ABSTRACT

Social sustainability has increasingly become a goal for urban policy and planning, and for local and regional developmental strategies. Neighbourhoods are a common spatial scale for studying social sustainability and there is a growing focus on social sustainability in urban neighbourhoods for both researchers and policymakers. This paper is based on a qualitative case study of a neighbourhood defined by the municipality as at-risk of negative social development in a municipality in northern Sweden. The aim is to describe the perceived threats and promoters for social sustainable development in a neighbourhood defined as at-risk, and to analyse these in relation to a perspective of spatial scale. The study is based on data from interviews with municipal representatives, local professionals and residents, representing different experiences and perspectives in the neighbourhood. Four themes illustrating threats to socially sustainable development were identified: crime, unrest and unsafety; segregation and social exclusion; reputation and stigmatisation; and low involvement in municipal processes. The promoters for socially sustainable development identified in the respondents’ stories reflect four themes: strong community spirit; safety and low criminality; lively civic society and well-functioning public services. Our results show that neighbourhood social sustainability cannot be studied or acted upon without being put in a context of spatial scale and an understanding that processes occurring at a particular scale only can be adequately understood when considered in relation to other scales, i.e. the development in the neighbourhood can only be understood in relation to the development in the city and at national level. There is also a need for an awareness of how different aspects of socially sustainable development relate to each other, by strengthening or counteracting each other.

Key policy highlights

There are no “magic bullet solutions” to ensure social sustainable development at the local level. Rather, actions and interventions must embrace complexity.

The risk for counteracting processes must be acknowledged in any actions to promote social sustainability.

Social sustainability processes occurring at a particular scale can only be adequately understood and addressed when considered in relation to other scales.

Introduction

The concept of social sustainability was introduced in 1987 by the UN-issued World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED) in the report Our Common Future. The key message of the report is a call for joint responsibility for “the security, wellbeing, and very survival of the planet” (WCED Citation1987). Goal 11 in the Agenda 2030, i.e. the UN Sustainable Development Goals, states that cities should be inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable. Social sustainability has increasingly become a goal for urban policy and planning, and for local and regional developmental strategies (Woodcraft Citation2012). Despite this, the notion of social sustainability and social sustainable development is still quite vaguely defined (compared to economic and environmental sustainability) and is often said to be oversimplified and under-theorised (Shirazi and Keivani Citation2017). One way of contributing to the theoretical discussion is to link the concept to other social science perspectives, concepts or theories (Boström Citation2012). In this study, we add the perspective of spatial scale.

In Western Europe, almost all major cities have areas that can be classified as deprived, in a relative sense. These areas are characterised by high levels of residential turnover, unemployment and benefit dependency, a high rate of economic and social problems including drugs and crime, as well as reduced services and problems with maintenance. Through segregation processes, people with different living situations may gather in the same neighbourhoods, meaning that there is a spatial division between groups with different economic conditions and a concentration of people and families with vulnerable living conditions in certain areas. In Sweden, as in many other countries, the segregation also has an ethnic dimension, and deprived areas often have a large proportion of immigrants (Andersson and Bråmå Citation2004).

Since the economic crisis in the 1990s, segregation and polarisation in both smaller and larger cities have been in the spotlight for both the public debate and academic research in Sweden. Most often, it has been the large scale, high-rise apartment blocks produced in the 1960s and 1970s, as well as the suburbs of metropolitan areas, that have been at the centre of the debate, dominated by a mainly problem-oriented story (Dahlstedt and Lozic Citation2017). While the problem discourses of the 1970s were primarily about the residents’ working-class background and low level of education, the discussions since the 1980s have been centred around issues of migration, cultural differences, racialisation, ethnicity and segregation (Lozic Citation2018), and security and safety issues have generally been given an increasingly prominent role (Hansen Löfstrand Citation2015). The general social sustainability research, as well as the Swedish policy, generally focuses on low-resource and stigmatised neighbourhoods, while the homogeneous well-off housing neighbourhoods are not subject to measures (Andersson, Bråmå, and Holmqvist Citation2010). In this paper, we focus on the scalar context to move beyond the focus on the neighbourhoods and we argue that neighbourhood social sustainability cannot be studied or acted upon without being put in a context of spatial scale.

Aim

This paper is based on a case study of a neighbourhood defined by the municipality as at-risk of negative social development in Umeå Municipality in northern Sweden. This study aims to describe the perceived threats and promoters for social sustainable development in a neighbourhood defined as at-risk, and to analyse these in relation to a perspective of spatial scale.

This study is part of a larger research project entitled Social Capital as a Resource for the Planning and Design of Socially Sustainable and Health-Promoting Neighbourhoods – A Mixed Method Study, funded by the Swedish Research Council for Sustainable Development (see Santosa et al. Citation2020).

Theory

The last few decades have witnessed a revival of theoretical interest in geographical space and scalar politics in the social sciences (c.f. Brenner Citation1998; Lefebvre Citation1991). This paper builds on a theoretical understanding of spaces and scales as social and political constructions rather than ontologically given. Both places and spaces should be understood as the dialectical relation between material practices and the symbolic meaning that social agents attach to their environment (Marston Citation2000; Richardson and Jensen Citation2003). Scale is a relational concept, meaning that, for instance, a city should be viewed in relation to other cities at the same hierarchical level (Born and Purcell Citation2006; McCann Citation2003). Treating scale as a theoretical concern, rather than just an empirical issue, can contribute to an understanding of the processes that shape social practices at different levels of analysis (Marston Citation2000).

Based on the conceptualisation of space by Westlund, Rutten, and Boekema (Citation2010), we understand horizontal space as a space in which borders and barriers make distance discontinuous. The barriers can be, for instance, natural geographical borders or state borders, but also class and social barriers or language borders. Hierarchical space is understood as a space divided into discontinuous levels, contributing to the solidarity of the hierarchy (Westlund, Rutten, and Boekema Citation2010).

Born and Purcell (Citation2006) state that no scale can have an external extent, function or quality. Rather it comes from particular political struggles among particular actors in particular times and places. Scale is framing the conceptions of reality, and as such, scale is both the result of political processes and shaping political processes (Delaney and Leitner Citation1997). The choice of a certain spatial scale has material consequences. Rescaling can be used to redefine scales and to reorganise interactions between scales. This can be accomplished by shifting policies, politics and practice from one scale to another – downwards, upwards or sideways (Jessop Citation1996; Richardson and Jensen Citation2003).

Shirazi and Keivani (Citation2017) emphasise the multiscalar character of social sustainability and point out that there is no scalar significance, since the micro-scale perspective is as important as the macro-scale perspective. Case and context relevance is necessary when studying social sustainability. One context factor that needs to be considered is the territorial scale since social sustainability indicators might change when upscaling or downscaling the spatial focus (Shirazi and Keivani Citation2017). Neighbourhoods are a common spatial scale for studying social sustainability and there is a growing focus on social sustainability in urban neighbourhoods for both researchers and policymakers (Dempsey et al. Citation2011). Neighbourhoods become favoured as the unit of analysis since there is a perception that neighbourhoods are “the actual sites where social urban qualities such as social interaction, collective activities, and public engagement are practised by the inhabitants on a daily basis” (Shirazi and Keivani Citation2019, 449).

A number of scientific papers have tried to define the concept of social sustainability in relation to urban planning, the built environment and neighbourhoods. For this study, we use the conceptualisations and definitions from three reviews of social sustainability definitions (Bramley and Power Citation2009; Shirazi and Keivani Citation2017; Weingaertner and Moberg Citation2014) as conceptual frames to be able to describe the respondents’ perceptions of both threats and promoters for social sustainable development. We believe that these three reviews together cover the general themes in the discussion on social sustainable development in the research field.

We agree with Shirazi and Keivani’s (Citation2017) remarks about the necessity of the case and context relevance, and in this paper, we focus on the scalar context, to challenge the focus on the neighbourhood spatial level in social sustainability research. The case in this study is a neighbourhood defined as at-risk in a city and a region with high social sustainability ambitions, and we have chosen to study social sustainable development through a theoretical lens of scale.

Material and methods

Study context – Umeå municipality and the case neighbourhood

This study was conducted in a neighbourhood (hereafter entitled “The District”) in Umeå, a fast-growing municipality in northern Sweden with approximately 130,000 inhabitants (see maps in appendix 1). The Umeå region ranks high in social progress regarding basic human needs and foundations of well-being according to the European Commission Social Progress Index (Citation2020).

Since 2015, the Swedish Police have been mapping and classifying certain Swedish areas with low socio-economic status and high crime rates based on several indicators such as the residents’ propensity to participate in legal processes, possible parallel social structures and extremism. A total of 61 areas throughout the country, corresponding to approximately 566,000 residents, are classified as “vulnerable areas” (NOA Citation2017). Thus, in the Swedish context, “vulnerable area” refers to a special type of neighbourhood that meets certain specific criteria, as determined by the police, and accordingly, something other than a more general description of vulnerability, although these can overlap. The municipality in this study is considered to be relatively equal since it has no neighbourhoods defined as “socially vulnerable” by the Swedish police authority.

Compared to the rest of the municipality, the District hosts a comparable large proportion of families with children, a higher proportion of foreign-born people and a large proportion of its population lives in condominiums and tenancies, and a relatively small proportion lives in detached houses. The relative child poverty is higher in The District, but the average income is somewhat above average. The proportion of highly educated people in this neighbourhood is lower, and the incidence of ill health is considerably higher than for other districts (Umeå Municipality Citation2020) .

Table 1. Sociodemographic and socio-economic characteristics of the district and all urban districts in Umeå municipality.

Based on an internal local police report from 2017, the municipality identified a number of potential threats related to crime and insecurity in the neighbourhood. The District has therefore been targeted by a municipal initiative with the overall goal of “increasing security, reducing crime and counteracting tendencies to social unrest”, including a number of activities such as an increased police presence, investments in the physical environment and the establishment of meeting places for young people (Hanberger and Lindgren Citation2021). Within our broader research project, in which this case study was conducted (Santosa et al. Citation2020), we have investigated the development of social capital (as an indicator for social sustainability) in 46 neighbourhoods in Umeå municipality by means of repeated surveys to a representative sample of the adult population (Eriksson et al. Citation2021). The District was one of the neighbourhoods that showed a somewhat negative development of social capital (and thus social sustainability) during the period 2006–2020. The selected case neighbourhood thus represents an interesting case for investigating threats and promoters of local social sustainable development, along with the role of different spatial scales for understanding the prerequisites for local sustainable social development.

Empirical material

This study was designed as a qualitative case study based on data from interviews with respondents representing different experiences and perspectives on the District. A case study approach implies an in-depth exploration of an “event”, bound in time and place and using several sources of information (Creswell and Poth Citation2016). The interviews were semi-structured and followed a thematic interview guide. Interviews were complemented with municipal policy documents that provided additional perspectives on municipal decisions and interventions.

Interviews with 17 purposely selected participants were conducted to gain an in-depth knowledge of the District. Informants were sampled purposively using a snowball technique. Three different groups of participants were invited. The first group consisted of municipal civil servants (4 women, 2 men) with an overall responsibility for the city- and municipal planning. They gave insight into strategic decisions, and interventions connected to social and housing issues during the last decades, in the city as a whole and in the District. The second group consisted of local professional stakeholders (4 women, 2 men) who worked in the District and represented various public services including healthcare and social services, schools and the police. Some of the respondents in this group are thus also employed by the municipality but have their workplace in the District and represents a clear local perspective, unlike the municipal civil servant in the first group who in their profession have a municipal perspective. The third group of interview participants consisted of residents (2 women, 3 men) living (and in some cases working) in the neighbourhood. They were identified as key persons in the neighbourhood who represented civil society or different interest groups, providing a layperson and insider perspective on the neighbourhood. Some participants were recruited by first identifying an organisation or company that appeared important in the neighbourhood, and then finding a person within the organisation willing to be interviewed.

All interviews were semi-structured and followed a thematic interview guide (see appendix 2) that was slightly adapted to each respondent. The interview guide contained questions about perceptions and experiences of the social climate in the neighbourhood, reflections about how this had changed over time, perceptions about the pros and cons of working and living in the area, as well as opinions and experiences of housing and social policies that have been implemented in the neighbourhood. The interviews lasted from one up to more than 2 h. Due to the pandemic situation, some interviews were conducted by video call. When the pandemic restrictions allowed, some interviews were conducted at the participants’ workplaces or in a café. On two occasions, two informants participated jointly in the interview, in line with their preferences. Interviews were recorded with approval from the respondent and later transcribed.

Analysis

The material was analysed using a thematic analytical approach, following Braun and Clarke (Citation2006). Our chosen conceptual frameworks, i.e. social sustainable development and spatial scale, were used as sensitising concepts, i.e. they suggested directions along which to look at our data, without steering exactly what to see (Clarke Citation2003). Thus, the analysis implied an abductive process of moving back and forth between data and theory.

Initially, all interviews were carefully read and re-read to become familiar with the data. Following the steps of thematic analysis suggested by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006), the next step involved generating initial data codes. The initial coding was conducted openly, and extensive notes and memos were also taken, to document analytical ideas emanating from engaging with and coding the data. In the next step of the analysis, the open codes were grouped based on their content, which helped to identify recurrent themes and patterns in the data and decide on what analytical path to follow in the subsequent analysis. This resulted in 13 numbers of preliminary themes which were reviewed and compared against our conceptual frameworks of social sustainable development and spatial scale, to reveal the most significant themes for our study. This abductive process led to the construction of four themes describing perceived threats against social sustainable development and additional four themes describing perceived promoters. In the final step of the analysis, the eight constructed themes were analysed in the light of our chosen conceptual frames, involving a construction of thematic map, i.e. an “overall conceptualisation of the data patterns, and relationships between them” (Braun and Clarke Citation2006, 89). The final thematic map was influenced by Clarke’s (Citation2003) “Situation Analysis” and her conceptualisation of positional maps. In the analysis, the thematic positional map was used to rule out the positions taken about threats and promoters for social sustainable development and how these belong to different spatial levels.

Ethical and methodological considerations

The research was approved by the Swedish Ethics Review Authority (Dnr: 2019-04395, 2019-10-28; Dnr: 2020-00160, 2020-02-18, 2020-06-08; Dnr: 2020-02757). Before the interview, all participants received written and oral information about the study. They were informed of the purpose of the study and of their right to withdraw at any time. Moreover, we assured them that all information would be handled confidentially and in accordance with ethical guidelines for social science research. We recognise that investigating an area defined (by others) as “at risk” can further stigmatise a location. In some interviews, we tried to highlight this (this was mainly an issue in the resident group). The fact that one of the researchers (ME) had been living in the case neighbourhood herself for a long period of time, also enabled a combined insider-outsider perspective from the researcher’s side and helped to build trust in some of the interviews with residents and civil society representatives.

Qualitative research is not to generalise but rather to provide a rich, contextualised understanding of some aspect of human experience through a detailed exploration and theorising of particular cases (Polit and Beck Citation2010). Our chosen theoretical perspective of spatial scale influenced and focused the analysis to generate themes relating to spatial scale. Another theoretical perspective could have guided the analysis in another theoretical direction. Still, we believe that scale perspective adds important understanding into the field of social sustainable development and that our results could be transferable to other similar settings with neighbourhoods defined as vulnerable or at risk. However, this warrants further empirical studies to judge.

Results and analysis

This section presents results and analysis, structured according to the study’s objectives. First, we describe perceived threats and promoters for social sustainable development Quotes are used to illustrate how the findings are grounded in the data. Finally, we analyse the constructed themes in relation to a perspective of spatial scale.

Perceived threats to social sustainable development

Four themes illustrating threats to socially sustainable development were identified in the data: (1) crime, unrest and unsafety; (2) segregation and social exclusion; (3) reputation and stigmatisation and (4) low involvement in municipal processes.

Crime, unrest and unsafety

The first theme describing threats to social sustainable development concerns crime, unrest and unsafety, and the respondents highlighted drug trafficking and juvenile delinquency as the most salient problems. Drug trafficking has occasionally occurred in an open manner in the small local city centre. According to the respondents, drug trafficking was also linked to the recruitment of young people, or at least the socialisation of young people, into a criminal environment. Although it is not relevant to talk about criminal gangs in the neighbourhood, there were clearly loosely organised criminal groups that were responsible for a significant part of the problems that concerned the police. The small local centre was also a gathering place for the District’s young people. Most of them have no connection to crime at all, but “the gangs that hang out in the centre” reappeared in the respondents’ stories and were presented almost as synonymous with crime or at least insecurity. Over the last several years, the police have invested in the establishment of a strong local presence in the area, including through the establishment of community police. The work of the community police has mainly been based on a security perspective and the work has therefore focused on visible crime, especially the open drug trade. At the same time, the police officers interviewed were also careful to point out that the vast majority of people in the District have nothing to do with crime, and that those who are responsible for the majority of the crimes are a small group.

Another problem the police identified in the District was a general mistrust of authorities, and of the police in particular. This was perhaps more widespread in the neighbourhood than the crime itself. According to the police officers interviewed, one of the basic ideas with the community police work is therefore that the police should work to build trust and good relations with the people living in the District. One of the police officers related trust to ethnic background when explaining why building trust is essential:

If you have lived in a society in a country where you have never been able to trust the state, you change countries and then we say about the police “Trust us” “No”. Because they do not trust us. / … / So that trust, to build that trust, it’s not that simple. Even now, in some cases – this can happen over centuries, so that many of these young people were born in Sweden, but they still do not trust us. (Police Officer)

Segregation and social exclusion

The second theme describing threats to social sustainable development concerns segregation and social exclusion. One aspect is that there seemed to be groups in the District who did not have access to the same public service as others, or for some reason did not use some public services. Among the local social work, healthcare and school professionals, the respondents highlighted the fact that there are groups in the District that they cannot reach with their activities. The respondents believed that there is sometimes a lack of understanding of how the Swedish welfare society works. Another explanation was about language barriers. The local professional respondents also highlighted their own organisations’ lack of diversity as a problem. There was simply a lack of employees who could access groups that are difficult to reach, for example, by being able to speak one of the minority languages spoken in the area or through shared cultural experiences. The local professionals expressed recurring frustration over the situation they were in. Lack of resources, especially in terms of time, makes it impossible to meet the needs that are observed. Another reason why they felt that they cannot work as they want is a lack of coordination and collaboration between different bodies, and an overly rule-governed and inflexible organisation that makes change and new initiatives more difficult. The local professionals also criticised a lack of long-term perspective, which means that initiatives are often short-term or insufficient.

In the District, there seem to be parts of the population that do not have the same access to associations, meeting places and networks as others in the area and the city. Many children do not have access to leisure activities due to financial obstacles or have parents who do not have the opportunity to drive to or attend leisure activities. The problem of internal obstacles within associations is also concerning, such as too inflexible or rule-governed approaches, e.g. what clothes or equipment the children need in order to participate. A consequence that was highlighted in the interviews was also that the lack of leisure activities in itself contributes to the adverse social climate in the neighbourhood since young people have nothing to do and instead hang around in the centre.

Some local professionals saw an additional form of social exclusion as a consequence of the overall focus on crime and unsafety in the District. There is the lack of focus and resources for groups with other more “invisible” social problems. One local healthcare worker talked about the environment in the local schools:

And the girls get missed a lot in this. I have met several girls who may have some difficulties and their own mental illness, and I think that ‘in a different class, in a different environment, this girl could blossom’. But if it is chaos, fire brigade calls and quarrels all the time, then clearly that it is not possible. And it is not the case that the teachers or principals do not see it or want to work with it. When there are a lot of problems, the threshold for what you can work on and what real problems there are shifts. (Local healthcare worker)

Reputation and stigmatisation

A recurring theme in the residents’ stories is stigmatisation and the bad reputation of the District. Since the District was built in the late 1970s and early 1980s, it has had and still has a negative reputation. One of the residents described how she loves her neighbourhood, but the outsiders often have a very different opinion of it: “Yeah, all that’s a general picture and I’ve even heard people asking ‘But how do you dare stay in the District?’ Most of them have not even been here” (Resident).

The respondents who live and work in the District said that a strong contributing factor to the bad reputation is how their area is portrayed in the media. They felt that the media especially highlights negative things that happen, while the same event in another area would not as clearly be connected to the place where it happened. The reputation and media image seems to affect everyone who lives and works in the area. Some of the respondents even talked about it as a form of stigma.

It is apparent from the interviews that the national debate about “vulnerable areas” and how these should be understood and counteracted was an important reference point for the municipal civil servants and the police officers. For instance, they anticipated a situation whereby the District eventually will become a “vulnerable area”. According to one of the police officers interviewed, the District now is like “Rinkeby in the 90s”, an area of Stockholm, Sweden, that is referred to as one of the most stigmatised suburbs in the country. The District was thus not explicitly described by the respondents as a “vulnerable area” – on the contrary, the municipal officials were careful to point out that this is not the case, as shown in the following quote:

Umeå is the largest municipality in Sweden without a vulnerable area, but according to this report we have a similar problem as many vulnerable areas even if it is not on the same scale, an incipient … problem you can say. (Municipal Official)

Low involvement and trust in municipal processes

The fourth theme illustrating threats to social sustainable development is low involvement and trust in municipal processes. The professionals working in healthcare, education and social work in the District, described poor communication, lack of participation in decision-making processes, and in some cases contradictions between local actors and decision-makers in the municipal hierarchy. In some cases, they described processes that outwardly look like collaboration but where there is no real influence or possibility for co-determination: “Well, we participate in meetings and such, but often the decisions have already been made”, said one local professional. In other cases, the respondents felt that there is a clear top-down perspective, where instead of really listening to the employees’ experience and opinions, there is a tendency to make decisions that do not always correspond to the actual needs and thus appear as wrong priorities for those who work in the District. A concrete example was a political proposal about a certain social work method that one of the social workers described in the interview. The outreach work method, which aimed to reach new mothers who otherwise do not visit the health centre, had been requested by the staff earlier as they saw possible positive effects from using the method. At that time, they did not have the opportunity to work according to the method because resources, in the form of time and staff, were lacking. Therefore, they were surprised when they read about a political proposal to introduce the method because it also partly contained criticism that the staff failed in working with the target group in the best way. The new proposal was thus not perceived as a support for the healthcare centre staff but instead as a sign of the politicians’ lack of local grounding in the organisation and as an attempt at top-down governance.

The view that the municipal decision-making processes suffer from shortcomings in governance and co-determination was not shared by the interviewed municipal officials. On the contrary, some described how they worked actively to establish locally established processes. There was thus a clear discrepancy between how local professional representatives and municipal officials perceived the decision-making and collaboration processes.

Perceived promoters for social sustainable development

The promoters for socially sustainable development identified in the respondents’ stories reflect four themes: (1) strong community spirit; (2) safety and low criminality; (3) lively civic society; and (4) well-functioning public services.

Strong community spirit

There was a strong sense of cohesion and a strong local identity shared by many of those we interviewed who lived or worked in the District. There seemed to be a strong community spirit in which residents value their neighbourhood and identify with it positively. The diversity in the District was often highlighted in positive terms as an enriching feature that distinguishes the neighbourhood from other neighbourhoods. Several respondents claimed that the inhabitants of the District thrive and like their neighbourhood. The District was described as stable, and many of those who live in the area have lived there for a long time. According to one of the local professional respondents, many of the families she meets in her job are new parents who grew up in the area and have now chosen to return after the birth of their children. When the respondents were asked to compare the District to other neighbourhoods, they described how the District is more characterised by warmth, love and openness than other neighbourhoods. Several respondents described the District as welcoming and mentioned that people more often talk to others they meet on the street and that they more often know and have a relationship with their neighbours. The District was sometimes described as a small village, where you have most things you need in terms of shops and other things and where you know and feel safe with most people in the neighbourhood:

Yes, in the yard, yes, I usually help an old aunt to shop and she invites me for coffee and … my Pakistani neighbour had bought the wrong rice so then I got a big sack there … No but, so it’s like … a little closer contact I think between neighbours. / … / it becomes like a small community right in the city. (Resident)

When I meet friends from Stockholm, I kind of explain to them that ‘I live in Umeå’s Rinkeby’ / … / That is, I say it with pride. I feel safe and at home here. (Resident)

Safety and low criminality

Police and the municipality often pointed out that the District is one of the more dangerous neighbourhoods in the city. People living and working there, however, described the neighbourhood as safe, or at least not more unsafe than other neighbourhoods in the city. The image of insecurity conveyed in the municipal documents, and in the interviews with the police officers was contradicted in the interviews with the residents in the District. Some turned against the image that they felt that the media, politicians and outsiders have of their area. Some argued that the descriptions of the area have entirely lost all proportions and that there is too much focus on a small group of criminal individuals. Several respondents pointed out that the group of young people who are criminals, or are at risk of falling into crime, is limited, and most of the residents live “completely ordinary lives”. When the respondents who live in the area were asked where they thought this image of dangerous youth gangs comes from, a few talked about it in terms of racism. They believed that the image of the young people that are considered “dangerous” clearly is linked to the young people’s skin colour and appearance. One respondent said that when some blonde girls stand and talk in a group, no one thinks they are criminals, but when young guys who look “foreign” and have a certain type of clothing are seen together, they are judged in advance.

Some of the residents shared another aspect of safety and security, they claimed that they do not feel safe in the rest of the city but feel safe in the District. For example, it is about feeling that the “Swedes” who live in the District are not as prejudiced as other “Swedes":

When you are with Swedes who come from an area like this, then they have a different understanding, at least I have experienced that. / … / To be able to go out and be yourself. It will not be like “that girl is not Swedish”. (Resident)

Lively civic society

We interviewed older residents who described a solid social ethos and a commitment to social issues in the District even when it was newly built. Early on, the District’s first sports club, a scout association and a choir were formed and a local Community Centre was opened. The civic society is still strong in the area, and there are associations with connections to the sports, the labour and the sobriety movements. There are also several active religious associations and cultural associations. Many of the interviewees, both municipal officials, local professional stakeholders and residents, praised the work done by the established associations in the area. At the same time, some of the younger respondents living in the District conveyed a slightly different picture that we already touched upon.

One of the respondents who grew up in that area, established his own sports club in response to what he perceived as structural discrimination and racism within the established associations. Founded about 10 years ago, the club has specifically addressed the needs of young people in the District who cannot afford to pay for equipment or who do not have the opportunity to attend regularly. According to the respondent, many of the young people who attend training are poor and some of whom were newly arrived refugees. The club also aims to educate the young people who participate in the activities in the more formal parts of running a sports club. Many board members are under 20, and most have no or little similar experience. The club is mentioned in many other interviews as an excellent example of how to work to reach specific groups of young people in the area.

Another important association in the neighbourhood is the youth association run by one of the large Swedish temperance movements. The activities they run in the District are more aimed at younger children and offer both an open leisure centre and various excursions and are run mainly by non-profit leaders. The association is active in the whole city but has most of its activities in the District and one other neighbourhood with relatively high child poverty rates. This is no coincidence, according to one of the leaders:

This has been a conscious choice. … The children who are left at home when everyone else goes to training or goes to the bathhouse, who are always left for different reasons when everyone else goes, this is exactly where we should be, that we start with the child who stands and watches when everyone else goes to the bathhouse or … We must be there. (Resident and leader in a local youth association)

Another example of successful civic activities in the District is the groups for fathers and mothers run by local enthusiasts in the Community Centre. The groups were initially aimed at Somali parents, but they have grown ever since they started. During the meetings, they talk about topics that the parents themselves think are relevant, e.g. what obligations the school has towards the children, or what the social services can help with.

Public services: committed staff, well-functioning services and collaboration

Even though the public service in the District clearly has weaknesses and challenges, as we already described, the predominant impression of the interviews is that the public service in the area works relatively well. The staff in the public organisations in the neighbourhood, such as the schools or the family centre, seemed to thrive, many were passionate about their work and really wanted to make a difference. From the respondents it appears that many professionals actively seek jobs in the area and several also emphasised that the staff in the District in general is very competent. There are also signs in the interview material that the municipality invests more in the District than in other neighbourhoods. In a comparative perspective, the District does not necessarily appear to be a downgraded or “forgotten” neighbourhood. One example is the popular local library. The librarian said that they actively work with outreach activities for both children and adults.

Put simply, we have a budget for programmes and not all branch libraries have them. The City Library does, of course, but.. but we still have a relatively large budget for doing adult programs and there has probably been a thought about it, I think, that it has been here in the District (Local librarian)

Another concrete example of collaboration in the District is the summer activities for children and young people. The premise for the project is, said one municipal official that summer is a risk period for many children and young people, when the stability and structure that the school usually provides does not exist. The municipal housing company, the youth centre, the local soccer club and other local organisations together run a summer soccer camp for children. In the camp, the children are served meals and provided with some clothes. For the older children, around the age of 16, there are opportunities to get a summer job, paid by the municipality. The local preventive councils and the staff at the local youth centre have had the opportunity to influence which young people are employed, in order to support those who otherwise do not have networks or families who can arrange summer jobs. The young people get to work at the municipal housing company to clear the flower beds, repaint houses or manage premises. Leaders from local civic associations function as supervisors and support them in the work.

Perceived threats and promoters within the perspective of spatial scale

In this section, we analyse the constructed categories about threats and promoters in relation to a perspective of spatial scale.

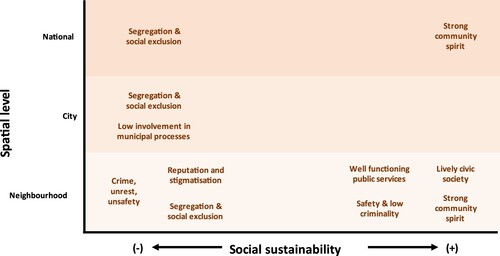

summarises the analysis of perceived threats and promoters of social sustainable development in relation to spatial scale. In the figure, the X-axis represents social sustainable development, which goes from the threats to a socially sustainable development, to promoters. The Y-axis represents a scale of hierarchical space (cf. Westlund, Rutten, and Boekema Citation2010) from neighbourhood level to national level, with the city in between.

Strong community spirit in a stigmatised neighbourhood with a bad reputation

The strong community spirit in the District is striking in our interviews. Pride and sense of place (Bramley and Power Citation2009; Shirazi and Keivani Citation2017), and sense of place and belonging (Weingaertner and Moberg Citation2014) are generally considered important promoters for socially sustainable development, and strong community spirit at the neighbourhood level is therefore placed far to the right of the sustainable development scale in . But equally, the respondents also told us stories about the feeling of not belonging or not being part of the majority society and the rest of the city, and we have therefore placed segregation and social exclusion as a threat to social sustainable development on the city level in . Scale appears as an important factor that frame the conceptions of reality (c.f. Delaney and Leitner Citation1997), as the symbolic meaning that the respondents’ attribute to their neighbourhood looks different, depending on whether they are talking about the District itself, or about the District in relation to the rest of the city. The scalar context of the stories is framing how the District is being described. In the interviewees’ stories, there was also a very clear internal status of hierarchy between all neighbourhoods of the city, where the residents know that the District is perceived to be at the bottom. The symbolic meaning that their neighbourhood was given in relation to other neighbourhoods (c.f. Marston Citation2000) at the same scale in the city clearly shaped the stories about their neighbourhood that they shared. The barrier that the symbolic meaning of the neighbourhood creates in the horizontal space towards other neighbourhoods at the same scale, and in the hierarchical space towards the city as a whole (cf. Westlund, Rutten, and Boekema Citation2010), seems to strengthen the sense of local community in the District. As Westlund, Rutten, and Boekema (Citation2010) states, network exchange and formation of common norms and values within the demarcation is facilitated by borders and barriers, whereas the opposite holds for exchange over the borders. Thus, indicators of social sustainable development might, as Shirazi and Keivani (Citation2017) state, change when upscaling or downscaling the spatial focus. To some extent, this also explains why the discussion about the District is so black and white, torn between a negative image of the neighbourhood as insecure and marked by crime, and an extremely, almost overly positive image that on the contrary emphasises all that is good, often in contrast towards the rest of the city or towards other neighbourhoods. Living or working in the District means that you are forced to relate to the barriers that the bad reputation and differences in status create between the neighbourhood and the rest of the city, and become something of an ambassador for the District in your own way of talking about it, which several respondents admitted.

In the interviews, the District was not only understood in relation to the city, but the perceptions about the Districts were also clearly shaped by the relationships between different socio-economic vulnerable neighbourhoods in Sweden, at the same hierarchical level in relation to the cities of which they are a part. The municipal officials and the police officers talked about the development in the District as almost deterministic, where the District sooner or later will end up classified as a “vulnerable area”. There are clearly problematic aspects of making such connections, among other things, the “vulnerable areas” as a reference point seem to contribute to the stigma of the neighbourhood and strengthen the residents’ experience of not belonging to the city. At the same time, even though residents reported that they feel that they share experiences of discrimination and stigmatisation with people living in “vulnerable areas”, the connectedness to other stigmatised areas seemed to offer a feeling of affinity and solidarity and a possibility for identification. The identity of residents in a stigmatised neighbourhood often seems to take precedence over an overall, city-based sense of community higher up in the spatial hierarchy. The identity as a resident of the District is thus both territorial, in the sense that the District is the geographical area in which one lives, but it is also non-territorial because it is based on an identification that goes beyond a certain geographical sphere. The suburb is both a material place – the local residential area – and a symbolic place of identification. Spaces and scales are created by power relations (Born and Purcell Citation2006), and so does the feeling of community seem to be. We, therefore, place strong community spirit also at the national level in .

The conflicting views on crime, safety and trust

We identify crime, unsafety and insecurity as threats to a social sustainable development in the neighbourhood in this study. Crime, unsafety and insecurity in neighbourhoods (or rather the opposites) are considered as key aspects of social sustainability (Bramley and Power Citation2009; Shirazi and Keivani Citation2017; Weingaertner and Moberg Citation2014) and are therefore to be regarded as a threat to socially sustainable development, which must be taken seriously. In , therefore, this aspect is found on the far left of the socially sustainable development axis at neighbourhood level. At the same time, the residents described their neighbourhood as safe, or at least not more unsafe than the rest of the city. Therefore, we put safety and low criminality at neighbourhood level as a promoter for social sustainable development as shown in . Partly this could probably be understood as a way of resisting the external, generally negative image of the area that does not correspond to residents’ own experience, as we discussed in the section above. But these two conflicting images of the area that emerge – the dangerous and at the same time safe neighbourhood – also show the importance of asking for whom the neighbourhood is considered safe or unsafe. For people wearing traditional Somali or Kurdish clothes, the District can be perceived as a safer place than the rest of the city. Other issues are not at all named or framed as a safety or security issue, even though they probably should. When the respondents described how the District’s young people who look “foreign” are exposed to racist prejudice, this is not mentioned in terms of insecurity, although it probably affects the young people’s feeling of security when they move in public space. From a social sustainability perspective, unsafety is also considered harmful for the generalised trust (Dempsey et al. Citation2011). Mistrust against authorities in general and of the police in particular, especially among the residents who have immigrated from other countries, is identified by the Police as a problem in the District. If certain forms of insecurity are not named as such, then it will also be more difficult to see connections to questions such as trust. A related problem is the relatively widespread low trust in the authorities and the police in the District, which risks undermining confidence in society and democratic processes in general. Many of the groups that are not reached by the public service in the neighbourhood, as we have described, for example by not visiting the health centre when you have medical problems, risk only getting in touch with public services in the case of compulsory interventions, such as certain interventions by social services or the police. This risks fuelling a downward spiral of a lack of trust in the community.

Processes of exclusion and inclusion

Segregation and social exclusion are related to a number of aspects that are considered crucial for social sustainable development, such as social equity (Bramley and Power Citation2009; Shirazi and Keivani Citation2017), social cohesion and inclusion, equal opportunities, and equity, accessibility (Weingaertner and Moberg Citation2014) participation (Bramley and Power Citation2009; Shirazi and Keivani Citation2017; Weingaertner and Moberg Citation2014) and social inclusion and mix (Shirazi and Keivani Citation2017). In , segregation and social exclusion are visualised as a serious threat to socially sustainable development at different spatial levels.

At the neighbourhood level, some groups in the District are excluded from accessing certain support and services, which are available to others. This may be related to the fact that there are clear social and language barriers and what is described as cultural barriers in terms of trust in public institutions (cf. Westlund, Rutten, and Boekema Citation2010), dividing the District and making the distance to resources such as public services, opportunities, social networks and social capital discontinuous. In addition to inequality and segregation being problematic in itself, it can also contribute to reinforcing other problems, as the compensatory potential of public services and social networks is not used. This means that social segregation between groups in the District risks deepening even more. On the other hand, there are clearly also many examples of barrier brakers that enhance inclusion and cohesion in the District. One of the promoters for a social sustainable development in the district is the local civic society and associations, as seen in . From a social sustainable development perspective, civic society and networks are considered especially valuable. Bramley and Power (Citation2009) write about it in terms of participation in collective groups and networks in the community, Weingaertner and Moberg (Citation2014) as social capital and networks, and Shirazi and Keivani (Citation2017) as participation and civic society, social networking and interaction. The lively civic society in the District thus fulfils an important function as it creates networks and meeting places that enable meetings between different social groups and gives the District’s young people better alternatives than hanging out.

At the city level, living in the District sometimes means being excluded from opportunities that you would have if you lived in another neighbourhood. We see tendencies in the material that the exposed situation for several groups in the District is in a way normalised, or that they are not taken as seriously as they would have been in other neighbourhoods. Several respondents experience, for example, that there is too much focus on a small group of visible young people, especially young boys who are involved in crime. The focus on crime and social unrest has meant that other needs have been downgraded. This means that some children in the District suffer from double vulnerability – the exposed living conditions under which one lives, such as poverty and insecurity, mean that one is not granted the same rights as other children, precisely because one lives in an area where many others live in vulnerable situations.

At national level, the District, together with other stigmatised suburbs in Sweden, holds a special position as excluded from the rest of society. In the case of the District, perhaps the symbolic exclusion is the clearest. We have already described how the development in the District was interpreted in the context of a certain national discourse, and how the residents’ feelings of discrimination and stigmatisation exist side by side with feelings of community and affinity in relation to other suburbs. This is a good illustration of how processes that affect sustainability at one scale also affect sustainability at other scales (c.f. Wilbanks Citation2007) and the multiscalar character of social sustainable development (c.f. Shirazi and Keivani Citation2017).

Low involvement in municipal processes – but also well-functioning public services

Social sustainability can on the one hand be regarded as a condition that should be achieved and that can be operationalised with certain indicators, on the other hand, it can also be seen as a process (Boström Citation2012; Shirazi and Keivani Citation2017). Several dimensions or aspects of social sustainability can be said to constitute both procedural and substantive dimensions, like local democracy, participation and empowerment (Weingaertner and Moberg Citation2014), and democracy and participation (Shirazi and Keivani Citation2017). While concepts such as “democratic” can be an end in themselves for social sustainability, they can also be used to describe processes that lead to other aspects of social sustainability. The way in which social sustainability goals are achieved thus also has an intrinsic value for a democratic society.

The municipality undeniably invests and has invested in the District for a long time, such as in the outdoor environment and the library. Despite this, the respondents expressed a feeling of not being heard, and of only being the target for projects and initiatives they have not asked for or that is not always designed in consultation with those who are affected and who have a better understanding of the real needs. What was presented by municipal officials as a local influence on neighbourhood level was not perceived as such by local representatives. Instead, they experienced that they had no real influence or were excluded from the processes where the actual decisions are made. The perceived shortcomings in governance and co-determination in the municipal decision-making processes which are conveyed could be considered a serious threat to social sustainable development on city level, in . Some collaborative forums and meetings are described by some as a form of sham democracy, where no real rescaling of power (c.f. Richardson and Jensen Citation2003) from municipal level to neighbourhood level appears. The perceived reluctance to share real power from above, from representatives of the municipal administration and politics, creates a lack of trust from below, from representatives at the local level, and these processes strengthen the borders in the spatial hierarchy. But while lack of trust and unequal distribution of power function as barriers in hierarchical space, the professional horizontal space is not characterised by the same borders and barriers. On the contrary, the interviews contained many good examples of social sustainable processes within the District, between functions at the same spatial level. There seemed to be a high level of general trust between local professionals in different organisations, collaboration processes are established and often well-functioning, the staff talk well about each other and other organisations. Well-functioning public services are, therefore, found on the neighbourhood level, far to the right in .

Conclusions and policy implications

So, how should a city, from a social sustainability perspective, relate to neighbourhoods that are defined as at risk with regard to social sustainability? Our results show the need for an awareness of how different aspects of socially sustainable development relate to each other, by strengthening or counteracting each other. In addition, this awareness needs to be combined with an understanding that processes occurring at a particular scale only can be adequately understood when considered in relation to other scales.

At the neighbourhood level, we have raised issues of crime, unrest and unsafety and segregation and social exclusion as threats towards social sustainable development. Our results also illustrate several examples of efforts to meet these threats, such as community policing with a focus on relationship-building work in the area. From another scalar perspective, however, these efforts seem to reinforce other threats to social sustainable development, such as further stigmatisation of the neighbourhood, which in the long run, can contribute to increased segregation at the city level. Furthermore, our results indicate that neighbourhood projects or initiatives initiated on city level political scale, despite good intentions, can have the opposite effect if processes and decisions are not anchored on a local scale or are perceived as undemocratic. The efforts at the city level can come from the very best intentions, but if you feel like you are not a part of the city, the efforts will not affect you. In a similar way, a neighbourhood’s stigmatised position in a city can increase the residents’ sense of community in the neighbourhood in resistance towards this stigmatisation – which in turn can increase segregation in the city and thus reinforcing a negative spiral.

A city that is seriously interested in social sustainable development must recognise threats as the responsibility of the entire city – regardless of where in the city the problems are manifested. Investments at the neighbourhood level can admittedly mitigate the consequences of, for example, the city segregation, but to reduce segregation itself, rescaling in the understanding of the problem is required. Scalar strategies could be used rhetorically and in practical policies by the city – if there is a political will to do so. If the problems are recognised as a responsibility of the whole city, the city has the opportunity to influence even the structures that can contribute to a solution. If, on the contrary, problems continue to be framed as a neighbourhood problem, there are small chances of solving them.

In summary, our results clearly show that neighbourhood social sustainability cannot be studied or acted upon without being put in a context of spatial scale. Without this awareness, social sustainability could be defined as almost anything, and the responsibility for sustainable development can be placed at a spatial scale that does not have the political power to change it. For policy makers, practitioners and researchers aiming to promote social sustainable development at city and neighbourhood levels, there is a need for acknowledging that there are no “magic bullet solutions”. Rather, actions and interventions must embrace complexity, and acknowledge the risk for counteracting processes. Interventions that build on local identified threats and promoters and are carried out in a truly top-down/bottom-up approach, evidently have better potential to succeed in its ambitions. Local threats need to be identified in a mutual understanding between local residents and societal actors, in order to form the basis for interventions with broad community acceptance and support. However, equally important as identifying local threats, is to build on and use existing local promoters in any action to support social sustainable development.

Declaration of interest statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (20.4 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (2.6 MB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Andersson, R., and Å Bråmå. 2004. “Selective Migration in Swedish Distressed Neighbourhoods: Can Area-Based Urban Policies Counteract Segregation Processes?” Housing Studies 19 (4): 517–539. doi: 10.1080/0267303042000221945.

- Andersson, R., A. Bråmå, and E. Holmqvist. 2010. “Counteracting Segregation: Swedish Policies and Experiences.” Housing Studies 25 (2): 237–256. doi: 10.1080/02673030903561859.

- Born, B., and M. Purcell. 2006. “Avoiding the Local Trap – Scale and Food Systems in Planning Research.” Journal of Planning Education and Research 26 (2): 195–207. doi: 10.1177/0739456 ( 06291389.

- Boström, M. 2012. “A Missing Pillar? Challenges in Theorizing and Practicing Social Sustainability: Introduction to the Special Issue.” Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy 8 (1): 3–14. doi: 10.1080/15487733.2012.11908080.

- Bramley, G., and S. Power. 2009. “Urban Form and Social Sustainability: The Role of Density and Housing Type.” Environment and Planning B-Planning & Design 36 (1): 30–48. doi: 10.1068/b33129.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brenner, N. 1998. “Between Fixity and Motion: Accumulation, Territorial Organization and the Historical Geography of Spatial Scales.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 16 (4): 459–481. doi:10.1068/d160459

- Clarke, A. E. 2003. “Situational Analyses: Grounded Theory Mapping After the Postmodern Turn.” Symbolic Interaction 26 (4): 553–576. doi: 10.1525/si.2003.26.4.553.

- Commission, European. 2020. “European Social Progress Index.” https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/information/maps/social_progress2020/.

- Creswell, J. W., and C. N. Poth. 2016. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches. Sage publications.

- Dahlstedt, M., and V. Lozic. 2017. “Managing Urban Unrest: Problematising Juvenile Delinquency in Multi-Ethnic Sweden.” Critical and Radical Social Work 5 (2): 207–222. doi: 10.1332/204986017 ( 14933953111175.

- Delaney, D., and H. Leitner. 1997. “The Political Construction of Scale.” Political Geography 16 (2): 93–97. doi:10.1016/S0962-6298(96)00045-5

- Dempsey, N., G. Bramley, S. Power, and C. Brown. 2011. “The Social Dimension of Sustainable Development: Defining Urban Social Sustainability.” Sustainable Development 19 (5): 289–300. doi: 10.1002/sd.417.

- Eriksson, M., A. Santosa, L. Zetterberg, I. Kawachi, and N. Ng. 2021. “Social Capital and Sustainable Social Development – How Are Changes in Neighbourhood Social Capital Associated with Neighbourhood Sociodemographic and Socioeconomic Characteristics?” Sustainability 13 (23): 13161. doi:10.3390/su132313161

- Hanberger, A., and J. Lindgren. 2021. Utvärdering av “Umeå Växer Tryggt och Säkert”– Slutrapport [Evaluation of the Municipal Program Umeå Växer Tryggt och Säkert]. Umeå: Umeå universitet.

- Hansen Löfstrand, C. 2015. “Private Security Policing by ‘Ethnic Matching’ in Swedish Suburbs: Avoiding and Managing Accusations of Ethnic Discrimination.” Policing and Society 25 (2): 150–169. doi:10.1080/10439463.2013.817996

- Jessop, B. 1996. “Post-Fordism and the State.” In Comparative Welfare Systems. The Scandinavian Model in a Period of Change, edited by B. Grev, 165–183. London: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-24791-2.

- Lefebvre, H. 1991. The Production of Space. Cambridge: Blackwell.

- Lozic, V. 2018. “Att Lära av det Lokala och Experimentera: Resilienstänkande i Brottsförebyggande Arbete. [Learning from the Local and Experimenting: Resilience Thinking in Crime Prevention Work].” Arkiv. Tidskrift för Samhällsanalys 9: 129–157. doi:10.13068/2000-6217.9.5

- Marston, S. A. 2000. “The Social Construction of Scale.” Progress in Human Geography 24 (2): 219–242. doi:10.1191/030913200674086272

- McCann, E. J. 2003. “Framing Space and Time in the City: Urban Policy and the Politics of Spatial and Temporal Scale.” Journal of Urban Affairs 25 (2): 159–178. doi:10.1111/1467-9906.t01-1-00004

- NOA. 2017. Utsatta områden – Social ordning, kriminell struktur och utmaningar för polisen [The Swedish Police Authority, The National Operations Department. Vulnerable areas - Social order, criminal structure and challenges for the police]. Nationella operativa avdelningen, underrättelseenheten.

- Polit, D. F., and C. T. Beck. 2010. “Generalization in Quantitative and Qualitative Research: Myths and Strategies.” International Journal of Nursing Studies 47 (11): 1451–1458. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.06.004.

- Richardson, T., and O. B. Jensen. 2003. “Linking Discourse and Space: Towards a Cultural Sociology of Space in Analysing Spatial Policy Discourses.” Urban Studies 40 (1): 7–22. doi:10.1080/00420980220080131

- Santosa, A., N. Ng, L. Zetterberg, and M. Eriksson. 2020. “Study Protocol: Social Capital as a Resource for the Planning and Design of Socially Sustainable and Health Promoting Neighborhoods – A Mixed Method Study.” Frontiers in Public Health 8, doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.581078.

- Shirazi, M. R., and R. Keivani. 2017. “Critical Reflections on the Theory and Practice of Social Sustainability in the Built Environment - a Meta-Analysis.” Local Environment 22 (12): 1526–1545. doi: 10.1080/13549839.2017.1379476.

- Shirazi, M. R., and R. Keivani. 2019. “The Triad of Social Sustainability: Defining and Measuring Social Sustainability of Urban Neighbourhoods.” Urban Research & Practice 12 (4): 448–471. doi:10.1080/17535069.2018.1469039

- Umeå Municipality. 2020. Umeås stadsdelar – så står det till! Sociala stadsrumsanalyser och stadsdelsbeskrivningar som underlag till gestaltning av livsmiljöer för välbefinnande, tillit och trygghet [Umeå's Districts – That's How It Is! Social Urban Space Analyzes and District Descriptions as a Basis for the Design of Living Environments for Well-Being, Trust and Security].

- WCED. 1987. Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future.

- Weingaertner, C., and Å Moberg. 2014. “Exploring Social Sustainability: Learning from Perspectives on Urban Development and Companies and Products.” Sustainable Development 22 (2): 122–133. doi:10.1002/sd.536

- Westlund, H., R. Rutten, and F. Boekema. 2010. “Social Capital, Distance, Borders and Levels of Space: Conclusions and Further Issues.” European Planning Studies 18 (6): 965–970. doi:10.1080/09654311003701506

- Wilbanks, T. J. 2007. “Scale and Sustainability.” Climate Policy (Earthscan) 7 (4): 278–287. doi:10.3763/cpol.2007.0713.

- Woodcraft, S. 2012. “Social Sustainability and new Communities: Moving from Concept to Practice in the UK.” Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 68: 29–42. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.12.204