ABSTRACT

Research that attempts to understand why young people commit sex crimes points to an array of family factors that may uniquely contribute to sexual offending over general juvenile delinquency. This study examines the potentially moderating role of disrupted caregiving in the relationship between offending and caregiver-child relationship quality. Two distinct moderators were tested: gender of caregiver and biological relationship between caregiver and child. Results indicate that juvenile sexual offenders have particularly poor relationships with their primary caregivers compared to incarcerated non-sexual offenders and community controls. Furthermore, sexual offenders with male caregivers were found to have lower relationship quality scores than sexual offenders with female caregivers. In contrast, sexual offenders raised by non-biological caregivers reported better relationship quality than did offenders raised by their biological parents. These findings suggest opportunities for early intervention, before caregiving is disrupted.

Introduction

Whether juvenile sexual offenders (JSOs) should be thought of as a distinct population from general juvenile delinquents continues to be a subject of much debate (Seto & Lalumière, Citation2010; Smallbone, Citation2006; Starzyk & Marshall, Citation2003). Though the population of youth who are arrested for sexual offences are overwhelmingly male, they are also so vastly heterogeneous that research has struggled to identify a consistent profile for JSOs (Righthand & Welch, Citation2004). However, recent reviews have identified some areas of commonality among youth who commit sex crimes. Family factors have emerged as an important area in which JSOs may be set apart from youth who do not engage in sexually aggressive acts (Felizzi, Citation2015a). This line of research may be especially worthwhile as family contexts are proving to be essential when researchers and treatment professionals focus on issues of primary prevention (Ryan, Leversee, & Lane, Citation2011), recidivism (Zankman & Bonomo, Citation2004), and treatment trajectories for sexually aggressive youth (Borduin, Schaeffer, & Heiblum, Citation2009; Henggeler et al., Citation2009; Yoder, Citation2014). Thus, the continued development of this line of inquiry is paramount.

For at least a half century, parental influence has been at the forefront of the discussion of criminal behaviour in juveniles. Much of this work has utilised attachment theory to explain how parents may influence the delinquent behaviour of their children (Bowlby, Citation1944, Citation1969, Citation1982). Proponents of attachment theory argue that a child’s relationship to their early primary caregivers shapes their subsequent interpersonal interactions throughout their lifetimes. The largely successful application of attachment theory to the etiology of sexual offending has been explored with both adult and juvenile populations (Keogh, Citation2012; Rich, Citation2006). These studies suggest that insecurely attached children tend to experience isolation, loneliness, and frustration that may express itself as sexual aggression in their teen and adult years (Marshall, Citation1989; Seidman, Marshall, Hudson, & Robertson, Citation1994; Ward, Hudson, & Marshall, Citation1996). Among adults, sexual offenders have been shown to be less securely attached than their incarcerated and non-incarcerated peers (Sigre-Leirós, Carvalho, & Nobre, Citation2016; Smallbone & Dadds, Citation1998; Smallbone & Dadds, Citation2001). In fact, as many as 93% of adult sexual offenders have shown insecure attachment patterns (Lyn & Burton, Citation2005; Marsa et al., Citation2004). Insecure attachments are common in juvenile samples, as well. Smallbone (Citation2006) and Whitaker et al. (Citation2008) discovered that young sexual offenders were less attached to parents than were other incarcerated youth, while Funari (Citation2005) found that JSOs had higher levels of disorganised attachment than other violent or non-violent juvenile offenders.

These findings may be explained by the body of literature which explores the likelihood that JSOs have experienced caregiver disruption (Seto & Lalumière, Citation2010; Tidefors & Strand, Citation2012; Worley, Church, & Clemmons, Citation2012). The term “caregiver disruption” is used here to describe any instance in which a child receives insufficient or substitute care as a result of their biological parents’ inability to meet their physical and emotional needs. Meta-analytic results indicate that between 27–87% of JSOs have experienced disrupted caregiving, depending on the operationalisation of “disruption” in the particular study (Seto & Lalumière, Citation2010). Recent works touching upon caregiver disruption report that, compared to other incarcerated and non-incarcerated youth, JSOs are more likely to have: lived in an out-of-home placement (Duane, Carr, Cherry, McGrath, & O'Shea, Citation2003; Funari, Citation2005); lived in a single-parent family (Margari et al., Citation2015), and witnessed or experienced high levels of domestic violence, physical punishment, and parental substance abuse (Ryan et al., Citation2011). Furthermore, instances of disrupted caregiving often negatively impact the relationships between youths and their guardians. JSOs frequently report poor or problematic relationships with their caregivers (Yoder, Dillard, & Stehlik, Citation2018) and have significantly greater deficits in relationship quality when compared to non-sexual offenders (Yoder, Leibowitz, & Peterson, Citation2016). Thus, caregiver disruption must be considered a potentially precipitating factor for sexual offending, insofar as it may exacerbate the poor attachment relationships between a youth and their parents (Felizzi, Citation2015b).

Yet, despite the relative importance of caregiver disruption, some areas of disruption remain unexplored. For instance, the impact of the gender of the youths’ primary caregivers, especially with regard to male caregivers, is deserving of increased attention. To date no study has explicitly examined the father-son relationships of JSOs (e.g. single father, step-father, absent father, in a nuclear family). Studies which have examined both mother and father dynamics have found that juvenile sexual offenders often have male caregivers who are dominant and controlling (Mathe, Citation2007). Further, young sexual offenders feel more alienated and less trusting of their fathers than do youth who commit other types of crimes (Yoder et al., Citation2018).

More is known about the role of male caregivers in the development of juvenile delinquency generally. Coles (Citation2015) demonstrated that youth living with only male caregivers were more likely to engage in delinquent behaviour or be diagnosed with an externalising disorder than those living in households with women. Similarly, Breivik and Olweus (Citation2006) found that youth living solely with single-fathers had significantly higher levels of externalising problems than did children living with single mothers. Given the overlap between JSOs and their non-sexually offending peers, it seems possible, but yet to be examined, that father-son relationships may impact sexual offending as well as general delinquent behaviour.

Non-biological guardians represent another under-investigated form of caregiver disruption for JSOs. Some research has shown that JSOs are more likely than average to live with a non-biological caregiver (Duane et al., Citation2003; Felizzi, Citation2015a; Funari, Citation2005). Yet little is known about how that relationship impacts their sexual offending behaviour. Even though the literature on non-biological caregivers and delinquency does not distinguish sexual crimes from other offences, its findings offer some guidelines for future JSO investigations. Generally, this research concludes that living with non-biological guardians is associated with delinquent and externalising behaviours in young people. Children who live in foster care (Apel & Kaukinen, Citation2008), with adoptive families (Juffer & van Ijzendoorn, Citation2005; Miller, Fan, Christensen, Grotevant, & Van Dulmen, Citation2000), or in step-families (Bronte-Tinkew, Scott, & Lilja, Citation2010; Evenhouse & Reilly, Citation2004) have all been shown to be at unusually high risk for delinquency. The contributions of non-biological parenting to general juvenile offending justifies more specific research into juvenile sexual offenders’ relationships with their non-biological guardians.

In addition to examining the potentially moderating role of disrupted caregiving in the relationship between offending and caregiver-child relationship quality, this study also strives to address a number of significant gaps in the literature. Specifically, it aims to: (1) determine whether youth who commit sex crimes perceive their relationships with their primary caregivers differently than do general juvenile delinquents or non-offending youth; and (2) specify the impact of caregiver gender and non-biological status on caregiver-child relationship’s quality. In order to do so, the following hypotheses are proposed: Hypothesis 1 – Offence status is expected to predict relationship quality scores such that JSOs will have the lowest mean relationship score of any offence type, closely followed by violent juvenile delinquents. Non-violent incarcerated youth and community controls are expected to have higher relationship scores, with community controls reflecting the best overall relationship quality; Hypothesis 2 – Gender of the primary caregiver is expected to moderate the youth’s perceived relationship quality with their caregiver such that youths who identify males as their primary caregivers are expected to report poorer quality relationships than youths who identify females as their primary caregiver; Hypothesis 3 – Biological status is expected to moderate the youth’s perceived relationship quality with their caregiver such that youth raised by their biological parents are expected to have higher relationship quality scores than those raised by a substitute guardian.

Methods

Participants

The data utilised in this study comes from a larger investigation exploring the modus operandi of young male sexual offenders (CDC Grant R49/CCR016517-01). Female offenders were excluded from this study. Participants included convicted juvenile offenders who were incarcerated in correctional facilities in Florida, New York, Oregon, South Carolina, and Texas. A second sample of juvenile control participants were recruited from community centres in those same states.

Thus, participants in this study (n = 826) comprised four distinct groups. Juvenile sexual offenders (JSOs, n = 310) were found guilty of committing a sexual offence before their 18th birthday and were incarcerated for that sex crime. Violent juvenile delinquents (JD-Vs, n = 119) were incarcerated for a crime they committed as a youth that was intended to cause harm against persons (e.g. murder, assault, robbery). Nonviolent juvenile delinquents (JD-NVs, n = 139) had identical screening criteria to JD-Vs, except with regard to the crime for which they were incarcerated. These youths committed crimes that did not include an intent to harm others (e.g. car theft, drug possession, destruction of property). Finally, juvenile control participants (JCs, n = 258) were non-incarcerated youth who had never been convicted of a crime. Screening criteria ensured that the youth were literate by means of the Wide Range Achievement Test – Third Edition (WRAT-3; Wilkinson, Citation1993), and that they did not have an interfering mental illness (e.g. psychotic disorder, depressive disorder) based on staff report.

All youth identified as male. The average age in this sample was 15.90 years old (SD = 1.77 years). Overall, 41% of youth identified as White/Caucasian, 21.6% identified as Black/African American, 17.1% identified as Hispanic/Latino and 23.1% identified as Other or Mixed Race. In the overall sample, 52.4% of the participants reported that they were raised in nuclear families (See ).

Table 1. Raw count and percentages of disrupted caregiving by offense type.

Measures

Demographics

This measure asked participants questions regarding their demographic characteristics. The questions used in the current study solicited the participants’ (1) age, (2) biological sex, (3) race or ethnicity, and (4) current education level. The youth were also asked to identify their primary caregiver(s) for each year of their life (1–17). Additionally, participants were asked to indicate at which ages they switched or added a primary caregiver.

Perceived relationship with supervisor scale

A six-item questionnaire was used to examine how the youth perceived their relationship with their primary caregivers (PRSS; Kaufman, Citation2001). This scale was developed specifically for a larger study to examine the relationship between juvenile offenders and their parents or guardians (i.e. their “supervisors”). For incarcerated juveniles, the instructions asked that they report on the last year in which they lived in the community. For juvenile control participants living in the community, they were simply asked to report on the previous year. The six items included in this measure were developed based on the existing research literature, as well as input from an advisory group of “experts” from the areas of adolescent development, parenting, and juvenile delinquency and sexual offending.

The instructions for completing this measure included a definition of the term “supervisor” as “an adult who was in charge of you (like a parent, guardian or baby-sitter).” Youth were asked to indicate who their primary supervisors were and to list what days of the week and times of day those adults were responsible for their care. Project staff were available to answer questions, while participants completed this and other study measures. Participants were asked to indicate their answers on a five-point Likert scale where 0 = never and 4 = always. Items assessed perceptions of trust (“my supervisor trusted me”), acceptance (“my supervisor accepted me for who I am”), morality (“my supervisor expected me to do the ‘right thing’”), understanding (“my supervisor understood where I was coming from”), respect (“my supervisor asked for my opinion on things”), and attention (“my supervisor asked about personal things”). Thus, the dependent variable used for these analyses is the composite mean score of these six items.

Offence history

Incarcerated youth were asked to indicate the criminal charge that resulted in their incarceration. They additionally reported the total number of times they had been arrested, their age at their first arrest, the age that they began engaging in criminal behaviour, and the date that they began serving their sentences. These questions also established that the juvenile controls did not have a criminal record.

Procedures

University institutional review board (IRB) approval was obtained before the beginning of data collection. Since the current project relied solely on a secondary analysis of de-identified data, the IRB board determined that this study did not require additional review and approval.

The original data collection procedure was as follows: as incarcerated youth are unable to independently consent to research participation in accordance with APA ethical standards, youth were presented with an assent form that was then read aloud to them. This assent form described the purpose, risks, and benefits of the study. Youth were assured that their participation was voluntary and would be kept anonymous. Those who chose to participate in this study signed the assent form. Their signature indicated that they understood their role in this research and that they would like to participate. Participating facilities determined that obtaining parental consent was not possible and that the institution’s consent was sufficient, to which the IRB concurred. Therefore, consent was provided by administrative staff at the juvenile correctional facilities, who have legal custody of the youth during their incarceration. Juvenile control participants were recruited from community centres located in the same states as the detention facilities. Parental consent was obtained for all youth recruited from the community.

On average, participants took 1.5 h to complete all the questionnaires included in the larger study. More than 98% of youth returned completed packets. Packets were then returned to the university where they are maintained in a locked filing cabinet and password protected files.

Results

Preliminary analyses

Exploratory factor analysis

The factor structure of the items on the Perceived Relationship with Supervisor Scale (Kaufman, Citation2001) was explored before proceeding with the analyses. An eigen-analysis was conducted using SPSS 24 to determine if a single-factor structure best explained the pattern of data from this measure. Results from this analysis determined that a single-factor model was indeed best, as indicated by Kaiser’s criteria for Eigenvalues as well as by examining a Scree Plot and the item’s correlation matrix to determine the amount of variance explained by this assessment device. All items loaded adequately and cleanly onto one factor, with the smallest loading being .35 and the highest being .83. Cronbach’s alpha was also calculated and reflected good internal consistency (α = .86). Thus, all six items in this measure are used in the subsequent analyses to represent youths’ perceived relationship with their primary caregivers.

Sample differences

Offence groups were examined for systematic differences on variables that may impact study findings but were not investigation outcomes. Juvenile control participants were significantly younger (M = 14.7, SD = 1.73) than were any of the incarcerated groups (JSO: M = 16.7, SD = 2.16; JD-NV: M = 16.4, SD = 1.27; JD-V: M = 17.1, SD = 1.72), F(3,839) = 74.6, p < .001. Despite the significance of this difference, these age ranges all fall within the traditional high-school years of middle adolescence (Patterson, Citation2008; Santrock, Citation2013), suggesting that all four groups of youth are developmentally comparable. A chi-square analysis revealed that White participants were more likely to fall in the JSO offence-type than any other group, χ2 (9, N = 888) = 111.68, p < .01. This finding mirrors United States national statistics, which suggests that White youth are more likely to be incarcerated for a sexual offence than are any other ethnic or racial group (Greenfeld, Citation1997).

Offence groups were also examined for differences in the types of disrupted caregiving they experienced (See ). Overwhelmingly, JSOs experienced higher rates of caregiver disruption than all other groups, χ2 (3, N = 840) = 133.047, p < .001. Only 32.3% of JSOs reported that they had lived in a nuclear family for their entire lives prior to incarceration. In contrast, 74.4% of juvenile controls reported living in nuclear families, as did 55% of both the violent and nonviolent incarcerated youth.

Inferential analyses

Overall relationship quality

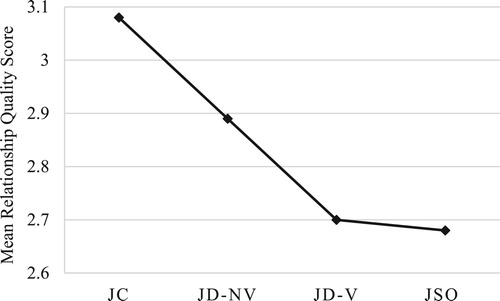

Hypothesis One, stating that JSOs were expected to report the lowest relationship quality scores of all offence types, was partially confirmed. A univariate analysis of variance found that offence groups differed significantly from one another in terms of perceived relationship quality with their caregivers, F(3,834) = 8.34, p < .001. Levene’s test for equality of error variances was significant, F(3,834) = 14.82, p < .001, therefore, the Games-Howell post-hoc test was used to assess group differences (See ). Juvenile sexual offenders (M = 2.68, SD = .84) and juvenile delinquents – violent (M = 2.69, SD = 1.10) had significantly lower relationship quality scores than did juvenile control youth (M = 3.08, SD = .70). JSO and JD-V youth did not differ from one another in terms of relationship quality. Non-violent incarcerated youth (M = 2.84, SD = .84) formed a middle group that did not significantly differ from either the high-scoring juvenile control group, or the low-scoring JSO/JD-V group.

Caregiver disruption moderators

Since significant differences in overall relationship quality was found between groups, a moderated regression analysis was conducted to test the remaining hypotheses. The primary predictor in the regression was offence type (JC, JD-NV, JD-V, JSO). The dependent variable was the composite mean value of the Perceived Relationship with Supervisor Scale. The overall model was significant (R2 Adj. = .126, F(11,862) = 6.066, p < .001).

Male caregivers

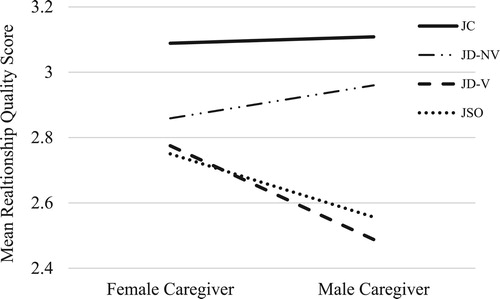

Hypothesis Two, which predicted that gender of the primary caregiver would moderate the youth’s perceived relationship quality with their guardian, was partially confirmed. Youth who indicated that their primary caregiver was male (biological father, step-father, adoptive father, grandfather) were grouped together for these analyses. Using juvenile control youth with female primary caregivers as the constant, the interaction terms for JSOs (β = −.324, t(866) = −2.513, p < .05) and JD-Vs (β = −.489, t(866) = −1.956, p < .05) were significant. Thus, there is a greater drop in relationship quality between JSOs/JD-Vs with male caregivers compared to female caregivers than the corresponding drop for control youth. The simple effect for juvenile controls was non-significant (β = .056, t(866) = .673, p = ns), indicating that there is no discernible change to relationship quality between juvenile controls with female or male caregivers. Similarly, no significant interaction was observed for nonviolent juvenile delinquents with regard to caregiver gender (β = .236, t(866) = 1.046, p = ns). Thus, this result suggests that the adverse impact of caregiver gender on relationship quality only occurs when juvenile sexual offenders or violent juvenile delinquents are being primarily cared for by men (See ).

As a significant interaction was found, further analyses were conducted in order to gather a full picture of the significance of these results. First, in order to assess differences between JSOs with female guardians and JSOs with male guardians, the reference group was changed so that JSOs with female guardians were the constant. No significant differences were found between JSOs with male and female guardians (β= −.145, t(866) = −1.431, p = ns). Second, considering that these mixed results may stem from multicollinearity between moderators in the full model, an additional regression analysis was conducted where gender of the primary caregiver was the only moderator included in the model. In this second regression, JSOs with female caregivers represented the constant. This regression was significant, F(7,827) = 6.10, p < .001, R2 Adj. = .04, and produced a significant simple effect for gender (β = −.209, t(827) = −.105, p < .05). Therefore, a tentative conclusion can be made that juvenile sexual offenders who are primarily cared for by men have worse quality relationships with their caregivers than do young sexual offenders who are primarily cared for by women. Furthermore, this effect seems to be unique to youth high in delinquency, as it is not present in the JC or JD-NV study participants.

Substitute caregivers

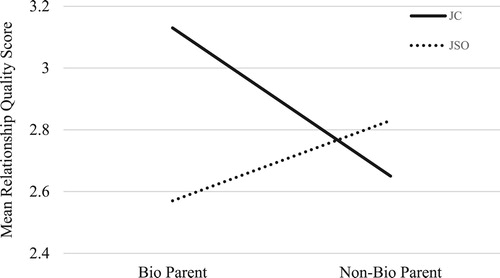

Hypothesis Three, which predicted that biological status would moderate the youth’s perceived relationship quality with their caregiver, was partially confirmed. Youth who indicated that their primary caregiver was not closely biologically related to them (i.e. step-parent, adoptive parent, foster parent, distant relative) were grouped together. Consistent with expectations, JCs who were raised by their biological parents had significantly higher relationship quality scores than did JCs who were raised in substitute care situations (β = −.298, t(866) = −1.758, p < .05). Further, no significant interactions were found for JD-NVs (β = 1.45, t(866) = .558, p = ns) or JD-Vs (β = .223, t(866) = .842, p = ns) with regard to the type of relationship with their caregiver.

However, a significant interaction effect was found for juvenile controls and the juvenile sexual offenders (β = .547, t(866) = 2.709, p < .01). This interaction revealed that, while relationship quality was lower for JCs with non-biological caregivers compared to JCs with biological caregivers, the opposite pattern was true for JSOs. Contrary to the hypothesis, juvenile sexual offenders had higher relationship quality scores when their caregivers were non-biological. Furthermore, when using JSOs as the reference group, a significant simple effect was obtained, confirming that JSOs with biological guardians had significantly lower relationship quality scores than did JSOs with substitute guardians (β = .274, t(866) = 2.532, p < .05).

As this interaction was in the opposite direction of the hypothesised effect, further investigation was necessary. Therefore, a separate moderated regression was conducted in which biological status was the only moderator entered into the model. The results were consistent with those of the full model, (F(7,827) = 6.65, p < .001, R2 Adj. = .04). Again, a significant interaction was found for JSO youth with biological and non-biological caregivers, such that youth with non-biological caregivers had higher relationship quality scores (β = .743, t(827) = 3.21, p < .01). Thus, having a non-biological caregiver may provide a buffering effect for relationship quality between juvenile sexual offender and their guardian (See ).

Discussion

This study was designed to investigate the unique effects of caregiver disruption on the development of juvenile sexual offending. It does so by analysing the relationship between offence type and the youths’ perceived relationship quality with their caregivers, while including the potentially moderating factors of caregiver gender and biological relationship between caregiver and child. In general, the data supports the hypotheses that offence status and caregiver disruption history are important factors to consider in evaluating the quality of the relationship between a youth and their primary guardian.

The relationship of sexually aggressive youth to their caregivers may prove to be a key to understanding their aberrant behaviour. The comparison of juvenile sexual offenders, violent and nonviolent juvenile delinquents, and young people who have never been convicted of criminal activity may offer insights into the impact that criminal offending has on the relationship quality between a youth and their primary caregiver. It is widely accepted that poor-quality parenting and strained parent–child relationships are associated with juvenile delinquency (Hoeve et al., Citation2009). The data from this study support the hypothesis that more serious offence statuses are related to low relationship quality scores. Both juvenile sexual offenders and violent juvenile delinquents reported poor quality relationships, with JSOs reporting slightly worse relationships than JD-Vs.

However, this study did not address the directionality of the relationship between offence status and caregiver quality scores. It has been suggested that youth with weak attachments are more likely to engage in violent or sexually delinquent acts (Felizzi, Citation2015b). Inadequate caregiving may also mean that these youths are poorly supervised and monitored, and thus are at increased risk for delinquency and sexual offending (Zankman & Bonomo, Citation2004). On the other hand, another feasible argument holds that committing a juvenile offence may, in and of itself, adversely impact the quality of the primary caregiver relationship. Research examining shame and stigma associated with parenting sexual offenders clearly documents that parents of juvenile sexual offenders struggle with accepting their child’s crime and have difficulties expressing love for their child after the offence (Jones, Citation2015). Thus, there is evidence that the low quality caregiver-child relationships seen in the two high-delinquency groups both influence and are influenced by offence status.

The initial finding described above is an important contribution to understanding the family dynamics of young offenders. However, it also elicits questions regarding the impact of distinct family systems. Examining nuance in the types of family disruptions that characterise juvenile sexual offenders’ households would make those discriminations even more useful. Therefore, two central moderators related to caregiver disruption have been selected for examination, caregiver gender and substitute caregivers.

Caregiver gender

The first of these moderators distinguishes the perceptions of relationship quality from youth with male or female caregivers. Overwhelmingly, the literature examining parental gender effects on children’s behaviour has found that children who are parented by males are at increased risk for a broad range of negative social and emotional outcomes (Coles, Citation2015). It was anticipated that youth with male primary caregivers would report lower quality relationships than would youth who were cared for by women.

Consistent with this hypothesis, the data shows that for certain youth, the presence of a male primary caregiver is associated with a decrease in relationship quality scores. For youth with low levels of delinquency (JC & JD-NV), no differences in relationship quality were found between those who had female or male caregivers. However, for the high-delinquency group (JD-V & JSO), significant interactions were found, such that high-delinquent youth with male primary caregivers had lower relationship quality scores than did high-delinquent youth with female primary caregivers.

One possible interpretation of this finding is that the men who parent the JC/JD-NV youth are involved, supportive, and reasonable caregivers. On the other hand, high-delinquency youth may be more likely to be parented by absent or hostile male caregivers. Attentive and sympathetic parenting might potentially affect both the relationship quality score and the youth’s type of offending. This conclusion is consistent with the body of literature which suggests that attentive and supportive caregiving is a protective factor against juvenile delinquency (Hoeve et al., Citation2009). Future research should more closely examine the parenting styles of these male primary caregivers. Analyses of this nature would add to the interpretability of this study’s finding.

Substitute caregivers

Just as youth have distinct reactions to male and female caregivers, they may react in measurably different ways to their biological parents or the substitute caregivers that raise them. Youths in biologically-intact families are thought to be at lower risk for child abuse and neglect, insecure attachment styles, and engagement in delinquency compared to their peers with substitute guardians (Hilton, Harris, & Rice, Citation2015; Miller et al., Citation2000).

In this study it was hypothesised that biological status would act as a moderator between offence type and relationship quality, with the presence of a substitute guardian negatively affecting the caregiver-child relationship. The results of this moderation analysis partially supported this hypothesis. As expected, having a non-biological caregiver resulted in lower relationship quality scores for JC, JD-NV, and JD-V youth. Thus, for the majority of youth in this sample, being raised by a biological parent can be considered a protective factor for maintaining a strong and high-quality bond, even while the child is incarcerated.

However, these data yielded surprising results for JSO youth whose reports were inconsistent with the proposed hypothesis. For youth who have committed sexual offences, relationship quality scores were lower if their primary caregiver was a biological parent. Since this difference was not seen in either of the other two incarcerated groups, it is reasonable to conclude that neither criminal offending in general, nor separation from one’s biological parents via the justice system, are the cause of this unusual finding. Instead, these results indicate something unique about young sexual offenders and their parents. One possible explanation is that society views sexual offenders, and by extension the parents of sexual offenders, with more stigma and disgust than they do other delinquent teens and families (Smith & Trepper, Citation1992). Parents of sexual offenders simultaneously deal with the internal self-blame for their child’s offence, the public shame and stigma of having a child convicted of a sex crime, and the exhaustion that comes with navigating the court and juvenile justice system. This may be overwhelming for JSO’s parents, causing their relationship with their child to suffer. It is also probable that the social stigma attached to sexual crimes may cause parents to demonstrate a loss of respect for the offending child. That loss, in turn, may further undermine the caregiver-child relationship.

While sexual crimes are more stigmatised than almost any other criminal offences (Tewksbury, Citation2012), stigmatisation is not the only unique aspect of this type of offending. Sexual offences also constitute a rare type of criminal offence that is almost as likely to occur within the household as outside of it, and as likely to include a family member as an extra-familial victim (Magalhães et al., Citation2009). Intra-family sexual abuse puts parents in an impossible position, given their emotional attachment to both the perpetrator and the victim. In some cases, parents themselves must even report one child’s sexual offence to the authorities in order to protect another family member. Within this sample of offenders, 48% of JSO youth reported that they lived in the same household as their victim. In the future, researchers should investigate the relationship quality between intra- and extra-familial offences to see if these results can be explained by victim type (i.e. intra- vs. extra-familial).

Study strengths

This study contributes to the existing literature in three important ways. First, it succeeds in clarifying crucial distinctions between juvenile sexual offenders and general juvenile delinquents, while also elucidating group commonalities. These results support the classification of juvenile sexual offenders as a population similar to those juvenile delinquents who commit violent crimes. Yet, it is essential to note that the sexual offenders in this study differed on almost all measures from the nonviolent incarcerated youth. It is evident then, that while juvenile sexual offenders and violent juvenile delinquents may emanate from a single population, these youth should not be considered the same as youth who commit minor offences, even if these youths are incarcerated together.

Even though this study suggests that youth who commit sexual offences are in many ways similar to youth who commit other crimes against persons, juvenile sexual offenders and violent juvenile delinquents were not identical on all measures. Two differences stand out: (1) A higher percentage of JSOs were found to have experienced disrupted caregiving than JD-Vs; and (2) the positive impact of non-biological caregivers was significant for JSOs but not JD-Vs. These findings indicate that the uniqueness of the juvenile sexual offender population needs to be investigated more fully and future findings need to be incorporated into the literature to enhance existing theories.

A second strength of this study is its inclusion of the juvenile control group. Among the few studies that have examined JSOs as a unique population, almost none of them have included a non-incarcerated control group. The results of this study indicate that this comparison may be particularly valuable, especially in light of the additional contrasts made with the other groups of incarcerated youth. Findings from this investigation demonstrate that JSOs have dramatically different home lives than do the average, non-criminal teens. Compared to control youth, JSOs were at greater risk for every type of caregiver disruption. This finding points to potential areas for the prevention of juvenile sexual offending by intervening with families on the brink of disrupting a child’s primary caregiving relationships. By maintaining children’s connection to a biological parent, they can extend the protective advantages of this type of parenting.

Finally, the measurement of variables related to caregiver disruption, in and of itself, represents one of this study’s strengths. To date, the literature examining family factors in the etiology of juvenile sexual offending has been sporadic and disjointed. This study offers a touchstone for important further research which may consider the construct of caregiver disruption as a whole. There is much more work to be done in this area, but the results of this study suggest that continuing research on this line of inquiry will be both informative and valuable.

Study limitations

Despite the strengths of this study, it is also not without its limitations. First, all of the data comes from self-report surveys. Those surveys touch upon a number of sensitive topics. The primary limitation is that some of the participants may not have answered the questions truthfully. Though the participants were assured of the anonymity of this data, incarcerated youth might well have felt that reporting on their poor relationships with their primary caregivers could have negative consequences for their therapy or release plans. While fewer than two percent of youth dropped out of the study, no follow-up information was collected from those youth who chose to end their participation. This means that an evaluation of their concerns regarding the study and a comparison of their demographic profile to youth who completed study measures is not possible. Thus, these findings must be evaluated with this caution in mind.

Second, as the data was collected while many of the youth were incarcerated, they were asked to report on their relationships with their primary caregivers during the last year that they were living in the community. This is particularly problematic insofar as youth who had been incarcerated for long sentences may well have more distorted memories about the quality of their relationships at that time. Furthermore, this assessment method creates a disparity between incarcerated youth and controls, since control youth were reporting on their current relationship with their caregivers, while those incarcerated responded retrospectively.

Third, the very idea of organising youth by the type of their latest offence is a dubious and an unstable system for categorisation. Many of these youth may have committed crimes previously that would have placed them in different categories. Some may go on to recidivate with a different type of criminal offence. Though this study did confirm that no youth in the control groups had previously been convicted of a sexual offence, it fails to take into account the potential fluidity of criminal activity by these young men over time.

Finally, the relationship quality scale used in this study presents a fourth limitation. The original researchers asked youth to identify a single primary caregiver. As such, it is possible that youth living in two-parent families may have had difficulty in choosing only one parent to rate. Further, we lack comparative data on the relative quality of the youth’s relationship between parents, as well as data which would allow for a comparison of two-parent households to single-parent households.

Treatment implications

Understanding risk and protective factors in family relationships has broad implications for encouraging and shaping family therapy for young sexual offenders. Since family dynamics are critical to the development and maintenance of appropriate sexual behaviour among at-risk youth (Yoder, Citation2014), services that are attuned to the particular risk factors present in a JSO’s family structure may be more effective at facilitating a positive home environment for the youth. This study suggests that service providers should be vigilant for youth who have experienced caregiver disruptions. In particular, youth who are being primarily cared for by men and those youth who have experienced substitute care seem to be at increased risk for relationship quality problems. Providers may consider encouraging households with these risk factors to engage in more extensive family therapy than they would otherwise.

On the other hand, previous research has also demonstrated that family dynamics may be a protective factor against sexual recidivism in youth (Spice, Viljoen, Latzman, Scalora, & Ullman, Citation2013). Though contrary to our hypothesis, this study finds that non-biological caregivers may be more accepting, understanding, and compassionate toward sexually delinquent youth. One may tentatively conclude from these results that living in a non-biological home may, in fact, be particularly beneficial for young sexual offenders, since it gives them a chance to develop relations with adults who have not been personally impacted by their assaultive behaviour. This result should certainly not be used to recommend that youth be removed from their biological homes in favour of foster or adoptive homes. However, it does suggest a potential for strengths-based approaches that may be used by therapists and other treatment practitioners to capitalise on the emotional distance that is present in non-biological living environments in a proactive therapeutic manner.

Future directions

This study’s findings lend themselves to a number of future directions for research on sexual offending and caregiver disruption. First, a more in-depth examination of the interconnectedness of caregiver disruption risk-factors is warranted. Though outside the scope of this study, information should be gathered regarding the impact on relationship quality of caregivers who represent two or more areas of disrupted caregiving (e.g. a step-father, who is both male and non-biological). Second, due to small cell sizes, some nuance was lost in the moderators in this study. For example, too few youth lived with a non-parental family member (e.g. custodial grandparents) for that type of family structure to be examined independently. It would be valuable for future researchers to seek samples of youth who have lived with a broader variety of caregivers (e.g. grandmothers, foster care) in order to gain a clearer picture of the ways in which a disruption can affect youth.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Apel, R., & Kaukinen, C. (2008). On the relationship between family structure and antisocial behavior: Parental cohabitation and blended households. Criminology; An Interdisciplinary Journal, 46, 35–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.2008.00107.x

- Borduin, C. M., Schaeffer, C. M., & Heiblum, N. (2009). A randomized clinical trial of multisystemic therapy with juvenile sexual offenders: Effects on youth social ecology and criminal activity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(1), 26–37. doi: 10.1037/a0013035

- Bowlby, J. (1944). Forty-four juvenile thieves: Their characters and home lives. International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 25, 19–52.

- Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss, Vol. I: Attachment. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Bowlby, J. (1982). Attachment and loss: Retrospect and prospect. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 52(4), 664–678. doi:10.1111/j.19390025.1982.tb01456.x doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1982.tb01456.x

- Breivik, K., & Olweus, D. (2006). Adolescent's adjustment in four post-divorce family structures: Single mother, stepfather, joint physical custody and single father families. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 44, 99–124. doi: 10.1300/J087v44n03_07

- Bronte-Tinkew, J., Scott, M. E., & Lilja, E. (2010). Single custodial fathers’ involvement and parenting: Implications for outcomes in emerging adulthood. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(5), 1107–1127. doi:10.1300/J087v44n03_07 doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00753.x

- Coles, R. L. (2015). Single-father families: A review of the literature. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 7, 144–166. doi: 10.1111/jftr.12069

- Duane, Y., Carr, A., Cherry, J., McGrath, K., & O'Shea, D. (2003). Profiles of the parents of adolescent CSA perpetrators attending a voluntary outpatient treatment programme in Ireland. Child Abuse Review, 12(1), 5–24. doi: 10.1002/car.776

- Evenhouse, E., & Reilly, S. (2004). A sibling study of stepchild well-being. Journal of Human Resources, 39(1), 248–276. doi: 10.2307/3559012

- Felizzi, M. V. (2015a). Family or caregiver instability, parental attachment, and the relationship to juvenile sex offending. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 24(6), 641–658. doi: 10.1080/10538712.2015.1057668

- Felizzi, M. V. (2015b). Emotional abuse, parent and caregiver instability, and disrupted attachment: The relationship to juvenile sexual offending. In K. Rice & M. V. Felizzi (Eds.), Global youth: Understanding challenges, identifying solutions, offering hope (pp. 5–16). Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Funari, S. K. (2005). An exploration of impediments to attachment in a juvenile offender population: Comparisons between juvenile sex offenders, juvenile violent offenders and juvenile non-sex, non-violent offenders (Doctoral dissertation). Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia.

- Greenfeld, L. A. (1997). Sex offences and offenders: An analysis of data on rape and sexual assault. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice.

- Henggeler, S. W., Letourneau, E. J., Chapman, J. E., Borduin, C. M., Schewe, P. A., & McCart, M. R. (2009). Mediators of change for multisystemic therapy with juvenile sexual offenders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(3), 451–462. doi: 10.1037/a0013971

- Hilton, N. Z., Harris, G. T., & Rice, M. E. (2015). The step-father effect in child abuse: Comparing discriminative parental solicitude and antisociality. Psychology of Violence, 5, 8–15. doi: 10.1037/a0035189

- Hoeve, M., Dubas, J. S., Eichelsheim, V. I., Van Der Laan, P. H., Smeenk, W., & Gerris, J. R. (2009). The relationship between parenting and delinquency: A meta-analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37, 749–775. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9310-8

- Jones, S. (2015). Parents of adolescents who have sexually offended: Providing support and coping with the experience. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 30, 1299–1321. doi: 10.1177/0886260514540325

- Juffer, F., & van Ijzendoorn, M. H. (2005). Behavior problems and mental health referrals of international adoptees: A meta-analysis. Jama, 293(20), 2501–2515. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.20.2501

- Kaufman, K. (2001). Perceived relationship with supervisor scale. Portland, OR: Portland State University.

- Keogh, T. (2012). The internal world of the juvenile sex offender: Through a glass darkly then face to face. London: Karnac Books.

- Lyn, T. S., & Burton, D. L. (2005). Attachment, anger and anxiety of male sexual offenders. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 11, 127–137. doi: 10.1080/13552600500063682

- Magalhães, T., Taveira, F., Jardim, P., Santos, L., Matos, E., & Santos, A. (2009). Sexual abuse of children. A comparative study of intra and extra-familial cases. Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine, 16, 455–459. doi: 10.1016/j.jflm.2009.05.007

- Margari, F., Lecce, P. A., Craig, F., Lafortezza, E., Lisi, A., Pinto, F., … Grattagliano, I. (2015). Juvenile sex offenders: Personality profile, coping styles and parental care. Psychiatry Research, 229(1), 82–88. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.07.066

- Marsa, F., O'Reilly, G., Carr, A., Murphy, P., O'Sullivan, M., Cotter, A., & Hevey, D. (2004). Attachment styles and psychological profiles of child sex offenders in Ireland. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 19, 228–251. doi: 10.1177/0886260503260328

- Marshall, W. L. (1989). Intimacy, loneliness, and sexual offenders. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 27, 491–504. doi:10.1177/088626097012003001 doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(89)90083-1

- Mathe, S. (2007). Juvenile sexual offenders: We are the sons of our fathers. Agenda (Durban, South Africa), 21(74), 133–140. doi: 10.1080/10130950.2007.9674887

- Miller, B. C., Fan, X., Christensen, M., Grotevant, H. D., & Van Dulmen, M. (2000). Comparisons of adopted and nonadopted adolescents in a large, nationally representative sample. Child Development, 71(5), 1458–1473. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00239

- Patterson, C. (2008). Child development. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- Rich, P. (2006). Attachment and sexual offending: Understanding and applying attachment theory to the treatment of juvenile sexual offenders. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- Righthand, S., & Welch, C. (2004). Characteristics of youth who sexually offend. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 13, 15–32. doi: 10.1300/J070v13n03_02

- Ryan, G., Leversee, T. F., & Lane, S. (2011). Juvenile sexual offending: Causes, consequences, and correction. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- Santrock, J. W. (2013). Children. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- Seidman, B., Marshall, W. L., Hudson, S. M., & Robertson, P. J. (1994). An examination of intimacy and loneliness in sex offenders. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 9, 518–534. doi: 10.1177/088626094009004006

- Seto, M. C., & Lalumière, M. (2010). What is so special about male adolescent sexual offending? A review and test of explanations through meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 136, 526–575. doi: 10.1037/a0019700

- Sigre-Leirós, V., Carvalho, J., & Nobre, P. J. (2016). Early parenting styles and sexual offending behavior: A comparative study. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 46, 103–109. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2016.02.042

- Smallbone, S. (2006). Social and psychological factors in the development of delinquency and sexual deviance. In H. E. Barbaree & W. L. Marshall (Eds.), The juvenile sex offender (2nd ed., pp. 105–127). New York, NY: Guildford Press.

- Smallbone, S. W., & Dadds, M. R. (1998). Childhood attachment and adult attachment in incarcerated adult male sex offenders. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 13, 555–573. doi: 10.1177/088626098013005001

- Smallbone, S. W., & Dadds, M. R. (2001). Further evidence for a relationship between attachment insecurity and coercive sexual behavior in nonoffenders. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 16, 22–35. doi: 10.1177/088626001016001002

- Smith, B. J., & Trepper, T. S. (1992). Parents’ experience when their sons sexually offend: A qualitative analysis. Journal of Sex Education and Therapy, 18, 93–103. doi: 10.1080/01614576.1992.11074043

- Spice, A., Viljoen, J. L., Latzman, N. E., Scalora, M. J., & Ullman, D. (2013). Risk and protective factors for recidivism among juveniles who have offended sexually. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 25, 347–369. doi: 10.1177/1079063212459086

- Starzyk, K. B., & Marshall, W. L. (2003). Childhood family and personological risk factors for sexual offending. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 8(1), 93–105. doi: 10.1016/S1359-1789(01)00053-2

- Tewksbury, R. (2012). Stigmatization of sex offenders. Deviant Behavior, 33(8), 606–623. doi: 10.1080/01639625.2011.636690

- Tidefors, I., & Strand, J. (2012). Life history interviews with 11 boys diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder who had sexually offended: A sad storyline. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 13(4), 421–434. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2011.652344

- Ward, T., Hudson, S. M., & Marshall, W. L. (1996). Attachment style in sex offenders: A preliminary study. Journal of Sex Research, 33, 17–26. doi: 10.1080/00224499609551811

- Whitaker, D. J., Le, B., Hanson, R. K., Baker, C. K., McMahon, P. M., Ryan, G., … Rice, D. D. (2008). Risk factors for the perpetration of child sexual abuse: A review and meta-analysis. Child Abuse & Neglect, 32, 529–548. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.08.005

- Wilkinson, G. S. (1993). The Wide Range Achievement Test administration manual. Wilmington, DE: Wide Range.

- Worley, K., Church, J., & Clemmons, J. (2012). Parents of adolescents who have committed sexual offences: Characteristics, challenges, and interventions. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 17(3), 433–448. doi: 10.1177/1359104511417787

- Yoder, J. R. (2014). Service approaches for youths who commit sexual crimes: A call for family-oriented models. Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work, 11(4), 360–372. doi: 10.1080/10911359.2014.897108

- Yoder, J. R., Dillard, R., & Stehlik, L. (2018). Disparate reports of stress and family relations between youth who commit sexual crimes and their caregivers. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 24(1), 114–124. doi: 10.1080/13552600.2017.1372938

- Yoder, J. R., Leibowitz, G. S., & Peterson, L. (2016). Parental and peer attachment characteristics: Differentiating between youth sexual and non-sexual offenders and associations with sexual offence profiles. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 33, 2643–2663. doi: 10.1177/0886260516628805

- Zankman, S., & Bonomo, J. (2004). Working with parents to reduce juvenile sex offender recidivism. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 13, 139–156. doi: 10.1300/J070v13n03_08