ABSTRACT

In the United Kingdom, the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic placed great pressures on universities to ensure final year health care students completed their studies earlier than planned in order to join the National Health Service workforce. This study aimed to explore the anticipations and support needs of final year allied health profession students transitioning to practice during a pandemic. Final year university students across seven healthcare professions were asked to complete an online survey. Demographic data were analyzed by descriptive statistics and responses to open questions were explored using content analysis. Sixty participants completed the survey. Content analysis regarding students’ anticipations, fears, and support needs identified the following themes: professional identity and growth; opportunities for improvement; preparedness for transition from university to the workplace, the workplace environment; COVID-19; support from lecturers; daily support within the workplace and innovative methods of support. Although the transition from student to practitioner continues to be a stressful period, only a minority of participants reported COVID-19 as an explicit stressor. However, as the effects of COVID-19 continue to evolve in the United Kingdom, universities and healthcare trusts must ensure adequate supports are in place for recent graduates navigating this transition during a healthcare crisis.

Introduction

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, changes were made to expedite the deployment of eligible final year nursing, medical, allied health and social work students into clinical practice in the United Kingdom (UK) (Health and Care Professions Council, Citation2020b; Swift et al., Citation2020). Emergency legislation was ratified enabling the Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC), the independent regulator for allied health professionals (AHP) in the UK, to establish a temporary register to facilitate early student entry into the Health and Social Care (HSC) workforce in advance of academic conferment of professional qualifications (Health and Care Professions Council, Citation2020a). Hundreds of students from AHP backgrounds were placed on the temporary register for deployment into the National Health Service (NHS) as part of the Department of Health’s (DOH) strategic planning (Health and Care Professions Council, Citation2020b).

The expectation that students would transition to posts earlier than anticipated was accompanied by a concern of varying levels of preparedness for this deployment into a service that had dramatically changed as a response to managing COVID-19. The challenge to university educators was to swiftly identify how to support this transition into the professional workforce at a time of unprecedented change and increased pressure.

It is accepted in the literature that both education and health service institutions have a responsibility to support healthcare professionals as they move from student to staff positions in the NHS (Duchscher, Citation2008). This type of support commonly includes preparatory education on transition, structured orientation and mentoring programmes. However, during a pandemic, realizing these aspects can be challenging, as the NHS and its staff are under immense pressure to deal with immediate and life-threatening events. This provides an opportunity to explore student anticipations and fears when confronted with transitioning into the NHS workforce during a pandemic and to determine perceived support needs at this juncture.

Background

To date, the vast majority of research identified on supporting transition pertains to the nursing profession and very limited research exists on AHP transition. However, the research that has emerged presents self-evident difficulties in the implementation of findings during a pandemic. Clements et al. (Citation2012) found that newly qualified midwives required supernumerary time to ease into clinical areas and use of study days to connect with peers. Support from colleagues, managers and educators was highly valued by new practitioners although workloads impacted upon the availability of such support. Similarly, Doody et al. (Citation2012) found that successful transition of nursing students to the workforce depended upon nurturing and supportive work environments that reduced stress and enhanced confidence. Peer–support was also identified as a key element in the transition (Doody et al., Citation2012). Further, issues seen increasingly during a pandemic, such as dealing with patient deaths and uncertainties in new situations, were highlighted as particular challenges by students in practice (Gidman et al., Citation2011). The totality of this evidence-based landscape alongside the findings of a recent study of AHPs that mentoring in these specific professional groups has traditionally lacked psychosocial support (Coppin & Fisher, Citation2016) helped drive the current study.

Study Aims

The purpose of this study was to conduct a cross-sectional survey with final year AHP students awaiting deployment into clinical practice. The aims were:

To explore the anticipations and fears of final year Allied Health Profession university students joining the workforce during a national pandemic

To determine the perceived support needs of the Allied Health Profession students on joining the workplace during a national pandemic

Methods

Research Design

A cross-sectional survey for distribution of all final year students across seven Allied Health cohorts within the School of Health Sciences at Ulster University in Northern Ireland, was co-designed with four final year occupational therapy students. Their expertise in the lived experience of students, in conjunction with researchers, strengthened the student-centered design of the study, and ensured validity of outcomes through reviewing questions for relevance to target population (Stewart & Liabo, Citation2012). The core research team was based within the Occupational Therapy department and recruited Occupational Therapy students in the first instance, with one student partner undertaking their clinical occupational therapy research placement with the project. Contact was made to course directors within the school; however, further recruitment of student partners from other AHP disciplines was unsuccessful.

Data collection

The survey questions were based on the literature (Edwards et al., Citation2019; Melman et al., Citation2016; Naylor et al., Citation2016) and co-produced with the student partners, who were dedicated to supporting the study throughout their deployment. A partnership approach was used in recognition of how co-production can be used to enhance the overall quality and impact of research findings, especially during the early stages of healthcare research development (Voorberg et al., Citation2015). Involvement in topic identification, question formulation, prioritization, and distribution may also alleviate potential biases from the researchers and stakeholders involved, and therefore strengthen the reliability of results (Tembo et al., Citation2019). An initial brainstorming meeting was held with the student partners using a video conferencing platform to help formalize the questions, which were later circulated via e-mail in a word document. The student partners submitted feedback on the phrasing and relevance of the questions. A final version of the survey was circulated for approval prior to submission to the ethics committee.

The final survey consisted of three closed demographic questions and nine open-ended questions, covering topics regarding student anticipations and fears about joining the workforce; perceived support needs from lecturers during transition; perceived support needs from colleagues/supervisors within the workplace; and potential innovative methods of support (see Online Supplement). The survey was open from the 19th to the 26th of May 2020, with an e-mail reminder at the midpoint and the day before the survey closed. This timeline for delivery of the survey was defined by the student partners during co-production sessions. Student partners decided three e-mails (opening survey, a reminder at mid-point and closing reminder) within a short time frame of 7 days would motivate students to complete the survey during a time of immense pressure where they were completing final exams and either on, or moving onto, the temporary register as part of the emergency response to COVID-19.

Participants and recruitment

The School of Health Sciences administrator sent an e-mail invitation to final year students (n = 226). The students were registered on the following programmes; Healthcare Science, Physiotherapy, Podiatry, Occupational Therapy, Diagnostic Radiography and Imaging, Radiotherapy and Oncology, and Speech and Language Therapy. The e-mail included background information about the study and a hyperlink taking the potential participant straight to the information sheet and consent form on the software platform Qualtrics [http://qualtrics.com]. On completion of the consent form, students proceeded to complete the survey.

Data Analysis

The data was downloaded from the online platform into an Excel spread sheet. Closed questions were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Content analysis was used to analyze the open‐ended items using inductive reasoning, suitable for the analysis of large amounts of textual data (Elo & Kyngäs, Citation2008). This process involved familiarization with the data, followed by the categorization and coding of the text. The research team (APA, JDL, MS, BT and WA), including one final year occupational therapy student (AMcL), undertook the analysis collaboratively and regularly met to compare their coding and discuss the emerging themes.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was obtained from the Institute of Nursing and Health Research, Ulster University, Research Governance Filter Committee.

Findings

A total of 226 surveys were distributed, and 60 students (51 females; 9 males) returned completed surveys, with a response rate of 26.5%. The majority of participants were within the age range 18–24 years (78%; n = 47), 10% were aged 25–34, 10% were aged 35–44 and one was between 45 and 54 years.

Content analysis of the open questions regarding students’ anticipations, fears, and perceived support needs led to the emergence of several themes, each of which is outlined in and described below.

Students’ anticipations of joining the workforce

When asked what they were looking forward to about going into the workplace, 58 participants responded, and anticipations covered two themes; ‘Professional identity and growth’ and ‘Opportunities for improvement.’

Theme 1: Professional identity and growth

Developing a professional identity was a key feature of participant responses. Thirteen participants (22%) indicated that they were looking forward to ‘joining the workforce’ (P16) ‘beginning my career’ (P45) and ‘being a qualified clinician’ (P21). One respondent was looking forward to putting on his/her ‘Band 5 uniform’ (P19). Although new challenges were anticipated by n = 7 respondents, they were looking forward to establishing their ‘own caseload’ (P38), ‘delivering high quality patient centered care’ (P37), and ‘experiencing new learning environments’ (P8). Other aspects students anticipated were working as part of a team (n = 8; 13%), being able to practice independently (n = 7; 11.66%) and establishing a routine (n = 3; 5%).

Some students felt prepared to implement the skills they had learned through hard work during their degree programme (n = 13; 22%) and looked forward to developing new skills and experience to broaden their knowledge (n = 12; 20%). One participant summarized the anticipation as follows: ‘finally to be able to put my skills I’ve learned over the past 3 years into practice’ (P53), while another stated, ‘I feel ready to take this next step and to learn and progress further whilst working’ (P25).

Theme 2: Opportunities for improvement

A key feature highlighted by 17% (n = 10) was improving their financial situation as a result of paid work and establishing a ‘stable income’ (P28). Additionally, ‘helping others’ (P16) and ‘improving the lives of the service users’ (P55) were anticipated positively by 18.33% (n = 11) of respondents. Three students (5%) viewed COVID-19 as an opportunity for them to join the workforce early, ‘being able to help in a meaningful way’ (P53).

Students’ fears of joining the workforce

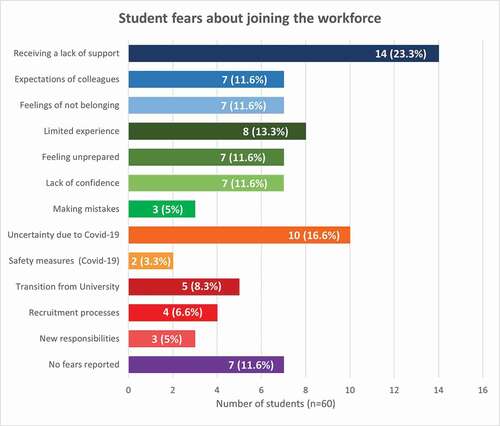

Of the 60 participants, the majority (n = 53; 88.4%) reported fears about joining the workforce (), whilst 11.6% (n = 4) reported having no fears and 6.6% (n = 3) provided a non-response.

Theme 1: Preparedness for transition from university to the workplace

The transition process caused anxiety for 53.3% (n = 32) of respondents. Five participants (8.3%) were fearful of the shift from university to the workplace, as they anticipated “leaving the safety net of university and having to go out” on their own (P20), whilst facing the prospect of becoming “isolated from other students” (P56). The recruitment process caused anxiety for 6.6% (n = 4), with concerns raised regarding interview preparation and the possibility of “not getting a permanent job” (P3). Receiving extra responsibilities was a worry for 5% (n = 3).

Eight participants (13.3%) reported fears relating to their limited clinical practice, “especially if it’s an area I have no placement experience in” (P10). One participant relayed fears of “not having adequate skills to be a valuable asset to the NHS” (P14), whilst another described the anticipation of “feeling like more of a hinderance than a help” (P22).

Some student anxieties appear compounded by feelings of unpreparedness, as highlighted by 11.6% (n = 7) of participants. One participant conveyed fears of “not being prepared for being in the workforce” (P55), whilst another similarly reported “not feeling like I’m ready” (P20). These concerns may consequently reduce student confidence, as 11.6% (n = 7) highlighted a lack of “confidence in my abilities” (P14) and 5% (n = 3) were fearful of making mistakes.

Fears relating to the support environment within the workplace were frequently reported. Twenty-eight participants (46.6%) expressed concerns about receiving insufficient support, high expectations from colleagues, and having feelings of not belonging.

Receiving insufficient support was a concern for 23.3% (n = 14) of participants, and many expressed anxiety about “being rushed through induction training if there are staff shortages” (P37). Whilst others reported worries that they “won’t be given time to adjust to the new role” (P10). Further student anxieties centered around their colleagues’ ability to provide sufficient supervision.

“I also worry my colleagues will be so busy/stressed that supervision may happen less than is ideal and that questions that I might have will be seen as a nuisance” (P4).

High expectations from colleagues was a worry for 11.6% (n = 7), with one participant capturing a recurring sentiment: “I’m worried I will be expected to know everything and slot in seamlessly” (P24). Similarly, another student (P28) described being anxious about increased “stress and managing expectations.”

Seven participants (11.6%) reported concerns regarding their sense of belonging within the workplace. Fears were centered around ”not fitting in to the team in which I’m placed” (P10), and “clashing with work colleagues” (P54).

Twelve (20%) participants raised concerns directly relating to the uncertainty and safety issues surrounding COVID-19. The unknown complexities of COVID-19 was anxiety provoking for 16.6% (n = 10), with fears about “starting my career during a pandemic” (P16), anticipated “changes to practice (P19) and “having to adapt to new protocols” (P46) being of particular concern. Surprisingly, only 3.3% (n = 2) had fears for personal safety due to COVID-19.

Perceived support needs

The majority of respondents (n = 50) felt they would benefit from support from their lecturers when making the transition into employment. Interestingly, only three out of 60 students cited COVID-19 as a specific area for support, desiring more information on ‘what to expect going into the work force at this time’ (P19) and the impact of COVID-19 on maintaining their professional identity. The majority of responses (n = 47) were grouped under three key areas: (i) employment support, (ii) advocacy and supervision; (iii) learning materials.

Some students believed support from lecturers would be valuable in providing information on job opportunities, the application and interview processes (n = 6; 10%) and on initial expectations within the workplace (n = 4; 7%), for example, providing guidance on ‘starting our professional journey and how to handle a new fast paced environment’ (P20).

Advice, reassurance, advocacy, mentorship, and supervision were cited by a considerable number of students (n = 23; 38%) as key aspects of support from their lecturers, including ‘access to support for any queries or concerns’ (P25), and providing ‘some sort of accountability with our managers to assure that we are getting regular or at least semi-regular supervision or an allocated mentor/buddy if this isn’t possible’ (P6).

Six participants stated that the availability of the university lecturers would be required, while three participants suggested that just knowing there was a named individual who could be contacted would be sufficient. Suggestions on mechanisms by which the university could provide such support included a weekly class online call, a weekly supervision telephone call with a lecturer, or an academic staff drop-in at the clinical setting.

Three students stated that continued access to their online undergraduate university learning materials would be helpful in moving forward and transitioning into employment.

The need for formal ‘induction’ was reported by five participants, to provide information on ‘how the team is run, assessments, procedures, etc.,’ (P19) and give demonstrations of each ‘new task I am asked to carry out’ (P10).

The need for daily support within the workplace was identified by 43 of the 60 respondents. Having a point of contact was considered important (n = 34), to ‘communicate any questions or queries’ (P14), ‘get advice’ (P5) and for ‘reassurance’ (P26). Reference was made to COVID-19 by two participants, in relation to being provided with information on up to date personal protective equipment (PPE) requirements and being made aware of action plans should a second wave occur. Participants mostly spoke of this daily contact as being an individual within the Trust, in a supervisory or mentorship role.

Further exploration of what students considered as the benefits of supervision showed that the most useful aspect was receiving feedback on their performance (n = 21; 38%), that is, having the ‘chance to speak about what’s going well and what needs focused on’ (P16). Others felt that supervision was helpful for general advice and support (n = 5; 9%), with some valuing the opportunity to discuss complex cases (n = 4; 7%), ask questions (n = 4; 7%) and set goals alongside their supervisor (n = 4; 7%).

Some innovative methods of support within the workplace were suggested by the participants, including the use of (i) a message board and (ii) an online App.

An alternative method of support was proposed by one participant who stated that a message board or forum to bring their queries would be beneficial because they were ‘conscious of asking colleagues too many questions when they’ll be incredibly busy’ (P6).

When asked about potentially receiving support online via an App, 49 out of the 60 students responded. Twenty-five students suggested an App would be useful for accessing practice resources on a wide range of topics including client conditions, and profession-specific assessment and treatment options. Four participants made specific reference to an App providing links to ‘useful videos for assessment or treatment techniques’ (P54).

The use of an App to facilitate discussion via a question and answer feature was suggested by 11 participants, providing opportunity to ‘contact others with queries or see responses to other people’s queries, like a discussion board’ (P10); some students (n = 3) stated that they would like to be able to ‘ask a question that will be answered by a professional’ (P13), while some specified peer discussion (n = 3). The ability to ‘have a private question box for support’ (P9) was also mentioned. Others felt an App could be a useful means to ‘share helpful tips’ (P23) or ‘an idea that helped me that day’ (P20), akin to a ‘thought for the day’ (P13). Being able to share personal experiences of entering the workforce via an App was also considered as a useful support (n = 3).

Two participants made specific reference to the provision of guides to help manage stress and stressful situations, and the use of an app for signposting (n = 5) to ‘relevant support services’ (P7). Provision of a contact list was suggested by eight participants, including contact details for University staff, Trust staff, and support services, while a news section was suggested by six participants, including details ‘on upcoming courses and training events’ (P14).

Discussion

COVID-19 poses a unique challenge for final year allied health students, as individuals navigate the already stressful experience of beginning work in the NHS during a major health crisis. The aim of this survey was to capture the viewpoints of healthcare students graduating early in preparation to join the pandemic workforce. This survey found that most participants reported fears about joining the workforce, which were predominantly related to inadequate support in the work environment. However, only a minority related their fears to the uncertainty of COVID-19 and most notably, only two participants raised concerns for personal safety. The survey also allowed students to position how they could best be supported by the university and the workplace. Suggestions were predominantly related to having a named person to provide mentorship, with ongoing support from the university to provide employment support, advocacy, and provision of learning materials.

Education marks an integral step in the development of professional identity, which continues throughout an individual’s career (Johnson et al., Citation2012). Tryssenaar and Perkins (Citation2001) explored the experiences of students transitioning to practice among occupational therapists and physiotherapists. Through the use of reflective journals completed by participants in their final year of placement and first year of practice, four stages were identified: transition, euphoria, and angst, reality of practice and adaptation. Indicative of the initial stages described by Tryssenaar and Perkins (Citation2001), participants in the current study were looking forward to beginning practice and using those skills developed over the course of their undergraduate education. Similarly, radiography final-year students reported formalizing their professional identity as important, marking a new stage in the development of their professional identity as a qualified member of staff (Naylor et al., Citation2016).

Although some participants in the current study were positive about beginning work, the majority of participants reported fears about what lay ahead. The transition from student to healthcare professional has been identified as a stressful period across professions (Harvey-Lloyd et al., Citation2019; Smith & Pilling, Citation2007; Tryssenaar & Perkins, Citation2001). In the current study, worries related to moving from the relative security of undergraduate education to uncertain employment, unfamiliar work environments and increased responsibility in their professional positions. Some participants reported concerns about their competency to begin practice. This feeling of inadequacy was also demonstrated in the study by Hodgetts et al. (Citation2007) where those students nearing graduation reported concerns about their practical skills and applicability in real-life work environments. Furthermore, recently graduated occupational therapists and physiotherapists have reported marked disparities between their experiences of clinical practice during their practice placements and in the real work environment (Morley, Citation2009; Stoikov et al., Citation2020). Programmes to ease this transition have been developed for allied health professionals (Banks et al., Citation2011; Smith & Pilling, Citation2007). A web-based programme developed in the UK was found to be useful for the development of clinical skills and confidence of recent graduates (Banks et al., Citation2011). However, these programmes are not implemented as standard, which raises concerns for how current students will manage in the midst of a pandemic.

Overall, participant worries predominantly related to receiving adequate support in the workplace. Supervision is an integral aspect of a student’s training, whereby practice educators facilitate the development of students’ clinical skills, supplemented by the observation, evaluation, and provision of student feedback (Stoikov et al., Citation2020). However, as students move to a qualified role, supervision often occurs less often, with expectations of increased independent working (Stoikov et al., Citation2020). In recognition of the importance for support and feedback in healthcare (Cantillon & Sargeant, Citation2008), participants reported the importance of a named contact to provide mentorship and feedback in the workplace. The ability to speak with mentors about clinical cases and receive feedback has been noted as an integral aspect in the development of competent therapists (Tryssenaar & Perkins, Citation2001). Nie et al. (Citation2020) reported increased psychological distress of healthcare care workers during the current pandemic, notably that of nurses working on the frontline. As the pandemic continues and health environments undergo rapid changes in response to COVID-19, healthcare trusts must put in place psychosocial supports available to all staff. In addition, universities must ensure their duty of care extends to allied health students embarking on practice placements and starting their professional careers in the midst of a pandemic.

Additional strategies reported by participants to ease this process included increased support from the university. As universities move to online teaching, students and recent graduates are restricted in how that support can be received. Strategies reported by participants included the use of online message boards which could provide peer support. Social support has been linked to increased resilience (Thompson et al., Citation2016), a necessary attribute with the increased anxiety students face resulting from the current pandemic, with a recent study linking social support to reduced anxiety during the COVID-19 outbreak in China (Cao et al., Citation2020). A scoping review with nurses suggested that technology could provide a valuable means of offering easily accessible support to improve emotional and social wellbeing (Webster et al., Citation2020). The use of smartphones and Apps for support and education by healthcare students has been previously reported in the literature. A qualitative study by Shenouda et al. (Citation2018) showed that final year medical students and junior doctors are using smartphones in their everyday practice, while a survey with student nurses (n = 232) showed that 86% would consider using Apps to support their learning in clinical practice and approximately half had already done so (O’Connor & Andrews, Citation2018). Some of the features recommended in the current study with allied health students were similar to those suggested by nursing students, including the use of Apps to provide audiovisual educational information, and a discussion facility to ask questions to clinicians within a chat room or discussion board for education and support (O’Connor & Andrews, Citation2018).

However, challenges to the implementation of Apps within healthcare education and training exist. This includes the negative attitudes of clinical staff and patients, with some regarding the use of mobile devices within healthcare settings as unprofessional (Colton & Hunt, Citation2016). Other challenges include infection control (O’Connor & Andrews, Citation2018), data protection (Colton & Hunt, Citation2016) and the limited pedagogical research on their use (O’Connor & Andrews, Citation2018). Further research is needed to address these issues and advance the formal integration of mobile devices and Apps within healthcare education.

Universities across the UK switched to online teaching in March 2020, some practice placements were canceled, and eligible final year allied health students were placed on the HCPC temporary register to begin practice. Interestingly, a minority of participants reported the uncertainty caused by COVID-19 as a reason for fear, with only two participants raising concerns for personal safety. Participant responses were captured as part of a survey and, as such, the reasons for this could not be explored further. However, it should be noted that six of the seven allied health student cohorts included in the survey had been on clinical placement during the COVID-19 pandemic, and this experience may have served to lessen their fears regarding transition to the workplace.

These findings are aligned with those reported by Courtier et al. (Citation2020), who analyzed the expectations of eleven radiography students transitioning to practice during the COVID-19 pandemic. Courtier et al. (Citation2020) found that most participants did not consider COVID-19 to pose a significant issue, and any concerns COVID-19 may pose to their health or that of their family members were not reported. Participants in both cohorts were of a comparable age (18–24 years) which could account for the similiarities in findings, with relatively low-risk factors to personal safety found for individuals in this age group (Verity et al., Citation2020). The COVID-19 pandemic appears to have simply added another complexity to student anxieties regarding transition, rather than become the sole focus of their concerns.

Limitations

The study sample size was small and only considered the views of allied health students in one university, and as such may not be representative of students across the UK and beyond. The participants were sampled as a cohort of allied health students hence their specific AHP background was not recorded. As a result, the distribution of responses based on profession could not be determined within the analysis. The inclusion of participant AHP background in future studies would be recommended to enable a richer exploration of potential differences in student experiences across the professional groups.

The response rate for the study was low at 26.5%, with the survey open to responses for 7 days. However, online survey rates are notoriously low among higher education students, with studies reporting response rates less than 20% (Van Mol, Citation2017). A national online survey which examined the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on final-year medical students estimated a response rate of 5.9%, with surveys distributed across 33 medical schools in the UK (Choi et al., Citation2020). Saleh and Bista (Citation2017) reported that graduate students were less likely to respond to surveys distributed toward the end of the school year, which was a factor in the current study. While the response rate is likely reflective of the rapidly changing landscape for students at this time, keeping the survey open for a longer period of time may support an increased response rate.

In comparison to other studies, which demonstrated distress associated with COVID-19 among healthcare workers (Braquehais et al., Citation2020), most of the participants in the current study were not directly concerned about COVID-19. Although the ethnicity of participants in the current study was not captured, universities in Northern Ireland are the least diverse in the UK (Gamsu et al., Citation2019), with predominantly white students (Higher Education Statistics Agency, Citation2021). The impact of COVID-19 has highlighted ethnic disparities (Williamson et al., Citation2020), and the capture of ethinicity would be recommended in a future study.

Recommendations for future research

This study indicated that the transition from student to practitioner continues to invoke anxiety and create uncertainty. Allied health departments should prioritize induction programmes for recently graduated therapists and negotiate opportunities for feedback and supervision. This study provides a snapshot of student viewpoints on the cusp of graduation and can help inform education programmes and support mechanisms to prepare students for beginning work during a pandemic.

Future research is warranted using interviews or focus groups to provide in-depth exploration of student viewpoints on COVID-19 as they progress into practice and to identify in detail how they can best be supported in their transition to qualified healthcare workers during a global pandemic. This study did not capture the concerns of students who were unable to begin practice, or finish practice placements, due to the increased risk for themselves and/or family members. Future study of this group is essential to allow universities and healthcare trusts to best meet their education and work needs.

Conclusion

This is the first published study to consider the viewpoints of a group of allied health professional students as they progress to practice during a pandemic in the UK. Findings suggest that students continued to raise concerns about this transition and if they would receive adequate support and supervision in the workplace. However, while these concerns were not explicitly related to the COVID-19 outbreak, until there is an effective, readily available vaccination with widespread uptake, universities, and workplaces must work to ensure they support individuals to safely engage with their education and practice.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Alison Porter-Armstrong

Dr Alison Porter-Armstrong is an occupational therapist and senior lecturer in Rehabilitation Sciences at Ulster University.

Jean Daly-Lynn

Mrs Jean Daly Lynn MSc, MSc, BA (Hons.) is a lecturer in Psychology in the School of Health Sciences at Ulster University.

Beverley Turtle

Dr Beverley Turtle is a research associate in stroke rehabilitation at Ulster University.

Warren Abercrombie

Mr Warren Abercrombie is an Occupational Therapist and project worker based in Enniskillen.

Aislinn McLean

Ms Aisling McLean is an Occupational Therapist based in Northern Ireland.

Suzanne Martin

Professor Suzanne Martin (PhD) is a professor of Occupational Therapy, and a Fellow of the Royal College of Occupational Therapists UK.

May Stinson

Dr May Stinson is a lecturer in Occupational Therapy at Ulster University.

References

- Banks, P., Roxburgh, M., Kane, H., Lauder, W., Jones, M., Kydd, A., & Atkinson, J. (2011). Flying Start NHS™: Easing the transition from student to registered health professional. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 20(23‐24), 3567–3576. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03796.x

- Braquehais, M. D., Vargas-Cáceres, S., Gómez-Durán, E., Nieva, G., Valero, S., Casas, M., & Bruguera, E. (2020). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of healthcare professionals. QJM: An International Journal of Medicine, 113(9), 613–617. https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcaa207

- Cantillon, P., & Sargeant, J. (2008). Giving feedback in clinical settings. BMJ, 337, a1961. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.a1961

- Cao, W., Fang, Z., Hou, G., Han, M., Xu, X., Dong, J., & Zheng, J. (2020). The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Research, 287, 112934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112934

- Choi, B., Jegatheeswaran, L., Minocha, A., Alhilani, M., Nakhoul, M., & Mutengesa, E. (2020). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on final year medical students in the United Kingdom: A national survey. BMC Medical Education, 20(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02117-1

- Clements, V., Fenwick, J., & Davis, D. (2012). Core elements of transition support programs: The experiences of newly qualified Australian midwives. Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare, 3(4), 155–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.srhc.2012.08.001

- Colton, S., & Hunt, L. (2016). Developing a smartphone app to support the nursing community. Nursing Management, 22(9), 24–28. http://dx.doi.org/10.7748/nm.22.9.24.s28

- Coppin, R., & Fisher, G. (2016). Professional association group mentoring for allied health professionals. Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management: An International Journal, 11(1), 2–21. https://doi.org/10.1108/QROM-02-2015-1275

- Courtier, N., Brown, P., Mundy, L., Pope, E., Chivers, E., & Williamson, K. (2020). Expectations of therapeutic radiography students in Wales about transitioning to practice during the COVID-19 pandemic as registrants on the HCPC temporary register. Radiography, 27(2), 316–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radi.2020.09.001

- Doody, O., Tuohy, D., & Deasy, C. (2012). Final-year student nurses’ perceptions of role transition. British Journal of Nursing, 21(11), 684–688. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2012.21.11.684

- Duchscher, J. B. (2008). A process of becoming: The stages of new nursing graduate professional role transition. The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 39(10), 441–450. https://doi.org/10.3928/00220124-20081001-03

- Edwards, D., Carrier, J., & Hawker, C. (2019). Effectiveness of strategies and interventions aiming to assist the transition from student to newly qualified nurse: An update systematic review protocol. JBI Evidence Synthesis, 17(2), 157–163. https://doi.org/10.11124/JBISRIR-2017-003755

- Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

- Gamsu, S., Donnelly, M., & Harris, R. (2019). The spatial dynamics of race in the transition to university: Diverse cities and White campuses in UK higher education. Population, Space and Place, 25(5), e2222. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.2222

- Gidman, J., McIntosh, A., Melling, K., & Smith, D. (2011). Student perceptions of support in practice. Nurse Education in Practice, 11(6), 351–355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2011.03.005

- Harvey-Lloyd, J. M., Morris, J., & Stew, G. (2019). Being a newly qualified diagnostic radiographer: Learning to fly in the face of reality. Radiography, 25(3), e63–e67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radi.2015.09.006

- Health and Care Professions Council. (2020a, March 19). COVID 19 our approach to temporary registration. Health and Care Professions Council. https://www.hcpc-uk.org/COVID-19/temporary-register/COVID-19-our-approach-to-temporary-registration/

- Health and Care Professions Council (2020b, May 4). Temporary Register Snapshot – 1 May 2020. Health and Care Professions Council. https://www.hcpc-uk.org/about-us/insights-and-data/the-register/temporary-register-snapshot-1-may-2020/

- Higher Education Statistics Agency. (2021, January 27). Higher Education Student Statistics: UK, 2019/20 - Student numbers and characteristics. Higher Education Statistics Agency. https://www.hesa.ac.uk/news/27-01-2021/sb258-higher-education-student-statistics/numbers

- Hodgetts, S., Hollis, V., Triska, O., Dennis, S., Madill, H., & Taylor, E. (2007). Occupational therapy students’ and graduates’ satisfaction with professional education and preparedness for practice. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 74(3), 148–160. https://doi.org/10.1177/000841740707400303

- Johnson, M., Cowin, L. S., Wilson, I., & Young, H. (2012). Professional identity and nursing: Contemporary theoretical developments and future research challenges. International Nursing Review, 59(4), 562–569. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-7657.2012.01013.x

- Melman, S., Ashby, S. E., & James, C. (2016). Supervision in practice education and transition to practice: Student and new graduate perceptions. Internet Journal of Allied Health Sciences and Practice, 14(3), 1. http://dx.doi.org/10.46743/1540-580X/2016.1589

- Morley, M. (2009). An evaluation of a preceptorship programme for newly qualified occupational therapists. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 72(9), 384–392. https://doi.org/10.1177/030802260907200903

- Naylor, S., Ferris, C., & Burton, M. (2016). Exploring the transition from student to practitioner in diagnostic radiography. Radiography, 22(2), 131–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radi.2015.09.006

- Nie, A., Su, X., Zhang, S., Guan, W., & Li, J. (2020). Psychological impact of COVID‐19 outbreak on frontline nurses: A cross‐sectional survey study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 29(21–22), 4217–4226. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15454

- O’Connor, S., & Andrews, T. (2018). Smartphones and mobile applications (apps) in clinical nursing education: A student perspective. Nurse Education Today, 69, 172–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2018.07.013

- Saleh, A., & Bista, K. (2017). Examining Factors Impacting Online Survey Response Rates in Educational Research: Perceptions of Graduate Students. Journal of MultiDisciplinary Evaluation, 13(29), 63–74. https://journals.sfu.ca/jmde/index.php/jmde_1/article/view/487/439

- Shenouda, J. E., Davies, B. S., & Haq, I. (2018). The role of the smartphone in the transition from medical student to foundation trainee: A qualitative interview and focus group study. BMC Medical Education, 18(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-018-1279-y

- Smith, R. A., & Pilling, S. (2007). Allied health graduate program–supporting the transition from student to professional in an interdisciplinary program. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 21(3), 265–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820701259116

- Stewart, R., & Liabo, K. (2012). Involvement in research without compromising research quality. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 17(4), 248–251. https://doi.org/10.1258/jhsrp.2012.011086

- Stoikov, S., Maxwell, L., Butler, J., Shardlow, K., Gooding, M., & Kuys, S. 2020. The transition from physiotherapy student to new graduate: Are they prepared? Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 1–11. ( Advance online publication). https://doi.org/10.1080/09593985.2020.1744206.

- Swift, A., Banks, L., Baleswaran, A., Cooke, N., Little, C., McGrath, L., Meechan‐Rogers, R., Neve, A., Rees, H., Tomlinson, A., & Williams, G. (2020). COVID‐19 and student nurses: A view from England. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 29(17-18), 3111–3114. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15298

- Tembo, D., Morrow, E., Worswick, L., & Lennard, D. (2019). Is co-production just a pipe dream for applied health research commissioning? An exploratory literature review. Frontiers in Sociology, 4, 50. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2019.00050

- Thompson, G., McBride, R. B., Hosford, C. C., & Halaas, G. (2016). Resilience among medical students: The role of coping style and social support. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 28(2), 174–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401334.2016.1146611

- Tryssenaar, J., & Perkins, J. (2001). From student to therapist: Exploring the first year of practice. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 55(1), 19–27. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.55.1.19

- Van Mol, C. (2017). Improving web survey efficiency: The impact of an extra reminder and reminder content on web survey response. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 20(4), 317–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2016.1185255

- Verity, R., Okell, L. C., Dorigatti, I., Winskill, P., Whittaker, C., Imai, N., Cuomo-Dannenburg, G., Thompson, H., Walker, P. G., Fu, H., & Dighe, A. (2020). Estimates of the severity of coronavirus disease 2019: A model-based analysis. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 20(6), 669–677. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30243-7

- Voorberg, W. H., Bekkers, V. J., & Tummers, L. G. (2015). A systematic review of co-creation and co-production: Embarking on the social innovation journey. Public Management Review, 17(9), 1333–1357. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2014.930505

- Webster, N. L., Oyebode, J. R., Jenkins, C., Bicknell, S., & Smythe, A. (2020). Using technology to support the emotional and social well‐being of nurses: A scoping review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 76(1), 109–120. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14232

- Williamson, E. J., Walker, A. J., Bhaskaran, K., Bacon, S., Bates, C., Morton, C. E., Curtis, H. J., Mehrkar, A., Evans, D., Inglesby, P., Cockburn, J., McDonald, H. I., MacKenna, B., Tomlinson, L., Douglas, I. J., Rentsch, C. T., Mathur, R., Wong, A., Grieve, R., Harrison, D., … Goldacre, B. (2020). Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature, 584(7821), 430–436. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2521-4