ABSTRACT

While gender and professional status influence how decisions are made, the role played by health care professionals’ informational role self-efficacy appears as a central construct fostering participation in decision-making. The goal of this study is to contribute to a better understanding of how gender and profession affect the role of self-efficacy in sharing expertise and decision-making. Validated questionnaires were answered by a cross-sectional sample of 108 physicians and nurses working in mental health care teams. A moderated mediation analysis was performed. Results reveal that the impact of sharing knowledge on informational role self-efficacy is negative for nurses. Being a nurse negatively affects the relation between informational role self-efficacy and participating in decision-making. Informational role self-efficacy is also a strong positive predictor of participation in decision-making for male physicians but less so for female physicians.

Introduction

Healthcare organizations are complex, uncertain, fast-paced, knowledge-intensive organizations (Lin & Chang, Citation2008; Salas et al., Citation2018). In such contexts, knowledge sharing and decision-making among health care professionals are critical to the delivery of high quality health care and services, especially given they perform complex and knowledge-intensive tasks that draw upon unique knowledge and skill sets. For at least a decade, decision-making has been found to be important to collaboration and delivery of optimal health services (World Health Organization, Citation2010). Interestingly, some report that decision-making is the least frequent process in the collaborative relationship between nurses and physician (Nair et al., Citation2012).

Knowledge sharing is important because it drives innovation and performance (Mura et al., Citation2016). Knowledge sharing “involves uncertainty about which specific pieces of idiosyncratic knowledge are to be shared with whom” (Michailova & Husted, Citation2004, p. 14). Choosing what is exchanged is not a simple process. “When people solve complex unstructured problems, they bring knowledge and experience to the situation and as they interact during the process of problem solving, they create, use and share knowledge.” (Augier et al., Citation2001, p. 125). Interestingly, “an individual’s knowledge sharing is inevitably susceptible to social influences arising from other people” (Xue et al., Citation2011, p. 301).

A variety of processes occur in interactions between health care professionals that influence the effective flow of knowledge between them (Khalili et al., Citation2014). These processes do not always occur smoothly nor efficiently, due in large part to the complex belief systems among health care professionals (Bell et al., Citation2014). One particularly important belief system is self-efficacy; that is, beliefs in one’s capabilities to persist and succeed at doing something specific (Bandura, Citation1997). Self-efficacy is a universal construct (Scholz et al., Citation2002) critical in work settings as it is consistently shown to be a positive predictor of job satisfaction, job performance and team performance (Judge & Bono, Citation2001; Katz-Navon & Erez, Citation2005; Tims et al., Citation2014).

Informational role self-efficacy – the extent to which professionals believe in their capacity to communicate the elements of their expertise that are relevant to their coworkers’ performance (Chiocchio et al., Citation2016) – is a specific kind of self-efficacy. It is paramount because “members of each profession know very little of the practices, expertise, responsibilities, skills, values and theoretical perspectives of professionals in other disciplines” (San Martin Rodriguez et al., Citation2005). Communicating about expertise fosters trust MacNaughton et al., (Citation2013) and Chiocchio et al. (Citation2016) found that informational role self-efficacy is positively correlated to intra-team trust. Self-efficacy and gender have been studied but not specifically in the context of informational role self-efficacy and their joint impact on decision-making.

Other key processes influencing interactions at work originate from an individual’s gender and profession (Bell et al., Citation2014; Wilhelmsson et al., Citation2011). In terms of profession, the nurse-physician relationship is hierarchical (Nair et al., Citation2012), with nurses stereotypically functioning in deference to physicians (Hendel et al., Citation2007). Moreover, nurses typically enact caring behaviors and tend to avoid assertive behaviors allowing the physician to take a position of ascendancy in decision-making (Keenan et al., Citation1998; Nair et al., Citation2012). In terms of gender, women in male-dominated groups, such as medicine, have been found to be more susceptible to stereotypes especially if they have low self-confidence (Cohen & Swim, Citation1995). Women have also been found to have a greater tendency to self-select themselves in support roles (Davies, Citation1996).

Consequently, the goal of this study is to contribute to a better understanding of how informational role self-efficacy, gender and profession affect the relationship between knowledge-sharing and decision-making between nurses and physicians where informational role self-efficacy is a mediator and gender and profession are moderators.

Background

Health care decision-making

In complex and dynamic work settings, such as health care, decision-making is characterized by ill-defined problems, uncertain outcomes and competing goals (Orasanu & Connolly, Citation1993). In groups “collaborative decision-making occurs whenever two or more individuals contribute their diverse knowledge and expertise to the decision-making process” (Christensen & Larson, Citation1993, p. 339). Group decision-making is made more difficult by the ever-increasing degree of specialization required to provide care (Chiocchio et al., Citation2012), compounded by the fact that this specialized knowledge is distributed unevenly across members of interprofessional teams (Nembhard & Edmondson, Citation2006). Decision-making implies humans sharing information, and as such, gender and profession are fundamental elements to consider. For example, gender and profession influence roles and status. “Roles are rarely of equal status” (Hogg, Citation2001, p. 72).

Gendered expectations in health care decision-making

Gender is a social construct that refers to a system that influences behavior and defines power and status relationships between men and women often resulting in inequality (Goktan & Gupta, Citation2015). Historically, women have been regarded as having less competence than men and as a result their views in decision-making are often overlooked – many argue this persists today even if less explicit (Bell et al., Citation2014; MacMillan, Citation2012). Expectation states theory offers a partial explanation of gender inequality in decision-making processes. It asserts that gender stereotypes, societal expectations and status structures develop as a function of how people compare each other on their respective performance toward a team task (Bell et al., Citation2014; Ridgeway & Bourg, Citation2004). An individual’s perceptions of another person’s ability to accomplish a collective task can be influenced by status differences, including gender (Ridgeway & Bourg, Citation2004).

Professional status in health care decision-making

Professional status and hierarchies between professions in health care developed through a process of establishing control over and creating boundaries around a certain type of work (Evetts, Citation1999). In order to secure a place in health care delivery, the modern (female) nursing profession was established as subordinate to (male) doctors and nurses were tasked with performing the emotional and deskilled labor involved with patient care (MacMillan, Citation2012; Witz, Citation1992). This reinforced the belief that nurses were simply meant to play an auxiliary role, even in the present context where nursing roles are more complex and independent (Bell et al., Citation2014; Davies, Citation1996; MacMillan, Citation2012).

The differential professional status of physicians and nurses influences their day to day interactions in interprofessional teams, such that status may impede professional autonomy in decision-making (Papathanassoglou et al., Citation2012). Power distance perceptions between physicians and nurses in a team negatively affects psychological safety, team cohesion and team effectiveness (Appelbaum et al., Citation2020). Interestingly nurses’ self-confidence collaborating interprofessionally should increase “when they practice in an environment that supports and recognizes their professional role” (Regan et al., Citation2016, p. e59). Also, in the contemporary context, nurses are considered “bridges” of knowledge between health care professionals and patients, able to translate knowledge and foster interprofessional collaboration. Traditional hierarchical relationships can impede such knowledge sharing (Hurlock-Chorostecki et al., Citation2016).

Gender-profession interface in health care decision-making

Gender and profession are two intersecting factors affecting health care decision-making behavior of nurses and physicians. Healthcare personnel evolve in hierarchical structures that have been unequal in nature throughout history (Cohen Konrad et al., Citation2019). Recent studies report that physicians’ attitude toward physician-nurse collaboration, especially in terms of nurses’ authority, declines as physicians progress toward residency (Kempner et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, nurses tend to defer to physicians in part because of their subordinate position to the medical profession (Hoeve et al., Citation2014), but also because of power issues caused by their disproportionate female gender (Summers & Summers, Citation2009). It has been found, for example, that male nurses are afforded more opportunities to contribute to care decisions than female nurses, and their suggestions are often viewed more positively (Bell et al., Citation2014). Even if nurses have a unique perspective and develop specific knowledge in solving specific problems, they have been found to either avoid communicating this knowledge to others in the hierarchy or are otherwise ignored (Nembhard & Edmondson, Citation2006; Tucker & Edmondson, Citation2003). Power differences by gender and profession influence nurses’ own self-concept (Hoeve et al., Citation2014).

Gender can also influence the experiences within medicine. Female physicians report experiencing difficulties with receiving help from nurses and are often treated with less respect and confidence compared to their male counterparts (Gjerberg & Kjølsrød, Citation2001). Wallace (Citation2014) reports that instrumental support among physicians (such as when problem-solving is required for a task; an activity akin to decision-making) is more prevalent in male-male and female-female relationships rather than across gender.

The gender composition of the physician and nurse workforce

In Canada, 92.4% of the registered nurse/nurse practitioner workforce are women, while 7.6% are men (Canadian Institute for Health Information, Citation2015). Male nurses represent 15.9% of psychiatry/mental health positions; 9.1% of critical care positions; and 11.4% of emergency care positions (Canadian Nurses Association, Citation2012). These specialties are typically associated with higher pay and status (Evans, Citation2004). Meanwhile, male nurses only represented 3.6% of pediatric positions; 0.2% of maternity care positions; and 4.3% of community health positions (Canadian Nurses Association, Citation2012). Women represent 46.6% of family physicians and 37.5% of specialists in 2018, their proportion being highest in the younger age groups (Canadian Institute for Health Information, Citation2019). The proportion of women with higher pay and higher status positions in medicine is lower. Overall, and even more so once specialty or work setting is taken into account, women physicians are still in a male-dominated professional context.

Understanding gender and profession in decision-making: the importance of informational role self-efficacy

Status characteristics that are discernable visually, such as gender and profession (i.e., attire), play an important role initially in interactions; but “evolve over time with new information and events” (Ridgeway, Citation2001, p. 361). As such, the intricate roles that knowledge sharing, gender and profession play in decision-making might be deciphered better by understanding the impact of informational role self-efficacy. Informational role self-efficacy is the extent to which a person believes he/she can share expertise that is relevant to another person’s performance at work (Chiocchio et al., Citation2016).

Informational characteristics refer to information about one’s work experience education, and expertise (Jehn et al., Citation2008).

Role denotes the work-related responsibilities relevant to one’s job (Murphy & Jackson, Citation1999).

Self-efficacy denotes specific beliefs in one’s capabilities to produce given attainments (Bandura, Citation1997).

Informational role self-efficacy is important in situations that require interprofessional decision-making. It focusses on one’s beliefs in the ability to share problem-relevant information (Christensen & Larson, Citation1993), both of which precede the actual one-way information exchange between parties and two-way deliberation and consensus seeking that constitute decision-making (Ganz et al., Citation2016). Consistent with self-efficacy theory and empirical demonstrations (Bandura, Citation1986), if a health care professional does not believe in his/her capability to translate experience and expertise to other professionals, he/she will not engage in such one- and two-way exchanges and if he/she does and encounters challenges, he/she will not persist. Reviewing work by Berger et al. (Citation1985), Nembhard and Edmondson (Citation2006) explain that compared to individuals with high status, those with low status will tend to have low self-efficacy as well as underestimate their work contribution.

Gender as a moderator

Gender is a key moderator in self-efficacy. According to Hackett and Betz (Citation1981) self-efficacy develops from four sources of information: performance accomplishments, vicarious learning, emotional arousal, and verbal persuasion. They explain that because of male-dominated work cultures women have fewer opportunities to have performance accomplishments or are not subjected to as much verbal persuasion about their accomplishments that would activate self-efficacy beliefs. Consistent with expectation states theory, having more valued status characteristics leads to assumptions of greater competence, and more expectations for task performance (Ridgeway, Citation2001). Individuals with higher social capital are more confident in sharing knowledge and are more innovative (Mura et al., Citation2016). A socially determined hierarchy “leads to the domination of high-status individuals and self-censoring by low-status individuals” (Nembhard & Edmondson, Citation2006, p. 945). Large nation-wide studies show that self-efficacy tend to be lower for women than for men (Scholz et al., Citation2002). Unlike men, women tend to attribute successful task accomplishment to luck and unsuccessful task accomplishment to lack of ability (Hackett & Campbell, Citation1987).

Profession as a moderator

While the cornerstone of interprofessional collaboration is participation in decision-making, it is negatively influenced by professional hierarchies and silos (Khalili et al., Citation2014). It has been found in health care that people often do not recognize other team members’ expertise (Nembhard & Edmondson, Citation2006) and that “members of each profession know very little of the practices, expertise, responsibilities, skills, values and theoretical perspectives of professionals in other disciplines” (San Martin Rodriguez et al., Citation2005, p. 137). Communication must occur across professional approaches, boundaries and silos to better support patient-centered care (Zhou & Nunes, Citation2012).

Cultural differences between medicine and nursing continues to limit nurses’ abilities to participate in clinical decision-making (Khalili et al., Citation2014). Physicians, responsible for diagnosing and deciding on the treatment for patients, are trained to take charge and assume leadership in care decisions, whereas nurses are trained on how to establish relationships and work in a team (Hall, Citation2005; Khalili et al., Citation2014).

Gender, profession, and informational role self-efficacy: moderated mediation

The preceding discussion leads to three hypotheses. The first two state that gender and profession are moderators in the relationship between knowledge sharing and participation in decision-making. The third combines these hypotheses and adds that informational role self-efficacy is a mediator.

Gender will moderate the relationship between knowledge sharing and informational role self-efficacy such that the relationship will be weaker for women than for men.

Profession will moderate the relationship between informational role self-efficacy and participation in decision-making such that the relationship will be weaker for nurses than for physicians.

The mediational role of informational role self-efficacy in the relationship between knowledge sharing and participation in decision-making will be moderated by gender and profession such that informational role self-efficacy will be stronger for male physicians, followed by female physicians, male nurses and female nurses in decreasing order of magnitude.

Method

Research design and data collection

This cross-sectional study stems from a larger research project that evaluated the implementation of a mental health reform in nine health networks in Quebec (Canada). Populations varied from 64 000 in a small semi-urban network with a psychiatric department in a general hospital, to 290 000 inhabitants in an urban network with a psychiatric hospital. The prevalence of mental health disorders ranged from 11% to 12.8% (Lesage & Émond, Citation2012).

A total of 446 mental health care professionals received a personalized letter by regular postal service. Each envelop contained a consent form, a machine-scorable paper questionnaire, and a self-addressed return envelope to be sent back to the research team. A total of 315 individuals from various professional groups responded for a response rate of 71%. Of those, 108 were within the scope of this study (i.e., either physicians or nurses). Questionnaires were anonymous and confidential and kept in a locked filing cabinet.

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the ethics board of a mental health university institute for the multi-site study (i.e., all sites under its authority; number MP-IUSMD-11-037). Participants who voluntarily chose to take part in the study signed a consent form.

Measures and data analysis

Our dependent variable is participation in decision-making. It was measured by three items from Campion et al. (Citation1993) using a 7-point agree-disagree response format. Items for this measure (and all others) appear in . Internal consistency in the original validation study was 0.88. The mediator is informational role self-efficacy. It was assessed using a 5-item instrument by Chiocchio et al. (Citation2016). Chiocchio et al.’s validation study showed a one-dimensional factor structure with internal consistencies in various samples above 0.90. The independent variable is knowledge sharing. Using a 7-point agree-disagree response format, it was measured with 5 items adapted from Bock et al. (Citation2005). Original alpha was 0.93.

Table 1. Scales and items

Analyses were conducted with IBM SPSS™ version 25. Hypotheses were tested with a macro called PROCESS specifically programmed by Hayes (Citation2013) to perform moderated mediation analysis based on bootstrap conditional processing. This method of parameter estimation is particularly suited to analyses with small samples.

Results

The final sample consisted of 108 mental health professionals comprising 44 men and 64 women divided into 94 nurses and 14 physicians. There were proportionally more male physicians and female nurses (χ2(1) = 9.54; p ≤ 0.01). Mean age was 45.44 (SD = 9.63). Mean tenure in the profession and in the job was 9.94 (SD = 11.26) and 5.07 (SD = 9.74) years on average. shows other descriptive statistics.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics, reliability, zero-order correlations, and internal consistency (N = 108)

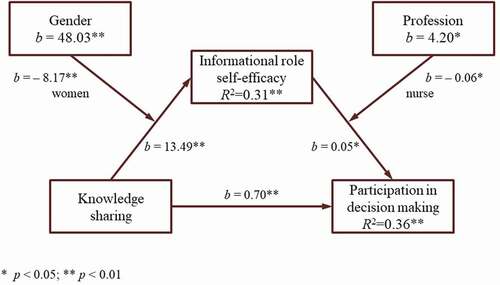

The first portion of show results that fully support hypothesis one. Unstandardized coefficients in the prediction of informational role self-efficacy for knowledge sharing and gender are positive and statistically significant. There is a statistically significant negative interaction between knowledge sharing and gender (b = −8.17; p≤ 0.01) in predicting 31% of informational role self-efficacy’s variance (F(4,103) = 14.22; p ≤ 0.01). Consistent with hypothesis one the negative unstandardized coefficient for the interaction means that being a woman negatively influences the relationship between knowledge sharing and informational role self-efficacy.

Table 3. Conditional processing analysis of participation in decision-making (N = 108)

The second portion of shows full support for hypothesis two. Unstandardized coefficients in the prediction of participation in decision-making for informational role self-efficacy and profession are positive and statistically significant. There is a statistically significant interaction between informational role self-efficacy and profession (b = −0.06; p≤ 0.05) in predicting participation in decision-making which supports hypothesis three. The negative unstandardized coefficient for the interaction means that being a nurse negatively influences the relationship between informational role self-efficacy and participation in decision-making. The full model explains 37% of participation in decision-making’s variance (R2 = 0.36; F(4,103) = 14.22; p ≤ 0.01). shows a graphical representation of the first two parts of .

The statistically significant moderated mediation is seen in the bottom portion of and in . The mediation of informational role self-efficacy on the relationship between knowledge sharing and participation in decision-making is positive for both male (b = 0.68; CI [0.12–1.06]) and female (b = 0.27; CI [0.03–0.65]) physicians. The effect of informational role self-efficacy is more than twice the size for male physicians than it is for female physicians. Results pertaining to female and male nurses are not significant. Thus there is partial support for hypothesis three.

Discussion

Interprofessional collaboration requires that professionals share their knowledge and take part in decision-making. Many studies have examined how gender and profession interact in health care service delivery in general and decision-making in particular, but results are murky. We sought to add to the extant literature and innovate by examining the mediating mechanism – informational role self-efficacy – by which sharing knowledge is transformed into participation in decision-making as a function of two statuses and moderators: gender and profession.

Our results show that gender influences the relationship between sharing knowledge and informational role self-efficacy. Specifically, being a woman appears to have a negative impact whereas the impact is positive for men. This is consistent with research that reports lower self-efficacy for women in general (Scholz et al., Citation2002). This is also consistent with expectations states theory where non-job relevant characteristics (i.e., gender) play a larger, disadvantaging role in performance expectations for women (i.e., the gender of a lesser status) than for men (Ridgeway, Citation2001). Three phenomena may be at play in explaining this result. One is attribution. Women tend to attribute successful task accomplishment to luck and unsuccessful task accomplishment to lack of ability (Hackett & Campbell, Citation1987). The other phenomenon is comparison. Women may be harsher judges of themselves compared to men (Hawks & Spade, Citation1998; Marra & Bogue, Citation2006). Perhaps this is because men are expected to be competent, task-oriented, and assertive (Bell et al., Citation2014), which provides them with more experiences that foster self-efficacy. The third is self-fulfilling expectations. Expectation states theory shows us that men and women’s knowledge and understanding of each other is formed through gender status beliefs (Ridgeway & Bourg, Citation2004). These act as self-fulfilling expectations that reinforce perceptions of inequality.

Our results suggest that profession influences the relationship between informational role self-efficacy and participation in decision-making. Specifically, being a nurse appears to have a negative impact. One possible explanation is that nurses leave the more complex decisions to physicians (Bacon et al., Citation2015). There is also the possibility that scope of practice and liability issues forces physicians in – and nurses out of – the role of final decision maker based on the incorrect assumption that physicians bear the full responsibility for decisions (Ries, Citation2016).

We found partial support for hypothesis three. We posited that the impact of informational role self-efficacy on the relationship between sharing knowledge and participating in decisions would differ as a function of gender and profession. We found support for that. But we went a step further and posited that the impact would be such that the magnitude of the impact would be highest for male physicians followed by female physicians, male nurses and lastly female nurses. Our results support this partially with male and female physicians. Our analysis of this moderated mediation suggests that informational role self-efficacy plays an important part in how knowledge sharing leads to participation in decision-making for male physicians, and much less so for female physicians.

Limitations

This study has five key limitations. First, our data stems from a relatively small sample of nurses and (especially) physicians working in mental health. The context of mental health care differs from other health care contexts. Second, this study was cross sectional so care must be taken when considering cause and effect relationships. Also, nurses and physicians’ teams were not taken into consideration as this was an individual-level study. Fourth, race was not taken into consideration. Studies conducted in college settings found that academic self-efficacy is lower in minority groups (Wang & Castañeda-Sound, Citation2008). Finally, variables were slightly negatively skewed. We ran analyses with and without transformed variables and results are the same.

Implications for research

In addition to replicating this study in other care contexts, we suggest several areas that critically explore alternative explanations to our results and suggest research worthy of pursuit. First, power distance has to do with perceived inequalities in status and power (Appelbaum et al., Citation2016; Hofstede, Citation2001). It is when coworkers consider themselves “existentially unequal” and when an organization’s hierarchy is based on this inequality (Hofstede et al., Citation2010, p. 73). We know that imbalance of power among professionals is a barrier to the intention to take part in shared decision-making (Légaré et al., Citation2013). In low power distance context, it would be less important to have high informational-role self-efficacy to make decisions. In high power distance contexts, a high dose of informational role self-efficacy might be necessary to explain the link between knowledge-sharing and decision-making.

Second, our study focused on interprofessional decision-making. It would be interesting to examine informational role self-efficacy’s impact on shared decision-making; that is, when decisions regarding the patient include the input of many professionals and the patient. In a recent study on intentions to engage in shared decision-making, differences were found across profession – with nurses showing lower intentions than physicians – but not across gender (Légaré et al., Citation2013).

Third, there is also a need for research to take multilevel factors more fully into consideration. For example, future studies should examine the impact of (team level) psychological safety on the (individual-level) relationships we tested. Psychological safety is “the shared belief that the team is safe for interpersonal risk taking” (Edmondson, Citation1999, p. 354); it “facilitates the willing contribution of ideas and actions to a shared enterprise” (Edmondson & Lei, Citation2014, p. 24). One would assume that informational role self-efficacy in psychologically safe teams would have a stronger impact on the relationship between knowledge sharing and participation in decision-making while gender and profession would have a weaker impact.

Implications for practice

While true health care decision-making requires the participation of all (D’Amour et al., Citation2008), our health care system favors physicians for decision-making (MacMillan, Citation2012). Expectation states theory predicts that if female physicians make their expertise salient to male physicians, gaps between genders and professions will lessen (Ridgeway & Bourg, Citation2004). As it stands, female physicians might be held back by their less-than-effective beliefs in their capability to share expertise, or by various audiences less able to hear their input. Collaboration and decision-making between nurses and physicians can be improved through greater knowledge of each other’s roles, knowledge and training (Maxson et al., Citation2011). Techniques such as vicarious experience and verbal persuasion have proven effective in increasing self-efficacy (Eden & Kinnar, Citation1991). Other training opportunities include addressing gender and role biases.

Conclusion

Our goal was to contribute to an understudied area of knowledge sharing and decision-making and decipher the roles of self-efficacy in sharing expertise, gender and profession. Our results contribute new explanations regarding known issues with a gendered hierarchy in health care and open new avenues useful for both research and practice.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all individuals who participated in the research. We are grateful to Jean-Marie Bamvita and Stacey McNulty for their assistance.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

François Durand

François Durand is Professor of Human Resource Management and Organizational Behavior at University of Ottawa’s Telfer School of Management. He is Montfort Research Chair in Organization of Health Services. His work focuses on the individual and organizational factors that influence collaboration in work teams and change implementation projects.

Ivy Lynn Bourgeault

Ivy Lynn Bourgeault, PhD, is a Professor in the School of Sociological and Anthropological Studies at the University of Ottawa and the University Research Chair in Gender, Diversity and the Professions. She leads the Canadian Health Workforce Network and the Empowering Women Leaders in Health initiative. Dr. Bourgeault has garnered an international reputation for her research on the health workforce, particularly from a gender lens.

Robin L. Hebert

Robin Hebert is a medical student at the University of Limerick. He previously completed a Bachelor of Science in Nursing as well as a Master of Science in Health Systems at the University of Ottawa. His research interests include scope of practice, teamwork, nursing, and primary care.

Marie-Josée Fleury

Marie-Josée Fleury is professor at the Department of Psychiatry at McGill University, and researcher at the Douglas Mental Health University Institute. Her research target key components involved in improving healthcare services and the adequacy of services to meet user needs, in the fields of mental health, addiction and homelessness. She has conducted extensive research in psychiatry epidemiology, including service use and needs assessment, as well as related to outcome studies.

References

- Appelbaum, N. P., Dow, A., Mazmanian, P. E., Jundt, D. K., & Appelbaum, E. N. (2016). The effects of power, leadership and psychological safety on resident event reporting. Medical Education, 50(3), 343–350. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12947

- Appelbaum, N. P., Lockeman, K. S., Orr, S., Huff, T. A., Hogan, C. J., Queen, B. A., & Dow, A. W. (2020). Perceived influence of power distance, psychological safety, and team cohesion on team effectiveness. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 34(1), 20–26. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2019.1633290

- Augier, M., Shariq, S. Z., & Vendelø, M. T. (2001). Understanding context: Its emergence, transformation and role in tacit knowledge sharing. Journal of Knowledge Management, 5(2), 125–137. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/13673270110393176

- Bacon, C. T., Lee, S.-Y. D., & Mark, B. (2015). The relationship between work complexity and nurses’ participation in decision making in hospitals. JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration, 45(4), 200–205. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/NNA.0000000000000185

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundation of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall.

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy – The exercise of control. W.H. Freeman and Company.

- Bell, A. V., Michalec, B., & Arenson, C. (2014). The (stalled) progress of interprofessional collaboration: The role of gender. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 28(2), 98–102. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2013.851073

- Berger, J., Fisek, M. H., Norman, R. Z., & Zelditch, M. (1985). The formation of reward expectations in status situations. In J. Berger & M. Zelditch (Eds.), Status, rewards, and influence. Jossey-Bass.

- Bock, G.-W., Zmud, R. W., Kim, Y.-G., & Lee, J.-N. (2005). Behavioral intention formation in knowledge sharing: Examining the roles of extrinsic motivators, social-psychological forces, and organizational climate. MIS Quarterly, 29(1), 87–111. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/25148669

- Campion, A. C., Medsker, G. J., & Higgs, A. C. (1993). Relations between work group characteristics and effectiveness: Implications for designing effective work groups. Personnel Psychology, 46(4), 823–850. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1993.tb01571.x

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. (2015). Regulated nurses, 2015: RN/NP data tables. Canadian Institute for Health Information. https://www.cihi.ca/en/rn_np_2015_data_tables_en.xlsx

- Canadian Institute for Health Information. (2019). Physicians in Canada, 2018.

- Canadian Nurses Association. (2012). RN workforce profile by area of responsibility – year 2011. Canadian Nurses Association. https://cna-aiic.ca/~/media/cna/files/en/2011_rn_profiles_responsibility_e.pdf

- Chiocchio, F., Lebel, P., & Dubé, J.-N. (2016). Informational role self-efficacy: A validation in interprofessional collaboration contexts involving healthcare service and project teams. BMC Health Services Research, 16(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1382-x

- Chiocchio, F., Lebel, P., Therriault, P.-Y., Boucher, A., Hass, C., Rabbat, F.-X., & Bouchard, J. (2012). Stress and performance in health care project teams. Project Management Institute.

- Christensen, C., & Larson, J. R. (1993). Collaborative medical decision making. Medical Decision Making, 13(4), 339–346. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0272989x9301300410

- Cohen Konrad, S., Fletcher, S., Hood, R., & Patel, K. (2019). Theories of power in interprofessional research–developing the field. Taylor & Francis.

- Cohen, L. L., & Swim, J. K. (1995). The differential impact of gender ratios on women and men: Tokenism, self-confidence, and expectations. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 21(9), 876–884. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167295219001

- D’Amour, D., Goulet, L., Ladadie, J.-F., San Martin-Rodriguez, L., & Pineault, R. (2008). A model of typology of collaboration between professional healthcare organizations. BMC Health Services Research, 8(1), 188. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-8-188

- Davies, C. (1996). The sociology of professions and the profession of gender. Sociology, 30(4), 661–678. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038596030004003

- Eden, D., & Kinnar, J. (1991). Modeling Galatea: Boosting self-efficacy to increase volunteering. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76(6), 770. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.76.6.770

- Edmondson, A. C. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350–385. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/2666999

- Edmondson, A. C., & Lei, Z. (2014). Psychological safety: The history, renaissance, and future of an interpersonal construct. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1(1), 23–43. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091305

- Evans, J. (2004). Men nurses: A historical and feminist perspective. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 47(3), 321–328. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03096.x

- Evetts, J. (1999). Professionalisation and professionalism: Issues for interprofessional care. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 13(2), 119–128. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/13561829909025544

- Ganz, F. D., Engelberg, R., Torres, N., & Curtis, J. R. (2016). Development of a model of interprofessional shared clinical decision making in the ICU: A mixed-methods study. Critical Care Medicine, 44(4), 680–689. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000001467

- Gjerberg, E., & Kjølsrød, L. (2001). The doctor–nurse relationship: How easy is it to be a female doctor co-operating with a female nurse? Social Science & Medicine, 52(2), 189–202. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00219-7

- Goktan, A. B., & Gupta, V. K. (2015). Sex, gender, and individual entrepreneurial orientation: Evidence from four countries. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 11(1), 95–112. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-013-0278-z

- Hackett, G., & Betz, N. E. (1981). A self-efficacy approach to the career development of women. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 18(3), 326–339. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0001-8791(81)90019-1

- Hackett, G., & Campbell, N. K. (1987). Task self-efficacy and task interest as a function of performance on a gender-neutral task. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 30(2), 203–215. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0001-8791(87)90019-4

- Hall, P. (2005). Interprofessional teamwork: Professional cultures as barriers. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 19(sup1), 188–196. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820500081745

- Hawks, B. K., & Spade, J. Z. (1998). Women and men engineering students: Anticipation of family and work roles. Journal of Engineering Education, 87(3), 249–256. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2168-9830.1998.tb00351.x

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press.

- Hendel, T., Fish, M., & Berger, O. (2007). Nurse/physician conflict management mode choices: Implications for improved collaborative practice. Nursing Administration Quarterly, 31(3), 244–253. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAQ.0000278938.57115.75

- Hoeve, Y. T., Jansen, G., & Roodbol, P. (2014). The nursing profession: Public image, self‐concept and professional identity. A discussion paper. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 70(2), 295–309. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12177

- Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions and organizations across nations. Sage publications.

- Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind. Revised and expanded (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- Hogg, M. A. (2001). Social categorization, depersonalization, and group behavior. In M. J. Hogg & R. S. Tindal (Eds.), Backwell handbook of social psychology: Group processes (pp. 56–85). Blackwell Publishing.

- Hurlock-Chorostecki, C., van Soeren, M., MacMillan, K., Sidani, S., Donald, F., & Reeves, S. (2016). A qualitative study of nurse practitioner promotion of interprofessional care across institutional settings: Perspectives from different healthcare professionals. International Journal of Nursing Sciences, 3(1), 3–10. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnss.2016.02.003

- Jehn, K. A., Bezrukova, K., & Thatcher, S. (2008). Conflict, diversity, and faultlines in workgroups. In C. K. W. De Dreu & M. J. Gelfand (Eds.), The psychology of conflict management in organizations (pp. 179–210). Laurence Erlbaum.

- Judge, T. A., & Bono, J. E. (2001). Relationship of core self-evaluations traits—self-esteem, generalized self-efficacy, locus of control, and emotional stability—with job satisfaction and job performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(1), 80. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.1.80

- Katz-Navon, T. Y., & Erez, M. (2005). When collective- and self-efficacy affect team performance. Small Group Research, 36(4), 437–465. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1046496405275233

- Keenan, G. M., Cooke, R., & Hillis, S. L. (1998). Norms and nurse management of conflicts: Keys to understanding nurse–physician collaboration. Research in Nursing & Health, 21(1), 59–72. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-240X(199802)21:1<59::AID-NUR7>3.0.CO;2-S

- Kempner, S., Brackmann, M., Kobernik, E., Skinner, B., Bollinger, M., Hammoud, M., & Morgan, H. (2020). The decline in attitudes toward physician-nurse collaboration from medical school to residency. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 34(3), 373–379. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2019.1681947

- Khalili, H., Hall, J., & DeLuca, S. (2014). Historical analysis of professionalism in western societies: Implications for interprofessional education and collaborative practice. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 28(2), 92–97. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2013.869197

- Légaré, F., Stacey, D., Brière, N., Fraser, K., Desroches, S., Dumont, S., Sales, A., Puma, C., & Aubé, D. (2013). Healthcare providers‘ intentions to engage in an interprofessional approach to shared decision-making in home care programs: A mixed methods study. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 27(3), 214–222. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2013.763777

- Lesage, A., & Émond, V. (2012). Surveillance des troubles mentaux au Québec: Prévalence, mortalité et profil d’utilisation des services. Institut national de santé publique du Québec.

- Lin, C., & Chang, S. (2008). A relational model of medical knowledge sharing and medical decision-making quality. International Journal of Technology Management, 43(4), 320–348. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1504/IJTM.2008.020554

- MacMillan, K. M. (2012). The challenge of achieving interprofessional collaboration: Should we blame Nightingale? Journal of Interprofessional Care, 26(5), 410–415. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2012.699480

- MacNaughton, K., Chreim, S., & Bourgeault, I. L. (2013). Role construction and boundaries in interprofessional primary health care teams: A qualitative study. BMC Health Services Research, 13(1), 486. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-13-486

- Marra, R. M., & Bogue, B. (2006). Women engineering students' self efficacy--a longitudinal multi-institution study. Paper presented at the Women in Engineering ProActive Network (WEPAN). https://journals.psu.edu/wepan/article/download/58479/58167

- Maxson, P. M., Dozois, E. J., Holubar, S. D., Wrobleski, D. M., Overman Dube, J. A., Klipfel, J. M., & Arnold, J. J. (2011). Enhancing nurse and physician collaboration in clinical decision making through high-fidelity interdisciplinary simulation training. Mayo Clinic Procedings, 86(1), 31–36. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4065/mcp.2010.0282

- Michailova, S., & Husted, K. (2004). Decision making in organisations hostile to knowledge sharing. Journal for East European Management Studies, 9(1), 7–19. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23280840

- Mura, M., Lettieri, E., Radaelli, G., & Spiller, N. (2016). Behavioural operations in healthcare: A knowledge sharing perspective. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 36(10), 1222–1246. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOPM-04-2015-0234

- Murphy, P. R., & Jackson, S. E. (1999). Managing role performance: Challenges for twenty-first-century organizations and their employees. In E. D. Pulakos & D. R. Ilgen (Eds.), The changing nature of performance (pp. 325–365). Jossey-Bass.

- Nair, D. M., Fitzpatrick, J. J., McNulty, R., Click, E. R., & Glembocki, M. M. (2012). Frequency of nurse–physician collaborative behaviors in an acute care hospital. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 26(2), 115–120. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2011.637647

- Nembhard, I. M., & Edmondson, A. C. (2006). Making it safe: The effects of leader inclusiveness and professional status on psychological safety and improvement efforts in health care teams. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27(7), 941–966. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/job.413

- Orasanu, J., & Connolly, T. (1993). The reinvention of decision making.

- Papathanassoglou, E. D., Karanikola, M. N., Kalafati, M., Giannakopoulou, M., Lemonidou, C., & Albarran, J. W. (2012). Professional autonomy, collaboration with physicians, and moral distress among European intensive care nurses. American Journal of Critical Care, 21(2), e41–e52. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4037/ajcc2012205

- Regan, S., Laschinger, H. K., & Wong, C. A. (2016). The influence of empowerment, authentic leadership, and professional practice environments on nurses’ perceived interprofessional collaboration. Journal of Nursing Management, 24(1), E54–E61. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.12288

- Ridgeway, C. L. (2001). Social status and group structure. In M. A. Hogg & R. S. Tindal (Eds.), Backwell handbook of social psychology: Group processes (pp. 352–375). Blackwell Publishing.

- Ridgeway, C. L., & Bourg, C. (2004). Gender as status: An expectation states theory approach. In A. H. Eagly, A. E. Beall, & R. J. Sternberg (Eds.), The psychology of gender (pp. 217–241). Guilford Press.

- Ries, N. M. (2016). Innovation in health care, innovation in law: Does the law support interprofessional collaboration in Canadian health systems. Osgoode Hall LJ, 54(1), 87.

- Salas, E., Zajac, S., & Marlow, S. L. (2018). Transforming health care one team at a time: Ten observations and the trail ahead. Group & Organization Management, 43(3), 357–381. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601118756554

- San Martin Rodriguez, L., Beaulieu, M.-D., D’Amour, D., & Ferrada-Videla, M. (2005). The determinants of successful collaboration: A review of theoretical and empirical studies. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 19(2), 132–147. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820500082677

- Scholz, U., Doña, B. G., Sud, S., & Schwarzer, R. (2002). Is general self-efficacy a universal construct? Psychometric findings from 25 countries. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 18(3), 242–251. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1027//1015-5759.18.3.242

- Summers, S., & Summers, H. (2009). Saving lives: Why the media’s portrayal of nurses puts us all at risk. Kaplan Pub.

- Tims, M., Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2014). Daily job crafting and the self-efficacy – Performance relationship. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 29(5), 490–507. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-05-2012-0148

- Tucker, A., & Edmondson, A. C. (2003). Why hospitals don’t learn from failures: Organizational and psychological dynamics that inhibit system change. California Management Review, 45(2), 55–72. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/41166165

- Wallace, J. E. (2014). Gender and supportive co-worker relations in the medical profession. Gender, Work, and Organization, 21(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12007

- Wang, -C.-C. D., & Castañeda-Sound, C. (2008). The role of generational status, self-esteem, academic self-efficacy, and perceived social support in college students’ psychological well-being. Journal of College Counseling, 11(2), 101–118. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1882.2008.tb00028.x

- Wilhelmsson, M., Ponzer, S., Dahlgren, L.-O., Timpka, T., & Faresjö, T. (2011). Are female students in general and nursing students more ready for teamwork and interprofessional collaboration in healthcare? BMC Medical Education, 11(1), 15. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-11-15

- Witz, A. (1992). Patriarchy and professions. In Professions and patriarchy (pp. 39–69). Routledge.

- World Health Organization. (2010). Framework for action on interprofessional education & collaborative practice (p. 64). Switzerland WHO Press.

- Xue, Y., Bradley, J., & Liang, H. (2011). Team climate, empowering leadership, and knowledge sharing. Journal of Knowledge Management, 15(2), 299–312. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/13673271111119709

- Zhou, L., & Nunes, M. B. (2012). Identifying knowledge sharing barriers in the collaboration of traditional and western medicine professionals in Chinese hospitals: A case study. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 44(4), 238–248. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0961000611434758