ABSTRACT

Background:

Australia’s overseas-born population continues to grow. This population is disproportionately affected by chronic, non-communicable diseases. Physical activity is the cornerstone of all chronic disease management. Engaging people from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds in physical activity is an important public health objective. The purpose of this scoping review was to examine the factors that shape physical activity participation among people from CALD backgrounds in Australia.

Methods:

This scoping review followed Arksey and O’Malley’s framework. Medline, Embase and CINAHL were searched with key words relating to ‘physical activity’, ‘CALD’ and ‘Australia’ in July 2021 and again in February 2022 for qualitative studies published in English since 2000. Exclusion criteria were: participants < 18 years old, studies specifically focusing on populations with health issues, pregnant or postpartum states. Methodological quality of included studies was evaluated using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme with the purpose of informing future research. Data extracted from each study were analysed thematically and results were interpreted using Acculturation theory.

Results:

Of the 1130 studies, 17 met the inclusion criteria. Findings from each study were captured in three themes: Perceptions of physical activity; Acceptability and Appropriateness; and Access. Following migration, a decrease in physical activity, especially leisure-time activity, was reported. Common factors influencing physical activity engagement included perceptions of physical activity and wellbeing; language, financial and environmental barriers; as well as social, cultural, and religious considerations.

Conclusion:

This review identified several factors which may interact and contribute to the decline in self-reported physical activity upon migration. Findings from this review may be used to inform future health promotion initiatives targeting people from CALD backgrounds. Future research may benefit from devising a shared definition of physical activity and studying different CALD communities over time.

Introduction

Internationally, there has been steady growth in the number of migrants over the last two decades. Notwithstanding the disruptions imposed by COVID-19, in 2020, there were 281 million people living outside their country of origin, encompassing 3.6 percent of the world’s population (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Citation2021). In Australia, approximately one third of the population is born overseas with most migrants from England, India and China (Australian Bureau of Statistics Citation2021). The term ‘culturally and linguistically diverse’ (CALD) is used in this paper to refer to people living in Australia who were born overseas or are descendants of those who were born overseas and differ in language and/or culture to the wider population (Parliament of Victoria Citation2021). This encompasses migrants as well as refugees and asylum seekers who face additional hurdles beyond the struggles and consequences of migration.

The growing diversity of the Australian population imposes several population health challenges. Some researchers have proposed that individuals from CALD communities are disproportionately affected by chronic diseases especially hypertension, diabetes, and obesity, all of which contribute to a higher burden of cardiovascular disease (Davidson et al. Citation2003; Johnson and Fulp Citation2002; Torpy, Lynm, and Glass Citation2003). In 2001, approximately 35% of people who reported having diabetes were born overseas in spite of making up only 28% of the Australian population (Holdenson et al. Citation2003). Despite a higher prevalence and burden of non-communicable diseases, individuals from CALD communities appear less likely to engage in preventative measures like physical activity compared to people from non-CALD backgrounds in Australia (Marquez and McAuley Citation2006; Henderson, Kendall, and See Citation2011). In particular those with limited English proficiency report significantly lower rates of participation in physical activity compared to their Australian counterparts (participation rate of 36.9% vs 66.0% respectively) (Australian Bureau of Statistics Citation2006).

Physical activity is the cornerstone of all chronic disease management (Das and Horton Citation2016). It is associated with numerous benefits including reductions in metabolic syndrome, promotion of musculoskeletal health, mental wellbeing as well as fostering social cohesion (Lewis et al. Citation2019; Penedo and Dahn Citation2005). Accepted scientific definition of physical activity is a body movement produced by skeletal muscles that results in the expenditure of energy (Caspersen, Powell, and Christenson Citation1985). Guidelines recommend adults participate in 150–300 min of moderate intensity physical activity each week to obtain health benefits (Bull et al. Citation2020). Increasing participation in physical activity to both prevent and manage chronic disease among people from CALD backgrounds is an important public health objective (Briggs et al. Citation2019).

To positively influence physical activity behaviours with corresponding improvements in health, it is critical to understand the factors that influence participation in physical activity among people from CALD backgrounds. This can then inform the design and implementation of culturally appropriate interventions that meet communities’ needs and preferences. Previous reviews have investigated correlates of physical activity behaviour amongst adults from CALD communities in Western countries with individual health, past exercise behaviour, neighbourhood characteristics and access to transport been reported as predictors of physical activity engagement after migration (Caperchoine, Mummery, and Joyner Citation2009; O’Driscoll et al. Citation2014). However, health behaviour is heavily influenced by context (Bandura Citation2004), and understanding the factors that shape physical activity participation within a given context is necessary to inform local and national policy. In the past decade, a number of qualitative studies has investigated the experience of physical activity among CALD populations living in Australia. In this scoping review, we synthesise findings from these studies to identify factors shaping physical activity participation in the Australian context.

Methods

Methodological framework

This scoping review was guided by an established framework described by Arksey and O’Malley (Arksey and O’Malley Citation2005). Themes were constructed to present a narrative account of the existing literature however no attempt was made to weight evidence. Acculturation theory was used to guide interpretation of results and assist in contextualisation of findings in the discussion section. This theory describes the process of adaptation that may occur due to continuous contact with culturally dissimilar people, groups and social influences. The acculturation experience is highly specific, influenced by factors including the country of origin, the social composition of the communities in which they settle, fluency in the language of the host country amongst others (Gibson Citation2001).

Search strategy and selection criteria

Electronic databases Medline, Embase and CINAHL were searched in July 2021 and again in February 2022 using key words relating to ‘physical activity’, ‘CALD’ and ‘Australia’. Boolean operator ‘AND’ was used to combine concepts with ‘OR’ used for key words under each concept (see example search ). Title, abstract and full text screening based on the eligibility criteria (see ) was conducted independently by pairs of authors (QW and PO or LH) on COVIDENCE systematic review software (Covidence systematic review software). Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion with another author (SB).

Table 1. Search strategy in MEDLINE.

Table 2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Data extraction and analysis

Data extracted from each study comprised: participant characteristics (age, sex, cultural and linguistic background where available), study characteristics (setting, sample size, method of data collection) and findings relevant to physical activity participation amongst people from CALD backgrounds in Australia. Relevant findings extracted related to perceptions about physical activity participation (including themes headings, descriptive sentences, and participant quotes). Inductive codes were generated by the first author (QW) through line by line reading of extracted findings. Codes were then grouped into categories describing the factors that shape physical activity participation through discussion between four authors (QW, SB, RWK, MD). Where appropriate, factors specific to certain CALD communities were identified. Finally, categories were consolidated into themes describing overarching factors influencing physical activity participation. Emerging themes were re-checked against original sources to ensure they remained grounded in participant experiences as interpreted by the authors of each study. Consensus on final themes was achieved through group discussion in which themes were considered in the context of existing literature on physical activity participation in the wider population, health behaviour theory and acculturation theory. The multidisciplinary authorship team comprised of clinician-researchers with backgrounds in orthopaedic nursing and physiotherapy; a medical student, social scientist and applied linguist with expertise in health communication.

Methodological rigour

While not a necessary step in the Arskey and O’Malley framework, a quality assessment was conducted in order to inform future qualitative studies in the field, rather than to determine how robust individual study findings were. In addition, it has been suggested that inclusion of a quality assessment such as the CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (Citation2022)) may improve the uptake and relevance of scoping review findings, hence its inclusion here (Levac, Colquhoun, and O’Brien Citation2010). Using the CASP, each study was evaluated by pairs of authors (QW and PO or LH) who independently scored ‘yes’, ‘no’ or ‘unclear’ for each of the ten criteria on the checklist. Discrepancies between reviewers were resolved by discussion with another author (SB) until consensus was reached.

Results

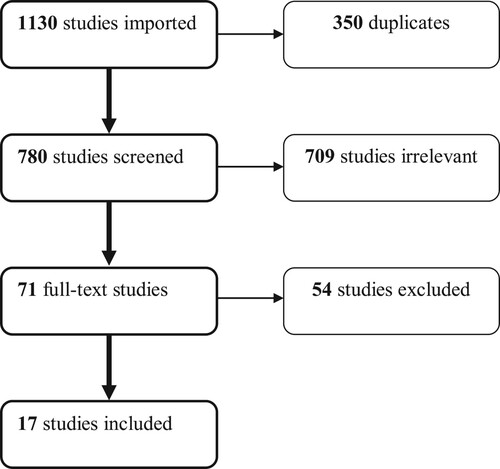

The primary search was conducted in July 2021 and updated in February 2022. The search retrieved 1130 articles, with 680 titles remaining after removal of duplicates. From 680 titles and abstracts, 59 full text articles were screened. Seventeen met the eligibility criteria and were included in the final dataset (see ).

The 17 studies included 595 participants from CALD communities, 442 (74%) were women. Thirty-three additional participants were stakeholders interacting with CALD communities. Twenty-seven CALD communities were represented including Afghanistan, Arab-Australians (majority from Lebanon), Arabic speaking people (countries not specified), Bosnia, Burkina Faso, Burundi, China, Cook Islands (Pukapuka people), Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Hong Kong, India, Iran, Iraq, Liberia, Middle East (majority from Lebanon), Myanmar, Philippines, Somalia, South Sudan, Sri Lanka, Sub Saharan Africa (countries not specified), Sudan, Syria, Togo and Vietnam (see ).

Table 3. Characteristics of included studies.

Only one of the 17 included studies satisfied all 10 quality domains on the CASP. Domain one (‘Was there a clear statement of the aims of the research?’) and domain two (‘Is a qualitative methodology appropriate?’) were met in all 17 studies. Most studies failed to address domain six (‘Has the relationship between the researchers and participants been adequately considered?’) with only six studies providing appropriate detail (See ).

Table 4. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) assessment.

Findings from each study were captured in three themes: Perceptions of physical activity; Acceptability and Appropriateness; and Accessibility. These themes are described narratively below, supported by quotes (Q) extracted from included studies (see ).

Table 5. Themes.

Theme 1. Perceptions of physical activity

Misconceptions about what constitutes physical activity and the consequences of being physically active appeared to play a role in influencing physical activity behaviour among participants in the included studies. Physical activity was often defined in a broad context, with definitions ranging from incidental activities to structured physical actions including sport (Caperchione et al. Citation2011; Caperchoine, Mummery, and Joyner Citation2009; El Masri, Kolt, and George Citation2021; Fernandes et al. Citation2021). Studies including individuals who identified as Arab-Australian, Bosnian, Filipino and Sudanese found that participants were unaware or unclear of the distinction between physical activity and exercise (Caperchione et al. Citation2011) and appeared to be unfamiliar with recommended guidelines for physical activity (El Masri, Kolt, and George Citation2021). (Q1-4)

Many participants were cognizant of the benefits of physical activity on physical health (Koo Citation2011; El Masri, Kolt, and George Citation2021). (Q6) However for some, excessive physical activity was a cause for health concern (Caperchione et al. Citation2011) and the physiological responses to exercise acted as a deterrent (El Masri, Kolt, and George Citation2021). In a study of African migrants from Somalia, Ethiopia and Sudan, some participants reported restricting physical activity because weight gain was culturally endorsed within the community (Renzaho, McCabe, and Swinburn Citation2012). (Q6-7) There were also inconsistent views on the impact of physical activity on mental, emotional and cognitive health among participants who self-identified as Chinese as well as first generation migrants from Afghanistan, India and Sri Lanka (You et al. Citation2021; Willcox-Pidgeon et al. Citation2021). While some participants understood the mental health benefits of being physically active, participants who were asylum seekers, refugees (Hartley, Fleay, and Tye Citation2017) or migrants born in regions affected by unrest, such as Afghanistan, Iran, Syria, Myanmar, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Liberia, South Sudan, Togo, Burkina Faso and Burundi (Reis et al. Citation2020) poor mental health and associated amotivation was reported as a barrier to physical activity participation. (Q8-11) Misconceptions about the importance of physical activity in preventative health meant some participants only engaged in physical activity once they were already experiencing symptoms of ill-health to prevent further deterioration in well-being (El Masri, Kolt, and George Citation2021; You et al. Citation2021; Caperchione et al. Citation2011; Koo Citation2011; Addo et al. Citation2019). (Q12-15) For others, advancing age and existing health conditions limited the type and intensity of physical activity they felt able to engage in (Koo Citation2011; Caperchione et al. Citation2011; El Masri, Kolt, and George Citation2021; Addo et al. Citation2019). (Q16-17)

There was a consistent decline in self-reported physical activity levels upon migration in all five articles that explored this change (Addo et al. Citation2019; El Masri, Kolt, and George Citation2021; Caperchione et al. Citation2011; Reis et al. Citation2020; Oliver et al. Citation2007), four of which focussed on migrants from developing countries (Addo et al. Citation2019; El Masri, Kolt, and George Citation2021; Caperchione et al. Citation2011; Reis et al. Citation2020). On close examination, participants in these studies were mainly referring to incidental physical activities. For many, such as participants from the Cook Islands (the Pukapuka people) the lifestyle in their native country was inherently more physically active particularly in the context of work (Oliver et al. Citation2007; Reis et al. Citation2020) and housekeeping (Caperchione et al. Citation2011). Participants cited convenient access to labour saving devices such as cars, elevators and laundry machines upon migration as a reason why incidental physical activity was reduced (Addo et al. Citation2019; Reis et al. Citation2020; Caperchione et al. Citation2011; El Masri, Kolt, and George Citation2021; Oliver et al. Citation2007). This was particularly the case for participants of lower socioeconomic status who reported greater reductions in physical activity upon migration (Caperchione et al. Citation2011). Most of the physical activity undertaken by migrants in Australia was reportedly transport related (Caperchione et al. Citation2011) or traditional activities (Oliver et al. Citation2007; Koo Citation2011; Caperchoine, Mummery, and Joyner Citation2009). In a study exploring leisure-time physical activity among humanitarian migrants in regional Australia, participants who engaged in physical activity prior to migration tended to remain more physically active than those who never engaged at all (Reis et al. Citation2020). While leisure-time physical activities that migrants previously engaged in were often reportedly discontinued after arrival in Australia (Reis et al. Citation2020), walking was a popular exercise for its simplicity and convenience, especially among those experiencing low self-esteem and poor body image (Caperchoine, Mummery, and Joyner Citation2009; Koo Citation2011; Oliver et al. Citation2007; You et al. Citation2021). (Q18-22)

Theme 2. Acceptability and appropriateness

Cultural and religious factors appeared to play a role in defining what was acceptable and appropriate physical activity behaviour. Among participants from Arabic (El Masri, Kolt, and George Citation2021) and Bosnian-speaking backgrounds (Caperchione, Kolt, and Mummery Citation2013), physical activity was seen as a religious obligation. Among women, gender roles established and reinforced through culture were a commonly reported barrier to physical activity. The cultural norm for many CALD communities in the included studies was for women to take up the bulk of domestic duties regardless of employment status leaving them limited time and energy to engage in physical activity (Caperchione et al. Citation2011; Caperchoine, Mummery, and Joyner Citation2009; El Masri, Kolt, and George Citation2021). (Q23-26) Poor body image and low self-esteem among female Arab-Australian participants appeared to be exacerbated by the lack of appropriate environment and type of activities available (El Masri, Kolt, and George Citation2021). Certain settings such as beaches and activities where revealing clothes were the norm could be deemed inappropriate for women from conservative cultures like Chinese (Koo Citation2011) and Muslim Arab-Australians (El Masri, Kolt, and George Citation2021) and first generation migrants from Afghanistan, India and Sri Lanka (Willcox-Pidgeon et al. Citation2021). (Q27) Female Arab migrants suggested that gender exclusive settings were required for public modesty (Caperchione et al. Citation2011; El Masri, Kolt, and George Citation2021). (Q28-29) The desire to avoid imposing on others (e.g. to family members and friends) within the Chinese culture served as a barrier to physical activity participation (You et al. Citation2021), especially to those conducted at community centres (Koo Citation2011).

Many participants in the included studies reported high levels of social isolation (Reis et al. Citation2020; Hartley, Fleay, and Tye Citation2017; El Masri, Kolt, and George Citation2021; Caperchione et al. Citation2011; Pink, Mahoney, and Saunders Citation2020) and acknowledged a positive correlation between physical activity behaviours and social supports (Koo Citation2011; Caperchione et al. Citation2011; El Masri, Kolt, and George Citation2021; Hartley, Fleay, and Tye Citation2017; Reis et al. Citation2020; You et al. Citation2021; Willcox-Pidgeon et al. Citation2021). Participants in a study of Chinese adults attributed the mental health benefits of being physically active to the social aspect of participation rather than the physical activity itself (You et al. Citation2021). A strong preference for group activities (Addo et al. Citation2019; Cerin et al. Citation2019; El Masri, Kolt, and George Citation2021; Caperchione et al. Citation2011) led by a leader/program coordinator (Caperchoine, Mummery, and Joyner Citation2009; Willcox-Pidgeon et al. Citation2021) with face to face delivery (El Masri, Kolt, and George Citation2021; O’Callaghan et al. Citation2021) was reported amongst individuals of diverse CALD background. (Q30-34) Social supports, especially from family, were seen as important facilitators of participation in physical activity; the absence of family support in Australia made it difficult, particularly for parents (Caperchione et al. Citation2011; Reis et al. Citation2020; El Masri, Kolt, and George Citation2021). (Q35) Some parents from Middle Eastern backgrounds engaged in physical activity to stimulate greater participation by their children (Hayba, Shi, and Allman-Farinelli Citation2021; Willcox-Pidgeon et al. Citation2021). In one study, participants from sub-Saharan Africa suggested that social media messages promoting physical activity were an enabler for greater participation (Addo et al. Citation2019).

Theme 3. Accessibility

Participants in the included studies experienced reduced access to existing services and initiatives that were intended to support physical activity participation. The participants suggested these were often limited in frequency (El Masri, Kolt, and George Citation2021; Cerin et al. Citation2019), of short duration (Willcox-Pidgeon et al. Citation2021) and were not tailored to the needs and preferences of CALD communities (Caperchione, Kolt, and Mummery Citation2013; El Masri, Kolt, and George Citation2021). Language barriers, financial considerations and environmental factors influenced uptake of such programs. (Q36-39)

Language barriers were reported in several studies (Caperchione, Kolt, and Mummery Citation2013; Caperchione et al. Citation2011; Cerin et al. Citation2019; El Masri, Kolt, and George Citation2021; Hartley, Fleay, and Tye Citation2017; Reis et al. Citation2020; Willcox-Pidgeon et al. Citation2021). Due to limited English proficiency, individuals including those who identified as first generation Chinese frequently reported being unaware of existing services and how to access them (Reis et al. Citation2020; Cerin et al. Citation2019) or they were deterred from ongoing participation in initiatives conducted in English (Caperchione, Kolt, and Mummery Citation2013; Caperchione et al. Citation2011). In one study, asylum seekers from Afghanistan, Sri Lanka and Iran who had arrived to Australia by boat noted that government policy denied them access to adequate English classes (Hartley, Fleay, and Tye Citation2017). In a study of Chinese migrants, interpreters alone were perceived as insufficient to engage people from CALD backgrounds and participants perceived a greater hesitancy among stakeholders to recommend programs to those with limited English language proficiency (O’Callaghan et al. Citation2021). Instead, bicultural/bilingual programs were viewed favourably and seen as critical for the success and effectiveness of programs (O’Callaghan et al. Citation2021). (Q40-42)

Financial barriers were reported in several studies (Addo et al. Citation2019; Caperchione, Kolt, and Mummery Citation2013; Caperchoine, Mummery, and Joyner Citation2009; Cerin et al. Citation2019; El Masri, Kolt, and George Citation2021; Reis et al. Citation2020; Smith, Thomas, and Batras Citation2016; Pink, Mahoney, and Saunders Citation2020) especially among asylum seekers who did not yet have the right to work in Australia (Hartley, Fleay, and Tye Citation2017). Financial resources tended to be dedicated to daily necessities with little left for health promotion measures such as physical activity (Caperchione, Kolt, and Mummery Citation2013; Hartley, Fleay, and Tye Citation2017). Indeed, for some participants, physical activity was viewed as a ‘luxury’ rather than ‘necessity’ (Caperchione et al. Citation2011; Willcox-Pidgeon et al. Citation2021). Costs of registration and membership fees associated with structured physical activity programs were identified as barriers to participation by participants who were first generation migrants from Sub-Saharan Africa (Addo et al. Citation2019). Some participants prioritised financing the participation of their children in organised physical activity, in particular swimming, as water confidence was considered an important life skill (Willcox-Pidgeon et al. Citation2021). (Q43-46)

Environmental factors were also recognised as major determinants of physical activity participation. Many participants resided in low-middle socioeconomic areas (Hayba, Shi, and Allman-Farinelli Citation2021) with higher than average crime rates and expressed safety concerns regarding engagement in traditional (Caperchione et al. Citation2011) and outdoor physical activities (Addo et al. Citation2019; Caperchoine, Mummery, and Joyner Citation2009; Oliver et al. Citation2007; Renzaho, McCabe, and Swinburn Citation2012; You et al. Citation2021). Participants in studies that included refugee migrants from Myanmar, Afghanistan, Eritrea as well as Arab Australians reflected that safety concerns were exacerbated by the contested nature of refugee settlement in Australia and stereotypical media portrayals which contributed to racist behaviour among some members of the mainstream Australian society (El Masri, Kolt, and George Citation2021; Pink, Mahoney, and Saunders Citation2020). (Q47-50) However, locally available physical activity destinations were regarded as key enablers to greater engagement in physical activity (Cerin et al. Citation2019; El Masri, Kolt, and George Citation2021), particularly among newly arrived migrants who often did not have access to private vehicles and found public transport intimidating (Caperchoine, Mummery, and Joyner Citation2009), inadequate (Cerin et al. Citation2019; Caperchione, Kolt, and Mummery Citation2013; Koo Citation2011; Pink, Mahoney, and Saunders Citation2020) and/or unaffordable (Hartley, Fleay, and Tye Citation2017). (Q51-52) Climate and weather conditions were reported by some members of CALD community to discourage outdoor physical activity (Addo et al. Citation2019; Caperchoine, Mummery, and Joyner Citation2009; You et al. Citation2021) and associated with amotivation. (Q53-54)

Discussion

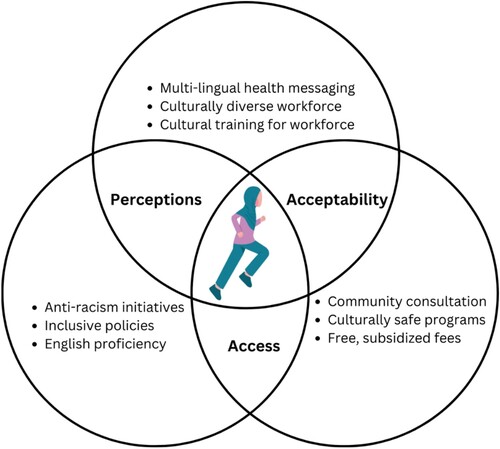

This synthesis of qualitative findings related to physical activity participation among CALD populations in Australia identified three overarching themes that shaped physical activity behaviour: 1. Perceptions of physical activity; 2. Access to services and initiatives; 3. Acceptability and Appropriateness. These findings can be compared to that of the broader Australian population and considered through a lens of acculturation theory (Gibson Citation2001), leading to recommendations for future policy and programs to support physical activity in Australian CALD communities (see ).

Figure 2. Recommendations to increase physical activity participation for people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds in Australia.

The consistent decline in self-reported physical activity upon migration in all five articles exploring this change is consistent with what previous researchers have labelled the ‘healthy immigrant effect’. This effect is whereby migrants arrive in a Western country in good health, but experience a decline in health as a result of continuous contact with culturally dissimilar people, groups and social influences; known as acculturation (Gibson Citation2001). While acculturation has been associated with behaviours such as sedentarism and consumption of high caloric, processed diets (Hosper, Klazinga, and Stronks Citation2007a, Citation2007b), greater assimilation into the host culture has been linked to higher levels of physical activity (O’Driscoll et al. Citation2014), especially in the non-occupational domain (Hosper, Klazinga, and Stronks Citation2007; Gerber, Barker, and Pühse Citation2012). Indeed, participants in included studies often expressed a need to balance the decrease in incidental activities due to the more sedentary lifestyle of Australia with increases in intentional formalised physical activity such as sport and exercise. Host language proficiency is linked to greater assimilation (Dassanayake et al. Citation2011). Among Australian migrants, English language skills are correlated with important health benefits for women and increased physical activity in men (Guven and Islam Citation2015), highlighting the need to provide language adapted interventions for CALD communities. Some of the included studies focused on asylum seekers who had been in migrant detention centres (Reis et al. Citation2020; Renzaho, McCabe, and Swinburn Citation2012; Hartley, Fleay, and Tye Citation2017; Pink, Mahoney, and Saunders Citation2020), While none explored time and experiences in detention centres and their impact on physical activity behaviour, previous literature has identified that past trauma including exposure to extreme violence, human rights abuses, persecution (Shawyer et al. Citation2017), prolonged time in detention (Newman, Proctor, and Dudley Citation2013) and ongoing uncertainty for the future may all contribute to the prevalence of mental health concerns among refugee communities. People with severe mental illness have been found to have significantly lower levels of physical activity compared to controls (Nyboe and Lund Citation2013). Experiences of racism further shaped physical activity behaviour for some participants in the included studies. Racism can be defined as a system of oppression which ‘creates hierarchies between social groups based on perceived differences relating to origin and cultural background’ and is expressed and shaped by policies, practices and media (Ben et al. Citation2022, page 2). Research in Australia has identified a link between exposure to racism and poorer health, including higher body mass index, depression and sleep disturbance (Priest et al. Citation2017; Sharif et al. Citation2021). Initiatives at an individual, social and political level to build a more inclusive Australia are fundamental to improving the health of CALD communities.

Beyond factors relating to migration, CALD communities also face general barriers to greater engagement with physical activity. Misconceptions about what physical activity is, how much is necessary and why, have been noted among the wider Australian population with suggestions that many Australians are ‘in the dark’ about physical activity (Hawke et al. Citation2022; Fredriksson et al. Citation2018). While most studies to date have focussed on individual behavioural change approaches, calls have been made for greater focus on public health and policy interventions to increase physical activity in the general population (Ding et al. Citation2020). Public health messaging tailored to the linguistic and literacy needs of diverse Australian communities is needed to improve knowledge about physical activity among people from CALD backgrounds. While the majority of participants in the studies included in this scoping review recognised the benefits of being physically active, two studies examining the perspectives of service providers (Smith, Thomas, and Batras Citation2016; Caperchione, Kolt, and Mummery Citation2013), perceived a lack of understanding about preventative health existed in most CALD communities. This discrepancy between service providers and CALD communities underscores the importance of building a culturally diverse work force and of cultural awareness training so that service providers understand the broader factors contributing to physical activity participation among people from CALD backgrounds.

Indeed, consistent with health behaviour theory (Bandura Citation2004), our findings suggest that knowledge alone is unlikely to be sufficient to increase physical activity participation in CALD communities. Strategies are required to address financial, environmental, and social barriers and improve access to cultural safe environments in which people are able to participate in physical activity. In this review, service providers and CALD communities recognised limited availability of targeted physical activity programs (Caperchione, Kolt, and Mummery Citation2013; Cerin et al. Citation2019; El Masri, Kolt, and George Citation2021). While resource strain is a suggested cause for this (Caperchione, Kolt, and Mummery Citation2013), there was a lack of discussion in the included studies on the sources of funding and what that entailed (Caperchione, Kolt, and Mummery Citation2013; Smith, Thomas, and Batras Citation2016). A variety of strategies have been trialled in practice to address financial constraints to physical activity including free-of-charge activities and subsidised fees but with little evidence of a financially sustainable model (Smith, Thomas, and Batras Citation2016). These challenges suggest the need to trial alternative, innovative approaches with involvement of non-traditional sectors. Proximity to parks, walking tracks, shops and recreational centres have been proposed as strategies to address environmental barriers to physical activity engagement (Barnett et al. Citation2017; Van Cauwenberg et al. Citation2018). Improvements in public transport networks have demonstrated the potential to improve physical activity participation (Brown et al. Citation2019), although limitations with the existing system were reported as barriers to greater participation with formal physical activity programs by participants in included studies (Cerin et al. Citation2019; Caperchione, Kolt, and Mummery Citation2013; Koo Citation2011; Pink, Mahoney, and Saunders Citation2020; Caperchoine, Mummery, and Joyner Citation2009; Hartley, Fleay, and Tye Citation2017). Assistance with transport through provision of private vehicles, community buses (Smith, Thomas, and Batras Citation2016), orientation sessions where a facilitator guides individuals on how to reach destinations may also be trialled. Collaborative partnerships with external organisations offering services to CALD communities may be crucial for program sustainability through sharing of equipment, facilities and staff. Cross-promotion of initiatives between partners may also facilitate greater awareness and engagement with programs. Empowering members of CALD communities to be involved in the design and implementation of initiatives would further strengthen community trust. In particular, as noted elsewhere (Caperchione et al. Citation2011), placing women at the centre of program development may help address barriers such as cultural modesty, acceptable dress and childcare when participating in physical activities.

Integrating findings from our scoping review with an international systematic review of cultural adaptations to interventions seeking to improve physical activity participation, (El Masri, Kolt, and George Citation2022) we suggest that future culturally appropriate interventions in the Australian context should incorporate community consultation, language adjustments, use of bilingual/bicultural personnel and culturally relevant material or content to optimise reach, adoption and effectiveness. Future interventions should also be theoretically-informed and embedded within implementation frameworks to facilitate scale-up, adaptation to diverse groups and sustainability over time.

Design considerations and future research

This scoping review focused on qualitative studies to enable in-depth insight into the factors that shape and define physical activity behaviours among people from CALD backgrounds living in Australia. We included studies that explored the perspective of both people from CALD backgrounds and service providers to enable insight into individual, community, service and policy level factors. A key limitation of this study is the secondary analysis of primary data. The definition of physical activity was often not established in the included studies. Individuals from different backgrounds may have conceptualised physical activity in different ways which may have influenced their responses. Future research would benefit from establishing a shared definition of physical activity. To facilitate our interpretations, we adopted the accepted scientific definition of physical activity (Caspersen, Powell, and Christenson Citation1985), also adopted by some of the included studies. The majority of included studies were cross-sectional in nature and relied on recall of change in physical activity on migration. Future prospective studies are needed to understand how perceptions and behaviours related to physical activity change over time. Social desirability biases may have influenced participants’ responses in the included studies, with only 6/17 studies reporting on the nature of the relationship between the study participants and researchers. Future qualitative studies involving people from CALD backgrounds are encouraged to provide evidence of reflexivity so that readers can assess the credibility of interpretations.

Most of the included studies were based in New South Wales and Victoria, the two states in Australia with the greatest proportion of CALD populations (Australian Bureau of Statistics Citation2021). Future research should include individuals from diverse regions in Australia to inform national guidelines regarding physical activity amongst individuals of CALD backgrounds. The main CALD communities studied in this review include African, Arabic speaking, Filipino and Chinese migrants among others as well as refugees and asylum seekers. Future research should extend to other CALD communities across Australia. While we identified overarching themes that were common across the communities included in this review, it is important to acknowledge the diversity that exists among CALD communities in Australia. Within the major themes identified, where possible, we described findings relevant to specific groups.

Conclusion

This scoping review of qualitative studies investigated the factors that shape physical activity participation among CALD communities in Australia. Physical activity for CALD communities encompassed a wide range of events from incidental activities to structured exercises. Several factors appeared to contribute to the decline in self-reported physical activity levels upon migration including perceptions of health and physical activity; social, cultural and religious differences relating to acceptability of physical activity participation; and language, financial and environmental barriers to accessibility of physical activity. The effects of these correlates were not uniform across all groups or even necessarily within the same CALD community. Consultation with CALD communities should be the forefront of future initiatives targeting community perceptions, acceptability and access to improve physical activity participation.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank librarian Ms Helen Wilding for assistance with the search strategy for this scoping review. This review was based on published qualitative literature and did not involve the participation of study subjects. Therefore no IRB or ethics committee approval was required.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Addo, I. Y., L. Brener, A. D. Asante, and J. de Wit. 2019. “Determinants of Post-Migration Changes in Dietary and Physical Activity Behaviours and Implications for Health Promotion: Evidence From Australian Residents of Sub-Saharan African Ancestry.” Health Promotion Journal of Australia 30 (Suppl. 1): 62–71. doi:10.1002/hpja.233

- Arksey, H., and L. O’Malley. 2005. “Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8 (1): 19–32. doi:10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2006. Migrants and Participation in Sport and Physical Activity. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2021. “Migration, Australia.” https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/migration-australia/2019-20.

- Bandura, A. 2004. “Health Promotion by Social Cognitive Means.” Health Education & Behavior 31: 143–164. doi:10.1177/1090198104263660

- Barnett, D. W., A. Barnett, A. Nathan, J. Van Cauwenberg, and E. Cerin. 2017. “Built Environmental Correlates of Older Adults’ Total Physical Activity and Walking: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” The international Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 14 (1): 103. doi:10.1186/s12966-017-0558-z.

- Ben, J., A. Elias, A. Issaka, M. Truong, K. Dunn, R. Sharples, C. McGarty, et al. 2022. “Racism in Australia: A Protocol for a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Systematic Reviews 11 (1): 47. doi:10.1186/s13643-022-01919-2.

- Briggs, A. M., J. G. Persaud, M. L. Deverell, S. Bunzli, B. Tampin, Y. Sumi, O. Amundsen, et al. 2019. “Integrated Prevention and Management of Non-Communicable Diseases, Including Musculoskeletal Health: A Systematic Policy Analysis among OECD Countries.” BMJ Global Health 4 (5): e001806. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001806.

- Brown, Vicki, Alison Barr, Jan Scheurer, Anne Magnus, Belen Zapata-Diomedi, and Rebecca Bentley. 2019. “Better Transport Accessibility, Better Health: A Health Economic Impact Assessment Study for Melbourne, Australia.” International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 16 (1): 89. doi:10.1186/s12966-019-0853-y.

- Bull, F., S. Al-Ansari, S. Biddle, K. Borodulin, M. Buman, and G. Cardon. 2020. “World Health Organization 2020 Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour.” British Journal of Sports Medicine 54: 1451–1462. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2020-102955

- Caperchione, Cristina M., Gregory S. Kolt, and W. Kerry Mummery. 2009. “Physical Activity in Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Migrant Groups to Western Society.” Sports Medicine 39 (3): 167–177. doi:10.2165/00007256-200939030-00001.

- Caperchione, C. M., G. S. Kolt, and W. K. Mummery. 2013. “Examining Physical Activity Service Provision to Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD) Communities in Australia: A Qualitative Evaluation.” PLoS One 8 (4): e62777. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0062777

- Caperchione, C. M., G. S. Kolt, R. Tennent, and W. K. Mummery. 2011. “Physical Activity Behaviours of Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD) Women Living in Australia: A Qualitative Study of Socio-Cultural Influences.” BMC Public Health 11: 26. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-11-26

- Caperchoine, C., W. K. Mummery, and K. Joyner. 2009. “Addressing the Challenges, Barriers, and Enablers to Physical Activity Participation in Priority Women’s Groups.” Journal of Physical Activity & Health 6 (5): 589–596. doi:10.1123/jpah.6.5.589

- Caspersen, C., K. Powell, and G. Christenson. 1985. “Physical Activity, Exercise, and Physical Fitness: Definitions and Distinctions for Health-Related Research.” Public Health Reports 100: 126–131.

- Cerin, E., A. Nathan, W. K. Choi, W. Ngan, S. Yin, L. Thornton, and A. Barnett. 2019. “Built and Social Environmental Factors Influencing Healthy Behaviours in Older Chinese Immigrants to Australia: A Qualitative Study.” International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition & Physical Activity 16 (1): 116. doi:10.1186/s12966-019-0885-3

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. 2022. “CASP Qualitative studies Checklist.” Accessed 3 February 2022. https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/.

- Das, Pamela, and Richard Horton. 2016. “Physical Activity – Time to Take it Seriously and Regularly.” The Lancet 388 (10051): 1254–1255. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31070-4.

- Dassanayake, Jayantha, Shyamali C. Dharmage, Lyle Gurrin, Vijaya Sundararajan, and Warren R. Payne. 2011. “Are Australian Immigrants at a Risk of Being Physically Inactive?” International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 8 (1): 53. doi:10.1186/1479-5868-8-53.

- Davidson, P. M., J. Daly, K. Hancock, and D. Jackson. 2003. “Australian Women and Heart Disease: Trends, Epidemiological Perspectives and the Need for a Culturally Competent Research Agenda.” Contemporary Nurse 16 (1-2): 62–73. doi:10.5172/conu.16.1-2.62.

- Ding, D., A. Ramirez Varela, A. E. Bauman, U. Ekelund, I. M. Lee, G. Heath, P. T. Katzmarzyk, R. Reis, and M. Pratt. 2020. “Towards Better Evidence-Informed Global Action: Lessons Learnt from the Lancet Series and Recent Developments in Physical Activity and Public Health.” British Journal of Sports Medicine 54 (8): 462–468. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2019-101001.

- El Masri, A., G. Kolt, and E. George. 2021. “The Perceptions, Barriers and Enablers to Physical Activity and Minimising Sedentary Behaviour Among Arab-Australian Adults Aged 35-64 Years.” Health Promotion Journal of Australia 32 (2): 312–321. doi:10.1002/hpja.345

- El Masri, A., G. Kolt, and E. George. 2022. “Physical Activity Interventions Among Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Populations: A Systematic Review.” Ethnicity & Health 27 (1): 40–60. doi:10.1080/13557858.2019.1658183.

- Fernandes, S., C. M. Caperchione, L. E. Thornton, and A. Timperio. 2021. “A Qualitative Exploration of Perspectives of Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour Among Indian Migrants in Melbourne, Australia: How are They Defined and What Can We Learn?” BMC Public Health 21 (1): 2085. doi:10.1186/s12889-021-12099-4

- Fredriksson, S., S. Alley, A. Rebar, M. Hayman, C. Vandelanotte, and S. Schoeppe. 2018. “How are Different Levels of Knowledge About Physical Activity Associated with Physical Activity Behaviour in Australian Adults?” PLoS One 13 (11): e0207003. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0207003

- Gerber, Markus, Dean Barker, and Uwe Pühse. 2012. “Acculturation and Physical Activity Among Immigrants: A Systematic Review.” Journal of Public Health 20 (3): 313–341. doi:10.1007/s10389-011-0443-1.

- Gibson, Margaret A. 2001. “Immigrant Adaptation and Patterns of Acculturation.” Human Development 44 (1): 19–23. doi:10.1159/000057037.

- Guven, Cahit, and Asadul Islam. 2015. “Age at Migration, Language Proficiency, and Socioeconomic Outcomes: Evidence From Australia.” Demography 52 (2): 513–542. doi:10.1007/s13524-015-0373-6.

- Hartley, L., C. Fleay, and M. E. Tye. 2017. “Exploring Physical Activity Engagement and Barriers for Asylum Seekers in Australia Coping with Prolonged Uncertainty and no Right to Work.” Health & Social Care in the Community 25 (3): 1190–1198. doi:10.1111/hsc.12419

- Hawke, L. J., N. F. Taylor, M. M. Dowsey, P. F. M. Choong, and N. Shields. 2022. “In the Dark About Physical Activity - Exploring Patient Perceptions of Physical Activity After Elective Total Knee Joint Replacement: A Qualitative Study.” Arthritis Care Research (Hoboken) 74 (6): 965–974. doi:10.1002/acr.24718.

- Hayba, N., Y. Shi, and M. Allman-Farinelli. 2021. “Enabling Better Physical Activity and Screen Time Behaviours for Adolescents from Middle Eastern Backgrounds: Semi-Structured Interviews with Parents.” International Journal of Environmental Research & Public Health 18 (23): 03. doi:10.3390/ijerph182312787

- Henderson, S., E. Kendall, and L. See. 2011. “The Effectiveness of Culturally Appropriate Interventions to Manage or Prevent Chronic Disease in Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Communities: A Systematic Literature Review.” Health & Social Care in the Community 19 (3): 225–249. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2524.2010.00972.x.

- Holdenson, Z., L. Catanzariti, G. Phillips, and A. M. Waters. 2003. A Picture of Diabetes in Overseas-Born Australians. Canberra: AIHW.

- Hosper, Karen, Niek S. Klazinga, and Karien Stronks. 2007a. “Acculturation Does Not Necessarily Lead to Increased Physical Activity During Leisure Time: A Cross-Sectional Study Among Turkish Young People in the Netherlands.” BMC Public Health 7 (1): 230. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-7-230.

- Hosper, K., V. Nierkens, M. Nicolaou, and K. Stronks. 2007b. “Behavioural Risk Factors in Two Generations of Non-Western Migrants: Do Trends Converge Towards the Host Population?” European Journal of Epidemiology 22: 163–172. doi:10.1007/s10654-007-9104-7

- Johnson, P. A., and R. S. Fulp. 2002. “Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Coronary Heart Disease in Women: Prevention, Treatment, and Needed Interventions.” Women’s Health Issues 12 (5): 252–271. doi:10.1016/s1049-3867(02)00148-2.

- Koo, F. K. 2011. “A Case Study on the Perception of Aging and Participation in Physical Activities of Older Chinese Immigrants in Australia.” Journal of Aging & Physical Activity 19 (4): 388–417. doi:10.1123/japa.19.4.388

- Levac, Danielle, Heather Colquhoun, and Kelly K. O'Brien. 2010. “Scoping Studies: Advancing the Methodology.” Implementation Science 5 (1): 69. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-5-69.

- Lewis, Rebecca, Constanza B. Gómez Álvarez, Margaret Rayman, Susan Lanham-New, Anthony Woolf, and Ali Mobasheri. 2019. “Strategies for Optimising Musculoskeletal Health in the 21st Century.” BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 20 (1): 164. doi:10.1186/s12891-019-2510-7.

- Marquez, D. X., and E. McAuley. 2006. “Gender and Acculturation Influences on Physical Activity in Latino Adults.” Annals of Behavioral Medicine 31 (2): 138–144. doi:10.1207/s15324796abm3102_5.

- Newman, Louise, Nicholas Proctor, and Michael Dudley. 2013. “Seeking Asylum in Australia: Immigration Detention, Human Rights and Mental Health Care.” Australasian Psychiatry 21 (4): 315–320. doi:10.1177/1039856213491991.

- Nyboe, Lene, and Hans Lund. 2013. “Low Levels of Physical Activity in Patients with Severe Mental Illness.” Nordic Journal of Psychiatry 67 (1): 43–46. doi:10.3109/08039488.2012.675588.

- O’Callaghan, C., A. Tran, N. Tam, L. M. Wen, and Roxas Harris. 2021. “Promoting the Get Healthy Information and Coaching Service (GHS) in Australian-Chinese Communities: Facilitators and Barriers.” Health Promotion International 19: 19. doi:10.1093/heapro/daab129

- O’Driscoll, Téa, Lauren Kate Banting, Erika Borkoles, Rochelle Eime, and Remco Polman. 2014. “A Systematic Literature Review of Sport and Physical Activity Participation in Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD) Migrant Populations.” Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 16 (3): 515–530. doi:10.1007/s10903-013-9857-x.

- Oliver, N., D. Perkins, L. Hare, and K. Larsen. 2007. “Stories from the Past, the Reality of the Present, Taking Control of the Future – Lifestyle Changes Among Pukapuka People in the Illawarra.” Health Promotion Journal of Australia 18 (2): 105–108. doi:10.1071/HE07105

- Parliament of Victoria. 2021. “Engaging Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CALD) Communities in Parliamentary Inquiries.” Accessed 5 October 2021. https://www.parliament.vic.gov.au/publications/research-papers/download/36-research-papers/13885-engaging-culturally-and-linguistically-diverse-cald-communities-in-parliamentary-inquiries.

- Penedo, F. J., and J. R. Dahn. 2005. “Exercise and Well-Being: A Review of Mental and Physical Health Benefits Associated with Physical Activity.” Current Opinion in Psychiatry 18 (2): 189–193. doi:10.1097/00001504-200503000-00013.

- Pink, Matthew A., John W. Mahoney, and John E. Saunders. 2020. “Promoting Positive Development Among Youth from Refugee and Migrant Backgrounds: The Case of Kicking Goals Together.” Psychology of Sport & Exercise 51. doi:10.1016/j.psychsport.2020.101790.

- Priest, N., R. Perry, A. Ferdinand, M. Kelaher, and Y. Paradies. 2017. “Effects Over Time of Self-Reported Direct and Vicarious Racial Discrimination on Depressive Symptoms and Loneliness Among Australian School Students.” BMC Psychiatry 17 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1186/s12888-017-1216-3

- Reis, A. C., K. Lokpo, M. Bojanic, and S. Sperandei. 2020. “In Search of a “Vocabulary for Recreation”: Leisure-Time Physical Activity Among Humanitarian Migrants in Regional Australia.” PLoS One 15 (10): e0239747. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0239747

- Renzaho, A. M., M. McCabe, and B. Swinburn. 2012. “Intergenerational Differences in Food, Physical Activity, and Body Size Perceptions Among African Migrants.” Qualitative Health Research 22 (6): 740–754. doi:10.1177/1049732311425051

- Sharif, M., M. Truong, O. Alam, K. Dunn, J. Nelson, A. Kavanagh, Y. Paradies, and N. Priest. 2021. “The Association Between Experiences of Religious Discrimination, Social-Emotional and Sleep Outcomes Among Youth in Australia.” SSM-Population Health 15: 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100883

- Shawyer, Frances, Joanne C. Enticott, Andrew A. Block, I. Hao Cheng, and Graham N. Meadows. 2017. “The Mental Health Status of Refugees and Asylum Seekers Attending a Refugee Health Clinic Including Comparisons with a Matched Sample of Australian-Born Residents.” BMC Psychiatry 17 (1): 76. doi:10.1186/s12888-017-1239-9.

- Smith, B. J., M. Thomas, and D. Batras. 2016. “Overcoming Disparities in Organized Physical Activity: Findings From Australian Community Strategies.” Health Promotion International 31 (3): 572–581. doi:10.1093/heapro/dav042

- Torpy, Janet M., Cassio Lynm, and Richard M. Glass. 2003. “Risk Factors for Heart Disease.” JAMA 290 (7): 980. doi:10.1001/jama.290.7.860.

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. 2021. “International Migration 2020 Highlights.” https://www.un.org/en/desa/international-migration-2020-highlights.

- Van Cauwenberg, J., A. Nathan, A. Barnett, D. W. Barnett, and E. Cerin. 2018. “Relationships Between Neighbourhood Physical Environmental Attributes and Older Adults’ Leisure-Time Physical Activity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Sports Medicine 48 (7): 1635–1660. doi:10.1007/s40279-018-0917-1.

- Willcox-Pidgeon, S. M., R. C. Franklin, S. Devine, P. A. Leggat, and J. Scarr. 2021. “Reducing Inequities Among Adult Female Migrants at Higher Risk for Drowning in Australia: The Value of Swimming and Water Safety Programs.” Health Promotion Journal of Australia 32 (Suppl. 1): 49–60. doi:10.1002/hpja.407

- You, E., N. T. Lautenschlager, C. S. Wan, A. M. Y. Goh, E. Curran, T. W. H. Chong, K. J. Anstey, F. Hanna, and K. A. Ellis. 2021. “Ethnic Differences in Barriers and Enablers to Physical Activity Among Older Adults.” Frontiers in Public Health 9: 691851. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.691851