ABSTRACT

The pandemic has radically shifted how society is organised, with increased work from home, home-schooling, and intensification of online presence, all with specific (un)intended implications on paid and unpaid care work. These implications, like those of other crises, are gendered and manifest along sex, age, disability, ethnicity/race, migration status, religion, social class, and the intersections between these inequalities. While many studies have identified these unequal and negative impacts, and point to significant care-related inequalities, the specific contribution of this paper is a different one, namely to point towards inspiring practices as better stories of and in the care domain during the pandemic. The aim is to make these better stories visible and to think about these as ways forward to mitigate the unequal impacts of COVID-19 and its policy responses. Theoretically, the approach is based on ‘better stories’, as developed by Dina Georgis (2013, Better Story. Queer Affects from the Middle East, New York: State University). The paper uses both quantitative and qualitative data, gathered from the EU27, Iceland, Serbia, Turkey, and the UK, within the EU H2020 project RESISTIRÉ.

La pandémie a fait radicalement évoluer la manière dont la société est organisée, avec l'augmentation du télétravail, de l'enseignement à domicile et de l'intensification de la présence en ligne, le tout avec des implications spécifiques (im)prévues pour le travail de soins rémunéré et non rémunéré. Ces implications, comme celles d'autres crises, sont genrées et sont différentes selon le sexe, l'âge, les handicaps, l'ethnie/la race, le statut migratoire, la religion, la classe sociale, et les intersections entre ces inégalités. Si de nombreuses études ont identifié ces impacts inégaux et négatifs, et signalent de considérables inégalités sur le plan des soins, la contribution spécifique du présent article est différente, à savoir : orienter le lecteur vers des pratiques inspirantes afin de proposer des récits plus positifs sur les soins durant la pandémie. L'objectif est d'accroître la visibilité de ces récits plus positifs et de les voir comme des manières d'aller de l'avant afin d'atténuer les impacts inégaux du Covid-19 et des réponses en matière de politiques que la pandémie a suscitées. En théorie, cette approche se fonde sur des « récits plus positifs » (better stories), concept mis au point par Dina Georgis (2013). Cet article utilise des données factuelles quantitatives et qualitatives, recueillies dans les pays de l'UE-27 et en Islande, en Serbie, en Turquie et au Royaume-Uni, dans le cadre du projet RESISTIRÉ UE H2020.

La pandemia ha cambiado radicalmente la forma en que se organiza la sociedad. Ello se ha reflejado en el aumento del trabajo desde casa, la educación en el hogar y la intensificación de la presencia personal en línea, todo lo cual conlleva implicaciones específicas (no previstas) para el trabajo de cuidados remunerado y no remunerado. Estas implicaciones, al igual que las de otras crisis, tienen carácter de género y se manifiestan en función del sexo, la edad, la discapacidad, la etnia/raza, la situación migratoria, la religión, la clase social y las intersecciones entre estas desigualdades. Aunque muchos estudios han identificado estos efectos desiguales y negativos, y señalan la existencia de importantes desigualdades relacionadas con los cuidados, la contribución específica de este artículo es otra: dar cuenta de prácticas inspiradoras como mejores historias de y en el ámbito de los cuidados durante la pandemia. El objetivo es hacerlas visibles y pensar en ellas como formas de mitigar los impactos desiguales de la COVID-19 y sus respuestas que se han dado a nivel de políticas públicas. Desde el punto de vista teórico, el enfoque se basa en las “mejores historias”, desarrolladas por Dina Georgis (2013). El artículo utiliza datos cuantitativos y cualitativos, recogidos en la UE27, Islandia, Serbia, Turquía y el Reino Unido, como parte del proyecto H2020 RESISTIRÉ, patrocinado por la UE.

Introduction

The pandemic is more than a health crisis; it is a human, economic, and social crisis, affecting people, societies, and economies at their core. It has brought to light the critical role of the care work performed by women, whether as paid and unpaid care providers/workers, formal and informal care providers/workers, as well as teachers and more or less all workers in the health, social, and education sectors (Dugarova Citation2020; International Labour Office (ILO) Citation2018; Wenham et al. Citation2020).

The pandemic and its political and societal responses have not only further entrenched, expanded, and exacerbated pre-pandemic gendered and intersectional inequalities, it has also created new inequalities, revealing the deep-rooted nature of gender inequality (Axelsson et al. Citation2021). The impacts, like those of other crises, are gendered and manifest along sex, age, disability, ethnicity/race, migration status, religion, social class, and the intersections between these inequalities (Lokot and Avakyan Citation2020; Walby Citation2015; Walter and McGregor Citation2020). However, the crisis also provides an opportunity to build back better by putting care and social reproduction at the centre of social change, and challenge gendered and intersectional power relations. To do so, there is an urgent need to identify inspiring policy and societal responses that enable (a better) recovery.

The paper identifies these responses – analysed as ‘better stories’ (Georgis Citation2013) – within the domain of care and care work in Europe. It includes an analysis of how gender roles in households contribute to a disproportionate allocation of care work to women, in turn increasing other inequalities. Care work includes direct and personal relational care, and indirect care (cooking, cleaning). Care work can be paid or unpaid, and in the formal or informal economy. Most care workers are women, frequently migrants and working in the informal economy under poor conditions and for low pay (ILO Citation2018, 1). Typical concerns at individual and societal levels problematised in relation to this domain are the dynamics between unpaid and paid care work, the gendered consequences of closures of child-care facilities and schools, the harsh working conditions for health-care workers, and the tendency to take women's care work for granted in policymaking (Axelsson et al. Citation2021; Cibin et al. Citation2021). The COVID-19 lockdowns forced people to stay at home and resulted in the closure of many care facilities, which strongly impacted people with care responsibilities – mostly women – whether it be for children, elderly people, people living with a disability, and/or others (UN Citation2020). Given that the organisation of care work is gendered, these policy responses affect men and women differently and unequally, often exacerbating the gender care gap as women took up (even) more care work (Stovell et al. Citation2021). The gender pay gap contributed to this trend. As women tend to earn lower wages and more often work part-time compared with men, they have been more likely to (have to) give up or reduce their paid work to sustain the increased care duties placed on them by families and households (Stovell et al. Citation2021). In some countries, women's family care allowance leave doubled during the pandemic (Stovell et al. Citation2021). In other cases, men increased their contributions to child care at roughly the same rate as women. But due to the pre-pandemic gender care gap, where women already carried out considerably more child care in absolute terms, women's contributions grew proportionally more than men's and the gender care gap increased (Stovell et al. Citation2021). Further, in some countries where the proportion of fathers’ involvement in child care initially increased (by 10 per cent to 31 per cent, between April and June 2020), the proportion later decreased: by September the same year it had decreased to 23 per cent and in November it reduced further still, to 18 per cent – 3 per cent below the original 21 per cent (Stovell et al. Citation2021).

While the pandemic can be represented to be a crisis across multiple policy domains, this paper conceptualises the pandemic as a care crisis, where substantial evidence shows that women disproportionally have worked, both paid and unpaid, while maintaining basic life-sustaining functions in relation to all forms of care, e.g. child care, elderly care, and caring for people with disabilities. The pandemic has in a devastating way shown the importance of care for the sustainability of life.

For good reasons, much of the COVID-19-related research has focused on exposing these increased inequalities and shown how Europe and elsewhere are witnessing a reversal of gender and intersectional equality, with increased levels of gender-based violence against women and girls, traditionalisation of gender roles and norms, and a strengthening of gendered stereotypes. However, we have simultaneously witnessed how (civil) societal initiatives, community alliances, and employers’ resourcefulness mitigate these impacts and inequalities. Hence, despite the darkness in which we may find ourselves, to paraphrase Hanna Arendt, we are also witnessing promising practices, good examples, and better stories, and ‘there is always a better story than the better story’ (Georgis Citation2013). Although these stories are located in deeply different and gender unequal contexts, they can be used to carve spaces of hope and pave the way for more gender equitable outcomes.

Against this background, the aim of the paper is to identify and make visible some of the better stories related to care during the pandemic. Making these visible and known can in itself contribute to ways of mitigating the unequal impacts of COVID-19 and its policy responses on care. While many studies have identified and point to increased care inequalities, our specific contribution here is to uncover and point towards the inspiring practices and better stories of the pandemic, with the overall objective to suggest ways forward. Methodologically, the paper is based on material from RESISTIRÉ: Responding to Outbreaks Through Co-creative Sustainable and Inclusive Equality Strategies (2021–2023)Footnote1 an EU-funded project involving ten partners from across Europe, which explores the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on behavioural, social, and economic inequalities in Europe. It includes a plethora of better stories from the individual, organisational, and societal levels from Austria, the Basque Region, Belgium, Bulgaria, France, Finland, Germany, Hungary, Iceland, Italy, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Serbia, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden, Turkey, and the UK.

In the following section, we first elaborate on the theoretical and methodological approach used in the project and, subsequently, the paper. Second, we describe the methods and material employed. Thereafter, we present the results and the analysis, including the better stories in the form of policy and civil society initiatives to mitigate the effects of COVID-19. Each section ends with a recommendation. The paper ends with conclusions on better stories, including ‘the better, better’ stories.

Methodology

Theoretically, the paper draws on a gender+ perspective (Verloo Citation2007), intersectionality (Hankivsky and Kapilashrami Citation2020; Verloo Citation2013; Walby et al. Citation2012), and better stories (Georgis Citation2013).

Gender+ means gender is conceptualised as always intersecting with and as shaped by other inequalities and social categories (Verloo Citation2006, Citation2007, Citation2013; see also Bustelo Citation2017; Lombardo et al. Citation2017). While gender is seen as an organising principle, and as the central reference point which allows other inequalities to be located (Risman Citation2004), gender is analysed as mutually shaping and shaped by class, age, disability, and other inequalities (Walby et al. Citation2012). The gender+ approach recognises intersections of gender with age, race, ethnicity, class, disability, and sexuality as likely to be particularly significant in the analysis of impact of COVID-19 policy responses on inequality (Hankivsky et al. Citation2014; Lokot and Avakyan Citation2020). The paper uses the concept of better story, as developed by feminist scholar Dina Georgis (Citation2013), who argues that there is always a better story than the better story, and proposes ‘story’ as a method for social inquiry and a tool to access and understand how political histories get written. To search for and identify better stories in policy and societal responses requires us to analyse critically the ways in which our stories are shaped by the personal and political (Altınay Citation2019), and how these are responses to political and societal urgencies, or indeed, crises. Georgis (Citation2013, 1) writes: ‘every story is the better story, or the best possible story we have invented to allow ourselves to go on living’, and ‘“Better” captures not the hierarchy of cultural expression, but rather, what is possible’ (ibid., 2). While there certainly are stories of extreme marginalisation, exhaustion, and devastation in the lives of women across Europe, there are simultaneous better stories with the potential for transformative change at the individual level, which may indeed be picked up by or spill over to the community level, if supported by policies. In the paper, we use the concept to identify and make visible some of the undoubtedly multitude of better stories, and better ways of responding to the care crisis. While we certainly make no claim to be exhaustive, or to have identified the ‘best’ stories (‘there is always a better story than the story’), our aim is rather to pick up and share some of these better stories from across Europe and analyse them in order to suggest ways forward – and to allow ourselves to find some light in the darkness.

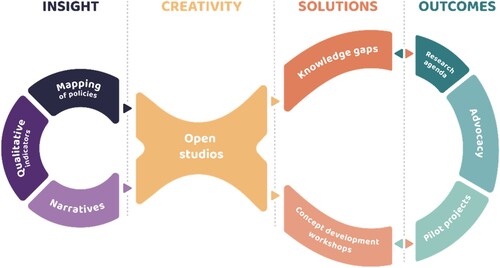

The material used includes qualitative and quantitative data collected by 31 national researchers in the EU27, Iceland, Serbia, Turkey, and the UK in 2021, analysed using co-creative and solution-driven methods inspired by design thinking (Boyer Citation2011).Footnote2 Co-creative design thinking seeks to involve and improve the users’ experience to make policy inclusive, efficient, and sustainable. It also challenges the way policies are usually developed and delivered which is a top-down process. Instead, it employs a participatory bottom-up approach involving representatives across sectors. Concretely, it means that stakeholders and end-users have been involved throughout the entire design process of the project. Overall, this process has consisted of four interrelated steps (research insight, creativity, solutions, outcomes) repeated in three cycles throughout the duration of the project. Each step and cycle feed into the subsequent steps and cycles (see ). The first step constituted research and insights stemming from desk research, field work, Rapid Assessment Surveys, policy mapping exercises, and narrative interviews. Thirty-one national-level researchers conducted desk research and fieldwork, including an extensive mapping of policy and societal responses to COVID-19 (n = 575), analysed Rapid Assessment Surveys (n = 310), and conducted narrative interviews with vulnerable groups (n = 188). These materials were used to analyse the economic, social, and environmental impacts of COVID-19, with a specific focus on the lived experiences of marginalised groups and inequalities.

Borrowing the terminology used within the design field, the RESISTIRÉ project's structure can be similarly defined as a process of ‘Research Through Design’ (e.g. Gaver Citation2012; Stappers and Giaccardi Citation2017). As we have seen above, there is a continuous interaction between the objective of producing an output, in our case recommendations for policymakers and other stakeholders, and the process of collecting and analysing empirical data to support the construction of this output. The problems and better stories identified by research in the first step were used in the second step, creatively, where responses were developed in so-called ‘Open Studios’. These constitute a co-design approach, bringing together multiple, different experts and stakeholders, including the user experience (Boyer et al. Citation2006). During the Open Studios, the participants were presented with personas to stimulate creativity, create empathy, and to take some distance from the personal experience of the participants. These personas were based on the research insights and profiles of different archetypes of people who were affected by the pandemic in one way or another. ‘Better stories’ are used as inspiration, stories that identify how a given (negative) societal situation can be ameliorated to improve on existing practices, without being a perfect fix that turns out to be unattainable (i.e. a ‘best story’). The set of recommendations we suggest were produced co-creatively by researchers and stakeholders within co-design contexts of the Open Studios, in which the better stories described are the result of meticulous research work (Axelsson et al. Citation2021; Cibin et al. Citation2021; Stovell et al. Citation2021; Živković et al. Citation2021, Citation2022). The third step, solutions, included the construction of operational recommendations and the launch of pilot actions to understand the potential impact of a range of proposed solutions. The fourth step, outcomes, exemplified by this paper, includes a presentation of the results to guide stakeholders who might want to employ these learnings. The paper utilises the results of each of the four steps, taken in the first of three cycles, where cycle two has just started. The four steps will be repeated in cycle two and in cycle three. The next section presents some of the many better stories identified by research and the co-creative process.

The better stories of policies and civil society initiatives in the crisis

We turn to examples of these ‘better stories’ of policies and societal initiatives related to care across Europe during the pandemic. They are thematically categorised as the following: recognising the complex nature of work, creating caring workspaces, expanding care facilities, better care leave policies, and men's contribution to child care. Each set of better stories is followed by short recommendations.

Recognising the complex and multifaceted nature of work

Various policies and civil society initiatives have focused on recognising the complex and multifaceted nature of work. In Spain and Sweden, a policy to induce a work–life balance enabled a reduction of working hours for employees who had to care for family members due to COVID-19. Some Spanish regional governments went further and provided economic compensation for any loss of income due to increased care-related work. The Swedish government introduced temporary financial compensation for those who have had to give up work or reduce their working hours, to avoid infecting a close relative who is part of a risk group for COVID-19. In Spain's Basque Region, where families often rely on grandparents to take care of children outside school hours, parents found themselves devoid of support when elders became a risk group and had to socially distance themselves. The regional government thus designed a measure to compensate families for the cost of hiring a worker to take care of children. This measure allowed women to get relief from child-care responsibilities and at the same time promoted the employment of child-care workers.

For particularly vulnerable groups, better care work also means contact, proximity support – that is, support in nearness and closeness in both time and space – and information. In Turkey, the Kamer Foundation works to identify local practices, in particular in the home context, of what the organisation describes as resulting from an existing gender order and sexist system that harms women and children, to develop alternatives, and enable their implementation. During the pandemic, it ensured that at least ten women were contacted on a daily basis to keep track of their needs. The women in question had previously approached the foundation with issues of gender-based violence, unemployment, and trouble reaching social assistance. Among the activities carried out was support to 240 families in spending quality time at home with their children aged between two and six years, proposing education methods that promote gender sensitivity and equality. In addition, the organisation provided consultancy to women on online education.

Another vulnerable group particularly impacted in their work during the pandemic was researchers with children. With the closing of research facilities, laboratories, and libraries, researchers’ situation was generally challenging, particularly for single parents. In Poland, employees associated with the trade union at the Polish Academy of Sciences, and Academy and Fine Arts in Warsaw called on the Minister of Education and Science to take into account the difficult situation of employees – particularly women employees – working in science and providing primary care for their children. Their request was to consider their situation in their work assessment (by including family situation in the employee assessment regulations); in the settlement of grants (by extending the time allocated for this task) and in the process of applying for new grants (by extending the period for which the scientific achievements are calculated); and in the evaluation of the work of the research units that employ them (by taking into account the number of employees with children).

In Portugal, the Equality Commission of University Beira Interior, an official body composed of teachers, workers, and students from all faculties working to promote equality between women and men in their institution, found a solution to address the negative impact of isolation on women's mental wellbeing. A virtual feminist space for discussion and deliberation called ‘Equality in Focus’ was created for students, which enabled the combating of negative effects of the COVID-19 lockdown measures. Two monthly online conferences were organised during 2020, enabling discussions and the sharing of experiences. The stories shared by the students defined the pillars of the lines of interventions later addressed by the Commission.

Another facet of work that we address is labour rights. The pandemic has highlighted how care work, often performed by migrant women, is generally based on precarious or informal work relationships that leave little room for social protection. However, the crisis has also been an opportunity for care workers to make their voices heard. In Austria, care workers hired by families are usually self-employed. However, neither the organisation of their working hours and workplace, nor the nature of their work are consistent with this type of contract, and should be formalised as a standard employment contract, which would secure their rights. The pandemic has also underscored how little protection from unemployment they have in times of crisis. In addition, the closure of borders made it difficult for these workers to return to their countries of origin. This situation pushed various care workers to unite with other activists and found together IG24, an association to represent their interests. IG24 succeeded in uniting care workers from Romania, Slovakia, Bulgaria, Croatia, and Hungary in demanding more rights and protection.

Recommendations to recognise the complex and multifaceted nature of work

Policies should not only consider formally compensated labour; unpaid work (care and domestic work) and paid but informal employment should also be recognised as ‘work’ (Hussmanns Citation2004; ILO Citation2018). At the same time, paid care and domestic work should be regulated through standard employment contracts that allow care workers to have the same rights as other employees. It is thus crucial to consider how work and labour market policies impact unpaid care work and informal care workers’ lives. Policies should specifically address the needs of people in unpaid and informal care work arrangements. These acknowledgements could favour a cultural shift to a new consideration of work and the workplace. Our better stories from civil society initiatives highlight the necessity of a cultural shift in very different contexts. They also point to how the pandemic – entailing even more difficult working conditions – has increased collective awareness as well as initial responses of support, particularly for vulnerable groups.

Caring workplaces

With the pandemic and the sudden switch to remote working, employees’ needs for a better work–life balance were brought into the spotlight. Many better stories of employers and NGOs who supported workers’ personal needs may be used as means of inspiration to rethink the workplace and make it generally more caring. Workers’ needs vary, of course, from one vulnerable group to another. In Hungary, a coalition of NGOs supporting various vulnerable groups who would not usually work together (people with disability, Roma, LGBTQI persons, etc.), joined forces to draw employers’ attention to their specific needs. In many countries, employers participated in supporting parents’ work–life balance during the pandemic by relieving their employees’ care burden. In the Netherlands, VodafoneZiggol provided up to seven extra vacation days for employees to look after their children. ‘SURF’, a co-operation of schools, universities, and research institutions, offered its employees a certain number of ‘corona hours’ for them to take care of their children, which they did not have to make up. Employees from law firm NautaDutilh with children were refunded for employing a babysitter at home, while Tilburg University maintained their employees’ full salary when their working hours decreased due to care responsibilities (Živković et al. Citation2021).

The increased child-care burden set aside, telework during the pandemic offered many workers a better work–life balance, with less time commuting, increased men's participation in household chores, and offered more flexibility. However, home does no't constitute a caring workplace for all. Telework can also create many difficulties, such as a blurred distinction between professional and private life, exposed and deepened digital inequalities, or a less-secure environment. Workers who work from home should also benefit from a caring workplace. With the generalisation of telework during lockdown, many policies aimed to protect workers’ rights, by limiting working hours, employers’ control on employees’ work, or by providing digital equipment and support. Spain introduced legislation on telework which ensured specific safeguards, such as equal treatment, non-discrimination in terms of teleworkers’ labour rights, prevention from isolation, and work-related online sexual harassment.

Recommendations to promote caring workplaces among employers

Workplaces should be caring, inclusive, taking into consideration the importance of employees’ work–life balance, and should support an equal division of care work within households. Practices and policies should thus include care work in employees’ working hours and promote a healthy balance between work and family responsibilities. We list a set of measures produced by the RESISTIRÉ project that can benefit both employees and employers. When workers have an increased sense of well-being, they are less likely to be absent or on sick leave, with subsequent positive benefits on their mental health. In fact, these policies will help enhance creativity and instil a greater sense of belonging and unity among workers/employees.

Caring workplace policies should concretely recognise that care work still happens after an employee's paid working hours, and therefore should promote a healthy division between labour at work and at home. This can be done by providing more flexibility to working hours and more control to employees to organise their duties. Caring workplace policies should recognise that most caring roles are unequal within households, and that care is a responsibility disproportionately covered by women in society. Therefore, mindful of this division of care roles within households, they should incentivise support for care hours and leave for male employees, and ensure that these hours are used by all workers, regardless of rank within a workplace. This equal treatment and redistribution of responsibilities should be highlighted and is key to ensuring and communicating that taking time off from work to care for others does not have a negative connotation within workplaces. Finally, caring workplace policies could focus on helping those with care responsibilities in delegating care. Offering employees details about local care institutions such as day-care facilities, retirement homes, hospices, and hospitals, as well as incentivising their use by giving employees structural (or financial) help, can directly encourage those with caring duties to use these services. Even more concretely, employers can create a connection between workplaces and caring facilities, as well as enable a more institutionalised recognition of the caring duties of workers, by establishing formal relationships and partnerships with these kinds of institutions.

The recognition of unpaid work as work has become even more crucial with the increased prevalence of telework. If female employees who carry the burden of domestic chores are to benefit from the opportunity provided by telework to bridge the gender equality gap in the labour market, they must be allowed more time for their unpaid work. Policies could encourage a fairer division of domestic and caring duties, by recognising a certain number of hours needed for domestic work, mapping workers’ personal needs, and integrating them in their teleworking hours, within a teleworking framework.

Furthermore, men's responsibilities in sharing unpaid care and domestic chores should also be incentivised by employers and included in telework arrangements, in line with ILO's recommendation for employers to promote family-friendly policies. Such policies that trust employees and recognise the role of care work in day-to-day life could create more equitable household divisions of labour and, potentially, push for cultural change around care work. To guarantee that the policy does not contribute to the perpetuation of traditional gender roles, the regulation of telework must be incorporated into companies’ equality plans. Policies should provide tools to avoid new forms of discrimination.

Expanding care facilities

Better-designed care policies and efficient care infrastructure allow employees to leave their loved ones in trusted care and focus on their work better. Many COVID-related policies aimed at providing workers of vulnerable groups or those working in essential sectors with day-care arrangements during school holidays (City of Ghent in Belgium) and providing free child-care services for young children by unemployed relatives, whether by choice or not, they were relatives ready to help with child care (Bulgarian Ministry of Labour and Social Policy). In Spain, the government of the region of Aragon launched a call for proposals to be funded, aimed at improving work–life balance and decreasing family conflicts in rural areas, with a focus on gender equality as a matter of social responsibility.

In Italy, measures providing parental leave and babysitting bonus supported parent workers as they faced the closure of schools. The needs of vulnerable groups like parents with children with disabilities were addressed with specific measures and a higher babysitting bonus was allotted for workers in health and emergency services sectors such as law enforcement agencies and civil protection. The majority of workers who benefited from parental leave were women – with a paid leave equal to 50 per cent of the salary, as most couples opted to keep the man's higher income. In Finland, when schools were closed, we find better stories of municipalities which provided children with lunches in the school premises, supporting families who lacked either time or financial resources to prepare everyday meals.

The needs of frontline care workers were in the spotlight during the pandemic and many volunteers were willing to help them with their household duties. They, however, did not know whom to contact. In Belgium, this gap was bridged by the ‘Help for Heroes’ platform. Volunteers were encouraged to sign up to help health-care workers with their care work inside the home by shopping or babysitting for them. Volunteers’ offers were then matched with health-care workers’ needs. Initiated by individuals, the platform was later structured within a non-profit organisation (vzw Resontant), supported by several private companies, involving specific health-care employers. In Hungary, another network was set up to specifically help families caring for children with disabilities with their groceries. In Poland, a grassroots initiative called ‘The Invisible Hand’ matches requests for support, such as care activities, with volunteers ready to help. Set up in March 2020 as a Facebook group, it now counts over 100,000 members.

Supporting children's educational activities during school closures certainly increased parents’ care workload. For foreigners who did not master the language in which their children were educated, it was simply impossible. In Iceland, Móðurmá: The Association on Bilingualism, an organisation usually dedicated to teaching children their mother-tongue, adapted its activities to mitigate this problem. Following an agreement with the government, the plurilingual association helped students by offering remote teaching in their mother tongue and with individual homework support during the period of school closures. These activities also aimed at breaking students’ and parents’ isolation.

In Slovakia, the NGO ‘Childhood to Children’ worked with Roma adolescent mothers to raise awareness about available online education and about the importance of registering children in a school. They also provided educational activities for young children, involving women from Roma communities, local municipalities, and schools.

Recommendations to expand care facilities

Care facilities should be free, accessible for all, and at a close distance from home. This would reduce the travel burden which mainly falls on women. People working in non-standard or difficult conditions, such as night workers, should have access to extended child-care support, adapted to their needs. Child-care facilities for children under three years old are still too sparse in a number of countries and should be expanded. It is still often assumed that mothers should look after their child in its first years of age and that child care therefore is not necessary. Policies should also support families from vulnerable groups in their care activities by providing the necessary resources, such as language, time, schooling, or food.

Care leave policies

Better care work has the possibility to solve unforeseen problems without creating further inequalities. In Germany, a federal policy provided caregivers (as in unpaid carers) with greater flexibility in care leave, recognising the critical role caregiving relatives play in supporting an overloaded health-care system during the pandemic. This policy includes a longer care leave period in acute cases (20 days), longer periods of financial support, shorter periods for announcing leave, and the possibility to announce the leave via mail. Greater flexibility will encourage caregivers to use the various leaves when necessary – including switching from a full-time to a part-time position and finding a better balance between their care work and their paid work. In Lithuania, an amendment to the Act on Social Insurance for Sickness and Maternity made it possible to exclude parents’ furlough period from calculations of maternity and child-care leave allowances. Although this measure had been put forward some years ago, it was only after a change of government in 2020, with more women representatives, that the measure was finally approved. When considering policies directed at women, the gender composition of decision bodies appears to be crucial.

In Turkey, during the various lockdown phases, schools were closed for long periods. In order to mitigate the effects of this situation, a national measure allowed mothers of children under ten and employed in the public sector to request administrative permission to take care leave. This decision, limited to the public sector and to women, fuelled much public criticism (Axelsson et al. Citation2021; Cibin et al. Citation2021). Responding in part to this criticism and to support front-line workers, another measure was taken to keep kindergartens open during the following lockdown for parents devoid of employers’ support.

Recommendation on care leave policy

Care leave policies could play an important role in making domestic care work gender equal. Rather than developing these in isolation from other policy domains, these policies should be shaped by and shape more flexible work arrangements, thereby accommodating the different needs of different workers across sectors. While various care leaves may have detrimental effects by increasing the gender care gap(s) and create incentives for non-primary caregivers to let their partners take up the care burden, these may be prevented by intersectoral policymaking, that is, policymaking that draws on different sectors and their interconnectedness rather than working in thematic or sectoral silos. For these reasons, flexible work arrangement schedules should be reshaped while taking into account the heterogeneous needs and duties of workers alongside the proposition of care leave policies. This is in line with ILO's call for urgent policy measures to invest in the care economy to foster COVID-19 recovery:

investing in care leave policies (e.g. maternity, paternity and parental leave) and flexible working arrangements which, when well designed, can help working parents to combine paid work and family responsibilities, while encouraging a more even division of work at home’ (ILO Citation2021: 9)

Paternity leave should be as long as maternity leave, and remunerated, compulsory, and untransferable. This would not only give options to fathers on paper, but also in practice, whereas now fathers often cannot take up their full paternity leave. This policy would directly challenge cultural assumptions and customs that hold women as primarily responsible for children.

All categories of workers must have access to care leave and if the type of activity does not allow the use of this support, other forms of care must be available.

Men's contribution to child care

Better care work is work that is equally shared by those involved. The narrative interviews and workshops with inequality experts conducted within RESISTIRÉ point towards a change in the role of men in care work, and in the perception of masculinities – towards a more caring role and discourse, sometimes enabled by the employer (Axelsson et al. Citation2021). The role of men as caring fathers was further discussed by the inequality experts in the workshops, and it was stressed how the pandemic has produced new and more extensive practices of family and community participation among young fathers and practices of caring masculinities. For example, one expert mentioned that preliminary data from Turkey show that men also contributed to increased household work, while another expert mentioned that UK fathers were able to be more involved in child care and household work if they worked from home. Although in absolute terms, the analysis of the Rapid Assessment Surveys showed that women's contribution to child care increased more than men's, thus widening the gendered care gap (Stovell et al. Citation2021), men increased their contributions to child care at roughly the same rate as women, and on a macro level, we found from the policy mapping that out of the 298 policies in Europe related to COVID-19 that we screened, very few of them explicitly focused on paternity leave (Cibin et al. Citation2021). However, the micro level and the individual narratives collected by RESISTIRÉ underline a better story of shared care responsibility between partners and other forms of support from partners or ex-partners. Doris, living in Austria, who found school closing and teleworking almost unbearable, expresses the value of living in a gender equal relationship:

My husband and I took turns, one of us was responsible for home-schooling and looking after the children, while the other person was working. (Doris, 48 years old, Austria, 31 July 2021)

My husband has taken the liberty to work from home to take care of the children. … His employer played a huge role. This would not have been possible if his employer had not offered this flexibility. (Maria, 45 years old, Bulgaria, 31 July 2021)

My husband was also a great help … He switched to home office when the pandemic started, so we both took care of the children. We alternately organised child care and work and it worked pretty well. (Lena, 39 years old, Germany, 31 July 2021)

When it comes to bridging the gendered care gap, better stories of societal initiatives show the importance of making men's care more visible. In Ireland, Childhood Development, a registered Charity, hosted a webinar on ‘Engaging Dads, Supporting Families’ to encourage a greater gender share of caring responsibilities. It highlights the extent to which policy responses to the pandemic have helped accelerate a change in fathers’ roles as carers. In the UK, the ‘Dope Black Dads’ podcast platform provides a safe space for mutual learning and exchange among black fathers. Experiences are shared on the intersection of fatherhood and race, including on the risk of discrimination for fathers and their children or families, as well as the added pressures of being a black male parent. The hopes are that this podcast will be a step in the right direction and might help black fathers from feeling alone, to celebrate, heal, and inspire positive practices.

Recommendations to make men's care more visible

Both policymakers and employers should participate in promoting gender equal role models for young men, leading to equal and open caring role models. Promotional campaigns could showcase examples of changes in men's values, actions, and decisions, such as by highlighting politician men involved in gender equality, or by illustrating the impact reversed stereotypical depictions of caring roles can have on gendered assumptions. ILO (Citation2020: 19) suggests the use of ‘targeted employee engagement and creative initiatives, such as role-modelling of good practices by male managers, social-media campaigns, internal blogs or photos, videos … ’.

Conclusions and suggestions for future research

The policy mapping conducted within RESISTIRÉ showed that most policies introduced to manage the pandemic did not take into account gendered and intersectional inequalities, including e.g. gender and gender identity, nationality, migration, and age. This lack was especially pronounced in the first phase of the pandemic, although not limited to it. The measures have often targeted specific sectors and segments of the population, leaving vulnerable groups of people, e.g. women in both the formal and informal, paid as well as unpaid, care sectors, in a difficult position and already disproportionately burdened by unequal care arrangements (e.g. night workers, minimum wage workers), while some social groups (ethnic minorities, same-sex couples, single parents) have also faced discrimination, stigmatisation, and racism when trying to make use of care facilities and policies. Although the pandemic has made the difficulties of care work more evident, little has been done to prevent the burden of this work falling mainly on women. While in some cases there has been greater sensitivity to the need to support more affected groups, such as single mothers and people living with disabilities, most of these measures have been gender insensitive and failed to address intersecting inequalities. The need for state intervention via gendered and intersectional legislation and policy on issues such as the movement of people, the closure of schools and services for online/offline education, and the management of health-care services, emerged as important as these have substantial implications for the enactment and protection of human and fundamental rights.

Our analysis shows that during the first phase of the pandemic, policymakers prioritised the protection of public health while maintaining economic production. However, policies were often underpinned by an implicit representation of society as cisgender with ‘traditional’ two-parent families with citizenship, standard employment contracts, and one or two children. In these traditional representations, women simultaneously performed the unpaid, domestic care work, paid informal care work, and paid formal care work, including essential jobs as health-care workers and domestic workers. Hence, policymaking during the pandemic has not paid sufficient attention to gendered and intersectional inequalities. However, as the results section makes visible, there were exceptions. These exceptions are valuable as they point towards better stories of policymaking, and function as a source of inspiration for future policymaking.

Better stories are also found in civil society, where inequalities induced by policy responses to the pandemic were often counteracted by civil society initiatives. While some groups focused on shedding light on equalities by collecting and analysing data, others raised awareness and protested for vulnerable groups’ rights. Initiatives ranged from offering concrete support, such as distributing essential goods or providing shelter, to creating mutual aid platforms to match demand and supply of goods and services. Civil society stepped in where the policy level failed, by distributing information to people not reached by official information channels, and by providing health support and psychological assistance.

Hence, we have been witnessing examples of better stories, which may provide a useful analytical and methodological tool to make visible potential ways forward and offer recommendations to policymakers. The positiveness of the concept helps to keep the focus on solutions and on the ambition to change for better in a context where the reality and the facts are often depressing. In contrast to tendencies to degender policy or reduce gender to the family domain, the better stories lens points to the need to make gender visible and to locate gender in all domains – not just the family. Although, these stories do not operate in isolation and in fact are located in deeply gender unequal contexts, they carve spaces and opportunities for hope and pave the way for more gender equitable outcomes through participatory and accountable policymaking.

While it is clear that some care workers have been disproportionately burdened by unequal care arrangements, this paper has searched for and made visible multiple examples of better stories of policies and societal responses to the pandemic across Europe. In our analysis, an increased focus on intersectionality in approaching care policies, with a specific focus on vulnerable groups in relation to care, could constitute an even better story.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the RESISTIRÉ consortium for their contributions to the research on which this paper builds, including both partners and the national researchers in each of the 31 countries. We would also like to thank the reviewers of the draft versions of the paper and the journal editors for their insightful comments and substantive help to improve the paper.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sofia Strid

Sofia Strid is Associate Professor in Gender Studies at Örebro University, Sweden and Senior Lecturer in Sociology at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden. Postal address. Skanstorget 18, 411 23 Gothenburg, Sweden. Email: [email protected]

Colette Schrodi

Colette Schrodi is a Communications Officer at the European Science Foundation, France. Email: [email protected]

Roberto Cibin

Roberto Cibin is an Associated Scientist and Postdoctoral Researcher at the Institute of Sociology of the Czech Academy of Sciences, Czech Republic. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 See the RESISTIRÉ webpage for more information: https://resistire-project.eu.

2 The national researchers who collected the data in the first cycle of research are named in the published reports, see Axelsson et al. (Citation2021), Cibin et al. (Citation2021), and Stovell et al. (Citation2021).

References

- Altınay, A. G. (2019) ‘Undoing academic cultures of militarism: Turkey and beyond’, Current Anthropology 60, No. Supple, S15-S25 (SSCI).

- Axelsson, T., A.-C. Callerstig, L. Sandström and S. Strid (2021) ‘Qualitative indications of inequalities produced by COVID-19 and its policy responses’. 1st cycle summary report. Zenodo. doi:10.5281/zenodo.5595815.

- Boyer, B., J. Cook, and M. Steinberg (2006) In Studio: Recipes for Systematic Change, Helsinki: SITRA.

- Boyer, B. (2011) ‘Helsinki Design Lab ten years later’. She Ji: The Journal of Design, Economics and Innovation 6(3): 279–300.

- Bustelo, M. (2017) ‘Evaluation from a gender+ perspective as a key element for (re)gendering the policymaking process’, Journal of Women, Politics & Policy 38(1): 84–101. doi:10.1080/1554477X.2016.1198211.

- Cibin, R., T. Stöckelová and M. Linková (2021) ‘RESISTIRE D2.1 - Summary Report mapping cycle 1′. doi:10.5281/zenodo.5361042.

- Dugarova, E. (2020) ‘Progress Towards Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment: The UNDP Journey’, UN Chronicle. New York.

- Gaver, W. (2012) ‘What should we expect from research through design’, In Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems (937–946). doi:10.1145/2207676.2208538.

- Georgis, D. (2013) Better Story. Queer Affects from the Middle East, New York: State University.

- Hankivsky, O. and A. Kapilashrami (2020) ‘Beyond sex and gender analysis: an intersectional view of the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak and response [Policy brief]’, Queen Mary University of London & The University of Melbourne.

- Hankivsky, O., D. Grace, G. Hunting, M. Giesbrecht, A. Fridkin, S. Rudrum, O. Ferlatte and N. Clark (2014) ‘An intersectionality-based policy analysis framework: critical reflections on a methodology for advancing equity’, International Journal for Equity in Health 13(1): 119. doi:10.1186/s12939-014-0119-x.

- Hussmanns, R. (2004) ‘Statistical definition of informal employment: Guidelines endorsed by the Seventeenth International Conference of Labour Statisticians (2003)’, In, 7t. h Meeting of the Expert Group on Informal Sector Statistics (Delhi Group) (2-4).

- ILO (2018) Care work and care jobs for the future of decent work. International Labour Office: Geneva. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—dgreports/—dcomm/—publ/documents/publication/wcms_633135.pdf (last checked 24 April 2022).

- ILO (2020) Teleworking during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. A practical guide. International Labour Office: Geneva. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---protrav/---travail/documents/instructionalmaterial/wcms_751232.pdf (last checked June 2022).

- ILO (2021) Building Forward Fairer: women’s rights to work and at work at the core of the COVID-19 recovery. Policy brief. Geneva. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—dgreports/—gender/documents/publication/wcms_814499.pdf (last checked 24 April 2022).

- Lokot, M. and Y. Avakyan (2020) ‘Intersectionality as a lens to the COVID-19 pandemic: implications for sexual and reproductive health in development and humanitarian contexts’, Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters 28(1), doi:10.1080/26410397.2020.1764748.

- Lombardo, E., P. Meier and M. Verloo (2017) ‘Policymaking from a gender+ equality perspective’, Journal of Women, Politics & Policy 38(1): 1–19. doi:10.1080/1554477X.2016.1198206.

- Risman, B. J. (2004) ‘Gender as a social structure’, Gender & Society 18(4): 429–450.

- Stappers, P. J. and E. Giaccardi (2017) ‘Research through design’. In The Encyclopedia of Human-computer Interaction (pp. 1-94). The Interaction Design Foundation. https://www.interaction-design.org/literature/book/the-encyclopedia-of-human-computer-interaction-2nd-ed/research-through-design (last checked 17 February 2022).

- Stovell, Clare, F. Rossetti, L. Lionello, A. Still, R. Charafeddine, A. L. Humbert and C.Tzanakou (2021) ‘RESISTIRÉ D3.1: Summary report on mapping of quantitative indicators - cycle 1. doi:10.5281/zenodo.5541035.

- UN (2020) ‘Policy brief: the impact of COVID-19 on women’. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/policy-brief-the-impact-of-covid-19-on-women-en.pdf (last checked 24 April 2022).

- Verloo, M. (2006) ‘Multiple inequalities, intersectionality and the European Union’, European Journal of Women’s Studies 13(3): 211–228.

- Verloo, M., ed. (2007) Multiple Meanings of Gender Equality: A Critical Frame Analysis of Gender Policies in Europe, Budapest, Hungary: CPS Books.

- Verloo, M. (2013) ‘Intersectional and cross-movement politics and policies’, Signs 38(4): 893–915. doi:10.1086/669572.

- Walby, S. (2015) Crises, Bristol: Polity Press.

- Walby, S., J. Armstrong and S. Strid (2012) ‘Intersectionality. Multiple tensions in social theory’, Sociology 46(2): 224–240.

- Walter, L. A. and A. J. McGregor (2020) ‘Sex- and gender-specific observations and implications for COVID-19’, The Western Journal of Emergency Medicine 21(3): 507–509. doi:10.5811/westjem.2020.4.47536.

- Wenham, C., J. Smith and R. Morgan (2020) ‘COVID-19: the gendered impacts of the outbreak’, The Lancet, 395(10227): 846–848.

- Živković, I., A. Kerremans, A. Denis, R. Cibin, M. Linková, C. Aglietti, M. Cacace, S. Strid, A.-C. Callerstig, T. Axelsson, C. Schrodi, C. Braun and G. Grace Romeo (2021) ‘RESISTIRE D6.1 Report on solutions cycle 1′, Zenodo. doi:10.5281/zenodo.5789230.

- Živković, I., A. Kerremans and A. Denis (eds.) with Sofia Strid, Anne-Charlott Callerstig, Tobias Axelsson, Ayşe Gül Altınay, Nazlı Türker, Elena Ghidoni, Laia Tarragona Fenosa, Roberto Cibin, Clare Stovell and Charoula Tzanakou. (2022) ‘RESISTIRÉ - Agenda for Future Research. 1st Cycle’, Zenodo. doi:10.5281/zenodo.5827993.