ABSTRACT

Complex healthcare needs can be met through effective interprofessional collaboration. Since 2014, Swedish Child Healthcare Services (CHS) include universal team-based visits with a nurse and a physician who perform such visits at the age of 4 weeks, 6 months, 12 months, and 2.5 to 3 years, as well as targeted team-based visits to address additional needs. The aim of this study was to describe the prevalence of team-based visits in the Swedish CHS and possible associations between team-based visits and contextual factors that may affect its implementation. A national cross-sectional survey was conducted using a web-based questionnaire distributed to all reachable nurses, physicians, and psychologists (n =3,552) engaged in the CHS. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and binary and multivariate logistic regressions. The response rate was 32%. Team-based visits were reported by 82% of the respondents. For nurses and physicians, the most frequent indication was specific ages, while for psychologists it was to provide parental support. Respondents working at Family Centers were more likely to perform team-based visits in general, at 2.5 to 3 years and in case of additional needs, compared to respondents working at Child Health Centers (CHC) and other workplaces. In conclusion, team-based visits are well implemented, but the pattern differs depending on the contextual factors. Targeted team-based visits and team-based visits at the age of 2.5 to 3 years are most unequally implemented.

Introduction

Globally, the aims of child healthcare services (CHS) are to promote children’s health and development; to prevent illness; to identify problems or risks in children’s health, development, or environment; and, if needed, to initiate early interventions (National Board of Health and Welfare in Sweden, Citation2014; Oberklaid et al., Citation2013; Wettergren et al., Citation2016). In an increasingly complex society, evidence suggests that the needs of children and families can be best met with an interprofessional collaborative practice approach (Foley et al., Citation2014; Van Den Steene et al., Citation2019; WHO, Citation2010). Team-based care in family practice has been found to e.g., improve patient´s access to care, increase patient satisfaction with the healthcare received and improve patient’s overall health (Szafran et al., Citation2018). Globally, as well as in Sweden, CHS are recommended to be delivered by interprofessional teams within a framework of progressive universalism – with universal services for all children and families and with targeted services for those with additional needs (National Board of Health and Welfare in Sweden, Citation2014; Oberklaid et al., Citation2013; The Swedish Rikshandboken, Citation2019).

Background

The Swedish CHS

In Sweden, the national instructions for CHS (in use from 1991 to 2008) included regular health visits for children between 0 and 6 years of age. These checkups were provided by nurses, and physical examinations were performed by physicians at 6 weeks, 6 months, 10 months, 18 months, and 5.5 to 6 years (National Board of Health and Welfare in Sweden, Citation1991). In 2008, the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare rescinded the national instructions for the CHS, which resulted in differences between different regions (Magnusson et al., Citation2011; Tell et al., Citation2018).

In 2014, the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare published new instructions with the aim of contributing to evidence-based practice for equality and equity in the Swedish CHS. The instructions, together with a web-based national guide, constitute the current Swedish CHS program (National Board of Health and Welfare in Sweden, Citation2014; Tell et al., Citation2019; The Swedish Rikshandboken, Citation2019). The CHS program contains a combination of universal, selective, and targeted activities for all children between 0 and 6 years of age. In accordance with the program, all children should be offered team-based visits, i.e., when different professionals meet the child and his or her family in joint physical meetings. Universal team-based visits to a physician and a nurse are recommended at the age of 4 weeks, 6 months, 12 months, and 2.5 to 3 years. With the exception of the 6-month-visit, these frequencies have all changed from the previous set of recommendations. The selective and the targeted activities are recommended for all children and families who are identified as needing additional support (National Board of Health and Welfare in Sweden, Citation2014; The Swedish Rikshandboken, Citation2019).

Teams within CHS mainly consist of nurses, physicians, and psychologists. However, other professionals can participate in targeted team-based visits, depending on the specific targeted indication (National Board of Health and Welfare in Sweden, Citation2014; The Swedish Rikshandboken, Citation2019).

Interprofessional collaboration and teamwork

From an expanded and holistic perspective (Golom & Schreck, Citation2018), healthcare workers with different backgrounds who work together in multidimensional processes have the potential to improve healthcare (Careau et al., Citation2016) and deliver the highest quality of care across settings (WHO, Citation2010). Interprofessional collaboration is considered essential for effective care of individuals with complex needs (D’Amour & Oandasan, Citation2005; Drinka, Citation2016; Reeves, Citation2010; WHO, Citation2010). In addition, interprofessional collaboration is generally described as teamwork. Reeves et al. (Citation2018) found that there is a “a range of different typologies for varying team formations.” Effective teamwork has been found to improve quality, safety, efficiency, and satisfaction among patients and providers (Clements et al., Citation2007; Reeves, Citation2010). Babiker et al. (Citation2014) describe several challenges for the establishment of effective teamwork in healthcare. Existing challenges can be hierarchical structures, individualistic nature of healthcare delivery, or instability in healthcare teams (Babiker et al., Citation2014).

In previous studies about teamwork within the CHS, teamwork has been described as different professions working in parallel (Benjamins et al., Citation2015; Turley et al., Citation2018; Warmels et al., Citation2017; Wood & Blair, Citation2014). To our knowledge, there are no previous studies that define team-based visits in concordance with the Swedish CHS instructions from 2014, i.e., as two or more healthcare professionals who meet the child and his or her family simultaneously (National Board of Health and Welfare in Sweden, Citation2014; The Swedish Rikshandboken, Citation2019).

Contextual factors

According to the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) and the integrated Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (iPARIHS) framework, successful implementation requires understanding of the intervention’s characteristics, the outer and inner settings, the individuals involved, and the process of implementation (Damschroder et al., Citation2009; Harvey & Kitson, Citation2016). The context in which the implementation takes place is a multi-dimensional complex system, with a broad range of contextual factors that can influence the implementation process (Damschroder et al., Citation2009; Nilsen & Bernhardsson, Citation2019; Reed et al., Citation2018). External contextual factors relate to “outer settings” and include e.g., resources, environment, policies, and national guidelines (Damschroder et al., Citation2009; Li et al., Citation2018; Nilsen & Bernhardsson, Citation2019). Internal contextual factors relate to “inner settings” and include factors within the team (Damschroder et al., Citation2009; Sandberg, Citation2010).

From the perspective of system theory, contextual factors that can influence the implementation process are found in micro-, meso-, and macrosystems (D’Amour & Oandasan, Citation2005; Harvey & Kitson, Citation2016; Li et al., Citation2018). According to Nelson et al. (Citation2007) the organization’s smallest units are so-called clinical microsystem (Nelson et al., Citation2007). Contextual factors, present in all systems, can be understood as individual, organizational, and societal factors (Brennan et al., Citation2012; Harvey & Kitson, Citation2016; Pullon et al., Citation2016)

Clinical and theoretical importance of the study

Despite knowledge about teamwork in complex healthcare settings and new instructions for the Swedish CHS, the extent to which team-based visits have been implemented with equality and equity in the Swedish CHS has not yet been evaluated. This study is part of a larger research project that aims to produce evidence-based knowledge about teams and interprofessional collaboration within the CHS.

Aim

The objective of the present study was 1) to describe the prevalence of team-based visits in the Swedish CHS and 2) to describe possible associations between team-based visits and contextual (individual, organizational, and societal) factors that may affect the implementation of team-based visits. In order to collect a large amount of data and because of the limited knowledge on teamwork in the Swedish CHS, a national web-based survey was distributed (Polit & Beck, Citation2016) to all nurses, physicians, and psychologists engaged in the Swedish CHS.

Methods

Study design

In the present study, a cross-sectional study design was used (Polit & Beck, Citation2016).

Setting and participants

The Swedish CHS are led by public health nurses and pediatric nurses, who closely collaborate with general practitioners, pediatricians, and psychologists (Wallby et al., Citation2013; Wettergren et al., Citation2016). CHS are usually provided at Child Healthcare Centers (CHCs) or Family Centers, in separate facilities, or in close connection to a healthcare center. There, the CHS are co-located with other child- and parental services, such as maternal healthcare, preventive social services, and public preschool (National Board of Health and Welfare in Sweden, Citation2014; Wallby et al., Citation2013).

The Swedish healthcare system is designed to be a socially responsible, equity-driven system (Wettergren et al., Citation2016). The Swedish CHS are run by 21 county councils/regions, which are divided into six healthcare regions. The provision for and financing of the CHS are public matters distributed by private or public providers.

Statistics Sweden has produced a tool that is used to calculate care compensations from the state to the regions among others, i.e. Care Need Index (CNI). A high CNI, based on socio-economic factors, such as proportion of households with children under 5 years, single parents, low educational status, unemployment, and immigrants, results in more resources from the state to the regions and further on to the healthcare centers (Statistics Sweden; Sundquist et al., Citation2003).

The questionnaire

Following the recommendations as outlined by Polit and Beck (Citation2016), a study-specific questionnaire based on the interplay between theory and field research was developed by a research group with experiences from clinical CHS, regional and national CHS development, research on teams, and knowledge of questionnaire design. Face validity was assessed through consultation with several experts in CHS. In addition, for content validity, the questionnaire content was tested by 20 CHS-developers, practitioners, senior practitioners, and psychologists at different regional Main Child Healthcare Units (MCHU). Minor adjustments were made to the questions for them to be suitable nationwide and to be appropriate for all the included professions. Before its final release, the questionnaire was tested in a group of 15 healthcare developers and doctoral students (Polit & Beck, Citation2016). After the pilot test, the concept “teamwork” needed some clarifications in the questionnaire instructions in order to achieve content validity (Polit & Beck, Citation2016).

The questionnaire had three parts, containing a total of 13 core questions with different follow-up questions (for more details, see appendix I). The first part focused on individual factors (the microsystem level) and characteristics of the respondents, including gender, profession, education, and years in the CHS. Questions about organizational factors were studied in terms of workplace, hours per week in the CHS, number of workplaces in the CHS, and operator. There were also questions about the CNI, catchment area, and healthcare region for the societal factors. The respondents that had knowledge about the CNI were asked to answer questions about it.

The second part of the questionnaire contained questions about interprofessional teamwork. Information about the respondents’ participation in interprofessional collaboration or teamwork was obtained from a multiple-choice question worded as follows: “Does your work in the CHS include any of the following team structures?” The response options were team-based visits, consultation, collaboration on parent groups, team meetings, or other forms of inter professional collaborations. Respondents who answered that they participated in any type of team-based visits were asked an additional multiple-choice question about the indications for team-based visits.

The third part of the questionnaire contained follow-up questions about experiences with and perceptions of interprofessional collaboration and teamwork, as well as questions about professions with whom the respondents might collaborate. These questions were included to address a different research question and will be published separately. The present paper only reports the results from the first and the second part of the questionnaire.

Sample

The questionnaire was electronically distributed to 3,552 nurses, physicians, and psychologists engaged in the Swedish CHS between October 2017 and February 2018. E-mail addresses were obtained by the CHS-developers and managers in each county council/region as well as by the National Psychologist Association. Regulations for obtaining e-mail addresses for questionnaires varied among county councils/regions. Most of the e-mail addresses were provided by the MCHU, but in some cases, permission from the regional/county council’s management or Research and Development Units was required, prior to sharing of addresses by managers.

Collecting and organizing data

The obtained e-mail addresses were uploaded to a digital survey tool, Artologic. The questionnaire and an accompanying letter were e-mailed by Artologic. Two reminders were sent out. The responses were saved in an Excel file that was transferred to IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk NY).

For the variable gender, the response option “other” (0.6%) was not included in the subsequent analyses. Responses about physicians’ and nurses’ education and sub-specialties were merged into two groups: public healthcare and pediatric healthcare. The responses for years in child healthcare were categorized as <6, 6–20, or >20. Workplace was a multiple-choice question. The responses were prioritized based on organizational prerequisites. When the Family Center was one of several answers, other responses were omitted before the variable was categorized as Family Center. The workplace category “other” included psychologist Clinic, MCHU, healthcare center, and specialist CHS. Number of hours per week in the CHS was categorized as >24, 17–24, or <17. The number of workplaces was categorized as 1, 2, or >2. CNI was categorized as low or high. A multiple-choice question was used for catchment area. Seven respondents chose more than one catchment areas. Those seven respondents were omitted.

Data analysis

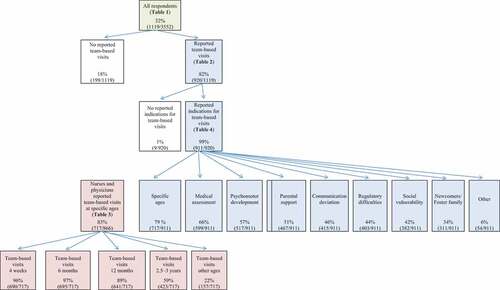

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize characteristics of the study population, for contextual factors and for the prevalence of different team-based visits. illustrates the distribution of responses for different team-based visits. The prevalence of universal team-based visits at specific ages was calculated based on the number of nurses and physicians who reported that they used to participate in such visits. The prevalence of targeted team-based visits was based on the total number of nurses, physicians, and psychologists who reported any team-based visits.

Binary logistic regression analyses were conducted to investigate possible associations between team-based visits and individual factors (gender, profession, education, years in the CHS), organizational factors (hours per week in the CHS, workplace, operator) and societal factors (catchment area, CNI, healthcare region). Team-based visits overall, and team-based visits for each specific indication, were used as dependent variables, and individual, organizational, and societal factors were used as independent variables.

Thereafter, variables associated with team-based visits on various indications (p < .05) were fitted into multivariate logistic regression analysis with the Forward Stepwise method in three groups (individual, organizational, and societal factors). Adjustments were made for gender, profession, and other variables within the contextual group that were significantly associated with the team-based visits. Organizational and societal factors were adjusted for gender and profession since most men were physicians. Psychologists were excluded when analyzing team-based visits at specific ages because only physicians and nurses take part in these visits. The questions about CNI were analyzed separately because only 27% of the respondents reported that they had knowledge of the CNI. The results are reported as crude and adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals with their p-values given. The significance level was set at p < .05. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS, v.22.0.

Ethical considerations

The questionnaire was reviewed and approved by the Regional Ethics Review Board in Uppsala, Sweden (Diary number 2017/356). All survey participants were informed, and consent was obtained by answering the web-based questionnaire. Confidentiality was ensured by sending the answers electronically directly to the survey tool, where the answers were encoded.

Results

Characteristics of respondents

In total, 1,119 out of 3,552 professionals responded to the questionnaire, resulting in a response rate of 32%. shows the demographic characteristics of the study population, in total and per profession.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of study population

Team-based visits

shows a schematic diagram of the indications, numbers, and prevalence of the various team-based visits for all respondents. Overall, team-based visits in the CHS were reported by eight out of ten respondents. Among all respondents reporting team-based visits, the most frequent indication for team-based visits was specific ages, followed by medical issues and assessment of psychomotor development (). Per profession, 89% of the nurses, 87% of the physicians, and 38% of the psychologists performed the team-based visits ().

Table 2. Associations between team-based visits in general and contextual factors

Team-based visits at specific ages

More than eight out of ten nurses and physicians performing the team-based visits reported universal team-based visits at specific ages (). The most frequent ages for team-based visits were 4 weeks and 6 months. Team-based visits at 2.5 to 3 years were only reported by six out of ten nurses and physicians. Furthermore, 157 (22%) of the nurses and physicians reported team-based visits at other ages, according to the former national instruction for the Swedish CHS (specific data not shown).

Table 3. Associations between team-based visits at specific ages for nurses and physicians and contextual factors

Indications for team-based visits

shows that the second most frequent indication for nurses performing team-based visits was medical assessment, followed by assessment of psychomotor development and parental support. Among physicians, the second most frequent indication was medical assessment, followed by assessment of psychomotor development and communication deviations. For psychologists, who only performed targeted team-based visits, the most frequent indication was parental support, followed by assessment of psychomotor development and communication deviations.

Table 4. Associations between indications for targeted team-based visits and contextual factors

Associations between different team-based visits and individual factors

When compared as individual groups, both nurses and physicians reported performing team-based visits significantly more often than psychologists (). Physicians reported team-based visits at the age of 2.5 to 3 years significantly more often than nurses (). Public health nurses and general practitioners reported performing team-based visits at specific ages in general (p = .001) (specific data not shown), and at the ages of 6 and 12 months significantly more often than pediatric nurses and pediatricians ().

Nurses and psychologists, respectively, reported targeted team-based visits to a higher degree than physicians with regard to parental support, communication deviations, and social vulnerability, as shown in . However, nurses reported targeted team-based visits indicated by newcomers in Sweden or foster family placement to a higher degree than psychologists (). Physicians, however, performed targeted team-based visits indicated by medical issues to a higher extent than both nurses and psychologists, respectively. Correspondingly, psychologists reported team-based visits for other reasons significantly more often than both nurses and physicians ().

Nurses and physicians who had worked less than six years in the CHS conducted team-based visits at specific ages more than respondents who had worked in the CHS for 6 to 20 years or more (p =.045) (specific data not shown). In contrast, respondents who had worked more than six years in the CHS conducted targeted team-based visits indicated by regulatory difficulties, social vulnerability and newcomers in Sweden or foster family placement to a higher degree than respondents who had worked fewer years ().

Associations between different team-based visits and organizational factors

Respondents who worked at Family Centers performed team-based visits to a higher degree than respondents who worked in CHCs or in other places (). Nurses and physicians, who worked in CHCs conducted team-based visits at the age of 4 weeks to a higher degree than respondents who worked at Family Centers, while the opposite was seen for the team-based visits at 2.5 to 3 years of age (). Respondents who worked at Family Centers performed targeted team-based visits because of parental support, communication deviation, regulatory difficulties, social vulnerability and newcomers in Sweden or foster family placement to a higher degree than respondents who worked in CHCs or elsewhere ().

Associations between different team-based visits and societal factors

Healthcare region was significantly associated with the extent to which various team-based visits were performed. This was observed for all universal team-based visits at specific ages, except for 6 months () and for all exemplified targeted team-based visits, except for medical assessments (). For team-based visits at the age of 2.5 to 3 years, there were also positive associations with catchment areas smaller than city size ().

A separate analysis for “CNI” showed that respondents who worked in areas with a “low CNI” performed team-based visits (97%) to a significantly higher degree than respondents who worked in areas with a “high CNI” (90%) or “varied CNI” (79%) (p = .007). The associations remained when adjusted for “gender” and “profession” (p = .006) (data not shown).

Discussion

This study is a first attempt to describe the prevalence of, as well as associations between, team-based visits and contextual factors, and to provide a comprehensive understanding of contextual factors that may affect the implementation of such visits. We have not found any previous studies that describe team-based visits within the CHS, as it is described in the Swedish CHS program.

Our main findings indicate that team-based visits are well established in the Swedish CHS, but the pattern differs in relation to contextual factors. Universal team-based visits at the specific ages of 4 weeks and 6 and 12 months were well implemented, in contrast to the visit at 2.5 to 3 years (). Targeted team-based visits did not occur to the same extent as the universal team-based visits at specific ages.

Team-based visits were found to be practiced by nine out of the ten responding nurses and physicians. Psychologists, who only have a role in targeted team-based visits, were not generally involved in the team-based visits to the same extent as nurses and physicians.

Our findings show that working at Family Centers is positively associated with team-based visits in general, team-based visits at 2.5 to 3 years, and targeted team-based visits. The results provide a comprehensive understanding of contextual factors that may have affected the implementation of team-based visits within the Swedish CHS. In accordance with Damschroder et al. (Citation2009) we observed an interplay between individuals and the organization within which they worked. This interplay influenced the implementation of team-based visits in general, team-based visits at 2.5 to 3 years, and targeted team-based visits.

Inequalities in prevalence of team-based visits in the Swedish CHS

Almost all the nurses and physicians participating in the team-based visits at specific ages did so at 4 weeks and 6 months. However, when it came to team-based visits at 2.5 to 3 years, only six out of ten participated. Also, a fifth of the responding nurses and physicians commented that team-based visits were conducted at other ages in line with the previous national instructions (i.e., 6 weeks, 10 months, 18 months, or 5.5 to 6 years). Our results highlight inequalities regarding children’s and families’ access to team-based visits at specific ages, especially at 2.5 to 3 years. We could also show that respondents participated in targeted team-based visits indicated by additional needs to a lesser extent than universal team-based visits. The most frequently reported indications for targeted team-based visits were medical assessment and psychomotor development, followed by parental support. Furthermore, we found that targeted team-based visits in cases of adoption, migration, and foster care were only reported by 34% of the respondents performing team-based visits. Previous studies have shown that foreign-born children and children in foster care are vulnerable groups, known to suffer from health problems and having less access to healthcare than children without this background (Kohler et al., Citation2015; Vinnerljung et al., Citation2018). Targeted team-based visits ought to be offered to all children and families with additional needs, such as in cases of adoption, migration, and foster care (Oberklaid et al., Citation2013; The Swedish Rikshandboken, Citation2019). However, targeted services for additional support and complex needs could be more difficult to distribute (Wallby & Hjern, Citation2011). The present findings are similar to previous studies, reflecting an unequal distribution in the Swedish CHS (Magnusson et al., Citation2011; Wallby, Citation2012).

Contextual factors

Until now studies investigating team-based visits from a system-theoretical perspective and related contextual factors have been lacking. Relatively few frameworks and studies emphasize the “outer setting” and contextual factors at the macro-level (Nilsen & Bernhardsson, Citation2019). Therefore, we used a system theoretical model, i.e., the Clinical Microsystems Approach as described by Nelson et al. (Citation2007), to identify contextual factors on different levels.

Contextual factors that enabled and hindered implementation are found in the clinical microsystems (teams), the mesosystems (healthcare center), and the macrosystems (healthcare region) (Nelson et al., Citation2007). Damschroder et al. (Citation2009) describe an interplay between individuals, the intervention, and other contextual factors. A professional´s ability to participate in team-based visits can be influenced by their own views of their roles (Evetts, Citation2013), employment models, coordination, resources, and time (Pullon et al., Citation2016). In our study, individual factors such as profession, further education in the field, and years of experience in the CHS seemed to interact with organizational factors such as physical workplace as well as societal factors such as structures in healthcare regions and the national CHS program.

Individual factors

Our study found that the individual contextual factors with the strongest influence on participating in team-based visits was profession. Both nurses and physicians reported team-based visits to a higher degree than psychologists, explained by the fact that psychologists do not take part in universal team-based visits at specific ages. On the other hand, both psychologists and nurses reported targeted team-based visits to a higher degree than physicians when it came to parental support, communication deviations, and social vulnerability. Physicians predominantly performed targeted team-based visits for medical assessments. Damschroder et al. (Citation2009) and Drinka (Citation2016) describe that organizational change starts with the individuals. According to Tell et al. (Citation2018), the implementation object in the national instructions must match the professionals’ needs and be perceived as relevant. Personal characteristics and profession (i.e., age, gender, experience, knowledge) are known to play a major role during the formation of teams (Drinka, Citation2016). Further, team-constellation depends on the type of problem to be solved and the support to be given (Golom & Schreck, Citation2018; WHO, Citation2010). Physicians, psychologists, and nurses have a role in targeted team-based visits. In our study, the type of indications for the targeted team-based visits was found to be associated with both professional affiliation and professional competencies. Further, we found that respondents with more than six years of experience in CHS reported both team-based visits in general and targeted team-based visits indicated by regulatory difficulties, social vulnerability, and newcomers in Sweden or foster family placement to a higher degree than respondents who had worked fewer years in CHS. According to Drinka (Citation2016), complex healthcare needs require knowledge about other professionals’ competence and that high rate of staff turnover obstructs teamwork. It appears that more years in CHS could be associated with better knowledge of professionals’ roles, which could lead to higher extent of team-based visits in general as well as in cases of complex needs.

Organizational factors

The strongest influence of team-based visits was connected to Family Centers. Respondents working at Family Centers were more likely to perform team-based visits in general, at 2.5 to 3 years and in case of additional needs, compared to respondents working at CHCs and other workplaces, respectively. The results are congruent with previous studies describing that co-location of professionals is an enabler of interprofessional collaboration (Pullon et al., Citation2016; Turley et al., Citation2018). Contextual factors of importance for implementation of new methods in the mesosystem include providing infrastructure and prioritizing resources (Damschroder et al., Citation2009; Pullon et al., Citation2016).

Previous studies indicate that professionals are influenced by the social context in which they participate (Damschroder et al., Citation2009; Li et al., Citation2018). Professionals in Family Centers often have extensive experience, a strong commitment to the target group, clear professional identity, team thinking, and collaborative skills that may affect other team-based activities (Nylen, Citation2007; Nylén, Citation2018). Family Centers are physical, social, and symbolical spaces. According to Gum et al. (Citation2012), professionals are influenced by the social spaces in which they participate, and the culture is determined by those within. In Family Centers, a culture of teamwork and collaboration can emerge. Bulling and Berg (Citation2018) showed that professionals with experience of collaboration and working in teams developed team competences with an opportunity to broaden their experiences (Bulling & Berg, Citation2018; Gum et al., Citation2012; Nylén, Citation2018). However, there is a need for future research to focus on how organizational features interact with and influence the effectiveness of team-based visit implementation as highlighted by Li et al. (Citation2018).

The team-based visit at age 2.5 to 3 years is new according to the previous national instructions. Nurses and physicians working at Family Centers were found to participate in team-based visits at 2.5 to 3 years to a higher degree than their counterparts at other workplaces. Professionals in organizations with a high degree of networking with other organizations are more likely to implement new practices (Damschroder et al., Citation2009; Li et al., Citation2018). Thus, an environment allowing for new collaborations between professions and organizations is likely to be an explanation for a higher extent of team-based visits at the age of 2.5 to 3-year at Family Centers.

In our study, respondents working in the CHS at Family Centers reported more targeted team-based visits indicated by developmental and social difficulties than their counterparts working at CHCs or other places. However, only 11% of the psychologists in the present study were working with the CHS at a Family Center (). Drinka (Citation2016) describe the importance of structuring collective expertise of professionals to address complex healthcare needs. Pullon et al. (Citation2016) point at the benefit of opportunities for frequent and brief communication when healthcare providers are co-located. It has been shown that Family Centers offer opportunities to collaborate in the care of a target group with complex needs, where different skills and resources are needed (Nylén, Citation2018; Wallby et al., Citation2013). In addition to bringing people together, structure and resources are needed to create time and regular meetings to formalize shared goals for effective collaboration (Bulling & Berg, Citation2018; Li et al., Citation2018). However, it can be difficult to calculate resources and coordinate participation from different professionals in the team. Our results, consistent with previous studies as shown above, indicate the importance of co-location of the CHS for an equal implementation of team-based visits, thus fairly reaching children and their families.

Societal factors

We found that team-based visits in general were conducted in all healthcare regions, but the extent to which various indications resulted in team-based visits differed between the regions. This was evident for the team-based visits at the age of 2.5 to 3 years, 4 weeks, 12 months (), and targeted team-based visits (). Nilsen and Bernhardsson (Citation2019) describe that outer context refers to macro-level influences beyond the organization, e.g., national guidelines or policies. The Swedish healthcare system is governed by politicians and managers, nationally and regionally (Wettergren et al., Citation2016). The healthcare regions responsible for implementing the national CHS program are simultaneously self-governing and can make local decisions and set priorities regarding the distribution of resources (Tell et al., Citation2018; Wettergren et al., Citation2016). According to Tell et al. (Citation2018), the MHCU in each region is responsible for monitoring children’s health, educating and supporting staff, and improving the local CHS but has different degrees of mandate for decisions on resources for the CHS. Managers and leaders at different levels have important roles in emphasizing organizational support, prioritizing, and providing infrastructure and resources (Berlin & Carlström, Citation2013; Damschroder et al., Citation2009). The leadership could be a mediator that enhances or impedes the implementation of evidence-based practices (Li et al., Citation2018). Berlin and Carlström (Citation2013) describe how established routines, traditions, and hierarchy can hinder implementation of new methods. Despite national instructions to obtain an equal and evidence-based CHS, there are differences between the healthcare regions, including differences in collaborations on an organizational level, as well as organizational support or resources for nurses’, physicians’, and psychologists’ involvement in team-based visits in the Swedish CHS.

In our separate analysis for Care Need Index (CNI), we found that respondents who worked in areas with a “high CNI” performed team-based visits to a lower degree than others. Resources can be meaningfully directed to shape the contextual features that have a high impact on implementation outcomes (Evetts, Citation2013; Li et al., Citation2018). According to Tell et al. (Citation2018), the lack of a national implementation strategy with resources linked to the assignment places higher demands on professionals and management at all levels to organize and support the implementation. Relatively few frameworks and studies emphasize the “outer setting” and contextual factors at the macro-level (Nilsen & Bernhardsson, Citation2019). However, our results indicate that politicians and managers have prioritized other fields within healthcare than targeted team-based visits in the Swedish CHS, even though a “high CNI” is linked to more resources. Implementing a national CHS program does not automatically result in having team-based visits with equality and equity. A large healthcare organization can never be better than the care provided by the organization’s smallest units, the so-called clinical microsystem (Nelson et al., Citation2007), which in the CHS is constituted by the interprofessional CHS teams.

Methodological considerations

When designing the present study, to the best of our efforts, we found no data on team-based visits in the Swedish CHS, and data on contextual factors in the Swedish CHS are scarce (Wallby, Citation2012). Therefore, we distributed a web-based questionnaire to measure the prevalence of team-based visits and to identify contextual factors nationwide, by including all reachable nurses, physicians, and psychologists. Still, although response rates for web-based questionnaires are generally declining, these are cost-effective in terms of collecting large quantitative data (Baruch and Holtom, Citation2008; Ebert et al., Citation2018).

Since a coherent registry of all staff working within the Swedish CHS is lacking, contact e-mail addresses were sought by the MCHUs in each region. Some of the MCHU´s were not allowed to pass on these addresses or lacked the information. In these cases, we got the contact information for the managers at the local CHS, the regional council’s management, or Research and Development Units in the region.

To obtain a high response rate, we collaborated actively with the CHS-developers in the MCHUs by e-mail and in person at national meetings, which is in accordance with Baruch et al. (Citation2008). Two reminders were sent out (Polit & Beck, Citation2016). Most of the respondents answered after the first reminder, in line with previous studies (Cook et al., Citation2016). Our response rate of 32% could be a concern; however, it is often seen in web-based healthcare research (Baruch and Holtom, Citation2008). Many studies report response rates of 10–40% (Cook et al., Citation2016; Ebert et al., Citation2018).

Studies have demonstrated that there is no direct correlation between the response rate and validity (Morton et al., Citation2012). The concept of representative sampling depends on having a large enough sample (Phillips et al., Citation2016). According to Phillips et al. (Citation2016), a low response rate does not introduce any bias if the drop out is not correlated to the survey topic. The distribution of respondents, as shown in , is considered representative of the distribution of the CHS staff in Sweden, when compared with other Swedish studies (Wallby et al., Citation2013; Wallby & Hjern, Citation2011; Wettergren et al., Citation2016) and in communication with the MCHUs. To evaluate nonresponse bias, we compared late responders with earlier responders (Johnson & Wislar, Citation2012), since late respondents could be a proxy for non-respondents (Phillips et al., Citation2016). The comparison showed no significant differences in gender, profession, workplace, or team-based visits.

We did not conduct a power analysis beforehand since the present study was a total population-based study, i.e., we aimed to include all nurses, physicians, and psychologists engaged within the Swedish CHS. The main limitation of the present study, though, is the rather low response rate (32%).

Nevertheless, the present study is large with 1,119 participants and little missing data as most of the questions were answered. Another strength of the present study is the thorough development of the questionnaire. In communication with developers at the MCHUs in different county councils/regions, we compared the results with regional data, which made the survey valid nationally. Furthermore, the variables at different levels in the questionnaire enable an analysis from a system theoretical perspective. This study is also part of a larger research project, where qualitative studies will be used as a complement to achieve the overall aim.

The stepwise model has been criticized because it can be heavily influenced by random variation in data (Pallant, Citation2016). To avoid this, we built three different models based on our hypotheses about factors that possibly can affect team-based visits. By analyzing the variables separately and based on our knowledge about different levels that can affect the clinical microsystem, we believe we avoided random variations in the selected variables.

Conclusion

This study focuses on contextual factors at all system levels associated with the implementation of team-based visits in the Swedish CHS. According to Kaplan et al. (Citation2010) and Walshe (Citation2007), there is a lack of research based on conceptual models that examine contexts across all levels of the healthcare system, as well as the relationships among various aspects of the context (Kaplan et al., Citation2010; Walshe, Citation2007).

The results show differences in the extent to which team-based visits are performed, pointing at complex interactions between indications for team-based visits and investigated contextual factors. Nurses and physicians reported significantly more team-based visits than psychologists, explained by the fact that team-based visits at specific ages are universal. We also found that respondents working at Family Centers were more likely to conduct team-based visits in general, to conduct visits at 2.5 to 3 years, and to conduct targeted team-based visits compared to their counterparts working at CHCs and other workplaces.

The responsibility for children’s rights to access CHS and to the best achievable health is found in the clinical microsystems (teams), the mesosystems (healthcare centers), and the macrosystems (healthcare region). The full needs of children and families, however, can only be met through effective collaboration. Therefore, our noted associations between team-based visits within the CHS and contextual factors at all levels are important results.

The study is of high clinical relevance as it contributes with new knowledge regarding innovative ways of working in healthcare. Furthermore, previous studies (Szafran et al., Citation2018; Turley et al., Citation2018; Warmels et al., Citation2017) support the continued development of team-based care. Individuals have the responsibility to contribute according to the national CHS program, but managers have an important role in emphasizing organizational support, prioritizing, and providing infrastructure and resources for nurses’, physicians’, and psychologists’ involvement in team-based visits in the CHS.

In order to deliver CHS by interprofessional teams within a framework of progressive universalism – with universal team-based visits for all children and their families and targeted team-based visits for those with additional needs – location in Family Centers, seems to be an enabler. This study is a first attempt to describe the contextual factors associated with team-based visits in the CHS in Sweden. Further qualitative research is needed for a deeper understanding of team-based visits as well as contextual factors in order to know how to achieve an even and equitable distribution of CHS.

Declaration of interest

The authors alone are responsible for the writing and content of this article. A potential conflict of interest in this article is that the first author is involved in the implementation of the team-based visits in the Swedish CHS. The authors report no other conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all nurses, physicians, and psychologists working in the CHS for taking their time to participate in this study. This work was supported by the Gillbergska Foundation, the Swedish Society of Nursing, Region Sörmland, and the Centre for Clinical Research Sörmland/Uppsala University.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ulrika Svea Nygren

Ulrika Svea Nygren, Doctoral Student in caring science at the Department of Public Health and Caring Science at Uppsala University, Sweden. She is affiliated at the Center for Clinical Research in Region Sörmland, Uppsala University, Sweden. Ulrika is a Public Health Nurse with a master in organizational leadership, currently working as a developer of the Child Healthcare in Region Sörmland, Sweden.

Ylva Tindberg

Ylva Tindberg, associated professor in pediatrics at the Department of Women´s and Children´s Health at Uppsala University. She is affiliated at the Center for Clinical Research, Region Sörmland, Sweden. Her publications are in the field of social pediatrics, child healthcare and adolescent medicine. Ylva is a senior consultant in pediatrics, currently working as a Medical Director of the Child Healthcare in Region Sörmland, Sweden.

Leif Eriksson

Leif Eriksson, associate professor in caring science at Uppsala University, Sweden. He is associated researcher at the research groups Caring Sciences at the Department of Public Health and Caring Science and Uppsala Global Health Research on Implementation and Sustainability at the Department of Women´s and Children´s Health, both at Uppsala University. Leif is currently working as an implementation scientist at the Center for Epidemiology and Community Medicine in Region Stockholm, Sweden. He has experience of implementation and evaluation from several large scale interventions, e.g. in Vietnam and Nepal, with focus on improving health and survival of newborn children.

Hans Eriksson

Hans Eriksson, statistician at the Center for Clinical Research in Region Sörmland, Eskilstuna, Sweden.

Håkan Sandberg

Håkan S Sandberg, associate professor in education and team researcher. He has published articles and textbooks in English and Swedish from different perspectives concerning mainly teamwork in the welfare sector. Currently affiliated teacher and researcher at Mälardalens University, Sweden. He also has worked with questions of continuing education at European Universities and spent a semester as guest teacher at Stirling University.

Lena Nordgren

Lena Nordgren, research advisor at the Center for Clinical Research in Sörmland, Uppsala University, Sweden and adjunct associate professor in caring science at Uppsala University, Sweden. Lena´s main research interest is people´s experiences of heart failure. Another main research area is therapy dogs in dementia care. Other areas of interest include (amongst other) implementation of clinical pathways, rehabilitaion, and health.

References

- Babiker, A., Husseini, M., Al Nemri, P. A., Frayh, A., Al Jurayyan, N., Faki, M., Zamil, F., Shaikh, F., Al Zamil, F., & Assiri, A. (2014). Current opinion health care professional development: Working as a team to improve patientcare. Sudanese Journal of Paediatrics, 14(2), 9–16. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4949805/

- Baruch, Y., & Holtom, B. C. (2008). Survey response rate levels and trends in organizational research. Human Relations, 61(8), 1139–1160. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726708094863

- Benjamins, S. J., Damen, M. L. W., Van Stel, H. F., & Simeoni, U. (2015). Feasibility and impact of doctor-nurse task delegation in preventive child health care in the Netherlands, a controlled before-after study. Plos One, 10(10), 10. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0139187

- Berlin, J., & Carlström, E. (2012). Trender som utmanar traditioner – En hälso- och sjukvård i metamorfos. Scandinavian Journal of Public Administration, 16(2). https://ojs.ub.gu.se/ojs/index.php/sjpa/article/view/1676

- Brennan, S. E., Bosch, M., Buchan, H., & Green, S. E. (2012). Measuring organizational and individual factors thought to influence the success of quality improvement in primary care: A systematic review of instruments. Implementation Science, 3(2):11-13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-7-121

- Bulling, I. S., & Berg, B. (2018). “It’s our children!” Exploring intersectorial collaboration in family centres. Child & Family Social Work, 23(4), 726–734. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12469

- Careau, E., Bainbridge, L., Steinberg, M., & Lovato, C. (2016). Improving interprofessional education and collaborative practice through evaluation: An exploration of current trends. Canadian Journal of Program Evaluation, 31(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.3138/cjpe.225

- Clements, D., Dault, M., & Priest, A. (2007). Effective teamwork in healthcare: Research and reality. Healthcare Papers, 7(SP), 26–34. https://doi.org/10.12927/hcpap.2013.18669

- Cook, D. A., Wittich, C. M., Daniels, W. L., West, C. P., Harris, A. M., & Beebe, T. J. (2016). Incentive and reminder strategies to improve response rate for internet-based physician surveys: A randomized experiment. Journal of Medical Internet Reseach, 18(9), e244. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.6318

- D’Amour, D., & Oandasan, I. (2005). Interprofessionality as the field of interprofessional practice and interprofessional education: An emerging concept. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 19(Suppl 1), 8–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820500081604

- Damschroder, L. J., Aron, D. C., Keith, R. E., Kirsh, S. R., Alexander, J. A., & Lowery, J. C. (2009). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science, 3(5), 7-9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-4-50

- Drinka, T. J. K. (2016). Healthcare teamwork: Interprofessional practice and education (page 6, 32, 73-75, 213-215, 220, 268-270.

- Ebert, J. F., Huibers, L., Christensen, B., & Christensen, M. B. (2018). Paper- or web-based questionnaire invitations as a method for data collection: Cross-sectional comparative study of differences in response rate, completeness of data, and financial cost. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 20(1), e24. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.8353

- Evetts, J. (2013). Professionalism: Value and ideology. Current Sociology, 61(5–6), 778–796. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392113479316

- Foley, M., Dunbar, N., & Clancy, J. (2014). Collaborative care for children: A grand rounds presentation. Journal of School Nursing, 30(4), 251–255. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059840513484364

- Golom, F. D., & Schreck, J. S. (2018). The journey to interprofessional collaborative practice: Are we there yet? Pediatric Clinics of North America, 65(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcl.2017.08.017

- Gum, L. F., Prideaux, D., Sweet, L., & Greenhill, J. (2012). From the nurses’ station to the health team hub: How can design promote interprofessional collaboration? Journal of Interprofessional Care, 26(1), 21–27. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2011.636157

- Harvey, G., & Kitson, A. (2016). PARIHS revisited: From heuristic to integrated framework for the successful implementation of knowledge into practice. Implementation Science, 11, 4-7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0398-2

- Johnson, T. P., & Wislar, J. S. (2012). Response rates and nonresponse errors in surveys. JAMA, 307(17), 1805–1806. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.3532

- Kaplan, H. C., Brady, P. W., Dritz, M. C., Hooper, D. K., Linam, W. M., Froehle, C. M., & Margolis, P. (2010). The influence of context on quality improvement success in health care: A systematic review of the literature. Milbank Quarterly, 88(4), 500–559. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0009.2010.00611.x

- Kohler, M., Emmelin, M., Hjern, A., & Rosvall, M. (2015). Children in family foster care have greater health risks and less involvement in child healthservices. Acta Paediatrica, 104(5), 508–513. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.12901

- Li, S.-A., Jeffs, L., Barwick, M., & Stevens, B. (2018). Organizational contextual features that influence the implementation of evidence-based practices across healthcare settings: A systematic integrative review. Systematic Reviews, 7(1), 1-2, 15-16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-018-0734-5

- Magnusson, M., Lindfors, A., & Tell, J. (2011). Big differences in Swedish child health care. Child health care units decide their services–alarming that a national program is missing. [Stora skillnader i svensk barnhalsovard. Barnhalsovardsenheter avgor sjalva–oroande att nationellt program saknas.]. Läkartidningen, 108(35), 1618–1621. https://kli/klinik-och-vetenskap-1/2011/08/stora-skillnader-i-svensk-barnhalsovard/

- Morton, S. M. B., Bandara, D. K., Robinson, E. M., & Carr, P. E. A. (2012). In the 21st Century, what is an acceptable response rate? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 36(2), 106–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-6405.2012.00854.x

- National Board of Health and Welfare in Sweden. (1991). Hälsoundersökningar inom barnhälsovården Allmänna råd från Socialstyrelsen 1991:8 (pp. 0280–0667), Socialstyrelsen.

- National Board of Health and Welfare in Sweden. (2014). Vägledning för barnhälsovården [Instructions for Child Healthcare].

- Nelson, E. C., Batalden, P. B., & Godfrey, M. M. (2007). Quality by design: A clinical microsystems approach (pp. 3–7, 148–163). Wiley.

- Nilsen, P., & Bernhardsson, S. (2019). Context matters in implementation science: A scoping review of determinant frameworks that describe contextual determinants for implementation outcomes. [Review]. BMC Health Services Research, 19(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4015-3

- Nylen, U. (2007). Interagency collaboration in human services: Impact of formalization and intensity on effectiveness. Public Administration, 85(1), 143–166. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2007.00638.x

- Nylén, U. (2018). Multi-professional teamwork in human services: The mutual shaping of professional identity and team activities. Journal of Health Organization and Management, 32(5), 741–759. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHOM-03-2017-0062

- Oberklaid, F., Baird, G., Blair, M., Melhuish, E., & Hall, D. (2013). Children’s health and development: Approaches to early identification and intervention. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 98(12), 1008. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2013-304091

- Pallant, J. (2016). SPSS survival manual: A step by step guide to data analysis using IBM SPSS. Open University Press.

- Phillips, A. W., Reddy, S., & Durning, S. J. (2016). Improving response rates and evaluating nonresponse bias in surveys: AMEE Guide No. 102. Medical Teacher, 38(3), 217–228. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2015.1105945

- Polit, D. F., & Beck, C. T. (2016). Nursing research: Generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice (pp. 223–234, 266–282, 301, 310–311). Wolters Kluwer.

- Pullon, S., Morgan, S., Macdonald, L., McKinlay, E., & Gray, B. (2016). Observation of interprofessional collaboration in primary care practice: A multiple case study. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 30(6), 787–794. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2016.1220929

- Reed, J. E., Kaplan, H. C., & Ismail, S. A. (2018). A new typology for understanding context: Qualitative exploration of the model for understanding success in quality (MUSIQ). BMC Health Services Research, 18(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3348-7

- Reeves, S. (2010). Interprofessional teamwork for health and social care (pp. 44–58, 70–80, 120). Blackwell.

- Reeves, S., Xyrichis, A., & Zwarenstein, M. (2018). Teamwork, collaboration, coordination, and networking: Why we need to distinguish between different types of interprofessional practice. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 32(1), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2017.1400150

- Sandberg, H. (2010). The concept of collaborative health. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 24(6), 644–652. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561821003724034

- Sundquist, K., Malmström, M., Johansson, S. E., & Sundquist, J. (2003). Care Need Index, a useful tool for the distribution of primary health care resources. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 57 (5), 347–352. 36/jech.57.5.347. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.57.5.347

- The Swedish Rikshandboken. (2019, January 19). Rikshandboken i Barnhälsovård [RHB] Barnhälsovårdens nationella program [In Swedish. English translation by the author: The national child health care program]. Inera AB. https://www.rikshandboken-bhv.se/Retrieved.

- Szafran, O., Kennett, S. L., Bell, N. R., & Green, L. (2018). Patients’ perceptions of team-based care in family practice: Access, benefits and team roles. Journal of Primary Health Care, 10(3), 248–257. https://doi.org/10.1071/HC18018

- Tell, J., Andersson, G., Sanmartin Berglund, J., Olander, E., & Anderberg, P. (2019). Implementation and use of web-based national guidelines in child healthcare [Elektronisk resurs]. Blekinge Tekniska Högskola.

- Tell, J., Olander, E., Anderberg, P., & Berglund, J. S. (2018). Implementation of a web-based national child health-care programme in a local context: A complex facilitator role. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 46(20_suppl), 80–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494817744119

- Turley, J., Vanek, J., Johnston, S., & Archibald, D. (2018). Nursing role in well-child care Systematic review of the literature. Canadian Family Physician, 64(4), E169–E180. https://www.cfp.ca/content/64/4/e169.full

- Van Den Steene, H., Van West, D., & Glazemakers, I. (2019). Towards a definition of multiple and complex needs in children and youth: Delphi study in Flanders and international survey. Scandinavian Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Psychology, 7, 60–67. https://doi.org/10.21307/sjcapp-2019-009

- Vinnerljung, B., Kling, S., & Hjern, A. (2018). Health problems and healthcare needs among youth in Swedish secure residential care. International Journal of Social Welfare, 27(4), 348–357. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsw.12333

- Wallby, T. (2012). Lika för alla?: Social position och etnicitet som determinanter för amning, föräldrars rökvanor och kontakter med BVC. Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis.

- Wallby, T., Fabian, H., & Sarkadi, A. (2013). Child Health Centers within Family Centers offers better parental support. A national web-based survey reveals advantages of co-location. [Battre stod till foraldrar vid familjecentraler. Nationell webbenkat visar pa fordelar med samlokalisering.]. Läkartidningen, 110(23–24), 1155–1157. https://kli/klinik-och-vetenskap-1/artiklar-1/originalstudie/2013/06/battre-stod-till-foraldrar-vid-familjecentraler/

- Wallby, T., & Hjern, A. (2011). Child health care uptake among low-income and immigrant families in a Swedish county. Acta Paediatrica, 100(11), 1495–1503. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02344.x

- Walshe, K. (2007). Understanding what works - and why - in quality improvement: The need for theory-driven evaluation. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(2), 57–59. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm004

- Warmels, G., Johnston, S., & Turley, J. (2017). Improving team-based care for children: Shared well child care involving family practice nurses. Primary Health Care Research and Development, 18(5), 507–514. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1463423617000160

- Wettergren, B., Blennow, M., Hjern, A., Soder, O., & Ludvigsson, J. F. (2016). Child Health Systems in Sweden. Journal of Pediatrics, 177, S187–S202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.04.055

- WHO. (2010). Framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice. World Health Organization.

- Wood, R., & Blair, M. (2014). A comparison of child health programmes recommended for preschool children in selected high-income countries. Child Care Health and Development, 40(5), 640–653. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12104