From Environmental to Climate Justice: Climate Change and the Discourse of Environmental Justice.” Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 5 (3): 359–374.

- Schlosberg, D., L. B. Collins, and S. Niemeyer. 2017. “Adaptation Policy and Community Discourse: Risk, Vulnerability, and Just Transformation.” Environmental Politics 26 (3): 413–437.

- Shand-Baptiste, K. 2019. Extinction Rebellion's Hapless Stance on Class and Race is a Depressing Block to its Climate Justice Goal. Accessed 09 May 2020. https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/extinction-rebellion-climate-crisis-race-class-london-arrests-xr-a9156816.html.

- Slaven, M., and J. Heydon. 2020. “Crisis, Deliberation, and Extinction Rebellion.” Critical Studies on Security 8 (1): 59–62.

- Snow, D. A. 2004. “Framing Processes, Ideology, and Discursive Fields.” The Blackwell Companion to Social Movements 1: 380–412.

- Snow, D. A., and R. D. Benford. 1988. “Ideology, Frame Resonance, and Participant Mobilization.” International Social Movement Research 1: 197–218.

- Snow, D. A., and R. D. Benford. 1992. “Master Frames and Cycles of Protest.” Frontiers in Social Movement Theory 133: 155–200.

- Snow, D., A. Tan, and P. Owens. 2013. “Social Movements, Framing Processes, and Cultural Revitalization and Fabrication.” Mobilization: An International Quarterly 18 (3): 225–242.

- Swyngedouw, E. 2010. “Apocalypse Forever?” Theory, Culture & Society 27 (2-3): 213–232.

- UNFCCC. 1992. United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/convention_text_with_annexes_english_for_posting.pdf.

- Unsworth, K. L., and K. S. Fielding. 2014. “It’s Political: How the Salience of One’s Political Identity Changes Climate Change Beliefs and Policy Support.” Global Environmental Change 27: 131–137.

- Wahlström, M., M. Wennerhag, and C. Rootes. 2013. “Framing “The Climate Issue”: Patterns of Participation and Prognostic Frames among Climate Summit Protesters.” Global Environmental Politics 13 (4): 101–122.

- Welsh, T. 2019. We’ve had Quite Enough of the Law-Breaking Environmental Fanatics of Extinction Rebellion. Accessed 29 August 2019. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2019/06/02/had-quite-enough-law-breaking-environmental-fanatics-extinction/.

- Wretched of the Earth. 2019. An Open Letter to Extinction Rebellion. Accessed 29 August 2019. https://www.redpepper.org.uk/an-open-letter-to-extinction-rebellion/.

- XR. 2019a. Extinction REBELLION: new International Solidarity Network as Activists in Ghana Declare Pan Afrikan Climate Emergency. Accessed 29 August 2019. https://rebellion.earth/2019/02/27/extinction-rebellion-new-international-solidarity-network-as-activists-in-ghana-declare-pan-afrikan-climate-emergency/.

- XR. 2019b. XR Honours the Defenders: Vigil for Murdered Earth Protectors. Accessed 29 August 2019. https://rebellion.earth/event/xr-honour-the-defenders-vigil-for-murdered-earth-protectors/.

- XR. 2019c. #EverybodyNow: London’s Rebellion on Track to be FIVE Times Bigger than April. Accessed 09 May 2020. https://rebellion.earth/2019/10/04/everybodynow-londons-rebellion-on-track-to-be-five-times-bigger-than-april/.

- XR. 2019d. Extinction Rebellion UK Hold BlackRock to Account and Announce ‘Boycott for Amazonia’. Accessed 09 May 2020. https://rebellion.earth/2019/11/15/extinction-rebellion-uk-hold-blackrock-to-account-and-announce-boycott-for-amazonia/.

- XR. 2020a. The Mass Mobilisation: UK XR Mobilisation Plan Summary. Accessed 09 May 2020. https://docs.google.com/document/d/1DqjAtvsVclAAcZ2TA2iGImP8XeXUV7Uq_4mDfG19Wg4/edit.

- XR. 2020b. Extinction Rebellion UK Launch New Strategy: In 2019 we Demanded Change. In 2020 we Begin Building the Alternative. Accessed 09 May 2020. https://rebellion.earth/2020/02/12/extinction-rebellion-uk-launch-new-strategy-in-2019-we-demanded-change-in-2020-we-begin-building-the-alternative/.

- XR. 2020c. Climate Is a Women’s Issue: Women Across the World Say ‘NO!’ to Climate Inequality. Accessed 09 May 2020. https://rebellion.earth/2020/03/08/climate-is-a-womens-issue-women-across-the-world-say-no-to-climate-inequality/.

- XR. 2020d. About Us. Accessed 09 May 2020. https://rebellion.earth/the-truth/about-us/.

- XR Bristol. 2019. An Open Letter Response to our Diversity and Inclusivity Issue. Accessed 29 August 2019. https://xrbristol.org.uk/2019/08/16/an-open-letter-response-to-our-diversity-issue/.

- XR Norwich. 2020. Extinction Rebellion Norwich. Accessed 09 May 2020. https://www.facebook.com/xrnorwich/.

- XR US. 2020. Extinction Rebellion US Demands. Accessed 29 August 2019. https://xrebellion.org/xr-us/demands.

- Zand. 2019. My Six Months with Extinction Rebellion. Accessed 29 August 2019. https://www.bbc.co.uk/bbcthree/article/66227e29-405e-44c1-bd6c-5ac33308cca0.

- Zhang, H. B., H. C. Dai, H. X. Lai, and W. T. Wang. 2017. “US Withdrawal from the Paris Agreement: Reasons, Impacts, and China’s Response.” Advances in Climate Change Research 8 (4): 220–225.