ABSTRACT

Despite a growing awareness of the importance of interprofessional teamwork in relation to patient safety, many hospital units lack effective teamwork. The aim of this study was to explore if an interprofessional teamwork intervention in a surgical ward changed the healthcare personnel’s perceptions of patient safety culture, perceptions of teamwork, and attitudes toward teamwork over 12 months. Healthcare personnel from surgical wards at two hospitals participated in a controlled quasi-experimental study. The intervention consisted of six hours of TeamSTEPPS team training and 12 months for the implementation of teamwork tools and strategies. The data collection was conducted among the healthcare personnel in the intervention group and the control group at baseline and at the end of the 12 month study period. The results within the intervention group showed that there were significantly improved scores in three of 12 patient safety culture dimensions and in three of five perceptions of teamwork dimensions after 12 months. When comparing between groups, significant differences were found in three patient safety culture measures in favor of the intervention group. The results of the study suggest that the teamwork intervention had a positive impact on patient safety culture and teamwork in the surgical ward.

Introduction

In complex hospital organizations, the quality of patient care depends upon professions working together in interprofessional teams (WHO, Citation2010). Despite a growing awareness of the importance of teamwork, many hospital units lack effective teamwork, with negative consequences for the patient (Leonard, Frankel, & Knight, Citation2012; O’connor et al., Citation2016). The complexity of surgical care, coupled with the limitations of human performance, make it critically important that healthcare personnel have efficient interprofessional teamwork (Yngman-Uhlin, Klingvall, Wilhelmsson, & Jangland, Citation2016). In this paper, the impact of a teamwork intervention in a surgical ward is studied

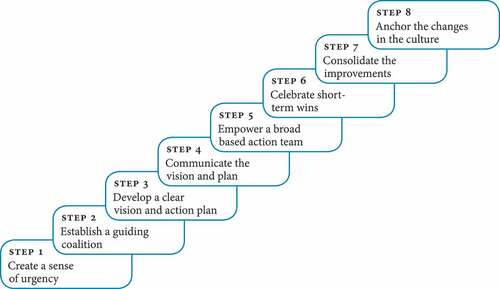

Figure 2. Kotter`s eight steps for organizational change (Kotter, Citation2012).

Background

Interprofessional teamwork involves different health professions which share a team identity, and work closely together in an integrated and interdependent manner to solve problems and deliver healthcare services (Reeves, Lewin, Espin, & Zwarenstein, Citation2010). To ensure effective teamwork, all healthcare professionals need competency in teamwork (Vincent, Burnett, & Carthey, Citation2014). Team competencies refer to the behaviors, cognitions and attitudes that individuals use to coordinate their efforts toward a shared goal (King et al., Citation2008). An effective method to improve healthcare personnel’s teamwork competencies is team training (Salas, Paige, & Rosen, Citation2013). Team training is defined as “a set of tools and methods that form an instructional strategy,” and is a methodology designed to educate team members with the competencies necessary for optimizing teamwork (Salas, Cooke, & Rosen, Citation2008, p. 1003). Reviews report that team training can positively impact teamwork, such as learning transfer measured by improved teamwork (O’Dea, O’Connor, & Keogh, Citation2014), patient safety culture (Weaver et al., Citation2013) and patient outcomes (Hughes et al., Citation2016). The majority of studies of interprofessional team training in hospitals have been conducted in special care units (Mayer et al., Citation2011; Sonesh et al., Citation2015) such as in the operating room (OR) (Armour Forse, Bramble, & McQuillan, Citation2011; Neily et al., Citation2010), where Neily et al. (Citation2010) demonstrated an 18% reduction in mortality after OR team training. While special unit teams most often are gathered around the patient, the wards have a more geographic dispersion of team members (O’Leary et al., Citation2010). Surgical wards differs from medical wards in that surgeons are less available because they are often admitted to surgery (Yngman-Uhlin et al., Citation2016). Some studies on interprofessional team training have been conducted in medical wards, but there is limited research from the context of surgical wards (Aaberg & Wiig, Citation2017; Hughes et al., Citation2016). Furthermore, since surgical wards are an area of high risk of adverse events (de Vries, Ramrattan, Smorenburg, Gouma, & Boermeester, Citation2008) this is an important context to study. There are few studies from this context that have reported on the sustainability of the impact of teamwork interventions (Rosen et al., Citation2018). A post-training implementation is of importance for the transfer of the learning and development of patient safety culture in clinical practice (Weaver, Dy, & Rosen, Citation2014).

Several team training programs have been developed, but many of them are context- or discipline-specific (Teamwork and Communication Working Group, Citation2011). The Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety (TeamSTEPPS) was chosen for this study because it is an evidence-based teamwork program (Citation2014). Previous TeamSTEPPS studies have shown promising results regarding patient safety culture (Lisbon et al., Citation2014; Thomas & Galla, Citation2013) attitudes toward teamwork (Wong, Gang, Szyld, & Mahoney, Citation2016) and perceived teamwork (Budin, Gennaro, O’Connor, & Contratti, Citation2014; Tibbs & Moss, Citation2014). However, the impact on surgical wards is uncertain.

TeamSTEPPS aims to optimize team performance in all types of healthcare teams and contexts to integrate teamwork competencies into practice (Citation2014). The overall aim of the program is to improve the patient safety and the quality of care (King et al., Citation2008; TeamSTEPPS 2.0, Citation2014). The TeamSTEPPS program is built on five key principles, which are team structure and four team competencies (Leadership, Situation Monitoring, Mutual Support and Communication (Alonso & Dunleavy, Citation2012; TeamSTEPPS 2.0, Citation2014). Each of the four team competencies has a set of tools or strategies that team members are supposed to utilize to ensure effective teamwork (King et al., Citation2008). Team decision-making is an additional team competency not included in the TeamSTEPPS program but is also pointed out as a key team competency in the literature (Reader, Citation2017; Salas, Cannon-Bowers, & Johnston, Citation2014).

The aim of this study was to explore if an interprofessional teamwork intervention in a surgical ward changed the healthcare personnel’s perceptions of patient safety culture, perceptions of teamwork, and attitudes toward teamwork over 12 months.

Methods

Research design, setting and sample

The study had a controlled quasi-experimental design (Eccles, Grimshaw, Walker, Johnston, & Pitts, Citation2003) and was carried out in two surgical wards in two different hospital trusts in Norway. The intervention group consisted of healthcare personnel (nursing assistants, physicians and registered nurses) from a combined gastrointestinal surgery and urology ward, which was selected for convenience. The control group consisted of healthcare personnel from a combined gastrointestinal surgery and ear, nose and throat ward from another hospital. The control ward was selected based on similarity to the intervention group despite being at another location, which helped to avoid the contamination effect (Polit & Beck, Citation2017) (see for profiles of the two study wards)

Table 1. Baseline profiles of the two surgical wards.

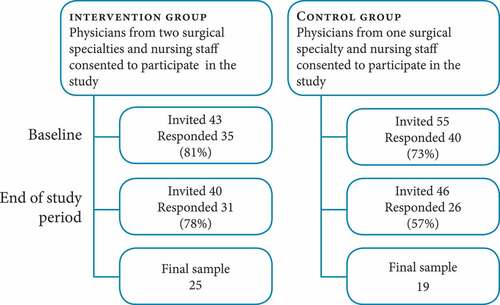

After obtaining consent from the management, all eligible healthcare personnel from the two wards were invited to participate in the study. The initial number of invited participants was 98; distributed as 43 from the intervention group and 55 from the control group ().

The intervention

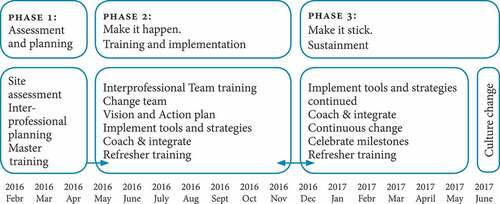

The TeamSTEPPS program (Citation2014) was translated into Norwegian by a translation agency, and the translated version was reviewed by the researchers. Kotter’s model for leading change was used to guide the implementation in a stepwise fashion (Kotter, Citation2012). Kotter (Citation2012) includes eight steps that are supposed to be followed in order to achieve success with the change work (see ). Each of these steps is organized into three phases that align with the TeamSTEPPS model of change, and the phases is described below. Further details of the intervention are described elsewhere (Aaberg, Hall-Lord, Husebo, & Ballangrud, Citation2019).

Phase 1 – set the stage and decide what to do – assessment and planning

Site assessments of the potential study sites were conducted (TeamSTEPPS 2.0, Citation2014), and the leaders of the intervention ward considered their ward`s readiness for the TeamSTEPPS program. Two of the authors (ORA, RB), two nurse leaders, and two physician leaders from the intervention ward attended master training and were certified as TeamSTEPPS instructors. The researchers and the leaders of the hospital ward jointly developed a plan for training and implementation.

Phase 2 – make it happen – training and implementation

A mandatory six-hour interprofessional team training (TeamSTEPPS fundamentals) was conducted for 41 participants during work hours over a three-week period (Aaberg & Ballangrud, Citation2017). All respondents in the intervention group participated in the six hours of initial team training. In addition to classroom training (lectures, videos and role play), the course consisted of two high-fidelity simulation sessions with a focus on communication and teamwork using one urology scenario and one gastrointestinal surgery scenario. In addition, champions from all professions and a former patient were identified and assigned as members of a Change Team. They developed a vision and an action plan based on identified patient safety issues in the ward and aligned with the organizational goals. One TeamSTEPPS tool was implemented approximately every month, and the “tool of the month” was communicated through weekly newsletters, staff meetings and posters. One of the authors (ORA) coached the implementation by giving and gathering input from site visits and e-mail communications with the leaders and the clinical nurse specialist, and as a member of the Change Team.

Phase 3 – make it stick – sustainment

The Change Team continued to meet, worked with different areas of patient safety and teamwork, and continued the implementation of tools and strategies. Milestones were celebrated along the way, and 75 minutes of classroom TeamSTEPPS refresher training was held for the nursing staff during work hours after 5 months and 11 months, and for physicians with a 20 minutes classroom refresher training after 5 months. The implemented tools and strategies became a part of the daily routines in the ward.

An overview of the intervention is illustrated in . The control group received no formal team training activities during the study period.

Measurements

In addition to demographic information about respondents (gender, age, profession and time employed in the ward), data from four questionnaires were collected to explore the impact of the intervention.

The Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture (HSOPS) is a questionnaire for assessing healthcare personnel’s perceptions of the patient safety culture within their workplace (Sorra & Dyer, Citation2010). It consists of 44 items, with 42 of the items composed into 12 dimensions. Nine dimensions aim to measure patient safety culture at the unit level: Teamwork Within the Unit, Communication Openness, Supervisor/Manager’s Expectations and Actions Promoting Patient Safety, Staffing, Organizational Learning – Continuous Improvement, Feedback and Communication About Error, Nonpunitive Response to Errors, Frequency of Events Reported and Overall Perceptions of Patient Safety in the Unit. Three dimensions are measuring patient safety culture at the hospital level: Hospital Management Support for Patient Safety, Teamwork across Units and Handoffs and Transitions. These items use a 5-point Likert response scale of “agreement” or “how often,” from 1 = “Strongly Disagree” to 5 = “Strongly Agree” or 1 = “Never” to 5 = “Always” (five choices with “neither” in the middle). In addition, there are two single items: Patient safety grade, which asks respondents to provide an overall grade on patient safety for their work unit (A = Excellent, B = Very Good, C = Acceptable, D = Poor, E = Failing), and Number of Events Reported, to indicate the number of adverse events they have reported over the past 12 months (No events, 1 to 2 events, 3 to 5 events, 6 to 10 events, 11 to 20 events or 21 events or more). A total of 18 items in the questionnaire are negatively worded (Sorra & Dyer, Citation2010). Overall Perceptions of Patient Safety, Number of Events Reported, Frequency of Events Reported, and Patient Safety Grade are defined as safety outcome measures (Jones, Skinner, Xu, Sun, & Mueller, Citation2008).

The TeamSTEPPS Teamwork Perceptions Questionnaire (T-TPQ) is a self-report questionnaire developed to measure individuals’ perceptions of group-level teamwork in the workplace and it is related to the five key components of teamwork of the TeamSTEPPS program. It has 35 items composed of responses (from 1 = “Strongly agree” to 5 = “Strongly disagree on a 5-point Likert response scale) to seven statements into each of the five dimensions: Team structure, Leadership, Mutual Support, Situational Monitoring and Communication (Keebler et al., Citation2014).

The Collaboration and Satisfaction About Care Decisions in Team Questionnaire (CSACD-T) is composed of nine items regarding collaboration and satisfaction with team decision-making about patient care. This questionnaire was developed from the nurse-physician Collaboration and Satisfaction About Care Decisions Questionnaire (CSACD) (Baggs, Citation1994). The nine-item CSACD-T questionnaire has response options on a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 7. The first six items measure attributes of collaboration in teams, with response options ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The seventh item measures the level of global collaboration, with the response options ranging from 1 (no collaboration) to 7 (complete collaboration). The last two items consider satisfaction with team decisions and have response options ranging from 1 (not satisfied) to 7 (very satisfied) (Aaberg, Hall‐Lord, Husebø, & Ballangrud, Citation2019).

The TeamSTEPPS Teamwork Attitude Questionnaire (T-TAQ) measures individuals’ general attitudes of teamwork in healthcare, and includes the five components of teamwork: Team Structure, Leadership, Mutual Support, Situational Monitoring and Communication. It has 30 items that are statements for which the individuals give their agreements on each item on a Likert scale (1 = “Strongly disagree” to 5 = “Strongly agree”). Four items are negatively worded (Baker, Amodeo, Krokos, Slonim, & Herrera, Citation2010).

The Norwegian versions of the questionnaires were used. The T-TPQ (Ballangrud, Husebø, & Hall-Lord, Citation2017), CSACD-T (Aaberg et al., Citation2019), and T-TAQ (Ballangrud, Husebø, & Hall-Lord, Citation2019) were translated into the Norwegian language in line with back translation procedures and psychometrically tested among Norwegian hospitals’ healthcare personnel, conducted by the study team (Ballangrud et al., Citation2017). The HSOPS questionnaire was translated and psychometrically tested by Olsen (Citation2008).

Data collection

The surveys were distributed through e-mail using a web-based platform (SurveyXact). The leaders in the two study groups provided e-mail addresses. An information e-mail was sent one week prior to the distribution of the surveys, and reminders were sent to those who had not responded after one week, two weeks and three weeks. The surveys were distributed at baseline (February-March 2016) and at the end of the 12 month study period (June 2017).

Data analysis

To explore the impact of the intervention, scores from respondents who had answered at both baseline and at the end of the 12 month study period were included. Negatively worded items of HSOPS and T- TAQ were reversed. The items of the questionnaires were computed according to the defined dimensions (Sorra et al., Citation2016) by adding the mean to a total score, and dividing the score by the number of items in the dimension. The data was analyzed by using SPSS version 24 (IBM, Armonk, NY). In order to test for statistically significant differences between the intervention and control group at baseline, a Mann Whitney U-test was performed for each dimension and forthe single items. The mean total score of CSACD-T and the mean scores of each dimension of the HSOPS, T-TPQ and T-TAQ were analyzed through the use of a paired t-test to check for changes from baseline to the end of the 12 month study period within both groups. To assess the magnitude of the improved dimensions, effect sizes (ES) were calculated by the mean score at the end of study period subtracted by the mean baseline score, and then divided by the baseline standard deviation (Durlak, Citation2009). We applied Cohen’s standards for effect size as follows: small effect 0.2, medium effect 0.5, and large effect 0.8 (Cohen, Citation1988). The two single items of HSOPS were analyzed with a Wilcoxon Signed Rank test within groups and with a Mann Whitney U-test between groups. Linear mixed effects models were used to compare differences between the two groups (Bolker et al., Citation2009). The models had terms for group, time, the interaction between group*time and with a person random effect. A p-value of < .05 was considered to be statistically significant for all analyzes.

Ethical considerations

The Norwegian Center for Research Data approved the study (ref. no. 46323), and approvals from the hospital administrations were given. The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki’s ethical principles for research (The World Medical Association, Citation2013). The survey included information about the aim of the study, confidentiality and voluntary participation, whereas completion of the surveys was regarded as informed consent. The study protocol was registered retrospectively with registration date 2017/05/30 and trial registration number ISRCTN13997367 (Ballangrud et al., Citation2017).

Results

The number of participants who responded to the surveys at both baseline and at the end of a 12 month study period was 44, distributed as 25 from the intervention group and 19 from the control group. Demographics of the respondents are reported in . There was one significant difference between the two samples at baseline: employment time in the ward.

Only 6% of the healthcare personnel in the control group had worked on the ward for more than 16 years, whereas 42% of the healthcare personnel in the intervention group had worked there for that long a period of time.

Table 2. Demographic information about respondents.

The baseline mean scores and comparisons between intervention group and control group are shown in . Only 4 of 25 measures were significantly different between the groups: the HSOPS measures Supervisor/Manager Expectations & Actions Promoting Patient Safety, the Patient Safety Grade, and the T-TPQ Situation Monitoring and Leadership dimensions.

Table 3. Baseline scores and comparisons between the two study groups.

Patient safety culture

Results within the intervention group showed significantly higher scores in the three dimensions, Teamwork Within Unit, Communication Openness, and Supervisor/Manager Expectations and Actions Promoting Patient Safety, at the end of the 12 month study period. There were no significant changes in any of the patient safety culture measures within the control group (). Significant differences between the two groups were found in three patient safety culture measures: Teamwork Within Unit, Overall Perceptions of Patient Safety, and Patient Safety Grade, all in favor of the intervention group ( and ).

Table 4. Patient safety culture dimension scores.

Teamwork

The results within the intervention group showed significantly higher scores after 12 months in three T-TPQ dimensions: Situation Monitoring, Mutual Support, and Communication. Within the control group there was a significantly higher score in the T-TPQ Leadership dimension after 12 months. No significant changes were found in CSACD-T and T-TAQ neither within the groups nor between the groups ().

Table 5. Patient safety culture single item scores.

Table 6. Teamwork dimension scores.

Discussion

Results from the study suggest that the TeamSTEPPS intervention had a positive impact on healthcare personnel’s perceptions of teamwork and patient safety culture in some domains. The improved patient safety and teamwork dimensions with medium to large effect size indicate a practical effect of the intervention (Sun, Pan, & Wang, Citation2010). The impact of the intervention was also demonstrated by positive differences between the groups in three patient safety culture measures, while the perceptions of the T-TPQ Leadership dimension was significantly different in favor of the control group. However, the heterogeneity of the impact also defines some areas for future research.

The improved measures of the HSOPS indicate a change in the safety culture in the intervention ward. Two outcome measures, Overall Perceptions of Patient Safety and Patient Safety Grade, differed significantly between the groups in favor of the intervention group. Together with the improved scores in Teamwork Within Unit, the results suggests a benefit to the patient safety culture due to the intervention.

Seen in light of the patient safety focus in the TeamSTEPPS intervention, the increased score in Communication Openness within the intervention group is particularly interesting. Communication Openness is about speaking up freely if seeing something that may negatively affect a patient, and it is also about questioning team members with more authority when necessary (Sorra et al., Citation2016). The hierarchy within hospital organizations is a common problem in patient safety, in which healthcare personnel have not always felt that they can speak up across professional boundaries (Leape, Citation2015). Our results are in line with Spiva et al. (Citation2014), who found increased scores in Teamwork Within Unit and Communication Openness in the two intervention wards. The results in the present study are also supported by results from other hospital contexts (Jones, Skinner, High, & Reiter-Palmon, Citation2013; Mayer et al., Citation2011; Thomas & Galla, Citation2013). Although different contexts, the results in the present study seem to be similar and may therefore be generalizable.

The positive changes within the intervention group in Supervisor/Manager Expectations and Actions Promoting Patient Safety indicate that the healthcare personnel experienced that their leaders had a focus on patient safety during the project period. Leaders have a special responsibility to facilitate a teamwork climate characterized by psychological safety (Salas et al., Citation2008). The importance of leaders in implementation studies, which also includes leadership from physicians, is well documented in the literature (Ginsburg & Tregunno, Citation2005; Rosen et al., Citation2018).

The improvement in three out of four teamwork dimensions within the intervention group suggests a benefit to teamwork due to the intervention. The teamwork tools and strategies implemented in the ward targeted these three areas of teamwork. Previous TeamSTEPPS studies that have utilized the T-TPQ have heterogeneous results. In a study from an oncology unit, improvements were found in two dimensions (Gaston, Short, Ralyea, & Casterline, Citation2016), whereas Tibbs and Moss (Citation2014) found no changes in their study from the OR. The negative result of the Leadership dimension in the present study, can be explained by a lower baseline score in the control group. This should be further studied to determine its cause and importance.

As in Spiva et al. (Citation2014) we did not find improvements in any of the teamwork attitude scores. Our results can be explained by that the respondents in both groups having favorable attitudes toward teamwork at baseline. High baseline scores may indicate a ceiling effect and leave little room for improvements, which may be due to a lack of sensitivity in the measurement tool (Polit & Beck, Citation2017). Even though attitudes is a predictor of individual`s behavior (Glasman & Albarracin, Citation2006), changes in teamwork and patient safety are dependent on many other factors. More sensitive measures may be needed to evaluate the attitudinal outcomes.

Previous studies that have utilized Kotter have reported difficulties with maintaining a sense of urgency throughout the change period, with the most challenging being to anchor the change in the culture (Baloh, Zhu, & Ward, Citation2017). In spite of that all the steps by Kotter were followed during the 12 month study period, the improvements in teamwork and patient safety of culture were relatively modest in the current study. One explanation for the results may be related to context (Ginsburg & Tregunno, Citation2005). The surgical ward is a context with a high activity level, where healthcare personnel work under very high pressure (Yngman-Uhlin et al., Citation2016), thus making it hard to find time for change work in their daily practice. Another explanation is a resistance to change, which is well known as a challenge in improvement work (Suter et al., Citation2013). Additionally, stress caused by requirements of new behaviors may serve as a barrier to change (Ginsburg & Tregunno, Citation2005). Motivational issues rooted in professional cultures and hierarchical systems (Ginsburg & Tregunno, Citation2005) may also have influenced the study results.

Realist synthesis reviews have identified underlying causal mechanisms in implementation studies and found that active engagement from physicians as the most preferable mechanism for success (Gillespie & Marshall, Citation2015). In the present study, physicians were involved from the planning phase to facilitating the team training, as well as being members of the change team. However, the physicians in surgical wards are also members of other teams, e.g., in the OR and outpatient clinics. Because the other units did not receive the intervention, the physicians could not use the new tools in those teams, which may have influenced the results of this study.

The Kotter model has been criticized for only focusing on organizational and situational change, and does not address the personal behavior that accompanies change (Clay-Williams & Braithwaite, Citation2015). According to Clay-Williams and Braithwaite (Citation2015), change is also psychological, as organizational change may impact the professional identity of the individual healthcare personnel.

Study limitations

There are limitations that may affect this study and the interpretation of the results. The two samples of healthcare personnel were small, based on convenience, and not randomized. For practical reasons randomization is not always possible in complex intervention studies (Taylor, Ukoumunne, & Warren, Citation2015). The major challenge in non-randomized studies is to be certain that the observed effect is caused by the intervention and not explained by other factors (Groenwold, Hak, & Hoes, Citation2009). An unequal distribution of participant characteristics in the groups may hinder the comparability of outcome and lead to confounding bias (Deeks et al., Citation2003). However, the only demographic variable that differed between the two groups of healthcare personnel in our study was the employment time in the ward. Since long-term employees may persist more with organizational changes, they may need more time to adapt to the changes (Cullen, Edwards, Casper, & Gue, Citation2014). The effect of participating in research, the Hawthorne effect, may have influenced the results and contributed to study bias (McCambridge, Witton, & Elbourne, Citation2014). Another possible bias is the attrition of the samples which was less of a problem in the intervention group than in the control group. In addition to drop-outs, natural exchanges in employees may explain parts of the attrition, which is a common problem with longitudinal studies in healthcare (Ployhart & Vandenberg, Citation2010). Another limitation was that only self-reported measurements were used in this study. Although self-report questionnaires are a common method for measuring teamwork in healthcare (Rosen et al., Citation2012), not all changes may be captured. For ethical reasons we did not collect demographic information about the non-responders. Furthermore, as researchers we had no control on secular changes in the study wards during the study period, and time alone may have influenced the study results (Chen, Hemming, Stevens, & Lilford, Citation2016; Craig et al., Citation2008). Because of the study limitations, caution must be taken in generalizing the results.

Conclusions

The results of the study suggest that TeamSTEPPS is a useful program in a surgical ward context for improving healthcare personnel´s scores in patient safety culture and perceptions of teamwork after a 12 month study period. The findings indicate that the TeamSTEPPS training and implementation had significance for the healthcare personnel in this surgical ward, which may give further motivation to implement TeamSTEPPS in surgical wards. There is a need for additional studies to examine whether these results have significance. Moreover, investigating factors influencing the results, and studies investigating the impact on patient outcomes, are desirable.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend our sincere appreciation to the healthcare personnel from the hospitals that participated in the study. We also wish to thank associate professor Randi Tosterud (NTNU) and senior consultant Terje Ødegården, Center for Simulation and Patient Safety (NTNU), for their valuable contributions to this project, and Jari Appelgren, statistician, at Karlstad University and Jo Røislien, professor of Medical Statistics at the University of Stavanger, for consulting on the data analysis.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Oddveig Reiersdal Aaberg

Oddveig Reiersdal Aaberg is an assistant professor working in the Nursing Bachelor’s program. During her doctoral studies at Norwegian University of Science and Technology, she had a research stay at the UCLA simulation center in Westwood, Los Angeles (US), working under Randolph Steadman’s supervision.

Randi Ballangrud

Randi Ballangrud is associate professor in Nursing Science at Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Norway. Her research is on patient safety culture, teamwork and teamwork training in hospital settings. E.mail:[email protected]

Sissel Iren Eikeland Husebø

Sissel Iren Eikeland Husebø is a professor at University of Stavanger and Department of Surgery, Stavanger University Hospital, Norway. Her research is on simulation in nursing and healthcare, clinical leadership and teamwork in hospital settings. E.mail: [email protected]

Marie Louise Hall-Lord

Marie Louise Hall-Lord is professor in Nursing Science at Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Norway and at Karlstad University, Sweden. Her research focuses on quality of care, patient safety, teamwork, health and quality of life. E.mail: [email protected]

References

- Aaberg, O. R., & Ballangrud, R. (2017). A one-day off-site classroom and simulation team training for interprofessional surgical ward teams. Paper presented at the The 23rd SESAM annual meeting, Paris, France: Centre Universitaire des Saints-Pères.

- Aaberg, O. R., Hall-Lord, M. L., Husebo, S. I. E., & Ballangrud, R. (2019). A complex teamwork intervention in a surgical ward in Norway. BMC Research Notes, 12(1), 582. doi:10.1186/s13104-019-4619-z

- Aaberg, O. R., Hall‐Lord, M. L., Husebø, S. I. E., & Ballangrud, R. (2019). Collaboration and satisfaction about care decisions in team questionnaire—Psychometric testing of the Norwegian version, and hospital healthcare personnel perceptions across hospital units. Nursing Open, 6, 642–650. doi:10.1002/nop2.2019.6.issue-2

- Aaberg, O. R., & Wiig, S. (2017, June 18–22.). Interprofessional team training in hospital wards: A literature review. Paper presented at the European Safety and Reliability Conference (ESREL), Portoroz, Slovenia.

- Alonso, A., & Dunleavy, D. (2012). Building teamwork skills in health care: The case for coordination and communication competences. In E. Salas & K. Frush (Eds.), Improving patient safety through teamwork and team training (pp. 288). New York, USA: Oxford University Press.

- Armour Forse, R., Bramble, J. D., & McQuillan, R. (2011). Team training can improve operating room performance. Surgery, 150(4), 771–778. doi:10.1016/j.surg.2011.07.076

- Baggs, J. G. (1994). Development of an instrument to measure collaboration and satisfaction about care decisions. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 20(1), 176–182. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.1994.20010176.x

- Baker, D. P., Amodeo, A. M., Krokos, K. J., Slonim, A., & Herrera, H. (2010). Assessing teamwork attitudes in healthcare: Development of the TeamSTEPPS teamwork attitudes questionnaire. Quality & Safety in Health Care, 19(6), e49. doi:10.1136/qshc.2009.036129

- Ballangrud, R., Husebø, S. E., Aase, K., Aaberg, O. R., Vifladt, A., Berg, G. V., & Hall-Lord, M. L. (2017). “Teamwork in hospitals”: A quasi-experimental study protocol applying a human factors approach. BMC Nursing, 18, 34. doi:10.1186/s12912-017-0229-z

- Ballangrud, R., Husebø, S. E., & Hall-Lord, M. L. (2017). Cross-cultural validation and psychometric testing of the Norwegian version of the TeamSTEPPS® teamwork perceptions questionnaire. BMC Health Services Research, 17(1), 799. doi:10.1186/s12913-017-2733-y

- Ballangrud, R., Husebø, S. E., & Hall-Lord, M. L. (2019). Cross-cultural validation and psychometric testing of the Norwegian version of TeamSTEPPS Teamwork Attitude Questionnaire. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 1–8. doi:10.1080/13561820.2019.1638759

- Baloh, J., Zhu, X., & Ward, M. M. (2017). Implementing team huddles in small rural hospitals: How does the Kotter model of change apply? Journal of Nursing Management. doi:10.1111/jonm.12584

- Bolker, B. M., Brooks, M. E., Clark, C. J., Geange, S. W., Poulsen, J. R., Stevens, M. H. H., & White, J.-S.-S. (2009). Generalized linear mixed models: A practical guide for ecology and evolution. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 24(3), 127–135. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2008.10.008

- Budin, W. C., Gennaro, S., O’Connor, C., & Contratti, F. (2014). Sustainability of improvements in perinatal teamwork and safety climate. Journal of Nursing Care Quality, 29(4), 363–370. doi:10.1097/ncq.0000000000000067

- Chen, Y.-F., Hemming, K., Stevens, A. J., & Lilford, R. J. (2016). Secular trends and evaluation of complex interventions: The rising tide phenomenon. BMJ Quality & Safety, 25(5), 303–310. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004372

- Clay-Williams, R., & Braithwaite, J. (2015). Reframing implementation as an organisational behaviour problem: Inside a teamwork improvement intervention. Journal of Health Organization and Management, 29(6), 670–683. doi:10.1108/JHOM-11-2013-0254

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. (2nd New edition ed.). New York, USA: Taylor & Francis Inc.

- Craig, P., Dieppe, P., Macintyre, S., Michie, S., Nazareth, I., & Petticrew, M. (2008). Developing and evaluating complex interventions: The new medical research council guidance. BMJ, 337, a1655. doi:10.1136/bmj.a1655

- Cullen, K. L., Edwards, B. D., Casper, W. C., & Gue, K. R. (2014). Employees’ adaptability and perceptions of change-related uncertainty: Implications for perceived organizational support, job satisfaction, and performance. Journal of Business and Psychology, 29(2), 269–280. doi:10.1007/s10869-013-9312-y

- de Vries, E. N., Ramrattan, M. A., Smorenburg, S. M., Gouma, D. J., & Boermeester, M. A. (2008). The incidence and nature of in-hospital adverse events: A systematic review. Quality and Safety in Health Care, 17(3), 216–223. doi:10.1136/qshc.2007.023622

- Deeks, J., Dinnes, J., D’amico, R., Sowden, A., Sakarovitch, C., Song, F., … Altman, D. (2003). Evaluating non-randomised intervention studies. Health Technology Assessment (Winchester, England), 7(27), iii–x, 1–173. doi:10.3310/hta7270

- Durlak, J. A. (2009). How to select, calculate, and interpret effect sizes. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 34(9), 917–928. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsp004

- Eccles, M., Grimshaw, J., Walker, A., Johnston, M., & Pitts, N. (2003). Research designs for studies evaluating the effectiveness of change and improvement strategies. Quality and Safety in Health Care, 12(1), 47–52. doi:10.1136/qhc.12.1.47

- Gaston, T., Short, N., Ralyea, C., & Casterline, G. (2016). Promoting patient safety: Results of a TeamSTEPPS initiative. The Journal of Nursing Administration, 46(4), 201–207. doi:10.1097/nna.0000000000000333

- Gillespie, B. M., & Marshall, A. (2015). Implementation of safety checklists in surgery: A realist synthesis of evidence. Implementation Science, 10(1), 137. doi:10.1186/s13012-015-0319-9

- Ginsburg, L., & Tregunno, D. (2005). New approaches to interprofessional education and collaborative practice: Lessons from the organizational change literature. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 19(sup1), 177–187. doi:10.1080/13561820500083105

- Glasman, L. R., & Albarracin, D. (2006). Forming attitudes that predict future behavior: A meta-analysis of the attitude-behavior relation. Psychological Bulletin, 132(5), 778. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.132.5.778

- Groenwold, R., Hak, E., & Hoes, A. (2009). Quantitative assessment of unobserved confounding is mandatory in nonrandomized intervention studies. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 62(1), 22–28. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.02.011

- Hughes, A. M., Gregory, M. E., Joseph, D. L., Sonesh, S. C., Marlow, S. L., Lacerenza, C. N., … Salas, E. (2016). Saving lives: A meta-analysis of team training in healthcare. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(9), 1266. doi:10.1037/apl0000120

- Jones, K. J., Skinner, A., Xu, L., Sun, J., & Mueller, K. (2008). The AHRQ hospital survey on patient safety culture: A tool to plan and evaluate patient safety programs. In K. Henriksen, J. B. Battles, M. A. Keyes, & M. L. Grady (Eds.), Advances in patient safety: New directions and alternative approaches (Vol. 2: Culture and redesign). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US). Retrived from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK43699/

- Jones, K. J., Skinner, A. M., High, R., & Reiter-Palmon, R. (2013). A theory-driven, longitudinal evaluation of the impact of team training on safety culture in 24 hospitals. BMJ Quality & Safety, 22(5), 394–404. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2012-000939

- Keebler, J. R., Dietz, A. S., Lazzara, E. H., Benishek, L. E., Almeida, S. A., Toor, P. A., … Salas, E. (2014). Validation of a teamwork perceptions measure to increase patient safety. BMJ Quality & Safety, 23(9), 718–726. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2013-001942

- King, H. B., Battles, J., Baker, D. P., Alonso, A., Salas, E., Webster, J., … Salisbury, M. (2008). TeamSTEPPS: Team strategies and tools to enhance performance and patient safety. In K. Henriksen, J. B. Battles, M. A. Keyes, & M. L. Grady (Eds.), Advances in patient safety: New directions and alternative approaches (Vol. 3: Performance and tools). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US). Retrived from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK43686/

- Kotter, J. P. (2012). Leading change. Boston, USA: Harvard Business Press.

- Leape, L. L. (2015). Patient safety in the era of healthcare reform. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 473(5), 1568–1573. doi:10.1007/s11999-014-3598-6

- Leonard, M., Frankel, A., & Knight, A. (2012). What facilitates or hinders team effectiveness in organizations? In E. Salas & K. Frush (Eds.), Improving patient safety through teamwork and team training (pp. 27–40). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Lisbon, D., Allin, D., Cleek, C., Roop, L., Brimacombe, M., Downes, C., & Pingleton, S. K. (2014). Improved knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors after implementation of TeamSTEPPS training in an academic emergency department: A pilot report. American Journal of Medical Quality : The Official Journal of the American College of Medical Quality. doi:10.1177/1062860614545123

- Mayer, C. M., Cluff, L., Lin, W.-T., Willis, T. S., Stafford, R. E., Williams, C., … Amoozegar, J. B. (2011). Evaluating efforts to optimize TeamSTEPPS implementation in surgical and pediatric intensive care units. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 37(8), 365–374. doi:10.1016/S1553-7250(11)37047-X

- McCambridge, J., Witton, J., & Elbourne, D. R. (2014). Systematic review of the Hawthorne effect: New concepts are needed to study research participation effects. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 67(3), 267–277. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.08.015

- Neily, J., Mills, P. D., Young-Xu, Y., Carney, B. T., West, P., Berger, D. H., … Bagian, J. P. (2010). Association between implementation of a medical team training program and surgical mortality. JAMA, 304(15), 1693–1700. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.1506

- O’connor, P., O’dea, A., Lydon, S., Offiah, G., Scott, J., Flannery, A., … Byrne, D. (2016). A mixed-methods study of the causes and impact of poor teamwork between junior doctors and nurses. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 28(3), 339–345. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzw036

- O’Dea, A., O’Connor, P., & Keogh, I. (2014). A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of crew resource management training in acute care domains. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 90(1070), 699–708. doi:10.1136/postgradmedj-2014-132800

- O’Leary, K. J., Wayne, D. B., Haviley, C., Slade, M. E., Lee, J., & Williams, M. V. (2010). Improving teamwork: Impact of structured interdisciplinary rounds on a medical teaching unit. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 25(8), 826–832. doi:10.1007/s11606-010-1345-6

- Olsen, E. (2008). Reliability and validity of the hospital survey on patient safety culture at a Norwegian hospital. In J. Øvretveit & P. Sousa (Eds.), Quality and safety improvement research: Methods and research practice from the international quality improvement research network. (pp. 173–186) Lisbon, Portugal: National Scool of Public Health.

- Ployhart, R. E., & Vandenberg, R. J. (2010). Longitudinal research: The theory, design, and analysis of change. Journal of Management, 36(1), 94–120. doi:10.1177/0149206309352110

- Polit, D. F., & Beck, C. T. (2017). Nursing research. Generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice. Philadelphia, USA: Wolters Kluwer.

- Reader, T. W. (2017). Team decision making. In E. Salas, R. Rico, & J. Passmore (Eds.), The Wiley Blackwell Handbook of the psychology of team working and collaborative processes (pp. 271–296). Oxford, UK: Wiley Blackwell.

- Reeves, S., Lewin, S., Espin, S., & Zwarenstein, M. (2010). Interprofessional teamwork for health and social care. Chichester, West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Rosen, M. A., DiazGranados, D., Dietz, A. S., Benishek, L. E., Thompson, D., Pronovost, P. J., & Weaver, S. J. (2018). Teamwork in healthcare: Key discoveries enabling safer, high-quality care. American Psychologist, 73(4), 433. doi:10.1037/amp0000298

- Rosen, M. A., Schiebel, N., Salas, E., Wu, T. S., Silvestri, S., & King, H. B. (2012). How can team performance be measured, assessed, and diagnosed? In E. Salas & K. Frush (Eds.), Improving patient safety through teamwork and team training (pp. 260). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Salas, E., Cannon-Bowers, J. A., & Johnston, J. H. (2014). How can you turn a team of experts into an expert team? Emerging training strategies. In C. Zsambok & G. Klein (Eds.), Naturalistic decision making (2nd ed., pp. 359–370). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

- Salas, E., Cooke, N. J., & Rosen, M. A. (2008). On teams, teamwork, and team performance: Discoveries and developments. Human Factors, 50(3), 540–547. doi:10.1518/001872008X288457

- Salas, E., Paige, J. T., & Rosen, M. A. (2013). Creating new realities in healthcare: The status of simulation-based training as a patient safety improvement strategy. BMJ Quality & Safesty, 22(6), 449–452. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002112

- Sonesh, S. C., Gregory, M. E., Hughes, A. M., Feitosa, J., Benishek, L. E., Verhoeven, D., … Salas, E. (2015). Team training in obstetrics: A multi-level evaluation. Families, Systems, & Health, 33(3), 250–261. doi:10.1037/fsh0000148

- Sorra, J., & Dyer, N. (2010). Multilevel psychometric properties of the AHRQ hospital survey on patient safety culture. BMC Health Services Research, 10, 199. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-10-199

- Sorra, J., Gray, L., Streagle, S., Famolaro, T., Yount, N., & Behm, J. (2016). AHRQ hospital survey on patient safety culture: User’s guide. prepared by Westat, under contract no. HHSA290201300003C. AHRQ publication no. 15-0049-EF (Replaces 04-0041) (Vol. AHRQ Publication No. 15 (16)-0049-EF. Replaces 04-0041). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, USA

- Spiva, L., Robertson, B., Delk, M. L., Patrick, S., Kimrey, M. M., Green, B., & Gallagher, E. (2014). Effectiveness of team training on fall prevention. Journal of Nursing Care Quality, 29(2), 164–173. doi:10.1097/NCQ.0b013e3182a98247

- Sun, S., Pan, W., & Wang, L. L. (2010). A comprehensive review of effect size reporting and interpreting practices in academic journals in education and psychology. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102(4), 989. doi:10.1037/a0019507

- Suter, E., Goldman, J., Martimianakis, T., Chatalalsingh, C., DeMatteo, D. J., & Reeves, S. (2013). The use of systems and organizational theories in the interprofessional field: Findings from a scoping review. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 27(1), 57–64. doi:10.3109/13561820.2012.739670

- Taylor, R. S., Ukoumunne, O. C., & Warren, F. C. (2015). How to use feasability and pilot trials to test alternative methodologies and methodological procudures prior to full scale trials. In D. A. Richards & I. R. Hallberg (Eds.), Complex interventions in healthcare - An overview of research methods (pp. 136–144). New York, NY: Rotledge.

- TeamSTEPPS 2.0. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) (2014). Official website of the Department of Health & Human Services, US. Retrieved from https://www.ahrq.gov/teamstepps/instructor/index.html

- Teamwork and Communication Working Group. 2011. Improving patient safety with effective teamwork and communication: Literature review needs assessment, evaluation of training tools and expert consultations. Edmonton, AB: Canadian Patient Safety Institute. Retrieved from www.patientsafetyinstitute.ca

- Thomas, L., & Galla, C. (2013). Building a culture of safety through team training and engagement. BMJ Quality & Safety, 22(5), 425–434. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001011

- Tibbs, S. M., & Moss, J. (2014). Promoting teamwork and surgical optimization: Combining TeamSTEPPS with a specialty team protocol. AORN Journal, 100(5), 477–488. doi:10.1016/j.aorn.2014.01.028

- Vincent, C., Burnett, S., & Carthey, J. (2014). Safety measurement and monitoring in healthcare: A framework to guide clinical teams and healthcare organisations in maintaining safety. BMJ Quality & Safety, 23(8), 670–677. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2013-002757

- Weaver, S. J., Dy, S. M., & Rosen, M. A. (2014). Team-training in healthcare: A narrative synthesis of the literature. BMJ Quality & Safety, 23(5), 359–372. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2013-001848

- Weaver, S. J., Lubomksi, L. H., Wilson, R. F., Pfoh, E. R., Martinez, K. A., & Dy, S. M. (2013). Promoting a culture of safety as a patient safety strategy: A systematic review. Annals of Internal Medicine, 158(5 Pt 2), 369–374. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-158-5-201303051-00002

- WHO. (2010). Framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice. Geneva, Switzerland. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/hrh/resources/framework_action/en/

- Wong, A. H., Gang, M., Szyld, D., & Mahoney, H. (2016). Making an “attitude adjustment”: Using a simulation-enhanced interprofessional education strategy to improve attitudes toward teamwork and communication. Simulation in Healthcare: The Journal of the Society for Simulation in Healthcare, 11(2), 117–125. doi:10.1097/sih.0000000000000133

- The World Medical Association. (2013). Declaration of Helsinki – Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects Retrieved from https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/

- Yngman-Uhlin, P., Klingvall, E., Wilhelmsson, M., & Jangland, E. (2016). Obstacles and opportunities for achieving good care on the surgical ward: Nurse and surgeon perspective. Journal of Nursing Management, 24(4), 492–499. doi:10.1111/jonm.12349