ABSTRACT

Objectives:

This paper synthesises critique from Māori patients with Bipolar Disorder (BD) and their whānau to identify barriers and propose changes to improve the structure and function of the New Zealand mental health system.

Design:

A qualitative Kaupapa Māori Research methodology was used. Twenty-four semi-structured interviews were completed with Māori patients with BD and members of their whānau. Structural, descriptive and pattern coding was completed using an adapted cultural competence framework to organise and analyse the data.

Results:

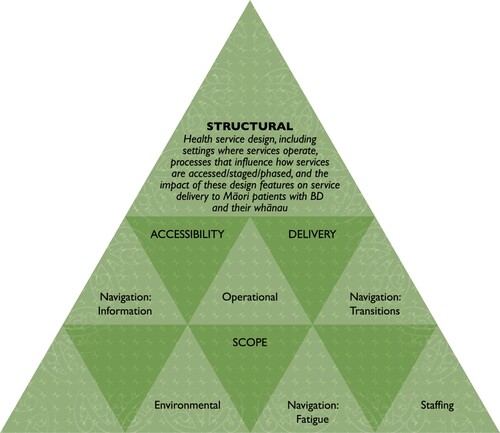

Three key themes identified the impact of structural features of the New Zealand mental health system on health equity for Māori with BD. Themes involved the accessibility, delivery and scope of the current health system, and described how structural features influenced the quality, utility and availability of BD services for Māori patients and whānau. Structural barriers in the existing design, and potential changes to improve the accessibility, delivery and scope of BD services for Māori, were proposed including a redesign of operational, environmental, staffing, and navigation points (information, transition, fatigue) to better meet the needs of Māori with BD.

Conclusion:

A commitment to equity when implementing structural change is needed, including ongoing evaluation and refinement. This paper provides specific recommendations that should be considered in health service redesign to ensure the New Zealand mental health system meets the needs of Māori patients with BD and their whānau.

Introduction

The health system is a social determinant of health (World Health Organization Citation2010). Like other social determinants, health systems contribute to and maintain health inequities that unfairly disadvantage Indigenous peoples. Inequities arise as the health system fails to address differential ‘exposure and vulnerability to health-compromising conditions’ (World Health Organization Citation2010, 5), by advantaging majority ethnic groups who receive better access, experiences and quality of care (Reid, Cormack, and Paine Citation2019). The health system structure includes design features and processes that determine who, when and how care can be accessed, which services are available, where and how they are delivered, and who provides them (Betancourt et al. Citation2003). These structural health system features contribute to differential access to and through care, impacting the quality and efficacy of services available to Indigenous peoples (Betancourt et al. Citation2003; Durie Citation2011; Kirmayer and Jarvis Citation2019; Lopez-Carmen et al. Citation2019; Molloy et al. Citation2018; Newman Citation2009; Reid, Cormack, and Paine Citation2019). Structural changes to the health system have been recognised as one potential strategy to address health inequities caused by the social determinants of health (Betancourt et al. Citation2003; Durie Citation2011; Kirmayer and Jarvis Citation2019; Lopez-Carmen et al. Citation2019; Molloy et al. Citation2018; Newman Citation2009; World Health Organization Citation2010).

There is an established need for international health research designed to increase knowledge and improve outcomes for Indigenous peoples experiencing mental illness (Anderson et al. Citation2016; Kirmayer and Pedersen Citation2014; Kirmayer and Jarvis Citation2019; World Health Organization. Citation2013). Patient-centred research has the potential to increase knowledge about global mental health inequities, by utilising the expertise of Indigenous health service users to provide novel insights about barriers and potential structural solutions to improve mental health care (Braun and Clarke Citation2019; Haitana, Pitama, Cormack, et al. Citation2020; New Zealand Government Citation2018; Palmer et al. Citation2019). Despite this, few studies have positioned Indigenous patients and their families as experts to decolonise and redesign the mental health system in alignment with their expectations and health needs (Haitana, Pitama, Cormack, et al. Citation2020; Palmer et al. Citation2019).

Bipolar Disorder is one of several serious mental health conditions that has a significant impact on a person’s life, and contributes to a high degree of health burden worldwide (Ferrari et al. Citation2016). Research suggests that some Indigenous populations experience higher community prevalence rates of BD, including Māori the Indigenous peoples of New Zealand (Baxter et al. Citation2006; Blanco et al. Citation2017; Grant et al. Citation2005; Waitoki et al. Citation2014). A recent systematic review of BD in Indigenous peoples noted an extremely limited evidence base, recommending Indigenous research designed to identify the impact of systemic factors on current health inequities (Haitana, Pitama, Crowe, et al. Citation2020).

The purpose of this qualitative paper is to identify barriers within the structure of the New Zealand mental health system and propose solutions to achieve health equity for Māori patients with BD and their whānau (family/support networks). A cultural competence framework (Betancourt et al. Citation2003) was adapted as an analytic frame to give voice to participants’ critique and propose structural reforms to healthcare. This is the second of three planned results papers from the qualitative study (Haitana et al. Citation2021).

Methods

Research approach and paradigm

An Indigenous methodology, Kaupapa Māori Research (KMR), informed this qualitative study (Smith Citation2012). The methodology and methods are described in detail elsewhere (Haitana, Pitama, Cormack, et al. Citation2020). Methods chosen aligned with KMR principles, to achieve the study aim and identify how systemic factors influenced equity in health outcomes for Māori patients with BD and their whānau.

The methodology and methods described in this paper form part of a wider project titled the Māori and BD Research Project (MBDRP), which aimed to identify knowledge and prioritise strategies to improve outcomes for Māori with BD. The MBDRP involved three-phases and employed multiple research methods. Phase one involved an epidemiological study of New Zealand mental health service data. Phase two formed the basis for this paper, and involved qualitative interviews. Phase three utilised focus groups with key stakeholders and decision makers involved in delivering mental health services to Māori with BD and their whānau.

Context

The New Zealand health system, while planning reform, is currently structured hierarchically (New Zealand Government Citation2021). This includes: primary care delivered by doctors in General Practice (GPs); community-based services; outpatient and inpatient hospital services delivered regionally by 20 District Health Boards (DHBs); and non-governmental organisations (NGOs). Mental health care for BD generally requires a GP referral to DHB services, and can include periods of inpatient or community-based treatment delivered by multi-disciplinary teams (MDT) within a psychiatric care model. The composition of services and teams can differ between DHBs, meaning experiences of care may change depending on where in New Zealand a person lives (New Zealand Government Citation2018).

Sample

Twenty-four semi-structured interviews were completed across three New Zealand sites selected for their range of mental health services, rural and urban loci. summarises self-reported demographic information for Māori patients with BD (n = 24) who participated. Over half of interviews included the perspectives of patients together with one or more whānau members (n = 19). All patients had a BD diagnosis with a stable mood at interview. Mental health staff gave study information to eligible patients, and interested participants were then recruited by the research team. No exclusions were made for co-morbidities. A purposive sampling frame recruited men and women of differing ages across sites. Participants provided written informed consent before interviews.

Table 1. Participant demographics for Māori patients with BD.

Ethics

Ethical approval was received from the Health and Disability Ethics Committee of New Zealand (ID:16/STH/137). The CONSolIDated critERia for strengthening research involving Indigenous peoples (CONSIDER statement) was utilised to align the study with Indigenous research guidelines and priorities (Haitana, Pitama, Cormack, et al. Citation2020; Huria et al. Citation2019).

Procedure

Interviews were conducted in-person by two of the research team between December 2017 and August 2019. Venues included participants’ homes, health services, or a research unit. The interview schedule was informed by a systematic literature review (Haitana, Pitama, Crowe, et al. Citation2020b), and adaptation of a cultural competence framework (Betancourt et al. Citation2003). Questions explored the impact of structural features of the health system on participants’ hauora (wellbeing), and were framed around questions about current systemic barriers impacting Māori and proposed solutions to these.

Data collection and processing

Interviews were recorded, transcribed and analysed by the research team. Transcripts were anonymised assigning numbers to each interview (1–24), participant (P1-P24) and their whānau (W1-W24). Where multiple whānau were present, an interview number and letter was assigned (W1a, W1b, W1c). NVivo12 data management software was used to display transcripts, code data, and refine codes, categories and themes and monitor saturation across themes and sub-themes.

Data analysis

Two coding cycles were completed (Saldaña Citation2016). Cycle one involved two phases. Phase one used a structural coding method and an adapted cultural competence framework from Betancourt et al. (Citation2003) to group data into participants’ critique of clinical, structural, and/or organisational features of the New Zealand health system.

Betancourt et al. (Citation2003) defined the ‘structural’ component of the health system to include the structure and function of health care systems that influence access, design and delivery of services. Based on the coding process, the criteria for inclusion widened to incorporate the design of health services: including the settings where health services operate from; how health services are accessed/staged/phased; and the systems and processes that impact service delivery and outcomes for Māori patients with BD and their whānau. For this paper, only findings and analysis from the ‘structural’ code drawn from Betancourt et al.’ (Citation2003) adapted analytic frame will be presented.

Phase two used descriptive coding to identify topics within the structural data. Coding cycle two then used pattern coding, where related codes and categories from the first cycle were grouped. Groupings provided breadth and depth to understand the phenomenon being explored forming a theme. This was repeated until theoretical sufficiency was met, measured by the depth of commentary across interviews, and the point at which no further codes, categories or themes were identified.

Coding notes were recorded during both coding cycles to synthesise the detail contained within coded transcripts. Notes were then displayed within a table, reviewed by authors, and reorganised according to whether they reflected problems within the existing structure of the health system, or proposed solutions to these. Coding notes were then reorganised into the themes and related sub-themes identified through pattern coding.

Data display

Findings will be presented by first defining each theme, then presenting the nuances of related sub-themes using quotes to elucidate these. The details of proposed structural changes that would enhance services are then presented within a table format to highlight the breadth of participants’ review of mental health services within each sub-theme. Tables synthesise the analysis, with some proposed structural changes taken directly from interview transcripts and others inferred directly from identified barriers. Language within the tables has been intentionally framed to uphold the mana (prestige) of participants by presenting a strengths-based structural redesign for health services.

Results

Three themes reflected participants’ critique of structural features of the New Zealand health system and their impact on service provision for Māori with BD and their whānau. Themes related to accessibility, delivery, and scope. illustrates these themes and their related sub-themes.

Accessibility

The theme of accessibility included design features of the health system and processes that impact access to and through health services, as well as the accessibility of quality and timely care for Māori patients with BD and their whānau. The theme was further defined by sub-themes involving the degree to which operational, environmental, staffing, and navigation-information influenced accessibility. Nuances of each accessibility sub-theme will now be described.

Operational-accessibility sub-theme

The operational-accessibility sub-theme included participants’ critique of the hours of service operation, including clinic hours, visitation times, and ward rounds; as well as processes for scheduling appointments, and the impact of these processes on access to BD services for Māori.

Appointments are great, but mental illness doesn’t happen between 8.00am and 5.00pm, it happens at any time and often at night. So, being told by emergency on the phone to have a bath is not helpful. (W1)

As a whānau, if you are working with an adult you can’t force them (to access services). You don’t know what options are available. You don’t know what the GP can do versus what the mental health team can do. You don’t know how to access the mental health team. (W2)

I went and talked to a GP and luckily we had free GP access, so they were able to diagnose depression and put me on some medication. (P1)

Her medications cost about $45 a week. If she wasn't under the Mental Health ActFootnote1 she'd have to pay that. (W3)

Environmental-accessibility sub-theme

In the environmental-accessibility sub-theme, participants’ identified environmental features of services that impacted accessibility for Māori patients with BD and their whānau. Environmental-accessibility features included the location, proximity and costs of travelling to and from services.

I was sent to an addiction service. It was on a Tuesday night. I couldn’t really get over to that side of town. (P2)

Table 2. Operational-accessibility sub-theme: barriers and solutions.

It's actually pretty horrible. They let my husband come and sleep with me there at night in a room by each other (he slept on the floor). Otherwise it didn’t feel safe to be honest. (P3)

When she's in the round room, we're not allowed to talk to her. They leave her for long periods of time on her own. They don't even bless the room. (W3)

Staffing-accessibility sub-theme

Participants’ identified that staffing and duty rosters impacted access to effective care. Staffing-accessibility was influenced by: staff roles and ratios, particularly staff specialised in BD care; the diversity of roles in an MDT; the diversity of the health workforce; accepted clinical caseloads; and patient:staff ratios in hospital.

They treat you like a number in there (hospital). The nurses hide from you. Because they have 93 patients and 67 beds. It’s too stretched. (P2)

Table 3. Environmental-accessibility sub-theme: barriers and solutions.

That’s the reality of the support we have from Māori health workers. Otherwise people (staff) don’t even know what we’re talking about. For (Māori patients and whānau), Mātauranga MāoriFootnote2 needs to be in more depth in services to understand the influence of different values and different belief frameworks. (W4)

Some of the worst people (gain employment) in the mental health system and just become part of that system. The ones that are good don't stay, or don't get (their employment) renewed. (W3)

Navigation-information sub-theme

The navigation-information sub-theme involved participants’ critique of multiple access points in BD services, and the lack of support or information designed to assist Māori patients and whānau to navigate to and through care.

It could be easier to see a psychiatrist (about your bipolar disorder). Because if you are out of the system, you can’t actually get back into the system to see one. (P4)

Table 4. Staffing-accessibility sub-theme: barriers and solutions.

It would have been helpful if my school had offered a psychologist’s viewpoint, to understand mental illness. We didn't have any education about that. (P5)

There was no explanation about why I was taking medication, or what my condition was. More information is needed. (P6)

Delivery

The delivery theme included critique about how BD services and interventions are designed and delivered to Māori patients and whānau, and the impact of service designs and delivery on health outcomes. The theme was further defined by sub-themes involving the degree to which operational, environmental, staffing factors, and navigation-transitions influenced the delivery of services to Māori with BD.

Table 5. Navigation-information sub-theme: barriers and solutions.

Nuances of each delivery sub-theme will now be described.

Operational-delivery sub-theme

The operational-delivery sub-theme involved critique of processes, methods and design features that influenced how services were delivered to Māori patients with BD and their whānau, as well as the impact of delivery approaches on health outcomes.

Contact with mental health needs to be empathic and give hope. It is a deficit model, what you can’t do, not what you can do. It is so negative. (P7)

It absolutely needs to move out of that structure. The hierarchy where the psychiatrist is at the top, and over here somewhere is the patient. It needs to flatten out. (P8)

All in all, I was involved with multiple services. It turned into so many relationships breaking down. My Māori health worker was the only consistent person. Services can’t be so separated with one person in between. (P9)

Environmental-delivery sub-theme

The environmental-delivery sub-theme involved participants’ critique of facilities where BD services were delivered to Māori, and whether facilities were equipped to deliver care aligned with Māori health models, values, beliefs and practices.

In hospital you are left sitting with people that are ill. I don’t think that is healthy. You don’t have anything else to do and that’s no good. They (hospitals) make people more ill. (P10)

Table 6. Operational-delivery sub-theme: barriers and solutions.

I don’t know if it is the district, but it is really slack here (at this site). My psychiatrist is trying to get me off the books. Whereas in the other district, I had my psychiatrist for two years and a social worker who saw me every week. I have had none of that here. (P11)

There is a focus (in health services) on the clinical presentation as opposed to how the patient actually feels. From my perspective the system has to change. This fella, he’s a fitness fanatic. So going for a walk up your maungaFootnote3, going on your awa, connecting with the whenua as opposed to only medicating. (W5)

Staffing-delivery sub-theme

In the staffing-delivery sub-theme, processes and procedures that influenced the way staff delivered health care were identified, as well as the impact of staffing factors on the delivery of safe and effective care to Māori patients with BD and their whānau.

They didn't tell me it was bipolar disorder. l stayed in hospital for two weeks on pills then they let me go. They asked questions, that's all. In hospital four staff leaned on my back and shoved me with an injection. That didn't help. I suppose the injection did, but not the way they did it. (P12)

Table 7. Environmental-delivery sub-theme: barriers and solutions.

Some staff were kind. But most of those staff aren’t here now. I liked them because they included a Māori kaupapaFootnote4 and tikanga. But during the years and the changes of the service, they cut that back. I miss it. (P13)

Increasing the Māori mental health workforce would be great. Creating easier pathways to enter that workforce around equity. I understand how important that is, and the competencies required. Not increasing the workforce just because they're Māori, but being able to bring out their innate ability to engage with Māori clientele. (P14)

Navigation-transition sub-theme

The navigation-transition sub-theme critiqued transition points in the hierarchy of the health system, and the impact on whānau Māori of the approach to managing or delivering service transitions for BD.

We got home from school once and our mother wasn't home. There was a note saying the police had taken her away. Another time we (children) were left in the house, and I had to climb to reach the phone and ring someone. Time and time again. (W6)

Table 8. Staffing-delivery sub-theme: barriers and solutions.

I had a breakdown. They took my kids and put me in hospital. Then nobody followed me up. I was back out with nothing and left to my own devices. (P15)

The referral could be done differently. My whānau and I had to wait a month before a psychiatrist called. That’s a long time if you don't know when help is coming. Crisis resolution was much better on my fourth episode than my first. (P5)

Scope

The scope theme included critique about limitations within the design and structure of the health system, the impact of this on service availability, and necessary changes to scope to effectively address the needs of Māori patients with BD and their whānau. The theme was further defined by sub-themes involving the degree to which operational, environmental, staffing factors, and navigation-fatigue were impacted by the existing scope of services. Nuances of each scope sub-theme will now be described.

Table 9. Navigation-transition sub-theme: barriers and solutions.

Operational-scope sub-theme

The operational-scope sub-theme involved critique about processes and design features of the health system that limited the quality or scope of care currently available to Māori patients with BD and their whānau. Participants’ identified limitations in scope through adherence to a biomedical model of health, the impact of separate services, and the silos this created leading to gaps in care.

We tried for years to get them to look at the head injury she sustained. They (mental health services) just didn’t want to know. (W3)

Triggers (to relapse) have been repetitive thoughts, grief, close people passing away. None of the services have picked up on that. (P4)

The amount of suicides in this district is phenomenal. We have to treat people killing themselves seriously. We absolutely need more respite. What is the point of (mental health staff) asking what you want if there is nothing to offer. (P11)

On discharge it would be good for family members to be there so they can hear from doctors. Then I would get a chance to speak on a personal level. A poroakiFootnote5 process would be awesome. (P16)

Environmental-scope sub-theme

The environmental-scope sub-theme included critique about the limitations of operating health care services for BD from fixed locations, particularly when they were long distances from where Māori patients and their whānau lived and worked. Environmental features were also noted to limit the scope of care available particularly in regions that were under resourced due to their rural loci.

There was a different doctor every time I went in. So consistent care is really important, because then you're able to build up relationships with those doctors. Securing funding to have a psychiatrist and making it attractive for that doctor to be here (in this district) is needed. (P14)

Table 10. Operational-scope sub-theme: barriers and solutions.

They drugged me up, told me I would be on medication for life in Australia. Friends came and visited me but whānau didn’t know I was there (in hospital). Because I had no way out to the community or anything. (P17)

Patient safety from other people in the ward is a big issue. I wasn’t the only Māori person with bipolar that was treated badly. I saw a lot really badly treated in seclusion rooms. That (seclusion) happened to me at every admission which is how I know. (P8)

Staffing-scope sub-theme

The staffing scope sub-theme included critique about the absence of key roles designed specifically to address the wellbeing of whānau Māori within the existing structure of BD services. Participants noted that the scope of care for whānau Māori with BD was further limited by narrow role descriptions of existing staff, the high burden placed on the Māori health workforce, and skills shortages and unmet training needs for all staff.

I want to emphasise that I got a diagnosis, but not from a psychiatrist or clinician, I got it from several Māori kaumātuaFootnote6 who came and organised a huiFootnote7 to get me out of hospital. They told me I had an illness from the PākehaFootnote8 world. They looked after me, they were everything to me, and that contrasted with the way I had been treated by the Pākehā system. (P8)

Table 11. Environmental-scope sub-theme: barriers and solutions.

All staff should have the ability to complete education around different diagnoses and things that aren’t directly seen by their service. There definitely needs to be more cross-service education. Because services all have separate priorities with the person stuck in between. (P9)

Prior to entering the mental health system, I got some counselling but that left me feeling very raw, very vulnerable. I mentioned to mental health services that I would really like to see a psychologist but they didn’t offer that service. I can’t afford to go and do the other work I need to do. There’s other people (with bipolar disorder) like that too. (P18)

Navigation-fatigue sub-theme

The navigation-fatigue sub-theme involved participants’ critique of the burden caused by the limited scope of BD service designs and the adverse impact of this on Māori patient and whānau wellbeing.

When he is unwell it puts a real strain on our relationship. I am always the one trying to reach out for help. There needs to be a different approach from professionals. Otherwise it is me forever ringing them (services). (W7)

Table 12. Staffing-scope sub-theme: barriers and solutions.

There is one thing that they should do. They say if he gets unwell to ring the crisis team, but when you ring, they say no you have to contact the police, go there, go here. You’re trying to get the help. It is hōhā.Footnote9 (W5)

From a whānau perspective it would help if someone explained bipolar to us. What it means, how we can help, what services can do, who we can contact, who can help us to help them. We were never involved unless Mum involved us. (Services) never involved us. They should have. (W8)

Discussion

This paper identified three key themes from the expert critique of Māori patients with BD and their whānau regarding the contribution of structural features of the New Zealand mental health system to health equity. Themes involved the accessibility, delivery, and scope of the current health system, and described how structural design features influenced the quality, utility and availability of BD services for Māori patients and their whānau. Participants identified structural barriers in the existing design and potential changes to improve the accessibility, delivery and scope of BD services for Māori in New Zealand. This would involve redesigning the underlying structure to address four common sub-themes related to operational, environmental, staffing, and navigation points (information, transition, fatigue) to better meet the needs of Māori with BD.

Table 13. Navigation-fatigue sub-theme: barriers and solutions.

These findings expand on recent mental health research by detailing structural changes specifically aimed at improving the accessibility, delivery and scope of services for Māori patients with BD and their whānau (Kirmayer and Jarvis Citation2019; New Zealand Government Citation2018; Waitoki et al. Citation2014). The need for structural changes to address the processes that influence accessibility, delivery and scope of mental health care was also consistent with other Kaupapa Māori health research, where adapted frameworks highlighted the impact of systemic factors on differential Māori health outcomes (Dyall Citation2003; Hotu Citation2018; Penney, McCreanor, and Barnes Citation2006). This paper addresses an identified gap within existing mental health research by utilising a KMR methodology that positions Māori patients with BD and whānau as experts in highlighting necessary changes to the design of the mental health system (Haitana, Pitama, Cormack, et al. Citation2020; Haitana, Pitama, Crowe, et al. Citation2020; Palmer et al. Citation2019).

Strengths of this paper include the KMR design in a previously under researched area, and adaptation of a method to privilege the expertise of Māori and identify barriers and potential solutions to improve the structure and design of mental health services for BD in New Zealand. This paper also has limitations. Firstly, recruiting Māori patients and whānau through services may have limited participation to people with positive experiences, however, this did not appear to be reflected in interview data. In addition, if time had allowed, separate interviews with patients and whānau may have highlighted different critique between groups, however, the benefits of one interview were considered and aligned well with KMR principles (Haitana, Pitama, Cormack, et al. Citation2020).

This paper provides a health service user perspective about the impact of structural features of the health system on mental health outcomes and proposes changes to align with the needs of Māori patients with BD and their whānau. While structural changes to the New Zealand health system have been previously recommended, including a medication review framework co-designed with Māori, and targets to reduce rates of seclusion for Māori in inpatient mental health settings, changes have not been consistently implemented (Goodyear-Smith and Ashton Citation2019; Health Quality and Safety Commission New Zealand Citation2021; Hikaka et al. Citation2019; McLeod et al. Citation2017). Transformational change therefore requires a commitment to monitor and address institutional racism driving inequitable access to effective care for Māori with BD and their whānau in our health system (Goodyear-Smith and Ashton Citation2019; Hobbs et al. Citation2019). As New Zealand prepares for significant health system reform, a commitment to equity and implementation of previously recommended structural change is needed, along with ongoing evaluation and refinement of structural changes to ensure their efficacy for whānau Māori (Goodyear-Smith and Ashton Citation2019; Hobbs et al. Citation2019; New Zealand Government Citation2021).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Legislation where mental health patients can be compelled to participate in assessment and treatment.

2 Mātauranga Māori in this context refers to Māori knowledges encapsulating Māori world views, perspectives and cultural practices and their relationship to health and wellbeing.

3 Maunga (mountain), awa (river), and whenua (land) in this context refers to significant tribal landmarks or locations where the patient feels a strong sense of connection. Landmarks also locate a person within their tribal group and alongside their ancestors.

4 In the context of this quote Māori kaupapa and tikanga relates to the inclusion of priorities, activities and customary practices in services that were of value to the Māori patient and enhanced wellbeing.

5 Poroaki (farewell) process in the context of this quote refers to the patient’s desire for staff to facilitate a formal discussion about the period of inpatient care with whānau at the point of discharge.

6 Kaumātua (older person, esteemed person) in the context of this quote refers to Māori community leaders and members of the patient’s extended whānau who were knowledgeable in Matauranga Māori and Māori health.

7 Hui (meeting) in this context involved a meeting arranged by kaumātua with health service officials after visiting the patient in hospital.

8 Pākehā in this context relates to non-Māori/Westernised worldviews and the health system.

9 Hōhā in the context of this quote involves feelings of frustration and exhaustion when trying to navigate service re-engagement.

References

- Anderson, I., B. Robson, M. Connolly, F. Al-Yaman, E. Bjertness, A. King, M. Tynan, et al. 2016. “Indigenous and Tribal Peoples’ Health (The Lancet-Lowitja Institute Global Collaboration): A Population Study.” The Lancet 388 (10040): 131–157. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00345-7.

- Baxter, J., J. Kokaua, J. E. Wells, M. A. McGee, and M. A. Oakley Browne. 2006. “Ethnic Comparisons of the 12 Month Prevalence of Mental Disorders and Treatment Contact in Te Rau Hinengaro: The New Zealand Mental Health Survey.” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 40 (10): 905–913.

- Betancourt, Joseph R., Alexander R. Green, J. Emilio Carrillo, and Owusu Ananeh-Firempong. 2003. “Defining Cultural Competence: A Practical Framework for Addressing Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Health and Health Care.” Public Health Reports 118 (4): 293–302. doi:10.1093/phr/118.4.293.

- Blanco, C., W. M. Compton, T. D. Saha, B. I. Goldstein, W. J. Ruan, B. J. Huang, and B. F. Grant. 2017. “Epidemiology of DSM-5 Bipolar I Disorder: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions – III.” Journal of Psychiatric Research 84: 310–317. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.10.003.

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2019. “Novel Insights into Patients’ Life-Worlds: The Value of Qualitative Research.” The Lancet Psychiatry 6 (9): 720–721.

- Durie, Mason. 2011. “Indigenizing Mental Health Services: New Zealand Experience.” Transcultural Psychiatry 48 (1–2): 24–36. doi:10.1177/1363461510383182.

- Dyall, L. C. T.. 2003. "Kanohi ki te Kanohi: a Māori Face to Gambling." PhD thesis., University of Auckland.

- Ferrari, Alize J, Emily Stockings, Jon-Paul Khoo, Holly E Erskine, Louisa Degenhardt, Theo Vos, and Harvey A Whiteford. 2016. “The Prevalence and Burden of Bipolar Disorder: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013.” Bipolar Disorders 18 (5): 440–450.

- Goodyear-Smith, Felicity, and Toni Ashton. 2019. “New Zealand Health System: Universalism Struggles with Persisting Inequities.” Lancet 394 (10196): 432–442. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(19)31238-3.

- Grant, B. F., F. S. Stinson, D. S. Hasin, D. A. Dawson, S. P. Chou, W. J. Ruan, and B. Huang. 2005. “Prevalence, Correlates, and Comorbidity of Bipolar I Disorder and Axis I and II Disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions.” Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 66 (10): 1205–1215. doi:10.4088/JCP.v66n1001.

- Haitana, Tracy, Suzanne Pitama, Donna Cormack, Mau Te Rangimarie Clark, and Cameron Lacey. 2021. “Culturally Competent, Safe and Equitable Clinical Care for Māori with Bipolar Disorder in New Zealand: The Expert Critique of Māori Patients and Whānau.” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. Advance online publication. doi:10.1177/00048674211031490.

- Haitana, Tracy, Suzanne Pitama, Donna Cormack, Mauterangimarie Clarke, and Cameron Lacey. 2020. “The Transformative Potential of Kaupapa Māori Research and Indigenous Methodologies: Positioning Māori Patient Experiences of Mental Health Services.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 19: 160940692095375. doi:10.1177/1609406920953752.

- Haitana, Tracy, Suzanne Pitama, Marie Crowe, Richard Porter, Roger Mulder, and Cameron Lacey. 2020. “A Systematic Review of Bipolar Disorder in Indigenous Peoples.” New Zealand Journal of Psychology 49 (3): 33–47.

- Health Quality and Safety Commission New Zealand. 2021. “Mental health and addiction quality improvement programme.” Accessed June 9. https://www.hqsc.govt.nz/our-programmes/mental-health-and-addiction-quality-improvement/programme//.

- Hikaka, Joanna, Carmel Hughes, Rhys Jones, Martin J Connolly, and Nataly Martini. 2019. “A Systematic Review of Pharmacist-led Medicines Review Services in New Zealand–is There Equity for Māori Older Adults?” Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy 15 (12): 1383–1394.

- Hobbs, Matthew, Annabel Ahuriri-Driscoll, Lukas Marek, Malcolm Campbell, Melanie Tomintz, and Simon Kingham. 2019. “Reducing Health Inequity for Māori People in New Zealand.” The Lancet 394 (10209): 1613–1614.

- Hotu, Sandra. 2018. “Stop Counting, Do Something! A Person and Whanau Centred Approach for Māori with Chronic Airways Disease.” Paper presented at the New Zealand Respiratory Conference, Auckland, New Zealand, November 22–23.

- Huria, Tania, Suetonia Palmer, C. Suzanne Pitama, Lutz Beckert, Cameron Lacey, Shaun Ewen, and Linda Tuhiwai Smith. 2019. “Consolidated Criteria for Strengthening Reporting of Health Research Involving Indigenous Peoples: The CONSIDER Statement.” BMC Medical Research Methodology 19 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1186/s12874-019-0815-8.

- Kirmayer, Laurence J., and G. Eric Jarvis. 2019. “Culturally Responsive Services as a Path to Equity in Mental Healthcare.” Healthcare Papers 18 (2): 11–23. doi:10.12927/hcpap.2019.25925.

- Kirmayer, L. J., and D. Pedersen. 2014. “Toward a new Architecture for Global Mental Health.” Transcultural Psychiatry 51 (6): 759–776.

- Lopez-Carmen, Victor, Janya McCalman, Tessa Benveniste, Deborah Askew, Geoff Spurling, Erika Langham, and Roxanne Bainbridge. 2019. “Working Together to Improve the Mental Health of Indigenous Children: A Systematic Review.” Children and Youth Services Review 104. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104408.

- McLeod, Melissa, Paula King, James Stanley, Cameron Lacey, and Ruth Cunningham. 2017. “Ethnic Disparities in the use of Seclusion for Adult Psychiatric Inpatients in New Zealand.” New Zealand Medical Journal 130 (1454): 30.

- Molloy, L., R. Lakeman, K. Walker, and D. Lees. 2018. “Lip Service: Public Mental Health Services and the Care of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples.” International Journal of Mental Health Nursing 27 (3): 1118–1126. doi:10.1111/inm.12424.

- Newman, L. A. 2009. “The Health Care System as a Social Determinant of Health: Qualitative Insights from South Australian Maternity Consumers.” Australian Health Review 33 (1): 62–71. doi:10.1071/ah090062.

- New Zealand Government. 2018. He Ara Oranga: Report of the Government Inquiry into Mental Health and Addiction. Wellington, New Zealand. 2021. “Our health and disability system: Building a stronger health and disability system that delivers for all New Zealanders.” https://dpmc.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2021-04/health-reform-white-paper-summary-apr21.

- New Zealand Government, Author First-Name. 2021. Our health and disability system: building a stronger health and disability system that delivers for all New Zealanders. Wellington: Health and Disability Review Transition Unit. https://dpmc.govt.nz/publications/health-reform-white-paper-summary

- Palmer, S. C., H. Gray, T. Huria, C. Lacey, L. Beckert, and S. G. Pitama. 2019. “Reported Māori Consumer Experiences of Health Systems and Programs in Qualitative Research: A Systematic Review with Meta-Synthesis.” International Journal for Equity in Health 18: 163.

- Penney, Liane, Tim McCreanor, and Helen Moewaka Barnes. 2006. New Perspectives on Heart Disease Management in Te Tai Tokerau: Māori and Health Practitioners Talk. Auckland: Te Rōpu Whariki, Massey University.

- Reid, P., D. Cormack, and S. J. Paine. 2019. “Colonial Histories, Racism and Health – the Experience of Māori and Indigenous Peoples.” Public Health, doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2019.03.027.

- Saldaña, Johnny. 2016. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. 3rd ed. Los Angeles: SAGE.

- Smith, Linda Tuhiwai. 2012. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. 2nd ed. London: Zed Books, Decolonising methodologies.

- Waitoki, Waikaremoana, Linda Waimarie Nikora, Parewahaika Erenora Te Korowhiti Harris, and Michelle Patricia Levy. 2014. Māori Experiences of Bipolar Disorder: Pathways to Recovery. Auckland, New Zealand: Te Pou o Te Whakaaro Nui. https://hdl.handle.net/10289/9820.

- World Health Organization. 2010. “A Conceptual Framework for Action on the Social Determinants of Health”.

- World Health Organization. 2013. Comprehensive Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2020. Geneva: World Health Organization.