ABSTRACT

Objectives

Research on dementia literacy in Chinese societies is still emerging, and this is especially the case among racially minoritized groups. The present study explored the knowledge, causal beliefs, and help-seeking behaviors of South Asian migrants in Hong Kong about dementia. It also investigated existing community barriers related to dementia knowledge and help-seeking.

Design

We conducted a qualitative study from a purposive sample of 38 older people and family caregivers from India, Pakistan, and Nepal who lived in Hong Kong. Focus groups and individual in-depth interviews were used to gather information, while thematic analysis was employed to analyze the data.

Results

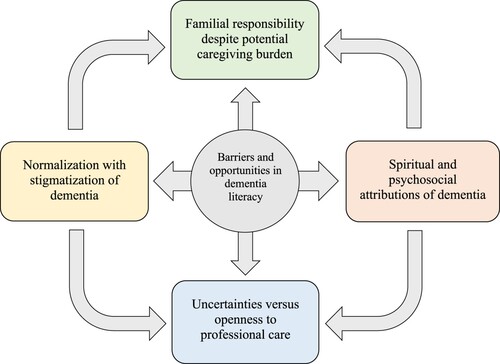

Five main themes were identified: normalization with stigmatization of dementia; spiritual and psychosocial attributions of dementia; familial responsibility despite potential caregiving burden; uncertainties versus openness to professional care; and barriers and opportunities in dementia literacy. Ethnic minorities recognized dementia as a disease of normal aging or a mental disorder. They also perceived spiritual and psychosocial factors as their main causes. While participants recognized the potential burden of dementia caregiving, families were their first point of help-seeking, as many of them expressed contrasting feelings of confidence or doubt toward professional services. Utilization of health education strategies, together with collaboration with community leaders, could address the barriers to dementia literacy.

Conclusions

This is the first study to explore how ethnic minorities in Asia perceive dementia and its related help-seeking behaviors in their communities. South Asian migrants in Hong Kong have a limited understanding of dementia and may experience delays in obtaining relevant community services. While culture influenced their knowledge, health education may address their misperceptions and help-seeking behaviors toward dementia. Culture- and language-specific programs could also improve dementia knowledge and health service access.

Introduction

Dementia is a significant public health concern due to its impacts on patients, families, and communities (WHO Citation2017). The dementia burden is particularly felt in Asia, where population aging is the fastest, and the incidence of cognitive impairment is among the highest globally (ADI Citation2019). In Hong Kong, the dementia prevalence rate for people aged ≥65 years is 7.2%, which is higher than in Mainland China (4.8–7.2%) (Wu et al. Citation2018), Europe (4.6–6.8%), and North America (5.7%) (Prince et al. Citation2015). Given Hong Kong’s increased life expectancy, the number of people with dementia (PwD) is predicted to triple by 2039, along with increased disability (Yu et al. Citation2012). Thus, adequate knowledge is crucial to empower the public in preventing/managing dementia and its related complications. However, misconceptions about dementia remain prevalent among various populations, including racially minoritized groups, older persons, and illiterate people, which could impair efforts in dementia risk reduction, recognition, and management (ADI Citation2019).

Ethnic minorities (EMs) have greater dementia risk due to biological, cultural, and socioeconomic factors (Chen and Zissimopoulos Citation2018). They have higher incidences of cardiovascular conditions, such as metabolic syndrome, diabetes, hypertension, and obesity, which increase the risk of dementia (Noble et al. Citation2017). EMs also tend to experience discrimination and low utilization of medical services, contributing to poorer mental health outcomes (Chin, Negash, and Hamilton Citation2011). In Hong Kong, EM populations have increased by 70% in the past decade (HKCSD Citation2016). Excluding foreign domestic workers from the Philippines and Indonesia, South Asians (mainly from India, Nepal, and Pakistan) comprise the majority (30%) of EMs permanently residing in Hong Kong, with their population increasing from 35,368 in 2006 to 84,875 in 2016 (HKCSD Citation2016). The settlement of these groups in Hong Kong could be traced to their recruitment by the British colonial government for military and police services in the 1900s and through trade over the years (Erni and Leung Citation2014). However, only 10% of South Asians are fluent in Chinese, while only one-third of them have attained post-secondary education (HKCSD Citation2018).

Aside from language and educational disparities, EMs in Hong Kong often encounter challenges in navigating the healthcare system. Vandan et al. (Citation2020a) noted that South Asians perceived lower health system responsiveness than local Chinese people, particularly in patient autonomy, communication, and access to community support. Another study reported that South Asians experienced disengagement from the healthcare system due to inadequate sensitivity of healthcare providers to their religious/cultural beliefs and insufficient provider-patient interaction due to language difficulties (Vandan, Wong, and Fong Citation2019).

Similar to Chinese culture, South Asians subscribe to the collectivist paradigm, highlighting the role of family, social networks, and even communities in health management (Altweck et al. Citation2015). For example, religion influences South Asians’ understanding of illness causation and coping through spirituality (Lucas, Murray, and Kinra Citation2013). Some of them also hold strong beliefs in Ayurvedic medicine, which sometimes lead to decreased compliance to western medical regimens due to fear of toxicity/adverse effects (Kumar et al. Citation2016). With the growing public health burden of dementia in Hong Kong, understanding the perspectives of racially minoritized groups is crucial to ensure that existing community health services are responsive to their diverse needs.

Previous studies reported that dementia prevalence rates varied in South Asian countries, ranging from 1.3% to 10.6% in India (Ravindranath and Sundarakumar Citation2021), 5% to 11.4% in Nepal (Sapkota and Subedi Citation2019), and 2% to 6% in Pakistan (Adamson et al. Citation2020). However, there is limited information on the public awareness of dementia in these countries, although there were studies that observed low dementia knowledge among Nepali college students (Baral, Dahal, and Pradhan Citation2020), Indian medical undergraduates (Patel et al. Citation2021), and Pakistani family caregivers (Zaidi et al. Citation2019).

Despite the vulnerability of EMs to dementia and its consequences, little is known about their knowledge, perceptions, and help-seeking behaviors in Hong Kong. Extant research in Hong Kong has focused on the local Chinese population, indicating they have accepting and proactive attitudes toward dementia, as they prefer to have an early diagnosis for immediate treatment access (Lam et al. Citation2019). Hence, it is crucial to understand the situation among EMs in Hong Kong by exploring their dementia literacy.

Dementia literacy refers to the knowledge and beliefs about dementia that facilitates early recognition, appropriate treatment, and risk reduction (Low and Anstey Citation2009). According to Altweck et al.’s (Citation2015) mental health literacy (MHL) model, people’s cultural backgrounds influence their perceptions of mental illnesses (i.e. schizophrenia, anxiety disorder, depression). However, this model has not been applied to understand dementia literacy among populations, including racially minoritized groups. Meanwhile, evidence shows that enhancing public education about dementia could minimize social discomfort toward PwD (Ebert, Kulibert, and McFadden Citation2020). Improved dementia literacy could also strengthen informal caregivers’ abilities to support PwD (Li et al. Citation2020). Furthermore, promoting dementia literacy in high-risk adults may spur positive behavioral changes to prevent cognitive decline (Anstey et al. Citation2015). Thus, dementia literacy could be a significant health resource for enabling the public to understand and apply relevant information in cognitive health promotion.

Understanding the dementia literacy of EMs can encourage the development of more inclusive mental health services that will address their needs, consistent with the goal of universal health coverage (WHO Citation2019). To date, studies about dementia literacy of EMs are predominant in the US (Chin, Negash, and Hamilton Citation2011), the UK (Mukadam et al. Citation2015), and Australia (Low et al. Citation2010). These studies found that EMs tend to have lesser knowledge of the actual causes of dementia, more negative attitudes, and delayed help-seeking practices compared to the local residents of their host countries. Meanwhile, countries in Asia, Africa, and South America have recorded little to no research on the topic. Consistent with the limited studies on the topic, cosmopolitan regions like Hong Kong have not yet laid down a comprehensive dementia care strategy to provide support services for PwD. A study in Hong Kong revealed that Nepali older adults experienced challenges in accessing health and social services, leading to difficulties in planning for long-term care (Wong et al. Citation2018). EMs in the city commonly rely on their personal experiences and social networks to obtain information about dementia, and often seek assistance from non-government organizations to obtain professional health services (Leung et al. Citation2021). Exploring the dementia literacy of racially minoritized groups may address knowledge gaps for designing appropriate mental health programs for all stakeholders in this Chinese society.

The present study explored the knowledge, causal beliefs, and help-seeking behaviors of South Asian migrants in Hong Kong about dementia. It also investigated existing community barriers related to dementia knowledge and help-seeking. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine how ethnic minorities in Asia understand and perceive dementia in their communities.

Materials and methods

Research design

We conducted a qualitative study from December 2019 to February 2020. Particularly, the descriptive-qualitative approach was used because of the paucity of dementia literacy research among the target group. This method aims to understand people’s insights about certain topics by directly acquiring information from them and examining their attributed meanings (Sandelowski Citation2000). Hence, this enabled a deeper exploration of dementia literacy among Hong Kong’s ethnic minority groups.

Setting and participants

We used a purposive sampling strategy to recruit participants from three EM groups in Hong Kong: Indians, Nepalis, and Pakistanis. The three groups were selected because they represent the predominant EM groups in Hong Kong (HKCSD Citation2016). For a comprehensive picture, older persons and family caregivers were recruited. Inclusion criteria for older people were: aged ≥60 years old; being cognitively intact, assessed using the Rowland Universal Dementia Assessment Scale (RUDAS) score of ≥23 (Storey et al. Citation2004); able to communicate in their local language; and able to travel to the designated interview venue independently. RUDAS was utilized for its good diagnostic accuracy for multicultural samples and decreased influence of language and educational differences (Naqvi et al. Citation2015). Inclusion criteria for caregivers were those aged ≥18 years old and provided daily care (at least 1 h per day) to older family members. For participant safety, we excluded those with fever, influenza symptoms, hospitalized, and living in residential care homes.

Research assistants facilitated telephone contacts to invite prospective participants by collaborating with a non-government organization (NGO) that provides services to racial minorities in Hong Kong. They also conducted paper-based cognitive screening in the older participants. A total of 59 people were invited to the study, but some were unavailable for the scheduled interviews (n = 9), and others showed signs of cognitive impairment (n = 12). To facilitate ease in communication and avoid possible cross-cultural misunderstanding among different ethnic backgrounds, we arranged separate focus group discussions (FGDs) based on ethnicity (i.e. Nepali, Indian, and Pakistani), age (older persons and family caregivers), and gender (male and female).

Data collection

We used FGDs and individual interviews in data collection. FGDs provided a platform for the participants to communicate with each other in a way closer to daily conversations, providing the opportunity to understand the meanings attached to dementia from the specific contexts of racial minorities. Meanwhile, in-depth interviews allowed exploration of responses and specific situations, promoting depth and richness to surface relevant concepts.

The research team developed a semi-structured interview guide (Appendix 1) to explore the participants’ dementia literacy, based on the concepts by Low and Anstey (Citation2009) and Altweck et al. (Citation2015). Thus, data was gathered on participants’ knowledge and beliefs about recognition, risk factors and causes, lay help-seeking, professional service access, and information seeking about dementia. The same interview guide was used for both FGDs and individual interviews, while follow-up questions were used accordingly to expatiate on insights/stories shared by the participants.

Two research team members (AYML and LLP) provided training workshops to research assistants from the racial minority groups to conduct the interviews in the participants’ native languages (Nepali, Hindi, or Urdu) and allow the latter to express their views about the topic freely. All trained facilitators had a college education, previous experiences in facilitating interviews with their community members, and able to communicate in both English and their local dialect. They were not involved in recruitment nor had prior relationships with the participants.

FGDs of 4–6 people were arranged upon agreement with the participants, while separate interviews were conducted for persons unavailable for the group sessions. Apart from pragmatic reasons, these arrangements were made to consider the social distancing measures due to COVID-19 at the latter period of the data collection in February 2020. Before conducting the FGDs/interviews, we collected participants’ demographic information (age, sex, education, etc.). We facilitated the FGDs and in-depth interviews in the private rooms of the collaborating NGO. A research team member (LLP) was present during the data collection, with two local moderators for the FGDs and one facilitator for the interviews. The interview course was flexible, and further questions were asked beyond the prepared semi-structured guide to completely illumine the participants’ knowledge and beliefs about dementia. The FGDs had a duration of 90–120 min, while the individual interviews lasted for 40–50 min. All discussions were audio-recorded after obtaining participants’ permission. Significant verbal and non-verbal data were noted during the interviews. We established the adequacy of sample size through data saturation. Thus, we stopped the interviews upon realizing that participants kept returning to similar topics and the preliminary analysis of the interviews revealed no new findings.

Ethical considerations

We obtained ethical approval for the study from the Human Subjects Ethics Sub-committee of the Hong Kong Polytechnic University (Ref. No.: HSEARS20190902002). Invited persons received detailed study information and signed the written informed consent before participation. Only research team members had access to the study-related documents to ensure participant confidentiality.

Data analysis

The audio-recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim and then translated into English by professional language experts. We employed thematic analysis to inductively analyze the gathered information using the following steps: (1) familiarizing with the data by reading and rereading them, noting for repetitions, analogies, similarities, and differences; (2) generating initial codes; (3) searching for potential themes from the collated codes; (4) reviewing if the themes are well-supported with the coded extracts; (5) defining and naming the individual themes; (6) and relating the themes to the research question and existing literature (Braun and Clarke Citation2006). Finally, we developed a model to illustrate the relationship among the study themes. This method provided a detailed account of the collected data and facilitated combining the analyzes of meanings within the specific contexts. We utilized NVivo 12 software to organize and manage the gathered data.

We facilitated informant checking to establish the credibility of the translated transcripts. Particularly, the English transcripts were back-translated into the ethnic language, and participants were contacted to validate their statements. Moreover, two research team members (LLP and PAA) independently read and analyzed each transcript to identify the significant quotations and codes. Comparison of their individual analyses was done to establish credibility and dependability, with inputs from all authors to build a consensus set of findings. We also identified representative excerpts for readers to identify relationships between the data and results and further consider their transferability to other settings or groups.

Results

A total of 38 individuals participated in the study (). Particularly, seven FGDs (4 Nepalis, 2 Indians, and 1 Pakistani) with 35 participants and three individual interviews (2 Pakistanis and 1 Indian) were conducted. Participants were aged between 31 and 87 years old and had a mean age of 65.4 (SD = 15.4). Majority were females (60.5%) and without formal education (55.3%). The distribution of participants based on ethnicity was: Nepalis (63.2%), Indians (23.7%), and Pakistanis (13.2%). Most of the participants have lived in Hong Kong for less than 10 years (44.7%), with only a few (10.5%) able to speak the local Chinese language. For family caregivers, only one participant had experienced living with a person diagnosed with dementia, while others (41.2%) mentioned caring for family members who showed potential symptoms of dementia (e.g. forgetting things).

Table 1. Participants’ demographic profile (N = 38).

Five themes were culled to describe the ethnic minorities’ evolving beliefs and understanding of dementia: (1) normalization with stigmatization of dementia; (2) spiritual and psychosocial attributions of dementia; (3) familial responsibility despite potential caregiving burden; (4) uncertainties versus openness in seeking professional care; (5) and barriers and opportunities in dementia literacy. Findings showed that while EMs’ knowledge and beliefs about dementia are mainly influenced by cultural practices, these perceptions are continuously shaped by their exposure to various information sources. This is crucial as they navigate from limited understanding and misconceptions of dementia toward utilizing appropriate health information for themselves and other people.

Normalization with stigmatization of dementia

Participants had an inadequate understanding of dementia, and others even noted not hearing such a term or an equivalent in their language. Some participants believed that dementia is an inevitable condition in older adults, identifying it as a disease of age-related forgetfulness. Hence, they considered dementia a less serious health concern than other physical conditions:

Many people have this disease where they forget. It’s a minor problem compared to other diseases … Dementia cannot be prevented since this is part of your age. When people reach 70 years, 50% of them could be affected. (P16, Nepali, carer)

It’s hard to identify if someone has dementia. Everyone looks the same. When people get into old age, they keep forgetting and it becomes repetitive … I also used to feel like this, being indecisive like where to go or what I should do, where to eat the next meal. (P25, Indian, older person [OP])

If someone has this disease that leads to forgetfulness, they are like a lunatic. … some commit suicide by hanging or hurting themselves. It’s like depression. So, we should talk about them going to a hospital … a mental hospital. (P8, Nepali, OP)

You cannot accomplish anything … I think those affected by this disease are like paper; they are lost in their thoughts. They could walk senselessly after becoming crazy or even walk naked. (P3, Nepali, OP)

Sometimes, these people (with dementia) could act like kids. They may suddenly become angry. You can control the child but you can’t control the aged person. So, if you see one, it’s better to avoid them to protect yourself. (P36, Pakistani, OP)

If someone has physical health problems in our community, they will share with others. But if they have a mental illness like dementia, they won’t share it … . People would feel shameful about it … We should keep the patient (with dementia) at home so that others would not see them. (P30, Indian, carer)

Spiritual and psychosocial attributions of dementia

With inadequate knowledge of dementia, participants turned to their cultural precepts to understand its causes. Particularly, they utilized spiritual beliefs to explain that cognitive impairment is a punishment from God/Allah due to previous wrongdoings. Hence, they highlighted that dependence on the Supreme Being could help the PwD. Moreover, they believed that religious leaders should be consulted for guidance in various rituals, such as listening to sermons, reciting spiritual verses, and reading scriptural passages:

According to our religion, God will make us pay for what we sow. Sooner or later, people would need to face the consequences of their actions. (P25, Indian, older person)

Only Allah can help that person (with dementia). Call religious leaders … You may recover from listening to their sermon. Do the morning prayer on time, pray 5 times daily, and recite Quran verses. (P35, Pakistani, carer)

Humans may have different colors, but when we are born, we are formed according to what the naming ceremony has directed to us. Some of us may be born with a handicap. Like this dementia, some may have it even at a later age … it is destiny. (P14, Nepali, OP)

It (dementia) is similar to goats suffering from vertigo. Once water enters the brain of a goat, it will start moving round and round. (P35, Pakistani, older person)

Maybe the person (with dementia) was bewitched. Some people in our community see things this way but not here in Hong Kong … they usually have a medical approach to illnesses. (P3, Nepali, OP)

I think it (dementia) is more common among Pakistanis as we have more concerns related to financial issues and domestic fights … It’s important that we stick together. Sometimes, we have arguments or disagreements in the house; I feel these could be reasons. (P34, Pakistani, carer)

We need to talk to them politely. We should avoid giving them stress. We need to try to engage them in conversations and group activities. I think that’s the main way to help them. (P15, Nepali, carer)

When you are diagnosed with diabetes or hypertension and are aging … I remember the doctor saying that these could be reasons (for dementia), but I’m not sure. Just like we have physical problems with aging, we also have brain health issues. (P30, Indian, carer)

Familial responsibility despite potential caregiving burden

Participants emphasized the family’s central role in dementia help-seeking and management. According to their culture, taking care of older parents is the responsibility of children, wherein personal sacrifices to fulfill such a role is considered acceptable. Notably, their religion indicates that caring for their sick parents could earn them blessings from God. While everyone is supposed to help one another in the family, it is usually the women who are expected to assume the caregiving role:

She (my mother) is lucky even though she is old and her time here may be limited. Even if her husband is engaged with some other work, her children are always there for her. They will leave their job. To serve your parents is like earning a blessing. (P19, Nepali, carer)

It’s the duty of the daughter or daughter-in-law to take care of family members … manage their things, give them medicine, and feed them on time. (P37, Pakistani, carer)

As much as possible, the solution must be brought within the family. We must try first among ourselves if something can be done for the patient … if the disease is severe or not. We need to talk to them, remind them, and try to make them better. (P23, Nepali, carer)

At first, the family should discuss among themselves. But from what I have seen here (in Hong Kong), I do not know where we can get the information (for dementia services). So, maybe we can ask our neighbors if they know something about this … where they went, what they did. They will help to solve your problems. (P11, Nepali, OP)

The main thing is worry. The person (with dementia) is already invalid, but it will be worrisome for others as to where they are, if they are up to something or somewhere, and if they have eaten. It is very stressful. (P30, Indian, carer)

The person (with dementia) is disabled and is sometimes weak. They need assistance for 24 h. It’s complicated because you need to accompany them everywhere they go … This will be a hardship for the entire family. (P36, Pakistani, OP)

Uncertainties versus openness in seeking professional care

The participants appeared to face a difficult choice between professional services and informal care in managing dementia. Due to their cultural beliefs, some participants thought that traditional practices or non-pharmacological approaches might be sufficient to cope with dementia symptoms. However, some also thought that dementia could eventually become unmanageable, requiring help from professional care providers.

In line with their indigenous precepts, some participants noted that witch doctors or folk healers could drive evil spirits to cure dementia. Others considered the use of herbal medicines, believing that pharmacological treatment may be ineffective:

First, we should seek our ancestors, then the shaman (traditional doctors who drive evil spirits). We can also try traditional Ayurvedic medicines. Sometimes, what the doctor cannot treat can be cured by a shaman. (P9, Nepali, OP)

I think they (PwD) can eat almonds. My mother has great memory, as she could remember all her stuff, including her bank accounts. They could also do word search or games. I’m not sure if there is a medical treatment for dementia. (P31, Indian, carer)

We need to observe the patient for a week to 10 days at home to make sure if he/she is suffering from the disease (dementia) or not. Then, we can decide if the patient should be brought to the clinic or hospital. (P16, Nepali, carer)

I think whatever is happening, we should see the doctor only. For those who already have severe memory issues, only the doctor can help them. They should see the doctor straight away to know what should be done. (P30, Indian, carer)

If we had known about some ancient medicine, it would be helpful. But we don't know about it, so the best solution is to send the patient to the hospital. (P24, Nepali, carer)

Medicines don’t work for some people, although others recover well. Even after consulting a doctor and a shaman, if a person is not cured, it is their fate … If God has picked you up to be sick, you can’t do anything. (P37, Pakistani, OP)

Barriers and opportunities in promoting dementia literacy

Participants conveyed contextual and practical barriers to promoting dementia literacy among EMs in Hong Kong. These include inadequate health education programs, language barriers in health education and service access, and financial insufficiency to seek specialized services. Meanwhile, they also suggested potential resources and activities that could be tapped to address these concerns.

According to them, EMs have low awareness of dementia mainly because they do not receive adequate information from health/social care agencies in Hong Kong. Being a minority group, they felt the community might have better informed the local Chinese residents about the topic. Despite some participants suggesting the need for professional help for suspected PwD, they were not adequately knowledgeable about existing community health services. They were also unaware of specific healthcare professionals they should consult with or facilities where PwD might be sent for appropriate management:

There is less information about it (dementia) in Hong Kong. Probably, the Chinese people know more about it than us. I don’t know how common it is here, but our awareness is limited. (P32, Indian, carer)

I don’t know if there is any health organization in Hong Kong for dementia, but I think there should be one. There could be some doctors who provide services, but we do not know about them. (P10, Nepali, older person)

If there is information regarding dementia in schools, the students can help their neighbors or grandparents. Education can be done in religious places, where many people go. (P27, Indian, older person)

Health agencies only call people when they are caregivers or have someone in the house having dementia. Why there are no such meetings for ordinary people? Instead of going into details after the person has the problem, isn’t it better to know something about it before it happens? (P31, Indian, carer).

Mobile phone works. If you put it (dementia education) on YouTube and Facebook, everyone will watch it. These days, even older generations check Facebook. They will spend their entire day using mobile. (P24, Nepali, carer)

Even though there might be information here (in Hong Kong) about dementia, we all don’t know the language, especially those older than us … We have language problems, so it is difficult to talk to the doctor when dealing with sensitive issues like dementia. (P26, Indian, older person)

I have some problems communicating in English or Cantonese, but my husband who has been living in Hong Kong for a very long time would accompany me to the appointments. I have never asked for a translator because they need to be pre-booked … If you don’t, you’ll have to wait longer before the doctor sees you. (P32, Indian, carer)

Due to poverty, some don’t have the means to obtain health services. Our people are poor. Rich people can afford medical treatment. It’s like in Pakistan … people from cities may go (to the doctor), but people from the towns would usually not. (P37, Pakistani, carer)

Is there any help from the government for us and people with dementia? I think we should ask for social assistance from the government to help the affected people in case their families cannot work. (P29, Indian, older person)

I think the hospital wouldn't be of any help, but if we come to a social worker, they would give us suggestions and refer us to someone they know could help. They have the people whom we can relate and talk to. They could prepare the person (with dementia) to send him to places for proper treatment. (P20, Nepali, carer)

Discussion

This study explored the knowledge and perspectives of ethnic minorities in Hong Kong about dementia and its causes; lay and professional help-seeking; and PwD caregiving and management. While participants subscribed to cultural and religious precepts to understand dementia, health information also shaped their knowledge and insights about cognitive decline. Thus, instead of having stereotyped views, ethnic minorities conveyed expanding perceptions of dementia. They also described several factors, such as inadequate health information dissemination, language differences, and financial barriers, which affected how they could understand, manage, and seek help if they encounter dementia within their families.

South Asians in Hong Kong had inadequate understanding and misconceptions about dementia. They normalized it as an age-related forgetfulness or stigmatized it as a psychiatric disorder. Hence, most of them thought it was challenging to distinguish PwD from older people with functional changes and people with mental disabilities. This finding is comparable to a previous study in the UK wherein South Asians often associated dementia with aging, but eventually linked it with mental disorders when serious behavioral symptoms developed (Mukadam et al. Citation2015). Due to the lack of an equivalent term for dementia in their local languages, South Asians could sometimes confuse dementia with other illnesses like schizophrenia or depression (Hossain et al. Citation2020). While negative attitudes toward dementia were also observed in previous studies involving EMs in other countries (Chin, Negash, and Hamilton Citation2011; Low et al. Citation2010), South Asians’ stigma of dementia is further shaped by their religious beliefs. Our current findings revealed that some participants noted dementia as a punishment from God, which could stigmatize families by being perceived as cursed or not religious (Hossain et al. Citation2020). Normalization of dementia influenced the participants to not consider it a health concern requiring urgent attention, while stigmatization of this illness prompted avoidance of obtaining help from other people. Noting dementia as a mental illness, some participants suggested that the patient might instead be admitted to a mental health facility. These misconceptions could contribute to delayed help-seeking and underutilization of appropriate services for PwD.

With the limited knowledge about dementia, cultural beliefs influenced how racial minorities viewed the causes of this condition. They noted evil spells, spiritual retribution, and fate as possible factors leading to dementia. This contrasts with a study in Hong Kong involving Chinese adults who perceived family history and brain injury as top dementia causes (Lam et al. Citation2019). A systematic review also found that South Asians commonly utilized their religious beliefs to explain and cope with chronic illnesses, including diabetes and cardiovascular diseases (Lucas, Murray, and Kinra Citation2013). Compared with most people in Hong Kong, religion is a powerful influence in South Asian culture (e.g. Hinduism, Buddhism, Islam) (Erni and Leung Citation2014). These also influenced their inclinations toward spiritual and traditional approaches to managing dementia. Accepting that dementia is caused by fate or God’s will, some participants believed that seeking medical support might be futile. However, with participants’ perceived knowledge, language, and financial barriers in help-seeking, reliance on these beliefs could further confound their abilities to obtain appropriate and timely interventions for PwD. These findings indicate the importance of developing tailored education programs for EMs to address dementia misconceptions, which could eventually improve their help-seeking practices.

Notably, our study also revealed that some South Asians in Hong Kong have emerging perceptions of dementia as a medical condition. These results contrast with prior studies in the US (Chin, Negash, and Hamilton Citation2011) and Australia (Low et al. Citation2010), which stated that EMs’ knowledge of dementia was limited to spiritual or mythical causes. Having prior contact with healthcare providers, a few participants noted that dementia might be linked with diseases like diabetes or hypertension, although they were uncertain if they understood the information they received. Some participants also expressed awareness that their indigenous beliefs may not be shared by the local population, acknowledging the medical orientation of people in Hong Kong. In a UK study, South Asian participants suggested that reframing dementia as a physical rather than a mental illness could encourage better help-seeking for memory problems among older people (Mukadam et al. Citation2015). Some EM participants perceived that dementia could lead to disabling consequences, stressing the importance of obtaining medical support. However, preference for professional care was sometimes driven by unfamiliarity with possible traditional approaches and not from an understanding of the importance of medical services. These are significant findings that depict the role of health education in enhancing the dementia literacy of racially minoritized people.

The family is crucial in shaping the minority people’s knowledge and beliefs about dementia. For example, participants considered family/group conflicts as causes of dementia, highlighting the role of psychosocial support in its prevention and management. According to Altweck et al. (Citation2015), collectivist beliefs emphasize the importance of social harmony, which could reinforce perceptions that family and even community difficulties or quarrels could cause mental illnesses. South Asians underlined the central role of the family in dementia help-seeking, reflective of the familism concept deeply ingrained in Eastern societies (Galbraith et al. Citation2015). This belief is also prevalent in Chinese culture, following the Confucian thought of filial piety (Liu and Bern-Klug Citation2016). Apart from being a cultural norm, participants noted that supporting PwD is part of the religious obligation among South Asians to care for their sick/older parents (Hossain et al. Citation2020). Hence, they suggested the need for family members to exhaust all possible measures, including assessing illness severity, managing symptoms, and providing the needs of PwD before seeking help beyond the household. Despite sharing similar family concepts with their Chinese counterparts, EMs’ inadequate dementia literacy might hinder effective help-seeking. Our findings revealed that families also contributed to delayed professional support for PwD, with some deciding to seek medical services when symptoms were severe or unmanageable. These behaviors, which are influenced by their cultural assumptions, could lead to poorer health outcomes and reinforce perceptions that nothing can be done to improve the condition of PwD (Mukadam et al. Citation2015).

Although participants acknowledged the role of families in dementia help-seeking and management, they also recognized the potential difficulties in caring for PwD. This finding is noteworthy and highlights the need for early family involvement in dementia literacy programs. This could help address dementia misconceptions, thereby improving illness recognition, attitudes, and help-seeking behaviors (Galbraith et al. Citation2015). Caregiver burden is a prevalent issue in dementia, and equipping families with appropriate knowledge/skills could prepare them to navigate the health system as needed. Meanwhile, participants noted the potential role of younger EM members who received education in Hong Kong in promoting dementia literacy. Since younger EMs are more capable of speaking/writing Chinese (HKCSD Citation2018), they could assist their families in understanding relevant health information. This could promote better information dissemination among racial minorities, who commonly experience language barriers in understanding dementia-related information (Hossain et al. Citation2020).

The study found that being minoritized in another society reinforced the South Asian participants’ collectivist attitudes. Since their own families might not be adequately knowledgeable of available health services for PwD in Hong Kong, participants conveyed that extending help-seeking to their friends and neighbors could allow them to explore better management options. This contrasts with another study among South Asians in Canada (McCleary et al. Citation2012), wherein dementia help-seeking was limited to relatives living or visiting from other countries. In Hong Kong, migrant family sizes are small due to restricted and expensive living spaces (HKCSD Citation2016), making their extended social circles essential in supporting their daily/immediate needs. These results support the need for a more comprehensive approach to educating EMs, as they could contribute to improving dementia help-seeking practices of other community members in the future.

Apart from cultural and religious beliefs, participants acknowledged practical barriers impeding their intentions to seek medical help for dementia. Particularly, most EMs in Hong Kong depends on the public healthcare system, which is usually strained by long waiting lists and turnaround times for services (Vandan et al. Citation2020a). While patients have the option to seek private institutions/providers, the latter have expensive service fees. Notably, South Asians represent half of the poor EM population in Hong Kong (HKCSD Citation2018). This decreased financial capacity, together with the economic burden from medical costs, needs provision, and decreased/lost productivity, serve as barriers to seeking professional services. Currently, the government has a program to financially support low-income families caring for older people (HKSWD Citation2022). Nevertheless, EM participants felt excluded in the public health information campaigns about dementia compared to the local Chinese, making them unaware of existing support/health services for PwD. Although Hong Kong has been implementing the Dementia Friendly Community Campaign to raise public awareness since 2018 (HKSWD Citation2021), its materials and resources are only in Chinese. A more inclusive program that could accommodate the learning needs of EMs (e.g. multilingual programs) is imperative to ensure that dementia friendliness is achieved in the whole region. Accordingly, a non-government organization is beginning to take action to educate EMs about dementia through the Dementia-SMART program (HKCS Citation2021). This program involves older adults, families, and community stakeholders to promote dementia literacy and facilitate early help-seeking among EMs. Government support would be crucial to sustain and expand this program and others alike for more Hong Kong communities.

Participants also expressed that language difficulties complicated their health service utilization. Currently, interpretation services are provided in Hong Kong’s public hospitals and general outpatient clinics, with some health education materials offered in ethnic languages (HKHA Citation2022). However, participants noted the advanced booking requirements and long waiting time associated with this service, making them bring their relatives/friends instead to facilitate communication. Medical interpretation services are also unavailable in other public primary care facilities, including elderly health centers. In a local study, healthcare providers shared concerns about the limited availability and quality of existing interpretation services (Vandan et al. Citation2020b). Hence, government action is imperative for simplified and coordinated language assistance services across public health facilities. Other strategies include mental health literacy training for current interpreters, identifying and hiring EM members for translation services, and preparing health education materials in ethnic languages. In European countries, Verrept (Citation2019) noted that training EMs to assist other migrants and refugees in healthcare facilitated better language interpretation, cultural mediation, and the patient-provider relationship.

Continuing professional education is imperative to prepare health and social care providers to educate EMs about dementia. This could enable them to utilize simple, direct, and focused communication for laypersons to easily understand and apply health information (Regan Citation2014). Participants also highlighted the crucial role of social service organizations in enabling them to access professional health services. Being in close contact with marginalized communities, social workers could serve as vital resources to improve the dementia literacy and help-seeking practices of EMs in Hong Kong. However, a recent study showed that local social workers may not be adequately prepared to provide language- and culturally-appropriate services to non-Chinese communities (Lee, Lai, and Ruan Citation2022). Meanwhile, cultural sensitivity training for local healthcare staff is optional, with most professionals unaware of such programs (Vandan et al. Citation2020b). This significant gap must be addressed through mandatory training across medical/social care professions, including undergraduate courses. Identification and training of eligible EM members as potential staff could also reinforce the capacity of social service agencies to serve Hong Kong’s diverse groups (Lee, Lai, and Ruan Citation2022).

Identifying key people, such as community and religious leaders, with whom health organizations could collaborate to develop programs to enhance EMs’ dementia literacy is vital. Maintaining religious practice is essential for many South Asians in Hong Kong, with mosques and temples serving as places of worship and venues for sociocultural activities (Erni and Leung Citation2014). South Asians also tend to put more value on health information from their peers/elders and religious leaders as they navigate society as a minoritized group (Kumar et al. Citation2016). Education in religious places, through collaboration between health/social care workers and respected leaders, could help address stigma towards dementia, promote better help-seeking, and establish support systems among EMs (Regan Citation2014). Traditional education should also involve local neighborhood leaders and community volunteers, since word-of-mouth is a prominent mode of health information dissemination among South Asians (Kumar et al. Citation2016). Notably, participants also highlighted the value of digital/social media platforms in promoting dementia literacy. Previous pilot studies noted that informative and visually-attractive videos (YouTube) (Woo and Chung Citation2018) and social media pages (Facebook) (Isaacson et al. Citation2018) might be feasible in public information dissemination about dementia. Working with community members in developing such materials could ensure that the key messages are well-communicated and acceptable to the target recipients.

Our study expands the concept of dementia literacy, noting that apart from knowledge, cultural beliefs play crucial roles in the attributions of dementia and help-seeking behaviors (). In this study, participants recognized dementia as a consequence of normal aging yet also perceived it as a stigmatizing mental disorder. Meanwhile, their causal beliefs about dementia were related to spiritual precepts and psychosocial conflicts. These perceptions influenced their help-seeking preferences toward laypersons and professional care providers. While caring for PwD in the family was perceived as a cultural and religious responsibility, participants also communicated concerns about the impending burden of dementia caregiving. Uncertainties in receiving medical care were also expressed due to an inadequate understanding of dementia and subscription to cultural practices. Participants who perceived dementia as a condition not manageable by informal support or were unfamiliar with traditional practices conveyed openness to obtaining professional health services. Altogether, these themes of dementia literacy are driven by existing barriers and opportunities related to information dissemination, language differences, and time and financial resources.

Study limitations and future directions

The study has some limitations. First, the study was limited to South Asian migrants, such as Indians, Nepalis, and Pakistanis. For a broader understanding of the dementia literacy of EMs in Hong Kong, including other groups (e.g. Thais, Japanese, Koreans, Whites, and other Asian groups) would be worthwhile in future studies. Second, only cognitively intact and physically able adults were involved in the interviews, excluding others who may also provide their perspectives on this topic, such as the youth and those with mild cognitive disorders. This was deemed necessary to ensure that the responses were not influenced by problems in cognition while ensuring coherence in data. Nevertheless, future studies could investigate dementia literacy from the lenses of younger people or individuals with cognitive impairment. While this qualitative study has offered an in-depth analysis of the dementia literacy and experiences of racially minoritized groups in Hong Kong, future studies can extend this work by employing quantitative methods to examine the relationships among dementia literacy status, cultural beliefs, and practices relative to dementia and help-seeking behaviors of this population group. The information gathered from these future investigations could guide the development of tailored interventions for promoting dementia literacy among Hong Kong EMs, which could be integrated into existing government programs.

Conclusion

This is the first qualitative study to explore the dementia literacy of racially minoritized groups in Asian regions. Findings revealed that misconceptions about dementia remain prevalent among ethnic minorities, due to their cultural and familial principles about mental health. Despite having a limited understanding of cognitive impairment, ethnic minorities conveyed developing perceptions toward dementia, recognizing the potential role of biomedical attributions and professional health services in its management. These findings reflect the significance of health education and community engagement in enhancing the dementia literacy of ethnic minorities. Collaborative strategies with the local government and minority groups could be instrumental in addressing societal barriers that hinder them from optimizing their dementia literacy, mental help-seeking, and health service access.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (28.7 KB)Acknowledgements

We thank the staff of Hong Kong Christian Service – Support Ethnic Elderly with Dementia Symptoms (Project SEEDS), including Ms. Viola YK Tsang, Ms. Peggy WH Lau, and Ms. Kristy SM Cheung, for their valuable contributions in participant recruitment and providing logistical support in the data collection. We extend our thanks to our research assistants who facilitated the interview sessions and language experts who assisted in the translation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions and containing information that could compromise the privacy of the participants.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adamson, M. M., S. Shakil, T. Sultana, M. A. Hasan, F. Mubarak, S. A. Enam, M. A. Parvaz, and A. Razi. 2020. “Brain Injury and Dementia in Pakistan: Current Perspectives.” Frontiers in Neurology 11: 299. doi:10.3389/fneur.2020.00299.

- ADI (Alzheimer’s Disease International). 2019. World Alzheimer Report 2019: Attitudes to Dementia. London: Alzheimer’s Disease International.

- Altweck, L., T. C. Marshall, N. Ferenczi, and K. Lefringhausen. 2015. “Mental Health Literacy: A Cross-Cultural Approach to Knowledge and Beliefs About Depression, Schizophrenia and Generalized Anxiety Disorder.” Frontiers in Psychology 6: 1272. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01272z.

- Anstey, K. J., A. Bahar-Fuchs, P. Herath, S. Kim, R. Burns, G. W. Rebok, and N. Cherbuin. 2015. “Body Brain Life: A Randomized Controlled Trial of an Online Dementia Risk Reduction Intervention in Middle-Aged Adults at Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease.” Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions 1 (1): 72–80. doi:10.1016/j.trci.2015.04.003.

- Baral, K., M. Dahal, and S. Pradhan. 2020. “Knowledge Regarding Alzheimer’s Disease among College Students of Kathmandu, Nepal.” International Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 2020: 6173217. doi:10.1155/2020/6173217.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Chen, C., and J. M. Zissimopoulos. 2018. “Racial and Ethnic Differences in Trends in Dementia Prevalence and Risk Factors in the United States.” Alzheimer’s and Dementia: Translational Research and Clinical Interventions 4 (10): 510–520. doi:10.1016/j.trci.2018.08.009.

- Chin, A. L., S. Negash, and R. Hamilton. 2011. “Diversity and Disparity in Dementia: The Impact of Ethnoracial Differences in Alzheimer Disease.” Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders 25 (3): 187–195. doi:10.1097/WAD.0b013e318211c6c9.

- Ebert, A. R., D. Kulibert, and S. H. McFadden. 2020. “Effects of Dementia Knowledge and Dementia Fear on Comfort with People Having Dementia: Implications for Dementia-Friendly Communities.” Dementia (Basel, Switzerland) 19 (8): 2542–2554. doi:10.1177/1471301219827708.

- Erni, J. N., and L. Y. M. Leung. 2014. Understanding South Asian Minorities in Hong Kong. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

- Galbraith, B., H. Larkin, A. Moorhouse, and T. Oomen. 2015. “Intergenerational Programs for Persons With Dementia: A Scoping Review.” Journal of Gerontological Social Work 58 (4): 357–378. doi:10.1080/01634372.2015.1008166.

- HKCSD (Hong Kong Census and Statistics Department). 2016. “2016 Population By-census Thematic Report: Ethnic Minorities.” Accessed 3 January, 2022. https://www.statistics.gov.hk/pub/B11201002016XXXXB0100.pdf.

- HKCSD (Hong Kong Census and Statistics Department). 2018. “Hong Kong Poverty Situation Report on Ethnic Minorities.” Accessed 20 June, 2022. https://www.statistics.gov.hk/pub/B9XX0004E2016XXXXE0100.pdf.

- HKCS (Hong Kong Christian Service). 2021. “Dementia SMART - Support to Ethnic Minority Elders Project.” Accessed 20 June, 2022. https://www.hkcs.org/en/services/dsmart.

- HKHA (Hong Kong Hospital Authority). 2022. “Interpretation Service Available in Hospital Authority Hospitals.” Accessed 3 January, 2022. https://www.ha.org.hk/visitor/ha_visitor_text_index.asp?Content_ID = 242254&Lang = ENG&Dimension = 100.

- HKSWD (Hong Kong Social Welfare Department). 2021. “Dementia Friendly Community Campaign.” Accessed 20 June, 2022. https://www.swd.gov.hk/dementiacampaign/en/df_frds.html.

- HKSWD (Hong Kong Social Welfare Department). 2022. “Carer Support Service.” Accessed 20 June, 2022. https://www.swd.gov.hk/en/index/site_pubsvc/page_elderly/sub_csselderly/id_ carersuppo/.

- Hossain, M., J. Crossland, R. Stores, A. Dewey, and Y. Hakak. 2020. “Awareness and Understanding of Dementia in South Asians: A Synthesis of Qualitative Evidence.” Dementia (Basel, Switzerland) 19 (5): 1441–1473. doi:10.1177/1471301218800641.

- Isaacson, R. S., A. Seifan, C. L. Haddox, M. Mureb, A. Rahman, O. Scheyer, K. Hackett, et al. 2018. “Using Social Media to Disseminate Education About Alzheimer’s Prevention & Treatment: A Pilot Study on Alzheimer’s Universe.” Journal of Communication in Healthcare 11 (2): 106–113. doi:10.1080/17538068.2018.1467068.

- Kumar, K., S. Greenfield, K. Raza, P. Gill, and R. Stack. 2016. “Understanding Adherence-Related Beliefs About Medicine Amongst Patients of South Asian Origin with Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease: A Qualitative Synthesis.” BMC Endocrine Disorders 16 (1): 24. doi:10.1186/s12902-016-0103-0.

- Lam, T. P., K. S. Sun, H. Y. Chan, C. S. Lau, K. F. Lam, and R. Sanson-Fisher. 2019. “Perceptions of Chinese Towards Dementia in Hong Kong–Diagnosis, Symptoms and Impacts.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16 (1): 128. doi:10.3390/ijerph16010128.

- Lee, V. W. P., D. W. L. Lai, and Y. X. Ruan. 2022. “Receptivity and Readiness for Cultural Competence Training Amongst the Social Workers in Hong Kong.” The British Journal of Social Work 52 (1): 6–25. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcaa191.

- Leung, A. Y. M., P. A. Amoah, L. L. Parial, and D. Lai. 2021. “Support and Services for Dementia Literacy Experiences and Practices of Ethnic Minorities in Hong Kong.” HLRP: Health Literacy Research & Practice 5 (2): e148–e149. doi:10.3928/24748307-20210503-02.

- Li, Y., L. Hu, X. Mao, Y. Shen, H. Xue, P. Hou, and Y. Liu. 2020. “Health Literacy, Social Support, and Care Ability for Caregivers of Dementia Patients: Structural Equation Modeling.” Geriatric Nursing 41 (5): 600–607. doi:10.1016/j.gerinurse.2020.03.014.

- Liu, J., and M. Bern-Klug. 2016. “I Should be Doing More for my Parent: Chinese Adult Children’s Worry About Performance in Providing Care for Their Oldest-Old Parents.” International Psychogeriatrics 28 (2): 303–315. doi:10.1017/s1041610215001726.

- Low, L. F., and K. J. Anstey. 2009. “Dementia Literacy: Recognition and Beliefs on Dementia of the Australian Public.” Alzheimer’s and Dementia 5 (1): 43–49. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2008.03.011.

- Low, L. F., K. J. Anstey, S. M. Lackersteen, M. Camit, F. Harrison, B. Draper, and H. Brodaty. 2010. “Recognition, Attitudes and Causal Beliefs Regarding Dementia in Italian, Greek and Chinese Australians.” Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders 30 (6): 499–508. doi:10.1159/000321667.

- Lucas, A., E. Murray, and S. Kinra. 2013. “Heath Beliefs of UK South Asians Related to Lifestyle Diseases: A Review of Qualitative Literature.” Journal of Obesity 2013: 827674. doi:10.1155/2013/827674.

- McCleary, L., M. Persaud, S. Hum, N. J. Pimlott, C. A. Cohen, S. Koehn, K. K. Leung, et al. 2012. “Pathways to Dementia Diagnosis among South Asian Canadians.” Dementia (basel, Switzerland) 12 (6): 769–789. doi:10.1177/1471301212444806.

- Mukadam, N., A. Waugh, C. Cooper, and G. Livingston. 2015. “What Would Encourage Help-Seeking for Memory Problems among UK-Based South Asians? A Qualitative Study.” BMJ Open 5 (9): e007990. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007990.

- Naqvi, R. M., S. Haider, G. Tomlinson, and S. Alibhai. 2015. “Cognitive Assessments in Multicultural Populations Using the Rowland Universal Dementia Assessment Scale: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Canadian Medical Association Journal 187 (5): 169–175. doi:10.1503/cmaj.140802.

- Noble, J., N. Schupf, J. Manly, H. Andrews, M. X. Tang, and R. Mayeux. 2017. “Secular Trends in the Incidence of Dementia in a Multi-Ethnic Community.” Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 60 (3): 1065–1075. doi:10.3233/JAD-170300.

- Patel, I., J. Patel, S. V. Jindal, D. Desai, and S. Desai. 2021. “Knowledge, Awareness, and Attitude Towards Dementia Amongst Medical Undergraduate Students: Can A Sensitization Program Help?” Annals of Indian Academy of Neurology 24 (5): 754–758. doi:10.4103/aian.AIAN_874_20.

- Prince, M., A. Wimo, M. Guerchet, G. C. Ali, Y. T. Wu, and M. Prina. 2015. “World Alzheimer Report 2015: The Global Impact of Dementia: An Analysis of Prevalence, Incidence, Cost and Trends.” Accessed 3 January, 2022. https://www.alzint.org/resource/world-alzheimer-report-2015/.

- Ravindranath, V., and J. S. Sundarakumar. 2021. “Changing Demography and the Challenge of Dementia in India.” Nature Reviews Neurology 17: 747–758. doi:10.1038/41582-021-00565-x.

- Regan, J. L. 2014. “Redefining Dementia Care Barriers for Ethnic Minorities: The Religion–Culture Distinction.” Mental Health, Religion & Culture 17 (4): 345–353. doi:10.1080/13674676.2013.805404.

- Sandelowski, M. 2000. “Whatever Happened to Qualitative Description?” Research in Nursing & Health 23: 334–340. doi:10.1002/1098-240x(200008)23:4>334::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-g.

- Sapkota, N., and S. Subedi. 2019. “Dementia as a Public Health Priority.” Journal of Psychiatrists’ Association of Nepal 8 (2): 1–3. doi:10.3126/jpan.v8i2.28016.

- Storey, J. E., J. T. J. Rowland, D. A. Conforti, and H. G. Dickson. 2004. “The Rowland Universal Dementia Assessment Scale (RUDAS): A Multicultural Cognitive Assessment Scale.” International Psychogeriatrics 16 (1): 13–31. doi:10.1017/s1041610204000043.

- Vandan, N., J. Y. H. Wong, and D. Y. T. Fong. 2019. “Accessing Health Care: Experiences of South Asian Ethnic Minority Women in Hong Kong.” Nursing and Health Sciences 21 (1): 93–101. doi:10.1111/nhs.12564.

- Vandan, N., J. Y. H. Wong, W. J. Gong, P. S. F. Yip, and D. Y. T. Fong. 2020a. “Health System Responsiveness in Hong Kong: A Comparison Between South Asian and Chinese Patients’ Experiences.” Public Health 182: 81–87. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2020.01.019.

- Vandan, N., J. Y. H. Wong, J. J. J. Lee, P. S. F. Yip, P. and D, and Y. T. Fong. 2020b. “Challenges of Healthcare Professionals in Providing Care to South Asian Ethnic Minority Patients in Hong Kong: A Qualitative Study.” Health & Social Care in the Community 28 (2): 591–601. doi:10.1111/hsc.12892.

- Verrept, H. 2019. “What are the Roles of Intercultural Mediators in Health Care and What is the Evidence on Their Contributions and Effectiveness in Improving Accessibility and Quality of Care for Refugees and Migrants in the WHO European Region?” WHO Regional Office for Europe. Accessed 20 June, 2022. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/327321.

- WHO (World Health Organization). 2017. “Global Action Plan on the Public Health Response to Dementia 2017–2025.” Accessed 3 January, 2022. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/global-action-plan-on-the-public-health-response-to-dementia-2017—2025.

- WHO (World Health Organization). 2019. “Universal Health Coverage.” Accessed 3 January, 2022. https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/universal-health-coverage-(uhc).

- Wong, P. W. C., C. H. K. Cui, G. Arat, and A. Kot. 2018. “Acculturation and Needs Assessment of Elderly Ethnic Minorities in Hong Kong: A Qualitative Study.” Accessed 20 June 2022. https://www.eoc.org.hk/EOC/Upload/UserFiles/File/Funding%20Programme/policy/1718/HKU_Report_19Nov2018_Finalized.pdf.

- Woo, B. K., and J. O. Chung. 2018. “Improving Dementia Literacy among Chinese Australians Using YouTube.” Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 52 (9): 904. doi:10.1177/0004867418773876.

- Wu, Y. T., G. C. Ali, M. Guerchet, A. M. Prina, K. Y. Chan, M. Prince, and C. Brayne. 2018. “Prevalence of Dementia in Mainland China, Hong Kong and Taiwan: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” International Journal of Epidemiology 47 (3): 709–719. doi:10.1093/ije/dyy007.

- Yu, R., P. H. Chau, S. M. McGhee, W. L. Cheung, K. C. Chan, S. H. Cheung, and J. Woo. 2012. “Trends in Prevalence and Mortality of Dementia in Elderly Hong Kong Population: Projections, Disease Burden, and Implications for Long-Term Care.” International Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 2012: 406852. doi:10.1155/2012/406852.

- Zaidi, A., R. Willis, N. Farina, S. Balouch, H. Jafri, I. Ahmed, Q. Khan, and R. Jaffri. 2019. “Understanding, Beliefs and Treatment of Dementia in Pakistan: Final Report.” http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/82722/.

Appendix 1.

Interview Guiding Questions

Understanding of dementia

Would you share with us any previous experience of hearing the term ‘dementia’?

Can you please describe in your own words what it is?

Where did you learn about this? (i.e. from whom/what sources)

How common do you think dementia is in your community?

Can you think of what a person with dementia may look like?

What services have you heard of that are being provided for dementia?

Beliefs about dementia

If your family member has dementia …

What would be your first response?

What do you expect to happen in the next 1–3 years? 5–10 years?

In your culture, have you come across examples of some possible reasons for dementia?

In your culture, what strategies have you used or have found to be helpful to persons with dementia? How are these strategies offered?

Can you share an experience with us that what doctors/nurses say about dementia is contradictory to what you/your fellows believe?

Intended help-seeking behavior

Would you be able to share with us a previous incident or situation in which you or your family members may show some signs of dementia? (What happened, and what did you or other people do?)

What other people would you get involved with if you want to seek help for dementia?

Can you tell us what has happened when you find health information about dementia? (How does language competence affect your search for information? Where do you seek such information?)

Preferred support services for dementia

Imagine you or your family member has just been diagnosed with dementia, what would you need? (What types of resources or supports do you need? Who could provide these resources or supports?)

What would you do if you want to prevent dementia? How do you know this? (What might help to reduce the risk of developing dementia?)

Which channel/s should be used to provide information about dementia?