ABSTRACT

Background

In the United Kingdom, people with non-white ethnicities are more likely to report being in worse health conditions and have poorer experiences of healthcare services than white counterparts. The voices of those of Black ethnicities are often merged in literature among other non-white ethnicities. This literature review aims to analyse studies that investigate Black participant experiences of primary care in the UK.

Methods

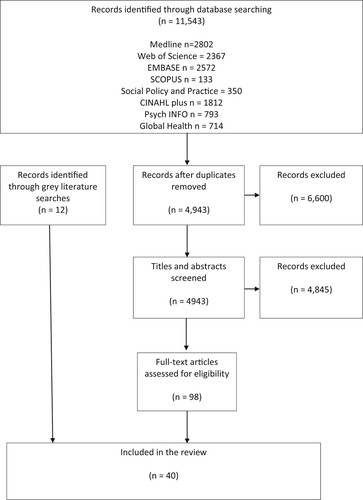

We conducted a systematic literature review searching Medline, Web of Science, EMBASE, SCOPUS, Social Policy and Practice, CINAHL plus, Psych INFO and Global Health with specific search terms for appropriate studies. No publish date limit was applied.

Results

40 papers (39 articles and 1 thesis) were deemed eligible for inclusion in the review. A number of major themes emerged. Patient expectations of healthcare and the health seeking behaviour impacted their interactions with health systems in the UK. Both language and finances emerged as barriers through which some Black participants interacted with primary care services. (Mis)trust of clinicians and the health system was a common theme that often negatively impacted views of UK primary care services. The social context of the primary care service and instances of a cultural disconnect also impacted views of primary care services. Some papers detail patients recognising differential treatment based on ethnicity. The review included the voices of primary care professionals where descriptions of Black patients were overwhelmingly negative.

Conclusion

Views and experiences of Black groups may be radically different to other ethnic minorities and thus, should be teased out of broader umbrella terms like Black and Asian Minority Ethnic (BAME) and Black Minority Ethnic (BME). To address ethnicity-based health inequalities, culturally sensitive interventions that engage with the impacted community including co-designed interventions should be considered while acknowledging the implications of being racialised as Black in the UK.

Introduction

As defined by the World Health Organisation, primary care is ‘first-contact, accessible, continued, comprehensive and coordinated care’ (WHO Citation2021). Primary care settings, including general practice, community pharmacy, dentistry and optometry, serve as the first points of contact for people accessing the UK healthcare system. In the UK, primary care services act as a ‘gateway’ to further medical services with the National Health Service (NHS). 29.6 million GP appointments were made in January 2023 alone (NHS Citation2023). Primary care is free at the point of service.

In the United Kingdom, people of ethnic minorities are more likely to report being in worse health in comparison to white British groups and have poorer experiences of using health services when compared to white British people (The King’s Fund Citation2021). Health inequalities are systematic, avoidable and unfair differences in health outcomes that can be seen between populations (McCartney et al. Citation2019). Health inequalities are not a recent phenomenon, but COVID-19 has brought these health inequalities to the fore, as the pandemic has further entrenched inequalities (Bambra et al. Citation2020) in health outcomes between different ethnic groups (Razieh et al. Citation2021).

Language to describe African origin populations is often not precise enough to fully describe the group of interest (Agyemang, Bhopal, and Bruijnzeels Citation2005). This paper refers to African origin populations as people of ‘Black ethnicities’, encompassing ideas of both race and ethnicity. People of Black ethnicities were most likely to be diagnosed with the COVID-19 and people from Black and Asian ethnic groups were most likely to die (Public Health England, Disparities in the risk and outcomes of COVID-19 Citation2020). In England and Wales, people from ethnic minority backgrounds made up 34.5% of those who were critically ill while only being 14% of the population (Intensive Care National Audit and Research Centre). COVID-19 vaccination uptake remains lower among ethnic minority groups in the UK particularly among Black groups compared with white groups (Gaughan et al. Citation2022).

In the UK, the specific narratives of people with Black ethnicities in literature reviews is often mixed within wider groupings of other communities (Khan Citation2021; Delanerolle et al. Citation2021; Robertson et al. Citation2019). However, this is problematic. It suggests that BAME is a homogenous group and does not give room for the needs and experiences of different groups to be discussed effectively. The initial months of the pandemic brought into sharp relief the reality that people of Black ethnicities specifically made up a disproportionate number of those who became infected with the virus, developed a severe illness and died (Office of National Statistics Citation2020). This indicated a healthcare system that was not meeting the needs of a population. This paper details a systematic review that considers the views and experiences of primary care among people of Black ethnicities in the United Kingdom. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first review to systematically search and record people with Black ethnicities’ views and experiences of primary care in the United Kingdom.

Search methods

Types of studies

This systematic review focuses on papers that make use of qualitative methodology, where authors discuss their findings narratively without primary focus on numerical data or statistics. In this review, included papers make use of interviews, focus groups and questionnaires with free text responses to document participant views and experiences of primary care. The search also targeted papers that make use of qualitative methods of analysis specifically thematic analysis, framework analysis, content analysis, interpretative phenomenological analysis and grounded theory. Papers that utilised quantitative methods of data collection and analysis were excluded. Non-English were also excluded.

Types of participants

This review includes papers that focused on people with Black ethnicities’ views and experiences of primary care in the UK. The search was designed to simultaneously capture participants of mixed ethnicities, where part of their heritage is of a Black ethnicity. The review included terms that captured Black people living in the UK including ‘BAME’, ‘BME’ and ‘ethnic minority’. Names of African countries with large migrant resident presences in the UK were also included such as Nigeria, Ethiopia and Somalia and the Caribbean. Articles were included in the review if there was a sufficient ethnicity breakdown to determine when comments and quotes came from people of Black ethnicities, in papers where there were participants of multiple ethnicities.

The search included papers where Black participants reported their experiences of accessing general practice, pharmacy, dentistry and optometry. This included if they were accessing it with or on behalf of their children. A comprehensive search strategy was developed using key terms to describe primary care services such as ‘vaccination’, ‘screening’, ‘maternity’, and ‘dental care’. The review also included papers where primary care professionals of any ethnicity shared their views about Black experiences in navigating primary care. The review focuses on the UK alone as there is one comprehensive healthcare system, and Black experiences around the world carry specific nuances that should be addressed separately. Research done outside of the UK was excluded.

Database searches

The electronic database search for eligible studies was made across the following databases: MEDLINE, Web of Science, Embase, Scopus, Social Policy & Practice, CINAHL Plus, Psych Info and Global Health. Grey literature was also searched using the Dissertations and Theses Global platform and Open Grey. There were no date limits set to capture as many papers as possible ().

Screening, quality assessment and data extraction

In total, 11,543 records were returned by the database searches. The papers were run through a de-duplication algorithm which returned 4943 papers. Titles and abstracts of all papers were screened in duplicate by the author (OOA) and a second reviewer (AS), using the screening platform Rayyan. Disputes were resolved by discussion. 98 articles were read in full, in duplicate and it was determined that 40 articles were suitable for the review. 20 papers focused on participants with Black ethnicities exclusively and 17 included individuals with Black ethnicities alongside participants with non-Black ethnicities ().

Table 1. Data extraction for papers that had Black patient participants.

Three papers detail the perspective of primary care professionals reflecting on the experiences of Black patients ().

Table 2. Data Extraction for papers with primary care professionals of any ethnicity.

Each paper did include Black participants, but not all papers recorded ethnicity in the same way. Many papers referred to Black African, Black Caribbean or Black British groups. Some papers were more granular and recorded country of origin which included Congo, Sudan, Somalia, South Africa, Zimbabwe, Zambia and Ghana. The papers included a variety of primary care services including maternity, GP, mental health, immunisation, screening and end of life care services ().

Table 3. Number of papers referring to primary care services with Black patient participants.

Reviewers did not exclude papers based on quality, so as to capture and critically analyse as many papers as possible. To critically assess the quality of included papers, the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP Citation2013) was used. Quality appraisal was conducted by OOA. Quality of included papers was mixed. Most papers included a clear statement of aims and findings and the various qualitative approaches were considered appropriate. However, around 50% of the papers were deemed not to have adequately considered the relationship between the researcher(s) and participants ().

Table 4. Summary of CASP qualitative quality assessment.

To extract data for analysis, participant quotations and author commentary were lifted and coded by one researcher (OOA) and this was checked by a second researcher (SMJ). A thematic analysis was manually conducted by detecting patterns in papers and assigning the data codes. These codes were arranged as headings in MS Word and relevant data was collected under these headings. These codes were arranged into seven themes. OOA populated the data extraction table which was checked by a second researcher (SMJ).

Results

Expectations of healthcare and health seeking journeys

Expectations of healthcare services

The differences between healthcare systems in the countries of origin of some Black migrant communities and the primary care system in the UK, impacted on whether and how they interacted with the health system. These expectations around healthcare delivery directly informed people’s behaviour towards primary care. ‘Back home we only have hospitals. Whereas here you have primary care, specialists and whatever’ (Somali woman participant in Davies & Bath, Citation2001). Patients were particularly vocal about their expectations for maternity care and cervical screening due to heightened sensitivity around intimate examinations. These interactions required delicacy and the literature reports that this was not always the experience of patients - ‘They’re not sympathetic because it’s a job that the nurses do all the time, every day of the week, it felt like it was a conveyor belt … ’ (Participant in Bache et al. Citation2012; Abdullahi et al. Citation2009). The theme of being ‘sent away with paracetamol’ and not being taken seriously by primary care professionals was also evident (Lindenmeyer et al. Citation2016). Among those who had survived cancer treatment in hospital, the role of the GP was not clear and there was confusion about which clinician to go to after being in hospital - ‘you’ve got to make your own conclusion what the GP is all about’ (PS Participant in Margariti et al. Citation2019).

Attending primary care to access preventative services like screening and general health checks emerged as an unfamiliar area for several patients (Abdullahi et al. Citation2009; Alidu and Grunfeld Citation2020). The system itself has specific expectations of its users which causes confusion particularly regarding vaccination schedules and issues around receiving the same vaccine twice. This was highlighted by Somali participants who had also lived in Holland and Kenya (Condon Citation2002), and were juggling multiple expectations of various health systems. Differences between systems meant that patients found the UK health system a difficult system to navigate. At times, this led to participants feeling like a burden to professionals and to the UK as a host country (Brewin et al. Citation2006; Edge Citation2011; Jomeen and Redshaw Citation2013).

| b. | Health beliefs and behaviours | ||||

Beliefs about health, the body and medicine influenced health behaviours. Many participants recognised God as part of the health landscape and at times, conditions were deemed to be ‘God’s will’ (Abdullahi et al. Citation2009) and ‘everything happens because of God’ (Binder et al. Citation2012). Spiritual explanations featured very heavily in explanations around mental health (Islam, Rabiee, and Singh Citation2015; Kolvenbach et al. Citation2018; Loewenthal et al. Citation2012). Religious and spiritual explanations for ailments were common, as well as the same medium through which relief was sought- ‘There [is] a lot of lack of medical culture. In European countries they don't know about djin and evil eye, they don't know they need to recite the Koran’. (Rabiee and Smith Citation2007). Another health-seeking strategy was to get access to what biomedical health professionals offered in their country of origin, in the UK - ‘When we come from abroad, we would be used to antibiotics … ’ (Zimbabwean woman, Lindenmeyer participant 2016). When patients did make it to primary care, some reported wanting familial support in addition to formal primary care services. At times, this caused friction between the patient, their family and the primary care professionals - ‘I’ve got a large extended family who all wanted to visit [my mother]. The nursing staff used to get ‘stroppy’ and throw them out’ (Koffman and Higginson Citation2001; Jomeen and Redshaw Citation2013; Giuntoli and Cattan Citation2012).

Health seeking strategies reciprocally inform health decision making. Only after practices like prayer and fasting to address symptoms did some people seek biomedical attention, when they deemed their symptoms ‘serious’. This resulted in a self-negotiation where people considered if their condition was eligible to be treated in primary care - ‘I will not go to the GP if it’s a cold or a cough’ (Alidu and Grunfeld Citation2020). A participant commented that they had never been to a doctor while living in Jamaica and Higginbottom notes that ‘participants view resourcefulness and self-care, as an essential component of life in the Caribbean’ (Higginbottom Citation2006). Feeling autonomous was very important to participants who accessed primary care where patients wanted advice that was sufficient for them to use to make their own decisions - ‘It’s not like you are asking them to make a choice for you but you are asking their professional view’ (Ahmed et al. Citation2014). A patriarchal family dynamic emerges as a barrier to the HPV vaccination for a girl as her mother felt unable to vaccinate her daughter - ‘If it was up to me I would consent, but I am not the head of the family. Her father said no’ (Marita participant in Mupandawana & Cross, Citation2016).

Language

Language was a barrier to information for Somali participants in written and spoken form. Participants addressed this through arranging for interpreters. Using an interpreter eased communications, as information could be more accurately shared - ‘it’s like talking to your brother or sister’ (Binder et al. Citation2012). However, adding a formal (hired through the primary care service) or informal (arranged by the patient such as a friend or family member) interpreter to the consultation, brought an added fear of being a burden to the interpreter and fear of gossip within the community (Bulman and McCourt Citation2002; Davies and Bath Citation2001; Loewenthal et al. Citation2012). In some cases, working with an interpreter precluded patients from disclosing certain information (Davies and Bath Citation2001).

Finances

At times, there was a belief that there was a cost for medical care, even if there was no such cost. The financial implication of taking time off work and/or seeking childcare for young children emerged as a theme (Margariti et al. Citation2019; Thomas, Aggleton, and Anderson Citation2010; Alidu and Grunfeld Citation2020; Abdullahi et al. Citation2009; Edge and MacKian Citation2010). Desperate to circumvent this perceived financial barrier, some patients reported scenarios where they used the identity of another patient with ‘legal status’ in order to be seen, even though legal guidelines at the time said treatment deemed immediately necessary should be given regardless of legal status (Thomas, Aggleton, and Anderson Citation2010). The financial barrier to dental care stopped patients from accessing care - ‘I can’t afford to go to the dentist, it’s too expensive’ (Newton et al. Citation2001).

(Mis)trust

Instances of poor treatment directly to an individual or someone known to them meant patients expressed they would be less likely to engage with primary care in future. ‘That is probably why a lot of Black women don't bother going to the system … the majority have have had nightmares’ (Edge participant, Citation2011). Mistrust was noted between the patient and the healthcare professional, as well as mistrust of an overall ‘system’. Where trust was sought and found was among Black psychological therapists who patients felt ‘would be more likely to understand and empathise with their lived experiences’ (Edge and MacKian Citation2010) although the theme of trust did not always imply a common ethnicity (Giuntoli and Cattan Citation2012; Binder et al. Citation2012). The literature reports mistrust due to ethnicity - ‘Some of the African Caribbean community … take a very rational view that mental health services are punitive, they’re sectioning a lot of them … ’ (COM4; Islam, Rabiee, and Singh Citation2015) evidence that patients are already embody the knowledge of their likelihood for harsher treatments before they even enter the mental health system. Despite this, when mental health services are sought by Black participants, one paper describes primary care itself as a barrier to receiving care as a GP is recorded as dismissing a participant saying ‘you’re not depressed … you’re doing too much … you’re not depressed’ (Edge and MacKian Citation2010). Additionally, historic racial injustices framed patients’ experience of care. Marlow et al, report of a Caribbean woman who described how she felt being examined by a white male GP - ‘ … a strange white man … you always remembering your history about all the horrible things that were done to … Black females in those days’ (Black Caribbean woman participant in Marlow et al. Citation2014). With HPV vaccinations, mistrust is linked to a perceived lack of information and medical research - ‘[l]et [white people] vaccinate their own children first’ (South African mother particpiant in Mupandawana & Cross, Citation2016). In the case of vaccinating their children, some parents believed it was in the best interest of the child, whilst holding the simultaneous belief that health professionals would receive ‘brownie points’ if they vaccinated more children (Condon Citation2002).

Social context of primary care service

Primary care service interactions occur within social contexts for patients. Patients described various reasons as to why they felt unable to develop a social relationship with the professionals looking after them. In GP and maternity appointments, patients disliked that the clinician changed between appointments, causing them to raise concerns around continuity of care ‘You can’t get to see who you want’ (Margariti et al. Citation2019; Edge Citation2011). Patients also felt dismissed and rushed by healthcare professionals (Koffman and Higginson Citation2001; Jomeen and Redshaw Citation2013), and unable to develop a consistent relationship with the nurse or GP (Marlow et al. Citation2014). Poor quality of care was reported across maternity services where women described being physically handled roughly and feeling invisible (Edge Citation2011; Jomeen and Redshaw Citation2013), GP services were participants describe racist and uncaring staff (Rabiee and Smith Citation2007; Nanton and Dale Citation2011), home care where staff showed no consideration for patient privacy (Koffman and Higginson Citation2001) and dental care where procedures led to excessive pain and blood (Newton et al. Citation2001).

The symbolism of vaccinations was a focus for participants. In comparison to other primary care services, patients and parents are recorded more often seeking information about vaccinations and this having a large impact on their views towards the immunisation. With the HPV vaccination, patients and parents expressed concerns about the age it was administered and the level of medical research (Marlow et al. Citation2009; Mupandawana and Cross Citation2016; Forster et al. Citation2015). The social link of receiving the vaccine and subsequently engaging in sexual promiscuity was a large concern - ‘She might see it as a green card to have sex’ (Patrick participant in Mupandawana & Cross Citation2016).

Cultural disconnect

Circumcised Somali women (victims of female genital mutilation) were concerned about the presentation of their bodies and they felt they would be judged by British healthcare staff - ‘There are many reasons you would avoid [maternity services], it’s so embarrassing’ (Abdullahi et al. Citation2009; Chinouya and Madziva Citation2019). Patients also reported feeling pressured into unnecessary caesarean section procedures because of health professionals were not familiar with circumcised women delivering babies naturally (Straus et al. Citation2009). Another paper explores why African women attended their 13-week pregnancy check-up late, and pointed towards cultural taboos about announcing a pregnancy before this time (Chinouya and Madziva Citation2019). Another cultural disconnect for Somali participants was in the fact that information is traditionally passed orally in their community and as such they are unlikely to respond well to written information (Abdullahi et al. Citation2009). Relatedly, other patients reported that it was difficult to find a leaflet that showed a meningitis rash on Black skin (Condon Citation2002).

There were also issues of cultural sensitivity in the context of mental health services. The literature reports stigma surrounding mental health issues in Black communities where they feared social ostracisation because of the diagnosis often tied to a belief that there is a spiritual cause - ‘We would actually prefer our child to have a physical problem than a mental health problem, because it is like a mark on you for life’ (Kolvenbach et al. Citation2018).

Treated differently because of ethnicity

Repeatedly, patients reported that they were treated unfairly because of their ethnicities across mental health services and maternity care. ‘If there’s a mental health patient who is big, a big black man, six foot two, somehow they are afraid of him more than a six-foot, seven-foot, white man’ (Mclean, Campbell, and Cornish Citation2003). Racist stereotyping defined participants’ experience of mental health services where participants felt the treatment they received (or did not receive) was based on the fact that they were Black - ‘they really don’t believe that Black people can be treated, that Black people can be given therapy, that you can talk to Black people’ (Mclean, Campbell, and Cornish Citation2003; O'Donnell et al. Citation2007; Shangase and Egbe Citation2015; Margariti et al. Citation2019; Phillips Citation2014). Similarly, Davies and Bath note that Somali maternity patients believed they received less attention from healthcare professionals because they were seen to be ‘difficult patients’ (Citation2001).

Primary care professionals’ voices

The literature search also included articles where participants were healthcare professionals describing their interactions with Black patients and expressing what they thought the views and experiences of Black patients were. Edge reports of a GP who was challenged about why she rarely diagnosed Black women with postnatal depression even though she knew she had such patients - ‘Possibly we're missing them [nervous laughter], I don't know, but they don't kill themselves. So, even if we're missing them, we are managing them’ (Edge participant Citation2010). Generally, primary care professionals recognised the notion of stigma surrounding mental health in some Black communities (Wagstaff, Graham, and Salkeld Citation2018) as well as the lack of Black healthcare workers who can offer cultural insight (Edge Citation2010). Health professionals determined that ‘UK-born women are not as submissive as migrant women and were more empowered and autonomous in decision-making’ describing them as ‘loud and aggressive’, saying that ‘the West Indian girls are very in your face (Puthussery et al. participants Citation2008).

There were sections of few papers where patients reported positive experiences of primary care where they felt well looked after, were comfortable with their GP surgery and felt well supported (Binder et al. Citation2012; Abdullahi et al. Citation2009; Jomeen and Redshaw Citation2013).

Discussion

Literature on Black experiences of medical services is mainly US-based, set in a heavy historical and contemporary context of racial oppression, segregation, and injustice. In line with this UK-based review, US literature overwhelmingly reports negative views and experiences of healthcare and medical research as experienced by African-American communities (Abrums Citation2004; Freimuth et al. Citation2001). Until now, UK studies have considered specific health conditions such as sickle cell in Black ethnic groups (Thomas and Taylor Citation2002) (Bennett et al. Citation2015) and many more have considered health conditions and health priorities within the ‘BAME’ community (Iqbal et al. Citation2021; Sass et al. Citation2009; Garcia et al. Citation2015). However, this review considers all aspects of primary care, and encompasses all Black ethnicities excluding other ethnic minority groups. The literature demonstrates that primary care services are not devoid of the impact of racism and prejudice in the UK and this reality frames the primary care interactions themselves.

An individual’s propensity to access primary care is influenced by their pre-existing health seeking behaviours inside and outside of the UK, as well as features of the primary care system (Cornally and McCarthy Citation2011; Norman and Conner Citation1996). A pluralistic approach to health that extends beyond biomedicine, may mean that primary care may not be the first port of call for members of these ethnic groups (Higginbottom Citation2006). Research should also consider the impact of language in registering with a GP, arranging appointments and understanding the differences between primary and secondary care. Mistrust of clinicians and of the medical system are embodied in primary care interactions. There is a sociality embedded within primary care, and if this is unaccounted for in interactions, patients record poor experiences. Negative experiences of maternity care, mental health services and GP consultations were tied to expectations of the service and a poor experience. The apprehension surrounding immunisation was not usually about the physicality of receiving a vaccination, but were about a social implication. The vaccination symbolised something socially such as trust in an authority, or approval towards promiscuity in the case of HPV vaccination. Cultural disconnects led to women who had been circumcised feeling that they were treated differently because of an anatomical difference, which could have been handled routinely in their home country. Cultural disconnects also highlighted incongruous understandings of health and the body. Stigma and shame stopped people from seeking help to assist with mental health and defined their experiences when they did interact with mental health services. The literature records instances where healthcare workers knowingly treated Black people differently. There is evidence that health care professionals have some knowledge about social stigma around mental health and the reasons for delayed presentation.

The way we talk about ethnicity is dynamic and changeable, and this impacts on the review findings. The authors generally did not include a definition as to who is considered Black, other than in some instances noting where participants say they are from as a means of recording their country of origin. In most cases, information as to whether the ethnicity is self-reported or assumed by the researcher is also not included. In the UK census, overseen by the Office of National Statistics (ONS), Black is an ethnic category, with Black-African, Black-Caribbean and any other Black background as subgroups. In some papers, Black Caribbean or Black African, is used interchangeably with Black, whilst in others the subgroup is specified. The majority of the records did not include any discussion or footnote elucidating whether the participants had self-identified as having a Black ethnicity or how the category in their paper was defined. Most of the data also did not consider the number of years the participants had lived in the UK, or whether they were second or third-generation migrants. These experiences are nuanced, to which researchers should be sensitive. There is not, nor was the review initiated to find a monolithic ‘Black experience’. However, there is a commonality of being ‘read’ as Black in the UK and this permeates all aspects of society, including primary healthcare provision.

Limitations

This review has a number of limitations. The database searches returned articles where Black participants were included among other ethnicities, however, the paper did not offer enough granularity to ascertain when comments were made about or Black people. As such, some papers that did report on Black people’s views and perceptions were excluded. 51% of eligible papers in the review included data about Black participants amongst other ethnicities, and thus, in half of the papers exclusive focus was not given to those of Black ethnicities. If these papers were excluded, only 20 papers would have been eligible for the review highlighting the need for more qualitative research documenting Black experiences. Some experiences may not be tied to ethnicity and have been reported by people of various ethnicities such as feeling dismissed and concerns about quality of care. Although the review provides an insight into Black experiences alone there are other socio-economic factors that impact on individuals’ experiences that should also be taken into consideration. The review was also impacted by the mixed quality of the studies where 48% of included papers were not sufficiently reflexive failing to rigorously consider the relationship between the researcher and participants.

Statement on positionality

Like the reader, the authors are impacted by their own social, political and historical contexts. OOA (primary author) identifies as a second-generation Nigerian migrant living in the UK, who uses the Black African ONS category to self-identify. The subject of the review is of personal and scholarly interest to the authors.

Conclusion

The literature shows a negative picture of primary care experiences for Black people in the UK. This has large implications for discussions about health inequalities, as communities’ views and experiences of primary care will inform whether and how they engage with the healthcare system in future. This provides an evidence base to begin more research in the area, and the COVID-19 pandemic has shone a light on deep roots of health inequalities in the UK. There is a need for primary care professionals to be culturally sensitive and to champion the decolonisation of medical training. This will improve awareness of their own biases and will result in better health outcomes for minoritised groups. Interventions to improve experiences should be co-designed with the communities they are designed to help.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abdullahi, A., J. Copping, A. Kessel, M. Luck, and C. Bonell. 2009. “Cervical Screening: Perceptions and Barriers to Uptake among Somali Women in Camden.” Public Health 123 (10): 680–685. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2009.09.011

- Abrums, M. 2004. “Faith and Feminism: How African American Women from a Storefront Church Resist Oppression in Healthcare.” Advances in Nursing Science 27 (3): 187–201. doi:10.1097/00012272-200407000-00004

- Agyemang, C., R. Bhopal, and M. Bruijnzeels. 2005. “Negro, Black, Black African, African Caribbean, African American or What? Labelling African Origin Populations in the Health Arena in the 21st Century.” Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 59 (12): 1014–1018.

- Ahmed, S., L. D. Bryant, Z. Tizro, and D. Shickle. 2014. “Is Advice Incompatible with Autonomous Informed Choice? Women’s Perceptions of Advice in the Context of Antenatal Screening: A Qualitative Study.” Health Expectations 17 (4): 555–564. doi:10.1111/j.1369-7625.2012.00784.x

- Alidu, L., and E. A. Grunfeld. 2020. “‘What a dog Will see and Kill, a cat Will see and Ignore it’: An Exploration of Health-Related Help-Seeking among Older Ghanaian men Residing in Ghana and the United Kingdom.” British Journal of Health Psychology 25 (4): 1102–1117. doi:10.1111/bjhp.12454

- Bache, R. A., K. S. Bhui, S. Dein, and A. Korszun. 2012. “African and Black Caribbean Origin Cancer Survivors: A Qualitative Study of the Narratives of Causes, Coping and Care Experiences.” Ethnicity & Health 17 (1-2): 187–201. doi:10.1080/13557858.2011.635785

- Bailey, N. V., and R. Tribe. 2021. “A Qualitative Study to Explore the Help-Seeking Views Relating to Depression Among Older Black Caribbean Adults Living in the UK.” International Review of Psychiatry 33 (1-2): 113–118. doi:10.1080/09540261.2020.1761138

- Bambra, C., R. Riordan, J. Ford, and F. Matthews. 2020. “The COVID-19 Pandemic and Health Inequalities.” Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 74 (11): 964–968. doi:10.1136/jech-2020-214401

- Bennett, N. R., D. K. Francis, T. S. Ferguson, A. J. Hennis, R. J. Wilks, E. N. Harris, M. M. MacLeish, and L. W. Sullivan. 2015. “Disparities in Diabetes Mellitus among Caribbean Populations: A Scoping Review.” International Journal for Equity in Health 14 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1186/s12939-015-0149-z

- Brewin, P., A. Jones, M. Kelly, M. McDonald, E. Beasley, P. Sturdy, G. Bothamley, and C. Griffiths. 2006. “Is Screening for Tuberculosis Acceptable to Immigrants? A Qualitative Study.” Journal of Public Health 28 (3): 253–260.

- Binder, P., Y. Borné, S. Johnsdotter, and B. Essén. 2012. “Shared Language is Essential: Communication in a Multiethnic Obstetric Care Setting.” Journal of Health Communication 17 (10): 1171–1186. doi:10.1080/10810730.2012.665421

- Bulman, K. H., and C. McCourt. 2002. “Somali Refugee Women's Experiences of Maternity Care in West London: A Case Study.” Critical Public Health 12 (4): 365–380. doi:10.1080/0958159021000029568

- Chinouya, M. J., and C. Madziva. 2019. “Late Booking Amongst African Women in a London Borough, England: Implications for Health Promotion.” Health Promotion International 34 (1): 123–132. doi:10.1093/heapro/dax069

- Comerasamy, H., B. Read, C. Francis, S. Cullings, and H. Gordon. 2003. “The Acceptability and use of Contraception: A Prospective Study of Somalian Women's Attitude.” Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 23 (4): 412–415. doi:10.1080/01443610310001209342

- Condon, L. 2002. “Maternal Attitudes to Preschool Immunisations Among Ethnic Minority Groups.” Health Education Journal 61 (2): 180–189. doi:10.1177/001789690206100208

- Cornally, N., and G. McCarthy. 2011. “Help-Seeking Behaviour: A Concept Analysis.” International Journal of Nursing Practice 17 (3): 280–288. doi:10.1111/j.1440-172X.2011.01936.x

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. 2013. Qualitative Research Checklist: 10 Questions to Help you Make Sense of Qualitative Research. Oxford: England: Public Health Resource Unit.

- Davies, M. M., and P. A. Bath. 2001. “The Maternity Information Concerns of Somali Women in the United Kingdom.” Journal of Advanced Nursing 36 (2): 237–245. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01964.x

- Delanerolle, G., P. Phiri, Y. Zeng, K. Marston, N. Tempest, P. Busuulwa, A. Shetty, et al. 2021. “A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus and Mental Health among BAME Populations.” EClinicalMedicine 38: 101016. doi:10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101016

- Edge, D. 2010. “Falling Through the net—Black and Minority Ethnic Women and Perinatal Mental Healthcare: Health Professionals’ Views.” General Hospital Psychiatry 32 (1): 17–25. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.07.007

- Edge, D. 2011. “‘It's Leaflet, Leaflet, Leaflet Then, “see you Later”’: Black Caribbean Women's Perceptions of Perinatal Mental Health Care.” British Journal of General Practice 61 (585): 256–262. doi:10.3399/bjgp11X567063

- Edge, D., and S. C. MacKian. 2010. “Ethnicity and Mental Health Encounters in Primary Care: Help-Seeking and Help-Giving for Perinatal Depression among Black Caribbean Women in the UK.” Ethnicity & Health 15 (1): 93–111. doi:10.1080/13557850903418836

- Forster, A. S., L. Rockliffe, L. A. Marlow, H. Bedford, E. McBride, and J. Waller. 2017. “Exploring Human Papillomavirus Vaccination Refusal among Ethnic Minorities in England: A Comparative Qualitative Study.” Psycho-Oncology 26 (9): 1278–1284. doi:10.1002/pon.4405

- Forster, A. S., J. Waller, H. L. Bowyer, and L. A. Marlow. 2015. “Girls’ Explanations for Being Unvaccinated or Under Vaccinated Against Human Papillomavirus: A Content Analysis of Survey Responses.” BMC Public Health 15 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1186/s12889-015-2657-6

- Freimuth, V. S., S. C. Quinn, S. B. Thomas, G. Cole, E. Zook, and T. Duncan. 2001. “African Americans’ Views on Research and the Tuskegee Syphilis Study.” Social Science & Medicine 52 (5): 797–808. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00178-7

- Garcia, R., N. Ali, C. Papadopoulos, and G. Randhawa. 2015. “Specific Antenatal Interventions for Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) Pregnant Women at High Risk of Poor Birth Outcomes in the United Kingdom: A Scoping Review.” BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 15 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1186/s12884-015-0657-2

- Gaughan, C. H., C. Razieh, K. Khunti, A. Banerjee, Y. V. Chudasama, M. J. Davies, T. Dolby, et al. 2022. “COVID-19 Vaccination Uptake Amongst Ethnic Minority Communities in England: A Linked Study Exploring the Drivers of Differential Vaccination Rates.” Journal of Public Health (Oxford, England) 45: pp. e65–e74. doi:10.1093/pubmed/fdab400

- Giuntoli, G., and M. Cattan. 2012. “The Experiences and Expectations of Care and Support among Older Migrants in the UK.” European Journal of Social Work 15 (1): 131–147. doi:10.1080/13691457.2011.562055

- Higginbottom, G. M. A. 2006. “African Caribbean Hypertensive Patients’ Perceptions and Utilization of Primary Health Care Services.” Primary Health Care Research & Development 7 (1): 27–38. doi:10.1191/1463423606pc266oa

- Iqbal, H., J. West, M. Haith-Cooper, and R. R. McEachan. 2021. “A Systematic Review to Identify Research Priority Setting in Black and Minority Ethnic Health and Evaluate Their Processes.” PloS one 16 (5): e0251685. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0251685

- Islam, Z., F. Rabiee, and S. P. Singh. 2015. “Black and Minority Ethnic Groups’ Perception and Experience of Early Intervention in Psychosis Services in the United Kingdom.” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 46 (5): 737–753. doi:10.1177/0022022115575737

- Jomeen, J., and M. Redshaw. 2013. “Ethnic Minority Women's Experience of Maternity Services in England.” Ethnicity & Health 18 (3): 280–296. doi:10.1080/13557858.2012.730608

- Khan, Z. 2021. “Ethnic Health Inequalities in the UK's Maternity Services: A Systematic Literature Review.” British Journal of Midwifery 29 (2): 100–107. doi:10.12968/bjom.2021.29.2.100

- The Kings Fund. 2021. The Health of people from Ethnic Minority Groups in England. [online]. Accessed 2 September 2021. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/health-people-ethnic-minority-groups-england.

- Koffman, J., and I. J. Higginson. 2001. “Accounts of Carers’ Satisfaction with Health Care at the end of Life: A Comparison of First Generation Black Caribbeans and White Patients with Advanced Disease.” Palliative Medicine 15 (4): 337–345. doi:10.1191/026921601678320322

- Kolvenbach, S., L. Fernández de la Cruz, D. Mataix-Cols, N. Patel, and A. Jassi. 2018. “Perceived Treatment Barriers and Experiences in the use of Services for Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder Across Different Ethnic Groups: A Thematic Analysis.” Child and Adolescent Mental Health 23 (2): 99–106. doi:10.1111/camh.12197

- Lindenmeyer, A., S. Redwood, L. Griffith, S. Ahmed, and J. Phillimore. 2016. “Recent Migrants’ Perspectives on Antibiotic use and Prescribing in Primary Care: A Qualitative Study.” British Journal of General Practice 66 (652): e802–e809. doi:10.3399/bjgp16X686809

- Loewenthal, D., A. Mohamed, S. Mukhopadhyay, K. Ganesh, and R. Thomas. 2012. “Reducing the Barriers to Accessing Psychological Therapies for Bengali, Urdu, Tamil and Somali Communities in the UK: Some Implications for Training, Policy and Practice.” British Journal of Guidance & Counselling 40 (1): 43–66. doi:10.1080/03069885.2011.621519

- Margariti, C., K. Gannon, R. Thompson, J. Walsh, and J. Green. 2019. “Experiences of UK African-Caribbean Prostate Cancer Survivors of Discharge to Primary Care.” Ethnicity & Health 45: 1–15. doi:10.1080/13557858.2019.1606162

- Marlow, L. A., L. M. McGregor, J. Y. Nazroo, and J. Wardle. 2014. “Facilitators and Barriers to Help-Seeking for Breast and Cervical Cancer Symptoms: A Qualitative Study with an Ethnically Diverse Sample in London.” Psycho-Oncology 23 (7): 749–757.

- Marlow, L. A., J. Waller, and J. Wardle. 2015. “Barriers to Cervical Cancer Screening among Ethnic Minority Women: A Qualitative Study.” Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care 41 (4): 248–254. doi:10.1136/jfprhc-2014-101082

- Marlow, L. A., J. Wardle, A. S. Forster, and J. Waller. 2009. “Ethnic Differences in Human Papillomavirus Awareness and Vaccine Acceptability.” Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 63 (12): 1010–1015. doi:10.1136/jech.2008.085886

- McCartney, G., F. Popham, R. McMaster, and A. Cumbers. 2019. “Defining Health and Health Inequalities.” Public Health 172: 22–30. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2019.03.023

- Mclean, C., C. Campbell, and F. Cornish. 2003. “African-Caribbean Interactions with Mental Health Services in the UK: Experiences and Expectations of Exclusion as (re) Productive of Health Inequalities.” Social Science & Medicine 56 (3): 657–669. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00063-1

- Mupandawana, E. T., and R. Cross. 2016. “Attitudes Towards Human Papillomavirus Vaccination among African Parents in a City in the North of England: A Qualitative Study.” Reproductive Health 13 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1186/s12978-016-0209-x

- Nanton, V., and J. Dale. 2011. “‘It Don't Make Sense to Worry Too Much’: The Experience of Prostate Cancer in African-Caribbean men in the UK.” European Journal of Cancer Care 20 (1): 62–71. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2354.2009.01155.x

- Newton, J. T., N. Thorogood, V. Bhavnani, J. Pitt, D. E. Gibbons, and S. Gelbier. 2001. “Barriers to the use of Dental Services by Individuals from Minority Ethnic Communities Living in the United Kingdom: Findings from Focus Groups.” Primary Dental Care (4): 157–161. doi:10.1308/135576101322462228

- NHS. 2023. Appointments in General Practice January 2023 - NHS Digital. [online] NHS Digital. Accessed 23 February 2023. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/appointments-in-general-practice/january-2023.

- Norman, P., and M. Conner. 1996. “Predicting Health-Check Attendance Among Prior Attenders and Nonattenders: The Role of Prior Behavior in the Theory of Planned Behavior.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 26 (11): 1010–1026.

- O'Donnell, C. A., M. Higgins, R. Chauhan, and K. Mullen. 2007. “They Think We're OK and we Know We're not”. A Qualitative Study of Asylum Seekers’ Access, Knowledge and Views to Health Care in the UK.” BMC Health Services Research 7 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-7-75

- Office of National Statistics. 2020. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Related Deaths by Ethnic Group, England and Wales: 2 March 2020 to 10 April 2020. [online]. Accessed 19 April September 2022. https://www.ons.gov.uk/releases/coronavirusrelateddeathsbyethnicgroupenglandandwales2march2020to10april2020.

- Phillips, K. M. 2014. “Rivers of Blood and Babylon: An Ethnography of Social Suffering and Resilience Among Caribbean Service Users in London.” Doctoral diss., Emory University.

- Public Health England. 2020. Disparities in the Risk and Outcomes of COVID-19. Public Health England.

- Puthussery, S., K. Twamley, S. Harding, J. Mirsky, M. Baron, and A. Macfarlane. 2008. “‘They're More Like Ordinary Stroppy British Women’: Attitudes and Expectations of Maternity Care Professionals to UK-Born Ethnic Minority Women.” Journal of Health Services Research & Policy 13 (4): 195–201. doi:10.1258/jhsrp.2008.007153

- Rabiee, F., and P. Smith. 2007. “Too Much Overlooking.” Mental Health Today (Brighton, England) 2007: 26–29.

- Razieh, C., F. Zaccardi, N. Islam, C. L. Gillies, Y. V. Chudasama, A. Rowlands, D. E. Kloecker, M. J. Davies, K. Khunti, and T. Yates. 2021. “Ethnic Minorities and COVID-19: Examining Whether Excess Risk is Mediated Through Deprivation.” The European Journal of Public Health 31 (3): 630–634. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckab041

- Robertson, J., R. Raghavan, E. Emerson, S. Baines, and C. Hatton. 2019. “What do we Know About the Health and Health Care of People with Intellectual Disabilities from Minority Ethnic Groups in the United Kingdom? A Systematic Review.” Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 32 (6): 1310–1334. doi:10.1111/jar.12630

- Sass, B., J. Moffat, K. Mckenzie, and K. Bhui. 2009. “A Learning and Action Manual to Improve Care Pathways for Mental Health and Recovery among BME Groups.” International Review of Psychiatry 21 (5): 472–481. doi:10.1080/09540260802204089

- Shangase, P., and C. O. Egbe. 2015. “Barriers to Accessing HIV Services for Black African Communities in Cambridgeshire, the United Kingdom.” Journal of Community Health 40 (1): 20–26. doi:10.1007/s10900-014-9889-8

- Straus, L., A. McEwen, and F. M. Hussein. 2009. “Somali Women's Experience of Childbirth in the UK: Perspectives from Somali Health Workers.” Midwifery 25 (2): 181–186. doi:10.1016/j.midw.2007.02.002

- Thomas, F., P. Aggleton, and J. Anderson. 2010. ““If I Cannot Access Services, Then There is no Reason for me to Test”: The Impacts of Health Service Charges on HIV Testing and Treatment Amongst Migrants in England.” AIDS Care 22 (4): 526–531. doi:10.1080/09540120903499170

- Thomas, V. J., and L. M. Taylor. 2002. “The Psychosocial Experience of People with Sickle Cell Disease and its Impact on Quality of Life: Qualitative Findings from Focus Groups.” British Journal of Health Psychology 7 (3): 345–363. doi:10.1348/135910702760213724

- Wagstaff, C., H. Graham, and R. Salkeld. 2018. “Qualitative Experiences of Disengagement in Assertive Outreach Teams, in Particular for “Black” men: Clinicians’ Perspectives.” Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 25 (2): 88–95. doi:10.1111/jpm.12441

- WHO. 2021. Primary Health Care. [online]. Accessed 2 September 2021. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/primary-health-care.