ABSTRACT

Preventing child sexual abuse (CSA) requires comprehensive multi-agency criminal justice and public health approaches. Yet, marginal attention has been given to secondary prevention strategies that target “at risk” populations. Thus, we carried out a scoping review examining secondary prevention interventions for people at risk of sexual offending by considering their effectiveness, challenges and barriers. We identified N = 43 sources and completed a qualitative analysis. Our appraisal found five themes: (a) essential features needed for secondary prevention programmes (plus summary of interventions); (b) barriers to examining, implementing and accessing secondary prevention programmes; (c) methodological limitations; (d) the ethical justification; and (e) economic benefits for preventing abuse before it occurs. Over the last two decades, sources report greater public tolerance to the notion of tackling CSA using public health prevention approaches. Thus, we call for policy makers to embrace this positive shift and invest resources to further examine this area.

Practice impact statement

Advancing clinicians’ and therapists’ practice is critical for those working with people at risk of harm. This review aims to strengthen current knowledge and inform practice. Further, policy makers and funders are essential to the development and progression of prevention strategies; by providing this contemporary review, we hope to assist the decision-making process for allocating resources and strengthening confidence in advancing policy that builds comprehensive prevention approaches.

Introduction

The consequences of CSA are far-reaching (Dube et al., Citation2005) with rates estimated at 1 in 4 (girls) and 1 in 13 (boys) (Pereda et al., Citation2009). The World Health Organisation (WHO, Citation2016) reports harms to children across the life course, including increasing rates of mental health conditions (Asante & Andoh-Arthur, Citation2015; Mandelli et al., Citation2015); sexual and reproductive problems (Bertone-Johnson et al., Citation2014); communicable diseases (Norman et al., Citation2012); harmful risky sexual behaviours (Homma et al., Citation2012); and drug and alcohol use (McCarthy-Jones & McCarthy-Jones, Citation2014; Yuan et al., Citation2014). Social and behavioural problems include poor attachment (Tardif-Williams et al., Citation2017); emotional dis-function (Lanier et al., Citation2015); sex work (Norman et al., Citation2012); poor quality of life (Weber et al., Citation2016); cognitive impairment, poor language functioning (Kavanaugh et al., Citation2015); academic performance (Lanier et al., Citation2015); and economic problems including a greater risk of gambling (Zhu et al., Citation2015), unemployment (Barrett et al., Citation2014), welfare dependency (Horan & Widom, Citation2015) and housing instability (Lake et al., Citation2015). Children who experience CSA are most at risk from injury, death and disease (WHO, Citation2010) thus, carry the greatest burden. Understanding how to prevent CSA is of significant concern (WHO, Citation2016).

CSA is complex, not one single factor explains the phenomenon (Ward & Beech, Citation2016). Instead, like all behaviours, CSA exists within a socioecological structure (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1977) whereupon at least four levels or contexts interact to inform human behaviour. These include the individual, interpersonal, community and societal level. Individual-level factors known to influence people to commit CSA include emotional dysregulation (Gillespie & Beech, Citation2016); sexual motivation (Seto, Citation2019); distorted thinking (Ó Ciardha & Ward, Citation2013); mental disorders (Serin et al., Citation2001); childhood experiences of abuse (Jespersen et al., Citation2009); poor attachments (Smallbone & McCabe, Citation2003); and genetic predisposition (Quinsey & Lalumière, Citation1995). Interpersonal level factors include inadequate adult relationships, intimacy deficits (Marshall, Citation2010); loneliness (Schulz et al., Citation2017); witnessing a fathers’ sexual or domestic abuse (Sitney & Kaufman, Citation2020); being exposed to a sexually inappropriate family environment and use of pornography/deviant sexual fantasy during childhood (Beauregard et al., Citation2004). Community-level factors include anti-social peers (Jordaan & Hesselink, Citation2018) and social isolation (Miner et al., Citation2016). Societal level factors include patriarchal cultures (Purvis & Ward, Citation2006); the normalisation of pornography (Foubert et al., Citation2019); online sexualised cultures (Moore & Reynolds, Citation2018); and economic cultures (Gannon et al., Citation2010; Wojcik & Fisher, Citation2019) such as child trafficking and exploitation (Lee, Citation2017). Given that risk is found at each socioecological level, comprehensive strategies to prevent CSA are needed.

Public health approaches focus on the health, safety and well-being of whole populations. They draw on the expertise and knowledge of multiple disciplines such as medicine, education, psychology, economics and sociology. When tackling problems such as CSA multi-component public health models are recognised as appropriate means of preventing CSA as they target each socioecological level in an inclusive and comprehensive manner. CSA public health prevention strategies are usually categorised and explained on three levels: primary, secondary and tertiary (McMahon, Citation2000) but current Western approaches tend to adopt primary or tertiary approaches to prevention (McCartan, Merdian, et al., Citation2018). Primary prevention aims to prevent violence occurring in the first place by targeting universal and general populations. CSA interventions target potential victims and their caregivers, helping them recognise signs of abuse, how to respond and report it. Such approaches, however, place responsibility on children to recognise and understand CSA and have the capacity to resist and report would be abusers. Yet, little is known if such approaches prevent CSA (Finkelhor, Citation2009), indeed, our knowledge of primary prevention remains under-developed, and a greater examination of the utility and effectiveness of this approach is needed. More is understood of tertiary approaches, that adopt strategies with people already known to criminal justice or health care systems. However, prevention activities using this approach centre on the prevention of the re-occurrence of CSA, rather than preventing abuse in the first place. This is not to say that efforts should not be made to help prevent sexual re-offending, indeed they should, but low recidivism rates of between 10.1% and 13.7% (treated vs. untreated respectfully) in adult males (Schmucker & Lösel, Citation2017) demonstrate that the management of those known to the justice system is mostly effective. That is, once a person has been convicted, most appear to stop sexual offending.

Secondary approaches target groups or individuals who present specific risks or characteristics that might place them at increased risk of victimising others or being vulnerable to victimisation themselves. Surprisingly, little is known of the effectiveness of secondary prevention approaches, in particular those that target people at risk of perpetrating CSA. Given that most sexual assault arrests (over 95%) are perpetrated by a person not known to the criminal justice system (Sandler et al., Citation2008), this is an important population to target. It is worth noting a distinction here between, detected, and undetected first-time offences. While the majority of those arrested for CSA are officially recorded as first-time offenders (Sandler et al., Citation2008), this in reality only means their crime(s) have been detected for the first time. In most cases of CSA, the point of arrest or detection does not represent the onset or actual prevalence of CSA (Bentley et al., Citation2020). For instance, in familial CSA, offending can remain undetected for long periods of time, as such the point of arrest, does not genuinely reflect the rate of offending. Given that those already in the system are at low risk of reoffending (Schmucker & Lösel, Citation2017), targeting people not known to the criminal justice system but at risk of perpetrating CSA, would alleviate the devastating consequences suffered by victims and their families, and the significant economic burden to society in responding to the needs of victims, and the management of people convicted of sexual offending (Letourneau et al., Citation2018; Saied-Tessier, Citation2014).

In recent years, an increased interest in CSA secondary public health approaches is observed in countries such as England, Ireland, The Netherlands, Belgium, Canada, The United States, New Zealand, Australia and Germany, sparking some movement in this field. Research has explored professionals’ perspectives of people at risk of CSA (Parr & Pearson, Citation2019); self-management strategies for at-risk individuals (Merdian et al., Citation2017); and focus on specific interventions for people at risk of engaging in CSA (Knack et al., Citation2019). This work, however, remains in its infancy, particularly when compared to what is known of primary and tertiary prevention. A lack of funding, knowledge, methodological restrictions and ethical hurdles (McCartan, Hoggett, et al., Citation2018) means that evidencing and promoting the efficacy of secondary prevention is an arduous task.

With the principle of “leaving no one behind” and the impetus to eliminate violence against children by 2030 (CoE, Citation2017; UN, Citation2015) strategies that target people at risk of perpetrating CSA and preventing actual first-time offences are likely to assist this goal. Thus, secondary public health prevention approaches targeting people at risk of engaging in CSA must be a priority to policy makers, researchers and clinicians alike. Our scoping review aims to consolidate current knowledge by exploring the nature and scope of secondary prevention interventions, specifically, those aimed at adults and children at risk of perpetrating harm against children (including online and contact behaviours). We aim to understand what prevention interventions are currently being delivered, how effective these are, and what challenges and barriers, researchers, practitioners and users of these interventions face.

Method

Protocol and registration

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis Protocols Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-SCR) was used to develop a protocol to guide the review (Tricco et al., Citation2018). PROSPERO (the international prospective register for systematic reviews) currently do not accept the registration of scoping reviews (PROSPERO, Citationn.d.). To administer the protocol, we applied Arksey and O’Malley’s (Citation2005) five-stage framework for conducting scoping reviews.

Eligibility criteria

To be included in the review, sources were required to examine and/or discuss prevention interventions that target adults and/or minors, males and/or females at risk of committing CSA. There were no restrictions placed on the intervention type, indeed, all interventions were in scope e.g. educational, psychological, situational, one-to-one/group, online, telephone, face-to-face. Likewise, there were no limitations on the outcomes measured, however, measures were expected to include some discussion on CSA prevention, and/or secondary outcomes such as helping people at risk of committing sexual abuse (this might vary across intervention, but examples could have included education/awareness-raising, therapy, general support, pharmacological treatment). All study types were included e.g. experimental, observational, quantitative, qualitative and/or mixed methods studies. Studies were included regardless of the use of a comparison or control group. The review scrutinised and considered sources that reported on any follow-up period and indeed any method of reporting outcomes, e.g. official reports, self-report, observations. Published and unpublished (grey literature) were included in the search, including peer-reviewed journal articles, organisational reports, governmental reports, book chapters and thesis published between January 2000 and February 2021. Sources which provided descriptive information were also included. Exclusion criteria centred on the reporting of primary, tertiary and victim interventions, inaccessible full records, and those not in the English language.

Information sources

To identify potentially relevant sources, the following databases were searched, between the years January 2000 and February 2021: Web of Science; EBSCO MEDLINE; CINAHL; PubMed; and PsycINFO. In addition, hand-sifting through reference lists and using existing networks, relevant organisations and conferences (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005) was also undertaken. Final database searches were conducted on 13th March 2021.

Search

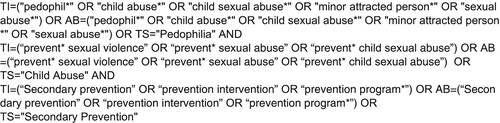

The three-step method for systematic reviews was used (Aromataris & Riitano, Citation2014), (1) An initial search of relevant databases followed by a text words analysis of title, abstract and index words; (2) A search of identified keywords and index terms across all databases; and (3) A search through reference list of all identified reports and articles. An example of the search strategy of Web of Science database is provided in .

Selection of sources of evidence

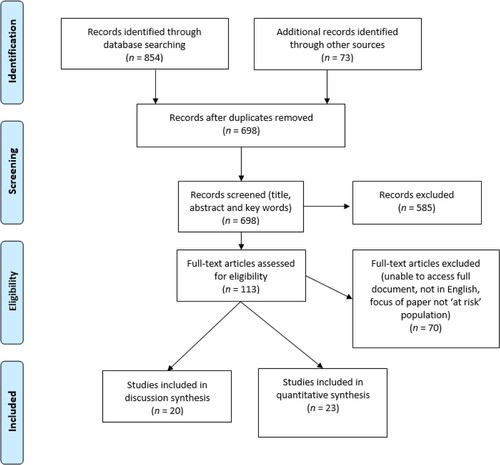

Following identification of sources, the selection process consisted of application of the criteria to the title and abstract by the first author, if selection criteria remained uncertain, the full article was accessed, read and a decision made. This was checked by the second and third authors. Once all articles were accessed, they were read through in full to reach a decision on inclusion by all three authors. The number of sources selected and rejected at each stage is detailed in (Moher et al., Citation2009).

Data extraction

Key characteristics and variables were agreed at the protocol design stage. These were saved to an Excel spreadsheet. This was reviewed and amended after initial searches to ensure all key characteristics were captured in the review. Authors one and two extrapolated the data into an Excel spread sheet, discrepancies were discussed between authors. Author three checked and reviewed data.

Data items

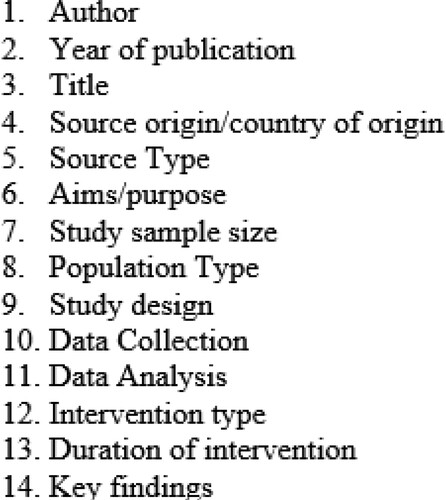

Key characteristics and variables included general variables, as well as more specific areas of interest to our research question, these are detailed in .

Data analysis of individual sources of evidence

Individual sources included in this review were qualitatively appraised and organised thematically. Data were analysed using the six steps of Thematic Analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006): (1) Familiarisation required reading and re-reading of each source, the data charting process was useful for familiarisation, (2) features within the sources were then coded, codes included concepts such as “mandatory reporting” “features of successful interventions” “barriers”, (3) next codes were clustered together, developing a thematic map of the prevalent codes/clusters across sources, (4) themes were reviewed and edited for both fit and essence across the sample, (5) themes and sub-themes were defined and labelled in preparation for the final stage (6) in which themes were written up providing a narrative account of the themes across the sample. Each of the five themes is presented in the discussion below.

Results

We set out to explore the nature and scope of secondary prevention interventions, specifically, those aimed at people at risk of perpetrating sexual abuse against children. Our research question asked what prevention interventions are currently being delivered, how effective are they, and what challenges and barriers exist. Our review includes a blend of discussion and empirical sources; we present two tables summarising these. includes discussion or review papers (n = 20) and details empirical studies (n = 23).

Table 1. Summary of discussion sources.

Table 2. Summary of empirical sources.

Now, we present a thematic synthesis of these sources in which five themes were developed.

Theme one: current secondary prevention programmes that target people at risk of sexual harm

Most sources in this study summarise or provide examples of existing secondary prevention programmes targeting people at risk of CSA. To avoid a lengthy narrative of individual programmes, we provide a summary of each intervention in . Where available we also include a weblink to the organisation delivering the intervention.

Table 3. Summary of global secondary prevention interventions.

Essential features of secondary programmes targeting people at risk of perpetrating CSA

Some of the key features noted by sources as vital for delivering secondary prevention interventions include those that deliver individualised strategies of care, are provided in a multi-disciplinary context, and administered using multi-modal approaches (Beech & Harkins, Citation2012; Beier et al., Citation2015; Bolen, Citation2003; Engel et al., Citation2018; Finkelhor, Citation2009; Heasman & Foreman, Citation2019; Knack et al., Citation2019; Konrad et al., Citation2017; Lasher & Stinson, Citation2017; Levine & Dandamudi, Citation2016; McKibbin et al., Citation2019; Citation2017; McKibbin & Humphreys, Citation2020; McMahon, Citation2000; Oliver, Citation2007; Ruzicka et al., Citation2021; Saleh & Berlin, Citation2003; Seto, Citation2009; Silovsky et al., Citation2019; Tabachnick, Citation2013). Programmes should provide opportunities for people, particularly young people (Shields et al., Citation2020) to develop or learn new skills (e.g. problem solving, emotional regulation, coping with sexual thoughts or behaviours, relationship/parenting skills) or alternative strategies to avoid harmful sexual behaviours or interests (Apsche et al., Citation2006; Beech & Harkins, Citation2012; Beier et al., Citation2015; Beier et al., Citation2016; Bentovim, Citation2002; Bolen, Citation2003; Carpentier et al., Citation2006; Heasman & Foreman, Citation2019; Jennings et al., Citation2013; Knack et al., Citation2019; Konrad et al., Citation2017; Lasher & Stinson, Citation2017; Letourneau et al., Citation2017; Levine & Dandamudi, Citation2016; McKibbin & Humphreys, Citation2020; McKillop, Citation2019; McMahon, Citation2000; Oliver, Citation2007; Seto, Citation2009; Silovsky et al., Citation2019; Tabachnick, Citation2013). Prevention interventions should recognise that for many people their own experiences of CSA are likely to be untreated, and as such, a provision of trauma-informed care is equally essential (Bentovim, Citation2002; Bolen, Citation2003; Jennings et al., Citation2013; Knack et al., Citation2019; McKibbin et al., Citation2019; McKibbin & Humphreys, Citation2020; Oliver, Citation2007; Seto, Citation2009; Silovsky et al., Citation2019). Programmes should provide pharmacological and/or psychopharmacological options for adults at risk of engaging in CSA, however, such treatment ought to complement therapy and not be provided in isolation (Beech & Harkins, Citation2012; Beier et al., Citation2015; Knack et al., Citation2019; Konrad et al., Citation2017; Landgren et al., Citation2020; Levine & Dandamudi, Citation2016; Saleh & Berlin, Citation2003; Seto, Citation2009). Programmes must ensure confidentiality/anonymity (Heasman & Foreman, Citation2019; Knack et al., Citation2019; Levine & Dandamudi, Citation2016); assist with disclosure (Bentovim, Citation2002; Knack et al., Citation2019; Konrad et al., Citation2017; McKillop, Citation2019) and where safe to do so (particularly for young people), include a family centred approach, that helps repair attachments with others (Bentovim, Citation2002; Konrad et al., Citation2017; McKibbin et al., Citation2017; McKibbin & Humphreys, Citation2020; McKillop, Citation2019; Shields et al., Citation2020; Silovsky et al., Citation2019).

Programmes should have a future-focused philosophy, one that helps build healthy sexual identities, promote healthy relationship patterns and narratives about masculinity and femininity and challenge socially constructed norms around traditional patriarchal male and female roles (Bentovim, Citation2002; Bolen, Citation2003; Jennings et al., Citation2013; Letourneau et al., Citation2017; Levine & Dandamudi, Citation2016; McKibbin et al., Citation2019; McKillop, Citation2019; McMahon, Citation2000; Oliver, Citation2007; Ruzicka et al., Citation2021; Tabachnick, Citation2013). Likewise, other social problems compounding the person’s life must be supported (e.g. addiction; unemployment; housing) to enable adaptive functioning (Heasman & Foreman, Citation2019; Knack et al., Citation2019; Lasher & Stinson, Citation2017; Levine & Dandamudi, Citation2016; McKibbin et al., Citation2019; McKibbin & Humphreys, Citation2020; McKillop, Citation2019). Finally, all secondary interventions ought to engender hope. They should reduce the shame and stigma associated with risk factors linked to CSA (Bentovim, Citation2002; Heasman & Foreman, Citation2019; Jennings et al., Citation2013; Knack et al., Citation2019; Lasher & Stinson, Citation2017; McKibbin et al., Citation2019; McKibbin & Humphreys, Citation2020) by building individual psychosocial capacity and opportunities that help meet individual needs and fostering a fulfilling and meaningful life that is free from harm.

Theme two: barriers to secondary prevention programmes that target people at risk of perpetrating sexual harm against children

Mandatory reporting laws limit the provision of help

One of the considerable barriers preventing the effective development and implementation of secondary prevention programmes, are mandatory reporting laws across most countries in Europe, the US, Canada and Australasia (Beier et al., Citation2015; Levenson & Grady, Citation2019b). While paradoxically these are aimed at protecting children, their very nature prevents people at risk of engaging in CSA reaching out and seeking treatment (Assini-Meytin et al., Citation2020; Lasher & Stinson, Citation2017; Mitchell & Galupo, Citation2018). Although some slight variance across jurisdictions, legislation makes it a requirement for health professionals to report any reasonable suspicion that a child has, or is, at risk of being abused. In some US States, the privilege between a solicitor and a client is greater than between a health professional and patient, the exception being if an intention to harm is clear, serious and imminent (Heasman & Foreman, Citation2019). Thus, the issue for health professionals working with people at risk of perpetrating CSA is often around the boundaries of intent and imminence. Without greater flexibility, health professionals are bound, by law, to report such suspicion, which unintentionally creates barriers (including fear of a break in confidentiality, legal consequences and shame) for people seeking help (Assini-Meytin et al., Citation2020; Beier et al., Citation2016; Finkelhor, Citation2009; Lasher & Stinson, Citation2017; Van Horn et al., Citation2015).

The impact of such legislation not only prevents people accessing help but is likely to reinforce the stigma associated with people at risk of perpetrating CSA, as it promotes the notion that where risk factors exist, abuse is inevitable and that all people ought to be dealt with through criminal justice proceedings. Sources report how stigma, in fact hinders the development of therapeutic relationships between clients and health professionals (Levenson & Grady, Citation2019b). Therapeutic relationships ought to build trust, enable meaningful exploration of the needs and risks a client presents, and support them to develop skills and strategies to help cope and live safely. While secondary prevention providers attempt to effectively work within current legislation by informing clients of their duties and boundaries around disclosure (Knack et al., Citation2019) this constraint prevents many people concerned about their sexual behaviour from reaching out for help in the first place (Wilpert & Janssen, Citation2020). Legislation in Germany, unlike many jurisdictions has less restrictive reporting laws (Heasman & Foreman, Citation2019). Mental health professionals are required to report concerns regarding the safety of a child, but only in cases where a child is at risk of imminent danger or death (Lasher & Stinson, Citation2017). It is believed these laws have played a key role in the success of Germany’s Prevention Project Dunkelfeld programme, as people are free to access help and treatment, without the threat of legal penalties (Assini-Meytin et al., Citation2020).

The pervading taboo and sensitive nature of CSA

All included records report the challenging and complex nature of CSA. Historically a perception exists in which sexual violence is perceived as binary, adults are viewed as perpetrators and children only as victims (McKibbin & Humphreys, Citation2020); viewing CSA through a binary and reductive lens is problematic as evidence shows, children themselves can exhibit harmful sexual behaviours against other children (Letourneau et al., Citation2017). Likewise, rates of CSA experiences in populations of people convicted of sexual offending are reported to be disproportionate to that of the general population. Thus, binary conceptualisations of CSA are likely to hinder the development of comprehensive strategies. As awareness of the nature and scale of CSA began to surface during the 1970s and 1980s, arguably the reactionary response to the “crisis” was to target interventions at those at risk of victimisation i.e. children (Bolen, Citation2003). Policymakers set out to educate or warn children of the dangers of CSA and help them develop skills to protect themselves by avoiding situations or to disclose should CSA occur. However, Bolen argues the assumption that CSA prevention programmes that target potential victims will reduce the prevalence of abuse, is flawed. Instead, relying on children to identify perpetrators and an overreliance on tertiary responses provides only limited protection after CSA has occurred (Assini-Meytin et al., Citation2020; McKibbin & Humphreys, Citation2020).

The taboo nature of CSA further serves to increase the stigma and fear associated with people at risk of causing harm, preventing them from reaching out for help (Grant et al., Citation2019; Knack et al., Citation2019; Levenson & Grady, Citation2019b; Piché et al., Citation2018; Van Horn et al., Citation2015; Wilpert & Janssen, Citation2020). Healthcare professionals can help reduce this stigma and fear; however, they too require education and support to understand the needs of this group (Heasman & Foreman, Citation2019; Levenson & Grady, Citation2019a). Lasher and Stinson (Citation2017) note negative and hostile experiences when seeking help from healthcare professionals, work colleagues/employers, family and friends. However, training and knowledge workshops can help improve reduce negative attitudes (Levenson & Grady, Citation2019a).

Social and political climate has been a hostile one – but interest in prevention is beginning to shift

Prevention strategies that target people at risk of perpetrating CSA have historically been notoriously difficult to reach policy-level support. The political and social climate across most countries has been hostile to working with people at risk of CSA, despite evidence suggesting this approach would support a comprehensive and coordinated approach to preventing sexual violence (Lasher & Stinson, Citation2017; McKillop, Citation2019). However, encouraging signs are noted by prevention academics and advocates who report a growing interest in secondary prevention for people at risk of perpetrating CSA (McKibbin & Humphreys, Citation2020). One of the reasons for this change is likely a result of heightened public awareness of systemic, historical and institutional CSA across the globe, as found by several national inquiries (Wright et al., Citation2020). Recent ongoing inquiries include the Australian Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse (Citation2017); the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse in England and Wales (Citation2016); The Scottish Child Abuse Inquiry (2018); and the Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care in New Zealand (Citation2020). Given the heightened public, media and political awareness of the scale and nature of sexual abuse, a more tolerant landscape in which secondary prevention strategies might be considered is in sight (Assini-Meytin et al., Citation2020; McKibbin & Humphreys, Citation2020; Tabachnick, Citation2013).

Theme three: methodological limitations

Comprehensive empirical evidence is needed to inform key risk and protective factors to identify which population/individuals are at risk

When considering secondary prevention public health approaches to tackle CSA, initiatives require a clear understanding of which populations are appropriate to target (McKillop, Citation2019). Central to secondary prevention is to target people at risk of committing a sexual offence before they do so. Much has been learned in regard to the motivations, behaviours and situations in which people sexually offend through the extensive study of convicted populations. While there is utility in drawing from this knowledge pool, particularly around our understanding of sexual interests, secondary prevention strategies should not be devised solely on this evidence. A more comprehensive understanding of the risk and needs of those who have not sexually offended is needed to bolster current theory. In saying this much is already understood about this population and the sources examined in this study suggest several populations appropriate for secondary prevention. Drawing on the work of Finkelhor, Bentovim (Citation2002) notes the value in providing prevention work with young people who have themselves been victims of sexual abuse. While sexual victimisation does not predict sexual perpetration, rates of sexual victimisation in those who offend are notable (Bentovim, Citation2002; Oliver, Citation2007), thus, the type and timing of trauma-informed interventions is crucial, both in terms of supporting the recovery of the young person’s victimisation as well as the prevention of future CSA.

McMahon (Citation2000), also identifies young males who have experienced sexual violence as a key risk factor. In addition, she includes young men with experiences of hostile family environments, witnesses of violence or abuse, and those engaging in high-risk sexual behaviours. Additional factors drawn from sexual offending literature include sexual exposure and arousal to deviant stimuli, beliefs that support abuse, a lack of empathy, hostility towards women and developmental problems. Bolen (Citation2003) identifies all young males as an appropriate target for secondary prevention work, but as noted by Finkelhor, a more suitable focus are stepfathers and boys who have been sexually abused. Of concern is the risk that this already vulnerable group could be exposed to further stigmatisation and shaming, thus, the support and help offered to help prevent future abuse must be administered with great care and sensitivity (Bentovim, Citation2002).

Sexual offending is of course complex and multifaceted, people with criminal histories are heterogeneous, indeed, Levine and Dandamudi (Citation2016) note there is not one clear profile of who is, or is not, at risk. However, they note some general classifications that could be used to target secondary interventions including being male; having access to children; aged between 14 and 30; have diagnosed or recognised themselves as a person with paedophilia; have additional paraphilic interests; have a personal family history of abuse; have issues coping with psychosocial stress; and use child abuse images. They also indicate some socioeconomic factors might be relevant, such as socioeconomic status and social isolation.

To appropriately inform the development of secondary prevention programmes, an understanding of risk and need must be drawn from evidence generated by high-quality and rigorous research studies. Although, increasing interest and research in this field is observed, there remains an over-reliance on our knowledge of risks and needs from forensic populations already convicted of sexual offending (Assini-Meytin et al., Citation2020; Beech & Harkins, Citation2012; Beier et al., Citation2015; Bolen, Citation2003; Engel et al., Citation2018; Oliver, Citation2007; Schaefer et al., Citation2010; Seto, Citation2009). While it is likely many risk factors are transferable to those at risk of perpetrating CSA, this assumption is not fully tested, and it is as likely many unknown differences also exist.

Interventions are in their infancy with many not yet tested under rigorous “gold standard” testing such as RCTs

It is encouraging to report a worldwide interest, development and implementation of secondary prevention programmes helping prevent people from perpetrating CSA in the first place. Unlike tertiary programmes, where an abundance of meta-analysis evaluation exists and continues to be tested; secondary prevention programmes are far less rigorously examined (McMahon, Citation2000). This is in part due to the embryonic nature of these interventions (Beier et al., Citation2015) and ethical challenges when designing random control trials (Engel et al., Citation2018; Schaefer et al., Citation2010; Silovsky et al., Citation2019). Yet, understanding what effective treatment or interventions look like for people at risk of perpetrating CSA is vital in the development of building a comprehensive response to preventing sexual violence (Apsche et al., Citation2005; Assini-Meytin et al., Citation2020; Bentovim, Citation2002; Bolen, Citation2003; Carpentier et al., Citation2006; Knack et al., Citation2019; McKibbin & Humphreys, Citation2020; McKillop, Citation2019; Seto, Citation2009).

Theme four: working with people at risk of engaging in sexual abuse, while ethically justified, conflicts with community protection norms

An ethical case is made across several sources in this review, they state that working with people at risk of CSA, prior to offending is the moral and right thing to do (Heasman & Foreman, Citation2019; Knack et al., Citation2019; Levenson & Grady, Citation2019b; Silovsky et al., Citation2019). Human dignity is a universal concept, and as such, the right to equal access to services (irrespective of what that service supports) is bestowed on all. Thus, among other things, people ought to have the right to access health care and services and have these rights protected. It is reported however, that society’s norms, conflict with this notion, indeed, people at risk of engaging in CSA or have a sexual attraction to children are perceived a threat and, therefore, not entitled to the same privileges as others in the community. This unintelligible norm extends to people who have never acted on their sexual interest and as a result is embedded across community protection approaches and legislation in the form of preventative sentencing (McCartan, Merdian, et al., Citation2018).

As a result of this ethical conflict, people with sexual interests in children are branded less valuable or worthy than others. Indeed, they are perceived a serious threat to the well-being of society and thus, disqualified from pursuing the same life goals as other members in the community. Yet, people with a sexual attraction to children, even those who have never offended, tend to have extensive health and social care needs, often with histories of untreated trauma (Bentovim, Citation2002; Jennings et al., Citation2013; Levine & Dandamudi, Citation2016; McKibbin et al., Citation2017; McKibbin & Humphreys, Citation2020; Oliver, Citation2007; Saleh & Berlin, Citation2003). Such conditions, if left untreated, place them and others at risk of harm (Knack et al., Citation2019; Saleh & Berlin, Citation2003; Seto, Citation2009; Tabachnick, Citation2013). Indeed, those at risk of harming others can become so stigmatised and vulnerable to community protection legislation (Heasman & Foreman, Citation2019) they do not seek help (Assini-Meytin et al., Citation2020). Paradoxically, for those socially isolated, lonely and experiencing co-morbid conditions, community protection approaches are likely to place them at greater risk of acting on their sexual interests and thus, harming others. While health care professionals are bound by ethical principles and standards, they too are vulnerable to societies norms, and as such it is essential, they receive training and education (Heasman & Foreman, Citation2019; Oliver, Citation2007) to help address or reduce unhelpful beliefs that might impede the care and help required for this population.

One of the benefits of a public health approach that targets people at risk of engaging in CSA is that counter to community protection norms and values, it is ethically justified on the grounds of human dignity (Heasman & Foreman, Citation2019; Knack et al., Citation2019). Indeed, working with people, before they act, has a clear ethical rationale as it; (a) protects and prevents those at risk of victimisation from ever being abused in the first place (Bolen, Citation2003; Grant et al., Citation2019; Knack et al., Citation2019; Levine & Dandamudi, Citation2016; McKibbin & Humphreys, Citation2020; McKillop, Citation2019; McMahon, Citation2000; Tabachnick, Citation2013) and (b) provides those at risk of first-time CSA access to opportunities to help and treat conditions causing them significant psychological and social harm (Apsche et al., Citation2005; Jennings et al., Citation2013; Knack et al., Citation2019; Lasher & Stinson, Citation2017; Levine & Dandamudi, Citation2016; McKibbin & Humphreys, Citation2020; McKillop, Citation2019; Mitchell & Galupo, Citation2018; Tabachnick, Citation2013; Van Horn et al., Citation2015).

Theme five: preventing sexual violence before it occurs is more economically viable than responding to it

Putting to one side moral and ethical reasons for preventing abuse occurring in the first place, sources in this review highlight the economic justifications for operating in this way too (Letourneau et al., Citation2017; Tabachnick, Citation2013). Of course, the “true” cost of sexual violence, or its prevention, can never be fully detailed (Knack et al., Citation2019), however sources present the economic case that responding to CSA after it occurs is far more costly (economically) than preventing it in the first place. Although the presentation of an economic analysis is not the aim of any sources detailed in this review, this features in several discussions. Tabachnick (Citation2013) and Lasher and Stinson (Citation2017) highlight costs of criminal justice strategies predominantly aimed at containing and controlling those convicted of CSA do not demonstrate effective deterrence or prevention of CSA. Indeed, many were implemented without evidence of their effectiveness. Knack et al. (Citation2019) reference sources that detail the vast financial costs of responding to abuse after it occurs including health care, child services and correctional systems, as well as economic costs due to loss of productivity in the labour market. While an economic argument appears to support the notion that preventing sexual violence is far more effective than responding to it, Assini-Meytin et al. (Citation2020) note that federal funding is absent in the United States, instead providers of secondary prevention interventions rely on ad hoc funding from state or private sources. These funds are of course welcome, but equally an unsustainable method to provide a comprehensive public protection approach to preventing CSA (Lee et al., Citation2007; Letourneau et al., Citation2017).

Discussion

To prevent CSA occurring in the first place multifaceted and comprehensive interventions are required. In particular, programmes that target people at risk of engaging in CSA, before they offend, ought to be a priority. Given that people who commit CSA are a heterogeneous group and the aetiology of CSA occurs as a consequence of interacting biological, ecological and neurological causal factors (Ward & Beech, Citation2016); public health approaches are fundamental to a comprehensive solution. Despite knowledge of this, marginal attention has been given to secondary prevention strategies that target people at risk of CSA. Thus, our paper aims to advance knowledge in the field by synthesising the current literature on secondary prevention interventions, by considering their effectiveness, challenges and barriers.

Themes developed from this scoping review found overwhelming support for the notion that to provide a comprehensive response to CSA, secondary prevention interventions that target people at risk of CSA, must be central. Despite a clear sense of the essential factors needed to provide secondary prevention services (Theme One), several barriers and challenges exist (Theme Two). Barriers to people seeking help and those providing help are in the main driven by legislative restrictions as well as problematic social and cultural perceptions, each of which generates unhelpful social constructions around those at risk of CSA, fuelling stigma and shame. This is unsurprising as despite observations of a surge in public and political interest to address and prevent CSA, a persistent reticence to commit public funds and health care resources to people at risk of CSA, even before they offend was noted. Increasing resources continue to be directed into tertiary criminal justice services, long after abuse has occurred. This is despite knowledge that the prevention of CSA is not only a more ethical response to CSA (for both victims/families and people at risk of engaging in CSA) but is a more cost-effective approach too (Theme Four and Five). Instead, post hoc “help” comes under the guise of “public protection” and is underpinned by pervasive policies that result in ongoing stigmatisation, disproportionate punishment and the failure to prevent CSA (Kewley & Brereton, Citationin press).

Regardless of Western CSA prevention approaches being dominated by correctional policy, we do note and report some encouraging shifts such as an increased provision of secondary prevention interventions across several regions (). However, to ensure interventions and services are effective, researchers and funders must overcome methodological limitations (Theme Three). To do this investment in research, policy development and the design, implementation and rigorous testing of services that help and support people at risk of CSA warrants significant national and global improvement.

Limitations

A number of limitations are evident in this work. The first found an under-representation of studies that examined prevention for female populations. While we are mindful the majority of CSA is perpetrated by boys/men, understanding effective strategies that help prevent women and girls from engaging in CSA is an equally important area of concern. Similarly, many countries and regions were not represented in the studies included in this paper. One explanation for this might be the restriction of our search criteria limiting sources to the English language, alternatively, an absence of sources from non-Western regions might also indicate socio-cultural differences and approaches to prevention that require further scrutiny. A third limitation includes the fact that a critical appraisal of sources included was not undertaken, thus, we were unable to establish the reliability of interventions and strategies included. Finally, only the first author undertook the initial screening of titles and abstracts, having a second researcher verify this sift would have strengthen this process.

Conclusions

All children have the right to live free from violence (UN, Citation1989) the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (Article 34) specifically requires “States parties undertake to protect the child from all forms of sexual exploitation and sexual abuse.” The World Health Organization (Citation2016) call governments to action by strengthening seven key strategies to prevent CSA and end violence against children; these include the implementation and enforcement of effective laws, changes in the societal norms and values, provision of safer environments, effective caregiver support, economic strengthening, improved support service, and increased education and life skills (WHO, Citation2016). With greater social and political awareness of CSA, an appetite to respond to this call and prevent CSA before it occurs, is now observed. However, if an effort to prevent CSA occurring in the first place is to be realised, a multisectoral comprehensive response must include strategies for young people and adults at risk of perpetrating CSA. We call for researchers and policy makers to help address this gap by examining the risks related to the perpetration of CSA at all four socioecological levels. Engaging in research and service development through both criminal justice and public health lens will serve to strengthen our knowledge of appropriate target populations, and help facilitate the implementation, testing and review, of secondary prevention interventions for those at risk of offending. CSA is preventable but can only be achieved with commitment from policymakers and long-term funding from central government.

Acknowledgements

We thank the two anonymous reviewers whose encouraging comments and suggestions helped shape and improve this work

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Those with an * are documents included in the review

- *Apsche, J. A., Bass, C. K., Jennings, J. L., Murphy, C. J., Hunter, L. A., & Siv, A. M. (2005). Empirical comparison of three treatments for adolescent males with physical and sexual aggression: Mode deactivation therapy, cognitive behavior therapy and social skills training. International Journal of Behavioral Consultation and Therapy, 1(2), 101. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0100738

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Aromataris, E., & Riitano, D. (2014). Constructing a search strategy and searching for evidence. A Guide to the Literature Search for a Systematic Review. Am J Nursing, 114(5), 49–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Asante, K. O., & Andoh-Arthur, J. (2015). Prevalence and determinants of depressive symptoms among university students in Ghana. Journal of Affective Disorders, 171, 161–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.09.025

- *Assini-Meytin, L. C., Fix, R. L., & Letourneau, E. J. (2020). Child sexual abuse: The need for a perpetration prevention focus. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 29(1), 22–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2019.1703232

- Australia. The Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse. (2017). https://www.childabuseroyalcommission.gov.au/

- Barrett, A., Kamiya, Y., & O’Sullivan, V. (2014). Childhood sexual abuse and later-life economic consequences. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 53, 10–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socec.2014.07.001

- Beauregard, E., Lussier, P., & Proulx, J. (2004). An exploration of developmental factors related to deviant sexual preferences among adult rapists. Sexual Abuse, 16(2), 151–161. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:SEBU.0000023063.94781.bd

- *Beech, A. R., & Harkins, L. (2012). DSM-IV paraphilia: Descriptions, demographics and treatment interventions. Aggression & Violent Behavior, 17(6), 527–539. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2012.07.008

- *Beier, K. M., Grundmann, D., Kuhle, L. F., Scherner, G., Konrad, A., & Amelung, T. (2015). The German Dunkelfeld project: A pilot study to prevent child sexual abuse and the use of child abusive images. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 12(2), 529–542. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12785

- *Beier, K. M., Oezdemir, U. C., Schlinzig, E., Groll, A., Hupp, E., & Hellenschmidt, T. (2016). Just dreaming of them": The Berlin project for primary prevention of child sexual abuse by juveniles (PPJ). Child Abuse & Neglect, 52, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.12.009

- Bentley, H., Fellowes, A., Glenister, S., Mussen, N., Ruschen, H., Slater, B., Turnbull, M., Vine, T., & Wilson, P. (2020). How safe are our children? An overview of data on abuse of adolescents. NSPCC Learning, https://learning.nspcc.org.uk/media/2287/how-safe-are-our-children-2020.pdf

- *Bentovim, A. (2002). Preventing sexually abused young people from becoming abusers, and treating the victimization experiences of young people who offend sexually. Child Abuse & Neglect, 26(6–7), 661–678. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00340-x

- Bertone-Johnson, E. R., Whitcomb, B. W., Missmer, S., Manson, A., Hankinson, J. E., Rich-Edwards, S. E., & W, J. (2014). Early life emotional, physical, and sexual abuse and the development of premenstrual syndrome: A longitudinal study. Journal of Women’s Health, 23(9), 729–739. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2013.4674

- *Bolen, R. M. (2003). Child sexual abuse: Prevention or promotion? Social Work, 48(2), 174–185. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/48.2.174

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1977). Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist, 32(7), 513. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.32.7.513

- *Carpentier, M. Y., Silovsky, J. F., & Chaffin, M. (2006). Randomized trial of treatment for children with sexual behavior problems: Ten-year follow-up. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(3), 482. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.482

- Council of Europe. (2017). Ending all forms of violence against children by 2030: The Council of Europe’s contribution to the 2030 Agenda and the Sustainable Development Goals. https://violenceagainstchildren.un.org/sites/violenceagainstchildren.un.org/files/2030_agenda/sdg_leaflet.pdf.pdf

- Dube, S. R., Anda, R. F., Whitfield, C. L., Brown, D. W., Felitti, V. J., Dong, M., & Giles, W. H. (2005). Long-term consequences of childhood sexual abuse by gender of victim. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 28(5), 430–438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2005.01.015

- *Engel, J., Körner, M., Schuhmann, P., Krüger, T. H. C., & Hartmann, U. (2018). Reduction of risk factors for pedophilic sexual offending. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 15(11), 1629–1637. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2018.09.001

- England and Wales. The Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse. (2016). https://www.iicsa.org.uk/

- *Finkelhor, D. (2009). The prevention of childhood sexual abuse. The Future of Children, 19(2), 169–194. https://doi.org/10.1353/foc.0.0035

- Foubert, J. D., Blanchard, W., Houston, M., & Williams, R. R. (2019). Pornography and sexual violence. In W. O’Donohue & P. Schewe (Eds.), Handbook of sexual assault and sexual assault prevention. (pp. 109–127). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-23645-8_7

- Gannon, T., Rose, M. R., & Ward, T. (2010). Pathways to female sexual offending: Approach or avoidance? . Psychology, Crime & Law, 16(5), 359–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/10683160902754956

- Gillespie, S. M., & Beech, A. R. (2016). Theories of emotion regulation. In D. P. Boer (Ed.), The Wiley handbook on the theories. Assessment and Treatment of Sexual Offending. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118574003.wattso012

- *Grant, B. J., Shields, R. T., Tabachnick, J., & Coleman, J. (2019). I didn’t know where to go": An examination of Stop It Now!’s sexual abuse prevention helpline. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 34(20), 4225–4253. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260519869237

- *Heasman, A., & Foreman, T. (2019). Bioethical issues and secondary prevention for nonoffending individuals with pedophilia. Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics, 28(2), 264–275. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0963180119000094

- Homma, Y., Wang, N., Saewyc, E., & Kishor, N. (2012). The relationship between sexual abuse and risky sexual behavior among adolescent boys: A meta-analysis. Journal of Adolescent Health, 51(1), 18–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.12.032

- Horan, J. M., & Widom, C. S. (2015). Does age of onset of risk behaviors mediate the relationship between child abuse and neglect and outcomes in middle adulthood? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44(3), 670–682. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-014-0161-4

- *Jennings, J. L., Apsche, J. A., Blossom, P., & Bayles, C. (2013). Using mindfulness in the treatment of adolescent sexual abusers: Contributing common factor or a primary modality? International Journal of Behavioral Consultation & Therapy, 8(3/4), 17–22. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0100978

- Jespersen, A. F., Lalumière, M. L., & Seto, M. C. (2009). Sexual abuse history among adult sex offenders and non-sex offenders: A meta-analysis. Child Abuse & Neglect, 33(3), 179–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.07.004

- Jordaan, J., & Hesselink, A. (2018). Criminogenic factors associated with youth sex offenders: A qualitative interdisciplinary case study evaluation. Acta Criminologica: Southern African Journal of Criminology, 31(1), 206–217. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC-11cb2cfda1

- Kavanaugh, B., Holler, K., & Selke, G. A. (2015). Neuropsychological profile of childhood maltreatment within an adolescent inpatient sample. Applied Neuropsychology: Child, 4(1), 9–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622965.2013.789964

- Kewley, S., & Brereton, S. (in press). Public protection. In L. Burke, N. Carr, E. Cluley, S. Collett, & F. McNeill (Eds.), Reimagining probation practice. Routledge.

- *Knack, N., Winder, B., Murphy, L., & Fedoroff, J. P. (2019). Primary and secondary prevention of child sexual abuse. International Review of Psychiatry, 31(2), 181–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540261.2018.1541872

- *Konrad, A., Amelung, T., & Beier, K. M. (2017). Misuse of child sexual abuse images: Treatment course of a self-identified pedophilic pastor. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 44(3), 281–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2017.1366958

- Lake, S., Wood, E., Dong, H., Dobrer, S., Montaner, J., & Kerr, T. (2015). The impact of childhood emotional abuse on violence among people who inject drugs. Drug and Alcohol Review, 34(1), 4–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.12133

- *Landgren, V., Malki, K., Bottai, M., Arver, S., & Rahm, C. (2020). Effect of gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist on risk of committing child sexual abuse in men with pedophilic disorder: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry, 77(9), 897–905. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.0440

- Lanier, P., Kohl, P. L., Raghavan, R., & Auslander, W. A. (2015). Preliminary examination of child well-being of physically abused and neglected children compared to a normative pediatric population. Child Maltreatment, 20(1), 72–79. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559514557517

- *Lasher, M. P., & Stinson, J. D. (2017). Adults with pedophilic interests in the United States: Current practices and suggestions for future policy and research. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46(3), 659–670. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-016-0822-3

- Lee, M. (2017). Sex trafficking and control. In T. Sanders (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of sex offences and sex offenders (pp. 606–624). Oxford University Press.

- *Lee, D. S., Guy, L., Perry, B., Sniffen, C. K., & Mixson, S. A. (2007). Sexual violence prevention. The Prevention Researcher, 14(2), 15–20. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ793248

- *Letourneau, E. J., Brown, D. S., Fang, X., Hassan, A., & Mercy, J. A. (2018). The economic burden of child sexual abuse in the United States. Child Abuse & Neglect, 79, 413–422. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.02.020

- *Letourneau, E. J., Schaeffer, C. M., Bradshaw, C. P., & Feder, K. A. (2017). Preventing the onset of child sexual abuse by targeting young adolescents with universal prevention programming. Child Maltreatment, 22(2), 100–111. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559517692439

- *Levenson, J. S., & Grady, M. D. (2019a). “I could never work with those people … ”: Secondary prevention of child sexual abuse via a brief training for therapists about pedophilia. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 34(20), 4281–4302. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260519869238

- *Levenson, J. S., & Grady, M. D. (2019b). Preventing sexual abuse: Perspectives of minor-attracted persons about seeking help. Sexual Abuse, 31(8), 991–1013. https://doi.org/10.1177/1079063218797713

- *Levenson, J. S., Willis, G. M., & Vicencio, C. P. (2017). Obstacles to help-seeking for sexual offenders: Implications for prevention of sexual abuse. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 26(2), 99–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2016.1276116

- *Levine, J. A., & Dandamudi, K. (2016). Prevention of child sexual abuse by targeting pre-offenders before first offense. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 25(7), 719–737. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2016.1208703

- Mandelli, L., Petrelli, C., & Serretti, A. (2015). The role of specific early trauma in adult depression: A meta-analysis of published literature. Childhood trauma and adult depression. European Psychiatry, 30(6), 665–680. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2015.04.007

- Marshall, W. L. (2010). The role of attachments, intimacy, and loneliness in the etiology and maintenance of sexual offending. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 25(1), 73–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681990903550191

- McCartan, K., Hoggett, J., & Kemshall, H. (2018b). Risk assessment and management of individual’s convicted of a sexual offence in the UK. Sex Offender Treatment, 13(1/2), 1–8. https://dora.dmu.ac.uk/handle/2086/17351

- *McCartan, K. F., Merdian, H. L., Perkins, D. E., & Kettleborough, D. (2018a). Ethics and issues of secondary prevention efforts in child sexual abuse. International Journal of Offender Therapy And Comparative Criminology, 62(9), 2548–2566. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X17723951

- McCarthy-Jones, S., & McCarthy-Jones, R. (2014). Body mass index and anxiety/depression as mediators of the effects of child sexual and physical abuse on physical health disorders in women. Child Abuse & Neglect, 38(12), 2007–2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.10.012

- Mccrory, E. (2011). A treatment manual for adolescents displaying harmful sexual behaviour: Change for good. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- McKibbin, G., Halfpenny, N., & Humphreys, C. (2019). Respecting sexual safety: A program to prevent sexual exploitation and harmful sexual behaviour in out-of-home care. Australian Social Work, https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2019.1597910

- McKibbin, G., & Humphreys, C. (2020). Future directions in child sexual abuse prevention: An Australian perspective. Child Abuse & Neglect, 105, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104422

- McKibbin, G., Humphreys, C., & Hamilton, B. (2017). Talking about child sexual abuse would have helped me": Young people who sexually abused reflect on preventing harmful sexual behavior. Child Abuse & Neglect, 70, 210–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.06.017

- McKillop, N. (2019). Understanding the nature and dimensions of child sexual abuse to inform its prevention. In I. Bryce, Y. Robinson, & W. Petherick (Eds.), Child abuse and neglect: Forensic issues in evidence, impact, and management (pp. 241–259). Elsevier Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-815344-4.00013-1

- McMahon, P. M. (2000). The public health approach to the prevention of sexual violence. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 12(1), 27–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/107906320001200104

- Merdian, H., Kettleborough, D., McCartan, K., & Perkins, D. E. (2017). Strength-based approaches to online child sexual abuse: Using self-management strategies to enhance desistance behaviour in users of child sexual exploitation material. Journal of Criminal Psychology, 7(3), 182–191. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCP-10-2016-0035

- Miner, M. H., Swinburne Romine, R., Robinson, B. B. E., Berg, D., & Knight, R. A. (2016). Anxious attachment, social isolation, and indicators of sex drive and compulsivity: Predictors of child sexual abuse perpetration in adolescent males? Sexual Abuse, 28(2), 132–153. https://doi.org/10.1177/1079063214547585

- Mitchell, R. C., & Galupo, M. P. (2018). The role of forensic factors and potential harm to the child in the decision not to act among men sexually attracted to children. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 33(14), 2159–2179. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260515624211

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

- Moore, A., & Reynolds, P. (2018). Sex, sexuality and social media: A new and pressing danger? In A. Moore & P. Reynolds (Eds.), Childhood and sexuality. Studies in childhood and youth (pp. 225–246). Palgrave Macmillan. . https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-52497-3_10

- New Zealand. The Royal Commission of Inquiry into Abuse in Care. (2020). https://www.abuseincare.org.nz/

- Norman, R. E., Byambaa, M., De. Rumna, Butchart, A., Scott J, & Vos, T. (2012) The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS Medicine, 9(11), e1001349. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001349

- Ó Ciardha, C., & Ward, T. (2013). Theories of cognitive distortions in sexual offending: What the current research tells us. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 14(1), 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838012467856

- Oliver, B. E. (2007). Preventing female-perpetrated sexual abuse. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838006296747

- Parr, J., & Pearson, D. (2019). Non-offending minor-attracted persons: Professional practitioners’ views on the barriers to seeking and receiving their help. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 28(8), 945–967. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2019.1663970

- Pereda, N., Guilera, G., Forns, M., & Gómez-Benito, J. (2009). The prevalence of child sexual abuse in community and student samples: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(4), 328–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.02.007

- Piché, L., Mathesius, J., Lussier, P., & Schweighofer, A. (2018). Preventative services for sexual offenders. Sexual Abuse, 30(1), 63–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/1079063216630749

- Plummer, C. A. (2001). Prevention of child sexual abuse: A survey of 87 programs. Violence and Victims, 16(5), 575–588. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cmedm&AN=11688931&site=ehost-live

- PROSPERO. (n.d.). Welcome to PROSPERO. Retrieved August 25, 2021, from https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/.

- Purvis, M., & Ward, T. (2006). The role of culture in understanding child sexual offending: Examining feminist perspectives. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 11(3), 298–312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2005.08.006

- Quinsey, V. L., & Lalumière, M. L. (1995). Evolutionary perspectives on sexual offending. Sexual Abuse, 7(4), 301–315. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02256834

- Ruzicka, A. E., Assini-Meytin, L. C., Schaeffer, C. M., Bradshaw, C. P., & Letourneau, E. J. (2021). Responsible behavior with younger children: Examining the feasibility of a classroom-based program to prevent child sexual abuse perpetration by adolescents. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2021.1881858

- Saied-Tessier, A. (2014). Estimating the costs of Child Sexual Abuse in the UK. NSPCC. http://www.nspcc.org.uk/globalassets/documents/research-reports/estimating-costs-child-sexual-abuse-uk.pdf

- Saleh, F. M., & Berlin, F. S. (2003). Sex hormones, neurotransmitters, and psychopharmacological treatments in men with paraphilic disorders. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 12(3–4), 233–253. https://doi.org/10.1300/J070v12n03_09

- Sandler, J. C., Freeman, N. J., & Socia, K. M. (2008). Does a watched pot boil? A time-series analysis of New York State’s sex offender registration and notification law. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 14(4), 284. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013881

- Schaefer, G. A., Mundt, I. A., Feelgood, S., Hupp, E., Neutze, J., Ahlers, C. J., Goecker, D., & Beier, K. M. (2010). Potential and Dunkelfeld offenders: Two neglected target groups for prevention of child sexual abuse. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 33(3), 154–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2010.03.005

- Schmucker, M., & Lösel, F. (2017). Sexual offender treatment for reducing recidivism among convicted sex offenders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 13(1), 1–75. https://doi.org/10.4073/csr.2017.8

- Schulz, A., Bergen, E., Schuhmann, P., & Hoyer, J. (2017). Social anxiety and loneliness in adults who solicit minors online. Sexual Abuse, 29(6), 519–540. https://doi.org/10.1177/1079063215612440

- Scotland. The Scottish Child Abuse Inquiry. (2018). www.childabuseinquiry.scot

- Serin, R. C., Mailloux, D. L., & Malcolm, P. B. (2001). Psychopathy, deviant sexual arousal, and recidivism among sexual offenders. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 16(3), 234–246. https://doi.org/10.1177/088626001016003004

- Seto, M. C. (2009). Pedophilia. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 5(1), 391–407. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.032408.153618

- Seto, M. C. (2019). The motivation-facilitation model of sexual offending. Sexual Abuse, 31(1), 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/1079063217720919

- Shields, R. T., Murray, S. M., Ruzicka, A. E., Buckman, C., Kahn, G., Benelmouffok, A., & Letourneau, E. J. (2020). Help wanted: Lessons on prevention from young adults with a sexual interest in prepubescent children. Child Abuse & Neglect, 105, 104416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104416

- Silovsky, J. F., Hunter, M. D., & Taylor, E. K. (2019). Impact of early intervention for youth with problematic sexual behaviors and their caregivers. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 25(1), 4–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552600.2018.1507487

- Sitney, M. H., & Kaufman, K. L. (2020). A chip off the old block: The impact of fathers on sexual offending behavior. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 22(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838019898463

- Smallbone, S. W., & McCabe, B. A. (2003). Childhood attachment, childhood sexual abuse, and onset of masturbation among adult sexual offenders. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 15(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020616722684

- Tabachnick, J. (2013). Why prevention? Why now? International Journal of Behavioral Consultation and Therapy, 8(3–4), 55. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0100984

- Tardif-Williams, C. Y., Tanaka, M., Boyle, M. H., & MacMillan, H. L. (2017). The impact of childhood abuse and current mental health on young adult intimate relationship functioning. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 32(22), 3420–3447. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260515599655

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

- United Nations. (1989). Convention on the rights of the child. Treaty no. 27531. United Nations Treaty Collection. https://treaties.un.org/Pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=IND&mtdsg_no=IV-11&chapter=4

- United Nations General Assembly. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, A/RES/70/1. https://www.refworld.org/docid/57b6e3e44.html

- Van Horn, J., Eisenberg, M., Nicholls, C. M., Mulder, J., Webster, S., Paskell, C., Brown, A., Stam, J., Kerr, J., & Jago, N. (2015). Stop it Now! A pilot study into the limits and benefits of a free helpline preventing child sexual abuse. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 24(8), 853–872. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2015.1088914

- Ward, T., & Beech, A. R. (2016). The integrated theory of sexual offending–revised. In D. P. Boer (Ed.), The Wiley handbook on the theories, Assessment and treatment of sexual offending. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118574003.wattso006.

- Weber, S., Jud, A., & Landolt, M. A. (2016). Quality of life in maltreated children and adult survivors of child maltreatment: A systematic review. Quality of Life Research, 25(2), 237–255. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-015-1085-5

- Wilpert, J., & Janssen, E. (2020). Characteristics of offending and non-offending child sexual abuse helpline users explored. Journal of Forensic Practice, 22(3), 173–183. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFP-03-2020-0011

- Wojcik, M. L., & Fisher, B. S. (2019). Overview of adult sexual offender typologies. In W. T. O’Donojue & P. A. Schewe (Eds.), Handbook of sexual assault and sexual assault prevention (pp. 241–256). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-23645-8_14

- World Health Organization. (2010). Addressing violence against women and HIV/AIDS. What works? Report of a consultation. Geneva, World Health Organization and Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44378/9789241599863_eng.pdf?sequence=1

- World Health Organization. (2016). INSPIRE: Seven strategies for ending violence against children. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/inspire-seven-strategies-for-ending-violence-against-children

- Wright, K., Swain, S., & Sköld, J. (2020). The age of inquiry: A global mapping of institutional abuse inquiries. La Trobe University, 10, 22. https://doi.org/10.4225/22/591e1e3a36139

- Yuan, N. P., Duran, B. M., Walters, K. L., Pearson, C. R., & Evans-Campbell, T. A. (2014). Alcohol misuse and associations with childhood maltreatment and out-of-home placement among urban two-spirit American Indian and Alaska native people. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 11(10), 10461–10479. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph111010461

- Zhu, Q., Gao, E., Cheng, Y., Chuang, Y.-L., Zabin, L. S., Emerson, M. R., & Lou, C. (2015). Child sexual abuse and its relationship with health risk behaviors among adolescents and young adults in Taipei. Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health, 27(6), 643–651. https://doi.org/10.1177/1010539515573075.