ABSTRACT

Decolonising museums has become a popular issue in recent years as many museums have recognised the need to address how they have historically perpetuated colonialism and exclusion. One way in which museums can work towards gender diversity and inclusion is by actively seeking and amplifying the voices and perspectives of women and under-represented groups. This can be done through exhibitions, programming, and hiring practices that prioritise diverse perspectives and experiences. An important aspect of decolonising museums is re-evaluating how artefacts and collections are presented and interpreted. Museums have often reinforced patriarchal and colonial narratives in the past, and it is important to work actively towards a more inclusive and equitable representation of history. This can include re-contextualising artefacts to highlight the perspectives and contributions of marginalised groups, as well as actively seeking and acquiring artefacts that represent a more diverse range of perspectives. This paper will examine examples of museums that have successfully started decolonising their spaces through exhibitions on matriarchal societies and/or the representation of women in the Ancient World, with a focus on the American University of Beirut Archaeological Museum.

La question de la décolonisation des musées est devenue populaire ces dernières années, car de nombreux musées ont reconnu la nécessité de se pencher sur la façon dont ils ont perpétué le colonialisme et l'exclusion au fil de l'histoire. L'une des façons dont les musées peuvent œuvrer en faveur de la diversité et de l'inclusion des genres consiste à rechercher activement et à amplifier les voix et les points de vue des femmes et des groupes sous-représentés. Un aspect important de la décolonisation des musées consiste à réévaluer la manière dont les artéfacts et les collections sont présentés et interprétés. Les musées ont souvent renforcé les récits patriarcaux et coloniaux dans le passé, et il est important de travailler activement à une représentation plus inclusive et équitable de l'histoire. Il peut s'agir de recontextualiser les artéfacts pour mettre en évidence les points de vue et les contributions des groupes marginalisés, ainsi que de rechercher activement et d'acquérir des artéfacts qui représentent une gamme plus diverse de points de vue. Cet article examine des exemples de musées qui ont réussi à entamer la décolonisation de leurs espaces en organisant des expositions sur des sociétés matriarcales et/ou la représentation des femmes dans le monde antique, notamment le musée archéologique de l'Université américaine de Beyrouth.

En años recientes la descolonización de los museos se ha convertido en un tema popular, ya que muchos museos reconocen la necesidad de replantearse la forma en que históricamente han perpetuado el colonialismo y la exclusión. Uno de los modos en que los museos pueden impulsar la diversidad de género y la inclusión es la búsqueda y amplificación activa de las voces y perspectivas de las mujeres y los grupos subrepresentados. Esto puede hacerse mediante exposiciones, programación y prácticas de contratación que prioricen perspectivas y experiencias diversas. Un aspecto importante de la descolonización de los museos se asienta en la reevaluación de la manera en que se presentan e interpretan objetos y colecciones. Dado que en el pasado los museos a menudo reforzaron las narrativas patriarcales y coloniales, es importante dar pasos activamente hacia la concreción de una representación más incluyente y equitativa de la historia, por ejemplo, mediante la recontextualización de artefactos, para destacar las perspectivas y contribuciones de grupos marginados, y la búsqueda y adquisición activa de artefactos que den cuenta de una gama más diversa de perspectivas. Este trabajo examinará ejemplos de museos que ya empezaron a descolonizar con éxito sus espacios, presentando exposiciones sobre sociedades matriarcales y/o la representación de la mujer en el Mundo Antiguo, centrándose para ello en el Museo Arqueológico de la Universidad Americana de Beirut.

Introduction

Scholarly discourse has long been engaged in critical deliberations concerning knowledge, power, and cultural representation, as evidenced by the works of influential scholars such as Foucault (Citation1980) and Said (Citation1979). These discussions revolve around the examination of knowledge generation, dissemination, and their influence on power dynamics within societies, as explored by Chakrabarty (Citation2000) and Mignolo (Citation2000). They are particularly salient in colonial and postcolonial contexts, where dominant cultures historically exerted control over the production and dissemination of knowledge. Nevertheless, some scholars and museums have yet to address effectively the issue of decolonising knowledge and practice, and instead either enable the continuation of colonial representations or, at best, engage in tokenistic gestures. Others who actively pursue decolonisation initiatives face considerable political opposition when their work challenges prevailing and persisting colonial ideologies and practices even in postcolonial times. Often, resistance from political leaders stems from a desire to preserve existing power structures although rooted in colonialist and imperialist ways, as decolonisation threatens their authority, practices, discourses, and control. In the context of Mesopotamian material culture, the focus has shifted towards recognising the utilisation of the pre-Islamic past in Iraq by the Baathist regime for propagandist purposes. This engagement with the past allowed the regime to construct and promote a specific national identity rooted in historical continuity (Bahrani Citation2002). By emphasising the ancient glories of Mesopotamia, the Baathist government aimed to legitimise its own rule and bolster its authority by associating itself with a prestigious historical lineage. This has been observed all over the Near East with the rise of centralising and authoritarian regimes in the 1950s and 1960s (Migliorino Citation2006). Consequently, non-dominant cultures, such as the Armenian people, have constantly been marginalised, their existence and identities erased, and harmful stereotypes and cultural biases perpetuated (hooks Citation1992).

Even contemporary debates about cultural representation and knowledge production have centred on issues such as cultural appropriation, the politics of representation in the media, and the role of social media in shaping cultural narratives (Burwell Citation2010; Johnson Citation2018; Papacharissi Citation2010). In this context, it is important to consider how different forms of knowledge, including Indigenous and traditional knowledge, are represented and valued in contemporary society. By recognising and valuing diverse perceptions, one can begin to challenge the factors that have historically shaped knowledge production and dissemination, and create more equitable and inclusive societies (Smith Citation2012). If anything, these debates only assert the complexity of the relationship between cultural representation, power, and knowledge production, validating that it requires continuous inter-disciplinary and critical engagement.

In light of the ongoing debates about cultural representation and knowledge production, it is worth examining the role that museums have played in shaping these narratives and the extent to which they have contributed to issues such as cultural appropriation and the misrepresentation of non-dominant cultures (Burwell Citation2010; Johnson Citation2018; Smith Citation2012). The history of museums is indeed intertwined with the stories of power, knowledge, and misrepresentations since these institutions have collected, preserved, and displayed objects of cultural, historical, and scientific significance, giving them the power to shape the narratives surrounding those objects and the cultures they represent.

This paper delves into the essential task of decolonising museums, focusing specifically on gender equity and representation. It emphasises the transformative role of diverse leadership within museum institutions, despite the heavy colonial legacy they have inherited. It highlights the significance of fostering community collaboration to ensure inclusive narratives and meaningful engagement with diverse communities. It explores the delicate balance between repatriation and co-curation, acknowledging the importance of returning cultural artefacts to their rightful communities while also involving them in the curatorial process. In addition to emphasising the transformative role of diverse leadership within museum institutions, it underscores the crucial role of enhancing visitor education and engagement. This is particularly important within university museums in order to create more inclusive and accessible spaces and to challenge existing power structures. By addressing gender equity and representation in museums through these multifaceted approaches, this paper contributes to the broader decolonisation process, promoting equity, social justice, and inclusivity within the museum sphere.

Tracing the decolonisation of museums

In recent years, many museums in the North, as well as globally, have recognised their problematic colonial past and have taken steps to decolonise their collections and practices (Peers and Brown Citation2003). As the imperative to decolonise museums gains momentum, efforts to shift towards regional and local histories and challenging dominant national narratives (Sauvage Citation2010) have emerged alongside the acknowledgement of tokenism as a strategy employed by certain museums to address the issue of decolonisation. However, it is crucial not to overshadow the transformation of other museums into inclusive and diverse cultural and educational centres.

Therefore, decolonising museums remains an emerging, complex, and essential process. It involves acknowledging and addressing how museums have perpetuated colonial narratives and power structures. This transformative endeavour does not seek to dismantle museums, but instead encourages an awareness of their historical and cultural context. It also calls for questioning the status quo (Prianti and Suyadnya Citation2022) and prompting a re-evaluation of their societal function (Giblin, Ramos, and Grout Citation2019; Minott Citation2019).

In the following section, we will examine the methods and approaches that museum professionals have employed to decolonise museums successfully. Drawing from personal observations in the museum field, and comparing notes and perceptions between curators from different periods, including the 19th century, 20th century, and the significant advancements made by 21st-century curators, diverse strategies for decolonisation are explored. These methods encompass various aspects of museum practices, from collection development, exhibition design and interpretation, to audience engagement.

Diverse leadership representation

To decolonise museums effectively and promote inclusivity, it is crucial to address the role of gender in enhancing diversity within museum leadership. Active participation of women and individuals of all genders in leadership positions plays a vital role in this endeavour. By acknowledging the significance of gender diversity, museums can ensure the integration of a wider range of perspectives and experiences in exhibit curation and museum programming. One strategy to achieve this goal is the intentional recruitment of Indigenous and other marginalised individuals for curatorial, directorial, and staff roles, so as to foster representation and provide opportunities to historically under-represented groups. However, equal access to professional development and advancement is essential to enable these individuals to contribute effectively to the museum sector.

The increasing prominence of women in the museum field globally has garnered attention. Women curators have been instrumental in diversifying and broadening the scope of museum collections, adding diverse perspectives and expertise, and enriching the museum landscape. Lebanon’s museums provide an interesting case study in this regard, with women comprising a significant presence, accounting for approximately 89 per cent of the workforce.Footnote1 What makes this even more noteworthy is the emergence of women as predominant decision-makers and leaders in museum management and curation. Lebanese museums exhibit a pronounced dearth in staffing resources, thereby compelling museum professionals and personnel to undertake the roles of directors, managers, and curators concurrently. Lebanon’s context adds further significance to this phenomenon, as women’s rights in the country continue to face challenges. Women in Lebanon are granted less than 60 per cent of the rights enjoyed by men (Grandchamps Citation2023). Therefore, the increased representation and leadership of women in Lebanese museums take on added depth, demonstrating progress towards gender equality and empowerment within the cultural sector, despite prevailing societal obstacles. It showcases women’s resilience and determination to contribute significantly to cultural institutions, thus attempting to create social and political change. Despite limited gender equality in Lebanese society, they challenge prevailing gender norms and excel in leadership positions, serving as an inspiration for women in other industries and societies facing similar challenges.

Fostering community collaboration

Another critical aspect of decolonising museums is providing opportunities for community input and consultation in the curation of exhibits. This involves working closely with Indigenous communities and other marginalised groups to ensure that their perspectives and stories are accurately represented in museum displays. It can also involve engaging with community members in the development and planning of exhibits, enabling them to contribute their knowledge, expertise, and perspectives to the museum’s programming (Peers and Brown Citation2003). One notable example of community collaboration at the Pitt Rivers Museum, The University of Oxford, renowned for its ethnographic collections and showcasing archaeological and anthropological artefacts from around the world, is the ‘Identity Without Borders’ exhibition.Footnote2 This exhibition is a collaborative project co-curated by museum professionals and volunteers who are refugees or asylum seekers in Oxford. The exhibit is divided into two parts: Part One explains the project’s development, while Part Two showcases objects from the museum’s collections and items loaned by volunteers, reflecting their cultural heritage and expertise. The volunteers have written the labels for Part Two, providing unique and personal perspectives. The project empowers volunteers by giving them access to the collections, conduct research, and share their insights, contributing to a more inclusive and diverse exhibit.

Balancing repatriation and co-curation

Repatriation of artefacts and objects to their rightful communities is another critical component of decolonising museums. This involves returning items that were taken without proper consultation, consent, or compensation to the communities from which they were removed. However, it is paramount to note that repatriation should not become a general rule for museums, but remain a case-by-case study for each collection and object. While returning objects to their communities of origin can be a way to acknowledge past harm and possibly to open up dialogue for reparations, museums must also consider the ethical and legal implications of repatriation. An innovative approach to address this issue is for museums to partner with Indigenous communities to co-curate exhibitions and displays of cultural objects (Chipangura Citation2020). This can provide communities with greater control over the interpretation and presentation of their cultural heritage, and can help to ensure that objects are displayed in ways that are respectful and aligned with community values and practices.

The decision by the Smithsonian National Museum of African Art, in Washington, DC, to return the Benin bronzes to Nigeria stands as a significant illustration of repatriation within the museum domain. The Benin bronzes, renowned for their artistic and cultural significance, were originally looted during the punitive expedition by British forces in 1897. For decades, these artefacts have been housed in various Western museums, raising debates surrounding issues of cultural heritage, colonialism, and the ethical responsibility of institutions in possession of contested objects. The recent decision of repatriation exemplifies a notable shift in museum practices and attitudes towards restitution. Objects taken without consent were returned to their rightful community, as acknowledged by the museum. This case demonstrates the importance of considering the ethical and legal implications of repatriation. Although the National Museum of African Art is relatively small, it has been at the forefront of significant movements in the museum world (Stoilas Citation2023). Ngaire Blankenberg, the former director, was a catalyst for this return and played a leading role in the development of the Smithsonian’s new ethical returns policy. Her work and leadership were crucial to these accomplishments. A woman of South African descent herself, Blankenberg emphasises the importance of ‘addressing the wounds of the past to build a better future’. She also believes that it is ‘important to understand where resistance lies and how it manifests to bring about positive changes in museums’ (Stoilas Citation2023).

Enhancing visitor education and engagement and the role of university museums – a case study of AUB

In the context of decolonising museums, it is crucial to provide education and resources for visitors to better understand the historical and cultural context of the artefacts on display. This could entail the development of interpretive materials and educational programmes that not only provide information about the communities from which the artefacts were originally obtained, but also shed light on the communities in which they are currently displayed, as well as their journey in transit.

University museums possess a unique position in this transformative endeavour, as they not only contribute to scholarly reinterpretations of history, but also provide students with an intellectual space to explore diverse perspectives and engage in critical dialogue. To assume this responsibility, university museums can create educational materials, such as interpretive resources, which highlight the historical and cultural significance of the communities associated with the artefacts. Additionally, they can offer courses and resources that facilitate students’ deeper understanding of marginalised communities and their rich histories (Gokcigdem Citation2016; Weber Citation2022).

One such example of a university museum would be the Archaeological Museum at the American University of Beirut (AUB) in Lebanon, founded during the Ottoman EmpireFootnote3. The AUB, established in 1866 as the Syrian Protestant College, has a rich history of providing modern education in the Middle East based on American principles and values. While initially operating within a colonial framework, the university’s mission has evolved over time. The institution actively collaborates with American universities in the region, fostering academic partnerships and promoting research and cultural understanding. It also maintains strong ties with American counterparts in the USA, facilitating research, faculty exchange, and student mobility. Since it is a private institution, it is governed by a board of trustees.

Embracing the principles of the US–Middle East Partnership Initiative (MEPI), AUB has implemented programmes to advance gender equity and inclusivity. The university is committed to promoting women’s rights and opportunities, ensuring gender equality in education and employment, and fostering an inclusive environment for its diverse community. Through participation in MEPI’s Gender and Women’s Empowerment projects, AUB aims to empower women, strengthen democratic institutions in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, and contribute to equal rights and economic prosperity for women and their families.

The Archaeological Museum at AUB presents a particular case study that warrants careful examination of its historical circumstances. While acknowledging its imperial origins, it is imperative to recognise the involvement of local communities and individuals in shaping the collections and narratives of the institution. A comprehensive understanding of the museum necessitates a thorough exploration of its intricate connections with the neighbouring regional communities in Lebanon and beyond. This entails delving into the dynamics of cultural exchange, power dynamics, and agency within the context of Ottoman rule. It is vital to investigate the acquisition processes of the museum’s collections, the parties responsible for narrative control, and the representation or marginalisation of voices and perspectives from the local Lebanese communities.

As the Archaeological Museum continues to prioritise research and scholarly investigation into the provenance and provenience of its collections, the museum’s new leadership has taken additional steps towards enhancing its mission, one of which was to actively pursue collaborations with diverse faculty members and artists from both the AUB community and beyond. Through these collaborations, the museum’s curator hosts exhibitions that prominently showcase the creative endeavours of students, faculty, and alumni, offering a platform for innovative experimentation and exploration. These exhibitions also address themes related to social justice and equity, offering opportunities for engaging in critical dialogues and introspective contemplation. The museum’s leadership commitment to gender equity and inclusivity is evident in its various initiatives, which promote women’s empowerment.

Mohamad Kanaan,Footnote4 a lecturer in the Department of Architecture and Design at the AUB, exemplified a scholarly engagement with the museum’s collections. He accomplished this through the implementation of an elective course in Spring 2023, titled ‘Rewriting History: A Visual Exploration of the Museum of Archeology at AUB Through Counterfiction’. In this educational setting, Kanaan collaborated with students to craft counter-fictitious narratives that challenged prevailing accounts and perspectives. The utilisation of these alternative approaches contributes to the cultivation of more-inclusive and decolonised narratives, encompassing artwork, essays, and other creative outcomes. This endeavour aims at enhancing visitors’ comprehension of the contextual significance of the exhibited artefacts, while simultaneously promoting cultural understanding and respect. This could potentially serve as a catalyst for students’ profound engagement with the intricacies of the museum’s collections, and provide them with an opportunity to navigate the ethical considerations and challenges involved in presenting history and culture inclusively and ethically.

One fascinating installation at the Archaeological Museum is by student Nadine Noureddine, who poses a compelling counter-fiction question: ‘What if humans had a balanced relationship with nature, rather than exploiting it for growth and gain? How would the human body evolve, and how would practices like body modification change in a society that valued nature’s preservation?’ Noureddine recreated a 3D cast in which she melted plastic water bottle caps and reproduced an exact 3D print of the bone bead necklace attributed to the Natufian period (). This necklace, one of the earliest known in the region, dating back to approximately 10,000 BC, features breast-shaped beads made of bone and dentalium shell. In her installation, Noureddine also critiques the contemporary trend among women to resort to plastic surgery for breast modification, highlighting the use of plastic or silicone in these procedures. Noureddine denounces this practice, emphasising the potential negative impact of such procedures on both the environment (due to the use of plastic materials) and on societal perceptions of beauty. Her artistic work delves deeper into the cultural and societal pressures that promote and enforce unrealistic beauty standards, often perpetuated by the structures of patriarchy and racism. Women are disproportionately affected by these oppressive beauty standards that prioritise Eurocentric features, reinforcing notions of white beauty as the norm. Under the influence of these standards, many women may feel compelled to alter their bodies to conform to an unrealistic and unattainable ideal of beauty, further entrenching the harmful effects of patriarchy and racism. Her critique also extends to the impact of neoliberalism, which commodifies bodies and fosters a consumerist approach to beauty. Through her artistic work, Noureddine prompts reflection on alternative approaches to body modification that align with a balanced relationship with nature and promotes the preservation of natural resources. Her installation not only challenges the environmental consequences of plastic surgery, but also calls for a shift in societal perceptions of beauty, advocating for self-acceptance and embracing diverse body types and appearances.

Figure 1. Left panel: Epipaleolithic showcase at the AUB Museum (© Aimée Bou Rizk, AUB Archaeological Museum). Right panel: Noureddine’s counter-fiction of the Natufian period necklace (©Aimée Bou Rizk, AUB Archaeological Museum).

Amal Kardaly, another design student, featured a captivating counter-narrative through a series of coins: ‘What if the myth of Europa had depicted ancient Europeans mass immigrating to Phoenicia instead of the abduction of the Phoenician princess, altering the course of history and shaping the relationship between Phoenicia (modern-day Lebanon) and Europe in unforeseen ways?’

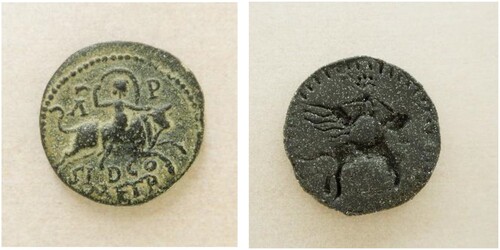

Her work reimagines the myth of Europa, offering a different perspective on the ancient tale. In the first coin of her series, Europa takes centre stage as she rides a horse, subverting the traditional portrayal of Zeus transformed into a white bull. What sets this depiction apart is the inclusion of a powerful symbol: Europa’s shoulders are adorned with a thermal blanket, symbolising the hardships and challenges faced by migrants during their journeys (). Through this reinterpretation, Kardaly prompts viewers to reconsider the stories we tell and the perspectives we privilege. She encourages us to reflect on the intertwined histories of migration, resilience, and cultural exchange, underscoring the transformative power of embracing diverse narratives and challenging established norms. The second coin of Kardaly’s series portrays a Phoenician trireme sailing across a sea of coins (), symbolically denouncing the influence of power, money, and financial biases. This powerful imagery draws attention to the role of wealth and economic interests in shaping historical narratives and societal dynamics. This alteration in the story’s trajectory has profound implications, reshaping the course of history and forging unforeseen connections between Phoenicia (present-day Lebanon) and Europe. In the third coin of her series (), a male figure, likely Cadmus, Europa’s brother, is portrayed wearing a life jacket, creating a juxtaposition between historical symbolism and contemporary safety measures. Through her artistic exploration, Kardaly prompts viewers to reconsider established narratives and envision alternative possibilities. Her reinterpretation of the myth of Europa invites contemplation on the complexities of historical events and the interconnectedness of cultures, challenging our understanding of the past and its impact on the present.

Figure 2. Left panel: Europa seated on bull; with the left hand she holds its horn, with the right, an inflated veil; AD 218–222; Sidon; Phoenicia (© Reine Mady, AUB Archaeological Museum). Right panel: Europa’s counter-narrative by Kardaly (© Rine Mady, AUB Archaeological Museum).

Figure 3. Left panel: Phoenician ship and Murex shell; circa 450 BC to 266 AD; Tyre; Phoenicia (© Reine Mady, AUB Archaeological Museum). Right panel: Phoenician ship counter-narrative by Kardaly (© Reine Mady, AUB Archaeological Museum).

Figure 4. Left panel: Cadmus wearing cloak fastened round neck, running on prow; he looks back, points forward with extended right arm; border of dots; AD 116–117; Sidon; Phoenicia (© Reine Mady, AUB Archaeological Museum). Right panel: Cadmus’ counter-narrative by Kardaly (© Reine Mady, AUB Archaeological Museum).

Gender equity and representation in museums – highlighting AUB’s efforts

Gender equity and representation in museums occupy a critical position within the comprehensive decolonisation process, aiming to foster equity and social justice. Consequently, it warrants an individual examination to delve into this specific dimension.

In recent years, the need to address gender equity and representation within museums has been increasingly recognised on a global scale. Several endeavours have been undertaken to rectify the pervasive under-representation of women in these institutions. The International Council of Museums (ICOM) has responded to this concern by formulating guidelines pertaining to gender equity and diversity in museums, providing a comprehensive framework for institutions to address these pressing issues (ICOM Citation2016).

The under-representation of women in museums transcends specific regions or cultures; rather, it signifies a systemic predicament affecting all institutions, albeit differently with regards to each of their own contexts. Addressing this concern has necessitated multifaceted measures, including exhibitions and programmes that specifically underscore women’s contributions to art, culture, and history. Many institutions worldwide – such as The British Museum, The Nanjing Museum, and The Oriental Institute of Chicago’s Museum – are actively taking measures to ensure that their collections and interpretive materials encompass a broader and more-inclusive spectrum of voices and perspectives. They have taken steps to integrate women’s perspectives and, sometimes, matriarchal societies into their publications, collections, and exhibitions.

To gain a deeper understanding of these initiatives and assess their impact, we will focus and explore examples from the AUB Archaeological Museum, where the recently appointed curator and author of these lines has implemented such changes.

‘Mother Earth’

One notable collaborative celebration is between the AUB Archaeological Museum, AUB Libraries, the Asfari Institute for Civil Society and Citizenship, the Issam Fares Institute for Public Policy, the Office of Communications, and the AUB MEPI programme. Since 2022, these entities have come together to commemorate International Women’s Day at the museum and at the AUB Library, dedicating an entire month to honour and highlight the achievements of women. This annual celebration serves as a platform to recognise the contributions of women in art, archaeology, science, academia, and society at large. Through exhibitions, lectures, workshops, and other engaging activities, the consortium strives to inspire and empower women, fostering a deeper understanding and appreciation of their significant roles.

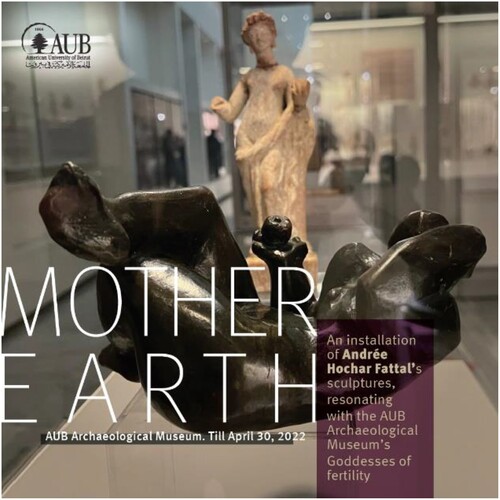

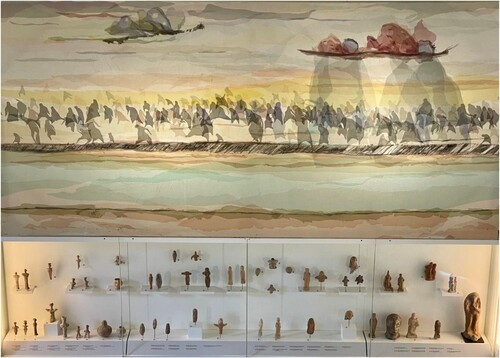

In line with this commitment, the exhibition titled ‘Mother Earth’ () by artist Andrée Hochar Fattal, that ran between March and May 2021, aimed to challenge traditional narratives about ancient societies that have historically excluded or downplayed the roles of women. The museum’s curator reimagined and reinterpreted the artists’ works by placing contemporary art sculptures in conversation with ancient artefacts, showcasing the innovative ways in which modern artists approach and reinterpret the symbols and forms present in ancient art. The installation incorporates contemporary works of art alongside archaeological fertility figurines, establishing a visual and thematic dialogue that is staged by the curator’s texts offering a new narrative on women throughout the ages.

Each installation represents a distinct idea, and was curated with an explicit text referring to a specific historical period; however, only four examples will be addressed here.

The first installation, Ma Pomme (My Apple), showcases a piece that challenges the mythological narrative surrounding a famous Greek pantheon’s banquet (). The installation features a bronze sculpture, titled Ma Pomme, engaging in conversation with a Tanagra figurine of Aphrodite holding an apple, dating back to the Hellenistic period (between the third and the first century BC). The myth of Aphrodite and the golden apple unfolds during a wedding banquet for Thetis and Peleus. Eris, the Goddess of strife, feeling excluded from the celebration, disrupts the event by throwing a golden apple inscribed with the word kallistēi, meaning to the fairest. Chaos ensues as Athena, Hera, and Aphrodite vie for such title. Ultimately, Zeus appoints a human, Paris, to decide, and Aphrodite wins by promising him the hand of the world’s most beautiful woman, Helen of Sparta. This leads to Paris and Helen eloping to Troy, igniting the 10-year Trojan War. The installation presents a thought-provoking conversation between a confident and nonchalant woman reclining on a couch, holding an apple, and the representation of Aphrodite also holding an apple. Through this counter-narrative, the installation challenges the longstanding portrayal of women, dating back to ancient Greek civilisation, held responsible for chaos, wars, and the disruption of societal order. This discourse has been inherited by monotheistic religions, notably seen in the book of Genesis, where Eve is depicted as the original woman responsible for tempting Adam with the forbidden fruit, often symbolised as an apple, leading to their expulsion from the Garden of Eden.

The second installation, Méditerranée, in conversation with the prehistoric female figurines (), contextualises the fertility figurines, within the Gynocratic AgeFootnote5 when women held revered positions, simultaneously exploring the narrative of a pre-patriarchal matriarchal society. It also challenges Cynthia Eller’s critique, advanced in her book The Myth of Matriarchal Prehistory (Eller Citation2000), which contests the notion that a matriarchal history automatically ensures gender equality and a more promising future for women. Eller encourages a more nuanced understanding of gender dynamics throughout history and highlights the importance of evidence-based analysis in shaping feminist perspectives. She argues that fixating on an idealised and fictitious past detracts from acknowledging the actual struggles and advancements of women in the present, and efforts should be focused on addressing the tangible challenges confronted by women in contemporary society.

The third installation, Déesse (Goddess) (), pays homage to the Mesopotamian Bronze Age female fertility figurines. The curator’s cartel reads:

The artist’s brain functions as a palimpsest, assimilating and imbuing all the images, emotions, and encounters, both observed and unobserved for millennia, translating them into art. Subconsciously, yet effortlessly, the artist shapes her fertility Goddess with a face reminiscent of a bird, employing the very technique that has been employed since the early Bronze Age. (FREE-HAND MODELING IN THE BRONZE AGE and the THE SNOW(O)MAN TECHNIQUE, in which the main features are pinched from a clay lump (8th mill. BC).

Thalassa (Goddess of the Sea) () is the fourth installation and converses with a central showcase featuring over 3,000 years of evolving figurines. The artistic process involves the use of various sculpting techniques, reflecting different periods in history. From free-hand modelling in the Bronze Age to the moulded technique prevalent from the late Bronze to the Roman period, the evolution of figurine art is traced. Changes in style, such as the transition from nude figures to draped dresses and the influence of Greek costumes, are also explored.

The curator’s installations provide an immersive and thought-provoking encounter, prompting viewers to reflect upon the interwoven lives of women through the ages. The overarching aim is to cultivate a holistic understanding of the world as a complex and interconnected entity, transcending our prior notions. It does not aspire to present a comprehensive narrative of the history of women. Rather, it beckons us to embark on a personal exploration of our own past, perhaps even our individual stories, and certainly of the ever-present world that continually shapes our existence. The exhibition not only showcased the interconnections between ancient matriarchal societies and modern feminist art, but also challenged conventional patriarchal narratives, shining a light on the pivotal role of women in shaping history.

‘The caregiver’

Another collaborative work within the aforementioned elective course, ‘Rewriting History: A Visual Exploration of the Museum of Archaeology at AUB Through Counterfiction’, designed by Mohamad Kanaan, has yielded a significant outcome in the form of a permanent installation housed in the central showcase featuring over 3,000 years of evolving figurines. This thought-provoking installation, created by student Carmen Chahal, presents a reinterpretation of the fertility figurine by featuring a genderless double figurine (). With a deliberate focus on a genderless representation, the installation prompts a profound question: ‘What if the caregiver–child relationship transcended traditional gender roles?’ By placing emphasis on gender diversity in child care, the artwork challenges societal norms and conventional narratives that have historically confined women to specific roles, while marginalising or undervaluing their contributions. The installation further questions the traditional family structure within societies, advocating for a reimagining of gender roles and fostering a more-inclusive understanding of caregiving responsibilities. Through the active exploration and presentation of diverse perspectives and experiences, museums can evolve into inclusive and equitable spaces that reflect the breadth and depth of the human experience.

Figure 9. Left panel: Showcase featuring over 3,000 years of evolving figurines (© Nadine Panayot, AUB Archaeological Museum). Right panel: Carmen Chahal (genderless fertility figure): ‘What if the caregiver–child relationship went beyond traditional gender roles?’ (© Nadine Panayot, AUB Archaeological Museum).

‘From Oppression to Liberation: The Journey of Women in an Aching Near East’

In the exhibition titled ‘From Oppression to Liberation: The Journey of Women in an Aching Near East’, held at the AUB Archaeological Museum from 8 March to 2 May 2023, the AUB Museum curator showcased the paintings, etchings, and engravings of Syrian artist Azza Abo Rebieh. Abo Rebieh’s work offers a profound insight into the complexities of her artistic vision, shaped by her personal experiences as an activist, her experiences of imprisonment in her home country, working with imprisoned women, followed by her exile in Lebanon. Her initial etchings vividly captured the diverse manifestations of oppression, serving as a testament to the enduring presence of repressive forces that have cast a shadow over the region throughout history. Among Abo Rebieh’s artworks, a notable portrayal is that of a woman screaming with outstretched arms (), resonating with a Roman period figurine of a woman’s arms, stretched though broken (in the circle), symbolising rebellion and the indomitable power of people’s voices that cannot be subdued, even in the face of military coercion.

Figure 10. Azza Abo Rebieh’s own cartel and words: ‘When I see a flying butterfly, I am struck not only by its beauty, but also by something within me. Flying alongside her, as if her presence will lift me from my heavy world and into the open air, to that world … to nothingness’ (© Nadine Panayot, AUB Archaeological Museum).

Abo Rebieh’s artistic journey not only encapsulates but also honours the shared experiences of numerous women in the region, who continue to navigate their own struggles and apprehensions. Her life and personal journey epitomise the fear of powerful women that permeates the region, while simultaneously celebrating the resilience of women who tirelessly fight for human rights, confront injustice, and refuse to surrender. Finding solace within the embrace of women’s solidarity, Abo Rebieh embarks on a journey of self-repair and self-love, grasping on to a thread that guides her. Her paintings challenge the notion that women are confined to subordinate positions in society, emphasising the potential for women’s empowerment and leadership. Through her own transformation, she becomes a catalyst for change, impacting not only her own body but also transcending the boundaries of gender and body. With unwavering determination, she confronts the present, embraces life, and recognises her interconnectedness with the world ().

Figure 11. Azza Abo Rebieh’s own cartel and words: ‘We are dreamy lovers, waiting, but not madly! I will not draw the borders of my country, that word is the fatal bullet: homeland or country. I am a human being or an animal or a butterfly, I do not belong, but I fly’ (© Nadine Panayot, AUB Archaeological Museum).

Conclusion

Museums all over the world have implemented multifaceted measures, including exhibitions and programmes that specifically underscore women’s contributions to art, culture, and history. The integration of women’s perspectives and the exploration of matriarchal societies in publications, collections, and exhibitions worldwide demonstrate a growing recognition of the need to diversify and inclusively represent voices and experiences.

The exhibitions discussed in this analysis collectively exemplify the ongoing efforts to address gender equity and representation in museums. They serve as powerful tools within the comprehensive decolonisation process, seeking to foster enhanced equity and social justice. By challenging traditional gender norms, highlighting the contributions of women, and exploring diverse perspectives, they contribute to a more thorough understanding of the complexities of femininity and its representations, as well as the historical contributions of women.

Through a closer examination of specific exhibitions at the AUB Archaeological Museum, we witness the ongoing efforts of their respective goals in challenging dominant narratives, humanising women in history, and empowering marginalised voices. They invite viewers to engage critically with the portrayal of women, question prevailing norms, and re-evaluate the contributions and experiences of women throughout history. By showcasing the multifaceted roles of women, their resilience, leadership, and the struggles they have faced, these exhibitions prompt reflection on the intersections of gender, power, and identity. Moreover, these exhibitions serve as catalysts for broader social change. They inspire audiences to examine their own preconceived notions, challenge societal structures that perpetuate gender inequality, and acknowledge the interconnectedness of women’s experiences across time and cultures. They remind us that women’s stories, voices, and experiences are integral to our understanding of humanity, and should be recognised, celebrated, and raised, and serve as a call to action for continued progress towards gender equality, representation, and empowerment in all aspects of life. By embracing these innovative and inclusive narratives, we pave the way for a more-inclusive future where women’s voices are heard, valued, and amplified.

Acknowledgements

I extend my deepest gratitude to every artist, student, and professor mentioned in this article, who has graciously collaborated with me on these initiatives and granted me approval to mention their achievements in this paper.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Nadine Panayot

Nadine Panayot holds a Doctorate in Classical Mediterranean Archaeology from Paris 1 La Sorbonne. She serves as the Curator of the American University of Beirut’s Archaeological Museum and an Associate Professor of Practice at the Department of History and Archaeology. Following the port of Beirut explosion in 2020, she successfully restored the museum’s collection of archaeological glass in collaboration with international teams, aiming to heal her Lebanese colleagues and raise awareness of corruption and atrocities. Previously, Nadine was the Director of the University of Balamand’s Archaeology and Museology Research Department, and the founder and Chairperson of the Master’s Program in Museum Studies and Cultural Heritage Management. She also co-founded and curated the Ethnographic Museum at UOB. With involvement in Near East archaeological excavations since 1992, she advocates for a holistic approach to natural and cultural heritage conservation, emphasising their link to human dignity and well-being. She has recently been honoured with the prestigious insignia of Knight of Arts and Letters by the French Government in recognition of her significant contributions and commitment to the arts, heritage conservation and promotion. Postal address: Archaeological Museum, American University of Beirut, Bliss Street, Beirut, Lebanon, P. O. Box 11-0236. Email:[email protected]

Notes

1 Based on membership numbers and records of the International Council of Museums’ yearly subscriptions.

3 AUB Archaeological Museum links: https://www.facebook.com/AUBArchaeologicalMuseum; https://www.instagram.com/aubarchaeologicalmuseum/; https://www.aub.edu.lb/museum_archeo/Pages/default.aspx.

4 Authorisation was obtained from faculty members and students to include their works in this article.

5 The term Gynocratic Age refers to a hypothetical period or concept characterised by female or feminine dominance in social, political, and cultural realms. It is derived from the Greek words gyne (woman) and kratos (rule or power). The idea of a Gynocratic Age often contrasts with the more commonly known patriarchal societies that have historically prevailed in many parts of the world. It is important to note that the concept of a Gynocratic Age is largely speculative and has not been widely recognised or supported by mainstream historical or anthropological research. It is often used as a theoretical construct to challenge traditional gender roles and power dynamics, highlighting the potential for alternative social structures that promote gender equality.

References

- Bahrani, Zainab (2002) ‘Conjuring Mesopotamia: Imaginative geography and a world past’, in Lynn Meskell (ed.) Archaeology Under Fire. Nationalism, Politics and Heritage in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East, London: Taylor & Francis e-Library, 159–174.

- Burwell, Catherine (2010) ‘Rewriting the script: Toward a politics of young people’s digital media participation’, Review of Education, Pedagogy, and Cultural Studies 32(4–5): 382–402.

- Chakrabarty, Dipesh (2000) Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Chipangura, Njabulo (2020) ‘Co-curation and new museology in reorganizing the Beit gallery at the Mutare museum, eastern Zimbabwe’, Curator: The Museum Journal 63(3): 431–446.

- Eller, Cynthia (2000) The Myth of Matriarchal Prehistory: Why an Invented Past Won’t Give Women a Future, Boston: Beacon Press.

- Foucault, Michel (1980) Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972–1977, New York: Pantheon Books.

- Giblin, John, Imma Ramos and Nikki Grout (2019) ‘Dismantling the master’s house’, Third Text 33(4–5): 471–486.

- Gokcigdem, Elif M (ed.) (2016) Fostering Empathy Through Museums, Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Grandchamps, Claire (2023) ‘Au Liban, la femme bénéficie de moins de 60% des droits octroyés aux hommes’. L’Orient le Jour. March 8. https://www.lorientlejour.com/article/1159468/egalite-hommes-femmes-au-liban-des-avancees-mais-beaucoup-reste-a-faire.html.

- hooks, bell (1992) Black Looks: Race and Representation, Boston: South End Press.

- Johnson, Jessica Marie (2018) ‘Social stories: Digital storytelling and social media’, Forum Journal 32(1): 39–46.

- ICOM (2016) https://icom.museum/en/news/gender-mainstreaming-icoms-mission-in-the-past-three-decades/.

- Migliorino, Nicola (2006) ‘‘Kulna suriyyin’? The Armenian community and the state in contemporary Syria1’, Revue des Mondes Musulmans et de la Méditerranée Méditerranée 115-116: 97-115.

- Mignolo, Walter D. (2000) Local Histories/Global Designs: Coloniality, Subaltern Knowledges, and Border Thinking, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Minott, Rachael (2019) ‘The past is now’, Third Text 33(4–5): 559–574.

- Papacharissi, Zizi (2010) A Networked Self. Identity, Community, and Culture on Social Network Sites, New York and London: Routledge.

- Peers, Laura and Alison K. Brown (2003) Museums and Source Communities. A Routledge Reader, London and New York: Routledge.

- Prianti, Desi Dwi and I Wayan Suyadnya (2022) ‘Decolonising museum practice in a postcolonial nation: Museum’s visual order as the work of representation in constructing colonial Memory’, Open Cultural Studies 6(1): 228–242.

- Said, Edward W. (1979) Orientalism, New York: Vintage Books.

- Sauvage, Alexandra (2010) ‘To be or not to be colonial: Museums facing their exhibitions’, Revista Culturales 6(12): 97–116.

- Smith, Linda Tuhiwai (2012) Decolonising Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples, London: Zed Books.

- Stoilas, Helen (2023) ‘The smithsonian’s national museum of African Art is looking for a new director—again’, The Art Newspaper. May 9 https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2023/05/09/smithsonian-national-museum-african-art-ngaire-blankenberg-resigned.

- Weber, Katherine E. (2022) ‘The role of museums in educational pedagogy and community engagement’, College of Education Theses and Dissertations 254, 27–36.