ABSTRACT

The aim of this study was to examine and construct a theoretical model of key elements that care workers perceive to have an impact on their autonomy, cohesion, and work motivation. Grounded theory was used for data collection and analysis. There were 20 participants from social welfare service, geriatric care, and women’s aid settings (women = 18, men = 2, mean age = 37.6). The analysis resulted in the following categories: (a) Being-a-Cohesive-Team; (b) Agency-Making; (c) Living-Up-to-Expectations; and (d) Developing-Support-and-Feedback. The results identified potential interactions between these factors and suggested how they influenced each other, showing how cohesion, autonomy, and motivation are interdependent and amplified.

Introduction

Researchers have distinguished two major types of work motivation (Grant & Shin, Citation2012) theories: endogenous process theories and exogenous cause theories (Katzell & Thompson, Citation1990). The former emphasizes mainly the psychological mechanisms that explain work motivation inside employees’ heads, while exogenous cause theories emphasize primarily how contextual influences on work motivation can be changed and altered. Self-determination theory (SDT) takes a hybrid perspective that places equivalent emphasis on endogenous processes and exogenous causes (Gagné & Deci, Citation2005). SDT addresses that individuals who assume there is no inherent tendency toward self-organization will focus on extrinsic means (i.e., extrinsic motivation), while endogenous growth-related capacities are prevalent in most occupations. Work motivation does not exist in a vacuum; as acknowledged early on by Hackman and Oldham (Hackman & Oldham, Citation1980), who argued that optimal design of jobs (i.e., when the interactions between managers. coworkers, and the tasks are relevant and enriching)is the most effective approach to motivate workers. Most workplaces have complex social interactions between coworkers, managers, tasks, and the organization. However, teams are constantly changing as employees come and go, thus team dynamics are in flux in various ways, which is evident for caring roles.

Early motivational researchers emphasized aspects of motivation, autonomy, and cohesion (Deci & Ryan, Citation2000; Latham, Citation2012). Although research is available for these constructs individually and in some combinations, the study of the joint role of autonomy and cohesion, associated with work motivation of care workers, such as social work and nursing care of older people, is still underdeveloped.

This in-depth empirical study was conducted to address a gap in the understanding of how different aspects of psychological mechanisms and the work context are connected in three care work settings. and to supplement the vast amount of quantitative research in the field (Toode et al., Citation2011), as it gave the participants opportunities to discuss their own understanding and experiences of cohesion, motivation, and autonomy in their own words.

Background

Research on workers in these settings is still rare (Bjerregaard et al., Citation2017), with limited investigation of care-workers’ motivation. As for research on care-worker’s attitudes, previous researchers have found that they have highly altruistic values with motivation not linked to salary (Atkinson & Lucas, Citation2013). Instead, motivation and job satisfaction for care workers mostly seem to be contingent on their affiliation with clients and colleagues, the desire to care, and the team atmosphere (Bakker, Citation2015). The focus on care workers was chosen as they collaborate in teams, which is essential in creating effective and first-rate service user care (Wei et al., Citation2020). Including workers from different contexts increased the diversity of the sample. The contexts were: in GC, in-house service users are treated; SWS provides clients with social services, while WA helps victims of domestic violence (Svensson & Westerberg, Citation2012).

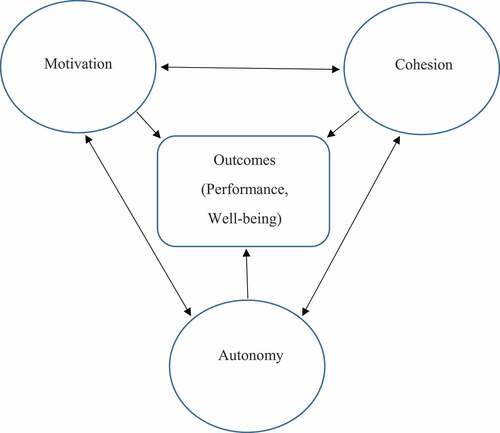

Using grounded theory (GT), the study was designed to produce a new middle-range theory, following an overview of the research carried out on cohesion, motivation, and autonomy in three care settings; geriatric care (GC), social welfare service (SWS), and women’s aid (WA). See for a relational diagram of the relationships among cohesion, autonomy, and motivation according to previous studies.

SDT (Deci & Ryan, Citation2000) distinguishes between extrinsic and intrinsic motivation, with intrinsic motivation at the core of the theory. It refers to the desire to expend efforts based on the interest in and enjoyment of an activity in and of itself (Gagné & Deci, Citation2005). SDT has received some support regarding work motivation in caring roles and volunteers. A cross-sectional study on Canadian nurses explored how job demands and resources were related to work motivational processes. They found that job demands were related to low engagement while job resources fostered optimal work motivation engagement among the nurses (Trépanier et al., Citation2015). Another cross-sectional study on volunteers in a charitable organization investigated autonomy-supportive leadership and volunteers’ motivation. The researchers found that autonomy supportive leadership was the most beneficial to volunteers’ motivation and autonomy at work (Oostlander et al., Citation2014), In a study on Swedish nurses, (Jungert et al., Citation2013) found that autonomy support between nurses was related to increased work motivation over and above the effects of managers’ autonomy support. These findings support SDT by showing that the interpersonal context, in an autonomy-supporting motivational climate, directly facilitate work motivation.

According to a survey of recent research, different theories and studies can explain different aspects of cohesion, motivation, and autonomy, but only when they are integrated is there an opportunity to explain the whole reality (Latham, Citation2012). However, there are different views on how difficult work goals should be to have the best positive effect on work motivation. Goal setting theory (GST) usually claims that difficult goals are especially beneficial to those who have a high ability (Latham, Citation2012). More recently, however, a meta-analysis found robust evidence that it is how specific the goals are that need to be emphasized (Kleingeld et al., Citation2011). According to self-efficacy theory, it is more about confidence in one’s own ability than actual ability, where high self-efficacy leads to higher set goals and increased motivation (Bandura, Citation2001). This is also in line with findings in which groups with high self-esteem set higher goals and perform better compared to groups with low self-esteem (Tang & Reynolds, Citation1993).

We believe autonomy and cohesiveness are interrelated with motivation to set relevant goals, as both autonomy and cohesion of teams are likely to have positive impacts on motivation and goal setting. Latham, (Citation2012) argued that further research should focus more on motivation in teams, as most experts agree that teamwork has the potential to provide with improved safety and value (Bakker, Citation2015; Kleingeld et al., Citation2011). Currently, there is no theoretical framework that links existing theories on motivation, autonomy, and cohesion in the care workplace (Mitchell et al., Citation2012).

Our aim was to use grounded theory (GT) to examine and construct a theoretical model of key elements that workers in care settings perceive as having an impact on their autonomy, cohesion, and work motivation. Driven by gaps in the work motivation literature, and from a GT approach, the research question was “How do cohesion, motivation, and autonomy in care settings interact?”

Method

Study design

In the current study, we adopted GT methods (Glaser & Strauss, Citation2017) based on a constructivist position (Charmaz, Citation2014). The qualitative methodology of constructivist GT was chosen because it is an exploratory approach designed to examine and conceptualize individual, social, and organizational processes, and how and why participants construct meanings and actions in specific situations (Charmaz, Citation2014). In addition, and with reference to the epistemological shortcomings of the original GT (naïve realism, pure induction, tabula rasa ideal, and assumptions of theory-free data), constructivist GT was adopted because it assumes that data are interpreted, co-constructed, and theory-laden, colored by researchers’ perspectives and situated in a particular socio-cultural context (Charmaz, Citation2014; Thornberg, Citation2012). Using sensitizing concepts as a starting point in constructivist GT (Charmaz, Citation2014), motivation, cohesion, and autonomy were adopted and treated as sensitizing concepts in the current study.

We also adopted informed GT, which is rooted in constructivist GT and suggests data sensitizing principles in using literature in GT research (Thornberg, Citation2012). In contrast to the naïve inductivism and tabula rasa researcher ideal of the original GT and Glaserian GT (Glaser, Citation1998), but in line with abductive reasoning embedded in an informed GT approach (Thornberg, Citation2012), we treated existing literature as possible multiple lenses and analytical tools that helped us focus on the attention on certain phenomena and nuances. We gathered and analyzed data with an ‘open mind’ rather than an ‘empty head.’ In particular, and in accordance with later versions of GT (Charmaz, Citation2014; Thornberg, Citation2012), we treated certain concepts from the literature (i.e., autonomy, cohesion, and motivation) as sensitizing concepts, meaning that they formed “a loose frame for looking at” our research interests (Charmaz, Citation2014, p. 31), and we used them as tentative tools for developing our ideas about processes we define in our data (Charmaz, Citation2014). We took advantage of knowing and reviewing literature in the substantive field in atheoretically agnostic, sensitive, creative, and flexible way, and as a middle ground between induction and deduction (Thornberg, Citation2012).

Participants

Twenty care workers (18 women and two men) from GC, SWS, and WA were interviewed (see ). These settings were chosen as motivation is of particular importance to create a foundation for being able to take care of others (Bakker, Citation2015). In addition, because of their different characteristics, the three settings were chosen to maximize variation. Participants in GC and SWS were paid workers, whereas participants in WA were volunteers. All SWS workers had a bachelor’s degree in social work, even if this is only required for social workers who deal with children, while the qualifications in GC and WA varied between secondary educations combined with in-house training to higher education (e.g., nursing degree). Volunteers were important to include, as volunteerism is of particular importance in current civil society and more information on the motivation of volunteers and its effects is highly warranted (Bidee et al., Citation2013). Including three different caring roles provided the opportunity to make comparisons and to investigate the transferability of the results and to explore central as well as occupational aspects. Thus, a purposeful sampling procedure was conducted; we recruited participants who shared a commitment in providing care in three specific contexts, in combination with an open sampling procedure, meaning that we sought to maximize variations in experiences and descriptions by recruiting and including participants from contrasting milieu and backgrounds (Hallberg, Citation2006) within the field of caring ‘work.’ Open sampling produced richer data and increased the analytical power of the constant comparative method in GT as it helped us to analyze similarities, differences, dimensions, and contrasts in data and our constructed codes and categories (Strauss & Corbin, Citation1990). All participants were employed in Sweden. Data was collected from 2011 to 2016. The participants were represented as follows; WA (N = 7), GC (N = 7), and SWS (N = 6). The average age was 37.6 years. Tenure varied from 0.5 to 15 years. All participants provided informed consent.

Table 1. The locations and numbers of professions/volunteers of the participants

Ethics approval for the study was granted by the Department at the researchers’ university. Participants were made aware that participation was voluntary and that data would be anonymized.

Data collection

Semi-structured interviews was chosen as the data collection method. A common interview guide (see ) was used in each interview – the participants were asked to talk about why they worked, their tasks, their relationship with their manager and colleagues, their work-related goals, challenges, and opportunities at work. As a first step, we selected and interviewed 16 participants but as a result of theoretical sampling (i.e., coding and analysis of the data that guided further data collection). To reach theoretical saturation (Charmaz, Citation2014), we recruited and interviewed four additional participants, which in total resulted in a final sample of 20 participants. The interviews (50 to 80 minutes) resulted in 175 pages of transcribed material.

Table 2. Interview guide

Analysis

GT methods were used to analyze the data. During this analysis, coding (i.e., creating codes and categories grounded in the data), constant comparison (e.g., comparing data with data, data with codes, codes with codes, data with categories), memo writing (writing down ideas about relationships between codes and other theoretical ideas that came to mind during the coding and analysis), memo sorting (comparing and sorting memos), and theoretical sampling were the main processes.

We used the coding steps of initial and focused coding described by Charmaz (Citation2014). Codes were constructed initially by comparing data segments and using analytical questions such as: What is happening in the data? What do the data suggest? What is the participant’s main concern(s)? What category does this specific datum indicate? This step involved naming words, lines, and segments of data.

The initial coding, based on interviews with a sample of 16 participants, laid the foundation for possible directions. In contrast to Glaserian and Straussian GT, constructivist GT does not require the need to identify a single core category (Charmaz, Citation2014, pp. 241–242). Acknowledging the complexity and messiness of social life, we adopted focus coding as the next coding step, meaning that we selected and used initial codes that occurred most frequently and “had more theoretical reach, direction, and centrality.” We treated them as the core of the proceeding analysis (Charmaz, Citation2014, p. 141). These so-called focused codes were compared to each other and gave a direction for the analysis (Charmaz, Citation2014). Furthermore, the categories were compared with the transcribed material to ensure that the emerging categories represented the material from the interviews. This process formed the categories. The process was dynamic, in constant movement between data, codes, and categories. The categories presented in the process were dynamic and changeable.

Based on the produced categories, and guided by theoretical sampling (Thornberg, Citation2012), four new participants were recruited for the purpose of establishing the categories that had been identified and to further investigate patterns between them. These participants were two social workers from a new social welfare service site, one nurse from a new geriatric care site, and one volunteer from a new women’s aid. Consequently, questions that more deeply focused on cohesion in teams were added. The selection of participants was strategic to get answers on the questions raised in the analysis and for closer examination of variation within categories (Thornberg, Citation2012). Thus, the new participants were recruited to conceptualize the categories further, and to reach theoretical saturation. As the categories were formed, previously collected material was analyzed until the categories were considered saturated and the relationships between the categories became clear.

Through all the steps in the analysis, notes were taken alongside the codingfor memo-writing. The notes, which consisted of reflections on the method process, were placed in a separate block in line with recommendations (Thornberg, Citation2012). These notes were a central part of the analysis enabling an increase in abstraction at an early stage when reflections on an abstract level could be performed at the beginning of the coding.

Results

The results based on the analysis of the participants’ reports of their meanings and experiences of their employment clearly showed patterns of cohesion, motivation, and autonomy. These patterns were influenced by the participants’ duration of work in the care setting. In particular, and from the participants’ perspectives, cohesion at work positively influenced their work motivation, and they considered cohesion as the most important motivational factor. Cohesion was strengthened by work motivation as it helped participants to share their joy and interest in the work as teams brought them closer together. A positive spiral between cohesion and motivation was identified in the analysis of the interview data.

A need for autonomy was expressed in participants’ desires to have more control over their work and workload. From their perspectives, autonomy had a positive impact on motivation at work; they felt more joy at work as they experienced agency and control over their work situation. Autonomy was also perceived to be supported by cohesion, characterized as an open working climate where different opinions could be expressed freely; this brought the group together. Cohesion, autonomy, and motivation therefore seemed to influence each other in many ways. According to our analysis of the participants’ perspectives, if one of these factors was strengthened, the other factors were also strengthened, but the opposite was also true.

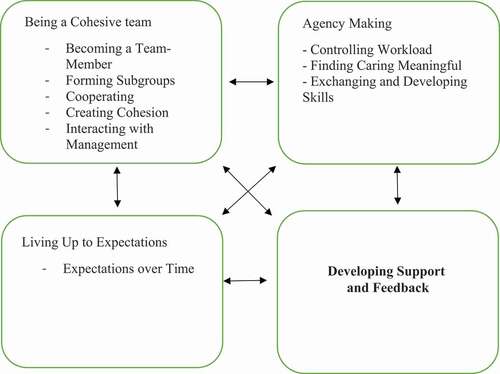

When analyzing the interview data and comparing the three caring roles, we found social processes that were recurrent in the data and in all three caring roles. The analysis originated in the following core categories: (a) Being-a-Cohesive-Team, (b) Agency-Making, (c) Living-Up-to-Expectations, and (d) Developing-Support-and-Feedback. Relationships between these main categories constitute the GT to capture the complexity of the research questions, but they may also be used as independent middle-range theories (see ).

Being a cohesive team

This category concerns the informants’ experiences when joining their team as newly employed in the workplace, but also how workers in a team experience new colleagues. Group dynamics were constantly changing and were influenced by how much time workers spent together, their opportunities for cooperation, and how they got along. This category also concerns the formation of subgroups and factors that attract group members. The presence of the manager was important for the experience of cohesion.

Becoming a team member

Employees believed that new employees were altogether positive. For example, one of the volunteers stated:

… when new coworkers arrived, we wanted to help them and make them feel a part of our group and that’s why we committed to making them feel welcome and to showing them that we really wanted them and that they would like it. (WA2, volunteer)

She emphasized the commitment that she felt to include them in their team and to help them in their new member position. New members could also be considered to vitalize the whole team. One of the nurses argued, for instance, that new team members contributed with fresh ideas and helped the established team to develop and initiate a mutual learning process in which new members and experienced members learn from each other. “ … new colleagues … come up with new ideas and you learn a lot from them and they learn a lot from us who have worked for a long time. You learn from each other … ” (GC3, site 2).

However, the treatment of new employees was not always as positive. New members could experience being ignored by the more established team members:

… they hardly even greeted me. I started in the summer, and at breakfast you start at 7 am and everyone was sitting there. They didn’t look up, they didn’t even respond to me being new. (GC6, site 2)

The results suggest that this was because the GC was a workplace with many teams. Those who had been there a long time did not always interact with new employees. That too many temporary employees could have a negative impact on relationships was highlighted as a possible contributory factor to their reactions. When new employees and those with more work experience in GC got to know each other better, relationships became stronger.

All three organizations had procedures for new workers so they would feel more secure. A form of mentorship existed in all organizations, and all new employees had a mentor. It was important to have an experienced care worker who could answer questions. There was a certain discrepancy as employees in some organizations felt secure when asking for help and when asking questions, while others expressed uncertainty and were afraid of becoming a liability. Therefore, mentorship and clarity about who new employees can turn to seem to be of great importance.

Forming subgroups

Subgroup divisions were common in all organizations. Age was a common denominator, which helped employees feel greater cohesion. In GC and SWS it was common for young people and new workers to be in one subgroup and older, more professionally experienced in another subgroup. Within WA, most volunteers were young, worker turnover was high, and there was no clear pattern of subgroups based on age. This might, at least in part, be explained by a context of volunteers without professional educational requirements, which allowed younger people such as aspirant nurses to engage as volunteers in a temporary engagement to achieve some care experience. In contrast, GC and SWS represented workplace contexts with professionally educated paid employees. Another crucial factor for the formation of subgroups in all organizations was where employees were located and how much time they spent together. It was easier to create a good relationship with the ones they met more often.

There are so many subgroups. It was obvious who sat next to whom at the morning meeting, who talked to who and who had coffee together. There were also lots of people who spent time together outside of work. You could hear them say things like “Wanna hang out after work today?” (GC7, site 3)

Although the informants expressed a sense of security and appreciation for the subgroup, they highlighted how cohesion could be improved throughout the workplace, which was desirable. These suggestions were made by informants of varying age in SWS and GC.

One day maybe you’ll get to know each other better. It might be possible because of the different ages and different kinds of people in the groups. (SWS7, site 5)

I can say that it’s a bit better when there is greater staff rotation,

… so you don’t get these very small groups … (GC7, site 3)

Cooperating

Even though most tasks were performed individually, they mostly involved some kind of cooperation consisting mainly of discussing difficult cases, giving advice and support to each other, and redistributing the workload. Such opportunities were very important to employees. In WA there was consensus on the importance of such cooperation, especially giving each other support and consultations in unclear situations. If it was not possible to work with a colleague, it was of great importance that someone was available to get support. This type of cooperation was important when workers helped each other in various tasks by providing an alternative perspective. It was also of great significance for belongingness. Spending a lot of time together was crucial to developing a deeper relationship.

The workload is sometimes insane so you may forget to look at things from a different angle, and when you go deeper into your work, you sometimes view things in a way that’s not very good, and then, being two, gives you a completely different picture. (SWS3, site 4)

Creating cohesion

Coworkers played a decisive role in the well-being of all interviewees. Relations with coworkers and support from them affected both cohesion and work motivation (e.g., “Coworkers mean a lot because if you don’t have good colleagues, nothing else matters” (GC5, site 1).

It was therefore central to the organizations to promote cohesion and relatedness, such as spending time together after work and other forms of staff-related activities. Some of the workers met outside work, which had a positive impact on cohesion at work. However, it was not desired by everyone. Some workers preferred clear boundaries between private and work life. Some workers emphasized the importance of being able to talk about work with a good colleague, and to others it was important to be able to keep things private. A balance was important between developing relatedness and cohesion and not neglecting to focus on tasks. In WA, work was often perceived as something done in the free time, which made the boundary between work and leisure less clear.

In the group I worked in before, you could talk about anything and that is definitely not the way here … though we talk a lot too. I can’t see that it’s a disadvantage now, because to me it was hard in my previous group, when everyone completely opened up, like, you knew everyone too well, so nothing was private. (GC6, site 2)

Do not want to hang out with coworkers in my spare time but get along with most of them at work. (SWS2, site 4)

We are a small group that still keep in touch even now after some are working in other places. You got this “Wow” feeling, like, such nice people, you know, we take to each other both on a professional and a personal level. (WA3, volunteer)

Interacting with management

The relationship with management was different both between and within the investigated workplaces. The biggest difference was how much time workers spent with their manager, which was important to everyone to develop a good relationship. Many workers believed that their manager was mostly absent, which made it difficult to see their manager as a group member. It was important to have an accessible manager.

She didn’t feel like my boss. She was the coordinator I turned to regarding some issues and she made important decisions, but I would not go to her if something went wrong or I had problems … because she didn’t really care, she was very busy all the time. (GC7, site 3)

The boss is responsible for too many employees to be able to see them often enough. (SWS3, site 4)

The ones who had an attending manager had a more positive view and saw the manager as belonging to the group (e.g., “You can ask the boss anything anytime” SWS5, site 4; “The boss is very good, she is present and responsive” SWS6, site 5). In sum, this core category of ‘being-a-cohesive-team’ relates to how participants linked the creation of cohesion to their own work motivation. In other words, a stronger sense of cohesion made them feel more motivated and committed to do their work.

Agency making

Common to all participants was their aspiration to help others, which was of great importance for their work motivation. Opportunities to have control over how to design the work and workloads varied to some extent between the three occupational categories and periods of employment. A pattern that appeared indicated that opportunities to manage work and make own decisions were highly motivating. Variation in tasks and autonomy were perceived as positive. Competence development was important, both in terms of external training and exchange between colleagues, which was positive for motivation and cohesion in the group.

Controlling workload

To be able to control workload and tasks was highly important. In WA such control was high for all volunteers, while it was low in SWS and GC. Lack of control had negative consequences in terms of increased stress and reduced motivation. Employees in SWS and GC expressed feelings of helplessness and they were highly controlled by rules and regulations.

We have a quite rigid schedule, which means we cannot change much on our own, I think it’s very controlled today. (GC6, site 2)

… but the regulations, and this organization, managers and so on … all this puts so much pressure on you that you’re expected to do so much, we’re expected to just take care of all continuous tasks … There’s no time to … to think about new ideas or creative thinking. (SWS2, site 4)

Finding caring meaningful

Participants had chosen their caring roles based on their interests. It was especially motivating to work with something that felt important and meaningful with the opportunity to help others. This was expressed in all roles, but most clearly in WA.

My work is not really non-profit, it’s more that I really burn for what we stand and work for. (WA5, volunteer)

Interest in the work also constituted an important component for cohesion, when shared interest in the work tasks brought the group together.

I’d say we have a very warm atmosphere, it’s always fun to meet everyone, we share important values and things we’re very interested in. (WA4, volunteer)

Exchanging and developing skills

For many participants, it was motivating to develop skills. Participants who had the opportunity to attend courses believed that they became more motivated to work.

I’m very happy to feel I develop; I get more into the work and I think it makes you more positive about your workplace when you can go on a course and get better at what you do and can respond better to clients. To feel that they invest in you, also, to get better. (SWS2, site 4)

Some of the participants reported that they had been in their organization for a long time without experiencing caring role development with perceived reduced motivation. They said they wanted more professional development in their work.

Perhaps you should develop more skills to get a deeper understanding of this … So yes, it’s boring to work when you don’t develop at work, when you don’t learn new things, when you don’t have time to think about how to improve or share knowledge with others etc. (SWS7, site 5)

According to some participants, expertise was shared between coworkers within each organization. In SWS this was standardized as cases were reviewed in groups where coworkers gave each other advice on cases. In WA, a common topic of discussion was social issues, and experiences and skills were shared. In GC, staff expressed a wish to have more time for sharing experiences, but opportunities were limited. When such opportunities appeared, it clearly improved cohesiveness.

Before, it was more divided, but now, everyone can really provide support for each other’s cases so it’s getting more coherent. It’s more open with less tension between colleagues etc. (SWS6, site 5)

We try to share the knowledge we have. There’re many who have been here a long time and are real experts. A while ago we used to have get-togethers and deal with a particular topic and the experts would share their experiences and knowledge and we’d discuss things and ask questions. (WA4, volunteer)

In sum, this core category ‘agency-making’ (controlling workload, caring for others in need, and developing skills) is about autonomy, and the participants reported that the degree of ‘agency-making’ was indeed positively associated with their work motivation. In other words, whereas a lack or poor autonomy made them feel less motivated, they considered a successful ‘agency-making’ as motivating-enhancing.

Living up to expectations

When the coworkers’ and manager’s requirements and expectations were perceived to be too high to manage, participants’ work motivation suffered, which was more commonly expressed by the workers in the SWS and GC. This is evident in the following excerpt:

Then of course, when it is tough and stressful and when the workload varies a lot it takes some time to get into the work. So my motivation is not always top notch. The motivation goes down when there is a higher load. (SWS2, 4)

To live up to the expectations was highly important to create trust and group cohesion.

Expectations over time

A pattern of how requirements and expectations changed over time were identified. New employees were expected to quickly take on a high workload and to become independent as soon as possible. Within GC and SWS, each worker would have a certain number of clients, and newly employed started off with fewer clients, but were expected to have the full load very soon.

In the beginning, they wanted you to stay, so they looked after you quite a bit. But after a few weeks, they started to give you higher and higher workloads with greater demands. (GC1, 1)

In WA, it was rather the degree of commitment that decided the expectations and workload, not the length of work experience, which was one of few differences between volunteers and employees. Generally, there were not so many reactions on how expectations changed over time, it seemed to be a natural part of the work with both positive and negative aspects. Employees could be strengthened by others’ expectations, which led to more positive relationships between employees and increased self-efficacy and motivation. Too high expectations resulted in increased stress with reduced motivation.

I feel that I assumed considerable responsibility during that time, which was appreciated by my colleagues, it made me feel like I was in charge, somehow. (WA5, volunteer)

In sum, this core category ‘living-up-to-expectations’ was found to be crucial, as too high expectations in the workplace hindered care workers’ agency-making as it decreased their sense of autonomy (lack of control) and, at the same time, decreased their work motivation. In contrast, positive and reachable expectations in the team were interpreted as increasing team cohesiveness, sense of autonomy (self-efficacy), and work motivation. This core category included the most important difference between professionals and volunteers in our data, as volunteers’ commitment decided their expectations, whereas it was the professionals’ work experience that decided their expectations.

Developing support and feedback

The extent of support and feedback at work varied across workplaces. There was a unanimous view that it was important to develop support and feedback for increased work satisfaction. Workers said they wanted more feedback compared to the current amount of feedback. Often, the manager was absent, and workers did not think s/he had sufficient insight into the daily routines and worker performance to provide adequate feedback.

You’d want even more feedback, but I think so much is going on in my job so she cannot remember everything, so it’s not possible for her to know about all of my cases, it’s unreasonable. You have to brief her about them and then she may provide feedback, but often there’s no time for that. (SWS4, site 4)

Coworkers were an important source of support and gave feedback much more frequently than the manager (e.g., “I get more support from my colleagues than from my boss” GC2, site 1). In addition, support and feedback from coworkers and management had the same effect, i.e., opportunities to develop at work and to receive confirmation on work performance. This was significant in strengthening trust in the workers’ ability, which increased work motivation and relatedness in the team (e.g., “Coworkers’ support really means a lot” SWS5, site 1).

A recurring pattern was that workers often forgot to give feedback even though there was consensus about its importance. Workers did not think they were good at providing feedback (e.g., “I don’t get many positive responses; we’re not good at providing feedback” GC4, 2). The organizations had various forms of scheduling to ensure that constructive feedback was exchanged. For example, supervision was offered in the form of case reviews and support calls where feedback was available in all sites of social welfare service and at least site one and two of geriatric care.

The importance of spontaneous feedback from colleagues and managers, preferably in direct connection with the task, was perceived as very positive. However, there was rarely time for this, which made frequently organized feedback sessions highly important for workers to develop in their caring role to increase motivation. New workers were in particular need of feedback regarding their work, but this was important to everyone, even highly experienced staff.

But we are bad at giving each other praise. I try to think about it, even if someone has done a nice job, for example, saying ‘Wow, you did a really great job helping that patient’. I try to do it, then it might turn out wrong, because I don’t know what they do, and it may be unfair if the ones who don’t talk much about what they do, don’t get as much positive feedback. (GC4, site 2)

In sum, support and feedback at work was considered important as these could help care workers in their agency-making (developing autonomy and competence) and affect their work motivation. Support and feedback were directly linked to both ‘being-a-cohesive-team’ and work motivation. It illustrates a mutual influence between autonomy, cohesiveness, and motivation.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate the key elements perceived as having an impact on autonomy, cohesion, and work motivation for workers in caregiving roles. Because no studies have previously examined the relationship between these factors from an insider perspective grounded in qualitative interviews, this study fills a gap by providing a description of the work environment closely rooted in employees’ and volunteers’ experiences of their workplace.

The most central finding in the analysis is that cohesion, autonomy, and motivation are interdependent. As the categories are largely anchored in previous research, there is scope to connect the major theories. Furthermore, the result gives the opportunity to show the dynamics of how these aspects change by including participants who have a varying degree of work experience and how cohesion, motivation, and autonomy change over time.

Surprisingly, the results did not show the importance of setting goals as a motivational driving force. This finding is in contrast to previous research such as that relating to GST (Latham, Citation2012). One interpretation is that the impact of goal setting is not so important for people who undertake care work. The clearest pattern was between the role of cohesion and work motivation. Good cohesion made the participants more satisfied and feel more competent. These results are in line with Whitehead (Citation2006) that a good work environment is one in which employees want to spend time together. Deci and Ryan (Citation2000) also emphasized cohesion as a central factor for intrinsic motivation.

Our findings suggest patterns of how subgroups are formed. The newly employed were drawn to each other as well as to more senior team-members. These results can be interpreted in the light of social identity theory (Tajfel, Citation1974) where team-members attribute their group characteristics that differentiate them from other teams. Motivation to become a team-member helped new employees identify with their team and was an asset when facing difficulties, in line with previous findings (Matschke & Fehr, Citation2015). Furthermore, subgroups were formed based on employees spending more time together, which resulted in better team cohesion. Rotation of placements in teams could reduce the formation of subgroups where employees could spend more time with diverse coworkers. There is a risk in breaking up subgroups to an excessive extent, as it complicates the possibility to get to know each other. In this way, rotation counteracts team cohesiveness and the basic human need of social belonging, and therefore work motivation (Deci & Ryan, Citation2000; Latham, Citation2012).

An interesting result was the participants' unanimous view that it could be important to break up subgroups, as subgroups could be negative for the team and relatedness in the organization as whole. This finding underlines the extent to which care workers emphasize the significance of having a cohesive climate throughout the organization. Private socializing was something that could strengthen ties between care workers. However, previous researchers have found that identity-based sub-groups are detrimental for teams, and only knowledge-based subgroups are beneficial for team-level outcomes (Meyer et al., Citation2014).

It was important to have the opportunity to decide for oneself how to carry out tasks, indicating that being autonomous plays a central role for intrinsic motivation and relatedness (Deci & Ryan, Citation2000). Subgroup classification was particularly clear in GC because of significant staff turnover and temporary employments, confirming Oostlander et al. (Citation2014), where autonomous non-governing leadership is favorable to motivation.

The ability to help others is a powerful driving force for people who undertake care work, which is consistent with previous research on work motivation (Walker et al., Citation2012), and could be conceptualized as altruistic motives, alongside intrinsic and extrinsic motives (Jungert et al., Citation2014), even though it would be considered as a form of intrinsic motivation (Deci & Ryan, Citation2000). Interestingly, the current study suggested that work motivation also strengthened perceived cohesion. This became particularly clear in WA when common interests formed the basis for cohesion and autonomy. Motivation is usually investigated as the outcome and associated with aspects of performance and well-being (Jungert et al., Citation2018). Our findings show that motivation also seems to be beneficial for autonomy and cohesion.

Competence development had a motivational effect in line with SDT (Deci & Ryan, Citation2000) and Bandura’s theories (Bandura, Citation2001). Having opportunities to develop competence and receive positive feedback were signs that the organizations believed in their employees and wanted to invest in them. The results show a pattern of competence development being prioritized for GC staff.

Competence development was also related to cohesion. Knowledge sharing took place in the form of case reviews, meetings, training courses, and especially in practical work between employees. Newly employed workers saw it as valuable to be taught by people with more experience while those who were more experienced were not equally inclined to learning from the newly employed. Being able to discuss important matters with more experienced coworkers was positive for establishing close relationships, which was an indication that the team was a secure place, which helped increase competence and cohesion in a joint process.

The importance of feedback to encourage motivation at work were identified in the results, which is in line with a meta-analysis showing that it enhances intrinsic motivation (Deci et al., Citation1999). However, feedback is only positive when it is non-controlling, which is when it is not experienced as pressure toward highly specific behaviors. This study supports the importance of this aspect, but also shows that the nature of the relationship is of great importance. Participants were more accepting of feedback when their managers were present at work, indicating that increased presence makes it possible to design feedback that is more specific and accurate in relation to the care worker’s performance. SDT primarily focused on reinforcing intrinsic motivation by feedback that increases competence and autonomy (Gagné & Deci, Citation2005), which also is confirmed in the current study. However, this study also suggests that cohesion plays a central role for the impact of feedback. When a manager was not present, feedback from coworkers was of even greater significance to participants’ motivation, supporting previous findings (Atkinson & Lucas, Citation2013). In addition, the results show the positive impact of spontaneous feedback common for workers in close work relationships. More experienced workers were more susceptible to feedback from newly employed coworkers if they had spent time together. Thus, giving and receiving feedback is important for creating cohesion, security, and motivation.

Strengths and limitations

The choice of the constructivist GT approach was appropriate given the purpose of this study was to explore care workers’ perspectives and experiences of cohesion, autonomy, and motivation. Grounding in a set of qualitative material and a step-by-step approach enabled an investigation of new ideas. Moreover, the chosen methodology was well adapted to that knowledge gap, namely to identify the key elements of workers in caring roles that were perceived to have a great impact on their cohesion and work motivation. Although GT originally was designed to investigate sociological phenomena (Glaser, Citation1998), constructivist GT focuses on participants’ meanings and perspectives (Charmaz, Citation2014), and was therefore well suited to capture psychological phenomena such as work motivation and cohesion.

Some limitations of this study should, however, be noted. Data were based on interviews (self-reports), not on direct observations. What people do and what people say they do are of course not the same. The data are vulnerable to self-impression bias, memory distortion, and threats against ecological validity. However, constructivist GT rejects a naïve realist position and emphasizes co-construction of data. In line with this position, we do not claim to offer an exact picture, but rather an interpretative portrayal of the phenomenon studied (Thornberg, Citation2012).

Moreover, we included volunteers in the study as they are of particular importance in current civil society. However, we acknowledge that volunteers differ from professionals in some respects as they give their time freely with no expectation of financial gain, and assigned without professional training requirements. Despite this, the volunteers in the current study provided care to people in need. In that respect, their caring role were similar to those of the nurses and social workers. They collaborated in teams to promote health and well-being and experienced cohesion, autonomy, and motivation in similar and interdependent ways.

Furthermore, the three small subsamples recruited from each group of care workers located in a particular area of Sweden may or may not be similar to the population of care workers with whom the readers are interested in. The core categories were represented in all investigated groups, and the differences were greater within the groups than between them, which may suggest that the results are universal for these occupations. However, there were occupational specific aspects. Further research on other occupational care groups could enhance the transferability of the results. With its roots in pragmatism, a quality requirement for GT is that the theory should be useful (practical) and changeable based on how the context changes (Charmaz, Citation2014). This makes it possible for others to use it.

Conclusion

For workers in care settings, both professionals and volunteers, cohesion, motivation, and autonomy influence each other in both positive and negative directions. The findings reflect established theories and show the complexity and importance of cohesion. Our results suggest that organizations could aim to reduce employee workloads and clarify job roles. They could also allow teams to be more autonomous and highlight that team members could interact and try to take each other’s perspectives more for increased team cohesion.

Declaration of Interest Statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by a grant from the Swedish Council for Working Life and Social Research.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Tomas Jungert

Tomas Jungert, Ph.D, is Associate Professor of Psychology at the Department of Psychology at Lund University, Sweden. His research interests are in motivation, bullying, and educational psychology. He is currently conducting research that examines factors that contribute to work and study motivation as well as processes involved in bystander rationales, reactions and actions in school bullying.

Robert Thornberg

Robert Thornberg is Professor of Education at the Department of Behavioral sciences and Learning, Linköping University, Sweden. His current research is on school bullying, especially with a focus on social and moral processes involved in bullying, bystander rationales, reactions and actions, and students’ perspectives and explanations. Other research areas include social climate and relations in school, values education, and student teachers’ and medical students’ emotionally distressing educational situations.

Louisa Lundstén

Louisa Lundstén is a licensed clinical psychologist and currently works as an organizational consultant at Previa, Malmö, Sweden. She earned her Master's degree in Psychology at Lund University, Sweden, in 2016, and has extensive experience of issues concerning the work environment and health.

References

- Atkinson, C., & Lucas, R. (2013). Worker responses to HR practice in adult social care in England. Human Resource Management Journal, 23(3), 296–312. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-8583.2012.00203.x

- Bakker, A. B. (2015). A job demands–resources approach to public service motivation. Public Administration Review, 75(5), 723–732. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12388

- Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 1–26. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532785XMEP0303_03

- Bidee, J., Vantilborgh, T., Pepermans, R., Huybrechts, G., Willems, J., Jegers, M., & Hofmans, J. (2013). Autonomous motivation stimulates volunteers’ work effort: A self-determination theory approach to volunteerism. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 24(1), 32–47. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/sl1266-012-9269-x

- Bjerregaard, K., Haslam, S. A., Mewse, A., & Morton, T. (2017). The shared experience of caring: A study of care-workers’ motivations and identifications at work. Ageing and Society, 37(1), 113–138. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X15000860

- Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory. Sage.

- Deci, E. L., Koestner, R., & Ryan, R. M. (1999). A meta-analytic review of experiments examining the effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 125(6), 627–668. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.125.6.627

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The” what” and” why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

- Gagné, M., & Deci, E. L. (2005). Self-determination theory and work motivation. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26(4), 331–362. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/job.322

- Glaser, B. G. (1998). Doing grounded theory: Issues and discussions. Sociology Press.

- Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (2017). Discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Routledge.

- Grant, A. M., & Shin, J. (2012). Work motivation: Directing, energizing, and maintaining eff ort (and research). In R. M. Ryan (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Human Motivation (pp. 505–519). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195399820.013.0028

- Hackman, J. R., & Oldham, G. R. (1980). Work redesign. Addison-Wesley.

- Hallberg, L. R. (2006). The “core category” of grounded theory: Making constant comparisons. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being, 1(3), 141–148. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17482620600858399

- Jungert, T., Alm, F., & Thornberg, R. (2014). Motives for becoming a teacher and their relations to academic engagement and dropout among student teachers. Journal of Education for Teaching, 40(2), 173–185. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2013.869971

- Jungert, T., Koestner, R. F., Houlfort, N., & Schattke, K. (2013). Distinguishing source of autonomy support in relation to workers’ motivation and self-efficacy. Journal of Social Psychology, 153(6), 651–666. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.2013.806292

- Jungert, T., Van den Broeck, A., Schreurs, B., & Osterman, U. (2018). How colleagues can support each other’s needs and motivation: An intervention on employee work motivation. Applied Psychology, 67(1), 3–29. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12110

- Katzell, R. A., & Thompson, D. E. (1990). Work motivation: Theory and practice. American Psychologist, 45(2), 144–153. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.45.2.144

- Kleingeld, A., van Mierlo, H., & Arends, L. (2011). The effect of goal setting on group performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(6), 1289–1304. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024315

- Latham, G. P. (2012). Work motivation: History, theory, research, and practice. Sage.

- Matschke, C., & Fehr, J. (2015). Internal motivation buffers the negative effect of identity incompatibility on newcomers’ social identification and well-being. Social Psychology, 46(6), 335–344. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-9335/a000250

- Meyer, B., Glenz, A., Antino, M., Rico, R., & González-Romá, V. (2014). Faultlines and subgroups: A meta-review and measurement guide. Small Group Research, 45(6), 633–670. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1046496414552195

- Mitchell, P., Wynia, M., Golden, R., McNellis, B., Okun, S., Webb, C. E., & Von Kohorn, I. (2012). Core principles & values of effective team-based healthcare. Institute of Medicine.

- Oostlander, J., Güntert, S. T., Van Schie, S., & Wehner, T. (2014). Leadership and volunteer motivation: A study using self-determination theory. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 43(5), 869–889. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764013485158

- Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research. Sage.

- Svensson, A., & Westerberg, E. (2012). Kvinnojourer i samverkan med socialtjänsten: Hur personal på kvinnojourer upplever samarbetet [Women’s aid in collaboration with the social services: How staff at women’s aid experience the collaboration] [Master’s thesis]. Högskolan Väst.

- Tajfel, H. (1974). Social identity and intergroup behaviour. Social Science Information, 13(2), 65–93. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/053901847401300204

- Tang, T. L. P., & Reynolds, D. B. (1993). Effects of self-esteem and perceived goal difficulty on goal setting, certainty, task performance, and attributions. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 4(2), 153–170. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.3920040206

- Thornberg, R. (2012). Informed grounded theory. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 56(3), 243–259. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2011.581686

- Toode, K., Routasalo, P., & Suominen, T. (2011). Work motivation of nurses: A literature review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 48(2), 246–257. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.09.013

- Trépanier, S.-G., Forest, J., Fernet, C., & Austin, S. (2015). On the psychological and motivational processes linking job characteristics to employee functioning: Insights from self-determination theory. Work and Stress, 29(3), 286–305. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2015.1074957

- Walker, J., Payne, S., Smith, P., & Jarrett, N. (2012). Psychology for nurses and the caring professions. McGraw Hill.

- Wei, H., Corbett, R. W., Ray, J., & Wei, T. L. (2020). A culture of caring: The essence of healthcare interprofessional collaboration. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 34(3), 324–331. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2019.1641476

- Whitehead, D. (2006). Workplace health promotion: The role and responsibility of health care managers. Journal of Nursing Management, 14(1), 59–68. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2934.2005.00599.x