ABSTRACT

Despite a growing focus on climate justice, prior research has revealed scant details about how marginalised groups have been engaged in local climate adaptation processes. This study aims to understand how justice is considered in these processes through a qualitative review of climate adaptation plans and related documents from US municipalities. We reviewed 101 plans published between 2010 and 2021 using the three-dimensional framework of recognitional, distributional, and procedural justice. Overall, our findings revealed a stronger focus on recognitional and distributional justice than procedural. Recognitional justice mainly focused on who is most vulnerable to climate change and how, with most plans adopting a similar understanding of vulnerability. Plans less frequently acknowledged how historical injustices contribute to vulnerability. Distributional justice was addressed through adaptation strategies across six areas (e.g. health and safety, buildings, green infrastructure, professional development, food, and transit), focusing greater attention on expanding existing programmes than new initiatives. Little attention was given to the potential negative impacts of proposed strategies. Procedural justice was mainly considered through one-off opportunities, rather than more extensive engagement in decision-making. Most plans lacked implementation considerations, for justice or otherwise, but when included, details mainly focused on who would be involved and not how strategies would be implemented. These findings provide an array of approaches to incorporate justice in adaptation planning and support several considerations for developing future plans.

Introduction

Social justice concerns are increasingly at the forefront of climate adaptation discussions (Bulkeley et al. Citation2013; Klinsky et al. Citation2017; Shi et al. Citation2016). Not only will climate change affect some geographies more than others, but many individuals, such as the elderly, youth, people with pre-existing medical conditions, and low-income residents, may also be less able to cope with climate impacts (Reckien et al. Citation2018; White-Newsome, Meadows, and Kabel Citation2018). People of colour, indigenous people, and immigrants have also been historically excluded from community planning processes and disenfranchised as a result (Anguelovski et al. Citation2016). Centring justice in climate adaptation processes and engaging marginalised groups can help ensure adaptation efforts address existing injustices, enhance the legitimacy of decisions, and increase the likelihood of long-term success in implementing adaptation projects (Byskov et al. Citation2021; Guyadeen, Thistlethwaite, and Henstra Citation2019; Paavola and Adger Citation2006). If adaptation processes neglect to engage marginalised individuals, initiatives may reinforce existing social vulnerabilities, result in negative consequences, and fail to generate support, or draw active opposition, from those that stand to be most impacted (Adger Citation2016; Anguelovski et al. Citation2016; Shi et al. Citation2016).

Despite the growing focus on climate justice, it is unclear how local governments are operationalising justice within climate adaptation planning. Prior research suggests considerable variation in whether and how communities address justice in their approaches (Anguelovski et al. Citation2016; Chu and Cannon Citation2021; Fiack et al. Citation2021; Meerow, Pajouhesh, and Miller Citation2019). When justice is considered, communities mainly focus on ensuring marginalised residents experience the benefits of adaptation projects (Anguelovski et al. Citation2016; Finn and McCormick Citation2011; Meerow, Pajouhesh, and Miller Citation2019). While expanding access to services and resources can help marginalised community members adapt, existing literature recommends a more holistic approach that also focuses on recognising the link between existing injustices and vulnerability to climate change and engaging marginalised residents in adaptation planning (Holland Citation2017; Schlosberg and Collins Citation2014). To date, most analyses of adaptation planning processes reveal ambiguity around who is considered most vulnerable to climate impacts and scant details about how communities engaged marginalised groups (Baker et al. Citation2012; Bulkeley et al. Citation2013; Finn and McCormick Citation2011; Meerow, Pajouhesh, and Miller Citation2019). Some studies have shown that planning approaches often end with broad goals, lacking specific details on how local governments plan to implement these strategies or track implementation (Meerow, Pajouhesh, and Miller Citation2019; Mullenbach and Wilhelm Stanis Citation2024).

Climate adaptation plans provide a tool through which communities can consider justice as they prepare for climate change. Climate adaptation plans can vary widely in their approaches, but these documents generally contain details about existing vulnerabilities to climate change, future climate impacts, and strategies to address these impacts (Woodruff and Stults Citation2016). While these plans are often non-binding documents (Hess and McKane Citation2021; Long and Rice Citation2019), they provide a reference point for understanding how (and whether) communities consider justice in their adaptation approaches. To date, most reviews of these documents have focused on plans from the largest cities (Cannon et al. Citation2023; Fiack et al. Citation2021; Meerow, Pajouhesh, and Miller Citation2019) or how justice has been addressed within specific sectors, such as health (Mullenbach and Wilhelm Stanis Citation2024). We systematically reviewed climate adaptation plans and related climate plans from communities in the United States published between 2010 and 2021 to address the following research questions:

Who is considered vulnerable to climate change and how is vulnerability assessed in these documents?

How and to what extent is justice (recognitional, distributional, and procedural) for marginalised communities addressed in these same plans?

Literature review

Vulnerability to climate change

Vulnerability to climate change can be defined as the extent to which systems, institutions, people, and other entities are susceptible to harm caused by climate hazards (Paavola and Adger Citation2006; Pörtner et al. Citation2022). Vulnerability is often broken into two categories: biophysical vulnerability, or the tangible impacts an entity may experience when exposed to climate hazards, and social vulnerability, which is the focus of this study. Social vulnerability is defined as the susceptibility to climate impacts based on existing social, economic, and political factors, which might include characteristics like income, employment, access to public services/resources, and pre-existing medical conditions (Adger and Kelly Citation1999). Social vulnerability is largely context dependent and can shift over time, which may challenge efforts to recognise and engage the “relevant” actors in climate adaptation planning (Chu and Michael Citation2019; Shi et al. Citation2016). For example, a wealthier community may be equipped to build flood-resilient infrastructure, but after exhausting their resources, they may find it challenging to maintain these structures and financially vulnerable to other hazards (van den Berg and Keenan Citation2019).

Defining social justice in climate adaptation planning

We conceptualise climate justice based on Schlosberg’s (Citation2007) three-dimensional theory, which includes recognitional, distributional, and procedural justice. We use the term “marginalised groups” to refer to people that may be disproportionately impacted by climate change due to existing social vulnerabilities and current or historic inequalities (Anguelovski et al. Citation2016; Reckien et al. Citation2018). In this study, we focus on the extent to which each form of justice reflects the purposeful inclusion of marginalised groups.

Recognitional justice

To advance justice, scholars argue that it is essential to first recognise the social structures and policies that have created injustices, which may prevent marginalised individuals from accessing benefits or participating in these opportunities (Bulkeley et al. Citation2013; Schlosberg Citation2004). In the context of climate adaptation, how communities conceptualise vulnerability and recognise those most at-risk informs their approach to address these vulnerabilities, as well as who to engage in decision-making processes. Adaptation planning processes may privilege certain groups’ participation, exclude others, and risk prioritising investments that fail to account for (or address) existing injustices or exacerbate current conditions (Anguelovski et al. Citation2016; van den Berg and Keenan Citation2019). Therefore, this recognition can be viewed as an entry point or pre-condition to address the other types of justice (Bulkeley, Edwards, and Fuller Citation2014).

Recognitional justice acknowledges elements of residents’ identities that may increase their vulnerability to climate change, the existing injustices these individuals face, and how historical or existing policies influence these injustices (Chu and Michael Citation2019; Meerow, Pajouhesh, and Miller Citation2019). To address recognitional justice in climate adaptation planning, communities can acknowledge these elements of vulnerability and work to change institutional norms/culture that often perpetuate injustices (Meerow, Pajouhesh, and Miller Citation2019; Schlosberg Citation2007). For example, Meerow, Pajouhesh, and Miller (Citation2019) described how urban resilience plans identified marginalised groups, the injustices they face, and historical discriminatory practices/policies that contributed to their vulnerability. We expand upon their definition by also looking for examples of how marginalised groups may be currently impacted by climate change and in the future.

Distributional justice

Distributional, or distributive, justice concerns the fair distribution of goods and benefits in society (Rawls Citation1971). When it comes to climate adaptation planning, distributional justice occurs through initiatives that enhance access to goods, services, infrastructure, and other opportunities to all those who need them to overcome vulnerabilities (Meerow, Pajouhesh, and Miller Citation2019). Common adaptation projects designed to benefit marginalised communities include the development of infrastructure (e.g. green space, cooling centres, public transit), outreach to enhance social support networks, and educational resources about the health risks associated with climate change (Bulkeley, Edwards, and Fuller Citation2014; Castán Broto, Oballa, and Junior Citation2013; Preston, Westaway, and Yuen Citation2011). These efforts are often grouped into three categories based on the extent to which strategies shift existing conditions: resistance, resilience, and transformation actions (Pelling Citation2010; Peterson St-Laurent et al. Citation2021; Stein et al. Citation2013). Resistance efforts work to maintain current conditions by ameliorating climate impacts; resilience strategies enhance the capacity of infrastructure or people to rebound from disturbances or maintain function under new conditions; and transformative projects aim to change, relocate, or re-envision underlying structures. All three approaches can reduce injustice. Adaptation actions have also been described as incremental or transformative (Kates, Travis, and Wilbanks Citation2012). In this framework, incremental actions may be seen as slower or less complete than transformative in addressing injustice.

Distributional justice also considers how members of marginalised communities may be negatively impacted by climate adaptation, as some projects can result in maladaptive outcomes that exacerbate existing vulnerabilities or create new issues for residents (Anguelovski et al. Citation2016; Barnett and O’Neill Citation2010; Swanson Citation2021). Unanticipated impacts of climate adaptation initiatives may include segregation, gentrification, displacement, and inequitable access to infrastructure (Anguelovski et al. Citation2016; Long and Rice Citation2019; Sovacool, Linnér, and Goodsite Citation2015). Our conceptualisation of distributional justice is similar to Meerow, Pajouhesh, and Miller’s (Citation2019), which considers initiatives that enhance access to resources and services, but we also track examples flagging potential negative consequences of proposed strategies.

Procedural justice

Procedural justice is focused on ensuring public engagement processes are fair, transparent, and inclusive of a variety of perspectives (Schlosberg Citation2007). Procedural justice seeks to move public engagement beyond informing or consulting community members by empowering them to participate in decision-making (Holland Citation2017; Malloy and Ashcraft Citation2020; Shi et al. Citation2016). In the field of climate adaptation and resilience planning, Meerow, Pajouhesh, and Miller (Citation2019) consider procedural justice to include any efforts to encourage participation in plan development and implementation. For our analysis, we focus on efforts to engage marginalised groups in adaptation processes. This narrower focus involves designing processes that consider the needs of marginalised groups; incorporating material that resonates with participants’ identities; and expanding broader participation through engaging trusted people or organisations (Phadke, Manning, and Burlager Citation2015; Stern et al. Citation2020).

Elements of adaptation plan quality

To inform our understanding of how justice is addressed in adaptation planning, we focus on two characteristics that have been used to characterise plan quality: the inclusion of (1) implementation details and (2) metrics to monitor plan implementation (Baker et al. Citation2012; Guyadeen, Thistlethwaite, and Henstra Citation2019; Stults and Woodruff Citation2017). Implementation considerations include identifying leads and partners for adaptation strategies (Berke and Lyles Citation2013; Berke, Smith, and Lyles Citation2012); outlining timelines and funding sources to implement proposed actions (Berke, Smith, and Lyles Citation2012; Horney et al. Citation2017; Hughes Citation2015); and operationalising adaptation objectives through measurable targets or additional details (Bassett and Shandas Citation2010). Monitoring or evaluation steps include developing indicators, criteria, or questions for tracking implementation strategies (Baker et al. Citation2012; Li and Song Citation2016). These elements speak to the extent to which the plans have made specific commitments to addressing justice issues when planning shifts toward implementation but do not assess how vulnerability was reduced for marginalised communities.

Methods

Data collection

We selected plans for review based on five criteria. We selected plans that were (1) focused solely on climate adaptation or included adaptation strategies as part of a larger climate action plan, (2) focused on a specific US city or county, (3) written by or involved the support of a US city/county government and had been adopted by the community, (4) covered adaptation strategies across multiple sectors within a city/county (e.g. we excluded plans focused only on a single section, such as transportation or energy), and (5) were published between 2010 and 2021. If a city or county released more than one climate plan during the study period, we evaluated all plans that met our criteria.

These criteria excluded plans that did not focus solely on climate change (e.g. hazard mitigation plans, sustainability plans), plans that were written without local government involvement or were not formally adopted, plans focused solely on municipal operations, and any multi-county, regional, or state climate plans. When plans focused on both climate mitigation and adaptation, we reviewed the entire plan but only evaluated the content related to climate adaptation (i.e. information about climate impacts and adaptation strategies). We excluded climate action plans that didn’t explicitly differentiate between climate mitigation and adaptation strategies to ensure we were not arbitrarily deciding which material was related to adaptation. We also excluded any plans that were labelled as “draft plans” for which we were unable to acquire the final version.

We searched for plans in three online adaptation databases: the Georgetown Climate Center (Georgetown Climate Center Citation2022b), the closely associated Adaptation Clearinghouse (Georgetown Climate Center Citation2022a), and the Climate Adaptation Knowledge Exchange (CAKE) (EcoAdapt Citation2022). To differentiate plans from other adaptation resources (e.g. assessments, case studies) on Georgetown’s Adaptation Clearinghouse, we only included documents categorised as “Planning” resources within that database. We also identified plans through Google searches by state by searching each state’s name followed by the terms “adaptation plan”, “climate action plan”, and “climate resilience plan”, as these were common terms found in our earlier searches of online adaptation databases. We reviewed the first 10 pages of results for each keyword search. In total, we collected 156 plans, of which 112 met our criteria for evaluation.

Coding scheme and analysis

We developed a qualitative coding scheme based on the three-pronged framework of recognitional, distributional, and procedural justice. We coded the selected plans through a two-stage qualitative coding process. In phase one, we created a spreadsheet with deductive codes adapted from Meerow, Pajouhesh, and Miller (Citation2019) coding scheme. To understand how plans addressed recognitional justice, we tracked how plans identified groups vulnerable to climate change, discussed the historical and continuing injustices affecting these groups, and documented how these groups will experience the impacts of climate change. To code distributional justice, we identified any adaptation strategies that emphasised benefits to marginalised groups and coded them by the strategies or projects they were framed around (e.g. enhancing access to resources, infrastructure, economic opportunities). Procedural justice codes addressed the extent to which plans describe marginalised groups’ engagement in plan development and implementation. We define engagement as any efforts explicitly prioritising marginalised groups that sought to gather their feedback on plan content, involve them in developing adaptation strategies, include them in implementing proposed programmes/projects, or elicit additional input when implementing strategies. We also coded for any monitoring/evaluation metrics proposed to assess outcomes and initiatives related to any forms of justice.

We assigned numerical weights to each code, as described in , to account for the degree to which each was elucidated or emphasised within the plans. For each code, plans scored a zero if that element of justice wasn’t addressed, a one if the code was addressed but only at a general level (low degree), or a two if the code was addressed and included concrete details or implementation considerations (high degree). We calculated the overall score for each type of justice and for monitoring/evaluation, based on the highest level observed in each plan (i.e. based on the subcodes that made up each justice theme). Four researchers tested the coding scheme by pilot coding four plans that met our criteria and storing examples of the different codes in a spreadsheet. After each researcher reviewed each plan, the team discussed and reconciled all disagreements to refine the coding scheme. After this initial review, the lead author reviewed and coded the remaining plans, copying relevant examples into the spreadsheet.

Table 1. Coding scheme for our plan review.

After the first stage of coding, we evaluated the resulting examples and decided to recode the distributional justice strategies based on focus area. This reclassification better aligns with how these plans were organised and relevant literature on climate plan evaluation (Diezmartínez and Short Gianotti Citation2022; Hess and McKane Citation2021). These focus areas included health and safety, buildings, professional development opportunities, green infrastructure, food, and transit. In this second stage of coding, we also reviewed recognitional justice examples and developed additional codes to track the specific injustices addressed in each plan (see ). We also tracked if plans highlighted potential negative impacts of proposed strategies and which marginalised groups were considered in recognitional, distributional, and procedural justice examples. Co-authors provided quality checks and feedback throughout the process.

Table 2. Summary of codes for marginalised groups and injustices they experience.

Results

Study sample details

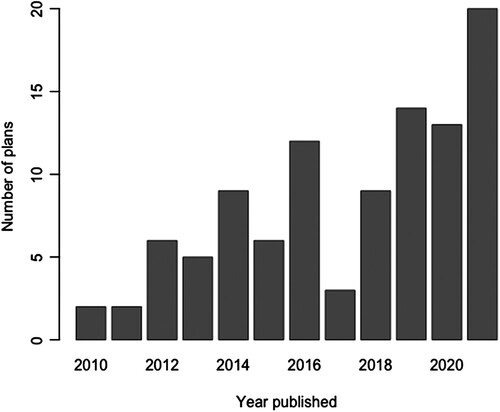

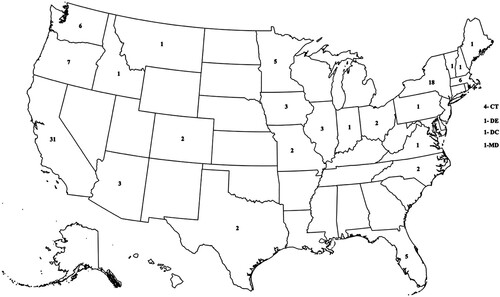

The 112 plans in the original sample were mainly published between 2014–2016 and 2019–2021, with fewer plans published before 2014 and in 2017 and 2018 (see ). The plans came from 30 states, with the majority from communities in the Northeast and along the Pacific Coast (see for a map of plans by state). Three communities published an original plan and an update to that plan that both met our criteria, so we reviewed both plans from these communities (Broward County, FL, Cleveland, OH and King County, WA). Based on the National Center for Education Statistics’ (NCES) community classification system (National Center for Education Statistics Citation2021), most plans came from cities (n = 52) or suburban areas (n = 43). Twelve of the plans were county-level documents, while the rest were from cities or other single communities (see Supplementary Material for complete list of plans and additional details).

Figure 2. Map of plans by state, with the number of plans per state in parentheses. Credit for map of US from Venmaps.

Twelve plans in our sample were from the same region in upstate New York, created by the same regional planning organisation, published between 2014 and 2016, and were largely identical to each other. These plans all addressed justice in the same way (low recognitional justice, low distributional justice, and did not address procedural justice or monitoring). To avoid skewing our data, we selected the largest community (Cortland, NY) to include in further analysis and excluded the other 11 plans. The resulting sample for subsequent analyses is thus 101 plans.

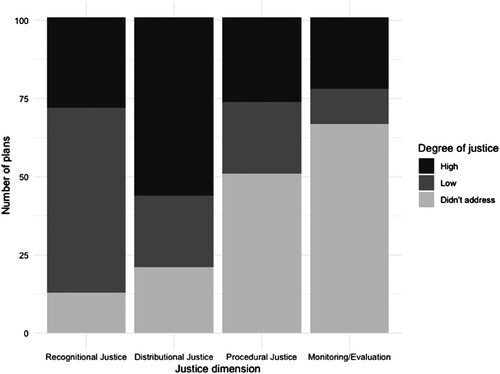

Overall trends in justice

Overall, plans in our sample addressed recognitional and distributional justice to a greater extent than procedural justice, and monitoring/evaluation was rarely addressed (). Though most plans addressed recognitional justice to some degree, only 26 plans described how certain groups’ may be more vulnerable to climate change and explained how they assessed social vulnerability (high degree). Fifty-seven plans included details about how they planned to implement adaptation strategies related to distributional justice (high degree). Twenty-seven plans in our sample described detailed actions to engage marginalised groups in their adaptation processes (high degree of procedural justice), and 23 plans included details about monitoring the impacts of proposed adaptation initiatives (high degree of monitoring/evaluation). In the following sections, we summarise the key findings for each dimension of justice and provide examples. We discuss trends we observed over time and across contexts in our complementary piece in this journal (Brousseau, Stern, and Hansen Citation2024).

Elements of recognitional justice

Identification of marginalised groups

Most plans (n = 88) identified specific groups that may be disproportionately impacted by climate change and described these groups as “vulnerable populations”. Other terms for these groups included “underserved populations”, “sensitive populations”, “disadvantaged groups”, “marginalised communities”, and “frontline communities”. Of these plans, most identified low-income (n = 76), youth (n = 72), elderly (n = 72), people with existing medical conditions (n = 64), non-English speakers (n = 50), and people of colour (n = 46) as more vulnerable to climate impacts. Other marginalised groups included outdoor workers (n = 41), unhoused people (n = 33), indigenous people (n = 20), renters (n = 17), and pregnant women (n = 13).

Marginalised groups’ vulnerability to climate impacts

Of the 88 plans that identified marginalised groups, 67 described how specific groups may be disproportionately affected by climate impacts. Nearly all these plans (n = 59) framed marginalised groups’ vulnerability to climate change around the health impacts they may experience due to climate hazards (e.g. extreme heat, wildfire smoke). Plans mainly described elderly, youth, and those with pre-existing health conditions as more vulnerable to poor air quality caused by wildfire smoke and extreme heat events. Several plans also acknowledged that outdoor workers may be disproportionately affected by these events due to their working conditions and inability to seek shelter. Forty-three plans also described marginalised groups’ reduced capacity/resources to deal with climate-related events. Reduced capacity was most often discussed for low-income households that may struggle to pay higher utility bills associated with extreme heat or cold. Fewer plans (n = 16) acknowledged that marginalised groups would face challenges in recovering from extreme weather events, such as rebuilding homes or recovering lost wages. Twenty-six plans described how vulnerable groups were identified, mainly through social vulnerability assessments. Most of these assessments involved mapping where marginalised groups live and work relative to climate hazards.

Existing injustices experienced by marginalised groups

Most plans (n = 78) also described existing injustices that may contribute to marginalised groups’ vulnerability to climate impacts. Of these plans, 70 identified a lack of money, 65 highlighted a lack of access to adequate health care/services, and 50 noted a lack of access to affordable housing. Plans also noted marginalised groups’ lack of access to information, healthy food, transportation, cooling, green space, and social connections. Thirty plans attributed existing injustices to discriminatory government practices, such as housing policies that pushed individuals to live near floodplains, near hazardous waste/other polluted areas, or in housing that is poorly equipped for climate hazards. This historic marginalisation was most often associated with communities of colour, low-income individuals, and non-English speakers. Several plans also acknowledged that marginalised groups have been historically excluded from civic engagement processes.

Elements of distributional justice

Of the 80 plans that addressed distributional justice, most described strategies aimed at improving the health and safety of marginalised groups (n = 55); making buildings used by marginalised groups more resilient (n = 48); and enhancing access to jobs and educational opportunities for marginalised groups (n = 42). Fewer plans described strategies that enhanced access to green infrastructure (n = 33), food (n = 29), or transit (n = 26) for members of marginalised groups. We identified 20 types of adaptation strategies aimed at enhancing marginalised groups’ access to resources, services, or other opportunities (). For a list of examples for each type of strategy, see additional tables in the Supplementary Material.

Table 3. Adaptation strategies related to each focus area and organised by the most and least reported strategies within each area.

Of the plans that addressed distributional justice, 57 included some details about the implementation of proposed adaptation strategies. These details mainly involved identifying leads and partners who would be responsible for implementing these strategies (n = 45). Most included the names of relevant entities but did not describe their roles or responsibilities. Nineteen plans described intentions to model new programmes off existing ones or leverage existing tools during implementation. For example, several proposed expanding existing food donation or low-income weatherisation programmes. Fewer plans (n = 12) identified specific locations for their proposed strategies, such as where to situate community gardens or cooling centres. Only four plans described funding sources they intended to use to implement proposed strategies.

Twenty-four plans acknowledged that proposed strategies could create unintended negative consequences for the groups they intended to benefit. These included the potential for gentrification, associated risk of displacement, and heightened fees for public services, like utilities. Only two plans described efforts to reduce the risks of these unintended consequences, which involved offering legal and financial assistance for those facing eviction.

Elements of procedural justice

Engaging marginalised groups in plan development

While almost half of plans in our sample described their community engagement processes (n = 44), only 22 plans described specific efforts to engage marginalised groups. Sixteen of those plans included details about how they engaged these groups, which included online and in-person surveys, interviews, focus groups, and workshops. Several plans highlighted elements of focus groups or workshops intended to make these events more accessible for marginalised groups, including holding events in neighbourhoods where many marginalised groups live and providing meals, stipends, and headsets for those hard of hearing. Most of these efforts focused on one-off opportunities that either informed residents about the content of these plans or solicited feedback. Only three plans described how that feedback was incorporated. Some communities may have conducted more robust engagement processes but did not include details in the final plans.

Stakeholder advisory committees were described in 13 plans. These committees were tasked with considering how adaptation strategies might harm or benefit marginalised groups. Two plans described involving community organisations that work with marginalised individuals, and three plans indicated that members of these marginalised groups were included on the committees. These plans included few details about how these committees’ feedback was integrated into the plans or how decisions were made. One exception, King County’s second Climate Action Plan (WA), had a “Climate Equity Community Task Force (CECTF)” that was responsible for creating the “Sustainable Frontline and Resilient Communities” (SFRC) chapter of the plan and “developing the community-driven and equity-oriented climate actions represented in the SRFC section” (183). This task force was composed of leaders from frontline communities, which included communities of colour, immigrants, refugees, indigenous communities, limited-English speakers, youth, low-income individuals, and communities with existing social and health disparities.

Engaging marginalised groups in implementing the plan

Forty-four plans described aims to engage marginalised groups in implementing the plan. Efforts for engaging marginalised groups included: (1) building partnerships, (2) engaging them in decision making, or (3) involving them in additional outreach. Only 12 of those plans included details about how marginalised groups would be engaged rather than describing general intentions to engage these communities moving forward. A few plans also proposed a stakeholder advisory committee in the implementation phase. These plans more explicitly acknowledged bringing marginalised voices to the decision-making table to advance justice through climate adaptation actions. Apart from the advisory committee, the strategies proposed focused mainly on informing or consulting marginalised groups during implementation.

Strategies for specific marginalised groups

Distributional justice strategies focused more on enhancing access for low-income individuals (n = 50), youth (n = 36), non-English speakers (n-30), and elderly (n = 25) than the other marginalised groups. Procedural justice approaches mainly focused on engaging youth (n = 24), people of colour (n = 19), and non-English speakers (n = 14). Engaging non-English speakers most often involved disseminating outreach materials in multiple languages or having interpreters on-hand for in-person or virtual events. Plans described a range of strategies to engage youth in plan development and implementation, which included appointing youth representatives to the local Climate Action Committee; using creative projects to solicit feedback through song, spoken word or other creative outlet; and engaging youth as “climate ambassadors” to learn more about climate adaptation strategies and then share this information with other people they know. For more information about how marginalised groups were considered in distributional and procedural justice strategies, see the Supplementary Material.

Monitoring/evaluation

Of the 34 plans in our sample that described intentions to monitor how adaptation strategies advance justice, 23 included specific details, such as indicators or checklists. Indicators included measurable targets local governments could use to assess the benefits and costs that climate policies or adaptive actions create for marginalised groups. Several plans also created decision-making framework tools consisting of a set of questions or checklists to consider before, during, and after implementing programmes to incorporate justice concerns throughout the process. For example, Cleveland’s Racial Equity Tool from their second Climate Action Plan listed five criteria to evaluate their projects, including how strategies (1) consider language, (2) increase accountability, (3) address disproportionate impacts, (4) advance economic opportunities, and (5) enhance neighbourhood engagement for people of colour.

Discussion

While any community with a climate adaptation plan that considers how to address vulnerabilities to climate change is already inherently addressing justice issues to some extent, we examined differences in how recognitional, distributive, and procedural justice were explicitly considered within planning documents across the US. Plans in our sample addressed recognitional and distributional justice to a greater extent than procedural justice. Few documents described plans to monitor how adaptation actions might influence justice outcomes. In our companion piece in this journal, we aim to better understand the observed variation in these considerations by examining trends in how justice was addressed over time and associated with other community characteristics (Brousseau, Stern, and Hansen Citation2024). Below, we discuss these results compared to existing literature and suggest considerations for future adaptation planning informed by our findings.

Recognitional justice: acknowledging history

Most plans adopted a similar, broad understanding of vulnerability and of who is most marginalised (low-income individuals, elderly, youth, those with pre-existing medical conditions, non-English speakers, and people of colour). These findings align closely with existing literature about social vulnerability (Reckien et al. Citation2018; White-Newsome, Meadows, and Kabel Citation2018). The plans less frequently acknowledged how government policies/programmes have historically discriminated against certain groups and contributed to existing injustices, which a similar review of climate adaptation plans also found to be lacking in these documents (Zoll Citation2022).

Recognising how past and existing government policies have contributed to some residents’ vulnerability to climate change can help to repair feelings of distrust among impacted communities (Gillespie and Dietz Citation2009; Stern and Baird Citation2015) and hold municipalities accountable for rectifying these harms (Kania et al. Citation2022; Zoll Citation2022). Enhancing accountability and trust may be a first step towards centring justice in community processes and encouraging marginalised individuals’ engagement in future projects (Kania et al. Citation2022). Coupling historical analyses/accounts with social vulnerability assessments could be a meaningful step in this direction. For example, redlining is a government policy from the 1930s that categorised neighbourhoods which were predominantly low-income, communities of colour as “hazardous” for real estate investments, resulting in reduced access to loans, subsequent disinvestment, and segregation (Aaronson, Hartley, and Mazumder Citation2021). In a recent study, Hoffman, Shandas, and Pendleton (Citation2020) assessed how current urban heat exposure may result from historical policies and how present-day planning practices may exacerbate these conditions. Pinpointing the impacts of redlining or other historical policies could inform the design of adaptation strategies, that prioritise adaptation projects in vulnerable, historically underserved areas.

Distributional justice: advancing transformative adaptation through incremental initiatives

Similar to other reviews, our findings revealed a wide diversity across focus areas (Diezmartínez and Short Gianotti Citation2022; Hess and McKane Citation2021; Meerow, Pajouhesh, and Miller Citation2019), with distributional justice most commonly addressed through public health strategies (Chu and Cannon Citation2021; Fiack et al. Citation2021). The strong focus on reducing marginalised individuals’ vulnerability to the health impacts of climate change may reflect local governments’ tendency to view adaptation through an emergency response lens (Schlosberg, Collins, and Niemeyer Citation2017). The lack of research about which adaptation strategies have been effective at reducing vulnerability may also help explain this uneven attention to justice-related adaptation projects in some sectors over others (see related work-Hansen, Braddock, and Rudnick Citation2023).

Reviewed plans rarely flagged potential negative impacts or maladaptive outcomes, such as gentrification or exclusion from government programmes. While the concept of maladaptation has been in use for many years (Barnett and O’Neill Citation2010), existing literature argues that the concept is difficult to assess in practice and few descriptions of maladaptive practices exist (Atteridge and Remling Citation2018; Juhola et al. Citation2016). However, failure to consider the drawbacks of potential adaptation strategies may result in initiatives that exclude or negatively impact individuals intended to benefit from these efforts (Anguelovski, Connolly, and Brand Citation2018).

Reviewed plans also focused more on expanding existing programmes or enhancing access to existing infrastructure, rather than developing new services or broader policy changes. These types of distributional justice initiatives, like expanding energy efficiency programmes, could be considered “resistance” or “resilience” strategies that aim to improve existing governance practices (Pelling Citation2010). The broader adaptation literature increasingly calls for employing a continuum of adaptation actions, ranging from incremental actions that address immediate needs to transformative initiatives that address the root causes of injustices, such as policies that address food insecurity or promote sustainable, affordable housing (Pelling, O’Brien, and Matyas Citation2015; Shi and Moser Citation2021; Westman and Castán Broto Citation2021). While reviewed plans did not commonly focus on root causes, many of the described initiatives () could certainly lead to longer-term impacts through infrastructural improvement, capacity-building, and enhanced quality of life for marginalised groups. For example, increased tree canopy and infrastructure upgrades can diminish long-term energy demands and shift social contexts (Chu et al. Citation2019). In each case, greater attention to how planned initiatives may change neighbourhoods, communities, and choices for marginalised groups, including ongoing monitoring of such impacts, could enhance distributional justice (Anguelovski, Connolly, and Brand Citation2018; Pelling, O’Brien, and Matyas Citation2015). This could also be supported through more holistic climate vulnerability assessments that explore interactions with other exiting stressors or scenario planning approaches.

Procedural justice: fostering responsive and inclusive processes

Only 22 plans explicitly acknowledged marginalised groups’ involvement in plan development or implementation. While local governments may have engaged in more robust planning processes that were not described in these documents, our results align with findings from similar studies that demonstrate an increased focus on advancing justice through outcomes, rather than within the processes themselves (Chu and Cannon Citation2021; Fitzgibbons and Mitchell Citation2019; Meerow, Pajouhesh, and Miller Citation2019). This lack of documentation may reflect a tension between the urgent need to adapt and the resource-intensive and time-demanding processes that are often needed to facilitate inclusive planning (Byskov et al. Citation2021; Healey Citation2020; Innes and Booher Citation2004). These processes require patience, empathy, and time to overcome power dynamics, build trust, and develop shared understandings between community members and local government (Ansell and Gash Citation2008). These elements can often feel at odds with the bureaucratic processes of governments (Hoover and Stern Citation2014) and the mounting impacts of climate change. Municipalities may also feel pressure to expedite these processes to ensure marginalised residents are prepared for the next climate-related event.

A vast body of research highlights the importance of trust-building and the value of incorporating and empowering diverse voices and perspectives in community planning and other forms of collective responses to environmental challenges (e.g. Phadke, Manning, and Burlager Citation2015; Schrock, Horst, and Ock Citation2022; Stern and Coleman Citation2015). Documenting these processes can signal receptiveness and care for diverse stakeholders, demonstrate governmental responsiveness, and provide a basis for ongoing accountability to community concerns (Hoover and Stern Citation2014; Innes and Booher Citation2004; Stern Citation2018). To offset the urgent need to adapt, municipalities may have to balance devoting energy towards inclusive planning processes and long-term engagement, while moving projects forward incrementally and transformationally.

Stakeholder advisory boards/committees are one strategy to involve community members in more long-term, robust engagement to address environmental challenges. Several challenges exist with this approach, as it may be difficult to initiate the process due to existing distrust or conflict, select individuals that represent the interests of these marginalised groups, and ensure the wider community is aware of the planning process (Lynn and Busenberg Citation1995). Schrock, Horst, and Ock (Citation2022) spoke with government officials and community members (some members of marginalised groups) involved in Portland’s Equity Working Group (OR) to understand how the group advanced justice in the city’s Climate Action Plan Update. Participants emphasised that the committee ensured equity was considered in proposed actions. More importantly, they felt that the process enhanced feelings of efficacy, empowering them to act (Schrock, Horst, and Ock Citation2022). However, participants also noted that the plan stalled during implementation and relationships between government officials and community members dissolved when officials prioritised other work. Their findings highlight the value in these types of initiatives but demonstrate that engagement may need to be viewed as a long-term partnership (Schrock, Horst, and Ock Citation2022). Future research could seek to understand how inclusive planning processes influence how justice is addressed during implementation.

Operationalising climate justice strategies

While plans discussed some details about how they intended to implement adaptation strategies, they mainly described which organisations would be involved and less commonly outlined other concrete details (e.g. funding for projects, potential locations, existing tools/programmes that could be used, or specific steps for implementation). Fewer plans described details about how they intended to evaluate how strategies impact marginalised groups. Evaluations of similar plans have also noted a tendency toward the inclusion of broad strategies with few specifics about implementation (Angelo et al. Citation2022; Hess and McKane Citation2021; Mullenbach and Wilhelm Stanis Citation2024). We also noted fewer details about marginalised groups included within implementation components of the review plans, with youth, low-income individual, and non-English speakers those most commonly noted (see Supplementary Material). Some of these groups may be easier to engage with than others, but it is also possible that some groups acted as proxies for others that weren’t explicitly noted (Brinkley and Wagner Citation2024), reflecting the intersectional and overlapping nature of marginalised groups’ identities (Kaijser and Kronsell Citation2014).

Climate plans are often viewed as strategic documents for how local governments intend to address climate impacts (Long and Rice Citation2019; Measham et al. Citation2011). Some argue that strategic plans should include few details about the specifics of implementation to encourage creativity as conditions change (Miller and Cardinal Citation1994; Mintzberg Citation1990). Others advocate for more details to hold governments accountable and increase the likelihood actions will be implemented (Meerow, Pajouhesh, and Miller Citation2019; Stults and Woodruff Citation2017). Threading the needle between these competing challenges might require thinking about which procedures or principles should be established ahead of time, and which should be left open and flexible. These decisions may be context-specific. For example, with widespread agreement on clear goals and ample resources and commitment for achieving them, fewer implementation details can encourage creativity and responsiveness to changing conditions. In areas with less agreement and commitment, more concrete steps can enhance accountability and the likelihood of action (Wilson Citation1989). Existing literature suggests that certain implementation details (e.g. identifying lead organisations, partners, available resources, and timelines) may consistently help move plans toward action, while avoiding pre-determined actions that might not adequately fit the context as conditions change (Bryson Citation2018; Lee, McGuire, and Kim Citation2018). Theory also suggests that establishing clear, shared criteria among relevant entities at the start of collaborative processes can inform how projects are adjusted and enhance trust moving forward (Fisher, Ury, and Patton Citation2011; Stern and Coleman Citation2015). It was beyond the scope of this study to understand whether plans with implementation considerations and monitoring were associated with advancing justice through implementation; future research is needed to explore the link between more detailed plans and outcomes.

Study limitations

This study has several limitations that illuminate additional opportunities for future research. It is important to acknowledge that having no adaptation plan or proposed actions can lead to injustices being continued or deepened as society is affected by climate change. Our sample only represents a segment of planning documents with content relevant to climate adaptation and those posted by communities that have made their plans publicly available online. Instead of creating standalone climate plans, some local governments mainstream climate adaptation efforts into other community plans, like general plans, comprehensive plans, or hazard mitigation plans (Matos et al. Citation2023; Reckien et al. Citation2019). Future research could conduct a more exhaustive review of how justice considerations compare across standalone climate plans and more general planning approaches. Our research provides a snapshot of how communities are planning for climate adaptation by reviewing one piece of larger adaptation processes. Future research could better explore other facets of adaptation planning in US or other communities to understand how these plans translate into action and who benefits from these initiatives.

Conclusion

Climate adaptation plans provide one avenue through which local governments can consider justice as they adapt to climate impacts. Our findings summarise a range of ways local municipalities in the US have addressed recognitional, distributional, and procedural justice. We found that recognitional justice in the plans largely focused on identifying marginalised groups and rarely addressed historical causes of marginalisation. Distributional justice was addressed primarily through expanding existing programmes across multiple sectors, with little attention given to the potential unintended consequences of these initiatives. Procedural justice concerns were less commonly documented in the plans, primarily including descriptions of public involvement in planning processes. Implementation details and specifics about monitoring and evaluation were infrequently included. Overall, the study reveals broadscale attention to the concerns of marginalised groups in climate adaptation planning in the US. However, procedural justice may be lagging behind recognitional justice. Future research is necessary to determine the longer-term results of climate adaptation planning process with regard to implementation and distributive justice outcomes.

CLOE2386964_Supplementary material.docx

Download MS Word (42.8 KB)Acknowledgements

This material is supported by the National Science Foundation under award numbers 1810851 and 1811534. We’d also like to thank Barb Belsito and Tyler Whitford for their help in piloting the coding scheme.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the results of this study are publicly available at the Harvard Dataverse through this link: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/PRKACP

.Additional information

Funding

References

- Aaronson, Daniel, Daniel Hartley, and Bhashkar Mazumder. 2021. “The Effects of the 1930s HOLC ‘Redlining’ Maps.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 13 (4): 355–392. https://doi.org/10.1257/pol.20190414

- Adger, W. Neil. 2016. “Place, Well-being, and Fairness Shape Priorities for Adaptation to Climate Change.” Global Environmental Change 38:A1–A3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2016.03.009

- Adger, W. Neil, and P. Mick Kelly. 1999. “Social Vulnerability to Climate Change and the Architecture of Entitlements.” Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change 4 (3/4): 253–266. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009601904210

- Angelo, Hillary, Key MacFarlane, James Sirigotis, and Adam Millard-Ball. 2022. “Missing the Housing for the Trees: Equity in Urban Climate Planning.” Journal of Planning Education and Research, 0739456X211072527.

- Anguelovski, Isabelle, James Connolly, and Anna Livia Brand. 2018. “From Landscapes of Utopia to the Margins of the Green Urban Life: For Whom is the New Green City?” City 22 (3): 417–436. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2018.1473126

- Anguelovski, Isabelle, Linda Shi, Eric Chu, Daniel Gallagher, Kian Goh, Zachary Lamb, Kara Reeve, and Hannah Teicher. 2016. “Equity Impacts of Urban Land Use Planning for Climate Adaptation: Critical Perspectives from the Global North and South.” Journal of Planning Education and Research 36 (3): 333–348. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X16645166

- Ansell, Chris, and Alison Gash. 2008. “Collaborative Governance in Theory and Practice.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 18 (4): 543–571. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mum032

- Atteridge, Aaron, and Elise Remling. 2018. “Is Adaptation Reducing Vulnerability or Redistributing It?” Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 9 (1): e500. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.500

- Baker, Ingrid, Ann Peterson, Greg Brown, and Clive McAlpine. 2012. “Local Government Response to the Impacts of Climate Change: An Evaluation of Local Climate Adaptation Plans.” Landscape and Urban Planning 107 (2): 127–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2012.05.009

- Barnett, Jon, and Saffron O’Neill. 2010. “Maladaptation.” Global Environmental Change 20 (2): 211–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2009.11.004

- Bassett, Ellen, and Vivek Shandas. 2010. “Innovation and Climate Action Planning: Perspectives from Municipal Plans.” Journal of the American Planning Association 76 (4): 435–450. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2010.509703

- Berke, Philip, and Ward Lyles. 2013. “Public Risks and the Challenges to Climate-change Adaptation: A Proposed Framework for Planning in the age of Uncertainty.” Cityscape (Washington, D C), 181–208.

- Berke, Philip, Gavin Smith, and Ward Lyles. 2012. “Planning for Resiliency: Evaluation of State Hazard Mitigation Plans under the Disaster Mitigation Act.” Natural Hazards Review 13 (2): 139–149. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)NH.1527-6996.0000063

- Brinkley, Catherine, and Jenny Wagner. 2024. “Who is Planning for Environmental Justice—And How?” Journal of the American Planning Association, 90 (1): 63–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2022.2118155

- Brousseau, Jennifer J., Marc J. Stern, and Lara J. Hansen. 2024. “Unequal considerations of justice in municipal adaptation planning: an assessment of US climate plans over time and by context.” Local Environment 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2024.2368532

- Bryson, John M. 2018. Strategic Planning for Public and Nonprofit Organisations: A Guide to Strengthening and Sustaining Organisational Achievement. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons.

- Bulkeley, Harriet, JoAnn Carmin, Vanesa Castán Broto, Gareth A. S. Edwards, and Sara Fuller. 2013. “Climate Justice and Global Cities: Mapping the Emerging Discourses.” Global Environmental Change 23 (5): 914–925. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.05.010

- Bulkeley, Harriet, Gareth A. S. Edwards, and Sara Fuller. 2014. “Contesting Climate Justice in the City: Examining Politics and Practice in Urban Climate Change Experiments.” Global Environmental Change 25:31–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2014.01.009

- Byskov, Morten Fibieger, Keith Hyams, Poshendra Satyal, Isabelle Anguelovski, Lisa Benjamin, Sophie Blackburn, Maud Borie, et al. 2021. “An Agenda for Ethics and Justice in Adaptation to Climate Change.” Climate and Development 13 (1): 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2019.1700774

- Cannon, Clare, Eric Chu, Asiya Natekal, and Gemma Waaland. 2023. “Translating and Embedding Equity-thinking into Climate Adaptation: An Analysis of US Cities.” Regional Environmental Change 23 (1): 30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-023-02025-2

- Castán Broto, Vanesa, Bridget Oballa, and Paulo Junior. 2013. “Governing Climate Change for a Just City: Challenges and Lessons from Maputo, Mozambique.” Local Environment 18 (6): 678–704. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2013.801573

- Chu, Eric, Anna Brown, Kavya Michael, Jillian Du, Shuaib Lwasa, and Anjali Mahendra. 2019. “Unlocking the Potential for Transformative Climate Adaptation in Cities.” Background Paper Prepared for the Global Commission on Adaptation, Washington DC and Rotterdam.

- Chu, Eric K., and Clare E. B. Cannon. 2021. “Equity, Inclusion, and Justice as Criteria for Decision-Making on Climate Adaptation in Cities.” Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 51:85–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2021.02.009

- Chu, Eric, and Kavya Michael. 2019. “Recognition in Urban Climate Justice: Marginality and Exclusion of Migrants in Indian Cities.” Environment and Urbanisation 31 (1): 139–156. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247818814449

- Diezmartínez, Claudia V., and Anne G. Short Gianotti. 2022. “US Cities Increasingly Integrate Justice into Climate Planning and Create Policy Tools for Climate Justice.” Nature Communications 13 (1): 5763. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-33392-9

- EcoAdapt. 2022. “Climate Adaptation Knowledge Exchange (CAKE).” https://www.cakex.org/.

- Fiack, Duran, Jeremy Cumberbatch, Michael Sutherland, and Nadine Zerphey. 2021. “Sustainable Adaptation: Social Equity and Local Climate Adaptation Planning in US Cities.” Cities 115:103235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2021.103235

- Finn, Donovan, and Lynn McCormick. 2011. “Urban Climate Change Plans: How Holistic?” Local Environment 16 (4): 397–416. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2011.579091

- Fisher, Roger, William L. Ury, and Bruce Patton. 2011. Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In. New York: Penguin.

- Fitzgibbons, Joanne, and Carrie L. Mitchell. 2019. “Just Urban Futures? Exploring Equity in “100 Resilient Cities.” World Development 122:648–659. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.06.021

- Georgetown Climate Center. 2022a. Adaptation Clearinghouse. https://www.adaptationclearinghouse.org/.

- Georgetown Climate Center. 2022b. State Adaptation Progress Tracker. https://www.georgetownclimate.org/adaptation/plans.html.

- Gillespie, Nicole, and Graham Dietz. 2009. “Trust Repair After an Organisation-level Failure.” Academy of Management Review 34 (1): 127–145. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2009.35713319

- Guyadeen, Dave, Jason Thistlethwaite, and Daniel Henstra. 2019. “Evaluating the Quality of Municipal Climate Change Plans in Canada.” Climatic Change 152 (1): 121–143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-018-2312-1

- Hansen, L. J., K. N. Braddock, and D. A. Rudnick. 2023. “A Good Idea or Just an Idea: Which Adaptation Strategies for Conservation are Tested?” Biological Conservation 286:110276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2023.110276

- Healey, Patsy. 2020. Collaborative Planning: Shaping Places in Fragmented Societies. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Hess, David J., and Rachel G. McKane. 2021. “Making Sustainability Plans More Equitable: An Analysis of 50 US Cities.” Local Environment 26 (4): 461–476. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2021.1892047

- Hoffman, Jeremy S., Vivek Shandas, and Nicholas Pendleton. 2020. “The Effects of Historical Housing Policies on Resident Exposure to Intra-urban Heat: A Study of 108 US Urban Areas.” Climate 8 (1): 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli8010012

- Holland, Breena. 2017. “Procedural Justice in Local Climate Adaptation: Political Capabilities and Transformational Change.” Environmental Politics 26 (3): 391–412. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2017.1287625

- Hoover, Katie, and Marc J. Stern. 2014. “Team Leaders’ Perceptions of Public Influence in the US Forest Service: Exploring the Difference between Doing and Using Public Involvement.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 57 (2): 157–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2012.756807

- Horney, Jennifer, Mai Nguyen, David Salvesen, Caroline Dwyer, John Cooper, and Philip Berke. 2017. “Assessing the Quality of Rural Hazard Mitigation Plans in the Southeastern United States.” Journal of Planning Education and Research 37 (1): 56–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X16628605

- Hughes, Sara. 2015. “A Meta-analysis of Urban Climate Change Adaptation Planning in the US.” Urban Climate 14:17–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.uclim.2015.06.003

- Innes, Judith E., and David E. Booher. 2004. “Reframing Public Participation: Strategies for the 21st Century.” Planning Theory & Practice 5 (4): 419–436. https://doi.org/10.1080/1464935042000293170

- Juhola, Sirkku, Erik Glaas, Björn-Ola Linnér, and Tina-Simone Neset. 2016. “Redefining Maladaptation.” Environmental Science and Policy 55: 135–140.

- Kaijser, Anna, and Annica Kronsell. 2014. “Climate Change Through the Lens of Intersectionality.” Environmental Politics 23 (3): 417–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2013.835203

- Kania, John, Junious Williams, Paul Schmitz, Sheri Brady, Mark Kramer, and Jennifer Splansky Juster. 2022. “Centering Equity in Collective Impact.” Stanford Social Innovation Review 20 (1): 38–45.

- Kates, Robert W., William R. Travis, and Thomas J. Wilbanks. 2012. “Transformational Adaptation When Incremental Adaptations to Climate Change are Insufficient.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109 (19): 7156–7161. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1115521109

- Klinsky, Sonja, Timmons Roberts, Saleemul Huq, Chukwumerije Okereke, Peter Newell, Peter Dauvergne, Karen O’Brien, et al. 2017. “Why Equity is Fundamental in Climate Change Policy Research.” Global Environmental Change 44:170–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2016.08.002

- Lee, David, Michael McGuire, and Jong Ho Kim. 2018. “Collaboration, Strategic Plans, and Government Performance: The Case of Efforts to Reduce Homelessness.” Public Management Review 20 (3): 360–376. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2017.1285113

- Li, Chaosu, and Yan Song. 2016. “Government Response to Climate Change in China: A Study of Provincial and Municipal Plans.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 59 (9): 1679–1710. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2015.1085840

- Long, Joshua, and Jennifer L. Rice. 2019. “From Sustainable Urbanism to Climate Urbanism.” Urban Studies 56 (5): 992–1008. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098018770846

- Lynn, Frances M., and George J. Busenberg. 1995. “Citisen Advisory Committees and Environmental Policy: What We Know, What's Left to Discover.” Risk Analysis 15 (2): 147–162. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.1995.tb00309.x

- Malloy, Jeffrey T., and Catherine M. Ashcraft. 2020. “A Framework for Implementing Socially Just Climate Adaptation.” Climatic Change 160 (1): 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-020-02705-6

- Matos, Melina, Philip Gilbertson, Sierra Woodruff, Sara Meerow, Malini Roy, and Bryce Hannibal. 2023. “Comparing Hazard Mitigation and Climate Change Adaptation Planning Approaches.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 66 (14): 2922–2942.

- Measham, Thomas G., Benjamin L. Preston, Timothy F. Smith, Cassandra Brooke, Russell Gorddard, Geoff Withycombe, and Craig Morrison. 2011. “Adapting to Climate Change Through Local Municipal Planning: Barriers and Challenges.” Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change 16 (8): 889–909. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-011-9301-2

- Meerow, Sara, Pani Pajouhesh, and Thaddeus R. Miller. 2019. “Social Equity in Urban Resilience Planning.” Local Environment 24 (9): 793–808. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2019.1645103

- Miller, C. Chet, and Laura B. Cardinal. 1994. “Strategic Planning and Firm Performance: A Synthesis of More Than Two Decades of Research.” Academy of Management Journal 37 (6): 1649–1665. https://doi.org/10.2307/256804

- Mintzberg, Henry. 1990. “The Design School: Reconsidering the Basic Premises of Strategic Management.” Strategic Management Journal 11 (3): 171–195. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250110302

- Mullenbach, Lauren E., and Sonja A. Wilhelm Stanis. 2024. “Climate Change Adaptation Plans: Inclusion of Health, Equity, and Green Space.” Journal of Urban Affairs, 46 (4): 701–716.

- NCES (National Center for Eduation Statistics). 2021. NCES Locale Lookup. https://nces.ed.gov/programmes/maped/LocaleLookup/.

- Paavola, Jouni, and W. Neil Adger. 2006. “Fair Adaptation to Climate Change.” Ecological Economics 56 (4): 594–609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2005.03.015

- Pelling, Mark. 2010. Adaptation to Climate Change: From Resilience to Transformation. Oxfordshire: Routledge.

- Pelling, Mark, Karen O’Brien, and David Matyas. 2015. “Adaptation and Transformation.” Climatic Change 133 (1): 113–127. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-014-1303-0

- Peterson St-Laurent, Guillaume, Lauren E. Oakes, Molly Cross, and Shannon Hagerman. 2021. “R–R–T (Resistance–Resilience–Transformation) Typology Reveals Differential Conservation Approaches across Ecosystems and Time.” Communications Biology 4 (1): 39. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-020-01556-2

- Phadke, Roopali, Christie Manning, and Samantha Burlager. 2015. “Making it Personal: Diversity and Deliberation in Climate Adaptation Planning.” Climate Risk Management 9:62–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crm.2015.06.005

- Pörtner, Hans O., Debra C. Roberts, Helen Adams, Carolina Adler, Paulina Aldunce, Elham Ali, Rawshan Ara Begum, et al. 2022. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Cambridge and New York: IPCC.

- Preston, Benjamin L., Richard M. Westaway, and Emma J. Yuen. 2011. “Climate Adaptation Planning in Practice: An Evaluation of Adaptation Plans from Three Developed Nations.” Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change 16 (4): 407–438. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-010-9270-x

- Rawls, John. 1971. “A Theory of Justice.” Cambridge (Mass.).

- Reckien, Diana, Shuaib Lwasa, David Satterthwaite, Darryn McEvoy, Felix Creutzig, Mark Montgomery, and Daniel Schensul. 2018. “Equity, Environmental Justice, and Urban Climate Change.”

- Reckien, Diana, Monika Salvia, Filomena Pietrapertosa, Sofia G. Simoes, Marta Olazabal, S. De Gregorio Hurtado, Davide Geneletti, et al. 2019. “Dedicated versus Mainstreaming Approaches in Local Climate Plans in Europe.” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 112:948–959. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2019.05.014.

- Schlosberg, David. 2004. “Reconceiving Environmental Justice: Global Movements and Political Theories.” Environmental Politics 13 (3): 517–540. https://doi.org/10.1080/0964401042000229025

- Schlosberg, David. 2007. Defining Environmental Justice: Theories, Movements, and Nature. Oxford: OUP.

- Schlosberg, David, and Lisette B. Collins. 2014. “From Environmental to Climate Justice: Climate Change and the Discourse of Environmental Justice.” Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change 5 (3): 359–374. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.275

- Schlosberg, David, Lisette B. Collins, and Simon Niemeyer. 2017. “Adaptation Policy and Community Discourse: Risk, Vulnerability, and Just Transformation.” Environmental Politics 26 (3): 413–437. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2017.1287628

- Schrock, Greg, Megan Horst, and YunJae Ock. 2022. “Incorporating an Equity Lens into Local Climate Action Planning in Portland, Oregon.” In Justice in Climate Action Planning, edited by Brian Peterson and Hélène B. Ducros, 79–96. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Shi, Linda, Eric Chu, Isabelle Anguelovski, Alexander Aylett, Jessica Debats, Kian Goh, Todd Schenk, et al. 2016. “Roadmap Towards Justice in Urban Climate Adaptation Research.” Nature Climate Change 6 (2): 131–137. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2841.

- Shi, Linda, and Susanne Moser. 2021. “Transformative Climate Adaptation in the United States: Trends and Prospects.” Science 372 (6549): eabc8054. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abc8054

- Sovacool, Benjamin K., Björn-Ola Linnér, and Michael E. Goodsite. 2015. “The Political Economy of Climate Adaptation.” Nature Climate Change 5 (7): 616–618. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2665

- Stein, Bruce A., Amanda Staudt, Molly S. Cross, Natalie S. Dubois, Carolyn Enquist, Roger Griffis, Lara J. Hansen, et al. 2013. “Preparing for and Managing Change: Climate Adaptation for Biodiversity and Ecosystems.” Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 11 (9): 502–510. https://doi.org/10.1890/120277.

- Stern, Marc J. 2018. Social Science Theory for Environmental Sustainability: A Practical Guide. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Stern, Marc J., and Timothy D. Baird. 2015. “Trust Ecology and the Resilience of Natural Resource Management Institutions.” Ecology and Society 20 (2).

- Stern, Marc J., J. Brousseau, C. O’Brien, K. Hurst, and L. J. Hansen. 2020. “Climate Adaptation Workshop Delphi Study Report: Facilitators’ Viewpoints on Effective Practices.” Virginia Tech: Blacksburg, VA, USA.

- Stern, Marc J., and Kimberly J. Coleman. 2015. “The Multidimensionality of Trust: Applications in Collaborative Natural Resource Management.” Society & Natural Resources 28 (2): 117–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2014.945062

- Stults, Missy, and Sierra C. Woodruff. 2017. “Looking under the Hood of Local Adaptation Plans: Shedding Light on the Actions Prioritised to Build Local Resilience to Climate Change.” Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change 22 (8): 1249–1279. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-016-9725-9

- Swanson, Kayleigh. 2021. “Equity in Urban Climate Change Adaptation Planning: A Review of Research.” Urban Planning 6 (4): 287–297. https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v6i4.4399

- van den Berg, Hanne J., and Jesse M. Keenan. 2019. “Dynamic Vulnerability in the Pursuit of Just Adaptation Processes: A Boston Case Study.” Environmental Science & Policy 94:90–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2018.12.015

- Westman, Linda, and Vanesa Castán Broto. 2021. “Transcending Existing Paradigms: The Quest for Justice in Urban Climate Change Planning.” Local Environment 26 (5): 536–541. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2021.1916903

- White-Newsome, Jalonne L., Phyllis Meadows, and Chris Kabel. 2018. “Bridging Climate, Health, and Equity: A Growing Imperative.” American Journal of Public Health 108 (S2): S72–S73. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2017.304133

- Wilson, James Q. 1989. Bureaucracy: What Government Agencies do and Why They do It. New York: Basic Books.

- Woodruff, Sierra C., and Missy Stults. 2016. “Numerous Strategies But Limited Implementation Guidance in US Local Adaptation Plans.” Nature Climate Change 6 (8): 796–802. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate3012

- Zoll, Deidre. 2022. “We can’t Address What We don’t Acknowledge: Confronting Racism in Adaptation Plans.” In Justice in Climate Action Planning, edited by Brian Peterson and Hélène B. Ducros, 3–23. Cham: Springer International Publishing.