ABSTRACT

Cash and voucher assistance is an efficient way to deliver assistance in emergency settings, and evidence demonstrates that cash programmes have consistent positive impacts on food security and other health and economic outcomes in these contexts. Nevertheless, while evidence from development settings shows that cash has the potential to reduce intimate partner violence and increase empowerment for women and girls, there is a dearth of rigorous evidence from acute humanitarian settings. In response to this evidence gap, the International Rescue Committee conducted an evaluation of a cash programme in Raqqa Governorate, Syria. The aim was to examine the effect of a cash for basic needs programme on outcomes of violence against women, and women’s empowerment. This article draws on qualitative data from interviews with 40 women at the end of the cash programme. It offers evidence of potential increased tension and abuse within both the community and the household for some women whose families received cash, as well as potential increased social protection through repayment of debts and economic independence for others. Both negative and positive effects could be seen. While the objective of the cash programme was not to influence underlying power dynamics, this research shows it is necessary to integrate gender-sensitive approaches into programme design and monitoring to reduce risk to women of diverse identities.

L’aide en espèces et sous forme de bons d’achat est une manière efficace d’apporter une assistance dans les situations d’urgence, et il y a des données probantes qui montrent que les programmes de transferts d’espèces ont constamment des impacts positifs sur la sécurité alimentaire et d’autres résultats sanitaires et économiques dans ces contextes. Néanmoins, si les données émanant des contextes de développement montrent en effet que les transferts d’espèces ont le potentiel de réduire la violence exercée par un partenaire intime et d’accroître l’autonomisation pour les femmes et les filles, on manque de données probantes rigoureuses provenant de contextes humanitaires aigus. Face à cette pénurie de données, l’International Rescue Committee a mené une évaluation d’un programme de transfert d’espèces dans le gouvernorat de Raqqa, en Syrie. L’objectif était d’examiner l’effet d’un programme d’espèces pour pourvoir aux besoins fondamentaux sur les résultats en matière de violence à l’égard des femmes et d’autonomisation des femmes. Ces recherches, qui font l’objet d’une discussion ici, ont donné lieu à des données probantes indiquant une intensification des tensions et des abus au sein de la communauté et du ménage pour certaines femmes dont la famille a reçu de l’argent, ainsi qu’une protection sociale accrue potentielle à travers le remboursement des dettes et l’indépendance économique pour d’autres. Des effets négatifs et positifs ont été constatés. Si l’objectif du programme de transfert d’espèces ne consistait pas à influencer la dynamique de pouvoir sous-jacente, ces données montrent qu’il est néanmoins nécessaire d’intégrer les approches sensibles au genre dans la conception et le suivi des programmes afin de réduire les risques pour les femmes de diverses identités.

La asistencia brindada mediante el reparto de dinero en efectivo o cupones constituye una forma eficiente de proveer ayuda en situaciones de emergencia. La evidencia demuestra que los programas orientados a repartir dinero en efectivo tienen un impacto positivo y constante en la seguridad alimentaria, así como en otros aspectos económicos y de salud en estos contextos. Sin embargo, si bien la evidencia procedente de entornos en vías de desarrollo indica que el efectivo tiene potencial para reducir la violencia de la pareja íntima e incrementar el empoderamiento de mujeres y niñas, existe escasez de pruebas rigurosas derivadas de los entornos humanitarios agudos. En respuesta a esta brecha en la evidencia, el Comité Internacional de Rescate evaluó un programa de reparto de efectivo en la Gobernación de Al Raqa, Siria; el objetivo de esta evaluación fue examinar el efecto que conlleva la distribución de dinero en efectivo para subsanar necesidades básicas en la violencia contra las mujeres y en su empoderamiento. La investigación analizada en el presente artículo ofrece hallazgos en el sentido de un posible aumento de la tensión y el abuso en la comunidad y el hogar de algunas mujeres cuyas familias recibieron dinero en efectivo; sin embargo, en el caso de otras mujeres, el mismo programa significó un aumento de la protección social, ya que les permitió pagar deudas y favoreció su independencia económica. Es decir, pudieron observarse tanto efectos negativos como positivos. Si bien el objetivo del programa de distribución efectivo no era influir en las dinámicas de poder subyacentes, la información generada muestra que, para reducir el riesgo que corren mujeres de identidades diversas, en el diseño y el monitoreo del programa es necesario integrar enfoques sensibles al género.

Introduction

Cash assistance has become one of the most common means of delivering assistance in humanitarian emergencies across sectors. Research in various humanitarian settings suggests that cash assistance may improve food security and help households meet their basic needs (Baily and Hedlund Citation2012; Doocy and Tappis Citation2017; Kabeer et al. Citation2012). There is also strong evidence that cash can be used to improve health and other measures of wellbeing among populations affected by crises, though effectiveness is highly dependent on the programme design (transfer value, frequency, duration, and timing) (Harvey and Pavanello Citation2018). But despite the widespread use of cash assistance, there is little evidence from acute emergency settings, such as those grappling with recent displacement or natural disaster, on how cash might improve outcomes for women and girls or how it might put them at further risk of gender-based violence (GBV). This is particularly important in humanitarian settings, as displaced women and girls are at an increased risk of harm to their physical and mental health and exposure to violence, including intimate partner violence (IPV) (Stark and Ager Citation2011).

A recent review of evidence from development settings demonstrates that cash assistance can reduce IPV by reducing household tension and increasing women’s decision-making power (Buller et al. Citation2018). Additionally, cash has been shown to have positive effects on outcomes of empowerment when targeted to women and girls, such as economic access, monetary poverty, education, health, and nutrition (Dickson and Bangpan Citation2012; Gibbs et al. Citation2017; Hagen-Zanker et al. Citation2017). For households with children, studies have shown that conditional cash transfers can both delay marriage for adolescent girls and promote educational retention (Baird et al. Citation2013; Dickson and Bangpan Citation2012; Kabeer et al. Citation2012). However, this research is generally from longer-term social protection programmes, and the amount and duration of these cash interventions are quite different from those in humanitarian settings.

The limited evidence from humanitarian settings suggests that cash has largely positive effects on GBV, though results are mixed (Cross et al. Citation2018). It also shows that cash programmes have the potential to reduce a household’s reliance on negative coping, including taking children out of school, reducing food consumption, depleting savings, or selling assets (Berg and Seferis Citation2015). Nevertheless, findings from programme evaluations in humanitarian contexts reveal that cash assistance can expose beneficiaries to violence and other unintended risks. Cash recipients may experience increased household and community tension, increased family violence,Footnote1 and/or exposure to theft and stigma, as well as other documented risks (Freccero et al. Citation2019; O’Keefe Citation2016). While cash assistance is an extremely beneficial modality for providing aid in humanitarian settings, a more comprehensive understanding is needed around how cash programmes might improve violence and empowerment outcomes for women and girls, or how it might expose them to further risk.

To respond to this gap in evidence and increase our understanding of the impacts of cash assistance on violence and empowerment outcomes for women and girls, the International Rescue Committee (IRC) conducted a mixed-methods assessment of an emergency cash assistance programme in north-east Syria. The study ran between March and August 2018. The primary purpose of the cash programme was to help households meet their basic needs. It was part of a humanitarian response targeting areas where the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS)Footnote2 had recently withdrawn, and that had received new influxes of internally displaced persons (IDPs) fleeing conflict in Raqqa City. The programme included a three-month, multi-round unconditional cash transfer for non-food items targeted at heads of household, regardless of sex.Footnote3 It was chosen for the study as this type of cash transfer is a common way of delivering cash in the humanitarian field.Footnote4 This cash programme had no complementary programming addressing gender norms, nor was the purpose of the programme intended to address social norms.

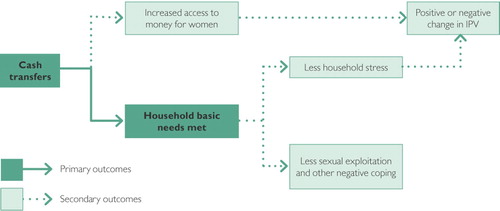

The theory of change informing the study is summarised in .

Figure 1. Theory of change for a cash for basic needs programme on outcomes of violence and empowerment. Source: Falb et al. (Citation2019).

The study aimed to understand the experience of women whose families participated in an IRC cash programme in Raqqa Governorate, Syria, before, during, and after the programme took place. It drew on quantitative baseline and endline surveys, and on additional qualitative in-depth interviews. These examined the potential effect of cash transfers on violence outcomes and other measures of wellbeing. To our knowledge, this evaluation is the first systematic mixed-methods research conducted in recent years in Raqqa Governorate. Full details of the research methods and process are available in the research report (Falb et al. Citation2019).

This article draws on the qualitative in-depth interviews conducted among 40 women at the end of the programme. The qualitative interviews aimed to capture both expected and unexpected outcomes of the programme. This article particularly focuses on the positive or negative unintended outcomes that women perceived had occurred during their household’s participation in the cash programme, and the intersecting social factors that influenced them. In the next section, we outline the details of the study, prior to sharing some of our key findings.

The research: context and methods

Study setting

Raqqa Governorate has experienced overlapping conflict since 2011 when civil conflict erupted, and ISIS began seizing control of land in 2013. Seven years of military conflict and ISIS occupation left the population exposed to extreme levels of violence and economic hardship, with little access to aid. Despite the restoration of relative peace to the region after the withdrawal of ISIS in late 2017, communities continue to suffer from high levels of displacement, lack of livelihoods, and physical and mental distress (UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs Citation2018).

Methodology

Study participants were drawn from households in northern Raqqa Governorate that had been selected to receive cash assistance through an existing IRC programme. Households with at least one woman aged 18–59 were invited to participate in the study. A total of 456 women were surveyed before and after their households had received three cash payments over a three-month period. A sub-sample of 40 women were then selected from the participants to do qualitative interviews ().

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of the respondents who participated in the qualitative interviews (n = 40 women).

We selected women who met specific criteria, including female-headed households, age, disability, displacement status, and experience of violence as reported during the baseline survey. Interviews were conducted with an open-ended interview guide, which was supplemented with a visual timeline technique to ask women about their experiences during the programme. The timeline guided women to describe their lives before, during, and after the conflict, and before, during, and after the cash programme. IRC research staff or GBV caseworkers not involved in the cash programme conducted interviews with each woman privately. Interviews were conducted with one interviewer and one note-taker, with the exception of those interviews that were conducted by staff who did not speak Arabic (six of 40 interviews), where a translator was also present.

Ethical concerns

All study procedures were carefully designed to protect participants from social risk and further harm. Before beginning the qualitative in-depth interview, separate oral consent was obtained by the facilitator. The consent forms included specific language to clarify that the women were still eligible to participate in the cash programme regardless of whether or not they participated in the evaluation study.Footnote5 All study participants were provided with information about IRC’s Women’s Protection and Empowerment (WPE) services that were made available to them and their community at the conclusion of the interview. Respondents who reported a recent history of violence or another acute need for psychosocial support were referred to an experienced WPE case manager who could conduct referrals to qualified mental health staff, as appropriate.

Data analysis

IRC researchers led the data analysis, supported by the Northeast Syria programme teams and key technical staff. Coding was used to identify emerging themes and patterns from the transcripts and photographs of the interactive timelines drawn by the interviewer. An initial coding structure was developed from the study’s theory of change, which hypothesised that while the purpose of the cash transfers is to help households meet their basic needs, the infusion of cash into a household might result in other influences on family dynamics and well-being. We examined the status of women before the start of the programme and whether the presence of cash might have influenced spending habits, decision-making, and relationships at the individual, household, and community levels over the three-month programme period. Additional codes were then developed as patterns emerged from the data. Data were coded using the qualitative analysis software Dedoose. Findings were validated in a workshop in Raqqa Governorate with IRC Northeast Syria team members.

Following the coding using the theory of change, we then used a second framework – the dynamic framework for social change (Cislaghi and Heise Citation2018) – to gain additional insights. This framework is an adaptation of the ecological model: that is, it shows how an individual is influenced by different personal and environmental factors within society. In particular, we focused on three levels of society in northern Raqqa: the individual, the household, and the community. We wanted to understand how gender and power dynamics might influence the unintended benefits or costs for women whose families received cash transfers within each of these societal levels. Cash coming into a household effects a change in the material domain, and this is iteratively linked to changes in the other domains. We used this framework to explore how power relations might affect women’s access to, and use of, cash, and how an infusion of cash into the household might affect power relations.

In our discussion of our findings in this article, we use quotations from participants to exemplify the patterns that are prominent in the analysis.

Our findings

Setting the stage: the situation of women in Raqqa before the cash programme

Respondents painted a vivid picture of the difficult situation that women and girls faced in Raqqa due to their low social status. Qualitative data revealed that women in the region were subject to overlapping unequal power dynamics that affected individuals differently depending on a number of factors, including their marital status and the composition of their household.

When sharing information about their lives before, during, and after the conflict, many women described experiences of violence and other forms of coercion and abuse from their husbands, families, and other community members. While several attributed a deterioration of their situation to the conflict, women’s accounts of their experiences demonstrated that violence against women and girls is an accepted norm that existed before the conflict’s escalation in the region.

Most married women perceived that their relationships with their husbands worsened in the aftermath of the conflict. They attributed this increased tension to conflict-related stress, such as increased financial stress or because their husbands were disabled by an injury and could no longer provide an income. In interviews, these situations were commonly marked by the violent reactions of their husbands. One married women shared her experience:

My husband lost his sight. … Our relationship is not good. He never hits me, but he gets angry sometimes and tells me to leave the house. … I know that he gets angry because of our bad financial situation.

In the public sphere, gender discrimination towards women also related to women’s marital status. This was particularly evident in the experiences of widowed or divorced women who lived and went out in public without a husband and described intense community stigma, monitoring, and policing of their movements as a result. A divorced female head of household stated:

When we first came to this neighbourhood, I used to go out and buy fabrics for my sister-in-law because she works as a tailor. People started gossiping about me, where I go every day, and what I am doing when I go out. They accuse me of doing bad things.

It was hard, even to throw away garbage I had to dress according to the dress code. I was once with my aunt and she wasn’t covering her eyes, and the HisbahFootnote6 took us, and because we were alone with no Mahram,Footnote7 my brother came. They whipped him and put him in a training about sharia.

Whenever I needed to go to the market or to see a doctor, I was forced to wait for someone of my family to go with me, because I’m a divorced woman, and I can’t go out alone … There is no movement, it feels like prison.

I feel so much suffering … The community has a very wrong understanding of dealing with a lonely woman.

The shopkeeper used to tell me that ‘you can take whatever you want’. He was nice with me because he wanted more, not because he felt sorry for me or because he was a good person, and he told me that he wanted something in return. This all happens to widows and divorced women.

I can’t go out with other men to bring money to my husband. He told me to do that; I didn’t accept. A man I know from the village offered me money in exchange for something. [She asked for a break, and collapsed in tears, and after five minutes, she continued.] My son is one year and half, he stayed with my sister when I went with the man.

The individual level: the influence of cash on stress, economic dependence, and self-efficacy

The majority of women in the interviews revealed the extent to which they were regularly suffering from stress, with many reporting that they were struggling to cope and were fearful of the future. While the purpose of the programme was not to improve mental health, women who were interviewed commonly expressed how receiving cash, even for a short period, helped to ease some of the stress and anxiety of trying to meet their family’s basic needs. A divorced female head of household stated that receiving the cash was ‘a mountain off my back’.

Women of different marital and household statuses described feeling humiliated when they were forced to rely on family members or neighbours for money or other resources, or when they had to incur debts to acquire food and other goods from the market. Several women stated that receiving the cash helped to relieve them of this sense of shame and burden to others. A married woman said:

I paid off debts. The cash helped me to save my dignity; I used to wear old clothes that others give me.

I used to rely on charity and on people, hoping that they would be good to me and help me with Zakat Al-Fitr,Footnote9 but now with the payments I get I am in charge again and I am able to buy clothes for my son. This money is very much appreciated. I feel confident, no one can force me to do anything. Having this money gave me confidence.

I felt like I was imprisoned and released, I was able to prepare the meal I wanted, I was relaxed.

This is the first time that I got my [own] money. I really needed this money. I felt that I owe no one and that I can do something. I felt important because I participated in the household expenses and I do not owe anyone for my daughter’s and my expenses.

I didn’t think yet what I’m going to do when the project ends. I’ll work in the field from the early morning to the evening, and I’ll get 500 liras. I will suffer and struggle again.

Now when I ask my parents for money, they do not help me as they used to, unlike before where they used to help me without me asking them to. It is a difficult situation.

Household: the influence of household power dynamics and gender relations on decision-making and use of cash

The cash programme was not intended to address social norms or power dynamics; nevertheless, several women perceived that the temporary economic relief might have briefly reduced tensions within the household.

When asked who made decisions around spending the cash, married women in the qualitative interviews largely perceived that decisions were made jointly with their husbands. However, the perception of joint decision-making was often overshadowed by preceding statements, which illustrated that the joint decision-making was tied with taking advice or instruction from their husband on how best to spend the cash. A married woman stated:

My husband and I [made decisions on how to spend the money] together, but out of respect I let my husband make the decision. He advised me … and he knows how to spend the money.

My husband decided, I didn’t see the money, I put nothing in my pocket. He makes all decisions; I have to take his opinion in everything.

I decided how to spend the cash … I bought my husband cigarettes, so he doesn’t get angry.

[Because of the cash] I felt strong, my relationship with my husband is good, he is a good man.

I run the household completely, I raised [my children], I spent my life caring for them … I make decisions on my own.

Within extended family households, the mother-in-law was sometimes identified as holding a higher position over wives and their husbands, and as such it was the mother-in-law who controlled access to the cash payment and decided how it was spent. In some instances, daughters-in-law who challenged this status quo were rebuked with threats or abuse. A married woman living with her in-laws said:

My mother-in-law took all the money … Whenever I asked her about the money she threatened that she is going to find my husband a new wife.

Money plays an important role in my situation. If I had money, I would not stay with [my mother-in-law].

Community: the influence of community stigma and social norms on women’s experiences with cash

While the cash programme was not intended to influence social dynamics, the infusion of cash into the community may have influenced social networks for some women. The communities in which the cash programme took place quickly ascertained that some households were receiving cash while others were not, and most women perceived an increase in jealous reactions from neighbours. However, patterns emerged in the qualitative data around marital status, revealing that the intensity of the backlash a woman experienced during the programme may have been related to her status before the programme started.

The qualitative data showed that outward displays of jealousy often related to stigma surrounding unaccompanied women. Reports of negative reactions among neighbours were described most often by widowed and divorced female heads of household, several of whom described experiencing heavier social sanctions such as gossiping and exclusion. A widowed female head of household told us:

[The cash] is not enough to cover all my expenses, and now all support stops. I fear the community; I fear that someone [will] decide to demolish the place.

I sent my children to buy sugar, oil, rice … I don’t go myself because I don’t want to hear any words [from the community].

People stopped helping me; for example, my neighbour was helping me because I have nothing, but when I started receiving the cash he stopped supporting me. Even my aunt, she got upset when I received the cash.

[In the future] I want to go back to work. Winter is coming … and I need a lot of things, and my neighbours are not helping me anymore.

We got rid of debts. I’m happy because the shop owners are sure that we are going to pay later. I can buy food, I take from here and pay-off there. Till now they are giving us groceries.

My husband was working but he can’t anymore. I worked as a seasonal farmer [to provide for our basic needs]. I was not working before [the war], but I was forced to work [when my husband became sick] … When I start receiving the cash, I was able to stop working.

Discussion

To summarise the key findings at the three ‘ecological levels’, see .

Table 2. Unintended outcomes of cash by ecological level as perceived by women in qualitative interviews.

While the cash programme had achieved its primary objective of improving short-term economic outcomes for targeted households (Falb et al. Citation2019), interviews with women revealed the extent to which pre-existing patriarchal social norms and gender discriminatory power dynamics influenced their ability to benefit from a programme whose single objective was to help families meet their basic needs in a humanitarian setting. Overlapping factors (gender, marital status and household composition) influenced women’s status, both in the community and in the home, and in turn influenced their decision-making power and ability to use or benefit from the cash.

The cash programme increased some women’s access to income, which challenged their lower status in society, and contradicted the idea of male domination and seniority in marriage and in the household. This created friction, occasionally prompting backlash that led to negative unintended outcomes. However, while the introduction of cash may have contributed to sustaining unequal power dynamics for some women, for others it may have helped to shift those social dynamics temporarily, and improve their overall situation.

Women of all groups were able to use the cash to pay back debts, which they perceived to reduce their economic dependence and increase their decision-making power. This is supported by the quantitative finding that, overall, women were able to significantly reduce economic-related negative coping strategies including debt, begging and skipping rent (Falb et al. Citation2019). Nevertheless, the majority of women described feeling anxious over meeting their basic needs once the programme ended, and commonly pointed to a lack of long-term livelihood opportunities as a driver of stress. This places another finding from the quantitative research in context: results showed that women’s reported depressive symptoms increased significantly between the baseline and endline (ibid.).

However, this finding contrasts with other research into longer-term, social development cash programming that shows significant improvements in psychological well-being and reductions in stress hormones of programme participants (Haushofer and Shapiro Citation2013). The protracted experience of conflict and displacement, combined with the prevailing uncertainty of income-generating opportunities for women in Raqqa, may have contributed to the increase in depressive symptoms. Given the limitations of our sample size, and our inability to prove a causal link in this study, further research is needed to understand fully the effect of cash transfers on mental health and well-being in humanitarian contexts.

Some women perceived that receiving the cash weakened their social networks. In an environment in which the vast majority of households were economically vulnerable, speculation around eligibility for the programme raised community tensions. Reviews from various contexts show similar accounts of community jealousy and negative impacts on community relationships, largely between host and IDP populations (Cross et al. Citation2018; Doocy and Tappis Citation2017). However, several studies indicate cash assistance has an overall positive effect on social cohesion because it gives IDPs and refugees the ability to pay back debts held in the local market (Sloane Citation2014), while others show little to no change in community relations (Campbell Citation2014).

Within the home, women’s experiences during the cash programme reflected the power dynamics of the household. While quantitative findings show that joint and independent decision-making increased for both married and unmarried women, it was primarily reported for smaller expenditures such as decisions around food and general household assets (Falb et al. Citation2019), which were the intended target of the programme. The qualitative data revealed that the introduction of cash into the home might have increased tensions between married women and their in-laws. Quantitative, non-causal findings also showed a significant increase from baseline to endline in reporting of some forms of IPV by respondents, which could be a result of men reasserting control over their wives (ibid.). However, it is not possible to determine whether these changes were the result of the cash programme due to the lack of a comparison group; the increase in IPV could have resulted from increased disclosure over time as familiarity with research staff increased.

This increase in IPV as a consequence of cash assistance is divergent from research from development settings; recent reviews show that targeting cash directly to women can increase their bargaining power within the household and result in a subsequent decrease in IPV (Buller et al. Citation2018; Gibbs et al. Citation2017; Hagen-Zanker et al. Citation2017). However, this type of targeting may not be feasible in emergency settings where cash assistance aims for acute response.

All this highlights the importance of considering the context when designing cash programmes that include women or other individuals who hold lower status in society. Linked to this is the need for clearer communication around the expectations of the programme, such as sensitisation activities that engage with the larger community, which incorporate a gender and power lens. Evidence shows that community sensitisation and communication is critical to reducing social tensions between recipients and non-recipients (Berg and Sefaris Citation2015). While families diverting scarce resources to other people or needs while their relatives receive cash is neither positive nor negative, increased communication about the terms of the programme could also serve to prevent instances in which families and neighbours permanently stop providing support to beneficiary households when the programme is short term.

Our findings demonstrate that further work is needed to design programmes in ways that avoid the potential null or negative consequences related to cash programmes in humanitarian settings. Such approaches may include implementing risk mitigation strategies (such as the Women’s Refugee Commission’s [Citation2018] Toolkit for Optimizing Cash-based Interventions for Protection from Gender-based Violence), testing short and feasible gender-related interventions to be delivered alongside cash programming, or making small adaptations to cash programming itself. There is some evidence that pairing economic-focused humanitarian response with programmes that address social norms can result in changes to attitudes about women, gender relations, power, and control of resources. This may result in less violence in families and communities where women are in receipt of cash. For example, one study in Côte d’Ivoire found that a programme where couples-based discussion groups occurred alongside Village Savings and Loan Association programming yielded additional reductions in IPV (Gupta et al. Citation2013). Another study in Bangladesh found that pairing cash assistance with a women’s support group centred on changing a specific behaviour (such as nutrition) potentially reduced IPV (Roy et al. Citation2017). The core components of such approaches could be distilled and adapted for more acute and volatile settings where programming must occur within shorter timeframes.

This type of gender-sensitive programming could result in longer-term positive shifts in social norms, such as increased joint decision-making over household spending during and after the cash programme. In addition, it remains critically important to test the potential optimal value, duration, and frequency of transfers in a given humanitarian context to amplify positive changes for women. More research is needed to determine which programme components can feasibly be adjusted or supplemented in acute humanitarian settings to leverage the potential of cash to maximise outcomes for women and girls.

Conclusion

The experience of individuals in humanitarian crises and their ability to benefit from humanitarian aid are dependent on the programme design’s consideration of factors that might influence their ability to access and utilise aid, such as gender dynamics, age, disability status, displacement status, and other intersecting identities. This research contributes important findings on the ways in which discriminatory gender norms and power dynamics in the household and wider community heighten the risks facing women. These power imbalances impact women’s experience of cash transfers, their decision-making capacity, and their use and control of resources. This analysis confirms the need for further research to increase our understanding of how cash programmes can be designed to mitigate risks and maximise outcomes for humanitarian populations.

Acknowledgements

This article is an output from a project funded by the UK Department for International Development (DFID) for the benefit of developing countries, as part of the What Works to Prevent Violence against Women and Girls global programme. However, the views expressed and information contained in it are not necessarily those of or endorsed by DFID, which can accept no responsibility for such views or information or for any reliance placed on them.

Notes on contributors

Alexandra Blackwell is a Research Coordinator at the International Rescue Committee focusing on cash and protection. Postal address: 1730 G Street NW, Suite 505, Washington, DC 20003, USA. Email: [email protected]

Jean Casey is Project Coordinator for the What Works to Prevent Violence against Women and Girls programme at the International Rescue Committee and a consultant specialising in qualitative research and gender issues.

Rahmah Habeeb is a Women’s Protection and Empowerment Manager with the International Rescue Committee.

Jeannie Annan is Chief Scientist at the International Rescue Committee.

Kathryn Falb is a Senior Researcher at the International Rescue Committee specialising in family violence and research lead for the What Works to Prevent Violence against Women and Girls study on cash assistance in north-east Syria.

Notes

1. Family violence, or domestic violence, includes violence perpetrated by intimate partners and other family members as manifested through physical, sexual, psychological, and/or economic abuse. Acts of omission are also included as a form of violence against women and girls perpetrated by family members within the home, including gender discrimination in terms of nutrition, education, and access to health care.

2. ISIS, or the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria, is a jihadist militant group and former unrecognised proto-state. ISIS may also be referred to as ISIL (the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant) or by its Arabic-language acronym, ‘Daesh’. This paper will refer to the group as ISIS, which is the term used globally by the International Rescue Committee (IRC), but it does not reflect any political affiliation or preference.

3. Eligibility for the cash assistance programme was determined by the IRC’s Economic Recovery and Development team, based on pre-defined economic and social vulnerability criteria using a household emergency assessment tool. Criteria considered when determining vulnerability included income, ownership of various types of assets, food insecurity, and receipt of remittances from family members residing abroad. Transfers per recipient household were $76 per month for three months, distributed to the heads of households, who could be either men or women depending on the household composition.

4. The objective of the existing programme was for selected beneficiaries to meet basic non-food item (NFI) needs and avoid negative coping strategies. The IRC designed the value of the cash transfer to cover approximately 80 per cent of the average NFI needs for a six-person family over three months, based on price trends of a comparative in-kind NFI kit traditionally distributed by the IRC in north-east Syria (which typically includes but is not limited to essential household items such as blankets, shoes and clothes, containers for water, cooking utensils, rechargeable fans in very hot weather, and portable heaters). The distribution of the total amount over three transfers was to allow recipients to better adjust their purchases to their monthly needs and align to normal household spending patterns to provide economic stability. This also reduced the risk of inducing inflation and other market distortions as a result of a large cash injection in the local economy that may have occurred with one lump sum payment. Further, the length of three months for the cash programme was selected, as this length of repeated assistance was the maximum accepted by most local authorities; they encouraged shorter-term programmes in order to ensure that more households might benefit from humanitarian assistance. There were no conditions placed on receiving the cash and there were no restrictions on how households were allowed to spend the cash.

5. Full details concerning research ethics can be found in the research report (Falb et al. Citation2019).

6. Religious police employed by ISIS in the regions under their control.

7. An unmarriageable male relative who escorts a woman in public.

8. The labels ‘transactional sex’ or ‘survival sex’ are often used to describe the dynamic where women and girls who have no resources and who cannot meet their basic needs are de facto coerced into sex. Since the ownership and control of resources most often resides with men, women and girls need to engage with men in order to try to attain resources. These men abuse their resources and social power to extort sexual activities from the women and girls who rely on these resources for survival. Expecting and demanding sexual activities as a condition of sharing resources is an abuse of women and girls, and it reflects men’s entitlement to sexual access to women and girls. For this reason, the IRC will refer to this construct as men’s sexual exploitation and abuse of women and girls.

9. A charitable cash gift given during Ramadan to families and individuals perceived as poor by the community. In north-east Syria there is a preference for people to give their cash gift directly to their chosen recipient rather than through a charitable organisation. Charity is more likely to be given to widows and other ‘socially acceptable’ groups than to divorced or unmarried women or families from outside the community.

References

- Bailey, Sarah and Kerren Hedlund (2012) ‘The impact of cash transfers on nutrition in emergency and transitional contexts: a review of the evidence’, HPG Commissioned Reports, London: Overseas Development Institute

- Baird, Sarah, Francisco HG Ferreira, Berk Özler and Michael Woolcock (2013) ‘Relative effectiveness of conditional and unconditional cash transfers for schooling outcomes in developing countries: a systematic review’, Campbell Systematic Reviews 9: 8

- Berg, Michelle and Louisa Seferis (2015) ‘Protection outcomes in cash based interventions: a literature review’, Danish Refugee Council, UNHCR, and ECHO, http://www.cashlearning.org/downloads/erc-protection-and-cash-literature-review-jan2015.pdf (last checked 12 June 2019)

- Buller, Ana Maria, Amber Peterman, Meghna Ranganathan, Alexandra Bleile, Melissa Hidrobo and Lori Heise (2018) ‘A mixed-method review of cash transfers and intimate partner violence in low-and middle-income countries,’ The World Bank Research Observer 33(2): 218–258 doi: 10.1093/wbro/lky002

- Campbell, Leah (2014) ‘Cross-sector cash assistance for Syrian refugees and host communities in Lebanon: An IRC Programme’, http://www.cashlearning.org/downloads/calp-case-study-lebanon-web.pdf (last checked 12 June 2019)

- Cislaghi, Beniamino and Lori Heise (2018) ‘Using social norms theory for health promotion in low-income countries’, Health Promotion International, https://academic.oup.com/heapro/advance-article/doi/10.1093/heapro/day017/4951539 (last checked 12 June 2019)

- Cross, Allyson, Tenzin Manell and Melanie Megevand (2018) Humanitarian Cash Transfer Programming and Gender-based Violence Outcomes: Evidence and Future Research Priorities, New York: International Rescue Committee & Women’s Refugee Commission, http://www.cashlearning.org/resources/library/1271-humanitarian-cash-transfer-programming-and-gender-based-violence-outcomes-evidence-and-future-research-priorities (last checked 12 June 2019)

- Dickson, Kelly and Mukdarut Bangpan (2012) Providing Access to Economic Assets for Girls and Young Women in Low-And-Lower Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review of the Evidence, London: EPPI Centre, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/57a08a61e5274a27b2000589/Economic_assets_2012Dickson.pdf (last checked 12 June 2019)

- Doocy, Shannon and Hannah Tappis (2017) ‘Cash-based approaches in humanitarian emergencies: a systematic review’, 3ie Systematic Review Report, 28, Oslo: The Campbell Collaboration

- Falb, Kathryn, Jeannie Annan, Alexandra Blackwell and Julianne Stennes (2019) Cash Transfers in Raqqa Governorate, Syria: Changes Over Time in Women’s Experiences of Violence and Wellbeing, Washington DC: International Rescue Committee and London: UK Department for International Development, https://www.rescue-uk.org/report/cash-transfers-raqqa-governorate-syria (last checked 12 June 2019)

- Freccero, Julie, Audrey Whiting, Joanna Ortega, Zabihullah Buda, Paschal Awah, Alexandra Blackwell, Ricardo Pla Cordero and Eric Stover (2019) ‘Safer Cash in Conflict: Exploring Protection Risks and Barriers in Cash Programming for Internally Displaced Persons in Cameroon and Afghanistan’, Manuscript submitted for publication

- Gibbs, Andrew, Jessica Jacobson and Alice Kerr Wilson (2017) ‘A global comprehensive review of economic interventions to prevent intimate partner violence and HIV risk behaviours’, Global Health Action 10(sup 2): 1290427 doi: 10.1080/16549716.2017.1290427

- Gupta, Jhumka, Kathryn L. Falb, Heidi Lehmann, Denise Kpebo, Ziming Xuan, Mazeda Hossain, Cathy Zimmerman, Charlotte Watts and Jeannie Annan (2013) ‘Gender norms and economic empowerment intervention to reduce intimate partner violence against women in rural Côte d’Ivoire: a randomized controlled pilot study’, BMC International Health and Human Rights 13(1): 46 doi: 10.1186/1472-698X-13-46

- Hagen-Zanker, Jessica, Luca Pellerano, Francesca Bastagli, Luke Harman, Valentina Barca, Georgina Sturge, Tanja Schmidt and Calvin Laing (2017) The Impact of Cash Transfers on Women and Girls, London: Overseas Development Institute, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/58ca9e7ae5274a16e800001e/11370.pdf (last checked 12 June 2019)

- Harvey, Paul and Sara Pavanello (2018) Multi-Purpose Cash and Sectoral Outcomes: A Review of Evidence and Learning, UNHCR, https://www.unhcr.org/5b28c4157.pdf (last checked 12 June 2019)

- Haushofer, Johannes and Jeremy Shapiro (2013) ‘Household response to income changes: evidence from an unconditional cash transfer program in Kenya’, Massachusetts Institute of Technology 24(5): 1–57

- Kabeer, Naila, Caio Piza and Linnet Taylor (2012) What are the Economic Impacts of Conditional Cash Transfer Programmes? A Systematic Review of the Evidence, London: EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/57a08a6840f0b649740005a4/CCTprogrammes2012Kabeer.pdf

- O’Keefe, Jennifer (2016) ‘Women’s Protection and Livelihoods: Assistance to Central Africa Refugees and Chadian Returnees in Southern Chad: Program Evaluation Final Report’, New York, NY: International Rescue Committee, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/irc_chad_endline_evaluation_southern_chad.pdf (last checked 12 June 2019)

- Roy, Shalini, Melissa Hidrobo, John Hoddinott and Akhter Ahmed (2017) ‘Transfers, behavior change communication, and intimate partner violence: Post-program evidence from rural Bangladesh’, Review of Economics and Statistics 0: 1–45

- Sloane, Emily (2014) ‘The Impact of Oxfam’s Cash Distributions on Syrian refugee households in Host Communities and Informal Settlements in Jordan’, http://www.cashlearning.org/downloads/impact-assessment-of-oxfams-cash-distribution-programme-in-jordan--january-2014.pdf (last checked 12 June 2019)

- Stark, Lindsay and Alastair Ager (2011) ‘A systematic review of prevalence studies of gender-based violence in complex emergencies’, Trauma, Violence, & Abuse 12(3): 127–134 doi: 10.1177/1524838011404252

- Women’s Refugee Commission (2018) Mainstreaming GBV Considerations in CBIs and Utilizing Cash in GBV Response: Toolkit for Optimizing Cash-based Interventions for Protection from Gender-based Violence, New York: Women’s Refugee Commission, http://wrc.ms/cashandgbv (last checked 12 June 2019)

- UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (2018) ‘Syria Crisis: Northeast Syria: Situation Report No. 27 (15 July 2018–31 August 2018)’, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/north_east_syria_sit_rep_15_july_to_31august.pdf (last checked 12 June 2019)