ABSTRACT

Catastrophic extreme weather events are destructive, costly, and bring about significant harm and distress. As a consequence of a warming world, extreme weather is only expected to increase in intensity. Unravelling the ways that frontline communities, such as those in the Cook Islands, are experiencing, preparing for, responding to, and recovering from, extreme events over time is vital to document, learn from, and share widely. This paper, drawing from 10 interviews with local Cook Islanders from both urban and remote settings, explores people’s perspectives and experiences of, as well as responses to, extreme weather events, with a focus on droughts and cyclones. We found that the immediate devastation of cyclones and the chronic devastation of droughts has impacted participants in diverse ways, most of which take an emotional toll and affect people’s abilities to meet household needs. These participant experiences with extreme weather events and the subsequent lessons that have transpired have led to the development of significant local knowledge and traditional coping strategies which enable anticipation, preparation, and adaptation. We highlight the ways that participants draw on cosmology, worldviews, and community resources for different courses of action in response to extreme weather. Tacit knowledge and endogenous spiritual and community resources offer Cook Islanders agency, hope and resilience in the face of climate change into the future.

Introduction

Estimates show that over the last 20 years, there have been 7348 major recorded disaster events. Collectively, they have claimed 1.23 million lives, affected 4.2 billion people (which for many was more than once) and resulted in US$2.97 trillion in global economic losses, which is likely an underestimation (CRED & UNDRR Citation2020). This is a sharp rise from the previous twenty years; a difference that can be explained by increases in climate-related disasters such as extreme weather events (i.e. storms, floods, and droughts) which are dominating the disaster landscape in the twenty-first century (CRED & UNDRR Citation2020). It is a well-accepted eventuality that climate change has, with changes observed since around 1950, and will continue to increase the frequency and/or severity of extreme weather events globally (IPCC Citation2013; Citation2014).

Small Island Developing States (SIDS) such as those in the Pacific region are highly impacted by these events, despite contributing little to greenhouse gas emissions (Barnett and Campbell Citation2010; IPCC Citation2014). Although impacts vary geographically, the most destructive events in the Pacific region are floods, droughts and tropical cyclones which entail considerable costs and damage to major socio-economic sectors and affect the quality of life of many (United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs Citation2012; Kuleshov et al. Citation2014). There has been extensive research into the impacts of climate change on biophysical systems and economic sectors in the Pacific, but less focus on “how island communities experience climate change, identify relevant adaptation options, and mobilise their capacity to deal with impacts, including traditional knowledge” (Granderson Citation2017, 545). Additionally, the tacit knowledge that has developed as a consequence of experiences and learnings over many years is critically important to document and share with others, as Bridges and Mcclatchey (Citation2009, 140) have argued: “Over many generations these atoll cultures have survived major, unpredictable and locally devastating changes that are of the same magnitude as those expected from climate changes”. Place-based understandings of local impacts and vulnerabilities, as well as a deep appreciation for the diverse ways local people prepare, respond and recover are critical for effective adaptation and disaster risk management (Barnett and Campbell Citation2010; Lata and Nunn Citation2012), especially in the Pacific (McNamara and Prasad Citation2014; McMillen et al. Citation2014; McNamara et al. Citation2020).

As such, this study is guided by the following overarching research question: how do locals in the Cook Islands experience and respond to extreme weather events? The findings will build on the growing body of work in the region by outlining place-based, personal accounts of loss in the face of cyclones and drought in the Cook Islands, while also unravelling household-level and community-level strategies as well as Indigenous and local knowledge (ILK)Footnote1 used to help prepare, cope, adapt, respond and recover. Focusing on the Cook Islands is critical as they are mostly highly-exposed atolls and there are few studies exploring local people’s perspectives, experiences and responses to climate change and extreme weather events in this nation (see exceptions Taylor Citation1999; Rubow Citation2009; Rongo and Dyer Citation2014; Rubow Citation2018; de Scally Citation2019). We explore diverse place-based experiences and subjective personal accounts of loss, preparedness, recovery, and adaptation to identify the lessons that may transpire for future efforts.

Background and literature review

Impacts of extreme weather and climate change in the Pacific Islands and Cook Islands

Floods, tropical cyclones, and droughts – the latter two of which are the focus of this study – are the most destructive and severe weather/climate extreme events affecting countries in the Western Pacific where the Cook Islands are located (Kuleshov et al. Citation2014). Although the impact of climate and weather extremes varies between countries, in general, such events can result in loss of life as well as economic and social hardship through decreased agricultural productivity, destruction of infrastructure (e.g. electrical, water and telephone connections as well buildings, schools and homes) and slowed economic development (Kuleshov et al. Citation2014). Cyclone-related economic losses (e.g. losses to physical assets and production losses) are extremely high in the Pacific region and in the Cook Islands where the highly exposed coastlines harbour the majority of the population, infrastructure, and economically important sectors (Cook Islands Meteorological Service et al. Citation2011; Rubow Citation2009). Droughts have varying degrees of impact, although, in general, lead to devastating water and food insecurity, fires and, in some Pacific countries, electricity shortages due to limited water for hydroelectricity (Kuleshov et al. Citation2014).

Extreme weather and climate change can result in the loss of cultural heritage and indigenous knowledge, vital ecosystem services, sense of place and identity, social cohesion, and health and wellbeing (McNamara et al. Citation2020; Cámara-Leret et al. Citation2019). In terms of the latter, the mental health impacts of extreme weather events are increasingly recognised, with existing studies from the Pacific Islands region having documented feelings of loss, grief, sadness, anger and stress as a result of acute weather-related disasters (Charlson, Diminic, and Whiteford Citation2015; Hunter et al. Citation2015; Sattler Citation2017; Gibson et al. Citation2020). "Creeping changes" can also erode livelihood options and threaten social processes, resulting in feelings of loss, fear, and uncertainty (Asugeni et al. Citation2015). Anticipated threats and losses can have severe mental health and wellbeing impacts, including through “pre-traumatic stress disorder” (van Susteren and Al-Delaimy Citation2020), which can impair daily functioning as seen in Tuvalu (Gibson et al. Citation2020). Chronic and repeated disasters can also heighten risks of mental health consequences (Morrissey and Reser Citation2007; Padhy et al. Citation2015).

This brief section outlining the impacts of extreme weather events and climate change in the Pacific demonstrates the importance of collecting stories of tangible but also intangible losses and damages, which will be further explored in the context of the Cook Islands in this study.

The role of cultural heritage and traditional knowledge in coping with and responding to extreme weather and climate change

Although not a panacea (Kelman and West Citation2009), the diverse, multi-faceted practices and knowledge of Pacific Islanders in the face of unpredictability and variability has increasingly been recognised and documented as crucial for adaptive capacity and resilience in the face of climate change and extreme weather (McMillen et al. Citation2014; Granderson Citation2017; Dacks et al. Citation2019; Nakamura and Kanemasu Citation2020). There are multiple facets of ILK in the Pacific region that have proved critical, including expertise around local change in terms of weather, life history cycles and ecological processes (Lefale Citation2010; McMillen et al. Citation2014). In the Cook Islands, for example, studies have documented how local observations, such as changes to weather patterns, fruiting seasons as well as local flora and fauna, are important for understanding climate variability and its impact at the local scale (Rongo and Dyer Citation2014; de Scally Citation2019). Observations over generations can also form tools such as seasonal calendars and/or biocultural indicators that guide expectations of weather, phenological characteristics and contribute to the timing of resource management and/or ritual events (Lefale Citation2010; Johnston Citation2015; Nakamura and Kanemasu Citation2020), and can act as a resource for adapting to changing conditions (Leonard et al. Citation2013). de Scally (Citation2019) identified a series of biocultural indicators (e.g. bird migration, presence of specific species and wind change, among others) that act as early warning signs for climate-related hazards in the Cook Islands, albeit several locals were sceptical of their relevance today.

ILK also informs specific strategies for managing climatic hazards and resource variability as well as maintaining ecological integrity in the face of disturbance and extremes. This includes through food preservation, diversifying crops, cultivating resilient crops, building resilient homes and communal resource pooling (Mercer et al. Citation2007; Bridges and Mcclatchey Citation2009; McNamara and Prasad Citation2014; see Table 8 in de Scally Citation2019). Other observed examples of ILK reflect resource management more broadly in the Pacific, including customary land tenure rules, harvesting practices (e.g. off-limit conservation zones or adaptive agricultural practices) and communal sharing of resources, which help people deal with resource variability from climate change and extreme weather (McMillen et al. Citation2014; Granderson Citation2017). de Scally (Citation2019), for example, described the revival of Ra-ui in the Cook Islands – a traditional resource conservation system whereby access to a particular resource or area is restricted for a specific amount of time.

ILK is, therefore, critical for adaptation and disaster risk reduction in many ways, including for establishing baselines and understanding local impacts and vulnerability (Kelman, Mercer, and West Citation2009), and for anticipating and preparing for risks (Acharya and Prakash Citation2019). Reviving and building on ILK and local adaptation or risk management strategies in the Cook Islands can improve the appropriateness, effectiveness and sustainability of adaptation and disaster risk reduction efforts, while also empowering communities and enhancing the organisation of activities (Hiwasaki, Emmanuel Luna, and Marçal Citation2015; Naess Citation2013). Despite the criticality of ILK and local strategies and practices, development pressures (e.g. Westernised ways of living), out-migration, religious influence and uncertainty over future usefulness are contributing to the loss of ILK or its lack of perceived relevancy for climate change resilience in the Cook Islands (de Scally Citation2019) and the Pacific more generally (Campbell Citation2006). There is a critical need to identify, document and share tacit knowledge for appropriate, effective, and sustainable adaptation and disaster risk management in the Pacific (Barnett and Campbell Citation2010; Lata and Nunn Citation2012; McNamara and Prasad Citation2014; McMillen et al. Citation2014; McNamara et al. Citation2020).

The role of spiritual and community resources in coping with and responding to extreme weather and climate change

Due to compatibilities with Western science, the above facets of ILK have been the primary focus in discussions on climate change to date (Granderson Citation2017). Attention to other facets of ILK such as cultural beliefs, governance structures, and kinship and other networks are also critical – yet often overlooked – as they can guide self-reliance, agency, collective action, and innovation (Granderson Citation2017). ILK is embedded in and reinforces traditional governance and social structures, including local leadership, kinship networks, group identity, reciprocity and social obligations; aspects that are proving critical for adaptation and resilience in the Pacific (Chishakwe, Murray, and Chambwera Citation2012; McMillen et al. Citation2014; Granderson Citation2017; Perkins & Kraus, 2018). Social networks and institutions can mitigate impacts (e.g. through reciprocal exchange), encourage self-organisation and facilitate social learning, which are all factors contributing to resilience (McMillen et al. Citation2014; Granderson Citation2017). Some studies in the Pacific (see Latai-Niusulu, Binns, and Nel Citation2020) have found that social cohesion is reinforced and strengthened during times of stress as people support one another, facilitating responses to disasters and climate change. These social networks can expand within and across islands and nations, promoting intra-island, inter-island as well as international (e.g. remittances) resource redistribution and cooperation (Lauer et al. Citation2013; Granderson Citation2017).

There is also growing scholarship on the influence of distinct cosmologies and worldviews on perceptions of climate change, its risks, and motivations to respond in the Pacific region. Religious faith has been considered both a key impediment to and enabler of environmental engagement and adaptation in the Pacific context (see Rudiak-Gould Citation2009; Mortreux and Barnett Citation2009; de Scally Citation2019; Kempf Citation2017; Nunn Citation2017; Fair Citation2018; Rubow Citation2009). In terms of the latter, religious ideas and narratives can act as springboards for action, encouraging disaster preparedness and environmental stewardship through non-economic and non-scientific motives (Rudiak-Gould Citation2009; Nunn Citation2017; Fair Citation2018). Biblical scriptures can also be used to make climate change communication and advocacy locally meaningful and morally resonant (Fair Citation2018), while religious organisations can also play a critical role in building resilience (Thornton, Sakai, and Hassall Citation2012) and climate advocacy due to their significant financial, political, and institutional power (Dasgupta and Ramanathan Citation2014; Nunn et al. Citation2016). Importantly, scientific, religious and ILK are not necessarily irreconcilable or competing and can be entangled or held in balance to create a diversity of narratives and courses of action in response to climate change and extreme weather (Rubow Citation2009; Rubow and Bird Citation2016; Fair Citation2018). In the Cook Islands context, Rubow (Citation2009, Citation2018) challenges other studies (e.g. Taylor Citation1999) who generalise and simplify religious understandings as contradictory to scientific explanations and impediments to disaster recovery by highlighting the multiplicity and plurality in interpretations of religious ideas, ways of believing and attitudes towards the church and Christianity. This study will share stories on the tacit ILK related to natural resource management and environmental observations, as well as the critical community and spiritual resources that contribute to resilience and motivations to act.

Method and study site

Ten structured interviews with 11 participants were conducted in October and November 2020 to collect primary data for this study. These interviews were undertaken by staff from the Cook Islands National Council for Women, based in the capital of Avarua on the island of Rarotonga. Given that we wanted to ensure that the voices and perspectives of Cook Islanders in the outer islands – Pa Enua – were included, it was not always possible to undertake a verbal, in-person interview (due to phone connections and cost) and so the structured interview schedule was sent to the participants to complete. Nonetheless, this study retained its qualitative approach with rich qualitative data transpiring. We acknowledge that our findings are based on a small sample size and are not representative of the entire country, albeit this enabled us to obtain and share the detailed and nuanced place-based storylines of a few individuals. This small sample size does, however, present several limitations, including constrained diversity in age groupings of participants and geographical reach across the country. It would be of value for future studies to explore the age differences of participants (most notably the younger generation) and geographical differences (most notably between the Southern and Northern group of islands). It would also be of value for future studies to further investigate how participants group certain events (i.e. whether flooding or storm surges are perceived as separate events or impacts of a cyclone) and correlate this with participants’ knowledge, life experiences, and geographical location, among other factors.

The Cook Islands National Council for Women provided the critical role in selecting participants based on their networks. All interview transcripts/written responses were analysed using NVivo, allowing the social data to be coded into prominent “themes” (Bengtsson Citation2016). All participants gave informed consent to participate and the University of Queensland (approval no. 2020000640) provided ethical approval for the study.

Four women and seven men were involved in this study. All participants live in the Southern group of islands, except for one from the Northern rural island of Penrhyn. Participants ranged in age from 43 to 56 years old, with an average age of 55 years old. Nearly all participants identified with various Christian denominations and were involved in various community activities to varying degrees, including village life and church. Most participants relied on their gardens, livestock, poultry, and marine resources (i.e. fishing) to maintain their livelihoods, along with varying income streams such as owning a small business, working for the government or non-government organisation, selling flowers, or undertaking contract work. One participant was retired. An overview of all participants, including details of where they were born and live, family, religion, and education/training and knowledge/skills, is provided in .

Table 1. Overview of participants.

The structured interview guide consisted of four key sections. The first section focussed on participant backgrounds with questions on gender and age, where they were born, their family, education and training, and local Indigenous knowledge held. The second section focused on their everyday livelihoods and lives with questions focussed on aspects such as livelihoods, food and water sources, and access to agricultural and fishing grounds. We also asked participants to walk us through a normal day, including their key responsibilities at home and whether these responsibilities have changed over time. The third and fourth section ascertained stories of disaster events and/or climatic change, including sudden/onset events and/or more gradual climate changes over the last 20 years. Experiences of loss and damage following these events/changes and coping/response strategies were detailed by participants.

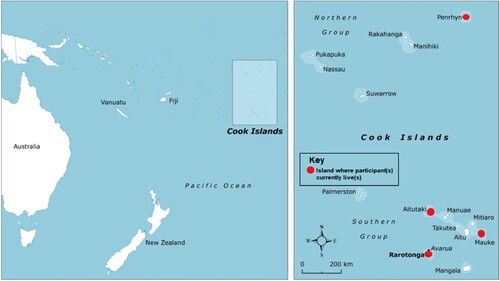

Although spread over an exclusive economic zone of around two million square kilometres in the Southern Pacific Ocean, the Cook Islands – a Polynesian island nation – has a total of 15 islands that covers less than 240km2 (GEF et al. Citation2009). The 15 islands can be geographically, and to some extent culturally, divided into two main groups: the Southern group (with nine islands) and the Northern group (with six islands; see ) (GEF et al. Citation2009). In 2016, the total country population was 17,434 (including residents and tourists), with Rarotonga, as the centre of Government and commerce, remaining the most populous island with 75% of the population (Cook Islands Statistics Office Citation2018). The remaining islands in the Southern group (i.e. excluding Rarotonga) account for 19% of the population while the Northern group only accounts for 6% (Cook Islands Statistics Office Citation2018). Given the large distances between islands, some of these smaller populations are extremely remote, where efficient transportation and communication systems are difficult to develop (Cook Islands Statistics Office Citation2018). Remoteness also poses logistical issues for post-disaster relief and response efforts (World Bank Citation2015).

Figure 1. Location of the Cook Islands in relation to Australia and New Zealand (left) and the country’s islands (right) indicating where participants live (black circles) (Adapted from Blacka, Flocard, and Parakoti Citation2013).

The accommodation and food service industry employs the largest number of Cook Islanders (20.9%), closely followed by wholesale and retail trade (15.8%) and public administration (15%) (Cook Islands Statistics Office Citation2018). Approximately 24.4% of households in the Cook Islands operate land for agricultural purposes with 49% growing fruit and crop trees (e.g. bananas, taro, pawpaw, maniota), 43.7% growing flowers, 35.6% growing vegetables and 55% collecting coconuts (Cook Islands Statistics Office Citation2018). The largest number of households in the Cook Islands (83.4%), and especially the population in Rarotonga (90.8%), access water through the public water main, while the second most common source is water tanks (63% of all households) (Cook Islands Statistics Office Citation2018). Water tanks remain the main source of water supply in outer islands – with 98.5% of households in the Northern islands and 87.2% in the Southern Islands (Cook Islands Statistics Office Citation2018). All water sources in the Cook Islands are vulnerable to drought.

There is a tropical mild maritime climate in the Cook Islands characterised by a pronounced hot wet season from November to April – in which two-thirds of the annual rain falls – and a dry season from May to October (which tends to be cooler for the Southern group) (GEF et al. Citation2009; Cook Islands Meteorological Service et al. Citation2011). During El Niño, the Southern Cook Islands experience significant decreases in annual rainfall – sometimes by up to 60% – while the Northern group’s annual rainfall can increase by over 200%; a pattern that then reverses during La Niña (GEF et al. Citation2009). The cyclone season is highly linked with ENSO and occurs between November and April. In the 41-year period between 1969 and 2010, there were 47 tropical cyclones passing within 400 km of Rarotonga (Cook Islands Meteorological Service et al. Citation2011). Although there is an average of just over one cyclone per season, this varies annually with some seasons having none and other seasons having up to six (Cook Islands Meteorological Service et al. Citation2011). By the end of the century, projections suggest decreased frequency but increased intensity of tropical cyclones (Cook Islands Meteorological Service et al. Citation2011).

The impacts, as the disasters unfold

As participants shared their experiences of extreme weather events and unfolding disasters, two key themes emerged to illustrate local experience and impacts. The first is that droughts and cyclones were the most prominent events. Droughts are sometimes broken by heavy rain or cyclones, highlighting the extremes experienced in the tropical Cook Islands. The second key theme involved discussions around how cyclones bring immediate devastation, while droughts are slow and insidious, yet also take a heavy toll of people: “cyclones just come and go, whereas the drought takes time for the damage to be felt … drought is continuous” (Participant #9, 2020). Almost all participants explained how the impact of drought was the most significant of all extreme weather experienced:

Most severe in terms of impact on us would be the 8 months drought. (Participant #3, 2020)

The changes of rainfall – droughts – are the worst disaster events that impacted every household and the community overall. (Participant #8, 2020)

Drought have been the most damaging to my family. (Participant #1, 2020)

Being scared, being thirsty at night because no coconut to drink because all finished and water from water tanks in our village are salty. (Participant #4, 2020)

Drought – no water to house. Have to go to families on low lying areas for bathing, washing the clothes. Loss of taro and loss of goats and pigs. As well as selling these, these are our staple food. So, there was a loss of income. (Participant #7, 2020)

It affected our plantations, moreso our livelihood, not only us, but everyone else. (Participant #9, 2020)

All the food crops were damaged, breadfruit trees, banana trees on the ground, cannot plant around our house because before the cyclone we had yam, tarua, and kumara near our house. Other fruit trees were also damaged. (Participant #4, 2020)

For about six months we had pretty much no fruit, bananas and pawpaws having to start over again and few vegetables. (Participant #3, 2020)

The loss of crops in the community, the cyclone had ruined all the vegetable plantations, coconuts to feed animals and humans. (Participant #6, 2020)

During the drought, it was hard not to bring the right food to your family, nerve wrecking and stressful, you just wonder what is happening, sometimes you turn your anger to your family, which is not fair to them, but these are some of the things that I can recall. Having no coconuts to feed the pigs was also harder to bear. (Participant #5, 2020)

When there is drought, we always get unhappy and tired. There is no grass for the goats and no coconuts for the pigs and no water for our house. We have to buy pig food from the shop and for the goats have to cut leaf branches from the hills … We have less animals now, as we did know of the hardship we encounter. We did not want to go through seeing our animals die because of hunger and thirst. I believe my neighbours have the same grievances as we had. (Participant #7, 2020)

The feelings of loss, people were stressed and scared. (Participant #9, 2020)

People were stressed and scared especially for the cyclone as this is a first for everyone. (Participant #9, 2020)

I can remember lying in bed that night asleep and waking up to feeling of the walls moving in and then out and hearing the rain just outside our bedroom door on the floor where the roof had come off our home. I have never forgotten that – so your emotions. The worry that the rest of the roof was going to come off, the wind was so loud, and we were in complete darkness without power, it was scary. (Participant #6, 2020)

… very scary. You feel concerned for those living by the seaside for all their life and their ancestors and nothing like this has ever happened. (Participant #10, 2020)

… the effect after the other, I think makes the struggle harder. (Participant #5, 2020)

… the fact we were dealing with one cyclone after the other, was extremely stressful. (Participant #10, 2020)

The whole island was weary, it just felt like we were all exhausted for most of that year. (Participant #3, 2020)

Interestingly, however, in alignment with Rubow (Citation2018), participants demonstrated diversity and dynamism in local responses to cyclones, as some also expressed feelings of excitement and thrill:

The first cyclone was exciting, seeing that awesome power is thrilling and not unexpected … we’re used to cyclones, so no one panics as a general rule, we prepare and expect to clean up afterwards. Then the second warning came, and we were all surprised … Then the third came and we were amazed, but not so thrilled. That one hit the school badly and all the thrill was gone. After each event many people go sightseeing around the island to see what damage has been done, sharing photos and video footage taken at risk of high seas etc and helping where needed. I think by the third cyclone there weren’t so many nosey-ing around anymore. (Participant #3, 2020)

Using tacit knowledge to anticipate, prepare for and adapt to extreme weather

Local knowledge systems shape how people anticipate, prepare for, and respond to disasters and the impacts of climate change in the present and future. Numerous examples of anticipatory actions have been trialled and learned through past experiences of disasters. As one participant eloquently put it: “ … our philosophy for living and our values have only been strengthened by hardships and been lessons that we can share with others to build resilience” (Participant #3, 2020). This tacit knowledge is a significant motivator for local people to act in times of uncertainty (Aksa Citation2020).

This was particularly prominent for cyclone preparation. The importance of preparedness was clear: “preparedness is the key to resolve all of these [losses and damages] from happening” (Participant #8, 2020). There are several key examples of the anticipatory tacit knowledge shared by participants. First, one participant noted that local people in Mauke can anticipate damage from big waves during cyclones:

… the people knows when there will be big waves by which direction the wind is coming from and which area will be affected, everyone will give a sign of relief if it is not North/West to West, because if it is this, then it will affect my village, if not it will only be those places not lived by people. (Participant #4, 2020)

Preparation strategies were mostly related to protecting homes, as a number of participants highlighted:

As soon as a hurricane warning was announced on the radio after this, no matter how small, immediately the roof was tied down and left on until the end of the hurricane season. (Participant #6, 2020)

I do have ropes for my house in readiness, should there be a warning, I have someone there, to do it if I am not there. (Participant #4, 2020)

The importance of accumulating critical resources prior to the cyclone season was also shared (see also de Scally Citation2019): “At the start of cyclone season our family goes straight into preparation mode” (Participant #10, 2020). This includes:

… stocking up on batteries for the radio. (Participant #10, 2020)

… water, batteries, torches, lantern … a generator. (Participant #6, 2020)

… essential foodstuffs. (Participant #10, 2020)

… bottled and dried foodstuffs and a heap of coconuts. (Participant #3, 2020)

… harvest what you could, preserve and freeze. (Participant #2, 2020)

As outlined in the above section, droughts are longer, more insidious events, making it harder for people to prepare for them too far in advance. Participants did however indicate how they would do the best they could to be prepared for the long haul of drought conditions by purchasing water tanks (Participants #3 and #7, 2020), rationing water in the household and cutting back on things like watering gardens (Participant #3, 2020). These illustrate critical household-level strategies for adapting to changing conditions. One participant (Participant #8, 2020) also discussed the implementation of usage restrictions on community water storages, highlighting the important collective action and cooperation required to maintain communal water supplies (Granderson Citation2017).

Several participants also highlighted how, using their knowledge and observations on local environmental conditions and processes, they were adapting to the drier conditions of the drought (see also de Scally Citation2019). For some, this involved focusing on local crops: “During the drought, we figured out that there was no point in trying to grow some common NZ crops, better to stick with those adapted to our conditions” (Participant #3, 2020). This specifically included four different greens, native cabbage, tomatoes, beans and capsicums, the latter of which has adapted to saltier and drier conditions over four generations. For others, it involved planting in different areas and in specific soils during drier periods: “Plant the makatea (coral/stoney) land during drought season, makatea is cooler, plenty shade from trees and soil moist, good for root crops, bananas and also plant the lowest area of the swamp” (Participant #5, 2020). Another participant highlighted how: “bananas are doing well in mulch pits, pawpaw loves these limey soils” (Participant #3, 2020).

As found in the literature (McMillen et al. Citation2014; Granderson Citation2017; de Scally Citation2019), several participants also highlighted the importance of traditional knowledge and resource management strategies for dealing with resource variability:

I still believe that following our ‘ui tūpuna’s teaching [literal translation of “ask the ancestor”, denoting the importance of calling on ancestral wisdom] will help in these times of struggles. Always put something in the ground just in case … for the ecosystem to recover our tūpuna – ancestors – always put a raui to let that area repopulate every living thing in that area, whether in the sea or land. (Participant #5, 2020)

Several participants also shared that they are “sea people” and while the future may necessitate moving away from the coastline, this will not be immediately necessary. There is a drive for self-sufficiency and becoming more resilient to the impacts of climate change by accumulating greater water capacity, growing Indigenous crops, and working with nature (Participant #3, 2020).

Drawing upon spiritual and community resources to respond and recover from extreme weather

In line with Fair (Citation2018), the heterogeneity of religious understandings of, and responses to, climate change emerged amongst participants. First, there were a few references to the upmost trust and security placed in “God’s will”, which although provided a sense of stoicism, were also tied to statements of complacency or passivity in responding to climate change (i.e. accepting whatever comes) (see also de Scally Citation2019). Participants shared the following: “And, if I must lose my lives because of these predicted disasters, this is God’s work and nothing that I can stop it from happening” (Participant #8, 2020); “Leave everything in the hands [of] God, if it’s his will, let it be” (Participant #4, 2020).

Alternatively, drawing on the same notion of “God’s will”, others articulated eco-theological perspectives whereby faith acted as a springboard for action, especially in terms of being environmental stewards. One participant expressed:

For us, both our faith in God comes first, seeking to do God’s will, to live as good stewards of what we have been given. To be agents of positive change … People and environment are inseparable; together they make up God’s creation … Consider “te Pito Enua” (the umbilical cord between us and the land); people and environment being so interconnected that to sever one is to sever the other. (Participant #3, 2020)

The same participant then further articulated this view in the context of extreme weather, and in doing so, illustrated the critical entanglement between religious and traditional knowledge. ILK and local coping strategies, especially in terms of preparation methods, were crucial for responding to religious revelations. For example, notions of “creation care” (Van Dyke et al. Citation1996; Björnberg and Karlsson Citation2022) motivated participants to employ self-sufficient local strategies to prepare and rebuild from extreme events rather than waiting for external help (see also Fair Citation2018):

Creation Care: learning to live in harmony with nature rather than fight it has been valuable for developing resilience, for example after cyclones we can rebuild gardens, we don’t have to wait for grants of seeds, fertilisers, sprays etc … We’re not really worried about the future, we’ve done what we can to prepare, we let others know what might be helpful and encourage good stewardship so that future generations can enjoy what we have, for example grandchildren can get to see live coral and coconut crabs. (Participant #3, 2020)

And taking Jesus’ example in Luke 22:26, a ruler is first and foremost, a servant. Doesn’t it make sense that a good ruler looks after what he rules over … And what does the Bible say about providing for the future (sustainability)? Proverbs 13:22 “A good man leaves an inheritance to his children’s children”. Possessions and money won’t sustain future generations for long, but a good example and a healthy environment will. (Participant #3, 2020)

God created an incredible environment and then made man who was given rule over creation (Genesis 1:28). Unfortunately, that verse has caused some to think they have the right to do whatever they want … But consider Luke 12:48 “ … to whom much is given, shall much be required” Proverbs 12:10 “ … A righteous man looks after his animals … ” (Participant #3, 2020)

These deep spiritual resources are also intimately connected to the cultural community and kinship resources that are important in times of need and place Cook Islanders in a strong position in the face of future climatic change. All participants shared their experiences of collective efforts and the community banding together during disasters:

Prep and clean up after cyclones are always a community event. (Participant #3, 2020)

This was an event that affected the whole of the island … so we all had to pull together, work together. (Participant #6, 2020)

The best way to cope is for the communities to come together, work together and listen to elders. (Participant #5, 2020)

… family is important to us, we don’t worry about too much money, we just have enough to live on, as a family unit we all help each other out, this is the way of our people. (Participant #1, 2020)

As has been evident during these COVID times, people share, no one is hungry. (Participant #3, 2020)

My wife even had to ask her sister who lives on another island Mangaia to send us taro by boat where we received 5 sacks [and] we peeled and stored in the freezers to last us for a few months. (Participant #5, 2020)

For some, these kinship networks expanded internationally, with one participant having a relative in New Zealand who sent timber and iron roofing for rebuilding a house damaged by a cyclone. These kinds of kinship and community networks and efforts are critical as several participants noted that the “Recovery Effort Assistance was slow in coming to the assistance of our people” (Participant #9, 2020); an issue that seems to be rife in the Pacific context (see Nakamura and Kanemasu Citation2020). As similarly observed in other studies focused on the Pacific (see Granderson Citation2017; Nakamura and Kanemasu Citation2020), these processes of intra-island and international exchange and resource redistribution highlight the importance of social and kinship networks for buffering disturbance and speeding up recovery, and thus enhancing resilience (Campbell Citation2009; Lauer et al. Citation2013).

Although cyclones and droughts result in extensive losses, one participant also shared how the hardship of extreme weather events may result in the gain of strengthened community ties:

I believe that Cook Islanders are a people that come together to help each other more so during times of distress and hardship, we all know each other on the island … I do believe that in times like this it brings a community together – we were borrowing or lending things like wheelbarrows, chain saws, bush knives and sharing food. (Participant #6, 2020)

These findings clearly illustrate how cultural support networks, group identity and reciprocity enable but also sustain social resilience to buffer and reduce the impacts of extreme weather events (Perkins and Kraus 2018).

Concluding remarks

This study set out to document and explore how Cook Islanders experience and respond to extreme weather events. The nuanced storylines and observations detailed in this study support, refine, and contextualise existing studies from the Cook Islands, Pacific region and across the globe. For example, we found that participants experienced a range of impacts from cyclones and droughts, which have affected both tangible and intangible resources. It would be of benefit for future studies to explore the more acute differences in impacts experienced by those in the more elevated Southern Group islands compared with the lower-lying Northern Group islands. Understanding these differences will be critical in planning future climate change adaptation across the country. Participants also importantly shared the emotional impacts of slow-onset (e.g. tiredness and anger) and sudden-onset (e.g. stress and fear) events which, as found in other studies, stem largely from a loss of specific resources, decreased ability to meet household needs and anticipated threats.

We found that Cook Islanders have had extensive experiences with extreme weather events and have used and nurtured critical ILK, worldviews, capacities, and resources to help anticipate, cope, prepare, respond, and recover. The nuanced storylines verify and contextualise important strategies for disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation that have been documented elsewhere, including the inter- and intra- island sharing of resources (e.g. construction material, foods, fertile land) which mitigates differences in climate challenges (e.g. Campbell Citation2009; Lauer et al. Citation2013) and place-based agricultural strategies for managing resource availability and climate hazards (e.g. use of specific crops and planting in different soils). Similarly, hybrid and dual-pronged approaches (e.g. in terms of cyclone preparation, early warning systems and dealing with natural resource variability) were highlighted, outlining how a combination of knowledges can be leveraged to maximise capacities to cope with extreme weather at a local scale. Importantly, the stories and observations verify and support other studies in the potential for biblical bases for environmental stewardship and in demonstrating how different knowledge systems are not always competing or irreconcilable (e.g. Rubow Citation2009; Rongo and Dyer Citation2014; de Scally Citation2019; Rubow and Bird Citation2016). The documentation of these place-based and high-resolution observations and adaptations are important in places like the Cook Islands where local scale data is often difficult to find and where integration of local knowledge into climate change policy needs to be strengthened (de Scally Citation2019). It would be valuable for future studies to explore how the younger generation engage with ILK, how and if it is being transferred between generations, and the extent to which traditional response strategies are being passed down to the younger generations. Ultimately, it is important to revive and strengthen local knowledge’s role in adaptation and risk reduction as these resources provide agency and hope into the future. As one participant reminded us, the “[r]unning of these disasters should be kept on Island rather than from outside” (Participant #2, 2020).

Availability of data and material

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available due to them containing information that would compromise research participant confidentiality and anonymity.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the participants for their openness to share their stories and perspectives and we are very grateful for the time they gave us in doing so. We also wish to thank the staff at the Cook Islands National Council for Women who were instrumental in facilitating data collection for this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s), despite the second and third authors being in a married relationship.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Although there has been some debate around the terms used to refer to this knowledge, this is out of the scope of this study. By ILK, we refer to the knowledge and know-how that has been accumulated across generations to guide societies in their diverse interactions with their surrounding environment (Nakashima et al. Citation2012). This knowledge is dynamic and adapts to new conditions (Gómez-Baggethun, Corbera, and Reyes-García Citation2013).

2 The Arapo, meaning nights of the moon, refers to the traditional calendar in the Cook Islands and is used to indicate best timings for activities such as fishing, planting, and harvesting (Ama Citation2003; de Scally Citation2019).

References

- Acharya, Amitangshu, and Anjal Prakash. 2019. “When the River Talks to Its People: Local Knowledge-Based Flood Forecasting in Gandak River Basin, India.” Conceptualizing and Contextualizing Gendered Vulnerabilities to Climate Variability in the Hindu Kush Himalayan Region 31 (September): 55–67. doi:10.1016/j.envdev.2018.12.003.

- Aksa, Furqan Ishak. 2020. “Wisdom of Indigenous and Tacit Knowledge for Disaster Risk Reduction.” Indonesian Journal of Geography 52 (3): 418–426. doi:10.22146/ijg.47321.

- Ama, A. 2003. “Maeva: Rites of Passage, the Highlights of Family Life.” In Akono’anga Maori: Cook Islands Culture, edited by R. Crocombe, and M. Tua’inekore Crocombe, 119–126. Rarotonga: University of the South Pacific.

- Asugeni, J., D. MacLaren, P. D. Massey, and R. Speare. 2015. “Mental Health Issues from Rising Sea Level in a Remote Coastal Region of the Solomon Islands: Current and Future.” Australasian Psychiatry 23 (6_suppl): 22–25. doi:10.1177/1039856215609767.

- Barnett, J., and J. Campbell. 2010. Climate Change and Small Island States: Power, Knowledge, and the South Pacific. Abingdon: Earthscan.

- Beaglehole, Ben, Roger Mulder, Chris Frampton, Joseph Boden, Giles Newton-Howes, and Caroline Bell. 2018. “Psychological Distress and Psychiatric Disorder After Natural Disasters: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” The British Journal of Psychiatry 213 (October): 1–7. doi:10.1192/bjp.2018.210.

- Bengtsson, Mariette. 2016. “How to Plan and Perform a Qualitative Study Using Content Analysis.” NursingPlus Open 2 (C): 8–14. doi:10.1016/j.npls.2016.01.001.

- Björnberg, Karin Edvardsson, and Mikael Karlsson. 2022. “Faithful Stewards of God’s Creation? Swedish Evangelical Dominations and Climate Change.” Religions 13 (May): 465. doi:10.3390/rel13050465.

- Blacka, Matt, Francois Flocard, and B. Parakoti. 2013. Coastal Adaptation Needs for Extreme Events and Climate Change, Avarua, Rarotonga, Cook Islands. Project Stage 1: Scoping and Collation of Existing Data. WRL Technical Report 2013/11. Manly Vale: Water Research Laboratory, University of NSW.

- Bridges, Kent, and Will Mcclatchey. 2009. “Living on the Margin: Ethnoecological Insights from Marshall Islanders at Rongelap Atoll.” Global Environmental Change 19 (May): 140–146. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2009.01.009.

- Cámara-Leret, R., N. Raes, P. Roehrdanz, Y. De Fretes, C. D. Heatubun, L. Roeble, A. Schuiteman, P. C. van Welzen, and L. Hannah. 2019. “Climate Change Threatens New Guinea’s Biocultural Heritage.” ScienceAdvances 5 (November): eaaz1455. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aaz1455.

- Campbell, J. 2006. Traditional Disaster Reduction in Pacific Island Communities. Rep. 2006/38. Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences Tech.

- Campbell, John. 2009. “Islandness: Vulnerability and Resilience in Oceania.” Shima: The International Journal of Research Into Island Cultures 3 (January): 85–97. waikato.ac.nz.

- Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED), and UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR). 2020. Human Cost of Disasters: An Overview of the Last 20 Years. Brussels: CRED & UNDRR. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Human%20Cost%20of%20Disasters%202000-2019%20Report%20-%20UN%20Office%20for%20Disaster%20Risk%20Reduction.pdf.

- Charlson, F. J., S. Diminic, and H. A. Whiteford. 2015. “The Rising Tide of Mental Disorders in the Pacific Region: Forecasts of Disease Burden and Service Requirements from 2010 to 2050.” Asia & the Pacific Policy Studies 2 (May): 280–292. doi:10.1002/app5.93.

- Chishakwe, Nyasha, Laurel Murray, Muyeye Chambwera, and International Institute for Environment and Development. 2012. Building Climate Change Adaptation on Community Experiences: Lessons from Community-Based Natural Resource Management in Southern Africa. http://pubs.iied.org/pdfs/10030IIED.pdf.

- Cook Islands Meterological Service, Australian Bureau of Meterology, and Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO). 2011. “Current and Future Climate of the Cook Islands.” Pacific Climate Change Science Program Partners. https://www.pacificclimatechangescience.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/9_PCCSP_Cook_Islands_8pp.pdf.

- Cook Islands Statistics Office. 2018. Cook Islands Population Census: Census of Population and Dwellings 2016. Rarotonga: Cook Islands Statistics Office. http://www.mfem.gov.ck/images/documents/Statistics_Docs/5.Census-Surveys/6.Population-and-Dwelling_2016/2016_CENSUS_REPORT-FINAL.pdf.

- Dacks, R., T. Ticktin, A. Mawyer, S. Caillon, J. Claudet, P. Fabre, S. D. Jupiter, et al. 2019. “Developing Biocultural Indicators for Resource Management.” Conservation Science and Practice 1 (6). doi:10.1111/csp2.2019.1.issue-6.

- Dasgupta, P., and V. Ramanathan. 2014. “Pursuit of the Common Good.” Science 345: 1457–1458. doi:10.1126/science.1259406.

- de Scally, D. 2019. Because Your Environment is Looking After You: The Role of Local Knowledge in Climate Change Adaptation in the Cook Islands. Waterloo: University of Waterloo. https://uwspace.uwaterloo.ca/handle/10012/14399.

- Fair, Hannah. 2018. “Three Stories of Noah: Navigating Religious Climate Change Narratives in the Pacific Island Region.” Geo: Geography and Environment 5 (2): e00068. doi:10.1002/geo2.68.

- GEF, UNDP, SPREP, and Cook Islands Government. 2009. Pacific Adaptation to Climate Change: Cook Islands. SPREP. https://www.sprep.org/attachments/67.pdf.

- Gibson, K. E., J. Barnett, N. Haslam, and I. Kaplan. 2020. “The Mental Health Impacts of Climate Change: Findings From a Pacific Island Atoll Nation.” Journal of Anxiety Disorders 73 (June): 102237. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102237.

- Gómez-Baggethun, Erik, Esteve Corbera, and Victoria Reyes-García. 2013. “Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Global Environmental Change: Research Findings and Policy Implications.” Ecology and Society 18: 4. doi:10.5751/ES-06288-180472.

- Granderson, Ainka. 2017. “The Role of Traditional Knowledge in Building Adaptive Capacity for Climate Change: Perspectives from Vanuatu.” Weather, Climate, and Society 9 (May), doi:10.1175/WCAS-D-16-0094.1.

- Hiwasaki, Lisa, Syamsidik Emmanuel Luna, and José Adriano Marçal. 2015. “Local and Indigenous Knowledge on Climate-Related Hazards of Coastal and Small Island Communities in Southeast Asia.” Climatic Change 128 (1–2): 35–56. doi:10.1007/s10584-014-1288-8.

- Hunter, Ernest, Sneha Thusanth, Janya McCalman, and Narayan Gopalkrishnan. 2015. “Mental Health in the Island Nations of the Western Pacific: A Rapid Review of the Literature.” Australasian Psychiatry 23 (December): 9–12. doi:10.1177/1039856215610018.

- IPCC. 2013. “Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis.” In Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, edited by T.F. Stocker, D. Qin, G.-K. Plattner, M. Tignor, S.K. Allen, J. Boschung, A. Nauels, Y. Xia, V. Bex, and P.M. Midgley, 1535. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- IPCC. 2014. Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Johnston, Ingrid. 2015. “Traditional Warning Signs of Cyclones on Remote Islands in Fiji and Tonga.” Environmental Hazards 14 (3): 210–223. doi:10.1080/17477891.2015.1046156.

- Kelman, Ilan, Jessica Mercer, and Jennifer West. 2009. “Combining Different Knowledges: Community-Based Climate Change Adaptation in Small Island Developing States.” In Participatory Learning and Action 60: Community-Based Adaptation to Climate Change, edited by H. Ashley, N. Kenton, and A. Milligan, 41–53. London: International Institute for Environment and Development.

- Kelman, Ilan, and Jennifer West. 2009. “Climate Change and Small Island Developing States: A Critical Review.” Ecological and Environmental Anthropology 5 (1): 1–16.

- Kempf, W. 2017. “Climate Change, Christian Religion and Songs: Revisiting the Noah Story in the Central Pacific.” In Environmental Transformations and Cultural Responses, edited by E. Dürr, and A. Pascht, 9–48. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kuleshov, Yuriy, Simon McGree, David Jones, Andrew Charles, Andrew Cottrill, Bipen Prakash, Terry Atalifo, and Salesa Nihmei. 2014. “Extreme Weather and Climate Events and Their Impacts on Island Countries in the Western Pacific: Cyclones, Floods and Droughts.” Atmospheric and Climate Sciences 04 (05): 803. doi:10.4236/acs.2014.45071.

- Lata, S., and P. Nunn. 2012. “Misperceptions of Climate-Change Risk as Barriers to Climate-Change Adaptation: A Case Study from the Rewa Delta, Fiji.” Climatic Change 110: 169–186. doi:10.1007/s10584-011-0062-4.

- Latai-Niusulu, Anita, Tony Binns, and Etienne Nel. 2020. “Climate Change and Community Resilience in Samoa.” Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography 41 (1): 40–60. doi:10.1111/sjtg.12299.

- Lauer, Matthew, Simon Albert, Shankar Aswani, Benjamin S. Halpern, Luke Campanella, and Douglas La Rose. 2013. “Globalization, Pacific Islands, and the Paradox of Resilience.” Global Environmental Change 23 (1): 40–50. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2012.10.011.

- Lefale, Penehuro Fatu. 2010. “Ua ‘afa Le Aso Stormy Weather Today: Traditional Ecological Knowledge of Weather and Climate. The Samoa Experience.” Climatic Change 100 (2): 317–335. doi:10.1007/s10584-009-9722-z.

- Leonard, Sonia, Meg Parsons, Knut Olawsky, and Frances Kofod. 2013. “The Role of Culture and Traditional Knowledge in Climate Change Adaptation: Insights from East Kimberley, Australia.” Global Environmental Change 23 (3): 623–632. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.02.012.

- McMillen, Heather, Tamara Ticktin, Alan Friedlander, Stacy Jupiter, Randolph Thaman, John Campbell, Joeli Veitayaki, et al. 2014. “Small Islands, Valuable Insights: Systems of Customary Resource Use and Resilience to Climate Change in the Pacific.” Ecology and Society 19 (December): 44. doi:10.5751/ES-06937-190444.

- McNamara, Karen E., Rachel Clissold, Ross Westoby, Annah E. Piggott-McKellar, Roselyn Kumar, Tahlia Clarke, Frances Namoumou, et al. 2020. “An Assessment of Community-Based Adaptation Initiatives in the Pacific Islands.” Nature Climate Change 10 (7): 628–639. doi:10.1038/s41558-020-0813-1.

- McNamara, Karen Elizabeth, and Shirleen Shomila Prasad. 2014. “Coping with Extreme Weather: Communities in Fiji and Vanuatu Share Their Experiences and Knowledge.” Climatic Change 123 (2): 121–132. doi:10.1007/s10584-013-1047-2.

- Mercer, Jessica, Dale Dominey-Howes, Ilan Kelman, and Kate Lloyd. 2007. “The Potential for Combining Indigenous and Western Knowledge in Reducing Vulnerability to Environmental Hazards in Small Island Developing States.” Environmental Hazards 7 (4): 245–256. doi:10.1016/j.envhaz.2006.11.001.

- Morrissey, Shirley A., and Joseph P. Reser. 2007. “Natural Disasters, Climate Change and Mental Health Considerations for Rural Australia.” Australian Journal of Rural Health 15 (2): 120–125. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1584.2007.00865.x.

- Mortreux, C., and J. Barnett. 2009. “Climate Change, Migration and Adaptation in Funafuti, Tuvalu.” Global Environmental Change 19: 105–112. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2008.09.006.

- Naess, Lars Otto. 2013. “The Role of Local Knowledge in Adaptation to Climate Change.” WIRES Climate Change 4 (2): 99–106. doi:10.1002/wcc.204.

- Nakamura, Naohiro, and Yoko Kanemasu. 2020. “Traditional Knowledge, Social Capital, and Community Response to a Disaster: Resilience of Remote Communities in Fiji After a Severe Climatic Event.” Regional Environmental Change 20. doi:10.1007/s10113-020-01613-w.

- Nakashima, D., K. Galloway McLean, H. Thulstrup, A. Ramos Castillo, and J. Rubis. 2012. Weathering Uncertainty: Traditional Knowledge for Climate Change Assessment and Adaptation. Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation and United Nations University - Traditional Knowledge Initiative.

- North, Carol, and Betty Pfefferbaum. 2013. “Mental Health Response to Community Disasters A Systematic Review.” JAMA : The Journal of the American Medical Association 310 (August): 507–518. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.107799.

- Nunn, P. 2017. “Sidelining God: Why Secular Climate Projects in the Pacific Islands Are Failing.” The Conversation. http://thecon versation.com/sidelining-god-why-secular-climate-projects-in-the-pacific-islands-are-failing-77623.

- Nunn, Patrick, Kate Mulgrew, Bridie Scott-Parker, Donald Hine, Anthony Marks, Doug Mahar, and Jack Maebuta. 2016. “Spirituality and Attitudes Towards Nature in the Pacific Islands: Insights for Enabling Climate-Change Adaptation.” Climatic Change 136. doi:10.1007/s10584-016-1646-9.

- Padhy, Susanta Kumar, Sidharth Sarkar, Mahima Panigrahi, and Surender Paul. 2015. “Mental Health Effects of Climate Change.” Indian Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 19 (1): 3–7. doi:10.4103/0019-5278.156997.

- Rongo, Teina, and C. Dyer. 2014. Using Local Knowledge to Understand Climate Variability in the Cook Islands. Rarotonga: Office of the Prime Minister of the Cook Islands, Secretariat of the Pacific Community, European Union, the Global Climate Change Alliance, the Adaptation Fund, and the United Nations Development Program. https://www.adaptation-undp.org/resources/document/using-local-knowledge-understand-climate-variability-cook-islands-january-2015.

- Rubow, C. 2009. “The Metaphysical Dimensions of Resilience: South Pacific Responses to Climate Chance.” In The Question of Resilience: Social Responses to Climate Change, edited by K. Hastrup, 88–113. Copenhagen: The Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters.

- Rubow, Cecilie. 2018. “3 Woosh–Cyclones as Culturalnatural Whirls: The Receptions of Climate Change in the Cook Islands: Living Climate Change in Oceania.” In Pacific Climate Cultures: Living Climate Change in Oceania, edited by T. Crook, and P. Rudiak-Gould, 34–44. Warsaw: De Gruyter Ltd. doi:10.2478/9783110591415-004

- Rubow, C., and C. Bird. 2016. “Eco-Theological Responses to Climate Change in Oceania.” Worldviews: Global Religions Culture, and Ecology 20: 150–268. doi:10.1163/15685357-02002003.

- Rudiak-Gould, P. 2009. The Fallen Palm: Climate Change and Culture Change in the Marshall Islands. Saarbrücken: VDM Verlag.

- Sattler, David N. 2017. “Climate Change and Extreme Weather Events: The Mental Health Impact.” In Climate Change Adaptation in Pacific Countries: Fostering Resilience and Improving the Quality of Life, edited by Walter Leal Filho, 73–85. Cham: Springer International Publishing. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-50094-2_4.

- Taylor, A. J. W. 1999. “Value Conflict Arising from a Disaster.” The Australian Journal of Disaster and Trauma Studies 3. http://www.massey.ac.nz/~trauma/issues/1999-2/taylor.htm.

- Thornton, Alec, Minako Sakai, and Graham Hassall. 2012. “Givers and Governance: The Potential of Faith-Based Development in the Asia Pacific.” Development in Practice 22 (August): 779–791. doi:10.2307/41723138.

- United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. 2012. Analysis of Disaster Response Training in the Pacific Island Nation. Suva: OCHA Regional Office for the Pacific. https://reliefweb.int/report/cook-islands/analysis-disaster-response-training-pacific-island-region-provisional-version.

- Van Dyke, Fred, David C Mahan, Joseph K Sheldon, and Raymond H. Brand. 1996. Redeeming Creation: The Biblical Basis for Environmental Stewardship. Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press.

- van Susteren, Lise, and Wael Al-Delaimy. 2020. “Psychological Impacts of Climate Change and Recommendations.” In Health of People, Health of Planet and Our Responsibility: Climate Change, Air Pollution and Health, edited by Wael Al-Delaimy, V. Ramanathan, and M. Sánchez Sorondo, 177–192. Cham: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-31125-4_14

- World Bank. 2015. Country Note: The Cook Islands. Washington, DC: World Bank. http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/405171468244771591/pdf/949800WP0Box380ry0Note0Cook0Islands.pdf.