ABSTRACT

The role of interpreters has been shaped by changing social contexts throughout the millennial history of this occupation, but demographic, educational, legal and technological developments have accelerated since the late 20th century and given rise to new forms of interpreting with the potential of reshaping the way interpreting is conceived. This essay aims at providing a broad-based overview of major changes (‘shifts’) with regard to such features as social status and domain, mode and modality as well as process-related characteristics like human agency, immediacy and the nature of the language(s) involved. In particular, the looming transformations engendered by technological progress will be analysed with regard to the interplay between humans and machines. Under the headings of immediacy, linguality and agency, new forms of technology-based interpreting will be discussed and seen to challenge deeply rooted assumptions about interpreting as a task, with far-reaching consequences for the role of the human agent.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

Reflection on interpreting as a special form of translational activity has a relatively short history ‒ unlike the performance of that activity itself, which can be traced back thousands of years. Reflecting on the interpreter’s role(s) ‘in a changing environment’, as the title of the present collection encourages us to do, therefore prompts us to consider the relevant time frame. We could adopt a long-range historical perspective, or else focus on the present-day situation and current developments. Although my focus will be on the latter, the former will also be referred to briefly in order to point to the broad scope in which this topic would deserve to be discussed.

Change is obviously not a new phenomenon, but ongoing and pervasive at all times. Indeed, the idea of changes in the interpreter's environment seems so broad and general as to make it impossible to undertake a more systematic analysis. I will therefore resort to the notion of ‘shift’ in the sense of a more radical change of emphasis or direction. Rather than pathways, trends or turns, my guiding image will be that of a balance, or pair of scales, suggesting changes in relative weight, in the figurative sense of importance or prevalence. The image of a pair of scales implies a binary view, but it is also compatible with the notion of a continuum extending between opposite poles. The view of a continuum, or set of continua, was proposed for Translation Studies by Snell-Hornby (Citation1988) and also features prominently in my conception of interpreting studies (see Pöchhacker Citation2022, 25).

Against this background, I will begin by reviewing the criteria, or variables, which can be used to characterise the notion of interpreting in more or less binary terms. This requires a definition that can serve as a point of departure and a foundation for further conceptual analysis and discussion.

Definition(s) and features

A convenient way of defining interpreting is to construe it as ‘a form of Translation’, with a capital ‘T’ to indicate the hypernymic sense of translational activity. This embeds it in the universe of scholarship on this phenomenon and limits the task to specifying unique features (see Pöchhacker Citation2022, 11–13). The alternative is to formulate a definition that is more autonomous. For this I have suggested that ‘to interpret’, in the translational sense, most fundamentally means ‘to say what has just been said in another language’ (Pöchhacker Citation2019, 46), where ‘say’ is used in the broader sense of ‘express’ or ‘communicate’. Dictionary definitions seem less helpful here, when they define the intransitive form of ‘to interpret’ as ‘to act as an interpreter’ (e.g. Merriam-Webster Citation2019). For our purposes, though, this formulation is useful in reaffirming the intrinsic interrelation between a focus on interpreting and on the interpreter, that is, on the task and on the agent. As indicated in , the ‘task’ or activity as the primary reference point for the present discussion is inseparable from the ‘agent’ performing it; and the agent is in turn embedded in a given ‘context’ in which the activity of interpreting takes place and which variously shapes both the features of the task and the identity and role of the agent.

The notion of context is as central to the understanding of interpreting as it is poorly defined, so a few words of explanation are required. One widely accepted assumption is that the concept is multi-layered. Although its outer bounds would be difficult to determine, one can safely posit a sociocultural layer that puts the focus on interpreting in (a given) society. Viewing interpreting in particular social institutions (like the education or healthcare systems) yields an institutional layer of context, within which more specific settings can be identified. Within such (more or less generic) settings, the level of the situation comprises both the spatial and physical environment in which an interaction takes place and the agents involved in the interaction. Finally, the linguistic (communicative) layer of context relates to the expressive resources used in communicative interaction. These resources are multimodal and form a temporal continuum, so that what was expressed earlier shapes the production and comprehension of subsequent utterances. Depending on the theoretical framework adopted, this can be expressed by terms like ‘co-text’ or ‘prior context’. For the purpose of this discussion, however, the focus will be on ‘outer’ (social) rather than linguistic layers of context.

The situational layer of context also serves to clarify an important concept used later on in this discussion – that is, immediacy. In the above definition of interpreting, the phrase ‘what has just been said’ refers to immediacy in the temporal sense: interpreting, by definition, takes place in ‘real time’, as a communicative interaction unfolds. In modern parlance, interpreting happens ‘live’. What is more, the temporal immediacy characteristic of interpreting (as opposed to written translation) has traditionally implied also a ‘unity of place’. Interpreting has thus been construed as an activity taking place hic et nunc, here and now, with all those involved being co-present in a given situation.

Another important implication that can be derived from the definition presented above is the interlingual nature of the task. This, in turn, is linked to another principal assumption ‒ namely, that interpreting is performed by a human agent. In fact, any language use was long viewed as so intrinsically human as to preclude non-human agents. Where the notion of agency is used in interpreting studies, it usually refers to a human interpreter’s level of active involvement in the interaction. Agency, in this sense, closely relates to the theme of the interpreter’s role as discussed in particular for interpreting in community settings (e.g. Angelelli Citation2004). While the degree of the interpreter’s agency or role constitutes the main topic of this special issue, it is not central to the present discussion. Rather, my interest in the agent foregrounds the obvious implication of assuming that interpreting is an interlingual task – namely, that the fundamental requirement for the agent performing this task is to ‘know’ (i.e. to be more or less proficient in) at least two languages.

As will emerge later on, the nature of language(s) in the definition of interpreting is much more complex than it appears from the definition of interpreting as an interlingual task. Under the heading of linguality I will discuss how the fact that language exists in different modalities (spoken, written, signed) must also inform our understanding of interpreting.

Compared to the notions of immediacy and linguality, much less attention will be paid in this discussion to what is generally viewed as the defining feature of the translational task – that is, that the relationship between the two acts of saying is one of similarity or relevant sameness, mostly with regard to content rather than form. Though expressions like ‘equivalence’ or ‘fidelity’ are fraught (see e.g. Leal Citation2012), the assumption that interpreting is some kind of faithful rendering of what was said is largely unquestioned. The norm of the ‘honest spokesperson’ articulated by Harris (Citation1990, 118) seems uncontested. In a similar vein, Setton (Citation2015) points out that the conceptual space of faithfulness is multidimensional and extends all the way from accuracy and completeness to trust and reliability, relating to content as well as intent.

In addition to the set of defining criteria underlying an intensional definition of interpreting, there are a number of descriptive features pertaining to the agent, the task and the context. These can and have been used to distinguish different manifestations of interpreting, which constitute a rich and diverse conceptual field. Key examples include professional vs non-professional interpreting, consecutive vs simultaneous interpreting, and conference vs dialogue interpreting. It is mainly for these conceptual dimensions that some long-standing shifts in interpreting can be observed. I will briefly discuss these, in a necessarily broad-brush account, in the following section, examining individual features for shifts from one end of a continuum towards the other, and often in the opposite direction as well.

Previous shifts

At the broadest level of sociocultural context, the need for interpreters has arisen through the ages mainly in contacts between (members of) groups using different languages. Trade, diplomacy and warfare were important inter-social contact scenarios in which interpreters acted between (representatives of) societies and nations. This applies also to interpreting during most of the twentieth century, as reflected in the impressive professionalisation of international conference interpreting (Seleskovitch Citation1978). With the exception of multi-ethnic societies, empires and societies under colonial rule, a major shift in this regard only occurred in the latter part of the century. Increased international mobility and migration gave rise to more multilingual and multicultural societies, confronting in particular authorities in ‘Western’ welfare states with new communication (and interpreting) needs. The notion of community interpreting, which became current in the British context in the 1980s (see Pöchhacker Citation1999, 126), foregrounds that interpreting is taking place within a given (linguistically and culturally diverse) community.

As mentioned above, the shift from interpreting in contacts between nations to interpreting in contacts within societies has brought special attention to the complexities of the interpreter’s role: rather than representatives (of a state, an institution, a profession, etc.) of equal or comparable status, interpreting in the community essentially involves an individual person acting on his or her own behalf, typically in relation to the representative of an institution and the power derived from that institutional position. This asymmetry places special demands on the interpreter’s degree of active involvement in the interest of enabling communication.

The fundamental late-twentieth-century shift from the predominance of interpreting in the international sphere to interpreting in the intra-social sphere is associated with several other, partly interrelated shifts, which pertain to the profile of the agents as well as the nature of the task. In terms of the continua on which the various shifts are to be conceived, the reference here is to professional status, format of interaction, multilingualism and mode of interpreting.

In a long-range view, from Antiquity to the twentieth century, the most fundamental shift in the identity and status of interpreters is from chance bilinguals to authorised specialists. In the former case, the coincidental nature is twofold: acquiring two languages by chance, as a result of a given set of circumstances; and being called upon, by dint of circumstance, to act as interpreter. Well-known circumstances producing chance bilinguals – and hence chance interpreters – include enemy captivity and colonisation as well as various forms of migration. Specialist status, by contrast, normally arose only as a matter of policy, through deliberate measures in a given institutional framework. The jeunes de langues educated by Western powers for dealing with the Ottoman Empire (Rothman Citation2015) are a case in point.

Specialised training in task performance is undoubtedly a core element in the process of professionalisation. In this regard, the (second half of the) twentieth century stands out as the era when the status of interpreting shifted from a coincidental everyday activity to a professional occupation. Most of this professionalisation was linked to the profile of international conference interpreting, but since the late twentieth century other professional domains, from court interpreting to signed language interpreting, have shown a similar development.

The shift on the continuum of professional status, from none to that of a profession with a certain degree of autonomy, is closely associated with typical formats of interlingual interaction. For many centuries, language contact scenarios in the fields of trade and diplomacy as well as military affairs would have been mainly bilateral, taking place as a dialogue between two ‘sides’. Despite notable exceptions, such as councils of the Catholic Church or the Congress of Vienna in 1815, organised multilateral contacts and conferences were rare until the early twentieth century. Multilateralism does not necessarily imply, or require, multilingualism, but as recounted by Baigorri-Jalón (Citation2014, 19–24), the commitment to multilateralism in the aftermath of World War I indeed resulted in multilingualism at the level of institutions like the League of Nations and the International Labour Organization in Geneva. A lack of multilingualism in the individuals taking part in international conferences then gave rise to the need for (conference) interpreting, so that the shift from bilateral dialogue to multilateral conferencing came to underpin the professionalisation of conference interpreters.

Roughly a century later, the spread of individual multilingualism, mostly including English, began to reverse the twentieth-century shift towards multilingual multilateral conferencing using interpreters. With English firmly established as the dominant lingua franca in nearly all walks of life and regions of the world, multilateral contacts (conferences) began to revert to pre-twentieth-century practices of lingua franca use, with a more limited need for interpreting, often between a given language and English as a lingua franca. At the same time, the widespread emergence of dialogue interpreting in the community could be said to amount to an overall shift (back) from conference to dialogue settings as well as a ‘return’ to the predominance of interpreting in bilingual communication scenarios.

The shifts discussed above can also be related to the (temporal) mode in which interpreting is practiced. Once again, the move towards multilingual multilateral conferencing in the twentieth century played a decisive role in the shift from consecutive to simultaneous interpreting, which in turn gave a major impetus to training efforts as well as early research.

It is in this connection that technology first made itself felt as a key factor shaping interpreting practices. In parallel, the overall shift to simultaneous interpreting (SI) was also reinforced by the growing institutionalisation of signed-language interpreting services.

When hundreds of years of interpreting since ancient times are contrasted with interpreting practices in the twentieth century, the shift from consecutive to simultaneous is as obvious as it is fundamental. But when the focus is set to the past fifty years or so, the shift seems to have occurred also in the opposite direction, from SI back to the consecutive mode. Much of this stems from the interrelated developments discussed above, that is, the shift from international to community-based communication needs met by chance interpreters rather than professionals in face-to-face dialogue rather than conference-like situations. Interestingly, technology is at play here, too. The use of telephone equipment for interpreting, for instance, which began in the 1970s, has compelled interpreters to work in consecutive mode, and this also applies to more recent technology-mediated forms of interpreting that will be referred to in the following discussion of current shifts. Unlike the shifts reviewed above, which involved descriptive features of the task, the shifts discussed in the following three sections, under the headings of immediacy, linguality and agency, concern defining features of the concept of interpreting.

Immediacy

Except for the past 100 years, (spoken-language) interpreting has been practiced without recourse to any media other than the soundwaves required to produce speech. In this sense, interpreting was essentially un-mediated, and required all interacting parties to be ‘within earshot’, co-present in a given situation. Immediacy in the sense of physical co-presence is therefore a deeply rooted assumption of interpreter-mediated communication. Although efforts in the mid-1920s to implement ‘telephonic’ interpretation (Baigorri-Jalón Citation2014, 137) began to undermine the assumption of interpreters’ physical presence in the meeting room, it was only in the second half of the twentieth century that the idea of interpreters working from a remote site started to gain ground. Alongside the introduction and use of telephone interpreting, first in Australia and then in the United States and in some European countries, remote interpreting (RI) in audiovisual mode got under way in the 1970s. However, RI based on videoconferencing remained subject to technological (and financial) limitations until the 1990s (Mouzourakis Citation1996). Thanks to the rapid expansion of broadband internet over the past decades, video-mediated interpreting has become viable in community-based settings as well as international conferences (see e.g. Braun Citation2015). Not surprisingly, sign language interpreting, which relies primarily on the visual channel, played a pioneering role in the widespread adoption of video remote interpreting (VRI) (see Napier Citation2022; Napier, Skinner, and Braun Citation2018).

Video-mediated RI between spoken languages has since developed in three different strands: (1) in traditional on-site meetings, SI is delivered via a videoconference, with image transmission only to the interpreter; examples include EU Council Dinners and sports-related events (e.g. Seeber et al. Citation2019); (2) when remote simultaneous interpreting (RSI) is delivered via a virtual platform and most or all participants connect via an audiovisual interface, the simultaneous interpreter need not remain an only vocal presence, even though this is how RSI is implemented in most SI delivery platforms; (3) in videoconference-based remote dialogue interpreting, image transmission is in fact bidirectional, but the interpreting is done in consecutive mode. What is worth noting here are the implications of these arrangements for the immediacy of interpreting and for interpreters’ sense of 'presence'. Interestingly, RI types 1 and 3 tend to use videoconferencing technology in a way that approximates on-site conditions: SI output remains audio only, while dialogue interpreters working in consecutive mode retain a visual as well as an acoustic presence. Type 2 therefore constitutes the most radical innovation, as it forms part of a new kind of virtual meeting space in which communicative interaction is technologically mediated for all participants. Future developments along these lines will have major consequences for the way interpreters are present and ‘presented’ to other participants in the interaction. In RSI, the technology that overcame the boundaries of spatial immediacy could thus serve to restore a much greater immediacy to the interpreter’s presence (albeit technologically mediated); in VRI, on the other hand, a switch to dialogue interpreting in simultaneous mode (see Pöchhacker Citation2014) could reduce the community interpreter to an only vocal presence, since participants’ visual monitoring would presumably be directed to their immediate interlocutors.

Aside from the spatial sense discussed up until now, the notion of immediacy is understood more typically in a temporal sense, as conveyed in such technical terms as ‘live’ or ‘in real time’. Here again the use of digital technology for the transmission and storage of (spoken as well as signed) language data poses a challenge to the defining criterion that the source message in interpreting is available only once (Kade Citation1968; Pöchhacker Citation2022). In the working mode of recording-based simultaneous consecutive (Pöchhacker Citation2015), for instance, the source speech is actually heard twice. In a similar vein, the previewing of video material by simultaneous interpreters is common practice in news interpreting. While Tsuruta (Citation2011) describes well-established practices for this at Japan’s national broadcaster NHK, Xiao, Chen, and Palmer (Citation2015) discuss insufficient preparation time as a factor impeding the effectiveness of simultaneous interpreting of news broadcasts into Chinese Sign Language.

In summary, ongoing technological developments, mainly in connection with videoconferencing, have been pushing the conceptual boundaries of interpreting. Once defined by its immediacy in the spatial as well as the temporal sense, interpreting, or some forms of it, can no longer be said to take place ‘here and now’. Rather, interpreters may be incorporated into a fragmented virtual space and/or transcend ‘real time’ through reliance on digital sound and image transmission, recording and replay technologies.

Linguality

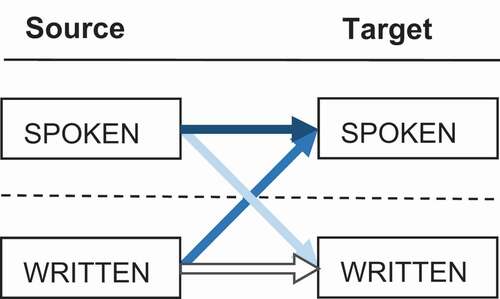

As mentioned in the introductory section on definitions, the term ‘linguality’ is used here to denote the medium of language use as well as the nature of linguistic conversion. In his proposal for a way to distinguish interpreting from translation, Kade (Citation1968) foregrounds the criterion of immediacy rather than the spoken or written modality of language. His parenthetical note that the source text in interpreting is ‘usually’ oral leaves room for other possibilities and does not strictly equate interpreting with speech-to-speech or oral translation (which some languages enshrine in their basic terminology). This far-sighted choice is borne out by the fact that recent ISO standards define ‘to interpret’ as rendering ‘spoken or signed’ information ‘in oral or signed form’ (e.g. ISO Citation2019). In line with pioneering authors such as Herbert (Citation1952) and Shiryaev (Citation1979), Kade (Citation1968) in fact also accommodates what is traditionally called sight translation (i.e. the spoken rendering of a written source-language text) in his concept of interpreting, which current ISO standards regrettably fail to do. This choice is significant, as it relates not only to the inclusion (or exclusion) of a working mode that is typically seen as belonging to an interpreter’s skill set, but also stresses that interpreting may involve a shift in linguistic modality. The principle of cross- or intermodality as such is evidently accepted also in the ISO definition, since messages in signed languages are mostly interpreted into spoken ones and vice versa. When the focus is on the distinction between spoken and written language, acceptance of intermodality would also suggest that writing can be a part of the interpreting process. This is indicated in by the arrow pointing from a written source to a spoken target text. While the colour of the arrows is an attempt to reflect prototypical conceptualisations, there is also an arrow linking spoken source texts to written source texts, and even the suggestion of a written-to-written modality, exemplified by the instantaneous translation of live chat messages.

Though it seems unusual to expect an interpreter (working in real time) to render spoken messages into written text, the proposal for this working mode was actually put forward by Eva Paneth (best known as the author of the first MA thesis on conference interpreting) in the 1980s. What she described as ‘projected interpretation’, long before the advent of video projectors for presentation slides, corresponds to simultaneous speech-to-text interpreting, with the writing done manually on devices as technologically modest as overhead projectors. Modern-day versions of this practice use computer keyboards, stenographic keyboards or speech recognition systems (Stinson Citation2015). Such speech-to-text interpreting is an increasingly common practice, but done for a specific purpose and user group, namely, deaf or hard-of-hearing (DHH) persons requiring access to spoken messages in educational settings or at live events. Crucially, this communication access service, which is also referred to as voice writing or live captioning, is normally done intralingually, transforming a spoken message into a written text in the same language. Subsuming speech-to-text interpreting under the concept of interpreting thus clashes with the defining feature of interlinguality, raising issues of terminology as well as more fundamental arguments about conceptual boundaries.

As in the case of interpreting being designated as ‘oral translation’, the way a set of conceptual features is categorised and expressed in language depends, among other things, on available lexical resources. While this can make the terminological distinction between translation and interpreting more difficult, it may also obviate the need for it, as different forms of translational activity are subsumed under a single hyperonym. In the case at hand, one could simply talk about ‘speech-to-text translation’ with an additional qualifying term like ‘real-time’, ‘live’ or ‘simultaneous’. At this generic level, the terminological issue can most easily be resolved with reference to Jakobson’s (Citation1959/2000) threefold distinction between intralingual, interlingual and intersemiotic translation procedures. And if intralingual translation is accepted as translation, the same would apply to interpreting, when an autonomous term for it exists. Conceptually at least, intralingual interpreting should be nothing strange; doubt or even resistance are more likely to arise from professional groups with an interest in maintaining a clearly defined competence profile. At the same time, the interests of social groups can also serve to make the case for an integrated terminological, and possibly even professional approach: though a much more diverse group than the label ‘DHH’ might suggest, persons with a hearing impairment require access services depending on the nature and degree of their hearing loss. This may mean interpreting into their native or acquired sign language or into a signed variety of the spoken majority language (‘transliteration’) ‒ or else into the written mode of that language. Those providing such access services could in all cases be regarded as interpreters, and – subject to the necessary training – may even be the same individuals.

Deaf persons as a particular user group of interpreting services may also benefit from a type of interpreting that also has special relevance for the purpose of this paper: Deaf interpreters (see Stone Citation2015) may work in relay mode to adapt a hearing interpreter’s non-native signing to the needs of native deaf users. In this case, interpreting is both intramodal and intralingual, serving the communication access needs of a particular target group through the process of interpreting.

Yet another example in this regard is interpreting into easy-to-understand language, a rather recent extension of (re)translating written texts for the benefit of persons with cognitive impairments. Done in real time, this intramodal process (speech to speech) combines the inherent immediacy of interpreting with a specific target user orientation.

Whether intra- or intermodal, all these intralingual forms of interpreting constitute a challenge to the definition of interpreting formulated at the outset of this discussion. Stipulating that the interpreter’s act of re-expression is done ‘in another language’ establishes a conceptual boundary that excludes intralingual forms of interpreting. The shift from interpreting as an exclusively interlingual practice to the inclusion of intralingual variants marks a radical departure from the centuries-old understanding of this activity, much more so, apparently, than the shifts away from immediacy and intramodality. This may have to do with the implications of these shifts in linguality for the deeply rooted assumption of bilingual competence. After all, intralingual speech-to-text interpreting and interpreting into easy-to-understand language can be done perfectly well by a monolingual individual, as demonstrated also by Deaf interpreters. Relinquishing the requirement that an interpreter must ‘speak’ (understand/know/command) at least two languages admittedly amounts to a conceptual upheaval; as demonstrated above, however, the shifts underlying this move are well under way, and broader social acceptance of this redefinition is conceivable as long as other defining features of interpreting, such as real-time performance and faithful re-expression, are deemed to remain stable. The redefinition as such can be accomplished quite easily: by shortening only one word in the definition given at the beginning of this article, the requirement of interlinguality (‘in another language’) can be loosened, at least in English, to stipulate ‘in other language’.

Moreover, reconciling intralingual interpreting with more traditional assumptions may be aided by the fact that all its variants (except for Deaf relay interpreting) can, in principle, be performed also interlingually (see Davitti and Sandrelli Citation2020; Dawson and Romero-Fresco Citation2021). Interlingual live subtitling is being used by broadcasters in Belgium, for instance, and interlingual speech-to-text interpreting was showcased at an international EU project conference held in early 2019 at the University of Vienna, where presentations in English (on a training course in interlingual live subtitling) were simultaneously rendered into German subtitles for the benefit of local deaf participants (). It is worth noting that the professional who performed this service is a university-trained and practicing spoken-language conference interpreter as well as a certified (intralingual) speech-to-text interpreter.

Agency

Many of the recent shifts in the nature of interpreting have become possible only through the use of digital technologies. Simultaneous consecutive and such forms of distance interpreting as RSI and VRI are cases in point. Nevertheless, task performance in all of these technologically mediated types of interpreting rests essentially on a human agent. This begins to change with speech-to-text interpreting relying on speech recognition technology, which is in fact a two-stage process: the first stage is an intramodal human processing task that can be either intra- or interlingual, referred to as ‘respeaking’ (Romero-Fresco Citation2011) and ‘transpeaking’ (Pöchhacker and Remael Citation2019), respectively; the second is an intermodal (speech-to-text) conversion delivered by the automatic speech recognition (ASR) system. Unless the respeaker or transpeaker, who provides the input to the ASR system, manages to monitor and, if necessary, correct the ASR output, part of the ultimate product received by the users will no longer have been created by the human agent.

Depending on further progress in ASR and speech processing technology, the first stage of the process may be taken over by the machine, turning intralingual speech-to-text interpreting into a fully automatic single-stage process. (For the interlingual form, the ASR output would need to be fed into a machine translation engine.) More realistically, the text output by the machine will require human post-editing, at least in scenarios requiring consistent high quality. In this setup the process once again comprises two stages, but the core task is accomplished by the machine, whereas the human agent takes care of the finishing.

Finally, when the ASR and machine translation systems required for interlingual speech-to-text interpreting are complemented by a speech synthesiser converting text to speech, the entire interpreting process, proceeding in three main steps, is completed by the machine. (This account is evidently based on the traditional cascade model of machine interpreting, irrespective of ongoing efforts to achieve ‘end-to-end’ speech translation.) Where a certain level of quality is required for more complex material, such fully automatic speech-to-speech translation (FAST) would presumably still require human post-editing. This would amount to a corrective process of shadowing (Riccardi Citation2015) on the part of the (intralingual) simultaneous interpreter. Interlingual interpreting, in this scenario, would still be a compound process, with the machine performing the interlingual task and the human agent, working intralingually, creating a more user-friendly final version. Though the arrangement might seem futuristic, it is, in principle, comparable to what is done when a Deaf interpreter takes relay from a hearing colleague who works from a native spoken into an acquired signed language. And on a broader level, such arrangements for the performance of interpreting tasks are of a similar nature as machine translation use in general. What was once an intrinsically and entirely human achievement is now accomplished by harnessing the computing power of machines.

On balance

The present effort to describe changes in the conceptualisation and professional practice of interpreting in terms of shifts suffers from several limitations. Most obviously, the idea of binary features is an oversimplification, and the discussion privileges features that lend themselves to a dichotomous view and avoids more graduated changes, such as the move of conference interpreters’ workplace from the booth to a hub and to their home. As noted in particular in relation to past shifts, such changes do not necessarily move in only one direction but may be reversible, as in the image of the swing of the pendulum. Then there is the questionable distinction between what is ‘past’ and what is ‘current’. While the latter can be taken to mean ‘ongoing’, some of the shifts discussed may go back several decades, whereas others are only just emerging. Moreover, the ‘analysis’ of previous and current shifts is not based on quantitative indicators or measurements but on impressionistic generalisations that are informed by the professional and academic literature as well as long-term observation of developments in professional practice. Ideally, some parts of this series of simplified sketches could be examined on the basis of systematically collected empirical data.

Mindful of these caveats, the various shifts identified in this essay lend themselves to some broader conclusions regarding the nature of interpreting and the role and identity of interpreters. First and foremost of these is the truism that interpreting is not a stable, uniform phenomenon but has repeatedly undergone major changes in the course of its millennial history. Its embeddedness in evolving social practices and ever-changing contexts make this a matter of course. What is clearly different in our days compared to earlier times is the pace and scope of change. The shifts from untrained to professional interpreters and from consecutive to simultaneous interpreting, which can be viewed as two interrelated dimensions, may be less than a hundred years old, but led to a phase of relative stability in the twentieth century. More recent changes, in contrast, involve additional dimensions, often in combination, and give rise to practices that may soon be superseded by new developments. The move from keyboard-based captioning to respeaking-based speech-to-text services and to automatic speech recognition with post-editing, alongside the introduction of interlingual speech-to-text interpreting, can serve as a case in point. Moreover, the fact that changes are more multidimensional is likely to make their results more susceptible to further change.

Yet another reason why ongoing changes are felt to be particularly far-reaching have to do with the conceptual features involved: rather than descriptive distinctions ‒ concerning, for instance, the type of setting or format of interaction in which interpreting is performed, some shifts affect deeply rooted defining features of interpreting as such. Rather than shifts away from spatial immediacy, which are seen as changing the delivery mode but not the substance of interpreting services, some essential shifts can be observed under the heading of linguality, namely, that the outcome of the interpreting process may be in the written modality of language and that the process may be intra- rather than interlingual, with the significant implication that an interpreter need not be proficient in two or more languages but might in fact be monolingual.

Multi- or monolingual, the interpreters performing such intermodal intralingual tasks are still human beings, though the nature of their work, and hence their social and professional role, would be redefined: rather than foregrounding the real-time processing of two different languages, interpreters would be conceived as providing real-time access services which allow specific target users to overcome barriers to communication, be they linguistic, cultural, cognitive or sensory.

Finally, interpreters’ increasing reliance on digital technologies in performing their task introduces a non-human component into the interpreting process. Whether designated as machines or as computer software, such technologies can be employed to merely support the human interpreting process, to largely replace it, or, in simpler applications, to leave no more room for human agency. This shift from human to machine is surely the ultimate and most drastic shift in our understanding of the interpreter’s identity. And yet, it would not make the cognitive and affective skills of the human interpreter redundant. On the contrary, human monitoring and post-editing will without doubt remain indispensable in many high-stakes scenarios, where people’s lives and liberties are at stake. Much more fundamentally, though, current neural machine translation systems essentially draw on and learn from recorded human interpreting performances. If FAST systems are to keep up with evolving linguistic norms and creative language use, the input of interpreters providing situated communication solutions geared to a specific context and purpose will remain vital. Despite changing contexts and needs, and variable degrees of reliance on technology, interpreting will continue to imply a role for the human agent. As this discussion has sought to show, we can simply not be sure how this role is going to evolve.

Disclosure statement

My conflict of interest is of a personal and political nature. This essay, based on a plenary conference talk, found its way into print in this journal exactly 20 years after the academic boycott which Mona Baker, the founding editor of this journal, launched in 2002 against scholars affiliated with Israeli institutions. Miriam Shlesinger, a member of the editorial board, was forced to step down for these political reasons. Several colleagues, including myself, resigned in protest from their roles in this journal. Publishing once again in this journal must therefore come with the explicit affirmation that the boycott action is not forgotten nor forgiven. On the contrary, I trust that Taylor & Francis as a professional publisher will continue to make sure that divisive political action has no place ever again in a scholarly journal of translation and interpreting studies.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Franz Pöchhacker

Franz Pöchhacker is Professor of Interpreting Studies in the Centre for Translation Studies at the University of Vienna. With professional training and experience in conference interpreting, his interests have expanded over the years to include issues of interpreting studies as a discipline, media interpreting and community interpreting in healthcare, social service and asylum settings. His more recent work involves such technology-based forms of interpreting as video remote and speech-to-text interpreting. He has lectured and published widely, his English books including The Interpreting Studies Reader (2002), Introducing Interpreting Studies (2004/32022) and the Routledge Encyclopedia of Interpreting Studies (2015). He is co-editor, with Minhua Liu, of Interpreting: International Journal of Research and Practice in Interpreting.

References

- Angelelli, C. V. 2004. Revisiting the Interpreter’s Role: A Study of Conference, Court, and Medical Interpreters in Canada, Mexico, and the United States. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Baigorri-Jalón, J. 2014. From Paris to Nuremberg: The Birth of Conference Interpreting (transl. by Holly Mikkelson and Barry S. Olsen). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Braun, S. 2015. “Remote Interpreting.” In The Routledge Handbook of Interpreting, edited by H. Mikkelson and R. Jourdenais, 352‒367. London/New York: Routledge.

- Davitti, E., and A. Sandrelli. 2020. “Embracing the Complexity: A Pilot Study on Interlingual Respeaking.” Journal of Audiovisual Translation 3 (2): 103–139. doi:10.47476/jat.v3i2.2020.135.

- Dawson, H., and P. Romero-Fresco. 2021. “Towards Research-informed Training in Interlingual Respeaking: An Empirical Approach.” The Interpreter and Translator Trainer 15 (1): 66–84. doi:10.1080/1750399X.2021.1880261.

- Harris, B. 1990. “Norms in Interpretation.” Target 2 (1): 115–119. doi:10.1075/target.2.1.08har.

- Herbert, J. 1952. The Interpreter’s Handbook: How to Become a Conference Interpreter. Geneva: Georg.

- ISO. 2019. ISO 20539: Translation, Interpreting and Related Technology ‒ Vocabulary. Geneva: International Organization for Standardization.

- Jakobson, R. 19592000. “On Linguistic Aspects of Translation.” In The Translation Studies Reader, edited by L. Venuti, 113‒118. London/New York: Routledge.

- Kade, O. 1968. Zufall und Gesetzmäßigkeit in der Übersetzung. Leipzig: Verlag Enzyklopädie.

- Leal, A. 2012. “Equivalence.” In Handbook of Translation Studies, Vol. 3, edited by Y. Gambier and L. van Doorslaer, 39‒46. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Merriam-Webster 2019. “Interpret”. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/interpret (accessed 11 November 2019

- Mouzourakis, P. 1996. “Videoconferencing: Techniques and Challenges.” Interpreting 1 (1): 21‒38.

- Napier, J. 2022. “Review of Linking up with Video (Salaets and Brône, eds, 2020).” Interpreting 24 (1): 147‒154.

- Napier, J., R. Skinner, and S. Braun, eds. 2018. Here or There: Research on Interpreting via Video Link. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press.

- Pöchhacker, F. 1999. “‘Getting Organized’: The Evolution of Community Interpreting.” Interpreting 4 (1): 125‒140.

- Pöchhacker, F. 2014. “Remote Possibilities: Trialing Simultaneous Video Interpreting for Austrian Hospitals.” In Investigations in Healthcare Interpreting, edited by B. Nicodemus and M. Metzger, 302‒325. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press.

- Pöchhacker, F. 2015. “Simultaneous Consecutive.” In Routledge Encyclopedia of Interpreting Studies, edited by F. Pöchhacker, 381‒382. London/New York: Routledge.

- Pöchhacker, F. 2019. “Moving Boundaries in Interpreting.” In Moving Boundaries in Translation Studies, edited by H. V. Dam, M. N. Brøgger, and K. K. Zethsen, 45‒63. London/New York: Routledge.

- Pöchhacker, F. 2022. Introducing Interpreting Studies. Third Edition. London/New York: Routledge.

- Pöchhacker, F., and A. Remael. 2019. “New Efforts? A Competence-Oriented Task Analysis of Interlingual Live Subtitling.” Linguistica Antverpiensia, New Series: Themes in Translation Studies 18: 130–143.

- Riccardi, A. 2015. “Shadowing.” In Routledge Encyclopedia of Interpreting Studies, edited by F. Pöchhacker, 371‒373. London/New York: Routledge.

- Romero-Fresco, P. 2011. Subtitling through Speech Recognition: Respeaking. Manchester: St Jerome.

- Rothman, E. N. 2015. “Jeunes de langues.” In Routledge Encyclopedia of Interpreting Studies, edited by F. Pöchhacker, 217‒220. London/New York: : Routledge.

- Seeber, K. G., L. Keller, R. Amos, and S. Hengl. 2019. “Expectations vs. Experience: Attitudes Towards Video Remote Conference Interpreting.” Interpreting 21 (2): 270–304. doi:10.1075/intp.00030.see.

- Seleskovitch, D. 1978. Interpreting for International Conferences. Washington, DC: Pen & Booth.

- Setton, R. 2015. “Fidelity.” In Routledge Encyclopedia of Interpreting Studies, edited by F. Pöchhacker, 161‒163. London/New York: Routledge.

- Shiryaev, A. F. 1979. Sinkhronnyi perevod. Deyatelnost sinkhronnogo perevodchika i metodika prepodavaniya sinkhronnogo perevoda. Moscow: Voenizdat.

- Snell-Hornby, M. 1988. Translation Studies ‒ an Integrated Approach. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Stinson, M. S. 2015. “Speech-to-Text Interpreting.” In Routledge Encyclopedia of Interpreting Studies, edited by F. Pöchhacker, 399‒400. London/New York: Routledge.

- Stone, Christopher. 2015. “Deaf Interpreter.” In Routledge Encyclopedia of Interpreting Studies. edited by F. Pöchhacker, 100. London/New York: Routledge

- Tsuruta, C. 2011. “Broadcast Interpreters in Japan: Bringing News to and from the World.” The Interpreters’ Newsletter 16: 157‒173.

- Xiao, X., X. Chen, and J. L. Palmer. 2015. “Chinese Deaf Viewers’ Comprehension of Sign Language Interpreting on Television: An Experimental Study.” Interpreting 17 (1): 91–117. doi:10.1075/intp.17.1.05xia.