ABSTRACT

Children in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) have high levels of unmet mental health needs, especially in disadvantaged communities. To address this gap, we developed a child mental health service improvement programme. This was co-facilitated using interprofessional principles and values in four countries, South Africa, Kenya, Turkey and Brazil. Eighteen stakeholders from different professions were interviewed after six months on their perspectives on enabling factors and challenges they faced in implementing service plans. Participants valued the holistic case management approach and scaled service model that underpinned the service plans. Emerging themes on participants’ priorities related to service user participation, integrated care, and different levels of capacity-building. We propose that an integrated care model in LMIC contexts can maximize available resources, engage families and mobilize communities. Implementation requires concurrent actions at micro-, meso- and macro-level.

Introduction

In low- and middle-income countries (LMIC), prevalence rates of child mental health problems increase with deprivation and the presence of risk factors, for example, to approximately 20% in settlement areas, and 40–50% in orphanages or among refugee and street children, in contrast with 10% in the general population globally (Reiss, Citation2013). Unlike high-income countries though, there is often lack of designated child mental health policy and specialist resources (World Health Organisation [WHO], Citation2016). Other barriers include the stigma of mental illness, parental disengagement because of competing economic priorities, child labor and other forms of exploitation, and limited availability of culturally adapted interventions (Getanda et al., Citation2017).

As specialist child mental health services are sparse in LMIC, psychosocial support is variably provided by a range of institutions such as schools, primary health facilities, child and youth centers, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and community volunteers or paraprofessionals. Psychosocial response is often combined with other functions such as child protection, health promotion and life skills training (World Health Organisation, Citation2014). Interventions are largely provided within professional, agency or community volunteer groups, and are rarely interprofessional in nature for developing collaborative working practices (Arora & Bonhenhamp, Citation2016; Odegard, Citation2009). Staff providing these services are usually poorly resourced and not adequately trained to provide psychosocial support; and consequently, are not able to meet the wellbeing and mental health needs of children (Patel et al., Citation2018).

For these reasons, some models were developed in recent years to plan, improve, and evaluate services in LMIC low-resource contexts (White et al., Citation2016). These models were informed by several theoretical frameworks. The development of a Theory of Change, for example, can help pre-define the steps through which service plans are expected to achieve impact (Brewer et al., Citation2016). These steps are especially important for the design and evaluation of complex interventions (Craig et al., Citation2008) that require collaborative health and social care responses (Steenkamer et al., Citation2020). Implementation science, in particular realist evaluation, has influenced the evaluation of global public health service plans in determining the context, mechanisms, and outcomes (CMOs) through which these can be implemented and derive benefits in different sociocultural contexts (Mirzoev et al., Citation2015). Co-production with stakeholders is central to all these frameworks (Ward et al., Citation2016).

Service improvement plans in LMIC have been implemented and evaluated in education, physical and adult mental healthcare (Bright et al., Citation2017; Kapur & Crowley, Citation2008). These largely considered service users’ holistic needs, by integrating different professional perspectives to maximize resources on the ground. For example, early childhood service plans in Indonesia integrated education, health, and capacity-building components (Aboud et al., Citation2016). De Silva et al. (Citation2016) evaluated mental healthcare plans in five LMIC, to understand which programmes “work” and why, to inform decisions on scaling up. Although several child psychosocial interventions have been designed for LMIC post-conflict and disadvantage settings, to date there is limited knowledge on how systemic changes could improve children’s mental health in these contexts.

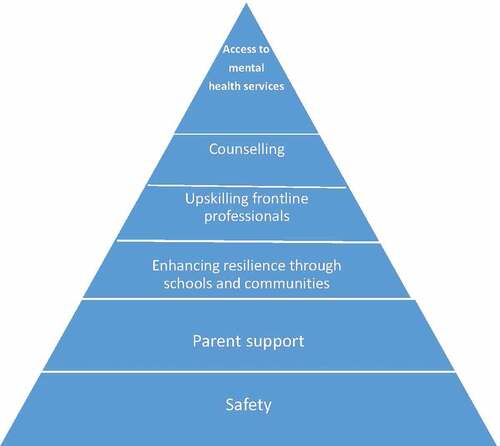

To this effect, a service improvement programme was developed by the research team, to bring systemic changes in child mental health service provision in LMIC that go beyond individual practice. Its objectives were to identify target areas of deprivation, establish interprofessional networks, map current strengths and gaps in resources, co-produce service plans with local stakeholders, and implement these service plans in the target areas (Vostanis, O’Reilly et al., Citation2019). Participating agencies worked together along six domains of a child mental health service improvement framework, which included: how to improve children’s safety, support parents and caregivers, promote children’s resilience through schools and communities, upskill professionals and community volunteers, provide counseling, and improve access to mental health services. In an earlier study, service improvement plans were co-produced with 54 stakeholders from different professions in three LMIC (Kenya, Turkey and Brazil) through participatory workshops (Vostanis, Eruyar et al., Citation2019). Following these workshops, service plans were implemented over a period of six months. In this phase of this service improvement process, researchers sought to understand the extent to which service plans were implemented on the ground, and which factors may have facilitated or hindered their implementation, with particular focus on interprofessional working and collaborative practice. In this paper we share findings of this process.

This study aimed to address the following research questions on the perspectives of LMIC stakeholders who had implemented child mental health service improvement plans over six months:

Which service plans components could be implemented on the ground?

Which factors facilitated or hindered their implementation?

To what extent were the service plans implemented interprofessionally?

Method

Context of child mental health service improvement plans

Service improvement plans were co-produced through a similar approach in four LMIC. In three of these countries (Brazil, Turkey, and Kenya) participatory workshops had been conducted as part of the previously quoted study (Vostanis et al., 2019a). Later, an additional site was included in South Africa. In all countries, a host NGO co-ordinated the co-production of service plans through a participatory workshop. The target group of the service improvement plans were organizations rendering psychosocial interventions to vulnerable children and young people living in areas of disadvantage, or resource-constrained informal settlements (sometimes referred to as slums – Kenya, or favelas – Brazil). All target areas were urban, in the respective cities of Rio de Janeiro, Istanbul, Nakuru and Johannesburg. The host NGO identified all agencies in contact with children in each area, irrespective of the extent of local resources. These agencies spanned schools and other education services, social care, health, NGOs, community and religious or faith-based groups. Each agency identified key representatives, i.e., professionals, managers, community, or religious leaders, who were considered as senior or autonomous in implementing the service plans.

The child mental health service improvement framework was co-adapted with each NGO for their local sociocultural context and needs, although the structure of the workshops was similar across the four sites (;Vostanis, Citation2019). Each workshop was co-facilitated by a host NGO professional and the first author. An average 25 participants attended each workshop (total n = 98). The workshops adopted an interprofessional stance designed, so that participants felt safe and supported to share and interact, and to learn ‘with, from and about one another,’ in order to assimilate their common approaches to service planning (World Health Organization, Citation2010 p. 6). Participants worked in mixed interprofessional small groups to map current resources and gaps in their area, and to jointly articulate priorities within their vision to transform local services. Based on this scoping activity, participants were presented with the service improvement framework, and were asked to co-produce service plans that were realistic, achievable, and short-term (six months) on each of the service improvement framework domains. These service plans had to be framed in an interprofessional context to enable integrated working to flourish. For example, one task was to ask groups to think about how all local agencies could enhance children’s safety together (such as identifying a child protection representative for their community or establishing a joint forum), and within their organization (for example, by instigating child protection policy in their school). Although service plans were formulated to meet local needs, overarching themes were explored across all sites.

Participants

Stakeholders included for participation in this study, were: five participants from each country; who had attended the participatory workshop six months earlier; worked in a capacity that could locally influence implementation on the ground; and represented the education, welfare and health and community sectors, as far as possible, at each site. Three rather than the intended five stakeholders were reached in Brazil, because of eruption of violence in the selected area of favelas during the period of recruitment. The sample thus comprised 18 participants. Their professions, were: teacher (n = 3), guidance and counseling teacher (n = 2), medical family practitioner (n = 1), care worker (n = 2), pastor (n = 1), life coach (n = 1), psychologist (n = 2), and manager/coordinator (n = 6). The total sample size was considered sufficient to secure sampling adequacy and reach coding saturation (Hennink et al., Citation2017) across countries, but not within countries. This was in part due to the professional status of the participants having some degree of educational similarity, and in part due to the combined inductive and deductive processes (see below) providing a degree of structure to the analysis, which meant less interviews were needed (Braun & Clarke, Citation2019). The study was approved by the University of Leicester Research Ethics Committee. Data was collected through semi-structured interviews, which took place in the intervieweees’ language. Audio recordings were transcribed and translated into English by the local researchers who had conducted the interviews.

Data analysis

The data was subjected to combined inductive and deductive thematic analysis, using the steps suggested by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006). This was congruent with the open nature of the research questions and the goal of identifying common issues at stake across country professional groups. A layered approach to coding and analysis was undertaken, consistent with the three levels of categorization proposed by Boyatzis (Citation1998), i.e. first (descriptive coding), second (conceptual categorization) and third order (thematizing) of data. Throughout the analytic process, research meetings were held to collate coding frameworks, discuss discrepancies and make refinements. The NVivo 12 programme was used to facilitate coding.

Results

Three themes emerged in relation to the research questions of the study. These themes and subthemes are summarized in and considered in more detail below.

Table 1. Emerging themes and subthemes on the implementation of child mental health service transformation training

Theme 1: service user participation

Engaging and involving children, youth, parents, and communities was viewed as essential by participants in embracing, co-producing and implementing service plans. Individual, family and community understanding of different concepts and beliefs surrounding mental health and illness was thus essential in seeking help, and in adapting service plans and interventions.

We are having trouble with families, as they are not keen to get psychosocial support. Although there is a free therapist and families admit that they need this support, they don’t show up or cancel the appointment at the last minute. They think that they are gonna be called ‘sick’ if their neighbours learn that they are going for therapy … there is a lack of trust as well, and it is hard to engage with children when their family do not show up. Teacher, Turkey.

Mental health and parenting concepts were linked to perceptions of what could constitute a mental health problem, hence the need for early recognition and seeking help. Some parents could not identify concerns early or did not relate those to their parenting role and responsibilities, particularly if their attachment relationships with their child was disrupted. This barrier was mainly reported by social care professionals from Turkey and South Africa who worked in welfare settings, therefore, were more likely to recognize attachment-related problems such as aggression.

If you check our children who are having mental issues, you might find their diagnosis is reactive attachment disorder. This means they could not attach to anyone … now they are reacting to the love they are trying to get from the care workers who are not even parents to them, and it becomes complicated and everything. Social worker, South Africa.

For some families, lack of parental presence and nurturing appeared to be linked to socioeconomic hardship; with parents unable to adeqauately attend to their children’s needs. Similarly, working long hours also meant they were not able to engage in and adhere to service plans; particularly when services failed to acknowledge difficulties and the impact of disadvantage in how they were set up. It was also interesting to note that across all contexts, and confirmed by the literature (e.g., Van Ee et al., Citation2013), fathers were particularly hard to engage.

And maybe let me say, some guardians there those who also may not be able to support in one way or another, either financially or emotionally. They have just given up on their children. Teacher, Kenya

You call for a simple like parenting, they don’t show up, like the last time, we organise together, they all say no. They’ll say we are coming, then the day comes, only one or two parents will show up. Social worker, South Africa

In addition to the stigma of mental illness, some parents feared that professionals would report them to authorities for maltreatment or neglect. Overcoming these perceptions and acting when children needed to be protected required close interprofessional collaboration, and communication with joined up thinking. Unless these initial reservations were addressed and resolved, parents were reluctant to accept help and, crucially, were reluctant to meaningfully engage in therapeutic interventions. This was interpreted by some stakeholders as resistance to tackle longstanding parenting difficulties.

Their lives have been formalized in a certain format, and they don’t want to bend like they don’t want to bend, it’s like we have always done it this way. That’s one of the major challenges. Pastor, Kenya

Where flexibility comes in, because if they’re rigid in the way that they think and the way that do things, they’re not going to be flexible enough to listen to other peoples’ ideas, which would help in implementing a specific plan of action … they’re conditioned, are not necessarily going to take it up. Because you can try and challenge myths and beliefs around certain things, but I don’t think that all people are open to taking those, you know, changes and thought patterns. Psychologist, South Africa

Involving children and families from the outset was central to the help-seeking process, that is, from recognition of a need, to asking for and accepting help, attending assessment appointments, and completing interventions.

The parents were struggling with the certain child, who is also low functioning. So, I started also to engage with the parent to make her understand the child better. Care worker, South Africa.

Through listening to the families, we can perceive a better attendance to their needs, as well as their involvement in the actions of the institutions … survey of service demands by listening to the families of the children and adolescents participating in the projects, comparing it with the local offerings. Checking the correspondence of what is demanded and what is offered. Coordinator, Brazil

Professionals often had to seek assistance from community elders or leaders to overcome stigma and to engage parents. They thus viewed community resources as essential components of the interprofessional network, because of their local contextual knowledge, trust, and respect among families.

So, being friendly to these learners (children) coming close to me and the parents, then we had to discuss … in my institution, even the administration I had to involve them, and see the sense what I was training the children back to work. Even our church, the same applied. We tried to talk to the parents and the learners together with our church elders. So, at least everybody now is applying. Guidance and counsellor teacher, Kenya

Theme 2: interprofessional practice

Participants from all four LMIC sites reported that they adopted a holistic and interprofessional approach in implementing service plans with users. This was perceived as important in several activities. In the context of improving service provision, understanding children’s needs from different professional perspectives facilitated better recognition, assessment, and care.

So, the mother was giving us the information to say, okay, we moved from this area, there was no school for him, I had challenges with the school. So, when … I’m doing assessment, it really helps me to look in detail. Social worker, South Africa

To provide holistic care, respondents realized the importance of interagency collaboration on the ground. They defined collaborative care as involving different health and social care professions, teachers, governmental and non-governmental bodies. Collaboration was particularly valued for children with complex needs, who were at high risk of developing mental health problems, such as those with histories of maltreatment, criminality and drug use.

By working with local actors to strengthen bonds and to assist in possible referrals to different health agencies, either at the local community office or even referring for more specific treatments, these actions have been reinforced by these partnerships. Teacher, Brazil.

We collaborated with other NGOs on the risk for child mental health, we had meetings with the staff of other NGOs who are working with children … and we collaborated with municipalities as well, we used their sports halls. So, parents, children, government and NGOs worked together. Project coordinator, Turkey

Stakeholders, however, also acknowledged challenges in initiating and sustaining joint working. In particular, they were mindful of the lack of enthusiasm and interest from some partners. Although this was not attributed to any particular profession or agency, it was a detrimental factor in forming collaborations.

Not all of them have the heart for the, they don’t have a passion for the children. Executive director, Kenya

Everyone in the multidisciplinary approach does not show the same enthusiasm, or they have a lack of awareness on the importance of this issue, so they do not make contact with you. Medical doctor, Turkey

Within this theme on interprofessional care, stakeholders framed their practice and relationships with other agencies within a service model that made effective use of limited resources. To this effect, they endorsed the scaled care approach proposed by the service framework.

I think we now started not just teacher training, but looking at implementing case work … so, for example, in the psychosocial pyramid that you have, the most severe cases are at the top, we’re making sure some of those cases are followed-up, so each staff have their own casework, which is something new to the programme. Project manager, Turkey

Theme 3: capacity-building

Stakeholders’ realization of children’s needs and service gaps, and their preferred service response, as described in Themes 1–2, led to the identification of priorities for capacity-building. Interestingly, they largely approached these priorities in an interprofessional context. Addressing stigma, negative attitudes and limited knowledge were considered essential for service plans to be implemented. These were particularly connected to help-seeking and parent engagement. Since the participatory workshops, some stakeholders had thus developed psychoeducation programmes for parents.

We have used the topics from that workshop when we had meetings with mothers, to increase their awareness about environmental factors that might create risks for children, and also about the child mental health. Project coordinator, Turkey

Participants indicated that awareness raising should not only target parents, but also professionals and policy makers. Stakeholders suggested that these groups may also carry their own beliefs, as well as fears in relation to mental health. These can underpin practitioners’ lack of motivation, and partially the lack of commitment by policy makers and budget holders. Consequently, awareness campaigns at different levels should be co-ordinated and targeted to appropriate stakeholders. These should address whole interprofessional groups such as within schools, by sensitizing administrators and other staff without teaching or practice responsibilities.

We need to increase awareness to every single people in the community … so, we need to organise trainings to raise the awareness. Psychologist, Turkey.

Then another possible suggestion l can give is concerning the sensitisation not only for the guidance and counselling teachers … it actually should be holistic, that’s from the parents, the guardians, the teachers in that particular institution, and even the subordinate staff, because they are the people who are interacting with the learners. Yes, and once they get to have that knowledge, they will be able to handle such cases. Because, maybe I can handle the child well … when he goes to another teacher he is mishandled, then he goes again back to the stage where he was initially. Teacher, Kenya

Among professionals, lack of awareness was often related to competencies. Participants highlighted that limited child mental health knowledge and skills within different staff roles was a potential pitfall in interprofessional care. Hence, upskilling professionals outside the mental health field had been a priority among their service plans. Most participating stakeholders expressed that some level of mental health training had since been provided to teachers, social workers, and caregivers in residential settings.

We looked at teachers and how we could upskill the teachers, and giving them more awareness and ways to identify the children who might have experienced trauma. Project manager, Turkey.

In initiating training in their areas, participants identified knowledge gaps and organizational barriers. Professionals often lacked the capacity to apply knowledge to practice, as well as to connect different theories and required skills for assessment and intervention purposes. It appeared as though this limitation varied, depending on their background, professional education and experience.

Not being skilled enough to understand, it’s when I’m doing emotional assessment, what am I doing, what am I gathering, which information is right to get it from the child or from the family. Those are some of the barriers, some of the challenges. Social worker, South Africa

It was acknowledged that the training offered needed to be extended within and across organizations. Continuing professional development and opportunities for shared learning were valued. Competing time pressures could be alleviated by booster sessions, supporting resources and blended learning. Some participants wished to extend shared learning nationally and internationally. This would empower them with the knowledge that they were adopting similar and evidence-based approaches in their practice, but applied in different sociocultural contexts. Digital technology offered new opportunities across systems.

I think, to see the examples from abroad could improve the workshop, I would like to see like case reports. We could discuss in groups on how to apply the lessons from these case studies to Turkey. Project coordinator, Turkey

Beside parent- and staff-related challenges, participants also reported organizational barriers. As anticipated from the literature, lack of resources within and across organizations due to shortage in governmental support were commonly reported. This proved demoralizing in the implementation, and especially the sustainability of service plans. Effective interprofessional practice and collaboration required commitment and support from agencies involved, which were often not forthcoming, because of competing pressures for staff time. NGOs contributed to a substantial proportion of the workload, which often compensated for limited input from statutory services such as child protection and specialist mental health provision. Teachers felt similarly unsupported in working beyond their educational remit.

Municipalities fall short in providing support for NGOs, as there are numbers of NGOs. So, you need to improve your relationship with the authorities to get support from them. As there are numbers of disadvantaged children, the resources are not enough. Project coordinator, Turkey.

The government cannot supply, even if they give maybe a third of what is needed in school. So, resources sometimes they are scarce. Teacher, Kenya

In addition to limited skills in relation to children’s mental health, managerial capacity and expertise often hindered the implementation of action plans. This was particularly raised in relation to NGOs from Turkey. Stakeholders stated that NGO managers did not often have sufficient knowledge, which resulted in inefficient resource management.

The managers do not know how to use volunteers actively, there are thousands of University students who want to work voluntarily, but NGOs do not know how to use this resource. Medical doctor, Turkey

Although interprofessional collaboration was valued, stakeholders were active drivers in initiating and especially sustaining partnerships. Networks often relied on individual relationships at local level, as advocated by relational coordination theory (Gittell et al., Citation2013). These were more effective when needs-led, i.e. when they were informed by children’s multiple needs.

I think it was networking. Because, for me it was looking at, who else is out there? Who else can make a difference in this young person’s life? And just go out sort of the institution as well, this is what the institution is doing. But then, who else can we draw in to assist? So, the external social worker had to be drawn in, the ward counsellor had to be drawn in, the neighbours, the former neighbours in the community had to be drawn in. Mummy’s friends had to be drawn in … so, whoever can, other service providers that can actually help us. Manager, South Africa

For some stakeholders, the service framework helped them to focus beyond short-term goals and crisis-driven responses, by developing long-term care plans in their practice. These invariably involved other professionals, if children were to sustain and build on early gains. Individual care plans were, however, not mirrored by sustainability strategies at a systemic level.

Start with ....and so, it really gave me some impetus to be able to continue to do what I was doing, and I have come up with various strategic plans in the church that target young people. Pastor, Kenya

And now there’s a plan, he’s going to rehab, because he was still here, he admitted he was still smoking dagga outside [laughing]. So, he’s going to go to rehab. And when he comes back, he will go to vocational training, he can still visit his sister and we’re rebuilding the shack. Care manager, South Africa.

In relation to learning style and format, most participants favored case-based training, which comprised examples from real life. They expressed a wish for balance between theory and application of cases across different settings. The discussion of case scenarios within small interprofessional groups was valued.

These trainings should … include case reports to be remembered. For example, group work was super helpful in our training. I would like to learn more about case reports, because there are different kind of trauma, and we do not know these. Medical doctor, Turkey.

Discussion

In this study we explored how stakeholders from different professions operating in LMIC settings had implemented child mental health service improvement plans over a period of six months. Their interprofessional perspectives were important in understanding contextual enablers and barriers to inform a Theory of Change for scaling up and further implementation. Participants’ inter-linked priorities across the four countries related to engaging families and mobilizing communities, integrating care, and establishing various levels of capacity-building. In view of these findings in the context of children’s extent of unmet mental health needs in LMIC, we would argue that integrated care systems are particularly pertinent and consistent with available theories, international guidelines, and evidence.

Integrated care systems have been shown to lead to improved access, use of resources, quality of interventions, and sustainable strategies for vulnerable groups that usually require joined up thinking and working between health, welfare, and other agencies such as education (Steenkamer et al., Citation2020). Integrated care systems are especially appropriate for children with complex needs (Kingsnorth et al., Citation2013), and have been endorsed by the World Health Organization across different LMIC health contexts (Briggs & de Carvalho, Citation2018). Primary mental health care stakeholders in six LMIC suggested that integrated care models should be synergistic with and aim to strengthen existing care systems (Petersen et al., Citation2019). Implementation should thus concurrently address micro- (professionals and service users), meso- (organizations) and macro-level (contextual) factors (Threapleton et al., Citation2017). Capturing stakeholder perspectives in this study was, therefore, important in understanding enablers and barriers to the future implementation of service improvement plans.

Despite specialist services constraints, in LMIC there are informal community supports and resources that can be accessed and maximized. Indeed, international guidelines emphasize the importance of strengthening community-based care (World Health Organization, Citation2013). Communities carry unique expertise, knowledge of issues on the ground, access to networks, and credibility with children and families. This knowledge can contribute to awareness and mental health promotion campaigns, integration of psychosocial interventions within existing community forums, and establishment of a pool of community volunteers or paraprofessionals. Communities are thus central within a service model informed by interprofessional collaborative care and relational coordination of shared goals, knowledge, and respect (Gittell et al., Citation2013). For this reason, community and religious leaders, peer educators/mentors and paraprofessionals should be considered as equal drivers in LMIC service improvement plans; with the term “para” professional maybe requiring an extension of interprofessional definitions used in western systems.

We would argue that, even the barriers to implementation that were identified by stakeholders can best be overcome through an integrated care systems approach that builds secure and trustworthy relationships, although this is recognized as difficult. For example, challenges for involving parents are consistent with previous evidence, and are related to multiple factors such as poverty, stigma, parenting capacity and child-parent attachment relationships (Getanda et al., Citation2017). These factors can clearly not be addressed by any single agency. Although NGOs are central to providing family support in disadvantaged settings, their strategy, operation, and staff education are often provided in silo from statutory services, so that each does not know about their similar worries and concerns. Collaborative practice between communities, statutory and non-statutory stakeholders should instead be present at all levels of service improvement. Participants in this study proposed such a collaborative approach to designing and delivering awareness and training programmes tailored to the needs of community, universal and specialist providers.

Stakeholders reported that they had initiated interprofessional networks on the ground, even without organizational buy-in, usually based on individual relationships. Working on daily joint goals has been associated with enhanced communication and collaborative practice (Hustoft et al., Citation2018), thus beginning to instill a “bottom-up” integrated care ethos across agencies. Policymakers and managers should be engaged in parallel in endorsing collaborative organizational principles, based on evidence that higher relational coordination leads to higher quality and efficient care (Gittell et al., Citation2013). Other identified enablers of integrated global health care systems include a political framework, legislation, joint care pathways and joint service records (Mickan et al., Citation2010). Integrated care principles and values-based practice should be engrained through strategic “train-the-trainer” programmes, which can ensure sustainability of benefits (Merriman et al., Citation2020). Future collaborative leaders can thus be equipped early with skills such as thinking systemically, building and re-building relationships, nourishing self-actualization, and adopting a range of problem-solving approaches (Vaggers & Anderson, Citation2021).

These findings need to be interpreted within the limitations of this study. Although we obtained a sufficient total sample of participants, the sample size within each country did not allow us to contrast stakeholders’ perspectives across the four sites. A wider range of settings, professionals and, crucially, children and parents, would have enhanced the generalizability of the findings. Future evaluation of implementation of service plans could include quantitative data on service activity variables such as number of referrals, time response and sessions attended within each agency. Service plans implementation would have been aided by supervision and booster sessions. Crucially, these preliminary findings should lead to the development of a Theory of Change (ToC) of child mental health service improvement, and the evaluation of its contextual factors-mechanisms-outcomes. Both cross-country and country-specific ToC could then be refined (Brewer et al., Citation2016).

Conclusion

Stakeholders from different LMIC valued integrated child mental health care in the implementation of service improvement plans, especially adopting a holistic approach in case management and a scaled service model with efficient use of limited resources. Service users and communities are essential drivers in this process and should be central to integrated care systems in LMIC contexts of disadvantage. Strategic planning should address micro-, meso- and macro-level factors.

Ethics approval

University of Leicester Psychology Research Ethics Committee, reference 19395

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all participants. We thank the NGOs for hosting the training programme and facilitating the study: Hayat Foundation, Turkey; Kids Haven, South Africa; Friendly Action Network, Kenya; and Associação pela Saúde Emocional de Crianças, Brazil.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Seyda Eruyar

Seyda Eruyar is Assistant Professor and Head at the Department of Psychology, Necmettin Erbakan University (NEU) in Turkey. Prior to joining NEU, Seyda completed her MSc at the University of Nottingham, and PhD at the University of Leicester, UK. Her research interests lie in the area of mental health prevention and research methods in psychology, ranging from theory to design interventions.

Sadiyya Haffejee

Sadiyya Haffejee is a Senior Researcher at the Centre for Social Development in Africa, at the University of Johannesburg in South Africa. She also acts as the therapy centre manager at a Child and Youth Care Centre, and has an interest in children and youth exposed to adverse childhood experiences and resilience.

ES Anderson

ES Anderson is Professor Interprofessional Education at the University of Leicester in the UK. She has developed innovative educational interventions in relation to disadvantage and team working. She has international and national research collaborations on IPE and is currently Patient Safety Lead for the Medical School.

Panos Vostanis

Panos Vostanis is Professor of Child Mental Health and Director of the World Awareness for Children in Trauma (WACIT: www.wacit.org), which provides interprofessional capacity-building and interventions in Majority World Countries. He has research expertise on the impact of trauma on child mental health, and the evaluation of interprofessional interventions and services.

References

- Aboud, F., Proulx, K., & Asrilla, Z. (2016). An impact evaluation of Plan Indonesia’s early childhood program. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 107(4–5), e366–e372. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.17269/CJPH.107.5557

- Arora, P., & Bonhenhamp, J. (2016). Collaborative practices and partnerships across school mental health and paediatric primary care settings. Advances in School Mental Health Promotion, 9(3–4), 141–147. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1754730X.2016.1216684

- Boyatzis, R. (1998). Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. Sage.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Brewer, E., Lee, L., De Silva, M., & Lund, C. (2016). Using theory of change to design and evaluate public health interventions: A systematic review. Implementation Science, 11(1), 63. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0422-6

- Briggs, A., & de Carvalho, I. A. (2018). Actions required to implement integrated care for older people in the community using the World Health Organization’s ICOPE approach. PLoS ONE, 13(10), e0205533. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0205533

- Bright, T., Felix, L., Kuper, H., & Polack, S. (2017). A systematic review of strategies to increase access to health services among children in low and middle income countries. BMC Health Services Research, 17(1), 252. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2180-9

- Craig, P., Dieppe, P., Macintyre, S., Michie, S., Nazareth, I., & Petticrew, M. (2008). Developing and evaluating complex interventions: New guidance. MRC.

- De Silva, M., Rathod, S., Hanlon, C., Breuer, E., Chisholm, D., Fekadu, A., Jordans, M., Kigozi, F., Petersen, I., Shidhaye, R., Medhin, G., Ssebunnya, J., Prince, M., Thornicroft, G., Tomlinson, M., Lund, C., & Patel, V. (2016). Evaluation of district mental healthcare plans: The PRIME consortium methodology. British Journal of Psychiatry, 208(s56), s63–s70. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.114.153858

- Getanda, E., O’Reilly, M., & Vostanis, P. (2017). Exploring the challenges of meeting child mental health needs through community engagement in Kenya. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 22(4), 201–208. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12233

- Gittell, J. H., Godfrey, M., & Thistlethwaite, J. (2013). Interprofessiional collaborative practice and relational coordination: Improving healthcare through relationships. Journal of Interprofessiomal Care, 27(3), 210–213. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2012.730564

- Hennink, M., Kaiser, B., & Weber, M. (2017). Code saturation versus meaning saturation: How many interviews are enough? Qualitative Health Research, 27(4), 591–608. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732316665344

- Hustoft, M., Hetlevik, O., Abmus, J., Storkson, S., Gjesdal, S., & Biringer, E. (2018). Communication and relational ties in inter-professional teams in Norwegian specialized healthcare: A multicentre study of relational coordination. International Journal of Integrated Care, 18(2), 9. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.3432

- Kapur, D., & Crowley, M. (2008). Beyond the ABCs: Higher education and developing countries. Center for Global Development Working Paper 139. Retrieved June 2021. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.22139/ssrn.1099934

- Kingsnorth, S., Lacombe-Duncan, A., Keilty, K., Bruce-Barrett, C., & Cohen, E. (2013). Inter-organizational partnership for children with medical complexity: The integrtated complex care model. Child: Care, Health and Development, 41(1), 57–66. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12122

- Merriman, C., Chalmers, L., Ewens, A., Fulford, B., Gray, R., Handa, A., & Westcott, L. (2020). Values-based interprofessional education. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 34(4), 569–571. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2020.1713065

- Mickan, S., Hoffman, S., & Nashmith, L. (2010). Collaboarative practice in a global health context: Common themes from developed and developing countries. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 24(5), 492–502. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/13561821003676325

- Mirzoev, T., Etiaba, E., Ebenson, B., Uzochukwu, B., Manzano, A., Onwujekwe, O., Huss, R., Ezumah, N., Hicks, J. P., Newell, J., & Ensor, T. (2015). Study protocol: Realist evaluation of effectiveness and sustainability of a community health workers programme in improving maternal and child health in Nigeria. Implementation Science, 11(1), 83. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0443-1

- Odegard, A. (2009). Time used on interprofessional collaboration in child mental health care. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 21(1), 45–54. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820601087914

- Patel, V., Saxena, S., Lund, C., Unutzer, J., Bolton, P., Chisholm, D., Collins, P. Y., Cooper, J. L., Eaton, J., Herrman, H., Herzallah, M. M., Huang, Y., Jordans, M. J. D., Kleinman, A., Medina-Mora, M. E., Morgan, E., Niaz, U., Omigbodun, O., Prince, M., UnÜtzer, J., & Thornicroft, G. (2018). Lancet Commission on global mental health and sustainable development. Lancet, 392(10157), 1553–1598. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31612-X

- Petersen, I., van Rensburg, A., Kigozi, F., Semrau, M., Hanlon, C., Abdulmalik, J., Kola, L., Fekadu, A., Gureje, O., Gurung, D., Jordans, M., Mntambo, N., Mugisha, J., Muke, S., Petrus, R., Shidhaye, R., Ssebunnya, J., Tekola, B., Upadhaya, N., Lund, C., & Thornicroft, G. (2019). Scaling up integrtated primary mental health in six LMIC. BJPsych Open, 5(5), e69. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2019.7

- Reiss, F. (2013). Socieconomic inequalities and mental health problems in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Social Science and Medicine, 90, 24–31. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.04.026

- Steenkamer, B., Drewes, H., Putters, K., van Oers, H., & Baan, C. (2020). Re-organising and integrating public health, social care and wider public services: A theory-based framework for collaborative adaptive health networks to achieve the triple aim. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy, 25(3), 167–201. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1355819620907359

- Threapleton, D., Chung, R., Wong, S., Yeoh, E. K., Wong, E., Chau, P., Woo, J., & Chung, V. C. H. (2017). Integrated care for older populations and its implementation facilitators and barriers: A rapid scoping review. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 29(3), 327–334. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzx041

- Vaggers, J., & Anderson, E. (2021). An essential model for leaders to enable integrated working to flourish: A qualitative study examining leaders of Children’s Centres. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 1–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2021.1897553

- Van Ee, E., Sleijpen, M., Kleber, R., & Jongmans, M. (2013). Father involvement in a refugee sample: Relations between posttraumatic stress and caregiving. Family Process, 52(4), 723–735. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12045

- Vostanis, P. (2019). World awareness for children in trauma: Capacity-building activities of a psychosocial program. International Journal of Mental Health, 48(4), 323–329. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00207411.2019.1602019

- Vostanis, P., Eruyar, S., Smit, E., & O’Reilly, M. (2019). Development of child psychosocial framework in Kenya, Turkey and Brazil. Journal of Children’s Services, 14(4), 303–316. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JCS-02-2019-0008

- Vostanis, P., O’Reilly, M., Duncan, C., Maltby, J., & Anderson, E. (2019). Interprofessional training for resilience-building for children who experience trauma: Stakeholders’ views from six low- and middle-income countries. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 33(2), 143–152. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2018.1538106

- Ward, V., Pinkney, L., & Fry, G. (2016). Developing a framework for gathering and using service user experiences to improve health and social care: The SUFFICE framework. BMC Research Notes, 9(1), 437. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-016-2230-0

- White, R., Imperiale, M., & Perera, E. (2016). The capabilities approach: Fostering contexts for enhancing mental health and wellbeing across the globe. Globalization and Health, 12(1), 1. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-016-0150-3

- World Health Organisation. (2010). Framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice. WHO.

- World Health Organisation. (2013). Transforming and scaling up health professionals’ education and training. WHO.

- World Health Organisation. (2014). Integrating the response to mental disorders and other chronic diseases in healthcare. WHO.

- World Health Organisation. (2016). Mental health: Strengthening response. WHO.