ABSTRACT

Paid work and gender equality are key elements of international development discourse on women’s economic empowerment. New digital technologies are considered to generate paid work opportunities for the marginalised groups in Africa, particularly women. The rise of the platform economy (work digitally mediated via platforms), for example, is framed as a panacea to poverty and informality among women. Yet the evidence remains anecdotal so far. Drawing on the author’s empirical research conducted between 2015 and 2021 on two kinds of digital labour (remote and place-based work) in Africa, the paper examines the job-quality outcomes among women gig workers in five African countries. The paper highlights new gender-based inequalities on platforms and the ways in which women cope with such outcomes. In particular, it outlines economic insecurities, discrimination at work, high work intensity and adverse physical and psychological impacts among women workers on platforms. It advances the cause for women’s labour rights and offers policy recommendations for a gender-equitable platform economy.

Le travail rémunéré et l’égalité des genres sont des éléments clés du discours du développement international sur l’autonomisation économique des femmes. Les nouvelles technologies numériques sont considérées générer des opportunités de travail rémunéré pour les groupes marginalisés en Afrique, en particulier les femmes. La montée de l’économie des plateformes (travail diffusé par des technologies numériques à travers des plateformes), par exemple, est présentée comme une panacée pour lutter contre la pauvreté et l’informalité parmi les femmes. Or, les données factuelles restent, à ce jour, anecdotiques. En s’inspirant des recherches empiriques menées par l’auteur entre 2015 et 2021 sur deux types de travail numérique (télétravail et travail sur site) en Afrique, ce document examine les résultats en matière de qualité de l’emploi parmi les travailleuses de l’économie à la demande dans cinq pays africains. Il met en relief les nouvelles inégalités de genre sur les plateformes et les manières dont les femmes font face à ces résultats. Il présente en particulier les insécurités économiques, la discrimination au travail, le rythme de travail soutenu, et les impact physiques et psychologiques négatifs parmi les travailleuses des plateformes. Il promeut la cause des droits du travail pour les femmes et propose des recommandations de politiques générales pour une économie des plateformes équitable.

El trabajo remunerado y la igualdad de género son elementos fundamentales presentes en el discurso internacional de desarrollo sobre la capacitación económica de las mujeres. Se considera que las nuevas tecnologías digitales pueden generar oportunidades de trabajo remunerado para los grupos marginados de África, sobre todo para las mujeres. La economía de plataforma (trabajo mediado digitalmente a través de plataformas), por ejemplo, se presenta como una panacea para paliar la pobreza y la informalidad prevaleciente entre las mujeres. Sin embargo, hasta ahora, las pruebas sobre su funcionamiento adecuado siguen siendo anecdóticas. Tomando como punto de partida la investigación empírica realizada por el autor entre 2015 y 2021 sobre dos tipos de trabajo digital en África (el trabajo a distancia y el trabajo basado en el lugar), el artículo examina los resultados en términos de la calidad del empleo informal de las trabajadoras de cinco países africanos. Al respecto, destaca las nuevas desigualdades de género encontradas en las plataformas y las formas en que las mujeres hacen frente a esta situación. En particular, esboza las inseguridades económicas, la discriminación en el trabajo, la alta intensidad del trabajo y los efectos físicos y psicológicos adversos que provoca en las mujeres que trabajan en las plataformas. Asimismo, promueve la reivindicación de derechos laborales de las mismas y ofrece recomendaciones políticas para lograr una economía de plataformas equitativa desde el punto de vista del género.

Introduction

Paid work and gender equality are key elements within the international development discourse.Footnote1 New digital technologies are considered to generate paid work for marginalised groups, particularly for women. The rise of the platform economy (work digitally mediated via platforms) (Anwar and Graham Citation2022; Woodcock and Graham Citation2019) is seen to increase women’s participation in the labour markets and framed as a panacea to poverty and inequality among women. Yet, little is known about the gender dynamics on platforms, particularly in the context of the global South, which is the main concern of this paper.

Women in general are more likely to face unpaid and underpaid work, along with gender stereotypes (e.g. certain tasks are considered to be not suitable for women) which generate inequalities between men and women (ILO Citation2018). In addition, the twin burden of productive and reproductive labour means that women remain structurally vulnerable in the labour market (Chen et al. Citation2005; McDowell Citation2001). In light of this, there are notable assumptions about the platform economy as a fix for eliminating some of these gender-based inequalities (e.g. lower wages, long working hours, health risks, inadequate social protection) (e.g. Kuek et al. Citation2015; Madgavkar et al. Citation2019; World Bank Citation2016).

Much has been written already about the digital labour platforms (henceforth platforms) and their development implications on workers (e.g. Anwar and Graham Citation2022; Graham et al. Citation2017; ILO Citation2021; Schor Citation2020, among many others). Emerging studies have recently begun to research the gender dimensions of platform work primarily in the global North contexts (e.g. Churchill and Craig Citation2019; Galperin Citation2021; Gerber Citation2022; James Citation2022). However, scholarly research on women’s experience of the platform economy in the global South, particularly in Africa, is still in its infancy (notable exceptions include Anwar et al. Citation2022a; Hunt et al. Citation2019). This paper addresses this gap.

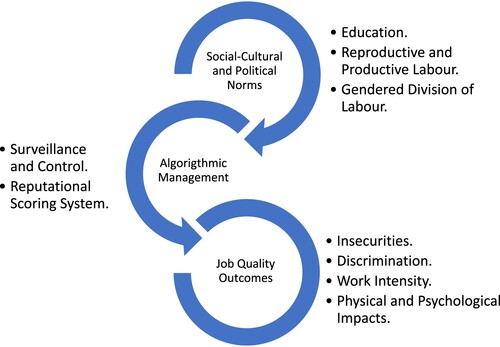

Conceptually, the paper argues that platforms generate inequalities both due to the technologically mediated labour process and the gendered nature of sociopolitical and cultural relations. Algorithmic management of the labour process adversely affects women workers more than men (see Gerber Citation2022). Workers also remain embedded in specific geographical landscapes governed by sociopolitical and cultural norms. These norms remain gendered and are refracted through platforms to produce gender inequalities. For example, women around the world still perform most of the child care which affect the way they interact on platforms. As a result, they continue to face adverse outcomes on platforms in comparison to men.

Empirically, the paper examines the job-quality outcomes (both economic and non-economic) on platforms to pinpoint the processes through which inequalities are generated by platforms which affect women and men differently. These outcomes are: insecurities, discrimination at work, intensification of labour, and physical and psychological impacts. The paper argues that platform work further pushes women into precariousness and contributes towards their already-existing vulnerabilities, especially in the context of Africa, where the majority of the workforce is already classified as working poor (ILO Citation2020). Overall, this paper contributes to the growing platform economy literature (e.g. Anwar and Graham Citation2022; Prassl Citation2018; Ravenelle Citation2019; Schor Citation2020) by not only bringing the voices of African women workers but also by focusing on two key forms of digital labour (remote work and place-based work) via platforms and their job quality implications on women in Africa. It concludes by advancing the cause for women’s labour rights and offers policy recommendations for a gender-equitable platform economy.

Gender and work quality on platforms

Rapid expansion of platforms in recent times has led some to call this trend the ‘platformisation of the labour and society’ (Casilli and Posada Citation2019). The paper uses the term ‘platform economy’ and ‘gig economy’ interchangeably. Broadly speaking, work done on labour platforms can be divided into two categories: remote work and geographically tethered work (Anwar and Graham Citation2022; Graham and Anwar Citation2018a, Citation2018b). Whereas remote work can be done by workers on a planetary scale (e.g. image tagging, transcription), geographically tethered or place-based work has to be done in specific locations (e.g. ride-hailing taxis) (ibid.).Footnote2 This paper deals with both remote and place-based work and how these are implicated in generating gender-based inequalities.

Workers’ experience of the platform economy has been extensively documented. For example, in high-income countries, studies have examined working conditions in both remote work and place-based work, e.g. United Kingdom (Cant Citation2019; Woodcock Citation2020), the USA (Schor Citation2020), and Australia (Churchill and Craig Citation2019). Similarly, in low- and middle-income countries, the platforms’ contribution towards job-quality outcomes has also been examined, e.g. Brazil (Amorim and Moda Citation2020) and India (Samuel Citation2020), and in Africa (e.g. Anwar and Graham Citation2022; Carmody and Fortuin Citation2019).

The overall message emerging from this literature is that the platform economy is built around the fragmentation of work and commodification of labour facilitated by platforms (Howcroft and Bergvall-Kåreborn Citation2019). Employment relations on platforms are defined by short-term, temporary contracts, lack of social protection, and a lack of recognition of workers’ employee status (Prassl Citation2018). As a result, workers often lack bargaining power on platforms (Anwar and Graham Citation2022). The algorithmic control of the labour process further makes these jobs volatile (Woodcock Citation2020). It is, therefore, somewhat ironic that the platform economy is seen by many to expand non-standard employment relations in the high-income countries (see Berg Citation2016; Huws et al. Citation2017), yet for low- and middle-income countries, including African countries, it is touted to have great economic development potential with poverty- and inequality-reduction impacts and formalisation in the labour markets (e.g. Kuek et al. Citation2015; World Bank Citation2016).

In the context of existing disparities in the local labour markets, in terms of gender, race, and class in Africa, there is an urgent need to engage with the platform economy-development debate. First, the overall labour force participation of women on the continent has grown over the years and the rate (53 per cent) is above the world average.Footnote3 Yet, women on the continent are more likely be in the informal sectors of the economy often characterised by unpaid and underpaid work (e.g. agriculture and care work) (ILO Citation2018). For example, in South Africa, despite an increase in the labour force participation among women since the end of Apartheid in 1994, they are overly represented in the informal sectors (Rogan and Alfers Citation2019). They face gender stereotypes (i.e. what work they can and cannot do) and the reproductive labour is performed exclusively by women which further affects women’s ability to sustain a livelihood (Chen et al. Citation2005; ILO Citation2018). Furthermore, adequate maternal and child-care support is rarely available to African women (Moussié and Alfers Citation2018) and, as a result, they are more likely to exit the labour markets to manage child care. This no way suggests that African women do not have agency or that they have limited roles in everyday socioeconomic realities on the continent. Kinyanjui’s (Citation2014, 2–3) study on women in urban Kenya demonstrates women’s ability to navigate exclusion and informality through ‘mobility, solidarity, entrepreneurialism, and collective organisation’. Similarly, in Ghana, despite being faced with disadvantages in terms of livelihoods, gendered impacts of economic liberalisation, and citizenship rights, women’s organising has been relatively active in the last couple of decades promoting and defending women’s rights (Tsikata Citation2008, Citation2009). The point is that African women’s lower socioeconomic position is a result of the numerous structural constraints they face. From a development perspective, to eliminate gender inequalities, paid work is seen as a potential solution.

There are already notable assumptions made about the platform economy as a technological fix for eliminating some of the structural constraints found in the labour market, particularly in Africa (e.g. Kuek et al. Citation2015; Madgavkar et al. Citation2019; World Bank Citation2016). Essentially, it is assumed that platforms can eliminate constraints faced by women and provide them with good-quality jobs. This paper’s analytical framework is built around the understanding that job-quality outcomes (both economic and non-economic) (see Green Citation2006; Kalleberg Citation2013) on platforms are influenced at the intersection of the digitally mediated nature of gig work and the sociopolitical and cultural norms that continue to dictate labour markets. A heuristic framework for understanding the relationship between platform work and job-quality outcomes is presented in .

There are four key attributes of job-quality outcomes worth considering here.Footnote4 One is the various forms of insecurities attached to work (Standing Citation2014). Platforms favour clients by enabling them to fire workers at any time. Some platforms openly brag that clients have to only pay workers if they are satisfied with work (see Anwar and Graham Citation2020). Even though the on-demand nature of gig work brings employment insecurities to both men and women, it is women who remain disadvantaged. For example, despite a platform’s ability to connect employers directly to workers, women are less likely to participate and find paid work on platforms than men, according to the ILO (Citation2021). Globally, only one in every three remote workers is a woman (ibid.). We show in this paper how the gendered division of labour intersects with the algorithmic management of the labour process on platforms to generate economic insecurities which are greater for women than men.

Secondly, discrimination at workplaces is another marker for the quality of work. While entry barriers to the platform economy may have become lower for some workers, many are likely to be discriminated (e.g. platforms can remove or deactivate accounts at will). For women, this is particularly evident. The burden of reproductive labour (e.g. child care, domestic labour, emotional labour), much of which remains unpaid, falls exclusively on women (MacDowell Citation2001). Thus, women are already more likely to leave platforms. Additionally, wage discrimination is already well known in the traditional labour markets where women earn less than men for the same type of job (ILO Citation2018). There is already evidence that on platforms women earn less than men but work longer hours (see e.g. Barzilay and David Citation2016).

Thirdly, work intensity is considered a crucial indicator of job quality (see Green Citation2006). While high work intensity is common on platforms, women are faced with particularly acute outcomes (see Anwar and Graham Citation2021; Ravenelle Citation2019). In this paper, we note that though flexibility at work is a much-needed attribute for women on platforms, the risk of losing jobs and low pay means they end up doing long working hours on platforms (see Anwar and Graham Citation2020). This further marginalises women’s ability to sustain work for a long time and experience intensification of their labour (Anwar and Graham Citation2022).

Fourthly, insecurities at work result in lower psychological and physical well-being at work (Cheng et al. Citation2008; Jahoda Citation1982). While literature on the platform economy has already noted that depression, stress, exhaustion, and loneliness are common experiences among gig workers (see Anwar and Graham Citation2021), this paper discusses how these outcomes get particularly amplified for women. The remainder of the article examines job-quality outcomes among African gig workers to show how platforms generate inequalities. The central argument here is that the gig economy’s development contribution remains highly gendered which in the African context pushes women further into precarity. We now turn to methodology.

Methodology

The empirical material comes from two large research projects on the gig economy in Africa. One project focused on remote work and the other focused on place-based work. For remote work, workers were sourced primarily from Upwork (one of the world’s largest labour platforms in terms of registered workers), and for place-based work, respondents were sourced from Uber. Most African gig workers use these platforms to source work. Fieldwork was conducted across five countries in Africa: Ghana, Nigeria, Uganda, Kenya, and South Africa. These countries represent some of the major markets for the platform economy in Africa and hence have higher concentration of gig workers in comparison to others (e.g. Sierra Leone, Senegal, or Tanzania). Workers were primarily concentrated in urban areas, highlighting the urban bias commonly found on platforms. We recruited participants to include a diversity of experiences (e.g. gender, age, education, marital status). However, one of the challenges was the gender balance in our sample. For example, men are overly represented in both remote and place-based work (Anwar and Graham Citation2022; Anwar et al. Citation2022a; ILO Citation2021), which reflects in our sample of participants. A total of 65 remote workers and 76 ride-hailing workers were interviewed, the majority of whom were men. For remote work, women would often decline or cancel our interview requests. Sometimes, they would tell us that they had child-care duties or were working to a deadline on platforms which they cannot avoid. On ride-hailing, sourcing women drivers was even more difficult due to extremely low representation of women in general. No women drivers were interviewed in South Africa, but between Ghana and Kenya we were able to interview 18 women drivers. Some respondents were interviewed multiple times resulting in a total of 152 in-depth interviews. Interviews with remote workers were conducted face to face between 2016 and 2017 with some follow-up remote interviews in 2021. Ride-hailing workers were interviewed between April 2020 and July 2021.

Interviews lasted from a minimum of 25 minutes to a maximum of 189 minutes. All interviews were recorded, except six where detailed notes were taken. Interview transcripts were then uploaded on to NVivo for coding and analysis. Transcription of interviews was done by trusted local transcribers who had signed a non-disclosure agreement. Detailed information on fieldwork strategy and research design on remote work is given in Anwar and Graham (Citation2022) and on place-based work in Anwar et al. (Citation2022a, Citation2022b). gives a general overview of fieldwork.

Table 1. Fieldwork and participants.

In reporting the findings, we adopt a comparative framework to examine how job-quality outcomes are experienced by women and men across two main categories of gig work. This approach allows us to build a comprehensive picture of platforms’ contribution towards inequalities by focusing on insecurities, discrimination, work intensity, and psychological and physical impacts, and how these attributes are experienced differently by women. The results presented here are indicative and not representative.

Digital labour and job-quality outcomesFootnote5

Insecurities and discrimination

According to some estimates, 4.8 million African workers have earned an income via platforms (Insight2impact Citation2019). Both the remote work activities (e.g. transcription, data annotation, video editing, virtual assistant work, etc.) and the place-based work (including ride-hailing, domestic work, and delivery services) have grown in recent years on the continent. Existing survey data confirm that the African workforce’s primary motivation to join platforms is due to the lack of paid work locally and additional sources of income. For example, the ILO’s (Citation2021) survey found that in Kenya over 60 per cent of the ride-hailing drivers join platforms due to the lack of paid work locally and the opportunity to earn an extra income. The corresponding figures for Ghana were 45 per cent (ibid.).Footnote6 An earlier survey of three African countries further confirms that remote work is seen by more than 68 per cent of the workers to be an important source of income (Graham et al. Citation2017). During our research we also found that most African workers had joined platforms because they were struggling to find sustainable paid work locally. However, the gig economy’s contribution towards African workers’ long-term livelihoods remains questionable.

First, gig work remains economically insecure. For example, ride-hailing offers extremely low hourly rates (ILO Citation2021), which in some cases can be lower than the ongoing rates for the meter taxis (a point made by many or almost all of our respondents).Footnote7 In fact, ride-hailing platforms like Uber have always touted their importance in the urban transport space due to the cheap cost for consumers. However, this cheaper cost comes at a price, i.e. low pay for drivers. According to the drivers we interviewed, if drivers’ costs (e.g. fuel, insurance, data) are taken into account, drivers’ incomes were often lower than minimum wages (also see Anwar et al. Citation2022a, Citation2022b; Otieno et al. Citation2020). On remote work, workers face a global race to the bottom (Graham et al. Citation2017). In our sample, workers reported earning as little as US$3 per hour. It is to be noted that some workers were able to earn higher than the national minimum wage.Footnote8 Remote work is also footloose which means workers can lose contracts easily if they demand higher wages, a point told to us by most workers we interviewed. In several instances, remote workers told us that clients cancelled contracts without informing them. But most importantly, there are gender dynamics involved and the experiences of women gig workers were different from those of men workers.

Ride-hailing remains male dominated (ILO Citation2021).Footnote9 In Kenya, only 5 per cent of the workforce in ride-hailing constitutes women, which is higher than India, Ghana, and Morocco, but lower than Indonesia and Chile (ibid.). Though in recent times, a few women-only platforms have emerged such as An-Nisa Taxi and Dada Ride (in Kenya) and Local (South Africa). Yet, when we spoke to women drivers, they told us that they still prefer to use Uber as their main platform, further highlighting the network effect and market dominance enjoyed by Uber.

Most of our women drivers noted platforms as their principal source of income, in comparison to male drivers most of whom have either a side business or were in regular jobs. Most women drivers were single mothers with no regular stream of income. Though it is to be noted that a few women drivers also complemented their earnings with other forms of entrepreneurial activities such as catering, street vending, corner shops, and tour guides. In the Kenyan context, such activities are known as Juakali’ (a Kiswahili term which translates as ‘fierce sun’), often referring to the small enterprises, small-scale traders, craftspeople, artisans, and their activities which are carried along the side of the streets, out under the sun, and little to no workspace. The term has also become synonymous with the informal sector in Kenya (Kinyanjui Citation2014, cf. Anwar et al. Citation2022b). But women workers face numerous challenges to sustain their livelihoods on platforms.

A majority of ride-hailing drivers told us they prefer driving at night (particularly over the weekend) because there is high demand and higher rates, and less traffic means they complete more trips. But such opportunities are rarely available for women drivers. Women avoid driving at night due to safety and security. One of them told us that customers would also avoid women-driven cars at night because such cars are at a high risk of carjacking. Hence, they earn a lower income than men. They also faced other kinds of discrimination which affects their ability to earn a high income. The women drivers we interviewed reported that customers consider male drivers to be better at driving than women and would cancel their trips after request if they see a woman driver. One driver, Ciku, alleged that this happens mostly when the customer is a women (interview, Nairobi, February 2021). In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, where income-earning opportunities were particularly reduced for the vast majority of the workforce in Africa, it was gig workers, particularly women, who experienced worse outcomes (e.g. loss of income, food insecurity, threats of repossession of homes and cars) (see Anwar et al. Citation2022a, Citation2022b). Thus, while ride-hailing may offer economic opportunities for the continent’s workforce, the sector’s sustained income-generating potential is questionable particularly for women. Let us look at remote work.

Remote gig work is also structured along gender lines. According to the Online Labour Observatory (OLO), only 39 per cent of the workforce is made up of women workers globally (Stephany et al. Citation2021). At the country level there are significant variations. In the USA (Farrell et al. Citation2018), Australia (Churchill and Craig Citation2019), and in European countries, more men participate in the gig economy than women, with the exception of Italy (see Huws et al. Citation2017). While the OLO’s data suggest only 33 per cent of Kenyan women participate in the remote gig economy, an earlier survey from Research ICT Africa found there were more women than men from the country (Research ICT Africa Citation2017).

Low levels of participation of women in the remote gig economy is reflective of gender-based inequalities that exist in society along the lines of education and ICT access. Women are more likely to be out of school and though more women graduated from universities, there is a clear discipline bias. More women undertake humanities degree than science, technology, engineering, and mathematics, according to a report by the Times Higher Education (THE) and UNESCO International Institute of Higher Education in Latin America and the Caribbean (IESALC) (Citation2022). Remote work depends on information technology infrastructure and digital skills and hence some are more likely to be excluded and discriminated (in this case women).

Gender-based discrimination is a common occurrence in the traditional labour markets with women often hired on a lower pay than men for the same job and low-skill or entry-level positions are more likely to be filled with women than men (Neumark and McLennan Citation1995). Women are also likely to face entry-barriers to labour markets, e.g. if they take a career break due to childbirth (Crompton et al. Citation2003). Women also perform much of the care and domestic labour which influence when they join the labour market and what kinds of jobs they can take, thus limiting their employment choices (see ILO Citation2016). Women workers end up entering into more non-standard employment relations, including part-time and self-employment, both of which might offer greater degrees of flexibility to manage paid and unpaid work but the economic rewards are lower (ILO Citation2018). These discriminations are also found on platforms.

Research has shown that despite the touted potential of creating a level playing field, remote work is known for various gender-based prejudices (e.g. male-type and female-type jobs) among clients which negatively affects women’s access to paid work (Leung and Koppman Citation2018). In our sample, the prejudices related to what work women can and cannot do. For example, a woman worker in Nigeria who primarily does article writing and search engine optimisation told us that clients favour men for contracts such as web design, software development, user interface, and data management (remote interview, April 2021). In fact, in our sample, despite a few women with engineering and computer science backgrounds, they rarely did software development work where pay tends to be higher. In terms of wages, research done by Adams-Prassl and Berg (Citation2017) has found that women earn only 82 per cent of what men earned, despite working similar hours, and having similar levels of education and experience on platforms.

Nevertheless, platforms like Upwork can provide economic opportunities for women who cannot find work locally or those who have child-care duties. Platforms can also provide women with economic independence from patriarchal figures in the family, a point made to us by a number of women. Women respondents also told us the importance of remote work in their lives vis-à-vis income generation, development of new skills, and career prospects. One women transcriber from Uganda told us that her work on Upwork has allowed her to support her parents and younger siblings. She also told us that the income from remote work is higher than she is be able to get locally. However, this was an exception rather than the norm in our sample.

Since women earn less than men on platforms (Barzilay and David Citation2016; Galperin Citation2021), some of our respondents attempted to diversify their livelihood opportunities.Footnote10 A women respondent in South Africa, who did multiple irregular jobs before her current work at a media company in South Africa, was a single mother. She told us that she joined Upwork because her current job does not pay enough to support herself and her son.Footnote11 However, workers like her are also fully aware of the risks that the footloose nature of remote work means they could lose jobs easily. Hence, their economic situation remains precarious.

Women’s ability to earn livelihoods via platforms is also dependent on their household positions and socioeconomic status. Within a household, interactions between family members have been characterised as co-operative conflicts (Sen Citation1990). That is to say, family members co-operate as long as it benefits all, though each one of them has their own conflicting interests too. Thus, each member’s bargaining power can influence who gets what or how resources are allocated within the household. It is here that social norms and intrahousehold relations affect the power of both women and men differently. During our fieldwork, we found husbands and wives would often work together on platforms such as Upwork, sharing work and helping each other. Yet, in some instances, husbands’ priorities would take precedence. Consider the following example. A social media manager and transcriber in South Africa who was a migrant and moved to Johannesburg to join her husband told us that she would get help from her husband with transcription work if she got busy with her other contracts on Upwork. But after a while her husband stopped helping and told her, ‘I do not want to do your work anymore’ (interview, Johannesburg, August 2016). Her husband focuses most of his time on running his own small company instead. It is clear that social norms and relations that exist in society limit women’s ability to work, access to education, assets, and further undermine their functioning and mobility (Agarwal Citation2008). Some of these translate into platform work to produce gendered outcomes in terms of adverse working experience.

Work intensity and physical and psychological impacts

One of the oft-cited benefits of the platform economy has been the flexibility at work (see Kuek et al. Citation2015; World Bank Citation2016). Because work gets algorithmically mediated via platforms, in theory, workers are able to get some flexibility in terms of when and where they can work (Graham and Anwar Citation2019). Workers (both men and women) in our sample highlighted that they were attracted to the platform economy for the flexibility it offered. However, this flexibility remains a myth for a vast majority of gig workers, particularly women, and workers face high-intensity work and long working hours on platforms.

On remote work platforms such as Upwork, the short-term nature of the contracts meant that for workers to be able to sustain an income, respondents have to constantly look for jobs and put bids on the platform. This resulted in workers often spending long hours searching for jobs or working long hours on multiple contracts. Some of the workers in our sample told us they work over 80 hours a week. Workers would also do unsocial hours such as late at night since most of their clients are based in the USA (see Anwar and Graham Citation2022). Additionally, work on platforms can be time-bound. For example, workers have to complete tasks on time in order to earn wages or else risk removal from the platforms. Some tasks, such as data annotation and transcription, come with timelines which are set by clients. If a worker failed to meet the deadline, that task could be unpaid (ibid.). But if workers are women, they faced a higher degree of intensification of their labour.

For women worker respondents, especially those who had children, flexible working arrangements were their preferred choice. They preferred jobs that gave them the ability to negotiate working hours (e.g. article writing, proof-reading, data annotation). The paradox here is that though these tasks often come with negotiable working hours, they pay less in comparison to jobs such as web design, software development, data management, etc. One worker in Accra told us that she has three children, and she works from 8 am until 2 pm on editing and social media management, which, according to her, are easy tasks to do and have negotiable working hours, even if that means less pay. As a result, women workers would do longer working hours than men to earn more or work late at night when their children are asleep. This point is further confirmed by a global survey which found that women respondents would often worked at night or during the evening in order to manage child care (Berg et al. Citation2018).

Numerous studies have now documented that the high-intensity work and long working hours coupled with income insecurities contribute to the adverse physical and psychological impact on gig workers (see Anwar and Graham Citation2022; Graham et al. Citation2017; Ravenelle Citation2019). These outcomes are particularly acute for women (see Gerber Citation2022).

Social interactions between fellow workers, family, and friends have long been considered effective for the psychological and physiological health of workers (Jahoda Citation1982). Remote workers were often confined to their homes or cafes, which were the main places of work. Also, the high work intensity coupled with irregular hours means workers’ interpersonal contacts, socialising, and communications are reduced. A group of workers we interviewed in Nigeria told us that they work mainly from their bedrooms and would rarely go out to meet their friends during the week because they were working over 70 hours a week when we interviewed them in 2017. A women Kenyan web researcher and virtual assistant on Upwork told us that she works between 45 and 60 hours a week and hardly gets free time for leisure and social activities.Footnote12 Most remote workers told us that they often feel lonely.

Another drawback is the mental stress among workers who are often worried about their next jobs. For example, a women transcriber in Kenya who sourced work from Upwork and some other platforms was doing variable working hours. As a result, her income would vary. When we asked her how this affects her, she replied ‘not knowing how much money you are going to earn next week makes you worry a lot. Sometimes I feel depressed but what else can I do’. Almost all women workers we interviewed told us that in order to compensate for low and variable pay, they had to either take up more jobs and work longer hours. Thus, a women transcriber may experience a greater degree of economic freedom from her husband or father, but this work may also intensify her labour since she has to perform both productive and reproductive labour (McDowell Citation2001).

Our respondents (both men and women) regularly told us that they feel ‘tired’, ‘exhausted’, and ‘stressful’. This is further illustrated by a women worker in South Africa, who has done a wide variety of digital work activities both on platforms and locally at a call centre. She told us that her past jobs include transcription, customer services, and data annotation. According to her, ‘it is extremely challenging to work full-time and raise children at the same time’. She would often work late into the night which means exhaustion during the day is common. Though she gets help from her husband with child care, this arrangement may not be available for some workers, such as for migrant and less-educated women.

We met a migrant women remote worker who came to South Africa from Cameroon with her husband and two children. Because she was unable to source work in Johannesburg, she decided to source paid work on platforms. She had only completed her O-levels and was doing menial tasks such document conversion and data annotation tasks. When we asked her to describe her experience of working on platforms, she told us that she struggles to balance her paid work, child care, and housework. She also told us that because she earns as little as US$1–2 per hour, it is hard to stay motivated and maintain the focus required to deliver quality work consistently.

Ride-hailing drivers were in a better position when it comes to socialising since their work requires them to be outside. Drivers would often meet at public spaces such as junctions, parking lots, outside restaurants, shopping malls, etc. But for them the workplace monitoring and strict control over labour processes by platforms such as Uber can also be tough and isolating (see Ravenelle Citation2019).

On Uber, one of the main platforms for ride-hailing work, drivers can choose to accept rides at any time or decline and log out of the platform. But Uber’s algorithm is designed in such a way that it penalises drivers if they decline too many requests or stay offline for days. Drivers we spoke to in all of our case study countries told us that their account has been blocked by Uber numerous times. Uber also removes workers from the profile if their ratings drop (see Anwar et al. Citation2022b). For women drivers, this is particularly challenging. Several women drivers in Kenya and Ghana told us that they would decline customer requests from certain localities of Nairobi and Accra. As a result, they have their accounts suspended from the platform.

Conclusions

The platform economy has been celebrated by many to create a level playing field and encourage inclusion in the labour markets for women. However, instead of bringing equality in the labour markets, this paper highlights how platforms are entrenching with the already-existing gendered inequalities in the labour markets, particularly in the global South. Using empirical evidence from Africa, the poorest region in the world, the paper pinpointed various insecurities, discrimination, high work intensity, and adverse physical and psychological impacts among women platforms workers. Put differently, the gig economy’s contribution towards development remains unconvincing, particularly for women. Research done in other country contexts (e.g. in high-income regions) further confirms that women face higher precarity than men due to the unequal division of unpaid care and domestic work (see Gerber Citation2022). Gerber’s (ibid.) comparative research between Germany and the USA also found that in institutional contexts where welfare policies better protect labour, gig workers face lower risks (e.g. in Germany in comparison to the USA). Our research here is a testament to this point that in African contexts where women workers rarely have adequate welfare support available to them, their conditions remain highly precarious.

For policy makers on the African continent, platform economy alone should not be taken as a silver bullet to address gender-based inequalities in society. One of their tasks should be to develop concrete plans to improve the provision of education and digital skills among the marginalised sections of the population such as women. This could help ease their entry barriers to the digital economy activities. However, removal of such entry barriers should be complemented with strong regulatory mechanisms designed to protect labour rights on the continent. For too long, platforms have avoided their responsibilities to protect labour and offer decent working conditions to workers through minimum wages, holiday pay, sick pay, pension, health care, etc. Over the years, they have also become emboldened to effectively ignore and/or circumvent existing regulations (see De Stefano and Aloisi Citation2019). It is time that governments do everything to ensure that platforms do not violate local labour regulations and are held accountable. For the African context, it is not just about the quantity of jobs but the quality of jobs that will go a long way to address the most pressing development issues such as inequality and poverty. Although some of these policy measures could potentially improve labour market outcomes for women, some of the most vulnerable women still struggle (e.g. migrants, single mothers, etc.). Also, the sociocultural norms that continue to shape labour markets and constrain women in varied ways need to be taken into contexts and analysed further for a comprehensive understanding of the ways in which new digital technologies can contribute towards women’s economic [dis]empowerment.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the anonymous referees and the editors whose comments and feedback improved the paper.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mohammad Amir Anwar

Mohammad Amir Anwar is a Lecturer in African Studies and International Development. He is a Senior Research Associate at the University of Johannesburg and a Research Associate at the Oxford Internet Institute, University of Oxford. He has been a Fellow of the Global Future Council at the World Economic Forum. His latest open access book, The Digital Continent, is published by Oxford University Press. Postal address: Centre of African Studies, University of Edinburgh. EH8 9LD. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 Gender is understood as a socially constructed rather than a biological category.

2 Some of the gig economy tasks have existed for centuries, except that they are now increasingly digitally mediated via platforms such as domestic work and taxi services.

3 Globally, the labour force participation for women is about 47 per cent, while for men it is 72 per cent (ILO Citation2022). While these figures suggest increasing feminisation of the labour market, it is also worth noting that statistics like these have various shortcomings and biases in terms of what is measured and not measured (e.g. women’s unpaid work) (see Green Citation2000). Another point is about different definitions being used by international organisations and national governments (e.g. unemployment measurement in South Africa) (see Alenda-Demoutiez and Mügge Citation2020).

4 Literature on job quality is huge and beyond the scope of this paper. Kalleberg (Citation2013) and Green (Citation2006) are noteworthy.

5 This section builds on some of the findings reported elsewhere (e.g. Anwar and Graham Citation2020, Citation2021, Citation2022; Anwar et al. Citation2022a, Citation2022b; Otieno et al. Citation2020).

6 Globally, the figure was over 40 per cent.

7 The ILO’s survey found ride-hailing drivers earn marginally higher hourly income than meter taxi drivers.

8 A trend reported in some other low-income countries (see Beerepoot and Lambregts Citation2015). Workers who succeed in earning high income often come from educated and rich socioeconomic backgrounds (see Anwar and Graham Citation2022). However, minimum wages remain a highly contentious issue as platforms rarely enforce national minimum wage regulations (see Wood et al. Citation2020).

9 Gender norms often dictate who does what work. Taxi services are considered to be men’s jobs, while care and domestic work is considered to be women’s jobs. Hence, domestic work platforms such as Sweep South have more women than men.

10 Informal workers often do multiple types of work to minimise economic uncertainties (see Callebert Citation2017).

11 The South African government pays child support grants in cash transfers, which are known to have a positive impact on poverty in the country (Davis et al. Citation2016).

12 This does not mean workers do not interact with each other or with their friends. Instead, their primary form of communication is digital (phone calls, video calls, text messages, Facebook, etc.) rather than face to face.

References

- Adams-Prassl, Abi and Janine Berg (2017) ‘When home affects pay: an analysis of the gender pay gap among crowdworkers’. Available at SSRN 3048711.

- Agarwal, Bina (2008) ‘Engaging with Sen on gender relations: cooperative-conflicts, false perceptions and relative capabilities’, in Basu, K. and Kanbur, R. (Ed.) Arguments for a Better World: Essays in Honor of Amartya Sen (Vol. II), Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, 157–177.

- Alenda-Demoutiez, Juliette and Daniel Mügge (2020) ‘The lure of ill-fitting unemployment statistics: how South Africa’s discouraged work seekers disappeared from the unemployment rate’, New Political Economy 25(4): 590–606.

- Amorim, Henrique and Felipe Moda (2020) ‘Work by app: algorithmic management and working conditions of uber drivers in Brazil’, Work Organisation, Labour & Globalisation 14(1): 101–118.

- Anwar, Mohammad Amir and Mark Graham (2020) ‘Hidden transcripts of the gig economy: labour agency and the new art of resistance among African gig workers’, Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 52(7): 1269–1291.

- Anwar, Mohammad Amir and Mark Graham (2021) ‘Between a rock and a hard place: freedom, flexibility, precarity and vulnerability in the gig economy in Africa’, Competition & Change 25(2): 237–258.

- Anwar, Mohammad Amir and Mark Graham (2022) The Digital Continent: Placing Africa in Planetary Networks of Work, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Anwar, Mohammad Amir, Jack Odeo and Elly Otieno (2022a) ‘There is no future in it’: pandemic and ride-hailing hustle in Africa’, International Labour Review, Online First. https://doi.org/10.1111/ilr.12364.

- Anwar, Mohammad Amir Elly Otieno and Malte Stein (Forthcoming 2022b) ‘Locked in, locked out: impact on the pandemic on ride-hailing in South Africa and Kenya’, Journal of Modern African Studies.

- Barzilay, Arianne and Anat Ben-David (2016) ‘Platform inequality: gender in the gig-economy’, Seton Hall Law Review, 47: 393–431.

- Beerepoot, Neils and Bart Lambregts (2015) ‘Competition in online job marketplaces: towards a global labour market for outsourcing services?’, Global Networks 15: 236–255.

- Berg, Janine (2016) ‘Income security in the on-demand economy: findings and policy lessons from a survey of crowdworkers’, Conditions of Work and Employment Series No. 74. ILO, Geneva.

- Berg, J., M. Furrer, E. Harmon et al. (2018) Digital Labour Platforms and the Future of Work: Towards Decent Work in the Online World. ILO, Geneva.

- Callebert, Ralph (2017) On Durban’s Docks: Zulu Workers, Rural Households, Global Labor, Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press.

- Cant, Calum (2019) Riding for Deliveroo: Resistance in the New Economy, London: Polity.

- Carmody, Padraig and Alicia Fortuin (2019) ‘“Ride-sharing”, virtual capital and impacts on labor in Cape Town, South Africa’, African Geographical Review 38(3): 196–208.

- Casilli, Antonio and Julian Posada (2019) ‘The platformization of labor and society’, in M. Graham and W. H. Dutton (eds.) Society and the Internet: How Networks of Information and Communication are Changing our Lives, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 293–306.

- Chen, Martha, Joann Vanek, Francine Lund, James Heintz, Renana Jhabvala and Christine Bonner (2005) Progress of the World’s Women 2005: Women, Work & Poverty, New York: United Nations Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM).

- Cheng, Grand H. L. and Darius K. S. Chan (2008) ‘Who suffers more from job insecurity? A meta-analytic review’, Applied Psychology 57(2): 272–303.

- Churchill, Brendan and Lyn Craig (2019) ‘Gender in the gig economy: men and women using digital platforms to secure work in Australia’, Journal of Sociology 55(4): 741–761.

- Crompton, Rosemary Jane Dennett and Andrea Wigfield (2003) Organisations, Careers and Caring, Bristol: Policy Press.

- Davis, B. S. Handa N. Hypher N. Rossi P. Winters and J. Yablonski (eds.) (2016) From Evidence to Action: The Story of Cash Transfers and Impact Evaluation in Sub-Saharan Africa, Oxford, New York: FAO, UNICEF, OUP.

- Farrell, D., F. Grieg, and A. Hamoudi (2018) The Online Platform Economy in 2018: Drivers, Workers, Sellers and Lessors, New York: JP Morgan Chase Institute.

- Galperin, Hernan (2021) ‘“This gig is not for women”: gender stereotyping in online hiring’, Social Science Computer Review 39(6): 1089–1107.

- Gerber, Christine (2022) ‘Gender and precarity in platform work: old inequalities in the new world of work’, New Technology, Work and Employment 37(2): 206–230.

- Graham, Mark and Mohammad Amir Anwar (2018a) ‘Labour’, In Ash, J., Kitchin, R. and Leszczynski, A. (eds.) Digital Geographies, London: Sage Publishing, 177–187.

- Graham, Mark and Mohammad Amir Anwar (2018b) ‘Two models for a fairer sharing economy’, In Davidson, N., Finck, M. and Infranca, J. (eds.) The Cambridge Handbook of the law of the Sharing Economy, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 328–340.

- Graham, M. and M.A. Anwar (2019) The global gig economy: towards a planetary labour market? First Monday 24. https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v24i4.9913.

- Graham, Mark Villi Lehdonvirta Alex Wood Helena Barnard Isis Hjorth and David Simon (2017) The Risks and Rewards of Online Gig Work at the Global Margins, Oxford: Oxford Internet Institute.

- Green, A. (2000) ‘Problems of measuring participation in the labour market’, in Dorling, Danny and Simpson, Stephen (eds.) Statistics in Society: The Arithmetic of Politics, London: Arnold, 312–323.

- Green, Francis (2006) Demanding Work: The Paradox of job Quality in the Affluent Economy, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Howcroft, D. and B. Bergvall-Kåreborn (2019) ‘A typology of crowdwork platforms’, Work, Employment and Society 33(1): 21–38.

- Hunt, Abigail E. Samman S. Tapfuma G. Mwaura R. Omenya K. Kim S. Stevano and A. Roumer (2019) Women in the Gig Economy: Paid Work, Care and Flexibility in Kenya and South Africa, London: Overseas Development Institute.

- Huws, Ursula N. H. Spencer D. Syrdal and K. Holts (2017) Work in the European Gig Economy: Research Results from the UK, Sweden, Germany, Austria, the Netherlands, Switzerland and Italy, Hatfield: FEPS/Uni Global/University of Hertfordshire.

- ILO (2016) ‘Non-standard employment around the world: understanding challenges, shaping prospects’, Geneva.

- ILO (2018) ‘Women and men in the informal economy: a statistical picture’, Geneva.

- ILO (2021) ‘World employment and social outlook: the role of digital labour platforms in transforming the world of work’, Geneva.

- ILO (2020) ‘World employment and social outlook: trends 2020’, Geneva.

- ILO (2022) ‘World employment and social outlook: trends 2022’, Geneva.

- Insight2impact (2019) ‘Africa’s digital platforms and financial services: an eight-country overview’, CENFRI, Cape Town.

- Jahoda, M. (1982) Employment and Unemployment: A Social-Psychological Analysis, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

- James, Al (2022) ‘Women in the gig economy: feminising ‘digital labour’’, Work in the Global Economy 2(1): 2–26.

- Kalleberg, Arne (2013) Good Jobs, Bad Jobs: The Rise of Polarized and Precarious Employment Systems in the United States, 1970s to 2000s, New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Kinyanjui, Mary (2014) Women and the Informal Economy in Urban Africa: From the Margins to the Centre, London: Zed Books.

- Kuek, S. C. C. Paradi-Guilford, T. Fayomi, et al. (2015) The Global Opportunity in Online Outsourcing, Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Leung, M. D. and S. Koppman (2018) ‘Taking a pass: how proportional prejudice and decisions not to hire reproduce gender segregation’, American Journal of Sociology 124(3): 762–813.

- Madgavkar, A. J. Manyika M. Krishnan K. Ellingrud L. Yee J. Woetzel M. Chui H. Hunt and S. Balakrishnan (2019) ‘The future of women at work: Transitions in the age of automation’, McKinsey Global Institute: New York.

- McDowell, Linda (2001) ‘Father and ford revisited: gender, class and employment change in the new millennium’, Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 26(4): 448–464.

- Moussié, Rachel and Laura Alfers (2018) ‘Women informal workers demand child care: shifting narratives on women’s economic empowerment in Africa’, Agenda (Durban, South Africa) 32(1): 119–131.

- Neumark, D. and M. McLennan (1995) ‘Sex discrimination and women’s labor market outcomes’, The Journal of Human Resources 30(4): 713–740.

- Otieno, E. M. Stein and M. A. Anwar. (2020) ‘Ride hailing drivers left alone at the wheel: experiences from South Africa and Kenya’, in P. Carmody, G. McCann, C. Colleran and C. O’Halloran (eds.) COVID-19 in the Global South: Impacts and Responses, Bristol: Bristol University Press.

- Prassl, Jeremias (2018) Humans as a Service: The Promise and Perils of Work in the gig Economy, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Ravenelle, Alexandra (2019) Hustle and Gig: Struggling and Surviving in the Sharing Economy, Oakland, California: University of California Press.

- Research ICT Africa (2017) What is the State of Micro-Work in Africa? A View from Seven Countries, Cape Town: Research ICT Africa.

- Rogan, Michael and Laura Alfers (2019) ‘Gendered inequalities in the South African informal economy’, Agenda (durban, South Africa) 33(4): 91–102.

- Samuel, V.J. (2020) ‘Uberizing informality: the case of non-owner, driver-partners in the city of Hyderabad’, The Indian Journal of Labour Economics 63: 511–524.

- Schor, Juliet (2020) After the Gig: How the Sharing Economy Got Hijacked and How to Win It Back, Berkeley: University of California.

- Sen, Amartya (1990) ‘Gender and cooperative conflicts’, in I. Tinker (ed.), Persistent Inequalities: Women and World Development. New York: Oxford University Press, 123–149.

- Standing, Guy (2014) ‘The precariat: the new dangerous class’. London; New York: Bloomsbury.

- De Stefano, V and Antonio Aloisi (2019) ‘Fundamental labour rights, platform work and human rights protection of non-standard workers', in J. R. Bellace and B. ter Haar (eds.) Research Handbook on Labour, Business and Human Rights Law, (pp. 359–379), Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Stephany, Fabian Otto Kässi Uma Rani and Villi Lehdonvirta (2021) ‘Online labour index 2020: new ways to measure the world’s remote freelancing market’, Big Data & Society 8(2): 205395172110432. doi:10.1177/20539517211043240.

- THE and IESALC (2022) ‘Gender equality: how global universities are performing’, https://www.iesalc.unesco.org/en/2022/03/08/global-universities-address-gender-equality-but-gaps-remain-to-be-closed/.

- Tsikata, Dodzi (2008) ‘Informalization, the informal economy and urban women’s livelihoods in Sub-Saharan Africa since the 1990s’, in Razavi, Shahra (ed.) The Gendered Impacts of Liberalization: Towards Embedded Liberalism, London: Routledge, 131–162.

- Tsikata, Dodzi (2009) ‘Women’s organizing in Ghana since the 1990s: from individual organizations to three coalitions’, Development 52: 185–192.

- Wood, Alex, Mark Graham and Mohammad Amir Anwar (2020) ‘Minimum wages for online labor platforms? regulating the global gig economy’, in Larsson A and Teigland R (eds.) ‘The Digital Transformation of Labor: Automation, the Gig Economy and Welfare, London: Routledge, 74–79.

- Woodcock, Jamie (2020) ‘The algorithmic panopticon at Deliveroo: measurement, precarity, and the illusion of control’, Ephemera: Theory & Politics in Organization 20(3): 67–95.

- Woodcock, Jamie and Mark Graham (2019) The Gig Economy: A Critical Introduction, Cambridge: Polity.

- World Bank (2016) ‘World development report 2016: digital dividends’, World Bank, Washington, DC.