KEYWORDS:

Introduction

To help overcome the current pandemic we must embrace novel training within our health systems.

In the later months of 2019, a cluster of cases initially recognized as pneumonia was emerging in China. This was of unknown etiology until the Chinese CDC confirmed the causative agent to be a coronavirus. The disease that this virus causes is now, as we know COVID-19 and has resulted in a global pandemic. As of the 9th February 2021, there have been 106,008,943 cases and 2,316,389 deaths. It has taken its toll on healthcare workers (HCWs), with many risking their lives to provide care.

For health systems to cope both nationally and internationally, the need for on-going training has become ever more critical. It is imperative that in this context we now need to look again at the role technology can play in training healthcare workers (HCWs) to address this urgent need. This is about more than using technology to provide easy access to content. It requires a more fundamental reappraisal of how trainers use technology to provide on-going support to healthcare workers when opportunities for face-to-face training are limited. We propose the building on the approach of dynamicist thinking to address learning with technology under complexity (Bleakley, Citation2006).

Discussion

Technology that can aid in training can vary from country to country but technology-based learning must be context specific and easily adaptable by the health workers. This can range from virtual reality and simulation, customized learning management systems, all the way to simple forums via chat technology such as WhatsApp. Additionally, depending on the hospital environment and web capability, the learning environment may have to run ‘offline’. The technology must also support collaboration and in many contexts, an interprofessional approach whereby members (or students) of two or more health and/or social care professions engage in learning with, from and about each other to improve the delivery of care. Recent research has detailed the benefits of interprofessional learning in online environments, especially when time and geography are barriers (Reeves et al., Citation2017). Therefore, it is vital in this extraordinary environment that the technology-based learning has principles of interprofessional collaborative practice and pedagogy at its core. While the pragmatics of learning to teach online (including high-quality moderation strategies) are helpful (Salmon, Citation2011) in addressing this issue they alone are not enough. A stronger focus on pedagogy is required. Indeed, there is much to be learnt from health professions educators and in particular how learning theories must underpin implementations of online learning (Winters et al., Citation2018). A key point of this approach is to move away from the privileged position of theories of learning focused on the individual to those which have been developed for dynamic, team-based contexts (Bleakley, Citation2006). This is even more important in the context of COVID-19, where rapid change is inevitable and teaching is more often than not a blend of face-to-face and online. Serious questions then arise about how to provide high-quality learning, when much of the learning that needs to occur is outside of the situated context of the clinical setting. A key question is how can technology help bridge the gap between training settings, when training now includes a large online component? How do we measure a frontline team member’s professional competence in this context? One approach is to view the setting holistically as an assemblage of actors and resources that span multiple settings. Bleakley (Citation2006) underpins such as approach when he conceptualizes “dynamicist thinking”:

Dynamicist models describe learning as a naturalistic, systems-based activity occurring in time. Learning is assumed to be ‘situated’ or specific to context and is therefore studied where it actually occurs and not in the laboratory. The basic unit of analysis is taken to be a functional team operating through time.

At its core is an approach that looks at the system as a whole, not its individual components.

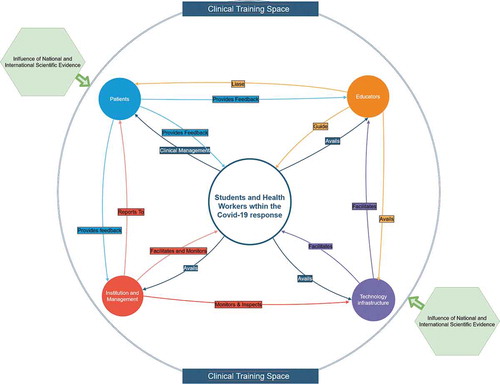

We could see this as a clinical-training space which is no longer solely the clinical setting but is widened to include the online learning space (wherever that may be located) (Winters et al., Citation2018). This distributed cognitive system becomes the focus for building relations between the team members composed of 1) students and healthworkers, 2) patients, 3) educators and 4) the institutions, some of whom will be training for entering the clinical setting (). It is interprofessional and collaborative, and from a training perspective, the unit of analysis is the clinical-training space itself, and the team includes members working in the clinical setting and those learning online. The elements of this space, including the technology infrastructure, must via physical and online means, avail and facilitate the others. Simultaneously, feedback must be received from the relevant parties, allowing for adaptation and further guidance, while adhering to international and national evidence with regard to the pandemic.

Knowledge construction in this clinical-training space is a distributed effort and so socio-cultural approaches that help analyze learning practices in complex and messy real-world settings (e.g., Activity theory; Actor-Network Theory) are appropriate to the task at hand. This moves us away from a focus on the learning of any single individual (common in cognitive approaches to technology-enhanced learning) to where the focus is on learning the happens across and within the overall system (in this case, the clinical learning space).

For these adjustments to take place there must be a call and fundamental re-alignment for health professions education and interprofessional collaborative practice to adopt this dynamicist orientated, clinical training space. We are seeing this adoption with the mobile health (mHealth) space considering social and organizational factors, similar to what this approach considers in the pandemic context (Jacob et al., Citation2020). mHealth and technology-driven medical education are not independent of each other and novel methods and adoption seen in one, influences the other, providing synergy, influencing interprofessional education and medical education as a whole (McCabe et al., Citation2020).

Conclusion

By re-evaluating how we approach learning with technology during (and after) the pandemic, we can truly aid HCWs and ultimately their patients. It is through this reconceptualization on the role of technology in training that it can be embedded in practice by becoming a focal point by which to sustain workforce capacity.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Niall Winters

Niall Winters is Professor of Education and Technology at the Department of Education, University of Oxford and a Fellow of Kellogg College. His main research interest is to design, develop and evaluate technology enhanced learning (TEL) programmes for healthcare workers in the Global South.

Kunal D Patel

Kunal D. Patel is the Medical Director at iHeed, an organization that promotes innovation in health education and content creation for health workers in low and middle-income countries. Kunal practices as a doctor in the field of travel and tropical medicine. He attained a PhD in Clinical Medicine in 2010 and has authored several papers and articles focused on global health education, health systems and innovation.

References

- Bleakley, A. (2006). Broadening conceptions of learning in medical education: The message from teamworking. Medical Education, 40(2), 150–157. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02371.x

- Jacob, C., Sanchez-Vazquez, A., & Social, I. C. (2020). Organizational, and technological factors impacting clinicians’ adoption of mobile health tools. Systematic Literature Review JMIR Mhealth Uhealth, 8(2), e15935. https://doi.org/10.2196/15935

- McCabe, C., Patel, K. D., Fletcher, S., Winters, N., Sheaf, G., Varley, J., & McCann, M. (2020). Online interprofessional education related to chronic illness for health professionals: A scoping review. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2020.1749575

- Reeves, S., Fletcher, S., McLoughlin, C., Yim, A., & Patel, K. D. (2017). Interprofessional online learning for primary healthcare: Findings from a scoping review. BMJ Open, 7, e016872. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016872

- Salmon, G. (2011). E-moderating: The key to teaching and learning. London: Routledge.

- Winters, N., Langer, L., & Geniets, A. (2018). Scoping review assessing the evidence used to support the adoption of mobile health (mHealth) technologies for the education and training of community health workers (CHWs) in low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Open, 8, e019827. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019827