ABSTRACT

The fact that community ownership increases the social acceptability of renewable energy projects is well established, but there is a lack of empirical evidence to explain why this is the case. This study examines whether energy justice factors (fair involvement, fair distribution of benefits and perceived impacts from wind turbines) can help explain this relationship, whether these factors are interrelated, and whether different ownership structures (community, shared or private ownership) change these associations. Using a postal survey of residents in Scotland (n = 320), the study employs a novel method, Multigroup-Structural Equation Modelling, to investigate these questions. This modelling reveals that acceptance of these projects was influenced by factors of energy justice (i.e. fair involvement, fair benefits and perceived impacts), but the influence from each factor depended on the ownership structure. Specifically, those near the community-owned project prioritised involvement, those near the privately-owned valued fair benefits, and those near the shared ownership prioritised both. By examining the relationships amongst energy justice factors, the real-life complexity of people’s responses to wind energy projects is revealed, whereby factors can have knock-on effects. Importantly, this study finds that the community and shared ownership projects fostered greater community acceptance than the privately-owned because they had more instances where fair involvement influenced other factors, which led to greater overall acceptance. Although community involvement may seem time-consuming, a more inclusive approach can prevent long-term issues caused by local opposition.

Policy Highlights

Community ownership of renewable energy projects leads to greater acceptance by local residents, as long as the projects meet their expectations.

Energy justice plays a crucial role in acceptance of onshore wind energy projects, but residents prioritise different aspects depending on ownership.

Policymakers and developers should take into account the preferences and concerns of local residents when designing renewable projects, especially in terms of fair involvement and fair distribution of benefits.

Better support for communities and developers is essential if the Scottish Government want shared ownership offered on all new projects.

1. Introduction

Nations worldwide are striving to achieve ambitious renewable energy targets to mitigate the growing urgency of climate change (IEA Citation2021). One of the many challenges this entails is ensuring local support for renewable energy projects. Many such projects have been slowed or permanently halted by local opposition, causing delays which impede the energy transition (Cohen, Reichl, and Schmidthaler Citation2014). Often suggested as a solution to local opposition is community-owned renewables, that is, projects which are owned, developed and operated by local communities. However, Baxter et al. (Citation2020) contend that the relationship and the reason for why community-owned projects garner acceptance remains “a relatively untested assumption” (3).

Of the empirical research available, most suggest that community-owned renewables garner acceptance because they involve the local community in the decision-making process and provide substantial financial benefits (Baxter et al. Citation2020). However, some studies have overlooked ownership as a factor in acceptance (e.g. Gross Citation2007; Ki et al. Citation2022), others tend to compare acceptance across extreme ends of the ownership spectrum, like community versus private projects (Walker and Baxter Citation2017a; Warren and McFadyen Citation2010), and few studies have explored how varying degrees of ownership, such as community, shared and private models, may influence local acceptance decisions (although see Hogan et al. (Citation2022)). Researchers are increasingly critical of energy justice explanations for acceptance, suggesting that: the relationships between perceptions of fair involvement and financial benefits are not independent of each other (Creamer et al. Citation2019); and that there are other important factors to consider alongside fair involvement and benefits, namely, perceived negative impacts caused by wind turbines, the level of community investment (e.g. community vs private ownership) and local context (Baxter et al. Citation2020).

Therefore, using multigroup structural equation modelling (Multigroup-SEM), this paper investigates whether justice factors, that is, fairly perceived involvement in decision-making and financial benefits, and fewer perceived negative impacts from wind turbines, indeed lead to greater acceptance. It also examines whether these factors are related to one another, and if those relationships change over different ownership projects found in Scotland, a nation often acknowledged for its community energy projects (Kumar and Aiken Citation2021). To the best of the author’s knowledge, no studies have used multigroup analysis in SEM to test whether residents near projects with different forms of ownership (community, shared, private) prioritise certain aspects of energy justice when deciding on their acceptance. By accounting for the expectations of local residents, policymakers and developers can ultimately design renewable energy projects which are more locally acceptable.

1.1. Community acceptance, community renewables and research aims

For more than three decades, researchers have looked at a variety of factors involved in shaping acceptance of renewable energy projects, revealing that it is much more complex than originally thought (see Baxter et al.'s (Citation2020) and Batel’s (Citation2020) review). Much of the research still builds on Wüstenhagen et al.'s (Citation2007) framework, which organises acceptance into three classifications: socio-political, community and market. This study concentrates on community acceptance, specifically the support of renewable projects by local residents.

Within social acceptance research, Batel (Citation2020) identifies three waves of research: normative, criticism and critical. The first “normative” wave explained public opposition through Not-In-My-Backyard-ism (NIMBYism), described as a “syndrome” where people only oppose facilities if they are built close to their homes. The second “criticism” wave focused on the deconstruction of NIMBYism as an explanation for public and community opposition by considering socio-psychological factors, for example, community acceptance literature increasingly recognises the significance of community ownership and local investment (e.g. Goedkoop and Devine-Wright Citation2016; Haggett and Aitken Citation2015; Simcock Citation2016; Warren and McFadyen Citation2010). Within this wave of the literature, researchers interested in community ownership often argue that these projects garner acceptance because it involves the two dimensions identified by Walker and Devine-Wright (Citation2008): process and outcomes (see Baxter et al. Citation2020).

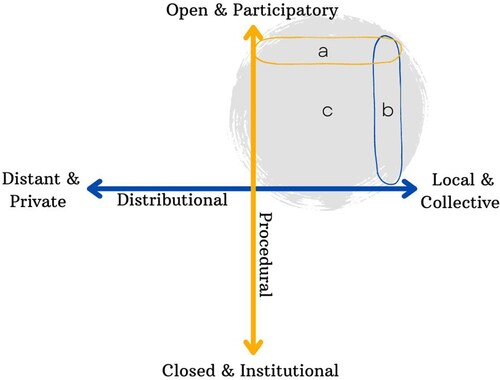

In their framework for an “ideal” community renewable project, Walker and Devine-Wright (Citation2008) define a just process as the extensive involvement of the local community in planning, development and even operation of the project (; area a) and just outcomes as how fairly the benefits are distributed (; area b). Based on this framework, projects with a high degree of community involvement and equitable benefits are expected to garner greater acceptance. The framework also recognises that some projects can still be “productive and useful” (Walker and Devine-Wright Citation2008, 499) without achieving the highest degree of involvement or fairness in benefits (, area c).

Figure 1. Conceptual dimensions of community renewable energy projects (adapted from Walker and Devine-Wright (Citation2008) to include procedural justice and distributional justice in the place of process and outcomes).

Although the original framework was not intended to describe local acceptance (Creamer et al. Citation2019), researchers continue to find it valuable and build upon it (e.g. Baxter et al. (Citation2020); Krumm, Süsser, and Blechinger (Citation2022)). Others have interrogated and criticised this framework for its oversimplification of community renewable projects. Creamer et al. (Citation2019) argue that the original conceptualisation fails to account for the relationships between the factors themselves, for example, between process and outcomes. Baxter et al. (Citation2020) propose an expanded diagram that considers additional elements such as investment scale (e.g. community or private), negative impacts caused by turbines (e.g. aesthetic impacts) and historical context of the project and places in which they are situated. Some recent studies have begun to address these gaps, such as Hogan et al. (Citation2022) who reported that communities with some ownership stake had more positive views on involvement, benefits and impacts compared to a private project. However, they did not empirically test the relationships between these factors and acceptance, if there are relationships amongst the justice factors (as suggested by Creamer et al. Citation2019), or if residents make decisions differently regarding their acceptance depending on the project’s ownership structure.

Building on this third wave of critical social acceptance research, this paper incorporates Baxter et al.’s (Citation2020) suggestions by including investment scale (community, shared and private ownership) and perceived negative impacts (perceived impacts) into the quantitative analysis of community acceptance. This paper also examines the relationships between energy justice factors, that is, between fair involvement, fair financial benefits and perceived impacts. Both criticisms of this framework seem to agree that the literature on the acceptance of wind energy is conceptually rich, but there is a tendency to uncritically accept that community ownership leads to better outcomes for the community (Creamer et al. Citation2019) and that there is little empirical evidence as to why this is the case (Baxter et al. Citation2020). Thus, using Multigroup-SEM, this research empirically tests whether fair involvement, fair financial benefits and perceived impacts are why community ownership leads to greater acceptance. These justice factors will be examined through the tenets of energy justice, known as procedural and distributional justice.

1.2. Defining energy justice concepts

The pursuit of a just and equitable energy transition for a post-carbon society has emerged as a pressing topic in both academic circles and policy domains Citation2024(Heffron ; Jenkins et al. Citation2021). As a result, the field of energy justice has rapidly expanded, encompassing a diverse range of topics, such as energy poverty (Mulder, Dalla Longa, and Straver Citation2023; Simcock et al. Citation2021), the role of activism in the transition (Lacey-Barnacle Citation2022) and acceptance of energy technologies (Roddis et al. Citation2018; Walker and Baxter Citation2017a, Citation2017b). The most widely used framework in this field is the tenets of energy justice: procedural justice, distributional justice and recognition justice (Jenkins et al. Citation2016; McCauley et al. Citation2013). This research focuses on the first two tenets as they are similar to Walker and Devine-Wright’s (Citation2008) process and outcomes.

Procedural justice pertains to the fairness of the participation of all stakeholders during the decision-making process (Jenkins et al. Citation2016). It aligns well with Arnstein’s (Citation1969) “ladder” of citizen participation as they both advocate for equity and empowerment across society. Distributional justice, on the other hand, emphasises equitable distribution of benefits and impacts, irrespective of factors such as race, gender, or social status (Jenkins Citation2019). Rather than adopting a “whole systems” strategy (Jenkins et al. Citation2016), this study focuses on these concepts at a local level to achieve an in-depth analysis (Agterbosch, Meertens, and Vermeulen Citation2009). At a local level, material benefits are typically provided through financial payments.

In this research, perceived impacts refer to local impacts of wind energy and is related to distributional justice. To investigate perceived impacts, this paper uses Roddis et al.'s (Citation2018) framework which groups material impacts into four categories: aesthetics, environmental, economic and project details. Aesthetics is among the few scientifically validated measures of renewable support (Warren and Birnie Citation2009), but all framework categories, including environmental impacts, such as on birds and bats (Leiren et al. Citation2020), and economic impacts, including on property values (Mills, Bessette, and Smith Citation2019) and tourism (Leiren et al. Citation2020; Ólafsdóttir and Sæþórsdóttir Citation2019), influence acceptance. Project details like turbine distance and number can affect impact severity and hence acceptance (Leiren et al. Citation2020). This study uses turbine distance as a control variable to assess their influence.

1.3. Rationale for structural equation modelling (SEM)

This study employs SEM, a technique for testing multivariate causal relationships (Fan et al. Citation2016). SEM was used, instead of regression modelling, because it allows for more complex path models with direct and indirect effects to be measured at the same time, mirroring the fact that variables coexist in the real world (Chang et al. Citation2020). The connection between community ownership and acceptance has been examined both qualitatively (Simcock Citation2016; Walsh Citation2016) and quantitatively (Hogan et al. Citation2022; Musall and Kuik Citation2011), with some using mixed-methods (Walker and Baxter Citation2017a, Citation2017b; Warren and McFadyen Citation2010). To the best of the author’s knowledge, no studies have used multigroup analysis in SEM to test whether residents near projects with different forms of ownership (community, shared, private) prioritise certain aspects of energy justice when deciding on their acceptance.

Nevertheless, SEM has been applied to acceptance literature to understand acceptance of the energy transition (Gölz and Wedderhoff Citation2018), hypothetical renewable projects (Liu et al. Citation2020) and offshore wind energy attitudes (Ferguson et al. Citation2021). Bidwell (Citation2013) similarly aimed to understand attitudes towards onshore wind energy, in which their SEM revealed that support for a commercial wind energy development depended mostly on the economic benefits of the project. However, this was not compared across projects with different ownership forms. Mueller (Citation2020) investigated relationships between variables (i.e. procedural fairness, trust in actors, perceived benefits and risk expectations) to understand attitudes towards power grid expansion projects, but did not test across ownership, whether perceived fairness was associated with perceived benefits (as suggested by Creamer et al. Citation2019), or the relationship between perceived benefits and risk expectations.

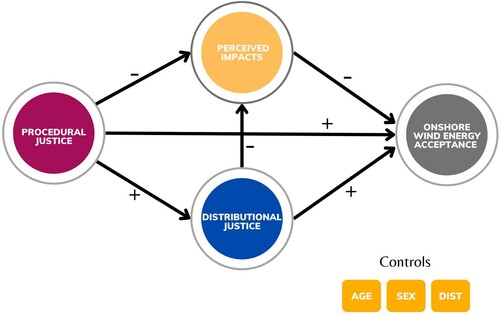

Therefore, by using Multigroup-SEM, this research addresses two main gaps identified by Bal et al. (Citation2023) in the acceptance and fairness perception literature regarding energy transitions. First, research has tended to apply one dimension of justice when examining acceptance (Firestone et al. Citation2012; Simcock Citation2014) or treats justice as a universal factor (Bidwell Citation2013). Of those that study them together, there has also been little acknowledgement of how these factors relate to one another (although see Mueller (Citation2020)). Second, Bal et al. (Citation2023) report that there has been limited exploration of the reasoning behind people’s fairness perceptions (although see exceptions of Rasch and Köhne (Citation2017) and Velasco-Herrejon and Bauwens (Citation2020)). Therefore, this study uses Multigroup-SEM to address these literature gaps by examining relationships between procedural justice, distributional justice, perceived impacts and whether the reasoning behind residents’ justice perceptions can be explained by the ownership structure of the project (i.e. community, shared and private). The following section outlines literature supporting hypothesised relationships for the Multigroup-SEM (refer to and for hypothesised relationships).

Figure 2. Hypothesised empirical relationships among energy justice factors, acceptance and controls.

Table 1. Hypothesised direct, moderation and indirect relationships.

1.3.1. Direct relationships of energy justice on acceptance

Procedural and distributional justice have been studied in different contexts, relating a fair decision-making process to acceptance (Gross Citation2007; Ki et al. Citation2022; Liu et al. Citation2020; Walker and Baxter Citation2017a; Wolsink Citation2007) and a just distribution of benefits to acceptance (Gross Citation2007; Jepson, Brannstrom, and Persons Citation2012; Walker and Baxter Citation2017b). Perceived impacts have also been found to influence acceptance, with lower perceived impacts generally leading to greater acceptance (Leiren et al. Citation2020; Mills, Bessette, and Smith Citation2019; Ólafsdóttir and Sæþórsdóttir Citation2019; Warren and Birnie Citation2009). However, Baxter et al. (Citation2020) argue that relying solely on either procedural or distributional justice is inadequate to ensure community acceptance. Instead, these factors should work together in a mutually reinforcing and locally focused manner to enhance community acceptance (Hogan et al. Citation2022). Based on the research above, it is hypothesised that these energy justice factors (procedural justice, distributional justice and perceived impacts) will be related to acceptance (see , H1–H3).

1.3.2. Relationships between energy justice factors and indirect effects on acceptance (mediation)

Creamer et al. (Citation2019) criticise Walker and Devine-Wright's (Citation2008) conceptualisation because it assumes that involvement in the decision-making (process) and fairness of the benefits (outcomes) are independent of each other. Yet, some may see being involved in the decision-making process as a benefit in itself (Creamer et al. Citation2019). Similarly, benefits may be perceived as bribery if the communities’ expectations are not first taken into account (as seen in van Bommel and Höffken Citation2021), further suggesting that procedural and distributional justice are not independent variables. However, as there is no guarantee that these relationships do not change over time, which is an assumption of a feedback loop in SEM (Fan et al. Citation2016), it is only possible to measure one direction. As communities are typically involved in the decision-making process before economic benefits begin (e.g. public consultations, investments), procedural justice is placed at the beginning of the SEM and is hypothesised that procedural justice is related to distributional justice (, H4).

Previous research has shown that procedural and distributional justice have also seen to be related to perceived impacts. For example, those who perceived the process to be unfair regarded the impacts as more severe than those who perceived a fair process (Mills, Bessette, and Smith Citation2019). Similarly, Hogan et al. (Citation2022) report that communities which perceived fairer involvement and fairer benefits tended to perceive lesser impacts, and vice-versa, suggesting that there is a positive relationship between process, outcomes and perceived impacts (, H5–H6). Due to the relationships discussed in the above literature, there are also three hypothesised indirect (mediation) effects (, H8–H10).

1.3.4. Does ownership change these relationships? (moderation)

Several articles have suggested that ownership influences acceptance (Bauwens and Devine-Wright Citation2018; Gross Citation2007; Musall and Kuik Citation2011; Walker and Baxter Citation2017a; Walsh Citation2016; Warren and McFadyen Citation2010). As a sense of connection with the communities and the development is likely to be shaped by a psychological sense of ownership stemming from pride or a sense of achievement, and not just by financial gain (Walsh Citation2016), it is hypothesised that the ownership model (i.e. community, shared, or private ownership) moderates the relationships between the energy justice factors and acceptance (i.e. strengthens or weakens the relationships, depending on the project, , H7). In other words, residents may make decisions regarding their acceptance and justice perceptions differently depending on the ownership structure of the project, responding to the call of Bal et al. (Citation2023).

2. Scottish context and policy

Among the devolved governments of the UK, Scotland stands out for its growth in renewable energy sources, particularly onshore wind (Cowell Citation2017). Having gained a devolved parliament in 1999, the Scottish Government now has responsibility for decision making on certain key issues, but with varying degrees of control (Wood Citation2017). In practice, the Scottish Government has authority over renewable energy initiatives and can decide what types of power generation take place on Scotland’s territory (Stephens and Robinson Citation2021). However, the Scottish Government does not have control over energy policy, market incentives, or the national grid (see Cowell (Citation2017) for a comparison of energy-related powers across UK devolved nations). Nevertheless, the Scottish Government has used its political power to push for renewable energy like onshore wind. As a result, Scotland had about 9 gigawatts (GW) of onshore wind in operation in 2022, contrasting with only 1.26 GW of installed capacity in Wales in the same year (Welsh Government Citation2022), and now aims to increase installed capacity to 20 GW by 2030 (Scottish Government Citation2022). Scotland’s relative success in onshore wind developments has been associated with the Scottish Government's leadership and vision on renewable energy, sometimes associated with Scotland’s independence movement (Gibbs Citation2021), and their ability to create effective policy communities, aligning key actors in industry, agencies and civil society towards their pro-renewable agenda (Cowell Citation2017).

Scotland has also gained recognition for being a prominent leader in community-driven renewable energy projects, especially in the Highlands and Islands, associated with the community empowerment movement and land reform efforts that facilitated local adoption (Slee and Harnmeijer Citation2017). Acknowledging the range of local benefits from community-ownership including increased resiliency (Haggett and Aitken Citation2015), capacity building (Wirth Citation2014); awareness of green energy (Rogers et al. Citation2012), low-carbon development (Walker et al. Citation2007; Warren and McFadyen Citation2010); and improving local environmental health (Hoffman and High-Pippert Citation2010), the Scottish Government has set targets for “community and locally-owned” renewable energy capacity. Having met their target of 500 MW of “community and locally-owned” renewable energy capacity in 2015, five years early, a second target of 2 GW was set to meet by 2030, of which 45% was met by 2021 (Energy Saving Trust Citation2021). Alongside these targets, the Scottish Government has also provided guidance on expectations for developers and communities in the Scottish Good Practice Principles for Onshore Renewable Development (Scottish Government Citation2019a, Citation2019b). These documents offer guidance on a range of projects, splitting ownership into two categories: private ownership and community and locally owned.

Private ownership projects are owned by a developer but should provide monetary benefits of £5000 per MW installed capacity to nearby communities for the lifetime of the windfarm, known as community benefit payments. These payments are not a legal obligation but are strongly encouraged by the Scottish Government.

“Community and locally-owned” projects refer to those owned by a community group, farm, estate, local authority, or any other local business (Energy Saving Trust Citation2021). However, some researchers suggest that a project can only be considered community-owned if it is not driven by private profits and is owned and managed by the local community, but can operate in collaboration with other organisations (Slee Citation2020). Thus, this paper separates “community and locally-owned” into two categories:

Community ownership is when the community fully owns the project and thus receives all the financial benefits while also owning the associated risks involved in building and sustaining the project.

Shared ownership is an organisational structure wherein the community becomes a financial stakeholder throughout the lifespan of the renewable development (Scottish Government Citation2019b).

Despite the progress in policy and support of community ownership by the Scottish Government, only 4% of Scotland’s onshore renewable generation is considered community renewable energy (Slee and Harnmeijer Citation2017). Community-owned projects often face several challenges such as a lack of financial capital, threat of financial losses, and/or a lack of requisite knowledge, skills, experience, or time (Haggett and Aitken Citation2015). Additionally, the small-scale nature of community projects has limited their ability to contribute to the growth needed to meet national renewable production targets (Warren and McFadyen Citation2010). To address these concerns, interest in shared ownership has grown due to its potential to facilitate larger-scale projects with community investment (Philpott and Windemer Citation2022) and democratic practices (Bauwens and Devine-Wright Citation2018; Hogan et al. Citation2022). Reflecting these trends, the Scottish Government has updated their policy, stating a new goal to have shared ownership offered as a standard on all new renewable projects, including repowering and extensions to existing projects (see section 4.2.4 of the Scottish Government’s (Citation2022) onshore wind policy statement). To contribute to better understanding the effectiveness of this policy shift, this research will contribute to the limited research which compares acceptance and justice perceptions across a gradient of ownership models, that is, community, shared and private ownership.

3. Methods

3.1. Study sites

The selected communities are located near an onshore wind energy project and were chosen according to the following four criteria:

Each project provides some benefits for the local communities, given the importance of benefits in influencing acceptance (Gross Citation2007; Jepson, Brannstrom, and Persons Citation2012; Walker and Baxter Citation2017b).

One site was studied for each category of ownership (community, shared and private) to investigate whether the relationships change depending on the scheme, for example, the privately-owned project must adhere to the Scottish Government's guidance of £5000 per MW per annum, providing insight into how the guidance is working in a real project.

Each project has an installed capacity below 30 MW and fewer than 15 turbines as turbine number and size can influence acceptance (Leiren et al. Citation2020).

Each project is located in the Highlands and Islands of Scotland to ensure that there were similar demographic structures such that there are about 51% females and about 50% aged between 44 and 69 (National Records of Scotland Citation2011).

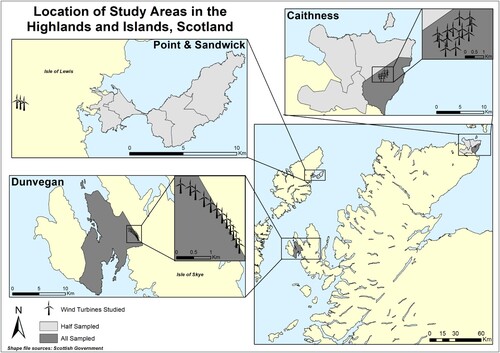

This research uses case study perspectives because they offer a more nuanced understanding of outcomes in community projects, which are not well-understood (see Baxter et al. (Citation2020) and Berka and Creamer (Citation2018)). Similar to Leer Jørgensen, Anker, and Lassen (Citation2020), who examined benefit models and acceptance in three Danish projects, using case studies instead of a representational sample also allows for a deeper understanding of why certain relationships may exist in particular projects, but not in others. Details about the study area, including project size and financial benefits, are provided in .

Table 2. Study area details.

3.2. Data collection

In total, data from 320 residents were collected using Vaske's (Citation2019) 4-contact mail-out method, where residents received mail-outs in the following order: (1) postcard notification; (2) paper questionnaire; (3) reminder postcard; and (4) an additional questionnaire packet. To ensure informed consent under the approved ethical review, the residents were provided an information sheet alongside the questionnaire. The sample population were inhabitants within community councils (18 or older) that own or yielded financial payments associated with the wind turbines. The sample was drawn from Dunvegan and Caithness within a 10 km radius and Point and Sandwick within a 15 km radius (see ). A combination of cluster and systematic sampling was employed, with every house within the dark grey areas of and every second household in the lighter grey areas sampled. Data collection took place February–April, 2021.

Figure 3. Location of study areas and wind farms in Scotland, which is situated in the north of the United Kingdom. A scale bar of 10 km is shown at the bottom of each study area to compare distance to the wind turbines.

Response rates were as follows: 33% in Caithness (n = 126 valid questionnaires), 51% in Dunvegan (n = 93 valid questionnaires) and 33% in Point and Sandwick (n = 159 valid questionnaires). Questionnaires were deleted if they had 15% of more missing values (a total of 9: Caithness n = 4; Dunvegan n = 3; Point and Sandwick n = 2). As the model required participants to answer energy justice statements, just those who were residing in the community at the time of the windfarms’ construction were considered for analysis: Caithness (n = 112; 89% of sample), Dunvegan (n = 71; 76% of sample), Point and Sandwick (n = 136; 86% of sample). Lastly, 122 comments were written on the questionnaires (Caithness n = 50; Dunvegan n = 30; Point and Sandwick n = 42), then coded systematically to identify patterns that could contribute additional insight to the discussion.

3.3. Variables/latent concepts

All variables were asked on a scale from 1 to 5 and recoded in SPSS from −2 to +2 to ease the interpretation of the analysis (Vaske Citation2019). For each statement, residents were asked to indicate to what extent they agreed or disagreed on a 5-point Likert scale from “Strongly Disagree” (−2) to “Strongly Agree” (+2), see . There were 60 statements on the survey, in which 11 were relevant to this study. All indices were derived from previous research (Roddis et al. Citation2018; Walker and Baxter Citation2017a, Citation2017b; Walker et al. Citation2015).

Procedural justice consisted of three variables that measured their opportunity to be involved in the wind development (see ). Distributional justice was measured with two items that measured perceived fairness of benefits from the development. Perceived impacts was measured by four items that measured perceived impacts of wind turbines with regard to aesthetic deterioration, consequences for birds and bats, reductions of property/house values, and damage to tourism (based on Roddis et al. (Citation2018)). Finally, acceptance was measured by two items: one measured the residents’ acceptance, whilst the other measured their approval of how the wind farm was planned in the area.

3.4. Data analysis

SPSS 28 and AMOS 26 were used for data analysis. Missing data were checked for random distribution and then replaced with the mean for that variable (Vaske Citation2019). Of the observed variables included in this study, 2% or less had missing data. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) and Cronbach's alpha were used in SPSS 28 to examine construct validity and reliability of the three key constructs: procedural justice, distributional justice and perceived impacts (Vaske Citation2019). Some variables were excluded or combined with similar constructs due to cross-loading.

A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was then conducted in AMOS 26 to assess goodness of fit and reliability of the four constructs (including local wind acceptance). Several goodness-of-fit indices were used such as Comparative Fit Index (CFI; an acceptable level > 0.90; Salisbury et al. Citation2002), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA; values less than 0.08 are acceptable; Byrne Citation2013) and chi-square divided by the degrees of freedom (χ2/df; value is greater than one and less than five; Salisbury et al. Citation2002).

The sample was then divided into community, shared and private ownership groups to allow for the comparative analysis and test for measurement invariance using CFA. Measurement invariance assesses whether the latent constructs in the model (i.e. procedural, distributional, perceived impacts and acceptance) are comparable across the two groups (Ponnapureddy et al. Citation2020). Configural validity was assessed through the model fit when both groups were unconstrained.

Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) was then used in AMOS 26 to assess predictive validity, moderation role of ownership, and mediation role of distributional justice and perceived impacts. To test the differences across ownership models for each structural relationship, a chi-square difference test was preformed where the two models were freely estimated across all paths except for one path constraint at a time was set to be equal across groups. Bootstrapping analysis was used to test the mediation effects for the model of best fit because it has been found to be one of the most powerful tools to detect mediation (Hayes Citation2013). Using a sampling with replacements strategy, bootstrapping makes a larger sample from the original dataset (2000 for this study). In order to obtain a significance level for each of the indirect effects, a confidence interval (95% in this study) was constructed where for an indirect effect to be considered significant, the interval cannot include zero.

3.5. Limitations

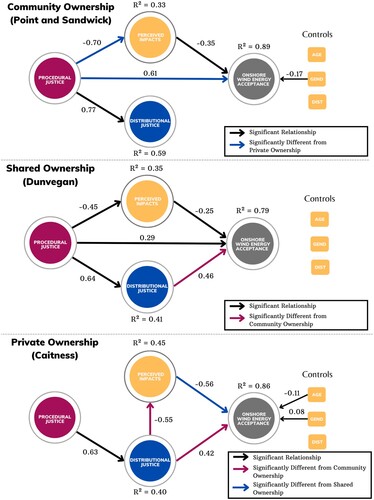

Due to the rural setting, sample sizes were small when split into three areas for multi-group analysis. Dunvegan, which has a co-operative structure, has a sample size below the usual threshold for SEM (usually around 90–100), which may decrease its explanatory power. However, Dunvegan's response rate is high (over 50%) and the model remains an excellent fit (see R2 value on ) even when split from the community- and privately-owned projects. As this is one of the first studies to use Multigroup-SEM to compare across these ownership projects, the results from the shared ownership act as a first understanding of how this structure compares to more familiar ones. Shared ownership sits between community ownership and private ownership on the ownership gradient, which is clearly reflected in the results and worth further investigation.

Figure 4. The significant relationships between the constructs: procedural justice, distributional justice and perceived impacts of wind turbines, and onshore wind energy acceptance. Only statistically significant lines (p < .05) are shown. Thus, if not significant, there is no line. Relationships represented by a red or blue line represent a significantly stronger relationship from another group when compared in the multi-group analysis.

4. Results

4.1. Demographics

Demographics were similar across the communities (). Notably, respondents in Point and Sandwick lived farther from the wind turbines, at a distance of 6 miles or more, compared to those in the other two communities who lived within 2–5 miles or closer. Point and Sandwick was selected as a sample because they own the wind turbines on common land. Regarding acceptance of their local wind farm, community and shared ownership tended to result in higher acceptance rates than private ownership (Means, ). It is noteworthy that the privately-owned project showed a split between agreement and disagreement on project support (36 and 46%, respectively), while the community-owned project had a majority in agreement.

Table 3. Demographics of survey respondents.

Table 4. Confirmatory factor analyses and Cronbach's alpha for Procedural Justice, Distributional Justice, Perceived Impacts and Acceptance.

4.2. Confirmatory factor analysis, reliability, validity and configural invariance

The CFA for all items showed an excellent fit (χ2 = 53.5; df = 38; χ2/df = 1.4; CFI = 0.99; RMSEA = 0.036). Standardised factor loadings for the items ranged from 0.75 to 0.95 and were all significant at the p < 0.001 level. Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficients for the four concepts were considered excellent (i.e. above 0.8). Discriminant validity (i.e. all a square root of AVE greater than inter-construct correlations and all AVEs were greater than MSVs), convergent validity (i.e. all AVEs were above 0.5) and factor reliability (i.e. all CRs were greater than 0.7) were observed (Hair et al. Citation2010). CFA was also computed across groups of ownership to establish configural invariance (Community and Private, x2 = 98.6, df = 76, p < 0.05, CFI = 0.99 and RMSEA = 0.031; Community and Shared x2 = 102.8, df = 76, p < 0.05, CFI = 0.98 and RMSEA = 0.041; Shared and Private, x2 = 87.9, df = 76, p < 0.05, CFI = 0.99 and RMSEA = 0.029).

4.3. Model fit across ownership projects

The hypothesised model assessed the interrelationships between the process, outcomes, perceived impacts and acceptance across different ownership groups: community, shared and private ownership. The constructs explained 89% of the variance for the community-owned, 79% for the shared ownership and 86% for private ownership project for support for their local wind energy project. Overall, the estimation result showed an excellent model fit (community and private, x2 = 190.5; df = 130; CFI = 0.97; and RMSEA = 0.038; shared and private, x2 = 156.11; df = 130; CFI = 0.98; and RMSEA = 0.033; community and shared, x2 = 172.9; df = 130; CFI = 0.97; and RMSEA = 0.040). The results of the AMOS 26 SEM are shown in .

4.4. Direct effects

The Multigroup-SEM ( and ) found that for the community-owned project, the greatest direct effect on acceptance was from procedural justice (see , H1), followed by perceived impacts (H3), explaining 89% of its variance. Distributional justice was not found to be related to acceptance (rejecting H2). Distributional justice was positively associated with procedural justice (H4) which explained 59% of its variance. Perceived impacts was negatively associated with procedural justice (H5), explaining 33% of its variance. Perceived impacts were not associated with distributional justice (rejecting H6). For the controls, only age and gender were associated with acceptance.

Table 5. Direct, indirect, and total effects for community, shared, and privately-owned Structural Equation Models.

For shared ownership, the greatest direct effect on acceptance was from distributional justice (H2), followed by procedural justice (H1) and then perceived impacts (H3). Distributional justice was positively associated with procedural justice (H4) which explained 41% of its variance. Perceived impacts were negatively associated with procedural justice (H5) which explained 35% of its variance. Perceived impacts were not associated with distributional justice (rejecting H6). None of the controls were related to acceptance.

For private ownership, the greatest direct effect on acceptance was from perceived impacts (H3), followed by distributional justice (H2), explaining 86% of its variance. Procedural justice was not found to be associated directly with acceptance (rejecting H1). Distributional justice was positively associated with procedural justice (H4), explaining 40% of its variance. Perceived impacts were negatively associated with distributional justice (H6), explaining 45% of its variance. Perceived impacts were not associated with procedural justice (rejecting H5). None of the controls were significant.

4.5. Ownership as a moderator

When the full models were compared, the direct effects in the community and privately owned models were found to be significantly different (p = 0.000; supporting H7), but no difference was found between the shared ownership project and either the community-owned (p = 0.11) or the privately-owned project (p = 0.08). However, there were some differences found between all models when specific structural relationships were examined.

As seen in , the direct effect of procedural justice on acceptance and procedural justice on perceived impacts was stronger for the community-owned project than for privately-owned (p = 0.001). Alternatively, the relationship between distributional justice and acceptance was stronger in both the privately-owned project and the shared ownership project than the community-owned project (p = 0.02; p = 0.02). The relationship between distributional justice and perceived impacts was stronger for the privately-owned project than the community owned project (p = 0.000). Finally, the association between perceived impacts and acceptance was less strong for shared ownership than the privately-owned project (p = 0.005). See Appendix S1 for a table of all significance levels.

4.6. Indirect effects

The significance levels for the indirect effects can be found in . For the community-owned project, the relationship between procedural justice and acceptance was partially mediated only by perceived impacts, but not by distributional justice (partially supporting H8). For shared ownership, both distributional justice and perceived impacts partially mediated the relationship between procedural justice and acceptance (supporting H8). For the privately-owned project, procedural justice only had an indirect effect on acceptance through distributional justice, but not through perceived impacts (partially supporting H8). Thus, this relationship is fully mediated through distributional justice as the privately-owned project also had no direct relationship between procedural justice and acceptance.

H9, where the positive relationship between distributional justice and acceptance is predicted to be partially mediated through perceived impacts, was only found to be supported in the privately-owned project and rejected for community and shared ownership. The final hypothesis (H10), where the negative relationship between procedural justice and perceived impacts would be partially mediated through distributional justice, was supported in both the shared and privately-owned projects, but not in the community-owned.

While not directly hypothesised, for the privately-owned development, it was found that the positive relationship between procedural justice and acceptance was mediated first by distributional justice and then perceived impacts for privately-owned. This was not found for the community or shared ownership models as there are no associations between distributional justice and perceived impacts.

4.7. Total effects

By combining the direct and indirect effects, the findings in show that procedural justice has the strongest total effect on acceptance of local onshore wind energy projects for community-owned and shared ownership. By contrast, for privately-owned, distributional justice has the strongest total effect on support followed by a strong effect from procedural justice on acceptance. The total effects of procedural justice on perceived impacts were also strong for all communities.

5. Discussion

The aim of this research is to empirically test whether common characteristics of community ownership, such as justice factors (i.e. perceptions of the fairness of the involvement in the decision-making and financial benefits, and perceived impacts) help explain acceptance. It also examines whether the model of ownership, that is, community, shared, private, change which factors of justice have an influence on community acceptance, responding to the calls of previous research (Baxter et al. Citation2020; Creamer et al. Citation2019; Hogan et al. Citation2022). Novel to this study, a Multigroup-SEM found that acceptance of these projects was influenced by factors of energy justice (i.e. fair involvement, fair benefits and perceived impacts), but the influence from each factor depended on the ownership structure (Community r2 = 0.89; Shared r2 = 0.79; Private r2 = 0.86). The discussion is followed by the conclusions where the policy implications are highlighted.

5.1. Prioritisation of energy justice factors by ownership structure

Unexpectedly, the results across the models contradict the common interpretation of Walker and Devine-Wright’s (Citation2008) conceptualisation () and Baxter et al.’s (Citation2020) argument that it is not likely sufficient to have either procedural or distributional justice on its own to influence acceptance. In the community-owned model acceptance was not associated with how fair the benefits were, not even indirectly (). Even though the benefits were high, about £900,000 per year, and the benefits seemed to meet their expectations (see Means, ), it was not valued in the same way as being involved in the project. Further contradiction of Baxter et al.’s (Citation2020) argument is supported in the findings of the privately-owned project, where even though residents felt that they were not as fairly involved as the community-owned (see Means, ), this did not lead to greater opposition. Instead, emphasis was placed on perceived impacts and how fair the benefits were, and as both were perceived poorly by the residents, it led to greater opposition. Therefore, in two cases, acceptance was determined by either the fairness of being involved in the process or the benefits, but not both ().

It should be noted that while fair benefits were not associated with acceptance of the community-owned project, it should not diminish its importance. Some community members stressed the necessity of fair benefits, declaring in the comments section that “community-owned wind farms are the way forward … fairer and more lucrative dividends to support the local community and charities” (Point and Sandwick Resident 1). The relationship's absence may stem from residents feeling secure in the community-owned project, especially if they are more fairly involved in how the benefits are used. In contrast, residents near the privately-owned project may not anticipate involvement in decision-making as the developer usually bears that responsibility. These findings do not prioritise procedural justice over distributional justice. Instead, they imply that residents consider different factors, possibly linked to ownership form, as further evidenced by the shared ownership model.

Only the shared ownership project had a direct influence from all three factors of energy justice, fair involvement, fair benefits and perceived impacts, leading to higher levels of acceptance. This supports Baxter et al.'s (Citation2020) observation that co-operative structures are where process and outcomes work most closely together. The structure of co-operatives, where residents form a membership and directly receive benefits, may facilitate a close alignment between involvement and benefits, which could explain why they are more successful in achieving acceptance than a privately-owned project.

While studies have suggested similarities between community and shared ownership projects (Bauwens and Devine-Wright Citation2018; Baxter et al. Citation2020; Hogan et al. Citation2022), these findings denote differences in how residents determine their acceptance. One main difference was that the shared ownership model valued the fairness of the benefits, which was not even indirectly related to the community-owned project. Rather, fair benefits were similarly important for the privately-owned project. Although the shared ownership project shares many “community features” with community-owned projects (i.e. aspects of the project that engage the community more, Bauwens and Devine-Wright (Citation2018), p. 613), the project is still technically privately-owned with investment from the community where most of the profits from the development go elsewhere, that is, outside of the local community. Additionally, residents who invested in the shared ownership project may have heightened expectations for personal financial returns. These results highlight the complex and nuanced nature of public acceptance, whereby ownership structure may play a role in how residents prioritise which factors of justice are important, adding to the limited research addressing this topic (Bal et al. Citation2023).

The only consistency found for the direct associations with acceptance across all projects was from perceived impacts, regardless of whether residents perceived the impacts as high or low. Fewer perceived impacts were reported for community and shared ownership projects compared to the privately-owned development (see Means, ), resulting in increased acceptance (Leiren et al. Citation2020; Mills, Bessette, and Smith Citation2019; Ólafsdóttir and Sæþórsdóttir Citation2019; Warren and Birnie Citation2009). Conversely, the privately-owned project had an associated decrease in acceptance. Overall, mitigating concerns regarding wind turbine impacts, regardless of ownership structure, will likely have a positive impact on residents’ attitudes towards wind projects. Implementing community and shared ownership structures, given their lower perceived impacts, may help mitigate concerns and increase acceptance of renewable energy projects.

These findings also address why community-owned projects are more socially acceptable (Baxter et al. Citation2020; Creamer et al. Citation2019) – that procedural justice plays an important role, echoing previous research (Simcock Citation2014; Toke, Breukers, and Wolsink Citation2008; Walker et al. Citation2010). This was somewhat foreseeable because it is well-established that community projects involve local residents more than privately-owned (Warren and McFadyen Citation2010). Notably, this paper highlights that despite similarities between community and shared ownership projects (Hogan et al. Citation2022), residents prioritised different aspects of energy justice. Specifically, those near the community-owned project expected involvement, those near the privately-owned expected fair benefits, and those near the shared ownership expected both. By comparing acceptance across three forms of ownership, it is clear that residents consider what different projects may mean for their community, determining what they prioritise in terms of their acceptance.

5.2. Connections amongst energy justice factors

The results indicate that energy justice factors (fair involvement, fair benefits and perceived impacts) are related to each other, but their influence varies across ownership. These results suggest that residents may consider trade-offs among these factors, compensating for one if it falls short of their expectations with another, for instance, in the privately-owned project, fair benefits only related to perceived impacts. As residents generally felt less involved in decision-making, benefits may have served as compensation for their perceived impacts. As a common concern when providing financial benefits to impacted communities is that they may be seen as bribery (Walker and Baxter Citation2017b), these results may describe a situation where this is occurring – i.e. when residents felt they were less involved. Thus, it is crucial to understand community expectations from the outset of the project to avoid such perceptions.

Working with communities to understand and meet their expectations may not only reduce the perception of benefits as bribery but also has other effects. Fair involvement was related to how residents perceive the fairness of benefits, supporting Creamer et al.'s (Citation2019) recommendation. Although residents with shared ownership felt that the involvement and benefits were more equitable than those with private ownership, they still expressed similar ideas for improving benefits in the comments section. For instance, they questioned why they didn't receive a discount on energy bills for having wind energy near their homes, a finding similar to that of Walker and Baxter's (Citation2017b) study in Canada. Due to these similarities, it's important to consider that the co-operative structure may exclude those who did not invest, which could impact the fairness of benefits. To create fair benefits for the local community, it is crucial to incorporate their expectations (van Bommel and Höffken Citation2021) and be flexible in how the benefits are utilised.

The total influence that fair involvement had on acceptance (directly and indirectly through other factors of energy justice) shows that fair involvement played an important role in all projects, while fair benefits only played a role in the acceptance of the shared and private ownership projects. This reveals that a major difference between these projects with a form of ownership (community and shared) and the privately-owned is that residents near the community or shared ownership projects had more instances where fair involvement influenced other factors, which led to greater overall acceptance (see total effects, ). However, fairness of involvement was still associated with acceptance in the privately-owned project, albeit indirectly through how fair the benefits were perceived. Crucially, examining the relationships amongst energy justice factors reveals the real-life complexity of people’s responses to wind energy projects, whereby factors can have knock-on effects. Regardless of the degree of ownership, it is always important to start by involving residents, as it may help compensate if other factors do not quite meet expectations.

Overall, most of the hypotheses in this study were only partially accepted (, Hypotheses 1–2, 5–6, 8–10), whereby the influence or strength of the relationship between the energy justice factors and acceptance depended on the ownership model, supporting hypothesis seven. The only relationships found consistently across projects were the influence of (a) perceived impacts on acceptance (H3) and (b) procedural justice on distributional justice (H4). Given that greater procedural justice led to lower perceived impacts in the community and shared ownership projects, fair involvement in decision-making may help mitigate concerns, which in turn increase acceptance of onshore wind projects. Finally, as the total effects highlighted, procedural justice played a key role across all projects by influencing other factors that led to greater acceptance. This finding also supports Creamer et al.’s (Citation2019) suggestion, that fair involvement in decisions and fair benefits are related.

6. Conclusion

Community acceptance of onshore energy projects is influenced by perceptions of justice, but the influence from each energy justice factor depended on the ownership structure. Specifically, those near the community-owned project expected involvement, those near the privately-owned expected fair benefits, and those near the shared ownership expected both. Importantly, fair involvement in the decision-making process (procedural justice) is found to be the most influential factor for onshore wind acceptance, irrespective of the ownership model. These findings emphasise the importance of considering contextual influences, such as ownership structure, when examining links between energy justice and community acceptance.

Noteworthy is that the financial benefits from the shared ownership project alone was not enough for the project to achieve high acceptance, the developer also had to put in significant effort to engage the community. Renantis, who developed the project, and the leaders of the community co-operative spent significant time involving the wider community beyond the initial investment stage, for example, they organised a turbine naming competition, as seen in previous studies (Warren and McFadyen Citation2010). Undertaking shared ownership efforts still require significant time, resources and financial risks from both the developer and the communities (Local Energy Scotland Citation2023). Therefore, better support is essential if the Scottish Government aims to mandate shared ownership (Scottish Government Citation2022).

To increase the uptake of shared ownership, a multifaceted approach is needed that includes building trust between developers and communities, providing partnership mechanisms and creating supportive policies. As Goedkoop and Devine-Wright (Citation2016) found, fostering trust is key but often lacking between developers and communities within the UK. Identifying potential partnerships early on in the development process can help build relationships between developers and communities, especially within a supportive policy context. Policy changes like requiring follow-ups to ensure that shared ownership is not only offered but also implemented after planning permission is obtained ensures that communities are provided the opportunity. Financial benefits should also be flexible based on community preferences to ensure they are not seen as bribery. Yet, policies alone are insufficient without parallel efforts to build mutual understanding and trust. More research is needed to understand how developers and communities can best work together to implement shared ownership models successfully.

This research is based in a limited geographic region of the Highlands and Islands, Scotland. As a devolved nation, Scotland’s energy-related decision-making is constrained, but the Scottish Government has been pushing to support renewables in ways they can, such as through planning and consent (Cowell Citation2017). Given this localised context, further comparative research across diverse settings is essential to determine the transferability of these findings. Future research should address whether residents weigh energy justice factors similarly across places where they have full control over energy decisions and incentives, community-ownership projects are less prominent, there are high concerns for local employment, or where there has been less government support for onshore wind (e.g. in England where there has been a de facto ban on onshore wind since 2015, although there has been small movements in planning, see Ranki Citation2024). Additionally, future research should examine other potential contributors to justice perceptions beyond project ownership, such as locally-relevant priorities (as seen in Velasco-Herrejon and Bauwens Citation2020).

This research provides novel evidence that the influence of certain energy justice factors depend on project context. The complex relationships reported here move beyond existing acceptance frameworks (Baxter et al. Citation2020; Walker and Devine-Wright Citation2008) by underscoring the need to consider contextual factors when examining links between energy justice and community acceptance. As nations worldwide seek to expand renewable energy capacity amid the climate crisis, community and shared ownership models may support more just and inclusive energy transitions, but only with tailored approaches addressing locally specific justice concerns and expectations.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (23.3 KB)Acknowledgements

I gratefully acknowledge the respondents from the areas of Dunvegan, Caithness, and Point and Sandwick for their time in filling out the surveys. I would also like to acknowledge my PhD supervisors Dr. Charles R. Warren, Dr. Michael Simpson and Dr. Darren McCauley who provided feedback on previous drafts of this paper and to Dr. Jerry Vaske for teaching me Structural Equation Modelling and checking my models.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that has been used is confidential.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Agterbosch, S., R. M. Meertens, and W. J. V. Vermeulen. 2009. “The Relative Importance of Social and Institutional Conditions in the Planning of Wind Power Projects.” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 13 (2): 393–405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2007.10.010.

- Arnstein, S. R. 1969. “A Ladder of Citizen Participation.” Journal of the American Institute of Planners 35 (4): 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366908977225.

- Bal, M., M. Stok, G. Bombaerts, N. Huijts, P. Schneider, A. Spahn, and V. Buskens. 2023. “A Fairway to Fairness: Toward a Richer Conceptualization of Fairness Perceptions for Just Energy Transition.” Energy Research & Social Science 103:103213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2023.103213.

- Batel, S. 2020. “Research on the Social Acceptance of Renewable Energy Technologies: Past, Present and Future.” Energy Research & Social Science 68:101544. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2020.101544.

- Bauwens, T., and P. Devine-Wright. 2018. “Positive Energies? An Empirical Study of Community Energy Participation and Attitudes to Renewable Energy.” Energy Policy 118:612–625. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2018.03.062.

- Baxter, J., C. Walker, G. Ellis, P. Devine-Wright, M. Adams, and R. S. Fullerton. 2020. “Scale, History and Justice in Community Wind Energy: An Empirical Review.” Energy Research & Social Science 68:101532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2020.101532.

- Berka, A. L., and E. Creamer. 2018. “Taking Stock of the Local Impacts of Community Owned Renewable Energy: A Review and Research Agenda.” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 82:3400–3419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2017.10.050.

- Bidwell, D. 2013. “The Role of Values in Public Beliefs and Attitudes Towards Commercial Wind Energy.” Energy Policy 58:189–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2013.03.010.

- Byrne, B. M. 2013. Structural Equation Modeling with Mplus. New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203807644

- Chang, C., J. Gardiner, R. Houang, and Y.-L. Yu. 2020. “Comparing Multiple Statistical Software for Multiple-Indicator, Multiple-Cause Modeling: An Application of Gender 173 Disparity in Adult Cognitive Functioning Using MIDUS II Dataset.” BMC Medical Research Methodology 20 (1): 275. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-020-01150-4.

- Cohen, J. J., J. Reichl, and M. Schmidthaler. 2014. “Re-focussing Research Efforts on the Public Acceptance of Energy Infrastructure: A Critical Review.” Energy 76:4–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2013.12.056.

- Cowell, R. 2017. “Decentralising Energy Governance? Wales, Devolution and the Politics of Energy Infrastructure Decision-Making.” Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 35 (7): 1242–1263. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263774X16629443.

- Creamer, E., G. T. Aiken, B. Van Veelen, G. Walker, and P. Devine-Wright. 2019. “Community Renewable Energy: What Does it do? Walker and Devine-Wright (2008) Ten Years on.” Energy Research & Social Science 57:101223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2019.101223.

- Energy Saving Trust. 2021. Community and Locally Owned Energy in Scotland. https://energysavingtrust.org.uk/report/community-and-locally-owned-energy-in-scotland-2020-report/.

- Fan, Y., J. Chen, G. Shirkey, R. John, S. R. Wu, H. Park, and C. Shao. 2016. “Applications of Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) in Ecological Studies: An Updated Review.” Ecological Processes 5 (1): 19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13717-016-0063-3.

- Ferguson, M. D., D. Evensen, L. A. Ferguson, D. Bidwell, J. Firestone, T. L. Dooley, and C. R. Mitchell. 2021. “Uncharted Waters: Exploring Coastal Recreation Impacts, Coping Behaviors, and Attitudes Towards Offshore Wind Energy Development in the 176 United States.” Energy Research & Social Science 75:102029. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2021.102029.

- Firestone, J., W. Kempton, M. B. Lilley, and K. Samoteskul. 2012. “Public Acceptance of Offshore Wind Power: Does Perceived Fairness of Process Matter?” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 55 (10): 1387–1402. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2012.688658.

- Gibbs, E. 2021. “Scotland’s Faltering Green Industrial Revolution.” The Political Quarterly 92 (1): 57–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.12962.

- Goedkoop, F., and P. Devine-Wright. 2016. “Partnership or Placation? The Role of Trust and Justice in the Shared Ownership of Renewable Energy Projects.” Energy Research & Social Science 17:135–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2016.04.021.

- Gölz, S., and O. Wedderhoff. 2018. “Explaining Regional Acceptance of the German Energy Transition by Including Trust in Stakeholders and Perception of Fairness as Socio-Institutional Factors.” Energy Research & Social Science 43:96–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2018.05.026.

- Gross, C. 2007. “Community Perspectives of Wind Energy in Australia: The Application of a Justice and Community Fairness Framework to Increase Social Acceptance.” Energy Policy 35 (5): 2727–2736. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2006.12.013.

- Haggett, C., and M. Aitken. 2015. “Grassroots Energy Innovations: The Role of Community Ownership and Investment.” Current Sustainable/Renewable Energy Reports 2 (3): 98–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40518-015-0035-8.

- Hair, J., W. Black, B. Babin, and R. Anderson. 2010. Multivariate Data Analysis. 7th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education Limited.

- Hayes, A. 2013. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York, NY: Guilford Publications.

- Heffron, R. J. 2024. “Energy Justice – The Triumvirate of Tenets Revisited and Revised.” Journal of Energy & Natural Resources Law 42 (2): 227–233. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02646811.2023.2256593.

- Hoffman, S. M., and A. High-Pippert. 2010. “From Private Lives to Collective Action: Recruitment and Participation Incentives for a Community Energy Program.” Energy Policy 38 (12): 7567–7574. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2009.06.054.

- Hogan, J. L., C. R. Warren, M. Simpson, and D. McCauley. 2022. “What Makes Local Energy Projects Acceptable? Probing the Connection Between Ownership Structures and Community Acceptance.” Energy Policy 171:113257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2022.113257.

- IEA. 2021. Renewables 2021: Analysis and Forecasts to 2026. International Energy Agency. https://www.iea.org/reports/renewables-2021.

- Jenkins, K. E. H. 2019. “Energy Justice, Energy Democracy, and Sustainability: Normative Approaches to the Consumer Ownership of Renewables.” In Energy Transition, edited by J. Lowitzsch. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-93518-8_4.

- Jenkins, K., D. McCauley, R. Heffron, H. Stephan, and R. Rehner. 2016. “Energy Justice: A Conceptual Review.” Energy Research & Social Science 11:174–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2015.10.004.

- Jenkins, K. E. H., B. K. Sovacool, N. Mouter, N. Hacking, M.-K. Burns, and D. McCauley. 2021. “The Methodologies, Geographies, and Technologies of Energy Justice: A Systematic and Comprehensive Review.” Environmental Research Letters 16 (4): 043009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/abd78c.

- Jepson, W., C. Brannstrom, and N. Persons. 2012. “We Don’t Take the Pledge”: Environmentality and Environmental Skepticism at the Epicenter of US Wind Energy Development.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 43 (4): 851–863. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2012.02.002.

- Ki, J., S.-J. Yun, W.-C. Kim, S. Oh, J. Ha, E. Hwangbo, H. Lee, S. Shin, S. Yoon, and H. Youn. 2022. “Local Residents’ Attitudes About Wind Farms and Associated Noise 182 Annoyance in South Korea.” Energy Policy 163:112847. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2022.112847.

- Krumm, A., D. Süsser, and P. Blechinger. 2022. “Modelling Social Aspects of the Energy Transition: What Is the Current Representation of Social Factors in Energy Models?” Energy 239:121706. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2021.121706.

- Kumar, A., and G. T. Aiken. 2021. “A Postcolonial Critique of Community Energy: Searching for Community as Solidarity in India and Scotland.” Antipode 53 (1): 200–221. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12683.

- Lacey-Barnacle, M. 2022. “Residents Against Dirty Energy: Using Energy Justice to Understand the Role of Local Activism in Shaping Low-Carbon Transitions.” Local Environment 27 (8): 946–967. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2022.2090534.

- Leer Jørgensen, M., H. T. Anker, and J. Lassen. 2020. “Distributive Fairness and Local Acceptance of Wind Turbines: The Role of Compensation Schemes.” Energy Policy 138:111294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2020.111294.

- Leiren, M. D., S. Aakre, K. Linnerud, T. E. Julsrud, M.-R. Di Nucci, and M. Krug. 2020. “Community Acceptance of Wind Energy Developments: Experience from Wind Energy Scarce Regions in Europe.” Sustainability 12 (5): 1754. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12051754.

- Liu, L., T. Bouman, G. Perlaviciute, and L. Steg. 2020. “Public Participation in Decision Making, Perceived Procedural Fairness and Public Acceptability of Renewable Energy Projects.” Energy and Climate Change 1:100013. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egycc.2020.100013.

- Local Energy Scotland. 2023. Local Electricity Discount Schemes (LEDS). Energy Saving Trust. https://localenergy.scot/casestudy/local-electricity-discount-schemes-leds/.

- McCauley, D., R. J. Heffron, H. Stephan, and K. Jenkins. 2013. “Advancing Energy Justice: The Triumvirate of Tenets.” International Energy Law Review 32 (3): 107–110. http://hdl.handle.net/1893/18349.

- Mills, S. B., D. Bessette, and H. Smith. 2019. “Exploring Landowners’ Post-Construction Changes in Perceptions of Wind Energy in Michigan.” Land Use Policy 82:754–762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.01.010.

- Mueller, C. E. 2020. “Examining the Inter-Relationships Between Procedural Fairness, Trust in Actors, Risk Expectations, Perceived Benefits, and Attitudes Towards Power Grid Expansion Projects.” Energy Policy 141:111465. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2020.111465.

- Mulder, P., F. Dalla Longa, and K. Straver. 2023. “Energy Poverty in the Netherlands at the National and Local Level: A Multi-Dimensional Spatial Analysis.” Energy Research & Social Science 96:102892. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2022.102892.

- Musall, F. D., and O. Kuik. 2011. “Local Acceptance of Renewable Energy—A Case Study from Southeast Germany.” Energy Policy 39 (6): 3252–3260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2011.03.017.

- National Records of Scotland. 2011. Scotland’s Census 2011. https://www.scotlandscensus.gov.uk/.

- Ólafsdóttir, R., and A. D. Sæþórsdóttir. 2019. “Wind Farms in the Icelandic Highlands: Attitudes of Local Residents and Tourism Service Providers.” Land Use Policy 88:104173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.104173.

- Philpott, A., and R. Windemer. 2022. “Repower to the People: The Scope for Repowering to Increase the Scale of Community Shareholding in Commercial Onshore Wind Assets in Great Britain.” Energy Research & Social Science 92:102763. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2022.102763.

- Ponnapureddy, S., J. Priskin, F. Vinzenz, W. Wirth, and T. Ohnmacht. 2020. “The Mediating Role of Perceived Benefits on Intentions to Book a Sustainable Hotel: A Multi-Group Comparison of the Swiss, German and USA Travel Markets.” Journal of Sustainable Tourism 28 (9): 1290–1309. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1734604.

- Ranki, F. 2024. Planning policy for onshore wind in England. UK Parliament, House of Commons Library. https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/sn04370/.

- Rasch, E. D., and M. Köhne. 2017. “Practices and Imaginations of Energy Justice in Transition. A Case Study of the Noordoostpolder, the Netherlands.” Energy Policy 106:607–614. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2017.03.037.

- Roddis, P., S. Carver, M. Dallimer, P. Norman, and G. Ziv. 2018. “The Role of Community Acceptance in Planning Outcomes for Onshore Wind and Solar Farms: An Energy Justice Analysis.” Applied Energy 226:353–364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2018.05.087.

- Rogers, J. C., E. A. Simmons, I. Convery, and A. Weatherall. 2012. “What Factors Enable Community Leadership of Renewable Energy Projects? Lessons from a Woodfuel Heating Initiative.” Local Economy: The Journal of the Local Economy Policy Unit 27 (2): 209–222. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0269094211429657.

- Salisbury, W. D., W. W. Chin, A. Gopal, and P. R. Newsted. 2002. “Research Report: Better Theory Through Measurement—Developing a Scale to Capture Consensus on Appropriation.” Information Systems Research 13 (1): 91–103. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.13.1.91.93.

- Scottish Government. 2019a. Scottish Government Good Practice Principles for Community Benefits from Onshore Renewable Energy Developments. https://www.gov.scot/publications/scottish-government-good-practice-principles-community-benefits-onshore-renewable-energy-developments/.

- Scottish Government. 2019b. Shared Ownership of Onshore Renewable Energy Developments. https://www.gov.scot/publications/scottish-government-good-practice-principles-shared-ownership-onshore-renewable-energydevelopments/.

- Scottish Government. 2022. Onshore Wind: Policy Statement 2022. https://www.gov.scot/publications/onshore-wind-policy-statement-2022/.

- Simcock, N. 2014. “Exploring How Stakeholders in Two Community Wind Projects Use a “Those Affected” Principle to Evaluate the Fairness of Each Project’s Spatial Boundary.” Local Environment 19 (3): 241–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2013.788482.

- Simcock, N. 2016. “Procedural Justice and the Implementation of Community Wind Energy Projects: A Case Study from South Yorkshire, UK.” Land Use Policy 59:467–477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2016.08.034.

- Simcock, N., K. E. H. Jenkins, M. Lacey-Barnacle, M. Martiskainen, G. Mattioli, and D. Hopkins. 2021. “Identifying Double Energy Vulnerability: A Systematic and Narrative Review of Groups at-Risk of Energy and Transport Poverty in the Global North.” Energy Research & Social Science 82:102351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2021.102351.

- Slee, B. 2020. “Social Innovation in Community Energy in Scotland: Institutional Form and Sustainability Outcomes.” Global Transitions 2:157–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.glt.2020.07.001.

- Slee, B., and J. Harnmeijer. 2017. “Community Renewables: Balancing Optimism with Reality.” In A Critical Review of Scottish Renewable and Low Carbon Energy Policy, edited by G. Wood and K. Baker, 35–64. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Stephens, S., and B. M. K. Robinson. 2021. “The Social License to Operate in the Onshore Wind Energy Industry: A Comparative Case Study of Scotland and South Africa.” Energy Policy 148:111981. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2020.111981.

- Toke, D., S. Breukers, and M. Wolsink. 2008. “Wind Power Deployment Outcomes: How Can We Account for the Differences?” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 12 (4): 1129–1147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2006.10.021.

- van Bommel, N., and J. I. Höffken. 2021. “Energy Justice Within, Between and Beyond European Community Energy Initiatives: A Review.” Energy Research & Social Science 79:102157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2021.102157.

- Vaske, J. J. 2019. Survey Research and Analysis. 2nd ed. Urbana: Sagamore-Venture.

- Velasco-Herrejon, P., and T. Bauwens. 2020. “Energy Justice from the Bottom up: A Capability Approach to Community Acceptance of Wind Energy in Mexico.” Energy Research & Social Science 70:101711. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2020.101711.

- Walker, C., and J. Baxter. 2017a. ““It’s Easy to Throw Rocks at a Corporation”: Wind Energy Development and Distributive Justice in Canada.” Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning 19 (6): 754–768. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2016.1267614.

- Walker, C., and J. Baxter. 2017b. “Procedural Justice in Canadian Wind Energy Development: A Comparison of Community-Based and Technocratic Siting Processes.” Energy Research & Social Science 29:160–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2017.05.016.

- Walker, C., J. Baxter, and D. Ouellette. 2015. “Adding Insult to Injury: The Development of Psychosocial Stress in Ontario Wind Turbine Communities.” Social Science & Medicine 133: 358–365. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.07.067.

- Walker, G., and P. Devine-Wright. 2008. “Community Renewable Energy: What Should it Mean?” Energy Policy 36 (2): 497–500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2007.10.019.

- Walker, G., P. Devine-Wright, S. Hunter, H. High, and B. Evans. 2010. “Trust and Community: Exploring the Meanings, Contexts and Dynamics of Community Renewable Energy.” Energy Policy 38 (6): 2655–2663. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2009.05.055.

- Walker, G., S. Hunter, P. Devine-Wright, B. Evans, and H. Fay. 2007. “Harnessing Community Energies: Explaining and Evaluating Community-Based Localism in Renewable Energy Policy in the UK.” Global Environmental Politics 7 (2): 64–82. https://doi.org/10.1162/glep.2007.7.2.64.

- Walsh, B. 2016. “Community: A Powerful Label? Connecting Wind Energy to Rural Ireland.” Community Development Journal 53 (2): 228–245. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bsw038.

- Warren, C. R., and R. V. Birnie. 2009. “Re-powering Scotland: Wind Farms and the ‘Energy or Environment?’ Debate.” Scottish Geographical Journal 125 (2): 97–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/14702540802712502.

- Warren, C. R., and M. McFadyen. 2010. “Does Community Ownership Affect Public Attitudes to Wind Energy? A Case Study from South-West Scotland.” Land Use Policy 27 (2): 204–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2008.12.010.

- Welsh Government. 2022. Energy Generation in Wales. https://www.gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2023-11/energy-generation-in-wales-2022.pdf#page = 46&zoom = 100,0,0.

- Wirth, S. 2014. “Communities Matter: Institutional Preconditions for Community Renewable Energy.” Energy Policy 70:236–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2014.03.021.

- Wolsink, M. 2007. “Wind Power Implementation: The Nature of Public Attitudes: Equity and Fairness Instead of ‘Backyard Motives.” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 11 (6): 1188–1207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2005.10.005.

- Wood, G. 2017. “Large-Scale Renewables: Policy and Practice Under Devolution.” In A Critical Review of Scottish Renewable and Low Carbon Energy Policy, edited by G. Wood and K. Baker, 13–34. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-56898-0_2.