ABSTRACT

Emerging global crises such as climate change, massive migrations, pandemics, and environmental degradation are posing serious risks to humanity, threatening ecosystems and rural livelihoods across the globe. The poor, and especially the most marginalised among the poor, are disproportionately affected. Climate change in particular is expected to exacerbate pre-existing social inequalities, including gender inequalities. Therefore, innovative and equitable climate adaptation and mitigation strategies will be needed. This article reviews the progress so far in integrating a gender perspective into climate change policy discussions and agreements at global and national levels.

Las crisis emergentes a nivel mundial, por ejemplo, el cambio climático, las migraciones masivas, las pandemias y la degradación del medio ambiente, están planteando graves riesgos para la humanidad, amenazando los ecosistemas y los medios de vida rurales. Los pobres, y entre ellos sobre todo los más marginados, son afectados de manera desproporcionada. Se prevé que el cambio climático, en particular, exacerbe las desigualdades sociales preexistentes, incluidas las desigualdades de género. Ello significa que serán necesarias estrategias innovadoras y equitativas de adaptación al clima y de mitigación de los daños provocados por sus cambios. El presente artículo examina los avances realizados hasta la fecha en la integración de una perspectiva de género a los debates y los acuerdos sobre políticas relativas al cambio climático, tanto a nivel mundial como nacional.

Les crises mondiales émergentes comme le changement climatique, les migrations en masse, les pandémies et la dégradation environnementale représentent des risques sérieux pour l’humanité ; elles menacent les écosystèmes et les moyens d’existence partout dans le monde. Les personnes pauvres, et en particulier les pauvres les plus marginalisés, sont touchées de manière disproportionnée. On s’attend en particulier à ce que le changement climatique exacerbe les inégalités sociales préexistantes, y compris les inégalités entre les sexes. Ainsi, des stratégies innovantes et équitables d’adaptation et d’atténuation en matière de changement climatique seront requises. Cet article examine les progrès effectués jusqu’ici dans l’intégration d’une perspective de genre dans les discussions et les accords sur les politiques face au changement climatique à l’échelle mondiale et nationale.

Introduction

The climate crisis is widely recognised to be a phenomenon which affects women and men, girls and boys in different ways due to the gendered roles and relations that shape human societies, from the household to high-level decisions taken by international and national political and economic institutions. Right now, feminist advocates seeking to influence global actors and institutions find themselves at a crossroads, where past gender equality strategies have proved insufficient to achieve the sea-change that women and girls throughout the world need to see in international and national debates, policies, and practices concerning climate crisis. For example, a recent assessment of progress made on the Sustainable Development Goals reveals that globally, in 2018, more women still experience poverty than men, and women have a 10 per cent higher risk of experiencing food insecurity. Climate-related disasters and effects such as increasing temperatures, rising sea levels, and biodiversity loss are also affecting women’s livelihoods disproportionately (UN Women Citation2019). This highlights an urgent question. What needs to be done now, 25 years after Beijing, to create real change to combat climate crisis and environmental degradation, in ways that support gender equality and the realisation of women’s rights?

This article focuses on how gender equality and women’s rights perspectives have been integrated into climate change policy at both international and national levels, as well as in different regions of the world. We also examine some promising models for policy action. While doing so, we highlight key research that can serve to illustrate current and persistent data and gender gaps as well as examples for positive policy change. We lastly argue for the need for more efficient gender and climate adaptation strategies, with new strategies that aim at directly challenging root causes of gender inequalities.

In our analysis here, we draw on primary research that we undertook on the integration of gender in all Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs) in 2016, in all updated Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) as of November 2019, and in National Adaptation Plans (NAPs) submitted to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) as of 2 September 2020. In addition, we draw on secondary data as well as our first-hand experience working in the sectors of gender and policy in relation to agriculture, climate, and development, in both universities and Consultative Group for International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) research centres.

Sophia Huyer has worked in gender and sustainable technology development and policy with a range of different gender-focused organisations for 25 years, most recently as the Gender and Social Inclusion leader of the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS). Also in CCAFS, Mariola Acosta has researched the intersection between gender, agriculture, and climate change in East Africa and Latin America, with an emphasis on improving gender inclusion in climate policy. Most recently she has engaged with the Inclusive Rural Transformation and Gender Equity Division of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Tatiana Gumucio’s research has focused on gender-sensitive climate services and safety nets, as well as supporting integration of gender in climate policy and programming in natural resource management and agriculture. Jasmin Irisha Jim Ilham has research experience at the intersection of food systems and climate adaptation, while bringing in a policy perspective from a developing country lens through her involvement with the UNFCCC Women and Gender, as well as Youth Constituencies.

Gender equality in global climate policy: too little too late?

The process of integrating gender issues into debates and policymaking around environment, climate change, and development has been a long one. Discussions of key relevance to climate change and crisis have long been held in global policy circles focusing on related fields: among these, sustainable development, environment, and other fields including agriculture. While gender equality is often included in these discussions, it tends not to be included in relation to climate change, and as Raczek et al. (Citation2010) note, policies on gender and climate change have been slow to emerge. In comparison to these other processes, the integration of gender equality into climate policy has been slow at both global and national levels.

In the face of growing scientific evidence of the reality of the climate crisis and the urgency to use that evidence to inform global responses,Footnote1 the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), was first created by the United Nations Environment Programme (UN Environment) and the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) in 1988. The IPCC is an international body that undertakes scientific assessments of the causes of climate change, impacts, and future risks, and what adaptation and mitigation actions can reduce those risks. Both its annual reports and special reports tend to focus primarily on the physical science aspects of climate change, but in 2014 the first report to address Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability (IPCC Citation2014) was published, with an updated report planned for 2021. While research on gendered impacts (and a chapter on gender and climate change) is included in the full 2014 report, the word ‘gender’ is found only three times in the Summary for Decision Makers, and the word ‘women’ not at all. The word ‘social’ occurs only 13 times.

The participation of women scientists in IPCC assessments and leadership has also been low. Nhamo and Nhamo (Citation2018) report that women are not well represented in IPCC bureaus and only 27 per cent of author nominations for the IPCC Special Report on 1.5°C were female (IPCC Citation2018). Analysis of the representation of women as authors over time did find an increase from less than 5 per cent in Assessment Report 1 (AR1) in 1990 to 33 per cent in AR6 (IPCC Citation2019). As noted by Gay-Antaki and Liverman (Citation2018), this consistently low representation is partly due to the limited participation of women in the earth sciences overall. Their survey of women IPCC authors revealed that women identified as barriers to their participation: family responsibilities; discrimination associated with being a woman; race; nationality; command of English; and discipline.

In February 2020, the IPCC adopted a Gender Policy and Implementation Plan to: enhance gender equality in IPCC processes; promote a gender-inclusive environment including in-meeting arrangements and support for participants; and raise awareness of gender-related issues through training and guidance (IPCC Citation2020).

Landmark conferences and events

In the 1990s, feminist advocates actively engaged with several environment-related policy processes. In 1992, the United Nations (UN) convened the Rio Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) – known as the ‘Earth Summit’, where women’s role and position in society were discussed in relation to sustainable development. In the Women’s Tent, ‘The Planeta Femea’, hundreds of women’s rights organisations from all around the world critically followed the negotiations while forging new alliances. However, despite this civil society activism on the part of feminists, and progress made on gender and sustainable development in general, the Rio Convention demonstrated a major gap on gender concerns. In the Rio+20 (UNCSD Citation2012) outcome document, only one reference was made to climate impacts on women, in a paragraph on disaster risk management.

Chapter 24 of Agenda 21 – a non-binding UN action plan on sustainable development, produced in the wake of Rio (UN Conference on Environment and Development Citation1992) – focused on Global Action for Women Towards Sustainable and Equitable Development. Agenda 21 was one of the first major UN documents to comprehensively incorporate women’s roles, positions, needs, and expertise in sustainable development, including in relation to training, participation in decision-making, health, land management, and water resources (Raczek et al. Citation2010). Yet climate change was not explicitly included in Chapter 24 of the Agenda and just one reference was made elsewhere to women in this context, in relation to developing response strategies to address the environmental, social, and economic impacts of climate change.

The UN Convention on Biological Diversity (UNCBD), also signed in 1992, recognised the human, gender, and social dimensions of biological diversity in terms of food security, medicine, fresh air and water, shelter, and a healthy environment. Women’s role in the conservation and sustainable use of biological diversity, and the need for their full participation at all levels of policymaking were recognised.

During the same period, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) was adopted, signed by governments at the Rio Earth Summit in 1992. The UNFCCC convenes an annual Conference of the Parties (COP) who have signed on to the Convention for negotiations on different aspects. Unlike the case of the other environment-related Conventions, UNFCCC outcome documents have made no reference to women or gender equality until recently, and little reference to human or social dimensions.Footnote2

In 1995, the UN Fourth World Conference on Women produced the Beijing Platform for Action (BPfA) that acknowledged the environment as a critical area for concern. Ten years previously, in 1985, at the UN Third World Conference on Women in Nairobi, a series of workshops on women and the environment had been organised. At Beijing, this area of activism and enquiry generated strong momentum. The BPfA recognised that environmental degradation, while affecting all human lives, often has a more direct impact on women. It analysed the structural links between gender relations, environment, and development, with special emphasis on agriculture, industry, fisheries, forestry, environmental health, biological diversity, climate, water resources, and sanitation. Despite this comprehensive perspective, the Beijing declaration had only one reference to climate change, in an enumeration of relevant sectors and actions to be taken. While there were four other references in the BPfA to the word ‘climate’, these were all relating to context, not a focus on climate change or crisis.

The era of gender mainstreaming

In the 2000s, after the decade of environmental conferences, gender justice advocates began to articulate critiques of the techno-scientific nature of climate policy and solutions. The argument was made that these frameworks separated climate action from social and gender dimensions, and mandated technical responses (MacGregor Citation2010).

Concerns were raised by feminists about a focus on women as most vulnerable to climate impacts, often attributed to a so-called ‘special’ relationship to nature – in effect making them bear the possible burden of the climate crisis (Resurreccion Citation2013). As well, an emphasis on material impacts was seen to ignore gendered power relations shaping climate politics and affecting societal–environmental inequalities and interactions (MacGregor Citation2010). It was also noted that climate change influenced a shifting of environmental debate and action to science and policy institutions, both dominated by men, leading to references to the ‘masculinisation’ of environmental politics and policy (MacGregor Citation2010), and the ‘sidetracking’ of development and women’s concerns in climate policy (Denton Citation2002). Advocates began to call attention to the threat posed by adaptation and mitigation approaches that ignore social dimensions and gender relations, and the extent to which they can exacerbate the hardships of already disadvantaged women in both North and South (Terry Citation2009).

The BPfA had been the first international convention to include a gender mainstreaming mandate: it called on states to consider gender issues at all stages of the policy cycle and at all governance levels, from global to local, and across all sectors of society (Alston Citation2014; United Nations Citation1995). Since 1995, gender mainstreaming discourse has largely permeated environment and development policymaking around the globe, to varying degrees of success. Concerns exist that the strategy has become largely depoliticised, with many policy actors failing to implement gender mainstreaming requirements (Moser and Moser Citation2005; Mukhopadhyay Citation2014).

That most current gender mainstreaming strategies seem ill-equipped to bring real transformation is worrisome, even more so considering that climate change is expected to widen social inequality and threaten achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals. This was underlined by the IPCC, in its assessment that climate change impacts will slow down both economic growth and poverty reduction, erode food security, and prolong and create poverty traps, with the effect of exacerbating poverty in developing countries and increasing inequality (IPCC Citation2014). Dankelman (Citation2010) has argued that climate change adds a new note of urgency to the gender–environment nexus identified since Rio, by exacerbating existing gender inequalities.

While there has been gradual progress on gender mainstreaming in global climate policy, results continue to be uneven. The first steps by the COP of the UNFCCC to promote gender equality and women’s participation in decision-making in the Convention (UNFCCC Citation2001) were taken in 2001. The next major step was taken a full 11 years later, with the decision to promote gender balance and women’s participation on all UNFCCC delegations, boards, and bodies (UNFCCC Citation2012). Around this time, the Women and Gender Constituency, established in 2009 by 28 non-government organisations, was recognised as an observer organisation to the UNFCCC (in 2011).

In 2014, the Lima Work Program on Gender (LWPG) (UNFCCC Citation2014) committed governments to advancing implementation of gender-responsive climate policies and mandates across all areas of UNFCCC negotiations. The decision established a two-year work programme (renewed at COP22 in 2016) that included: a review of implementation of all gender-related mandates; training and awareness-raising for delegates on gender-responsive climate policy; training and capacity building for women delegates; guidelines for implementing gender in climate change activities; and the appointment of a senior focal point on gender at the UNFCCC Secretariat.

The Paris Agreement on Climate Change – reached in 2015 at COP21 – marked a landmark accord to address climate change and increase actions and investments (including support to developing countries) to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions while promoting sustainable development. It included the first gender mainstreaming reference in global climate negotiations. The Agreement also states that adaptation actions and capacity development should be gender-responsive (UNFCCC Citation2015).

Following the Paris Agreement, in November 2017 at COP23, the first UNFCCC Gender Action Plan was adopted (UNFCCC Citation2017). This was a landmark decision, integrating both gender equality and human rights into climate action, and addressing the gender dimensions of climate impacts, adaptation, and mitigation. It calls for gender-responsive policy in all adaptation and mitigation activities and implementation processes (finance, technology development and transfer, and capacity building) and states that women should participate in decision-making on the implementation of climate policies. It also recognises that all targets and goals in activities under the Convention should mainstream gender in order to increase their effectiveness. In November 2019 at COP25, a renewed and enhanced five-year LWPG was adopted along with an updated Gender Action Plan, focusing on: capacity building, knowledge management and communication; gender balance, participation and women’s leadership in the UNFCCC process; coherence within UNFCCC bodies and among UN entities and stakeholders; gender-responsive implementation and means of implementation; and monitoring and reporting on gender-related mandates under the programme.

Intersecting with these international policy debates, conventions, and agreements, are the processes of integrating gender concerns into national climate policy. National-level changes are obviously linked to the international progress and agreements described above. International policy statements – even when not legally binding or enforceable – establish the function of setting norms and standards, creating an environment more or less hospitable to gender equality and women’s rights and enabling feminists to lobby national governments to act on international commitments and standards. How has this process of integration evolved in climate-related policy?

While the Gender Action Plan and the Paris Agreement provided a solid basis for moving forward on gender equality in global and national-level policy and action, results came quite late. It is only in the last five years that social and gender dimensions have been given significant attention.

National climate policy: rhetoric or action?

The integration of gender in environment, food security, agriculture, and climate change policies at the national level in different regions of the world is considerable – although the degree of inclusion differs depending on the country and sector analysed.

For example, Gumucio and Tafur Rueda (Citation2015, 53, 54) found in their analysis of 105 policies on climate change, environment, and agriculture in Latin America that, across the region, two-thirds of national agriculture and climate policies had no mention of gender issues; slightly over half of all national climate policies did not include gender to any extent. Acosta et al. (Citation2019) found that since 2015 in Guatemala and Honduras there has been an increase in attention to gender issues in climate policies. However, while most policies, laws, strategies, and plans have included some mention of gender, none have allocated financial resources for implementation of gender action.

In his review of eight countries in East and Southern Africa, Nhamo (Citation2014) concluded that the mainstreaming of gender in climate policies was gaining momentum in the region, although the degree of mainstreaming varied from country to country. Uganda, Kenya, and Rwanda had the highest number of references to women and gender in their national climate policies or plans, while Mauritius and Malawi had the lowest number. Nhamo emphasised the importance of increasing attention to gender, especially in future climate action plans.

With a focus on East Africa, and using the same framework as Gumucio and Tafur Rueda (Citation2015), Ampaire et al. (Citation2020) examined the extent to which gender issues were integrated and budgeted for in 155 climate change, environmental, and agriculture policies in Tanzania and Uganda. Their study also found increasing integration of gender dimensions in policy in both countries, although they discovered certain disharmonies across governance levels; an insufficient attention to structural causes of gender inequality, with gender issues often being equated to ‘women’s issues’; and limited budget allocations for gender (if at all) that varied across the different financial years analysed.

Operationalising gender equality in climate policy: national climate instruments

A number of instruments are used to structure national planning and commitments relating to climate adaptation and mitigation. Gender analyses of these instruments find poor integration of gender dimensions so far. However, they enable the slow speed of progress to be monitored, providing a basis for addressing challenges and accelerating change.

These instruments include: NAPs, Nationally Appropriate Mitigation Actions (NAMA), REDD+ (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation) and NDCs. NDCs outline the contributions to adaptation and mitigation that each country commits to. INDCs are the first step towards full NDCs.

Research on gender equality in REDD+ regimes finds low participation of women in decision-making in the forestry sector and hence in national REDD+ regimes (Pham et al. Citation2016), as well as marginalisation in the design and implementation of REDD+ policies (Arwida et al. Citation2017). Analysis of NAMAs has found that women or gender equality are generally not integrated to any noticeable extent (Fisher and Mohun Citation2015), with the exception of Georgia’s NAMA on ‘Efficient use of biomass for equitable, climate proof and sustainable rural development’ (Bock et al. Citation2015) and Kenya’s NAMA for the dairy sector.Footnote3 In their review of 31 National Adaptation Programmes of Action (NAPAs)Footnote4 submitted by African countries to 2011, Holvoet and Insberg (Citation2014) noted that discussion of effects on gender equality of climate adaptation was mainly limited to vulnerability and on who is disproportionately affected by climate change, and does not cover implementation as measured by budgets, indicators, or targets. They found almost no references to underlying structures of constraint and opportunity for either women or men (Holvoet and Inberg Citation2014). An updated review of NAPS submitted on the UNFCCC NAP Central webpage as of 2 September 2020, was undertaken by one of the authors of this article, Sophia Huyer for this article. She found that 18 of 19 NAPs mention ‘gender’ or ‘women’. The number of mentions ranges from a single reference to multiple, with three of the documents referencing the word only once, and 14 referencing gender in one or more sectors. Similar to the INDC and NDC reviews discussed below, most countries made references to women or gender in relation to agriculture (ten), economy/livelihoods (nine) and health (eight). Approaches were split between those NAPs that tend to address women in a context of vulnerability or as beneficiaries of adaptation actions (11), and those that see women as stakeholders or active agents in adaptation (nine).Footnote5

Huyer was also involved in a study (UNDP Citation2016) that reviewed INDCs submitted to the UNFCCC as of April 2016. It found that of 161 INDCs submitted, 65 (40 per cent) made at least one reference to gender equality or women. However, similar to the research on NAPs and NAPAs, the study found that many of these references focused on women’s vulnerability to the effects of climate change. Very few identified women’s roles, needs, and perspectives in climate sectors such as energy or agriculture. The scarcity of references to women’s roles and agency, or to the existence of gender inequality and the need to challenge it, reflects a lack of understanding of the role women play in addressing the impacts of climate change and in reducing emissions, as well as the importance of these sectors to women’s livelihoods and well-being (UNDP Citation2016).

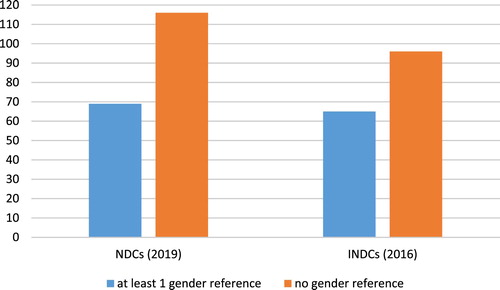

Many countries revised their INDC to meet a 2020 deadline to submit NDCs that outline national actions to meet the Paris Agreement emission targets. Accordingly, in 2019 two of the authors of this article undertook a second study.Footnote6 NDCs submitted to the UNFCCC as of November 2019 were reviewed for their degree of gender integration, using similar methods to the 2016 INDC study. Using these methods, the analysis of the primary research carried out for the purpose found that of the 185 NDCs submitted, 69 made references to gender or women. This is slightly more than one-third – an actual drop from the INDCs.

In this second study, we also analysed whether gender was included in (1) national climate priorities, (2) specific sectors, and (3) the national policy context (see ). Our analysis found that, of the 69 NDCs, a majority (60) made at least one reference to gender or women in relation to national climate priorities; 31 NDCs made at least one reference to gender or women in specific sectors; finally, 38 NDCs made at least one reference to gender or women in the national policy context.

Table 1: Gender integration in NDCs per category of analysis

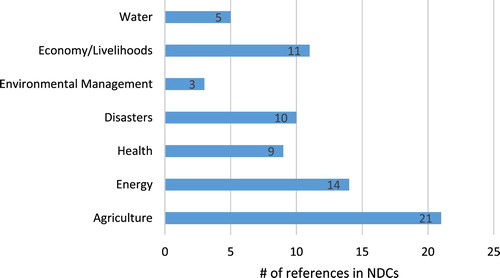

Analyses of gender integration in sectors and in the national policy context revealed that of 31 NDCs that included references to gender, few contained specific and substantive references to women’s role in climate sectors. Of those that did, references to gender equality or women tended to be made most commonly in relation to agriculture – 21 NDCs (see ). References to women or gender were also made in relation to energy (14 NDCs), economy/livelihoods (11), disaster risk reduction (ten) and health (nine) sectors. Very few NDCs made references to gender or women in water (five) or environmental management (three).

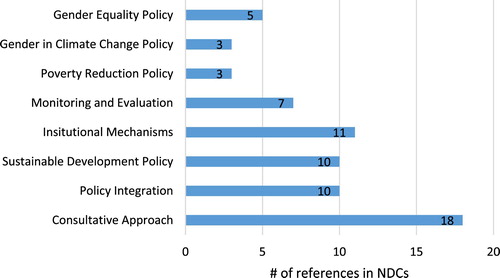

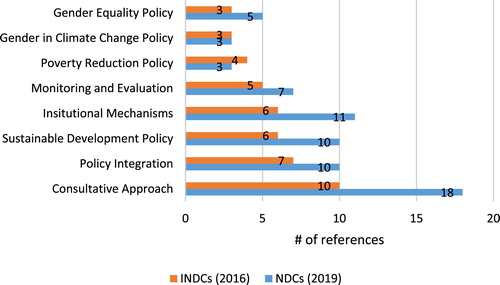

References to gender or women in the national climate policy context were made most frequently concerning the importance of multi-stakeholder and consultative approaches (18 countries) (see ). References to consultation often highlighted commitments to gender and human rights principles and representation of different social groups in the formulation and implementation of the NDC. Next in frequency, references to gender were made in discussions of institutional mechanisms for planning and implementing the NDC (11 countries) in the form of existing or in-progress national climate policy instruments that integrated gender.

Similarly, gender references often emerged in relation to existing national sustainable development policy (ten countries), and to integrating gender policies or women’s ministries in cross-sectoral work on climate change (ten countries). Gender references occurred less frequently as they pertained to inclusion of gender outcomes in monitoring of NDC actions (seven countries). Very few countries made references to an existing national gender equality policy (five countries), gender inclusion in national poverty reduction policy (three countries), or to a national gender and climate change policy (three countries).

It is not surprising that gender references are minimal in the last group of policies mentioned, given that only ten countries have approved gender and climate action plans or strategies to date.Footnote7 It is promising that several NDCs recognise the importance of representing women’s and men’s interests equally in consultative processes. It is also significant that gender-sensitive climate policy instruments in some countries inform NDC priorities and actions; however, it is problematic that few countries include gender outcomes in NDC monitoring and illustrative of the insubstantial degree of commitment to gender equality in many NDCs. While fewer NAPs have been submitted, the greater proportion of submissions addressing women and gender issues in comparison to NDCs may indicate a better understanding of the role of women in adaptation than in mitigation.

In comparison to the INDCs reviewed in 2016, in our second study we observed a slight decrease in gender integration from 40 to 37 per cent. While the number of NDCs that make at least one gender reference is greater than the number of INDCs that do (69 NDCs in comparison to 65 INDCs), the overall number of NDCs is higher (see ). This indicates that more NDCs make no reference to gender. It also should be noted that many countries that submitted INDCs simply resubmitted the documents as NDCs. However, Within the group of NDCs that make reference to gender, in some cases, the original INDC was updated to add references to gender. An example is Benin’s NDC which highlights rehabilitation of irrigation schemes that include ‘300 ha of market-gardening for women’ (Republic of Benin Citation2018, 20); in contrast, gender references in its INDC were related only to health. Similarly, while Eritrea’s INDC did not include any references to gender in sectoral actions or strategies, its NDC presents energy-saving cookstoves as part of an adaptation strategy that will reduce waste biomass while promoting the ‘wellbeing of women and children’ (The State of Eritrea Citation2018, 21).

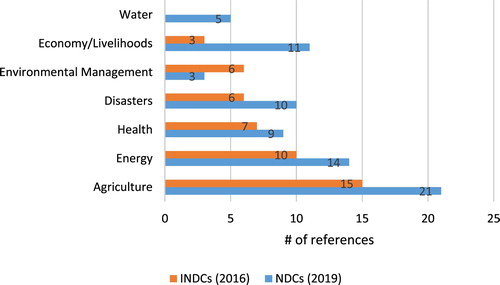

Overall, the degree of gender integration in specific sectors and in the national policy context in NDCs remains close to that in the INDCs, with a slight increase (see and ). The number of countries making reference to gender in relation to agriculture increased to 21 from 15; and to 14 countries from ten in relation to energy. We also designated a new category, ‘water’, given the inclusion of gender and water references in several NDCs (five). The number of NDCs containing gender references in consultative approaches increased to 18 from ten, and those containing references related to institutional mechanisms increased to 11 from six.

As in other reviews of climate-related policy, this review found that the current group of NDCs do not address structural causes of gender inequalities, and gender references are often embedded within vulnerability discourses. For example, references to women as vulnerable groups occurred in 41 NDCs, an increase from 30 INDCs (UNDP Citation2016). However, several NDCs recognise women’s roles in priority sectors, how climate variability and change affect these roles, and what actions will address climate impacts on women. Additionally, where specific actions and measures are discussed, they often involve access to resources, capacity-building, and enhancing production.

Towards gender equality in climate policy

From the previous sections, it is clear that the increasing threats posed by climate change and global environmental degradation to rural communities, particularly to people who are vulnerable, will require more effective gender equality and inclusion approaches. However, even though gender mainstreaming has been introduced in climate policy around the globe, it has produced limited results in tackling gender inequalities (Ampaire et al. Citation2020). Critics claim that inadequate progress to date has been due partly to a disproportionate focus on addressing ‘gender symptoms’ rather than on the causes of gender inequalities (AAS Citation2012; FAO et al. Citation2019). An emphasis on women’s vulnerability to climate change may divert attention from the structural inequalities triggering this vulnerability and may lead to policy targeting short-term needs (Arora-Jonsson Citation2011; Okali and Naess Citation2013). Another common criticism is that gender mainstreaming, rather than serving as a strategy to achieve gender equality, has instead become a largely technocratic approach of ‘add women and stir’ (Porter and Sweetman Citation2005; Tiessen Citation2007), with some going so far as to assert that gender mainstreaming ‘exists only in theory’ (Brouwers Citation2013, 22).

Strategies that address gender inequalities at a deeper level include capacity development for policy- and decision-makers. Sharing research-based evidence with parliamentarians can help bring more attention to gender and climate concerns, and encourage the development of appropriate policy and regulatory frameworks. In Uganda (Okiror Citation2016), Tanzania (Natai et al. Citation2019), and Nepal (Chanana and Sahin Citation2018), engagement with members of parliament resulted in an increased appreciation of gender issues emerging as a result of climate change. In the case of Uganda, parliament later rejected a much-anticipated climate bill on the grounds of insufficient inclusion of gender, among other issues (Namuloki Citation2017).

Other institutional approaches to embed gender more substantively into national policy include co-ordination mechanisms such as cross-department climate committees, gender focal points in climate-related ministries, and the participation of women’s ministries and national organisations on climate bodies (see Ampaire et al. Citation2020; UNDP Citation2016).

Discrepancies between national and local policy and strategies can become a barrier to effective adaptation (Resurreccion et al. Citation2019). Recent research indicates that the success of new strategies for gender equality will partly be affected by the extent to which local actors understand these discourses and support policy action (Kantor et al. Citation2015; Ketting Citation2017). Related to this, Acosta, van Wessel et al. (Citation2020b) and Alston (Citation2014) emphasise the importance of considering local understandings and interpretations of gender, since power relations, cultural norms, and gender roles are deeply embedded within the very organisations mandated to mainstream gender.

Engaging local policy actors seems in this way fundamental for the effectiveness of climate programming. Similarly, working with local policy actors in developing training materials can be a way to identify entry points for gender action. In a recent example, a guide for the inclusion of gender in climate-smart agriculture was developed through a series of participatory workshops with 22 government and non-government organisations from the agriculture, livestock, forestry, and environment sectors in Guatemala. The content was specifically targeted to national and local priorities, increasing ownership and relevance (Acosta, Findji et al. Citation2020a). Participatory and anticipatory climate change scenarios developed with local policymakers have proved useful in integrating climate change into national policy in different regions, and could be a model for developing more effective gender climate policy (Mason-D’Croz et al. Citation2016). Civil society stakeholder groups such as the Women and Gender Constituency on Gender Just Climate Solutions, consisting of 29 different women’s and environmental civil society organisations, bring the experience of national and local gender just climate initiatives to the global negotiating table (WECF Citation2019).

Public–private partnerships (PPPs)Footnote8 in forestry and energy may also be an opportunity to integrate women into climate action. For example, as part of a PPP for the restoration of degraded forest reserves involving FORM GHANA Ltd and the Forestry Commission of the Government of Ghana, women were encouraged to apply for employment generated by the PPP, a women’s association was supported, capacity building and training opportunities were provided for female employees, and meetings were organised with women in the participating communities (IUCN Citation2019). In Morocco, a solar energy programme implemented by the Moroccan Agency for Solar Energy and the Arabian Company for Water and Power took steps such as planning specific meetings for women and adapting communication products for illiterate men and women (IUCN Citation2019). However, the potential for intensifying inequalities in projects like this needs to be recognised. Examples of private-sector mitigation initiatives exist that demonstrate the potential of low-carbon approaches to penalise or disadvantage women (see Wang and Corson Citation2015).

Amidst these discussions, and the promise for change that tackling gender inequality brings, movement towards a more effective agenda for climate and gender equality runs the risk of continuing as political discourse with little actual shifting of inequalities on the ground. For this, a re-politicisation of gender seems fundamental, where policy and practice move away from token efforts for change to accountability and action. With the ever-increasing threat that climate change poses to rural livelihoods and ecosystems, challenging the structural causes of gender inequality and detrimental gender norms is needed to encourage access to and control over land and water, natural resources, productive resources, early warning and climate information, and decision-making, as well as easing women’s increasing work burden.Footnote9 The disconnect between national and local levels needs overcoming.

Women’s voices need to be heard in climate planning and policymaking at global, national, and local levels, but they also need to be involved as advocates, partners, and stakeholders to promote women’s rights and benefits in climate policy and action. That nearly two-thirds of NDCs submitted to date still do not address gender equality – despite decades of gender mainstreaming – indicates the critical need for a new approach if we are to meet the two degrees climate target.

Conclusion

Much has been written on the successes and failures of gender mainstreaming in international policy. Even though as a strategy it has been largely adopted around the globe, progress is uneven and inequalities persist. Scholars and development practitioners have become increasingly doubtful that gender mainstreaming as it has been applied to date will produce transformational change on its own. Rather, evidence shows that over the years gender mainstreaming has become largely depoliticised, with much rhetoric about ‘gender equality’ and ‘women’s empowerment’ but little evidence of action (Mukhopadhyay Citation2014).

Our analysis of INDCs, NDCs, and NAPs found an over-emphasis on women as vulnerable victims of climate change, and passive recipients of aid. It is critical to move beyond this perspective, to acknowledge women’s knowledge, capacity, and agency to adapt, mitigate, and respond to climate change. This can involve recognising the value of women’s local environmental and ethnobotanical knowledge for adaptation and disaster response, and involving them in decision-making and planning around disaster preparedness and recovery (Charan et al. Citation2016; Dankelman Citation2010). Their participation in local resource management bodies allows them to assert their rights and voice; it has also resulted in improved and sustainable resource management (Ouédraogo et al. Citation2018).

It is time for a ‘complex inequalities’ (Kuhn Citation2020) approach which recognises that women’s and men’s climate vulnerabilities vary according to gender, but also ethnicity, religion, class, and age conditions. Intersectional dynamics affect women as they adapt to the impact of climate change and seek to survive climate crises (Huyer et al. Citation2020). For example, rural women differ by gender, class, household headship, age, and stage of life simultaneously. These shape their access to water, forestland, and credit, and in turn their ability to adapt to climate-related drought (Huynh and Resurrecion Citation2014).

Working closely with national and regional women’s organisations as a platform for implementing gendered climate policy is another important avenue. Women’s organisations should be considered equal partners in decision-making and implementation, on climate finance bodies or energy boards for example, or as avenues for women to express and act on their climate priorities (Raty and Carlsson-Kanyama Citation2009; UNDP Citation2016).

Mitigation of climate change is an area where women are very much absent, except as providers of labour for carbon reduction programmes. Much more work needs to be done to support women’s agroforestry activities in low-carbon frameworks. The under-counted role of women in farming globally needs to be further explored in relation to reduction of greenhouse gases (see Fletcher Citation2017). Green energy policies and initiatives need to consult with and bring women in as professionals (Mohideen Citation2018), entrepreneurs (Shankar et al. Citation2015), and maintenance technicians, as well as energy users (EIGE Citation2012) and decision-makers.

Finally, the UNFCCC Gender Action Plan and the LWPG mandate monitoring of the implementation of gender across climate actions (UNFCCC Citation2019). This needs to be done through transparent and accountable processes of gender budgeting and comprehensive impact assessment and monitoring.

The UNFCCC Gender Action Plan marks a turning point for gender in climate policy and action, but only if it is implemented in a way that is transformative, by confronting structural gender inequalities. This will be done only if there is a shift away from designing strategies that aim at catering to the different needs of women and men to those that seek to challenge and transform gender relations and power imbalances between men and women, enabling them to take their own action (Huyer et al. Citation2020; Resurrection et al. Citation2019).

Acknowledgement

This work was implemented as part of the CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS), which is carried out with support from the CGIAR Trust Fund and through bilateral funding agreements. For details please visit https://ccafs.cgiar.org/donors. The views expressed in this document cannot be taken to reflect the official opinions of these organizations.

Notes on contributors

Sophia Huyer is Gender and Social Inclusion Leader, CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security; Women in Global Science and Technology (WISAT); International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI). Postal address: 204 Ventress Road, Brighton, ON K0K 1H0, Canada. Email: [email protected]

Mariola Acosta is a PhD candidate at the Strategic Communication Group, Wageningen University and Research Centre; International Centre for Tropical Agriculture. Email: [email protected]

Tatiana Gumucio was a Postdoctoral Research Scientist at the International Research Institute for Climate and Society, Columbia University. She is now based at Pennsylvania State University. Email: [email protected]

Jasmin Irisha Jim Ilham is a graduate student in the MA Climate and Society programme at Columbia University. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 According to the UNFCCC, global warming is likely to reach 1.5°C if not beyond (2.0°C) between 2030 and 2052. This is expected to increase the risk of heatwaves, heavy rainfall events, crop productivity decline, reduction in water availability, undernutrition, habitat losses, and others (IPCC Citation2018), and the effects get significantly worse at 2°C. The world has already witnessed about 1°C of temperature rise and is on track to 1.5°C by 2030. Some projections put the world on track to four degrees of warming (www.wri.org/blog/2018/10/according-new-ipcc-report-world-track-exceed-its-carbon-budget-12-years, last checked 30 November 2020).

2 Gender issues were not significantly integrated into UNFCCC decisions until the 2000s, and a ‘Gender Action Plan’ was not established until 2017 (UNFCCC Citation2017).

3 The Kenya NAMA has been submitted and is in process of finalisation.

4 NAPAs are the precursors of, and have been superseded by, NAPs.

5 This reflects similar findings of an analysis in January 2018 of nine NAPs by Daze and Denkens (Citation2018).

6 Tatiana Gumucio and Jasmin Irisha Jim Ilham.

7 Bangladesh, Cambodia, Haiti, Kenya, Mozambique, Nigeria, Panama, Peru, Tanzania, and Zambia.

8 PPPs are defined as a ‘a long-term contract between a private party and a government entity, for providing a public asset or service, in which the private party bears significant risk and management responsibility, and remuneration is linked to performance’ (World Bank Citation2018). See https://pppknowledgelab.org/.

9 See Huyer et al. (Citation2020) for an analysis of gender in/equality in relation to climate change.

References

- AAS (2012) Building coalitions, creating change: an agenda for gender transformative research in development (No. AAS-2012-31). CGIAR Research Program on Aquatic Agricultural Systems

- Acosta, Mariola, Fanny C. Howland, Jennifer Twyman, and Jean François Le Coq (2019) Gender inclusion in the Policies of Agriculture, Climate Change, Food Security and Nutrition in Honduras and Guatemala, Copenhagen: CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS)

- Acosta, Mariola, Osana Bonilla Findji, Fanny Cecile Howland, Jennifer Twyman, Tatiana Gumucio, Deissy Martínez Barón, and Jean François Le Coq (2020a) Step-by-step Process to Mainstream Gender in Climate-Smart Agricultural Initiatives in Guatemala, Wageningen: CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS), https://cgspace.cgiar.org/handle/10568/103254

- Acosta, Mariola, Margit van Wessel, Severine van Bommel, Edidah L. Ampaire, Laurence Jassogne, and Peter H. Feindt (2020b) ‘The power of narratives: explaining inaction on gender mainstreaming in Uganda’s climate change policy’, Development Policy Review 38: 6. doi:10.1111/dpr.12458

- Alston, Margaret (2014) ‘Gender mainstreaming and climate change,’, Women’s Studies International Forum 47: 287–94. doi:10.1016/j.wsif.2013.01.016

- Ampaire, Edidah, Mariola Acosta, Sophia Huyer, Ritah Kigonya, Perez Muchunguzi, Rebecca Muna, and Laurence Jassogne (2020) ‘Gender in climate change, agriculture, and natural resource policies: insights from East Africa’, Climatic Change 158(1): 43–60. doi:10.1007/s10584-019-02447-0

- Arora-Jonsson, Seema (2011) ‘Virtue and vulnerability: discourses on women, gender and climate change’, Global Environmental Change 21(2): 744–51. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.01.005

- Arwida, Shinta Dian, Cynthia Dewi Maharani, Bimbika Sijapati Basnett, and Anastasia Lucy Yang (2017) Gender Relevant Considerations for Developing REDD+ Indicators: Lessons Learned for Indonesia, CIFOR, https://www.cifor.org/knowledge/publication/6398/ (last checked 30 November 2020)

- Bock, S., R. Drexel, S. Gabizon, A. Samwel, and S. Bock (2015) Access to Affordable Low-Cost Solar Water Heating Solutions as a Basis for the First Gender-Sensitive Nationally Appropriate Mitigation Action (NAMA) in Georgia, Utrecht: Women in Europe for a Common Future (WECF)

- Brouwers, Ria (2013) Revisiting gender mainstreaming in international development: Goodbye to an illusionary strategy (Working Paper No. 556), The Hague: International Institute of Social Studies of Erasmus University Rotterdam (ISS), 1–36

- Chanana, Nitya and Shehnab Sahin (2018) A top-down approach for gender empowerment in Nepal, https://ccafs.cgiar.org/news/top-down-approach-gender-empowerment-nepal#.XegG3C0ZM0o (last checked 4 December 2019)

- Charan, Dhrishna, Manpreet Kaur, and Priyatma Singh (2016) ‘Indigenous Fijian women’s role in disaster risk management and climate change adaptation’, Pacific Asia Inquiry 7: 1

- Dankelman, Irene (2010) ‘Introduction: exploring gender, environment, and climate change’, in Irene Dankelman (ed.) Gender and Climate Change: An Introduction, London: Routledge, 1–20

- Dazé, Angie and Julie Dekens (2018) Towards Gender-Responsive National Adaptation Plan (NAP) Processes: Progress and Recommendations for the Way Forward, Winnipeg: International Institute for Sustainable Development. www.napglobalnetwork.org

- Denton, Fatima (2002) ‘Climate change vulnerability, impacts, and adaptation: why does gender matter?’, Gender and Development 10(2): 10–20

- European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE) (2012) Gender Equality and Climate Change, Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union

- FAO, WFP, and IFAD (2019, May 8) “UN food agencies step up joint efforts to tackle rural gender inequalities”, http://www.fao.org/news/story/en/item/1193249/icode/ (last checked 30 November 2020)

- Fisher, Susannah and Rachel Mohun (2015) Low carbon resilient development and gender equality in the least developed countries. (IIED Issue Paper), https://pubs.iied.org/pdfs/10117IIED.pdf (last checked 30 November 2020)

- Fletcher, Amber J. (2017) ‘Maybe tomorrow will be better: gender and farm work in a changing climate’, in M. G. Cohen (ed.) Climate Change and Gender in Rich Countries: Work, Public Policy and Action, pp. 185–198. Abingdon, Oxon; New York, NY: Routledge

- Gay-Antaki, Miriam and Diana Liverman (2018) ‘Climate for women in climate science: women scientists and the intergovernmental panel on climate change’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115(9): 2060–65. doi:10.1073/pnas.1710271115

- Gumucio, Tatiana and Mariana Tafur Rueda (2015) ‘Influencing gender-inclusive climate change policies in Latin America’, Journal of Gender, Agriculture and Food Security 1(2): 42–61

- Holvoet, Nathalie and Liesbeth Inberg (2014) ‘Gender sensitivity of sub-Saharan Africa national adaptation programmes of action: findings from a desk review of 31 countries’, Climate and Development 6(3): 266–76. doi:10.1080/17565529.2013.867250

- Huyer, Sophia, Tatiana Gumucio, Katie Tavenner, Mariola Acosta, Nitya Chanana, Arun Khatri-Chhetri, Catherine Mungai, Mathieu Ouedraogo, Gloria Otieno, Maren Radeny, and Elisabeth Simelton (2020) ‘From vulnerability to agency: gender equality in climate adaptation and mitigation’, in R. Pyburn and A. Van Eerdewijk (eds.) Advancing Gender Equality Through Agricultural and Environmental Research: Past, Present and Future, 61–72. Washington, DC: IFPRI

- Huynh, Phuong T. A. and Bernadette P. Resurreccion (2014) ‘Women’s differentiated vulnerability and adaptations to climate-related agricultural water scarcity in rural Central Vietnam’, Climate and Development 6(3): 226–37. doi:10.1080/17565529.2014.886989

- IPCC (2014) ‘Summary for policy makers’, in L. L. W. Field, C. B. V. R. Barros, D. J. Dokken, K. J. Mach, M. D. Mastrandrea, T. E. Bilir, M. Chatterjee, K. L. Ebi, Y. O. Estrada, R. C. Genova, B. Girma, E. S. Kissel, A. N. Levy, S. MacCracken, and P. R. Mastrandrea (ed.) Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability – Contributions of the Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report, Cambridge, UK, 1–32. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2009.11.012

- IPCC (2018) Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty, Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, H.-O. Pörtner, D. Roberts, J. Skea, P.R. Shukla, A. Pirani, W. Moufouma-Okia, C. Péan, R. Pidcock, S. Connors, J.B.R. Matthews, Y. Chen, X. Zhou, M.I. Gomis, E. Lonnoy, T. Maycock, M. Tignor, and T. Waterfield (eds.) Geneva: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

- IPCC (2019) Report from the IPCC Task Group on Gender. Forty-Ninth Session of the IPCC Kyoto, Japan, 8 – 12 May 2019. IPCC-XLIX/Doc. 10, Rev.1 (11.V.2019), Geneva: IPCC Secretariat

- IPCC (2020) Gender Policy and Implementation Plan, Geneva: IPCC, https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2020/05/IPCC_Gender_Policy_and_Implementation_Plan.pdf, (last checked 30 November 2020)

- IUCN (2019) Strengthening gender-responsive climate action, https://genderandenvironment.org/resource/strengthening-gender-responsive-climate-action/

- Kantor, Paula, Miranda Morgan, and Afrina Choudhury (2015) ‘Amplifying outcomes by addressing inequality: the role of gender-transformative approaches in agricultural research for development’, Gender, Technology and Development 19(3): 292–319. doi:10.1177/0971852415596863

- Ketting, Maria (2017) Gender transformative approaches in agriculture, food and nutrition security: The EU’s approach | capacity4dev.eu, https://europa.eu/capacity4dev/hunger-foodsecurity-nutrition/discussions/gender-transformative-approaches-agriculture-food-and-nutrition-security-eus-approach-1 (last checked 31 January 2019)

- Kuhn, Heike (2020) ‘Reducing inequality within and among countries: realizing SDG 10—a developmental perspective’, in M. Kaltenborn, M. Krajewski, and H. Kuhn (eds.) Sustainable Development Goals and Human Rights, Cham: Springer International Publishing, 137–53

- MacGregor, Sherilyn (2010) ‘‘Gender and climate change’: from impacts to discourses’, Journal of the Indian Ocean Region 6(2): 223–38. doi:10.1080/19480881.2010.536669

- Mason-D’Croz, Daniel, Joost Vervoort, Amanda Palazzo, Shahnila Islam, Steven Lord, Ariella Helfgott, Petr Havlík, Rathana Peou, Marieke Sassen, Marieke Veeger, Arnout van Soesbergen, Andrew P. Arnell, Benjamin Stuch, Aslihan Arslan, and Leslie Lipper (2016) ‘Multi-factor, multi-state, multi-model scenarios: exploring food and climate futures for Southeast Asia’, Environmental Modelling & Software 83: 255–70. doi:10.1016/j.envsoft.2016.05.008

- Mohideen, Reihana (2018) Energy technology innovation in South Asia: implications for gender equality and social inclusion. ADB South Asia Working Paper Series 61, Asian Development Bank doi:10.22617/WPS179175-2

- Moser, Caroline and Annalise Moser (2005) ‘Gender mainstreaming since Beijing: a review of success and limitations in international institutions’, Gender & Development 13(2): 11–22. doi:10.1080/13552070512331332283

- Mukhopadhyay, Maitrayee (2014) ‘Mainstreaming gender or reconstituting the mainstream? Gender knowledge in development’, Journal of International Development 26(3): 356–67. doi:10.1002/jid.2946

- Namuloki, Josephine (2017) ‘MPs Reject Long Awaited Climate Change Bill’, The Observer, 6 December. https://observer.ug/news/headlines/56323-mps-reject-long-awaited-climate-change-bill.html (last checked 30 November 2020)

- Natai, Shakwaanande, Madaka Tumbo, Winifred Masiko, and Henry Mahoo (2019) ‘Tanzania’s female parliamentarians to mainstream gender in climate adaptation’, CCAFS Blog

- Nhamo, Godwell (2014) ‘Addressing women in climate change policies: a focus on selected east and southern African countries’, Agenda 28(3): 156–67

- Nhamo, Godwell and Senia Nhamo (2018) ‘Gender and geographical balance: with a focus on the UN secretariat and the intergovernmental panel on climate change’, Gender Questions 5(1 SE-Articles). doi:10.25159/2412-8457/2520

- Okali, Christine and Lars Otto Naess (2013) Making sense of gender, climate change and agriculture in sub-Saharan Africa: creating gender responsive climate adaptation policy. Working Paper 057, Future Agriculture Consortium

- Okiror, John Francis (2016) ‘Informing policies with evidence: gender, climate change, and food security in Uganda’, CGIAR, CCAFS, 9 September, https://ccafs.cgiar.org/news/informing-policies-evidence-gender-climate-change-and-food-security-uganda (last checked 4 December 2019)

- Ouédraogo, Mathieu, Samuel T. Partey, Robert B. Zougmoré, Mavis Derigubah, Diaminatou Sanogo, Moussa Boureima, and Sophia Huyer (2018) Mainstreaming Gender and Social Differentiation Into CCAFS Research Activities in West Africa: Lessons Learned and Perspectives, Wageningen: CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS), https://ccafs.cgiar.org/publications/mainstreaming-gender-and-social-differentiation-ccafs-research-activities-west-africa#.XdhFgS0ZOu4 (last checked 30 November 2020)

- Pham, Phuong, Philippe Doneys, and Donna L. Doane. (2016) ‘Changing livelihoods, gender roles and gender hierarchies: the impact of climate, regulatory and socio-economic changes on women and men in a Co Tu community in Vietnam’, Women’s Studies International Forum 54: 48–56. doi:10.1016/j.wsif.2015.10.001

- Porter, Fenella and Caroline Sweetman (eds.) (2005) Mainstreaming Gender in Development: A Critical Review, Oxford: Oxfam GB

- Raczek, Tracy, Eleanor Blomstrom, and Cate Owren (2010) ‘Climate change and gender: policies in place’, in I. Dankelman and W. Jansen (eds.) Gender and Climate Change: An Introduction, London: Earthscan, 194–211

- Räty, Riitta and Annika Carlsson-Kanyama (2009) Comparing Energy Use by Gender, Age, and Income in Some European Countries, Stockholm: Total Defense Research Institute

- Republic of Benin (2018) Benin’s First Nationally Determined Contribution Under Paris Agreement, Cotonou: Ministry of Living Conditions and Sustainable Development

- Resurrección, Bernadette P. (2013) ‘Persistent women and environment linkages in climate change and sustainable development agendas’, Women’s Studies International Forum 40: 33–43. doi:10.1016/j.wsif.2013.03.011

- Resurrección, Bernadette P., Beth A. Bee, Irene Dankelman, Clara Mi Young Park, Mousumi Halder, and Catherine P. McMullen (2019) Gender-Transformative Climate Change Adaptation: Advancing Social Equity. Background paper to the 2019 report of the Global Commission on Adaptation, Rotterdam and Washington, DC

- Shankar, Anita V., Mary Alice Onyura, and Jessica Alderman (2015) ‘Agency-based empowerment training enhances sales capacity of female energy entrepreneurs in Kenya’, Journal of Health Communication 20(Suppl. 1): 67–75. doi:10.1080/10810730.2014.1002959

- Terry, Geraldine (2009) ‘No climate justice without gender justice: an overview of the issues’, Gender & Development 17 (1): 5–18. doi:10.1080/13552070802696839

- The State of Eritrea (2018) Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) Report to UNFCCC, Asmara: Ministry of Land, Water and Environment

- Tiessen, Rebecca (2007) Everywhere/Nowhere: Gender Mainstreaming in Development Agencies, Bloomfield, CT: Kumarian Press

- UN Conference on Environment and Development (1992) Agenda 21, Rio Declaration, Forest Principles, New York: United Nations

- UNCSD (2012) Rio+20 declaration – “The Future We Want” (UN document A/66/L.56), https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/LTD/N12/436/88/PDF/N1243688.pdf?OpenElement (last checked 30 November 2020)

- UNDP (2016) Gender Equality in National Climate Action: Planning for Gender-Responsive National Determined Contributions (NDCs), New York: UNDP, http://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/librarypage/womens-empowerment/gender-equality-in-national-climate-action–planning-for-gender-.html (last checked 30 November 2020)

- UNFCCC (2001) Decision 36/CP.7 of FCCC/CP/2001/13/Add.4 – Improving the participation of women in the representation of Parties in bodies established under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change or the Kyoto Protocol

- UNFCCC (2012) Decision 23/CP.18 of FCCC/CP/2012/8/Add.3 – Promoting gender balance and improving the participation of women in UNFCCC negotiations and in the representation of Parties in bodies established pursuant to the Convention or the Kyoto Protocol

- UNFCCC (2014) (Decision 18/CP.20) of FCCC/CP/2014/10/Add.3 – Lima Work Program on Gender

- UNFCCC (2015) Decision 1 /CP.21 of FCCC/CP/2015/10/Add.1 – The Paris Agreement

- UNFCCC (2017) Decision 3/CP.23 of FCCC/CP/2017/11/Add.1—Establishment of a gender action plan

- UNFCCC (2019) Gender composition. Report by the secretariat (2019) (p. 12). UNFCCC

- United Nations (1995) Beijing declaration and platform of action, adopted at the fourth world conference on women, 27 October 1995, https://www.refworld.org/docid/3dde04324.html (last checked 12 July 2020)

- UN Women (2019) Progress on the Sustainable Development Goals. The Gender Snapshot 2019, New York: UN Women and UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs

- Wang, Yiting and Catherine Corson (2015) ‘The making of a ‘charismatic’ carbon credit: clean cookstoves and ‘uncooperative’ women in western Kenya’, Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 47(10): 2064–79

- WECF (2019) Gender Just Climate Solutions. Women and Gender Constituency. 5th ed., http://womengenderclimate.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/GJCS-2019-eng.pdf (last checked 30 November 2020)

- World Bank (2018) ‘What are Public-Private Partnerships?’ https://ppp.worldbank.org/public-private-partnership/overview/what-are-public-private-partnerships (last checked 30 November 2020)