ABSTRACT

The essay charts the shifting place of Laocoon as an exemplum of translation across the arts of word and image from Pliny to Clement Greenberg. It uncovers a rich history of artistic translation, reproduction, and imitation of Laocoon in Renaissance drawing, painting, prints, decorative arts, and sculpture of every size and material, from plaster casts to table-top porcelains. The paper subsequently follows the changing fate of Laocoon within artistic pedagogies as a study in word-image relations, from a Renaissance teaching model, to the trope of critical theory on the definition of ‘art’. Thus, the term ‘translation’ is used advisedly, to signal acts of artistic transmission predicated on transfer not only between cultures, but across materials and media. The essay concludes by considering the continuing place of Laocoon within art criticism, albeit in radical antagonism to the ideals of art it was once held to embody, to address the contested formation of an art ‘classic’ through the cultural as well as material processes of artistic translation.

I. Translatio

On 14 January 1506 a Roman landowner surveyed his newly-acquired vineyard on the Oppian Hill in a landscape laden with archaeological history. From the ruins of the Domus Aurea to the baths of Titus and Trajan, it was undergirded by richly decorated subterranean halls in various states of collapse such as that in which our landowner soon found himself. Here he would uncover one of ancient Rome’s most celebrated sculptures, from among the greatest excavations of its classical past. News of the remarkable discovery spread swiftly, the antiquarian pope Julius II immediately sending word to his architect, Giuliano da Sangallo, to investigate the find. A letter by Sangallo’s son, Francesco, written sixty years later, vividly recalled the events of that day:

The first time I was in Rome, when I was very young, the Pope had just been told about the discovery of some very beautiful statues in a vineyard near S Maria Maggiore. The pope ordered one of his officers to tell Giuliano da Sangallo to go and see them at once …. Since Michelangelo Buonarotti was always to be found at our house then … my father had him come too … Descending to where the sculptures lay, my father said: “That is the Laocoon, of which Pliny makes mention.” Then they widened the opening to pull the sculpture out. On seeing it, we turned to drawing it, all the while discoursing on ancient things … Footnote1

Laocoon’s rich history of translations originated in the very moment of its recovery, as Francesco da Sangallo’s letter relates. ‘As soon as it was visible’ those gathered to witness the discovery began ‘to discourse, and to draw’, immediately transposing its sculptural form into words and graphic marks on paper ( and ). In so doing they launched its long serial history of imitation-as-translation in both text and image.

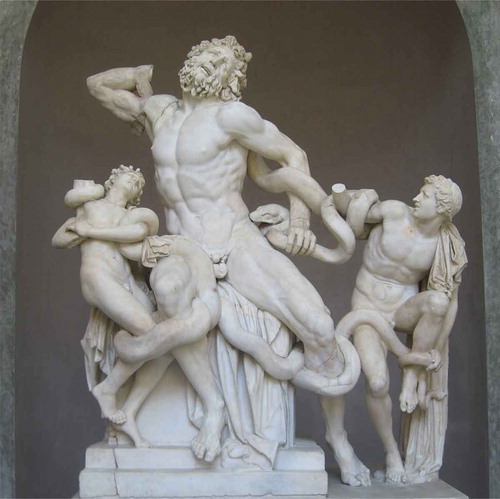

Figure 1. Marco Dente da Ravenna, Laocoon at the Servian Wall, c. 1520–23. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 2. Hagesandrus, Polidorus, Athenodorus of Rhodes, Laocoon, 40–30 B.C., Vatican Museums, Vatican City. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

The application of ‘translation’ as an inter-linguistic model for the visual arts, characterised for the Renaissance by the rendition of ‘classical’ into ‘vernaculars’, rests on a deeply rooted approximation between text and image, words and things, inherited from antiquity. To claim a concordance for a non-verbal medium is thus to invoke classical precepts of arts and letters as sister branches of rhetoric. But it is also, as the case of Laocoon’s subsequent critical reception history so brilliantly illustrates, to trouble semiotic theorisations of word-image relations and their influential yet conflicted position within the history of art. Thus, the term ‘translation’ is deployed advisedly here, for the application of linguistic models to the study of art history is complex and contested. While the identification of formal and iconographic sources has long been a mainstay of the arts and literatures alike, it is the fuller discussion of their inter-medial histories and temporal slippages that this essay probes, by extending the model of linguistic translation to study the material basis of such visual transfers. For the term ‘translation’, in its broader applications, may usefully signal artistic acts of imitation predicated on a transfer not only between temporalities and cultures, but also between media: in the case of Laocoon, from a monumental marble sculpture into the two-dimensional arts of painting, drawing, print; the replications of casting in plaster and bronze; or the diminutive scale of the decorative arts in porcelains and precious metals. The Latin term ‘translatio’ springs from the ‘translation’ or reburial of saints’ relics as practised throughout the Middle Ages. Thus, it is rooted in an object-based materiality, through the recovery of once-lost and greatly revered bodies, just as Laocoon’s history may be understood to represent in the broader cultural domain. Further, the essay takes up the current ‘translation turn’ in the social sciences and humanities as a dynamic model of cultural transmission that allows for ruptures and reversals within a contested history of artistic imitation, and so the complex formation and subsequent fall of an art ‘classic’, as the case of Laocoon so redolently exemplifies.Footnote2

Under Julius II, Laocoon’s recovery would inaugurate the formation of the Vatican Museum’s Belvedere display of antique sculptures to facilitate study of this great translatio, so launching a canon of classicism in the visual arts that would lead cultural development for over 400 years.Footnote3 The concurrent Renaissance foundation of art academies similarly understood the future of art to lie in a deep mimetic engagement with its past, teaching the formation of artistic memory through the practice of drawing as imitation. Within this trope of art history as emulation, each excavation of Rome’s antiquity, as with Laocoon, brought about an anthological extension of art’s figural vocabularies and syntactical arrangement of forms. Thus, every new art object was judged on its use of the history of art, to produce a visual culture of mimesis distinguished by inventive adaptation. Imitation of antique art as the fount and canon of excellence was as fundamental to the early modern understanding of artistic training as the studied translation of classical texts for Humanities learning. Within this pedagogic paradigm, Laocoon would become the privileged site of instructive imitation as a visual canon of ideal form from which students drew, repeatedly, in order to commit to memory its figurative composition. The traces of graphic media on paper, as the record of this memorative process of drawing, produced a wealth of transcriptions in imitation of the Laocoon in all media, materials and sizes. Thus, Laocoon would become the key exemplum of all the Renaissance arts of visual translation.

Laocoon’s Renaissance reception was haunted by the recollection of ancient texts as much as antique objects, exemplified in Giuliano da Sangallo’s recognition of the sculpture from his knowledge of Pliny. Pliny had described the Laocoon as the foremost example not only of sculpture but of all the arts:

… the Laocoon in the Palace of the Emperor Titus, a work superior to any in painting or in bronze. Laocoon, his children, and the marvellous clasping coils of the snakes were carved … by those eminent craftsmen, Hagesander, Polydorus, and Athenodorus, all from Rhodes.Footnote4

Pliny’s passage situated the work within a comparison between painting and sculpture, or paragone as it came to be known. Such paragone between sculpture and painting would structure art criticism and theory throughout the sixteenth century in terms of medial translations between these arts, which shaped the conceptual processes of its most renowned artists, among them Leonardo, Raphael, and Michelangelo.Footnote5 The paragone debate on the distinctions and merits of painting and sculpture was further framed by the legacy of antiquity on literature as a sister art to painting in its pictorial use of language, encapsulated in Plutarch’s ‘painting is mute poetry; poetry a speaking picture’ and the Horatian dictum ‘ut pictura poesis’.Footnote6 As heir to this long correlation between word and image, Laocoon became the emblem of Renaissance art’s ‘translatio studii’, or the great transfer of culture from antiquity into early modernity through its rediscovered objects and texts. Laocoon’s composition circulated widely through the new Renaissance medium of printing, in addition to painting and drawing, as well as all the other forms of sculptural reproduction and replication including plaster cast, bronze, marble copies, and decorative arts. Laocoon’s emergence from the earth was understood as a metaphor of the ‘rebirth’ of classical learning by which Renaissance intellectual culture defined itself. This was the critical matrix into which it was received on entering the Renaissance imaginary to become, in WJT Mitchell’s words, a ‘hyper-icon’ of art.Footnote7

II. The Light in TroyFootnote8

At a height of 208 cm (6ʹ8”), the figure of Laocoon is of monumental though not colossal proportions, carved of Greek Parian white marble. He stands on the steps of the altar where, as a priest of Troy, he worshipped the gods and made sacrifice. On either side he is flanked by his young sons. The composition is bound together by the disposition of their out-flung limbs and the winding coils of the serpents that wrap around them even as they struggle to resist. The subject arises from the epic cycles of Greek myth on the Trojan War. Though accounts differ, the story relates how, alone among his countrymen, Laocoon warned the Trojans against accepting the Greek gift of a colossal wooden horse. This attempt to defy divine destiny infuriated the gods, who sent great sea serpents to destroy him. The fullest account of the story is Virgil’s, whose Aeneid retells the myths of the Trojan war as a Homeric odyssey leading to the foundation of Rome, as Aeneas flees Troy to become the mythic founder of Latium. While the dating of the Laocoon sculpture remains open to scholarly debate, it is likely close in time to the Aeneid, and although carved by Greek sculptors there is general consensus that it was executed in and for early Imperial Rome.Footnote9 Thus from inception its materials and sculptural methods were those of cultural transmission between Greece and Rome. Its size, marginally larger than life yet within a seemingly lifelike scale, may also be understood as an artistic translation of life into art through a heightening of ideal form. Similarly, Renaissance scholars such as Ludovico Dolce understood Virgil’s text and the Laocoon sculpture to have nurtured each other’s invention in a full affirmation of the correlation of the sister arts.Footnote10

At the finding of Laocoon Michelangelo had just completed the monumental David in Florence, and was recently invited to Rome by Julius II to undertake the Pope’s tomb and subsequently the Sistine ceiling, so establishing his position as the leading artist of his time. His encounter with Laocoon is acknowledged as profound. In its monumental and muscular yet tortured frame Michelangelo manifestly recognised an artistic and bodily language of heroic suffering, or terribilità, that he would make his own. Laocoon echoed forcibly throughout his Julian commissions, translated and transposed. In the marble Slave figures for the papal tomb, and the ignudi of the Sistine vault, scholars have long noted Michelangelo’s deep engagement with the Laocoon in both sculpture and painting. Heroic in proportions and anatomy, the torsion of Laocoon’s straining musculature compassed the endeavour of Michelangelo’s art, and so of his followers. Through Michelangelo, Laocoon’s tragic figuration was translated as the fullest visual sign of noble suffering. Laocoon’s face, eyes rolled back in their sockets and open mouth, like his noble and tortured body, was equally assimilated into the visible manifestation of heroic death, especially of crucifixion and martyrdom scenes. Michelangelo’s visual engagement greatly strengthened and intensified Laocoon’s long echo in art history as the fount of art, now multiplied through a second ‘origin’ in the Michelangelesque ().Footnote11

Laocoon’s subsequent history as an object of artistic emulation was one marked by the highest degree of inter-medial translation into pictorial, as well as sculptural types of art. Critics have often suggested that, although fully three-dimensional, the planar disposition of Laocoon’s composition is fundamentally relief-like, inviting the rivalry with painting that Pliny inaugurated. From its earliest Renaissance reception, the Belvedere sculpture was indeed viewed and understood through the prism of drawing, and subsequently painting and print, all of which entailed the practice-based transposition of statuary into two-dimensional form. These circulated, for example, in lavish editions of prints after Rome’s antiquities for noble libraries, as well as cheaper versions for use in artists’ workshops, so multiplying Laocoon’s further translations in a flat, linear medium in a greatly reduced scale. Above all, Laocoon circulated in plaster casts of all sizes for early modern art academies as models for instruction world-wide, from St Petersburg to Sao Paulo.Footnote12 Laocoon would also appear in the diminutive arts of porcelain and maiolica, in silverware and decorative borders, as miniature reductions in precious metals of bronze, silver, gilt and gold, for table-top ornaments grouped as ‘portable museums’ in princely souvenir collections, and as gemstones for aristocratic adornment (). Here its translation into jewel-like materials and proportions signified not so much the affects of noble death but the heroic form and the authority of antiquity as the source of culture. Its multiplying figuration served as further models to its serial emulation in every context and medium. Thus, Laocoon resonated across the arts in an expansive succession of visual citations and medial translations as the canon of artistic form.Footnote13

III Lexicon

With Laocoon’s arrival at the Vatican in March of 1506, papal architect Donato Bramante took stock of its impact on his developing designs for the Belvedere courtyard, and on artistic training arising through its imitation. The constant presence of students in the courtyard drawing after Laocoon suggested to Bramante a means of heightening the processes of artistic translation already at work. Inaugurating a prize-giving competition among them, he suggested that each student make a wax model of Laocoon of which the best example would be cast in bronze. Bramante asked Raphael, recently called to Rome by Julius II to paint the Vatican palace stanze, to serve as a judge of the student models. The competition favoured the wax by a young sculptor and architect from Venice, Jacopo Sansovino, which was then cast in bronze in 1510 at the invitation of the Venetian cardinal, classical scholar and collector, Domenico Grimani. Now lost, a further version in the Bargello attributed to Sansovino is the best remaining record of this earliest academy translation.Footnote14

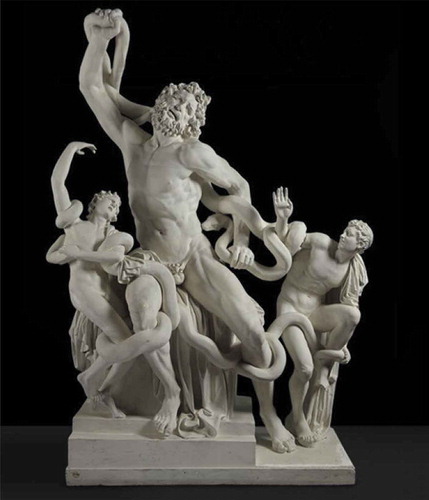

Key to the competition was the reconstruction of Laocoon’s missing limbs, for the sculpture had been found with incomplete arms and hands. Some of the earliest reproductions of Laocoon represented the sculpture as it was extracted from the ground, missing the right arm of the main figure and that of his younger son, the right hand of his older son, and possible further serpent coils around them (). As with the Renaissance retrieval of other antiquities, however, and of which Laocoon would be a leading example, the process of translating the piece from excavation to display prompted completion of missing parts in the interests of the narrative of the work, as understood through the prism of art’s paragone with poetry. Bramante’s competition launched the long history of Laocoon imitation as a field of invention, for the art of the prize rested on the resolution of Laocoon’s missing arms which the students were invited to complete. Thereafter, artistic copies of Laocoon increasingly translated its damaged form into sculptural completion, producing artistic dialogue between its many versions and a lexicon of variations to compare with the canon of antiquity in a further paragone of ancients and moderns. Thus, the missing right arms became the ‘puzzle’ of the Laocoon, and the loci of its inventive translation in all media of art.Footnote15

Figure 5. Francesco Primaticcio, Laocoon, 1543, Fontainebleau, Musée National du Château. Photo: © RMN-Grand Palais (Chtâeau de Fontainebleau/Gérard Blot).

This history of inventive transposition would also characterise a succession of marble restorations of the limbs of the sculpture itself, which may be understood as further sequences of visual adaptation. With an impetus to completion of the missing parts, these came to favour an increasingly strong upwards diagonal for the right arm and the introduction of a further serpent variously coiled around the hand that seeks to restrain it, while varying the direction and degree of the curve or fold in the added limbs. Eighteenth-century sources all give slightly different accounts of Laocoon’s earlier restorations, based on the available verbal and material evidence of the time. Jonathan Richardson Snr, Charles de Brosses, J.J. de Lalande, and J.J. Winckelmann variously recalled from their travels to Rome that Bernini was thought to have reworked the limbs in the mid-seventeenth century, and that Michelangelo himself was involved with a possible positioning of Laocoon’s right arm in the early 1540s, though apparently he declined or did not finish the work out of reverence for the antique.Footnote16 Its definitive restoration came shortly thereafter, seemingly based on work by the Belvedere sculpture restorer and Michelangelo’s pupil, Giovanni Angelo Montorsoli.Footnote17 Montorsoli’s would become the enduring translation of this antique source into its lasting idiom for 400 years. The strong upward thrust of the reconstructed right arm of the main figure suggested the Virgilian Laocoon’s attempt to pierce the Trojan horse with his spear in order to demonstrate the Greek duplicity, and so the righteousness of his tragic courage; to enrich the narrative temporality of the sculpture within Renaissance cultures of pictura poesis, and to strengthen the sightlines of its visual display at the head of the Belvedere courtyard.Footnote18 It was this version of Laocoon that would be copied and multiplied in every medium and size over four centuries, as the source and sign of art ().

Figure 6. Laocoon plaster cast with raised arm, prior to the 1959 restoration, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

Change to this canonical adaptation in favour of the greater archaeological accuracy of the sculpture today came only in the mid-twentieth century, predicated on the chance recovery of what has generally won acceptance as the intended pose of Laocoon’s hand and forearm in a Roman stonemason’s shop in 1905. The fragment was first identified by Ludwig Pollak, Director of Rome’s Museo Barracco di Scultura Antica. This led to reworking the right arm into its present deep bend at the elbow in 1959, apparently close to the configuration that Michelangelo had originally proposed, and as the arm of his Dying Slave suggests ( and ).Footnote19 Questions of translation run like a continuous thread of this sculpture’s history of restoration as of imitation, most recently in the new media of digital indices. A 2017 exhibition on Laocoon casts at the Humboldt University of Berlin, in particular, underscored the juxtaposition of the screen, plaster cast, and 3-D printed variations of Laocoon’s arms in a continuing narrative of medial translations of this antique form ().Footnote20

IV Towards a Newer LaocoonFootnote21

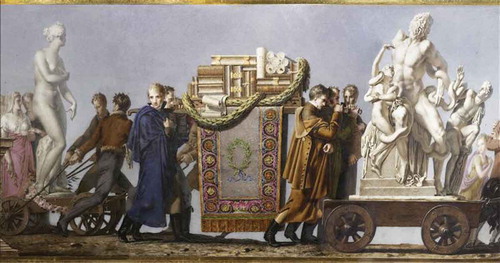

On 19 February 1797 the newly-formed French Republic, led by its rising General Napoleon Bonaparte, brought the Papal States to surrender. Terms arising included the right of French commissioners to enter any public or institutional building to extract its works of art for transport to Paris. These were intended to augment the collections of the Louvre, now reformed from a royal holding into the nation’s first public museum. The Vatican works were explicitly listed, chief among them Laocoon. When the sculptures arrived in July of 1798, they were paraded by oxen through the Champ de Mars as a re-enactment of a Roman imperial triumph for France (). In a breath-taking reversal of cultural dominance, Napoleon left casts at the Belvedere where its celebrated antiquities had once stood. The French also removed the ‘Italian’ restoration of the missing limbs in order to replace them with a new iteration intended as the ‘French Laocoon’. Just three weeks after the coup d’état that brought Napoleon to power at the end of 1799, the new ‘emperor’ visited the Louvre to oversee himself the installation of his artistic booty, assigning Laocoon a room of its own and in its name as a sign of its artistic apotheosis.Footnote22

Figure 8. Antoine Béranger, Sѐvres vase, detail, 1813, Musée National de la Céramique, Paris. Photo: © RMN-Grand Palais (Sèvres, Cité de la céramique)/Martine Beck-Coppola.

Yet within the weave of Napoleon’s great cultural victory over Rome that Laocoon’s translatio to Paris so powerfully symbolised, the seeds of its dissolution were already present. At Napoleon’s fall in 1815 Laocoon would return to Rome through the diplomatic manoeuvres of Antonio Canova, then director of Papal art and antiquities as well as sculptor to both Napoleon and the Papacy, who regarded Laocoon as ‘the first of all sculptures’.Footnote23 But its cultural position, like that of the Medici Venus, was already in decline.Footnote24 It is true that prints and plaster casts of Laocoon would continue to be made in ever-growing numbers, by print publishers and casting workshops in both Paris and Rome. With a wide diaspora across Europe and beyond, it served the needs of greatly expanding numbers of museums and art academies across the nineteenth century as the enshrined exemplum of artistic instruction, its form translated by students into drawing, painting, engraving, and sculpture as never before. Nonetheless, the very period of Laocoon’s imperial triumph in Paris also witnessed the discovery of newer-older ‘Laocoons’ that would come to challenge the supremacy of the Belvedere sculptures. This arose forcibly with the arrival of the Elgin marbles from the Parthenon in Britain in the early 1800s, which would begin to displace the position of Rome’s antiquities in favour of Greece as the ‘true’ source of art. The question of what was a translation, and what should be translated, grew more complex.

In his capacity as British ambassador to the Ottoman Empire 1799–1803, Thomas Bruce Lord Elgin’s antiquarian interests led him to record the extant remains of the Parthenon sculptures, which he found in ruins, by employing artists to make documentary drawings and casts after them. The subsequent controversy surrounding the removal of the marbles by Elgin is too well known to bear repeating here; what is noteworthy is the lengthy negotiations for their purchase by the British Museum which were not concluded until 1816. The rhetoric of national political debate for the justification of the acquisition of the Elgin marbles broadly remained that of comparison with the ‘old’ (but newer) canon of the Belvedere sculptures as the touchstones of culture, the value of the Parthenon measured in relation to the Vatican collection. Yet within it was a growing awareness of historical paradox in the perception of Roman art. As antiquarian scholars began to acknowledge that Roman sculpture was largely composed of what came to be seen as ‘copies’ of Greek exemplars – though we would dispute the teleological framework today – Greece began to replace Rome as art’s ‘source’.Footnote25

Elgin’s interest in Greek art and in particular the Parthenon marbles of course sprang from deeper shifts in eighteenth-century antiquarian research spurred by cultures of neoclassicism. This crystallised in the works of the scholar and papal prefect of antiquities, J.J. Winckelmann, notably his 1764 publication on the history of ancient art. For the first time, he endeavoured a chronological and comprehensive account of Greek and Roman art. In seeking to identify distinctions between historical periods and particularly of Greek from Greco-Roman, his philological methods began to raise the troubling question of Roman ‘copies’ of Greek art. Quickly appearing in reeditions and translations, the book was widely influential in shifting attention to ancient Greece as art’s true ‘source’, from which Roman art would increasingly come to be seen as a later derivation. Winckelmann himself praised Laocoon as among the greatest exemplars of art, yet his text would unleash questions about Greco-Roman sculpture to suggest an historical contingency, a manifestation within a much larger history of imitation and translation rather than a fount or origin. Questions of Laocoon’s relative historical position, still debated by scholars today, slowly began to recast its place within the history of classical art. Wrestling with Laocoon’s stellar reputation within his framework of historical excellence, Winckelmann acknowledged doubts yet continued to identify the sculpture as a Greek ‘masterpiece’, placing it in the Alexandrian age so as to maintain its pre-eminent position as a paradigm of art within his classification by period.Footnote26 But the very methods of his forensic and philological analysis would soon begin to call this attribution into question.

Among the earliest and most enduring responses to Winckelmann’s text was that of the German cultural critic, G E Lessing, published in 1766 under the title of Laokoön, oder Über die Grenzen der Malerei und Poesie. Earlier drafts show that Lessing began with the problematic of his subtitle – ‘On the Limits of Painting and Poetry’ – and only subsequently, with the publication of Winckelmann’s book, did he gather the text around the example of Laocoon. Lessing’s book was the turning point at which Laocoon shifted position from the sign of art to the trope of criticism.Footnote27 In keeping with his broader aim of defining boundaries between text and image, Lessing focussed on the sculptural depiction of Laocoon’s cry. This was in direct response to a passage in Winckelmann’s visual analysis of the piece, which he had praised for its depiction of Stoic restraint of the passions in the face of tragic suffering. Winckelmann’s studied consideration of the depiction of the shape of the mouth rightly observed that this represented not a scream but only a deep sigh, citing Cardinal Jacopo Sadoleto’s 1506 poetic response to the sculpture, with its attention to the pictorial rendering of the sculpture’s ‘voice’, to bolster his argument: ‘This Laocoon does not cry out horribly as in Virgil’s poem: the way in which his mouth is set does not allow of this; all that may emerge, rather, is an anguished and oppressed sigh, as Sadoleto says’.Footnote28 In so saying, Winckelmann returned to the ancient question of paragone in pictura poesis. Privileging sculpture over poetry, Winckelmann made Virgil’s account of the myth secondary not only chronologically but also in terms of nobility of conception.

Lessing’s response was robust. While agreeing with Winckelmann on the ethics of a Stoic restraint, he placed the sculpture’s date firmly after Virgil in an assertion of the primacy of text over image, and argued for the full nobility of Virgil’s scream within the context of the poet’s narrative. He charged the sculptural Laocoon as a secondary derivation exemplifying ancient art’s decline, what he termed art-historical ‘lateness’. But his greater concern was that of clear distinction on the boundaries between painting and poetry, all the while acknowledging the power of poetic imagery. Using the Vatican sculpture as his point of reference precisely because of its celebrated history of word-image relations, Lessing’s purpose was none other than the disentangling of the ‘sister arts’. Instead of the long history of ‘pictura poesis’ and its illusion of ‘speaking statues’, he insisted on the clear rupture between the arts of word and image. The mouth of Laocoon does not scream, he argued, because art cannot speak. In effect, Lessing argued for the ‘untranslatability’ of the respective arts.

In so doing, Lessing reframed Laocoon as a new kind of exemplar, the dialectical sign of art theory and aesthetics, following Alexander Baumgarten’s influential theorisation of the term in his Aesthetica of 1750. J.W. von Goethe would subsequently take up Lessing’s challenge, using Laocoon as his emblem for theorising again the relations between the arts, albeit to new ends. If Lessing insisted on the incommensurability of translation between what he understood as the visual ‘arts of space’ and the literary ‘arts of time’, Goethe complicated the issue by taking up the visual representation of implied motion, and so the intimation of temporality, in the plastic arts. Goethe thus troubled ‘classicising’ concepts of heroic restraint, attending instead to the magnificent pathos of Laocoon’s suffering as one that unfolds across time through a sequential reading of the sculpture’s figures. His ‘Uber Laokoon’ of 1798 further introduced the concept of translating visual perception into critical text as an inter-medial form itself, in ‘reading’ art’s narratives between image and text, so cementing Laocoon’s new-found role as the sign of art theory.Footnote29

Critical debate notwithstanding, plaster casts after Laocoon and other Belvedere antiquities, alongside the Parthenon, would continue to multiply across the nineteenth century, for burgeoning numbers of newly-formed colleges of art and design. In the UK, government implementation of art and design in higher education across the 1830s led to the institutionalisation of colleges across the country, all requiring cast collections as central to their teaching; as also in the USA through the National Academy of Fine Art and Design founded in 1801, whose principal mission was to acquire casts for art colleges and universities. Casts were understood as a key means of democratising access to cultural knowledge. The pattern was similar in Germany, centred on Berlin’s Academy of Art, and the leading archaeological cast collection at the University of Göttingen. In Spain, the court collections of casts first assembled by Velazquez were made available to art students as instruments of pedagogy at the Real Academia de Bellas Artes from its foundation in 1758. Throughout the eighteenth century in France, interest centred on the legacy of Fontainebleau’s great casts after Rome, and the developing cast collection of the French Academy in Rome for the use of artists chosen for the Prix de Rome. From the mid-nineteenth century there was growing interest in establishing a museum of copy casts in Paris, which was understood as a democratising medium of popular dissemination like photography, and led to the establishment of a dedicated cast museum in 1879 following the World Exhibition at Trocadero. Similarly, in London there was governmental discussion concerning the establishment of a national cast museum in Crystal Palace after the Great Exhibition of 1851 (never achieved), while the Victoria & Albert Museum promoted an international convention on art reproductions to facilitate the mutual exchange of copies in 1867. These nineteenth-century cast collections typically included the most celebrated antiquities of the Roman Renaissance – the Belvedere sculptures, the Medici Venus, the Dying Gaul – but also of Greek sculpture – the Parthenon marbles, the Venus de Milo, and the Winged Victory of Samothrace among others. At the universities of Göttingen and Edinburgh, London’s Soane Museum, and New York City College, for example, if Laocoon was still a catholic example, yet the Parthenon marble casts were now the most highly prized of all.Footnote30 Translating the form of the Laocoon through drawing remained a widely-used art-school exercise, yet the question of what, exactly, was being translated became increasingly difficult to determine.

V Antiquity NowFootnote31

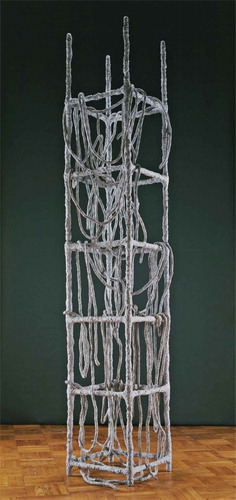

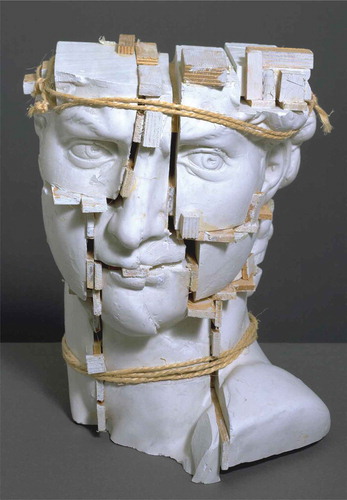

Eduardo Paolozzi’s conception of his plaster cast collage, Michelangelo’s David, apparently originated in a chance encounter with the cast as an object caught in translation between the domains of ‘high’ art and the ‘pop’ of an industrialised consumer-culture classicism (). Walking past Harrods one morning Paolozzi witnessed a window dresser placing a plaster cast of the David head into a vitrine display. He borrowed the head so as to re-cast it as an exact replica of this art of mass production, which was then sawn into fragments, inserting small blocks of plywood into the cuts, and binding it with brown twine. His ‘attack’ on the cast was, he said, in memory of the student riots that had destroyed the cast collection at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich, where he taught, and of his own training at Edinburgh College of Art in the early 1940s in which casts were fundamental to the pedagogy.Footnote32 His ready-made remade the copy cast into the sign of art protest.

Figure 9. Eduardo Paolozzi, Michelangelo’s David, c. 1987, Tate Galleries, London. Photo: © Trustees of the Eduardo Paolozzi Foundation, licenced by DACS 2018, Tate Images..

Paolozzi was of the moment. The nadir of art college cast collections dates just after his education to the 1950s, when many were moved into crowded often inadequate storage and left to neglect or simply destroyed.Footnote33 Training by drawing after casts from the antique canon was part of academy curricula no longer (). Yet Paolozzi’s later homage to their destruction is just as forcibly a recollection of their enduring presence within his oeuvre, and to their long pedagogical history as the source of art’s authority. Laocoon too endured in his work, though translated and reframed: in his 1963 collage, The Metallization of a Dream; in the title of an aluminium sculpture of that same year; and radically transposed in the coiling metal tubes of his Poem for the Trio MRT (1964) as an homage to sculpture’s history. Howsoever displaced as a material or mimetic source, Laocoon’s name remained as the sign for critical debate on the condition of art. When literary critic and scholar Irving Babbitt wrote his 1910 polemic on the ‘confusion of the arts’ he titled it ‘The New Laokoön’ to turn again to the problem of disentangling text/image relations.Footnote34 In this regard it is surely salient that, since the time of its Napoleonic presence in Paris, Laocoon became an emblem of political satire across Europe and America, text and image interwoven as bande dessinée to parody injustice, from ministerial wrangling to the strangling bureaucracy of the state ().Footnote35 When the leading art critic of the mid-twentieth century, Clement Greenberg, put the case for abstract expressionist painting in 1940, he wrote under the title of ‘Towards a Newer Laocoon’. His text dismantled the word-image translation nexus in which the Plinian-Renaissance Laocoon was so fully wrapped, taking up again Lessing’s call of medial ‘purity’ to end the ‘confusion’ of literature and art. Indeed, his call for painting was to abandon completely its claim to narrative illusion in the name of abstraction.Footnote36 If the sculpture itself is nowhere to be found in Greenberg’s text, yet the Laocoon title’s lexical reference endured. Stripped of its place as the source of art, Laocoon’s long history as an academy exemplum reverberates throughout the twentieth-century cultural critique as the name for debate on the condition of art. It referenced new works of art, from Salvator Dali to Claes Oldenburg, Eva Hesse, Wim Botha, Ossip Zadkine, Sanford Biggers, Leon Underwood, Roy Lichtenstein, or Richard Deacon, albeit in degrees of counterpoint, abstraction, even open rebellion, to its once hegemonic claim as the canon of art (). As visual citations, Laocoon’s form survived in opposition to itself, now purposefully mistranslated into new historical contexts and media, in sculpture and installation art, pop art, and mass-produced cartoons of political parody.Footnote37 In the collective memory of visual philology, Laocoon’s cry echoes still, though now as the emblem of an over-turned past. Sign of an obsolete method of art, an abandoned source, a classical thesaurus, a grammar of ancient practice: this is Laocoon’s ‘antiquity now’.

Acknowledgments

The research for this article draws on an AHRC award in ‘Translating Cultures’, ‘Sculpture in Painting: Medial Translations in Renaissance Art’. Sincere thanks to the editors of the volume for the kind invitation to participate in this publication, to the generous feedback from readers, and to audiences who heard earlier versions of this paper. Unless otherwise indicated all translations are my own, though indebted to previous scholarly versions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Genevieve Warwick

Genevieve Warwick is Professor of the History of Art at the University of Edinburgh. From 2012-17 she was Editor and Chair of Art History the national journal of the Association for Art History UK. At home she has served as Director of Research, and Director of the Graduate School in Arts and Humanities. She is a member of the AHRC Peer Review College, and has served as assessor to the Getty Grant Program, the Carnegie Trust for the Universities of Scotland, and the Scottish Graduate School for Social Sciences. She also acted as consultant on Open Access publishing for the Visual Arts for the University of Edinburgh; the Association for Art History UK; and Getty Publications, in collaboration with the British Academy and the Scottish Funding Council. Her research has been funded by the Getty Grant Program, the Arts and Humanities Research Council UK, and the Leverhulme Trust. She is author of 9 books on Renaissance and Early Modern Art History including studies of Bernini, Caravaggio, and Poussin; on artists’ drawings and art collecting; on prints and reproductive arts; art and science, and art and technology. She is currently Major Research Fellow of the Leverhulme Trust to complete a book titled: ‘The Mirrors of Art: Painting and Reflection in Early Modern Europe.’ She teaches across undergraduate, postgraduate, and PhD, with specialist courses in student curating with university collections. She lectures widely in universities across Britain, Europe and the U.S., and the National Galleries in London, Edinburgh and Dublin; the Ashmolean Museum, the Royal Academy, and the Accademia di San Luca Rome.

Notes

1. Francesco da Sangallo to Vincenzo Maria Borghini, 28 February 1567, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana Chig. I V 178, in Settis (Citation1999), 99–115. See Muth (Citation2017) and further bibliography below. Leonard Barkan questioned the translation of ‘desinare’ in Tuscan dialect in recent lectures.

2. De Saussure (Citation2011); Peirce (Citation1960-66); Jakobson (Citation1959); Bakhtin (Citation1968); Deleuze (Citation1968); Barthes (Citation1957) and (Barthes Citation1977); Eco (Citation1976); Brown (Citation2004). Within art history: Aby Warburg, Alois Reigl, Michael Fried, Rosalind Krauss, WJT Mitchell; and with particular relevance to Settis (Citation2004) and (Settis Citation2015).

As an antecedent to this essay, Black and Warwick (Citation2014); Warwick (Citation2017).

3. Buranelli, Liverani, and Nesselrath (Citation2006).

4. Pliny (1469), XXXVII, 39; Isager (Citation2013). Scholars have debated whether the Vatican piece is the same as Pliny’s, as Cesare Trivulzio and subsequently Pirro Ligorio first queried, in Settis and Maffei (Citation1999), 108–9, 208–9. For recent discussion, Muth (Citation2017).

5. Barocchi (Citation1998).

6. The classic statement is Lee (Citation1940).

7. Mitchell (Citation1986), 158.

8. Greene (Citation1982). The fundamental art-historical discussion is Panofsky (Citation1960).

9. Winner, Andreae, and Pietrangeli (Citation1998).

10. Dolce (Citation1557), 27.

11. Gilio (Citation1564), 87–88; Lomazzo (Citation1584) XVI, 165–6. Viljoen (Citation2007); Summers (Citation1984).

12. Pevsner (Citation1940); Boschloo (Citation1989); Frederiksen and Marchand (Citation2010) particularly the sections on academies, workshops and museums, 164–368, 464–650; Argan (Citation1967), 179–81; Landau and Parshall (Citation1994); Pon (Citation2004); Black and Warwick (Citation2014).

13. Haskell and Penny (Citation1981), no. 52, 243–7; Bober and Rubinstein (Citation1986), no. 122, 154–5; catalogue entries in Buranelli, Liverani, and Nesselrath (Citation2006), 119–200.

14. Vasari, Life of Sansovino (Citation1973) VII, 489; Buranelli, Liverani, and Nesselrath (Citation2006), 137–38, nos. 24–25; Boucher (Citation1991) II, for the lost competition cast, cat. no. 83, and for the Bargello version (427), cat. no. 4.

15. Barkan (Citation1999), 9, refers to the riddle of the Laocoon; Muth (Citation2017) the ‘statue-puzzle’.

16. Haskell and Penny (Citation1981), 246–7; Bourgeois (Citation2007), on its subsequent restoration history in Paris.

17. Vasari, Life of Montorsoli (Citation1973) VI, 633.

18. Winner (Citation1974) citing Giovanni de’ Cavalcanti’s 1506 letter suggesting that Laocoon originally held a spear in his right hand.

19. Magi (Citation1960); Rebaudo (Citation1999); Nesselrath (Citation1998); Laschke (Citation1998); Giuliani and Muth (Citation2017).

20. Muth (Citation2017) exhibited at Winckelmann Institut, Humboldt University, Berlin, 19 October 2016–31 July 2018, http://www.laokoon.hu-berlin.de/schule.html (accessed 12.12.17).

21. Greenberg (Citation1980).

22. Jenkins (Citation1998); Bourgeois (Citation2007).

23. Bober and Rubinstein (Citation1986), 122, along with the Apollo Belvedere.

24. Warwick (Citation2014).

25. Jenkins (Citation1994). On the question of Roman art as ‘copy’, Trimble and Elsner (Citation2006).

26. Winckelmann (Citation1985), 33, 42; Winckelmann (Citation2006), 206, 313–14.

27. Lessing (Citation1984), 15–19; Lifschitz and Squire (Citation2017).

28. Winckelmann (Citation2006), 314. Nisbet (Citation1979). Settis and Maffei (Citation1999) publishes Sadoleto’s verse that Winckelmann refers to, 118–21.

29. Von Goethe (Citation1980); Richter (Citation1992).

30. Frederickson and Marchand (Citation2010) especially the essays by Malone and Dyson; Smailes (Citation1991).

31. Fried (Citation1986).

32. Malvern (Citation2010); Herrmann Citation2017–18.

33. Frederiksen and Marchand (Citation2010).

34. Babbit (Citation1910).

35. Settis (Citation2003), 269–301.

36. Greenberg (Citation1980).

37. Settis (Citation2003) and Settis, cat.nos. 91–101, in Buranelli, Liverani, and Nesselrath (Citation2006), 192–200; Curtis and Feeke (Citation2007); Schuster and Vogler (Citation2017).

References

- Argan, G. C. 1967. “Il valore critico della stampa di traduzione.” In Essays in the History of Art Presented to Rudolf Wittkower, edited by D. Fraser and M. J, Lewine, 179–181. London: Phaidon.

- Babbit, I. 1910. The New Laokoon: An Essay on the Confusion of the Arts. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Bakhtin, M. 1968. Rabelais and His World. Translated by H. Iswolsky. Cambridge MA: MIT Press.

- Barkan, L. 1999. Unearthing the Past: Archaeology and Aesthetics in the Making of Renaissance Culture. London & New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Barocchi, P., ed. 1998. Pittura e Scultura nel Cinquecento: Vincenzo Borghini, Benedetto Varchi. Leghorn: Sillabe.

- Barthes, R. 1957. Mythologies. Paris: Editions du Seuil.

- Barthes, R. 1977. Image: Music: Text. S. Heath trans. and ed. London: Fontana.

- Black, P., and G. Warwick. 2014. Picturing Venus in the Renaissance Print. Glasgow: Hunterian.

- Bober, P. P., and R. Rubinstein. 1986. Renaissance Artists & Antique Sculpture: A Handbook of Sources. London: Harvey Miller.

- Boschloo, A., ed. 1989. Academies of Art between Renaissance and Romanticism. Leids Kunsthistorisch Jahrboek. ‘S. Gravenhage: SDU Uitgeverij.

- Boucher, B. 1991. The Sculpture of Jacopo Sansovino. Vol. 2. London & New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Bourgeois, B. 2007. “The French Laocoon: An Impossible Restoration.” In Towards a New Laocoon, edited by P. Curtis and S. Feeke, 25–28. Leeds: Henry Moore Institute.

- Brown, B., ed. 2004. Things. Chicago & London: University of Chicago Press.

- Buranelli, P., P. Liverani, and A. Nesselrath, ed. 2006. Laocoonte: Alle Origini Dei Musei Vaticani, Quinto Centenario Dei Musei Vaticani, 1506–2006. Vatican City: Vatican Museums.

- Curtis, P., and S. Feeke, eds. 2007. Towards a New Laocoon. Leeds: Henry Moore Institute.

- de Saussure, F. 2011. Course in General Linguistics. (1916) trans. W. Baskin. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Deleuze, G. 1968. Différence et Répétition. Paris: Presse universitaire de France.

- Dolce, L. 1557. Dialogo della pittura intitolato l’Aretino. Venice: G. G. de Ferrari.

- Eco, U. 1976. A Theory of Semiotics. London: Indiana University Press.

- Frederiksen, R., and E. Marchand, eds. 2010. Plaster Casts: Making, Collecting and Displaying from Classical Antiquity to the Present. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

- Fried, M. October 1986. “Antiquity Now: Reading Winckelmann on Imitation.” October 37 (Summer issue): 87–97. doi:10.2307/778521.

- Gilio, G. A. 1564. Due Dialogi. Camerino: A. Gioioso.

- Giuliani, L., and S. Muth. 2017. “Der (re)konstruierte Laokoon im 16. Jahrhundert: Die Dynamik des Transformationsprozesses.” In Laokoon: Auf der Suche nach einem Meisterwerk, edited by S. Muth, 129–160. Berlin: Humboldt University Winckelmann Instituts.

- Greenberg, C. 1980. “Towards a Newer Laocoon.” (Partisan Review July-August 1940) the Collected Essays and Criticism, edited by J. O’Brian. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Greene, T. M. 1982. The Light in Troy: Imitation and Discovery in Renaissance Poetry. London & New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Haskell, F., and N. Penny. 1981. Taste and the Antique: The Lure of Classical Sculpture, 1500–1900. London & New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Herrmann, D. F., ed. 2017–18. Eduardo Paolozzi. Exh. Cat. London: Whitechapel Gallery and Berlin: Berlinische Galerie.

- Isager, J. 2013. Pliny on Art and Society: The Elder Pliny’s Chapters on the History of Art. New York: Routledge.

- Jakobson, R. 1959. “On Linguistic Aspects of Translation.” In On Translation, edited by R. A. Brower, 232–239. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Jenkins, I. 1994. The Parthenon Frieze. London: British Museum Press.

- Jenkins, I. 1998. “Gods without Altars: The Belvedere in Paris.” In Il Cortile delle Statue: Der Statuenhof des Belvedere im Vatikan, edited by M. Winner, et al., 459–470. Rome: Akten des Internationalen Kongresses zu Ehren von Richard Krautheimer. Accessed 21–23 October 1992. Mainz: Philipp von Zabern.

- Landau, D., and P. Parshall. 1994. The Renaissance Print, 1470–1550. London & New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Laschke, B. 1998. “Die Arme des Laokoon.” In Il Cortile delle Statue: Der Statuenhof des Belvedere im Vatikan, edited by M. Winner, et al., 175–186. Rome: Akten des Internationalen Kongresses zu Ehren von Richard Krautheimer. Accessed 21–23 October 1992. Mainz: Philipp von Zabern.

- Lee, R. W. 1940. “’Ut Pictura Poesis’: The Humanist Theory of Painting.” The Art Bulletin XXII 4: 197–269. doi:10.1080/00043079.1940.11409319.

- Lessing, G. E. 1984. Laocoon: An Essay on the Limits of Painting and Poetry (1767). Translated by E.A. McCormick. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Lifschitz, A., and M. Squire, eds. 2017. Rethinking Lessing’s Laocoon: Antiquity, Enlightenment, and the ‘Limits’ of Painting and Poetry. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lomazzo, G. P. 1584. Trattato dell’arte della pittura. Milan: P.G. Pontio.

- Magi, F. 1960. “Il ripristino del Laocoonte.” Memorie/Pontificia Accademia Romana di Archeologia IX 1: 5–117.

- Malvern, S. 2010. “Outside In: The Afterlife of the Plaster Cast in Contemporary Culture.” In Plaster Casts: Making, Collecting and Displaying from Classical Antiquity to the Present, edited by R. Frederickson and E. Marchand, 351–358. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

- Mitchell, W. J. T. 1986. Iconology: Image, Text, Ideology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Muth, S., ed. 2017. Laokoon: Auf Der Suche Nach Einem Meisterwerk, Berlin: Humboldt University Winckelmann Instituts. Exhibited 19 October 2016–31 July 2018. Accessed 12 December 2017. http://www.laokoon.hu-berlin.de/schule.html

- Nesselrath, A. 1998. “Montorsolis Vorzeichnung für seine Ergänzung des Laokoon.” In Il Cortile delle Statue: Der Statuenhof des Belvedere im Vatikan, edited by M. Winner, B. Andreae, and C. Pietrangeli, 165–174. Rome. Akten des Internationalen Kongresses zu Ehren von Richard Krautheimer. Accessed 21–23 October 1992. Mainz: Philipp von Zabern.

- Nisbet, H. B. 1979. “Laocoon in Germany: The Reception of the Group since Winckelmann.” Oxford German Studies 10 (1): 22–63. doi:10.1179/ogs.1979.10.1.22.

- Panofsky, E. 1960. Renaissance and Renascences in Western Art. Stockholm: Almquist & Wiksell.

- Peirce, C. S. 1960-66. Collected Papers. Vol. 8 vols. eds. C Hartshorne and P Weiss. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press.

- Pevsner, N. 1940. Academies of Art, past and Present. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press and Macmillan.

- Pon, L. 2004. Raphael, Dürer, and Marcantonio Raimondi: Copying and the Italian Renaissance Print. London: Yale University Press.

- Rebaudo, L. 1999. “I restauri del Laocoonte.” In Laocoonte: Fama e stile, edited by S. Settis, 231–258. Rome: Donzelli.

- Richter, S. J. 1992. “The End of Laocoon: Pain and Allegory in Goethe’s ‘Uber Laokoon’.” Goethe Yearbook 6 (1): 123–141. doi:10.1353/gyr.2011.0301.

- Schuster, G., and H. Vogler. 2017. “Ein antikes Meisterwerk in der Moderne: Aneignung und Transformation der Laokoongruppe in der Kunst und Alltagskultur des 20. und 21. Jahrhunderts.” In Laokoon: Auf der Suche nach einem Meisterwerk, edited by S. Muth, 279–287. Berlin: Humboldt University Winckelmann Instituts.

- Settis, S. 2003. “La Fortune De Laocoon Au XXe Siѐcle.” Le Laocoon: histoire et reception, Revue Germanique Internationale 19: 269–301.

- Settis, S. 2004. Futuro del ‘classico’. Turin: Einaudi.

- Settis, S. 2015. “Supremely Original: Classical Art as Serial, Iterative, Portable.” In Serial/portable Classic, S. Settis, A. Anguissola, and D. Gasperotto, edited by, 51–72. Milan: Fondazione Prada.

- Settis, S., and S. Maffei, eds. 1999. Laocoonte: Fama e stile. Rome: Donzelli.

- Smailes, H. 1991. ““A History of the Statue Gallery at the Trustees’ Academy in Edinburgh and the Acquisition of the Albacini Casts in 1838.” Plaster and Marble: The Classical and Neo-Classical Portrait Bust, Ed. Glenys Davies, Special Issue.” Journal of the History of Collections 3 (2): 125–143. doi:10.1093/jhc/3.2.125.

- Summers, D. 1984. Michelangelo and the Language of Art. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Trimble, J., and J. Elsner. 2006. “Art and Replication: Greece, Rome and Beyond, Special Issue.” Art History 29 (2).

- Vasari, G. 1973. Le vite. Vol. 8 vols. (Florence 1568), G Milanesi ed. Florence: Sansoni.

- Viljoen, M. 2007. “Laocoon’s Snakes: The Reception of the Group in Renaissance Italy.” In Towards a New Laocoon, edited by P. Curtis and S. Feeke, 21–24. Leeds: Henry Moore Institute.

- von Goethe, J. W. 1980. “Uber Laokoon.” In Goethe on Art, edited by J. Gage, 78–88. Propyläen, I, I, 1798. London: Scolar Press.

- Warwick, G. 2014. “Recollecting Venus.” In Picturing Venus in the Renaissance Print, edited by P. Black and G. Warwick, 7–23. Glasgow: Hunterian.

- Warwick, G. 2017. “Memory’s Cut: Caravaggio’s Sleeping Cupid of 1608.” Image and Memory 4 (40): 884–903. G. Parkinson and G. Warwick, eds., special issue, Art History.

- Winckelmann, J. J. 1985. “Gedanken Über Die Nachahmung Der Griechischen Werke in Der Malerei Und Bildhauerkunst (1755), “Thoughts on the Imitation of the Painting and Sculpture of the Greeks.” In German Aesthetic and Literary Criticism: Winckelmann, Lessing, Hamann, Herder, Schiller, Goethe, edited by H. B. Nisbet, 29–54. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Winckelmann, J. J. 2006. Geschichte Der Kunst Des Alterthums (1764), History of the Art of Antiquity. trans. H. Mallgrave intro. A. Potts, Getty Research Institute Publications: Texts & Documents. Los Angeles: Getty Publications.

- Winner, M. 1974. “Zum Nachleben des Laokoon in der Renaissance.” Jahrbuch der Berliner Museen XVI: 83–121. doi:10.2307/4125704.

- Winner, M., B. Andreae, and C. Pietrangeli, eds.. 1998. Il Cortile delle Statue: Der Statuenhof des Belvedere im Vatikan. Rome: Akten des Internationalen Kongresses zu Ehren von Richard Krautheimer. Accessed 21 –23 October 1992. Mainz: Philipp von Zabern.