ABSTRACT

Urban community gardens provide learning environments for diverse groups, including those who may be experiencing health and social inequalities such as residents in social housing communities. Learning to grow fresh food in safe social spaces provides individuals with opportunities to increase awareness of their personal wellbeing and community life. This paper reports on the findings of a research study that explored broader impacts of a community gardening programme on 42 adult residents living in social housing estates in Sydney, Australia. The mixed-methods study design captured participants’ self-perceived benefits of community gardening across six new sites. A final sample of 23 participants across the sites completed both the Sense of Community Index 2 and the Personal Wellbeing Index questionnaires at pre- and post-test (following six to seven months of being involved in the programme). Focus groups involved 42 participants from all six sites. Perceived benefits included enhanced awareness of their overall health and wellbeing, new interest in growing fresh food, enjoyment of shared produce and recipes, feelings of happiness, frequent socialisation and community connectedness. The findings highlight the impactful role of community gardens as effective local learning environments that promote psychological wellbeing and community connection in underserved communities. We conclude by reinforcing the need for sustainable community gardens for addressing social inequality and promoting multiple psychosocial benefits.

Introduction

In recent times, urban community gardening has transformed into a popular worldwide trend encouraging public participation, whereby urban residents grow fresh food together and engage in sustainable practices (Cumbers et al. Citation2018; Hake Citation2017; Lanier, Schumacher, and Calvert Citation2015; Saldivar-Tanaka and Krasny Citation2004; Spilková Citation2017). Egli, Oliver, and Tautolo (Citation2016) found that in space-poor cities, community gardens contributed significantly towards local food production and consumption through growing fresh produce, including fruit, vegetables and herbs. Collective gardening spaces kindle an interest in growing produce, leading to better dietary practices and improving health behaviours (Audate et al. Citation2019; de Bell et al. Citation2020). The space and the time spent within community gardens are perceived as significant for social connectedness, such as integration of migrants and refugee populations (Harris, Minnis, and Somersat Citation2014; Hartwig and Mason Citation2016; Lapina Citation2017). When viewed in this context, urban community gardens have more to offer than simply growing fresh food (Truong et al. Citation2018).

Glover, Shinew, and Parry (Citation2005, 79) defined a community garden as “an organized, grassroots initiative whereby a section of land is used to produce food or flowers or both in an urban environment for the personal use or benefit of its members”. This paper reports on a study conducted in collaboration with the Royal Botanic Garden and Domain Trust (RBG&DT) in Sydney, Australia, and the Department of Family and Community Services, New South Wales (NSW), to examine the impact of the Community Greening programme on the perceived health, psychological wellbeing and social benefits in social housing communities in NSW. We begin by providing background information on the Community Greening programme, then an overview of the study. We follow this with a review of relevant literature, a discussion of the study design, and then key findings and discussion. The paper concludes by outlining limitations, implications and recommendations for future research.

In 1999, RBG&DT collaborated with the Department of Housing NSW for a partnership programme entitled Community Greening. The Community Greening programme aimed to empower vulnerable communities to create, visit, use and enjoy green spaces and the incorporated health, training, economic and social benefits (RBG&DT Citationn.d.). The course offered social and educational mentoring support for participants, facilitating community gardens in social housing estates across NSW. Since its inception in 1999, the programme has supported 521 community and youth gardens in a wide cross-section of local communities, and currently, 70% are still active (RBG&DT Citation2020).

Community gardens may not be accessible to all populations despite their popularity and usefulness as places for individuals to collaborate alongside cultivating fresh food and social skills. The designers of the Community Greening programme viewed it as an entry point to focus on community development and connect stakeholders with service providers (RBG&DT Citationn.d.). In this context, the Community Greening programme are initiated by key stakeholders, as a strategic and cost-effective partnership to support social housing residents. This strategic partnership has been repeatedly shown to enhance their housing experiences through hands-on engagement with community gardening.

The programme under investigation, develops new gardening sites in social housing estates and holds related educational workshops for residents. The workshops are designed by RBG&DT to cultivate knowledge and experience in building garden beds, growing fresh produce, composting, starting worm farms, managing and maintaining the garden, soil management and understanding gardening materials. In this present study, RBG facilitators provided support monthly at each site and noted variability between participants with regard to their engagement with the gardens. These outreach events consisted of one-hour hands-on gardening, delivering educational workshops or offering gardening advice. Most participants gardened a minimum of one day per week, whilst those with greater motivational levels ritually attended daily. The minority were more variable or sporadic, attending every second day for a duration of 10–30 min. However, a word of caution is needed. As these gardens were located within social housing developments, it was difficult to directly monitor the attendance level other than through the anecdotal success of the garden and physical appearance upon visitations.

The Community Greening programme’s gardening courses promote a lifelong learning process where several facets of collaborative teaching, experiential learning and personal development merge to achieve the programme’s objectives. The programme’s target population includes disadvantaged or underserved communities, minority ethnic groups, those over the age of 65, and people with disabilities (RBG&DT Citationn.d.). In particular, social housing communities are typically located in areas considered to be disadvantaged, where access to material and social resources is limited (Australian Bureau of Statistics Citation2018).

Largely populated metropolitan cities such as Sydney reflect multilayered inequalities within and across diverse demographics. Social housing residents, such as those participating in this programme, experience many inequalities. At the outset, researchers envisaged the housing estate residents would enjoy their participation in a variety of ways, including learning through their local environment about gardening and building community connections. illustrates an overview of Community Greening programme activities.

Table 1. Overview of community greening programme activities.

Community gardens as local learning environments

The overall impact of community gardening has gained both awareness and appreciation across the multidisciplinary academic literature (Malberg Dyg, Christensen, and Peterson Citation2020). Gardening in shared community spaces provides residents with opportunities for place-based learning and to care for the local natural environment (Krasny and Tidball Citation2009). Discovering new food varieties and appreciating the role of different life forms in gardening offers an additional benefit. When coupled with waste, land and water management, the educational and sociological benefits are profound (Ochoa et al. Citation2019). Ohmer et al. (Citation2009) evaluated the ways in which community conservation and gardening programmes transform urban distressed areas into pockets of nature and food production. Their study revealed participants developed a bond with other gardeners in the neighbourhood and improved the sense of community. Community gardening expands social capital (Christensen Citation2017) and can strengthen family relationships (Carney et al. Citation2012). Such forms of community engagement are defined by (Hake Citation2017, 26) as “social organisation of deliberate, systematic, and sustained learning activities”. Hake (Citation2017) also asserts that in addition to reciprocity, gardeners acquire newfound knowledge, technical skills and reawakened senses whilst immersed in the outdoor environment and develop innovative ways to communicate.

The formal and informal multifunctioning environments of community gardens provide interactive lived space, enabling the emergence of new experiences, meanings and reflections in gardeners. The psychosocial acts of gardening and the physical garden space signify special roles, highlighting community of practice where learners observe, imitate, interact and learn skills of life (Firth, Maye, and Pearson Citation2011). The local learning environment of a community garden guides lived experience (Hake Citation2017). Such lived experience is interrelational in that learners share and appreciate each other’s life contexts, life stories, language and cultural diversities in a pedagogical manner and bond as community members (Glover Citation2004). Most importantly, for low-income and vulnerable populations, this kind of interrelationality reinforces learning engagement, assisting participants to develop a distinct awareness of integrating food production with civic engagement and environmental stewardship (Krasny and Tidball Citation2009; Malberg Dyg, Christensen, and Peterson Citation2020). The opportunity for interrelationality present in community gardens creates a context for positive social environments and learning experiences, with the potential for positively affecting participants’ further education and employment.

Observing gardens as living environments, Bowker and Tearle (Citation2007) contextualised school gardening for its primary role as an informal and experiential learning environment. They acknowledged the benefits of working in small-scale gardens for children’s construction of new knowledge, peer interaction, skill development and values (Truong, Gray, and Ward Citation2016). Similarly, urban community gardens are sites where examples of goal setting and effective management with skilled instructors could initiate behaviour changes with vulnerable populations (Kingsley and Townsend Citation2006; Kingsley, Foenander, and Bailey Citation2019; Kingsley, Townsend, and Henderson-Wilson Citation2009). With specific design, and links to social welfare policies, the gardens could be advantageous in capacity building.

Community gardening addressing social and health inequalities

Contemporary research has amplified the significant role of urban green spaces and gardens in benefitting society. This is especially true for people experiencing inequities in terms of their health and wellbeing, social connection and cohesiveness and, most importantly, reconnecting with the natural world (Bleasdale, Crouch, and Harlan Citation2011; Djokić et al. Citation2018; Hoffimann, Barros, and Ribeiro Citation2017; Lee and Maheswaran Citation2011). Community gardens facilitate the transfer of and extend knowledge beyond personal levels, empowering whole communities, and access to local community gardens contributes towards reducing social inequalities through access to fresh food (Miller Citation2015) and may potentially help in closing existing gaps in social and health inequalities.

In their research on a garden-based learning model in education, Desmond, Grieshop, and Subramaniam (Citation2004) underlined school gardens as powerful actors in motivating both children and their families to choose better nutrition and health behaviours. They noted gardening offered life education for children which enabled them to transfer the same to their families, especially if they came from poorer economic backgrounds. Malberg Dyg, Christensen, and Peterson (Citation2020) examined research literature published between 1980 and 2017 for the effects of community gardens on the psychological wellbeing of vulnerable participants, such as people from ethnic minority, refugee, low-income and food-insecure backgrounds. The authors acknowledged the positive effects of collective gardening on self-esteem, self-awareness and independence. Additionally, Malberg Dyg, Christensen, and Peterson (Citation2020) found improved nutritional and associated health behaviours. Further evidence-based research is needed to strengthen these existing findings. Specifically, more data are needed to explore the outcomes of community gardening programmes with vulnerable populations, such as those in social housing communities.

Factors such as health status (both physical and mental), cultural and linguistic differences, low level of confidence and lack of motivation may affect participation more significantly in social housing communities. In their study of 115 participants involved in community gardening programmes from a disadvantaged neighbourhood in the United States, Booth et al. (Citation2018) observed that regular participation was a key determinant for achieving outcomes, especially better health behaviours and community life. Participation improved with stimulating garden space, varieties of produce, efficient programme staff and diversity of participants’ languages, cultures and educational levels. The combined presence of such features contributed to the efficacy of garden environments as significant psychosocial capacity-building support.

Urban community gardening can be both an individual and collective experience for a wide range of people and communities with a background of vulnerabilities, disadvantages, or sociocultural and economic inequities. Population groups deemed vulnerable include refugees, immigrants, people with disabilities and minority communities who have diverse cultural capital. Researchers have asserted these population groups often may not have their voices heard and have fewer opportunities for exposure to and enjoyment of green spaces in urban environments (Hartwig and Mason Citation2016; Lapina Citation2017; Martin et al. Citation2017). Often, such groups living in social housing and in low-income neighbourhoods with inadequate housing conditions may have restricted access to green space and community gardening (Bleasdale, Crouch, and Harlan Citation2011; Hoffimann, Barros, and Ribeiro Citation2017; Martin et al. Citation2017). Correlated with low economic status, issues of poor diet and nutrition, and minimal focus on health and psychological wellbeing, accessing further education and employment can affect these marginalised groups deeply (Bleasdale, Crouch, and Harlan Citation2011; Martin et al. Citation2017). Despite these studies, research evidence is either sporadic or inadequate in registering the point of community gardens’ agency in the psychological wellbeing and community connection of vulnerable populations. This gap has been identified by scholars as a lack of evidence concerning how these espoused benefits for general populations translate to marginalised and vulnerable communities (Kingsley et al. Citation2021; Malberg Dyg, Christensen, and Peterson Citation2020). In light of this research gap, we explored residents’ perceptions of community gardens as learning environments that support psychological wellbeing and community connection.

Methods

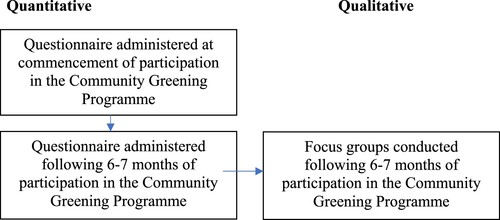

The present study was conducted by RBG&DT in six new Community Greening sites located in Sydney, NSW, Australia. The research was designed and implemented in collaboration with key stakeholders, including representatives from the NSW Department of Family and Community Services and the Community Greening programme of RBG&DT. This co-design process ensured that the research was meaningful for end users whilst maintaining the integrity of the research findings for which the research team had responsibility. A mixed-methods design (Creswell Citation2018) was adopted to measure changes reported by participants in community gardening over a period of six to seven months. Self-reported questionnaires collected at two time points (commencement and six to seven months later) and focus group interviews were used to gather primary data on participant experiences (see ). To the researchers’ knowledge, this is the first time such data on RBG&DT’s Community Greening programme have been collected independently and using mixed methods.

Site selection

Site selection was conducted in tandem with the Community Greening programme coordinator. New community gardens were built in six different suburbs of the Greater Sydney region, which is a culturally, linguistically and socioeconomically diverse area. Three of the six sites were identified with an Index of Relative Socio-Economic Disadvantage being in the lowest 20% across Australia (ABS Citation2018).

Questionnaire: participants

Across the six new sites, 55 community gardeners were successfully recruited as study participants to complete the pre-commencement questionnaire. Of these, only 30 participants also completed the post-test questionnaire. The final sample was reduced to 23 participants across five of the initial six sites after cleaning the data to identify missing data and response sets. Included in the final sample were 14 females and nine males, with an average age of 59 years and median age of 60 years (range 29–83 years). Fifteen participants (53%) reported they were born in Australia; the remainder were born in Fiji, Iran, Poland, New Zealand, Philippines, Chile, Afghanistan and Mauritius. Five participants (22%) reported English was not their first language; one identified as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander. Educational qualifications of participants ranged from university degree (n = 5) to Technical and Further Education (TAFE) certification (n = 8) and high school matriculation (n = 4); six participants did not hold any of these qualifications. All participants lived in social housing, and 47% of participants reported they had a condition that reduced their ability to work.

Prior to participating in the programme, 27% of participants reported they had never gardened, 18% rarely (once a month), 37% often (once a week) and 18% a lot (every day). At the post-test questionnaire, participants reported the frequency of attendance at the programme as rarely (9%), sometimes (once a month, 26%), regularly (once a week, 26%), often (2–3 times a week, 17%) and a lot (almost every day, 22%).

Questionnaire: procedures and measures

The researchers constructed pre- and post-test questionnaires to study participant personal psychological wellbeing and community connection over time. Researchers visited programme locations on two occasions and circulated hard copies of pre- and post-test questionnaires to the participants, inviting them to answer independently. Researchers provided clarification or assistance if required; at times, language interpreters assisted some participants. Key data collected included participants’ motivations to join and continue to attend the programme; their activities such as participation in education, employment and skill development; and health behaviours such as smoking, healthy eating and exercise. Additionally, both pre- and post-test questionnaires included the following two measures:

The Sense of Community Index 2 (Chavis, Lee, and Acosta Citation2008): a quantitative measure of sense of community on a 4-point Likert scale containing 24 items which tally to form a maximum total score of 96. The index comprises elements of membership, influence, meeting needs and a shared emotional connection, where all subscales consist of six items with a maximum score of 24.

The Personal Wellbeing Index (International Wellbeing Group Citation2013): a validated scale using an 11-point (0 = no satisfaction at all to 10 = completely satisfied) Likert response for seven broad domains. A person’s satisfaction is measured across (1) standard of living, (2) health, (3) what you are achieving in life, (4) personal relationships, (5) how safe you feel, (6) feeling part of your community and (7) future security.

Questionnaire: analysis

Demographic data were analysed with descriptive statistics using SPSS. To determine if there were differences on the Sense of Community Index, pre- and post-test scores were analysed with a paired sample t test. The sample constituted a small sample size where the variance of the population was unknown; thus, the t test was deemed appropriate (Wilcox Citation2010). Scores on the Personal Wellbeing Index violated the assumption of normality, and therefore, differences between pre- and post-test scores were tested using the non-parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Focus group: participants

Focus group interviews were held at all six garden sites six to seven months after the construction of garden beds. Community gardeners present at the sites and those who provided consent to complete the focus group were selected as participants. A total of 42 community gardeners were focus group participants (26 female and 16 male). Thirty of them also completed the pre- and post-test questionnaires. The other 12 participants became involved with the programme after garden beds were constructed. An overview of the focus group interviews and participant numbers is provided in .

Table 2. Overview of focus group interview participant numbers.

Focus group: procedures and measures

The focus group interviews consisted of open-ended questions designed to elicit responses and discussion on the impact of the community gardens. The research team developed a semi-structured interview guide to explore participants’ motivations, feelings, perceived benefits, areas of learning, views of the community and suggestions in relation to their participation in the Community Greening programme. The focus groups were conducted on the same date when the post-test questionnaire was administered. The average length of the focus group interviews was 50 min with a range of 34–70 min. At times, language interpreters assisted during the focus group discussion.

Focus group: analysis

Focus group transcripts were managed and analysed with the use of NVivo software. Guided by the constant comparative method (Glaser and Strauss Citation1967; Strauss and Corbin Citation1998), categories were developed based on similarities and differences of ideas within the data, identifying common themes (Creswell Citation2018).

Results

Pre- and post-test questionnaires

Personal wellbeing

The Personal Wellbeing Index (International Wellbeing Group Citation2013) was found to have good reliability for the pre-test scores, producing a Cronbach’s alpha of .892. Participants’ pre-test average scores on all domains fell more than two standard deviations below the mean score for the Australian population, as per the International Wellbeing Group (Citation2013). Means and standard deviations for pre-test and post-test scores are presented in .

Table 3. Mean and standard deviations for pre-test and post-test personal wellbeing index scores for questionnaire participants.

The Wilcoxon test was statistically significant (Z = −1.95, p = .05) for only one domain – satisfaction with health. This result indicated participants reported being less satisfied with their health at post-test compared to pre-test. Although this may be concerning, a closer analysis revealed the age of the participants was an influencing factor in how participants reported changes in their health. Eleven participants reported reduced satisfaction with health (M = 64 years), seven reported no change (M = 59 years) and five reported improved satisfaction with health (M = 52 years).

Sense of community

The Sense of Community Index 2 (Chavis, Lee, and Acosta Citation2008) was found to have good reliability, with all Cronbach’s alphas for subscales above .70. The paired sample t test showed there was a statistically significant increase in the shared emotional connection score and total score, with a .47 and 6.14 point increase, respectively (see ). No other significant differences from pre-test to post-test were found. Results indicated that, over the period from pre-test to post-test, participants reported a significantly increased sense of emotional connection with the community.

Table 4. Paired sample t test of pre- and post-test scores on sense of community index for questionnaire participants.

Focus groups

The semi-structured focus group interviews held at each garden site provided a greater understanding of participants’ self-perceptions of changes in themselves since taking part in the programme. Within-group sharing allowed participants to reflect on detailed accounts of their day-to-day engagement and how the holistic gardening environment, process and activity impacted them.

The participants identified common best features of the community gardening environment as (1) the process of growing fresh produce from start to finish, (2) the aesthetic appeal of the garden beds, (3) the accessibility and ease of working with a raised garden bed, (4) attracting wildlife and (5) increased social interaction. In addition to sharing on health and psychological wellbeing, they also noted the goodness of growing organic food with only natural fertilisers. The following thematic categories illuminate specific participant perceptions and experiences related to the impactful role of gardening in raising their health, psychological wellbeing and community life.

Environment supporting increased physical activity

Participants shared about taking part in a number of physical activities, including watering, planting, weeding and general upkeep of the garden and grounds. Some expressed an appreciation for being outdoors. Older adults and those experiencing mobility challenges discussed how the gardening environment served as a safe place as an extension of some of their mobility and fall-prevention exercises. While some residents reported they had physical limitations with regard to bending and building the gardens, none indicated any dissatisfaction with or negative effects of being outdoors in the garden. Some said physical activity types suited a wide range of age groups which they found to be enjoyable.

“You feel better. Your health is better because you’re doing activity”.

“Since we’ve been in this community garden, we’re more active than we were before, before we moved here”.

“Gardening is exercise all together, and breathing in fresh air is also good, instead of sitting at home”.

“It gets me out of house not thinking about health problems for couple hours and to socialise and to learn proper way”.

“I’m out of the house in the sun and exercising”.

Environment reducing anxiety and stress

Although older adults talked more about physical activity and health, participants also commonly expressed perceived changes in their mental health conditions. For instance, one participant felt the garden environment assisted in providing a “neutral” topic for discussion and safe space for interacting with others. Many of them referred to an increased awareness of reduced anxiety and depression levels.

“From the mental health point of view, the fact that you can switch off your negativity or whatever it is your problem, gives you what I call safe time. It stops the anger, it stops the anxiety, it stops the worry. You sort of shut yourself off to concentrate on a positive and that’s what it does for me. It brings a positive aspect to what could be a very spiralling downward trend”.

“No depression; no anxiety disorder when I’m doing the gardening. It’s just, you’re in your own little zone. Especially when people are walking past and going ‘It’s looking good’ that makes you feel like you’ve contributed, not only just to this block, but to the whole street”.

“It’s meditational. And the trees and plants and herbs don’t swear at you”.

There were no reports of increased stress or anxiety as a result of participation in the garden. In addition to feeling less anxious and more confident in interacting with other people, the participants commonly shared they felt relaxed, calm, happy and joyful as they witnessed the growth phases of plants and vegetables.

“It’s sort of a calming atmosphere. It’s sort of a stress-free environment sort of thing. You know, it's like going for a stroll in the park or something like that”.

“I noticed the change in me in how I handle difficult situations. I’m a lot calmer in the way of dealing with it and less stressful on me. So, yeah, I find I’m a lot calmer within myself now in dealing with difficult situations. It doesn't bother me as much as it used to, so that's a big change for me”.

Environment encouraging eating fresh food

The garden environment facilitated a sense of pride in growing and the convenience of harvesting varieties of fresh vegetables directly from the garden beds. Some participants reported eating more vegetables or trying different types of vegetables. Below is an example of one participant’s perception on how gardening improved her eating habits and initiated positive changes in her life.

“For me, I suffer with a lot of health problems, and a lot of times I’ve been sitting at home, been depressed and not been happy about my illness and since I’ve become more involved with the garden, it helped me to not worry about my health so much like I used to and it actually improved my eating habit. I’m eating a lot more and a lot healthier. Before I didn’t have much of an appetite, so that improved tremendously. … so it’s changed my life positively. I don’t have time to feel sorry for myself anymore, which is good. It’s been very positive for me”.

Gardening facilitating social interactions

A handful of participants said the garden environment had a special identity as a meaningful place for bonding. The newly formed friendships facilitated stronger social relationships. Participants came to plan times to garden together or would stop for conversations if they were passing by elsewhere. They felt the garden promoted such socialising behaviour. One participant put it this way:

“I’d say if you came to the garden, there’s always someone there to meet when you get to the garden. Even if you go by yourself, there’s always someone else walking or walking nearby”.

One participant viewed the environment as “common ground” that could help “break the ice” with other community members, even with small gestures such as saying good morning. Participants considered the garden as an entry point to creating positive relationships. There were comments from three of the sites where participants had minor complaints about the intermittent inequity of work effort in the garden or indicated some tensions in allocating some of the garden tasks but indicated that they were managing these “normal” elements of social interaction. Indeed, participants perceived community and social connection as highly valuable. As social housing residents, most had maintained very low interaction amongst themselves despite a high density of houses. It was commonplace for some residents to “just stay inside their units”, and as one participant stated, “without a garden, you know, it would be just taking out the bins and checking the letterbox. But this gives you a reason to get together and spend a little bit of quality time”. Some acknowledged the importance of the garden being there for everyone – even those who did not or could not work in it. The garden allowed for positive exchanges of different languages which could have been a potential obstacle elsewhere to relationship building. Considering language as an enabling factor, participants found ways to negotiate language barriers. One participant stated, “People communicate non-verbally much more than they did before. A lot of people. Before it was difficult to form a cohesive group. The gardens managed to begin to achieve that, and we can see a path forward”. Even learning each other’s names and interests was viewed by participants as a valuable change.

“When you know someone by their first name and what’s interesting to them, that’s the basis for understanding each other better. And having people here together because we’ve got people gardening, that’s already shown me what the gardening is doing. It’s bringing people together”.

Environment of enjoyment and achievement

The gardens were instrumental in stimulating participants to perceive changes within. As a nature-based learning environment, the garden elicited a sense of enjoyment and achievement in participants. When asked to describe their feelings, they shared that they felt relaxed, calm, proud, happy, satisfied and joyful. The feelings of gratification and delight were attributed to a number of factors, including social interactions arising from gardening, as well as gardening itself and witnessing the growth of the plants. For example, one participant shared the feeling of joy that emerged as a result of hard work in the garden.

“Going outside gives me not only physical exercise, but it provides a certain amount of joy in that you’re seeing the benefit of your hard work coming through in healthy plants, whether it’s vegetables or a conifer, you’re seeing it grow and you’re seeing the benefit, and also the benefit of people’s perceptions has changed, especially neighbours”.

Similarly, participants expressed feelings of satisfaction from watching flowers bloom or produce, such as tomatoes growing over time. Some participants associated these feelings of satisfaction as a source of enjoyment, accomplishment and psychological wellbeing.

“Whole idea is when you sort of grow something you take the pleasure of watching the plants grow. You know, it gives you some pleasure”.

“I know how much fun I get out of it and it’s working well, but I enjoy seeing something, I’m achieving something, and I want others to see that if you put that little effort in you’ve got a plant and you can take home a tomato or you can take home a lettuce and enjoy it and eat it and have the fun from having it. It’s an enjoyment from inside”.

Gardens facilitated an interconnection between participants’ new knowledge of gardening and other life skills. For example, participants shared with each other different ways of cooking vegetables, about recycling in their community, learning from their mistakes and building on previous knowledge. Some participants were completely new to gardening, whilst others had varying levels of experience. At one site, gardeners became concerned about care of the adjacent small forest area, recognising that some of the flowering plants were diminishing and in need of protection to support the bee population. Overall, most participants expressed appreciation for what they had learned in the programme and felt they had experienced benefits to their personal and community life.

Discussion

The findings from this study of six new community gardens developed by the Community Greening programme highlight the potential of these sites for generating psychosocial learning, enhanced personal psychological wellbeing, and community or social connections in underserved communities (Booth et al. Citation2018; Cabral et al. Citation2017; Christensen Citation2017). Employing mixed methods, the researchers examined participant responses via pre- and post-test questionnaires and focus groups. Participants reported various self-perceived benefits for their health and psychological wellbeing status and an appreciation for increased social cohesion.

Participants’ self-perceived intrapersonal outcomes

The participants’ responses revealed intrapersonal outcomes, such as increased physical activity, a greater appreciation for the outdoors and the benefits associated with growing and eating fresh vegetables, including a sense of enjoyment and achievement. These findings reinforce results from other studies, including Cumbers et al. (Citation2018), Hake (Citation2017), Lanier, Schumacher, and Calvert (Citation2015) and Spilková (Citation2017). In accordance with de Bell et al. (Citation2020), our participants described the gardening experience as calming and meditational. In certain instances, community members found gardening reduced experiences of anxiety and stress. Gardening also served as an opportunity to socialise and interact with neighbours and become part of something bigger, as articulated by Kingsley, Foenander, and Bailey (Citation2019). Additionally, participants shared a motivation to learn, to seek new knowledge about gardening and to develop life skills associated with community gardening. Participant perceptions highlighted the direct and indirect prospects that gardening processes elicited in their everyday lives, which similar studies have revealed (see Kingsley et al. Citation2021; Saldivar-Tanaka and Krasny Citation2004).

Responses to the Personal Wellbeing Index questionnaire revealed an interesting pattern of perceptions about satisfaction with health as it related to the age of participants. Although most responses of elderly participants (64 years of mean age) showed less satisfaction with health at post-test, it may imply that gardening processes facilitated better self-awareness of health limitations rather than improving health satisfaction over just six to seven months. Participants reported noticeable changes in their attitude towards health behaviours, such as eating fresh food, learning different culinary practices, physical activity, growing edible gardens and making a concerted effort to engage with their community members. These variations and transformations in participants’ attitudes and behaviours echo previous research findings (e.g. Guitart, Pickering, and Byrne Citation2014; Kingsley et al. Citation2021; Lee and Maheswaran Citation2011; Malberg Dyg, Christensen, and Peterson Citation2020). The younger group of participants however, reported an increase in satisfaction with their health.

Participants’ self-perceived interpersonal and community outcomes

Identified interpersonal outcomes included social connection generated through engaging in shared activities, a sense of community pride and ideas and motivation to continue to grow the garden and develop the community. Participants viewed the gardens as beneficial, but they also served as a catalyst towards cultivating social capital and a stronger sense of community. This feature echoes earlier research by Soga et al. (Citation2017) and Truong et al. (Citation2018).

Some described the garden as a cultural sharing space whereby relationships were formed by helping each other regardless of differences in culture and language. These inclusive acts of shared reciprocity become a vehicle for social justice found in many community gardens previously researched (e.g. Draper and Freedman Citation2010; Woolrych and Sixsmith Citation2013).

The pre- and post-test questionnaire results demonstrated a significant increase in participants’ shared emotional connections. They reported finding joy and happiness in social interactions on site; regular interactions resulted in forming and maintaining friendships in an environment that they felt to be safe, calming and relaxing which are significant for vulnerable communities (Kingsley, Foenander, and Bailey Citation2019; Lapina Citation2017). Participants felt accepted and respected as lifelong learners in a safe and stimulating garden environment. The gardens themselves were living environments serving as a catalyst towards promoting social capital and better life opportunities, and the outcomes represented in the findings were consistent across all six sites. This implies community gardens in poor neighbourhoods as agents of social change and capacity building.

Researchers have not only reported the positive impacts of community gardens’ physical, social and psychological spaces as effective learning environments, but also acknowledged the role of community gardening programmes in creating opportunities for vulnerable populations towards better health, psychological wellbeing and social life (Malberg Dyg, Christensen, and Peterson Citation2020). Woolrych and Sixsmith (Citation2013) echo these sentiments, stating that community gardens offer an incubator for wellbeing to individuals who may be disengaged or marginalised, thereby contributing to social justice. Our involvement with less privileged participants in this study highlights the social justice implications and contributes to the knowledge related to the impact of community gardens in an underresearched population group.

Limitations, implications and recommendations for future research

Although the research team adopted a mixed-methods study design to yield rich primary data on participant perceptions, the absence of a control group reduced the ability to attribute reported changes from pre- to post-test explicitly to the Community Greening programme. Obtaining a control group from a social housing context was less feasible in the study period, therefore resulting in a less rigorous design. Future research designs that adopt a quasi-experimental or randomised control trial are needed to verify the impact of community gardening on individuals and communities. Future studies could incorporate qualitative interviews with specific participants to better understand changes in pre- and post-test measures at the individual level.

The large difference in the study participants’ age groups might have possibly resulted in responses typical to respective age categories. Future studies could specifically tailor the gardening environment to suit different age categories for individual results associated with training, skill development and employment. The expected outcomes need to be developmentally appropriate to different age groups and factors of health, psychological wellbeing, education and employment. The short length of the study period also limited the longer term impact assessment.

As the research team targeted six new Community Greening sites in this study, we can conclude that over the evolution of the programme, participants did get to know one another from their shared lived experiences in the garden. This could lead to bias as reported in the focus group data.

The research implications call for local and national governments to form new policies or amend existing policies related to health and psychological wellbeing, social housing and land management. This study advances the research methodology and knowledge of this target group as the voices of vulnerable populations who were previously invisible or overlooked (Malberg Dyg, Christensen, and Peterson Citation2020) have now been privileged. The participants’ perceptions showed changes in attitude and subsequent improvements in personal psychological wellbeing and in connection to community life. Designing garden environments with affordances and a person-centred approach might have greater individual impact across all age groups. If community gardening programmes achieve such outcomes, they may encourage social and nature-inspired prescriptions for psychological wellbeing. This may in turn reduce overdependency on health services, implying economic benefits to governments.

Designing community garden environments uniquely across different sites targeting diverse communities and age groups could sustain the Community Greening programme in reaching out to more communities. Aspects such as developing self-confidence, financial literacy, creative writing, art forms and music on gardening themes could be useful in future to study the impact of Community Greening programmes. The overall findings from the study provide important feedback for strategic planning and sustaining urban community gardens in neighbourhoods for vulnerable communities to thrive. While this study focused specifically on community gardens in social housing settings, the authors recognise there is a broader body of literature pertaining to community gardens in a range of contexts, including allotments, school gardens, therapeutic gardens and vertical gardens, amongst others. Similarly, there is a growing body of research on the benefits of gardening for specific populations.

The findings from this study are encouraging and highlight the need for similar community gardening programmes, particularly with underserved and vulnerable communities. Further research with rigorous design is essential to investigate if participation in community gardening results in shifts related to sense of community, health and wellbeing, skill acquisition and social participation. Future research may involve an efficacy evaluation which utilises a larger sample size, a control group, specific programme goals tailored for specific participant groups and measures of programme fidelity. Longitudinal studies that examine participants’ experiences and self-perceived benefits over sustained time is also needed. Research that showcases these initiatives and contributes to the growing evidence base will help to inform the development of future programmes and policies to support community greening and engagement.

Conclusion

Our study’s key focus was to broaden the research by highlighting the voices and perceptions of participants from vulnerable groups about the benefits of community gardening. The findings convey the role of community gardens in positively influencing participants to experience heightened emotional connection to their community and address entrenched social inequality within society. As such, these local environments act as an incubator for self-perceptions of individual wellbeing and connection. Participants in the focus groups discussed attitudes and behaviours that improved their health and psychological wellbeing as a result of their engagement with community gardens. Satisfaction with health following participation in community gardens appears to be associated with a participant’s age, and this finding warrants further attention. Most importantly, community gardens offer physical and social wellbeing to individuals who may be considered disengaged, marginalised or disenfranchised and correspondingly contribute to sustaining issues surrounding social justice within these populations. Finally, more robust methodology and longer term research studies may yield richer insights into the nuanced findings on the experiences of vulnerable populations participating in community gardening programmes.

Acknowledgements

The Western Sydney University Human Research Ethics Committee granted ethical approval to conduct the study. This study was made possible by a collaboration between Western Sydney University, the Royal Botanic Garden and Domain Trust (RBG&DT) in Sydney, Australia, and the Department of Family and Community Services (DFACS), New South Wales (NSW) now known as Department of Communities and Justice (DCJ) NSW.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics). 2018. “Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA) 2016.” Accessed January 16, 2020. http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/Lookup/by%20Subject/2033.0.55.001~2016~Main %20Features∼SOCIOECONOMIC%20INDEXES%20FOR%20AREAS%20(SEIFA)%2020 16∼1.

- Audate, P. P., M. A. Fernandez, G. Cloutier, and A. Lebel. 2019. “Scoping Review of the Impacts of Urban Agriculture on the Determinants of Health.” BMC Public Health 19 (1): 1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6885-z

- Bleasdale, T., C. Crouch, and S. L. Harlan. 2011. “Community Gardening in Disadvantaged Neighborhoods in Phoenix, Arizona: Aligning Programs With Perceptions.” Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development 1 (3): 99–114.

- Booth, J., D. Chapman, M. Ohmer, and K. Wei. 2018. “Examining the Relationship Between Level of Participation in Community Gardens and Their Multiple Functions.” Journal of Community Practice 26 (1): 5–22. doi:10.1080/10705422.2017.1413024.

- Bowker, R., and P. Tearle. 2007. “Gardening as a Learning Environment: A Study of Children’s Perceptions and Understanding of School Gardens as Part of an International Project.” Learning Environments Research 10 (2): 83–100. doi: 10.1007/s10984-007-9025-0

- Cabral, I., S. Costa, U. Weiland, and A. Bonn. 2017. “Urban Gardens as Multifunctional Nature-Based Solutions for Societal Goals in a Changing Climate.” In Nature-Based Solutions to Climate Change Adaptation in Urban Areas: Linkages Between Science, Policy and Practice, edited by N. Kabisch, H. Korn, J. Stadler, and A. Bonn, 237–253. Springer Open. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-56091-5_14.

- Carney, P., A. Hamada, J. Rdesinski, L. Sprager, R. Nichols, L. Liu, and B. Shannon. 2012. “Impact of a Community Gardening Project on Vegetable Intake, Food Security and Family Relationships: A Community-Based Participatory Research Study.” Journal of Community Health 37 (4): 874–881. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9522-z

- Chavis, D. M., K. S. Lee, and J. D. Acosta. 2008. “The Sense of Community (SCI) Revised: The Reliability and Validity of the SCI-2.” Paper presented at the 2nd International Community Psychology Conference, Lisboa, Portugal.

- Christensen, S. 2017. “Seeding Social Capital? Urban Community Gardening and Social Capital.” Civil Engineering and Architecture 5 (3): 104–123. doi: 10.13189/cea.2017.050305

- Creswell, J. 2018. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. 5th ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publishing.

- Cumbers, A., D. Shaw, J. Crossan, and R. McMaster. 2018. “The Work of Community Gardens: Reclaiming Place for Community in the City.” Work, Employment and Society 32 (1): 133–149. doi: 10.1177/0950017017695042

- de Bell, S., M. White, A. Griffiths, A. Darlow, T. Taylor, B. Wheeler, and R. & Lovell. 2020. “Spending Time in the Garden is Positively Associated With Health and Wellbeing: Results from a National Survey in England.” Landscape and Urban Planning 200: 103836. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2020.103836

- Desmond, D., J. Grieshop, and A. Subramaniam. 2004. Revisiting Garden-Based Learning in Basic Education. Food and Agriculture Organization, International Institute of the United Nations. Rome: FAO.

- Djokić, V., J. Trajković, D. Furundžić, V. Krstić, and D. Stojiljković. 2018. “Urban Garden as Lived Space: Informal Gardening Practices and Dwelling Culture in Socialist and Post-Socialist Belgrade.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 30: 247–259. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2017.05.014

- Draper, C., and D. Freedman. 2010. “Review and Analysis of the Benefits, Purposes and Motivations Associated With Community Gardening in the United States.” Journal of Community Practice 18: 458–492. doi: 10.1080/10705422.2010.519682

- Egli, V., M. Oliver, and E. S. Tautolo. 2016. “The Development of a Model of Community Garden Benefits to Wellbeing.” Preventive Medicine Reports 3: 348–352. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2016.04.005

- Firth, C., D. Maye, and D. Pearson. 2011. “Developing “Community” in Community Gardens.” Local Environment 16 (6): 555–568. doi:10.1080/13549839.2011.586025.

- Glaser, B., and A. L. Strauss. 1967. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Chicago, IL: Aldine Publishing Company.

- Glover, T. 2004. “Social Capital in the Lived Experiences of Community Gardeners.” Leisure Sciences 26 (2): 143–162. doi: 10.1080/01490400490432064

- Glover, T., K. Shinew, and D. Parry. 2005. “Association, Sociability, and Civic Culture: The Democratic Effect of Community Gardening.” Leisure Sciences 27 (1): 75–92. doi: 10.1080/01490400590886060

- Guitart, D. A., C. M. Pickering, and J. A. Byrne. 2014. “Color Me Healthy: Food Diversity in School Community Gardens in Two Rapidly Urbanising Australian Cities.” Health and Place 26: 110–117. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2013.12.014.

- Hake, B. 2017. “Gardens as Learning Spaces: Intergenerational Learning in Urban Food Gardens.” Journal of Intergenerational Relationships 15 (1): 26–38. doi:10.1080/15350770.2017.1260369.

- Harris, N., F. R. Minnis, and S. Somersat. 2014. “Refugees Connecting With a New Country Through Community Food Gardening.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 11: 9202–9216. doi:10.3390/ijerph1109092022.

- Hartwig, K., and M. Mason. 2016. “Community Gardens for Refugee and Immigrant Communities as a Means of Health Promotion.” Journal of Community Health 41 (6): 1153–1159. doi: 10.1007/s10900-016-0195-5

- Hoffimann, E., H. Barros, and A. I. Ribeiro. 2017. “Socioeconomic Inequalities in Green Space Quality and Accessibility-Evidence from a Southern European City.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 14 (916): 1–16. doi:10.3390/ijerph14080916.

- International Wellbeing Group. 2013. Personal Wellbeing Index. 5th ed. Melbourne: Australian Centre on Quality of Life, Deakin University.

- Kingsley, J., M. Egerer, S. Nuttman, L. Keniger, P. Pettitt, N. Frantzeskaki, T. Gray, et al. 2021. “Urban Agriculture as a Nature-Based Solution to Address Socio-Ecological Challenges in Australian Cities.” Urban Forestry Urban Greening. doi:10.1016/j.ufug.2021.127059.

- Kingsley, J., E. Foenander, and A. Bailey. 2019. ““You Feel Like You’re Part of Something Bigger”: Exploring Motivations for Community Garden Participation in Melbourne, Australia.” BMC Public Health 19: 745. doi:10.1186/s12889-019-7108-3.

- Kingsley, J. Y., and M. Townsend. 2006. ““Dig in” to Social Capital: Community Gardens as Mechanisms for Growing Urban Social Connectedness.” Urban Policy and Research 24 (4): 525–537. doi: 10.1080/08111140601035200

- Kingsley, J., M. Townsend, and C. Henderson-Wilson. 2009. “Cultivating Health and Wellbeing: Members’ Perceptions of the Health Benefits of a Port Melbourne Community Garden.” Leisure Studies 28: 207–219. doi: 10.1080/02614360902769894

- Krasny, M., and K. Tidball. 2009. “Community Gardens as Contexts for Science, Stewardship, and Civic Action Learning.” Cities and the Environment 2 (1): 1–18. doi: 10.15365/cate.2182009

- Lanier, J., J. Schumacher, and K. Calvert. 2015. “Cultivating Community Collaboration and Community Health Through Community Gardens.” Journal of Community Practice 23 (3-4): 492–507. doi: 10.1080/10705422.2015.1096316

- Lapina, L. 2017. “‘Cultivating Integration’? Migrant Space-Making in Urban Gardens.” Journal of Intercultural Studies 38 (6): 621–636. doi:10.1080/07256868.2017.1386630.

- Lee, A., and R. Maheswaran. 2011. “The Health Benefits of Urban Green Spaces: A Review of the Evidence.” Journal of Public Health 33 (2): 212–222. doi:10.1093/pubmed/fdq068.

- Malberg Dyg, P., S. Christensen, and C. J. Peterson. 2020. “Community Gardens and Wellbeing Amongst Vulnerable Populations: A Thematic Review.” Health Promotion International 35 (4): 790–803. doi: 10.1093/heapro/daz067

- Martin, P., J. P. Consalès, P. Scheromm, P. Marchand, F. Ghestem, and N. Darmon. 2017. “Community Gardening in Poor Neighborhoods in France: A Way to Re-Think Food Practices?” Appetite 116: 589–598. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2017.05.023

- Miller, W. M. 2015. “UK Allotments and Urban Food Initiatives: (Limited?) Potential for Reducing Inequalities.” Local Environment 20 (10): 1194–1214. doi: 10.1080/13549839.2015.1035239

- Ochoa, J., E. Sanyé-Mengual, K. Specht, J. A. Fernández, S. Bañón, F. Orsini, F. Magrefi, et al. 2019. “Sustainable Community Gardens Require Social Engagement and Training: A Users’ Needs Analysis in Europe.” Sustainability 11 (3978): 1–16.

- Ohmer, M., P. Meadowcroft, K. Freed, and E. Lewis. 2009. “Community Gardening and Community Development: Individual, Social and Community Benefits of a Community Conservation Program.” Journal of Community Practice 17 (4): 377–399. doi: 10.1080/10705420903299961

- Royal Botanic Garden and Domain Trust. 2020. “Community Greening Annual Report.” Sydney, December, 2020.

- Royal Botanic Garden and Domain Trust, Sydney. n.d. “Community Greening.” Accessed November 10, 2019. https://www.rbgsyd.nsw.gov.au/learn/community-greening.

- Saldivar-Tanaka, L., and M. Krasny. 2004. “Culturing Community Development, Neighborhood Open Space, and Civic Agriculture: The Case of Latino Community Gardens in New York City.” Agriculture and Human Values 21 (4): 399–412. doi: 10.1023/B:AHUM.0000047207.57128.a5

- Soga, M., D. T. Cox, Y. Yamaura, K. J. Gaston, K. Kurisu, and K. Hanaki. 2017. “Health Benefits of Urban Allotment Gardening: Improved Physical and Psychological Well-Being and Social Integration.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 14 (1): 71. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14010071

- Spilková, J. 2017. “Producing Space, Cultivating Community: The Story of Prague’s New Community Gardens.” Agriculture and Human Values 34 (4): 887–897. doi: 10.1007/s10460-017-9782-z

- Strauss, A., and J. M. Corbin. 1998. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Truong, S., T. Gray, D. Tracey, and K. Ward. 2018. The Impact of Royal Botanic Gardens’Community Greening Program on Perceived Health, Wellbeing, and Social Benefits in Social Housing Communities in NSW: Research Report. Sydney: Centre for Educational Research, Western Sydney University.

- Truong, S., T. Gray, and K. Ward. 2016. “"Sowing and Growing" Life Skills Through Garden-Based Learning to Reengage Disengaged Youth.” LEARNing Landscapes 10 (1): 361–385. doi: 10.36510/learnland.v10i1.738

- Wilcox, R. R. 2010. “Hypothesis Testing and Small Sample Sizes.” In Fundamentals of Modern Statistical Methods. New York, NY: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-5525-8_5.

- Woolrych, R., and J. Sixsmith. 2013. “Placing Well-Being and Participation Within Processes of Urban Regeneration.” International Journal of Public Sector Management 26 (3): 216–231. doi: 10.1108/IJPSM-09-2011-0119