ABSTRACT

This paper reports on tensions between decarbonisation and energy poverty priorities in Great Britain’s liberalised electricity markets. Switching electricity suppliers in this market can result in significant benefits for those on bad deals. Further benefits are determined by the regulator. However, many of the energy poor lack the capabilities to switch and access these benefits. Community organisations play an important role in providing such access through remedial action. Using the capabilities approach, this paper combines quantitative and qualitative organisational data analysis at a community level to reveal an increasing share of the population who could benefit from switching and who agree to switching. At the same time, eligibility for one-off discounts on electricity bills to support the energy poor has increased sharply in recent years. This data points towards climate mitigation policies and market structures which benefit wealthier groups at the expense of more deprived groups who lack capabilities. At the micro scale, data access and intermediation at various levels and scales can help support more targeted interventions that facilitate well-being and enhanced capabilities. At the macro level, liberalised retail electricity markets need to be accommodated by safety nets and supportive institutional arrangements to avoid competitive pressures translating into complexity and opacity for consumers. Failure to equitably address capability conflicts, also framed as energy justice tensions and trade-offs, risks reinforcing and creating new injustices.

1. Introduction

With its history of poor housing, energy poverty has long been recognised as an issue in the UK, where it is commonly referred to as fuel poverty (Boardman Citation1991; Bouzarovski Citation2018). This has resulted in cumulative experience in community engagement, social policies, and practical methodologies to address it. The issue of energy poverty is also increasingly recognised as a major public health problem (Public Health England Citation2017), with costs to the National Health Service (NHS) of approximately £1.36 billion per year, not including costs of social care or informal care (Grey et al. Citation2017).

Despite years of engagement and developing understandings of the causes and effects of energy poverty, it remains a persistent problem (Middlemiss Citation2017; Martiskainen et al. Citation2020). The UK also lacks both a national system or infrastructure and a national energy poverty registry to help the vulnerable and track progress (Mallaburn and Eyre Citation2014; CLF Citation2016). According to the Committee on Fuel Poverty (Citation2021, 8), “the addresses of [energy poor] households are unknown and hence it is difficult to target and assist them”. To complicate matters, measurements and definitions of energy poverty have changed and vary in different parts of the UK (England, Wales, Scotland, Northern Ireland) as it is considered a devolved policy area (Hinson and Bolton Citation2020).

Engaging the energy poor in Great Britain (England, Wales, Scotland) is further complicated by the structure of the British retail electricity market. Although it represents the key link between the electricity system and end users, the British retail electricity market is characterised by a lack of consumer engagement. Consumer choice through individual switching of suppliers, which is encouraged as remedial action to counter high electricity costs, is least effective for the most disengaged consumers who are often those in energy poverty (CMA Citation2016; BEIS Citation2018; Poudineh Citation2019).

Community organisations who try to address this injustice (and market failure) through engagement and outreach activities are burdened with a support structure based on energy supply companies with conflicting interests of profiting from customers on the highest tariffs, while being mandated to address energy poverty. Amidst shifting regulatory requirements, these companies regularly change reporting requirements and targets of their energy poverty alleviation grants. Tariff switching is complicated by an increasing tendency among suppliers to deny switching websites access to their cheapest tariffs. Spiralling inflation starting in 2021 and amplified by Russia’s invasion of the Ukraine saw suppliers go into administration and denying access to all but the most expensive tariffs, thus rendering the market for supplier switching redundant. As a result, community energy poverty alleviation organisations need to constantly change their intermediation strategy to satisfy these requirements and changing market conditions while supporting people through remedial actions on their pathway out of energy poverty (CLF Citation2016).

Overall, successive governments have shown little interest systematically addressing these issues, despite plenty of supportive rhetoric (CLF Citation2016; Poudineh Citation2019). This stands in contrast to electricity supply decarbonisation which is one of Great Britain’s liberalised electricity system’s most significant success stories. Between 2011 and 2016, the UK achieved a 10%/a reduction in the carbon intensity of electricity generation (CCC Citation2019). Despite the success of this electricity decarbonisation transition pathway, a more concerted society-wide effort is therefore required to achieve a just transition to carbon neutrality (Foxon, Hammond, and Pearson Citation2010; CCC Citation2019).

UK-wide government policies in support of the transition to net zero, such as the “Ten Point Plan for a Green Industrial Revolution” (BEIS Citation2020), however, continue to focus predominantly on supply and technologies, instead of demand and people (Nolden, Eyre, and Fawcett Citation2021). Where policies address living arrangements, such as the housing stock, which is among the oldest in the world and one of the main causes of energy poverty, they have a recent history of inadequacy and poor implementation (Rosenow and Eyre Citation2016; Rosenow and Sunderland Citation2021; CCC Citation2022). Only around £0.4bn/a of the £2.55bn/a allocated to improving energy efficiency and assisting householders pay their energy bills is received by the energy poor (Committee on Fuel Poverty Citation2021). The British Energy Security Strategy (BEIS Citation2022) continues this supply focus, with demand side support for households limited to a 5-year VAT suspension on domestic energy efficiency measures such as insulation and heat pumps, which obviously require investment and creditworthiness which many energy poor households lack. In this context the UK government has stated that is welcomes “research on the likely impacts of decarbonisation for households in energy poverty” (BEIS Citation2021, 45).

Using the capabilities approach, this paper seeks to address this research gap by complementing qualitative research carried out between 2003 and 2018 which highlighted the barriers energy poor households face engaging with the retail energy market in the absence of intermediary organisations (Ambrosio Alaba et al. Citation2020). Specifically, this paper analyses data from two organisations engaging in energy poverty alleviation at community level, South East London Community Energy (SELCE) and Energise Sussex Coast (ESC), to shed light on energy poverty alleviation supported by the UK’s liberalised electricity market. Quantitative organisational data provides insights into the demand for the energy poverty alleviation services these organisations provide to households and individuals regarding switching energy suppliers and applying for the Warm Home Discount scheme, a one-off discount paid on electricity bills between October and March. This data also reveals changes in energy poverty over time. Qualitative organisational data consist of case studies which reveal more granular information regarding the nature of energy poverty, the strategies employed by community organisations to alleviate energy poverty under challenging circumstances, and the failures of the underlying liberalised energy market to address these issues.

The data facilitates the analysis of tensions between organisational intermediation to alleviate energy poverty at a community level one the one hand, energy policy prioritising rapid electricity supply decarbonisation at an energy systems level on the other, and a liberalised retail electricity market in between which counts lack of consumer engagement among its biggest weaknesses. This paper is motivated by an interest in the tensions between liberalised energy market structures and the goals of climate change mitigation and energy poverty alleviation.

The specific research questions are:

What role do community organisations play in securing better deals for the energy poor in liberalised electricity markets and how does this impact their capabilities and well-being?

What does their organisational data tell us about the persistency of energy poverty in liberalised electricity markets?

What needs to change to foster a socially just transition to net zero with basic and secondary capabilities ensured?

This paper is structured as follows. Section 2 introduces relevant concepts and literatures. Section 3 describes the methodology and the analytical framework. Section 4 analyses company data from two organisations engaging in community energy poverty alleviation. Section 5 discusses the findings in the context of a liberalised electricity market. Section 6 concludes.

Background

2.1. Energy poverty and Great Britain’s liberalised retail electricity market

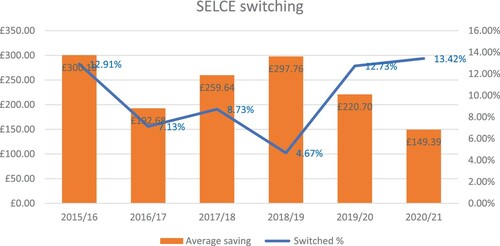

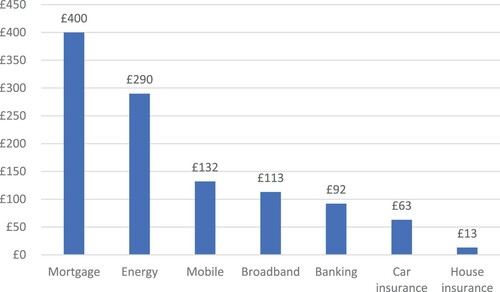

The liberalised structure of the UK’s electricity market has facilitated rapid decarbonisation of electricity supply in recent years (CCC Citation2019). This structure, however, falls short on other priorities. By resembling an “oligarchy” with the “Big Six” supply companies (integrated generators/retailors) manipulating the wholesale price through dealing between themselves and long-term confidential contracts, it falls short of its prioritisation of competition. Better deals that are supposed to result from competition also do not appear to lend themselves to energy poverty alleviation (Thomas Citation2019). The value of switching tariff is evident in the following Figure (; BEIS Citation2018):

Figure 1. Average annual saving from switching for those on poor value deals (BEIS Citation2018, 15).

shows that switching energy supplier ranks second among savings potentials for those on poor value deals, although the gas shortage commencing in autumn 2021 saw energy suppliers removing all options to switch. Contrary to conventional economic thought, however, people are not rationally acting cost optimisers seeking to maximise their profits and minimise their outgoing. This is acknowledged by the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS Citation2018, 15).

It is often those who are the most vulnerable who are least likely to be on good deals and therefore pay the most. For example in the energy market, the consumers least likely to have switched in the past three years are consumers with one or more of the following characteristics: household incomes under £18,000 a year; living in rented social housing; without qualifications; aged 65 and over; with a disability; or on the Priority Services Register

The proportion of consumers who switched suppliers between 2013–2016 stood at 35% among households with incomes above £36k/a compared to only 20% among those with incomes below £18k/a. A similar disparity is observed among those with a degree and those without qualifications (CMA Citation2016). This suggest that the remedial action to address poor value deals are out of reach to many of those living in (energy) poverty, if they are available in the first place. What might appear as easy financial gains by switching supplier, providing average annual savings of £290 (), thus entails switching costs and barriers (Poudineh Citation2019, 11).

More generally, these suppliers routinely place people on the most expensive standard variable tariffs, upon which well over 50% of people remain (57% in 2017), with this amounting to over £1bn in “detriment” per year (£1.4 billion in 2016) (CMA Citation2016). This practice has been going on for over a decade with Ofgem as long ago as 2008 suggesting that “suppliers benefit in total by around £1 billion per annum from premiums … borne disproportionately by vulnerable consumers and those without access to the gas grid” (Ofgem Citation2008, 113).

2.2. Energy poverty alleviation in Great Britain

Furthermore, energy supply companies do not have a good track record of treating their customers fairly and nor does the regulator Ofgem have a good track record of encouraging them to do so either (Bayliss, Mattioli, and Steinberger Citation2020; Thomas Citation2019). The result is that energy poverty alleviation through supplier switching often depends on the expertise available to the energy poor in their local area. In Great Britain, such expertise is often located in community organisations such as charities or community interest companies (CICs) because well over a decade of funding cuts and austerity measures has seen the role of local authorities in addressing energy poverty diminish (Gray and Barford Citation2018).

Such organisations run events such as energy cafes to reach out to the energy poor in the absence of government databases and help reduce switching costs and barriers (CLF Citation2016; Martiskainen, Heiskanen, and Speciale Citation2017). The success of such community organisations is closely linked to their ability to retain staff and ensure continuity, which is turn is dependent on their ability to raise funding (CLF Citation2016).

The main role that such community organisations play include (CLF Citation2016):

Checking bills to assess whether they are higher than average (standard contracts are for one year so this needs to be done on a regular basis) and switching to another supply company if they provide a better deal;

Switching to a supply company which provides a Warm Home Discount (mainly funded through the Energy Company Obligation (ECO) which covers about half the money required);

Providing advice on energy saving behaviours such as reducing heating temperatures and only heating rooms that are in constant use;

Promoting and facilitating home visits (where possible) to install energy efficiency measures such as draught proofing and insulation, and referring to support schemes such as the Energy Company Obligation (ECO); and

(5) Signposting those in debt or in risk of debt, and those with multiple vulnerabilities through local referral networks to debt relief and/or energy advice services.

Community energy poverty alleviation thus encompasses financial approaches (1. and 2.), behavioural approaches (3.), physical approaches (4.) and coping strategies (5.). Although these approaches and strategies revolve around energy, in practice they are more about debt management, tariff switching and behavioural strategies to keep warm than energy per se (Reeves Citation2016). Organisations engaging in energy poverty alleviation often combine such advice with advice on water saving and other utilities where debt issues are linked to liberalised market structures (Bayliss, Mattioli, and Steinberger Citation2020). We therefore combine quantitative data regarding 1. and 2. with qualitative data regarding all five points to reveal both the scope and depth of these organisations’ engagement practices and the consequences of assigning energy poverty alleviation responsibilities to supply companies pursuing profit in liberalised electricity markets.

3. Methodology

3.1. The capabilities approach

To shed light on these engagement practices and the materiality of energy poverty we employ the capabilities approach. Following Walker and Day (Citation2012), energy poverty can be considered an injustice and these organisations seek to address it by increasing capabilities. Energy poverty, according to Walker and Day (Citation2012, 70), “can have impacts on the capability to achieve a range of valued functionings in everyday life”. The capability approach used in this paper contrasts to various other ways of judging and facilitating human development and freedom in a number of ways but at its core, it is about what people are actually able to do and be. This theory posits that a right do or be something, or the focus on the distribution of a resource, fails to ensure both that someone is capable of exercising that right or that the processes and outcomes of resource distribution are just. In contrast, the capability approach focuses on what people are able to do/be and the surrounding social and structural conditions of possibility of this functioning (Smith and Seward Citation2009).

According to Nussbaum (Citation2003), some freedoms hamper others. For instance, the freedom to drive one’s 4 × 4 clearly limits the freedoms of others now and in future generations. Another reason is that some freedoms are more integral to human flourishing, some are just bad and others trivial; for instance, we might say the freedom to vote and participate politically is essential, the freedom for large corporations to make political donations is bad (Meadows Citation1999), and the freedom of choice the market ostensibly delivers is trivial (Nussbaum Citation2003). Within this approach there is the distinction between functioning and a capability with the former the doing/being, such as doing work or good health, while the latter refers to “actual or real opportunities to realise given functionings, whether one chooses to at a particular time of not” (Day, Walker, and Simcock Citation2016, 258; Sen Citation2009).

Some core concepts from this approach have been fruitfully employed in energy justice and energy poverty research and provide the basis for the analysis in this paper. First, as described above, certain freedoms conflict with others and these have been conceived as capability conflicts (Wood and Roelich Citation2019). In energy terms, these conflicts can be framed as the tensions in climate crisis mitigation as fossil fuel enhanced capabilities such as mobility or access to heat based on fossil fuel use are reduced as mitigation policies take effect. Day, Walker, and Simcock (Citation2016) offer another way of thinking about capabilities through secondary capabilities, such as washing clothes or storing and preparing food, and basic capabilities, such as good health or respect. In this way, the basic capability of being in good health is dependent on a whole host of secondary capabilities such as heating or cooling a home, cooking, and cleaning (Day, Walker, and Simcock Citation2016).

In a sense, this secondary and basic distinction can map onto quantitative secondary capabilities, such as accessing information, and more qualitative basic capabilities, such as maintaining relationships (Wood and Roelich Citation2019). Finally, Middlemiss et al. (Citation2019), drawing on Smith and Seward (Citation2009), in a study of energy poverty and how the capability of relating socially mediates the capability to access energy services and support, offers four conditions of possibility for these capabilities that will be used in this paper. These conditions are:

reasons which justify or explain social phenomena, such as austerity justifying cuts to certain local authorities;

resources which include people’s social and material circumstances, such as housing, mobility or social interactions that allow people to achieve capabilities;

roles people play in their society and the associated liabilities or powers of these roles, such as homeowner or tenant;

and collectivities or the social groups people identify with and are identified as, again with associated liabilities and powers, such as disabled people (Middlemiss et al. Citation2019).

This paper employs the capability approach to explore and highlight capability conflicts that arise from Great Britain's energy policy, climate crisis mitigation and their interactions on the energy poor through liberalised electricity markets. In doing so, it suggests ways of avoiding these conflicts and promoting more just outcomes. It also distinguishes between secondary capabilities, in this context accessing information on the services of switching energy supplier and accessing the Warm Home Discount (WHD), and the more abstract basic capabilities of good health and maintaining social relations. Focussing on these two basic capabilities, this paper assesses the impact of community energy organisation’s interactions with victims of energy poverty. Specifically, it examines how these social relations impact the specific capability of being able to access energy and related support with the use of the above concepts of reason, resource, role and collectivity that enable or prevent capabilities.

3.2. Data sources

To shed light onto the tensions and capability conflicts between organisational intermediation to alleviate energy poverty, rapid electricity supply decarbonisation, and a liberalised retail electricity market, this paper analyses organisational community energy poverty alleviation data. It was gathered between 2015 and 2021 by two companies, Energise Sussex Coast (ESC) and South East London Community Energy (SELCE).

The data relates to their community fuel poverty alleviation services through intermediation. Aggregate winterly energy poverty alleviation data (October to March) is provided in pseudonymised excel spreadsheets. However, changing requirements by funders, changing organisational capacity and changing data gathering approaches imply that such yearly data is often inconsistent. Overall, data varies hugely from year to year and between the two organisations. Significant support by the CEOs of both ESC and SELCE was necessary to facilitate interpretation and establish an overview of inputs and outcomes.

Nevertheless, funders’ emphasis on switching suppliers and making savings on energy bills through the one-off energy poverty alleviation payment Warm Home Discount (WHD) throughout the years provides a certain consistency (financial approaches, see section on Energy poverty alleviation in Great Britain above). Information captured less systematically includes figures on those eligible for Energy Company Obligation (ECO) support (physical approaches), Priority Service Registry (financial approaches), Watersure discount (financial approaches relating to water bills) and home visits (coping strategies). Although this data provides a crucial insight into debt alleviation and permanent improvements of building fabric, which have a much greater impact of energy poverty alleviation than supplier switching or WHD applications, it is omitted from quantitative analysis due to data incompletion. Where possible, it is included in the qualitative case study analysis which helps contextualise the quantitative data.

Data gathered on switching supplier and the WHD include: those switched on the day during an advice session, those who agreed to review their bills and consider switching, those eligible for WHD, those who received information on WHD, those who applied for WHD on the day during an advice session. Due to the lack of resources to follow up on advice it is uncertain to what extent advice was acted on and whether those who agreed to review their bills actually switched suppliers. For this paper we therefore provide a comparative analysis of the figures on recorded switches on the day and WHD application on the day which were carried out by representative (employees or volunteers) of both organisations. Data on eligibility gathered by SELCE is used to highlight changing demand for community fuel poverty alleviation services. Case study data gathered by both organisations provides qualitative information regarding the energy advisor, the situation of the client, the action taken and the outcome of this action which enables analysis of energy poverty and alleviation efforts in the context of the capabilities approach. Combining quantitative and qualitative data is essential to paint a compete picture of how energy poverty materialises in liberalised energy markets and what impact these organisations can have in challenging circumstances.

4. Findings

4.1. Geography and clients of the community fuel poverty alleviating organisations

We start by analysing demographic and ethnicity data to indicate the different geographical areas and client basis of the two companies. This increases the robustness of the findings regarding their energy poverty data below.

ESC operates at the intersection of urban and rural areas from its base in St Leonards-on Sea, close to Hastings, UK. 11.5% of households in Hastings are energy poor according to the official definition. The figures for the surrounding areas of Eastbourne, Lewes and Rother are 8.5%, 8% and 10.6% respectively. SELCE operates exclusively in urban environments from its base in Lewisham (London), UK. 12.1% of households in Lewisham are energy poor. The figures for the surrounding areas of Greenwich, Southwark and Bromley where SELCE is active are 11.1%, 9.9% and 8.6%, respectively, (2018 numbers, in BEIS Citation2020).

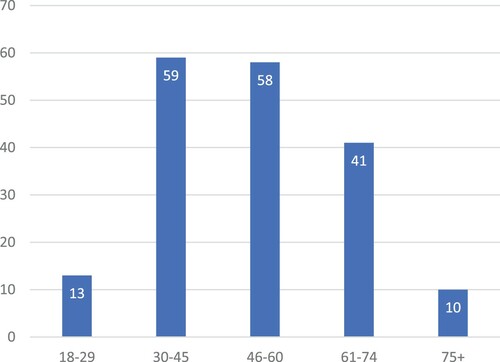

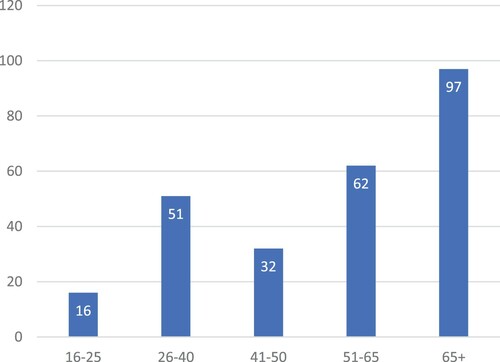

Data on demographics and ethnicity of their clients was gathered unsystematically and inconsistently. Nevertheless, the two best datasets available paint a clear picture ( and ; note the different age ranges).

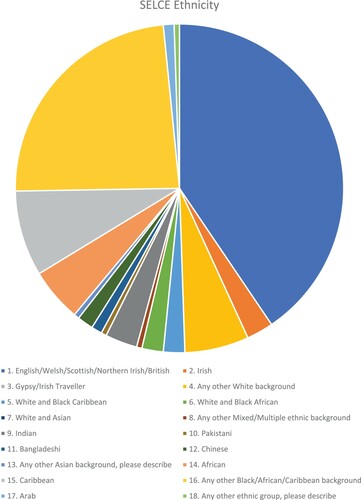

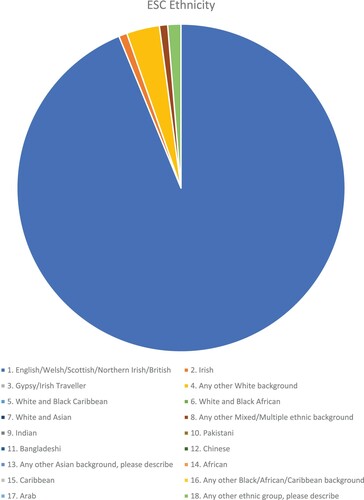

and indicate that SELCE’s customers tend to be younger than ESC customers but this reflects the average age of populations which is 40.5 in Hastings, 43 in Eastbourne, 44 in Lewes 47 and in Rother compared to 33.8 in Southwark, 35.5 in Greenwich, 35.6 in Lewisham and 40 in Bromley (Urbistat Citation2021). Similar discrepancies are also evident in data on ethnicity, which is even less consistent than data on age. The following graphs ( and ) provides a snapshot from the only data available from ESC (831 responses, 215 blanks from 2016) and the most comprehensive data from SELCE (417 responses, 227 blanks from 2018):

Broadly speaking, this data in and reflects overall trends. In Lewisham, for example, 57% of the population (2013 figures) was white while in Hastings 93.8% of the population is white (2011 figures; East Sussex County Council 2011; Lewisham JSNA Citation2021). These figures suggest that both ESC and SELCE broadly succeed in reaching out to their local demographic and ethnic mix.

4.2. Organisational energy poverty alleviation data

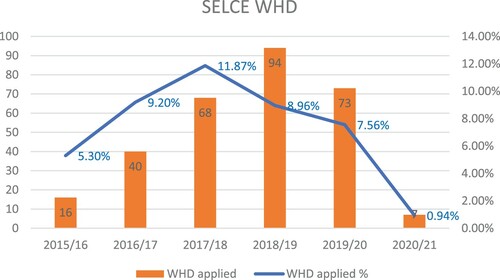

Despite ethnographic and demographic discrepancies among their clients, company data from both ESC and SELCE reveals that their supplier switching efforts have followed broadly similar trends in terms of the percentage of clients they engaged that were switched to a cheaper tariff on the day in a given winter ( and ). In practice, a much larger percentage of clients were given information how to switch, and many no doubt did as follow-up research by Curtis (Citation2019) suggests.

Average savings, on the other hand, follow more variable trends. ESC has recorded constant average savings between £200–250 since 2015 while SELCE savings have fluctuated between £200–300 before plummeting to below £150 in 2020/21. At the same time, both ESC and SELCE representatives report spending more time on advice sessions. Where previously it was possible to find the cheapest deals on price comparison websites, this is no longer the case (as mentioned above). Following the development of automatic switching services, many energy suppliers no longer facilitate access to their cheapest deals to such services and price comparison websites. To find the cheapest deals, several price comparisons websites and company-owned websites now need to be compared to find the cheapest deal, thus requiring increasing resources to realise a supposed benefit of liberalised electricity markets.

This can be seen as both a move by the energy companies to maximise profits through a reduction in the potential of their customer’s capability to access information and cheaper deals. Another issue to consider is that those on prepayment metres and in energy debt of more than £500 are not allowed to switch. This implies that those in more extreme forms of poverty have their secondary capability of switching to a cheaper option overtly removed. This factor could be affecting the numbers above.

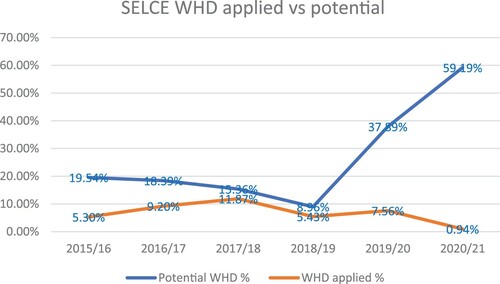

Trends regarding the Warm Home Discount (WHD), a one-off discount on electricity bills to support the energy poor and the second pilar of financial community energy poverty advice supported by funders, are much more variable (see and ). The WHD was introduced in 2011 and scheduled to end on 31 March 2015. Since then, it has been extended twice for five years, from 2015/16 until 2020/2021 and from 2020/21 until 2025/26. Although both ESC and SELCE started their energy poverty alleviation work before 2015/16, both record low levels of WHD applications in 2015/16, both in terms of total numbers and the share of people the engaged.

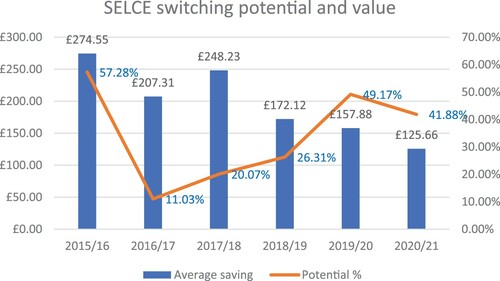

Figure 10. Total percentage of SELCE clients who could benefit from switching and associated savings.

Figure 11. Total percentage of SELCE clients who could benefit from switching and associated savings.

In subsequently years, we can observe demand for WHD applications among ESC’s customers fluctuating between around 6 and 17.5%, although the total number of WHD applications varies significantly according to the total number of customers ESC engaged with in a particular year. In 2020/21 there has been a significant increase in the percentage of clients that were signed up to the WHD on the day ().

Demand for WHDs among SELCE’s customers fluctuated slightly more between 2015/16 and 2019/20 compared to ESC but the most significant change occurred from 2018/19 onwards (). While ESC saw demand for WHD applications nearly double between 2019/20 and 2020/21, SELCE saw the number of applications collapse to less than 1% of their customers despite increasing demand. This suggests that even increasing resources to apply does not necessarily deliver the outcome because energy suppliers complicate access to a resource they are legally obliged to provide. The administration of this benefit is done through the energy companies and at their discretion. The outcome is that clients of specific energy suppliers have their secondary capability to access this benefit effectively removed. This dynamic is also present in the administration of the WHD and as such leads to more complex and demanding work for energy advisors (see ).

4.3. Organisational energy poverty alleviation in the context of Great Britain’s liberalised electricity market

As mentioned above, one needs to bear in mind that these figures fail to paint a complete picture of what energy poverty advice is, what it can achieve, and how it supports capability among the most vulnerable members of society. These figures also fail to provide a complete picture of the underlying processes. The following is an excerpt from a 2016 report submitted by one of the organisations to their funder. It highlights energy poverty alleviation funding and data reporting issues and summarises the importance of this analysis:

The funding certainly doesn’t cover time needed for any follow up advice such as tracking identified savings. Many beneficiaries will only switch once they have discussed the issue with fellow householders and only if they have this vital follow up support. […] Funding simply does not allow for this following up work. […]. Maybe it would be better to record ALL identified savings then also record if they switched or not. For example, during March we identified savings totalling £7,864 but actually people switching on the day £3,064. […]. The focus on recording savings from switching underestimate the total savings from a combination of switching and access to the [Warm Home Discount].

This trend is even more pronounced regarding the numbers of WHD applications on the day () compared to the share of SELCE customers who either receive or could receive the WHD (by applying once it reopens or by switching to a supplier supporting the scheme; ). indicates that in 2020/21 over half of SELCE clients were entitled to WHDs although the share of clients who were actually signed up by SELCE was <1%. This follows a trend of rapidly rising eligibility since 2018/19 which reflects the figures for ESC’s applications on the day in .

These trends suggest that energy poverty alleviation eligibility both through supplier switching and WHD is increasing, especially during the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020/2021 (see and ). As WHDs are limited to the “core group” who receive specific benefits and the “broader group” below an income threshold this might be an indication of increasing energy poverty as a result of Covid-19. It also highlights a consistent problem with passport benefits (those that require some qualifying characteristic such as being disabled), especially ones that have been outsourced, as significant proportions of people never apply (Graeber Citation2018). This can be because they simply are unaware due to the complexity and opacity of potential benefits associated with liberalised electricity markets, or more insidiously because of the stigma attached to certain benefits in Great Britain (Baumberg Citation2015 ).

While switching suppliers and applying for WHDs can ensure that the energy poor do not pay a poverty premium and that they receive benefits they are entitled to, these figures also reveal that reaching out to vulnerable members of society and helping them out of energy poverty involves a lot more than identifying savings on their energy bills. In capability terms, enabling these secondary capabilities of switching supplier or accessing information on and accessing benefits and support is, as stated above, enabling of the more abstract basic capabilities of good health and maintaining social respect. At the same time, the role community energy organisations play extends far beyond ensuring these secondary capabilities to the provision advocacy and an overall ethic of care and solidarity with those suffering energy poverty. This is explored in more detail in the following case studies.

4.4. Organisational energy poverty case study data

These case studies from ESC and SELCE are examples of their work with the energy poor – in East Sussex and South London. ESC created 220 such case studies in 2015–2016 as part of Climate Action Network funded project, from which we have chosen two. This case study data covered 29 metrics in total. Both ESC and SELCE also routinely develop one-page narrative case studies to accompany their quantitative data and shed light onto personal stories behind the bare figures and to evidence the scope and depth of their energy poverty alleviation efforts, partly to satisfy funders’ requirements and partly to make an argument for more structural support for the sector. We have chosen two of these from SELCE. The four case studies analysed below were chosen as they cover distinctly different demographics spanning a young family, a retired couple, a single mother, and a person suffering health issues living alone which serve to highlight the role that organisations such as ESC and SELCE play in supporting a diverse range of capabilities. These case studies have been analysed using Middlemiss et al.’s (Citation2019) capability concepts of reasons, resources, roles and collectivities, which can be seen as the surrounding conditions of possibility of capabilities and broader human flourishing. The following case studies, two from ESC (1, 2) and two from SELCE (3, 4), have been significantly shortened to ensure anonymity:

| (1) | A couple who are working and receiving tax credits but on low incomes. They have water debt and struggle to stay warm in a private rental with damp and mould and a very old boiler. Their children are suffering health issues as a result of cold and damp. ESC installed a data logger to measure humidity levels and referred the case to a local authority support scheme (Warm Home Check). The humidity levels from the datalogger showed 80–95% in one child’s bedroom (60% humidity is when harmful spores proliferate). ESC enlisted support from local Member of Parliament on the issue of water bill debt. An Energy Performance Certificate was completed ( = E 51) and ESC was informed the landlord was selling the house. | ||||

Analysis: a mixture of a role and resource here is employment. Similar to benefits, those in insecure and less skilled employment are not being paid enough for social reproduction. Tax credits themselves have been critiqued as a subsidy and reason for employers to underpay workers (Farnsworth Citation2015), while wages in general have stagnated since 2007 with only the top 1% really gaining and lower income deciles not growing at all (Cribb et al. Citation2021). This extractive dynamic of the UK economy is why Galvin (Citation2020, 68) argues that when researching energy and energy access, we must place our analysis and findings against a “lopsided, billionaire serving social structure that characterises today’s world”. The resource of the house is again substandard with dangerous levels of humidity in a child’s bedroom. This is an example of child poverty, which has increased since 2010 as children’s services in the most deprived areas have been systematically removed (Bayliss and Mattioli Citation2018; Marmot et al. Citation2020). Added to its substandard nature, this housing is also insecure with landlords able to evict with very little recourse for tenants. A reason for this asymmetry of power in the housing sector is complex but can be traced back to the right-to-buy of social housing policy in the 1980s, and the broader contours of the UK rentier economy where power resides with those that own assets, including housing, over those that do not (Askenazy Citation2021; Christophers Citation2020).

In this case, ESC could act as a convenor of support through the local MP and through the use of monitoring devices to measure a problem. However, ESC’s options here were limited with the law firmly favouring the landlord both in their ability to evict and sell the property, and local authorities’ lack of capacity due to significant cuts in deprived areas (Marmot et al. Citation2020; Gray and Barford Citation2018). This is likely to have reduced oversight of landlords and allowed certain actors to profit from properties with serious environmental health risks and very low energy efficiency.

| (2) | A retired couple living in their own partially insulated home with an old boiler, insufficient radiators and generally cold temperature. They are disabled meaning they cannot reach their gas or electric metres. They receive pension credit but not Disability Living Allowance (which has since been replaced by Personal Independence Payment) despite being clearly disabled. Parts of the house are unusually cold and affected by damp and mould. ESC instigated multiple interventions, arranged an Energy Performance Certificate, repaired the boiler, and referred the client to local authority services. ESC also supported the client in switching tariff, and metres to make them accessible. An application for a new boiler through the ECO programme was made but was unsuccessful as the client had no savings with which to contribute. | ||||

Analysis: two collectivities emerge here, that of pensioners and again the disabled. Pensioners as a broad social group have many advantages in Great Britain including the likelihood of being in the role of a homeowner, and being eligible for the only universal (and fairly funded through income tax) energy poverty benefit, the Winter Fuel Payment. However, these averaged advantages hide many pensioners who suffer from poverty. Also, owning the resource of a home without the funds to manage this can turn an asset into a burden, an issue exacerbated by the generally old and poorly constructed nature of UK housing (Rudge Citation2012). These people are described as clearly disabled but are denied the support of any disability allowance, which serves as an example of Clifford’s (Citation2020) argument that disabled people have been routinely targeted by successive austerity driven governments.

Finally, while ESC managed to achieve a lot and clearly helped these people, this case shows the severe limitations of government policy, especially in relation to the ECO. The failure of the application for the new boiler was down to the clients not having money to contribute to this cost. This is a specific example of the reason many people are suffering from energy poverty in the UK today: government support is being rationed under the logic of austerity, with these cases potentially remaining undiscovered without the work of organisations such as ESC, leaving the question of who does this essential work when there are no community groups willing or able to do this (Middlemiss Citation2017).

| (3) | A working single mother with very little knowledge about different electricity tariffs. After the advice sessions she used a switching site to find a better rate for dual energy and made nearly £100/a savings and passed on this information to a friend as was delighted at how easy it was to swap supplier. As a result of taking the time to attend the session, she has learned of several energy saving tips and said that she would definitely recommend the sessions to her friends and family in the future. | ||||

Analysis: A mixture of role and collectivity here is that of a single working mother. From a variety of literatures, it is clear this figure/group experiences many intersecting injustices that limit their functioning and capabilities. From the energy perspective we have a system designed by and for men with, for instance, time-of-use tariffs penalising especially less affluent mothers unable to move the energy use around in time prosumer-like (Sunikka-Blank and Galvin Citation2021). In this case the informational resources SELCE provided led to the woman engaging the collectivity of her friendship and family networks in order to share information such as energy saving tips or advice about benefits people are entitled to but unaware of. This is evidence of relationality and how people are always more than the selfish individuals neoliberal capitalism tends to frame people as (Dryzek Citation2013). It is also evidence that communicating energy literacy and climate crisis awareness is best done through local intermediaries such as community energy actors (Catney et al. Citation2013).

| (4) | An unemployed woman with no money in the bank and no food in the fridge. To keep warm, she had been staying in bed with a hot water bottle as her boiler had broken down. Her only heating was a fan heater. The immediate priorities were not about energy so the SELCE advisors arranged food bank vouchers and identified that she was not accessing all the benefits to which she was entitled. She had applied for the Warm Home Discount, but this had been rejected simply because the energy company had not understood the complexity of her health problems. The SELCE advisor supported her to re-apply for Warm Home Discount and funds were immediately credited to her account. She was nonetheless paying over the odds for her energy. The SELCE advisor helped the woman access benefits and savings that amount to well over £1500 p/a. | ||||

Analysis: This final case shows how intersecting aspects of impoverishment can remove most basic functioning and capabilities. This woman in her role/collectivity of being unemployed and through lack of money and food was reduced to remaining in bed to stay warm. While her health problems were not specified, it is fair to speculate that interacting causes and effects of energy poverty and poor mental and physical health are likely exacerbated when people are isolated and confined in such a way (Poortinga Citation2019). As resources there is the broken boiler, which led to the woman to using a fan heater and hot-water bottle, both less efficient and more expensive forms of heating, thus compounding the problems. The reasons for this figure of the unemployed, sick woman to be denied basic human capabilities of health and dignity are the result of a punitive benefit system that is explicitly designed to discipline people into work, regardless of this work often being insecure and not being much better than inadequate benefits (Chatzidakis et al. Citation2020, 1).

5. Discussion

Energy poverty alleviation data analysed in this paper, which coincides with a period of rapid electricity supply decarbonisation, suggests that those in energy poverty are not among the beneficiaries of associated policies and liberalised energy electricity market structures. It shows how organisations such as ESC and SELCE play a key role in providing an ethic of care, treating people with respect, listening to their problems, and trying to address these in difficult circumstances for everybody involved. As such, these organisations are not just helping their clients with their basic capabilities of health and more general well-being, but also respecting people as humans and contributing to the cooperative social relations that help to define us. This research complements earlier findings which points towards the important role that intermediaries such as the organisations analysed above play in ensuring that vulnerable households exercise the agency they are assumed to have in basic economic terms (Ambrosio Alaba et al. Citation2020).

In terms of basic capabilities, these findings suggest that government and energy supplier’s targets and metrics regarding energy poverty alleviation tend to miss the point in quantifying the unquantifiable (Graeber Citation2018). While medically we can break down health to quantifiable indicators, for more abstract basic capabilities such as well-being and social respect, this becomes more tenuous. What is needed here is an understanding that the secondary capabilities such as accessing information, adequately heating a home, or washing clothes, all contribute to these more basic capabilities of well-being and social respect (Day, Walker, and Simcock Citation2016). As such, support should not be rationed and based on the existence or not of organisations such ESC or SELCE, as this risks what might be called regional capability conflicts or postcode lotteries of injustice. Rather, more universal support should form part of a future economy based on need, part of our responsibility to each other, and a fundamental part of governmental responsibility to the people it ostensibly represents and is there to serve.

This puts into question government commitment to addressing both climate change and energy poverty. The increasing share of SELCE and ESC clients switched to cheaper suppliers also points towards a persistent issue of loyalty being punished (see Tables 6 and 7; Boardman Citation2010; BEIS Citation2018). Furthermore, support schemes such as ECO and WHD, although they are aimed at energy poverty alleviation, as well as those supporting rapid decarbonisation, such as the feed-in tariff and Contracts for Difference, are funded through climate levies on electricity bills. This implies that the energy poor effectively pay for this support through electricity bills which represent a larger share of their overall expenditure compared to affluent households (Granqvist and Grover Citation2016). Owen and Barrett (Citation2020) calculate that this higher proportion paid by the lowest income groups for this energy transition exceeds the support offered to these groups by approximately £61 million. Given the difficulty of accessing WHD, evident in the case studies, with a history of funds running out and at least one company limiting registration to one week in April, this amounts to a regressive and dysfunctional tax. It is also a capability conflict that was all too predictable as it was identified nearly thirty years ago (Boardman Citation1993).

Benefits of a liberalised electricity market regarding cheap tariffs are only possible because electricity suppliers place their most loyal customers on expensive variable tariffs. Moreover, following the raising of the price cap and the crisis in gas supply in autumn 2021, switching suppliers and saving money options vanished. The war in Ukraine and successive liftings of the price cap has exacerbated this problem. As electricity market competition and switching served as one of the main branches of energy poverty support, what will happen in the near and medium future is highly uncertain. In connection, the increasing share of clients who could benefit from WHDs might also point towards an increase in energy poverty as a result of Covid-19. Organisations such as SELCE and ESC now play a more vital role than ever both in ensuring that vulnerable members of society can avoid paying a poverty premium by accessing the benefits they are entitled to, whether they arise from the liberalised electricity market or not, and in identifying such members of society in the first place (Committee on Fuel Poverty Citation2021).

6. Conclusion

This paper provides evidence of Britain’s liberalised electricity market’s persistent failure to address energy vulnerabilities in times of rapid grid decarbonisation. Although official calculations of people in energy poverty suggested a declining trend until the crisis in gas supply starting in autumn 2021, especially when using the latest Low Income and Low Energy Efficiency (LILEE) measure, the organisational data analysed in this paper suggests that demand and eligibility for fuel poverty alleviation services started increasing well in advance of recent price spikes. These findings reinforce the notion that few things have changed since Boardman (Citation2010, 90) suggested that “the liberalised market is working and the better-off are benefiting handsomely from it, as they have for some time”.

Methodologically, however, it needs to be recognised that many factors influence such organisational data, and that increasing numbers of switches in particular might reflect the growing expertise among community energy advisors in providing such services. On the other hand, consistent data among the two organisations on potential savings and eligibility suggest that overall demand for their services is increasing. Similar data trends, despite the different demographic and ethnic composition of their client base, also support previous findings (see Boardman Citation2010; CMA Citation2016; BEIS Citation2018). These suggest that benefits arising from the UK’s liberalised retail electricity market’s consumer choice model tend to benefit savvy and engaged consumers while the costs of this model are disproportionately borne by those least likely to make active choices: energy poor and vulnerable members of society.

Concrete steps to ensure that the next transition is more inclusive need to start with better data. This could be provided through the development and dissemination of a single data capturing and management tool as well as a centralised database for all organisations engaging in energy poverty alleviation. This would help overcome issues of underreporting at an organisational level and overreporting at a funding level. Together with data analysis support it would facilitate comparability and provide the basis for more targeted intervention. In the long run, better data gathering, management and analysis support would encourage better evidence and business model innovation among energy poverty alleviation organisations. This in turn might encourage more targeted policy support by government.

The current funding structure, which is seasonal, driven by targets (rather than data) and complicated by increasing compliance requirements, needs to be replaced with an emphasis on service continuation and the recognition that moving out of energy poverty is a long-term process, not just an issue of quick wins by switching to a cheaper tariff which vanish in times of rising inflation and energy scarcity. More resources are necessary to help energy poverty alleviating organisations both capture their input and follow up on their output, especially regarding recipients of advice and support, to get a better understanding of who, where and when has benefited and how this has affected their journey out of energy poverty or confined them to a life in energy poverty in perpetuity due to inadequate funding structures.

Overall, it needs to be more widely recognised that the benefits of liberalised electricity markets, including rapid electricity supply decarbonisation, do not readily translate into transparency, inclusivity, or justice at the point of demand. For an energy transition to be just, and for the rhetoric of “leaving no one behind” to be more than words, we need to act on the data above showing how housing and benefit systems require restructuring and supportive organisations long-term funding. Above all, the focus needs to shift towards reducing the energy demand of our housing stock. As mentioned above, recent official publications such as the Energy Security Strategy (BEIS Citation2022) place strong emphasis on supply. Associated infrastructures, however, take years if not decades to build. Yet it has long been established that tackling energy poverty is a housing infrastructure issue (see Boardman Citation1993, 2010). The same holds true, at least in part, for tackling climate change (HM Government Citation2008; Eyre and Killip Citation2019). Reducing energy demand across the housing stock would also shrink the size of the energy market which requires decarbonisation, thereby reducing societal costs as well as costs born specifically by those in energy poverty. The inability of the latter to pay for energy efficiency retrofits, however, needs to be taken into account in policymaking.

To address it, the UK requires a national housing retrofit strategy combined with long-term loans (also known as patient capital) underwritten by a government-backed bank, similar to Germany’s KfW-Bank. For energy poor households, the investment could be tied to energy savings and a zero-interest loan. Associated carbon emission reductions could be monetised as carbon credits paid through a rising carbon floor price for fossil fuel extraction companies, by taxing kerosene, and by imposing frequent flyer levies. Although these are expensive, long-term, and market distorting commitments, such radical approaches are the only structural changes capable of reducing household exposure to the vagaries of commodity markets.

The costs of inaction are exorbitant, while ethically allowing millions of households to live with their secondary and basic capabilities truncated is unconscionable.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC), Impact Accelerator Account (IAA), Accelerating Business Collaboration (ABC) under Grant Agreement Number ES/V502182/1; and the Centre for Research into Energy Demand Solutions, UK Research and Innovation, Grant agreement number EP/R035288/1.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ambrosio Alaba, P., L. Middlemiss, A. Owen, T. Hargreaves, N. Emmel, J. Gobertson, A. Tod, et al. 2020. “From Rational to Relational: How Energy Poor Households Engage with the British Retail Energy Market.” Energy Research & Social Science 70 (101765): 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2020.101765.

- Askenazy, P. 2021. Share the Wealth: How to End Rentier Capitalism. London: Verso.

- Baumberg, B. 2015. “The Stigma of Claiming Benefits: A Quantitative Study.” Journal of Social Policy 45 (2): 181–199.

- Bayliss, K., and G. Mattioli. 2018. Privatisation, inequality and poverty in the UK: Briefing prepared for UN Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights. Sustainability Research Institute Papers No. 116.

- Bayliss, K., G. Mattioli, and J. Steinberger. 2020. “Inequality, Poverty and the Privatization of Essential Services: A ‘Systems of Provision’ Study of Water, Energy and Local Buses in the UK.” Competition & Change 25 (3-4): 478–500. doi:10.1177/1024529420964933.

- BEIS. 2018. Modernising Consumer Markets – Consumer Green Paper. London: Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy.

- BEIS. 2020. Sub-regional Fuel Poverty England 2020 (2018 Data). London: Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy.

- BEIS. 2021. Sustainable Warmth – Protecting Vulnerable Households in England. London: Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy.

- BEIS. 2022. British Energy Security Strategy. London: Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy.

- Boardman, B. 1991. “Fuel Poverty is Different.” Policy Studies 12 (4): 30–41. doi:10.1080/01442879108423600

- Boardman, B. 1993. “Energy Efficiency Incentives and UK Households.” Energy & Environment 4 (4): 316–334. doi:10.1177/0958305X9300400401

- Boardman, B. 2010. Fixing Fuel Poverty: Challenges and Solutions. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Bouzarovski, S. 2018. Energy Poverty - (Dis)Assembling Europe's Infrastructural Divide. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Catney, P., S. MacGregor, A. Doson, S. M. Hall, S. Royston, Z. Robinson, M. Ormerod, and S. Ross. 2013. “Big Society, Little Justice? Community Renewable Energy and the Politics of Localism.” Local Environment: The International Journal of Justice and Sustainability 19 (7): 715–730.

- CCC. 2019. Net Zero – The UK’s Contribution to Stopping Global Warming. London: Climate Change Committee.

- CCC. 2022. Progress in Reducing Emissions – 2022 Report to Parliament. London: Climate Change Committee.

- Chatzidakis, A., J. Hakim, J. Littler, C. Rottenberg, and L. Segal. 2020. “From Carewashing to Radical Care: The Discursive Explosions of Care During Covid-19.” Feminist Media Studies 20 (6): 889–895. doi:10.1080/14680777.2020.1781435

- Christophers, B. 2020. Rentier Capitalism: Who Owns the Economy, and who Pays for it? London: Verso.

- CLF. 2016. Understanding Fuel Poverty. Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Chesshire Lehman Fund.

- Clifford, E. 2020. The War on Disabled People: Capitalism, Welfare and the Making of a Human Catastrophe. London: Zed Books Ltd.

- CMA. 2016. Energy Market Investigation: Final Report. London: Competition and Markets Authority.

- Committee on Fuel Poverty. 2021. Committee on Fuel Poverty – Annual Report. London: Committee on Fuel Poverty.

- Cribb, J., T. Waters, T. Wernham, and X. Xiaowei. 2021. Living Standards, Poverty and Inequality in the UK: 2021. London: Institute for Fiscal Studies.

- Curtis, S. 2019. Big Energy Saving Network Evaluation. London: The National Association of Citizens Advice Bureaux.

- Day, R., G. Walker, and N. Simcock. 2016. “Conceptualising Energy use and Energy Poverty Using a Capabilities Framework.” Energy Policy 93: 255–264. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2016.03.019

- Dryzek, J. 2013. The Politics of the Earth: Environmental Discourses. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Eyre, N., and G. Killip. 2019. Shifting the Focus: Energy Demand in a net-Zero Carbon UK. Oxford: Centre for Research into Energy Demand Solutions.

- Farnsworth, K. 2015. “The British corporate welfare state: Public provision for private businesses.” SPERI paper, 24.

- Foxon, T., G. Hammond, and P. Pearson. 2010. “Developing Transition Pathways for a low Carbon Electricity System in the UK.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 77 (8): 1203–1213. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2010.04.002

- Galvin, R. 2020. “Asymmetric Structuration Theory: A Sociology for an Epoch of Extreme Economic Inequality.” In Inequality and Energy: How Extremes of Wealth and Poverty in High Income Countries Affect CO2 Emissions and Access to Energy, edited by R. Galvin, 52–74. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press.

- Graeber, D. 2018. Bullshit Jobs: The Rise of Pointless Work, and What we Can do About it. London: Penguin.

- Granqvist, H., and D. Grover. 2016. “Distributive Fairness in Paying for Clean Energy Infrastructure.” Ecological Economics 126: 87–97. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2016.02.012

- Gray, M., and A. Barford. 2018. ““The Depths of the Cuts: The Uneven Geography of Local Government Austerity.” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 11 (3): 541–563. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsy019

- Grey, C. N., T. Schmieder-Gaite, S. Jiang, C. Nascimento, and W. Poortinga. 2017. “Cold Homes, Fuel Poverty and Energy Efficiency Improvements: A Longitudinal Focus Group Approach.” Indoor and Built Environment 26 (7): 902–913. doi:10.1177/1420326X17703450

- Hinson, S. and P. Bolton. 2020. Fuel Poverty. Briefing Paper Number 8730. House of commons Library.

- HM Government. 2008. The Climate Change Act 2008. London: Her Majesty's Government.

- Lewisham JSNA. 2021. Lewisham’s Joint Strategic Needs Assessment – Ethnicity. Accessed October 3 2021. http://www.lewishamjsna.org.uk/a-profile-of-lewisham/social-and-environmental-context/ethnicity#:~:text=Lewisham%20is%20the%2015th%20most,the%20total%20population%20of%20Lewisham.

- Mallaburn, P., and N. Eyre. 2014. “Lessons from Energy Efficiency Policy and Programmes in the UK from 1973 to 2013.” Energy Efficiency 7: 23–41. doi:10.1007/s12053-013-9197-7

- Marmot, M., J. Allen, T. Boyce, P. Goldblatt, and J. Morrison. 2020. “Health Equity in England: The Marmot Review 10 Years on.” BMJ 368 (368): 1–170. doi:10.1136/bmj.m693.

- Martiskainen, M., E. Heiskanen, and G. Speciale. 2017. “Community Energy Initiatives to Alleviate Fuel Poverty: The Material Politics of Energy Cafes.” Local Environment 23 (1): 20–35. doi:10.1080/13549839.2017.1382459

- Martiskainen, M., B. Sovacool, M. Lacey-Barnacle, D. Hopkins, K. Jenkins, N. Simcock, G. Mattioli, and S. Bouzarovski. 2020. “New Dimensions of Vulnerability to Energy and Transport Poverty.” Joule 5 (1): 3–7. doi:10.1016/j.joule.2020.11.016

- Meadows, D. 1999. Leverage Points - Places to Intervene in a System. Hartland, VT: The Sustainability Institute.

- Middlemiss, L. 2017. “A Critical Analysis of the new Politics of Fuel Poverty in England.” Critical Social Policy 37 (3): 425–443. doi:10.1177/0261018316674851

- Middlemiss, L., P. Ambrosio-Albalá, N. Emmel, R. Gillard, J. Gilbertson, T. Hargreaves, C. Mullen, T. Ryan, C. Snell, and A. Tod. 2019. “Energy Poverty and Social Relations: A Capabilities Approach.” Energy Research & Social Science 55: 227–235. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2019.05.002

- Nolden, C., N. Eyre, and T. Fawcett. 2021. "Energy Demand Policymaking Attention in the Context of a Just Transition to Net Zero: Results of a UK Survey." ECEEE Summer Study 2021 Proceedings 2-027-21:141-151.

- Nussbaum, M. 2003. “Capabilities as Fundamental Entitlements: Sen and Social Justice.” Feminist Economics 9 (2-3): 33–59. doi:10.1080/1354570022000077926

- Ofgem. 2008. Energy Supply Probe: Initial Findings Report. London: Office For Gas and Electricity Markets.

- Owen, A., and J. Barrett. 2020. “Reducing Inequality Resulting from UK low-Carbon Policy.” Climate Policy 20 (10): 1193–1208. doi:10.1080/14693062.2020.1773754

- Poortinga, W. 2019. “Health and Social Outcomes of Housing Policies to Alleviate Fuel Poverty.” In Urban Fuel Poverty, edited by K. Fabbri, 239–258. Cambrige, MA: Academic Press.

- Poudineh, R. 2019. Liberalized Retail Electricity Markets: What we Have Learned After two Decades of Experience. OIES Paper: EL 38. Oxford: The Oxford Institute for Energy Studies.

- Public Health England. 2017. Cold Weather Plan for England – Making the Case: Why Long-Term Strategic Planning for Cold Weather is Essential for Health and Wellbeing. London: Public Health England.

- Reeves, A. 2016. “Exploring Local and Community Capacity to Reduce Fuel Poverty: The Case of Home Energy Advice Visits in the UK.” Energies 9 (4): 276. doi:10.3390/en9040276

- Rosenow, J., and N. Eyre. 2016. “A Post-Mortem of the Green Deal: Austerity, Energy Efficiency, and Failure in British Energy Policy.” Energy Research & Social Science 21: 141–144. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2016.07.005

- Rosenow, J., and L. Sunderland. 2021. What has gone wrong with the Green Homes Grant? Green Alliance Blog. Accessed 3 November 2021 https://greenallianceblog.org.uk/2021/02/18/what-has-gone-wrong-with-the-green-homes-grant/.

- Rudge, J. 2012. “Coal Fires, Fresh air and the Hardy British: A Historical View of Domestic Energy Efficiency and Thermal Comfort in Britain.” Energy Policy 49: 6–11. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2011.11.064

- Sen, A. K. 2009. The Idea of Justice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Smith, M. L., and C. Seward. 2009. “The Relational Ontology of Amartya Sen’s Capability Approach: Incorporating Social and Individual Causes.” Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 10 (2): 213–235. doi:10.1080/19452820902940927

- Sunikka-Blank, M., and R. Galvin. 2021. “Single Parents in Cold Homes in Europe: How Intersecting Personal and National Characteristics Drive up the Numbers of These Vulnerable Households.” Energy Policy 150 (112134): 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2021.112134.

- Thomas, S. 2019. “Is the Ideal of Independent Regulation Appropriate? Evidence from the United Kingdom.” Competition and Regulation in Network Industries 20 (3): 218–228. doi:10.1177/1783591719836875

- Urbistat. 2021. Maps, analysis and statistics about the resident population. Accessed 3 November 2021 https://ugeo.urbistat.com/AdminStat/en/uk/demografia/dati-sintesi/england/1/2.

- Walker, G., and R. Day. 2012. “Fuel Poverty as Injustice: Integrating Distribution, Recognition and Procedure in the Struggles for Affordable Warmth.” Energy Policy 49: 69–75.

- Wood, N., and K. Roelich. 2019. “Tensions, Capabilities, and Justice in Climate Change Mitigation of Fossil Fuels.” Energy Research & Social Science 52: 114–122. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2019.02.014