ABSTRACT

Constructing academic knowledge in and from the global South is riddled with negotiations of oneself, our collectivities, and the demands of productivity. In our activism in and outside academia, gender knowledge emerges like grass: unpredictable, collective, abundant, messy. In policy and higher education, the field is limited by the credentials of expertise with all the restrictions, pressures, and limitations of higher education and its demands for publication. Gender studies is currently a contested field, facing attacks from across the political spectrum that question its rigour, ethics, and very nature. In this context, rooted in our concern for how we construct gender knowledge and the continued colonial consequences of academia, we reflect on our own negotiation processes and offer our methodologies of creativity and play as a way to evade the limits of expertise. Inspired by Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of rhizomes as well as MacLure’s call to wonder, we examine the intersections of our experiences and our positionalities in and with the academic spaces we inhabit, to discuss methodologies in knowledge construction. We look at how these methodologies allow us to map contradictions and tensions in the construction of knowledge between the arboreal forms of what is considered knowledge and the other that is possible, born from where we have been cut, the phantom members of the decolonial ghost.

La construction des connaissances universitaires au sein et à partir de l'hémisphère Sud est truffée de négociations sur soi, sur nos collectivités et sur les exigences de productivité. Dans le cadre de notre activisme à l'intérieur et à l'extérieur du monde universitaire, les connaissances sur le genre émergent comme l'herbe, de manière imprévisible, collective, abondante, désordonnée. En matière de politiques et d'enseignement supérieur, le domaine est limité par les titres de compétence et de savoir-faire, avec toutes les restrictions, pressions et limitations de l'enseignement supérieur et ses exigences en matière de publication. Les études de genre constituent actuellement un domaine contesté, faisant l'objet d'attaques de la part de l'ensemble de la sphère politique, qui remettent en question sa rigueur, son éthique et sa nature même . Dans ce contexte, sur la base de notre préoccupation concernant la façon dont nous construisons les connaissances sur le genre et les conséquences coloniales persistantes du monde universitaire , nous réfléchissons à nos propres processus de négociation et proposons nos méthodologies de créativité et de jeu comme moyen d'échapper aux limites du savoir-faire. Inspirés par le concept des rhizomes ainsi que par l'appel à l'émerveillement de McLure , nous examinons les intersections de nos expériences et de nos positionnements au sein des espaces universitaires que nous habitons et avec eux, afin de discuter des méthodologies en matière de construction des connaissances. Nous examinons comment ces méthodologies nous permettent de cartographier les contradictions et les tensions dans la construction des connaissances entre les formes arborescentes de ce qui est considéré comme la connaissance et d'autres formes possibles, nées des endroits où nous avons été coupés, membres fantômes du spectre décolonial.

La construcción del conocimiento académico en y desde el Sur global está plagada de negociaciones que realiza uno mismo, como también nuestras colectividades, así como de las exigencias de productividad. En nuestro activismo dentro y fuera del mundo académico, el conocimiento de género emerge como la hierba: impredecible, colectivo, abundante, desordenado. En la política pública y la educación superior, el campo está restringido por la exigencia de tener dominio de conocimientos y las innumerables limitaciones y presiones inherentes a la educación superior, como también por sus exigencias de publicación. Los estudios de género son actualmente un campo en disputa, que enfrenta ataques provenientes de todo el espectro político; éstos cuestionan su rigor, su ética y su propia naturaleza. En este contexto, arraigadas en la preocupación por cómo construimos el conocimiento de género y considerando las continuas consecuencias coloniales de la academia, reflexionamos sobre nuestros propios procesos de negociación y ofrecemos nuestras metodologías de creatividad y juego como forma de eludir los límites impuestos por la expertise. Inspirándonos en el concepto de rizomas y en la llamada al asombro de McLure, examinamos las intersecciones de nuestras experiencias y posicionalidades en y con los espacios académicos que habitamos, para discutir metodologías orientadas a la construcción del conocimiento. Así, analizamos cómo dichas metodologías nos permiten mapear las contradicciones y tensiones presentes en la construcción del conocimiento entre las formas arbóreas de lo que se considera conocimiento y el Otro que es posible, nacido de donde hemos sido moldeadas, las integrantes fantasmas de la aparición descolonial.

Introduction

This paper is a reflection on academic knowledge construction in gender studies and the colonial consequences of the methods we use in doing so. We write from a preoccupation with the colonial roots and implications of academic knowledge, in general, and the erasure of activist feminist knowledge, in particular. Using a decolonial feminist lens, we analyse our personal experiences and positionalities between academic Eurocentric knowledge and activist knowledge in relation to academia and our experiments with creative methodologies to reflect on the construction of gender-based knowledge in South America.

This paper and the three authors are part of a larger research project on mapping policies and knowledge construction on gender in Chile, Norway, and Argentina. The funded proposal involves interviewing gender experts. During the first meeting, both Andreas asked: Who is a gender expert and how are they defined as such? What knowledge is accepted and authorised as expert knowledge on gender and what does this authorisation do? This paper focuses on answering these questions, of how academia shapes gender knowledge, validating dominant notions of expertise. We consider how the material and regulatory conditions in academia limit diverse knowledge creation and present an exploration of creative feminist inquiry in knowledge construction within this context. The three of us authors are located in Chile and write in the wake of the feminist uprising of 2018 in Chile (Hiner and Troncoso Citation2021) and in the midst of pushback against the gains achieved in that process including threats to dismantle legalised abortion, political persecution of queer studies educators in higher education (Chilevisión Noticias Citation2021; Reyes Citation2020), and the rejection of sexual education programmes in schools (Muñoz Citation2023). We write in English due to limited Spanish publication opportunities, especially for non-empirical research (Munoz-Garcia and Chiappa Citation2017).

We begin this article with an analysis of science and colonial knowledge construction, presenting an overview of how research is rooted in coloniality and how it influences knowledge production (Fúnez-Flores Citation2023; Tuck and Gaztambide-Fernández Citation2013). We continue with the material conditions of knowledge production in Chile and our own positionalities in relation to academia and the tensions therein. After this, we present our methodologies of creative feminist inquiry inspired by the concept of rhizomes (Deleuze and Guattari Citation1987) as well as MacLure’s (Citation2013) call to wonder. In this process we found ourselves needing to territorialise the rhizome, rooting our process of knowledge construction in places, positions, and relations. Reflecting on this we conclude with the significance of considering how and from where we construct methodologies to continue to push and enjoy constructing knowledge otherwise.

Science and colonial knowledge construction

The construction of scientific knowledge is marked by the legacy of colonialism, which significantly shapes our understanding of the world. This knowledge encompasses our comprehension of the universe, ourselves, and others. Rooted in colonial and plutocratic logic (McKittrick Citation2021, 3), these frameworks profoundly influence how we perceive knowledge’s purpose and its impact on our interactions with the world. Colonialism’s foundations lie in the concept of Terra Nullius, a legal doctrine European colonisers used to legitimise taking lands from indigenous people. This notion not only impacts the sociopolitical realm but also shapes scientific knowledge’s basis (Connell Citation2007), impacting how we construct knowledge and engage with the world (Liboiron Citation2021).

This historical imprint is more than land occupation; it is closely linked to land’s conceptualisation (Tuck and Yang Citation2012). In essence, under this logic of territorial appropriation, our understanding of land is intertwined with the scientific paradigm of colonising societies. This paradigm was established by erasing indigenous connections to land through silencing and extermination (Lira, Muñoz-García, and Loncon Citation2019).

Elisa Loncon’s (Citation2022) work in Azmapu, as a Mapuche academic, highlights the tension between her grandmother’s teachings about nature’s role in their community and the contrasting school curriculum. Loncon exposes how the unequal grounds between these curricula are backed by laws, property rights, and exploitative logic. Following feminist decolonial thinkers from Abyayala, we recognise that this territorial appropriation logic is intertwined with patriarchy. These oppressive systems have moulded our worldview and are legitimised within knowledge creation, universities, and education (Espinoza et al. Citation2014). This territorial and epistemic extractivism is deeply ingrained in knowledge systems originating from the global South (Rivera Cusicanqui Citation2010). Often, it emerges through the appropriation of indigenous knowledge, simplified and decontextualised to fit a colonised academic framework (Grossfoguel Citation2016). In this translation process, essential elements may be omitted, and the knowledge is simplified (Ligia Citation2021).

Transforming these extractions involves positioning the always uncomfortable question: who produces knowledge, how and where, and for what purposes (Walsh Citation2012). For Walsh (Citation2012), this requires a mindful and ethical examination of our own actions and perspectives in relation to the historical and epistemological contexts in which we work. In this paper, we intertwine these reflections with our methodological analysis. Following Espinoza (Citation2019), we acknowledge the need to confront and expose our subjectivities and practices while challenging the dominant ways of thinking about knowledge.

From where we write, indigenous borders

In addressing these questions, inhabiting and thinking from the ancestral land of the indigenous Mapuche or Wallmapu is an integral part of our collective experience, which means that we reflect and build knowledge with an awareness of our intermediate position between academic Eurocentric, activist, and indigenous knowledge (Santamaría Citation2007).

La Frontera (the border), as historians and chroniclers used to call Wallmapu during the colonial period, is a place of coexistence, dialogues, and violence expressed through corporality and language. It has been a site of resistance and separation from the Spanish colonisers for over 300 years. In contrast to Anzaldua’s (Citation1987) conceptualisation of borderlands as the geographical, psychological, and spiritual spaces that guide identities, when we talk about the border we refer to Wallmapu as the territory of historical and ongoing conflicts over territory, including land, waters, mountains, plants, and non-human inhabitants, and rights to knowledge, living, and being (Loncon et al. Citation2023). We understand Wallmapu not as a way to make sense of identities but as a way to understand the contemporary struggle and fight for the land. Ultimately the border is a fight for existence; unlike the border perspective from Chicano studies presented by Anzaldua, Wallmapu is rooted in a Mapuche onto-epistemology that centralises land in the discussion, rather than human identities.

One of us, Ana Luisa, grew up in Wallmapu, the ancestral land of the Mapuche (neither Andrea was born there). Her experience of learning that indigenous and poor persons as less than human in the face of the French, Swiss, and Italian settlers living in the same place is embedded in our reflections on how this place of non-being is intimately tied to how science has classified people (Loncon Citation2019) and how school curriculum plays into the knowledge that should be taught (Loncon et al. Citation2023; Muñoz-García et al. Citation2022). For example, schools in Wallmapu teach Spanish, as well as French and Italian, and more recently English, but not Mapuzungun. Inhabiting Wallmapu means living with these racist and dehumanising discourses that stereotype the ‘Indian’ as a symbol of the barbaric, the past, the uncivilised, the poor, and the undesirable (Espinoza 2014). From the border the nation-state perpetuates and reproduces modern/colonial ideas, theories, methodologies, pedagogies, histories, aesthetics, values, affects, ways of knowing, sensing, being, and relating. This national curriculum’s geopolitics and coloniality constitute an enduring form of violent pedagogy that systematically suppresses and undermines alternative interpretations (Fúnez-Flores Citation2023).

The material conditions of knowledge production

Universities are intricately shaped by and play a vital role in constructing the modern/colonial capitalist world-system (Fúnez-Flores Citation2021). Universities are not only considered the place where the knowledge that leads to the moral or material progress of society is produced but as the vigilant nucleus of that legitimacy (Castro-Gómez Citation2007), positioning them as the authoritative centre for determining what constitutes legitimate knowledge.

In the global South, academic knowledge construction involves negotiating oneself, collectivities, and academic pressures. Academics are evaluated based on research publications (Munoz-Garcia and Chiappa Citation2017). Publishing comes with recognition, secures funding, and advances their careers which can lead to a focus on quantity over quality, and result in rushed or incomplete research (Shahjahan Citation2020). Previous studies (Munoz-Garcia and Chiappa Citation2017) show that academics in Chile need external funding for research, which may influence their research priorities. Overall, these pressures can create a stressful and competitive environment for academics, and can lead to a focus on short-term goals and outcomes, rather than long-term impact and relevance (Berg et al. Citation2016).

The material conditions of our work

The competitive nature of the research funding that supports this paper was achieved by aligning ourselves with the requirements of traditional science, hacking the logics of coloniality by leaving small spaces for workshops as complementary and in addition to more traditional indicators such as interviews, focus groups, and data network analysis. This means that this project is done in the interstices of the larger study, an appendage to the ‘real’ fieldwork.

In the interstices, we explored how we acquired our understanding of ourselves and territories, with the goal of contemplating the ways and sources from which we construct knowledge (Muñoz-García et al. Citation2022). Considering the constraints of academic work, we struggle and have different positionalities. Ana Luisa is principal investigator and tenured professor working in one of the most elite and demanding universities in the country, facing the ever-constant pressure to publish and to win research funding. Andrea Lira currently works in an underfunded public university in Patagonia. The only university in the area where there is little pressure to publish as well as little support for research and winning competitive funding. Andrea Barria is taking her first academic steps after finishing her undergraduate degree, and is currently not interested in pursuing an academic career, with plans to travel the world.

These aspects position us differently in terms of pressures as well as financial stability, and they are a constant tension in our work as a collective; tensions that are productive for reflection and exploration of possibilities such as in the work we will present further as well as tensions that inhibit or hinder what we can do while still responding to academic pressures. However, these different positions in regard to academia tell only a fraction of how we think about who we are and how we construct knowledge. In addition to negotiating one’s identity, academic work in the global South also requires negotiating the demands of collective communities. This can include local communities, national governments, and international organisations, all of which may have different priorities and expectations for academic research. Balancing these demands is difficult, requiring learning to navigate complex political and cultural landscapes. For us specifically, this includes handling tensions within feminist activism. There is no homogenous experience in this journey. For Ana Luisa:

It is complex to define the interweaving of academic work as a feminist activist, lesbian, first generation at the university, daughter of Wallmapu, which also means being the daughter of a Mapuche woman. I started working on education and poverty issues, then knowledge production issues in internationalisation processes, and today knowledge production and gender from feminist and decolonial perspectives. I navigate elite academic spaces where the pressure to research and publish in ‘high-impact journals’, develop ‘excellent teaching’ but also ‘have a public voice’ and ‘articulate knowledge to national policy’, is part of what is expected to build the identity of what it means to be an academic at a ‘research 1 university’. Everything that is in quotes are things I have been told I have to do. They make me smile when I fulfil them, and also make me lose sleep because I have to hold on to them to show my right to be here. Territory, class, my sexual orientation, and my condition as a woman mark me as an outsider in institutional spaces, and it is difficult to identify which of all these differentiation markers has a stronger impact on how I am constructed as an academic. At the same time, those embodied and territorialised biographies are my strength that I refuse to give up control over, allowing myself to be unpredictable to the university.

Producing gender knowledge

Beyond the broader academic landscape, the realm of gender studies involves intricate negotiations concerning the epistemic validity of feminist knowledge within Chilean academia. As part of an incident involving a self-proclaimed provocative act against gender studies departments in Chile, the collective of anonymous writers known as De Kaos (Citation2011) contend that the institutionalisation process strips the concept of gender of its political and social potency, transforming it into a stagnant and depoliticised notion.

Understanding the dynamics through which feminist concepts, discourses, and theories gain a foothold – whether temporarily or enduringly – within university settings is crucial for comprehending why feminism loses its power within the domain of gender studies in academic discourse (Costa Citation2006). Moreover, it sheds light on how certain feminist knowledge, predominantly shaped by activist endeavours, remains conspicuously invisible (Cvetkovich Citation2003; Flores Citation2013).

In this context, the idea of gender expert, which relies on the field of expertise studies, is based on objectivity and generalisation (Collins and Evans Citation2019). The study of who can be considered experts has focused on elucidating how to differentiate between individuals who may know about a subject and those who are regarded as experts (Weinstein Citation1993). Expertise studies is a field that has dedicated itself to clarifying the categories to develop an objective way of stating that someone can be considered an expert. This way of categorising expertise is built upon a view of knowledge that has been shaped by colonisation processes. The colonising processes of understanding knowledge through objectivity and generalisation have historically contributed to the marginalisation and exclusion of certain groups and ways of knowing, and gender studies are not free from these categorisations and their consequences. Therefore, it is crucial to critically examine and challenge these colonial frameworks when discussing gender experts and knowledge construction.

For Andrea Lira, the emphasis on gender experts felt uncomfortable, reaffirming Eurocentric thought logics:

For me interviewing experts was boring, I felt that there was more we could explore to think about gender knowledge construction and feminist thinking outside and beyond academia. This inherent questioning of the status quo comes in part because, at the time, I was not an academic and so had no pressure to publish or win funding, I was active in a lot of feminist activism in Patagonia. Learning from this organising and solidarity building, and I was precariously employed in various projects, one of them being this research. I could think outside the preoccupations of academic recognition because I was outside. However, this is not the only reason, as Ana Luisa affirms, mine was a position on the margins without being marginal. I come from an upper middle-class family and have the security that comes with having parents who can support me economically if I ever need it. I have a body, a name, and speech that is granted authority in most spaces in ways that I take for granted and only learned of because it was pointed out to me by others who don’t have this embodied legitimacy. I also was born in the US and grew up with my mother’s friends who became my many mothers who were exploring feminism for themselves and for us children. Knowing English and this upbringing also contributed to the possibility of thinking outside of the logics of what is expected in academia. It is both less risky and more intuitive for me and these cannot be separated because of how and where I grew up and the inherent privileges of my body that provide soft places to land.

Feminist knowledge about illegal abortion is based on an articulation between science and the experiences of previous and current generations who have assisted abortions in Chile (Urrutia Perez Citation2017). Engaging in this practice without the support of the health-care system involves considering factors such as spatial and material conditions and care strategies in order to provide knowledge to other pregnant individuals on how to safely undergo abortion when lacking the suitable and legal conditions.

As an abortion worker, Andrea Lira found academic research on abortion insufficient for her needs, finding information in the trafficking of knowledge that happened in networks of mostly lesbian activists built and shared in houses, community centres, and protected networks. In this work, there are no experts because the knowledge needed is particular, local, and rooted in people’s specific conditions. Each territory requires this specific understanding in order to build communities to support each other on work that is essential, traumatic, and beautiful.

These messy spaces of learning in activism offer diverse experiences in constructing knowledge. We have been involved in various feminist activism spaces beyond academia, including LGBTQIA advocacy, fighting for abortion rights, and working against gender-based violence in different communities. One thing we all faced in these spaces was the perception of academic and activist knowledge as contradictory. In academic settings, activist knowledge is disregarded as unscientific, while in activist spaces, there is a huge distrust of the privileges and elitism of academic knowledge.

This paper explores how we create gender knowledge, often reinforcing established authoritative views. We bridge academic gender knowledge with our perspectives, fostering discussion on this approach as methodology. Using exploratory methods, we delve into participation, limitations, and valid knowledge’s extent, crucial for understanding colonial influences in knowledge construction. Our examples emerge from scrutinising inherent tensions and the intricate interplay of colonial influences within academia.

Methodological inspirations

We drew inspiration from Deleuze and Guattari (Citation1987) and Maggie MacLure (Citation2013) to challenge our research methodologies. Despite the fact that these authors are not decolonial scholars, we view their ideas as inspirational frameworks that resonate with our ways of thinking about knowledge production from feminist decolonial perspectives. Integrating their concepts with our own theories and experiences and playing with methodology, we transform them in the work of producing questions and possible future pathways for ourselves and others to create knowledge otherwise.

Rhizomes for understanding knowledge construction

To challenge traditional notions of authority, hierarchy, and fixed identities in knowledge production, we were inspired by Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of rhizome as a fluid and interconnected approach to knowledge with multiple entry points, connections, and multiplicities. The rhizome, as opposed to a hierarchical tree-like model of knowledge representation, where ideas and concepts are organised in a linear and binary manner, is a kind of root system that grows horizontally, without a central hierarchy or structure. It is composed of nodes or points of connection which are not fixed and can multiply or branch out in unpredictable ways (Geerlings and Lundberg Citation2018). The rhizome is a non-linear, open-ended, and dynamic system that resists any attempts to reduce it to a single meaning or structure (Deleuze and Guattari Citation1987). Rhizomatic knowledge (Muñoz-Garcia Citation2017) is immanently multiple, linkable in all its dimensions; with the agential capacity of morphing into new forms, often in unpredictable directions (Guerin Citation2013).

Wonder as methodology

MacLure (Citation2013) challenges the use of coding in qualitative research, critiquing its limiting arborescent logic that constrains interpretations. Wonder disrupts these boundaries, fostering alternative understandings and unexpected insights. It is both ethical and methodological, challenging researchers’ self-certainty. MacLure (Citation2013, Citation164) calls for ‘something other, singular, quick and ineffable to irrupt into the space of analysis’.

Wonder disrupts power and knowledge boundaries, shaking coders’ self-certainty and opening doors to different understandings, including moments of indecision. For MacLure (Citation2013, Citation181), wonder ‘is an ethical as well as a methodological issue, since wonder necessarily disrupts the boundaries of power and knowledge that allow coders to maintain the enigma of their own self-certainty by rendering others legible’. She proposes assemblage using the cabinet of curiosities as an example (MacLure Citation2013), although we grappled with its colonial origins and explored unpredictable assemblages instead.

Throughout our exploration, we employed various tools like colour, shapes, and collaging. We also connected with non-academic work, notably Lambe Lambe theatre, which became part of this paper through assemblage.

Creative explorations in knowledge construction

Inspired by challenges in constructing feminist knowledge and guided by Deleuze and Guattari’s rhizome concept and Maggie MacLure’s focus on wonder over data coding, we present three instances of creative inquiry. These explore connections and patterns in research. Through photos and descriptions, we delve into how colonialism shapes knowledge production and intersections of experiences and identities, exposing tensions between conventional and rhizomatic thinking. To grasp rhizomatic knowledge and wonder, we begin with the notion that knowledge emerges from diverse sources, often overlooked or marginalised. These sources shape academia, our research inquiries, and our roles in knowledge formation. Worth noting, Lambe Lambe theatre, not originally part of our research plan, joined our reflections through Andrea’s involvement. This highlights the evolving nature of knowledge within a rhizomatic framework.

Workshops

From the conversations that came from the critique of the idea of gender experts, we developed two workshops. The first one in Patagonia aimed to explore the concept of gender experts and gender knowledge construction. We conducted the workshop there because it is home to both Andreas and because it has been historically marked by conservative and colonising approaches, silencing gender and feminist demands until the 2018 mobilisations. We invited feminist activists, students, and others to participate, and the workshop’s low stakes, being a less-regulated part of the research proposal, and the participation of allies allowed us to explore ideas and questions about gender experts. Rather than presenting our critiques, we designed activities to elicit how we learned about gender at different points in our lives and places, creating a space to play and learn together.

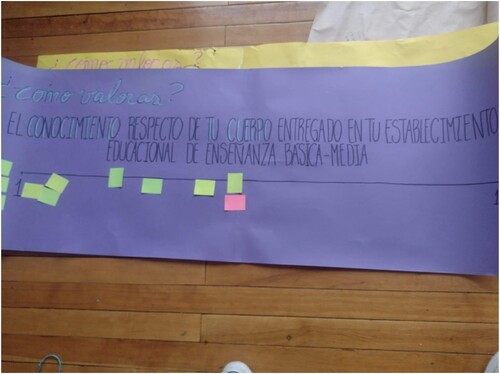

We invited participants to look at specific moments of their lives and pay attention to what they learned about gender in different institutions in their families, schools, and the media. They annotated their learning on a shared line. In the image, you see the responses to the prompt ‘what I learned about my body in high school’.

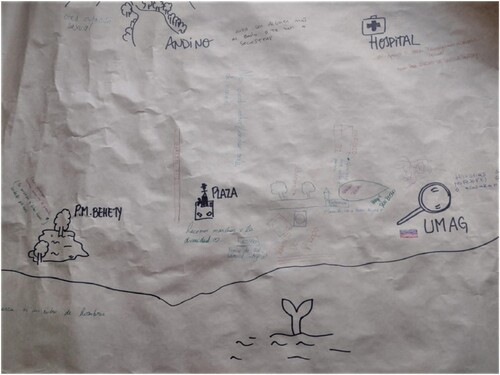

In groups, the participants created a simple map of the territory in which ‘we live’ and wrote and drew what they learned about gender in different places in the city. In the map pictured here, participants noted romance and sex in the park, repression, and control in the hospital, harassment, and experiences of sorority in the university amongst other things.

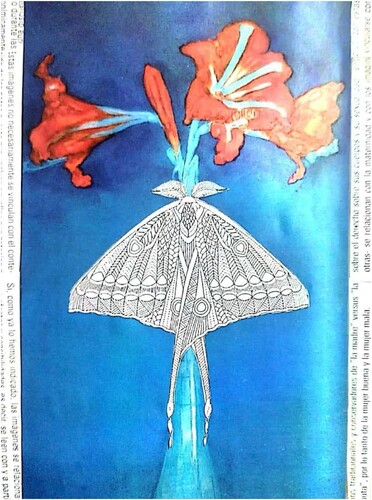

As a final activity, after a creative writing exercise that re-constructed the gender knowledge trajectories of the participants, each person created their own visual signifier, through the collage technique. The photograph shows one of these creations.

The second workshop evolved from the first, expanding on its influence. It was tailored for doctoral students, an invite-only session tied to a research project proposal supporting these students. This workshop, more formal in nature, had a hybrid setup – Andrea in Patagonia and the rest of us in Santiago.

Ana Luisa, the project’s principal investigator, led this workshop. She granted us autonomy to explore a data analysis project, inspired by the prior workshop. Guided by Maggie MacLure’s (Citation2013) work, we collectively embraced her challenge to create assemblages and delve into wonder. The three-session workshop involved engaging with study interviews using colour, shapes, and culminating in a collage exercise. This facilitated open-reflections and discussions on themes emerging from our individual exploration of the interviews.

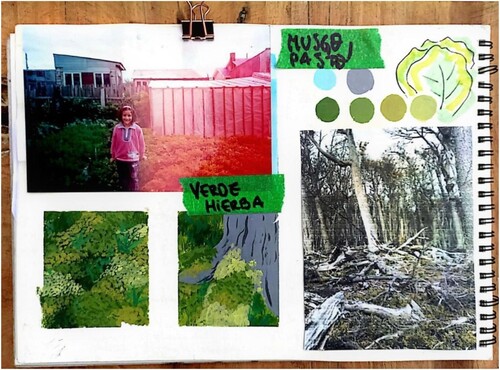

This was a colour analysis exercise of interviews. Each participant read one of the interviews and drew colours inspired by quotes, concepts, and moments of the interview. The choice of colours was made from sensations that came up while reading, not as representative categories. We each then wrote a brief text inspired by this exploration.

In the second session, we explored colours and shapes. We built colour palettes based on our previous exercise exploring their intensities and variants, and created compositions of geometric figures with the palettes developing as we did some explorations of the interviews.

This picture shows one participant’s reflection on the sustained classism and masculinisation that the interviewee talked about in her work within the academy.

Synthesis and knowledge exercise

In the third session, we used collage techniques to further explore ideas from each interview. This was done in collaboration with an artist whom we hired to teach us the techniques of collage.Footnote1

In the collage present here, the participant reflects on the balances and imbalances of doing research and what it looks like to move away from coding to make sense of data and instead be open to wonder while feeling tied to the borders and impositions of coloniality.

In both workshops, we aimed to shift away from dominant colonial practices in knowledge construction. Exploring with wonder meant that we were aware and accepting, though intimidated by the uncertainties in envisioning alternative approaches, especially regarding land and territory. Rhizomatic knowledge and employing wonder as a research approach closely aligns with critiquing our notions of gender experts.

Applying wonder as a method entails moving beyond rigid data analysis rules. Instead, we explore subjects and materials openly, allowing surprising and non-linear connections. This is vital in gender studies, where unconventional sources often go unnoticed compared to formal academic channels.

Unexpected assemblages: Lambe Lambe theatre

As we delved into the literature and reflections on our workshops, our early interpretations revealed themselves as mere starting points. Our journey of learning evolved into continuous exploration and inquiry. This process illuminated how our work intertwined with other explorations in methodology and knowledge creation within our lives. A prime example was Andrea Barría’s involvement in Lambe Lambe theatre, focusing on genealogical microhistories that embrace collective and political memory. Lambe Lambe theatre unfolds within a small space, akin to a box observed by a solitary spectator, narrating stories through puppets and objects accompanied by headphone-delivered sound. Despite its unrelated nature to our funded project, Andrea’s endeavour resonated with our discussions on method and knowledge construction, encapsulated in Andrea’s words:

I decided to start my Lambe Lambe by linking edges from the microhistories (or the microroots of the forest) and observing features of my genealogy, because inevitably when I think about the contradictions of my class, of my town, I see my family and I remember the memories of dispossession, trips, and adaptations that have passed on to me. I wonder what knowledge have I inherited that lets me be here writing these lines? Which ones are mine? Which ones are intrinsically part of social memory?

I observed and transformed my ancestor’s genealogical microhistory, trying to open possibilities of knowledge in resistance within a cloudy ghostly historical context, to open emotional, experiential, and political knowledge in a historically infertile ground for us, the nomadic women of the southern south.

While she tells me about the migratory journey we cook, eat, and take a nap in between. It is common for us to do these activities at home. The heat expelled by the cast iron stove allows it, and floods the environment of the ‘nest’. Between conversation and conversation, she tells me her trajectory with the land.

I looked for photographs of the farm, the patio of my grandmother’s house, which for years was planted with the techniques inherited from Chiloé. I explored the shapes and colours it has had in the family’s memorial archive. We talked with the rest of the family, remembering what that same transformative land was like in other times.

Finally, with my grandmother we worked on the knowledge of the harvest. She told me and showed how she managed to transport the trade of sowing to a field with different characteristics from those she knew. Lands that had no indications of having been worked, previously planted.

This narrative and sound exploration of Lambe Lambe, particularly through Andrea’s grandmother’s voice recounting her experiences, encapsulates the timbre of voice embodying transgenerational, nomadic, mournful, and silenced knowledge. This knowledge reflects the experiences of people migrating in the face of systemic impoverishment conditions. Such artistic expressions serve as more than mere communication tools; they are embodied research questions, forging complex paths that transform upon interacting with audiences and territories.

Moreover, this connection with artistic inquiry and expression intertwines with ongoing critiques of who is acknowledged as an expert within knowledge construction processes. The exploration of unconventional avenues like Lambe Lambe theatre challenges traditional hierarchies and definitions of expertise. This aligns with broader discussions surrounding the legitimacy and recognition of diverse forms of knowledge and expertise, ultimately disrupting the established norms of what constitutes authoritative insight within academia.

On finding methodological ways through place, territory, and wonder

Redefining gender knowledge from a decolonial perspective challenges binary structures and embraces diverse viewpoints in gender studies. Decolonisation is an ongoing task in our knowledge-building practices. This approach does not require us to dismiss concepts inherited from European academia, rather we acknowledge their value in questioning homogenising notions of knowledge and also questioning where they are lacking and the colonial implications of their theory.

The workshops and the connection we found in Andrea’s Lambe Lambe became a catalyst for the realisation that, for us, constructing knowledge rhizomatically, with openness and uncertainty, could coexist with a recognition of the importance of rootedness in land and place. In this exploration we came to question the notion of the rhizome as detached and disembodied, and instead saw the potential for knowledge to emerge from and be shaped by the specific contexts in which we live, learn, and exist.

As we engage with the concept of the rhizome through a decolonial lens, we conclude with the necessary critique of it as an unrooted entity. While the rhizome offers a powerful framework for understanding knowledge production in non-linear and interconnected ways, we realise that rooting it solely in abstract notions of connectivity can overlook the profound relationship between knowledge and land, place, and territory.

Redefining knowledge as rhizomatically created materiality from a decolonial lens implies a conceptual shift that demands an acknowledgment of rootedness in specific territories. This perspective signifies a localization of the rhizome, emphasizing the interconnectedness and grounding of knowledge within particular geographical and cultural contexts.

By centring land and place within the rhizomatic framework, we strive to foster a deeper understanding of the complex entanglements between knowledge, power, and territory. We acknowledge that knowledge construction is not a neutral endeavour but is intertwined with histories of dispossession and extraction. We aim to shift away from harmful exploitative practices and engage in knowledge production that respects the interconnectedness of people, land, and communities.

This recognition allows us to view this knowledge as incomplete, diverse, and unrestricted. It prompts us to question official narratives, revealing the existence of alternative forces beneath the surface. These forces come to life through varied interactions and innovations, weaving a complex tapestry of intertwined creation that is in a perpetual state of both connection and divergence (Campbell Citation2008, 9).

Ultimately, our workshops evolved into spaces for scrutinising the very foundation of knowledge construction, focusing on gender expertise and the effects of the authorisation process. These efforts further underline the need for diverse voices to be recognised as experts, dismantling the exclusivity that can surround the title.

Final thoughts on gender experts and knowledge construction

The concept of gender experts warrants critical examination in research on feminist knowledge. Our journey through workshops, creative inquiry, and decolonial perspectives revealed to us the necessary acknowledgement that knowledge, particularly in the realm of gender studies, is multifaceted and diverse, originating from various sources and experiences.

The process of authorising gender expertise should go beyond narrow boundaries. This critique is relevant as we often see gender expertise confined to traditional academic voices. In doing so, we can move towards a more inclusive and comprehensive understanding of gender, one that respects the interconnectedness of knowledge, identity, and experience.

Inspired by rhizomatic knowledge and wonder, we were able to challenge our own conventional notions of expertise on gender limited to traditional academic voices. Instead, we argue for recognising diverse voices and experiences as valid sources of gender knowledge.

This process would not be possible if we were not capable of questioning the forms that the academy has legitimised for centuries to build knowledge and the colonial structure interwoven in feminist doing. However, it is important to acknowledge that our understanding remains in flux, characterised by uncertainty and open-ended reflection. The process of learning and unlearning is ongoing, and we continue to grapple with the complexities and challenges inherent in decolonising knowledge construction. We recognise that there are no definitive conclusions, but rather an ongoing exploration of possibilities and a commitment to engage critically with feminist and decolonial theories.

Fostering a sense of wonder emerges as a means for embracing this uncertainty and openness. These reflective and practical processes around more flexible mechanisms for conducting research have allowed us to rediscover disciplines and types of knowledge that many times we wanted to abandon due to their inherent colonial and class barriers.

Creative research has opened kinder, connected, creative, and political spaces of understanding for us. Seeing, acknowledging, and feeling that all people are bearers of knowledge and capable of building research for various purposes moves us and makes sense to us. This knowledge is situated, transformative, and circulates between communities that migrate and accumulate knowledge. It is necessary to open the way to flexible investigative mechanisms that allow other flows and flashes, which are not always perceived in academic publishing houses.

The knowledge trajectories and creative analysis workshops were important to put our methodologies to the test and to sow concern in others to look for these imperceptible glimpses from the theoretical. This process encourages us, moreover, to continue building instances of awareness and collective training around creative research mechanisms.

For readers interested in exploring creative methodologies, remember that the key is not to replicate our steps, but to unlock connections between what you read, experience, and your academic position. Let these insights guide your exploration of data and knowledge construction processes.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Andrea Lira

Andrea Lira is an associate professor at Universidad de Magallanes, Chile. Her research focuses on issues of knowledge construction from feminist and decolonial perspectives. She works with teachers and other education workers in Patagonia, developing participatory action research projects in the Centro de Liderazgo Educativo UMAG. In this paper she builds on the work of research and feminist activism to think about the ethics of how we build knowledge in research. Postal address: Av. Pdte. Manuel Bulnes 01890, Punta Arenas, Magallanes y la Antártica Chilena. Email: [email protected]

Andrea Barría

Andrea Barría is an independent researcher, Patagonian resident, and a nomadic soul. She dedicates herself to the search for territorial and collective memories, conducting participatory research that links creative methodologies of scenic expression and visual art. Her explorations, primarily focused on childhood memories and feminisms, have allowed her to connect with various artistic and political-territorial groups, making her part of an activist network for human rights and a promoter of citizen participation processes.

Ana Luisa Muñoz-García

Ana Luisa Muñoz-García holds a PhD in Educational Culture, Policy, and Society from SUNY at Buffalo, USA. She is an associate professor at the Faculty of Education, Pontifical Catholic University of Chile. Within her academic roles, Ana Luisa holds the position of Deputy Director at the Gender Office in the School of Education. She is the Director of the Department of Curriculum, Evaluation, and Technology. Ana Luisa’s research focuses on issues related to academia, knowledge, internationalisation, and gender in higher education. She is leading a project titled ‘Gender and Knowledge in Academia’, funded by the National Agency of Research and Development (ANID). Beyond her scholarly pursuits, Ana Luisa is a dedicated feminist activist who actively works towards dismantling patriarchal structures entrenched within academic institutions. Her commitment extends to addressing gender-based violence and discrimination across various spheres.

Notes

1 The specific details and outcomes of the collage workshop are not elaborated in this paper due to space limitations, but they contributed significantly to our broader exploration of knowledge construction methodologies. The technique of collage was led by Catalina Valdes whose work you can find at https://www.instagram.com/hechoamanocollages/.

References

- Anzaldua, Gloria (1987) Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza, San Francisco: Aun Lute.

- Berg, Lawrence D., Edward H. Huijbens, and Henrik Gutzon Larsen (2016) ‘Producing anxiety in the neoliberal university’, The Canadian Geographer/le Géographe Canadien 60(2): 168–180.

- Campbell, Neil (2008) The Rhizomatic West: Representing the American West in a Transnational, Global and Media Age, Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

- Castro-Gómez, Santiago (2007) ‘Decolonizar la universidad. La hybris del punto cero y el diálogo de saberes’, in S. Castro-Gómez and R. Grosfoguel (eds.) El giro decolonial: Reflexiones para una diversidad epistemica más allá del capitalismo global, Bogotá D.C.: Siglo del Hombre Editores. 79–91.

- Chilevision Noticias (2021, Octubre, 21) Universidad de Chile rechazó oficio de dos diputados sobre ideología de género: “Es una suerte de inquisición”. https://www.chvnoticias.cl/nacional/universidad-chile-rechazo-oficio-diputados-ideologia-genero_20211021/.

- Collins, Harry and Robert Evans (2019) Rethinking Expertise, Chicago IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Connell, Raewyn (2007) Southern Theory: The Global Dynamics of Knowledge in Social Science, Sydney: Allen & Unwin.

- Costa, Claudia de Lima (2006) ‘Lost (and found?) in translation: feminisms in hemispheric dialogue’, Latino Studies 4(1): 62–78. doi:10.1057/palgrave.lst.8600185.

- Cvetkovich, Ann (2003) Archive of Feelings, 2008, Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- De Kaos (2011, 23 March) Urgente: No al Cierre de los Estudios de Género en la Universidad de Chile, Urgente: No al Cierre de los Estudios de Género en la Universidad de Chile – Kaos en la red. Accessed 12 September 2023.

- Deleuze, Gilles and Felix Guattari (1987) Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, Minneapolis MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Espinoza, Yuderkys (2019) ‘Hacer genealogía de la experiencia: el método hacia una crítica a la colonialidad de la Razón feminista desde la experiencia histórica en América Latina [Doing genealogy of experience: towards a critique of the coloniality of feminist reason derived from the historical experience in Latin America]’, Revista Direito e Práxis 10(3): 2007–2032. doi:10.1590/2179-8966/2019/43881.

- Espinoza, Yuderkys, Diana Gomez, and Karina Ochoa (2014) Tejiendo de otro modo: Feminismo, epistemologia y apuestas descoloniales en Abya Yala, Editorial, Colombia: Universidad del Cauca.

- Flores, Valeria (2013) ‘Rara’, in Fabi Tron and Valeria Flores (eds.) Chonguitas: Masculinidades de niñas, Neuquén: La Mondoga Dark, 127–131.

- Fúnez-Flores, Jairo I. (2021) ‘Toward a transgressive decolonial hermeneutics in activist education research’, in C. Matias (ed.) The Handbook of Critical Theoretical Research Methods in Education, New York: Routledge, 182–198.

- Fúnez-Flores, Jairo I. (2023) ‘Anibal Quijano:(Dis) entangling the geopolitics and coloniality of curriculum’, The Curriculum Journal.

- Geerlings, Lennie and Anita Lundberg (2018) ‘Global discourses and power/knowledge: theoretical reflections on futures of higher education during the rise of Asia’, Asia Pacific Journal of Education 38(2): 229–240. doi:10.1080/02188791.2018.1460259.

- Grosfoguel, Ramón (2016) ‘Del extractivismo económico al extractivismo epistémico y al ex-tractivismo ontológico: una forma destructiva de conocer, ser y estar en el mundo’, Tabula Rasa 24: 123–143. doi:10.25058/20112742.60.

- Guerin, Cally (2013) ‘Rhizomatic research cultures, writing groups and academic researcher identities’, International Journal of Doctoral Studies 8: 137–150. doi:10.28945/1897.

- Hiner, Hillary and Lelya Troncoso (2021) ‘Lgbtq+ tensions in the 2018 Chilean feminist Tsunami’, Bulletin of Latin American Research 40(5): 679–695. doi:10.1111/blar.13331.

- Liboiron, Max (2021) Pollution is Colonialism, Durham: Duke University Press.

- Ligia, (Licho) López López (2021) ‘Fractal education inquiry’, Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 42(2): 251–266. doi:10.1080/01596306.2019.1613958.

- Lira, Andrea, Ana Luisa Muñoz-García, and Elisa Loncon (2019) ‘Doing the work, considering the entanglements of the research team while undoing settler colonialism’, Gender and Education 31: 475–489. doi:10.1080/09540253.2019.1583319.

- Loncon, Elisa (2019) ‘Racismo encubierto y la resistencia desde la diversidad epistémica mapuche’, Revista anales 16: 249–265.

- Loncon, Elisa (2022) Azmapu: Aportes de la filosofía Mapuche para el cuidado del Lof y la madre tierra, Santiago, Chile: Editorial Planeta.

- Loncon, Elisa, Alvaro Gainza, Natalia Hirmas, and Diego Mellado (2023) Colonialismo cultural y ontología indígena en comunidades pewenche de Alto Bío-Bío, Santiago, Chile: LOM Ediciones.

- MacLure, Maggie (2013) ‘Classification or wonder: coding as an analytic practice in qualitative research’, in R. Coleman and J. Ringrose (eds.) Deleuze and Research Methodologies, Edinburgh, UK: Edinburgh University Press, 164–183.

- McKittrick, Katherine (2021) Dear Science and Other Stories, Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Muñoz, Gabriel (2023, Junio 20) Con su campaña contra la ESI: Republicanos oculta una tragedia social contra niños y adolescentes, Izquierda Diario. https://www.laizquierdadiario.cl/Con-su-campana-contra-la-ESI-Republicanos-oculta-una-tragedia-social-contra-ninos-y-adolescentes.

- Muñoz-Garcia, Ana Luisa (2017) ‘Rhizomatic knowledge in the process of international academic mobility’, in D. Proctor and L. Rumbley (eds.) The Future Agenda for Internationalization in Higher Education, Next Generation Insights Into Research, Policy, and Practice, London: Routledge, 133–143.

- Munoz-Garcia, Ana Luisa and Roxana Chiappa (2017) ‘Stretching the academic harness: knowledge construction in the process of academic mobility in Chile’, Globalisation, Societies and Education 15(4): 635–647. doi:10.1080/14767724.2016.1199318.

- Muñoz-García, Ana Luisa, Andrea Lira, and Elisa Loncon (2022) ‘Knowledges from the South: reflections on writing academically’, Educational Studies 58(6): 641–656. doi:10.1080/00131946.2022.2132394.

- Reyes, Felipe (2022, Diciembre, 26) U. de Chile lamenta “tesis pedófila” viralizada en redes y afirma que fue de “corte puramente teórico”, BioBio Chile. https://www.biobiochile.cl/noticias/nacional/chile/2022/12/26/u-de-chile-lamenta-tesis-pedofila-viralizada-en-redes-y-afirma-que-fue-de-corte-puramente-teorico.shtml.

- Rhee, Jeong-Eun (2020) Decolonial Feminist Research: Haunting, Rememory and Mothers, New York: Routledge.

- Rivera Cusicanqui, Silvia (2010) Ch'ixinakax utxiwa. Una reflexión sobre prácticas y discursos descolonizadores, Buenos Aires: Tinta limón.

- Santamaría, Carolina (2007) ‘El bambuco y los saberes mestizos: academia y colonialidad del poder en los estudios musicales latinoamericanos’, in S. Castro-Gómez and R. Grosfoguel (eds.) El giro decolonial: Reflexiones para una diversidad epistemica más allá del capitalismo global, Bogotá: Siglo del Hombre Editores. 195–216.

- Shahjahan, Riyad A. (2020) ‘On ‘being for others’: time and shame in the neoliberal academy’, Journal of Education Policy 35(6): 785–811. doi:10.1080/02680939.2019.1629027.

- Tuck, Eve and Ruben Gaztambide-Fernández (2013) ‘Curriculum, replacement, and settler futurity’, Journal of Curriculum Theorizing 29(1): 72–89.

- Tuck, Eve and K. Wayne Yang (2012) ‘Decolonization is not a metaphor’, Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 1(1): 1–40.

- Urrutia Perez, Fernanda (2017) Experiencia encarnada de mujeres que han vivenciado la práctica del aborto inducido directo en Chile (Doctoral dissertation, Universidad Academia de Humanismo Cristiano).

- Vivaldi, Lieta and Valemtina Stutzin (2017) ‘Mujeres víctimas, fetos públicos, úteros aislados: tecnologías de género, tensiones y desplazamientos en las representaciones visuales sobre aborto en Chile’, Zona Franca 25: 126–160.

- Walsh, Catherine (2012) ‘“Other” knowledges, “other” critiques: reflections on the politics and practices of philosophy and decoloniality in the “other” America’, Transmodernity: Journal of Peripheral Cultural Production of the Luso-Hispanic World 1(3): 11–27.

- Weinstein, Bruce D. (1993) ‘What is an expert?’, Theoretical Medicine 14: 57–73. doi:10.1007/BF00993988.