ABSTRACT

Institutional strengthening, securitisation, free market promotion, and development policy implementation are foundational elements of liberal peace. However, the creation of an inferior colonisable other sustains this link and has justified programmes of violent repression and silencing. Decolonial, post-liberal, localised, and feminist peace-building stances condemn those power structures and promote alternative means of achieving well-being and social transformation. Women have played a significant role in these struggles in Colombia. Among other initiatives, feminist and women’s social movements have embraced works of memory, including museums of memory, as mechanisms to produce difficult knowledge about their painful past and alternative ways to build peace. This article explores the role of women in peace-building process via case studies of two community-based museums of memory in Colombia. Cases analysed embody ways in which knowledge is created regarding war, suffering, and reflection on the significance of living a dignified life, pursuing well-being, social justice, and peaceful coexistence. Memories gathered in these museums not only recount victimising incidents but also testify to how women elevate the discussion about the colonial and patriarchal roots underpinning Colombia’s decades-long armed conflict, and how it relates to development. Findings contribute to the discussion on the challenges of peace building, which include imagining roles for women in producing knowledge beyond the stereotypes that are imposed on us, even in peace.

Le renforcement institutionnel, la titrisation, la promotion du libre marché et la mise en œuvre de politiques de développement sont des éléments fondamentaux de la paix libérale. Cependant, la création d'un autre inférieur et colonisable maintient ce lien et a justifié des programmes de répression et de réduction au silence violentes. Les positions décoloniales, postlibérales, localisées et féministes condamnent ces structures de pouvoir et promeuvent d'autres moyens possibles de parvenir au bien-être et à la transformation sociale. Les femmes ont joué un rôle considérable dans ces luttes en Colombie. Entre autres initiatives, les mouvements féministes et les mouvements sociaux de femmes ont adopté des travaux de préservation de la mémoire, y compris des musées de la mémoire, comme mécanismes visant à produire des connaissances délicates sur leur douloureux passé et des façons alternatives de consolider la paix. Cet article examine le rôle des femmes dans le processus de construction de la paix à travers des études de cas sur deux musées de la mémoire communautaires en Colombie. Les cas analysés incarnent des façons dont les connaissances sont créées en matière de guerre, de souffrance et de réflexion sur l'importance de vivre une vie digne et de rechercher le bien-être, la justice sociale et la coexistence paisible. Les souvenirs rassemblés dans ces musées non seulement relatent des incidents « victimisants », mais témoignent également de la manière dont les femmes rehaussent la discussion sur les racines coloniales et patriarcales qui sous-tendent le conflit armé qui a duré plusieurs dizaines d'années en Colombie, et sur ses liens avec le développement. Les conclusions contribuent à la discussion sur les défis de la consolidation de la paix, notamment au moment d'imaginer des rôles pour les femmes dans la production de connaissances au-delà des stéréotypes qui nous sont imposés, même en temps de paix.

El fortalecimiento institucional, la titularización [securitisation], la promoción del libre mercado y la aplicación de políticas de desarrollo constituyen elementos fundacionales de la paz liberal. Este vínculo sostiene la creación de un otro colonizable inferior y ha justificado campañas de represión violenta y silenciamiento. Las posturas decoloniales, posliberales, localizadas y feministas de consolidación de la paz condenan estas estructuras de poder y promueven el uso de medios alternativos para lograr el bienestar y la transformación social. En Colombia, las mujeres han desempeñado un papel importante en estas luchas. Entre otras iniciativas, los movimientos sociales feministas y de mujeres han hecho suyas diversas obras encaminadas a salvaguardar la memoria, incluyendo los museos de la memoria como mecanismos para producir conocimientos difíciles sobre su doloroso pasado y como formas alternativas de construir la paz. Partiendo del estudio de dos casos de museos comunitarios de la memoria en Colombia, este artículo explora el papel desempeñado por las mujeres en el proceso de construcción de la paz. Los casos analizados dan cuenta de las formas en que se crea conocimiento sobre la guerra y el sufrimiento, al tiempo que impulsan la reflexión sobre el significado de vivir una vida digna, procurar el bienestar, la justicia social y la coexistencia pacífica. Las memorias recogidas en estos museos no sólo evidencian incidentes victimizantes, también dan testimonio de cómo las mujeres elevan el debate sobre las raíces coloniales y patriarcales que subyacen al conflicto armado colombiano, que se ha extendido durante décadas, y de su relación con el desarrollo. Las conclusiones contribuyen al diálogo sobre los desafíos que supone la consolidación de la paz, entre los que se incluye imaginar funciones para las mujeres en la producción de conocimientos más allá de los estereotipos que se nos imponen, incluso en periodos de paz.

Introduction

Museums are powerful knowledge-building devices and have been tools for shaping notions of heritage, nationhood, beauty, and power. Although this role has been governed by academic and social elites, when subverted by other communities, museums bring different issues to the fore. In Colombia, community-based museums of memory have emerged as a significant means for victims and survivors to cope with the aftermath of violence and armed conflict. This practice has gained significant momentum, with an increasing number of such institutions emerging across the nation. Over 25 identifiable locations, dwellings, or museums are exclusively dedicated to preserving and communicating narratives about the violence associated with armed conflict (Guglielmucci Citation2018; Red de Sitios de Memoria Latinoamericanos y Caribeños RESLAC Citationn.d.). These memory initiatives are emblematic of the symbolic dimensions of resistance and opposition to war and the various underpinnings that enable it. They allow for an appreciation of the organisational processes involved in confronting violent settings and provide insights into how such contexts’ social, economic, and political structures are contested and resisted. These museums are not merely devices for collecting or systematising information or repositories of stale records of past events; they are platforms that bring memories to life and concentrate and mobilise political action. This study is based on two of the most significant community-based museums of memory in Colombia: the Museo Itinerante de la Memoria y la Identidad de los Montes de María ‘El Mochuelo’ (Itinerant Museum of Memory and Identity of the Montes de Maria, hereafter El Mochuelo),Footnote1 and the Casa Museo de la Memoria y los Derechos Humanos de las Mujeres (House Museum of Memory and Human Rights for Women, hereafter referred to as the Women’s House).

The involvement of women in endeavours related to memory that seek to promote social transformation and peace building has been pivotal. Women have assumed a leadership role in these efforts, engaging in women’s movements, feminist movements, research, cultural management, and even in the domestic sphere. They have publicly denounced the direct effects of violence perpetrated by legal and illegal actors, and have mobilised to resist the damaging effects of war, utilising various forms of protest, such as marching, and utilising their own bodies, even feeding activists.Footnote2

The literature on gender and conflict has documented the significance of women’s movements in the pursuit of peace (Gizelis Citation2011, Citation2018). As memory entrepreneurs (Jelin Citation2002), women have played a key role. This phenomenon can be attributed to the differing effects of violence on women and men, leading women to spearhead efforts to resist the brutal silencing and forgetting of their loved ones who were victims of violence. They have understood memory as a work of caring for their own, present and absent (Gómez Correal CitationForthcoming). In this way, women have demanded and advocated processes of non-repetition. However, this emphasis on women’s agency in memory-related efforts should not be misconstrued as an assertion of women’s exclusive responsibility in this domain. Rather, my objective is to underscore the distinctive forms of memory work and explanations that are instigated when women are protagonists.

Community-based museums of memory embody a mechanism utilised by collectives of women to amplify their endeavours in the pursuit of peace. These museums emerge from grassroots efforts and are reliant on the co-operative work of young individuals, families of victims, activists, human rights defenders, and cultural managers. These museums create some distance from state memory policies and official agendas, providing an alternative platform serving the demand for memory, justice, and political consciousness. By producing a more complex understanding of reality, which accounts for long memories or the situation of groups that have been subordinated, they can discuss the colonial and patriarchal foundations that have shaped the conflict.

In community-based museums of memory, the localised impacts of violence on particular communities are brought to the forefront, as are the various measures taken by individuals and communities to condemn, withstand, and halt its progression. Nevertheless, these museums extend beyond mere representation, and my research is premised on the hypothesis that these devices, especially for women, function as tools for drawing attention to the patriarchal and colonial underpinnings of their lived experiences. In this process, these museums have become a means of initiating alternate pathways for pursuing a peaceful coexistence and achieving overall well-being.

Museums, as institutions that disseminate and popularise knowledge, are not immune to the broader social dynamics of a gendered division of labour. These institutions have consolidated tendencies that associate the meticulousness and dedication involved in museographic workFootnote3 with feminine attributes, thus perpetuating gendered stereotypes in the workplace (Echeverri Citation1998). As a result, just like care work, education, and domestic maintenance, museums represent yet another setting that exposes gender-based divisions of labour, showcasing their distinct features of uncertain wages or lack thereof, undervaluation, and invisibility.Footnote4

Hence, museums of memory appear to be a vortex through which the feminine and the feminised are inevitably interwoven in the various tasks of the memory work. In this regard, community-based museums of memory are archetypal. Women’s participation within organisations of victims, survivors, mothers, or relatives, as well as their leadership in exhibition design, research, and management, has been decisive in shaping specific ways of making collective memory and turning it into a tool for social transformation.

What do museums tell us about the confluence of memory and peace that revolves around women? Indeed, to what extent does an institution such as the museum, which has been exposed as a mechanism of colonial, white, and Eurocentric domination, serve to discuss ways of producing knowledge and its relationship with feminist decolonial peace building?

This article explores the question of how community-based museums, focusing on violence and armed conflict in Colombia, shed light on the role of women in peace building. In essence, it investigates the extent to which these museums contribute to a feminist and decolonial approach to peace building.

This text is organised in four parts. The next section explores the literature on women and peace, and suggests a discussion incorporating decolonial feminism’s ideas and contributions. The study’s two community-based museums of memory are introduced afterwards, which also includes details on the methodology. The third section presents an overview of the thematic content of museums centred on violence, as well as the economic factors connected to extractive practices and development ideologies in the respective regions. Reflections on the relationship between women, memory, peace, and knowledge production are included in the conclusion.

The north–south of the debates on women, peace building, and knowledge production

The dichotomous approach to the mechanisms of social and institutional transformation that led to peace is now well-established. On the one hand, the liberal tradition attributes the emergence and endurance of conflict to institutional fragility and the lack of effective regulation. To address this, it emphasises the strengthening of the rule of law, the implementation of governance and public policy systems, and the promotion of free markets, security, democracy, and development (Richmond Citation2010). The liberal peace paradigm relies on the enlistment of national elites in complex international alliances that go beyond independent legal states and involve international agencies, NGOs, and increasingly privatised and militarised governance networks (Duffield Citation2001).

Critical peace studies have contested the liberal approach on various fronts. For example, they have highlighted the contradiction between the humanist rhetoric used to justify international interventions and the means used, which generate anti-democratic outcomes (Paris Citation2004). They have also criticised the tendency to view marginalised sectors as powerless victims without agency and the eagerness to transplant aid packages or policies from the North to the South. In addition, they have argued that the liberal approach is blind to cultural or everyday practices that exist outside ‘developed’ contexts, and this justification of inequality is based on illiberal otherness (Richmond Citation2011).

McLeod and O’Reilly (Citation2019) have drawn on Richmond’s (Citation2010) model of four perspectives in peace and conflict studies scholarship to account for the marginalisation of feminist theories, the gender unexamined gaps in these approaches, and the consequent reproduction of patriarchal ideas in peace-building practices. In particular, they scrutinise a ‘cult of power’ that marginalises the perspectives and contributions of relatively ‘powerless’ non-state actors, including many women, girls, and non-binary people. This creates the impression that conflict and war are genderless phenomena, as it omits context-specific gendered power structures and thus (re)produces a ‘patriarchal gender order’ that reinforces, rather than disrupts, hierarchical structures and power relations.

Despite this context, research on women and peace has persisted in reclaiming its rightful place, and the rhetoric of women as being in need of protection has given way to a greater awareness of their active role in the pursuit of peace. Studies on women, conflict, and peace have discussed various aspects by accounting for the three facets of conflicts: risk, dynamics, and resolution. These aspects include the transformation of gender relations that sustain a militaristic and violent logic even in peace (Cockburn Citation2013); the conditions of inequality that lead to and sustain the intensity and duration of intra-state conflicts (Caprioli Citation2005; Forsberg and Olsson Citation2021; Justino et al. Citation2018; Melander Citation2005); and the differentiated violence experienced by women, such as sexual and gender-based violence (Kreft Citation2020; Skjelsbæk Citation2001). Additionally, these studies have explored the role of women in shaping informal social networks that increase their empowerment and social capital, thereby reducing the risk of returning to the war (Gizelis Citation2021); the increase in women’s post-conflict collective actions that have led to reshaping their societies, rewriting some rules, and achieving improvements in political participation and access to resources (Arostegui Citation2013; Faxon et al. Citation2015); and women’s participation in peace process negotiations (Boutron Citation2018; Gómez Correal and Montealegre Citation2021; Krause and Olsson Citation2020; Krause et al. Citation2018).

The literature focusing on women and peace has been subject to criticism for being heavily influenced by the dominant white Eurocentric scholarship of the global North. While acknowledging the important work of academic and activist feminisms in exposing the patriarchal structures of peace building and their conceptualisation, the modern/colonial legacy continues to shape the theoretical landscape, thus privileging certain research agendas, methods, and normative frameworks. This issue underscores the impact of the coloniality of knowledge (Lander Citation2000) and raises questions about which voices have been able to express and analyse the experiences of racialised, indigenous, and mestizo women,Footnote5 and the extent to which those voices have been recognised as authoritative.

Decolonial feminist perspectives aim to address this issue (Ballestrin Citation2017; Espinosa-Miñoso Citation2014; Guzmán Arroyo Citation2019; Lugones Citation2010; Rivera Cusicanqui Citation2010). While they share the notion of feminist epistemologies that criticise the paradigms that have marginalised women in knowledge production and scientific practice (Haraway Citation1995; Harding Citation1996; Velez and Tuana Citation2020), they have also challenged the marginalisation that occurs when the interweaving of oppression systems related to race, class, gender, and sexuality are excluded from the analysis. Therefore, as an epistemic choice, this current movement recovers the critiques made by marginalised and subaltern voices towards white, bourgeois, and Eurocentric feminisms (Espinosa-Miñoso Citation2014), and echoes the theoretical tradition initiated by black feminism, the contributions of indigenous women in Latin America, and those who dissent from normative heterosexuality (de Santiago Guzmán et al. Citation2017; Espinosa Miñoso et al. Citation2014; Ruiz Trejo Citation2020).

Engaging in dialogue with intellectuals and activists who discuss the modern–colonial matrix of domination (Dussel Citation1994; Escobar Citation2003; Quijano Citation2000), decolonial feminism posits that the imposition of categorisation based on race, gender, and labour has shaped the global capitalist order. This categorical division conditions every aspect of social existence, both material and subjective, and serves as the foundation of contemporary inequalities. Although the colonial period has concluded, modernity remains incomprehensible without addressing its dark underbelly: the racist and extractive economic and social system that supported the cultural and ideological revolution and the dominance of modern, secular, commodified logic. Thus, racialised, and capitalist gender oppression form the basis of ‘gender coloniality’, as described by Lugones (Citation2010). Thus, decolonial feminism offers the possibility not only to theorise but also to transcend these intersecting systems of oppression.

These theoretical perspectives provide a framework for analysing studies that explore the relationship between women and peace (CINEP Citation2020; Jaime-Salas et al. Citation2020). For instance, these perspectives have been employed to analyse the Colombian case, where they have revealed the contradictions of a peace built on extractivist models that conceal structures of exploitation under the guise of post-liberalism (Hernández Reyes Citation2019; Montealegre Citation2023; Moreno Sierra and de León Jaramillo Citation2020; Paarlberg-Kvam Citation2021). Despite revealing neglected aspects of peace building, these perspectives remain under-represented and under-theorised (Hudson Citation2016).

This text contributes to this conversation in two ways. First, it draws attention to feminist, decolonial, and subaltern epistemes that expose the violent domination exercised by transnational social, economic, and political systems of development ideals, particularly on women. In doing so, it critiques the neglect of the colonial or patriarchal roots of such structures. Second, it emphasises that the theoretical and methodological stakes taken by women to address these issues enrich not only the tradition of critical peace studies but also contribute to situating knowledge produced from the margins in the balance of epistemic justice.

A bird and a house: community-based museums as methodological lenses

My study seeks to examine the impact of such recognition on the reconfiguration of innovative practices of knowledge production. Community-based museums of memory offer a valuable vantage point from which to consider the efforts of these women and their peace-building initiatives from a unique and insightful perspective.

My career trajectory, initially as a museum exhibition designer and subsequently as a museum researcher, has instilled in me the belief that museums possess the potential to surpass the constraints imposed by dominant traditions in terms of their epistemic and political capacities. Building upon this perspective, my methodological approach posits community-based museums of memory as critical lenses for the examination of women’s actions and motivations in the memory work that underpins peace building. Importantly, this analytical framework also facilitates the interrogation of gendered assumptions and stereotypes that continue to limit the recognition of women’s multifaceted contributions to knowledge production, even in the context of peace.

For this study,Footnote6 I have worked with two Colombian community-based museums of memory in the framework of a multiple case study (Yin Citation2004): El Mochuelo and Women’s House. The former is affiliated with the Colectivo de Comunicaciones de Montes de María Línea 21 (Montes de María Communications Collective Line 21, hereafter the Collective), an organisation that employs communication, education, and cultural management to effect transformative change in their region. The latter is associated with the Organización Femenina Popular (Popular Women’s Organisation, hereafter OFP), one of the oldest women’s organisations in Colombia.

El Mochuelo is an itinerant pavilion that travels around the main squares of the municipalities of the Montes de María region. It offers a depiction of the violent events that have transpired in the region, as well as the corresponding efforts of local inhabitants to resist and overcome these challenges. It draws upon nearly three decades of work by the Collective, which has travelled throughout the region to facilitate dialogue around memories of conflict, amplify the voices of the campesinos (peasantry),Footnote7 and illuminate the political agenda of the community. In conjunction with the Montes de María Audiovisual Festival, this travelling museum showcases the Collective’s endeavours aimed at augmenting citizen participation in the region and has evolved into one of the most significant points of reference for community museology in the country (Bayuelo Castellar et al. Citation2013).Footnote8

The Women’s House serves as a comprehensive representation of the OFP’s 50-year history. It is located in one of the traditional neighbourhoods of Barrancabermeja, one of the most important cities in the Magdalena Medio region. The OFP, operating from a popular feminist perspective, envisions the creation of dignified life projects capable of transforming the social reality of women through daily, civil, and autonomous actions. Its origin traces back to Barrancabermeja, where Catholic priests from Pastoral Social, followers of Liberation Theology,Footnote9 formed housewives’ clubs to provide training sessions that enabled women to initiate processes of economic independence. The OFP became independent of the Catholic Church in 1988. Funds from Austrian women enabled the creation of the first Women’s House independent of the Pastoral Social (Lamus Canavate Citation2010). This marked a milestone for the movement, as it embodied the principle of autonomy, a core value embraced by the OFP. Consequently, the focus of the work shifted towards addressing the specific needs and demands expressed by women, rather than conforming solely to the ‘dynamics of the church itself’ (as stated by a social leader quoted in Bernal Cuellar 2014). From that point on, similar Women’s Houses were established in other municipalities, and became spaces not only for meetings but for raising awareness about the abuse, contempt, and domination experienced in their homes and communities, just because of their gender.

By the mid-1990s, when the armed conflict in the Magdalena Medio region escalated, the OFP not only expanded its geographical scope but also increased its resistance actions against violence. Today, the organisation’s actions are centred on recognising, valuing, and positioning women as political subjects, beyond just their role as victims or witnesses of violence. This demand is based on the principle of autonomy on multiple levels, from recognising the value of their roles in the private sphere to dissociating themselves from the state, militarised, or economic apparatuses that hold power and have sustained the war (Obando et al. Citation2021).

The methodology for the study entailed various strategies, such as conducting interviews, engaging in participant observation, and conducting participatory research. These activities spanned a period of almost three years, from 2021 to 2023. Fourteen interviews constituted the initial phase of the research. I selected participants including women co-ordinators from the organisations, as well as professionals responsible for museum management, pedagogical strategies, and project design. The participatory nature of the research was facilitated by my partial integration as a member of the organisations’ teams, serving either as an exhibit designer or a workshop leader. In particular, the collaborative phase with the Collective consisted of enrolling myself as a part of the team during the three recent tours of the museum, which included being part of the formulation, design, museography, pedagogy, and even management teams. The observation of museum exhibits and interviews provided an initial foundation for comprehending the overall characteristics of the studied organisations responsible for museums. Nonetheless, it was through engaged research that I gained insight into the specific social, political, and economic circumstances these leaderships groups aimed to address, the demands that drove these struggles, and, most importantly, the role of women in these dynamics. Consequently, the examination includes an ‘inward’ review of the contents of the memories that shaped the museography and, simultaneously, an ‘outward’ approach that links these contents to other dimensions of collective action. The primary objective of the data analysis was to identify and compare similarities and patterns present in both cases.

Oil and lands: museums addressing political economy

Inquiring into the interplay of memory and peace as it pertains to women, one may seek insight from these community-based museums of memory. Indeed, these repositories offer an account of the colonial and patriarchal power structures that have propelled the armed conflict in Colombia.

This argument is supported by similarities in the thematic frameworks about socioeconomic aspects that are portrayed in the exhibitions of both museums. The museums also share methodological deployments that shape these contents. However, due to space constraints, I will focus on what is depicted in the exhibitions rather than the methodological approach. To provide context to the narratives and processes that lead to their creation, a preliminary overview of the regions in which the museums are situated follows.

Natural resources and violence

Women’s House and El Mochuelo depict the historical accounts of two regions in north-central Colombia, the Magdalena Medio and Montes de Maria, correspondingly. The boundaries of these regions are inextricably linked to the Magdalena River, the country’s most important water corridor. They are recognised for their abundance of natural resources and belong to crucial sectors of the Colombian economy, predominantly agriculture and energy production. At the same time, these areas have been gravely affected by the armed conflict. Both of these regions have experienced a concentration of victimising incidents linked to the recent armed conflict, including targeted assassinations, massacres, kidnappings, land dispossession, massive displacement, and sexual and gender violence. Consequently, they have become recognised as some of the most violent areas in the country, ‘the red spots’.

The region of Magdalena Medio covers approximately four million hectares (40,000 m2) and is located in the central part of Colombia, where nearly one million people reside (Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica Citation2019; Dávila Benavides Citation2007). The Women’s House highlights the region’s ecological and economic characteristics, including: the contribution of over half of Colombia’s extracted oil, the production of 70 per cent of the country’s hydroelectric energy, and the existence of mining titles covering almost two million hectares (20,000 m2) that contain uranium, gold, and coal deposits. The region has experienced extensive deforestation, with almost all of its territory dedicated to monoculture plantations of palm, rubber, cocoa, and extensive cattle ranching; leading to the use of large volumes of water and the disposal of hazardous substances (Rinaldi Citation2023).

On the other hand, El Mochuelo’s narrative focuses on the Montes de María region, located in the Colombian Caribbean, with around one million people and covering approximately 650,000 hectares (6,500 m2) of mountainous, riverside areas, where the productive vocation is 41 per cent agriculture, 5 per cent livestock, and 48 per cent forestry. In the rural zone, however, 67.2 per cent have difficulty accessing water, 85.2 per cent do not have technical assistance, and 92.8 per cent do not have production machinery (Presidencia de Colombia Citation2018). Yet, since it is located between the Magdalena River and the Caribbean Sea, the Montes de María sub-region has been considered a key corridor for the extraction of legal and illegal goods.

Women who belong to the work communities of the Collective and the OFP in these regions are subject to various intersecting systems of ethnic, class, and labour stratification. They are women who have been racialised and are descendants of the multiethnic mix of settlers, native peoples of the Zenú basin, and enslaved Africans who escaped from the Caribbean coast to the interior of the continent (Moreno Sierra and de León Jaramillo Citation2020). In the Montes de María region, the rural population constitutes 42 per cent, and more than 90 per cent of that rural population live in poverty or extreme poverty. The number of people displaced by conflict in the region exceeds 225,000, which represents over 70 per cent of the total population. In Magdalena Medio, the demographic trend is leaning towards urbanisation, with an average of 70 per cent of the population living in urban centres. However, when combined with the rural areas, the percentage of people with unmet basic needs increases to 47 per cent, with 22 per cent living in extreme poverty. It is the women who labour in the fields, attend to their households, or engage in pedagogy amidst harsh conditions who have emerged as the foremost leaders of community-based organisations. These are the women depicted in museum displays both as subjects of oppression and as promoters of the transformation of their environments.

In response to the multifaceted nature of the violence they went through, women’s social movements have employed works of memory as a form of resistance and knowledge production (Ibarra Melo Citation2007). Community memory museums have emerged as a means to centralise the outcomes of these memory works. In their dissemination, these museums have amassed more than just a collection of objects. El Mochuelo and the Women’s House embody the lengthy history of these mobilisations that emphasise how knowledge is created regarding war, suffering, and reflection on the significance of living a dignified life, pursuing well-being, justice, and peaceful coexistence. The memories gathered in these museums not only recount victimising incidents but also testify how people resist war and strive to live peacefully.

The struggle for land and the dignity of life

El Mochuelo and the Women’s House document the lessons learnt from the history of the region, including issues related to land tenure, expropriation, and conversion of land use to extractivism, extensive livestock, and monocultures. El Mochuelo’s narrative centres on the life of peasants. The image of a peasant carrying cassava roots is particularly noteworthy, as it highlights the value of cultivated land in the narrative (). It encapsulates the three conceptual axes that underpin museology: territory, memory, and cultural identity. Peasant work is a dimension that feeds memory. It accounts for the consequences of the agrarian colonisation that the region has experienced since the 18th century, associated with the production of tobacco and cotton, which displaced the Zenú indigenous people who originally inhabited these lands. It also speaks to the experience of dispossession and stigmatisation they have suffered in the context of recent violence.

Figure 1. Temporary exhibition of El Mochuelo Colectivo de Comunicaciones de Montes de María Línea 21 El Carmen de Bolívar, 2022.

Displacement due to extreme inequality in land distribution has been a longstanding issue afflicting Colombia. The concentration of land in the landlord model of ‘haciendas’ or latifundia has dominated the configuration of many Colombian territories since the end of the 19th century. The exhibition depicts Fals-Borda’s (Citation2002) ‘law of the three steps’, which elucidates the relationship between the expansion of the agricultural frontier and land dispossession: first, the working and producing settler enters, deforesting and sowing to obtain a profit in the short term; then the farmer buys the improved land; and finally, the hacendado (landlord) comes in to consolidate plots and monopolise the land, usually for cattle farming ().

Figure 2. ‘Law of the Three Steps’, temporary exhibition of El Mochuelo, Colectivo de Comunicaciones de Montes de María Línea 21, Bogotá, 2023.

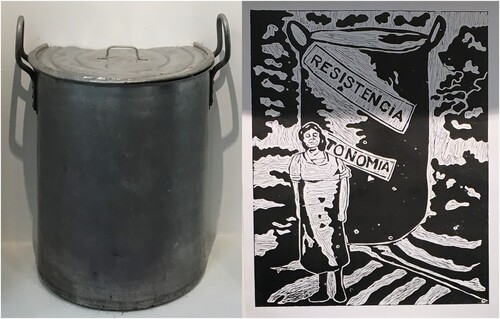

On the other hand, by accentuating the symbolic dimension that the OFP has employed for half a century, Women’s House highlights the role of women’s organisations in light of the adverse impacts of the oil industry on the ecological conditions of the region, the trade union association’s criminalisation, and the differentiated violence faced by women (). Exhibitions portrays the quotidian – even mundane – materialities that women in these struggles have embraced: sewing machines, cooking pots, gardens, and also clothes and banners used in massive demonstrations where they dressed in black, carried flowers, and marched on the streets ().

Figure 3. ‘Fracture, Self and Earth’. Video sequence in Women's House. Corporación Compromiso Barrancabermeja 2022.

Retaining their specific focus, the historical narratives of both museums expose the interconnection between memories of sociopolitical violence and the economic dimensions of the respective regions. The museums share a thematic selection and chronological framework, thus highlighting the pivotal role of women in countering these circumstances in two distinct domains: the fight for land and the quest for a dignified life.

For instance, both timelines begin with the period between 1915 and 1925, which marks the onset of conflicts over land and subsequent social mobilisation. The expansion of latifundia for livestock and tobacco economies, the initiation of oil extraction in Barrancabermeja by the Tropical Oil Company in 1918, and conflicts over the ownership of properties that settlers occupied are listed among the events that set the tone for the relevance of the vocation of the territories and the conflicts that followed.

The simultaneity between the adoption of neoliberal economic models in laws or public policy models on economic and territorial development, social mobilisation, and the exacerbation of the conflict is also a topic addressed in the exhibitions.Footnote10 ‘We learned that Montes de María can no longer be reduced to a map of economic intervention, nor military intervention, nor consolidation, nor palm, nor teak, although they all call it development and invoke it as a banner’.Footnote11 Such mentions include the consolidation of unions, leagues, or associations representing workers, peasants, artisans, or youth; the mobilisations, strikes, or civic stoppages they promoted; the ensuing repression of these events that led to the assassination of leaders of such organisations; the rise of guerrilla movements and consequent legal and illegal counterinsurgency measures.

The omission of the connection between prevailing economic models and violence is noticeable in peace negotiations within transitional justice frameworks (Gómez Correal et al. Citation2020, Citation2021). On the contrary, the explicit acknowledgement that discussing the impacts of development is crucial to achieving peace is a notable aspect highlighted by these museums, challenging dominant notions of well-being.

The active role played by women in participating in decision-making processes to establish social order becomes apparent, underscoring the significance of collective efforts in the struggle. ‘Women have been the retaining walls’,Footnote12 as proclaimed by one of the successors of women leaders who defended the land rights of male and female peasants in Montes de María, holds true in examples such as Felicita Campos in the 1920s and Juana Julia Guzmán in the 1970s.Footnote13 Women acknowledge, and the museum highlights, the progress they have made in organising themselves to achieve their demands in organisations such as the National Association of Rural Users of Colombia (ANUC), the Women’s Association for Emancipation (AFEM), the Departmental Association of Rural Housewives of Sucre (AMARS), and the OFP itself.

Women who are part of these organisations have played a crucial role in mobilising actions on the streets and in the public square. Nevertheless, an additional aspect of museographic strategies is the depiction of individual everyday or private roles, including responsibilities for maintaining daily life such as cooking, sewing, weaving, repairing clothing, or manufacturing cultural objects. The Women’s House, in particular, emphasises the necessity of politicising care work that has traditionally been the responsibility of women. The same spaces of these houses were places of contention during the war, where displaced people and those fleeing their oppressors took refuge, community dining rooms were organised, and temporary lodgings were established. These houses became ‘the nodes of a communications network hidden from the warlords’.Footnote14 Armed actors even claimed the houses, and in response, women refused to surrender the keys, which resulted in the houses being plundered and vandalised. Giant keys in the museum serve as a symbolic representation of these conflicts.

In brief, the chronology of the two territories reveals a juxtaposition of three aspects: the victimisation suffered by these groups or the general population, the economic policies that are not only presented as a backdrop but also as direct explanations of these phenomena, and the evolution of different forms of collective association. Each museum has placed specific emphasis on this relationship. The Women’s House has brought attention to the sinister and clandestine effects associated with oil exploitation, related unions, and the targeted killings of their members. El Mochuelo has emphasised factors associated with agriculture, peasant unions, and the phenomenon of mass displacement.

Final thoughts

El Mochuelo and the Women’s House are two community-based museums of memory that allow us to reflect on two aspects about peace building. First, they highlight the efforts of producing localised and critical knowledge about the roots of violence; and second, the benefits and challenges of engaging through a decolonial and feminist perspective in order to address comprehensively the intricacies between memory works and peace-building processes.

On the one hand, approaching these community-based museums of memory as a methodological lens reveals the usefulness of this kind of institution in framing topics that women want to speak about. Even in times of peace, women’s voices in the discussion of political economy issues are diminished. However, these memory works, as embodied in museums, shed light on the structures of social, economic, and political ordering, creating opportunities for women to discuss their scope and effects, and for implementing actions to counteract them.

These museums have provided insights into the impact of war and violence on women in Colombia, revealing the pain they have endured and the efforts they have made to overcome it. Furthermore, these museums serve as spaces for reflection on the underlying causes of these phenomena. Museographic strategies make evident the extent of women’s involvement in the discussion of socioeconomic structures that stem from colonial heritage, which have conditioned the violence in their environments.

On the other hand, feminist and decolonial lenses allow us to see how the work of memory embodied in these museums becomes part of the repertoires to care for life. So, we could see that the time and affections invested are active dimensions of collective action that seek well-being, a dignified life, and peace building.

Gender role stereotyping makes women seem more apt for museums and memory work since it extends women’s role as caretakers and projects it on to the protection of memory. However, this perspective neglects other ways of understanding their agency, in which they distance themselves from the imposition of the passive role and hide the struggle to dismantle deep classification structures that have historically sustained violence.

Therefore, it would be incorrect to promote another classification that puts care and activism on opposite sides, as if care tasks and mobilisation for peace were antagonistic. On the contrary, what the museum allows us to see about the confluence between memory and peace that revolves around women is that, based on the valuation of memory, which includes memories of pain and resistance, women play an active role in dismantling oppressive conditions.

Nevertheless, this should draw attention to the conditions of precariousness associated with care work, in this case, materialised in a double intersection between memory care and working as a museum professional. While recognising women’s peace-building efforts through memory museums, we must refrain from romanticising them, and instead shed light on the pressing issues of job instability, undervaluation, and invisibility that often accompany these endeavours. Understanding the unique conditions under which women engage in memory work is a critical subject for future research studies.

These museums represent a form of self-reflection and a product of the learning process that has resulted from community efforts. They serve as amplifiers of the discussions that have emerged from the heart of these communities and from the bodies of women who have endured the violence of the conflict. As such, they represent a commitment to subvert the hierarchical structure of knowledge subjected to subordination or even violent silencing. Modern times of which museums are inheritors taught us that the past should be overcome. However, by projecting the past forward instead of burying it behind our backs, these community museums challenge their own oppressive and marginalising heritage.

The perspective of decolonial feminism allows for the contextualisation of the efforts in these community-based museums of memory as part of a broader, longstanding struggle of marginalised communities. By diverging from dominant theoretical frameworks on peace, which have historically linked it to liberal or post-liberal ideals, the women supporting these museums problematise the consequences of this binary. They highlight structural and historical problems that cannot be remedied through economic intervention, humanitarian aid, or the strengthening of ties between local actors and elites. Instead, they propose a discourse that challenges the theories and theorists behind these issues. In these museums, women from impoverished, working-class, peasant, black, and mixed-race backgrounds, in non-institutionalised settings, encourage discussions on the dimensions of violence and the prerequisites for peace. Drawing upon Lugones’ (Citation2010) call, decolonial feminism enables us to recognise that these women’s efforts have unveiled an emancipatory horizon and are forging a collective path forward.

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge the Colectivo de Comunicaciones de Montes de María and the Organización Femenina Popular (OFP).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Diana Ordóñez Castillo

Diana Ordóñez Castillo is a PhD candidate in Development Studies at the Interdisciplinary Centre for Development Studies CIDER, Universidad de los Andes, Bogotá, Colombia. Postal address: Calle 18A # 0-19 Este. PU 203, Bogotá, Colombia. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 Mochuelo is the common name for a bird native to the Montes de María region.

2 The documentary Mujeres con los pies en la tierra (Down-to-earth Women), produced by the Collective, shows how women in the Montes de María area became involved in the mobilizations for the struggle for land. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dzI3xW28KZ0.

3 Museography refers to exhibition design practices, their materiality, graphic aspects, textual aspects, or interactivity. Museology is the theoretical and methodological approach that studies these practices and their effects.

4 For an example of this phenomenon in the context of peace building, see Jackie Kirk (Citation2004) on the role of female teachers.

5 Mestizaje, a controversial concept in Latin America, refers to the mixture of culture and biology among indigenous populations, enslaved Africans, and Europeans. It has been used for discriminatory purposes as well as for empowering identity projects, while gender perspectives highlight the inherent violence against women associated with it.

6 This study is part of the author’s doctoral research entitled ‘Community Memory Museums in Colombia: Perspectives from Emotions, Women and Peacebuilding’.

7 In Colombia, campesinos are recently acknowledged as a community with special rights. The term ‘peasant’ will be utilised in the text for clarity, but it only partly conveys the group’s experiences of subordination, and we should not forget the community’s significant struggles centre around land ownership, distribution, and the recognition of their societal contributions.

8 At the time of writing, and having completed nine tours in the Caribbean region, El Mochuelo is the featured guest exhibition in the temporary exhibition hall of the Museo Nacional de Colombia in the national capital, Bogotá, commemorating the museum’s 200th anniversary.

9 Liberation Theology holds a prominent place in Latin America’s Christian missionary history, calling for the defence of the rights of the oppressed and the poor. It has played a crucial role in shaping grassroots social, popular, and leftist movements in the region.

10 El Mochuelo, temporary exhibition at the Palace of Inquisition, Kiosk of Memory, Las Brisas, 2022.

11 Personal conversation with the Collective’s research co-ordinator, Italia Samudio, 2022.

12 Personal conversation with peasant leader, Catalina Pérez, 2022.

13 For a video about Felicita Campos: Women in the Peasant Struggle, see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qcfZgHaiIXo"https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qcfZgHaiIXo.

14 Personal conversation with OFP leader, Gloria Suárez, 2022.

References

- Arostegui, Julie (2013) ‘Gender, conflict, and peace-building: How conflict can catalyse positive change for women’, Gender & Development 21(3): 533–549. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552074.2013.846624.

- Ballestrin, Luciana (2017) ‘Feminismos Subalternos’, Revista Estudos Feministas 25(3): 1035–1054. https://doi.org/10.1590/1806-9584.2017v25n3p1035.

- Bayuelo Castellar, Soraya, Italia Samudio Reyes, and Giovanny Castro (2013) ‘Museo itinerante de la memoria y la identidad de los Montes de María: tejiendo memorias y relatos para la reparación simbólica, la vida y la convivencia’, Ciudad paz-ando. Estudios para la paz: representaciones, imaginarios y estrategias en el conflicto armado 6(1): 159–177.

- Bernal Cuellar, Diana (2014) ‘Historia de la Organización Femenina Popular en Barrancabermeja: 1998-2008’, [Master Thesis. Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia].

- Boutron, Camille (2018) ‘Engendering peacebuilding: The international gender nomenclature of peace politics and women’s participation in the Colombian peace process’, Journal of Peacebuilding & Development 13(2): 116–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/15423166.2018.1468799.

- Caprioli, Mary (2005) ‘Primed for violence: The role of gender inequality in predicting internal conflict’, International Studies Quarterly 49(2): 161–178. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0020-8833.2005.00340.x.

- Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica CHMH (2019) Ser marica en medio del conflicto armado, Bogotá: CNMH.

- CINEP (2020) Estudios críticos de paz: Perspectivas decoloniales, Bogotá: CINEP/Programa por la Paz.

- Cockburn, Cinthia (2013) ‘War and security, women and gender: An overview of the issues’, Gender & Development 21(3): 433–452. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552074.2013.846632.

- Dávila Benavides, Nilson (2007) Desplazamiento forzado en el Magdalena Medio 2005-2006, Barrancabermeja: Observatorio Paz Integral.

- de Santiago Guzmán, Alejandra, Edith Caballero Borja, and Gabriela González Ortuño (eds.) (2017) Mujeres intelectuales: Feminismos y liberación en América Latina y el Caribe, Buenos Aires: CLACSO.

- Duffield, Mark (2001) Global Governance and the new Wars: The Merging of Development and Security, London: Zed Books.

- Dussel, Enrique (1994) El encubrimiento del otro. Hacia el origen del mito de la modernidad, Quito: Ediciones Abya Yala.

- Echeverri, Marcela (1998) ‘La fundación del Instituto Etnológico Nacional y la construcción genérica del rol de antropólogo’, Anuario Colombiano de Historia Social y de la Cultura 25: 216–247.

- Escobar, Arturo (2003) ‘Mundos y conocimiento de otro modo. El programa de investigación de modernidad/colonialidad latinoamericano’, Tabula Rasa, 1: 51–86.

- Espinosa-Miñoso, Yuderkys (2014) ‘Una crítica descolonial a la epistemología feminista crítica’, El Cotidiano 184: 7–12.

- Espinosa Miñoso, Yunderkys, Diana Gómez Correal, and Karina Ochoa Muñoz (eds.) (2014) Tejiendo de otro modo: Feminismo, epistemología y apuestas descoloniales en Abya Yala, Popayán: Editorial Universidad del Cauca.

- Fals-Borda, Orlando (2002) Historia Doble de la Costa (2nd ed.), Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Banco de la República, Áncora Editores.

- Faxon, Hilary, Roisin Furlong, and May Sabe Phyu (2015) ‘Reinvigorating resilience: Violence against women, land rights, and the women’s peace movement in Myanmar’, Gender & Development 23(3): 463–479. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552074.2015.1095559.

- Forsberg, Erika and Louise Olsson (2021) ‘Examining gender inequality and armed conflict at the subnational level’, Journal of Global Security Studies 6: 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1093/jogss/ogaa023.

- Gizelis, Theodora (2011) ‘A country of their own: Women and peacebuilding’, Conflict Management and Peace Science 28(5): 522–542. https://doi.org/10.1177/0738894211418412.

- Gizelis, Theodora (2018) ‘Systematic study of gender, conflict, and peace’, Peace Economics, Peace Science and Public Policy 24(4): 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1515/peps-2018-0038.

- Gizelis, Theodora (2021) ‘It takes a village: UN peace operations and social networks in postconflict environments’, Politics & Gender 17(1): 167–196. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X18000855.

- Gómez Correal, Diana. (Forthcoming) ‘La materialidad vital de los ausentes-presentes en los movimientos de víctimas en Colombia’, in Herrera y Ordóñez (ed.) Museos para la paz, Bogotá: Universidad de los Andes.

- Gómez Correal, Diana, Angélica Arias, Mónica Durán, Auris Murillo, Angélica Bernal, Diana Montealegre, Marina López, and Yusmidia Solano (2020) Las mujeres y la construcción de paz: recomendaciones para la Comisión de Esclarecimiento de la Verdad en el proceso de inclusión de la perspectiva de género en el Caribe colombiano, Bogotá: Universidad de los Andes.

- Gómez Correal, Diana, Angélica Bernal, Juliana González, Diana Montealegre, and María Manjarrés (eds.) (2021) Comisiones de la verdad y género en países del sur global: Miradas decoloniales, retrospectivas y prospectivas de la justicia transicional. Aprendizajes para el caso colombiano, Bogotá: Universidad de los Andes, Insitituto CAPAZ.

- Gómez Correal, Diana and Diana Montealegre (2021) ‘‘Colombian women’s and feminist movements in the peace negotiation process in Havana: complexities of the struggle for peace in transitional contexts’’, Social Identities 27(4): 445–460. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504630.2021.1924659.

- Guglielmucci, Ana (2018) ‘Pensar y actuar en red: los lugares de memoria en Colombia’, Aletheia 8(16): 1–31.

- Guzmán Arroyo, Adriana (2019) Descolonizar Los Feminismos Feminismo Comunitario Antipatriarcal, La Paz: Tarpuna Muya.

- Haraway, Donna. (1995) Ciencia, cyborgs y mujeres. La reinvención de la naturaleza, Madrid: Cátedra.

- Harding, Sandra. (1996) Ciencia y feminismo, Madrid: Morata.

- Hernández Reyes, Castriela (2019) ‘‘Black women’s struggles against extractivism, land dispossession, and marginalization in Colombia’, Latin American Perspectives 46(2): 217–234. https://doi.org/10.1177/0094582X19828758.

- Hudson, Heidi (2016) ‘Decolonising gender and peacebuilding: feminist frontiers and border thinking in Africa’, Peacebuilding 4(2): 194–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/21647259.2016.1192242.

- Ibarra Melo, María Eugenia (2007) ‘Acciones colectivas de las mujeres en contra de la guerra y por la paz en Colombia’, Revista Sociedad y Economía, 13: 66–86.

- Jaime-Salas, Julio, Diana Gómez Correal, Karlos Pérez de Armiño, Sandra Londoño, Fabio Castro Herrera, and Jefferson Jaramillo Marín (eds.) (2020) Paz decolonial, paces insubordinadas. Conceptos, temporalidades y epistemologías, Bogotá: Universidad Javeriana.

- Jelin, Elizabeth (2002) Los trabajos de la memoria, Madrid: Siglo XXI.

- Justino, Patricia, Rebecca Mitchell, and Catherine Müller (2018) ‘Women and peace building: Local perspectives on opportunities and barriers’, Development and Change 49(4): 911–929. https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12391.

- Kirk, Jackie (2004) ‘Promoting a gender-just peace: The roles of women teachers in peacebuilding and reconstruction’, Gender & Development 12(3): 50–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552070412331332310.

- Krause, Jana and Louise Olsson (2020) ‘Women’ s Participation in Peace Processes, in Contemporary Peacemaking: Conflict, Violence and Peace Processes, Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Krause, Jana, Werner Krause, and Piia Bränfors (2018) ‘Women’ s participation in peace negotiations and the durability of peace’, International Interactions 44(6): 985–1016. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050629.2018.1492386.

- Kreft, Anne-Kathrin (2020) ‘Civil society perspectives on sexual violence in conflict: Patriarchy and war strategy in Colombia’, International Affairs 96(2): 457–478. https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiz257.

- Lamus Canavate, Doris (2010) De la subversión a la inclusión: Movimientos de mujeres de la segunda ola en Colombia, 1975-2005, Bogotá: Instituto Colombiano de Antropología e Historia ICAHN.

- Lander, Edgardo (ed.) (2000) La colonialidad del saber: eurocentrismo y ciencias sociales: perspectivas latinoamericanas, Buenos Aires: CLACSO.

- Lugones, María (2010) ‘Toward a decolonial feminism’, Hypatia 25(4): 742–759. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1527-2001.2010.01137.x.

- McLeod, Laura and Maria O’Reilly (2019) ‘Critical peace and conflict studies: feminist interventions’, Peacebuilding 7(2): 127–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/21647259.2019.1588457.

- Melander, Erik (2005) ‘Gender equality and intrastate armed conflict’, International Studies Quarterly 49(4): 695–714. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2478.2005.00384.x.

- Montealegre, Diana (2023) ‘Feminismos, resistencias y transiciones: posturas políticas de las luchas feministas por la Paz 2012-2021’. [PhD Thesis. Bogotá: Universidad de los Andes].

- Moreno Sierra, Denise, and Marcos de León Jaramillo (2020) ‘Historia de la tenencia de la tierra en los Montes de María y el papel de las mujeres’, Revista Cultural Unilibre 1: 89–108. https://doi.org/10.18041/1909-2288/revista_cultural.1.2019.6525.

- Obando, Diana, Mery Yolanda Sánchez, Alejandra Jaramillo Morales, Carolina López Jiménez, Leonardo Gil Gómez, and Óscar Campo (2021) Vidas de Historia. Una memoria literaria de la OFP, Barrancabermeja: Organización Femenina Popular.

- Paarlberg-Kvam, Kate (2021) ‘Open-pit peace: The power of extractive industries in post-conflict transitions’, Peacebuilding 9(3): 289–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/21647259.2021.1897218.

- Paris, Roland (2004) At War’s end: Building Peace After Civil Conflict, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Presidencia de Colombia (2018) Plan de Acción para la Transformación. Subregión de Montes de María, Bogotá: Presidencia de la República.

- Quijano, Aníbal (2000) ‘Coloniality of power, eurocentrism, and Latin America’, Nepantla: Views from South 1(3): 533–580.

- Red de Sitios de Memoria Latinoamericanos y Caribeños RESLAC (s/f) ‘Red Colombiana de Lugares de Memoria.’ https://sitiosdememoria.org/es/institucion/red-colombiana-de-lugares-de-memoria (accessed 10 August 2023)

- Richmond, Oliver. (2010) ‘A genealogy of peace and conflict theory’, in O. Richmond (ed.) Palgrave Advances in Peacebuilding, London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 14–38. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230282681_2.

- Richmond, Oliver (2011) ‘Resistencia y paz postliberal’, Relaciones Internacionales 16: 13–45.

- Rinaldi, Parisa (2023) Water science and democracy in Colombia's extractive frontiers. [PhD Thesis. Bogotá: Universidad de los Andes].

- Rivera Cusicanqui, Silvia (2010) Ch’ixinakax utxiwa: Una reflexión sobre prácticas y discursos descolonizadores, Buenos Aires: Retazos, Tinta Limón Ediciones.

- Ruiz Trejo, Marisa (2020) Descolonizar y despatriarcalizar las ciencias sociales, la memoria y la vida en Chiapas, Centroamérica y el Caribe, Chiapas: Universidad Autónoma de Chiapas.

- Skjelsbæk, Inger (2001) ‘Sexual violence and war: mapping out a complex relationship’, European Journal of International Relations 7(2): 211–237. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066101007002003.

- Velez, Emma and Nancy Tuana (2020) ‘Toward decolonial feminisms: tracing the lineages of decolonial thinking through Latin American/latinx feminist philosophy’, Hypatia 35(3): 366–372. https://doi.org/10.1017/hyp.2020.26.

- Yin, Robert (2004) Case study research. Design and methods (5th ed.), London: SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.1300/J145v03n03_07