ABSTRACT

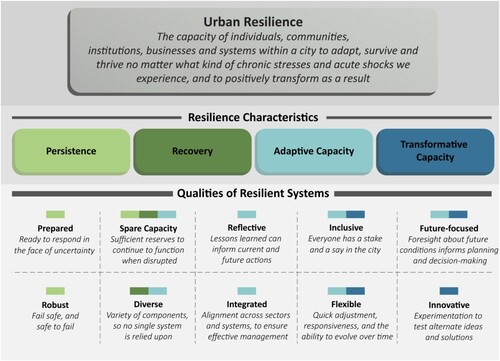

Urban resilience has rapidly developed as a concept to assist urban actors to prepare for, and respond to, shocks and stresses experienced in cities. Urban resilience has been variously defined, and abstract and nebulous resilience concepts can be difficult to apply in practice. Through a research-practice partnership we sought to clarify the concept of urban resilience and make it applicable to the multi-sectoral work of local government in Australia. By conducting a literature review and researcher-practitioner workshops, we developed an urban resilience framework to assist local government planning. We defined urban resilience from an evolutionary perspective: The capacity of individuals, communities, institutions, businesses and systems within a city to adapt, survive, and thrive no matter what kind of chronic stresses and acute shocks we experience, and to positively transform as a result. Evolutionary urban resilience has four characteristics: recovery, persistence, adaptive capacity and transformative capacity. We mapped these characteristics to 10 core qualities of resilient urban systems: prepared, robust, spare capacity, diverse, reflective, integrated, inclusive, flexible, future-focused, and innovative. Resilience-building focuses on designing, delivering and evaluating urban systems and programmes, to ensure that cities can respond and transform in the face of growing ecological, economic and social uncertainty. We discuss the various ways in which the framework has been applied by the City of Melbourne. The framework may be relevant to other jurisdictions in Australia and internationally, as it provides the basis for implementing resilience across government policy, projects and operations, and in partnership with communities and other stakeholders.

Key policy highlights

We developed a research-based and practice-relevant urban resilience framework for local government, consisting of the definition and qualities of resilient systems.

Urban resilience is the capacity of individuals, communities, institutions, businesses and systems within a city to adapt, survive and thrive no matter what kind of chronic stresses and acute shocks we experience, and to positively transform as a result.

We demonstrate how the framework is being applied by the City of Melbourne to communicate the concept to stakeholders and embed resilience across the council’s policies and operations.

1. Introduction

Given the rapid urbanisation of countries around the world, cities have become a focus for building resilience. Now home to the majority of the world’s population (United Nations Citation2018), urban areas are the source of 70 per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions, consume two-thirds of the world’s energy, and are major contributors to waste-generation, and environmental and biodiversity degradation (Münzel et al. Citation2021; Watts et al. Citation2021). Australia is one of the world’s most urbanised countries with almost 90 per cent of its population living in urban areas (Australian Bureau of Statistics Citation2019). This means that more people than ever before are dependent on interconnected city systems to survive and thrive. Urban resilience – the focus of this paper – concentrates on responses to disruptive events or issues that impact cities and towns (Ferguson, Wollersheim, and Lowe Citation2021). Cities face an increasing likelihood of disruption and change, including from global warming and the COVID-19 pandemic, and are a crucial part of local mitigation, response and adaptation efforts (Watts et al. Citation2021).

The concept of resilience is used in many different fields – from ecology, to geography, psychology, engineering, economics, politics, international relations, community development, environmental management, sustainable development, public health, urban planning and urban studies (Davoudi Citation2012). Resilience refers to the capacity to respond to disturbances, such as extreme weather events, health crises, environmental degradation and growing social inequalities. Yet there is no agreed definition or approach, despite recent efforts to create a consistent understanding in the academic literature (e.g. Meerow, Newell, and Stults Citation2016; Sanchez, van der Heijden, and Osmond Citation2018) and practice (e.g. the 100 Resilient Cities programme (Rockefeller Foundation Citation2021)). The ways in which the concept is used depends on the discipline or viewpoint adopted. In the policy and academic literature, resilience is often linked to sustainability in some way. For example, climate resilience is widely discussed as important for sustainable development, in terms of future-proofing urban areas, assets and neighbourhoods (Ferguson, Wollersheim, and Lowe Citation2021). However, the distinction between resilience and sustainable development is often unstated or unclear.

This paper aims to develop a research-based, practice-relevant urban resilience framework to inform local government policies, plans and programmes. We specifically consider the application of resilience concepts and qualities to local government in Australia – the closest level of government to community, with a leading role in local resilience planning. However, the findings may be relevant to other jurisdictions in Australia and internationally. The purpose was to determine a framework that reflects the resilience evidence-base; is applicable to the multi-sectoral work of local government; and could facilitate clear communication of the concept to diverse internal and external local government stakeholders. This research was conducted as part of the urban resilience and innovation research partnership between the City of Melbourne and The University of Melbourne (Melbourne Centre for Cities Citation2021). The co-funded partnership interrogates the relationships between urban decision-making and resilience, using action research to inform policy and practice.

2. Research-practice method

In early 2021, the City Resilience and Sustainable Futures team within the City of Melbourne identified the need to establish an agreed definition of resilience to inform their work with communities and across the local council. Melbourne had been part of the first group of cities to join the Rockefeller Foundation’s 100 Resilient Cities (100RC) Centennial Challenge in 2013, discussed in Section 3. The Resilient Melbourne programme operated until 2020 across the whole metropolitan region of Melbourne, involving 32 local governments. The transition from the metropolitan-wide Resilient Melbourne programme to the central municipal focus of the City of Melbourne provided an opportunity to review definitions and approaches to resilience, and reflect on recent experience of shocks and stresses such as bushfires and the COVID-19 pandemic.

As a collaboration between university-based researchers and local government officers, the research involved a review of recent academic and reputable grey literature, reflection on the strengths and limitations of definitions, frameworks and tools used by Resilient Melbourne and the 100RC network, and a series of workshops to explore and agree on an updated urban resilience framework. The literature review provided a narrative summary of the key resilience concepts and their application in urban policy and practice, as the foundation for research-practice workshops involving three university researchers and six City of Melbourne officers. The first workshop explored a range of definitions of resilience and its relationship to sustainable development, as a key priority for the City. The second workshop built on the first, to analyse resilience qualities and outline the structure and content of the agreed framework (Lowe et al. Citation2021). Workshop participants discussed and tested the relevance and application of the draft resilience qualities to real-world policy challenges facing the City of Melbourne. This paper synthesises the outcomes and early impacts of the project, starting with the literature review findings, before presenting the agreed resilience definition and framework and demonstrating how they have informed the development of the City’s resilience work programme.

3. The rise of urban resilience

Resilience has become a prominent topic for urban policy, practice and research since the turn of the millennium (Davidson et al. Citation2019). It emerged at the intersection of urban sustainability, urban security, risk and disaster management, and infrastructure systems engineering. Urban resilience considers how cities can best avoid, prepare for, and respond to things that might go wrong. The relatively recent policy interest in resilience is partly a response to escalating ecological and social disruption and heightened risk of disasters such as extreme weather events and pandemics (Gleeson Citation2013; Naughtin et al. Citation2022). Resilience has been increasingly embedded in security policy and politics, including managing risks to urban areas and infrastructure (Ferguson, Wollersheim, and Lowe Citation2021; Gleeson Citation2013). However, resilience has gained traction across a range of sectors that shape urban systems and at all levels, from global agencies through to local governments, and in the community and private sectors (Ferguson, Wollersheim, and Lowe Citation2021; Laurien, Martin, and Mehryar Citation2022).

The Rockefeller Foundation’s 100RC programme represents one considerable effort to improve the urban resilience of cities and regions. Starting in 2013, this global programme provided member cities with “resources necessary to develop a roadmap to resilience” (Rockefeller Foundation Citation2021, unpaginated). The 100RC programme was based on the premise that three converging global megatrends – climate change, urbanisation, and globalisation – are impacting local communities across the world. In Australia, Melbourne and Sydney were both part of 100RC and now participate in its legacy, the Resilient Cities Network (Resilient Cities Network Citation2021a). The programme helped revitalise urban resilience efforts and promoted resilience thinking across different levels of government in Australia. For example, Melbourne produced, among other things, a number of key resilience policies and resources, including the Resilient Melbourne metropolitan-wide, intergovernmental strategy (Resilient Melbourne Citation2016), Living Melbourne: our metropolitan urban forest strategy (The Nature Conservancy and Resilient Melbourne Citation2019), and resilience training and workshops. This work has helped to share and build knowledge on resilience across metropolitan Melbourne and beyond.

Embedding resilience thinking within local government has increased in importance in recent years as Australian cities have responded to shocks such as the COVID-19 pandemic, flooding and bushfires. Local governments are key agents for resilience building, with an emphasis on place-based actions tailored to the particular challenges facing local communities (Torabi, Dedekorkut-Howes, and Howes Citation2017). To track the purpose of urban resilience thinking and policy, it is necessary to ask: resilience to what, of what and for whom?

3.1 Resilient to what?

Urban resilience focuses on the impact and responses to shocks and stresses in cities and towns. Shocks are acute or sudden events, including heatwaves, bushfires, floods, pandemics, and extremist acts (Resilient Melbourne Citation2016). Stresses are long-term and chronic “challenges that weaken the fabric of a city on a day-to-day or cyclical basis. Examples include sea level rise, increasing pressures on healthcare services, unemployment, and deeper social inequality” (Resilient Melbourne Citation2016, 11). Shocks and stresses can be linked (e.g. bushfire leading to increased mental health issues) and co-occurrences can exacerbate challenges or generate new ones (Lowe et al. Citation2023). For example, the COVID-19 pandemic is a shock that has exposed and intensified existing issues such as homelessness, area-level disadvantage, and lack of access to green space.

Timeframes are important, because a focus on resilience to short term disruptions may emphasise survival and persistence, while a longer-term perspective may require some form of system transition (Meerow and Newell Citation2019). Also, urban systems can be made resilient to specific shocks and stresses (e.g. heatwaves, bushfires, flooding, pandemics, social inequalities) or have a more general capacity to adapt and respond to all known and unknown disruptions. A balance between the two is key. Systems need to effectively respond to specific threats and current conditions, without this limiting general capacity to adapt to future conditions (Meerow and Newell Citation2019; Meerow, Newell, and Stults Citation2016).

3.2 Resilience of what?

This is a key question when building resilience in specific urban contexts, and often without an easy answer. Cities are increasingly understood as complex adaptive systems, with a series of parts that are both independent (self-organising) and interdependent (interacting with other parts) at the same time (Dovey Citation2016; Walker and Salt Citation2006). There is great diversity in the structure, form, governance, function and experiences of cities. Resilience-building can focus on different urban systems and sub-systems and their connections (discussed further in Section 5) depending on the aims and scope of strategies or projects, the specific urban context, as well as the concept of resilience adopted. To help identify and consider what elements of a city need to be the focus of resilience-building, the City Resilience Framework developed for the 100RC programme described four inter-related dimensions or sub-systems that contribute to resilience: Health & Wellbeing (incorporating essential and public health services and livelihood support); Economy & Society; Infrastructure & Environment; and Leadership & Strategy (Rockefeller Foundation and Arup Citation2015).

The resilience implications of complex and interconnected urban systems and areas must be considered and planned for (da Silva, Kernaghan, and Luque Citation2012; Fastiggi, Meerow, and Miller Citation2021). For example, it can be difficult to define system boundaries, including which aspects of geographic regions, populations, infrastructures, social structures and/or resource flows are included in the “urban” or the “city” (Meerow and Newell Citation2019; Meerow, Newell, and Stults Citation2016). Urban resilience may be heavily influenced by a city’s interdependence with its hinterland or peri-urban areas. Cities are more connected than ever to distant places through exchange of materials, food, water, energy and capital (Meerow, Newell, and Stults Citation2016). Planning according to formal city boundaries may not reflect the way that urban systems operate or are impacted by shocks and stresses. Likewise, sub-areas of cities (e.g. local governments or suburbs) cannot be separated from their wider context. For example, Melbourne and other Australian state capital cities are made up of multiple local governments, so building resilience across the metropolitan region requires an understanding of the interconnections between local governments and the need for cross-government coordination (Fastenrath and Coenen Citation2021). Whole-of-system thinking is needed to help avoid activities in one sector having unintended negative consequences on other urban systems.

3.3 Resilience for whom?

Urban resilience efforts should carefully consider potential social equity impacts, and prioritise the needs of the most vulnerable. If equity is inadequately considered within resilience frameworks, it is likely to reproduce unjust outcomes within and between communities (Biermann et al. Citation2016; Cretney Citation2014). For example, resilience approaches that place the burden of responsibility for risk management on communities, in alignment with neoliberal policies to reduce government responsibility, have the potential to increase social disparities (Meerow and Newell Citation2019). This is because the most disadvantaged groups may be at greater risk and have the least resources to respond to shocks and stresses. Local governments therefore need to work with and advocate for communities to ensure responses are inclusive and reduce inequities.

Another important consideration for intergenerational justice is how resilience-building for the present might impact future generations. Some interpretations of resilience downplay the underlying social causes of disturbances (e.g. climate change-related extreme weather events, economic recession, housing affordability crisis), creating barriers to preventing future crises from occurring. For example, a need for climate mitigation through reducing greenhouse gas emissions is under-acknowledged in the urban resilience literature (Borquez, Aldunce, and Alder Citation2017). Disasters and inequalities are sometimes framed as inevitable, with a focus on communities adapting to these conditions rather than resisting or addressing the cause (Reid Citation2012; Wamsler Citation2014). This can exacerbate social inequities. Concepts of resilience that see the possibility for system transformation better incorporate equity considerations and the need for mitigation alongside adaptation to shocks and stresses (see Section 4.3).

4. Urban resilience concepts and definitions

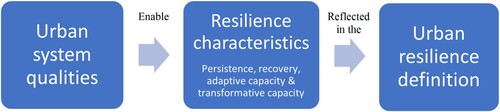

Urban resilience has been conceptualised in three main ways in the academic and policy literature: original concepts of “bouncing back” resilience have progressed to ecological resilience, as a conceptual stepping-stone to evolutionary resilience (Ferguson, Wollersheim, and Lowe Citation2021). The main tenets of these concepts are discussed below and summarised in . Across the world, local government have generally followed these three concepts in their approaches to planning for resilience (Torabi, Dedekorkut-Howes, and Howes Citation2017).

Table 1. Main concepts of urban resilience in the international literature (adapted from Ferguson, Wollersheim, and Lowe Citation2021).

4.1 Bouncing back resilience

Bouncing back resilience, originally termed “engineering resilience”, emphasises the importance of urban systems rebounding from a shock or stress (Holling Citation1996). Success is measured in terms of how quickly the return to a previous state can be achieved (Davoudi Citation2012; Sanchez, van der Heijden, and Osmond Citation2018; Suárez, Gómez-Baggethun, and Onaindia Citation2020). The key characteristics of bouncing back resilience are persistence under stress and efficient recovery (Davoudi Citation2012; Gunderson Citation2000; Holling Citation1996). This is reflected in resilience definitions such as, “[t]he ability of a system or organisation to withstand and recover from adversity” (Cabinet Office Citation2011, 10).

Bouncing back resilience focuses on making urban populations and physical infrastructure (e.g. buildings) more resilient, through reactively managing specific, identified risks such as an extreme weather event or terrorist attack (Davoudi Citation2012; Funfgeld and McEvoy Citation2012). This perspective does not address whether returning to a pre-disruption state and maintaining the status quo is desirable or achievable, which may not be the case, especially in the face of chronic issues such as climate change and social inequality (Ferguson, Wollersheim, and Lowe Citation2021; Sanchez, van der Heijden, and Osmond Citation2018).

Bouncing back remains a common feature of resilience discourse in urban policy and disaster management (Davoudi Citation2012; Meerow and Stults Citation2016; White and O'Hare Citation2014). For example, Meerow and Stults (Citation2016, 1) found that US local government representatives “tend to favour potentially problematic “bouncing back” or engineering-based definitions of resilience”. This threatens to hinder the transformative potential of urban resilience as bouncing back resilience does not capture the dynamic complexity of cities, including the potential to actively transform urban areas in response to disruption (Ferguson, Wollersheim, and Lowe Citation2021).

4.2 Ecological resilience

Ecological resilience recognises the possibility of “bouncing forward” to a new steady-state in response to disturbances (Adil and Audirac Citation2020; Davoudi Citation2012; Leichenko Citation2011; Meerow and Newell Citation2019; White and O'Hare Citation2014). The focus is not just on recovery, but also some degree of adaptation and change of urban systems, “accepting that it is not always possible or desirable to return to previous conditions” (Meerow and Stults Citation2016, 5). Originating in ecology, when applied to urban areas, this perspective focuses on making urban-based ecosystems and human-environmental systems more resilient, in keeping with contemporary understandings of cities as complex systems (Adil and Audirac Citation2020; da Silva, Kernaghan, and Luque Citation2012; Davoudi Citation2012; Leichenko Citation2011). However, it does not recognise the dynamic, ever-changing quality of urban systems such as housing, transport and land uses, and the potential for them to be transformed (Ferguson, Wollersheim, and Lowe Citation2021; Sanchez, van der Heijden, and Osmond Citation2018).

Ecological resilience is articulated in a range of policy and urban research fields (Borie et al. Citation2019; Ferguson, Wollersheim, and Lowe Citation2021; Meerow, Newell, and Stults Citation2016; Ribeiro and Gonçalves Citation2019). Examples include the UN Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030 with its concept of “Build Back Better” (United Nations Citation2015). The UN New Urban Agenda also commits to “ … support shifting from reactive to more proactive risk-based, all-hazards and all-of-society approaches [to] … build resilience” (United Nations Citation2016, 11).

4.3 Evolutionary resilience

Evolutionary resilience most fully reflects the idea of cities as complex, dynamic, emergent systems, “constantly changing in an often-unforeseeable way” (Sanchez, van der Heijden, and Osmond Citation2018, 5). This perspective is inherently future-oriented, seeing the possibility for urban system adaptation and transformation – in addition to persistence and recovery – in response to current or predicted disturbances (Ferguson, Wollersheim, and Lowe Citation2021; Gunderson and Holling Citation2002; White and O'Hare Citation2014). Disruption is therefore viewed as “an opportunity to re-build the city into an optimised or improved system” (Sanchez, van der Heijden, and Osmond Citation2018, 5). This can include re-building and transforming cities and towns in ways that prevent or mitigate shocks and stresses and improve social equity, where possible. Evolutionary resilience, referred to by some as socioecological resilience, encompasses the multi-level, interconnected, social, institutional, cultural and physical urban systems, with a greater focus on interactions between societal and ecological systems than the other concepts of urban resilience (Ferguson, Wollersheim, and Lowe Citation2021; White and O'Hare Citation2014).

Evolutionary resilience is increasingly prominent in the academic literature (e.g. Meerow, Newell, and Stults Citation2016) and has been embraced by some institutions such as the Resilience Alliance (Sanchez, van der Heijden, and Osmond Citation2018), and the Transition Towns movement (Shaw Citation2012). The Rockefeller Foundation’s 100RC programme developed a definition of resilience that was at least partly evolutionary in nature (Allen et al. Citation2020; Sanchez, van der Heijden, and Osmond Citation2018). This definition was subsequently adopted in the resilience strategies of cities that were part of the programme, including Resilient Melbourne (Resilient Melbourne Citation2016). UN-Habitat (Citation2021, unpaginated) understands resilience as “the ability of any urban system to maintain continuity through all shocks and stresses while positively adapting and transforming towards sustainability”. While the capacity for a system to maintain continuity during periods of disruption and transformation could be questioned, this definition reflects the general concept of evolutionary resilience. Based on an extensive review of the resilience literature, Meerow, Newell, and Stults (Citation2016) developed a comprehensive evolutionary-type resilience definition:

Urban resilience refers to the ability of an urban system – and all its constituent socio-ecological and socio-technical networks across temporal and spatial scales – to maintain or rapidly return to desired functions in the face of a disturbance, to adapt to change, and to quickly transform systems that limit current or future adaptive capacity.

4.4 A resilience definition for local government

The discussion above has demonstrated the various ways that resilience has been conceptualised and defined in research and practice, with evolutionary resilience being the most dynamic and holistic understanding, and therefore most suitable for local governments’ key role in resilience planning and responding to local community needs. Our first research-practice workshop developed a practice-focused definition adapted from the global Resilient Cities Network (Citation2021b) of cities that are committed to building and investing in urban resilience. We defined resilience as:

The capacity of individuals, communities, institutions, businesses and systems within a city to adapt, survive and thrive no matter what kind of chronic stresses and acute shocks we experience, and to positively transform as a result.

We developed supporting commentary for our definition to help describe the concept to City of Melbourne stakeholders, and foreground sustainable development and social justice as key purposes of resilience-building processes:

Resilience thinking enables us to learn from past experiences as well as prepare for known or unknown future risks, so that we can positively transform towards a more sustainable and just future.

5. Qualities of resilience

The key characteristics of evolutionary urban resilience – persistence, recovery, adaptive capacity and transformative capacity – are enabled by system attributes or qualities (Gunderson and Holling Citation2002; Meerow and Stults Citation2016) (). Urban sub-systems (e.g. energy, housing, parks, transport, food, healthcare, emergency services), and complex city systems as a whole can exhibit these qualities.

In the resilience literature, a range of resilience qualities are proposed. The various attempts by organisations and researchers to summarise and distil these qualities have resulted in different but overlapping lists of qualities and their definitions. For example, Wilkinson’s (Citation2012, 162) urban planning-focused “strategies for resilience” framework incorporated 13 system qualities, ranging from buffering and redundancy to strategic foresight, ecological diversity, and multiscale networks and connectivity. A 2016 review of the academic literature identified 16 qualities of urban systems that foster resilience, with a survey of US local government officials indicating that all of these qualities were important (Meerow and Stults Citation2016). A subsequent literature review by Ribeiro and Gonçalves (Citation2019) selected 11 qualities that make urban systems more resilient: redundancy, diversity, efficiency, robustness, connectivity, adaptation, resources, independence, innovation, inclusion and integration.

Based on extensive research, the Rockefeller Foundation’s 100RC programme developed a list of seven qualities demonstrated by resilient urban systems () (Rockefeller Foundation and Arup Citation2015). While concise, these qualities are reasonably comprehensive, and map to the key characteristics () and our evolutionary-type definition of urban resilience. However, based on the wider literature, we determined that there were some gaps in these qualities, which we address below.

Table 2. Adaptation of the 100RC programme’s resilience qualities.

Table 3. Definitions of resilience qualities and the resilience characteristics they enable.

5.1 Resilience qualities for local government

Using the 100RC resilience qualities as a starting point, our second research-practice workshop defined a list of qualities aligned with the literature and chosen definition of resilience outlined above; and which could facilitate resilience work and communication with local government stakeholders. For this latter objective, we aimed for the qualities’ definitions to focus on urban systems and structures and avoid deflecting responsibility to individuals. We also wanted them to be comprehensive but also mutually exclusive to avoid confusion caused by overlap between qualities.

The result was an expanded list of 10 resilience qualities (). To improve comprehensiveness and reflect resilience qualities in other literature (Meerow and Stults Citation2016; Ribeiro and Gonçalves Citation2019), four qualities were added: prepared, diverse, innovative and future-focused. The latter two round out the qualities, to enable “transformative capacity” more strongly. “Prepared” was added to reflect the increasing likelihood of disruption in cities, and the need to anticipate shocks and stresses to reduce their negative impacts. “Redundant” was replaced by “spare capacity”, while still retaining the essential idea of having surplus capacity in urban systems. “Resourceful” was not included as a separate quality, as it was deemed to overlap with other qualities. However, this term was explicitly mentioned in the definition of the new “innovative” quality, emphasising resourcefulness of institutions and systems rather than individual responsibility during times of crisis. summarises our finalised definitions of the 10 qualities, and how they map to the key characteristics of evolutionary resilience.

These qualities can be embedded in the planning, policies, operations, projects and structures of urban sub-systems at various scales, from neighbourhoods through to whole cities. There is no single predetermined way of achieving a resilient city, particularly given the diversity of urban contexts and experiences internationally. However, the urban system qualities paint a picture of how the elements that comprise a city can contribute to its resilience (Redman Citation2014).

We determined that the aim of resilience-building is to create cities that are socially equitable, inclusive and cohesive, with affordable, energy-efficient housing, diverse economic activity, and safe, walkable neighbourhoods where people can access open space, public transport, employment, education, and services. Resilience-building should also ensure that infrastructure meets basic needs, ecosystems are sound, natural resources are used sustainably, land use policy is coherent and future-focused, government leadership and management is transparent and strategic, and innovation is encouraged (OECD Citation2021; Rockefeller Foundation and Arup Citation2015). A resilient city is prepared for and prevents expected and unexpected shocks and stresses. There are some similarities between this notion of a resilient city and the concept of liveability, highlighting potential opportunities for co-benefits (Lowe et al. Citation2015).

6. An urban resilience framework

By combining the definition, characteristics, and qualities of resilience discussed in this paper, a comprehensive framework for urban resilience was developed (). This framework clarifies the concept of resilience, to facilitate communication to multiple stakeholders and application of the concept within the multi-sectoral work of local government.

To work towards the transformative vision set out in the urban resilience definition, a local government practitioner could use the framework to consider how to develop and embed the resilience qualities in the sector(s) in which they work, including ensuring that strategic, project and operational processes reflect the resilience qualities (e.g. they are inclusive). Practitioners and the public need to recognise that being prepared for and managing change will require difficult trade-offs and decisions about resource allocation, dealing with uncertainty, and incremental through to profound alterations to how things are done now.

Initial consideration may need to be given to what needs to be made more resilient: which urban sub-systems, in which areas, and involving which communities, organisations and businesses. In keeping with the integration quality, links and interdependencies between sub-systems and areas should be considered, rather than focussing on sectors in isolation. Local government practitioners should also consider which shocks and stresses they need to prepare for and respond to; being conscious of interrelationships between various shocks/stresses, and the need to build resilience to current risks but also unknown future risks. As outlined in this paper, it is also important to harness the opportunity to transform cities towards social equity and mitigation of risks, by collectively pursuing all 10 resilience qualities. The framework encapsulates the need for climate change mitigation alongside adaptation, by including both adaptive capacity and transformative capacity as resilience characteristics enabled by the various system qualities.

Local governments have a key role in building resilient cities and towns, but they cannot undertake this huge task alone. Individual local governments have limited resources and remit, and comprehensive resilience-building requires integrated governance with shared commitment and responsibility across and between all levels of government, and the community and private sectors (Berke et al. Citation2019; Fastiggi, Meerow, and Miller Citation2021; Lowe, Whitzman, and Giles-Corti Citation2018). The urban resilience framework could assist integrated urban resilience planning at various scales, from neighbourhoods and local governments, through to metropolitan, state and national scales.

7. Application of the framework by City of Melbourne

7.1 Communicating the concept to internal and external stakeholders

The framework has been applied by the City of Melbourne in a range of ways. First, in keeping with one of the original purposes for developing the framework, it has proved useful for communicating the concept to City of Melbourne Councillors and staff, and to external stakeholders. The framework was launched in the form of an Issues Paper and Briefing Paper in November 2021 (Lowe et al. Citation2021), with the Deputy Lord Mayor presenting at the launch, which was also attended by other city Councillors. The framework has subsequently been a communication tool used by council administrators to help foster a consistent understanding of what resilience-building entails.

7.2 Informing new research questions

The urban resilience framework has also been the springboard for further applied resilience research co-produced by our university-local government partnership. Two examples demonstrate this application. First, the framework’s resilience definition and inclusion of the “prepared” quality, seeded an important research question for the City of Melbourne: what are the priority shocks and stresses that the municipality should prepare for? This led to a research project to identify from the literature and stakeholder workshops, the top shocks and stresses that the City of Melbourne should prepare for and prevent over the next five to ten years (Lowe et al. Citation2023).

Second, the resilience framework has been used in a research project to assess how resilience is reflected in the City of Melbourne’s localised United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs). In parallel to the focus on urban resilience, the City of Melbourne has a cross-council commitment to sustainable development. Accordingly, the City of Melbourne completed a Voluntary Local Review of the UN SDGs in 2022, which included developing localised SDG targets and indicators for reporting and tracking the municipality’s performance (City of Melbourne Citation2022). The research involved assessing which resilience qualities were reflected in each of the localised SDG indicators. This enabled recommendations to be made, to better align the council’s monitoring of sustainable development and resilience (Lowe et al. Citation2023).

7.3 A tool for embedding resilience

Further, the framework has been applied as a practical tool for ensuring resilience qualities are embedded in council operations and programmes aimed at addressing shocks and stresses. For example, a major initiative on community disaster resilience aims to better prepare City of Melbourne’s communities for heatwaves and other shocks and stresses (City of Melbourne Citation2021a). Heatwaves are a priority issue in Melbourne, as they are expected to increase both in length and severity due to climate change (City of Melbourne Citation2018). The City of Melbourne project team applied the resilience framework during the initiative’s ideation and planning phase, to ensure that processes and actions to address heatwaves comprehensively embedded resilience qualities across urban sub-systems, neighbourhoods, communities and organisations.

The initiative strongly reflects the quality of being prepared, aiming to build community and organisational capacity in heatwave disaster response. It applies an integrated approach, working closely with state government and community organisations to complement and build on existing emergency management information, projects and infrastructure. To help unify responses to heat risk, the City of Melbourne has appointed Chief Heat Officers in partnership with the Adrienne Arsht-Rockefeller Foundation Resilience Center (City of Melbourne Citation2023). Inclusion is a vital aspect of the project, as it involves identifying population groups most vulnerable to extreme heat, emerging needs through community engagement, and enabling community-led solutions. For example, the City of Melbourne has implemented a homelessness and heatwaves programme to provide vulnerable people with heat respite options (City of Melbourne Citation2023). Flexibility is key to accelerating heat resilience, with the appointment of the Chief Heat Officers being an acknowledgment that this complex and evolving problem requires an iterative and reflective approach.

Applying the resilience qualities during the initiative planning helped to identify gaps that needed to be addressed, as well as alignment with other City of Melbourne projects. For example, the initiative acknowledges the need to make infrastructure more robust in the face of heatwaves, including ensuring the thermal comfort of apartments. Adaptive responses will also need to include a diversity of options on high heat days, including promoting existing programmes such as Cool Routes, a digital wayfinding tool showing the coolest transport route through the city (City of Melbourne Citation2021b); and Cool Places, an interactive map to identify cool places in the city to take refuge from the heat. Innovations will be tested, such as microclimate sensors, which use real time data to determine which parts of the city are hottest; and the Green Factor Tool to help with designing new buildings that are environmentally friendly. The four-year initiative is future-focused, ensuring actions have co-benefits for climate change mitigation, social inclusion and health and wellbeing.

7.4 Next steps

To further develop the institutional commitment and capacity to build resilience, the City of Melbourne is currently developing training for staff across all areas of council. This training is based upon the resilience framework outlined in this paper. The framework is also informing the design of workshops that will be run with City of Melbourne staff, to help bring a resilience lens to the planning of new projects and programmes. The University of Melbourne-City of Melbourne urban resilience and innovation research partnership will continue to co-produce research that helps build the resilience of the City of Melbourne. This provides the opportunity to learn from experience and evaluate and refine resilience-building endeavours, in keeping with reflective, flexible and future-focused practice. The resilience framework can be reviewed and adapted as needed over time to reflect changing evidence and applications of the concept.

8. Conclusion

Urban resilience as a concern for local government has emerged recently and developed rapidly (Davidson et al. Citation2019; Gleeson Citation2013). For cities to thrive through the good times and be stronger during and after tough times, there must be careful consideration of resilience to what, of what, and for whom (Meerow and Newell Citation2019). Early conceptions of resilience as the capacity for systems to “bounce-back” from shocks and stresses, have matured to consider opportunities to “bounce-forward” and transform (Davoudi Citation2012). This paper has provided a synthesis of current resilience thinking as it is relevant to local government in Australia. An understanding of resilience as a dynamic, evolutionary process provides the foundation for a definition that emphasises adaptation and transformation of urban systems, as well as recovery and persistence in response to shocks and stresses.

Our urban resilience framework, consisting of the definition and qualities of resilient systems, can help with implementing resilience across government policy and operations, in partnership with communities and other stakeholders. We have specifically explored the framework’s application by the City of Melbourne. However, it could also assist other jurisdictions in Australia and internationally to clarify and communicate the concept of resilience, embed resilience qualities in city planning and indicator frameworks, and develop training and research into resilience challenges and capabilities. Close collaboration between researchers and practitioners enabled the co-production of our policy-relevant urban resilience framework and ensured its uptake by the City of Melbourne. Through an innovative partnership, our applied research brought together academic expertise and local government knowledge of resilience roadblocks, opportunities, and decision-making realities. Governments in other cities could similarly partner with local universities to undertake action research that addresses resilience priorities. A shared understanding of the core concepts and purpose of resilience across government, communities and stakeholders, grounded in international experience and research, is the foundation for ongoing conversations and actions to prepare cities for future threats and opportunities to thrive.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adil, A., and I. Audirac. 2020. “Urban Resilience: A Call to Reframing Planning Discourses.” In Routledge Handbook of Urban Resilience, edited by M. Burayidi, A. Allen, J. Twigg, and C. Wamsler, 35–46. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Allen, A., J. Twigg, M. Burayidi, and C. Wamsler. 2020. “Urban Resilience: State of the Art and Future Prospects.” In Routledge Handbook of Urban Resilience, edited by M. Burayidi, A. Allen, J. Twigg, and C. Wamsler, 476–487. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2019. “Historical Population.” Australian Bureau of Statistics, Accessed December 4. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/historical-population/latest-release.

- Berke, P. R., M. L. Malecha, S. Yu, J. Lee, and J. H. Masterson. 2019. “Plan Integration for Resilience Scorecard: Evaluating Networks of Plans in six US Coastal Cities.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 62 (5): 901–920. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2018.1453354.

- Biermann, M., K. Hillmer-Pegram, C. Noel Knapp, and R. Hum. 2016. “Approaching a Critical Turn? A Content Analysis of the Politics of Resilience in Key Bodies of Resilience Literature.” Resilience 4 (2): 59–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/21693293.2015.1094170.

- Borie, M., M. Pelling, G. Ziervogel, and K. Hyams. 2019. “Mapping Narratives of Urban Resilience in the Global South.” Global Environmental Change 54: 203–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2019.01.001.

- Borquez, R., P. Aldunce, and C. Alder. 2017. “Resilience to Climate Change: From Theory to Practice Through Coproduction of Knowledge in Chile.” Sustainability Science 12 (1): 163–176. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-016-0400-6.

- Cabinet Office. 2011. Strategic National Framework on Community Resilience. London: Cabinet Office.

- City of Melbourne. 2018. Climate Change Mitigation Strategy to 2050. Melbourne, Australia: City of Melbourne.

- City of Melbourne. 2021a. City of Melbourne City of Possibility: Council Plan 2021-2025. Melbourne, Australia: City of Melbourne.

- City of Melbourne. 2021b. “Cool Routes.” City of Melbourne, Accessed October 20. https://www.coolroutes.com.au/.

- City of Melbourne. 2022. United Nations Sustainable Development Goals: City of Melbourne Voluntary Local Review 2022. Melbourne, Australia: City of Melbourne.

- City of Melbourne. 2023. “Heatwaves.” City of Melbourne. Accessed January 6. https://www.melbourne.vic.gov.au/community/safety-emergency/emergency-management/Pages/heatwaves.aspx.

- Cretney, R. 2014. “Resilience for Whom? Emerging Critical Geographies of Socio-ecological Resilience.” Geography Compass 8 (9): 627–640. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12154.

- da Silva, J., S. Kernaghan, and A. Luque. 2012. “A Systems Approach to Meeting the Challenges of Urban Climate Change.” International Journal of Urban Sustainable Development 4 (2): 125–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/19463138.2012.718279.

- Davidson, K., T. M. P. Nguyen, R. Beilin, and J. Briggs. 2019. “The Emerging Addition of Resilience as a Component of Sustainability in Urban Policy.” Cities 92: 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2019.03.012.

- Davoudi, S. 2012. “Resilience: A Bridging Concept or a Dead end?” Planning Theory & Practice 13 (2): 299–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2012.677124.

- Dovey, K. 2016. Urban Design Thinking: A Conceptual Toolkit. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Fastenrath, S., and L. Coenen. 2021. “Future-proof Cities Through Governance Experiments? Insights from the Resilient Melbourne Strategy (RMS).” Regional Studies 55 (1): 138–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2020.1744551.

- Fastiggi, M., S. Meerow, and T. R. Miller. 2021. “Governing Urban Resilience: Organisational Structures and Coordination Strategies in 20 North American City Governments.” Urban Studies 58 (6): 1262–1285. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098020907277.

- Ferguson, P., L. Wollersheim, and M. Lowe. 2021. “Approaches to Climate Resilience: Mapping the Main Discourses.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Climate Resilient Societies, edited by R. Brears, 1–25. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Funfgeld, H., and D. McEvoy. 2012. “Resilience as a Useful Concept for Climate Change Adaptation?” Planning Theory & Practice 13 (2): 224–328. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2012.677124.

- Gleeson, B. 2013. “Resilience and its Discontents.” Research Paper No. 1. Melbourne, Australia: Melbourne Sustainable Society Institute, The University of Melbourne.

- Gunderson, L. H. 2000. “Ecological Resilience—In Theory and Application.” Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 31 (1): 425–439. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.31.1.425.

- Gunderson, L. H., and C. S. Holling. 2002. Panarchy: Understanding Transformations in Human and Natural Systems. Washington, DC: Island Press.

- Holling, C. S. 1996. “Engineering Resilience Versus Ecological Resilience.” In Engineering Within Ecological Constraints, edited by P. C. Schulze, 31–44. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

- Laurien, Finn, Juliette G. C. Martin, and Sara Mehryar. 2022. “Climate and Disaster Resilience Measurement: Persistent Gaps in Multiple Hazards, Methods, and Practicability.” Climate Risk Management 37: 100443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crm.2022.100443.

- Leichenko, R. 2011. “Climate Change and Urban Resilience.” Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 3 (3): 164–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2010.12.014.

- Lowe, M., S. Bell, J. Briggs, E. McMillan, M. Morley, M. Grenfell, D. Sweeting, A. Whitten, and N. Jordan. 2021. Urban Resilience for Local Government: Concepts, Definitions and Qualities. Melbourne, Australia: Melbourne Centre for Cities, The University of Melbourne.

- Lowe, M., E. McMillan, M. Grenfell, D. Sweeting, and S. Bell. 2023a. City Resilience: Acute Shocks and Chronic Stresses for Melbourne. Melbourne, Australia: Melbourne Centre for Cities, The University of Melbourne.

- Lowe, M., M. Roberts, M. Doak, and S. Bell. 2023b. Urban Resilience and Localised Sustainable Development Goals: City of Melbourne and International Case Studies. Melbourne, Australia: Melbourne Centre for Cities, The University of Melbourne.

- Lowe, M., C. Whitzman, H. Badland, M. Davern, L. Aye, D. Hes, I. Butterworth, and B. Giles-Corti. 2015. “Planning Healthy, Liveable and Sustainable Cities: How Can Indicators Inform Policy?” Urban Policy and Research 33 (2): 131–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/08111146.2014.1002606.

- Lowe, M., C. Whitzman, and B. Giles-Corti. 2018. “Health-promoting Spatial Planning: Approaches for Strengthening Urban Policy Integration.” Planning Theory & Practice 19 (2): 180–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2017.1407820.

- Meerow, S., and J. P. Newell. 2019. “Urban Resilience for Whom, What, When, Where, and why?” Urban Geography 40 (3): 309–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2016.1206395.

- Meerow, S., J. P. Newell, and M. Stults. 2016. “Defining Urban Resilience: A Review.” Landscape and Urban Planning 147: 38–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2015.11.011.

- Meerow, S., and M. Stults. 2016. “Comparing Conceptualizations of Urban Climate Resilience in Theory and Practice.” Sustainability 8 (7): 701. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8070701.

- Melbourne Centre for Cities. 2021. “Urban Resilience and Innovation.” Melbourne Centre for Cities, The University of Melbourne, Accessed June 20. https://sites.research.unimelb.edu.au/cities/projects/urban-resilience-innovation.

- Münzel, T., M. Sørensen, J. Lelieveld, O. Hahad, S. Al-Kindi, M. Nieuwenhuijsen, B. Giles-Corti, A. Daiber, and S. Rajagopalan. 2021. “Heart Healthy Cities: Genetics Loads the Gun but the Environment Pulls the Trigger.” European Heart Journal 42 (25): 2422–2422. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab235.

- The Nature Conservancy, and Resilient Melbourne. 2019. Living Melbourne: Our Metropolitan Urban Forest. Melbourne: The Nature Conservancy and Resilient Melbourne.

- Naughtin, C., S. Hajkowicz, E. Schleiger, A. Bratanova, A. Cameron, T. Zamin, and A. Dutta. 2022. Our Future World: Global Megatrends Impacting the way we Live Over Coming Decades. Brisbane, Queensland: CSIRO.

- OECD. 2021. “Resilient Cities.” OECD, Accessed August 18. https://www.oecd.org/cfe/regionaldevelopment/resilient-cities.htm.

- Redman, C. L. 2014. “Should Sustainability and Resilience be Combined or Remain Distinct Pursuits?” Ecology and Society 19 (2): 37–45. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-06390-190237.

- Reid, J. 2012. “The Disastrous and Politically Debased Subject of Resilience.” Development Dialogue 58 (1): 67–79.

- Resilient Cities Network. 2021a. “Our Story.” Resilient Cities Network, Accessed 20 January. https://resilientcitiesnetwork.org/our-story/.

- Resilient Cities Network. 2021b. “What is Urban Resilience?” Resilient Cities Network, Accessed 20 January. https://resilientcitiesnetwork.org/what-is-resilience/.

- Resilient Melbourne. 2016. Resilient Melbourne Strategy: Viable, Sustainable, Liveable, Prosperous. Melbourne, Australia: Resilient Melbourne.

- Ribeiro, P. J. G., and L. A. P. J. Gonçalves. 2019. “Urban Resilience: A Conceptual Framework.” Sustainable Cities and Society 50: 101625. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2019.101625.

- Rockefeller Foundation. 2021. “100 Resilient Cities.” Rockefeller Foundation, Accessed June 2. https://www.rockefellerfoundation.org/100-resilient-cities/.

- Rockefeller Foundation, and Arup. 2015. City Resilience Framework. Rockefeller Foundation and Arup.

- Sanchez, A. X., J. van der Heijden, and P. Osmond. 2018. “The City Politics of an Urban age: Urban Resilience Conceptualisations and Policies.” Palgrave Communications 4: 25. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-018-0074-z.

- Shaw, K. 2012. ““Reframing” Resilience: Challenges for Planning Theory and Practice.” Planning Theory & Practice 13 (2): 308–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2012.677124.

- Suárez, M., E. Gómez-Baggethun, and M. Onaindia. 2020. “Assessing Socio-Ecological Resilience in Cities.” In Routledge Handbook of Urban Resilience, edited by M. Burayidi, A. Allen, J. Twigg, and C. Wamsler, 197–216. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

- Torabi, E., A. Dedekorkut-Howes, and M. Howes. 2017. “Not Waving, Drowning: Can Local Government Policies on Climate Change Adaptation and Disaster Resilience Make a Difference?” Urban Policy and Research 35 (3): 312–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/08111146.2017.1294538.

- UN-Habitat. 2021. “Resilience.” United Nations Human Settlements Programme, Accessed February 4 2021. https://unhabitat.org/resilience.

- United Nations. 2015. Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030. Geneva, Switzerland: United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction.

- United Nations. 2016. Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on 23 December 2016: New Urban Agenda. United Nations.

- United Nations. 2018. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2018 Revision. New York: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division.

- United Nations General Assembly. 2015. Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly: Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development A/RES/70/1. New York: United Nations.

- Walker, B. H., and D. Salt. 2006. Resilience Thinking: Sustaining Ecosystems and People in a Changing World. Washington, DC: Island Press.

- Wamsler, C. 2014. Cities. Disaster Risk and Adaptation. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Watts, N., M. Amann, N. Arnell, S. Ayeb-Karlsson, J. Beagley, K. Belesova, M. Boykoff, et al. 2021. “The 2020 Report of The Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change: Responding to Converging Crises.” The Lancet 397 (10269): 129–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32290-X.

- White, I., and P. O'Hare. 2014. “From Rhetoric to Reality: Which Resilience, why Resilience, and Whose Resilience in Spatial Planning?” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 32 (5): 934–950. https://doi.org/10.1068/c12117.

- Wilkinson, C. 2012. “Social-ecological Resilience: Insights and Issues for Planning Theory.” Planning Theory 11 (2): 148–169. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095211426274.