ABSTRACT

Research has linked the Dark Tetrad to the perpetration of sexual violence. However, while sexual violence is predominantly perpetrated by those known to the victim, little research has looked at the impact of the Dark Tetrad in the context of intimate relationships. The present study aimed to explore the relationship between the Dark Tetrad, attitudes toward sexual coaxing and sexual coercion, and Rape Myth acceptance, while measuring the effects of relationship. Pearson's r correlations, independent sample t-tests, regressions and mediation analyses were conducted on a sample of N = 461 participants from the general population. Results show a gender difference, with women reporting more lenient attitudes toward coercive or coaxing behaviours, and men presenting more dark traits and endorsing more Rape Myths. Furthermore, relationships were established between sadism, psychopathy, and coercive attitudes. This study expands our understanding of the correlates of sexual violence, enabling the design of prevention programmes.

Practice impact statement

The #MeToo movement has stressed the high prevalence of sexual coercion, its pervasive consequences and lack of research. This paper provides a better insight on the role of Rape Myths and dark traits on sexual coercion. A better understanding of sexual coercion and its nomological network is needed to develop effective prevention and education strategies.

From the dark triad to the dark tetrad

The Dark Triad (Paulhus & Williams, Citation2002) of personality has received growing support as a driving force behind social impairment, delinquency and offending behaviours, increasing predispositions toward utilitarian relationships, lack of perspective, lack of empathy, callousness, and antisocial cognitions (Smith et al., Citation2019). The Dark Triad is composed of three facets: psychopathy, narcissism, and Machiavellianism. Psychopathy is defined by a lack of empathy, superficial charm, and impulsivity (Paulhus & Williams, Citation2002). Recent studies by Patrick and colleagues (Dirslane & Patrick, Citation2017; Evans & Tully, Citation2016) have expanded the conceptualisation of psychopathy to include three distinct constructs: disinhibition, or the inability to restrain behaviours leading to rash decisions; boldness, reflecting a fearless and often dominant personality with little anxiety; and meanness, defined by a lack of empathy and a tendency towards cruelty. Narcissism is defined by an inflated sense of self, entitlement, and lack of regard for others (Paulhus & Williams, Citation2002). Finally, Machiavellianism is characterised by manipulation, a lack of morality and a cynical viewpoint (Jones & Paulhus, Citation2009). Despite their shared core of manipulation and callousness (Smith et al., Citation2019), the dark traits remain distinct entities (Jones & Figueredo, Citation2013).

Research has highlighted the impact of everyday sadism, a distinct but related disorder involving the derivation of pleasure from the suffering of others through control, punishment, and humiliation (Plouffe et al., Citation2017). Sadism has also been linked to the enjoyment of inflicting emotional and physical pain on others (Longpré et al., Citation2018), highlighting its relevance in the context of antisocial behaviour and as a natural extension of the core elements of the Dark Triad. Recognising the complementary nature of everyday sadism to the dark traits, everyday sadism was added to the Dark Triad to form the Dark Tetrad (Paulhus, Citation2014; Plouffe et al., Citation2017).

Sexual violence: a dimensional construct

Sexual violence includes a wide variety of behaviours, ranging from sexual coaxing, sexual harassment, sexual coercion, rape, to sexual homicide (Knight et al., Citation2013; Longpré et al., Citation2020). Traditionally, the focus has been on studying each form of sexual violence as distinct entities, with a focus on severe forms of sexual violence such as sadistic rape (e.g. Reale et al., Citation2017) or sexual homicide (e.g. Stefanska et al., Citation2020). However, while from a criminal justice perspective these forms of violence are considered quantitatively different, several studies have supported that they are part of a continuum of sexual violence, named the Agonistic Continuum by Knight and colleagues (Knight et al., Citation2013; Longpré et al., Citation2020). The continuum ranges from sexual harassment at its lower end, escalating to sexual coercion and rape, and at its higher end, sexual sadism, and sexual murder (Knight et al., Citation2013). The presence of a continuum of sexual violence has been supported by several studies across populations and genders (e.g. Balcioglu et al., Citation2023, Longpré et al., Citation2019; Reale et al., Citation2017; Trottier et al., Citation2021).

Sexual coaxing and sexual coercion

Sexual assault remains a pressing issue, with a significant increase in reported offences in recent years (Office for National Statistics, Citation2022). Tactics used by perpetrators can be divided into sexual coaxing and sexual coercion. Sexual coaxing refers to the use of soft tactics, such as charm, flattery, and caresses (Camilleri et al., Citation2009). Sexual coercion is the use of aggressive tactics, including the use of physical violence, threats, deception, cultural expectations, and economic circumstances (Camilleri et al., Citation2009).

Studies from the United States and other western countries suggest that between 20 and 35% of women and between 5 and 10% of men have experienced sexual coercion at some point in their life (Heis et al., Citation1995). Despite its perceived lesser severity compared to rape, sexual coercion can have a detrimental impact on mental and physical well-being; leading to higher levels of anxiety, depression, and substance abuse (Brown et al., Citation2009). Furthermore, self-report studies have revealed that the perpetration of sexual coercion is not exclusive to women (Longpré et al., Citation2022; Saravia et al., Citation2023; Trottier et al., Citation2021). While research usually supports that, in general, men make significantly more persistent attempts (Bonneville & Trottier, Citation2021) and use a greater number of coercive behaviours (Finkelstein, Citation2014), up to 41% of women have used coercive tactics (Benbouriche & Parent, Citation2018; Parent et al., Citation2018). These findings underscore the importance of studying sexual coercion across genders and suggest that gender differences are not as marked as previously thought, particularly in the lower part of the continuum.

The dark tetrad, sexual coaxing, and sexual coercion

It is theorised that the underlying manipulative tactics of coercive behaviours interact with the callous and deceptive core of the dark traits (Jones & Figueredo, Citation2013). Psychopathic traits are strongly linked to coercive behaviours (Knight & Sims-Knight, Citation2003; Krstic et al., Citation2018), including manipulation, physical restraint and blocking attempts at retreat (Jones & Olderbak, Citation2014; Prusik et al., Citation2021). Individuals presenting high levels of psychopathic traits may not necessarily have a preference for coercion, but the impulsive nature of psychopathy means they have limited patience for coaxing strategies (Knight & Sims-Knight, Citation2003; Longpré et al., Citation2020). Narcissism is associated with a preference for coaxing over coercion (Jones & Olderbak, Citation2014; Prusik et al., Citation2021). However, if coaxing tactics fail, individuals high on narcissism can feel entitled and might turn to coercion to fulfil their needs (Zeigler-Hill et al., Citation2016). Narcissism has also been associated with the use of physical force (Finkelstein, Citation2014). Machiavellianism is usually negatively associated with sexual coercion (Brewer et al., Citation2019; Jones & de Roos, Citation2016). This may be attributed to the low level of impulsivity and flexible morality of Machiavellianism (Jones & Paulhus, Citation2009), which are not associated with short-term sexual behaviours (Jones & de Roos, Citation2016) or harassment (Brewer et al., Citation2019). Sadism is a strong predictor of coercion (Knight & Sims-Knight, Citation2003; Longpré et al., Citation2018), but its link to sexual coaxing is understudied (Koscielska et al., Citation2020).

Collectively, these findings highlight the unique contributions of each of the dark traits to sexual violence. The current study seeks to bridge the gap in the literature by examining the interaction between all Dark Tetrad traits, the lower end of the spectrum of sexual violence, and rape-supportive cognitions within a unified research design. By integrating these elements into a single research design, this study seeks to uncover the nuanced ways in which these dark traits interact with each other and contribute to the endorsement of rape-supportive cognitions and lenient attitudes toward sexually coaxing or coercive behaviours.

Rape myth acceptance

It is estimated that less than 1/5 of adults who experienced rape or sexual assault by penetration in the UK reported it to the police (Office for National Statistics, Citation2022). A substantial number of victims mentioned that they did not report the assault due to a fear that the police would not believe their accounts (de Roos & Jones, Citation2020b). Research has revealed that being accused of lying, the use of stereotyping, and victim-blaming attitudes contribute to this underreporting of sexual assaults (de Roos & Jones, Citation2020a). Victim-blaming attitudes are used to minimise the severity of the attack or to shift the responsibility from the rapist to the victim. These attitudes are defined as Rape Myths acceptance (RMA: Bonneville & Trottier, Citation2021).

Previous studies have found gender differences in the endorsement of RMA (Bonneville & Trottier, Citation2021; Longpré et al., Citation2022; Saravia et al., Citation2023), with men more likely to blame victims of sexual violence and harbour suspicions of disclosures (de Roos & Jones, Citation2020b). Moreover, men have shown a greater RMA than women, especially alcohol-related RMA (Bonneville & Trottier, Citation2021). The Dark Tetrad influences RMA; higher levels of psychopathy, narcissism, and Machiavellianism are correlated with greater RMA among men (Jonsson et al., Citation2017). Additionally, everyday sadism has been significantly correlated to RMA and its subscales, which significantly increases the risk of sexually coercive behaviours (Longpré et al., Citation2022). While some women endorse victim-blaming attitudes, their occurrence is mostly moderated by the presence of the dark traits, especially psychopathy (Brewer et al., Citation2019).

Victim-perpetrator relationship

The majority of rapes are committed by someone known to the victim (Home Office, Citation2013; Struckman-Johnson et al., Citation2003), with over half of victims assaulted by a previous or current romantic partner (Home Office, Citation2013; Office for National Statistics, Citation2022). The severity of the assault is linked to the relationship between the victim and perpetrator, with more severe offences being committed by an intimate partner (Home Office, Citation2013).

Intimate partner sexual violence (IPSV) is a prevalent form of sexual violence and a common component of intimate partner violence (IPV). IPSV has been linked to elevated levels of mental illness, suicidality, and homicide (Barker et al., Citation2019). Some studies have shown that the Dark Tetrad is correlated to higher perpetration of IPV (Carton & Egan, Citation2017; Kiire, Citation2017; Pineda et al., Citation2023) and IPSV (Hoffmann & Verona, Citation2019; Kiire, Citation2017), especially psychopathic traits (Kiire, Citation2017). However, existing research exploring the influence of the dark traits on IPV primarily focuses on the psychological and physical (non-sexual violence) dimensions of IPV rather than IPSV (Brewer et al., Citation2019; Tetreault et al., Citation2021).

Short-term relationships and sexual promiscuity are significant risk factors for sexual violence (Brouillette-Alarie et al., Citation2022; Knight & Guay, Citation2018), and have been associated with sadism and psychopathy in forensic samples (Krstic et al., Citation2018). The dark traits have been associated with a preference for short-term low-commitment mating styles, such as one-night stands (Jonason et al., Citation2012), specifically for psychopathy and sadism (Tsoukas & March, Citation2018). This preference can be explained, in part, by the impulsiveness and social impairment characteristics of the traits. In contrast, individuals high on narcissism often have longer relationships, although these are typically characterised as abusive (Jones & de Roos, Citation2016; Tsoukas & March, Citation2018). Additionally, Machiavellianism lacks impulsiveness (Jones & Paulhus, Citation2014) and short-term thinking and is typically associated with long-term but abusive relationships (Jones & de Roos, Citation2016). While several studies, such as those by Jones and Olderbak (Citation2014) and Koscielska et al. (Citation2020), have investigated the impact of relationship status on sexual violence and dark traits using scenarios, these investigations primarily concentrated on the status of the relationship without considering its duration. This suggests a gap in our understanding of how the length of a relationship might influence the dynamics and risk of sexual violence in the context of a relationship.

Aims

Previous research has indicated that the dark traits have an influence on RMA and have been linked to sexually coercive behaviours. Previous studies have also revealed that sexual violence is primarily perpetrated by those known to the victim, highlighting the importance of studying the impact of relationships. However, little research has studied lower levels of sexual violence, such as sexual coaxing and sexual coercion, and its nomological network.

Therefore, the present research aims to explore the influence of the Dark Tetrad on the attitudes toward sexual coaxing and sexual coercion, and endorsement of RMA. The impact of intimate relationships will also be explored. Based on previous study, it is hypothesised that:

H1: Those presenting more dark traits, especially psychopathy and sadism, will have a more lenient attitude toward sexually coercive or coaxing behaviours and present greater RMA.

H2: Those currently in relationships and those who had longer previous (or current) relationships will have a more lenient attitude toward sexually coaxing or coercive behaviours, and will endorse more RMA.

H3: Men will endorse more RMA, present higher levels of dark traits, and will have a more lenient attitude toward sexually coaxing or coercive behaviours when compared to women.

Methods

Participants

The initial sample was composed of N = 554 participants, n = 72 were recruited through Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk), and n = 482 participants came from social media platforms, such as LinkedIn, Twitter and Facebook. Participants who had skipped more than one questionnaire (n = 83) were removed from the data set. Finally, another ten participants who selected “non-binary” and “prefer not to say” on gender were removed from the data set as the sample size was too small for the analyses. The final number of participants was N = 461.

The majority of participants were women (n = 377, 81.2%) and Caucasian (n = 391, 84.8%). The mean age of participants was 31.21 years (SD = 9.66; Ranges 18-77). Participants were predominantly heterosexual (n = 347, 75.6%), and were married or living with a partner (n = 230, 49.9%) or in a relationship (n = 125, 27.1%). The length of the participant's relationships ranged from 0 to 50.5 years (Mean = 6.5, SD = 7.58). The full demographics of the sample can be found in .

Table 1. Demographics.

Procedure

The current study received ethical approval from University of Roehampton in England. Due to the pandemic, the survey was presented to participants through Qualtrics, an online survey platform. The use of a third party prevented direct contact between participants and researchers, allowing for complete anonymity. Upon following the link, participants were directed to a consent form that they were asked to read and accept. The consent form warned of sensitive topics, right to withdraw, anonymity as well as confidentiality of the survey. At the end, participants were given mental health and victim support information.

The survey was advertised on various social media platforms, and on MTurk, a crowdsourcing website that allows researchers to find willing participants online in exchange for monetary compensation. The survey was closed after 2 months, and participants recruited during this period were used for the analyses. There was no special requirement placed on participants in terms of gender, ethnicity, education level, or sexual orientation. The current study only required participants to be over the age of 18.

Measures

For the purpose of this study, six measures and a demographic questionnaire were used. For each scale, the total score was used in the analyses.

Demographic Questionnaire. Participants were asked to provide their age, gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and education level. The participants’ relationship status and length of relationship were also collected.

Triarchic Psychopathy Measure (TriPM; Evans & Tully, Citation2016). The TriPM is a 58-item scale that measures meanness, boldness, and disinhibition subtraits of psychopathy. All subscales are scored on a 4-point Likert-style scale (1-True, 2 – Somewhat True, 3 – Somewhat False, 4 – False). The meanness subscale is composed of 19 items, and a higher score on this scale indicates a higher likelihood to be mean. An example of an item is “I do not care who I hurt to get what I want”. The boldness scale is composed of 19 items, and a higher score on this scale indicates a higher likelihood of fearless dominance. An example of an item is “I have a knack for influencing people”. Finally, the disinhibition subscale is composed of 20 items, and a lower score on this scale indicates a higher likelihood to be disinhibited. An example of an item is “I have missed work without bothering to call in”. Strong internal reliability was found in the current study; the scale overall had a Cronbach alpha of .89, with the subscales reporting an alpha of .89 for meanness, .79 for boldness and .87 for disinhibition.

Narcissistic Personality Inventory – 16 (NPI-16; Ames et al., Citation2006). The NPI-16 is a 16-item scale that measures narcissistic inclinations and is the short form of the 40-item scale (Raskin & Hall, Citation1979). Participants were presented with pairs of statements and must choose the statement that best relates to them. An example of a pair of items is “I really like to be the centre of attention vs. It makes me uncomfortable to be the centre of attention”. A higher score on this scale indicates a higher likelihood of narcissistic inclination. In the current study, the Cronbach alpha was of .83.

Machiavellianism Personality Scale (MACH-IV; Christie & Geis, Citation1970). The MACH-IV is a 20-item scale that measures Machiavellianism and its subcomponents; manipulative tactics, cynical views and attitudes towards human nature, and pragmatic morality (Jones & Paulhus, Citation2009). Items are on a 5-point Likert-style scale (1-Definitely False, 2 – Possibly False, 3 – Not Sure, 4 – Possibly True, 5 – Definitively True). An example of an item is “People won't work hard unless they're forced to do so”. A higher score on this scale indicates a higher likelihood of Machiavellian inclination. The Cronbach alpha was of .64.

Short Sadistic Impulse Scale (SSIS; O'Meara et al., Citation2011). The SSIS is a 10-item scale that measures participants’ sadistic tendencies and the propensity to be cruel to others. Items are scored on a 4-point Likert-style scale (1-True, 2 – Somewhat True, 3 – Somewhat False, 4 – False). An example of an item is “I have hurt people for my own enjoyment”. A lower score on this scale indicates a higher likelihood of sadistic tendencies. The Cronbach alpha was of .90.

Updated Illinois Rape Myth Acceptance Scale (IRMA; McMahon & Farmer, Citation2011). The IRMA is a 22-item scale derived from the 45-item RMA scale (Payne et al., Citation1999), that measures harmful beliefs about rape that are used to move the blame from the perpetrators to the victim. This scale has four subscales: (1) She asked for it, (2) He didn't mean to, (3) It wasn't really rape, and (4) She lied. Items are scored on a 4-point Likert-style scale (1 – Strongly Agree, 2 – Agree, 3 – Disagree, 4 – Strongly Disagree). An example of an item is, “If a girl is raped while she is drunk, she is at least somewhat responsible for letting things get out of hand”. A lower score on this scale indicates a higher RMA. In the current study, the Cronbach alpha was of .96.

Tactics to Obtain Sex Scale (TOSS; Camilleri et al., Citation2009). The TOSS is a 31-item scale that measures participants’ perceived effectiveness and the likelihood of committing sexually coercive or coaxing behaviours with a sexual partner. The 31 items are split into two subscales COAX (12 items related to soft tactics, such as caresses) and COERCE (19 items relating to tricks and force). All items are scored on a 5-point Likert-style scale (1 – Definitely Not, 2 – Unlikely, 3 – Maybe, 4 – Probably, 5 – Definitely). Participants were asked to rate how effective each of the 31 items would be in persuading a sexual partner into having sex, followed by rating each item on how likely the participant would be to use the tactic themselves. Examples of items include “Wait until he/she is sleeping” and “Threaten to leave”. A total score was calculated, measuring COAX and COERCE. In the current study, the Cronbach alpha was of .96.

Analyses

Power analyses, using G*Power software, were conducted to assess the sample size, and revealed that it was sufficient to uncover medium effect size across analyses. Data was normally distributed, with skewness and kurtosis values ranging between – 2 and +2. Therefore, parametric analyses were conducted using SPSS version 26. At a bivariate level, firstly, Student’s t-tests were conducted to assess the impact of gender (Women/ Men) on the score of each scale. Secondly, Pearson’s moment correlations were conducted to assess the relationship between each scale. Finally, at a multivariate level, regressions and mediation analyses were performed using Hayes’ Process Macro v3.3 with SPSS version 26.

Results

Independent samples T-tests

First, independent sample t-tests were conducted to identify gender differences across measures. Results are presented in . A significant difference was found on the meanness (t(92.91) = 9.78, p < . 001), disinhibition (t(103.56) = 6.95, p < .001) and boldness sub-scales (t(157.28) = 5.00, p < .001), with men scoring lower than women. Scoring lower on these subscales indicates that a person is presenting more traits. Furthermore, significant differences were found on narcissism (t(99.62) = 9.45, p < .001), Machiavellianism (t(145.10) = −6.43, p < .001) and sadism scales (t(94.28) = 8.82, p < .001), with men presenting more narcissistic tendencies, higher Machiavellianism inclinations and sadistic tendencies. There was a significant difference in the RMA, with men scoring lower than women on the IRMA (t(88) = 9.01, p < .001), indicating greater acceptance. Furthermore, a breakdown of the IRMA revealed that a significantly greater RMA among men was also found on all four subscales. Finally, a significant difference was found on the TOSS scale, with women reporting a more lenient attitude toward sexually coaxing or coercive behaviours (t(93.12) = 8.20, p < .001) than men.

Table 2. Results of independent-sample t-t analysis between gender and scales.

Pearson correlation coefficient

Secondly, Pearson correlations were conducted and are presented in . The meanness sub-scale showed a strong and positive correlation with RMA (r = .73, p < .001) and a more lenient attitude toward sexually coaxing or coercive behaviours (r = .51, p < .001). Similarly, the disinhibition subscale was correlated with RMA (r = .57, p < .001) and a more lenient attitude toward sexually coaxing or coercive behaviours (r = .47, p < .001). Finally, correlations were found between boldness, RMA (r = .11, p = .03) and a more lenient attitude toward sexually coaxing or coercive behaviours (r = .12, p = .02). Narcissism showed a moderately strong positive correlation with RMA (r = .56, p < .001) and a more lenient attitude toward sexually coaxing or coercive behaviours (r = .44, p < .001). Finally, sadism was strongly and positively correlated with RMA (r = .74, p < .001), particularly the “she asked for it” (r = .74, p < .001) and “it wasn’t rape” (r = .76, p < .001) subscales. Sadism also shared a strong and positive correlation with a more lenient attitude toward sexually coaxing or coercive behaviours (r = .56, p < .001).

Table 3. Pearson Correlation between Scales (Total Score).

Multiple linear regressions

Multiple linear regressions were conducted to assess which variables predicted a more lenient attitude toward sexually coaxing behaviours, coercive behaviours and RMA. Predicting variables used in the analysis were Gender (Men = 1), relationship status (In a relationship = 1), relationship length, sadism, Machiavellianism, narcissism, as well as meanness, boldness, and disinhibition subtraits of psychopathy.

The first regression model indicates that Machiavellianism, β = −.071, t(252) = −1.001, p = .048; boldness, β = .22, t(252) = 3.04, p = .003; meanness, β = .44, t(252) = 3.81, p = .001; and disinhibition, β = .36, t(252) = 3.82, p = .001, significantly predicted a more lenient attitude toward sexually coaxing behaviour. These variables explained a significant proportion of variance in coaxing, R2 = .496, F(10, 252) = 2.69, p = 0.004. The second regression model indicates that sadism, β = .35, t(252) = 5.01, p = .001; narcissism, β = .12, t(252) = 1.780, p = .046; and meanness, β = .21, t(252) = 2.42, p = .016, significantly predicted a more lenient attitude toward sexually coercive behaviour. Boldness and disinhibition were marginally significant at respectively p = .062 and p = .068. These variables explained a significant proportion of variance within coercion, R2 = .51, F(10, 252) = 25.98, p = .001. The third regression model indicates that sadism, β = .392, t(252) = 6.23, p = .001; Machiavellianism, β = .03, t(252) = .723, p = .047; narcissism, β = .12, t(252) = 1.96, p = .050; boldness, β = .09, t(252) = 1.800, p = .043; and meanness, β = .354, t(252) = 4.725, p = .001, significantly predicted more RMA. These variables explained a significant proportion of variance in RMA, R2 = .615, F(10, 252) = 45.11, p = 0.001. Full results are presented in .

Table 4. Multiple Linear Regression with Gender, Relationship Status, Relationship Length & Dark Traits Predicting Sexual Coaxing & Coercion.

Mediation

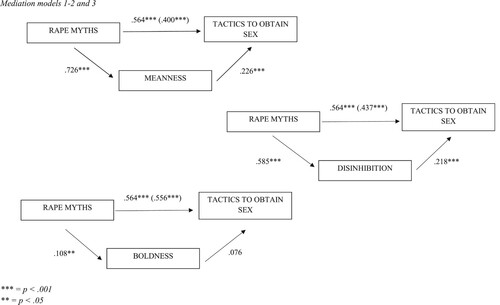

Mediation Model 1. In the first model, the relationship between meanness, RMA, and lenient attitudes toward sexually coaxing or coercive behaviours (TOSS total score) was tested (See ). The path (direct effect) between RMA and TOSS total score was positive and statistically significant (b = .400, s.e. = .180, p < .001). The path (direct effect) between RMA and meanness was positive and statistically significant (b = .726, s.e. = .026, p < .001). Additionally, the path (direct effect) between meanness and TOSS total score was positive and statistically significant (b = .226, s.e. = .277, p < .001). The indirect effect (IE = .164) was statistically significant (95% CI [.030, .303]). The full model explained a significant increase in variance of TOSS total score ΔR2 = .343, F(329) = 85.66, p < .001.

Mediation Model 2. In the second mediation model, the relationship between disinhibition, RMA, and TOSS total score was tested (See ). The path (direct effect) between RMA and TOSS total score was positive and statistically significant (b = .437, s.e. = .160, p < .001). The path (direct effect) between RMA and disinhibition was positive and statistically significant (b = .585, s.e. = .032, p < .001). Additionally, the path (direct effect) between disinhibition and TOSS total score was positive and statistically significant (b = .218, s.e. = .222, p < .001). The indirect effect (IE = .127) was statistically significant (95% CI [.049, .208]). The full model explained a significant increase in variance of TOSS total score ΔR2 = .350, F(329) = 88.37, p < .001.

Mediation Model 3. In the third mediation model, the relationship between boldness, RMA, and TOSS total score was tested (See ). The path (direct effect) between RMA and TOSS total score was positive and statistically significant (b = .556, s.e. = .133, p < .001). The path (direct effect) between RMA and boldness was positive and statistically significant (b = .108, s.e. = .031, p = .049). However, the path (direct effect) between boldness and TOSS total score was not significant (b = .076, s.e. = .233, p = .098). The indirect effect (IE = .608) was not statistically significant (95% CI [−.002, .022]). The full model explained a significant increase in variance of TOSS total score ΔR2 = .324, F(329) = 78.83, p < .001.

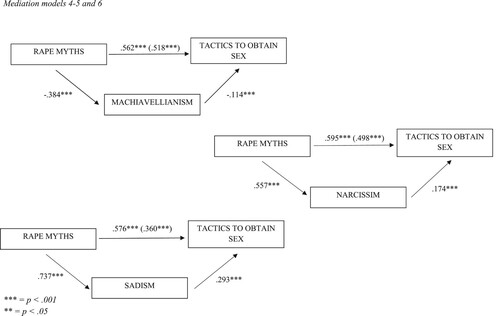

Mediation Model 4. In the fourth mediation model, the relationship between Machiavellianism, RMA, and TOSS total score was tested (See ). The path (direct effect) between RMA and TOSS was positive and statistically significant (b = .518, s.e. = .016, p < .001). The path (direct effect) between RMA and Machiavellianism was negative and statistically significant (b = −.384, s.e. = .032, p < .001). The path (direct effect) between Machiavellianism and TOSS was negative and statistically significant (b = −.114, s.e. = .231, p < .001). The indirect effect (IE = .043) was statistically significant (95% CI [.006, .086]). The full model explained a significant increase in variance of TOSS total score ΔR2 = .327, F(330) = 80.04, p < .001.

Mediation Model 5. In the fifth mediation model, the relationship between narcissism, RMA, and TOSS total score was tested (See ). The path (direct effect) between RMA and TOSS total score was positive and statistically significant (b = .498, s.e. = .154, p < .001). The path (direct effect) between RMA and narcissism was positive and statistically significant (b = .557, s.e. = .012, p < .001). Additionally, the path (direct effect) between narcissism and TOSS total score was positive and statistically significant (b = .174, s.e. = .599, p < .001). The indirect effect (IE = .097) was statistically significant (95% CI [.026, .175]). The full model explained a significant increase in variance of TOSS total score ΔR2 = .375, F(335) = 100.33, p < .001.

Mediation Model 6. In the sixth mediation model, the relationship between sadism, RMA, and TOSS total score was tested (See ). The path (direct effect) between RMA and TOSS total score was positive and statistically significant (b = .360, s.e. = .188, p < .001). The path (direct effect) between RMA and sadism was positive and statistically significant (b = .737, s.e. = .017, p < .001). Additionally, the path (direct effect) between sadism and TOSS total score was positive and statistically significant (b = .293, s.e. = .415, p < .001). The indirect effect (IE = .216) was statistically significant (95% CI [.087, .345]). The full model explained a significant increase in variance of TOSS total score ΔR2 = .371, F(338) = 99.73, p < .001.

Discussion

Overview

The aim of the present study was to explore the relationship between RMA, the dark traits, and the attitudes toward sexual coaxing and sexual coercion. The impact of gender and relationship was also examined. Analyses revealed that men have greater RMA, but women endorsed a more lenient attitude toward sexual coaxing and sexual coercion. Correlation analyses revealed a significant relationship between psychopathy, narcissism, sadism, RMA, and a more lenient attitude toward sexually coaxing or coercive behaviours.

Regression analyses revealed that neither current relationship status nor relationship length were significant predictors of a more lenient attitude toward sexually coaxing or coercive behaviours, or higher RMA. Mediation analysis revealed an interaction between RMA, dark traits (psychopathy [i.e. meanness and disinhibition], narcissism, Machiavellianism, and sadism), and a more lenient attitude toward sexually coaxing or coercive behaviours. These findings have implications for our understanding of the Dark Tetrad and sexual coercion and future research direction.

Implications

Understanding of the dark tetrad and its correlates

Analyses revealed that the relationship between RMA and a more lenient attitude toward sexually coaxing or coercive behaviours was mediated by meanness, disinhibition, narcissism, and sadism. It is important to note that similar to the high concordance between fantasy and behaviour (de Roos et al., Citation2024), studies have shown that perception, attitudes, and behaviour are highly intertwined (Chartrand et al., Citation2006). RMA has been linked with hookup culture (Reling et al., Citation2021), objectification of women (Seabrook et al., Citation2019), more lenient perceptions of harassment (Longpré et al., Citation2022; Saravia et al., Citation2023), and a greater likelihood of committing sexually violent behaviours (Trottier et al., Citation2019). A recent study has revealed the importance of the dark traits as a risk factor for engaging in potentially illegal sexual behaviours (de Roos et al., Citation2024). However, this relationship is more complex, and our results support that the relationship between cognitions and behaviours is mediated by external correlates, such as personality traits. These results are consistent with the previous literature and support the first hypothesis of this study. Even at a subclinical level, the dark traits can negatively influence perception (e.g. Longpré et al., Citation2022), attitudes (e.g. Szabó et al., Citation2023), and behaviours (e.g. Tachmetzidi Papoutsi & Longpré, Citation2022), which in turn can influence each other. While previous studies have looked at the unique contribution of a specific dark trait, or the impact of the dark traits on different outcomes related to sexual violence, the current study focuses on the interaction between all dark traits, rape-supportive cognitions, and attitudes toward sexually violent behaviours in one research design, which makes a unique contribution to the existing literature.

Previous studies have shown that a lack of perspective, a component of psychopathy and sadism, has been associated with victim-blaming (Gravelin et al., Citation2019) and sexual violence (de Roos & Jones, Citation2020a). Furthermore, the meanness and disinhibition components have been associated with sexual violence, sexual sadism, and a general disregard for others’ limits (Krstic et al., Citation2018). Sadism and meanness have shared variance through the propensity to be mean and cruel toward others (Longpré et al., Citation2018). While sadism and psychopathy are two different constructs (Krstic et al., Citation2018), the strong correlation between both scales raised some concerns, and more research should be conducted to see if these two measures are measuring similar latent traits and how they interact with each other (Blötner & Mokros, Citation2023). Alternatively, Machiavellianism was negatively correlated with a more lenient attitude toward coaxing or coercive behaviours and RMA, and negatively mediated the relationship. This follows previous findings that highlighted that individuals high in Machiavellianism are usually less impulsive and have a flexible morality, which is not associated with short-term sexual behaviours (Jones & de Roos, Citation2016). Furthermore, they are risk-averse and consider the cost–benefit of their actions in a manner the other dark traits do not (de Roos et al., Citation2024). This might explain why a higher level of Machiavellianism, unlike other dark traits, was not associated with a more lenient attitude toward sexually coaxing or coercive behaviours.

The current research solidifies our understanding of the dark traits and their potential contribution to sexual violence. Whilst prevention programmes cannot ethically specifically target individuals presenting more dark traits, our results can guide the tailoring of prevention programmes to reduce sexual violence by addressing specific risk factors, such as others’ point of view (i.e. lack of perspective) and psychosexual education (i.e. RMA, sexual education, and egalitarian relationships). Research shows that experience-based interventions, which involve inserting oneself in another's position through mentalization, role play, and experiments, significantly increase empathy and positive outcomes for a particular situation (Wilkes et al., Citation2002). These interventions have previously been shown to increase empathy in sex offenders towards their victims. While covering these elements may have a limited impact on those committing severe sexual violence (e.g. rape), the implementation of prevention aiming specifically towards reducing the negative outcomes of dark traits may be beneficial in reducing sexual violence or reducing lenient attitudes toward sexually coaxing or coercive behaviours.

Gender

This study also aimed to assess the effect of gender on RMA and lenient attitudes toward sexually coaxing or coercive behaviours. Our results revealed that women had a more lenient attitude toward sexually coaxing or coercive behaviours and reported a greater variety of sexually coercive tactics than men, but men presented a greater RMA. This contradicts, in part, the hypothesis that men would have more lenient attitudes toward sexually coaxing or coercive behaviours and endorse more RMA. Research and official data have consistently shown that the majority of sexual violence is committed by men (Home Office, Citation2013). However, previous studies have also shown that sexual violence, at the lower end of the spectrum, is also prevalent among women (e.g. Bonneville & Trottier, Citation2021; Longpré et al., Citation2022; Saravia et al., Citation2023; Trottier et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, Parent and colleagues (Benbouriche & Parent, Citation2018; Parent et al., Citation2018; Parent et al., Citation2014) found a higher prevalence of coercion among women than men in a sample of highly educated participants, which is also the case in our sample. Self-report surveys reveal that between 35 and 58% of men have been victims of sexual coercion by a woman (Benbouriche & Parent, Citation2018). It is important to note that the TOSS measures in part the use of soft tactics and manipulations, which might have led to a more lenient attitude toward sexually coaxing or coercive behaviours among women. Therefore, while a majority of sexual violence located on the upper end of the spectrum is committed by men, several studies measuring the lower end of the spectrum of sexual violence support that an important proportion of women use coaxing and coercive behaviours.

Previous studies have shown that the inclusion of violence is an important threshold, with men committing more severe sexually violent behaviours than women (Longpré et al., Citation2019). However, recent findings suggest that men's sexual victimisation is understudied and underreported (Depraetere et al., Citation2020). Although there are some limitations, our findings support the idea that women might have more lenient attitudes toward sexually coaxing or coercive behaviours than generally accepted, at least for the lower end of the spectrum, and effective prevention programmes should not be led by stereotypical perceptions of sexual violence (Depraetere et al., Citation2020). While recognizing women and girls’ over-representation among victims of sexual violence, research supports the fact women do perpetrate sexual violence, and prevention programmes should also include men's sexual victimisation.

The lenient attitude of sexually coaxing or coercive behaviours among women might also be a result of the current climate. In the era of #MeToo, men's sexual violence is being extensively discussed, and famous men are being named, arrested, and/or convicted (de Roos & Jones, Citation2020a). This, in combination with the emotive discussions on women's safety following shocking cases, such as the kidnapping-rape-murder of Sarah Everard by a London Metropolitan Police Constable in 2021, has led to a rallying cry of “not all men”. Men from the general population have been left scrambling to separate themselves from the idea that all men are abusers and rapists. Whether intentional or unconscious, this reaction could have been reflected in the study, resulting in men underreporting their attitudes toward sexually coaxing or coercive behaviours. The “not all men” stance is congruent with RMA by focusing on the defending men, minimising, and distracting from conversations of sexual violence, which could explain the results of greater RMA in men. This presents problems for future research, as eliminating this bias would be difficult. However, it also provides an interesting area to further research on whether men are conscious of the change in their response and whether consequences and an atmosphere of accountability change participants’ attitudes and endorsements of sexual coercion. Preliminary results indicate that this might be the case (i.e. de Roos & Jones, Citation2020b).

Victim-perpetrator relationship

Research and official data have revealed that sexual violence is more likely to be committed by someone close to the victim, including intimate partners, with over half assaulted by a romantic partner (Home Office, Citation2013). While previous studies have linked the dark traits to sexual harassment and RMA (e.g. Jones & Olderbak, Citation2014; Longpré et al., Citation2022; Saravia et al., Citation2023), the current study also aimed to look at the impact of intimate relationships. Neither relationship status nor relationship length was found to be associated with sexual coaxing, coercion, or RMA, diverging from the study’s hypothesis. The lack of significant relationship found in this study potentially indicates that while the dark traits may be a predictor of sexual violence, its impact might not differ across relationship types. However, it is important to note that our participants were in majority highly educated (i.e. undergraduate degree; n = 344; 75.6%), women (n = 377; 81.8%), and in a relationship (n = 355; 77%). Therefore, these results need to be replicated in samples that are more diverse.

Further reflection on this lack of significant relationship might also be understood by the association between the Dark Tetrad and short-term mating such as one-night stands (Jonason et al., Citation2012). For example, higher levels of psychopathic traits and sadism have been linked to short-term relationships (Tsoukas & March, Citation2018) over longer commitments that intimate relationships require. Furthermore, individuals who score higher on the dark traits show more undesirable characteristics (Jones & Paulhus, Citation2014). This implies that individuals presenting more dark traits are less likely to seek out or maintain a relationship and, therefore, are less likely to contribute to intimate sexual violence. This indicates that the relationship between dark traits and sexual violence in a relationship context is more complex, and other variables should be included in future models, such as control mechanisms and other undesirable characteristics.

Limitations

This study is not without limitations. First, the sample used in this study lacks a full representation of the general population. The sample was predominantly composed of women, with only 18.2% of the sample being men. This is not reflective of the 51%−49% gender split in the UK (Office of National Statistics, Citation2022). This gender imbalance can be explained, we think, by two aspects. First, the survey was conducted online during the pandemic, and data revealed that women were more impacted than men by redundancy and economic inactivity during this period of time. As such, it can be hypothesised that they were more active online. Secondly, our participants were overall highly educated, with 75.6% having at least an undergraduate degree. Women make up more than 57% of higher education, and as a by-product of the higher level of education found in our sample, it might also explain in part why our sample was composed of more women than men. Despite this, our findings are overall consistent with previous literature, revealing an impact of gender on the endorsement of RMA and dark traits. Moreover, the majority of previous research focuses on male perpetration, the sizable women's representation in the current study opens the door to explore women's perpetration of sexual coercion. Future research should also explore possible differences between binary and non-binary identifying groups. Moving forward, studies should aim to increase diversity of participants to reflect the general population.

Furthermore, a second limitation stemmed from the sample under scrutiny as self-reported data was collected from the general population. The results of the current study might differ significantly if conducted with an offending population, where the traits would likely be more pronounced and coercive behaviours more prevalent and severe. However, only 15% of rapes are reported to the police, with as low as 1.3% of rape cases leading to a suspect being charged (Home Office, Citation2013). Therefore, sexually violent individuals are likely to be found in the general population, meaning the sample used in the current study is appropriate. Furthermore, the reliance on self-reported data in relation to sensitive topics might have partially impacted the results. Responses may have been influenced by a need to appear socially desirable, leading to underreporting coercive behaviours. Safeguards were used to protect against bias, including controlling for social desirability, voluntary participation, and complete anonymity, analysing completion time, and excluding respondents who did not devote sufficient time to the survey, which has been shown to be effective in previous study. Furthermore, most of our findings are consistent with previous literature, revealing good convergences across the study.

Conclusion

The aim of the present study was to explore the influence of the Dark Tetrad on RMA, attitudes toward coaxing or coercive behaviours, with a focus on the impact of intimate relationships. Overall, men show greater RMA and more dark traits. Mediation analyses revealed that the relationship between RMA and a lenient attitude toward sexually coercive behaviours is mediated by psychopathy, narcissism, Machiavellianism, and sadism.

However, relationship was not significantly associated with the dark traits, as well as attitudes toward sexual coaxing, sexual coercion, and RMA. This indicates that relationship status and length may not be as influential in intimate sexual violence, leading to alternative underlying mechanisms that are responsible for the disproportionate amount of sexual violence in intimate relationships. Future research should begin to identify and explore which underlying mechanisms can moderate this relationship. Overall, the current study adds to previous research on the Dark Tetrad and acts as a starting point for future research into intimate sexual violence.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ames, D. R., Rose, P., & Anderson, C. P. (2006). The NPI-16 as a short measure of narcissism. Journal of Research in Personality, 40(4), 440-450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2005.03.002

- Balcioglu, Y. H., Doğan, M., Inci, I., Tabo, A., & Solmaz, M. (2023). Understanding the dark side of personality in sex offenders considering the level of sexual violence. Psychiatry Psychology and Law, 1–19.

- Barker, L. C., Stewart, D. E., & Vigod, S. N. (2019). Intimate partner sexual violence: An often overlooked problem. Journal of Women's Health, 28(3), 363-374. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2017.6811

- Benbouriche, M., & Parent, G. (2018). La coercition sexuelle et les violences sexuelles dans la population générale : définition, données disponibles et implications. Sexologies, 27 (2), 81-86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sexol.2018.02.002

- Blötner, C., & Mokros, A. (2023). The next distinction without a difference: Do psychopathy and sadism scales assess the same construct?. Personality and Individual Differences, 205, 112102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2023.112102

- Bonneville, V., & Trottier, D. (2021). Gender differences in sexual coercion perpetration: Investigating the role of alcohol-use and cognitive risk factors. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 1–21.

- Brewer, G., Bennett, C., Davidson, L., Ireen, A., Phipps, A., Stewart-Wilkes, D., & Wilson, B. (2018). Dark triad traits and romantic relationship attachment, accommodation, and control. Personality and Individual Differences, 120, 202-208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.09.008

- Brewer, G., Lyons, M., Perry, A., & O’Brien, F. (2019). Dark Triad Traits and Perceptions of Sexual Harassment. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 1–15.

- Brouillette-Alarie, S., Lee, S. C., Longpré, N., & Babchishin, K. M. (2022). An examination of the latent constructs in risk tools for individuals who sexually offend. Applying Multidimensional Item Response Theory to the Static-2002R. Assessment, 1–16.

- Brown, A. L., Testa, M., & Messman-Moore, T. L. (2009). Psychological consequences of sexual victimization resulting from force, incapacitation, or verbal coercion. Violence Against Women, 15(8), 898–919. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801209335491.

- Camilleri, J., Quinsey, V., & Tapscott, J. (2009). Assessing the propensity for sexual coaxing and coercion in relationships: Factor structure, reliability, and validity of the tactics to obtain Sex scale. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 38(6), 959-973. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-008-9377-2

- Carton, H., & Egan, V. (2017). The dark triad and intimate partner violence. Personality and Individual Differences, 105, 84-88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.09.040

- Chartrand, T.L., William W. M., & Lakin, J.L. (2006). Beyond the perception-behavior link: The ubiquitous utility and motivational moderators of nonconscious mimicry’, in Ran R. Hassin, James S. Uleman, and John A. Bargh (Eds), The New Unconscious, Social Cognition and Social Neuroscience.

- Christie, R., & Geis, F. (1970). Studies in machiavellianism. Academic Press.

- Depraetere, J., Vandeviver, C., Beken, T. V., & Keygnaert, I. (2020). Big boys don’t cry: A critical interpretive synthesis of male sexual victimization. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 21(5), 991–1010. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838018816979

- de Roos, M., & Jones, D. N. (2020a). Empowerment or threat: Perceptions of childhood sexual abuse in the #MeToo Era. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 1–26.

- de Roos, M., & Jones, D. N. (2020b). Self-affirmation and false allegations: The effects on responses to disclosures of sexual victimization. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 1–24.

- de Roos, M. S., Longpré, N., & van Dongen, J. D. M. (2024). When kinks come to life: An exploration of paraphilic concordance and underlying mediators. Journal of Sex Research. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2024.2319242

- Dirslane, L.E., & Patrick, C.J. (2017). Integrating alternative conceptions of psychopathic personality: A latent variable model of triarchic psychopathy constructs. Journal of Personality Disorders, 31(1), 110-132. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi_2016_30_240

- Evans, L., & Tully, R.J. (2016). The triarchic psychopathy measure (TriPM): alternative to the PCL-R? Aggression and Violent Behavior, 27, 79-86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2016.03.004

- Finkelstein, K. R. (2014). The influence of the dark triad and gender on sexual coercion strategies of a subclinical sample. Brandeis University.

- Gravelin, C. R., Biernat, M., & Baldwin, M. (2019). The impact of power and powerlessness on blaming the victim of sexual assault. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 22(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430217706741

- Heise, L., Moore, K., & Toubia, N. (1995). Sexual coercion and reproductive health: A focus on research. New York : Population Council. https://knowledgecommons.popcouncil.org/departments_sbsr-rh/522/.

- Hoffmann, A. M., & Verona, E. (2019). Psychopathic traits, gender, and motivations for sex: Putative paths to sexual coercion. Aggressive Behavior, 45(5), 527-536. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21841

- Home office. (2013). An overview of sexual offending in England and Wales. Statistic Bulletin.

- Jonason, P. K., Girgis, M., & Milne-Home, J. (2017). The exploitive mating strategy of the dark triad traits: Tests of rape-enabling attitudes. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46, 697–706. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-017-0937-1.

- Jonason, P. K., Luevano, V. X., & Adams, H. M. (2012). How the Dark Triad traits predict relationship choices. Personality and Individual Differences, 53(3), 180-184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2012.03.007

- Jones, D., & Figueredo, A. (2013). The core of darkness: Uncovering the heart of the dark triad. European Journal of Personality, 27(6), 521-531. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.1893

- Jones, D. N., & de Roos, M. (2016). Differential reproductive behavior patterns Among the dark triad. Evolutionary Psychological Science, 3(1), 10-19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40806-016-0070-8

- Jones, D. N., & Olderbak, S. G. (2014). The associations among dark personalities and sexual tactics across different scenarios. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 29(6), 1050-1070. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260513506053

- Jones, D. N., & Paulhus, D. L. (2009). Machiavellianism. In M. R. Leary, & R. H. Hoyle (Eds.), Handbook of individual differences in social behavior (pp. 93–108). NY.

- Jones, D. N., & Paulhus, D. L. (2014). Introducing the short dark triad (SD3): A brief measure of dark personality traits. Assessment, 21(1), 28–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191113514105

- Kiire, S. (2017). Psychopathy rather than Machiavellianism or narcissism facilitates intimate partner violence via fast life strategy. Personality and Individual Differences, 104, 401–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.08.043

- Knight, R. A., & Guay, J.-P. (2018). The role of psychopathy in sexual coercion against women: An update and expansion. In C. J. Patrick (Ed.), Handbook of psychopathy (2nd ed., pp. 662–681). The Guilford Press.

- Knight, R. A., Sims-Knight, J., & Guay, J. P. (2013). Is a separate diagnostic category defensible for paraphilic coercion? Journal of Criminal Justice, 41 (3), 90–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2012.11.002

- Knight, R. A., & Sims-Knight, J. E. (2003). The developmental antecedents of sexual coercion against women: testing alternative hypotheses with structural equation modeling. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 989, 72–153. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07294.x.

- Koscielska, R. W., Flowe, H. D., & Egan, V. (2020). The dark tetrad and mating effort's influence on sexual coaxing and coercion across relationship types. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 26(3), 394–404. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552600.2019.1676925

- Krstic, S., Longpré, N., Robertson, C., & Knight, R. A. (2018). Sadism, psychopathy, and sexual offending. In M. DeLesi (Ed.), Routledge international handbook of psychopathy and crime. Routledge.

- Longpré, N., Guay, J. P., & Knight, R. A. (2018). The developmental antecedents of sexual sadism. In J. Proulx, A. Carter, E. Beauregard, A. Mokros, R. Darjee, & J. James (Eds.), International handbook of sexual homicide. Routledge.

- Longpré, N., Knight, R. A., & Guay, J. (2019). Latent structure and covariates of the agonistic continuum among community sample and college students. Oral presentation at the 2019 Australian and New Zealand Association for the Treatment of Sexual Abuse (ANZATSA) Conference, Brisbane, Australia, July 24-26.

- Longpré, N., Moreton, R., Snow, E., Kiszel, F., & Fitzsimons, M. (2022). Dark traits, harassment and rape myths acceptances among university students. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 1–21.

- Longpré, N., Sims-Knight, J.E., Neumann, C., Guay, J.P., & Knight, R.A. (2020). Is Paraphilic Coercion a Different Construct from Sadism or Simply the Lower End of an Agonistic Continuum? Journal of Criminal Justice, 71, 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2020.101743

- McMahon, S., & Farmer, G. L. (2011). An updated measure for assessing subtle rape myths. Social Work Research, 35(2), 71-81. https://doi.org/10.1093/swr/35.2.71

- Office for National Statistics. (2022). Crime in England and Wales: Year ending September 2021. Statistics Bulletin.

- O'meara, A., Davies, J., & Hammond, S. (2011). The psychometric properties and utility of the Short Sadistic Impulse Scale (SSIS). Psychological Assessment, 23(2), 523–531. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022400

- Parent, G., Robitaille, M.P.., & Guay, J.P. (2018). La coercition sexuelle perpétrée par la femme : mise à l’épreuve d’un modèle étiologique. Sexologies, 27 (2), 113-121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sexol.2018.02.007

- Parent, G., Robitaille, M.P.., Guay, J.P. & Knight, R.A. (2014). Which female university students use sexual coercion to obtain sex contacts? Poster presentation presented at the 33th annual research and treatment conference of the association for the treatment of sexual abusers (ATSA), San Diego.

- Paulhus, D. L. (2014). Toward a taxonomy of dark personalities. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23(6), 421–426. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721414547737

- Paulhus, D. L., & Williams, K. M. (2002). The dark triad of personality: Narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy. Journal of Research in Personality, 36(6), 556–563. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-6566(02)00505-6

- Payne, D. L., Lonsway, K. A., & Fitzgerald, L. F. (1999). Rape myth acceptance: Exploration of its structure and its measurement using the Illinois rape myth acceptance scale. Journal of Research in Personality, 33(1), 27–68. https://doi.org/10.1006/jrpe.1998.2238

- Pineda, D., Martínez-Martínez, A., Galán, M., Rico-Bordera, P., & Piquera, J. A. (2023). The Dark Tetrad and online sexual victimization: Enjoying in the distance. Computers in Human Behavior, 142, 107659. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2023.107659

- Plouffe, R., Saklofske, D., & Smith, M. (2017). The Assessment of Sadistic Personality: Preliminary psychometric evidence for a new measure. Personality and Individual Differences, 104, 166-171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.07.043

- Prusik, M.., Konopka, K, & Kocur, D. (2021). Too many shades of gray: The Dark Triad and its linkage to coercive and coaxing tactics to obtain sex and the quality of romantic relationships. Personality and Individual Differences, 170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110413.

- Raskin, R. N., & Hall, C. S. (1979). A narcissistic personality inventory. Psychological Reports, 45(2), 590. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1979.45.2.590

- Reale, K.S, Beauregard, E., & Martineau, M. (2017). Sadism in sexual homicide offenders: Identifying distinct groups. Journal of Criminal Psychology, 7(2), 120-133. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCP-11-2016-0042

- Reling, T. T., Becker, S., Drakeford, L., & Valasik, M. (2021). Exploring the Influence of Hookup Culture on Female and Male Rape Myths. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(9), NP5496–NP5520. https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605188010

- Saravia, I., Longpré, N., & de Roos, M. (2023). Everyday sadism as a predictor of rape myth acceptance and perception of harassment. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 67(13-14), 1323-1342. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X231165430

- Seabrook, R. C., Ward, L. M., & Giaccardi, S. (2019). Less than human? Media use, objectification of women, and men’s acceptance of sexual aggression. Psychology of Violence, 9(5), 536–545. https://doi.org/10.1037/vio0000198

- Smith, C. V., Øverup, C. S., & Webster, G. D. (2019). Sexy deeds done dark? Examining the relationship between dark personality traits and sexual motivation. Personality and Individual Differences, 146, 105-110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.04.003

- Stefanska, E. B., Longpré, N., Bloomfield, S., Perkins, D., & Carter, A. J. (2020). Untangling sexual homicide: A proposal for a new classification of sexually motivated killings. Journal of Criminal Justice, 71, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2020.101729

- Struckman-Johnson, C., Struckman-Johnson, D., & Anderson, P. B. (2003). Tactics of sexual coercion: When men and women won't take no for an answer. Journal of Sex Research, 40(1), 76-86. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490309552168

- Szabó, P.S., Diller, S.J., Czibor, A., Restás, P., Jonas, E., & Frey, D. (2023). ““One of these things is not like the others”: The associations between dark triad personality traits, work attitudes, and work-related motivation. Personality and Individual Differences, 205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2023.112098

- Tachmetzidi Papoutsi, M. & Longpré, N. (2022). The nomological network of stalking with sexual harassment, sexual coercion, and dark personality traits. Oral presentation at the NOTA annual international conference. Leeds, England, 4-6 May.

- Tetreault, C., Bates, E. A., & Bolam, L. T. (2021). How dark personalities perpetrate partner and general aggression in Sweden and the United Kingdom. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(9-10), NP4743–NP4767. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260518793992

- Trottier, D., Benbouriche, M., & Bonneville, V. (2019). A meta-analysis on the association between rape myth acceptance and sexual coercion perpetration. Journal of Sex Research, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2019.1704677

- Trottier, D., Benbouriche, M., & Bonneville, V. (2021). A meta-analysis on the association between rape myth acceptance and sexual coercion perpetration. The Journal of Sex Research, 58(3), 375-382. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2019.1704677

- Tsoukas, A., & March, E. (2018). Predicting short- and long-term mating orientations: The role of sex and the dark tetrad. The Journal of Sex Research, 55(9), 1206-1218. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2017.1420750

- Wilkes, M., Milgrom, E., & Hoffman, J. R. (2002). Towards more empathic medical students: A medical student hospitalization experience. Medical Education, 36(6), 528-533. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01230.x

- Zeigler-Hill, V., Besser, A., Morag, J., & Campbell, W. K. (2016). The Dark Triad and sexual harassment proclivity. Personality and Individual Differences, 89, 47-54. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2015.09.048