ABSTRACT

Calls for investment in green infrastructures, which can provide a range of ecosystem services in support of sustainability and resilience, are increasing amidst the climate crisis. The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed for many the important benefits of greenspace to cultural ecosystem services, particularly to individuals’ own assessments of their mental and emotional health, or subjective well-being (SWB). This pandemic has also revealed the unevenness of these benefits. In order to better understand the contributions of greenspace to SWB, as well as the distribution of the benefits, during times of shared social-ecological disruption, we investigate perceptions of greenspace and their effect on SWB during the COVID-19 pandemic. We use a mixed methods approach combining data from surveys and interviews conducted with US post-secondary students. Our results indicate that perceiving the outdoors as good for you is related to higher levels of SWB. We also find that both prior experience with nature and current social-environmental circumstances play an important role in shaping this perception. When considered alongside research regarding environmental justice and children’s access to nature, these findings suggest a need for both distributional and intergenerational justice in greenspace planning, design, and management, as well as explicit attention to the role of greenspace in coping with future social-ecological disturbance.

Introduction

The ongoing climate crisis and associated concerns for sustainability and resilience are driving investment in green infrastructure, including parks and gardens, street trees, and bioswales (to name a few). Green infrastructure can provide many ecosystem services, or benefits to human communities, including regulatory functions like mitigating stormwater flooding and moderating local temperatures, and cultural services such as improving physical, mental, and emotional health and well-being. Prior literature extensively documents the positive association between green spaces and human health and well-being (Bertram and Rehdanz Citation2015; Douglas, Lennon, and Scott Citation2017; Van den Bosch and Sang Citation2017). Given the expectation of a future marked by continued incidences of social-ecological disturbance, it is also important to understand if and how green infrastructure provides these cultural ecosystem services during times of shared crisis.

The early COVID-19 pandemic saw the closure of schools, parks, and non-essential businesses alongside stay-at-home and social distancing orders, which severely disrupted everyday life for billions of people around the world. This event has enabled assessments of the well-being benefits of green infrastructure during a time of social duress. Emerging findings suggest that parks, yards, gardens, and other greenspaces have indeed helped maintain or improve well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic (Berdejo-Espinola et al. Citation2021; Larson et al. Citation2022; Lehberger, Kleih, and Sparke Citation2021; Maurer and Cook et al. Citation2021; Poortinga et al. Citation2021; Ugolini et al. Citation2020). These studies, however, have also raised questions about for whom greenspace is beneficial. Research in the United States and the United Kingdom suggest those with limited access to greenspace struggled to find time and space outdoors during stay-at-home orders and public park closures (Burnett et al. Citation2021; Lopez et al. Citation2021; Slater, Christiana, and Gustat Citation2020). Those with limited access are by-and-large low-income and/or BIPOCFootnote1 individuals, though not all low-income and/or BIPOC individuals suffered from decreased access (Lee et al. Citation2021).

The barriers to access have been well-documented in the literature on urban space and environmental justice (Barbosa et al. Citation2007; Dai Citation2011; Nesbitt et al. Citation2019). Moreover, physical presence of greenspace does not ensure access. Inadequate transportation, connectivity infrastructure, and provisions for disability continue to present barriers to access, as do socio-cultural phenomena such as continued harassment and violence against women, LGBTQFootnote2 and BIPOC individuals in public green spaces (Grilli, Mohan, and Curtis Citation2020; Groshong et al. Citation2020; Roberts et al. Citation2019; Sonti et al. Citation2020; Wang, Brown, and Liu Citation2015). In addition to issues of distributional, representational, and procedural justice, questions of intergenerational justice should be considered. Research indicates children’s time in nature is decreasing over recent generations (Arvidsen et al. Citation2022; Kellert et al. Citation2017; Larson, Green, and Cordell Citation2011; Larson et al. Citation2019: Skår and Krogh Citation2009), though some recent studies suggest this is not a universal trend (Novotný et al. Citation2021). Meanwhile greenspaces are under continuing pressure from urban growth, economic development, biodiversity loss, and climate change (IPBES Citation2019; IPCC Citation2021; McPhearson et al. Citation2021). As such, the availability and accessibility of greenspace for children now, and for future generations, is far from guaranteed.

In addition to availability and accessibility, the relationship between green space and cultural ecosystem services are influenced by many other factors including demographics, landscape composition, connectedness to nature, and individual perceptions of aesthetics, biodiversity, and restorativeness, or the extent to which a space is perceived by an individual to be beneficial (Deng et al. Citation2020; Jarvis et al. Citation2020; Lai et al. Citation2020; Wang et al. Citation2019). In other words, receiving benefits from green infrastructure relies upon each individuals’ particular interactions with and within their social and environmental contexts, including access, perceived accessibility, and individual perceptions and relationships to the landscape.

Nor are social-environmental contexts static. Perceptions and relations to the environment are shaped over time and across generations through experience and interaction with and within particular landscapes (Ingold Citation2021; Raymond et al. Citation2021; Verbrugge et al. Citation2019; Williams Citation2014). As such, the narrative dimension to environmental perceptions and relations can, in turn, be anticipated to affect the benefits received from greenspace. Most studies regarding individuals’ perceptions of green space and associated benefits, however, rely on pre-established scales, rather than personal narratives, to assess individual responses (Irvine et al. Citation2013; Nordh, Evensen, and Skår Citation2017; Teti, Schatz, and Liebenberg Citation2020). Such assessments leave open questions about how individuals understand their perceptions to take shape, and shift in response to changing social-environmental contexts. Exploring these questions can help further our understanding of the provisioning of cultural ecosystem services – specifically, benefits related to personal well-being – during times of shared social-ecological disturbance. Thus, in this paper we use individuals’ narratives of spending time outdoors and coping with the early (March–June 2020) COVID-19 pandemic to explore how prior experience of greenspace and current social-environmental circumstances shape the experience of one particular cultural ecosystem service – subjective well-being.

Literature review

Theories for green spaces’ contribution to subjective well-being (SWB) proceed from the idea that people have an innate affiliation with nature, and thus contact with natural environments can aid in stress recovery and psychological restoration (Kaplan Citation1995; Ulrich et al. Citation1991). Environmental preferences, however, vary with respect to the individual and landscape, and thus have bearing on the contributions of nature to SWB (Hartig et al. Citation2011; Herzog, Maguire, and Nebel Citation2003). In order to assess variation in these preferences, several standardised scales have been developed. These include the Perceived Restorativeness Scale (PRS) (Hartig et al. Citation1997), which is widely used to measure how individuals view time in different environments in terms of enhancing well-being (Hipp et al. Citation2016; Peschardt and Stigsdotter Citation2013), as well as other PR scales to test which landscape factors affect restorative potential (Van den Berg, Jorgensen, and Wilson Citation2014; Wang et al. Citation2019).

Various nature-connectedness scales are also widely used to assess feelings or perceptions of connectedness to nature (CTN) in relation to variation based on individual and landscape factors (Mayer and Frantz Citation2004; Nisbet, Zelenski, and Murphy Citation2009), and in turn how differences in CTN influence such factors as SWB (McMahan and Estes Citation2015; Russell et al. Citation2013) and pro-environmental behaviour (Whitburn, Linklater, and Abrahamse Citation2020). CTN studies have also explored the influence of childhood experiences with nature on nature connectedness across the life-course. This research suggests that prior environmental experiences have a measurable effect on CTN and pro-environmental behaviour (Hughes et al. Citation2019).

The Perceived Environmental Aesthetic Qualities scale (PEAQS) has also been developed to assess perceptions of environmental and aesthetic quality in a standardised fashion across landscapes, and to relate individuals’ scores to measures such as SWB and place attachment (Subiza-Pérez et al. Citation2019). While standardised scales for measuring environmental perception and place attachment are also widely used (see for example Boley et al. Citation2021; Williams and Roggenbuck Citation1989), research on natural place and place-making has long acknowledged that a sense of place emerges over time through individuals’ relationships to a site’s environment and history, as well as their involvement in various social, cultural, and economic relationships tied to the site (Raymond et al. Citation2021; Williams Citation2014).

Thus, within studies of nature connectedness and sense of place, there is a recognition of the importance of experience over time, as well as emergent, holistic, multidimensional relationships to the natural environment. Nevertheless, studies of SWB and greenspace rarely incorporate such perspectives. There is a need for more qualitative research to address questions regarding how individuals come to perceive nature as good for them and how they understand such perceptions to respond to changes to social-environmental context (Nordh, Evensen, and Skår Citation2017; Teti, Schatz, and Liebenberg Citation2020). Addressing these questions is of particular importance to supporting well-being through greenspace use during extreme events with wide-scale social and environmental disruptions, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, where access to preferred greenspaces and outdoor routines may be disrupted, but the need for restoration and improvement to well-being is heightened.

Indeed, previous research suggests greenspace helps moderate the impact of stressful life events. For example, Marselle, Warber, and Irvine (Citation2019) found that while stressful life events were associated with an increase in perceived stress, depression, and a decrease in mental well-being, time in greenspace was associated with a decrease in perceived stress and depression and an increase in positive affect and mental well-being. Furthermore, Van den Berg et al. (Citation2010) found that among patients who had suffered a variety of stressful life events, those who had access to large amounts of greenspace within 3 km of one’s residence reported better SWB compared to patients with low amounts of greenspace in this radius. These results are congruent with Ottosson and Grahn’s (Citation2008) finding that experiencing nature was key in rehabilitating individuals experiencing bereavement or other severe loss. Literature further asserts that greenspace use could increase psychological resilience, and facilitate adapting to adversity, trauma, tragedy, threats, or significant sources of stress (Buikstra et al. Citation2010; Tidball Citation2012). While these studies document the effects of greenspace use on SWB during times of individual crises, the COVID-19 pandemic is a stressful life event simultaneously experienced by the global community, and, in its initial response stages, severely disrupted daily routines and access to greenspace.

Despite the disruptions posed by stay-at-home orders, social-distancing mandates, and generally heightened risk perception, research during the COVID-19 pandemic suggests greenspace remains important to maintaining well-being. Emerging studies identify public and private greenspaces as a key health resource amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, a time characterised by marked health risks and behavioural changes (Larson et al. Citation2022; Lehberger, Kleih, and Sparke Citation2021; Poortinga et al. Citation2021; Ugolini et al. Citation2020). Specifically, unprecedented restrictions to people’s movement under quarantine policies emphasised the importance of having nearby greenspace to maintain well-being (Lopez et al. Citation2021). For instance, Soga et al. (Citation2021) reported that greenspace use and green window views from within the home were correlated with increased self-esteem, life satisfaction, and subjective happiness. During the COVID-19 pandemic, individuals have also identified spending time in green spaces specifically as a stress reduction tactic (Berdejo-Espinola et al. Citation2021; Ugolini et al. Citation2020). As the COVID-19 pandemic has significantly impacted public physical and mental health (Salari et al. Citation2020), emerging studies indicate that consistent exposure to nature can improve a variety of markers of well-being (Berdejo-Espinola et al. Citation2021; Maurer and Cook et al. Citation2021; Soga et al. Citation2021).

Research objectives

The persistence of greenspace as a positive contributor to mental health and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic suggests that greenspace access and use are indeed important to weathering social and ecological crises. As such, the pandemic provides an opportunity for exploring how life experiences and social-environmental circumstances facilitate people’s going outdoors and perceiving nature to be good for them. However, neither the experience of the pandemic nor access to greenspace throughout the pandemic have been equitable (Burnett et al. Citation2021; Lopez et al. Citation2021; Slater, Christiana, and Gustat Citation2020). Thus, it is necessary to also ask how life experience and social-environmental circumstances vary in relation to key socio-demographic variables and contribute to uneven experiences of the COVID-19 pandemic.

To address this question, we draw on a mixed methods approach. Mixed-methods studies can both quantitatively establish extant relationships between greenspace and SWB and qualitatively capture individuals’ narrative accounts of relevant life experience and social-environmental circumstances. Thus, in order to understand who is benefiting from greenspace during times of crisis, we use both survey and interview methods coupled with statistical testing and qualitative coding analyses to ask:

In what ways do participants perceive and narrate the desirability and benefits of greenspace?

How did individuals’ self-reported perceptions of greenspace desirability and potential benefit affect SWB during the COVID-19 pandemic?

We conclude by exploring what the results of this inquiry mean for our understanding of who benefits from greenspace in times of duress and how greenspace accessibility can be more just and equitable.

Materials and methods

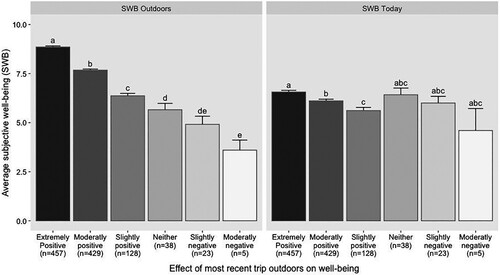

Data were collected using an online survey administered April–May 2020 and follow-up semi-structured interviews via video call in June 2021, which generated two data sets, both analysed in this paper. Surveys were distributed via email to undergraduate and graduate students at 71 higher education institutions across the US. Students were contacted via convenience snowball sampling utilising personal contacts and networks of colleagues. The survey consisted of forty questions regarding demographics, location, and living situation, self-reported SWB, greenspace use and access, risk perception regarding the pandemic and outdoor activity (Appendix S1). Subjective well-being was assessed on a scale of 1 (lowest)–10 (highest) during their last trip outdoors (hereafter “SWB outdoors’). Participants were also asked to rate the effect of their most recent trip outdoors on their well-being across a seven-point scale of Extremely Negatively, Negatively, Somewhat Negatively, No Effect, Somewhat Positively, Positively, Extremely Positively. Subjective well-being scores were compared among groups based on the self-reported effect of the most recent trip outdoors using an Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) and post-hoc multiple comparisons of means (TukeyHSD).

The survey also included an option to indicate if the participant was willing to volunteer for a follow-up interview. Of the 1130 survey respondents, 469 answered “yes” to volunteer for a follow-up interview. To select participants to interview from this subset, volunteers were sorted into six bins based on population density of reported ZIP code following the US census urban–rural classification (US Census 1994) and self-reported risk associated with going outdoors: Urban (>1159 persons km2) and High Risk Perception (rated going outdoors as Risky or Very Risky), Urban and Low Risk Perception (rated going outdoors as Somewhat or Not at all Risky), Suburban (386–1159 persons km2) and High Risk Perception, Suburban and Low Risk Perception, Rural (<386 persons km2) and High Risk Perception, and Rural and Low Risk Perception. Recruitment from within these six bins was designed to achieve a sample that better matched the demographics of the US undergraduate population. Three rounds of this sampling process led to contacting 356 individuals, of which we interviewed 72 individuals. Interview questions were semi-structured, open-ended and covered topics of living situation, subjective well-being, access and barriers to greenspace, risk perception related to the pandemic, and connection to nature (Appendix S2). Interviews were scheduled using the online platform Calendly and conducted over Zoom one-on-one between the interviewee and one member of the research team. All interviews ranged between 30 and 60 min in duration, and were video-recorded, though only audio tracks were saved for transcription and analysis purposes.

Survey respondent demographics

Participants for the broader project were selected from the population of university students attending US post-secondary educational institutions, spread across 71 higher education institutions, 45 states including Alaska, and 788 zip codes. 25.5% were classified as living in rural, 19.6% in suburban, and 51.3% in urban areas based on the population density of their ZIP code and 3.6% (41 individuals) did not report their ZIP code. Of this sample, 57% reported as white; 9.5% more than one race; 6.7% East/SouthEast Asian; 3.7% Latinx, 3.5% South Asian, 2.2% Black/African-American, and less than 1% each of Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, Middle Eastern/North African, and Black African (16.5% did not respond). 67.1% of the broader survey respondents identified as cisgendered women, 14.6% as cisgendered men, 1.4% as non-binary, less than 1% as transgendered, and 16.4% preferred not to disclose their gender. 13.7% were in their first year of school, 14.8% second, 19.5% third, 22.9% fourth, and 13.8% post-graduate (15.3% did not respond to this question). 42% (n = 470) reported receiving financial aid. We find this sample loosely representative of the US undergraduate population, except for an over-representation of women and under-representation of Black, Latinx, and Native/Indigenous students.

Interview participant demographics

While the interview population (n = 72) varied slightly compared to that of the broader survey, interviewee demographics remained skewed in similar ways. 59.7% of interviewees identified as white, while 16.7% identified as more than one race, 11.1% as East/SouthEast Asian, 4.2% as South Asian, 4.2% identified as Latinx, and 2.8% identified as Middle Eastern/North African (the remaining 1.4% did not provide information). 73.6% of interviewees were cisgendered women, 22.2% were cisgendered men, and 4.2% were non-binary. The interviewee sample included a higher proportion of graduate or professional students when compared to the survey population (8.3% first year, 16.7% second, 13.9% third, 25% fourth, 36.1% graduate/professional). Interviewees were less likely to receive financial aid than the survey population (61.1% no financial aid, 28.9% receiving financial aid, 10% did not disclose information).

Interview content and analysis

Using the online service Rev, all interviews were transcribed verbatim. A subset of interviews were initially coded by all members of the research team to assess intercoder reliability. Following, the research team completed two rounds of qualitative coding using the coding software Dedoose. For the first round, codes derived from the research questions and aligned with the survey questions were used. This deductive coding approach was used as part of a mixed-method analysis wherein interview data were used to support and add nuance to the survey data (Kaźmierczak Citation2013). During this process, the research team also identified emerging themes and a second round of coding was used to apply these inductively derived codes. This round of coding was guided by grounded theory approaches (Charmaz Citation2005), chosen to identify patterns not originally anticipated in research questions and design and to enable participant’s own voices to shape the analysis of their narratives (Pink Citation2012; Rosaldo Citation1993). Both rounds were iterative processes involving reading and re-reading the transcripts, forming initial and subsequent indices of themes. Intercoder reliability was maintained through a system of internal memoing and regular meetings to review coded interviews.

Results

Finding 1: perceived effect of going outside on subjective well-being

Survey respondents were asked to rate their level of subjective well-being (SWB) during their most recent trip outdoors. Overall, respondents reported highest levels of SWB outdoors when perceived risk was lowest, with little difference by geographic location or socio-demographic factors. While non-COVID related barriers to access, such as time, connectivity, and racist harassment persisted in our sample, the most frequently cited barriers to spending time outside were those related to the COVID-19 pandemic, such as overcrowding, lack of compliance with regulations, and concern for disease transmission. These overview results in which we more extensively examine how risk perception and accessibility impact SWB are reported elsewhere (Maurer and Cook et al. Citation2021). Here, we build on the previously reported analyses to examine survey responses to questions about pre-existing perceptions of the benefits from time spent outdoors and how it impacts SWB.

Perception of the benefits of time spent outdoors, and in green space, was associated with the level of outdoor well-being (SWB outdoors). Of the 1081 participants who responded to the question, the majority of respondents (93.8%, n = 1014) expressed that going outdoors had a positive (defined as “extremely”, “moderately”, or “slightly” positive) effect on their well-being. In addition, we found significant differences in SWB outdoor ratings based on how positively respondents perceived going outside (). For example, SWB outdoors was significantly higher for participants with more positive perceptions of going outdoors and was highest (8.9 ± 0.05) for those who reported “Extremely Positive” effects of going outdoors on well-being (; ANOVA, df = 5, p < .001). These associations suggest that perception and assessment of SWB outdoors influence one another, though the direction of that influence is uncertain. Our interview results, however, enable us to interrogate these findings further and explore factors that influence the relationship between perceiving and experience going outdoors to be good for one’s well-being.

Figure 1. Average (±1 SE) self-reported subjective well-being (SWB) on a scale of 1 (low) to 10 (high). Participants’ SWB during their last trip outdoors (“SWB Outdoors”). Each SWB score is averaged based on respondents’ perceived effect of their most recent trip outdoors on their well-being. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences within each SWB score. Only one participant indicated an “Extremely Negative” effect of their most recent trip outdoors on the seven-point Likert scale, and thus this data was removed from analyses.

Finding 2: narratives of perceived positive contribution of greenspace to well-being

Interviews revealed and gave nuance to how spending time in greenspace helped people cope with the stress and disruption to life brought on by the pandemic. Many interviewees expressed the belief that nature would be beneficial for their subjective well-being – a finding that aligns with the analysis of survey data reported above. Further analysis of our qualitative interviews sheds more light on the relationship between perceived positive contributions of going outside and improved SWB derived from going outdoors. We identified the two most common themes among those who reported benefiting from spending time in greenspace during the pandemic. These themes are: (1) previous personal experiences, or (2) socio-environmental circumstances. Below, we outline further sub-themes under each, with interview excerpts as examples (see also ).

Table 1. Themes and sub-themes regarding the association between perceived positive contribution of greenspace and SWB.

A-1. Previous personal experiences: familiarity with the outdoors

Having time outdoors as a regular and familiar part of life while growing up and/or presently was a prominent commonality across interviewees who found well-being benefits from spending time outdoors during the pandemic. One interviewee who was finding solace in time outdoors said:

I grew up playing in [nature] with my friends, I have so many memories like, you know, running around through the sprinkler and like, making (laughs) mud ceramics and letting it dry in the sun. […] Oregon and Washington are such beautiful places to experience the outdoors and […] I think what came with enjoying it was also learning about it, which made me enjoy it even more … because like, we spent a lot of time outside growing up. (A01)

The “outdoors’ did not necessarily have to be greenspace for some individuals, as noted by one interviewee:

[being outdoors] makes me really happy and I wish I did it more often […] but I feel like, intentionally going outside to spend time and find these green spaces is not something I do that typically, but I do really enjoy like being in a city and just like walking around downtown, or you know, going to around like the Vessel area and like walking along the High Line … I like to do that when I have free time and I think that's like one of my favourite things to do. (A31)

As demonstrated here, having had outdoor time as a routine part of one’s life seemed to instil a sense of familiarity, recognition, and appreciation for the benefits that can be derived from it. This interviewee later stated:

I’ll usually just like lie on the grass and um, be reading and sitting under a tree. […] And then all those things make me feel like, a lot more … refreshed and energised and also less anxious, just in the sense that it’s like, I don’t have to be worrying about […] stress that I place on myself to be more productive … (A31)

A-2. Previous personal experiences: nature as established coping mechanism

On a related note, those with experience specifically engaging with nature as a coping mechanism through mental health challenges found this benefit persisted during the pandemic. Though this sub-theme is less prominent, these narratives hold key insights regarding the perception of nature as good for one’s well-being during a time of crisis. For example, one interviewee who felt they were keeping up their well-being during the pandemic through time in outdoor green space stated:

[nature] probably saved my life. […] I had a lot of anxiety and depression when I was a teenager [and] had some real problems and […] I kind of [got] through [it] getting outside and getting into nature and learning more about it … . kind of developed it as almost like a coping mechanism to stress … really just recharges me. […] [I]t’s something I really prioritise in my life even before this. […] being in a larger space helps me kind of like … any stress or anxiety kind of disperses into the space. (A08)

Another interviewee described the way in which they have engaged with nature to feel better.

I think even just like having five minutes, like, sitting outside is beneficial. Like to just be in direct sunlight for like five minutes is always good, but to also just breathe fresh air and … having that access to the outdoor space is so important because like, even if it seems like you don’t need it […] until you actually step outside and you’re like, “Wow, this feels great” (laugh). (A59)

A commonality across those who were benefiting from time outdoors as a pre-existing coping mechanism was finding stillness and tranquillity in nature. For example, there seemed to be a recognition that mental well-being requires a quiet space of contemplation, which some participants, from previous experience, found in being outside. For the interviewee who resorted to frequenting a large open area that used to be a golf course along a meandering river with barn swallows and beavers, nature served as a way to keep everything in perspective.

It’s always a nice reminder that [whatever] I’ve got personally going on, the world kind of exists in a larger way, you know, you can just walk along and suddenly you see like the moon coming up or the beautiful clouds drifting by. There’s just something that kind of takes you out of yourself and be like, oh yeah, like there are still good things right now. (A08)

B-1. Social-environmental circumstances: yearning for a break from current situation and isolation

Like the previous respondent’s need for a reminder of good things, many who found themselves in situations from which they wanted a reprieve seemed to more frequently seek out, and find benefit in, time spent outdoors. One situation from which many felt the need for a break was the combination of working-from-home and increased screen-time due to stay-at-home orders. One interviewee stated:

it’s funny ‘cause … we’ve been talking about outdoor-time this entire time, but like, it’s kind of changed my attitude towards indoor time a lot. On the flip side, it’s like, I valued my indoor time before, and now it’s just, I hate it, like the entire time. […] I realise I have to be here. It might just be the fact that I have to do it so much, but, the intense hatred of just sitting and watching TV, was like not a thing I had before and now I do. […] I easily spent like, you know, days playing video games before. And now, the days that I spend playing video games, I absolutely hate them, [I] need to get outside. (A51)

For many, being outdoors was also the only way to break free of isolation and be social, leading them to associate the outdoor spaces as a “happier” place. As one interviewee put it:

[A]nytime that I’m outside, I’m usually either with a family member on a walk, or I have driven to go meet a friend at a park and socially distant hang out with them. So, I think it’s the combination of both like being outdoors and social interaction. That’s really nice. (A11)

The same was true for those who felt isolated due to adhering to stay-at-home orders, who found comfort simply in being “alone but together” outside with anonymous passers-by. One interviewee noted finding connectedness in greenspaces despite being alone.

I find it so nurturing and grounding and it has been fundamentally the biggest thing that has been helping me in terms of mental health. In terms of just COVID, I’ve been feeling so isolated from my networks of support and from people who are so dear to me. And I just have such a strong sense when I’m in these green spaces of connectedness and of feeling really held. (A65)

B-2. Social-environmental circumstances: proximity and access to green space

Another prominent social-environmental circumstance that was common among those who reported benefiting from time outdoors was living proximate to accessible greenspace. Having greenspace nearby made spending time outdoors an easy option. However, this was a privilege not everyone had, which many interviewees recognised.

I feel really lucky that I have access to a park and a green space so close to me, and I think that if I didn’t it’d be like a really different experience […] Because … going to trails is risky and stuff […] I wish that even more people had this much access to a park […] I think that’s vastly improved my well-being during this whole experience. (A68)

However, the mere existence of a greenspace was not sufficient; accessibility, safety, aesthetics and amount of space afforded played a role in its appeal. As one interviewee explains:

I didn’t feel super motivated to leave my house because my neighbourhood at home isn’t super safe at night to walk around, and during the day I feel fine walking around. But […] there are no trees, there’s not really a particular draw in terms of aesthetic or being in nature. [A]nd because of that, it felt like my whole entire neighbourhood was really very much in quarantine. (A27)

Interview findings portray common experiences and circumstances regarding individuals’ perceptions of greenspace as good for them. They suggest that both prior personal experience of nature and current social-environmental circumstances contribute to the perception that going outside and spending time in nature is good for one’s well-being. In turn, results from surveys confirm that for most respondents, going outside is good for SWB, and that perceiving it as such has a significant, positive effect on SWB when outdoors. Together, these results affirm that outdoor spaces, particularly vegetated ones, are beneficial for many reasons.

Discussion

Our research identifies two primary findings: first, there is a relationship between perceiving going outside as good for well-being and experiencing higher levels of subjective well-being (SWB) while outdoors (SWB outdoors) during the COVID-19 pandemic. Second, that individuals locate these perceptions in narratives about previous experiences with nature and in their current social-environmental circumstances. These findings support previous research on the relationship between greenspace and SWB while also providing novel understandings of why individuals perceive greenspace as beneficial within the context of a shared experience of social duress and disruption.

Previous research has identified several possible pathways for the positive effect on SWB individuals experience when spending time in greenspace. These include mechanisms related to perceptions of the environment, such as connectedness to nature (CTN) (McMahan and Estes Citation2015; Russell et al. Citation2013) and perceived restorativeness (PR) (Hartig et al. Citation2011; Hipp et al. Citation2016; Peschardt and Stigsdotter Citation2013). Our results support the importance of perception. One interpretation of our survey findings suggests that the more one perceives going outside as good for them – be it from a sense of perceived restorativeness or connection to nature – the more positive effects on their SWB they experience. Such a conclusion is supported by those interviewees who named prior experience with greenspace as an important factor influencing their reliance on outdoor spaces to support their well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. These findings also contribute to the growing body of pandemic-era literature on greenspace and well-being, supporting the overarching conclusion that time spent outdoors has helped maintain well-being and moderate stress during the COVID-19 pandemic (Berdejo-Espinola et al. Citation2021; Larson et al. Citation2022; Lehberger, Kleih, and Sparke Citation2021; Lopez et al. Citation2021; Maurer and Cook et al. Citation2021; Poortinga et al. Citation2021; Salari et al. Citation2020; Soga et al. Citation2021; Ugolini et al. Citation2020).

Perceptions of the environment, however, are neither static nor uni-dimensional. Many interviewees reported changing attitudes regarding time both indoors and outdoors. Outdoor time became more valuable and sought after, while indoor time became a source of strain, as exemplified by the participant (A51) who no longer enjoyed their time indoors playing video games. The experiences of these interviewees “pushed” outdoors supports the interpretation that positive experiences of well-being in greenspace shape the perception that going outside is good for you. This is also congruent with our understanding of how perceptions of the environment form and change over time, in response to learned behaviours and experiences. These perceptions also take shape in relationship to other people and places, as well as both day-to-day and exceptional activities (Gulsrud, Hertzog, and Shears Citation2018; Ingold Citation2021; Raymond et al. Citation2021; Verbrugge et al. Citation2019). While our results support existing research on greenspace and well-being, both during normal and pandemic conditions, findings from our interviews provide further explanation of these effects. Most assessments of the positive effect of greenspace and SWB focus on the use of standardised assessments. Through analysis of in-depth interviews, which give space for individual narrative and self-reflection, our study is also able to present findings about why the positive association between greenspace and SWB exists for participants during this time.

Firstly, we find that past experience with greenspace matters. Among interviewees who reported benefits from time spent in greenspace, one-third connected the positive effect to previous experience and familiarity with nature. Not only were they more likely to engage with greenspace as a coping mechanism during a time of collective duress, but they were more “primed” to actively seek and gain benefits from greenspace in the first place, leading to a positive feedback loop. This finding aligns with existing work on the relationships between CTN and SWB (Whitburn, Linklater, and Abrahamse Citation2020) and childhood experience of nature and CTN (Fretwell and Greig Citation2019; Hughes et al. Citation2019). Childhood access to nature, however, is unequal across the current population, and recently authors have expressed concern it is decreasing across recent generations (Arvidsen et al. Citation2022; Kellert et al. Citation2017; Larson, Green, and Cordell Citation2011; Larson et al. Citation2019: Skår and Krogh Citation2009). This suggests that the necessary pre-conditions for achieving the most benefit from greenspace during times of crisis are inequitably distributed both within and between generations, and supports calls for intergenerational, as well as procedural, distributional, and representational dimensions of justice in greenspace access (Gearin and Kahle Citation2006; Hiskes and Hiskes Citation2009; Rigolon and Flohr Citation2014). Moreover, our findings show a negative perception of going outdoors is associated with significantly lower SWB while outside. This further supports the importance of positive prior experiences outdoors for later use of greenspace to support and maintain SWB during times of widespread social-environmental disruption.

This is not to say that those without previous experience did not reap benefits. Particular attributes of social-environmental circumstances also appeared to be shared among those who gained SWB benefits from greenspace during the pandemic. Having easy and proximate access to nature was an important factor in participants’ narratives of going outdoors and gaining SWB benefits from greenspace. For example, living near greenspace was a common factor across those who found SWB benefits outdoors, irrespective of differences in previous experiences (or lack thereof). This finding is consistent with the literature on the importance of greenspace access and accessibility (Deng et al. Citation2020; Grilli, Mohan, and Curtis Citation2020; Roberts et al. Citation2019; Wang et al. Citation2019). Furthermore, there was a specificity to the pandemic experience of isolation as a motivating “push” factor that led people outdoors. Desire to escape the indoors interacted with the accessibility of greenspace to push people outside. Exactly why people wished to escape – be it endless screen time, fractious home environments, or the isolation of staying at home – varied from individual to individual and was specific to their experience of the COVID-19 pandemic. We observed, however, that the accessibility of greenspace was not evenly distributed. Some respondents identified accessibility challenges due to feelings of insecurity, lack of nearby nature, or poor connectivity infrastructure, while others contrasted their relative ease of accessibility with those in other locations. Factors such as distribution and safety have been found to influence accessibility in the broader environmental justice research on greenspace access, where they are frequently related to race and class based differences (Barbosa et al. Citation2007; Dai Citation2011; Nesbitt et al. Citation2019; Sykes Citation2022). The under-representation of these differences in our sample likely contributed to fewer instances of lack of access in our study. Nevertheless, our findings regarding accessibility support those of other studies regarding access and environmental justice. Alongside our results highlighting the importance of prior experience, this finding suggests that during crisis events, encouragement or support for greenspace use to cope with stress and maintaining well-being needs to be sensitive to the ways in which social-environmental and social-political contexts, as well as knowledge and experience, vary within a population and with respect to the disturbance at hand.

Limitations

These findings must be considered alongside study limitations. We identify two primary limitations to our research. First, we did not directly assess CTN or PR in this study. While our study was intended to focus on the narratives participants gave for why they perceived greenspace as good for them during the COVID-19 pandemic, inclusion of standardised assessments would have allowed our results to be more readily compared with those of previous studies. Our results, however, do support both PR and CTN as contributors to a positive relationship between greenspace and SWB. Second, we did not have a longitudinal component to our research. One key finding of our study was that prior greenspace experiences mattered and a priori data regarding participants’ previous use of greenspace would have further supported individuals’ narratives in this regard.

Conclusions and recommendations

In response to increasing threats from the climate crisis, there is growing investment in green infrastructure (Gulsrud, Hertzog, and Shears Citation2018; McPhearson et al. Citation2021). Based on our findings that prior experience with nature and social-environmental circumstances both contributed to the perception of greenspace as good for one’s well-being – a perception subsequently linked to higher levels of subjective well-being (SWB) during the COVID-19 pandemic – we conclude that planning for future social-ecological disturbance would do well to account for the role of greenspace, as it provides important cultural ecosystem services.

These services, however, are not evenly distributed. Given the benefits our participants derived from spending time outdoors, and the role of easy, proximate access to greenspace in their narratives, we conclude there is need to continue support for equitable distribution of greenspace and inclusive planning. Moreover, to ensure greenspaces and their cultural ecosystem services are utilised to their fullest potential, there must be considerations of access across multiple axes. In particular, our results suggest that we need to consider the temporal, as well as spatial, character of greenspace access. Prior experience with greenspace matters. Previous childhood experiences with nature regularly emerged in participants’ narratives of why they found greenspace beneficial during the COVID-19 pandemic. This finding, alongside research on the important role of PR, CTN, and childhood experiences of nature in positive associations between greenspace and SWB, suggests that those without previous experience or familiarity with nature may be less likely to reap benefits from interactions with greenspace, particularly during times of social duress and widespread crisis. Thus, we conclude that environmental planning needs to take up issues of intergenerational justice, ensuring opportunities for access to, relationships with, and sociality within greenspace, for both contemporary children and future generations.

In other words, planning and design must account for distributional and intergenerational justice in greenspace access, which in turn translates to opportunities to develop relationships with nature and modes of outdoor sociality that support the perception that greenspace is good for you. Thus, we recommend investments in publicly available greenspace and infrastructures for accessing nature, and that these investments prioritise those with poor access to greenspace and those who are – and will be – disproportionately negatively affected by social-ecological disturbance – namely, youth, BIPOC, and low-income individuals and neighbourhoods. Given the role greenspace played in well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as the specificity of social-environmental contexts of that experience, we also recommend that planning for response to social-ecological disturbance include the role of greenspace. The planning should be flexible and attentive to how a given disturbance may be experienced differently within a given population, which in turn calls for representational justice and inclusive processes that encompass diverse needs. The frequency of occasions in which we may find ourselves relying on greenspace to support and maintain well-being in the face of wide-scale crises is increasing due to climate change. As such, considerations of equitable and equal access to greenspace, across extant populations and between generations, are increasingly important.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (37.1 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge support from the US National Science Foundation RAPID award #2029301. EC would also like to acknowledge support from the Growing Convergence Research award #1934933. MM would also like to acknowledge support from the Planning with Youth project funded by FORMAS, the Swedish Research Council for Sustainable Development (the Sustainable Spatial Planning Program).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 BIPOC stands for Black, Indigenous, and People of Colour.

2 LGBTQ stands for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer.

References

- Arvidsen, Jan, T. Schmidt, Søren Præstholm, Søren Andkjær, Anton Stahl Olafsson, Jonas Vestergaard Nielsen, and Jasper Schipperijn. 2022. “Demographic, Social, and Environmental Factors Predicting Danish Children’s Greenspace Use.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 69: 127487. doi:10.1016/j.ufug.2022.127487.

- Barbosa, Olga, Jamie A. Tratalos, Paul R. Armsworth, Richard G. Davies, Richard A. Fuller, Pat Johnson, and Kevin J. Gaston. 2007. “Who Benefits from Access to Green Space? A Case Study from Sheffield, UK.” Landscape and Urban Planning 83 (2-3): 187–195. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2007.04.004.

- Berdejo-Espinola, Violeta, Andrés F. Suárez-Castro, Tatsuya Amano, Kelly S. Fielding, Rachel Rui Ying Oh, and Richard A. Fuller. 2021. “Urban Green Space use During a Time of Stress: A Case Study During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Brisbane, Australia.” People and Nature 3 (3): 597–609. doi:10.1002/pan3.10218.

- Bertram, Christine, and Katrin Rehdanz. 2015. “The Role of Urban Green Space for Human Well-Being.” Ecological Economics 120: 139–152. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2015.10.013.

- Boley, B. Bynum, Marianna Strzelecka, Emily Pauline Yeager, Manuel Alector Ribeiro, Kayode D. Aleshinloye, Kyle Maurice Woosnam, and Benjamin Prangle Mimbs. 2021. “Measuring Place Attachment with the Abbreviated Place Attachment Scale (APAS).” Journal of Environmental Psychology 74: 101577. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2021.101577.

- Buikstra, Elizabeth, Helen Ross, Christine A. King, Peter G. Baker, Desley Hegney, Kathryn McLachlan, and Cath Rogers-Clark. 2010. “The Components of Resilience-Perceptions of an Australian Rural Community.” Journal of Community Psychology 38 (8): 975–991. doi:10.1002/jcop.20409.

- Burnett, Hannah, Jonathan R. Olsen, Natalie Nicholls, and Richard Mitchell. 2021. “Change in Time Spent Visiting and Experiences of Green Space Following Restrictions on Movement During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Nationally Representative Cross-Sectional Study of UK Adults.” BMJ Open 11 (3): e044067. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-044067.

- Charmaz, Kathy. 2005. “Grounded Theory in the 21st Century: A Qualitative Method for Advancing Social Justice Research.” Handbook of Qualitative Research 3 (7): 507–535.

- Dai, Dajun. 2011. “Racial/Ethnic and Socioeconomic Disparities in Urban Green Space Accessibility: Where to Intervene?” Landscape and Urban Planning 102 (4): 234–244. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2011.05.002.

- Deng, Li, Xi Li, Hao Luo, Er-Kang Fu, Jun Ma, Ling-Xia Sun, Zhuo Huang, Shi-Zhen Cai, and Yin Jia. 2020. “Empirical Study of Landscape Types, Landscape Elements and Landscape Components of the Urban Park Promoting Physiological and Psychological Restoration.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 48: 126488. doi:10.1016/j.ufug.2019.126488.

- Douglas, Owen, Mick Lennon, and Mark Scott. 2017. “Green Space Benefits for Health and Well-Being: A Life-Course Approach for Urban Planning, Design and Management.” Cities 66: 53–62. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2017.03.011.

- Fretwell, Kay, and Alison Greig. 2019. “Towards a Better Understanding of the Relationship Between Individual’s Self-Reported Connection to Nature, Personal Well-Being and Environmental Awareness.” Sustainability 11 (5): 1386. doi:10.3390/su11051386.

- Gearin, Elizabeth, and Chris Kahle. 2006. “Teen and Adult Perceptions of Urban Green Space Los Angeles.” Children Youth and Environments 16 (1): 25–48. doi:10.7721/chilyoutenvi.16.1.0025.

- Grilli, Gianluca, Gretta Mohan, and John Curtis. 2020. “Public Park Attributes, Park Visits, and Associated Health Status.” Landscape and Urban Planning 199: 103814. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2020.103814.

- Groshong, Lisa, Sonja A. Wilhelm Stanis, Andrew T. Kaczynski, and J. Aaron Hipp. 2020. “Attitudes About Perceived Park Safety among Residents in low-Income and High Minority Kansas City, Missouri, Neighborhoods.” Environment and Behavior 52 (6): 639–665. doi:10.1177/0013916518814291.

- Gulsrud, Natalie Marie, Kelly Hertzog, and Ian Shears. 2018. “Innovative Urban Forestry Governance in Melbourne? Investigating “Green Placemaking” as a Nature-Based Solution.” Environmental Research 161: 158–167. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2017.11.005.

- Hartig, Terry, Agnes E. Berg, Caroline M. Hagerhall, Marek Tomalak, Nicole Bauer, Ralf Hansmann, Ann Ojala, et al. 2011. “Health Benefits of Nature Experience: Psychological, Social and Cultural Processes.” In Forests, Trees and Human Health, edited by Kjell Nilsson, Marcus Sangster, Christos Gallis, Terry Hartig, Sjerp de Vries, Klaus Seeland, and Jasper Schipperijn, 127–168. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Hartig, Terry, Kalevi Korpela, Gary W. Evans, and Tommy Gärling. 1997. “A Measure of Restorative Quality in Environments.” Scandinavian Housing and Planning Research 14 (4): 175–194. doi:10.1080/02815739708730435.

- Herzog, Thomas R., Peter Maguire, and Mary B. Nebel. 2003. “Assessing the Restorative Components of Environments.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 23 (2): 159–170. doi:10.1016/S0272-4944(02)00113-5.

- Hipp, J. Aaron, Gowri Betrabet Gulwadi, Susana Alves, and Sonia Sequeira. 2016. “The Relationship Between Perceived Greenness and Perceived Restorativeness of University Campuses and Student-Reported Quality of Life.” Environment and Behavior 48 (10): 1292–1308. doi:10.1177/0013916515598200.

- Hiskes, Richard D., and Richard P. Hiskes. 2009. The Human Right to a Green Future: Environmental Rights and Intergenerational Justice. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Hughes, Joelene, Mike Rogerson, Jo Barton, and Rachel Bragg. 2019. “Age and Connection to Nature: When is Engagement Critical?” Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 17 (5): 265–269. doi:10.1002/fee.2035.

- Ingold, Tim. 2021. The Perception of the Environment: Essays on Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill. New York, NY: Routledge.

- IPBES. 2019. “Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services.” In edited by E. S. Brondizio, J. Settele, S. Díaz, and H. T. Ngo, 1148. Bonn: IPBES Secretariat. doi:10.5281/zenodo.3831673

- IPCC. 2021. “Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis.” In Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, edited by V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S. L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M. I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J. B. R. Matthews, T. K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, and B. Zhou. Cambridge University Press. In Press.

- Irvine, Katherine N., Sara L. Warber, Patrick Devine-Wright, and Kevin J. Gaston. 2013. “Understanding Urban Green Space as a Health Resource: A Qualitative Comparison of Visit Motivation and Derived Effects among Park Users in Sheffield, UK.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 10 (1): 417–442. doi:10.3390/ijerph10010417.

- Jarvis, Ingrid, Sarah Gergel, Mieke Koehoorn, and Matilda van den Bosch. 2020. “Greenspace Access Does Not Correspond to Nature Exposure: Measures of Urban Natural Space with Implications for Health Research.” Landscape and Urban Planning 194: 103686. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2019.103686.

- Kaplan, Stephen. 1995. “The Restorative Benefits of Nature: Toward an Integrative Framework.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 15 (3): 169–182. doi:10.1016/0272-4944(95)90001-2.

- Kaźmierczak, Aleksandra. 2013. “The Contribution of Local Parks to Neighbourhood Social Ties.” Landscape and Urban Planning 109 (1): 31–44. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2012.05.007.

- Kellert, Stephen R., David J. Case, Daniel Escher, Daniel J. Witter, Jessica Mikels-Carrasco, and Phil T. Seng. 2017. “The Nature of Americans: Disconnection and Recommendations for Reconnection.” The Nature of Americans National Report, DJ Case and Associates, Mishawaka, Indiana, USA. Accessed July 11: 2018.

- Lai, Ka Yan, Chinmoy Sarkar, Ziwen Sun, and Iain Scott. 2020. “Are Greenspace Attributes Associated with Perceived Restorativeness? A Comparative Study of Urban Cemeteries and Parks in Edinburgh, Scotland.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 53: 126720. doi:10.1016/j.ufug.2020.126720.

- Larson, Lincoln R., Gary T. Green, and H. Ken Cordell. 2011. “Children’s Time Outdoors: Results and Implications of the National Kids Survey.” Journal of Park and Recreation Administration 29 (2): 1–20. https://search-ebscohostcom.ep.fjernadgang.kb.dk/login.aspx?direct=true&db=a9h&AN=66248864&site=ehost-live

- Larson, Lincoln R., Lauren E. Mullenbach, Matthew HEM Browning, Alessandro Rigolon, Jennifer Thomsen, Elizabeth Covelli Metcalf, Nathan P. Reigner, et al. 2022. “Greenspace and Park use Associated with Less Emotional Distress among College Students in the United States During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Environmental Research 204: 112367. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2021.112367.

- Larson, Lincoln R., Rachel Szczytko, Edmond P. Bowers, Lauren E. Stephens, Kathryn T. Stevenson, and Myron F. Floyd. 2019. “Outdoor Time, Screen Time, and Connection to Nature: Troubling Trends among Rural Youth?” Environment and Behavior 51 (8): 966–991. doi:10.1177/0013916518806686.

- Lee, Hannah, Imaan Bayoumi, Autumn Watson, Colleen M. Davison, Minnie Fu, Dionne Nolan, Dan Mitchell, Sheldon Traviss, Jennifer Kehoe, and Eva Purkey. 2021. “Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Children and Families from Marginalized Groups: A Qualitative Study in Kingston, Ontario.” COVID 1 (4). doi:10.3390/covid1040056.

- Lehberger, Mira, Anne-Katrin Kleih, and Kai Sparke. 2021. “Self-reported Well-Being and the Importance of Green Spaces – A Comparison of Garden Owners and non-Garden Owners in Times of COVID-19.” Landscape and Urban Planning 212: 104108. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2021.104108.

- Lopez, Bianca, Christopher Kennedy, Christopher Field, and Timon McPhearson. 2021. “Who Benefits from Urban Green Spaces During Times of Crisis? Perception and Use of Urban Green Spaces in New York City During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 65: 127354. doi:10.1016/j.ufug.2021.127354.

- Marselle, Melissa R., Sara L. Warber, and Katherine N. Irvine. 2019. “Growing Resilience Through Interaction with Nature: Can Group Walks in Nature Buffer the Effects of Stressful Life Events on Mental Health?” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16 (6): 986. doi:10.3390/ijerph16060986.

- Maurer, Megan, Elizabeth M. Cook, Liv Yoon, Olivia Visnic, Ben Orlove, Patricia Culligan, and Brian Mailloux. 2021. “Understanding Multiple Dimensions of Perceived Greenspace Accessibility and Their Effect on Subjective Well-Being During a Global Pandemic.” Frontiers in Sustainable Cities, 124. doi:10.3389/frsc.2021.709997.

- Mayer, F. Stephan, and Cynthia McPherson Frantz. 2004. “The Connectedness to Nature Scale: A Measure of Individuals’ Feeling in Community with Nature.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 24 (4): 503–515. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2004.10.001.

- McMahan, Ethan A., and David Estes. 2015. “The Effect of Contact with Natural Environments on Positive and Negative Affect: A Meta-Analysis.” The Journal of Positive Psychology 10 (6): 507–519. doi:10.1080/17439760.2014.994224.

- McPhearson, Timon, Christopher M Raymond, Natalie Gulsrud, Christian Albert, Neil Coles, Nora Fagerholm, Michiru Nagatsu, Anton Stahl Olafsson, Niko Soininen, and Kati Vierikko. 2021. “Radical Changes Are Needed for Transformations to a GOOD ANTHROPOCENE.” Npj Urban Sustainability 1 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1038/s42949-020-00011-9.

- Nesbitt, Lorien, Michael J. Meitner, Cynthia Girling, and Stephen R. J. Sheppard. 2019. “Urban Green Equity on the Ground: Practice-Based Models of Urban Green Equity in Three Multicultural Cities.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 44: 126433. doi:10.1016/j.ufug.2019.126433.

- Nisbet, Elizabeth K., John M. Zelenski, and Steven A. Murphy. 2009. “The Nature Relatedness Scale: Linking Individuals’ Connection with Nature to Environmental Concern and Behavior.” Environment and Behavior 41 (5): 715–740. doi:10.1177/0013916508318748.

- Nordh, Helena, Katinka H. Evensen, and Margrete Skår. 2017. “A Peaceful Place in the City – A Qualitative Study of Restorative Components of the Cemetery.” Landscape and Urban Planning 167: 108–117. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2017.06.004.

- Novotný, Petr, Eliška Zimová, Aneta Mazouchová, and Andrej Šorgo. 2021. “Are Children Actually Losing Contact with Nature, or Is It That Their Experiences Differ from Those of 120 Years Ago?” Environment and Behavior 53 (9): 931–952. doi:10.1177/0013916520937457.

- Ottosson, Johan, and Patrik Grahn. 2008. “The Role of Natural Settings in Crisis Rehabilitation: How Does the Level of Crisis Influence the Response to Experiences of Nature with Regard to Measures of Rehabilitation?” Landscape Research 33 (1): 51–70. doi:10.1080/01426390701773813.

- Peschardt, Karin Kragsig, and Ulrika Karlsson Stigsdotter. 2013. “Associations Between Park Characteristics and Perceived Restorativeness of Small Public Urban Green Spaces.” Landscape and Urban Planning 112: 26–39. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2012.12.013.

- Pink, Sarah. 2012. Situating Everyday Life: Practices and Places. London, UK: Sage Publications.

- Poortinga, Wouter, Natasha Bird, Britt Hallingberg, Rhiannon Phillips, and Denitza Williams. 2021. “The Role of Perceived Public and Private Green Space in Subjective Health and Wellbeing During and After the First Peak of the COVID-19 Outbreak.” Landscape and Urban Planning 211: 104092. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2021.104092.

- Raymond, Christopher M., Lynne C. Manzo, Daniel R. Williams, Andrés Di Masso, and Timo von Wirth, eds. 2021. Changing Senses of Place: Navigating Global Challenges. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Rigolon, Alessandro, and Travis L. Flohr. 2014. “Access to Parks for Youth as an Environmental Justice Issue: Access Inequalities and Possible Solutions.” Buildings 4 (2): 69–94. doi:10.3390/buildings4020069.

- Roberts, Hannah, Ian Kellar, Mark Conner, Christopher Gidlow, Brian Kelly, Mark Nieuwenhuijsen, and Rosemary McEachan. 2019. “Associations Between Park Features, Park Satisfaction and Park use in a Multi-Ethnic Deprived Urban Area.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 46: 126485. doi:10.1016/j.ufug.2019.126485.

- Rosaldo, Renato. 1993. Culture & Truth: The Remaking of Social Analysis. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

- Russell, Roly, Anne D. Guerry, Patricia Balvanera, Rachelle K. Gould, Xavier Basurto, Kai MA Chan, Sarah Klain, Jordan Levine, and Jordan Tam. 2013. “Humans and Nature: How Knowing and Experiencing Nature Affect Well-Being.” Annual Review of Environment and Resources 38: 473–502. doi:10.1146/annurev-environ-012312-110838.

- Salari, Nader, Amin Hosseinian-Far, Rostam Jalali, Aliakbar Vaisi-Raygani, Shna Rasoulpoor, Masoud Mohammadi, Shabnam Rasoulpoor, and Behnam Khaledi-Paveh. 2020. “Prevalence of Stress, Anxiety, Depression Among the General Population During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis.” Globalization and Health 16 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1186/s12992-019-0531-5.

- Skår, Margrete, and Erling Krogh. 2009. “Changes in Children’s Nature-Based Experiences Near Home: From Spontaneous Play to Adult-Controlled, Planned and Organised Activities.” Children’s Geographies 7 (3): 339–354. doi:10.1080/14733280903024506.

- Slater, Sandy J., Richard W. Christiana, and Jeanette Gustat. 2020. “Recommendations for Keeping Parks and Green Space Accessible for Mental and Physical Health During COVID-19 and Other Pandemics.” Preventing Chronic Disease 17. doi:10.5888/pcd17.200204.

- Soga, Masashi, Maldwyn J. Evans, Kazuaki Tsuchiya, and Yuya Fukano. 2021. “A Room with a Green View: The Importance of Nearby Nature for Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Ecological Applications 31 (2): e2248. doi:10.1002/eap.2248.

- Sonti, Nancy Falxa, Lindsay K. Campbell, Erika S. Svendsen, Michelle L. Johnson, and DS Novem Auyeung. 2020. “Fear and Fascination: Use and Perceptions of New York City’s Forests, Wetlands, and Landscaped Park Areas.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 49: 126601. doi:10.1016/j.ufug.2020.126601.

- Subiza-Pérez, Mikel, Kaisa Hauru, Kalevi Korpela, Arto Haapala, and Susanna Lehvävirta. 2019. “Perceived Environmental Aesthetic Qualities Scale (PEAQS) – A Self-Report Tool for the Evaluation of Green-Blue Spaces.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 43: 126383. doi:10.1016/j.ufug.2019.126383.

- Sykes, Eunyque. 2022. “Environmental Justice Beyond Physical Access: Rethinking Black American Utilization of Urban Public Green Spaces.” Environmental Sociology. doi:10.1080/23251042.2022.2057649.

- Teti, Michelle, Enid Schatz, and Linda Liebenberg. 2020. “Methods in the Time of COVID-19: The Vital Role of Qualitative Inquiries.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 19. doi:10.1177/1609406920920962.

- Tidball, Keith G. 2012. “Urgent Biophilia: Human-Nature Interactions and Biological Attractions in Disaster Resilience.” Ecology and Society 17 (2). doi:10.5751/ES-04596-170205.

- Ugolini, Francesca, Luciano Massetti, Pedro Calaza-Martínez, Paloma Cariñanos, Cynnamon Dobbs, Silvija Krajter Ostoić, Ana Marija Marin, et al. 2020. “Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the use and Perceptions of Urban Green Space: An International Exploratory Study.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 56: 126888. doi:10.1016/j.ufug.2020.126888.

- Ulrich, Roger S., Robert F. Simons, Barbara D. Losito, Evelyn Fiorito, Mark A. Miles, and Michael Zelson. 1991. “Stress Recovery During Exposure to Natural and Urban Environments.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 11 (3): 201–230. doi:10.1016/S0272-4944(05)80184-7.

- Van den Berg, Agnes E., Anna Jorgensen, and Edward R. Wilson. 2014. “Evaluating Restoration in Urban Green Spaces: Does Setting Type Make a Difference?” Landscape and Urban Planning 127: 173–181. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2014.04.012.

- Van den Berg, Agnes E., Jolanda Maas, Robert A. Verheij, and Peter P. Groenewegen. 2010. “Green Space as a Buffer Between Stressful Life Events and Health.” Social Science & Medicine 70 (8): 1203–1210. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.01.002.

- Van den Bosch, Matilda, and Å. Ode Sang. 2017. “Urban Natural Environments as Nature-Based Solutions for Improved Public Health – A Systematic Review of Reviews.” Environmental Research 158: 373–384. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2017.05.040.

- Verbrugge, Laura, Matthias Buchecker, Xavier Garcia, Sarah Gottwald, Stefanie Müller, Søren Præstholm, and Anton Stahl Olafsson. 2019. “Integrating Sense of Place in Planning and Management of Multifunctional River Landscapes: Experiences from Five European Case Studies.” Sustainability Science 14 (3): 669–680. doi:10.1007/s11625-019-00686-9.

- Wang, Dong, Gregory Brown, and Yan Liu. 2015. “The Physical and non-Physical Factors That Influence Perceived Access to Urban Parks.” Landscape and Urban Planning 133: 53–66. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2014.09.007.

- Wang, Ronghua, Jingwei Zhao, Michael J. Meitner, Yue Hu, and Xiaolin Xu. 2019. “Characteristics of Urban Green Spaces in Relation to Aesthetic Preference and Stress Recovery.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 41: 6–13. doi:10.1016/j.ufug.2019.03.005.

- Whitburn, Julie, Wayne Linklater, and Wokje Abrahamse. 2020. “Meta-Analysis of Human Connection to Nature and Proenvironmental Behavior.” Conservation Biology 34 (1): 180–193. doi:10.1111/cobi.13381.

- Williams, Daniel R. 2014. “Making Sense of ‘Place’: Reflections on Pluralism and Positionality in Place Research.” Landscape and Urban Planning 131: 74–82. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2014.08.002.

- Williams, Daniel R., and Joseph W. Roggenbuck. 1989. “Measuring Place Attachment: Some Preliminary Results.” In NRPA Symposium on Leisure Research, San Antonio, TX, Vol. 9.