ABSTRACT

The former neglect of social sustainability as an ideal for urban development has been exchanged with a newfound interest globally, nationally and locally. However, there is little systematic knowledge to support relevant priorities in urban governance. Motivated by this knowledge gap, this paper reviews new knowledge from a literature study seeking to identify context-situated definitions and operationalisations of community social sustainability. Two distinct research waves are identified: a first wave of categorisation defining conceptual ground structures of community social sustainability; a second wave of operationalisation highlighting how these ground structures contain competing concerns and dilemmas. This paper nuances and further distinguishes social sustainability at the community level by combining insights from these two contributions to research. Community social sustainability appears as a continually emergent and contested phenomenon. How to address and reconcile competing concerns baked into social sustainability as a concept and a policy still is a burning issue for research and practice.

Sustainable development “ … meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”. (WCED Citation1987)

1. Introduction

Social sustainability was for long a neglected dimension of sustainable development, both in research and practice (Vallance, Perkins, and Dixon Citation2011; Eizenberg and Jabareen Citation2017; Opp Citation2017). A shift in attention has however taken place during the last decades. Partly in response to a stronger awareness of the social consequences of climate change. In particular the unequal distributive effects of policies of climate transformation geographically and socially (Eizenberg and Jabareen Citation2017; European Commission Citation2019). Partly due to the UN Agenda 2030 and the embracement across nations, cities, companies and organisations of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which firmly raise social and equity issues (United Nations Citation2015; Bulkeley Citation2021). Inspired by this new, twofold awareness, this paper sets out to expand our understanding of social sustainability in a community setting by exploring and identifying context-situated definitions and operationalisations.

In the history of sustainable development, much emphasis is devoted to the local level – from the Brundtland Commission’s report, via Local Agenda 21 to the SDGs (WCED Citation1987; Hom Citation2002; United Nations Citation2015). SDG 11 follows suit and is specifically devoted to making cities and communities inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable. A key motivation for these policy initiatives is that cities account for 55% of the population and produce 85% of the global GDP but also 75% of the greenhouse gas emissions (Vaidya and Chatterji Citation2020). Thus the issues of global sustainability cannot be addressed without strongly addressing sustainability at the urban scale (ibid).

Despite increased attention to the urban community level as a core setting for social sustainability action, there is a recognised need for deeper, more nuanced and specific knowledge of what social sustainability means in an urban community context (Dempsey et al. Citation2011; Medved Citation2017; Shirazi and Keivani Citation2019; Shirazi et al. Citation2020). Cities seeking to operationalise social sustainability into meaningful concepts and practical instruments find little guidance (Eizenberg and Jabareen Citation2017; Koch and Krelleberg Citation2018; Medved Citation2018; Shirazi et al. Citation2020; Larimian and Sadeghi Citation2021). Current knowledge of social sustainability is described as “chaotic” (Vallance, Perkins, Dixon Citation2011); “undefined, inapplicable and utopian” (Eizenberg and Jabareen Citation2017) and “nebulous” (Dempsey, Brown, and Bramley Citation2012), referring to the concept’s range of dimensions and the lack of agreed definition.

Stimulated by this knowledge gap, this paper presents a literature studyFootnote1 of scientific publications that relate various aspects of social sustainability to the physical and material context of a community. Previous research contributions have successfully provided an overview of existing research by summarising the variety and multiple meanings of social sustainability in urban communities (see, e.g. Weingartner and Moberg Citation2011; Eizenberg and Jabareen Citation2017; Larimian and Sadeghi Citation2021; Shirazi et al. Citation2020). Representing a complementary contribution, this literature study gives a consolidated and nuanced expression of community social sustainability through a qualitative meta-analysis, i.e. an iterative and systematic evaluation of existing research establishing a robust and relevant body of research (Shirazi and Keivani Citation2019). Accordingly, the literature study seeks, first, to identify a common conceptual understanding of community social sustainability. Second, to establish an operational understanding delving into tensions and dilemmas that may arise when seeking to implement social sustainability in a given community.

A collected, evaluated, analysed and synthesised data set of peer-reviewed social-scientific publications from 2010–2020 represents the empirical basis of the study.

2. Identifying a relevant and robust body of research

Literature studies are particularly useful for concepts like community social sustainability, where both the definition of core concepts and the relationship between key variables are uncertain (Dacombe Citation2018). Intending to alleviate this uncertainty, the literature study presented here concentrates on contributions explicitly relating to social sustainability and a physical-material community context. Research fields identified to have a miniscule contribution to the exact coupling of these two elements may still contain robust research on either social sustainability or community development. However, if they do not make an explicit linkage between social sustainability and the physical-material community context, they are irrelevant for this exact study. With this limitation in mind, we turn to the steps taken to identify a relevant and robust data set.

2.1. Data collection: inclusion criteria, literature search and information gathering

To capture contributions to research that explicitly link social sustainability and the community context, the literature search concentrated on articles including the following concepts:

Social sustainability

Local communities/development of local communities/processes in local communities.

Furthermore, the following inclusion criteria guided the search:

Peer-reviewed publications in the last 10 years (2010–2020)

Contributions in the languages: English, Norwegian, Swedish and Danish

Databases containing research published in both geography, local community development, socio-economic, and other social scientific perspectives

2.2. Data evaluation: exclusion criteria and quality assessment

The evaluation of peer-reviewed articles was an iterative, non-linear screening process consisting of several readings of abstracts, uploaded to NVIVO, and coded in categories informed by the main theme of the abstract. It involved four steps that continuously reduced the number of relevant contributions.

To secure a scientifically sound and relevant data set, the first round of evaluation formulated a set of criteria excluding the following contributions:

Studies with empirical data outside the Global North’s socio-political and economic sphere, unless they are considered particularly relevant to Nordic conditions

Contributions containing data from older historical periods (seventeenth/nineteenth century)

Specific empirical phenomena irrelevant to a Nordic community context – for example cooperatives, mass-tourism (both wanted and unwanted), inter-religious dialogue, small-scale rural festivals, cultural-historical sites, forestry, fishing, agricultureFootnote2

Contributions with emphasis on technical methodological development, and internal organisational issues (“supply chain management”, “value chains”)

Papers for scientific or professional conferences (conference papers) and master’s theses, for reasons of quality.

When these “ground rules” were set, the second round of evaluation assessed whether the content of the articles within a topic was relevant to our purpose. That is, whether the research helps to identify some of the following aspects:

variables that define and operationalise social sustainability

the connection between social sustainability and the local physical, cultural, geographical, and institutional context

how planning, participation and co-creation can contribute to promote social sustainability.

In sum, the identification of relevant and robust studies enables deeper data analysis and interpretation of a manageable and relevant data set, as well as rendering it possible to identify the research front’s knowledge gaps. This second evaluation reduced the data set to 202 articles.

The third round of evaluation followed a new and important methodological approach (Petticrew and Roberts Citation2006), by engaging municipal employees in three cities – one sustainability advisor, three public health advisors and one urban planner. Their input provided important direction to the evaluation, by highlighting the importance of dilemmas and tensions in socially sustainable community development, and the need for more knowledge on governance and co-creation to include groups of the population seldom participating in such processes. This reduced the size of the dataset to 108 units.

The fourth and last round of evaluation coded each of the 108 article abstracts according to their ability to illuminate and contribute knowledge to the inclusion and exclusion criteria plus key issues raised by the practice field. In addition, an assessment was made of the articles in the omitted categories to double check their relevance for the literature study and their linkage to the remaining main categories, which resulted in the movement of some contributions from one theme to another in the third and fourth round of evaluation. After the last evaluation, we had a relevant and robust data set of 50 articles ready for deeper analysis. gives an overview of the evaluation process.

Table 1. Main themes and number of articles at different stages of the evaluation process.

The analytical task of distributing the articles according to these elements is not straightforward. The same article often addresses several themes and dimensions. Yet in sum, the data set identifies key conceptual discourses, relevant categorisations and tensions and dilemmas between competing concerns when seeking to operationalise social sustainability to a community setting.

2.3. Impressions from the evaluation process: general trends in community social sustainability research

The first evaluation weeded out irrelevant articles gave a general picture of the research landscape and opened for a preliminary evaluation to identify general patterns in parts of the literature meeting our most basic criteria. It shows how research on community social sustainability generally concentrates on the following themes:

Conceptual development related to specific values (social justice, health, well-being)

Indicator development

Urban change processes as urban transformation, urban planning, densification, infrastructure development and construction

Accessibility to various facilities such as housing, transport, and green lungs: how they are distributed across groups and geographies and affected by physical changes, and how these facilities should be developed to strengthen social sustainability.

As previous literature studies have found, social sustainability is an inherently normative enterprise, informed by normative values, ideas and ethics that shape the very question of what it means and what should be done (Shirazi et al Citation2020; Eizenberg and Jabareen Citation2017). Combined with the fact that the research field is disciplinarily scattered, this may explain the multiplicity of suggested social sustainability factors and the variety of approaches. The list above indicates that social sustainability requires a mix of physical and non-physical factors. The exact composition and categorisation of these factors have historically had theoretical and practical deficiencies, begging the question of what to include in the concept, and what to incorporate into governance and planning (Larimian and Sadeghi Citation2021).

Social sustainability is conceived as a highly complex conceptual and practical endeavour seeking to reconcile and fulfil multiple, potentially competing goals. Contributors to the field however argue that this conceptual and practical vagueness makes the concept flexible and fluid enough to enable dialogue and continuous development in the face of new challenges (Shirazi and Keivani Citation2019, 217; Shirazi et al. Citation2020, 3). The other side of the coin is that the vagueness makes social sustainability hard to measure (Eizenberg and Jabareen Citation2017, 3), which have motivated research to find useful indicators for social sustainability at an urban scale. This quest for measurement frameworks is performed at the backdrop of two important shifts in social sustainability research that are visible also in this study. A shift from “macro” (regional and urban) to “micro”-level studies (community and neighbourhood) (Larimian and Sadeghi Citation2021; Shirazi et al Citation2020) and from hard (employment and poverty reduction) to soft issues (sense of place, identity, social participation, etc.)

One factor, social justice, receives especially extensive attention in the literature. Nearly half of the articles in our final data set address social justice as a key value for community development. Especially social research has managed to localise questions of social distribution and quality of life. Planning research on the built environment to a certain extent raises social issues. But governance/political science research seldom addresses social sustainability in a community setting. There is a knowledge gap concerning social and distributive aspects of a community’s institutional set-up, and the unique democratic concerns raised by social sustainability issues. This resonates with the knowledge needs formulated by the practitioners engaged in the evaluation process.

When looking at the final data set as a whole, two distinctive “waves” in community social sustainability research are discernible. The first wave seeks to categorise community social sustainability by identifying and arranging crucial aspects and characterising them by defining key concepts. The second wave seeks to operationalise community social sustainability by empirically exploring and investigating practical implementation of social sustainability ideals in a community context. This strain of literature gives insight into tensions and dilemmas of community social sustainability practices. The following two sections present and discuss key patterns, arguments and results within the frames of these research waves.

3. Categorising social sustainability in a community context

One of the contributions in the data set, Dempsey et al. (Citation2011)'s article “The social dimension of sustainable development: Defining urban social sustainability”, has had a significant influence on research by explicitly relating the built environment on the one hand and various social sustainability variables on the other. Their identification of two core dimensions that they argue make up the ground structure of community social sustainability is a key reference in the field. It captures the complexity of community social sustainability yet organises the concept into meaningful dimensions providing understanding and guidance to urban development. When exploring key contributions to the first wave of community social sustainability research, these dimensions will be used as organising principles.

3.2. Socially just accessibility to benefits and absence of burdens

The first dimension, socially just accessibility, underlines the importance of accessibility to various goods, services and facilities in the community, and the distribution of these goods within and between communities (Dempsey et al. Citation2011). Social justice furthermore refers to a fair distribution of resources and to avoid exclusionary or discriminatory practices, allowing all residents to participate fully in society, socially, economically, and politically (Dempsey et al. Citation2011, 292; Dempsey, Brown and Bramley Citation2012, 94). As shows, social justice is a main pillar of community social sustainability, explicitly referred to by 23 articles. Opp (Citation2017, 291) formulates why social justice is a core value in a representative way by expressing that:

A community is not socially sustainable if a subset of the population faces a greater exposure to environmental harms or is less able to enjoy or to access the benefits of public investment.

In a geographical context, social injustice is visible through characteristic deprivation factors; poor residential areas, limited access to public services and facilities, poor quality of amenities and facilities, but also a lower voter turnout in political elections and limited integration in political processes concerning own community (Dempsey et al. Citation2011, 292; Dempsey, Brown, and Bramley Citation2012, 97). The degree of exclusion and discrimination is relative to other communities in the city or comparable communities elsewhere, and interventions often aim to equalise access to services and facilities across geographical areas (Dempsey, Brown, and Bramley Citation2012, 97). summarises key categories and factors related to socially just access.

Table 2. First dimension of community social sustainability - main categories and distinguishing factors.

3.3. The sustainability of local communities

The sustainability of local communities highlights the collective aspects of a community’s social life, which is difficult both to measure and to plan for (Dempsey, Brown and Bramley Citation2012; Eizenberg and Jabareen Citation2017; Opp Citation2017). Focus is on the communities’ capacity to maintain and reproduce itself at an acceptable level of functioning in terms of social organisation, and the integration of individual social behaviour in a wider social collective (Dempsey et al. Citation2011, 293; Dempsey, Brown and Bramley Citation2012, 94). Hence, one may understand a community’s social sustainability as its viability and independence, which consists of several different qualities, summarised by Dempsey et al. (Citation2011, 293–297), and confirmed and further developed by among others (Opp Citation2017; Shirazi et al. Citation2020):

Social capital, emphasising the relations between inhabitants of a community is a prerequisite for the sustainability of a community. Local communities that are rich in social capital, one will see that the social ties contribute to creating trust, mutual actions, and spontaneous cooperation, which strengthens the social cohesion of the community. Social capital and social cohesion are according to the authors not necessarily positive in all respects. It depends on how broad and inclusive these ties are – close ties encompassing only subsets of the local community can have exclusionary effects and reduce trust between different parts of the community.

Social networks further capture the exercise of social capital in practice through actual participation in organised activities. From engaging in an organisation or a time-limited action to participating in formal political processes and elections.

Stability ensures social continuity and belonging, while a high degree of social mobility reduces a place's social sustainability. The mobility in and out of a neighbourhood can be a measure of perceived quality and care for the living environment, how to assess the availability of services and facilities, and whether the neighbourhood offers the desired mix of the type and size of the homes.

Identity and belonging express people’s affiliation with their neighbourhood and their feeling of having the right to belong. Common norms and codes of conduct may support qualities that people are concerned about, and give birth to pride, identity and belonging. When residents have a high sense of attachment to their neighbourhood, they are more likely to continue to live there and engage themselves in its conservation.

Safety and security highlight the fulfilment of some basic needs for a place to be socially sustainable. People depend on feeling safe in the areas they live, and this entails both internal and external threats, including protection against crime and traffic safety. A safe and secure community supports the development of trust and reciprocity between the members of the local community. Conversely, if a place struggles with crime, dilapidated and littered areas, it can easily end up in a negative spiral where small negative changes stimulate more antisocial behaviour and criminal acts.

summarises key categories and factors related to “the sustainability of local communities”.

Table 3. Second dimension of local social sustainability main categories and distinguishing factors.

The dimensions “socially just accessibility” and “the sustainability of local communities” identified by Dempsey et al. (Citation2011) and explored by other scholars in the field are theoretical ideals. Turning to the identified second wave of community social sustainability research, the remaining part of the paper will show how recent contributions to the literature helps to disentangle and further nuance the two dimensions of community social sustainability presented above.

4. Operationalising community social sustainability

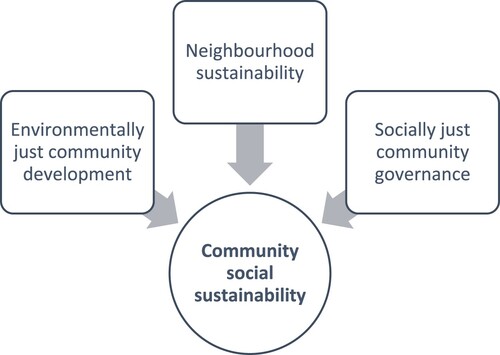

Contributions to the second wave of research highlight tensions and dilemmas baked into the social sustainability ideal when operationalised in a community setting. To clarify crucial concerns and capture key contradictions, I suggest that community social sustainability may be organised as three different elements, as illustrated by , and used as an organising principle for discussing contributions to the second research wave.

An interesting pattern comes to the fore when reviewing the overall dataset. Several articles explore exactly the linkage between maintaining a local community’s sustainability on the one hand, and progressively reforming both its physical features and its governance processes to secure social justice on the other. This double mission of social sustainability activates two interlinked, yet distinct elements of social justice: socially just community governance and environmentally just community development. Socially just community governance sets focus on social justice as a vehicle for securing socially inclusive governance of local communities. This involves developing governance institutions and processes capable of including multiple and potentially competing interests. Environmentally just community development sets focus on social justice as a developmental guideline for the physical environment that ensures socially just access and distribution of goods, resources, and harms for present and future generations. In some articles, this division is directly expressed (Eizenberg and Jabareen Citation2017, 6; Opp Citation2017), in others the reference to this twofold notion of justice is an inherent part of their suggested conceptual understanding of social sustainability (Vallance, Perkins and Dixon Citation2011).

Contributions to the second wave of research also help to elaborate and unpack the “social sustainability of local communities” dimension further, summarised into the concept neighbourhood sustainability. It underlines how a community’s traditions, values and practices are an integrated part of social sustainability and are inspired by an intensively referred to and ground-breaking contribution by Vallance, Perkins and Dixon (Citation2011). I will further elaborate key issues raised within the three aspects of community social sustainability below.

4.1. Neighbourhood sustainability

The attraction of Vallance, Perkins and Dixon’s (Citation2011) contribution lies in how they emphasise an often-overlooked element of people’s quality of life – the value of the community as it is. The authors call this “maintenance social sustainability” and argue that it:

… speaks to the traditions, practices, preferences and places people would like to see maintained (sustained) or improved, such as low-density suburban living, the use of the private car, and the preservation of natural landscapes. (Vallance, Perkins and Dixon Citation2011:344)

A community is not, however, a monolithic entity where all share the same values and aspirations. Rather, people hold different values and beliefs about the way their community may sustain the quality of life for their members (Dassen, Kunseler and van Kessenich Citation2013, 195). Carving out mutual notions of a sense of place is thus highly subjective, value-laden and exposed to continuous reinterpretation and development. A first step when seeking to maintain neighbourhood sustainability is thus also to create awareness and insight into existing, potentially contradicting, value orientations and practices in the community (ibid.).

4.2. Socially just community governance

The second element of community social sustainability proposed here relates exactly to the co-existence of multiple values, interests, and ways of living in a community, and the reflection of this complexity in plans and processes for community development. Of interest is the degree to which governance institutions and planning processes concerning the community are politically and socially inclusive (Vallance, Perkins and Dixon Citation2011; Dassen, Kunseler and van Kessenich Citation2013; Eizenberg and Jabareen Citation2017; Franklin and Dunkley Citation2017; Opp Citation2017; Medved Citation2017, Citation2018; Kohon Citation2018; Trudeau Citation2018). According to Opp (Citation2017, 298)

Social sustainability requires that all populations in a community have equal access and be able to participate in the local political process wherever possible.

In community governance processes, some actors influence such priorities more than others; those with agenda setting authority and/or resources that the community are dependent on to be able to function and develop. This “development community” consists of various actors, such as architectural firms, public planners, politicians, developers, consultants, and philanthropic organisations (Trudeau Citation2018, 603; Johanson Citation2015). Ideally, these actors put social inclusion on the agenda, and take steps to regulate processes and results for the best of most inhabitants in the community. Often, however, planners are incapable of translating communities’ needs and demands into planning decisions, and those in power are generally unwilling to relinquish their control over decision-making despite being the initial initiators of broader participatory processes (Eizenberg and Jabareen Citation2017, 4). All is not lost, however, if the development community is unable to create inclusive processes with real impact on the outcome. Trudeau (Citation2018) argues that other actors may exert pressure on the development community. They may exert direct pressure by raising necessary capital or ensuring support for new regulations; execute indirect influence by setting the agenda to prioritise equity through formulating benchmarks for goal realisation; and finally exert hegemonic influence by developing a social equity narrative capable of framing a given development (Trudeau Citation2018, 604).

Independently of which actor is the first mover to prioritise social justice, Medved (Citation2017, Citation2018) and Trudeau (Citation2018) argue that a key prerequisite for this ideal to influence community governance and planning, is to integrate it as a principle from the outset of the process – providing a mutual, visionary platform for community development. A key challenge raised by these contributions is that neither political representatives of the community nor civil society organisations are representative of the community as such. They seldom reach (out to) marginalised groups, which often do not have organisations or other leadership structures representing them.

4.3. Environmentally just community development

We have seen that a key aspect of social sustainability is equal opportunity to access a broad range of amenities, goods, and resources in the community, and to avoid harms and burdens. This notion of social justice creates a linkage between the physical context of the community and its environmental sustainability, as access to goods/avoidance of burdens depends on upholding necessary resources over time, for present and future generations (Dempsey et al. Citation2011; Vallance, Perkins and Dixon Citation2011; Opp Citation2017; Eizenberg and Jabareen Citation2017; Trudeau Citation2018; Medved Citation2018). The literature thus makes an explicit reference to how social and environmental sustainability is mutually related. Present access to, and distribution of, resources, services and opportunities in the community lay the foundation and significantly influence the ability of future generations to acquire the same level of resources and amenities (Opp Citation2017, 287; Dassen, Kunseler and van Kessenich Citation2013, 195). Environmentally just community development is thus about reconciling and combining intragenerational and intergenerational equity. Eizenberg and Jabareen (Citation2017, 8) define intergenerational equity as “ … fairness in allocating resources between current and future generations”, while intragenerational equity is defined as “ … fairness in allocating resources between competing interests at the present time”. Consequently, to ensure environmentally just community development involves securing a better quality of life for all and avoiding ecological and spatial inequalities now and in the future (Opp Citation2017, 287; Shirazi et al. Citation2020, 3).

Climate change is a special case in point. Eizenberg and Jabareen (Citation2017, 6) underline that within all societies, certain individuals and groups are particularly vulnerable and cannot adapt to climate change. As a problem whose consequences become continuously more severe over time, climate change accentuates the importance of including intergenerational equity as a part of our understanding of environmental justice. Building awareness of environmental ethics and ecological sustainability is an inbuilt part of environmentally just community development, i.e. modes of consuming, producing, and gaining values in socially and environmentally responsible ways, either through incremental or more radical transformative change in ideas and actions (Vallance, Perkins and Dixon Citation2011, 344; Eizenberg and Jabareen Citation2017, 10). The quality of the local environment is not only important for ecological health; it also influences people’s values and sense of place. A change in land use, as the transformation of a former contaminated area into a community park, may create a corresponding positive shift in life quality for individuals or even the community as such (Kohon Citation2018, 15).

Several contributions in the dataset refer to a planning movement that emerged in the 1980s in the USA called “New Urbanism” which aimed to develop a new agenda for urban development (Arundel and Roald Citation2017, Kyttä et al. Citation2016; Medved Citation2017; Trudeau Citation2018). The goal was to reduce urban sprawl in American cities that led to scattered settlement, car dependence, one-sided, zoned, land use and racial segregation. They suggested a set of alternative design principles promoting human-friendly, dense urban development through walk-friendly streets, a mixed land use with housing and commercial and cultural activities that facilitate urban life, densification and less car dependence (Medved Citation2017; Arundel and Roald Citation2017). Over time, this urban, “compact city” form has become a prevailing operationalisation of “good planning” that ensures the curbing of GHG emissions through sustainable transport and energy solutions, and at the same time ensures socially and economically vibrant communities (Hofstad Citation2012; Eizenberg and Jabareen Citation2017). However, it is criticised for failing to consider social needs, most notably affordable housing (Trudeau Citation2018, 603; Andersen and Skrede Citation2017; Hofstad Citation2012).

Research, mainly North American studies, conclude that there exists a “compact-city paradox”: while a compact urban environment is ecologically sustainable, it is detrimental to social sustainability understood as liveability and quality of life (Mouratidis Citation2018a, 2409). Several articles explore whether this compact city paradox is valid in a Nordic context. They conclude that Nordic cities have not accumulated the same degree of negative neighbourhood factors and that the social effect of densification, in general, are positive (Mouratidis Citation2018a, Citation2018b, Citation2019; Ala-Mantila et al. Citation2018; Kyttä et al. Citation2016). Corresponding positive correlations between compactness and social sustainability are found in other North-European cities (Arundel and Roald Citation2017, 49). A general argument of these contributions is that if compact cities make sure to have good and accessible services, facilities and green areas and have low exposure to noise, traffic, littering and crime, compact urban development is not only environmentally sustainable, but also socially sustainable. Kyttä et al. (Citation2016, 52) put it this way:

… an optimal level of urban density can be found where access to services and facilities can be guaranteed without overwhelming urban problems such as pollution and traffic congestion (…) Possible measures can include investments in accessibility by walking and cycling as well as a careful consideration of those services that best facilitate smooth everyday life.

3. Community social sustainability: potential tensions and dilemmas

At the intersection of the three suggested elements of community social sustainability, are dilemmas that force decision-makers to make hard priorities among important yet competing goals. A mutual message from research is that these dilemmas need to be acknowledged and handled if cities and communities are to make social sustainability a guide for community development. Let’s explore these dilemmas in more detail.

5.1. Environmentally just community development versus neighbourhood social sustainability

Several contributions address a persistent dilemma at the intersection between creating environmentally just community development on the one hand and preserving neighbourhood social sustainability on the other (Vallance, Perkins and Dixon Citation2011; Johanson Citation2015; Kohon Citation2018; Franklin and Dunkley Citation2017; Dassen, Kunseler and van Kessenich Citation2013). At stake is to create a predictable, environmentally and climate-sound strategy for community development at the same time as one manages to maintain and include traditions, values and practices that are dear to the local community.

Vallance, Perkins and Dixon (Citation2011, 345) argue that communities often mobilise against planned land use changes that influence their habits and traditions. To avoid that such policies become counterproductive, it is important to understand the reasons behind the resistance to succeed in achieving and implementing climate and environmental measures. The authors underline that ideals of environmentally sustainable and climate-friendly local communities are near utopian and require deep transformations that break with sedimented practices. An example is how new urbanism ideals of compact city-inspired development set mobility patterns, sense of place and social relations under pressure.

The contributions to this discourse consent that a viable path when approached with such tensions is to ensure that people with different identities can read themselves into the vision/process by creating an inclusive, rather than exclusive, understanding of community sustainability (Vallance, Perkins and Dixon Citation2011; Dassen, Kunseler and van Kessenich Citation2013; Franklin and Dunkley Citation2017; Kohon Citation2018). An important aspect is the framing and labelling of strategies and projects, formulated in this way by Franklin and Dunkley (Citation2017, 1513):

The continued shorthand use of a green identity-based approach by government, funding councils, media organizations, and many other external bodies, as a way of seeking out and categorizing community projects and groups, is (…) increasingly problematic.

5.2. Socially just community governance versus neighbourhood social sustainability

Negotiating the limits of inclusion and manage negative externalities of deviant behaviour is a challenge not only at the intersection between environmental justice and neighbourhood social sustainability but also when looking specifically at the social aspects of community development. Neighbourhood values and practices may feel challenged by minorities with deviant lifestyles, i.e. groups of people who are not members of the dominant or power-holding population, such as immigrants, low-income residents, renters, people experiencing substance abuse or mental health problems, and older adults with mobility constraints (Kohon Citation2018, 18). In her study, Kohon (Citation2018, 18) finds that community leaders’ struggle to be inclusive. At times, social inclusion and justice conflict with other community goals related to social sustainability, such as health, safety, public participation, and healthy child development. Community governance is charged with the dilemma of balancing the need for continuous awareness of social inclusiveness with nurturing a sense of belonging (Kohon Citation2018, 19). At stake is whose values and practices to accept as part of the community. This question is especially challenging in a community context where stakeholders often lack necessary skills to think outside hegemonic values and practices, and where minority interests are weakly organised and voiced (ibid).

Building communities capable of being both accessible across geographies and social groups and preserving values and practices at the same time require negotiating and reinterpreting the concept of inclusion. Kohon (Citation2018, 21) raises several crucial questions about this matter:

What are the limits of inclusion? Should the gate be wide-open to include every possible community actor in neighbourhood space and in institutional processes? Or should the gate be more selective? If so, who are the appropriate gatekeepers? Whose judgment is right or best? Are there legitimate activities or lifestyles that should be considered? In socially sustainable urban communities, what does inclusion really mean? At what scale should decisions be made?

5.3. Environmentally just community development versus socially just community governance

Environmentally just community development and socially just community governance both address justice, albeit of a slightly different kind. Environmentally just community development includes a concern for future generations, thereby underlining that how one decides to use resources at present has a social value for the generations to follow us. Socially just community governance on the other hand operates in the present, underlining the value of social inclusionary governance processes to secure a common goal across these two understandings of justice: namely the equitable opportunity to access goods, resources, and services, and avoid harms and burdens.

Articles in the data set conclude that in a Nordic and North European context, compact city development is compatible with liveability and quality of life (Mouratidis Citation2018a, Citation2018b, Citation2019; Ala-Mantila et al. Citation2018; Kyttä et al. Citation2016). A challenge with the compact city model not addressed by these contributions, however, is that compact development may be a good model for ensuring liveability in the form of access to services, amenities and infrastructures for people already living in the neighbourhood. While the distribution of these goods may vary systematically between various groups in the neighbourhood and be inaccessible to people outside the neighbourhood. Medved (Citation2018) highlights the room for social justice in development according to new urbanism. He argues that a danger of development according to principles of new urbanism is that one creates what Fainstein (Citation2010) calls “citadels of exclusivity”. He studies two front-running neighbourhoods in Sweden and Germany marked by good access to many different benefits; green areas, social meeting places, renewable energy solutions, innovative and human-friendly architecture, which makes them attractive and expensive. According to Medved (Citation2018, 429), gentrification follows in the wake of environmentally sustainable densification, and begs the question:

… how to preserve the heterogenic structure of a sustainable urban area in order not to become an exclusive neighbourhood

According to research, policies capable of securing heterogeneity depend on the development of socio-cultural competency among community leaders and residents of the community in general, in addition to firm institutional anchoring of social justice and inclusiveness in governance policies and practices (Kohon Citation2018; Trudeau Citation2018; Medved Citation2018). Medved (Citation2018) and Trudeau (Citation2018) argue that the initial implementation approach of a project is a crucial phase, yet that such initial ideals need continuous confirmation to gain prominence.

6. Summary of results and identification of promising research agendas

Overall, the literature study illustrates how research on social sustainability in a community setting has gone from the exploration of foundational concepts to studying conditions and challenges for implementation and achieving social sustainability on the ground. The study of such operational processes has contributed insights into key concerns that needs to be addressed in community development and governance. However, knowledge on the institutionalisation of social sustainability in such processes and community organisations in general is still lacking. Thus, whereas this field of research seems conceptually less chaotic and nebulous than often claimed to be, creating socially sustainable communities in practice still is a near-utopian ideal.

Two dimensions summing up key aspects of community social sustainability stand out in the material: Socially just access to goods and opportunities in the local community and the sustainability of the local community expressed through a high degree of social capital, coherence, commitment, stability, belonging and security. These dimensions represent important ground structures of a community’s social sustainability. However, under the surface of these dimensions lies contradictions and dilemmas that become visible in contributions that in various ways address the operationalisation of such social sustainability ideals into concrete community development and governance processes. This paper suggests a set of three mutually related elements of community social sustainability capturing the abovementioned ground structures at the same time as they further distinguish and lifts attention to key concerns, competing demands and dilemmas arising at the intersection between them:

Neighbourhood social sustainability highlighting dear traditions, values and practices that people want to maintain. A neighbourhoods’ social sustainability thus cannot be measured by objective social and collective aspects of the community alone but needs to relate to the subjective meaning and value that these practices have for its inhabitants.

Socially just community governance highlighting social inclusion as a crucial aspect of justice. The idea is to avoid, reduce or combat socio-spatial marginalisation, segregation and spatial injustice through more inclusive governance processes capable of rebalancing power relationships and uneven spatial governance.

Environmentally just community development highlighting the linkage between social justice and the physical/material context of the community. The extent to which access to resources and goods are equitably distributed within and between communities today, and between present and future generations.

The discussion of these elements and the relations and tensions between them address some recurring themes and arguments pointing to knowledge gaps and future research needs. First, the analysis of the material illuminates how public actors have a double mission; acting as guardians of public interest and progressive forces challenging status quo. They shall maintain preferred ways of living, ensure that every, also minorities’ silent, voices are heard and have an influence on the result. At the same time, they shall promote intergenerational and broader societal interests, as resource efficiency and climate change transformation. These complex and competing expectations represent a persistent challenge, as these ideals are hard to reconcile. An interesting path for future research is thus to identify governance mechanisms capable of integrating social justice as a concern for urban governance, both at the initial stages of a project and over time. Another interesting avenue is to look more closely at sustainable transformation of communities, especially the dynamic between principles of new urbanism and existing values and practices that the neighbourhood’s residents want to maintain. Both these research agendas call for institutions and governance processes with greater sensitivity to the variety of needs and values represented in the community.

This leads to a second result of the literature study, namely that social justice holds a central position as both an ideal and an operational measure for community development. One strain of research takes the agenda forward by critically investigating competing concerns baked into the concept, thereby drawing a more diverse picture of the social landscape of communities. These contributions illuminate that communities are not monolithic entities; they are arenas for interest expression, conflicts, and conflict abatement. However, there is a knowledge gap concerning how to address and balance this diversity in governance processes. Consequently, a promising path for future research is to explore and develop governance mechanisms capable of integrating social justice as a guiding element for decision-making.

The third general argument arising from the literature study relates to social justice as a bridge over to wider sustainability issues, mirrored by the suggested division of social justice into two related, yet distinct concerns. In sum, the data set illuminates how social justice, like social sustainability as such, is a highly complex concept. Some contributions distinguish between environmental justice and social justice, while others address them in concert. Regardless of how different studies choose to categorise these concerns, a notable general impression from the analysis is how intergenerational justice gets far less attention than intragenerational justice. Most contributions address present social justice issues, like social inclusion or social access to amenities and facilities. With the continually closer integration of social, environmental, and economic sustainability in the wake of climate change, a third and final promising path for future research is to develop intergenerational justice as an aspect of community social sustainability.

In sum, the literature study illustrates how research on social sustainability at the community level has grown and matured over the last couple of years. This progress is most evident in a definitory consent across the research community, and a strengthened focus on challenging aspects of key ideals of sustainability. A prevailing immaturity in the field is the lack of political scientific contributions, which results in a knowledge gap concerning social sustainability governance. We need more knowledge of conditions and practical solutions for integrating social sustainability concerns in planning and urban development processes at the community level. Scholars and city practitioners increased interest in social sustainability heighten the prospects for progress in the years to come.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The literature study is the first step of the project “Social sustainability as a new driving force in local community development (SOSLOKAL)” where the main goal is to develop social sustainability as a core value and reference point for community development. The project is funded by the Norwegian Research Council.

2 This is not to say that forestry, fishing and agriculture are irrelevant in a Nordic context, but the social sustainability of them as economic practices by and of themselves are not directly relevant for the physical and social development of local communities.

References

- Ala-Mantila, S., J. Heinonen, S. Junnila, and P. Saarsalmi. 2018. “Spatial Nature of Urban Well-Being.” Regional Studies 52 (7): 959–973. doi:10.1080/00343404.2017.1360485.

- Andersen, B., and J. Skrede. 2017. “Planning for a Sustainable Oslo: The Challenge of Turning Urban Theory Into Practice.” Local Environment 22 (5): 581–594. doi:10.1080/13549839.2016.1236783.

- Arundel, R., and R. Roald. 2017. “The Role of Urban form in Sustainability of Community: The Case of Amsterdam.” EPB: Urban Analytics and City Science 44 (1): 33–53. doi:10.1177/0265813515608640.

- Bulkeley, H. 2021. “Climate Changed Urban Futures: Environmental Politics in the Anthropocene City.” Environmental Politics 30 (1–2): 266–284. doi:10.1080/09644016.2021.1880713

- Dacombe, R. 2018. “Systematic Reviews in Political Science: What Can the Approach Contribute to Political Research?” Political Studies Review 16 (2): 148–157. doi:10.1177/1478929916680641.

- Dassen, T., E. Kunseler, and L. M. van Kessenich. 2013. “The Sustainable City: An Analytical–Deliberative Approach to Assess Policy in the Context of Sustainable Urban Development.” Sustainable Development 21 (3): 193–205. doi:10.1002/sd.1550.

- Dempsey, N., G. Bramley, S. Power, and C. Brown. 2011. “The Social Dimension of Sustainable Development: Defining Urban Social Sustainability.” Sustainable Development 19 (5): 289–300. doi:10.1002/sd.417.

- Dempsey, N., C. Brown, and G. Bramley. 2012. “The key to Sustainable Urban Development in UK Cities? The Influence of Density on Social Sustainability.” Progress in Planning 77 (3): 89–141. doi:10.1016/j.progress.2012.01.001.

- Eizenberg, E., and Y. Jabareen. 2017. “Social Sustainability: A New Conceptual Framework.” Sustainability 9 (1): 68. doi:10.3390/su9010068.

- Esping-Andersen, G. 1990. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- European Commission. 2019. The European Green Deal. Brussels: European Commission.

- Fainstein, S. S. 2010. The Just City. Ithaca. NY: Cornell University Press.

- Franklin, A., and R. Dunkley. 2017. “Becoming a (Green) Identity Entrepreneur: Learning to Negotiate Situated Identities to Nurture Community Environmental Practice.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 49 (7): 1500–1516. doi:10.1177/0308518X17699610.

- Hofstad, H. 2012. “Compact City Development: High Ideals and Emerging Practices.” European Journal of Spatial Development 1 (1): 1–23.

- Hom, L. 2002. “The Making of Local Agenda 21: An Interview with Jeb Brugmann.” Local Environment 7 (3): 251–256. doi:10.1080/1354983022000001624.

- Johansson, M. 2015. “Conflicts and Meaning-Making in Sustainable Urban Development.” In Social Transformations in Scandinavian Cities: Nordic Perspectives on Urban Marginalization and Social Sustainability, edited by E. Righard, M. Johansson and T. Salonen, 233–249. Lund: Nordic Academic Press.

- Koch, F., and K. Krelleberg. 2018. “How to Contextualize SDG 11? Looking at Indicators for Sustainable Urban Development in Germany.” ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 7 (12): 464–480. doi:10.3390/ijgi7120464.

- Kohon, J. 2018. “Social Inclusion in the Sustainable Neighborhood? Idealism of Urban Social Sustainability Theory Complicated by Realities of Community Planning Practice.” City, Culture and Society 15: 14–22. doi:10.1016/j.ccs.2018.08.005. 54.

- Kyttä, M., A. Broberg, M. Haybatollahi, and K. Schmidt-Thomé. 2016. “Urban Happiness: Context-Sensitive Study of the Social Sustainability of Urban Settings.” Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 43 (1): 34–57. doi:10.1177/0265813515600121.

- Larimian, T., and A. Sadeghi. 2021. “Measuring Urban Social Sustainability: Scale Development and Validation.” EPB: Urban Analytics and City Science 48 (4): 621–637. doi:10.1177/2399808319882950.

- Medved, P. 2017. “Leading Sustainable Neighbourhoods in Europe: Exploring the Key Principles and Processes.” Urbani Izziv 28 (1): 107–121. doi:10.5379/urbani-izziv-en-2017-28-01-003.

- Medved, P. 2018. “Exploring the ‘Just City Principles’ Within Two European Sustainable Neighbourhoods.” Journal of Urban Design 23 (3): 414–431. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13574809.2017.1369870.

- Medved, P., J. I. Kim, and M. Ursic. 2020. “The Urban Social Sustainability Paradigm in Northeast Asia and Europe.” International Review for Spatial Planning and Sustainable Development 8 (4): 16–37. doi:10.14246/irspsd.8.4_16.

- Mouratidis, K. 2018a. “Built Environment and Social Well-Being: How Does Urban Form Affect Social Life and Personal Relationships?” Cities 74: 7–20. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2017.10.020.

- Mouratidis, K. 2018b. “Rethinking how Built Environments Influence Subjective Well-Being: A new Conceptual Framework.” Journal of Urbanism 11 (1): 24–40. doi:10.1080/17549175.2017.1310749.

- Mouratidis, K. 2019. “Compact City, Urban Sprawl, and Subjective Well-Being.” Cities 92: 261–272. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2019.04.013.

- Nadin, V., and D. Stead. 2013. “Opening up the Compendium: An Evaluation of International Comparative Planning Research Methodologies.” European Planning Studies 21 (10): 1542–1561. doi:10.1080/09654313.2012.722958.

- Opp, S. M. 2017. “The Forgotten Pillar: A Definition for the Measurement of Social Sustainability in American Cities.” Local Environment 22 (3): 286–305. doi:10.1080/13549839.2016.1195800.

- Petticrew, M., and H. Roberts. 2006. Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Shirazi, R., and R. Keivani. 2019. “The Triad of Social Sustainability: Defining and Measuring Social Sustainability of Urban Neighbourhoods.” Urban Research & Practice 12 (4): 448–471. doi:10.1080/17535069.2018.1469039.

- Shirazi, R., R. Keivani, S. Brownhill, and G. B. Watson. 2020. “Promoting Social Sustainability of Urban Neighbourhoods.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 1–25. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.12946.

- Trudeau, D. 2018. “Integrating Social Equity in Sustainable Development Practice: Institutional Commitments and Patient Capital.” Sustainable Cities and Society 41: 601–610. doi:10.1016/j.scs.2018.05.007.

- United Nations. 2015. Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. New York: United Nations.

- Vaidya, H., and T. Chatterji. 2020. “SDG 11 Sustainable Cities and Communities.” In Chapter 12 in Actioning the Global Goals for Local Impact, edited by I. B. Franco, T. Chatterji, E. Derbyshire, and J. Tracey, 173–185. Singapore: Springer Nature.

- Vallance, S., H. C. Perkins, and J. E. Dixon. 2011. “What is Social Sustainability? A Clarification of Concepts.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 42 (3): 342–348. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2011.01.002.

- Weingartner, C., and Å Moberg. 2011. “Exploring Social Sustainability: Learning from Perspectives on Urban Development and Companies and Products.” Sustainable Development 22: 122–133. doi:10.1002/sd.536.

- World Commission on Environment and Development. 1987. Our Common Future. Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development. New York: United Nations.