ABSTRACT

Academic research on mining and climate change and associated impacts on water resources particularly for the developing world has been limitedly explored. Climate change is expected to make water insecurity in rural areas more severe as weather patterns become unfavourable. The extent to which the mining sector is able to reduce its impact on water resources and adapt to climate change will have implications for host communities. This paper explores the relationship between climate change, mining development and water security and how this places rural communities in a position of risk from mining development and climate change for water security. This paper focuses on the Fuleni and Somkhele rural communities located within the uMkhanyakude District Municipality in Northern KwaZulu-Natal, a climate change-induced water scarce area. Despite drought, mining operations continue. Semi-structured interviews were used to collect data from key social actors in the Fuleni community (i.e. residents opposing mining development) and with Somkhele residents (already burdening with mining operations). Additionally for Somkhele, a questionnaire was used to ascertain 424 household views on the impacts of climate variability and mining impacts on livelihoods and water. Results indicated an interplay between climate change, mining impacts and water (and food) security. Development must be implemented in an integrated and holistic manner that contributes to sustainable development and does not impact on water resources. Technological innovations related to water and energy and inter-sectoral collaborations must be prioritised between mining, the government, and civil society, to achieve water security.

Introduction

Globally, there is now increased attention to the significance of water issues in the mining sector from industries, civil society, shareholders and governments, including further vulnerability to water insecurity due to climate change causing many community-mining conflicts (Kunz Citation2020). Whilst important work has been done on the link between climate change and mining by these social actors, there remains a death of academic research on mining and climate change and associated impacts on water resources particularly for the vast majority of developing world, where some of the gravest vulnerabilities to climate change exist (Odell, Bebbington, and Frey Citation2018). Climate change is expected to make water security and for food and agricultural development in Sub-Saharan Africa and across the continent more difficult as weather patterns become less favourable (AfricaPLC Citation2020). Sub-Saharan Africa is most vulnerable to climate change since warming will be greater than the global average, and agriculture, mainly rain-fed, is the primary source of subsistence for rural communities (Di Falco Citation2018). In 2019, Southern Africa was one of the regions affected by a prolonged drought from 2014–2016. Temperatures exceeding 2°C above the 1981–2010 average were recorded in South Africa, Namibia and parts of Angola (World Meteorological Organization Citation2020). Considering climate change impacts, the extent to which the mining sector is able to diminish its own impact on resources such as water and itself adapt to climate change will affect its long-term success and prosperity, and have deep conflict and implications for host communities and their access to water resources (Pearce et al. Citation2011). Mining such as for coal depend on water to extract, wash, and process coal, and more than 50 percent of the world’s largest coal-producing/consuming countries face high to extremely high levels of water stress (e.g. South Africa is ranked number 7 with a high water stress level), which can be attributed to the many competing demands on water resources (Luo Citation2014). For South Africa, the country is on the verge of experiencing a 17% gap in water supply and demand by 2030 if no looming action is taken to combat the crisis (Ziervogel et al. Citation2014). Globally and at the regional and local scales in many countries, mining may result in significant impacts on freshwater resources due to high energy industries dependence on water (Luo Citation2014), particularly when water consumption surpasses the carrying capacities defined by the amount of available water and also considering environmental water requirements (Meißner Citation2021). According to the University of California – Santa Barbara (Citation2021) mining operations can continue to affect ecosystems long after operations cease, with heavy metals and corrosive substances leaching into the waterways and environment and preventing wildlife and vegetation from recurring to the area.

Within the above context, this paper will focus on the Fuleni and Somkhele rural communities located within the uMkhanyakude District Muncipality in Northern KwaZulu-Natal. In the face of severe climate crisis impacting on water scarcity and supply in the region, this study examines the additional impacts that mining will have on water security and residents livelihoods. The uMkhanyakude District Muncipality region is a climate change-induced water scarce area (Patrick Citation2021). Streamflow variability in the Mfolozi River may be linked to multiple factors one of which is due to variable precipitation and the occurrence of regionally pervasive climatic oscillations (Grenfell and Ellery Citation2009). Climate change projections indicate that rain-fed agriculture in uMkhanyakude is likely to be negatively affected, due to lower annual rainfall, increased temperatures, more hydrological risk, increased rainfall variability, drying of top soils, limited water in the soil for irrigating plants, and increased irrigation needs (Mthembu and Hlophe Citation2020).

The municipality is 12 818 km2 and with a population totalling 625,846 (uMkhanyakude District Muncipality Citation2022). Whilst Somkhele has an existing mining operation, the Tendele cast coal mine, which has been operating since 2007 (Hansen and Bandile Citation2015), Fuleni about ten kilometres away is being targeted for mining development, despite climate change impacting on water reserves in the region. According to Carnie (Citation2017) there are plans by the Ibutho Coal Mining Company to develop an anthracite open cast coal mine in the area, and which borders the important tourist Hluhluwe-iMfolozi nature reserve – the oldest nature reserve in Africa. Some residents and civil society have been opposing the mining application due to environmental, social and local livelihood impacts (Hans Citation2016). Youens (Citation2016) notes that the proposed mine will directly affect more than 1600 households and about 16,000 people. Unfortunately, mining as a neoliberal form of capital development can create struggles over land use changes and reflect conflicts over political order, competing views over nature, territory and sovereignty, including economic development (Leonard Citation2021).

Like the Fuleni residents, a limited number of Somkhele community residents have been opposing mining development due to social and environmental impacts from the existing mine (e.g. water shortages and other environmental and livelihood impacts) (Youens Citation2016; Jolly Citation2016). Fuleni residents have also witnessed the negative impacts of mining in Somkhele and some therefore do not want mining in their community (Hans Citation2016). According to Hargreaves (Citation2016), women in Somkhele and Fuleni live in patriarchal communities where they are responsible for domestic work and care of families. These women have taken their concerns about the mining impacts on water and lack of water to the traditional leaders but leaders have poorly responded and have punished women with fines for subverting the “rule” that women cannot bring matters directly to male traditional leaders. According to the Umfolozi Integrated Development Plan (IDP) (Citation2020/2021) for the period 2017–2022, released by the Umfolozi Municipality, the Ibutho Coal plans for the development of the Fuyeni Anthracite Mine will have a life-of-mine of 30 years and will produce anthracite product suitable for export, with secondary lower grade thermal product for the domestic market. The IDP notes that community and stakeholders concerns related to the mine have included, noise, dust, vibration; reduced grazing and land use; public road diversions; resettlement of households and graves; community health and safety; impact on water sources, including catchment water balance and water quality. According to Jolly (Citation2015) Fuleni’s draft Environmental Impact Assessment 2015 noted that the negative impacts on the Mfolozi River were deemed medium-high with water quality impacts. All mining phases, namely construction, operation and decommissioning, would result in loss of in-stream surface and base flow, loss of stream flow regulation, loss of aquatic habitats and fish, and increased moisture stress on riparian vegetation. Furthermore, increased sediment due to increased erosion would contaminate rivers and pollutants released from the processing plant and would negatively affect water quality, as would acid mine drainage and fuel spills. Acid mine drainage combined with the increase of heavy metals from blasting could contaminate surface and groundwater downstream of the Fuleni mine.

This paper will focus on climate change and mining impacts on water security in the region and how the latter may worsening the water security issues for communities who have already been impacted on climate change, with mining a contributor to climate change. The paper also questions that if the region is already severely affected by climate change and has been experiencing drought, then why is mining developments allowed and further development being considered by government, which would add a double catastrophe for local communities for water security? This paper is divided into several sections including this introduction. The next section examines climate change and water security in KwaZulu-Natal so as to examine the severity of climatic changes on the rural populace. This is followed by exploring the Nexus: between mining, climate change and water and food security, before examining the root cause of mining problems such as governance and corruption proliferating mining impacts. The methodology and case area are then explained before presenting the results. The final section engages in the discussion and conclusion before making presenting some key recommendations.

Climate change and water security in KwaZulu-Natal

Weather events such as drought and heatwaves, are among the most principal natural extremes experienced in South Africa (Kruger and Nxumalo Citation2017). A global temperature rise of 2°C is likely to translate to a 4°C increase for the country with less rain for the west of South Africa, and potentially more intense floods in the east whilst the national demand for water is increasing (Rebelo Citation2019). The KwaZulu-Natal province in particular is predominantly rural, and most of the population is characterised by high-density poverty. Drought is characterised by water imbalances, failing water supplies, below average relative humidity, livestock deaths, crop failure, hunger and starvation, spiking food prices, and conflicts over natural resources such as water. The province is characterised by warm to scorching summers, heatwaves, wildfires, and moderate winters. The maximum daily air temperatures during the summer months are as high as 40.1°C in the Cape St Lucia region. There has been a declining water presence in the province over the years, an indicator of worsening water scarcity, a situation which is projected to evolve from bad to worse in the near future (Ndlovu et al. Citation2021). As Lottering, Mafongoya, and Lottering (Citation2021) note for the KwaZulu-Natal region, due to climate change, droughts will have severe and uneven impacts on poor rural communities and small-scale farmers who base their livelihoods on rain fed agriculture and are socially vulnerable to climate change and with a failure of water resources to meet their water demands. Similarly Masinga, Maharaj, and Nzima (Citation2021) in their study on adapting to climate change conditions in KwaZulu-Natal found that women in rural areas have been experiencing a reduction in harvests due to drought, with diversification of livelihoods through fishing having been affected, as water sources have dried up. Considering the above evidence, the addition of mining developments will further affect water resources in some areas and constrain the livelihoods of rural communities in the province.

The Nexus: mining, climate change and water and food security

There is an interplay between climate change, mining impacts and water security. The impact of mining on water resources, already exacerbated by climate change, has received some attention from civil society globally. For example, the mining sector in El Salvador has been criticised for impacting on the vulnerability of the country’s water resources under conditions of climate change. This was confirmed by a Strategic Environmental Assessment of the mining sector which highlighted that mining would use water resources that climate change would make scarcer, and that the frequency of severe storms would threaten the failure of mine infrastructure, with serious consequences for water contamination (Odell, Bebbington, and Frey Citation2018). Walter and Urkidi (Citation2017) note, for mining developments in Latin America, that there has generally been fear of mining development from local communities due to land contamination and ongoing environmental impacts, including loss of local livelihoods. Similarly, the South African Parliament noted in 2019 that 118 mines around South Africa were polluting rivers and inadequate testing for contamination was done for water pollution. Additionally, 115 mines were operating without proper water permits, compared to 39 mines in 2014 (Olalde and Matikinca Citation2019). In KwaZulu-Natal specifically, a team of Environmental Management Inspectors from the national Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment visited the province to investigate the collapse of a waste slurry dam at the Zululand Anthracite Colliery (ZAC) coal mine. An estimated 1.5 million litres of liquid coal waste containing toxins decanted into the Black Umfolozi and White Umfolozi River system. The mine has come under fire from several community members, environmental groups and the provincial conservation agency (Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife) due to pollution and the increasing volume of water consumption, especially during droughts and dry seasons (Carnie Citation2022). It is not unexpected then, that there has been global resistance by civil society against mining developments (Mavuso Citation2014). It is becoming common that ecological harms and resistance to mining is inherent to capitalism (Leonard Citation2021; Conde Citation2017).

In addition to mining impacting on water resources, these have implications for climate change and food security with an interconnectedness between energy, food, and water security. In Mpumalanga, South Africa, a key source of South Africa's coal supply, water availability, agriculture productivity and energy production are becoming progressively strained. The water quality deterioration generally results from either acid mine drainage or contaminated runoff from mines and agricultural lands. There is ongoing tension between agriculture for food security and coal mining for energy security resulting in competition for land. Mining has resulted in the deterioration of the quantity and quality of water (Simpson et al. Citation2019). Additionally Mpakeni residents in the province already note that severe drought episodes, which resulted in forage shortages, have become almost a yearly occurrence over the past decade (Ebhuoma et al. Citation2020). Whilst climate change is already impacting on water security as outlined above, mining is one of the causes of climate change. Mining is currently responsible for 4–7 percent of global greenhouse-gas emissions. Carbon dioxide emissions from the sector occur via mining operations and power consumption (i.e. 1 percent), and fugitive-methane emissions from coal mining (i.e. 3–6 percent), and the combustion of coal (i.e. 28 percent). Southern Africa is one of the water stress hotspots for mining (Delevingne et al. Citation2020). It is important to emphasise that climate change and extreme weather such as recurring droughts and floods can in turn pose challenges to the mining sector such as damage to mining infrastructure such as containment facilities and buildings, energy sources, tailings and waste disposal ponds, and transportation infrastructure such as bridges, roads, and pipelines can all be affected by extreme changes in weather patterns (Ndlovu et al. Citation2021). Thus a vicious cycle is present between climate change, mining impacts, water security and implications for food security due to drought or lack of water.

The root cause of mining problems: governance, corruption and mining impacts

Mining operations and developments continue in the new South African democratic dispensation to affect negatively people and the environment, especially for vulnerable areas situated next to mining operations (as noted in the previous section). Unfortunately, pristine areas have been targets for most mining developments in post-apartheid South Africa, having being approved by national and provincial government despite opposition from communities and civil society generally. Although South Africa’s economy is heavily dependent on coal, the country has no clear coal policy due to the obsession of the new government since 1994 surrounding policies to increase domestic household access to energy (Eberhard Citation2011). However, general legislation and policies are applicable (directly and indirectly) for the mining sector. One example is the 1996 Constitution which makes provision for a right to a healthy environment, and the right to have the environment protected by preventing pollution and degradation (South African Constitution Citation1996). Additionally, the (Citation1998) National Environmental Management Act (NEMA) emphasises that people’s needs must be put at the forefront when matters of environmental management are considered. One would therefore question why mining would be allowed and considered and if there may already be impacts on water resources? For example, groundwater in the mining district of Johannesburg is heavily contaminated and acidified and discharging into streams. Acid mine drainage (AMD) from coal mining is problematic in the Highveld coal field in Mpumalanga, with media attention noting the consequences of severe pollution witnessed in the Loskop dam and the Olifants river catchment (Naicker, Cukrowska, and Mccarthy Citation2003).

There are different reasons why mining impacts on people and the environment continues unabated. These may range from corruption within national government, and with traditional leaders and mining companies. A study by Leonard (Citation2019) in the Fuleni region highlighted corruption between the local traditional leadership council and the mining company influenced the lack of inclusion of the local community concerns over mining development. Corruption was also rife within the ward leadership council, the Ingonyama Trust Board and with the Zulu King, which therefore perpetuated local traditional leadership mining corruption. According to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (Citation2014) regarding the Antibribery Convention in South Africa, corruption remains a serious problem in the country with mining identified as one of the high-risk sectors. As MineWeb (Citation2011) highlighted, the South Africa’s elite police fraud investigation department, also known as the Hawks, raided the national Department of Mineral Resources (DMR) offices in 2011 surrounding a corruption investigation over the alleged issuance of rights to Imperial Crown Trading’s to part of a Sishen iron ore deposit. Pillay (Citation2007) adds that civil society and local community groups have accused the Department of Minerals and Energy (DME) for favouring mining applications with political connections. Leonard (Citation2017) referring to mining governance notes that the DMR’s lack of participation with civil society on mining developments and the department also dominating and limiting participation over mining development from other government departments (i.e. national Department of Water Affairs). Furthermore, fragmentation has also been due to indecisiveness as to which department/s needed to manage the environment, including poor cooperation and coordinating between government departments. Lack of human resources at all government levels contributed to ineffective monitoring of mining developments. The DMR offices were also investigated in 2011 for corruption over the illegal alleged issuance of mining rights. Collusion between the national DMR and some local government departments with the mining industries also contributed to ineffective governance and corruption and Malherbe and Segal (Citation2001) note, although South African legislation has attempted to sharpen corporate accountability for corporate actions post 1994, government institutions have not actively and publicly monitored corporate governance. Baumann (Citation2004) argues that public consultation continues to be conducted principally as a public relations exercise in “stakeholder management” rather than as a genuine attempt to engage with alternative views (i.e. civil society and local communities). It is thus clear that there is corruption and fragmentation between government departments when it comes to mining developments, which is a reason why mining is implemented in isolation from consideration over climate change and increased water insecurity impacts.

Methodology

Case study background

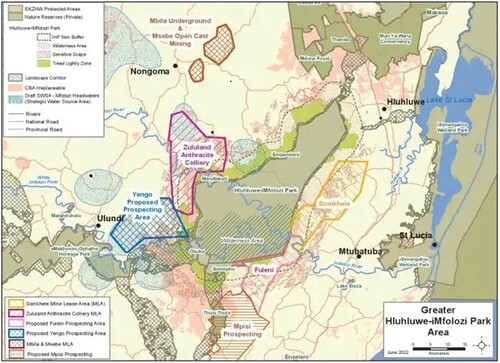

The background to the study site, located in the St. Lucia region, Northern KwaZulu-Natal province, South Africa, is that it is under the uMkhanyakude District Municipality. The proposed mine is also about sixty metres away from the Hluhluwe-iMfolozi Park, which is a world heritage site. The close proximity of the two communities has enabled that Somkhele residents have been educating the Fuleni residents about the negative impacts of mining. Both communities have been opposing mining development (Refer to below surrounding the geographical location of the case study site) Fieldwork to explore mining impacts on the community and water resources was examined in June 2016 (Fuleni community) and July 2017 (Somkhele community) as part of a larger study. Semi-structured interviews were used to collect data from key social actors in Fuleni (i.e. local community residents fighting mining and external civil society organisations providing support for the local Fuleni community opposing mining). A total of nine interviews were conducted as part of the Fuleni fieldwork. For the Somkhele case, interviewers were conducted with one youth community leader and a group interview was conducted with several local young adults ranging in age from 20–35 years. The one-on-one interviews were conducted based on purposive sampling and using a snowball technique. The group interview was organized by a local youth leader who contacted young people from the community. Additionally for data collection a questionnaire was used to ascertain responses from Somkhele residents regarding household views on the impacts of climate variability and mining impacts on livelihoods and water resources. Unfortunately, several attempts in 2016 to get interviews from key personnel such as the Secretariat: Regional Mining Development and Environmental Committee (RMDEC), KwaZulu-Natal, Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs (CoGTA), KwaZulu-Natal Wildlife, Naledi Development Consulting (the Fuleni mining consultants) and the Chief Executive Officer from Hluhluwe-iMfolozi Park – were unsuccessful, so the views of key social actors are not included, having implications on the findings. The author had also initially secured interviews with a local traditional leader from Somkhele, but the leader did not attend the scheduled interview.

Figure 1. Location of the Fuleni and Somkhele communities, the Hluhluwe-Mfolozi Park, the iSimamgaliso Wetland Park, the Mfolozi River, and in relation to coal mining developments. (Source: Youens Citation2022).

During the 2016 fieldwork in Fuleni it was observed that the mining site was to use water from the Umfolozi River, and which river was empty. The questionnaire also aimed to determine how climate variability impacted on Somkhele and what coping strategies were used by the community against climate change and water insecurity. In part the questionnaire also served to link the mining operation impacts on water resources and for the community already burdened with drought and lack of access to water and basic needs. The study further sought to explore the different ways in which the households responded to the change and how they survived. The questionnaire was divided in several sections (i.e. Demographics and Socio-economic status; Rural farming and food security; Water security; Impacts of climate change on agriculture, water and households livelihoods; and Mining impacts on the community and sustainable livelihoods). Fieldworkers assisted in personally administering questionnaire to residents within Somkhele. A training workshop was conducted by the researcher with the fieldworkers. A total of 424 questionnaires was fully completed and 11 questionnaires were excluded since they were partially filled in. The statistics department at the University of Johannesburg assisted in the analysis of all the questionnaires, including reviewing the initial draft questionnaire based on the aims and objectives of the research and to ensure validity of the questions. All informants interviewed and residents whom participated in filling in the questionnaires provided the required consent for participation. For the semi-structured interviews the author conducted thematic analysis to identify themes. Observation techniques were also employed during fieldwork such as level of the river. For this paper results are presented in relation to water and food security, climate change impacts on agriculture, water and household livelihoods and mining impacts on water security and residents.

Results

Climate change impacts on water resources and for local livelihoods

Climate change had caused widespread drought in KwaZulu-Natal and especially in the region under the uMkhanyakude District Municipality. Generally informants understood climate change as a change in weather climate patterns. Some of the responses as to what informants understood as climate change included, “ … a change in global or region climate patterns”, and, “ … a change in weather conditions experienced as a result of global warming”. All informants noted that climate change had caused drought in the region which impacted on water security. This impacted on agricultural productivity and the use of water in households. When the researcher visited the region in 2016 and 2017, it was observed on both occasions that the Umfolozi River was dry and drought conditions were evident. However, the Somkhele mine was said to be extracting around 250,000 litres of water a day from the river, questioning why government would consider allowing mining in the area – already hampered by dry conditions. An informant A (personal interview, July 2016), from the iMfolozi Communities and Wilderness Alliance (ICWA) noted, which was formed in August 2015 to unify opposition to the Ibutho Coal (Pty) Ltd mining application and to emphasise community involvement, highlighted the productivity of the area before drought set into the e region:

They [Fuleni community] have a project that is looking at farming because that area before the climate change and the drought occurred used to be a very, very productive agricultural area and livestock particularly cattle thrive there but now because of the drought [this is not the case] …

Due to the severity of drought conditions since 2015, residents in Somkhele and Fuleni had to source water from different locations. The main sources of water collection was from the Umfolozi River (i.e. 21%) and from other sources such as the local dam, boreholes, neighbouring taps and obtaining water from work (i.e. 41.2%). below indicates the main sources of water supply. Just over 10% of the residents indicated that they bought water and under 20% highlighted that they conducted water harvesting to secure water.

Table 1. Year and drought severity levels as highlighted by Somkhele residents.

Table 2. Sources of water collection for the household.

Due to the severity of drought and the need for water in households, residents (i.e. women) had to walk far distances to fetch water, which as time consuming. The women interviewed noted that since there was no water, they had to walk between 3 and 5 kilometres a day to collect water for household and other uses. below indicates the number of times water needed to be collected in a week. A majority of residents (i.e. 71.5%) indicated that water needed to be collected every day, whilst other residents needed to collect water every second or third day.

Table 3. How often does water need to be collected.

A women activist from Fuleni, Informant B (personal interview, July 2016) and against mining development in the area indicated the hardships faced by women to collect water. On top of that the water sources were not clean and residents had to take measures to clean the water from any contamination. As the informant noted:

I was going door to door and asking the women what challenges they meet when they is a shortage of water in their place … how long did it take them to go to the river to fetch the water and would they be able to do everything in the home … [Although] the municipal water delivery truck come in a week to their village to supply them … some didn’t get the water since there are so many people in the village. They went to the Umfolozi River to dig for water in the river bed. These residents have to walk that long distance with 25 litre containers to get water at the river. It can take about 3 hours to get the water meaning its 3 hours to and another 3 hours from the river … In Ntutuka [community section] 1 and 2 they travel long distances to fetch dirty water from dams, also used to water livestock. We also heard that they [residents] put cement in it as a water cleaning agent.

We are faced with a drought it’s hard to get water and some community members have to walk 3km distance to get water some have to walk 3 hours to get water. So if you gonna walk 3 km to get 25 litres of water and you get only 50 litres per day coz you can only walk twice per day.

It was therefore clearly evident that the drought conditions in the Somkhele/Fuleni region has become more severe over the years and this has affected resident livelihoods and how they have been able to secure water for everyday needs. Women have been particularly impacted by water shortages and drought conditions since they have been responsible for maintaining the households and also growing and watering crops ( and ).

Figure 2. Somkhele women collecting water from a local source.

(Source: Hargreaves Citation2016).

Mining impacts on water supply and for residents

In addition to climatic changes causing drought in the Somkhele and Fuleni communities, the introduction of mining in the region has worsened the problem of water security for residents. A few informants highlighted that introducing mining to the region was a concern as water resources was already limited due to climate change and mining development did not take into account the already sustainable lifestyle of communities and access to local resources. As informant D (telephonic interview, July 2016) from a public legal institute, a legal firm specialising in environmental law and environmental justice, and representing the Fuleni community to oppose the application made to the Department of Mineral Resources (DMR) for an open cast coal mine noted:

If you go through the [mine] social labour plan where they are talking about the economics of the area. They speak about unemployment and low income levels and don’t consider that fact that most of these people had sustainable lives. Those people they live off the land so obviously the fact that there is no water at the moment is a serious constraint and that speaks to the other mines in the area. Because of the drought and the fact that they [mining] are taking away grazing [land] and damage the rest of the grazing with coal dust … the sustainability of the people is gone … people might not have an income, might not have a job but their community is sustainable they have goats they have chickens they have crops and they have water and that’s the way they live. If you take away all of that and they don’t have a job … it’s a disaster

As informant D further noted regarding the application for mining in the region, and the climatic constrain on already scare water reserve:

The whole application for mining … It shouldn’t have even come out of the starting block because … there is no water for the people. The rivers are dry. The animals are dying and [now] a mine … I think Somkhele takes 250 000 litres of water a day from the Umfolozi river … a day! So if there is no water there … why even [consider mining] … how have we come years down the line, two prospecting licenses granted six years prior and there is no water. I mean it’s surely a no go area … The department [Department of Mineral Resources] should say unfortunately … in these particularly water scarce areas there will be no consideration for mining licenses finished

The impact of mining on water resources and local communities was clearly highlighted by Informant C (personal interview, July 2016) from Fuleni who noted that in addition to climatic changes and increased drought, the mines will proliferate the water insecurity in the area:

We so lucky because just across the river … we have the Somkhele Mine … right now its dry there is no water. We used to get water at Mfolozi River and that river used to run each and every season but now it’s dry … why? We have Somkhele Mine, which is pumping water from the Umfolozi River. While they pumping water they had promised the community that as they come in to mine they will supply the community with water … On one side of the river it’s us as the Fuleni community and the other side it’s the Somkhele community, but we all get water from that river. So if you taking water from that river you are killing Somkhele and Fuleni at the same time, because there are two communities using the same river. So now we used to go attend some [mining consultation] meetings at Somkhele and we tried to tell them that guys as you pulling water from the Umfolozi River you are also affecting us … .So if we say we will allow that mine to come here … it’s obvious the community will be dead already

Others [Somkhele community residents] they say the rain was always there before the mine, so they think there is something done by the mine to control the rain … they [residents] fail to use the water in the river they used before due to there’s a coal dust in.

Way forward for improving water security and supply

Residents noted that both the government and the mining company should be responsible for water provision in the communities, more so for the former. highlights residential recommendations for improving water provision. Most residents noted that government should intervene to assist with water provision (i.e. 59.9%). This was followed by the use for water tanks (i.e. 57.7%) and then provision by the mining company (i.e. 40.5%). However, more residents strongly opposed the provision of water by the mining company (i.e. 13.2%) compared to an intervention by government (i.e. 5%). This could be explained due to division of opinions over the mines since they were said to have supplied water in the communities. As informant F (Personal Interview, July 2017) a youth leader noted, “[The mines supply water just once a week, even once a month or sometimes, if there’s an event or just a crisis … That is why people were divided] … ” Government is also responsible for service provision to citizens and a possible reason why most residents expected government to provide water.

Table 4. Major threats to water supply.

Table 5. Recommendations to improve water supply.

However, both government and the mine did not ensure reliable water supply and therefore did not solve the water insecurity problem for residents. As participants from the local group interview (Personal group interview, July 2017) noted: “Sometimes you get none [water], you wait one week and three months they [government] don’t have it, they come three months, once a week. [Youth Somkhele group interview]”. Informant C [personal interview, July 2016] a community activist fighting against mining in the Fuleni community further noted for industries non-reliability of water for residents:

So their [Somkhele residents] message is that the mine must stop operating and sort all the problems that it caused in the area … They [the mine] have a sign of a water point where people must come and collect water, but they are not doing nothing … So the community is unhappy about that mine. They have been trying to block [mining] … last week they got shot with rubber bullets.

Discussion and conclusion

The impacts of climate change had caused widespread drought in South Africa and particularly in the province of KwaZulu-Natal. This was evidence within the uMkhanyakude District Municipality. All informants in the case site had noted that climate change had caused drought in the region which impacted on water security. The severity of drought was noted by Somkhele residents to have increased over the years becoming more severe for water and food security. Due to the severity of drought conditions, especially since 2015, residents in Somkhele and Fuleni had to source water from various locations such as the Umfolozi River, work, and from other sources such as the local dam, boreholes and neighbouring taps. Due to the severity of drought and the need for water in households, residents, particularly women had to walk between 3 and 5 kilometres to fetch water, which was time consuming. Since most men were away working in urban areas, it was the responsibility of women to grow and water crops. Most residents engaged in farming activities in the household or within the community and therefore water was needed for crops. The results of this research collate with the literature on climate change and drought impacts in KwaZulu-Natal. As Lottering, Mafongoya, and Lottering (Citation2021) note droughts will have severe impacts in the province and there have been uneven effects on poor rural communities and small-scale farmers who base their livelihoods on rain fed agriculture, with women according to Masinga, Maharaj, and Nzima (Citation2021) mostly impacted by climatic changes. As findings reveal for the Somkhele/Fuleni region women need to travel further to secure water sources due to the Umfolozi River being largely dry.

In addition to climatic changes causing drought in the Somkhele and Fuleni communities, the introduction of mining in the region worsened the problem of water security for residents. There was an interplay between climate change, mining impacts and water security in the region. The impact of mining on water resources, already exacerbated the climatic conditions in Fuleni and Somkhele. It is therefore surprising that government has spearheaded mining in the region despite issues with drought and lack of water resources. However, literature revealed that corruption over mining development was an issue in the region. Traditional leaders have become instruments of mining companies (and government) to allow mining developments in rural areas and with benefits received by some traditional leaders. There has been a lack of transparency on how decisions have been made within the Fuleni traditional council, and which decisions have not been in the interest of local residents. The support for mining development within the traditional council was due to corruption and benefits received from mining development. It was also evident that mining was supported by the national DMR government without considering the lack of water resources in the area and impacts brought upon by climate change. These decisions were also taken without consulting with communities and other government departments such as Water Affairs.

Fragmentation between government departments was thus evident on mining developments and approvals, which is a reason why mining is implemented in isolation from consideration over climate change and increased water insecurity. The case study also highlights the consequence of climate change for the future of the mining sector in South Africa, which itself contributes to climate change, particularly in water-constrained national environments such as KwaZulu-Natal. The case also illustrates that ecological harms and resistance to mining (as we have seen from resistance against mining in St Lucia) is inherent to capitalism. At a macro level, neoliberal capitalist mining development contribute to the climate crisis and at the micro community level mining development impact on already insecure local water supplies. The South African government has also spearheaded a macroeconomic development path since the transition to democracy which has enabled high-capital and high energy intensive industries such as mining. This has prioritised wealth production and has not spearheaded viewing (sustainable) development in an integrated and holistic manner. The following recommendations are made to alleviate water insecurity for citizens:

There needs to be better spatial development planning so that development is implemented in an integrated manner that contributes to sustainable development and does not impacts on water security. This will ensure that Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) particularly goal 6 – Clean Water and Sanitation is realised. This will also ensure that SDG 3 – Good Health and Well-being is achieved.

Considering that climate change is ravaging communities and water security, government needs to ensure that further industrial developments implement clean and sustainable technologies that are less reliant on water resources. The link between mining contributing to climate change and impacts on water and food needs to be understood. In turn government must work with existing mining developments to ensure that there are robust plans to phase out and upgrade technologies and ensure that there are innovations related to water and energy, which must be accelerated as a matter of urgency. The South African government must ensure that development decisions made do not contravene the constitutional rights of citizens and impact environmental resources.

At a more micro-level both the mining industry and government must ensure that water is supplied to communities in a consistent and reliable manner so that the burden of water collection is not placed on women who need to walk long distances to collect water. For example, local technologies for water security and stress have been developed. Researchers at Carnegie Mellon University developed a paper book education and filtration tool. Each page of the book provides basic water and sanitation advice and serves as a filter that can be used to purify drinking water and kill bacteria. As opposed to dealing with water pollution, another technology invention is the “Water Seer” which, uses the surrounding environment to extract water from the atmosphere and can generate about 37 litres of water a day (Sprinks Citation2017). Thus, such technology interventions can ensure that time to collect (and purify) water by residents is better spent on farming and maintaining the household. Government is responsible for service provision to communities and the mining industry in turn must take responsible for proliferating and adding to water security for local communities. The importance of inter-sectoral collaborations must be prioritised between mining, the government, and civil society, to achieve water security in face of climate change

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the Somkhele and Fuleni communities for their participation in this study and for allowing the researcher to conduct data collection at the sites. Sincere appreciation is also extended to the community activists and youth leaders for their assistance with interviews and for recommending other informants to interview. Local fieldworkers are also thanked for assisting with conducting community surveys.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- AfricaPLC. 2020. “How Will African Farmers Adjust to Changing Patterns of Precipitation?” McKinsey and Company, 18 May.

- Baumann, T. 2004. “South Africa as a Developing Country: Implications for Socio-Economic Policy in the Second Decade.” Paper presented at ‘Overcoming Underdevelopment in South Africa’s Second Economy’, hosted by the United Nations Development Programme, HSRC and DBSA, South Africa, October 29.

- Carnie, T. 2017. “Mining Poses Threat to iMfolozi Wilderness Zone.” Business Day, 9 March.

- Carnie, T. 2022. “Creecy Beefs Up Zululand Rivers Pollution Probe After Coal Waste Collapse.” Daily Maverick, 22 February.

- Conde, M. 2017. “Resistance to Mining: A Review.” Ecological Economics 132: 80–90.

- Delevingne, L., W. Glazener, L. Grégoir, and K. Henderson. 2020. “Climate Risk and Decarbonization: What Every Mining CEO Needs to Know, McKinsey Sustainability.” Accessed March 16 2022. https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/sustainability/our-insights/climate-risk-and-decarbonization-what-every-mining-ceo-needs-to-know.

- Di Falco, S. 2018. “Adapting to Climate Change in Sub-Saharan Africa.” In Agricultural Adaptation to Climate Change in Africa, edited by C. Berck, P. Berck, and S. Di Falco. Resources of the Future Press: New York.

- Eberhard, A. 2011. “The Future of South African Coal.” Program on Energy and Sustainability Development, Stanford University. Accessed February 21 2016. https://pesd.fsi.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/WP_100_Eberhard_Future_of_South_African_Coal.pdf.

- Ebhuoma, E., F. Donkor, O. Ebhuoma, L. Leonard, and H. Tantoh. 2020. “Subsistence Farmers’ Differential Vulnerability to Drought in Mpumalanga Province, South Africa: Under the Political Ecology Spotlight.” Cogent Social Sciences 6: 1. doi:10.1080/23311886.2020.1792155.

- Grenfell, S., and W. Ellery. 2009. “Hydrology, Sediment Transport Dynamics and Geomorphology of a Variable Flow River: The Mfolozi River, South Africa.” African Journals Online 35 (3). doi:10.4314/wsa.v35i3.76764.

- Hans, B. 2016. “16 000 Homes to be Demolished’ for Proposed Mine – KwaZulu-Natal.” The Mercury, 30 April.

- Hansen, M., and M. Bandile. 2015. “Anti-Extractivist Feminist Politics in KwaZulu-Natal.” Paper Presented at ‘World Association Conference for Political Economy 10th Forum: The Uneven and Crisis-Prone Development of Capitalism’, Johannesburg, June 20.

- Hargreaves, S. 2016. Women Defending Water, Land and Life in Northern KwaZulu-Natal. No (47). Accessed September 2017. Alternative Information and Development Centre. http://aidc.org.za/women-defending-water-land-life-northernkwazulu-natal/.

- Jolly, T. 2015. “Fuleni Mine Speculation.” Zululand Observer, 8 May.

- Jolly, T. 2016. “Fed-Up with Living in Close Proximity to Somkhele Mine, Mpukunyoni Communities Seek Closure of the Mine.” Zululand Observer, 1 July.

- Kruger, C., and M. Nxumalo. 2017. “Historical Rainfall Trends in South Africa: 1921–2015.” Water SA 43: 285–297.

- Kunz, Nadja. 2020. “Towards a Broadened View of Water Security in Mining Regions.” Water Security 11: 100079.

- Leonard, L. 2017. “Governance, Participation and Mining Development.” Politikon 44 (2): 327–345.

- Leonard, Llewellyn. 2019. “Traditional Leadership, Community Participation and Mining Development.” Land Use Policy 86: 290–298.

- Leonard, Llewellyn. 2021. “Ecological Conflicts, Resistance, Leadership and Collective Action for Just Resilience.” Politikon 48 (1): 19–40.

- Lottering, Shenelle, Paramu Mafongoya, and Romano Lottering. 2021. “The Impacts of Drought and the Adaptive Strategies of Small-Scale Farmers in UMsinga, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa.” Journal of Asian and African Studies 56 (2): 267–289.

- Luo, Tianyi. 2014. “Identifying the Global Coal Industry’s Water Risks. World Resources Institute.” 15 April. Accessed 21 February 2022. Online: https://www.wri.org/insights/identifying-global-coal-industrys-water-risks.

- Malherbe, S., and N. Segal. 2001. “Corporate Governance in South Africa.” Policy Dialogue Meeting on Corporate Governance in Developing Countries and Emerging Economies, OECD Development Centre and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, OECD headquarters, April 23–24, 2001.

- Masinga, F., P. Maharaj, and D. Nzima. 2021. “Adapting to Changing Climatic Conditions: Perspectives and Experiences of Women in Rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa.” Development in Practice 31 (8): 1002–1013.

- Mavuso, Zandile. 2014. “MPRDA Concerns Linger as Industry Awaits President’s Verdict.” Mining Weekly, May 23. Accessed 30 October 2014. http://www.miningweekly.com/article/concernsabout-mprda-amendment-bill-linger-as-industry-awaits-presidents-verdict-2014-05-23-1.

- Meißner, S. 2021. “The Impact of Metal Mining on GlobalWater Stress and Regional Carrying Capacities—A GIS-Based Water Impact Assessment.” Resources 10: 120. doi:10.3390/resources10120120.

- MineWeb. 2011. “South African Police Squad Raids Minerals Dept in Corruption Investigation.” Accessed October 30, 2014. http://www.mineweb.co.za/mineweb/content/en/mineweb-politicaleconomy?oid=132453andsn=Detail.

- Mthembu, A., and S. Hlophe. 2020. “Building Resilience to Climate Change in Vulnerable Communities: A Case Study of UMkhanyakude District Municipality.” Town and Regional Planning 77: 42–56.

- Naicker, K., E. Cukrowska, and T. Mccarthy. 2003. “Acid Mine Drainage from Gold Mining Activities in Johannesburg, South Africa and Environs.” Environmental Pollution 122: 29–40.

- Ndlovu, M., A. Clulow, M. Savage, L. Nhamo, J. Magidi, and T. Mabhaudhi. 2021. “An Assessment of the Impacts of Climate Variability and Change in KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa.” Atmosphere 12: 427. doi:10.3390/atmos12040427.

- NEMA (National Environmental Management Act). 1998. “Act 107, Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism, Republic of South Africa.” Accessed March 12, 2016. http://www.kruger2canyons.org/029%20-%20NEMA.pdf.

- Odell, Scott, Anthony Bebbington, and Karen Frey. 2018. “Mining and Climate Change: A Review and Framework for Analysis.” The Extractive Industries and Society 5 (1): 201–214.

- Olalde, M., and A. Matikinca. 2019. “Big Increase in Mine Water Pollution.” Mail and Guardian, 17 May.

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. 2014. “Phase 3 Report on Implementing the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention in South Africa.” Accessed October 24, 2014. http://www.oecd. org/daf/anti-bribery/SouthAfricaPhase3ReportEN.pdf.

- Patrick, H. 2021. “Climate Change and Water Insecurity in Rural UMkhanyakude District Municipality: An Assessment of Coping Strategies for Rural South Africa.” H2Open Journal 4 (1): 29–46.

- Pearce, T., D. Ford, J. Prno, F. Duerden, J. Pittman, M. Beaumier, L. Berrang-Ford. and B. Smit . 2011. “Climate Change and Mining in Canada.” Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change 16: 347–368. doi:10.1007/s11027-010-9269-3.

- Pillay, D. 2007. “The Stunted Growth of South Africa’s Developmental State Discourse.” Africanus 37 (2): 198–215.

- Rebelo, Alanna. 2019. “Part of the Answer to Surviving Climate Change May be South Africa's Wetlands.” News24. 2 February.

- South African Constitution. 1996. Republic of South Africa, Act 108 of 1996. http://www.polity.org.za/pol/acts/

- Simpson, G., J. Badenhorst, J. Graham, B. Marit, and D. Ellen. 2019. “Competition for Land: The Water-Energy-Food Nexus and Coal Mining in Mpumalanga Province, South Africa.” Frontiers in Environmental Science 7. doi:10.3389/fenvs.2019.00086.

- Sprinks, R. 2017. “Could These Five Innovations Help Solve the Global Water Crisis?” The Guardian, 13 February.

- Umfolozi Integrated Development Plan. 2020/2021. “Period 2017–2022.” Accessed 20 February 2022. Online: https://www.cogta.gov.za/cgta_2016/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/2020-21-Final-IDP-_June-2020.pdf.

- uMkhanyakude District Muncipality. 2022. Online: http://www.ukdm.gov.za/.

- University of California – Santa Barbara. 2021. “Cleaning up Mining Pollution in Rivers.” ScienceDaily, 8 June. www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2021/06/210608154411.htm.

- Walter, M., and L. Urkidi. 2017. “Community Mining Consultations in Latin America (2002–2012): The Contested Emergence of a Hybrid Institution for Participation.” GeoForum 84: 265–279.

- World Meteorological Organization. 2020. State of the Climate in Africa 2019. Accessed on 14 September 2021. https://library.wmo.int/doc_num.php?explnum_id=10421.

- Youens, K. 2016. “The Fuleni vs Ibutho Coal Matter: A legal Perspective.” 13 September. https://youensattorneys.co.za/thefuleni-vs-ibutho-coal-matter-a-legal-perspective/

- Youens, K. 2022. “Coal Mining Onslaught on Hluhluwe-iMfolozi Park is Tantamount to Ecocide.” Daily Maverick, 30 June.

- Ziervogel, G., M. New, E. van Garderen, G. Midgley, A. Taylor, R. Hamann, S. Stuart-Hill, J. Myers, and M. Warburton. 2014. “The Impact of Climate Change and Adaptation in South Africa.” Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 5 (5): 605–620.