ABSTRACT

Māori adolescents are more likely to have lived through an array of adverse experiences due to unequal exposure to social disadvantage that Indigenous Māori face in Aotearoa New Zealand. Most of this disadvantage arises from intergenerational inequity resulting from the British colonial process. This study aimed to investigate how disadvantage manifests in the backgrounds of Māori adolescents with harmful sexual behaviours. Background characteristics in a sample of 1024 males (aged between 12 and 17), who were referred to a treatment programme for harmful sexual behaviour, were analysed and comparisons made between Māori and non-Māori on risk factors. Māori exhibited higher rates of risk factors (substance abuse, familial criminality, physical abuse victimisation and family violence) at different contextual levels (i.e. individual, family, school). Risks of school exclusion and sexual abuse victimisation were similar across ethnicities. Recommendations are made for prevention/treatment efforts that use holistic and culturally informed approaches.

PRACTICE IMPACT STATEMENT

Culturally appropriate treatment for Māori with harmful sexual behaviours (HSBs) is recommended. This needs to be led by Māori, for Māori and with Māori, including whānau/family-based treatment and prevention.

Glossary

| Aotearoa | = | New Zealand |

| Hapū | = | wider family group |

| Hauora | = | wellbeing |

| Iwi | = | tribal group |

| Kaiako | = | teacher(s) |

| Kaimahi | = | staff |

| Kaupapa | = | purpose, cause |

| Māori | = | collective term for Indigenous people of New Zealand |

| Pākehā | = | New Zealand Europeans |

| Pōwhiri | = | process of welcome |

| Rangatahi Māori | = | Māori young people |

| Te Ao Māori | = | the Māori world |

| Te reo Māori | = | the Māori language |

| Tikanga | = | customs, protocol |

| Whakapapa | = | genealogy |

| Whakatauki | = | proverb |

| Whakawhanaungatanga | = | building connections |

| Whānau | = | family(s) |

Kia whakatōmuri te haere whakamua

I walk backwards into the future with my eyes fixed on my past

Introduction

In their research regarding early childhood education, Rameka (Citation2017) used the above whakatauki (proverb) to speak to the MāoriFootnote1 perspective of time, specifically that the past, present and future are inextricably intertwined. It is well understood that the wellbeing of Māori is directly linked to the colonial history which has disadvantaged Māori in many areas of society. Being better equipped to change the status quo means having a better understanding of what Māori have experienced. Of interest in this study is how we can use this way of thinking to better understand and support Māori adolescents with harmful sexual behaviours (HSBs).

HSB among youth in Aotearoa New Zealand

In Aotearoa New Zealand,Footnote2 adolescents who engage in HSBs commit around 15% of sexual abuse in the community (Ministry of Justice, Citation2009; NZ Police, Citation2018). Between 1994 and 2012, young people under the age of 17 years made up 13% of all individuals apprehended for all sexual offences (Statistics New Zealand, Citation2013). However, it is widely acknowledged that the true figure would be higher due to the underreporting of all forms of crime, particularly those of a sexual nature.

Māori youth offending in Aotearoa New Zealand

The Māori population comprises approximately 17% of the total population of Aotearoa New Zealand (Statistics New Zealand, Citation2020), yet rangatahi Māori make up the largest percentage of youth (57%) charged in a Youth or Rangatahi Court (Ministry of Justice, Citation2020; Rangatahi loosely translates as “Māori youth”). The 2019/2020 Youth Justice Indicator statistics show that Māori young people were 8.3 times more likely to appear in Youth Court than were European/Other youth (Ministry of Justice, Citation2020). Also in 2020, Māori rangatahi comprised 70% of admissions into a secure government youth-justice residence (Oranga Tamariki, Citation2020). These statistics paint a bleak picture of Indigenous youth in the justice system and hence a pressing need to better respond and improve life outcomes (Lambie, Citation2018a, Citation2018b).

Who are adolescents with harmful sexual behaviour?

Harmful sexual behaviour (HSB), as defined by SAFE Network’s (Citation1998) treatment programme manual,Footnote3 can encompass many features. The relationship between perpetrator and victim is usually characterised by inequality, a lack of consent and/or use of force. HSB can include “hands-off” offending (voyeurism, public masturbation), “hands-on” offending (sodomy, vaginal penetration), indecent assault, and sexual acts with animals.

Researchers point to early life experience, family factors, social factors, experience of trauma, exposure to pornography and societal influences as all potentially playing a role in the development of such behaviours (Calder, Citation2007; Hackett et al., Citation2013; Malvaso et al., Citation2020; Rich, Citation2011). Previous research has identified numerous background characteristics that seem to be risk factors for the development of HSB in adolescence (Malvaso et al., Citation2020; Seto & Lalumière, Citation2010). These include but are not limited to previous abuse victimisation (physical, emotional and sexual – Burton, Citation2003; DeLisi et al., Citation2014; Hackett et al., Citation2013; Harrelson et al., Citation2017; Johnson & Knight, Citation2000), non-sexual offending behaviour (Righthand & Welch, Citation2004) and presence of psychological disorders (Seto & Lalumière, Citation2010).

Māori adolescents with harmful sexual behaviour

In 1840, the Treaty of Waitangi was signed between Māori and representatives of the British Crown. The document was aimed at designating sovereignty and creating partnership between the two nations (Orange, Citation2004). Following the Treaty signing, Māori were subjugated through the process of colonisation (Walker, Citation2004). Colonisation resulted in loss of Māori language and culture, land confiscation, mass urbanisation and warfare. Like colonised Indigenous peoples worldwide (Kirmayer & Brass, Citation2016), Māori have been left hugely disadvantaged in measures of health (Baxter et al., Citation2006; Ellison-Loschmann & Pearce, Citation2006), education (Bishop et al., Citation2009), and justice (Department of Corrections, Citation2007; Lambie, Citation2018a, Citation2018b).

A challenge for researchers and policy-makers in Aotearoa NZ are distinct differences and treatment needs between Māori and non-Māori with HSBs. Māori youth are significantly overrepresented in general offending statistics, making up 60% of all police apprehensions of those aged 14–16 years, despite comprising only 25% of this age-group (Oranga Rangatahi, Citation2018). Criminal offending statistics are representative of wider contextual problems facing Māori.

Previous research with Māori youth with HSBs has produced mixed findings. Lim et al. (Citation2012) investigated differences in victimisation histories between Māori and Pākehā (NZ European) adolescents with HSBs as well as differences in Child Behaviour Checklist (CBCL) data. After controlling for socioeconomic factors, they found that Māori adolescents in their study were more likely than Pākehā to have been exposed to physical abuse, emotional abuse and neglect. Similar rates of exposure to sexual abuse were found in the two groups. Their results indicated that individual, family and societal risk factors associated with HSB might be found in higher rates among Māori youth, highlighting the need for holistic, culturally informed treatment.

Research on specialised treatment experiences for Māori with HSBs at the SAFE Programme (Ape-Esera & Lambie, Citation2019) used qualitative interviews with rangatahi, whānau (family) and kaimahi (staff) to investigate treatment strengths and weaknesses. The rangatahi programme at SAFE was developed by Māori, for Māori youth and facilitated by Māori staff (see Ape-Esera & Lambie, Citation2019, for more detail). Māori therapeutic approaches included a core cultural framework, Te Wharenui (the meeting house), a cultural model the staff created that was simple, addressed sexually abusive behaviour and acted as a foundation for other Māori models. Te Wharenui uses the carved meeting house as a model because it has relevance to all of the rangatahi (regardless of the tribal area they come from). The wharenui is one of the most important buildings within a tribal setting, a powerful symbol of identity and community (Durie, Citation2001).

Ape-Esera and Lambie (Citation2019) found that treatment experience was enhanced for the participants through the integration of Māori beliefs and processes into the western therapeutic approaches (such as CBT). Having Māori staff running the programme was also important to participants. Overall, their study demonstrated the importance of culturally informed approaches to treatment with Māori adolescents, which has been recommended in previous research (Lambie et al., Citation2001, Citation2007; Lambie & Seymour, Citation2006).

As well as making sure treatment has a major cultural component to it, incorporating tikanga (customs, protocol), te reo Māori (the Māori language) and Māori staff, Lim et al. (Citation2012) pointed to the differential exposure to risk factors that Māori may face and therefore treatment/prevention needs to focus specifically on these associated risk factors.

There has been no evidence to date that the recommendations of previous research on young Māori with HSBs have been heard or actioned.

Indigenous adolescents with harmful sexual behaviours

International research comparing Indigenous and non-Indigenous youth with HSBs can also give insight into ethnic differences. Rojas and Gretton (Citation2007) investigated the backgrounds and characteristics of Aboriginal youth with HSBs in British Columbia, Canada and found that Aboriginal youth were more likely than non-Aboriginal youth to have background histories of substance abuse, fetal alcohol spectrum disorders, child abuse victimisation, academic difficulties and unstable living environments. In a related study, Bertrand et al. (Citation2013) made ethnic comparisons between Aboriginal, Canadian-born, immigrant and other adolescents with HSBs. They were able to replicate many of the findings of Rojas and Gretton (Citation2007), albeit not to the same degree. Both these studies attributed their findings to the fact that Aboriginal youth in Canada (not just those with HSBs) are more likely to be exposed to these risk factors, largely as a result of the historical injustice faced by Indigenous peoples and the subjugated position they occupy now. McCuish et al. (Citation2017) supplemented these results, finding Indigenous youth with HSBs in Canada were more likely to have a familial history of both sexual abuse and physical abuse passing down through generations. Again, their results were attributed to a trickle-down effect of historical colonial violence and oppression against Indigenous people in Canada.

In a similar but more recent study, Adams et al. (Citation2019) compared developmental histories and onset characteristics of Indigenous and non-Indigenous youth with HSBs in Australia. They found Indigenous youth to be disproportionately exposed to higher rates of systemic criminogenic factors at most environmental levels (e.g. family, school, peers and community). Consistent with Rojas and Gretton (Citation2007), Adams et al. (Citation2019) found that Indigenous youth were significantly more likely than non-Indigenous youth to engage in substance misuse both prior to and during the onset of their sexual offending. They were also twice as likely to drop out of formal schooling prior to their offence. Although less than half of their sample had been exposed to a criminogenic family environment before their offence, Indigenous youth comprised a significant majority of those who were. Contrary to Rojas and Gretton (Citation2007), Adams et al. (Citation2019) found similar rates of child abuse and neglect between Indigenous (76%; n = 80) and non-Indigenous youth with HSBs (70%; n = 131) in their study.

The current study

The aim of the current study was to better understand the background and experiences of youth with HSBs in Aotearoa NZ, to make recommendations to improve treatment/prevention efforts and to supplement previous research and recommendations. Combining the knowledge that developmental history contributes to the development of HSBs and that Māori are likely to be disproportionately exposed to socially disadvantaged contexts, the current study compares the background characteristics and experiences of Māori and Pākehā youth with HSBs to identify risk factors specific to these populations. Identifying these risk factors can give insight to researchers, clinicians, and policy-makers into how treatment efforts may better cater for Māori youth. There is an obligation to improve prevention and treatment efforts for Māori given that (1) Māori youth are overrepresented in patterns of general offending (Oranga Rangatahi, Citation2018) and (2) the obligations to Māori in healthcare set by the Treaty of Waitangi (as stipulated in the New Zealand Public Health and Disability Act, Citation2000; Ministry of Health, Citation2014). Beyond these explicit aims, there is also a need to increase the limited research on adolescent HSBs in Aotearoa NZ, especially with Māori.

Data on a sample of adolescents referred to local treatment programmes for adolescents with HSBs (SAFE, STOP and WELLSTOP) were analysed. SAFE had a Māori-oriented programme, as noted above (Ape-Esera & Lambie, Citation2019); similar specialist programmes for Māori rangatahi had not been developed at either WELLSTOP or STOP, but each programme had Māori staff who worked with rangatahi utilising Māori therapeutic practices where appropriate.

Specifically, experiences of substance abuse, exclusion from school, familial criminality, sexual abuse victimisation, physical abuse victimisation and family violence were compared between Māori and Pākehā adolescents in the sample. These variables have previously been demonstrated to be more associated with the backgrounds of Indigenous adolescents in studies of HSBs (Adams et al., Citation2019; Rojas & Gretton, Citation2007); therefore, they provide a useful starting point for examining the developmental histories of these adolescents. Both Lim et al. (Citation2012) and Adams et al. (Citation2019) usefully analysed risk factors between Indigenous and non-Indigenous youth at different environmental levels (i.e. individual, family, societal; Bronfenbrenner, Citation1994); the variables chosen in our study cover the different contextual levels mentioned, namely individual, family and school risk factors. This broad assessment can help inform a holistic approach to prevention and treatment, such as is recommended in Māori health approaches (Durie, Citation1994). Additionally, this broader assessment may also give insight into how whānau and whānau service-providers can best act to prevent the development of HSBs in adolescents, as the presence of the risk factors investigated largely depend on the hauora (wellbeing) of the entire whānau, rather than just the rangatahi themselves.

Based on the findings of Lim et al. (Citation2012), Rojas and Gretton (Citation2007) and Adams et al. (Citation2019), we expect that Māori adolescents as compared with Pākehā adolescents will have higher exposure to substance abuse, exclusion from school, familial criminality, sexual abuse, physical abuse and family violence. This is also expected based on what is known about Māori social disadvantage more generally, with other research demonstrating that Māori in general have a higher chance of being exposed to these factors (Baxter et al., Citation2006; Bishop et al., Citation2009; Department of Corrections, Citation2007; Ellison-Loschmann & Pearce, Citation2006).

Reiterating assertions made by Lim et al. (Citation2012) and Adams et al. (Citation2019), it is not our intention to identify areas of ethnic “weakness” between Māori and Pākehā; instead, the objective is to provide more information about the possible differential factors present and improve approaches to prevention and avenues for whānau and whānau service intervention. This objective also relates to our positions as researchers, briefly outlined below.

Researchers’ positions

The researchers consist of Tangata Whenua (people of Aotearoa NZ), Tangata Tiriti (non-Indigenous to Aotearoa NZ) and Tangata Moana (people of the Pacific Ocean). The primary author is Ngāti Tūwharetoa, Ngāti Raukawa, Ngāti Porou, the second author is Pākehā/Scottish and the third author is Samoan. This research was completed by the primary author, with supervision by the remaining authors. Given the lived experience of the primary author, a culturally appropriate and sensitive approach to working with Māori was a key priority. This was complemented by the remaining authors, who have researched with and worked with Māori in the community. The second author has worked with Māori clients and colleagues for over 30 years and received cultural supervision throughout. The third author engages in a tuakana-teina (sibling) relationship with Māori, given the historical connection between Māori and Pacific people to ensure respect is honoured within research realms.

Method

Sample

The sample was of adolescents referred to one of three community agencies delivering programmes in Aotearoa NZ (SAFE in Auckland, WELLSTOP in Wellington and STOP in Christchurch). The final study sample included 1024 males aged between 12 and 17.8 years (M = 14.71, SD = 1.38). The study sample included youth in the SAFE programme (n = 530), STOP programme (n = 262) and the WELLSTOP programme (n = 232).

Data collection

Data were sourced from the three community treatment agencies following approval of ethics and confidentiality protocols . Assessment data were requested from the three agencies and included a review of their client files. This involved a review of demographic data, behavioural, health, and mental health information on adolescents referred for treatment. Information that was personal or could identify the clients and/or their families was kept confidential. File information was entered into an Excel spreadsheet with an encrypted password, with personal or identifying information anonymised to ensure confidentiality was maintained at all times. Data were collected by the researchers directly from the client files at SAFE. Data from WELLSTOP and STOP were entered into an Excel spreadsheet by staff onsite and sent online with an encrypted password. The data were then collated into one spreadsheet with all data from the three agencies.

Sample description variables

Age of referral. The age of the client when referred to the treatment programme was categorised into three age groups: 12–13 years, 14–16 years, and 17 years of age.

Ethnicity. The dataset included the ethnicities: “Māori”, “NZ European” [Pākehā].

Programme. The treatment programme the client was referred to: SAFE, STOP or WELLSTOP.

Treatment status. Indicates whether the client completed treatment successfully, dropped out prematurely or received no treatment. Drop-out/No-treatment reasons included (but were not limited to): Client moved away; Special needs; Too young or too old; Financial reasons; Placement issues; or Moving to alternative treatment.

Residential status. As at the start of treatment: The client was resident with family (family home or extended family home); not with family (one-on-one out of home, group home or other); or unknown (missing this information).

Background variables of interest in the current study

Substance abuse. Whether the client had previously engaged in substance abuse of any kind (Yes/No)

Familial criminality. Whether any member of the client’s family has engaged in criminal activity (Yes/No)

Exclusion from school. Whether there was evidence of the client being excluded from school (Yes/No)

Sexual abuse. Whether there was evidence of the client being the victim of any sexual abuse (Yes/No)

Physical abuse. Whether there was evidence of the client being the victim of any physical abuse (Yes/No)

Family violence. Whether there was evidence of violence in the client’s family (Yes/No).

Analysis

Data were analysed quantitatively using IBM SPSS 1.0.0.1461 software. Univariate contingency table analysis with Fisher’s exact test was performed to determine significance analysis of ethnicity/substance abuse, ethnicity/familial criminality, ethnicity/exclusion from school, ethnicity/sexual abuse, ethnicity/physical abuse and ethnicity/family violence. Following this, exploratory multivariate modelling using logistic regression was used to predict the presence of variables based on ethnicity. Only variables identified as being significantly different between Māori and Pākehā in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate analysis. Background variables found to be highly correlated as well as being closely related in nature (e.g. family violence and physical abuse) were also excluded from the multivariate analysis so as to avoid redundancy of variables. Correlation between nominal variables was measured using the phi coefficient (or mean square contingency coefficient) which is a measure of association between binary variables. The main purpose of the exploratory multivariate analysis was to investigate possible interaction effects between variables or, conversely, independent effects of background variables. An alpha of 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance for all statistical tests.

Results

Sample descriptors

shows demographic, treatment and residential status information. Most of the sample were 14–16 years (61.7%), followed by the 12- to 13-year age-group (32.8%) and just 5.5% were age 17. Just over one-third identified as Māori (34.2%) with the rest identifying as Pākehā (65.8%). The largest proportion of adolescents referred ended up completing treatment (43.9%) while smaller proportions ended treatment prematurely (23.1%) or received no treatment (32.9%). Most clients lived with family (either immediate or extended; 66.8%); around a quarter lived with non-family (25.8%) and there was no residence information available for the rest (7.4%).

Table 1. Frequencies and percentages of demographic, treatment and residential information.

shows the frequencies and percentages of background variables for the entire sample. About one-third (32.9%) had previously engaged in some form of substance abuse while two-thirds had not (66.9%). Most clients (85.2%) did not have family criminality in their background; fewer than one in ten (8.6%) did have; and this information was not available for a notable number of clients (6.3%). More than one-third had been previously excluded from school (37.1%); a majority had not (62.8%). A large proportion had experienced some form of sexual abuse (42.5%) while more than half had not (57.5%). These rates were similar for physical abuse, with just under half having experienced some form of physical abuse (45%) and just over half had not (54.9%). Just over half (50.3%) had evidence of family violence in their backgrounds compared with those who had not (49.6%).

Table 2. Frequencies and percentages of background variables of interest.

Univariate analyses comparing Māori and Pākehā background characteristics

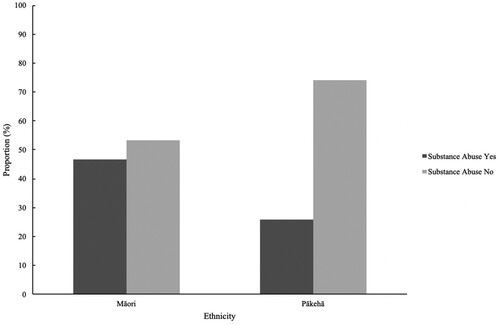

Two cases were excluded due to lack of information for the substance abuse variable. As shown in , 33% of the sample had previously engaged in some form of substance abuse. shows the breakdown of this by ethnicity.

For Māori participants, 46.7% had previously engaged in some form of substance abuse while 53.3% had not. In contrast, 25.9% of Pākehā participants had previously engaged in some form of substance abuse while 74.1% had not, a significant difference between ethnicities (p < .001; ), with the odds of Māori using substances being 2.51 times the odds of Pākehā (95% CI [1.92, 3.30]; ).

Table 3. Summary of univariate analyses of variables of interest with proportions of variables according to ethnicity.

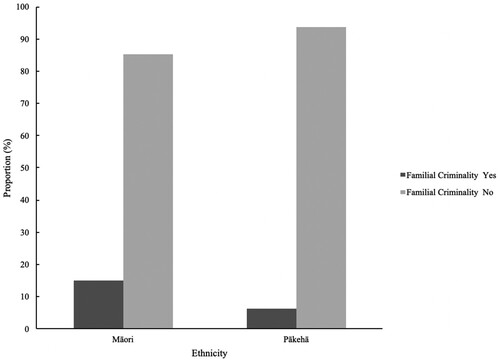

For the familial criminality variable, 64 cases were excluded due to lack of information. shows the breakdown by ethnicity of the 8.6% of the sample () who had a family member(s) who had engaged in criminal activity.

There were 14.9% of Māori participants who had a family member(s) who had engaged in criminal activity, while 85.1% had not. For Pākehā participants, 6.3% had experienced familial criminality, while 93.7% had not. This difference between ethnicities was significant (p < .001; ). The odds of Māori having a family member(s) who had previously engaged in criminal activity was 2.62 times the odds of Pākehā (95% CI [1.68, 4.08]; ).

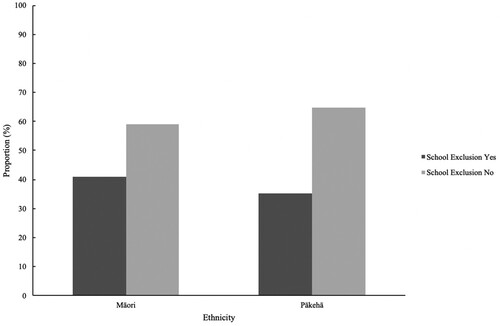

As shown in , 37.1% of the sample had previously been excluded from school before their referral. One case was excluded due to lack of information. shows this broken down by ethnicity.

For Māori participants, 40.9% had been previously excluded from school while 59.1% had not. For Pākehā, 35.2% had been excluded from school while 64.8% had not. The odds of Māori being excluded from school was 1.27 times the odds of Pākehā (95% CI [.97–1.66]; ). This difference between ethnicities in school exclusion was not statistically significant (p = .088; ).

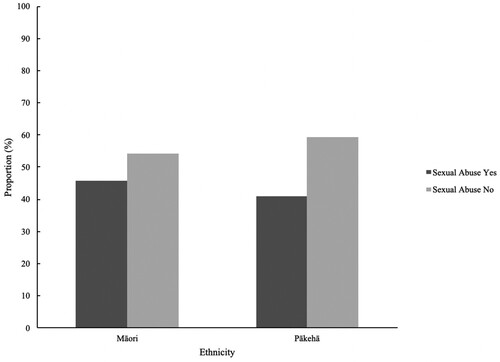

Of the entire sample, 42.5% had evidence of being a victim of sexual abuse (). shows this broken down by ethnicity.

For Māori participants, 45.7% had been a victim of sexual abuse while 54.3% had not. For Pākehā, 40.8% had been a victim of sexual abuse while 59.2% had not. The odds of Māori previously experiencing sexual abuse was 1.22 the odds of Pākehā (95% CI [.94, 1.59]; ). This difference was not statistically significant (p = .13).

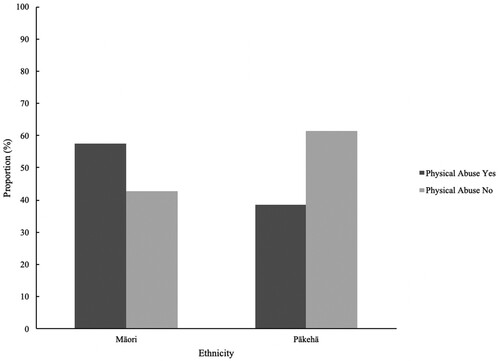

Analysis of the variable physical abuse showed that 45% of the sample had evidence of previously being a victim of physical abuse (). One case was removed due to lack of information. shows physical abuse rates by ethnicity.

For Māori participants, 57.4% had previously experienced physical abuse while 42.6% had not. For Pākehā, 38.6% had experienced physical abuse while 61.4% had not. The odds of Māori having experienced physical abuse were 2.14 times the odds of Pākehā (95% CI [1.65, 2.79]; ), a significant difference (p < .001).

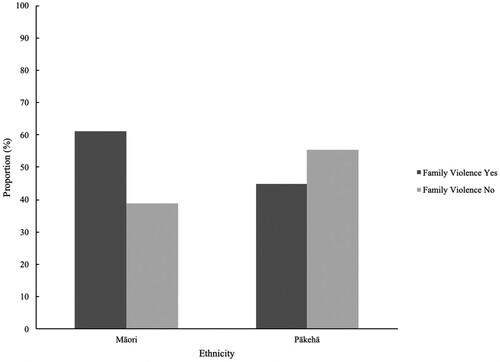

Family violence was evident in the backgrounds of 50.3% of the overall sample. One case was removed during analysis due to lack of information. shows family violence rates by ethnicity.

For Māori participants, 61.1% had evidence of family violence in their background while 38.9% did not. For Pākehā, 44.7% of the sample had family violence in their background while 55.3% had not. The odds of Māori having family violence in their background was 1.95 times the odds of Pākehā (95% CI [1.5, 2.53]; ), a statistically significant difference (p < .001).

Correlations between variables of interest

shows Phi correlations between all variables included in the univariate analysis. Physical abuse and family violence showed the highest correlation (Φ = .55).

Table 4. Phi correlations between variables included in univariate analysis.

Exploratory multivariate analysis

Variables identified as being differentially present by ethnicity and where the difference was statistically significant (substance abuse, familial criminality, and physical abuse) were included in exploratory multivariate analysis. Family violence was excluded from this analysis due to its high correlation with physical abuse. show analytic results from the exploratory multivariate analysis.

Table 5. Summary of logistic regression analysis for variables predicting substance abuse controlling for other variables of interest.

Table 6. Summary of logistic regression analysis for variables predicting familial criminality controlling for other variables of interest.

Table 7. Summary of logistic regression analysis for variables predicting physical abuse controlling for other variables of interest.

Exploratory multivariate analyses revealed that the majority of significant differences found in the univariate analyses between ethnicities (substance abuse, familial criminality, physical abuse) remained even when accounting for interactive effects between variables.

With regards to substance abuse, the odds of Māori adolescents engaging in substance abuse were 2.33 times the odds of Pākehā (95% CI [1.75, 3.11]; ) when accounting for the presence of familial criminality and physical abuse. This odds ratio is slightly smaller than the result found in the univariate analysis (odds ratio = 2.51; ) for substance abuse, indicating that a slight amount of the presence of substance abuse differentiated by ethnicity is explained by the presence of familial criminality and physical abuse.

Results were similar for the multivariate analysis of familial criminality. The odds of Māori adolescents having familial criminality in their background was 2.14 the odds of Pākehā (95% CI [1.35, 3.39]; ) when accounting for the presence of substance abuse and physical abuse. This odds ratio is also slightly smaller than the result found in the univariate analysis (odds ratio = 2.62; ) for familial criminality, indicating that a slight amount of the presence of familial criminality differentiated by ethnicity is explained by the presence of substance abuse and physical abuse.

Lastly, results around physical abuse were similar in the multivariate analysis. The odds of Māori having experienced physical abuse was 1.86 the odds of Pākehā (95% CI [1.4, 2.47]; ) when accounting for the presence of substance abuse and familial criminality. Again, this is slightly lowered compared to the result found in the univariate analysis for physical abuse (odds ratio = 2.14; ), indicating that a slight amount of the presence of physical abuse victimisation differentiated by ethnicity is explained by the presence of substance abuse and physical abuse.

Despite results being slightly lowered when accounting for inter-variable explanation, there was still significantly higher presence of substance abuse, familial criminality and physical abuse among Māori adolescents in the sample.

Discussion

Māori youth with HSBs in the sample presented with higher rates of substance abuse, familial criminality, physical abuse victimisation and family violence than did Pākehā. Similar rates of school exclusion and sexual abuse victimisation were found with both Māori and Pākehā youth with HSBs.

Of the entire sample, 33% were found to have previously engaged in some sort of substance abuse prior to their referral to the treatment programme. Previous substance abuse was significantly higher for Māori (47%) compared with Pākehā (26%). This is consistent with findings from Rojas and Gretton (Citation2007) who found higher rates of substance abuse among Indigenous youth with HSBs (57%; n = 102) in their study, compared with non-Indigenous (29%; n = 257), and also with Adams et al.’s (Citation2019) findings.

Of the entire sample, relatively few had evidence of criminality in their family background (9%). International studies have reported higher rates of familial criminality among youth with HSBs, upwards of 20% (Ford & Linney, Citation1995; Oliver et al., Citation1993; Van Wijk et al., Citation2007). When broken down by ethnicity, familial criminality was significantly higher for Māori (15%) compared with Pākehā (6%), but still not as high as international findings. The increased odds of Māori having criminality in their family background, compared with Pākehā, was consistent with Adams et al.’s (Citation2019) results, where Indigenous youth with HSBs (61%) were more likely to have familial criminality than were non-Indigenous (42%), albeit their overall rate of familial criminality (50%) was much higher than the rate found in our study.

Many youth with HSBs (37%) had been excluded from school prior to their referral; slightly more Māori (41%) than Pākehā (35%) had faced school exclusion, but this difference was not statistically significant. Adams et al. (Citation2019) found a significantly higher proportion of Indigenous youth (49%) exhibiting school dropout compared with non-Indigenous (25%), but measures are different – school dropout is usually the student’s choice, whereas school exclusion in Aotearoa NZ is a more formal process decided by the student’s school. Results from the current study, like other studies mentioned, point to poor school engagement (whether it be dropout or exclusion) as a risk factor for HSBs.

The sample had high rates of sexual abuse victimisation in their backgrounds, with 43% having experienced some form of sexual abuse prior to referral; far higher than general population rates of sexual abuse of young people in Aotearoa NZ (14%; Fergusson et al., Citation2008). A slightly higher proportion of Māori (46%) than Pākehā (41%) had experienced sexual abuse; this was a statistically insignificant difference. This was in line with Lim et al. (Citation2012) who found exactly the same rate of sexual abuse between Māori and Pākehā in their study (40%), whereas Rojas and Gretton (Citation2007) found a significantly higher proportion of Indigenous youth with HSBs (65%) had experienced some form of sexual abuse, compared with non-Indigenous (48%).

Rates of physical abuse were high in the sample overall, at almost half (45%), higher than what is reported in the general youth population (Clark et al., Citation2013). A significantly higher proportion of Māori youth with HSBs (57.4%) had experienced some form of physical abuse compared with Pākehā (38.6%). Lim et al. (Citation2012) reported similar results, with more Māori (61.3%) experiencing physical abuse than did Pākehā (36%). This is also consistent with research around physical abuse and Indigenous youth with HSBs internationally (McCuish et al., Citation2017; Rojas & Gretton, Citation2007).

The last variable analysed in this study was the presence of family violence in the backgrounds of youth with HSBs. It was found during analyses that this was highly correlated with rates of physical abuse, indicating that caution should be taken when drawing conclusions using both variables in tandem. A majority (by a slight margin; 50.3%) of the sample had evidence of family violence in their background. This was found to be significantly higher for Māori (61%) as compared with Pākehā (45%). This is consistent with general statistics around ethnic disparities of family violence in Aotearoa NZ (Te Puni Kōkiri, Citation2017).

While the above discussions of the findings and how they relate to the sexual abuse literature is important, one cannot ignore the broader contextual factors that have impacted upon Māori for generations (Thom & Grimes, Citation2022). “Māori have been over-represented at all stages of the criminal-justice system and there are multiple and complex reasons for this, not least because Māori tend to experience disproportionately many interacting risk factors” (Lambie, Citation2018b, p. 24). Although the criminal-justice system has acknowledged the links between racism/colonisation and loss of identity/self-esteem in Māori offending, until recently the response from successive governments has largely been individualised and driven by non-Māori worldviews (Tauri & Webb, Citation2012). Instead, the power of Māori worldviews and tikanga, as a “counter-force” to offending (as well as being protective in many ways), needs to be harnessed. “If we could enhance opportunities to more fully immerse our youth in this environment in the most culturally appropriate, meaningful way possible (including involving community supports to reinforce and strengthen knowledge and connections), we would see greater success” (Lambie, Citation2018b, p. 27).

Limitations and future research

The dataset on which this research is based is larger than that of other studies of Indigenous youth with HSBs and the data are considered robust, gathered in a very comprehensive and systematic process by a number of researchers checking and cross-checking all variables. However, one limitation of the dataset, although large and broad-ranging, was that it was collected between 1994 and 2008, meaning recent changes in risk factors – particularly online pornography and the internet – were only nascent in Aotearoa NZ at the time. However, the findings from this study highlight differences among ethnic groups that need to be taken into account when working with Indigenous youth with HSBs. While the possible causes of offending behaviour might have changed, unfortunately the disparities which Indigenous populations experience have not. The importance of addressing their behaviour within the context of their unique cultural needs remains. Currently, there is limited research (both locally and internationally) regarding how exactly the internet and pornography use influence the development of HSBs among adolescents, and whether ethnic differences would be evident. We know that Māori are more affected by the “digital divide”, that includes a lack of access to the internet (Digital Inclusion Research Group, Citation2017), compared to Pākehā. However, it remains unclear as to whether this would have any impact on adolescents accessing internet pornography. Therefore, it is hard to determine what aspects of our findings would be changed and there are no plans (funding) to repeat the intensive data-gathering that was required to establish such a comprehensive dataset. It seems that findings from the current dataset, despite its age, are still useful in giving an idea of the types of backgrounds associated with HSBs, particularly for Indigenous youth in Aotearoa NZ. Furthermore, there is no major evidence to suggest that our results would be dramatically different now, as the negative sequelae of colonisation and social disadvantage remain pernicious.

Another limitation of the current study is that, despite investigating background characteristics, no background protective factors were included in analysis, especially with regards to Māori culture and identity. Future research should prioritise investigation of how factors regarded as protective for Māori hauora, such as connection to whakapapa (geneaology), whānau and Māori identity (Durie, Citation1994), can be protective against the development of HSBs. Treatment that aims to boost engagement with Māori identity in Māori HSBs has not only been found to be effective, but also preferred by rangatahi of this cohort and their whānau (Ape-Esera & Lambie, Citation2019). Related to this limitation is the lack of nuance provided by quantitative data. Behind the results reported, in relation to risk factors, are the voices of rangatahi (both Māori and Pākehā) and their whānau which are not heard. With the knowledge that youth with HSBs are likely to have lived through many adverse experiences, it would be important for future research to seek out qualitative information around these experiences and elaborate on the current contexts of the quantitative data. The quantitative findings, based on such a large dataset, provide useful directions on which to focus future qualitative research.

Recommendations

This study shows that the challenges faced by youth with HSBs in Aotearoa NZ are manifold and are amplified for rangatahi Māori, with this investigation shedding light on some of their complex needs. Furthermore, we can begin to draw conclusions around how professionals working with Māori need to be more responsive to these differentiated needs in treatment and prevention.

Our results support previous recommendations for treatment to be holistic in nature (Durie, Citation1994; Lambie et al., Citation2007; Lim et al., Citation2012). Māori youth with HSBs in the current sample had higher rates of all background risk factors compared with Pākehā. These differences were found at the individual level (substance abuse), whānau level (family violence) and community level (exclusion from school). If treatment of HSB is to be effective for rangatahi Māori, given that they are more likely than Pākehā to have lived through challenges at most environmental levels, treatment must be holistic and comprehensive from the outset. As alluded to earlier, a promising and useful avenue for intervention lies at the whānau level, especially given the risk factors identified in this study are largely embedded within that context; therefore, whanau-based treatment and prevention should be emphasised in addressing the development of HSB among rangatahi Māori. “Whānau Ora” is an approach that supports whānau to realise their health and wellbeing aspirations (Te Puni Kōkiri, Citation2015). A major aspect of its delivery focuses on addressing problems by supporting whānau to access services specific to the problems they are facing. Not only do our results support an approach like this (holistic and family-based) but they may provide insight into the types of services that Whānau Ora might best link with whānau who are trying to treat HSB among rangatahi Māori. The key difference between Whānau Ora and a therapy model such as multi-systemic therapy (Henggeler et al., Citation2009) is that Whānau Ora places culture and the importance of cultural practices at the centre of its Kaupapa (purpose/cause).

Along with this holistic approach is the importance of culturally appropriate treatment for Māori youth with HSBs. Our results did not directly assess the cultural needs of rangatahi; however, previous evidence suggests that the most effective treatment would be informed by a perspective derived from Te Ao Māori, the Māori world (Ape-Esera & Lambie, Citation2019; Lambie et al., Citation2007; Lim et al., Citation2012). Again, this recommendation is not novel nor derived solely from this study’s results. Nevertheless, the current study’s results can re-emphasise this recommendation and perhaps extend its importance to contexts not previously focused on. For example, one of the most significant differences between Māori and Pākehā youth with HSBs, found in this investigation, was in substance abuse rates; treatment for Māori with HSBs should therefore further integrate Māori models of understanding wellbeing that are also applied to substance abuse (e.g. Te Whare Tapa Whā; Ball et al., Citation2022; Durie, Citation1994). Broader risk factors such as school exclusion (and conversely, thriving in education) also require more cultural consideration (e.g. Webber & Macfarlane, Citation2020).

Combining holistic and culturally informed approaches to involving whānau/family, kaiako/staff, and iwi/tribal group can boost healthy engagement with education, whether that be mainstream or Māori-led (Ape-Esera & Lambie, Citation2019; Lambie et al., Citation2007). For services to be able to adequately do this, provisions need to be added for staff cultural support and increased flexibility of standard procedures to allow for more cultural practice in treatment processes, such as pōwhiri (welcome), whakawhanaungatanga (building connections), and engagement with both iwi and hapū (wider family group). Furthermore, increased training for the treatment of broad risk factors (that might not be directly related to the HSB itself), such as substance abuse, should be made a priority when working with Māori youth.

One of the major recommendations that can be drawn from our results is the importance of prevention of HSBs when it comes to Māori. Specifically, our results posit the multiple avenues that prevention efforts can target. As was expected, the sample had higher levels than the general NZ adolescent population of background variables previously associated with the development of HSB (e.g. sexual and physical abuse victimisation, poor school engagement, substance abuse; Seto & Lalumière, Citation2010). Early intervention (given these risk factors are warnings, known to be present in a young person’s life) in the form of culturally appropriate mental health services (e.g. Hamley et al., Citation2022) could avoid the development of HSB in adolescence and therefore negative outcomes for both victims and perpetrators. With Māori HSBs presenting with higher rates of developmental risk factors for HSB, the importance of early intervention for rangatahi Māori cannot be overstated. Prevention through early intervention has been evidenced as critical in the mitigation of adolescent offending more generally (Lambie, Citation2018b; Stringfellow et al., Citation2022) and this is no less critical in the context of Māori with HSBs.

Conclusion

This study aimed to make recommendations regarding treatment and prevention of HSBs in Māori youth, by taking a retrospective look at some of the experiences they have lived through. It was found that, compared with Pākehā youth with HSBs, Māori were more likely to have experienced the risk factors of substance abuse, familial criminality, physical abuse victimisation and family violence. Both Māori and Pākehā had experienced sexual abuse victimisation and school exclusion. Given these findings, previous recommendations that treatment take on a holistic approach are supported. Furthermore, treatment should be informed by a perspective derived from Te Ao Māori if it is to be maximally effective in addressing the risk factors. As the prevalence of risk factors was high, the findings also support the importance of preventative measures. The histories of these young people point to important avenues for prevention of HSBs, to avoid the negative outcomes for both victims and perpetrators. Future research should replicate the current study with newer data, and include qualitative investigation of context and experience. Protective factors for rangatahi Māori should also be explored quantitatively and qualitatively.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the treatment programmes; SAFE, WELLSTOP and STOP and their clients for being a part of this research. The authors acknowledge Dr. Peter Reed who assisted with data analysis. The authors also acknowledge all research assistants who were involved with collection of the data used.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Māori is the collective term for Indigenous people of New Zealand.

2 Aotearoa is the Indigenous name for New Zealand and the combined term “Aotearoa New Zealand” is increasingly used.

3 SAFE network is a community treatment programme working with people with HSB in Aotearoa New Zealand’s largest city.

References

- Adams, D., McKillop, N., Smallbone, S., & McGrath, A. (2019). Developmental and sexual offense onset characteristics of Australian Indigenous and non-Indigenous male youth who sexually offend. Sexual Abuse, 28(1), 958–985. https://doi.org/10.1177/1079063219871575

- Ape-Esera, L., & Lambie, I. (2019). A journey of identity: A rangatahi treatment programme for Māori adolescents who engage in sexually harmful behaviour. New Zealand Journal of Psychology, 48(2), 41–51.

- Ball, J., Crossin, R., Boden, J., Crengle, S., & Edwards, R. (2022). Long-term trends in adolescent alcohol, tobacco and cannabis use and emerging substance use issues in Aotearoa New Zealand. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand, 52(4), 450–471. https://doi.org/10.1080/03036758.2022.2060266

- Baxter, J., Kokua, J., Wells, J. E., McGee, M. A., & Oakley Browne, M. A. (2006). Ethnic comparisons of the 12 month prevalence of mental disorders and treatment contact in Te Rau Hinengaro: The New Zealand Mental Health Survey. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 40(10), 905–913. https://doi.org/10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01910.x

- Bertrand, L. D., MacRae-Krisa, L. D., Costello, M., & Winterdyk, J. (2013). Ethnic diversity and youth offending: An examination of risk and protective factors. International Journal of Child, Youth and Family Studies, 4(1), 166. https://doi.org/10.18357/ijcyfs41201311852

- Bishop, R., Berryman, M., Cavanagh, T., & Teddy, L. (2009). Te Kotahitanga: Addressing educational disparities facing Māori students in New Zealand. Teaching and Teacher Education, 25(5), 734–742. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2009.01.009

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1994). Ecological models of human development. In T. Husen, & T. N. Postlethwaite (Eds.), International encyclopedia of education (pp. 1643–1647). Pergamon Press.

- Burton, D. L. (2003). Male adolescents: Sexual victimization and subsequent sexual abuse. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 20(4), 277–296. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024556909087

- Calder, M. C. (2007). Working with children and young people who sexually abuse taking the field forward. Russell House.

- Clark, T. C., Fleming, T., Bullen, P., Denny, S., Crengle, S., Dyson, B., Fortune, S., Lucassen, M., Peiris-John, R., Robinson, E., Rossen, F., Sheridan, J., Teevale, T., & Utter, J. (2013). Youth’12 overview: The health and wellbeing of New Zealand secondary school students in 2012. The University of Auckland.

- DeLisi, M., Kosloski, A. E., Vaughn, M. G., Caudill, J. W., & Trulson, C. R. (2014). Does childhood sexual abuse victimization translate into juvenile sexual offending? New evidence. Violence and Victims, 29(4), 620–635. https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.VV-D-13-00003

- Department of Corrections NZ. (2007). Over-representation of Māori in the criminal justice system: An exploratory report. https://www.corrections.govt.nz/__data/assets/pdf_file/0014/10715/Over-representation-of-Maori-in-the-criminal-justice-system.pdf.

- Digital Inclusion Research Group. (2017). Digital New Zealanders: The pulse of the nation. A report to MBIE and DIA.

- Durie, M. (1994). Whaiora: Maori health development. Oxford University Press.

- Durie, M. (2001). Mauri ora: The dynamics of Maori health. Oxford University Press.

- Ellison-Loschmann, L., & Pearce, N. (2006). Improving access to health care among New Zealand’s Maori Population. American Journal of Public Health, 96(4), 612. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2005.070680

- Fergusson, D. M., Boden, J. M., & Horwood, L. J. (2008). Exposure to childhood sexual and physical abuse and adjustment in early adulthood. Child Abuse & Neglect, 32(6), 607–619. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.12.018

- Ford, M. E., & Linney, J. A. (1995). Comparative analysis of juvenile sexual offenders, violent nonsexual offenders, and status offenders. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 10(1), 56–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/088626095010001004

- Hackett, S., Masson, H., Balfe, M., & Phillips, J. (2013). Individual, family and abuse characteristics of 700 British child and adolescent sexual abusers. Child Abuse Review, 22(4), 232–245. https://doi.org/10.1002/car.2246

- Hamley, L., Le Grice, J., Greaves, L., Groot, S., Lindsay Latimer, C., Renfrew, L., Parkinson, H., Gillon, A., & Clark, T. C. (2022). Te Tapatoru: A model of whanaungatanga to support rangatahi wellbeing. Kōtuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences Online, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/1177083X.2022.2109492

- Harrelson, M. E., Alexander, A. A., Morais, H. B., & Burkhart, B. R. (2017). The effects of polyvictimization and quality of caregiver attachment on disclosure of illegal sexual behavior. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 26(5), 625–642. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2017.1328474

- Henggeler, S. W., Letourneau, E. J., Chapman, J. E., Borduin, C. M., Schewe, P. A., & McCart, M. R. (2009). Mediators of change for multisystemic therapy with juvenile sex offenders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(3), 451–462. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013971

- Johnson, G. M., & Knight, R. A. (2000). Developmental antecedents of sexual coercion in juvenile sexual offenders. Sexual Abuse, 12(3), 165–178. https://doi.org/10.1177/107906320001200301

- Kirmayer, L. J., & Brass, G. (2016). Addressing global health disparities among Indigenous peoples. The Lancet, 388(10040), 105–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30194-5

- Lambie, I. (2018a). Using evidence to build a better justice system: The challenge of rising prison costs. Office of the Prime Minister’s Chief Science Advisor. www.pmcsa.ac.nz.

- Lambie, I. (2018b). It’s never too early, never too late: A discussion paper on preventing youth offending in New Zealand. Office of the Prime Minister’s Chief Science Advisor. www.pmcsa.ac.nz.

- Lambie, I., Geary, J., Fortune, C., Brown, P., Willingale, J., & Wharemate, R. (2007). Getting it right: An evaluation of New Zealand community treatment programmes for adolescents who sexually offend. http://www.stop.org.nz/main/Publications.

- Lambie, I., McCarthy, J., Dixon, H., & Mortensen, D. (2001). Ten years of adolescent sexual offender treatment in New Zealand: Past practices and future directions. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 8(2), 187–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218710109525019

- Lambie, I., & Seymour, F. (2006). One size does not fit all: Future directions for the treatment of sexually abusive youth in New Zealand. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 12(2), 175–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552600600823647

- Lim, S., Lambie, I., & Cooper, E. (2012). New Zealand youth that sexually offend. Sexual Abuse, 24(5), 459–478. https://doi.org/10.1177/1079063212438923

- Malvaso, C. G., Proeve, M., Delfabbro, P., & Cale, J. (2020). Characteristics of children with problem sexual behaviour and adolescent perpetrators of sexual abuse: A systematic review. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 26(1), 36–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552600.2019.1651914

- McCuish, E. C., Cale, J., & Corrado, R. R. (2017). Abuse experiences of family members, child maltreatment, and the development of sex offending among incarcerated adolescent males: Differences between adolescent sex offenders and adolescent non-sex offenders. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 61(2), 127–149. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X15597492

- Ministry of Health. (2014). Treaty of Waitangi principles. https://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/populations/maori-health/he-korowai-oranga/strengthening-he-korowai-oranga/treaty-waitangi-principles.

- Ministry of Justice. (2009). Child and youth offending statistics in New Zealand: 1992 to 2007.

- Ministry of Justice. (2020). Youth justice indicators. https://www.justice.govt.nz/justice-sector-policy/research-data/justicestatistics/youth-justice-indicators.

- New Zealand Public Health and Disability Act. (2000). https://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/2000/0091/latest/DLM80058.html.

- NZ Police. (2018). Sexual assault and related offences by age group and sex. http://www.police.govt.nz/about-us/publications-statistics/data-and-statistics/policedatanz/unique-offenders-demographics.

- Oliver, L. L., Hall, G. C. N., & Neuhaus, S. M. (1993). A comparison of the personality and background characteristics of adolescent sex offenders and other adolescent offenders. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 20(4), 359–370. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854893020004004

- Oranga Rangatahi. (2018). Rangatahi Māori and Youth Justice: Prepared for Iwi Chairs Forum. https://iwichairs.maori.nz/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/RESEARCH-Rangatahi-Maori-and-Youth-Justice-Oranga-Rangatahi.pdf.

- Oranga Tamariki. (2020). Quarterly report – September 2020. https://www.orangatamariki.govt.nz/about-us/reports-and-releases/quarterlyreport/text-only/.

- Orange, C. (2004). An illustrated history of the Treaty of Waitangi. Bridget Williams Books.

- Rameka, L. (2017). Kia whakatōmuri te haere whakamua: ‘I walk backwards into the future with my eyes fixed on my past’. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 17(4), 387–398. https://doi.org/10.1177/1463949116677923

- Rich, P. (2011). Understanding, assessing, and rehabilitating juvenile sexual offenders. John Wiley & Sons.

- Righthand, S., & Welch, C. (2004). Characteristics of youth who sexually offend. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 13(3-4), 15–32. https://doi.org/10.1300/J070v13n03_02

- Rojas, E., & Gretton, H. (2007). Background, offence characteristics, and criminal outcomes of Aboriginal youth who sexually offend: A closer look at Aboriginal youth intervention needs. Sexual Abuse, 19(3), 257–283. https://doi.org/10.1177/107906320701900306

- SAFE Network Inc. (1998). SAFE adolescent programme staff manual. SAFE Network.

- Seto, M. C., & Lalumière, M. L. (2010). What is so special about male adolescent sexual offending? A review and test of explanations through meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 136(4), 526–575. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019700

- Statistics New Zealand. (2013). Annual Recoded Offences for the latest Fiscal Years (ANZSOC). http://nzdotstat.stats.govt.nz/wbos/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=TABLE CODE7401.

- Statistics New Zealand. (2020). Māori population estimates: At 30 June 2020. https://www.stats.govt.nz/information-releases/maori-population-estimates-at30-june-2020.

- Stringfellow, R., Tauri, J., & Richards, K. (2022). Prevention and early intervention programs for Indigenous young people in Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand. Research Brief 32, May 2022. Indigenous Justice Clearinghouse.

- Tauri, J. M., & Webb, R. A. (2012). Critical appraisal of responses to Māori offending. International Indigenous Policy Journal, 3(4), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.18584/iipj.2012.3.4.5

- Te Puni Kōkiri. (2015). Understanding whānau-centred approaches: Analysis of Phase One Whānau Ora research and monitoring results. Wellington, New Zealand: Te Puni Kōkiri.

- Te Puni Kōkiri. (2017). Understanding family violence: Māori in Aotearoa New Zealand. https://www.tpk.govt.nz/en/a-matou-mohiotanga/health/maori-family-violence-infographic.

- Thom, R. R. M., & Grimes, A. (2022). Land loss and the intergenerational transmission of wellbeing: The experience of iwi in Aotearoa New Zealand. Social Science & Medicine, 296, 114804. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114804

- Van Wijk, A., Vreugdenhil, C., van Horn, J., Vermeiren, R., & Doreleijers, T. A. H. (2007). Incarcerated Dutch juvenile sex offenders compared with non-sex offenders. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 16(2), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1300/J070v16n02_01

- Walker, R. (2004). Ka whawhai tonu mātou: Struggle without end (2nd ed). Penguin.

- Webber, M., & Macfarlane, A. (2020). Mana tangata: The five optimal cultural conditions for Māori student success. Journal of American Indian Education, 59(1), 26–49. https://doi.org/10.5749/jamerindieduc.59.1.0026