ABSTRACT

Evidence suggests an increasing involvement of technology and online activities in child sexual abuse (CSA); however, empirical knowledge of the phenomenon is limited. This study investigated the role technology/online activities play in CSA, from the perspectives of healthcare professionals. Fifteen multidisciplinary healthcare professionals specialising in CSA assessment and therapy for children and adolescents completed a semi-structured interview. Results indicate technology and online activities can feature in the facilitation, perpetration, and aftermath of CSA in various ways, presenting unique challenges for victims, caregivers, and involved professionals. A range of complexities were noted in relation to CSA where there is a cyber component (e.g. permanence and reach of CSA images online), and implications for assessment and therapy at the child, parent/guardian, and clinician levels (e.g. tolerating uncertainty regarding images existing online). These findings are summarised in a diagrammatic framework, alongside priorities and prerequisites for addressing the problem of online/technology-assisted CSA.

PRACTICE IMPACT STATEMENT

Professionals involved in assessment and therapy would benefit from training about technologies and online activities popular among children and adolescents. It is advisable to include routine questions about technology use, associated risks, and technology-assisted/online experience during clinical assessments and intervention with children, adolescents, and their parents/guardians. The permanence, reach, and lack of control over CSA images online, the potential for re-victimisation and possible lack of resolution arising from difficulties identifying perpetrators, were noted as added complexities.

Introduction

The internet and associated technologies have profoundly impacted the problem of child sexual abuse (CSA), introducing various new means by which abuse can occur (Martin & Slane, Citation2015; von Weiler, Citation2015). CSA refers to the involvement of a child or adolescent in sexual activity for the gratification of the perpetrator or a third party (World Health Organisation [WHO], Citation2017). It encompasses a range of sexual offences minors are deemed unable to give informed consent to, do not fully comprehend, and/or are not developmentally prepared for (WHO, Citation2017). CSA has been transformed by the ascendancy of technology in several significant ways. The present study aims to further our understanding of this transformation from the perspective of professionals working in a specialist assessment and therapy capacity with children who have been sexually abused based on their direct experience.

Review of the relevant literature

Research conducted by Barnardos, involving practitioners supporting children who were sexually exploited, found that the percentage of CSA referrals with a technology or online component increased significantly between 2004 and 2014 (Palmer, Citation2015). Moreover, this trend has continued upward since (Hamilton-Giachritsis, Hanson, Whittle, Alves-Costa, Pintos, et al., Citation2020). With the proliferation of social networking sites and online gaming platforms, which are particularly popular among youth, the internet has made potential victims more accessible to individuals with a deviant interest in minors; it also facilitates communication between offenders regarding online platforms frequented by children and adolescents who they can then target (Bond & Dogaru, Citation2019). Existing evidence indicates the ways in which technology and online activities can feature in the perpetration of CSA are numerous and diverse. These include the production, dissemination, and possession of CSA images/recordings; non-consensual distribution of young people’s self-generated sexual images; online grooming of children for sexual activity online and/or offline; sexual extortion of children in cyberspace; and exposure of minors to inappropriate or abusive digital sexual content (Hanson, Citation2017; Quayle, Citation2016; von Weiler, Citation2015). The typologies of online/technology-assisted CSA are likely to broaden and modify as the digital world further advances and evolves (Hanson, Citation2017).

While the body of research into the trends of online/technology-assisted CSA is developing, it is confounded in several ways. In an overview of the literature, Quayle (Citation2016) asserts it is difficult to determine the prevalence of online CSA given an over-reliance on non-empirical reports as opposed to peer-reviewed research, and the use of general population probability sample surveys. Quayle (Citation2016) also asserts that prevalence varies depending on the definitions applied to online CSA behaviours, and our ability to identify and assess same. Regarding vulnerability to online CSA, Quayle (Citation2016) notes that extensive research has examined factors that make some children more vulnerable than others, however, it is difficult to ascertain from existing evidence the direction of relationships identified between online victimisation and psychological difficulties in affected youth. Considering the methodological limitations of the existing literature, alongside knowledge that technology and CSA are on a developing trajectory, the issue of online/technology-assisted CSA is significant enough to warrant on-going empirical and clinical attention.

Notwithstanding such limitations, the empirical literature regarding the involvement of technology in CSA has already provided important information about children and young people’s risk of online sexual solicitation (Wurtele & Kenny, Citation2016), their vulnerabilities to online grooming (Whittle, Hamilton-Giachritsis, Beech, and Collings, Citation2013), and CSA images online (Quayle & Newman, Citation2015; Quayle et al., Citation2018). There is also a developing literature concerned with understanding the impact that the digital element of CSA involving technology or online activities has on victims (Hamilton-Giachritsis, Hanson, Whittle, Alves-Costa, & Beech, Citation2020).

Research informs us about the he characteristics of youth at risk for the related online experiences of solicitation/grooming by adults. Wurtele and Kenny (Citation2016) highlight several noteworthy findings: risk of online sexual solicitation by adults is greater for adolescents aged 13–17 years than for children under 12; girls are about three times more likely than boys to receive online sexual solicitations; risk of receiving unwanted sexual contact online is higher for adolescents questioning their sexuality, experiencing psychological difficulties (e.g. depression), and experiencing other difficulties offline (e.g. parental conflict). Low parental involvement or monitoring, poor parent–child communication, engagement in risky online behaviours (e.g. accessing pornography websites), and greater internet use have also been linked to increased risk of online sexual solicitation (Wurtele & Kenny, Citation2016). Looking specifically at vulnerability factors for what they refer to as online grooming, Whittle, Hamilton-Giachritsis, Beech, and Collings (Citation2013) note the overlap with vulnerabilities associated with offline CSA; that is, youth who are female, adolescent, questioning their sexuality, and have a disability, low self-esteem, or mental health difficulties, appear to be more vulnerable to both online grooming and offline CSA, while lower parental monitoring of internet use and greater internet access appears to increase vulnerability to online grooming specifically. Some research also indicates that youth who would not typically be considered vulnerable to CSA offline, may be vulnerable online (Whittle et al., Citation2014).

Although research regarding the impact of CSA involving technology or online activities is still in its infancy, existing evidence suggests that many of the harmful effects associated with “offline” CSA are also applicable to CSA facilitated by or occurring via technology (Hanson, Citation2017). In a qualitative investigation of the impact of online grooming leading to online and/or offline CSA, Whittle, Hamilton-Giachritsis, and Beech (Citation2013) found that interviewed youth experienced psychological difficulties including shame, aggression, depression, and self-harm in the aftermath; however, impact appeared to be related to victims’ prior vulnerability levels and their experiences with professionals post-abuse. More recently, the impact of online/technology-assisted CSA for adolescents and young adults was investigated by Hamilton-Giachritsis, Hanson, Whittle, Alves-Costa, and Beech (Citation2020); their findings suggested that the negative effects of CSA were compounded by the permanence, reach, and loss of control of images online, re-victimisation (associated with people viewing one’s images online), negative responses from peers, family, and schools, and self-blame.

Studies involving professionals working in the field of CSA have yielded valuable insights into our understanding of aspects of this multifaceted problem that do not concern technology or online activities. However, though they have much to contribute, studies incorporating professionals’ perspectives of the implication of technology or online activities in CSA is limited, and much of this early research focuses on CSA images online (CSAIO).

von Weiler et al. (Citation2010) consulted professionals working with sexually abused children regarding the care and treatment of children abused through the online distribution of sexual images in Germany. Their findings indicated that many professionals viewed these cases as more complex than offline CSA due to the permanence of abusive images online, and associated feelings of helplessness; insecurity about diagnostic assessment, counselling, and therapy; insecurity concerning legal measures; fear of organised crime; and the need to keep up to date with new technological developments regarding child pornographic image production and distribution. Professionals also reported the existence of abusive images online heightens feelings of shame, guilt, and loss of control for victims, as well as leading to significant emotional distress for caregivers. However, over half of the professionals interviewed did not believe dealing with abusive images was a high priority for the victims during therapy or counselling, and many professionals reported feeling uncomfortable and insecure about how to address the issue of abusive images, citing fears of re-traumatising the child/adolescent.

Martin (Citation2014, Citation2016) corroborates the findings of von Weiler et al. (Citation2010) in similar research with professionals working with sexually abused children in Canada. Martin’s research highlighted diversity among the professionals interviewed in terms of how CSAIO were conceptualised and affects victims. Some professionals perceived the existence of images online to be as serious, if not more serious than conventional CSA, while others felt CSAIO were not necessarily as harmful or relevant as other issues pertaining to CSA experiences for some victims. Nonetheless, many participants noted that permanency, accessibility, and ongoing circulation of CSAIO may contribute to a sense of re-victimisation for affected children/adolescents, as well as impeding closure. Furthermore, findings indicated that many professionals felt ill-equipped to work with victims of CSAIO given a lack of theoretical and empirical research regarding potential effects, how to address the issue in therapy, and a perceived need for more specialised training (Martin, Citation2014; Citation2016).

More recently, Hamilton-Giachritsis, Hanson, Alves-Costa, Pintos, et al. (Citation2020) examined professionals’ perceptions of CSA facilitated or assisted by technology, its impact on youth compared to “offline” CSA, and service/organisational responses to it. They found that participants generally felt technology-assisted CSA was as impactful as offline abuse (though it is sometimes perceived by other professionals and organisations as less impactful, and of less immediate concern) and presents additional complexities for victims. These include offenders having more access and control; permanence, accessibility, and loss of control of digital images/content; the potential for re-victimisation; the potential for images to be used as blackmail; self-blame; blame by family; and difficulty recognising abuse. The authors also found that many participants were not clear about the additional support needs of youth affected by online/technology-assisted CSA, nor how they could meet such needs, highlighting the potential for missing or neglecting to ask about online/technological aspects of victims’ experiences.

The present study

With continued empirical investigation into the involvement of technology and online activities in CSA, our understanding of this complex problem is likely to improve, as is our capacity to assess, prevent, and effectively intervene. It is also likely to guide further empirical enquiry. The present study aimed to contribute to our knowledge regarding online/technology-assisted CSA by investigating the perspectives of specialist healthcare professionals (HCPs) directly involved in CSA assessment and/or therapy for children and adolescents, and their families, through semi-structured interviews. The specific objectives of the present study were to explore HCPs’ perceptions of

the involvement of technology/online activities in CSA generally;

the involvement of technology/online activities in their clinical experience;

the impact of the involvement of technology/online activities in CSA for children, families, and HCPs themselves; and

how to address the involvement of technology/online activities in CSA

Method

Study design

The present study employed a qualitative design, using semi-structured interviews to investigate HCPs’ perspectives on the role of technology and online activities in CSA.

Participants

Participants were 15 female HCPs (i.e. social workers, psychotherapists, psychologists, and one psychiatrist) working in the two specialist CSA assessment and therapy services for children and adolescents in Ireland. The sample represented approximately half of the population of HCPs working in such specialist services nationally.

Procedure

Ethical approval. Ethical approval was granted by Children's Health Ireland at Temple Street University Hospital Research Ethics Committee and Children's Health Ireland at Crumlin Children's Hospital Ethics (Medical Research) Committee. An information sheet outlining the nature, purpose, and implications of participation in the study was distributed to all potential participants, and written consent was requested from those who wished to participate. In the interest of confidentiality, participants were assigned pseudonyms and potentially identifiable details pertaining to clients they discussed in research interviews were omitted from the final report.

Data collection. Participants were invited to complete a semi-structured interview regarding their experience and perspectives on the role of technology and online activities in CSA. Due to the exploratory nature of the study, a flexible and adaptable research method was deemed necessary. Semi-structured interviews were selected as they can yield rich and detailed information likely to facilitate in-depth exploration of participants’ subjective realities and individual perspectives on the involvement of technology and online activities in CSA (Esterberg, Citation2002). The interview protocol was informed by discussion with two professionals who have worked extensively with children and adolescents who have experienced CSA. Interviews were conducted by the first author and ranged from 40 minutes to two hours, with most lasting approximately an hour. Audio recordings of interviews were transcribed verbatim and verified by the first author prior to analysis.

Analysis. A thematic analysis of participants’ interview responses using the guide provided by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006, Citation2022) was conducted to identify and describe patterns within the data. This involved the first author becoming familiar with the data by reading and re-reading transcripts, and then hand-coding them line by line. With initial codes generated for all 15 interview transcripts, segments of text relevant to each code were collated and categorised based on similarity of meaning. Categories were then grouped according to potential themes, which were reviewed in relation to individually coded extracts. The themes derived were defined and organised into four “domains”, each corresponding to a topic the author examined based on the objectives of the research. Finally, a narrative summary report of the findings was produced. Thus, data were analysed both inductively and deductively; themes were identified from an iterative review of participants’ insights and perspectives (i.e. data-driven), while thematic domains were analyst-driven in that they aligned with issues/concepts of interest to the author (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006, Citation2022). To improve the reliability and credibility of the findings, a second rater was recruited to review 20 per cent of the data (i.e. three interview transcripts), and the corresponding thematic analysis coding template generated by the first author. Overall, there was a high degree of agreement regarding the appropriateness of codes and themes generated. A reflective discussion between the author and second rater highlighted that the specificity of the titles of themes pertaining to one domain could be improved with minor adjustments, and appropriate changes were agreed.

Results

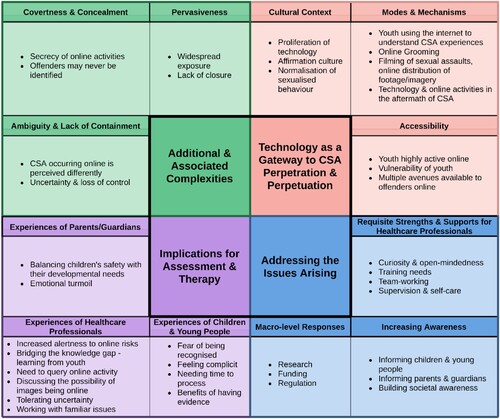

Themes generated through analysis of participants’ interview responses were grouped into four domains: 1. Technology as a gateway to CSA perpetration and perpetuation; 2. Additional and associated complexities; 3. Implications for assessment and therapy; and 4. Addressing the issues arising. Each domain respectively consists of three themes. Themes and their operational definitions are presented in . Below, themes are named and explained in relation to their respective domains, and pertinent subthemes are described alongside illustrative quotes. presents a diagrammatic summary of the four domains, themes and subthemes.

Figure 1. Visual representation of thematic patterns identified in the qualitative data regarding the involvement of technology and online activities in CSA.

Notes. The four identified domains are displayed in the centre, with themes pertaining to each outlined in the headings of the peripheral units. Subthemes are listed within each theme unit.

Table 1. Domains and definitions of identified themes.

Domain 1. Technology as a gateway to CSA perpetration and perpetuation

Themes within this domain related to the virtual world and associated factors that have created opportunities for children to be sexually abused or exploited and increased the ease with which individuals at risk of perpetrating CSA can offend.

Theme 1.1. Cultural Context. Three subthemes were noted in relation to this theme:

Proliferation of technology

This subtheme relates to the prevalence of technology and internet devices in modern society and how this can facilitate CSA:

Technology has exploded into our lives … for good, but also for danger … you know, technology can be used far more efficiently as part of the grooming process … that contributes to the, the real-world abuse, as well as the online abuse … I suppose risk factors that I would not have seen years ago, now I'm looking at them going … “If that hadn't been there would the abuse have happened?” … (Jane)

| (b) | Affirmation culture | ||||

This subtheme relates to how some young people’s pursuit of acceptance and membership of a peer group is facilitated by social media conventions of photo “likes”, thereby increasing their vulnerability to abuse/exploitation online:

They find it hard to make social connections and actually they can achieve that through online communities, or, you know, through the number of likes they get on their Instagram picture … and so they're vulnerable … they're looking for connections … for ways to improve their self-worth … (Denise)

| (c) | Normalisation of sexualised behaviour | ||||

This subtheme reflects the normalisation of sexualised behaviour, particularly for youth, online:

Sexualised behaviour is so incredibly normalised in our everyday lives, why wouldn't someone engage in sexual activities … or a conversation of a sexual nature online? Because they're just desensitised to it, they just think that … that's just the expectation and that they should just go with it. (Natalie)

Theme 1.2. Accessibility. This theme encompassed three subthemes:

Youth highly active online

This subtheme relates to the significance of having an online presence for young people, and how online activity can make them more accessible to CSA offenders:

They have an online presence so they’re accessible … to some young people that’s quite important to them … there have been times where [offenders] have come across people on Facebook and then, you know, been able to see what’s going on in their lives. (Catherine)

| (b) | Vulnerability of youth | ||||

This subtheme represents participants’ perspectives on circumstances and characteristics that make some children and adolescents vulnerable to online/technology-assisted CSA:

As a time of identity formation and, I suppose the vulnerability of children within new forms of media … you know, those newer spaces, and … just from a developmental level … the capacity for, you know, reflective … thinking … and, you know, executive functioning … differs, so you have, you know, vulnerable brains, if you like, in a vulnerable space. (Tríona)

| (c) | Multiple avenues available to offenders online | ||||

This subtheme relates to the wide range of social media, chat, and gaming fora accessed by youth, making them accessible to offenders in turn:

Social media has been a real positive for abusers and paedophiles, and other kinds of opportunistic abusers, because it provides an immediate access point that wasn't there before. (Mary)

Theme 1.3. Modes & Mechanisms. This theme encompassed four subthemes:

Youth using the internet to understand CSA experiences

Several participants noted that some children and young people who have experienced sexual abuse may try to process what has happened to them by “seeking out inappropriate material online” (Claire) and are thereby “inadvertently exposed to more” (Rosie).

| (b) | Online grooming | ||||

Offenders’ use of technology to access child victims and initiate the process of abuse through online grooming was cited frequently, and the insidious nature of the online grooming process was also highlighted:

Kids would have told me that, you know, you would get a message, saying, you know, being friendly, playful … and kind of trying to identify with them, “What colour do you like?”, “I like blue”, “Oh I love blue, blue is my favourite colour as well”, that kind of thing, to try and … hook them in. (Yvonne)

| (c) | Filming of sexual assaults, online distribution of footage/imagery | ||||

Participants noted that technology can feature in contact CSA with the filming of sexual assaults on youth and subsequent sharing of images online:

There’s quite a spectrum; sexting down to an offence being filmed and shared. (Aisling)

| (d) | Technology and online activities in the aftermath of CSA | ||||

This subtheme concerns the clinical relevance of technology or online activities in the aftermath of CSA:

Sometimes it's not even the photos, it's the social media after, you know … it gets out in the school, and everyone in school knows that … there's an alleged rape or … you know, people are talking about it on social media, and it's not necessarily that a photo as such is distributed, but it's all that kind of chatter, and belief and non-belief … that happens after that is … really shameful and really … really difficult for a young person to navigate their way through … (Aideen)

Domain 2. Additional & associated complexities

Themes and subthemes pertaining to this domain related to additional challenges posed by and associated with CSA where technology or online activities are involved.

Theme 2.1. Ambiguity & Lack of Containment. This theme encompassed two subthemes:

CSA occurring online is perceived differently

This subtheme relates to how CSA that occurred remotely via technology (e.g. online grooming) may not be considered real CSA, or as damaging or serious as contact CSA, by both affected youth and professionals:

Young people that I've met that have been involved with CSA or CSE over technology, or which involved technology, would definitely not see it as being as bad as, or as abusive as it would be if it was someone they know, or somebody face-to-face … (Siobhán)

| (b) | Uncertainty and loss of control | ||||

This subtheme relates to uncertainty about who has seen CSA imagery (including young people’s self-generated sexual images), and whether they could resurface in the future. It also reflects the inability to prevent such images from being distributed online:

Where the perpetrator is unknown or can’t be traced, like in another country or something, there is always that fear of what happens with these images and who has seen them and whether they’re gonna be made public. (Aisling)

Theme 2.2. Covertness & Concealment. Two subthemes were identified within this theme:

Secrecy of online activities

This subtheme reflects the clandestine nature of online activities (particularly those relating to sexuality), and associated risks (e.g. potential for minors to view inappropriate sexual content, vulnerability to CSA):

I think it's much easier to disguise your true identity online … You can, you can become anyone you want to, you could pose as a, you know, a fellow 13-year-old girl, but you're a 50-year-old man, and, you know … it’s very … difficult to really know, you know, who you're truly talking to. (Denise)

| (b) | Offenders may never be identified | ||||

This subtheme concerns difficulties identifying CSA offenders where abuse/exploitation occurred online (e.g. bringing charges when offenders’ identities are unknown):

Because there's no identified person … that impacts on their day-to-day functioning in that everybody becomes a potential. It could be him; it could be that man in the supermarket. It could be that woman, or whoever … (Denise)

Theme 2.3. Pervasiveness. This theme included two subthemes:

Widespread exposure

This subtheme relates to the potentially limitless dissemination of CSA images (including self-generated sexual images) on the internet:

It’s so hard to navigate the system, and to work to try and get those taken down offline … there’s no assurance that it isn’t on another site, or you don’t know who has taken it down onto a desktop or a laptop, or a computer (Lia)

| (b) | Lack of closure | ||||

This subtheme relates to the difficulty online CSA victims may have with moving forward when their images or information remain online:

When kids are coming in for treatment for abuse, the work is much easier once the abuse is over, and with some of these with technology or online stuff, it can feel like it’s ongoing, or there might be images out there that might pop up in some form, like I know a teenager that still gets messaged and threats from a guy who contacted her on an online forum. (Yvonne)

Domain 3. Implications for assessment & therapy

Themes collected under this domain related to the implications of online CSA on assessment and therapy for victims, parents/guardians, and HCPs.

Theme 3.1. Experiences of children & young people. The online component of CSA cases appeared to have several implications for children and young people:

Fear of being recognised

This sub-theme relates to anxiety experienced by children and young people whose images have been distributed online (i.e. CSA images, including self-generated sexual images) regarding the possibility of being recognised:

People have a fear of being recognised offline, you know, in reality … you know, a teenager sends a consensual … nude or semi-nude picture to a boyfriend or a girlfriend, and then it gets shared around the school. (Jane)

| (b) | Feeling complicit | ||||

This subtheme relates to the potential for young people to feel that they colluded in activities which led to their abuse/exploitation:

Some of them might feel … in some way, it’s their fault, because they sent the image, or they made the video … So, that they had, you know, a role in it. (Denise)

| (c) | Needing time to process | ||||

Several participants indicated that typically victims of online/technology-assisted CSA need time to process and make sense of their experiences, particularly if their images have been distributed online:

Maybe younger children … they're not aware of that … it's more when they maybe reach adolescence, 16, 17 … even 18 and older. They’re becoming more mature emotionally, and then they realise … these images of me when I was 12 or 14 are … in the ether somewhere … As young children they're not able to conceptualise … the bigger picture in all this, and it's actually … as they grow and mature … it's a whole other layer of the impact. (Yvonne)

| (d) | Benefits of having evidence | ||||

This subtheme reflects participants’ reports that if evidence that CSA has occurred (i.e. images or chat history) exists, the affected child/young person, may progress directly to therapy, without needing to undergo CSA assessment:

If there’s online messages and stuff like that, often those messages can be found … by the police, they can often get a record of what was sent … which can really validate a child’s experience … so there’s a positive element actually … (Yvonne)

Theme 3.2. Experiences of parents/guardians. Two subthemes regarding implications for parents/guardians were identified:

Balancing children’s safety with their developmental needs

This subtheme concerns support parents/guardians may require with implementing measures to keep their children safe, without impeding their development. Several participants reported that many caregivers remove children’s access to digital devices following the discovery of online CSA. However, participants asserted that youth should have access to technology, albeit with safety controls in place.

Often it can lead to … a parent kind of being more overprotective of a child and cutting off all access to technology … so kind of trying to help support the parents or carers to, to have those appropriate boundaries in place, while making sure that they're not overstepping those boundaries and putting in too much … too many restrictions. (Jane)

| (b) | Emotional turmoil | ||||

This subtheme pertains to distress parents/guardians experience in relation to online components of CSA perpetrated against their child:

Parents feeling guilty, that, you know, because it suited them to allow their child play, and it kept them quiet and they were busy, and it actually got them out of their head, so, those kind of very normal parenting reactions. (Ciara)

Theme 3.3. Experiences of healthcare professionals. This theme encompassed several subthemes:

Increased alertness to online risks

Several participants reported that awareness of CSA involving technology has made them more aware of the risks associated with having an online presence:

All of the experiences we have in our professional setting, you know, we bring them to our own lives, and so we are excessively vigilant around our own children, around, you know, you have a different lens, trying to work that out, you have an awareness of … I suppose the dangers … but it’s a bit … skewed, so … managing that … in your own life, as well … (Catherine)

| (b) | Bridging the knowledge gap – learning from youth | ||||

This subtheme relates to HCPs’ need to bridge gaps in their knowledge when technology and online activities are clinically relevant. It also reflects reports that having curiosity and being open to learning from youth can help bridge these gaps:

The world is totally different than what it was 20 years ago when we were teenagers … and I don’t understand that world, it's so different. So, I think we need to take some time to understand it … because that's where this stuff is happening … So, we need kids to help us understand, and we need to listen to them. (Rosie)

| (c) | Need to query online activity | ||||

Several participants reported that evidence of online/technology-assisted CSA has highlighted the need to investigate the online activities of children and young people attending for CSA assessment or therapy:

Kids and teenagers are so au fait with these things, that they don’t even … might not even see something that we might see as concerning, they might not necessarily see it, or they might not even … volunteer that how they met somebody initially was online, or that was a feature, if they sort of start the story further in from, because the questions we might be asking, might be just geared, sort of the first time something happened, so that then in their mind that might be around contact … but actually the whole back picture is really important to us. (Ciara)

| (d) | Discussing the possibility of images being online | ||||

This subtheme relates to the possibility that CSA images of children attending for assessment or therapy may be in circulation online, and how discussion about this issue with families should be managed carefully:

It’s something that might need slow exploration, I think … I mean, we would be saying if images are out there … people need to be honest with them … it is really important, so, it's just about doing that sensitively and then supporting them. (Claire)

| (e) | Tolerating uncertainty | ||||

This subtheme relates to challenges HCPs face in terms of dealing with the uncertainty pertaining to CSA cases where there is a cyber element:

It's hard as a clinician not to be able to fully reassure a young person, you know, so, sitting with that uncertainty and that unknown being- you know, is, is hard … I suppose we do it all the time, but I think there's something so pervasive about online activity, you know, so, I suppose … that's difficult, and sitting with that, and sitting with that with families is difficult. (Rebekah)

| (f) | Working with familiar issues | ||||

This subtheme represents HCPs’ reports regarding issues that typically present in CSA cases involving technology or online activities. In comparing online/technology-assisted CSA cases with cases where technology is not featured, several participants expressed that similar emotions are experienced by victims and their families:

Of course, every child is individual and has their own processes regardless of what, you know … around the abuse, but I think there are always themes that emerge across both spectrums, online and offline, such as trust, safety, risk, guilt, shame … (Rebekah)

Domain 4. Addressing the issues arising

Themes and subthemes in this domain relate to participants’ perspectives on how to address the challenges posed by the involvement of technology and online activities in CSA.

Theme 4.1. Requisite strengths & supports for HCPs. This theme comprised four subthemes:

Curiosity & open-mindedness

Several participants identified the importance of being curious and open-minded in relation to potential or confirmed involvement of technology or online activities in CSA:

You don’t have to know everything as a therapist, or a professional, you have to be able to ask about it, and that’s to be curious. (Catherine)

| (b) | Training needs | ||||

This subtheme relates to how the availability of up-to-date training on online platforms and trends, and other relevant issues, would assist HCPs in their work:

I think training is a big part, becoming aware of how quickly it can change. (Aisling)

| (c) | Team-working | ||||

This subtheme relates to the importance of having a supportive team to manage the challenging aspects of CSA cases involving technology and online activities:

Being able to talk to your colleagues, process it, feeling comfortable to talk about whatever … to one of your colleagues and I think that’s vital. (Mary)

| (d) | Supervision & self-care | ||||

This subtheme relates to the importance of accessing supervision and engaging in self-care when working with CSA generally, and for managing difficult emotions related to the online/technology-assisted CSA specifically:

Through your own self-care, through processing it with your colleagues in work I think it’s important that like, it’s contained. (Lia)

Theme 4.2. Increasing awareness. This theme encompassed three subthemes:

Informing children and young people

This subtheme relates to the need to make children and young people aware of the risks of engaging with strangers and posting sexual images online:

Young people are very aware, but they still don't seem to understand, you know, the impact of putting an image of themselves out there. (Siobhán)

| (b) | Informing parents/guardians | ||||

This subtheme relates to the importance of informing parents/guardians about the risks of children/adolescents having unsupervised access to the internet, and helping them understand how their children may have become involved with offenders online:

With families … maybe explaining blame as well, because that can be something that can be quite an issue for some families, coming in angry where their young person might have sent an image or engaged online and trying to explain the kind of subtle dynamics that happens online in games, and grooming that happens online. (Aisling)

| (c) | Building societal awareness | ||||

This subtheme relates to the need for greater awareness in society about the potential for CSA to be facilitated by technology, and how to prevent and respond to the issue of online/technology-assisted CSA:

I think we probably need to talk with … parents, wider systems, schools, [Irish police force] … it’s not just about being aware of it … how they respond will actually have a significant impact. (Catherine)

Theme 4.3. Macro-level responses. Several participants raised the need for increased regulation, funding, and research to prevent and address online/technology-assisted CSA:

It's an internet policing issue probably, like from, from a higher- or agency like the government or somebody who can control that. (Rosie)

Discussion

Evidence indicates that technology and CSA are on a developing trajectory; however, empirical literature examining this phenomenon is still limited. Through exploration of the perspectives of HCPs specialising in CSA assessment and therapy, the present study sought to further knowledge about how technology and online activities may be involved in CSA; the impact of that involvement for children, families, and clinicians; and what is needed to address this problem. Findings provide valuable insight into online/technology-assisted CSA and highlight several areas that warrant research and clinical attention.

Summary of main findings

Participants highlighted various ways technology can feature in the facilitation and perpetration of CSA (e.g. online grooming, filming of sexual assaults) and exacerbate negative effects in the aftermath (e.g. circulation of images online). Participants also highlighted several contextual phenomena which appear to contribute to the occurrence of online and technology-assisted CSA, including the ubiquity of digital devices and activities and their popularity among youth, as well as developmental issues (e.g. seeking validation from peers) which may increase vulnerability to certain forms of CSA for some youth. Numerous complexities associated with the involvement of technology in CSA were also noted, corroborating the findings of Hamilton-Giachritsis, Hanson, Whittle, Alves-Costa, Pintos, et al. (Citation2020) and Martin (Citation2016) in several ways. Firstly, participants highlighted that in some instances, CSA that occurs online is considered less serious than contact/face-to-face CSA. Secondly, the permanence, reach, and lack of control of CSA images online, potential re-victimisation (e.g. through image distribution and resurfacing), and lack of resolution given difficulties identifying perpetrators, were noted as added complexities of online CSA.

Several participants discussed challenges presented by the hidden nature of online activities in relation to the problem of CSA, with some noting the ease with which offenders can conceal their identity and make connections with victims by purporting to be younger, for example. These findings also echo those of Hamilton-Giachritsis Hanson, Whittle, Alves-Costa, Pintos, et al. (Citation2020) regarding the difficulty for victims to recognise that they are being abused or exploited given offenders’ ability to disguise their motives and themselves.

Related to some of the complexities identified, participants described several ways the involvement of technology or online activities can impact CSA assessment and therapy. Some reported that youth who have experienced CSA with a cyber component may present with anxiety about being recognised from images online, and/or guilt related to feeling responsible or complicit in their abuse. Relatedly, some participants described how youth may endeavour to conceal the online/technology component of their CSA experiences due to shame, stigma, and potential ramifications (e.g. parental anger). These findings echo prior research which suggests that youth may be reluctant to disclose or discuss online harassment, for example, for fear that parents will prohibit internet access (von Weiler, Citation2015). Several participants also reported that in some instances, victims may struggle to comprehend and process their abuse experiences, depending on their age, stage, or other circumstances, and therefore may need to revisit therapy as they mature. This echoes findings of von Weiler et al. (Citation2010) which relates to professionals’ reports that some children abused through the online distribution of sexual images were not fully cognisant of the technology (e.g. images) aspect of their abuse, thus, other issues, such as the emotional impact of their CSA experiences were dealt with first.

Regarding parents/guardians, the present findings echo prior research (e.g. von Weiler et al., Citation2010) by highlighting the distressing impact of realising images of one’s child exist online. Participants described how parents/guardians may feel guilt, shock, and shame when their child has experienced online/technology-assisted CSA. Furthermore, in some instances, following the realisation that technology or online activities were implicated in the sexual abuse of one’s child, caregivers may seek to eliminate further risk by limiting the child’s access to technology. Participants reported that in these instances, therapeutic work may incorporate the provision of guidance for parents/guardians in relation to supporting children to safely use the internet, rather than preventing them from going online entirely.

Regarding implications for HCPs, several participants reported that the upward trend of CSA involving technology has made them more cognisant of the need to query children and young people’s online activity so that safeguards can be implemented as necessary. Several participants acknowledged the possibility for CSA images to be online, and the need to discuss this with victims/families in some instances; however, there was a consensus that care is needed to avoid exacerbating their trauma. Some participants noted that issues associated with online CSA (e.g. pervasiveness, lack of containment) can limit their ability to provide reassurances to victims and families. Participants also described challenges arising from their ignorance about technology and online activities the clients discuss in assessments or therapy; some reported experiencing self-doubt regarding their capacity to fully understand clients’ experiences and offer effective support, and some highlighted the possibility that youth may refrain from speaking about the technology component of their CSA experience if they perceive it to be irrelevant or the HCP to be uninformed. However, many participants acknowledged that whether CSA occurs online or fully face-to-face, similar issues arise (e.g. shame, guilt), and HCPs can offer support regardless of their technological savviness. Furthermore, some participants reported that the implication of technology/online activities in CSA had made them more alert to risks associated with having an online presence, and that this may cause them to consider the potential vulnerability of clients online, as well as impacting on their own personal lives and relationships.

Participants offered several ideas for managing challenges posed by the implication of technology and online activities in CSA and addressing the problem of online/technology-assisted CSA itself. Many highlighted the value of supportive team-working given the distressing and demanding nature of working with children and families affected by CSA. Access to supervision and engaging in self-care were also considered important. Regarding what HCPs need to enable and support them to work effectively with CSA where there is a cyber component, several participants reported that regular up-to-date training or information on digital trends and activities would enable them to better understand clients’ experiences. Some also suggested that opportunities to consult a forum of young people about online platforms that are popular among youth would be helpful. The importance of having an open-minded and curious approach to working therapeutically with victims and their families was also noted by many. Raising awareness about the risks associated with certain online activities among children and adolescents, parents/guardians, and wider society was also discussed in relation to tackling and preventing the facilitation of CSA by technology. Furthermore, several participants emphasised the need for regulation of the virtual world, increased funding to improve prevention and intervention efforts, and more research aimed at understanding the complex problem of technology-assisted CSA.

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of the present study is that it provides a novel and comprehensive insight into the implication of technology and online activities in CSA by drawing on the perspectives of HCPs specialising in CSA assessment and therapy. Moreover, through its diagrammatic representation of the themes identified in the data, the present study offers a useful framework for understanding and communicating about the ways in which technology may feature in the facilitation and aftermath of CSA, associated complexities, implications for assessment and therapy, and prerequisites and priorities for assessing, addressing, and preventing this complex problem. However, certain limitations must be acknowledged.

Firstly, practitioners in the present study were drawn from just two specialist CSA assessment and intervention services and the overall sample size was small. While participants were well-placed to comment on the implication of technology and online activities in CSA, the recruitment process may have further resulted in a somewhat selective sample; that is, the perspectives of participants may be more representative of children whose CSA experiences have involved an offline/face-to-face component (i.e. not purely online CSA). As several participants noted, CSA which occurs online is frequently perceived differently to contact CSA, and many children and young people affected can feel as if they were complicit in or responsible for sexually abusive or exploitative actions perpetrated against them online. In addition to the covert and hidden nature of CSA occurring online, these phenomena may decrease the likelihood that affected children will present to services such as those involved in this study. In the interest of developing a more complete understanding of the role of technology in CSA, research that considers and integrates the perspectives of professionals with other backgrounds (e.g. clinicians working with persons at risk of offending), as well as affected youth is warranted.

Implications for theory and practice

The present study has several implications for theory, policy, and practice. Firstly, prior research has highlighted the need to establish clear definitions of online/technology-assisted CSA to better understand the parameters and severity of the phenomenon, and successfully intervene (i.e. Hamilton-Giachritsis, Hanson, Alves-Costa, Pintos, et al., Citation2020; Quayle, Citation2016). Given the broad focus of the present study, its findings may inform efforts to define CSA with a cyber component and differentiate its specific effects and support needs from those of offline CSA. Furthermore, the diagrammatic representation of themes identified offers a starting point from which future theoretical and empirical research can be formulated.

At the service level, findings suggest that HCPs involved in CSA assessment and therapy would benefit from training on technologies and online activities popular among children and adolescents. Such input is likely to aid their understanding of clients’ CSA experiences and promote their confidence in working with CSA cases where there is a cyber component. It may also be beneficial for referral documentation and service literature to specify technology-assisted/online CSA typologies to acknowledge that sexual abuse occurring online constitutes CSA, and to signal referral routes for victims whether CSA occurred online and offline.

In terms of clinical practice, the findings suggest that HCPs should be cognisant of the potential implication of technology or online activities in the facilitation, perpetration, and aftermath of the CSA experiences of children and young people they work with. Furthermore, where CSA is a concern, HCPs should enquire about their clients’ engagement with digital devices as standard so that potential evidence of abuse/exploitation is identified, and risks can be addressed. More specifically, the inclusion of a routine question set about technology use, associated risks, and technology-assisted /online CSA experience in the clinical intake assessment conducted with children, adolescents, and their parents/guardians, to ensure the systematic evaluation of the potential involvement of technology or online activities in cases where CSA is queried or suspected. Assessment of clients’ online activity during the processes of CSA validation and therapy, and provision of psychoeducation regarding the mechanisms and contextual determinants of online/technology-assisted CSA, may also benefit child and adolescent victims. That is, youth may be better able to understand how technology and online activities may have been used to facilitate abuse or exploitation perpetrated against them, thereby helping them to realise that they are not to blame. HCPs should also convey curiosity and openness to discussing possible involvement of technology or online activities in their clients’ abuse experiences so that victims who are reluctant to disclose (e.g. due to feeling complicit or responsible for abuse they endured), or do not consider the online/technology component(s) of their experiences to be relevant, may be more likely to raise these matters in therapy. Thus, pertinent issues (e.g. guilt, shame) can be addressed, and appropriate safeguards can be implemented.

Considering participants’ reports of their increased alertness to online risks alongside research highlighting the potential for CSA practitioners to overidentify with their clients’ trauma responses and experience vicarious trauma (Martin, Citation2016), it is recommended that service managers provide supports for HCPs working in CSA assessment and therapy and that HCPs engage with same to ensure they are adequately prepared to deal with complexities arising within cases where technology and online activities are featured (e.g. lack of control and uncertainty regarding the spread of CSA images).

Suggestions for future research

The findings of the present study point to several areas for further research. Firstly, knowledge regarding the involvement and impact of technology and online activities in CSA is likely to be improved by extending research such as the present study to include youth affected by online and technology-assisted CSA, and their parents/guardians. With empirical investigation of victims’ unique perspectives on the pathways to and impact of technology-assisted/online CSA, and those of their caregivers, the focus and effectiveness of preventative educational initiatives for victims and their support networks is likely to be improved (Hamilton-Giachritsis, Hanson, Whittle, Alves-Costa & Beech, Citation2020). Furthermore, given that parents/guardians have an important role in supporting victims’ adjustment following adverse and traumatic CSA experiences, more focused exploration of their perspectives is likely to assist involved professionals in identifying and addressing barriers to effective treatment and progress. The findings of such research could be compared with current knowledge regarding the mechanisms and impact of offline CSA to further understanding of technology-assisted/online CSA, and to inform assessment and intervention processes. Future research should also seek to evaluate the implementation of recommendations made, namely, provision of training for HCPs who work in CSA assessment and therapy regarding popular online platforms; standardising assessment of online activities in CSA validation and therapy; and incorporating psychoeducation for victims regarding the mechanisms by which online/technology-assisted CSA may occur (e.g. strategies used to groom youth online).

Findings of the present study also highlight several gaps within the theoretical and empirical literature regarding the involvement of technology or online activities in CSA that should be addressed. While further foundational research may be necessary in the first instance, future research should endeavour to explore how to work sensitively and effectively with victims of online/technology-assisted CSA, for example, in relation to the permanence and pervasiveness of images online. Likewise, further exploration of how support needs of parents/guardians of victims can be met would also be beneficial (e.g. how to monitor children’s online activity and identify risks, while also facilitating their engagement with the virtual environment in an age-appropriate way).

Conclusion

The ascendency of information technologies has had a considerable impact on CSA, introducing several additional complexities to an already complex and serious problem. A small but developing literature indicates that CSA with a cyber component is becoming more prevalent; however, efforts to prevent and intervene around this are constrained by a limited understanding of the pertinent risk factors and vulnerabilities, and the mechanisms by which online or technology-assisted CSA can occur. The present study sought to further current understanding of the role that technology and online activities play in the sexual abuse of children and adolescents by considering the perspectives of professionals working in CSA assessment and therapy. Findings demonstrate that technology and online activities may be implicated in the facilitation, perpetration, and aftermath of CSA in numerous ways, presenting unique challenges for affected youth, caregivers, and HCPs. While there is still much to be learned about CSA with a cyber component, the present study provides a comprehensive overview of several important domains for consideration in terms of understanding and addressing the phenomenon of online/technology-assisted CSA. Findings are synthesised in a diagrammatic framework that may be useful for guiding future research and educating parents and professionals about risks, vulnerabilities, and mechanisms of CSA online. Given the harmful effects of CSA and the constant evolution of the technological landscape, it is imperative that the involvement of technology in CSA is afforded more empirical, clinical attention so that the complex problem can be managed and addressed.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Ms. Julia von Weiler and Ms. Sharon Oughton for their assistance with the development of the interview protocol; to Dr. Niamh Doyle for her assistance with data analysis; and to Mr. Seán Murray for his assistance with graphical illustrations.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Bond, E., & Dogaru, C. (2019). An evaluation of an inter-disciplinary training programme for professionals to support children and their families who have been sexually abused online. British Journal of Social Work, 49(3), 577–594. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcy075

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2022). Thematic analysis. A practical guide. Sage.

- Esterberg, K. (2002). Qualitative methods in social research. McGraw-Hill.

- Hamilton-Giachritsis, C., Hanson, E., Whittle, H., Alves-Costa, F., & Beech, A. (2020). Technology assisted child sexual abuse in the UK: Young people’s views on the impact of online sexual abuse. Children and Youth Services Review, 119(April), 105451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105451

- Hamilton-Giachritsis, C., Hanson, E., Whittle, H., Alves-Costa, F., Pintos, A., Metcalf, T., & Beech, A. (2020, August). Technology assisted child sexual abuse: Professionals’ perceptions of risk and impact on children and young people. Child Abuse and Neglect, 119(1), 104651. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104651

- Hanson, E. (2017). The impact of online sexual abuse on children and young people. In J. Brown (Ed.), Online risk to children: Impact, protection and prevention (pp. 97–122). Wiley.

- Martin, J. (2014). “It’s just an image, right?”: Practitioners’ understanding of child sexual abuse images online and effects on victims. Child and Youth Services, 35(2), 96–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/0145935X.2014.924334

- Martin, J. (2016). Child sexual abuse images online: Implications for social work training and practice. British Journal of Social Work, 46(2), 372–388. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcu116

- Martin, J., & Slane, A. (2015). Child sexual abuse images online: Confronting the problem. Child and Youth Services, 36(4), 261–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/0145935X.2015.1092828

- Palmer, T. (2015). Digital dangers: The impact of technology on the sexual abuse and exploitation of children and young people. https://www.barnardos.org.uk/sites/default/files/uploads/digital-dangers.pdf.

- Quayle, E. (2016). Researching online child sexual exploitation and abuse: Are there links between online and offline vulnerabilities? Global Kids Online. www.globalkidsonline.net/sexual-exploitation.

- Quayle, E., Jonsson, L. S., Cooper, K., Traynor, J., & Svedin, C. G. (2018). Children in identified sexual images – Who are they? Self- and non-self-taken images in the International Child Sexual Exploitation Image Database 2006–2015. Child Abuse Review, 27(3), 223–238. https://doi.org/10.1002/car.2507

- Quayle, E., & Newman, E. (2015). The role of sexual images in online and offline sexual behaviour with minors. Current Psychiatry Reports, 17(6), 43–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-015-0579-8

- von Weiler, J. (2015). Living in the era of digital exhibitionism. Child and Youth Services, 36(4), 329–344. https://doi.org/10.1080/0145935X.2015.1096596

- von Weiler, J., Haardt-Becker, A., & Schulte, S. (2010). Care and treatment of child victims of child pornographic exploitation (CPE) in Germany. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 16(2), 211–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552601003759990

- Whittle, H. C., Hamilton-Giachritsis, C., & Beech, A. R. (2013). Victims’ voices: The impact of online grooming and sexual abuse. Universal Journal of Psychology, 1(2), 59–71. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujp.2013.010206

- Whittle, H. C., Hamilton-Giachritsis, C. E., & Beech, A. R. (2014). In their own words: Young peoples’ vulnerabilities to being groomed and sexually abused online. Psychology (savannah, Ga ), 5(10), 1185–1196. https://doi.org/10.4236/psych.2014.510131

- Whittle, H., Hamilton-Giachritsis, C., Beech, A., & Collings, G. (2013). A review of young people’s vulnerabilities to online grooming. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 18(1), 135–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2012.11.008

- World Health Organisation. (2017). Responding to children and adolescents who have been sexually abused: WHO clinical guidelines.

- Wurtele, S. K., & Kenny, M. C. (2016). Technology-related sexual solicitation of adolescents: A review of prevention efforts. Child Abuse Review, 25(5), 332–344. https://doi.org/10.1002/car.2445